Palm Island Aboriginal Settlement on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Palm Island Aboriginal Settlement, later officially known as Director of Native Affairs Office, Palm Island and also known as Palm Island Aboriginal Reserve, Palm Island mission and Palm Island Dormitory, was an

Palm Island Aboriginal Settlement, later officially known as Director of Native Affairs Office, Palm Island and also known as Palm Island Aboriginal Reserve, Palm Island mission and Palm Island Dormitory, was an

Palm Island was re-gazetted as an Aboriginal reserve on 16 July 1938, and on 20 September 1941 some of the small islands surrounding Great Palm, including

Palm Island was re-gazetted as an Aboriginal reserve on 16 July 1938, and on 20 September 1941 some of the small islands surrounding Great Palm, including

In the first two decades of its establishment the population of Indigenous "inmates" increased from 200 to 1,630. In 1939 there were 1248. By the early 1920s, Palm Island had become the largest of the government Aboriginal settlements. Administrators found its location attractive as Aboriginal people could be isolated, but Palm Island quickly gained a reputation amongst Aboriginal people as a

In the first two decades of its establishment the population of Indigenous "inmates" increased from 200 to 1,630. In 1939 there were 1248. By the early 1920s, Palm Island had become the largest of the government Aboriginal settlements. Administrators found its location attractive as Aboriginal people could be isolated, but Palm Island quickly gained a reputation amongst Aboriginal people as a  On the reserve there was a "hospital, two schools, a Female Welfare Organisation with a Home Training Centre, an Old People's Home, a Child Welfare Centre with baby and child clinics, dormitories for children, women and youths, churches of various denominations, a curio shop, sawmill and logging operations, and a workshop where training was undertaken in carpentry, joining and plumbing".

A bell tower was built to dictate the running of the mission. The bell would ring each morning at eight, a signal for everyone to line up for parade in the mission square. Those who failed to line up had their food allocation cut. At nine each evening the bell would ring again, signalling the shutting down of the island's electricity. The roll call and curfew lasted until the 1970s. The bell tower still stands in the local square to this day, a relic of Palm Island's history. It was recorded that there was almost military-like discipline in the segregation between white and black, and that inmates "were treated as rather dull retarded children".

The following letter was written to a new bride by the "Protector":

On the reserve there was a "hospital, two schools, a Female Welfare Organisation with a Home Training Centre, an Old People's Home, a Child Welfare Centre with baby and child clinics, dormitories for children, women and youths, churches of various denominations, a curio shop, sawmill and logging operations, and a workshop where training was undertaken in carpentry, joining and plumbing".

A bell tower was built to dictate the running of the mission. The bell would ring each morning at eight, a signal for everyone to line up for parade in the mission square. Those who failed to line up had their food allocation cut. At nine each evening the bell would ring again, signalling the shutting down of the island's electricity. The roll call and curfew lasted until the 1970s. The bell tower still stands in the local square to this day, a relic of Palm Island's history. It was recorded that there was almost military-like discipline in the segregation between white and black, and that inmates "were treated as rather dull retarded children".

The following letter was written to a new bride by the "Protector":

AIATSIS Library

* Map:

Palm Island Aboriginal Settlement, later officially known as Director of Native Affairs Office, Palm Island and also known as Palm Island Aboriginal Reserve, Palm Island mission and Palm Island Dormitory, was an

Palm Island Aboriginal Settlement, later officially known as Director of Native Affairs Office, Palm Island and also known as Palm Island Aboriginal Reserve, Palm Island mission and Palm Island Dormitory, was an Aboriginal reserve

An Aboriginal reserve, also called simply reserve, was a government-sanctioned settlement for Aboriginal Australians, created under various state and federal legislation. Along with missions and other institutions, they were used from the 19th c ...

and penal settlement

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer to ...

on Great Palm Island

Great Palm Island, usually known as Palm Island, is the largest island in the Palm Islands group off Northern Queensland, Australia. It is known for its Aboriginal community, the legacy of an Aboriginal reserve, the Palm Island Aboriginal Sett ...

, the main island in the Palm Island group in North Queensland, Australia. It was the largest and most punitive reserve in Queensland.

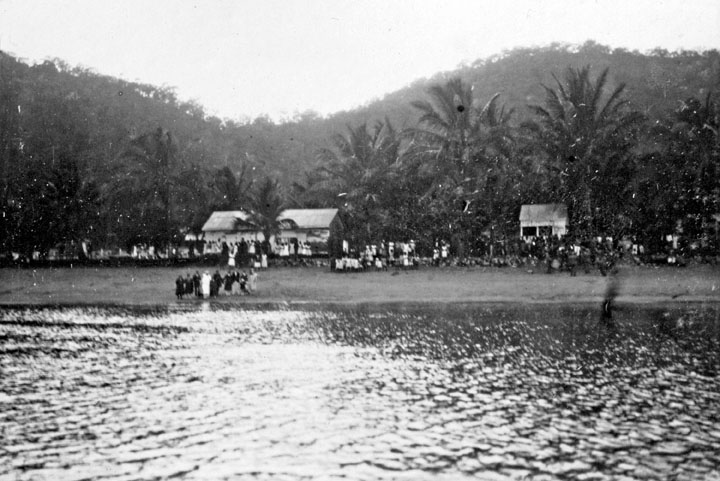

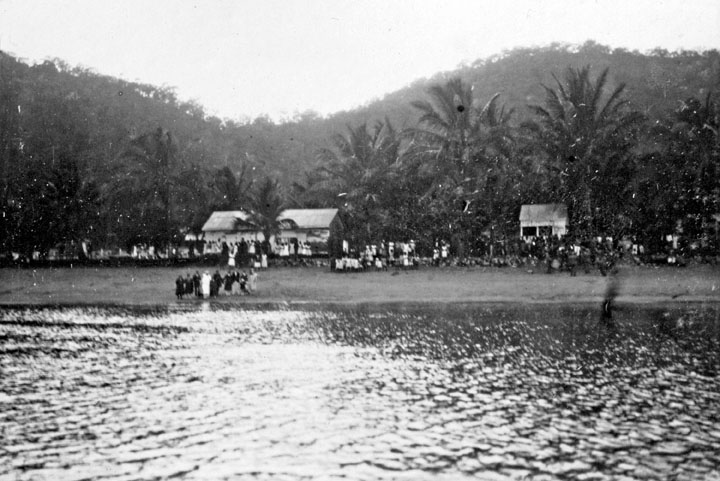

Gazetted in 1914, the first residents were only moved there in March 1918 from the Hull River Aboriginal Settlement after that reserve was destroyed by a cyclone. The settlement continued under government control in various forms until 1975. Palm Island was mentioned in the '' Bringing Them Home Report'' as an institution that housed children removed from their families, part of the Stolen Generation.

Background

In 1909 theChief Protector of Aborigines

The role of Protector of Aborigines was first established in South Australia in 1836.

The role became established in other parts of Australia pursuant to a recommendation contained in the ''Report of the Parliamentary Select Committee on Abori ...

visited the island, apparently to check on the activities of Japanese pearling crews in the area, and reported the existence of a small camp of Aboriginal people. In 1916 he found Palm Island to be "the ideal place for a delightful holiday' and that its remoteness also made it suitable for use as a penitentiary" for "individuals we desire to punish".

1914/1918: Establishment

In 1914 the Government established the Hull River Aboriginal Settlement on the Hull River near Mission Beach on the Australian mainland. On 10 March 1918, the structures were destroyed by a cyclone and were never rebuilt. Palm Island Aboriginal Settlement had been gazetted as anAboriginal reserve

An Aboriginal reserve, also called simply reserve, was a government-sanctioned settlement for Aboriginal Australians, created under various state and federal legislation. Along with missions and other institutions, they were used from the 19th c ...

on 20 June 1914, although at the time there were few Aboriginal people living on Great Palm. Its size was about . After the cyclone had demolished Hull River, around 1 April 1918 the settlement relocated to Palm Island, with the new population from various Aboriginal peoples – from at least 57 different language groups throughout Queensland – later referred to as the Bwgcolman

The Bwgcolman (pronounced "Bwookamun") is the self-assigned name for the Aboriginal Australians who were deported from many areas of the Queensland mainland, and confined in resettlement on Great Palm Island after the establishment of an Aborigin ...

people.

The Superintendent of Palm Island Aboriginal Settlement was directly responsible to the Chief Protector of Aboriginals, who in turn was responsible to the Home Secretary's Office (after 5 December 1935, the Department of Health and Home Affairs). The Aboriginal residents were deemed wards of the state

In law, a ward is a minor or incapacitated adult placed under the protection of a legal guardian or government entity, such as a court. Such a person may be referenced as a "ward of the court".

Overview

The wardship jurisdiction is an ancient j ...

, with every aspect of their lives controlled by this office.

1920s–1930s: Missionaries, school and dormitories

A number of missionaries from various Christian denominations visited or settled and worked on the island. In the 1920s, two femaleBaptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

missionaries began some work on the reserve, and Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

priests visited between 1918 and 1924. In 1930, Father Paddy Molony began his work, and the Sisters of Our Lady Help of Christians occupied the convent

A convent is a community of monks, nuns, religious brothers or, sisters or priests. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community. The word is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglic ...

built in 1934. A Catholic school was built in 1937.

In March 1921 Great Palm Island and Eclipse Island were gazetted as Aboriginal Reserves.

In 1922–3 an Industrial School (under the ''Industrial and Reformatory Schools Act 1865'') and segregated dormitories for the children were established. On arrival, children were separated from their parents and then segregated by sex. The dormitories operated as care for orphan

An orphan (from the el, ορφανός, orphanós) is a child whose parents have died.

In common usage, only a child who has lost both parents due to death is called an orphan. When referring to animals, only the mother's condition is usuall ...

s or neglected children, but also places of detention for single mothers and their children.

1930: Superintendent murders

On 3 February 1930, in an incident known as the1930 Palm Island Tragedy

The Palm Island Tragedy occurred in 1930 on Palm Island Aboriginal reserve, Aboriginal settlement on Great Palm Island in Queensland, Australia, when the settlement's Superintendent, Robert Henry Curry, shot and wounded two people, and set fire ...

, the first Superintendent of the Settlement, Robert Henry Curry, who had been a strict disciplinarian, shot and wounded two people, and set fire to several buildings, killing his two children. Later in the day, the Superintendent was shot dead. An official inquiry by the Queensland Attorney General followed. Those involved in the shooting of the Superintendent, including the Deputy Superintendent and the Palm Island Medical Officer, were charged with murder. During the trial the Crown Prosecutor was directed by the trial judge to drop the charges, stating that the shooting was justified.

1938/1941: Re-gazetting

Palm Island was re-gazetted as an Aboriginal reserve on 16 July 1938, and on 20 September 1941 some of the small islands surrounding Great Palm, including

Palm Island was re-gazetted as an Aboriginal reserve on 16 July 1938, and on 20 September 1941 some of the small islands surrounding Great Palm, including Curacoa Island

Curacoa Island (pron. KEWR-ə-sow) is one of the islands in the Palm Islands group off the coast of Queensland, Australia. The nearest island is Great Palm Island, after which the group is named. Curacoa Island is uninhabited.

The Aborigina ...

, Falcon Island, Esk Island, Brisk Island, and Havannah Island, were also gazetted as reserves, under Chief Protector John William Bleakley

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

, who targeted them as sites for further institutions for punishing people. There is no record of dwellings or other structures being built on these islands, but Eclipse Island had become known as "Punishment Island" under Curry. Curry, as punishment for misdemeanours such as speaking their own language or gambling, was to exile men to Eclipse Island, and sometimes Curacoa, with only bread and water, sometimes for weeks at a time.

South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

n anthropologist Norman Tindale

Norman Barnett Tindale AO (12 October 1900 – 19 November 1993) was an Australian anthropologist, archaeologist, entomologist and ethnologist.

Life

Tindale was born in Perth, Western Australia in 1900. His family moved to Tokyo and lived ther ...

visited the island in 1938, and recorded the genealogies

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kins ...

of people representing a large number of tribal groups from across mainland Queensland.

1939: Director of Native Affairs Office, Palm Island

After 12 Oct 1939, when the ''Aboriginals Preservation and Protection Act 1939

Aborigine, aborigine or aboriginal may refer to:

*Aborigines (mythology), in Roman mythology

* Indigenous peoples, general term for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area

*One of several groups of indigenous peoples, see ...

'' and ''Torres Strait Islander Act 1939 Torres may refer to:

People

*Torres (surname), a Spanish and Portuguese surname

*Torres (musician), singer-songwriter Mackenzie Scott

** ''Torres'' (album), 2013 self-titled album by Torres

Places Americas

* Torres, Colorado, an unincorporated c ...

'' were passed, the name changed from Palm Island Aboriginal Settlement to Director of Native Affairs Office, Palm Island. The Act effected a change in policy: instead of protection and segregation of Indigenous people, it instead focussed on assimilation into the "white community". It gave freedom and full citizenship rights to Aboriginal who qualified for these, but also streamlined the administration and development of Aboriginal reserves.

On a surprise inspection of the Palm Island Prison during an official visit in the late 1960s, Senator Jim Keeffe and academic Henry Reynolds discovered two 12- to 13‑year‑old schoolgirls incarcerated in the settlement's prison by the senior administrator on the island (the superintendent

Superintendent may refer to:

*Superintendent (police), Superintendent of Police (SP), or Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP), a police rank

*Prison warden or Superintendent, a prison administrator

*Superintendent (ecclesiastical), a church exec ...

), because "they swore at the teacher".

Life on the reserve

In the first two decades of its establishment the population of Indigenous "inmates" increased from 200 to 1,630. In 1939 there were 1248. By the early 1920s, Palm Island had become the largest of the government Aboriginal settlements. Administrators found its location attractive as Aboriginal people could be isolated, but Palm Island quickly gained a reputation amongst Aboriginal people as a

In the first two decades of its establishment the population of Indigenous "inmates" increased from 200 to 1,630. In 1939 there were 1248. By the early 1920s, Palm Island had become the largest of the government Aboriginal settlements. Administrators found its location attractive as Aboriginal people could be isolated, but Palm Island quickly gained a reputation amongst Aboriginal people as a penal settlement

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer to ...

. They were removed from across Queensland as punishment; being "disruptive", falling pregnant to a white man, or being born with " mixed blood" were among the "infringements" that could lead to the penalty of being sent to Palm Island. New arrivals came after being sentenced by a court or released from prison, or they were sent by administrators of other missions wishing to weed out their more ill-mannered or disruptive Aboriginal people.pages 49–50 The death rate on the reserve was higher than the birth rate until after 1945, with replenishment of numbers from the mainland the only reason for the growth in population there.

Palm Island was used as a penal institution for Indigenous people who ran afoul of the 1897 Protection Act, as well as those who had committed criminal offence

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Ca ...

s. Many men who had already served their time in jail on the mainland were afterwards moved to the reserve, thus punishing them a second time for the same offence.

In the 1930s a local doctor highlighted malnutrition

Malnutrition occurs when an organism gets too few or too many nutrients, resulting in health problems. Specifically, it is "a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients" which adversely affects the body's tissues ...

on the island, and demanded that the Government triple rations for the islanders and that children be provided with fruit juice, but the request was denied.

On the reserve there was a "hospital, two schools, a Female Welfare Organisation with a Home Training Centre, an Old People's Home, a Child Welfare Centre with baby and child clinics, dormitories for children, women and youths, churches of various denominations, a curio shop, sawmill and logging operations, and a workshop where training was undertaken in carpentry, joining and plumbing".

A bell tower was built to dictate the running of the mission. The bell would ring each morning at eight, a signal for everyone to line up for parade in the mission square. Those who failed to line up had their food allocation cut. At nine each evening the bell would ring again, signalling the shutting down of the island's electricity. The roll call and curfew lasted until the 1970s. The bell tower still stands in the local square to this day, a relic of Palm Island's history. It was recorded that there was almost military-like discipline in the segregation between white and black, and that inmates "were treated as rather dull retarded children".

The following letter was written to a new bride by the "Protector":

On the reserve there was a "hospital, two schools, a Female Welfare Organisation with a Home Training Centre, an Old People's Home, a Child Welfare Centre with baby and child clinics, dormitories for children, women and youths, churches of various denominations, a curio shop, sawmill and logging operations, and a workshop where training was undertaken in carpentry, joining and plumbing".

A bell tower was built to dictate the running of the mission. The bell would ring each morning at eight, a signal for everyone to line up for parade in the mission square. Those who failed to line up had their food allocation cut. At nine each evening the bell would ring again, signalling the shutting down of the island's electricity. The roll call and curfew lasted until the 1970s. The bell tower still stands in the local square to this day, a relic of Palm Island's history. It was recorded that there was almost military-like discipline in the segregation between white and black, and that inmates "were treated as rather dull retarded children".

The following letter was written to a new bride by the "Protector":"Dear Lucy, Your letter gave me quite a shock, fancy you wanting to draw four pounds to buy a brooch, ring, bangle, work basket, tea set, etc, etc. I am quite sure Mrs. Henry would expend the money carefully for you, but I must tell you that no Aborigine can draw 4/5 of their wages unless they are sick and in hospital and require the money to buy comforts... However, as it is Christmas I will let you have 1/5 – out of your banking account to buy lollies with."Aboriginal people were forbidden to speak their language and to go into "white" zones. Everyday activity was highly controlled by administrators, and there were nightly curfews and the vetting of mail. In some cases, women were put into dormitories and their husbands sent to work on the mainland.

1957: Strike

One of the harshest Superintendents was Roy Bartlam, who arrested workers for being a minute behind the roll call in the reserve. All Islanders were required to work 30 hours each week, and up until the 1960s no wages were paid for this work. The catalyst for the strike was the attempted deportation of Indigenous inmate Albie Geia who committed the offence of disobeying the European overseer. The strike was also against the harsh conditions imposed by Bartlam, low or no wages, as well as poor housing and rations. Bartlam was forced to flee to his office and call for reinforcements. Armed Police arrived by RAAF launch from Townsville, and the "ringleaders" and their families were deported in chains to other Aboriginal settlements. Seven families were banished from the Palm Island in 1957 for taking part in astrike

Strike may refer to:

People

* Strike (surname)

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

*Airstrike, military strike by air forces on either a suspected ...

organised to protest against the Dickensian

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

working conditions imposed by the Queensland Government under the reserve system. Athlete Cathy Freeman

Catherine Astrid Salome Freeman (born 16 February 1973) is an Aboriginal Australian former sprinter, who specialised in the 400 metres event. Her personal best of 48.63 seconds currently ranks her as the ninth-fastest woman of all time, set ...

's mother, Cecilia Barber, and the family of strike ringleader Frederick William Doolan including Billy Doolan

Frederick William Doolan Jnr (born 1952

Smh.com.au ...

Jnr. were among those banished from the island.

Smh.com.au ...

1960s–1975

New dormitories for boys and girls were constructed in 1962 and 1965 respectively. By 1966, there were about 71 children housed in them. The Director of Native Affairs Office was superseded by the Aboriginal and Island Affairs Department on 28 April 1966, after being abolished by the ''Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Affairs Act 1965

Aborigine, aborigine or aboriginal may refer to:

*Aborigines (mythology), in Roman mythology

* Indigenous peoples, general term for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area

*One of several groups of indigenous peoples, see ...

''. The functions were transferred to the Aboriginal and Island Affairs Department, District Office, Palm Island.

The women's dormitory closed in 1967 and demolished two years later.

In this period, most of the children were being sent by the Children's Services Department. As ideas about the care of young people changed, fewer children were sent to Palm Island, and by 1975 there were only 27 children left in the dormitories. They were closed completely on 5 December 1975.

Legacy

Descendants

Today's population are descendants of people taken to the reserve from 1914 up to 1971. Estimates vary, but the number of tribal groups represented by the descendants (known as theBwgcolman

The Bwgcolman (pronounced "Bwookamun") is the self-assigned name for the Aboriginal Australians who were deported from many areas of the Queensland mainland, and confined in resettlement on Great Palm Island after the establishment of an Aborigin ...

people is at least 43 and has been said to represent 57 different language groups

A language family is a group of languages related through descent from a common ''ancestral language'' or ''parental language'', called the proto-language of that family. The term "family" reflects the tree model of language origination in hist ...

. At least 5000 people were forcibly removed to the reserve from all over Queensland, the Torres Strait

The Torres Strait (), also known as Zenadh Kes, is a strait between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. It is wide at its narrowest extent. To the south is Cape York Peninsula, the northernmost extremity of the Australian mai ...

and Melanesian islands. The majority of the current population descend from peoples occupying the region between Bowen and Tully, from north-western Queensland, and from the Cape York Peninsula

Cape York Peninsula is a large peninsula located in Far North Queensland, Australia. It is the largest unspoiled wilderness in northern Australia.Mittermeier, R.E. et al. (2002). Wilderness: Earth’s last wild places. Mexico City: Agrupació ...

.

Social issues

The "largest and historically most punitive of Queensland's Aboriginal reserves", Palm Island was mentioned in the '' Bringing Them Home Report'' (1997) as an institution that housed children removed from their families, part of the Stolen Generation. Its history has been a major factor in the many social and economic problems which have beset the island since: in 2006 it was reported that the community suffered from chronic alcohol, drug anddomestic abuse

Domestic violence (also known as domestic abuse or family violence) is violence or other abuse that occurs in a domestic setting, such as in a marriage or cohabitation. ''Domestic violence'' is often used as a synonym for '' intimate partne ...

, high unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the refere ...

and an average life expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of its birth, current age, and other demographic factors like sex. The most commonly used measure is life expectancy at birth ...

of 50 years, 30 less than the Australian average. Economist Helen Hughes wrote in 2007 that the state of affairs was largely due to the establishment of the "penal settlement in 1918 for Aborigines unwilling to be docile, underpaid bush and domestic workers", and historical and current "apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

-like" policies: the Queensland Government was failing the community by "stalling the Commonwealth's efforts to improve policing, education and health and to introduce private property rights".

References

Sources

* * (Available aAIATSIS Library

* Map:

Palm Island Select Committee (PISC) reports

* * *Further reading

* {{coord missing, Queensland Aboriginal communities in Queensland Australian Aboriginal missions Far North Queensland 1914 establishments in Australia 1918 establishments in Australia Stolen Generations institutions