Paul Grottkau on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Paul Grottkau (1846–1898) was a

Paul Grottkau (1846–1898) was a

Dictionary of Wisconsin History, Wisconsin Historical Society, www.wisconsinhistory.org/ Part of this training process involved Grottkau's learning the crafts of stonemasonry and building, activities which brought him into contract with members of the

It was not long before Grottkau was made editor of the daily ''Arbeiter-Zeitung,'' working closely alongside managing editor

It was not long before Grottkau was made editor of the daily ''Arbeiter-Zeitung,'' working closely alongside managing editor

Grottkau became one of the leaders of the militant Milwaukee Central Labor Union, a group which, together with the

Grottkau became one of the leaders of the militant Milwaukee Central Labor Union, a group which, together with the  In the afternoon of Wednesday, May 5, 1886, strikers again assembled to march on the

In the afternoon of Wednesday, May 5, 1886, strikers again assembled to march on the

''Anarchismus Oder Communismus?''

Geführt von Paul Grottkau und

Paul Grottkau (1846–1898) was a

Paul Grottkau (1846–1898) was a German-American

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

political activist and newspaper publisher. Grottkau is best remembered as an editor alongside Haymarket affair

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square (C ...

victim August Spies

August Vincent Theodore Spies (, ; December 10, 1855November 11, 1887) was an American upholsterer, radical labor activist, and newspaper editor. Spies is remembered as one of the anarchists in Chicago who were found guilty of conspiracy to commi ...

of the '' Chicagoer Arbeiter-Zeitung,'' one of the leading American radical newspapers of the decade of the 1880s. Later moving to Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee is ...

, Grottkau became one of the leading luminaries of the socialist movement in Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

.

Biography

Early years

Paul Grottkau was born inCottbus

Cottbus (; Lower Sorbian: ''Chóśebuz'' ; Polish: Chociebuż) is a university city and the second-largest city in Brandenburg, Germany. Situated around southeast of Berlin, on the River Spree, Cottbus is also a major railway junction with exten ...

in 1846 and raised in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

(now part of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

), the son of a relatively prosperous noble

A noble is a member of the nobility.

Noble may also refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Noble Glacier, King George Island

* Noble Nunatak, Marie Byrd Land

* Noble Peak, Wiencke Island

* Noble Rocks, Graham Land

Australia

* Noble Island, Great B ...

family.Harmut Keil, "The German Immigrant Working Class of Chicago, 1875-90: Workers, Labor Leaders, and the Labor Movement," in Dirk Hoerder (ed.), ''American Labor and Immigration History, 1877-1920s: Recent European Research.'' Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983; pg. 165.

Grottkau was trained as an architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

."Paul Grottkau, 1846-1898,"Dictionary of Wisconsin History, Wisconsin Historical Society, www.wisconsinhistory.org/ Part of this training process involved Grottkau's learning the crafts of stonemasonry and building, activities which brought him into contract with members of the

working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

and first introduced him to socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

ideas.

Grottkau was initially highly influenced by the electorally-oriented ideas of Ferdinand Lassalle

Ferdinand Lassalle (; 11 April 1825 – 31 August 1864) was a Prussian-German jurist, philosopher, socialist and political activist best remembered as the initiator of the social democratic movement in Germany. "Lassalle was the first man in Ger ...

. By 1871 Grottkau was already a member of the General German Workingmen's Association and worked as an organizer for the burgeoning social democratic movement. He also served as editor of the official organ of the Bricklayers Union, ''Grundstein,'' and as editor of the radical ''Berliner Freie Presse.''Harmut Keil, "A Profile of Editors of the German-American Radical Press, 1850-1910," in Elliott Shore, Ken Fones-Wolf, and James P. Danky (eds.), ''The German-American Radical Press: The Shaping of a Left Political Culture, 1850-1940.'' Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992; pp. 20-21.

This political activism placed Grottkau in the sights of the German police. Faced with arrest by the authorities under the Anti-Socialist Laws

The Anti-Socialist Laws or Socialist Laws (german: Sozialistengesetze; officially , approximately "Law against the public danger of Social Democratic endeavours") were a series of acts of the parliament of the German Empire, the first of which was ...

, Grottkau emigrated to the United States of America in 1878. A talented writer and orator

An orator, or oratist, is a public speaker, especially one who is eloquent or skilled.

Etymology

Recorded in English c. 1374, with a meaning of "one who pleads or argues for a cause", from Anglo-French ''oratour'', Old French ''orateur'' (14th ...

, Grottkau found his way to the German émigré community in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, where he immediately landed a job on the staff of the Social Democratic

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote soci ...

'' Chicagoer Arbeiter-Zeitung'' (Chicago Workers' News).

Chicago years

It was not long before Grottkau was made editor of the daily ''Arbeiter-Zeitung,'' working closely alongside managing editor

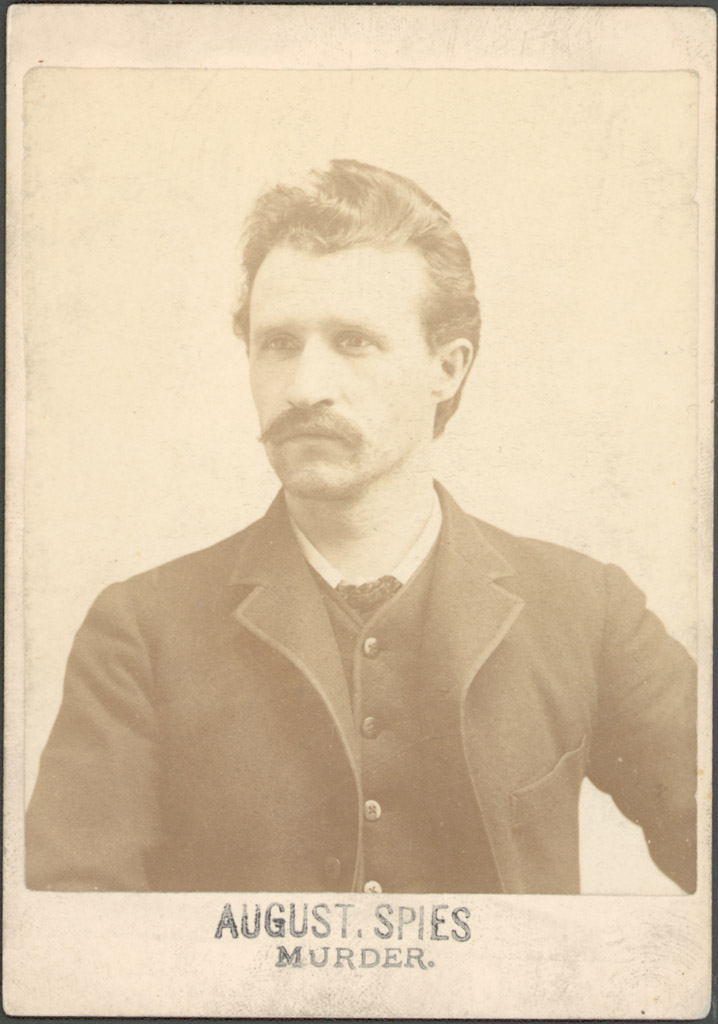

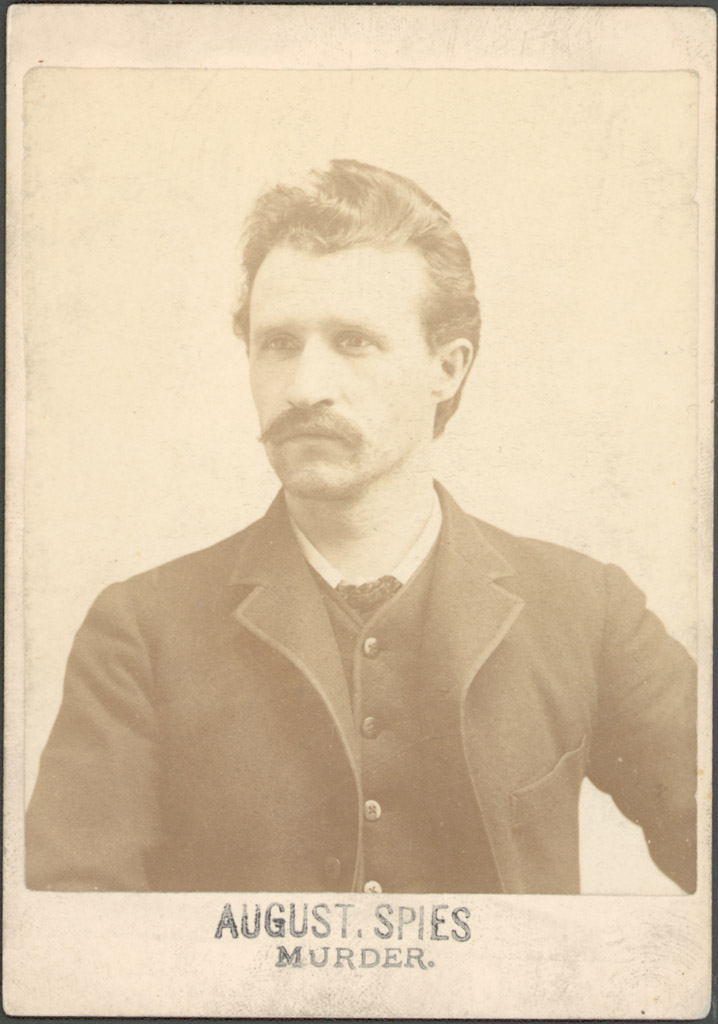

It was not long before Grottkau was made editor of the daily ''Arbeiter-Zeitung,'' working closely alongside managing editor August Spies

August Vincent Theodore Spies (, ; December 10, 1855November 11, 1887) was an American upholsterer, radical labor activist, and newspaper editor. Spies is remembered as one of the anarchists in Chicago who were found guilty of conspiracy to commi ...

, a man later killed in a retaliatory execution in the aftermath of the May 1886 Haymarket bombing. Together with Spies and the American-born Albert Parsons

Albert Richard Parsons (June 20, 1848 – November 11, 1887) was a pioneering American socialist and later anarchist newspaper editor, orator, and labor activist. As a teenager, he served in the military force of the Confederate States of Americ ...

, Grottkau emerged as one of the leaders of the radical movement in Chicago during the tumultuous end of the 1870s and first years of the 1880s.

During this interval the socialist movement of Chicago, centered around branches of the Socialist Labor Party of America

The Socialist Labor Party (SLP)"The name of this organization shall be Socialist Labor Party". Art. I, Sec. 1 of thadopted at the Eleventh National Convention (New York, July 1904; amended at the National Conventions 1908, 1912, 1916, 1920, 1924 ...

(SLP), began to turn towards the ideas of armed insurrection

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

and anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessa ...

. Membership in the SLP plummeted, hitting a low water mark of just 1500 members in 1883, while the number of semi-independent anarchist "groups" multiplied and their membership rolls proliferated. Grottkau, like many others, was briefly swept up in this tide, and the ''Arbeiter-Zeitung'' was made a leading voice of American anarchism.

In the view of historian Howard H. Quint the reason for Grottkau's willingness to cast his lot with the so-called Social Revolutionaries (i.e. the Anarchists) in the early 1880s was related not to his affinity for their paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

auxiliary, units of the ''Lehr und Wehr Verein

The ''Lehr und Wehr Verein'' ("Educational and Defense Society") was a socialist military organization founded in 1875, in Chicago, Illinois. The group had been formed to counter the armed private armies of companies in Chicago.

The ''Lehr und W ...

'' (Educational and Defensive Society), but rather due to a desire to change the personnel and tepid policy of the SLP, exemplified by the group's National Secretary, Philip Van Patten

Simon Philip Van Patten (1852–1918) was an American socialist political activist prominent during the latter half of the 1870s and the first half of the 1880s. Van Patten is best remembered for being named the first Corresponding Secretary of t ...

. While the meddling of Van Patten and the Detroit-based National Executive Committee of the SLP may have been Grottkau's primary objection, he nevertheless went all the way with the anarchist wing for a time, going so far as to himself briefly join the ''Lehr und Wehr Verein.''

Grottkau ultimately broke with Spies, Parsons, and the Social Revolutionaries following the 1883 Pittsburgh Convention of the Revolutionary Socialist Party, which formally rejected socialist collectivism

Collectivism may refer to:

* Bureaucratic collectivism, a theory of class society whichto describe the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin

* Collectivist anarchism, a socialist doctrine in which the workers own and manage the production

* Collectivis ...

in favor of communist anarchism.Gary M. Fink (ed.), "Paul Grottkau," in ''Biographical Dictionary of the American Left.'' Revised Edition. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1984; pp. 268-269. In the aftermath the Socialist Revolutionaries went over to full-fledged anarchism, while the more moderate and electorally oriented elements such as Grottkau returned to the ranks of the SLP.

This new fissure was made eminently clear on the evening of May 24, 1884, when Grottkau appeared before a Chicago audience to debate the "Communist" position against Johann Most

Johann Joseph "Hans" Most (February 5, 1846 – March 17, 1906) was a German-American Social Democratic and then anarchism, anarchist politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "propaganda of the dee ...

, a leading voice of the Anarchist movement.Hillquit, ''History of Socialism in the United States,'' pg. 241. Morris Hillquit

Morris Hillquit (August 1, 1869 – October 8, 1933) was a founder and leader of the Socialist Party of America and prominent labor lawyer in New York City's Lower East Side. Together with Eugene V. Debs and Congressman Victor L. Berger, Hil ...

, one of the earliest historians of American socialism, recalled the affair:

It was a well-matched contest, the opponents being equally well-versed in the subject of discussion and both being fluent speakers and ready debaters. The discussion was very thoroughgoing and dealt with almost every phase of the subject. It was reported stenographically, published in book form, and widely circulated.Another pioneer historian of American socialism,

Frederic Heath

Frederic Faries Heath (1864–1954) was an American socialist politician and journalist who was a founding member of the Social Democratic Party of America in 1897 and the Socialist Party of America in 1901. He was an elected official in Wisconsin ...

, recalls the Most–Grottkau debate as pivotal in Grottkau's own personal story. According to his account:

Grottkau was now thoroughly enlisted against the Anarchists, realizing that they were inimical to the true interests of the proletarian movement. He fought valiantly for his view of the matter and wrote and spoke ardently, but the ground he had himself prepared was against him. He had a notable debate with Most in which he had decidedly the best of the argument and achieved an intellectual and argumentative victory; but not so thought the crowd, which was still filled with his previous teachings. A few weeks later he was forced to retire from the ''Arbeiter-Zeitung'' and to turn over the editorial pen to August Spies, the former business manager, a man more to Most's liking.

Milwaukee years

Forced out of his editorial position in Chicago, Grottkau left the city to establish a paper of his own inMilwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee is ...

, Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

— the ''Milwaukee'r Arbeiter-Zeitung'' (Milwaukee Workers' News), issued three times a week.Marvin Wachman, ''History of the Social-Democratic Party of Milwaukee, 1897-1910.'' Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1945; pg. 10. The paper commenced publication in 1886.Shore, Fones-Wolf, and Danky (eds.), ''The German-American Radical Press,'' pg. 215.

Grottkau became one of the leaders of the militant Milwaukee Central Labor Union, a group which, together with the

Grottkau became one of the leaders of the militant Milwaukee Central Labor Union, a group which, together with the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

, coordinated a march in that city on May Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the spring equinox and summer solstice. Festivities may also be held the night before, known as May Eve. T ...

1886 as a means of agitating for establishment of the 8-hour day. About 16,000 people participated in the May Day festivities, with several thousand marching in support of the Central Labor Union and the Knights of Labor.Henry E. Legler, ''Leading Events of Wisconsin History: The Story of the State.'' Milwaukee: Sentinel Co., 1898; pg. 303. This gathering and march proceeded without incident, but the groundwork seems to have been laid for further activity.

On Monday, May 3, 1886, a general strike was called on Milwaukee's breweries, with as many as 1,000 men marching on Falk's Brewery in an effort to close the facility. Masses of brewery workers joined the protest and by that evening some 14,000 brewery workers were out on strike. That same afternoon several hundred Polish workers went to the railroad shops located in the Menomonee Valley

The Menomonee Valley or Menomonee River Valley is a U-shaped land formation along the southern bend of the Menomonee River in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Because of its easy access to Lake Michigan and other waterways, the neighborhood has historically ...

to appeal to the 1400 railway shopmen working there to join the general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

.Legler, ''Leading Events of Wisconsin History'', pg. 304. Most refused to quit work and law enforcement authorities were called upon to break up the group of strike agitators.

The Polish strike leaders proceeded to the Reliance Iron Works, where fire hoses were turned on them, with the effect that "the catapult power of the stream shot some of the men clear across the street." About 20 policemen appeared on the scene and began clubbing the wet strikers with their hickory nightsticks.Legler, ''Leading Events of Wisconsin History'', pg. 305. Governor Jeremiah Rusk

Jeremiah McLain Rusk (June 17, 1830November 21, 1893) was an Americans, American Republican Party (United States), Republican politician. He was the second United States secretary of agriculture (1889–1893) and the 15th governor of Wisconsi ...

was notified by telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

and several units of the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

were dispatched to Milwaukee from their station in Madison Madison may refer to:

People

* Madison (name), a given name and a surname

* James Madison (1751–1836), fourth president of the United States

Place names

* Madison, Wisconsin, the state capital of Wisconsin and the largest city known by this ...

, arriving on the scene the next morning.

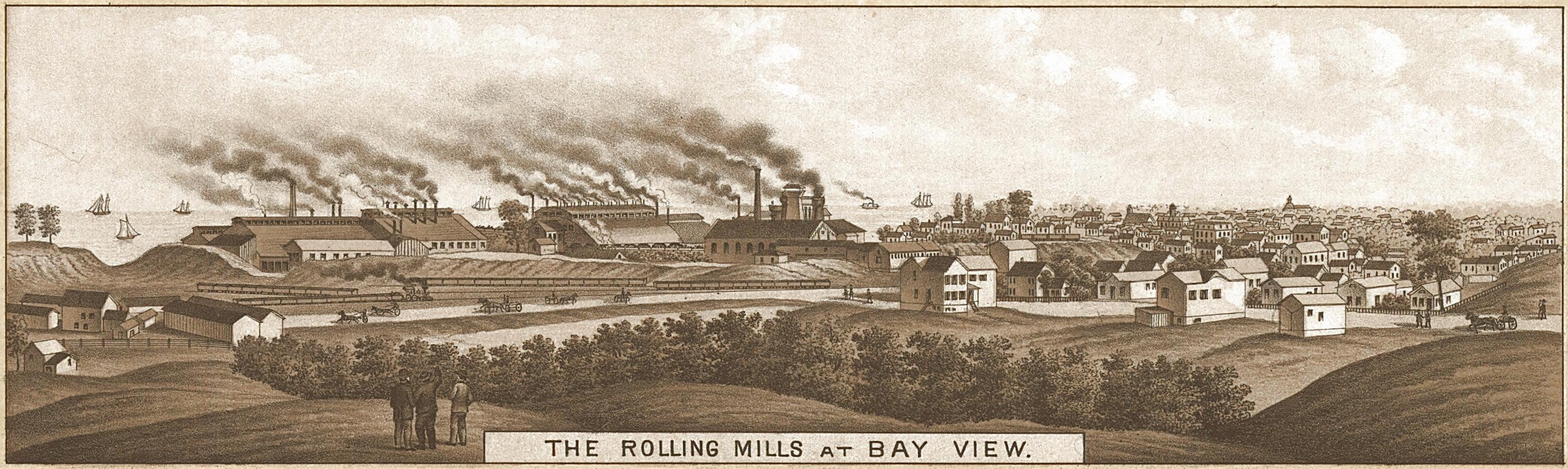

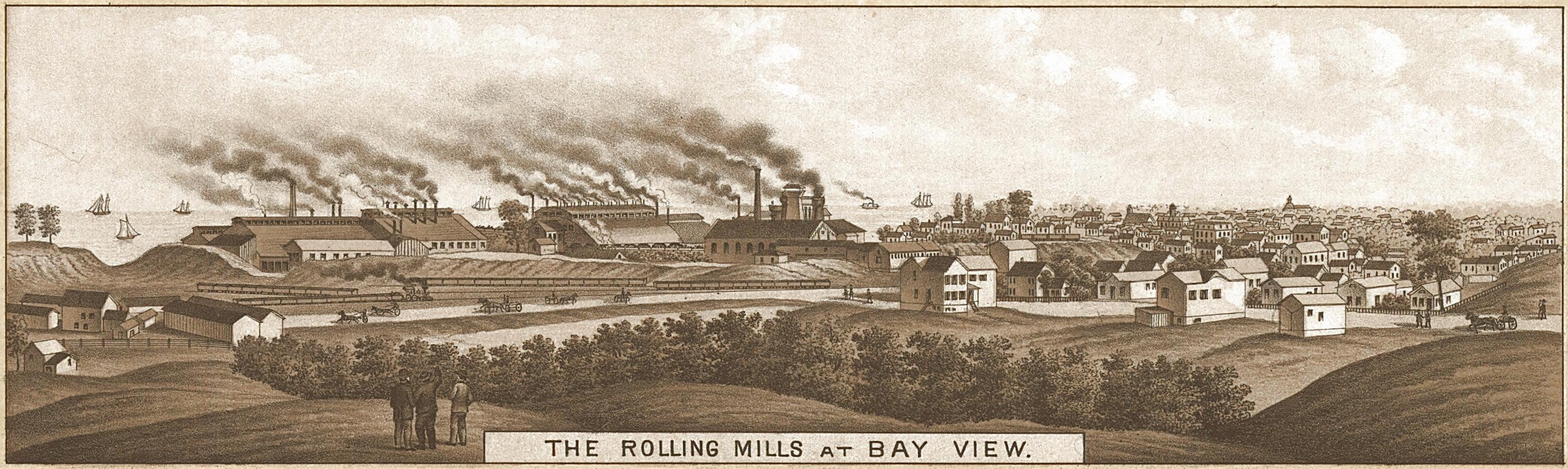

At about 7 am, some 600 or 700 men, armed with clubs, assembled and began to march on the steel rolling mill

In metalworking, rolling is a metal forming process in which metal stock is passed through one or more pairs of rolls to reduce the thickness, to make the thickness uniform, and/or to impart a desired mechanical property. The concept is simil ...

s located in the Bay View area of the city.

The protest degenerated into violence, with the so-called "reign of terror" recalled by one contemporary adherent of law and order:

Idle workmen paraded the streets; men willing to work were urged to join the demonstration and in many cases compelled to do so; crowds armed with paving blocks, billets, and other improvised weapons of the street overturned hucksters' stands, invaded manufacturing establishments, and even attacked them. As the riotous proceedings grew to large proportions and the city seemed about to be stretched at the mercy of a mob, a deadly fire from the rifles of state militiamen was poured into a crowd ofThe same historian noted that despite the firing of shots, "not one person was wounded in the volley," noting:Polish Polish may refer to: * Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe * Polish language * Poles Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...workmen and ended the lawlessness which had threatened to grow beyond control.

Many of the mob, as they saw the rifles aimed, threw themselves flat upon the ground, others sought shelter behind woodpiles and telegraph posts and fences. Notwithstanding, it seemed providential that the ground was not strewn with dead and dying. Many buildings in range of the rifles were perforated with bullets ...

In the afternoon of Wednesday, May 5, 1886, strikers again assembled to march on the

In the afternoon of Wednesday, May 5, 1886, strikers again assembled to march on the company town

A company town is a place where practically all stores and housing are owned by the one company that is also the main employer. Company towns are often planned with a suite of amenities such as stores, houses of worship, schools, markets and re ...

of Bay View.Legler, ''Leading Events of Wisconsin History'', pg. 307. This time, new orders had been issued to the members of the National Guard by Governor Rusk — that, in the event of the repeat of mob tactics, the guardsmen should this time shoot to kill. Guardsmen blocked the road. When the approaching strikers were 1000 yards away, commanding officer Major George P. Traeumer gave the command to fire and a hail of bullets was unleashed on the crowd.Legler, ''Leading Events of Wisconsin History'', pg. 308. The number wounded will never be known, having been carried away by the fleeing crowd, but eight people died in what is today remembered as the Bay View Massacre. Included among these was an old man who had been feeding chickens in his yard and a young schoolboy.

In the aftermath Paul Grottkau was arrested, ostensibly as the perpetrator of the strike, and sentenced to one year in prison. Grottkau served only six weeks of this sentence before being released, during which time he ran a campaign in an effort to become the next Mayor of Milwaukee

This is a list of mayors of Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

List

External linksJS Online

{{Mayors of the City of Milwaukee

Milwaukee

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Mayors

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal governmen ...

.

Grottkau would continue to edit the ''Milwaukee'r Arbeiter-Zeitung'' until 1888, briefly moving back to Chicago following the publication's sale to again work on the paper's Chicago namesake.

Later years

Grottkau moved toSan Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

in 1889. There he became editor of the ''California Arbeiterzeitung,'' a short-lived publication.

In 1890 Grottkau was named as a traveling organizer by the Executive Council of the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutu ...

, assigned the task of touring the country on behalf of the Federation's campaign for the 8-hour day.

In January 1893 Grottkau's old newspaper, the ''Arbeiter-Zeitung,'' was sold to a young Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

schoolteacher of Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

n birth, Victor L. Berger

Victor Luitpold Berger (February 28, 1860August 7, 1929) was an Austrian–American socialist politician and journalist who was a founding member of the Social Democratic Party of America and its successor, the Socialist Party of America. Born in ...

, who relaunched the publication as the '' Wisconsin Vorwärts'' ('Wisconsin Forward').Sally M. Miller, ''Victor Berger and the Promise of Constructive Socialism, 1910-1920.'' Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1973; pg. 32. This would be the first of several publication's in Berger's portfolio, which would ultimately prove to be the stepping-stone to the socialist publisher's election to United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

in the fall of 1910.

During his final year of life Grottkau joined the Social Democracy of America

The Social Democracy of America (SDA), later known as the Cooperative Brotherhood, was a short lived political party in the United States that sought to combine the planting of an intentional community with political action in order to create a s ...

, a political forerunner of the Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of Ameri ...

."Labor Leader's Death: Paul Grottkau Expires at St. Joseph's Hospital," ''Milwaukee News,'' June 4, 1898, unspecified page. Copy preserved in The Papers of Eugene V. Debs 1834-1945 microfilm edition, reel 9.

Death and legacy

In the spring of 1898, Grottkau made a speaking tour on behalf of the Social Democracy, visiting the cities of Buffalo,Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

, and Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at th ...

. During this trip Grottkau contracted pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

, which led to his hospitalization at St. Joseph's Hospital in Milwaukee on May 30. Grottkau's condition continued to deteriorate and he succumbed to the effects of the illness in the evening of June 3, 1898.

A funeral was held in Milwaukee on June 5, 1898, which was addressed by Victor L. Berger in German as well as by other prominent Milwaukee labor and political leaders. Grottkau's body was interred at Forest Home Cemetery in Milwaukee."Wisconsin, Death Records, 1867-1907," database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XLCZ-51C : accessed 20 August 2015), Paul Grottkau, 1898; citing Death, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Wisconsin State Historical Society, Madison; FHL microfilm 1,310,327.

Footnotes

Works

* ''Unterhaltendes in 12 Briefen zusammengestellt an die Mitglieder des Allgemeinen deutschen Maurer- und Steinhauer-Vereins und Solche, die es werden wollen. Verfaßt und hrsg. im Auftrage des Allgemeinen deutschen Maurer-Vereins''. Berlin 1873, 108 pp. * ''Die rothe Laterne. Humoristisches Organ zur Beleuchtung politischer und sozialer Schattenseiten. Humoristisch-satirische Wahlzeitung aus den Wahlkämpfen 1874''. Editor: Paul Grottkau. Schoenfeld & Baumgarten, Berlin 1874 * ''Chicagoer Arbeiter-Zeitung. Unabhängiges Organ für die Interessen des Volkes. Organ der internationalen Vereinigung des arbeitenden Volkes.'' Editor: Paul Grottkau. July, 14th 1880 to September 1884 * ''Vorbote''. Hrsg. Internationale Vereinigung des arbeitenden Volkes. Redaktion: Paul Grottkau vom 1. Juli 1882 bis 4. Mai 1886. Deutschsprechende Sektion des S.A.P. Chicago * ''Karl Marx todt!'' In: ''Chicagoer-Arbeiter-Zeitung''. Chicago, 16. März 1883 * ''Karl Marx todt!'' In: ''Vorbote'', Chicago. Nr. 12, 24. März 1883 (printed in: ''Ihre Namen Leben durch die Jahrhunderte fort. Kondolenzen und Nekrologe zum Tode von Karl Marx und Friedrich Engels''. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1983, p. 209-211.) * ''Zum Kongress der Sozialisten Nord-Amerikas''. In: ''Freiheit. Organ der Revolutionären Sozialisten''. Justus H. Schwab, New York. 1883. V. Jg., Nr. 32 August, 11th. August 1883''Anarchismus Oder Communismus?''

Geführt von Paul Grottkau und

Johann Most

Johann Joseph "Hans" Most (February 5, 1846 – March 17, 1906) was a German-American Social Democratic and then anarchism, anarchist politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "propaganda of the dee ...

am 24 Mai 1884 in Chicago. Das Central-Comite der Chicagoer Gruppen der IAA, Office der "Chicagoer Arbeiter-Zeitung" und der "Verbote". Chicago 1884.

* ''Illinois Volkszeitung''. Edited by Paul Grottkau and Julius Vahlteich. 1886

* ''Milwaukee Arbeiterzeitung''. Editor Paul Grottkau. 1888

{{DEFAULTSORT:Grottkau, Paul

1846 births

1898 deaths

People from Cottbus

People from the Province of Brandenburg

General German Workers' Association politicians

German emigrants to the United States

Wisconsin socialists

Businesspeople from San Francisco

Businesspeople from Chicago

Businesspeople from Milwaukee

American newspaper editors

Editors of California newspapers

Editors of Illinois newspapers

Editors of Wisconsin newspapers

History of Wisconsin

19th-century American journalists

American male journalists

19th-century American male writers

19th-century American businesspeople

Deaths from pneumonia in Wisconsin