Paramyxoviridae on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Paramyxoviridae'' (from

The

The

* N – the nucleocapsid protein associates with genomic RNA (one molecule per hexamer) and protects the RNA from nuclease digestion

* P – the phosphoprotein binds to the N and L proteins and forms part of the RNA polymerase complex. P is the polymerase co-factor.

* M – the matrix protein assembles between the envelope and the nucleocapsid core, it organizes and maintains virion structure

* F – the fusion protein projects from the envelope surface as a trimer, and mediates cell entry by inducing fusion between the viral envelope and the cell membrane by class I fusion. One of the defining characteristics of members of the family Paramyxoviridae is the requirement for a neutral pH for fusogenic activity.

* H/HN/G – the cell attachment proteins span the viral envelope and project from the surface as spikes. They bind to proteins on the surface of target cells to facilitate cell entry. Proteins are designated H (

* N – the nucleocapsid protein associates with genomic RNA (one molecule per hexamer) and protects the RNA from nuclease digestion

* P – the phosphoprotein binds to the N and L proteins and forms part of the RNA polymerase complex. P is the polymerase co-factor.

* M – the matrix protein assembles between the envelope and the nucleocapsid core, it organizes and maintains virion structure

* F – the fusion protein projects from the envelope surface as a trimer, and mediates cell entry by inducing fusion between the viral envelope and the cell membrane by class I fusion. One of the defining characteristics of members of the family Paramyxoviridae is the requirement for a neutral pH for fusogenic activity.

* H/HN/G – the cell attachment proteins span the viral envelope and project from the surface as spikes. They bind to proteins on the surface of target cells to facilitate cell entry. Proteins are designated H (

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''para-'' “by the side of” and ''myxa'' “mucus

Mucus ( ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It is ...

”) is a family of negative-strand RNA virus

Negative-strand RNA viruses (−ssRNA viruses) are a group of related viruses that have negative-sense, single-stranded genomes made of ribonucleic acid. They have genomes that act as complementary strands from which messenger RNA (mRNA) is sy ...

es in the order ''Mononegavirales

''Mononegavirales'' is an order of negative-strand RNA viruses which have nonsegmented genomes. Some common members of the order are Ebola virus, human respiratory syncytial virus, measles virus, mumps virus, Nipah virus, and rabies virus. All of ...

''. Vertebrates serve as natural hosts. Diseases associated with this family include measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

, mumps

MUMPS ("Massachusetts General Hospital Utility Multi-Programming System"), or M, is an imperative, high-level programming language with an integrated transaction processing key–value database. It was originally developed at Massachusetts Gener ...

, and respiratory tract infection

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are infectious diseases involving the respiratory tract. An infection of this type usually is further classified as an upper respiratory tract infection (URI or URTI) or a lower respiratory tract infection (LRI ...

s. The family has four subfamilies, 17 genera, and 78 species, three genera of which are unassigned to a subfamily.

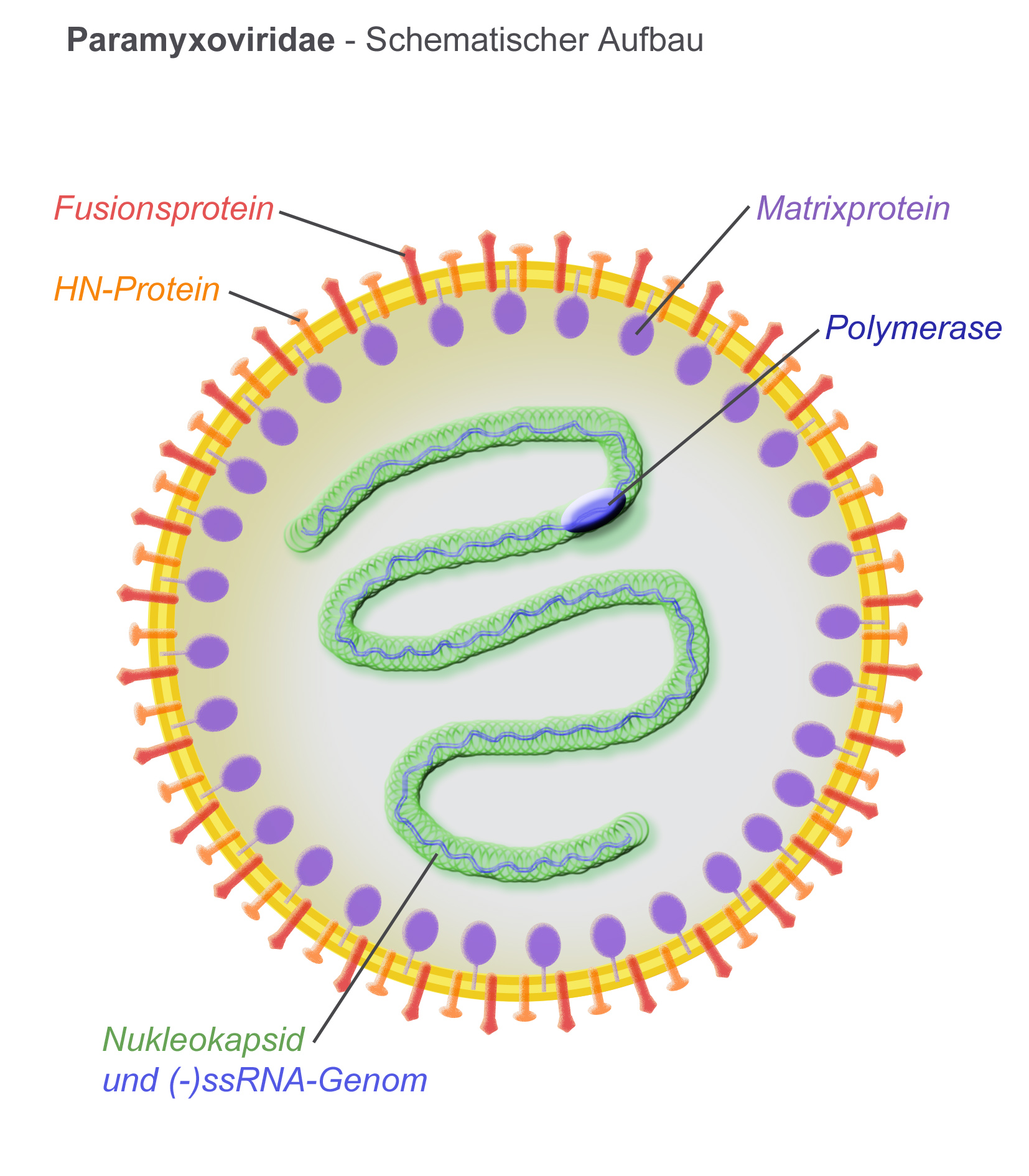

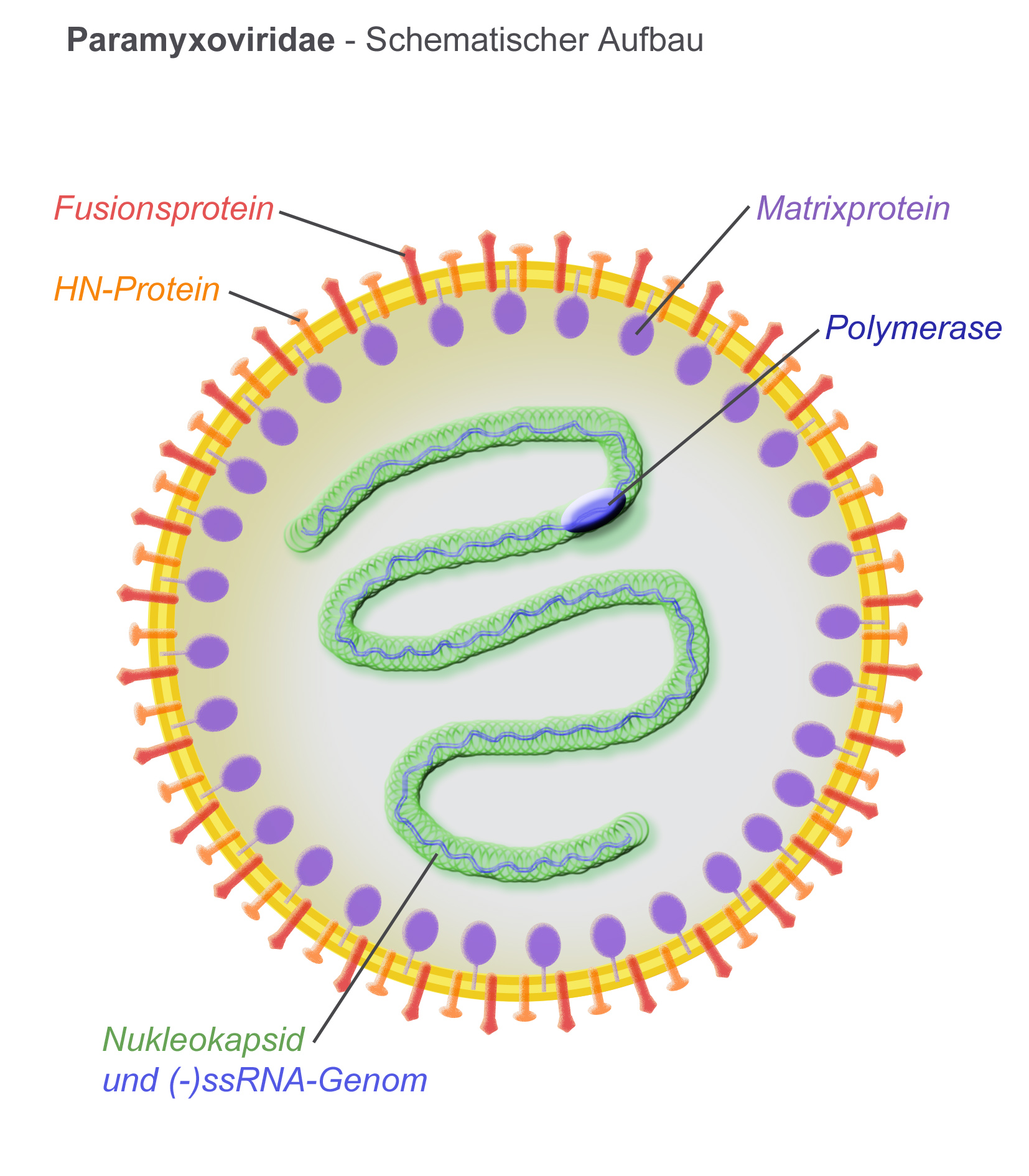

Structure

Virions are enveloped and can be spherical or pleomorphic and capable of producing filamentous virions. The diameter is around 150 nm. Genomes are linear, around 15kb in length. Fusion proteins and attachment proteins appear as spikes on the virion surface. Matrix proteins inside the envelope stabilise virus structure. The nucleocapsid core is composed of the genomic RNA, nucleocapsid proteins, phosphoproteins and polymerase proteins.Genome

The

The genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

is nonsegmented, negative-sense RNA, 15–19 kilobases in length, and contains six to 10 genes. Extracistronic (noncoding) regions include:

* A 3’ leader sequence, 50 nucleotides

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules w ...

in length, which acts as a transcriptional promoter.

* A 5’ trailer sequence, 50–161 nucleotides long

*Intergenomic regions between each gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

, which are three nucleotides long for morbilliviruses, respiroviruses, and henipaviruses, and variable length (one-56 nucleotides) for rubulaviruses.

Each gene contains transcription start/stop signals at the beginning and end, which are transcribed as part of the gene.

Gene sequence within the genome is conserved across the family due to a phenomenon known as transcriptional polarity (see ''Mononegavirales

''Mononegavirales'' is an order of negative-strand RNA viruses which have nonsegmented genomes. Some common members of the order are Ebola virus, human respiratory syncytial virus, measles virus, mumps virus, Nipah virus, and rabies virus. All of ...

'') in which genes closest to the 3’ end of the genome are transcribed in greater abundance than those towards the 5’ end. This is a result of structure of the genome. After each gene is transcribed, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase pauses to release the new mRNA when it encounters an intergenic sequence. When the RNA polymerase is paused, a chance exists that it will dissociate from the RNA genome. If it dissociates, it must re-enter the genome at the leader sequence, rather than continuing to transcribe the length of the genome. The result is that the further downstream genes are from the leader sequence, the less they will be transcribed by RNA polymerase.

Evidence for a single promoter model was verified when viruses were exposed to UV light. UV radiation can cause dimerization of RNA, which prevents transcription by RNA polymerase. If the viral genome follows a multiple promoter model, the level inhibition of transcription should correlate with the length of the RNA gene. However, the genome was best described by a single promoter model. When paramyxovirus genome was exposed to UV light, the level of inhibition of transcription was proportional to the distance from the leader sequence. That is, the further the gene is from the leader sequence, the greater the chance of RNA dimerization inhibiting RNA polymerase.

The virus takes advantage of the single promoter model by having its genes arranged in relative order of protein needed for successful infection. For example, nucleocapsid protein, N, is needed in greater amounts than RNA polymerase, L.

Viruses in the ''Paramyxoviridae'' family are also antigenically stable, meaning that the glycoproteins on the viruses are consistent between different strains of the same type. Two reasons for this phenomenon are posited: The first is that the genome is nonsegmented, thus cannot undergo genetic reassortment. For this process to occur, segments needed as reassortment happen when segments from different strains are mixed together to create a new strain. With no segments, nothing can be mixed with one another, so no antigenic shift

Antigenic shift is the process by which two or more different strains of a virus, or strains of two or more different viruses, combine to form a new subtype having a mixture of the surface antigens of the two or more original strains. The term is ...

occurs. The second reason relates to the idea of antigenic drift

Antigenic drift is a kind of genetic variation in viruses, arising from the accumulation of mutations in the virus genes that code for virus-surface proteins that host antibodies recognize. This results in a new strain of virus particles that is ...

. Since RNA-dependent RNA polymerase does not have an error-checking function, many mutations are made when the RNA is processed. These mutations build up and eventually new strains are created. Due to this concept, one would expect that paramyxoviruses should not be antigenically stable; however, the opposite is seen to be true. The main hypothesis behind why the viruses are antigenically stable is that each protein and amino acid has an important function. Thus, any mutation would lead to a decrease or total loss of function, which would in turn cause the new virus to be less efficient. These viruses would not be able to survive as long compared to the more virulent strains, and so would die out.

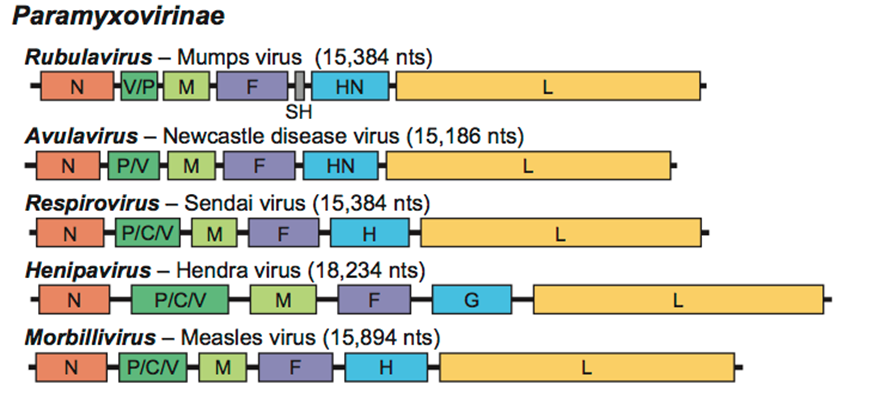

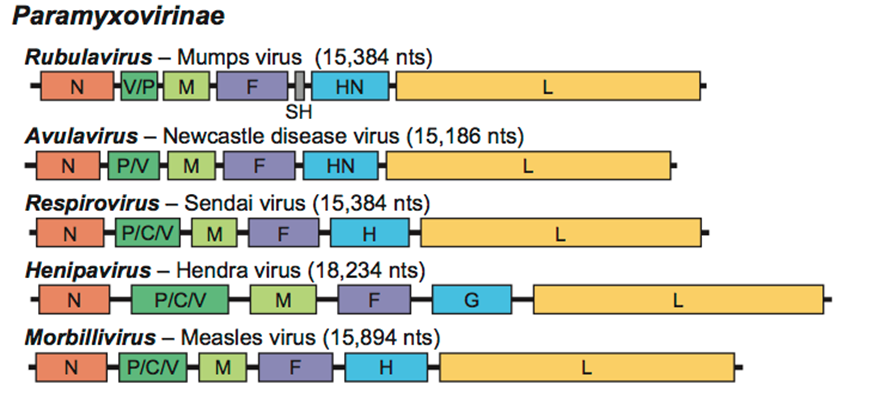

Many paramyxovirus genomes follow the "rule of six". The total length of the genome is almost always a multiple of six. This is probably due to the advantage of having all RNA bound by N protein (since N binds hexamers of RNA). If RNA is left exposed, the virus does not replicate efficiently. The gene sequence is:

*Nucleocapsid – phosphoprotein – matrix – fusion – attachment – large (polymerase)

Proteins

* N – the nucleocapsid protein associates with genomic RNA (one molecule per hexamer) and protects the RNA from nuclease digestion

* P – the phosphoprotein binds to the N and L proteins and forms part of the RNA polymerase complex. P is the polymerase co-factor.

* M – the matrix protein assembles between the envelope and the nucleocapsid core, it organizes and maintains virion structure

* F – the fusion protein projects from the envelope surface as a trimer, and mediates cell entry by inducing fusion between the viral envelope and the cell membrane by class I fusion. One of the defining characteristics of members of the family Paramyxoviridae is the requirement for a neutral pH for fusogenic activity.

* H/HN/G – the cell attachment proteins span the viral envelope and project from the surface as spikes. They bind to proteins on the surface of target cells to facilitate cell entry. Proteins are designated H (

* N – the nucleocapsid protein associates with genomic RNA (one molecule per hexamer) and protects the RNA from nuclease digestion

* P – the phosphoprotein binds to the N and L proteins and forms part of the RNA polymerase complex. P is the polymerase co-factor.

* M – the matrix protein assembles between the envelope and the nucleocapsid core, it organizes and maintains virion structure

* F – the fusion protein projects from the envelope surface as a trimer, and mediates cell entry by inducing fusion between the viral envelope and the cell membrane by class I fusion. One of the defining characteristics of members of the family Paramyxoviridae is the requirement for a neutral pH for fusogenic activity.

* H/HN/G – the cell attachment proteins span the viral envelope and project from the surface as spikes. They bind to proteins on the surface of target cells to facilitate cell entry. Proteins are designated H (hemagglutinin

In molecular biology, hemagglutinins (or ''haemagglutinin'' in British English) (from the Greek , 'blood' + Latin , 'glue') are receptor-binding membrane fusion glycoproteins produced by viruses in the ''Paramyxoviridae'' family. Hemagglutinins ar ...

) for morbilliviruses as they possess haemagglutination activity, observed as an ability to cause red blood cells to clump in laboratory tests. HN (Hemagglutinin-neuraminidase

Hemagglutinin-neuraminidase refers to a single viral protein that has both hemagglutinin and (endo) neuraminidase activity. This is in contrast to the proteins found in influenza, where both functions exist but in two separate proteins. Its neura ...

) attachment proteins occur in respiroviruses, rubulaviruses and avulaviruses. These possess both haemagglutination and neuraminidase

Exo-α-sialidase (EC 3.2.1.18, sialidase, neuraminidase; systematic name acetylneuraminyl hydrolase) is a glycoside hydrolase that cleaves the glycosidic linkages of neuraminic acids:

: Hydrolysis of α-(2→3)-, α-(2→6)-, α-(2→8)- glycos ...

activity, which cleaves sialic acid on the cell surface, preventing viral particles from reattaching to previously infected cells. Attachment proteins with neither haemagglutination nor neuraminidase activity are designated G (glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as glycos ...

). These occur in henipaviruses.

* L – the large protein is the catalytic subunit of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) or RNA replicase is an enzyme that catalyzes the replication of RNA from an RNA template. Specifically, it catalyzes synthesis of the RNA strand complementary to a given RNA template. This is in contrast to t ...

(RDRP)

* Accessory proteins – a mechanism known as RNA editing (see ''Mononegavirales

''Mononegavirales'' is an order of negative-strand RNA viruses which have nonsegmented genomes. Some common members of the order are Ebola virus, human respiratory syncytial virus, measles virus, mumps virus, Nipah virus, and rabies virus. All of ...

'') allows multiple proteins to be produced from the P gene. These are not essential for replication but may aid in survival in vitro or may be involved in regulating the switch from mRNA synthesis to antigenome

{{Short pages monitor