Partition of Ireland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The partition of Ireland ( ga, críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the

The partition of Ireland ( ga, críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the

During the 19th century, the Irish nationalist

During the 19th century, the Irish nationalist

.

The Making of Ireland: From Ancient Times to the Present

' , Routledge, 1998, p. 326 The

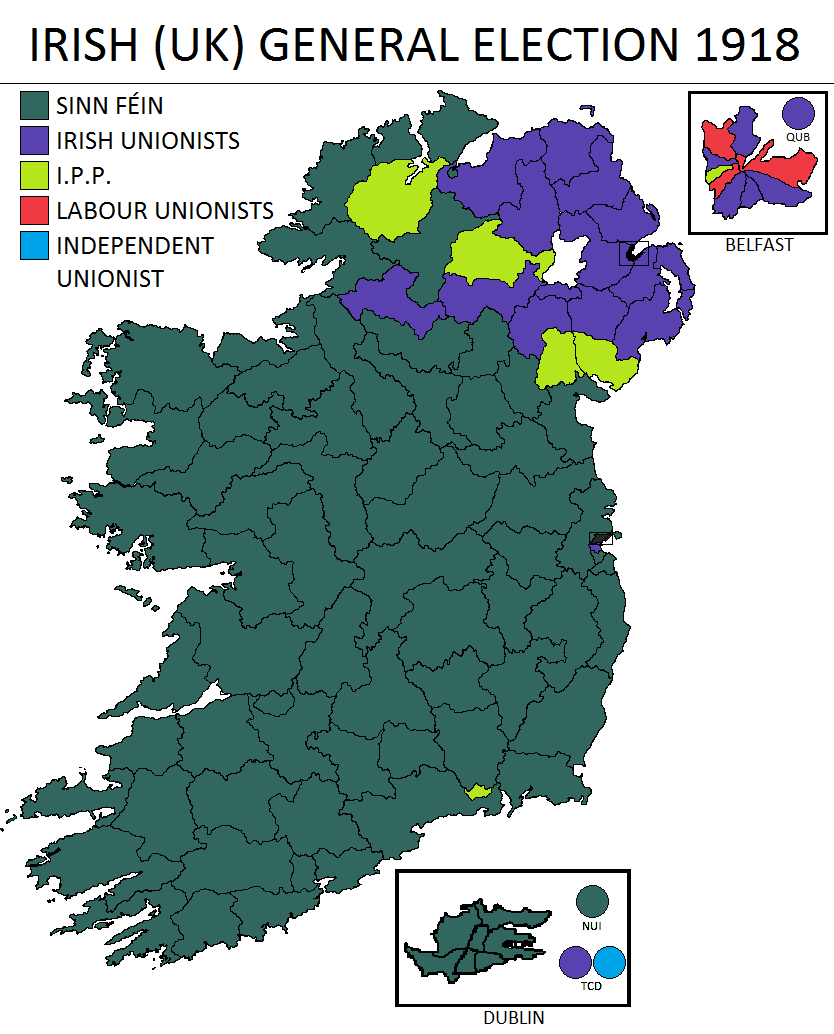

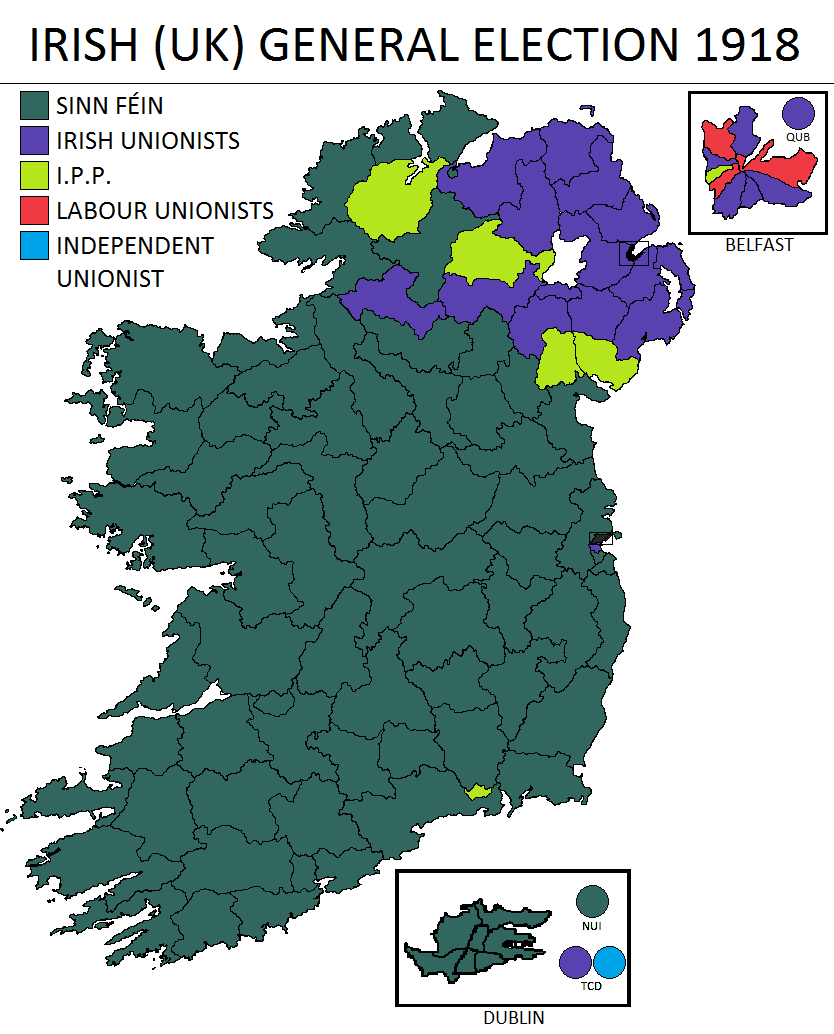

In the December 1918 general election, Sinn Féin won the overwhelming majority of Irish seats. In line with their manifesto, Sinn Féin's elected members boycotted the British parliament and founded a separate Irish parliament (

In the December 1918 general election, Sinn Féin won the overwhelming majority of Irish seats. In line with their manifesto, Sinn Féin's elected members boycotted the British parliament and founded a separate Irish parliament (

Dáil Éireann – Volume 7 – 20 June 1924 The Boundary Question – Debate Resumed

. Under Article 12 of the Treaty, Northern Ireland could exercise its opt-out by presenting an address to the King, requesting not to be part of the Irish Free State. Once the treaty was ratified, the Houses of

The treaty "went through the motions of including Northern Ireland within the Irish Free State while offering it the provision to opt out". It was certain that Northern Ireland would exercise its opt out. The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Sir James Craig, speaking in the

The treaty "went through the motions of including Northern Ireland within the Irish Free State while offering it the provision to opt out". It was certain that Northern Ireland would exercise its opt out. The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Sir James Craig, speaking in the

The Anglo-Irish Treaty (signed 6 December 1921) contained a provision (Article 12) that would establish a boundary commission, which would determine the border "...in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions...". In October 1922 the Irish Free State government set up the North East Boundary Bureau to prepare its case for the Boundary Commission. The Bureau conducted extensive work but the Commission refused to consider its work, which amounted to 56 boxes of files. Most leaders in the Free State, both pro- and anti-treaty, assumed that the commission would award largely nationalist areas such as County Fermanagh, County Tyrone, South Londonderry, South Armagh and South Down and the City of Derry to the Free State, and that the remnant of Northern Ireland would not be economically viable and would eventually opt for union with the rest of the island as well. The terms of Article 12 were ambiguous, no timetable was established or method to determine the wishes of the inhabitants. Article 12 did not call for a plebiscite or specify a time for the convening of the commission (the commission did not meet until November 1924). In Southern Ireland the new Parliament fiercely debated the terms of the Treaty yet devoted a small amount of time on the issue of partition, just nine out of 338 transcript pages. The commission's final report recommended only minor transfers of territory, and in both directions.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty (signed 6 December 1921) contained a provision (Article 12) that would establish a boundary commission, which would determine the border "...in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions...". In October 1922 the Irish Free State government set up the North East Boundary Bureau to prepare its case for the Boundary Commission. The Bureau conducted extensive work but the Commission refused to consider its work, which amounted to 56 boxes of files. Most leaders in the Free State, both pro- and anti-treaty, assumed that the commission would award largely nationalist areas such as County Fermanagh, County Tyrone, South Londonderry, South Armagh and South Down and the City of Derry to the Free State, and that the remnant of Northern Ireland would not be economically viable and would eventually opt for union with the rest of the island as well. The terms of Article 12 were ambiguous, no timetable was established or method to determine the wishes of the inhabitants. Article 12 did not call for a plebiscite or specify a time for the convening of the commission (the commission did not meet until November 1924). In Southern Ireland the new Parliament fiercely debated the terms of the Treaty yet devoted a small amount of time on the issue of partition, just nine out of 338 transcript pages. The commission's final report recommended only minor transfers of territory, and in both directions.

The Unionist

The Unionist

The Partition of Ireland

(Workers Solidarity Movement – An anarchist organisation which supports the IRA)

(Marxists Internet Archive)

(The Blanket) *Sean O Mearthaile

''Partition — what it means for Irish workers''

(The ETEXT Archives)

Northern Ireland Timeline: Partition: Civil war 1922–1923

(BBC History).

(LSE Library).

Towards a Lasting Peace in Ireland

(

History of the Republic of Ireland

(History World) {{DEFAULTSORT:Partition Of Ireland Politics of Ireland History of Ireland (1801–1923) 1921 in Ireland History of Northern Ireland Partition (politics) May 1921 events Constitutional history of Northern Ireland

The partition of Ireland ( ga, críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the

The partition of Ireland ( ga, críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in the British Isles that existed between 1801 and 1922, when it included all of Ireland. It was established by the Acts of Union 1800, which merged the Kingdom of Great B ...

divided Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

and Southern Ireland

Southern Ireland, South Ireland or South of Ireland may refer to:

*The southern part of the island of Ireland

*Southern Ireland (1921–1922), a former constituent part of the United Kingdom

*Republic of Ireland, which is sometimes referred to as ...

. It was enacted on 3 May 1921 under the Government of Ireland Act 1920

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 (10 & 11 Geo. 5 c. 67) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act's long title was "An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland"; it is also known as the Fourth Home Rule Bill ...

. The Act intended both territories to remain within the United Kingdom and contained provisions for their eventual reunification

A political union is a type of political entity which is composed of, or created from, smaller polities, or the process which achieves this. These smaller polities are usually called federated states and federal territories in a federal governm ...

. The smaller Northern Ireland was duly created with a devolved

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territories h ...

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

(Home Rule) and remained part of the UK. The larger Southern Ireland was not recognised by most of its citizens, who instead recognised the self-declared 32-county Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( ga, Poblacht na hÉireann or ) was an unrecognised revolutionary state that declared its independence from the United Kingdom in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdiction over the whole island of Ireland, but by ...

. On 6 December 1922, a year after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

, the territory of Southern Ireland left the UK and became the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

, now the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. A ...

.

The territory that became Northern Ireland, within the Irish province of Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

, had a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

and Unionist majority who wanted to maintain ties to Britain. This was largely due to 17th-century British colonisation. However, it also had a significant minority of Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and Irish nationalists

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

. The rest of Ireland had a Catholic, nationalist majority who wanted self-governance or independence. The Irish Home Rule movement

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the e ...

compelled the British government to introduce bills that would give Ireland a devolved government within the UK (home rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

). This led to the Home Rule Crisis

The Home Rule Crisis was a political and military crisis in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that followed the introduction of the Third Home Rule Bill in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom in 1912. Unionists in Ulster, d ...

(1912–14), when Ulster unionists/loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

founded a paramilitary movement, the Ulster Volunteers

The Ulster Volunteers was an Irish unionist, loyalist paramilitary organisation founded in 1912 to block domestic self-government ("Home Rule") for Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom. The Ulster Volunteers were based in the ...

, to prevent Ulster being ruled by an Irish government. The British government proposed to exclude all or part of Ulster, but the crisis was interrupted by the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

(1914–18). Support for Irish independence grew during the war.

Irish republican

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The develop ...

party Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

won the vast majority of Irish seats in the 1918 election. They formed a separate Irish parliament and declared an independent Irish Republic covering the whole island. This led to the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

(1919–21), a guerrilla conflict between the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

(IRA) and British forces. In 1920 the British government introduced another bill to create two devolved governments: one for six northern counties (Northern Ireland) and one for the rest of the island (Southern Ireland). This was passed as the Government of Ireland Act, and came into force as a '' fait accompli'' on 3 May 1921. Following the 1921 elections, Ulster unionists formed a Northern Ireland government. A Southern government was not formed, as republicans recognised the Irish Republic instead. During 1920–22, in what became Northern Ireland, partition was accompanied by violence "in defence or opposition to the new settlement" – see The Troubles in Northern Ireland (1920–1922)

The Troubles of the 1920s was a period of conflict in what is now Northern Ireland from June 1920 until June 1922, during and after the Irish War of Independence and the partition of Ireland. It was mainly a communal conflict between Protestan ...

. The capital, Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

, saw "savage and unprecedented" communal violence, mainly between Protestant and Catholic civilians. More than 500 were killed and more than 10,000 became refugees, most of them from the Catholic minority.Lynch (2019), pp. 171–176

The War of Independence resulted in a truce in July 1921 and led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty that December. Under the Treaty, the territory of Southern Ireland would leave the UK and become the Irish Free State. Northern Ireland's parliament could vote it in or out of the Free State, and a commission could then redraw or confirm the provisional border. In early 1922, the IRA launched a failed offensive into border areas of Northern Ireland. The Northern government chose to remain in the UK. The Boundary Commission

A boundary commission is a legal entity that determines borders of nations, states, constituencies.

Notable boundary commissions have included:

* Afghan Boundary Commission, an Anglo-Russian Boundary Commission, of 1885 and 1893, delineated the no ...

proposed small changes to the border in 1925, but they were not implemented.

Since partition, Irish nationalists/republicans continue to seek a united independent Ireland, while Ulster unionists/loyalists want Northern Ireland to remain in the UK. The Unionist governments of Northern Ireland were accused of discrimination against the Irish nationalist and Catholic minority. A campaign to end discrimination was opposed by loyalists who said it was a republican front.Maney, Gregory. "The Paradox of Reform: The Civil Rights Movement in Northern Ireland", in ''Nonviolent Conflict and Civil Resistance''. Emerald Group Publishing, 2012. p. 15 This sparked the Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an " ...

(c. 1969–1998), a thirty-year conflict in which more than 3,500 people were killed. Under the 1998 Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA), or Belfast Agreement ( ga, Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta or ; Ulster-Scots: or ), is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April 1998 that ended most of the violence of The Troubles, a political conflict in No ...

, the Irish and British governments and the main parties agreed to a power-sharing government in Northern Ireland, and that the status of Northern Ireland would not change without the consent of a majority of its population. The treaty also reaffirmed an open border

An open border is a border that enables free movement of people (and often of goods) between jurisdictions with no restrictions on movement and is lacking substantive border control. A border may be an open border due to intentional legislation ...

between both jurisdictions.

Background

Irish Home Rule movement

During the 19th century, the Irish nationalist

During the 19th century, the Irish nationalist Home Rule movement

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a State (polity), state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers o ...

campaigned for Ireland to have self-government

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form of ...

while remaining part of the United Kingdom. The nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish national ...

won most Irish seats in the 1885 general election. It then held the balance of power in the British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, and entered into an alliance with the Liberals. IPP leader Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1875 to 1891, also acting as Leader of the Home Rule League from 1880 to 1882 and then Leader of the ...

convinced British Prime Minister William Gladstone to introduce the First Irish Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Bill 1886, commonly known as the First Home Rule Bill, was the first major attempt made by a British government to enact a law creating home rule for part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was in ...

in 1886. Protestant unionists in Ireland opposed the Bill, fearing industrial decline

Deindustrialization is a process of social and economic change caused by the removal or reduction of industrial capacity or activity in a country or region, especially of heavy industry or manufacturing industry.

There are different interpre ...

and religious persecution of Protestants by a Catholic-dominated Irish government. English Conservative politician Lord Randolph Churchill

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill (13 February 1849 – 24 January 1895) was a British statesman. Churchill was a Tory radical and coined the term 'Tory democracy'. He inspired a generation of party managers, created the National Union of ...

proclaimed: "the Orange card is the one to play", in reference to the Protestant Orange Order. The belief was later expressed in the popular slogan, ''"Home Rule means Rome Rule

"Rome Rule" was a term used by Irish unionists to describe their belief that with the passage of a Home Rule Bill, the Roman Catholic Church would gain political power over their interests in Ireland. The slogan was popularised by the Radical MP ...

"''.Edgar Holt ''Protest in Arms'' Ch. III Orange Drums, pp. 32–33, Putnam London (1960) Partly in reaction to the Bill, there were riots in Belfast, as Protestant unionists attacked the city's Catholic nationalist minority. The Bill was defeated in the Commons.Two home rule Bills.

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

Gladstone introduced a Second Irish Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Bill 1893 (known generally as the Second Home Rule Bill) was the second attempt made by Liberal Party leader William Ewart Gladstone, as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, to enact a system of home rule for Ireland. ...

in 1892. The Irish Unionist Alliance

The Irish Unionist Alliance (IUA), also known as the Irish Unionist Party, Irish Unionists or simply the Unionists, was a unionist political party founded in Ireland in 1891 from a merger of the Irish Conservative Party and the Irish Loyal and ...

had been formed to oppose home rule, and the Bill sparked mass unionist protests. In response, Liberal Unionist

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

leader Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the C ...

called for a separate provincial government for Ulster where Protestant unionists were a majority. Irish unionists assembled at conventions in Dublin and Belfast to oppose both the Bill and the proposed partition. The unionist MP Horace Plunkett

Sir Horace Curzon Plunkett (24 October 1854 – 26 March 1932), was an Anglo-Irish agricultural reformer, pioneer of agricultural cooperatives, Unionist MP, supporter of Home Rule, Irish Senator and author.

Plunkett, a younger brother of Jo ...

, who would later support home rule, opposed it in the 1890s because of the dangers of partition. Although the Bill was approved by the Commons, it was defeated in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

.

Home Rule Crisis

Following the December 1910 election, the Irish Parliamentary Party again agreed to support a Liberal government if it introduced another home rule bill.James F. Lydon,The Making of Ireland: From Ancient Times to the Present

' , Routledge, 1998, p. 326 The

Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5 c. 13) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two Houses of Parlia ...

meant the House of Lords could no longer veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

bills passed by the Commons, but only delay them for up to two years. British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

introduced the Third Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 (4 & 5 Geo. 5 c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home rule (self-governm ...

in April 1912. Unionists opposed the Bill, but argued that if Home Rule could not be stopped then all or part of Ulster should be excluded from it. Irish nationalists opposed partition, although some were willing to accept Ulster having some self-governance within a self-governing Ireland ("Home Rule within Home Rule"). Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

made his feelings about the possibility of the partition of Ireland clear: "Whatever Ulster's right may be, she cannot stand in the way of the whole of the rest of Ireland. Half a province cannot impose a permanent veto on the nation. Half a province cannot obstruct forever the reconciliation between the British and Irish democracies." In September 1912, more than 500,000 Unionists signed the Ulster Covenant

Ulster's Solemn League and Covenant, commonly known as the Ulster Covenant, was signed by nearly 500,000 people on and before 28 September 1912, in protest against the Third Home Rule Bill introduced by the British Government in the same year. ...

, pledging to oppose Home Rule by any means and to defy any Irish government. They founded a large paramilitary movement, the Ulster Volunteers

The Ulster Volunteers was an Irish unionist, loyalist paramilitary organisation founded in 1912 to block domestic self-government ("Home Rule") for Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom. The Ulster Volunteers were based in the ...

, to prevent Ulster becoming part of a self-governing Ireland. They also threatened to establish a Provisional Ulster Government. In response, Irish nationalists founded the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers ( ga, Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force or Irish Volunteer Army, was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in respon ...

to ensure Home Rule was implemented. The Ulster Volunteers smuggled 25,000 rifles and three million rounds of ammunition into Ulster from the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, in the Larne gun-running

The Larne gun-running was a major gun smuggling operation organised in April 1914 in Ireland by Major Frederick H. Crawford and Captain Wilfrid Spender for the Ulster Unionist Council to equip the Ulster Volunteer Force. The operation involved ...

of April 1914. The Irish Volunteers also smuggled weaponry from Germany in the Howth gun-running

The Howth gun-running ( ) involved the delivery of 1,500 Mauser rifles to the Irish Volunteers at Howth harbour in Ireland on 26 July 1914. The unloading of guns from a private yacht during daylight hours attracted a crowd, and the authorities or ...

that July. Ireland seemed to be on the brink of civil war. Three border boundary options were proposed.

On 20 March 1914, in the "Curragh incident

The Curragh incident of 20 March 1914, sometimes known as the Curragh mutiny, occurred in the Curragh, County Kildare, Ireland. The Curragh Camp was then the main base for the British Army in Ireland, which at the time still formed part of the ...

", many of the highest-ranking British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

officers in Ireland threatened to resign rather than deploy against the Ulster Volunteers. This meant that the British government could legislate for Home Rule but could not be sure of implementing it. In May 1914, the British government introduced an Amending Bill to allow for 'Ulster' to be excluded from Home Rule. There was then debate over how much of Ulster should be excluded and for how long, and whether to hold referendums in each county. Some Ulster unionists were willing to tolerate the 'loss' of some mainly-Catholic areas of the province. In July 1914, King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

called the Buckingham Palace Conference to allow Unionists and Nationalists to come together and discuss the issue of partition, but the conference achieved little.

First World War

The Home Rule Crisis was interrupted by the outbreak of theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in August 1914, and Ireland's involvement in it. Asquith abandoned his Amending Bill, and instead rushed through a new bill, the Suspensory Act 1914

{{Infobox UK legislation

, short_title = Suspensory Act 1914

, parliament = Parliament of the United Kingdom

, long_title = An Act to suspend the operation of the Government of Ireland Act, 1914, and the Welsh Church ...

, which received Royal Assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in other ...

together with the Home Rule Bill (now Government of Ireland Act 1914) on 18 September 1914. The Suspensory Act ensured that Home Rule would be postponed for the duration of the war with the exclusion of Ulster still to be decided.

During the First World War, support grew for full Irish independence, which had been advocated by Irish republicans

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The developm ...

. In April 1916, republicans took the opportunity of the war to launch a rebellion against British rule, the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the a ...

. It was crushed after a week of heavy fighting in Dublin. The harsh British reaction to the Rising fuelled support for independence, with republican party Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

winning four by-elections in 1917.

The British parliament called the Irish Convention

The Irish Convention was an assembly which sat in Dublin, Ireland from July 1917 until March 1918 to address the '' Irish question'' and other constitutional problems relating to an early enactment of self-government for Ireland, to debate its wi ...

in an attempt to find a solution to its Irish Question

The Irish question was the issue debated primarily among the British government from the early 19th century until the 1920s of how to respond to Irish nationalism and the calls for Irish independence.

The phrase came to prominence as a result ...

. It sat in Dublin from July 1917 until March 1918, and comprised both Irish nationalist and Unionist politicians. It ended with a report, supported by nationalist and southern unionist members, calling for the establishment of an all-Ireland parliament consisting of two houses with special provisions for Ulster unionists. The report was, however, rejected by the Ulster unionist members, and Sinn Féin had not taken part in the proceedings, meaning the convention was a failure.

In 1918, the British government attempted to impose conscription in Ireland and argued there could be no Home Rule without it. This sparked outrage in Ireland and further galvanised support for the republicans.

1918 General Election, Long Committee, Violence

In the December 1918 general election, Sinn Féin won the overwhelming majority of Irish seats. In line with their manifesto, Sinn Féin's elected members boycotted the British parliament and founded a separate Irish parliament (

In the December 1918 general election, Sinn Féin won the overwhelming majority of Irish seats. In line with their manifesto, Sinn Féin's elected members boycotted the British parliament and founded a separate Irish parliament (Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland read ...

), declaring an independent Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( ga, Poblacht na hÉireann or ) was an unrecognised revolutionary state that declared its independence from the United Kingdom in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdiction over the whole island of Ireland, but by ...

covering the whole island. Unionists, however, won most seats in northeastern Ulster and affirmed their continuing loyalty to the United Kingdom. Many Irish republicans blamed the British establishment for the sectarian divisions in Ireland, and believed that Ulster Unionist defiance would fade once British rule was ended.

The British authorities outlawed the Dáil in September 1919, and a guerrilla conflict developed as the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

(IRA) began attacking British forces. This became known as the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

.

Long Committee

In September 1919, British Prime MinisterDavid Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

tasked a committee with planning Home Rule for Ireland within the UK. Headed by English Unionist politician Walter Long, it was known as the 'Long Committee'. The makeup of the committee was Unionist in outlook and had no Nationalist representatives as members. James Craig (the future 1st Prime Minister of Northern Ireland

The prime minister of Northern Ireland was the head of the Government of Northern Ireland between 1921 and 1972. No such office was provided for in the Government of Ireland Act 1920; however, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, as with governo ...

) and his associates were the only Irishmen consulted during this time. During the summer of 1919, Long visited Ireland several times, using his yacht as a meeting place to discuss the "Irish question" with the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (), or more formally Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland, was the title of the chief governor of Ireland from the Williamite Wars of 1690 until the Partition of Ireland in 1922. This spanned the Kingdo ...

John French and the Chief Secretary for Ireland Ian Macpherson.Moore, pg 19

Prior to the first meeting of the committee, Long sent a memorandum to the British Prime Minister recommending two parliaments for Ireland (24 September 1919). That memorandum formed the basis of the legislation that partitioned Ireland - the Government of Ireland Act 1920. At the first meeting of the committee (15 October 1919) it was decided that two devolved governments should be established — one for the nine counties of Ulster and one for the rest of Ireland, together with a Council of Ireland

The Council of Ireland was a statutory body established under the Government of Ireland Act 1920 as an all-Ireland law-making authority with limited jurisdiction, initially over both Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland, and later solely over ...

for the "encouragement of Irish unity". The Long Committee felt that the nine-county proposal "will enormously minimise the partition issue...it minimises the division of Ireland on purely religious lines. The two religions would not be unevenly balanced in the Parliament of Northern Ireland." Most northern unionists wanted the territory of the Ulster government to be reduced to six counties, so that it would have a larger Protestant/Unionist majority. Long offered the Committee members a deal - "that the Six Counties ... should be theirs for good ... and no interference with the boundaries".

Many Unionists feared that the territory would not last if it included too many Catholics and Irish Nationalists, any reduction in size would make the state unviable. The six counties of Antrim, Down, Armagh

Armagh ( ; ga, Ard Mhacha, , "Macha's height") is the county town of County Armagh and a city in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Pri ...

, Londonderry, Tyrone and Fermanagh

Historically, Fermanagh ( ga, Fir Manach), as opposed to the modern County Fermanagh, was a kingdom of Gaelic Ireland, associated geographically with present-day County Fermanagh. ''Fir Manach'' originally referred to a distinct kin group of a ...

comprised the maximum area unionists believed they could dominate. The remaining three Counties of Ulster had large Catholic majorities: Cavan

Cavan ( ; ) is the county town of County Cavan in Ireland. The town lies in Ulster, near the border with County Fermanagh in Northern Ireland. The town is bypassed by the main N3 road that links Dublin (to the south) with Enniskillen, Bally ...

81.5%, Donegal 78.9% and Monaghan

Monaghan ( ; ) is the county town of County Monaghan, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It also provides the name of its Civil parishes in Ireland, civil parish and Monaghan (barony), barony.

The population of the town as of the 2016 census was 7 ...

74.7%. However, in the 1921 elections in Northern Ireland, Fermanagh - Tyrone (which was a single constituency), the results were: 54.7% Nationalist / 45.3% Unionist. On 28 November 1921 both Tyrone and Fermanagh County Councils declared allegiance to the new Irish Parliament (Dail). On 2 December the Tyrone County Council publicly rejected the "...arbitrary, new-fangled, and universally unnatural boundary". They pledged to oppose the new border and to "make the fullest use of our rights to mollify it". On 21 December 1921 the Fermanagh County Council

Fermanagh County Council was the authority responsible for local government in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland, between 1899 and 1973. It was originally based at the Enniskillen Courthouse, but moved to County Buildings in East Bridge Street ...

passed the following resolution: "We, the County Council of Fermanagh, in view of the expressed desire of a large majority of people in this county, do not recognise the partition parliament in Belfast and do hereby direct our Secretary to hold no further communications with either Belfast or British Local Government Departments, and we pledge our allegiance to Dáil Éireann." Shortly afterwards both County Councils offices were seized by the Royal Irish Constabulary, the County officials expelled, and the County Councils dissolved.

Violence

In what became Northern Ireland, the process of partition was accompanied by violence, both "in defense or opposition to the new settlement".Lynch, Robert. ''The Partition of Ireland: 1918–1925''. Cambridge University Press, 2019. pp. 11, 100–101 The IRA carried out attacks on British forces in the north-east, but was less active than in the south of Ireland. Protestantloyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

in the north-east attacked the Catholic minority in reprisal for IRA actions. The January and June 1920 local elections saw Irish nationalists and republicans win control of Tyrone and Fermanagh county councils, which were to become part of Northern Ireland, while Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

had its first Irish nationalist mayor.Lynch, Robert. ''Revolutionary Ireland: 1912–25''. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015. pp. 97–98 In summer 1920, sectarian violence erupted in Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

and Derry, and there were mass burnings of Catholic property by loyalists in Lisburn

Lisburn (; ) is a city in Northern Ireland. It is southwest of Belfast city centre, on the River Lagan, which forms the boundary between County Antrim and County Down. First laid out in the 17th century by English and Welsh settlers, with ...

and Banbridge

Banbridge ( , ) is a town in County Down, Northern Ireland. It lies on the River Bann and the A1 road and is named after a bridge built over the River Bann in 1712. It is situated in the civil parish of Seapatrick and the historic barony of Iv ...

. Loyalists drove 8,000 "disloyal" co-workers from their jobs in the Belfast shipyards, all of them either Catholics or Protestant labour activists.Lynch (2019), pp. 92–93 In his Twelfth of July

The Twelfth (also called Orangemen's Day) is an Ulster Protestant celebration held on 12 July. It began in the late 18th century in Ulster. It celebrates the Glorious Revolution (1688) and victory of Protestant King William of Orange over C ...

speech, Unionist leader Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, 1st Baron Carson, Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, PC, Privy Council of Ireland, PC (Ire) (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Unionism in Ireland, Irish u ...

had called for loyalists to take matters into their own hands to defend Ulster, and had linked republicanism with socialism and the Catholic Church. In response to the expulsions and attacks on Catholics, the Dáil approved a boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict som ...

of Belfast goods and banks. The 'Belfast Boycott' was enforced by the IRA, who halted trains and lorries from Belfast and destroyed their goods. Conflict continued intermittently for two years, mostly in Belfast, which saw "savage and unprecedented" communal violence between Protestant and Catholic civilians. There was rioting, gun battles and bombings. Homes, business and churches were attacked and people were expelled from workplaces and from mixed neighbourhoods. The British Army was deployed and an Ulster Special Constabulary

The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC; commonly called the "B-Specials" or "B Men") was a quasi-military reserve special constable police force in what would later become Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, shortly before the part ...

(USC) was formed to help the regular police. The USC was almost wholly Protestant and some of its members carried out reprisal attacks on Catholics. From 1920 to 1922, more than 500 were killed in Northern Ireland and more than 10,000 became refugees, most of them Catholics.

Government of Ireland Act 1920

The British government introduced the Government of Ireland Bill in early 1920 and it passed through the stages in the British parliament that year. It would partition Ireland and create two self-governing territories within the UK, with their own bicameral parliaments, along with a Council of Ireland comprising members of both. Northern Ireland would comprise the aforesaid six northeastern counties, while Southern Ireland would comprise the rest of the island. The Act was passed on 11 November and receivedroyal assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in other ...

in December 1920. It would come into force on 3 May 1921.O'Day, Alan. ''Irish Home Rule, 1867–1921''. Manchester University Press, 1998. p. 299 Elections to the Northern and Southern parliaments were held on 24 May. Unionists won most seats in Northern Ireland. Its parliament first met on 7 June and formed its first devolved government, headed by Unionist Party leader James Craig. Republican and nationalist members refused to attend. King George V addressed the ceremonial opening of the Northern parliament on 22 June. Meanwhile, Sinn Féin won an overwhelming majority in the Southern Ireland election. They treated both as elections for Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland read ...

, and its elected members gave allegiance to the Dáil and Irish Republic, thus rendering "Southern Ireland" dead in the water. The Southern parliament met only once and was attended by four unionists.

On 5 May 1921, the Ulster Unionist leader Sir James Craig met with the President of Sinn Féin, Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (, ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of governm ...

, in secret near Dublin. Each restated his position and nothing new was agreed. On 10 May De Valera told the Dáil that the meeting "... was of no significance". In June that year, shortly before the truce that ended the Anglo-Irish War, David Lloyd George invited the Republic's President de Valera to talks in London on an equal footing with the new Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, James Craig, which de Valera attended. De Valera's policy in the ensuing negotiations was that the future of Ulster was an Irish-British matter to be resolved between two sovereign states, and that Craig should not attend. After the truce came into effect on 11 July, the USC was demobilized (July - November 1921). Speaking after the truce Lloyd George made it clear to de Valera, 'that the achievement of a republic through negotiation was impossible'.

On 20 July, Lloyd George further declared to de Valera that: In reply, de Valera wrote

Speaking in the House of Commons on the day the Act passed, Joe Devlin ( Nationalist Party) representing west Belfast, summed up the feelings of many Nationalists concerning partition and the setting up of a Northern Ireland Parliament while Ireland was in a deep state of unrest. Devlin stated:

Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule m ...

politician Charles Craig (the brother of Sir James Craig) made the feelings of many Unionists clear concerning the importance they placed on the passing of the Act and the establishment of a separate Parliament for Northern Ireland:

Anglo-Irish Treaty

The Irish War of Independence led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty, between the British government and representatives of the Irish Republic. Negotiations between the two sides were carried on between October to December 1921. The British delegation consisted of experienced parliamentarians/debaters such as Lloyd George,Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly ...

and Lord Birkenhead, they had clear advantages over the Sinn Fein negotiators. The Treaty was signed on 6 December 1921. Under its terms, the territory of Southern Ireland would leave the United Kingdom within one year and become a self-governing dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

called the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

. The treaty was given legal effect in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

through the Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922, and in Ireland by ratification by Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland read ...

. Under the former Act, at 1 pm on 6 December 1922, King George V (at a meeting of his Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

at Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

) signed a proclamation establishing the new Irish Free State.

Under the treaty, Northern Ireland's parliament could vote to ''opt out'' of the Free State.For further discussion, seeDáil Éireann – Volume 7 – 20 June 1924 The Boundary Question – Debate Resumed

. Under Article 12 of the Treaty, Northern Ireland could exercise its opt-out by presenting an address to the King, requesting not to be part of the Irish Free State. Once the treaty was ratified, the Houses of

Parliament of Northern Ireland

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore ord ...

had one month (dubbed the ''Ulster month'') to exercise this opt-out during which time the provisions of the Government of Ireland Act continued to apply in Northern Ireland. According to legal writer Austen Morgan, the wording of the treaty allowed the impression to be given that the Irish Free State temporarily included the whole island of Ireland, but legally the terms of the treaty applied only to the 26 counties, and the government of the Free State never had any powers—even in principle—in Northern Ireland. On 7 December 1922 the Parliament of Northern Ireland approved an address to George V, requesting that its territory not be included in the Irish Free State. This was presented to the king the following day and then entered into effect, in accordance with the provisions of Section 12 of the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act 1922. The treaty also allowed for a re-drawing of the border by a Boundary Commission

A boundary commission is a legal entity that determines borders of nations, states, constituencies.

Notable boundary commissions have included:

* Afghan Boundary Commission, an Anglo-Russian Boundary Commission, of 1885 and 1893, delineated the no ...

.Lynch (2019), pp.197–199

Unionist objections to the Treaty

Sir James Craig, the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland objected to aspects of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. In a letter toAusten Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly ...

dated 14 December 1921, he stated:

Nationalist objections to the Treaty

Michael Collins Michael Collins or Mike Collins most commonly refers to:

* Michael Collins (Irish leader) (1890–1922), Irish revolutionary leader, soldier, and politician

* Michael Collins (astronaut) (1930–2021), American astronaut, member of Apollo 11 and Ge ...

had negotiated the treaty and had it approved by the cabinet, the Dáil (on 7 January 1922 by 64–57), and by the people in national elections. Regardless of this, it was unacceptable to Éamon de Valera, who led the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War ( ga, Cogadh Cathartha na hÉireann; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United ...

to stop it. Collins was primarily responsible for drafting the constitution of the new Irish Free State, based on a commitment to democracy and rule by the majority.

De Valera's minority refused to be bound by the result. Collins now became the dominant figure in Irish politics, leaving de Valera on the outside. The main dispute centred on the proposed status as a dominion (as represented by the Oath of Allegiance and Fidelity) for Southern Ireland

Southern Ireland, South Ireland or South of Ireland may refer to:

*The southern part of the island of Ireland

*Southern Ireland (1921–1922), a former constituent part of the United Kingdom

*Republic of Ireland, which is sometimes referred to as ...

, rather than as an independent all-Ireland republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

, but continuing partition was a significant matter for Ulstermen like Seán MacEntee

Seán Francis MacEntee ( ga, Seán Mac an tSaoi; 23 August 1889 – 9 January 1984) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Tánaiste from 1959 to 1965, Minister for Social Welfare from 1957 to 1961, Minister for Health from 1957 to ...

, who spoke strongly against partition or re-partition of any kind. The pro-treaty side argued that the proposed Boundary Commission would give large swathes of Northern Ireland to the Free State, leaving the remaining territory too small to be viable. In October 1922, the Irish Free State government established the North-Eastern Boundary Bureau (NEBB) a government office which by 1925 had prepared 56 boxes of files to argue its case for areas of Northern Ireland to be transferred to the Free State.

De Valera had drafted his own preferred text of the treaty in December 1921, known as "Document No. 2". An "Addendum North East Ulster" indicates his acceptance of the 1920 partition for the time being, and of the rest of Treaty text as signed in regard to Northern Ireland:

Debate on Ulster Month

As described above, under the treaty it was provided that Northern Ireland would have a month – the "Ulster Month" – during which its Houses of Parliament could ''opt out'' of the Irish Free State. The Treaty was ambiguous on whether the month should run from the date the Anglo-Irish Treaty was ratified (in March 1922 via the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act) or the date that the Constitution of the Irish Free State was approved and the Free State established (6 December 1922).''The Times'', 22 March 1922 When the Irish Free State (Agreement) Bill was being debated on 21 March 1922, amendments were proposed which would have provided that the Ulster Month would run from the passing of the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act and not the Act that would establish the Irish Free State. Essentially, those who put down the amendments wished to bring forward the month during which Northern Ireland could exercise its right to opt out of the Irish Free State. They justified this view on the basis that if Northern Ireland could exercise its option to opt out at an earlier date, this would help to settle any state of anxiety or trouble on the new Irish border. Speaking in the House of Lords, theMarquess of Salisbury

Marquess of Salisbury is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1789 for the 7th Earl of Salisbury. Most of the holders of the title have been prominent in British political life over the last two centuries, particularly th ...

argued:

The British Government took the view that the Ulster Month should run from the date the Irish Free State was established and not beforehand, Viscount Peel for the Government remarking:

Viscount Peel continued by saying the government desired that there should be no ambiguity and would to add a proviso to the Irish Free State (Agreement) Bill providing that the Ulster Month should run from the passing of the Act establishing the Irish Free State. He further noted that the Parliament of Southern Ireland

The Parliament of Southern Ireland was a Home Rule legislature established by the British Government during the Irish War of Independence under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. It was designed to legislate for Southern Ireland,"Order in Coun ...

had agreed with that interpretation, and that Arthur Griffith

Arthur Joseph Griffith ( ga, Art Seosamh Ó Gríobhtha; 31 March 1871 – 12 August 1922) was an Irish writer, newspaper editor and politician who founded the political party Sinn Féin. He led the Irish delegation at the negotiations that prod ...

also wanted Northern Ireland to have a chance to see the Irish Free State Constitution before deciding.

Lord Birkenhead remarked in the Lords debate:

Northern Ireland opts out

The treaty "went through the motions of including Northern Ireland within the Irish Free State while offering it the provision to opt out". It was certain that Northern Ireland would exercise its opt out. The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Sir James Craig, speaking in the

The treaty "went through the motions of including Northern Ireland within the Irish Free State while offering it the provision to opt out". It was certain that Northern Ireland would exercise its opt out. The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Sir James Craig, speaking in the House of Commons of Northern Ireland

The House of Commons of Northern Ireland was the lower house of the Parliament of Northern Ireland created under the '' Government of Ireland Act 1920''. The upper house in the bicameral parliament was called the Senate. It was abolished w ...

in October 1922, said that "when the 6th of December is passed the month begins in which we will have to make the choice either to vote out or remain within the Free State." He said it was important that that choice be made as soon as possible after 6 December 1922 "in order that it may not go forth to the world that we had the slightest hesitation." On 7 December 1922, the day after the establishment of the Irish Free State, the Parliament of Northern Ireland resolved to make the following address to the King so as to opt out of the Irish Free State:

Discussion in the Parliament of the address was short. No division or vote was requested on the address, which was described as the Constitution Act and was then approved by the Senate of Northern Ireland

The Senate of Northern Ireland was the upper house of the Parliament of Northern Ireland created by the Government of Ireland Act 1920. It was abolished with the passing of the Northern Ireland Constitution Act 1973.

Powers

In practice the S ...

. Craig left for London with the memorial embodying the address on the night boat that evening, 7 December 1922. King George V received it the following day.

If the Houses of Parliament of Northern Ireland had not made such a declaration, under Article 14 of the Treaty, Northern Ireland, its Parliament and government would have continued in being but the Oireachtas

The Oireachtas (, ), sometimes referred to as Oireachtas Éireann, is the Bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The Oireachtas consists of:

*The President of Ireland

*The bicameralism, two houses of the Oireachtas ...

would have had jurisdiction to legislate for Northern Ireland in matters not delegated to Northern Ireland under the Government of Ireland Act. This never came to pass. On 13 December 1922, Craig addressed the Parliament of Northern Ireland, informing them that the King had accepted the Parliament's address and had informed the British and Free State governments.

Customs posts established

While the Irish Free State was established at the end of 1922, the Boundary Commission contemplated by the Treaty was not to meet until 1924. Things did not remain static during that gap. In April 1923, just four months after independence, the Irish Free State established customs barriers on the border. This was a significant step in consolidating the border. "While its final position was sidelined, its functional dimension was actually being underscored by the Free State with its imposition of a customs barrier".Boundary Commission

The Anglo-Irish Treaty (signed 6 December 1921) contained a provision (Article 12) that would establish a boundary commission, which would determine the border "...in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions...". In October 1922 the Irish Free State government set up the North East Boundary Bureau to prepare its case for the Boundary Commission. The Bureau conducted extensive work but the Commission refused to consider its work, which amounted to 56 boxes of files. Most leaders in the Free State, both pro- and anti-treaty, assumed that the commission would award largely nationalist areas such as County Fermanagh, County Tyrone, South Londonderry, South Armagh and South Down and the City of Derry to the Free State, and that the remnant of Northern Ireland would not be economically viable and would eventually opt for union with the rest of the island as well. The terms of Article 12 were ambiguous, no timetable was established or method to determine the wishes of the inhabitants. Article 12 did not call for a plebiscite or specify a time for the convening of the commission (the commission did not meet until November 1924). In Southern Ireland the new Parliament fiercely debated the terms of the Treaty yet devoted a small amount of time on the issue of partition, just nine out of 338 transcript pages. The commission's final report recommended only minor transfers of territory, and in both directions.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty (signed 6 December 1921) contained a provision (Article 12) that would establish a boundary commission, which would determine the border "...in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions...". In October 1922 the Irish Free State government set up the North East Boundary Bureau to prepare its case for the Boundary Commission. The Bureau conducted extensive work but the Commission refused to consider its work, which amounted to 56 boxes of files. Most leaders in the Free State, both pro- and anti-treaty, assumed that the commission would award largely nationalist areas such as County Fermanagh, County Tyrone, South Londonderry, South Armagh and South Down and the City of Derry to the Free State, and that the remnant of Northern Ireland would not be economically viable and would eventually opt for union with the rest of the island as well. The terms of Article 12 were ambiguous, no timetable was established or method to determine the wishes of the inhabitants. Article 12 did not call for a plebiscite or specify a time for the convening of the commission (the commission did not meet until November 1924). In Southern Ireland the new Parliament fiercely debated the terms of the Treaty yet devoted a small amount of time on the issue of partition, just nine out of 338 transcript pages. The commission's final report recommended only minor transfers of territory, and in both directions.

Make Up of the Commission

The Commission consisted of only three members Justice Richard Feetham, who represented the British government. Feetham served as chairman of the Commission. Feetham was a judge and graduate of Oxford. In 1923 Feetham was the legal advisor to the High Commissioner for South Africa.Eoin MacNeill

Eoin MacNeill ( ga, Eoin Mac Néill; born John McNeill; 15 May 1867 – 15 October 1945) was an Irish scholar, Irish language enthusiast, Gaelic revivalist, nationalist and politician who served as Minister for Education from 1922 to 1925, Ce ...

, the Irish governments Minister for Education, represented the Irish Government. In 1913 MacNeill established the Irish Volunteers and in 1916 issued countermanding orders instructing the Volunteers not to take part in the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the a ...

which greatly limited the numbers that turned out for the rising. On the day before his execution, the Rising leader Tom Clarke warned his wife about MacNeill: "I want you to see to it that our people know of his treachery to us. He must never be allowed back into the national life of this country, for so sure as he is, so sure he will act treacherously in a crisis. He is a weak man, but I know every effort will be made to whitewash him."

Joseph R. Fisher was appointed by the British Government to represent the Northern Ireland Government (after the Northern Government refused to name a member). It has been argued that the selection of Fisher ensured that only minimal (if any) changes would occur to the existing border. In a 1923 conversation with the 1st Prime Minister of Northern Ireland James Craig, British Prime Minister Baldwin commented on the future makeup of the Commission: "If the Commission should give away counties, then of course Ulster couldn't accept it and we should back her. But the Government will nominate a proper representative for Northern Ireland and we hope that he and Feetham will do what is right."

A small team of five assisted the Commission in its work. While Feetham was said to have kept his government contacts well informed on the Commissions work, MacNeill consulted with no one. With the leak of the Boundary Commission report (7 November 1925), MacNeill resigned from both the Commission and the Free State Government. As he departed the Free State Government admitted that MacNeill "wasn't the most suitable person to be a commissioner." The source of the leaked report was generally assumed to be made by Fisher. The Irish Free State, Northern Ireland and UK governments agreed to suppress the report and accept the ''status quo'', while the UK government agreed that the Free State would no longer have to pay its share of the UK's national debt (the British claim was £157 million). Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (, ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of governm ...

commented on the cancelation of the southern governments debt (referred to as the war debt) to the British: the Free State "sold Ulster natives for four pound a head, to clear a debt we did not owe."

The final agreement between the Irish Free State, Northern Ireland, and the United Kingdom (the inter-governmental Agreement) of 3 December 1925 was published later that day by Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

. The agreement was enacted by the "Ireland (Confirmation of Agreement) Act" and was passed unanimously by the British parliament on 8–9 December. The Dáil voted to approve the agreement, by a supplementary act, on 10 December 1925 by a vote of 71 to 20. With a separate agreement concluded by the three governments, the publication of Boundary Commission report became an irrelevance. The President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State W. T. Cosgrave

William Thomas Cosgrave (5 June 1880 – 16 November 1965) was an Irish Fine Gael politician who served as the president of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State from 1922 to 1932, leader of the Opposition in both the Free State and Ir ...

informed the Irish Parliament (the Dail) that the only security for the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland now depended on the goodwill of their neighbours.

The commission's report was not published in full until 1969.

After partition

Both governments agreed to the disbandment of the Council of Ireland. The leaders of the two parts of Ireland did not meet again until 1965. Since partition, Irish republicans and nationalists have sought to end partition, while Ulster loyalists and unionists have sought to maintain it. The pro-Treaty Cumann na nGaedhael government of the Free State hoped the Boundary Commission would make Northern Ireland too small to be viable. It focused on the need to build a strong state and accommodate Northern unionists. The anti-TreatyFianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil (, ; meaning 'Soldiers of Destiny' or 'Warriors of Fál'), officially Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party ( ga, audio=ga-Fianna Fáil.ogg, Fianna Fáil – An Páirtí Poblachtánach), is a conservative and Christian- ...

had Irish unification as one of its core policies and sought to rewrite the Free State's constitution. Sinn Féin rejected the legitimacy of the Free State's institutions altogether because it implied accepting partition. In Northern Ireland, the Nationalist Party was the main political party in opposition to the Unionist governments and partition. Other early anti-partition groups included the National League of the North

The National League of the North (NLN) was an Irish nationalist organisation active in Northern Ireland.

The group was founded in May 1928 on the basis of a radical programme for the "National Unification of Ireland". It was in part an attempt ...

(formed in 1928), the Northern Council for Unity (formed in 1937) and the Irish Anti-Partition League

The Irish Anti-Partition League (APL) was a political organisation based in Northern Ireland which campaigned for a united Ireland from 1945 to 1958.

Foundation

Prior to the establishment of the League, there had been no rank-and-file organis ...

(formed in 1945).

Constitution of Ireland 1937

De Valera came to power in Dublin in 1932, and drafted a newConstitution of Ireland

The Constitution of Ireland ( ga, Bunreacht na hÉireann, ) is the constitution, fundamental law of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It asserts the national sovereignty of the Irish people. The constitution, based on a system of representative democra ...

which in 1937 was adopted by plebiscite in the Irish Free State. Its articles 2 and 3 defined the 'national territory' as: "the whole island of Ireland, its islands and the territorial seas". The state was named 'Ireland' (in English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

) and 'Éire

() is Irish for "Ireland", the name of both an island in the North Atlantic and the sovereign state of the Republic of Ireland which governs 84% of the island's landmass. The latter is distinct from Northern Ireland, which covers the remainde ...

' (in Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

); a United Kingdom Act of 1938 described the state as "Eire". The irredentist

Irredentism is usually understood as a desire that one state annexes a territory of a neighboring state. This desire is motivated by ethnic reasons (because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to the population of the parent sta ...

texts in Articles 2 and 3 were deleted by the Nineteenth Amendment in 1998, as part of the Belfast Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA), or Belfast Agreement ( ga, Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta or ; Ulster-Scots: or ), is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April 1998 that ended most of the violence of The Troubles, a political conflict in No ...

.

British offer of unity in 1940

During theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, after the Fall of France, Britain made a qualified offer of Irish unity in June 1940, without reference to those living in Northern Ireland. On their rejection, neither the London or Dublin governments publicised the matter.

Ireland would have joined the allies against the Axis by allowing British ships to use its ports, arresting Germans and Italians, setting up a joint defence council and allowing overflights.

In return, arms would have been provided to Ireland and British forces would cooperate on a German invasion. London would have declared that it accepted 'the principle of a United Ireland

United Ireland, also referred to as Irish reunification, is the proposition that all of Ireland should be a single sovereign state. At present, the island is divided politically; the sovereign Republic of Ireland has jurisdiction over the maj ...

' in the form of an undertaking 'that the Union is to become at an early date an accomplished fact from which there shall be no turning back.'

Clause ii of the offer promised a joint body to work out the practical and constitutional details, 'the purpose of the work being to establish at as early a date as possible the whole machinery of government of the Union'. The proposals were first published in 1970 in a biography of de Valera.

1945–1973