Patrick Kavanagh on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

To be a poet and not know the trade,

To be a lover and repel all women;

Twin ironies by which great saints are made,

The agonising pincer-jaws of heaven.

When the ''

O commemorate me where there is water

canal water preferably, so stilly

greeny at the heart of summer. Brother

commemorate me thus beautifully.

Every 17 March, after the St Patrick's day parade, a group of Kavanagh's friends gather at the Kavanagh seat on the banks of the Grand Canal at Mespil road in his honour. The seat was erected by his friends, led by John Ryan and Denis Dwyer, in 1968. A bronze sculpture of the writer stands outside the Palace Bar on Dublin's

Profile and poems at the Poetry Archive

Poetry Foundation profile and poems

from the Patrick Kavanagh Trust

The Patrick Kavanagh Centre

Patrick Kavanagh Grand Canal South Bank Seat

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kavanagh, Patrick 1904 births 1967 deaths Claddagh Records artists Gaelic football goalkeepers Inniskeen Grattans Gaelic footballers Irish male novelists People from County Monaghan 20th-century Irish poets 20th-century male writers

Patrick Kavanagh (21 October 1904 – 30 November 1967) was an Irish poet and novelist. His best-known works include the novel '' Tarry Flynn'', and the poems "

from the Patrick Kavanagh Trust He became apprenticed to his father as a shoemaker and worked on his farm. He was also goalkeeper for the

Kavanagh's first published work appeared in 1928 in the ''

Kavanagh's first published work appeared in 1928 in the ''

Kavanagh married his long-term companion Katherine Barry Moloney (niece of

Kavanagh married his long-term companion Katherine Barry Moloney (niece of

The actor

The actor

producer responsible, Malcolm Gerrie. He said: "it was about a one minute fifty speech but they've cut a minute out of it". The poem that was cut was a four-line poem:

On Raglan Road

"On Raglan Road" is a well-known Irish song from a poem written by Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh named after Raglan Road in Ballsbridge, Dublin. In the poem, the speaker recalls, while walking on a "quiet street," a love affair that he had with ...

" and "The Great Hunger". He is known for his accounts of Irish life through reference to the everyday and commonplace.

Life and work

Early life

Patrick Kavanagh was born in ruralInniskeen

Inniskeen, officially Inishkeen (), is a small village, townland and parish in County Monaghan, Ireland, close to the County Louth and County Armagh borders. The village is located about from Dundalk, from Carrickmacross, and from Crossmaglen ...

, County Monaghan

County Monaghan ( ; ga, Contae Mhuineacháin) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Ulster and is part of Border strategic planning area of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town of Monaghan. Monaghan County Cou ...

, in 1904, the fourth of ten children of James Kavanagh and Bridget Quinn. His grandfather was a schoolteacher called "Kevany", which a local priest changed to " Kavanagh" at his baptism. The grandfather had to leave the area following a scandal and never taught in a national school again, but married and raised a family in Tullamore

Tullamore (; ) is the county town of County Offaly in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is on the Grand Canal (Ireland), Grand Canal, in the middle of the county, and is the fourth most populous town in the Midland Region, Ireland, midlands reg ...

. Patrick Kavanagh's father, James, was a cobbler and farmer. Kavanagh's brother Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a sur ...

became a university professor and writer, two of their sisters were teachers, three became nurses, and one became a nun.

Patrick Kavanagh was a pupil at Kednaminsha National School from 1909 to 1916, leaving in sixth class at the age of 13.Profilefrom the Patrick Kavanagh Trust He became apprenticed to his father as a shoemaker and worked on his farm. He was also goalkeeper for the

Inniskeen

Inniskeen, officially Inishkeen (), is a small village, townland and parish in County Monaghan, Ireland, close to the County Louth and County Armagh borders. The village is located about from Dundalk, from Carrickmacross, and from Crossmaglen ...

Gaelic football

Gaelic football ( ga, Peil Ghaelach; short name '), commonly known as simply Gaelic, GAA or Football is an Irish team sport. It is played between two teams of 15 players on a rectangular grass pitch. The objective of the sport is to score by kic ...

team. He later reflected: "Although the literal idea of the peasant is of a farm labouring person, in fact a peasant is all that mass of mankind which lives below a certain level of consciousness. They live in the dark cave of the unconscious and they scream when they see the light." He also commented that, although he had grown up in a poor district, "the real poverty was lack of enlightenment ndI am afraid this fog of unknowing affected me dreadfully."

Writing career

Kavanagh's first published work appeared in 1928 in the ''

Kavanagh's first published work appeared in 1928 in the ''Dundalk Democrat

The ''Dundalk Democrat'' is a regional newspaper printed in Dundalk, Ireland. Established in 1849, it primarily serves County Louth as well as County Monaghan and parts of County Armagh, County Down, County Cavan and County Meath. It comes out ev ...

'' and the ''Irish Independent

The ''Irish Independent'' is an Irish daily newspaper and online publication which is owned by Independent News & Media (INM), a subsidiary of Mediahuis.

The newspaper version often includes glossy magazines.

Traditionally a broadsheet new ...

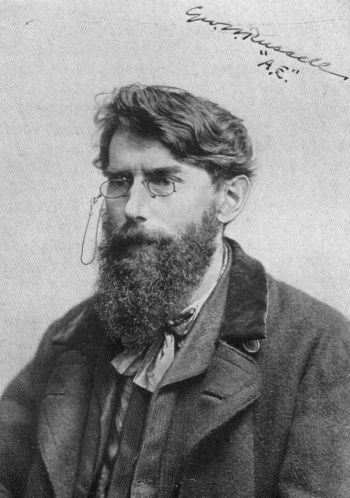

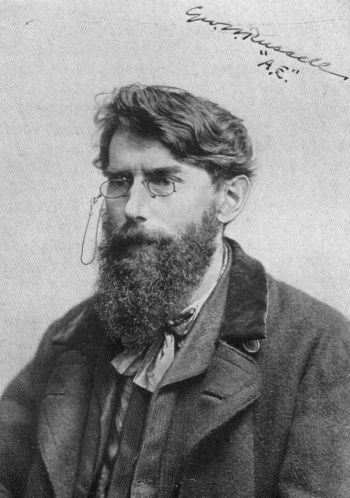

''. Kavanagh had encountered a copy of the ''Irish Statesman'', edited by George William Russell

George William Russell (10 April 1867 – 17 July 1935), who wrote with the pseudonym Æ (often written AE or A.E.), was an Irish writer, editor, critic, poet, painter and Irish nationalist. He was also a writer on mysticism, and a centra ...

, who published under the pen name AE and was a leader of the Irish Literary Revival

The Irish Literary Revival (also called the Irish Literary Renaissance, nicknamed the Celtic Twilight) was a flowering of Irish literary talent in the late 19th and early 20th century. It includes works of poetry, music, art, and literature.

O ...

. Russell at first rejected Kavanagh's work but encouraged him to keep submitting, and he went on to publish verse by Kavanagh in 1929 and 1930. This inspired the farmer to leave home and attempt to further his aspirations. In 1931, he walked 80 miles (abt. 129 kilometres) to meet Russell in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, where Kavanagh's brother was a teacher. Russell gave Kavanagh books, among them works by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

, Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

, Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

, Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champ ...

and Robert Browning

Robert Browning (7 May 1812 – 12 December 1889) was an English poet and playwright whose dramatic monologues put him high among the Victorian poets. He was noted for irony, characterization, dark humour, social commentary, historical settings ...

, and became Kavanagh's literary adviser. Kavanagh joined Dundalk Library and the first book he borrowed was ''The Waste Land

''The Waste Land'' is a poem by T. S. Eliot, widely regarded as one of the most important poems of the 20th century and a central work of modernist poetry. Published in 1922, the 434-line poem first appeared in the United Kingdom in the Octob ...

'' by T. S. Eliot.

Kavanagh's first collection, ''Ploughman and Other Poems'', was published in 1936. It is notable for its realistic portrayal of Irish country life, free of the romantic sentiment often seen at the time in rural poems, a trait he abhorred. Published by Macmillan in its series on new poets, the book expressed a commitment to colloquial speech and the unvarnished lives of real people, which made him unpopular with the literary establishment. Two years after his first collection was published he had yet to make a significant impression. The ''Times Literary Supplement

''The Times Literary Supplement'' (''TLS'') is a weekly literary review published in London by News UK, a subsidiary of News Corp.

History

The ''TLS'' first appeared in 1902 as a supplement to '' The Times'' but became a separate publication ...

'' described him as "a young Irish poet of promise rather than of achievement," and ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''The ...

'' commented that, "like other poets admired by A.E., he writes much better prose than poetry. Mr Kavanagh's lyrics are for the most part slight and conventional, easily enjoyed but almost as easily forgotten."

In 1938 Kavanagh went to London. He remained there for about five months. ''The Green Fool'', a loosely autobiographical novel, was published in 1938 and Kavanagh was accused of libel. Oliver St. John Gogarty

Oliver Joseph St. John Gogarty (17 August 1878 – 22 September 1957) was an Irish poet, author, otolaryngologist, athlete, politician, and well-known conversationalist. He served as the inspiration for Buck Mulligan in James Joyce's novel ...

sued Kavanagh for his description of his first visit to Gogarty's home: "I mistook Gogarty's white-robed maid for his wife or his mistress; I expected every poet to have a spare wife." Gogarty, who had taken offence at the close coupling of the words "wife" and "mistress", was awarded £100 in damages. The book, which recounted Kavanagh's rural childhood and his attempts to become a writer, received international recognition and good reviews. However, it was also claimed to be somewhat 'anti-Catholic' in tone, to which Kavanagh reacted by demanding that the work be prominently displayed in Dublin book shop windows.

The Emergency

The outbreak ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

(known as The Emergency in the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. A ...

) had a damaging effect on the emerging careers of some Irish writers, including Flann O'Brien as well as Kavanagh as they lost access to their publishers in London and reprints of their books could not be arranged. The Republic, which was neutral during the war, shared a border with Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

(which, as part of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

was involved on the Allied side). There were smuggling opportunities on the border, especially in Monaghan

Monaghan ( ; ) is the county town of County Monaghan, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It also provides the name of its Civil parishes in Ireland, civil parish and Monaghan (barony), barony.

The population of the town as of the 2016 census was 7 ...

, which would have been more lucrative than writing at this time.

In 1939 Kavanagh settled in Dublin. In his biography John Nemo describes Kavanagh's encounter with the city's literary world: "he realized that the stimulating environment he had imagined was little different from the petty and ignorant world he had left. He soon saw through the literary masks many Dublin writers wore to affect an air of artistic sophistication. To him such men were dandies, journalists, and civil servants playing at art. His disgust was deepened by the fact that he was treated as the literate peasant he had been rather than as the highly talented poet he believed he was in the process of becoming".

During this time he met John Betjeman

Sir John Betjeman (; 28 August 190619 May 1984) was an English poet, writer, and broadcaster. He was Poet Laureate from 1972 until his death. He was a founding member of The Victorian Society and a passionate defender of Victorian architecture, ...

who was based in Dublin during the Emergency nominally as a press attaché but also working for British intelligence

The Government of the United Kingdom maintains intelligence agencies within three government departments, the Foreign Office, the Home Office and the Ministry of Defence. These agencies are responsible for collecting and analysing foreign and d ...

. Betjeman, impressed by Kavanagh's wide range of social contacts in, his ability to get invited to events, and his political ambiguity, tried to recruit him as a British spy.

In 1942 he published his long poem ''The Great Hunger'', which describes the privations and hardship of the rural life he knew well. Although it was rumoured at the time that all copies of ''Horizon

The horizon is the apparent line that separates the surface of a celestial body from its sky when viewed from the perspective of an observer on or near the surface of the relevant body. This line divides all viewing directions based on whether i ...

'', the literary magazine in which it was published, were seized by the Garda Síochána

(; meaning "the Guardian(s) of the Peace"), more commonly referred to as the Gardaí (; "Guardians") or "the Guards", is the national police service of Ireland. The service is headed by the Garda Commissioner who is appointed by the Irish Gover ...

, Kavanagh denied that this had occurred, saying later that he was visited by two Gardaí at his home (probably in connection with an investigation of ''Horizon'' under the Special Powers Act). Written from the viewpoint of a single peasant against the historical background of famine and emotional despair, the poem is often held by critics to be Kavanagh's finest work. It set out to counter the saccharine romanticising of the Irish literary establishment in its view of peasant life. Richard Murphy in ''The New York Times Book Review

''The New York Times Book Review'' (''NYTBR'') is a weekly paper-magazine supplement to the Sunday edition of ''The New York Times'' in which current non-fiction and fiction books are reviewed. It is one of the most influential and widely rea ...

'' described it as "a great work" and Robin Skelton

Robin Skelton (12 October 1925 – 22 August 1997) was a British-born academic, writer, poet, and anthologist.

Biography

Born in Easington, Yorkshire, Skelton was educated at the University of Leeds and Cambridge University. From 1944 to 1947, ...

in ''Poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings i ...

'' praised it as "a vision of mythic intensity".

Post-war

Kavanagh worked as a part-time journalist, writing a gossip column in the ''Irish Press

''The Irish Press'' (Irish: ''Scéala Éireann'') was an Irish national daily newspaper published by Irish Press plc between 5 September 1931 and 25 May 1995.

Foundation

The paper's first issue was published on the eve of the 1931 All-Ireland ...

'' under the pseudonym Piers Plowman from 1942 to 1944 and acted as film critic for the same publication from 1945 to 1949. In 1946 the Archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid

John Charles McQuaid, C.S.Sp. (28 July 1895 – 7 April 1973), was the Catholic Primate of Ireland and Archbishop of Dublin between December 1940 and January 1972. He was known for the unusual amount of influence he had over successive govern ...

, found Kavanagh a job on the Catholic magazine '' The Standard''. McQuaid continued to support him throughout his life. ''Tarry Flynn'', a semi-autobiographical novel, was published in 1948 and was banned for a time. It is a fictional account of rural life. It was later made into a play, performed at the Abbey Theatre

The Abbey Theatre ( ga, Amharclann na Mainistreach), also known as the National Theatre of Ireland ( ga, Amharclann Náisiúnta na hÉireann), in Dublin, Ireland, is one of the country's leading cultural institutions. First opening to the p ...

in 1966.

In late 1946 Kavanagh moved to Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

, where he worked as a journalist and as a barman in a number of public houses in the Falls Road area. During this period he lodged in the Beechmount area in a house where he was related to the tenant through the tenant's brother-in-law in Ballymackney, County Monaghan

County Monaghan ( ; ga, Contae Mhuineacháin) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Ulster and is part of Border strategic planning area of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town of Monaghan. Monaghan County Cou ...

. Before returning to Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

in November 1949 he presented numerous manuscripts to the family, all of which are now believed to be in Spain.

Kavanagh's personality became progressively quixotic as his drinking increased over the years and his health deteriorated. Eventually becoming a dishevelled figure, he moved among the bars of Dublin, drinking whiskey and displaying his predilection for turning on benefactors and friends.

Later career

In 1949 Kavanagh began to write a monthly "Diary" for ''Envoy

Envoy or Envoys may refer to:

Diplomacy

* Diplomacy, in general

* Envoy (title)

* Special envoy, a type of diplomatic rank

Brands

*Airspeed Envoy, a 1930s British light transport aircraft

*Envoy (automobile), an automobile brand used to sell Br ...

'', a literary publication founded by John Ryan, who became a lifelong friend and benefactor. ''Envoy''s offices were at 39 Grafton Street, but most of the journal's business was conducted in a nearby pub, McDaid's, which Kavanagh subsequently adopted as his local. Through ''Envoy'' he came into contact with a circle of young artists and intellectuals including Anthony Cronin

Anthony Gerard Richard Cronin (28 December 1923 – 27 December 2016) was an Irish poet, arts activist, biographer, commentator, critic, editor and barrister.

Early life and family

Cronin was born in Enniscorthy, County Wexford on 28 December ...

, Patrick Swift Patrick may refer to:

* Patrick (given name), list of people and fictional characters with this name

* Patrick (surname), list of people with this name

People

* Saint Patrick (c. 385–c. 461), Christian saint

*Gilla Pátraic (died 1084), Patrick ...

, John Jordan and the sculptor Desmond MacNamara

Desmond J. MacNamara (10 May 1918 – 8 January 2008) was an Irish sculptor, painter, stage and art designer and novelist.

MacNamara was born in Mount Street, Dublin. After graduating from University College, Dublin

University College Dubli ...

, whose bust of Kavanagh is in the Irish National Writers Museum. Kavanagh often referred to these times as the period of his "poetic rebirth".

In 1952 Kavanagh published his own journal, ''Kavanagh’s Weekly: A Journal of Literature and Politics'', in conjunction with, and financed by, his brother Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a sur ...

. It ran to some 13 issues, from 12 April to 5 July 1952.

''The Leader'' lawsuit and lung cancer

In 1954 two major events changed Kavanagh's life. First, he issued libel proceedings against a magazine called ''The Leader'' for publishing an anonymously-written profile of him as an alcoholic sponger. Kavanagh had made numerous enemies in his film and literary criticism and had written diatribes against theCivil Service

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

, the Arts Council, the Irish Language movement so there were many possible authors of the piece. Based on his previous experience of libel, he believed he would get an out-of-court settlement. However, the magazine hired former (and future) Taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government, or prime minister, of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The office is appointed by the president of Ireland upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legisl ...

and Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

(1926–1932) John A. Costello as their barrister, who won the case when it came to trial.

Second, shortly after Kavanagh lost this case, he was diagnosed with lung cancer and was admitted to hospital, where he had a lung removed. It was while recovering from this operation

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Ma ...

by relaxing on the banks of the Grand Canal in Dublin that Kavanagh rediscovered his poetic vision. He began to appreciate nature and his surroundings, and took his inspiration from them for many of his later poems.

Costello and Kavanagh eventually became good friends, with Kavanagh remarking that he voted for him after the trial.

Turning point: Kavanagh begins to receive acclaim

In 1955 Macmillan rejected a typescript of poems by Kavanagh, which left the poet very depressed. Patrick Swift, on a visit to Dublin in 1956, was invited by Kavanagh to look at the typescript. Swift then arranged for the poems to be published in the English literary journal ''Nimbus

Nimbus, from the Latin for "dark cloud", is an outdated term for the type of cloud now classified as the nimbostratus cloud. Nimbus also may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Halo (religious iconography), also known as ''Nimbus'', a ring of ligh ...

''(19 poems were published). This proved a turning point and Kavanagh began receiving the acclaim that he had always felt he deserved. His next collection, ''Come Dance with Kitty Stobling'', was directly linked to the mini-collection in ''Nimbus''.

Between 1959 and 1962 Kavanagh spent more time in London, where he contributed to Swift's ''X'' magazine. During this period Kavanagh occasionally stayed with the Swifts in Westbourne Terrace. He gave lectures at University College Dublin

University College Dublin (commonly referred to as UCD) ( ga, Coláiste na hOllscoile, Baile Átha Cliath) is a public research university in Dublin, Ireland, and a collegiate university, member institution of the National University of Ireland ...

and in the United States, represented Ireland at literary symposiums, and became a judge of the Guinness Poetry Awards.

In London he often stayed with his publisher, Martin Green, and Green's wife Fiona, in their house in Tottenham Street, Fitzrovia

Fitzrovia () is a district of central London, England, near the West End. The eastern part of area is in the London Borough of Camden, and the western in the City of Westminster. It has its roots in the Manor of Tottenham Court, and was urban ...

. It was at this time that Martin Green produced Kavanagh's ''Collected Poems'' (1964) with prompting from Patrick Swift Patrick may refer to:

* Patrick (given name), list of people and fictional characters with this name

* Patrick (surname), list of people with this name

People

* Saint Patrick (c. 385–c. 461), Christian saint

*Gilla Pátraic (died 1084), Patrick ...

and Anthony Cronin

Anthony Gerard Richard Cronin (28 December 1923 – 27 December 2016) was an Irish poet, arts activist, biographer, commentator, critic, editor and barrister.

Early life and family

Cronin was born in Enniscorthy, County Wexford on 28 December ...

". In the introduction Kavanagh wrote: "A man innocently dabbles in words and rhymes, and finds that it is his life."

Marriage and death

Kavanagh married his long-term companion Katherine Barry Moloney (niece of

Kavanagh married his long-term companion Katherine Barry Moloney (niece of Kevin Barry

Kevin Gerard Barry (20 January 1902 – 1 November 1920) was an Irish Republican Army (IRA) soldier who was executed by the British Government during the Irish War of Independence. He was sentenced to death for his part in an attack upon a Brit ...

) in April 1967 and they set up home together on the Waterloo Road in Dublin. Kavanagh fell ill at the first performance of ''Tarry Flynn'' by the Abbey Theatre

The Abbey Theatre ( ga, Amharclann na Mainistreach), also known as the National Theatre of Ireland ( ga, Amharclann Náisiúnta na hÉireann), in Dublin, Ireland, is one of the country's leading cultural institutions. First opening to the p ...

company in Dundalk

Dundalk ( ; ga, Dún Dealgan ), meaning "the fort of Dealgan", is the county town (the administrative centre) of County Louth, Ireland. The town is on the Castletown River, which flows into Dundalk Bay on the east coast of Ireland. It is h ...

Town Hall and died a few days later, on 30 November 1967, in Dublin, in Merrion Nursing Home. His grave is in Inniskeen

Inniskeen, officially Inishkeen (), is a small village, townland and parish in County Monaghan, Ireland, close to the County Louth and County Armagh borders. The village is located about from Dundalk, from Carrickmacross, and from Crossmaglen ...

adjoining the Patrick Kavanagh Centre. His wife Katherine died in 1989; she is also buried there.

Legacy

Nobel Laureate Séamus Heaney is acknowledged to have been influenced by Kavanagh. Heaney was introduced to Kavanagh's work by the writerMichael McLaverty

Michael McLaverty (5 July 1904 – 22 March 1992) was an Irish writer of novels and short stories.Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

. Heaney and Kavanagh shared a belief in the capacity of the local, or parochial, to reveal the universal. Heaney once said that Kavanagh's poetry "had a transformative effect on the general culture and liberated the gifts of the poetic generations who came after him." Heaney noted: "Kavanagh is a truly representative modern figure in that his subversiveness was turned upon himself: dissatisfaction, both spiritual and artistic, is what inspired his growth.... His instruction and example helped us to see an essential difference between what he called the parochial and provincial mentalities". As Kavanagh put it: "All great civilizations are based on the parish". He concludes that Kavanagh's poetry vindicates his "indomitable faith in himself and in the art that made him so much more than himself".

The actor

The actor Russell Crowe

Russell Ira Crowe (born 7 April 1964) is an actor. He was born in New Zealand, spent ten years of his childhood in Australia, and moved there permanently at age twenty one. He came to international attention for his role as Roman General Maxi ...

has stated that he is a fan of Kavanagh. He commented: "I like the clarity and the emotiveness of Kavanagh. I like how he combines the kind of mystic into really clear, evocative work that can make you glad you are alive". On 24 February 2002, after winning the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role

Best Actor in a Leading Role is a British Academy Film Award presented annually by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) to recognize an actor who has delivered an outstanding leading performance in a film.

Superlatives

Note: ...

for his performance in '' A Beautiful Mind'', Crowe quoted Kavanagh during his acceptance speech at the 55th British Academy Film Awards. When he became aware that the Kavanagh quote had been cut from the final broadcast, Crowe became aggressive with the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Irish Times

''The Irish Times'' is an Irish daily broadsheet newspaper and online digital publication. It launched on 29 March 1859. The editor is Ruadhán Mac Cormaic. It is published every day except Sundays. ''The Irish Times'' is considered a newspaper ...

'' compiled a list of favourite Irish poems in 2000, ten of Kavanagh's poems were in the top 50, and he was rated the second favourite poet behind W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

. Kavanagh's poem "On Raglan Road

"On Raglan Road" is a well-known Irish song from a poem written by Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh named after Raglan Road in Ballsbridge, Dublin. In the poem, the speaker recalls, while walking on a "quiet street," a love affair that he had with ...

", set to the traditional air "Fáinne Geal an Lae", composed by Thomas Connellan

Thomas Connellan ( – 1698) was an Irish composer.

Connellan was born about 1640/1645 at Cloonamahon, County Sligo. Both he and his brother, William Connellan became harpers. Thomas is famous for the words and music of ''Molly MacAlpin'' ...

in the 17th century, has been performed by numerous artists as diverse as Van Morrison

Sir George Ivan Morrison (born 31 August 1945), known professionally as Van Morrison, is a Northern Irish singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist whose recording career spans seven decades. He has won two Grammy Awards.

As a teenager in t ...

, Luke Kelly

Luke Kelly (17 November 1940 – 30 January 1984) was an Irish singer, folk musician and actor from Dublin, Ireland. Born into a working-class household in Dublin city, Kelly moved to England in his late teens and by his early 20s had become i ...

, Dire Straits

Dire Straits were a British rock band formed in London in 1977 by Mark Knopfler (lead vocals and lead guitar), David Knopfler (rhythm guitar and backing vocals), John Illsley (bass guitar and backing vocals) and Pick Withers (drums and percuss ...

, Billy Bragg

Stephen William Bragg (born 20 December 1957) is an English singer-songwriter and left-wing activist. His music blends elements of folk music, punk rock and protest songs, with lyrics that mostly span political or romantic themes. His music is ...

, Sinéad O'Connor, Joan Osborne

Joan Elizabeth Osborne (born July 8, 1962) is an American singer, songwriter, and interpreter of music, having recorded and performed in various popular American musical genres including rock, pop, soul, R&B, blues, and country. She is best kn ...

and many others.

There is a statue of Kavanagh beside Dublin's Grand Canal, inspired by his poem "Lines written on a Seat on the Grand Canal, Dublin":

Fleet Street

Fleet Street is a major street mostly in the City of London. It runs west to east from Temple Bar at the boundary with the City of Westminster to Ludgate Circus at the site of the London Wall and the River Fleet from which the street was na ...

. There is also a statue of Patrick Kavanagh located outside the Irish pub and restaurant, Raglan Road, at Walt Disney World

The Walt Disney World Resort, also called Walt Disney World or Disney World, is an entertainment resort complex in Bay Lake and Lake Buena Vista, Florida, United States, near the cities of Orlando and Kissimmee. Opened on October 1, 1971, th ...

's Downtown Disney in Orlando, Florida. His poetic tribute to his friend the Irish American sculptor Jerome Connor

Jerome Connor (23 February 1874 in Coumduff, Annascaul, County Kerry – 21 August 1943 in Dublin) was an Irish sculptor.

Life

In 1888, he emigrated to Holyoke, Massachusetts. His father was a stonemason, which led to Connor's jobs in New York ...

was used in the plaque overlooking Dublin's Phoenix Park

The Phoenix Park ( ga, Páirc an Fhionnuisce) is a large urban park in Dublin, Ireland, lying west of the city centre, north of the River Liffey. Its perimeter wall encloses of recreational space. It includes large areas of grassland and tre ...

dedicated to Connor.

The Patrick Kavanagh Poetry Award is presented each year for an unpublished collection of poems. The annual Patrick Kavanagh Weekend takes place on the last weekend in September in Inniskeen

Inniskeen, officially Inishkeen (), is a small village, townland and parish in County Monaghan, Ireland, close to the County Louth and County Armagh borders. The village is located about from Dundalk, from Carrickmacross, and from Crossmaglen ...

, County Monaghan

County Monaghan ( ; ga, Contae Mhuineacháin) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Ulster and is part of Border strategic planning area of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town of Monaghan. Monaghan County Cou ...

, Ireland. The Patrick Kavanagh Centre, an interpretative centre set up to commemorate the poet, is located in Inniskeen.

Kavanagh Archive

In 1986, Peter Kavanagh negotiated the sale of Patrick Kavanagh's papers as well as a large collection of his own work devoted to the late poet toUniversity College Dublin

University College Dublin (commonly referred to as UCD) ( ga, Coláiste na hOllscoile, Baile Átha Cliath) is a public research university in Dublin, Ireland, and a collegiate university, member institution of the National University of Ireland ...

. The purchase was enabled by a public appeal for funds by the late Professor Gus Martin. Peter included in the sale his original hand press which he had built. The archive is housed in a special collections room in UCD's library, and the hand press is on loan to the Patrick Kavanagh Centre, Inniskeen

Inniskeen, officially Inishkeen (), is a small village, townland and parish in County Monaghan, Ireland, close to the County Louth and County Armagh borders. The village is located about from Dundalk, from Carrickmacross, and from Crossmaglen ...

.

The contents include:

* Early literary material containing verses, novels, prose writing and other publications; family correspondence containing letters to Cecilia Kavanagh and Peter Kavanagh; letters to Patrick Kavanagh from various sources (1926–40).

* Later literary material containing verses, novels, articles, lectures, published works, galley page proofs, Kavanagh’s Weekly, and adaptations of Kavanagh’s work (1940–67).

* Documents concerning libel case of ''Kavanagh v The Leader'' (1952–54).

* Personal correspondence, including with his sisters, Peter Kavanagh, Katherine Barry Moloney (1947–67).

* Printed material, press cuttings, publications, personal memorabilia, and tape recordings (1940–67).

Peter Kavanagh's papers include thesis, plays, autobiographical writing, and printed material, personal and general correspondence memorabilia, tape recordings, galley proofs (1941–82) and family memorabilia (1872–1967).

Copyright

Ownership of the copyright is vested in Trustees of The Patrick and Katherine Kavanagh Trust by virtue of the terms of the will of the late Kathleen Kavanagh, widow of the poet, who in turn became entitled to the copyright on the death of her husband. The proceeds of the trust are used to support deserving writers. The Trustees areLeland Bardwell

Constan Olive Leland Bardwell (25 February 1922 – 28 June 2016) was an Irish poet, novelist, and playwright. She was part of the literary scene in London and later Dublin, where she was an editor of literary magazines ''Hibernia'' and ''C ...

, Patrick MacEntee, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin (; born 1942) is an Irish poet and academic. She was the Ireland Professor of Poetry (2016–19).

Biography

Ní Chuilleanáin was born in Cork in 1942. She is the daughter of Eilís Dillon and Professor Cormac Ó Cuil ...

, Eunan O'Halpin

Eunan O'Halpin ( ) is Bank of Ireland Professor of Contemporary Irish History at Trinity College Dublin. He was educated at Gonzaga College, Dublin, received his BA and MA from University College Dublin and received a PhD from the University of ...

, and Macdara Woods

Macdara Woods (1942 – 15 June 2018) was an Irish poet.

Biography

Woods was born in Dublin, where he attended Gonzaga College and then University College Dublin. He married the poet Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin. They had one son, Niall, a musician. ...

. This was disputed by the late Peter Kavanagh who continued publishing his work after Patrick's death. This dispute led some books to go out of print. Most of his work is now available in the UK and Ireland but the status in the United States is more uncertain.

Works

Poetry

*1936 – ''Ploughman and Other Poems'' *1942 – ''The Great Hunger'' *1947 – ''A Soul For Sale'' *1958 – ''Recent Poems'' *1960 – ''Come Dance with Kitty Stobling and Other Poems'' *1964 – ''Collected Poems'' () *1972 – ''The Complete Poems of Patrick Kavanagh'', edited by Peter Kavanagh *1978 – ''Lough Derg'' *1996 – ''Selected Poems'', edited by Antoinette Quinn () *2004 – ''Collected Poems'', edited by Antoinette Quinn ()Prose

*1938 – ''The Green Fool'' *1948 – ''Tarry Flynn'' () *1964 – ''Self Portrait'' – recording *1967 – ''Collected Pruse'' *1971 – ''November Haggard'' a collection of prose and poetry edited by Peter Kavanagh *1978 – ''By Night Unstarred''. A conflated novel, completed by Peter Kavanagh *2002 – ''A Poet's Country: Selected Prose'', edited by Antoinette Quinn ()Dramatisations

*1966 – ''Tarry Flynn'', adapted by P. J. O'Connor *1986 – ''The Great Hunger'', adapted by Tom Mac Intyre *1992 – ''Out of That Childhood Country'' John McArdle’s (1992), co-written with his brother Tommy and Eugene MacCabe, is about Kavanagh’s youth loosely based on his writings. *1997 – ''Tarry Flynn'', adapted by Conall Morrison (modern dance and play) *2004 – ''The Green Fool'', adapted by Upstate Theatre ProjectReferences

Further reading

* Peter Kavanagh (ed.), ''Lapped Furrows'', correspondence with his brother as well as a memoir by Sister Celia, his sister (a nun) (1969) * Peter Kavanagh, ''Garden of the Golden Apples, A Bibliography'' (1971) * Alan Warner, ''Clay is the Word: Patrick Kavanagh 1904–1967'' (Dolmen, 1973) * O'Brien, Darcy, ''Patrick Kavanagh'' (Bucknell University Press, 1975) * Peter Kavanagh, ''Sacred Keeper'', a biography (1978) * John Nemo, ''Patrick Kavanagh'' (1979) * Peter Kavanagh (ed.), ''Patrick Kavanagh: Man and Poet'' (1986) * Antoinette Quinn, ''Patrick Kavanagh: Born Again Romantic'' (1991) * Antoinette Quinn, ''Patrick Kavanagh: A Biography'' (Gill & Macmillan Ltd, 2001; / 0-7171-2651-X) * Allison, Jonathan, ''Patrick Kavanagh: A Reference Guide'' (New York City: G. K. Hall, 1996) * Sr. Una Agnew, ''The Mystical Imagination of Patrick Kavanagh: A Buttonhole in Heaven?'' (Columba Press, 1999; ) * Peter Kavanagh, ''Patrick Kavanagh: A Life Chronicle'', a biography (2000) * Tom Stack, ''No Earthly Estate: The Religious Poetry of Patrick Kavanagh'' (2002) * John Jordan "Mr Kavanagh's Progress", "Obituary for Patrick Kavanagh", "From a small townland in Monaghan", "To Kill a Mockingbird", "By Night Unstarred", "Sacred Keeper", in ''Crystal Clear: The Selected Prose of John Jordan'', (ed) Hugh McFadden (Lilliput Press, Dublin, 2006) * Hugh McFadden, "Kavanagh - beyond the Celtic Mist". Irish Independent. 16 October 2004. Retrieved 13 August 2010. * Andrea Galgano, "Il cielo di Patrick Kavanagh", "Mosaico" (Aracne, Roma, 2013, pp. 289–292)External links

Profile and poems at the Poetry Archive

Poetry Foundation profile and poems

from the Patrick Kavanagh Trust

The Patrick Kavanagh Centre

RTÉ

(RTÉ) (; Irish language, Irish for "Radio & Television of Ireland") is the Public broadcaster, national broadcaster of Republic of Ireland, Ireland headquartered in Dublin. It both produces and broadcasts programmes on RTÉ Television, telev ...

libraries and archives. "Portrait of Patrick Kavanagh".Patrick Kavanagh Grand Canal South Bank Seat

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kavanagh, Patrick 1904 births 1967 deaths Claddagh Records artists Gaelic football goalkeepers Inniskeen Grattans Gaelic footballers Irish male novelists People from County Monaghan 20th-century Irish poets 20th-century male writers