The Government of Vichy France was the

collaborationist

Wartime collaboration is cooperation with the enemy against one's country of citizenship in wartime, and in the words of historian Gerhard Hirschfeld, "is as old as war and the occupation of foreign territory".

The term ''collaborator'' dates to t ...

ruling

regime

In politics, a regime (also "régime") is the form of government or the set of rules, cultural or social norms, etc. that regulate the operation of a government or institution and its interactions with society. According to Yale professor Juan Jo ...

or

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

in Nazi-occupied France during the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Of contested

legitimacy

Legitimacy, from the Latin ''legitimare'' meaning "to make lawful", may refer to:

* Legitimacy (criminal law)

* Legitimacy (family law)

* Legitimacy (political)

See also

* Bastard (law of England and Wales)

* Illegitimacy in fiction

* Legit (d ...

, it was headquartered in the town of

Vichy

Vichy (, ; ; oc, Vichèi, link=no, ) is a city in the Allier Departments of France, department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of central France, in the historic province of Bourbonnais.

It is a Spa town, spa and resort town and in World ...

in

occupied France

The Military Administration in France (german: Militärverwaltung in Frankreich; french: Occupation de la France par l'Allemagne) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zo ...

, but it initially

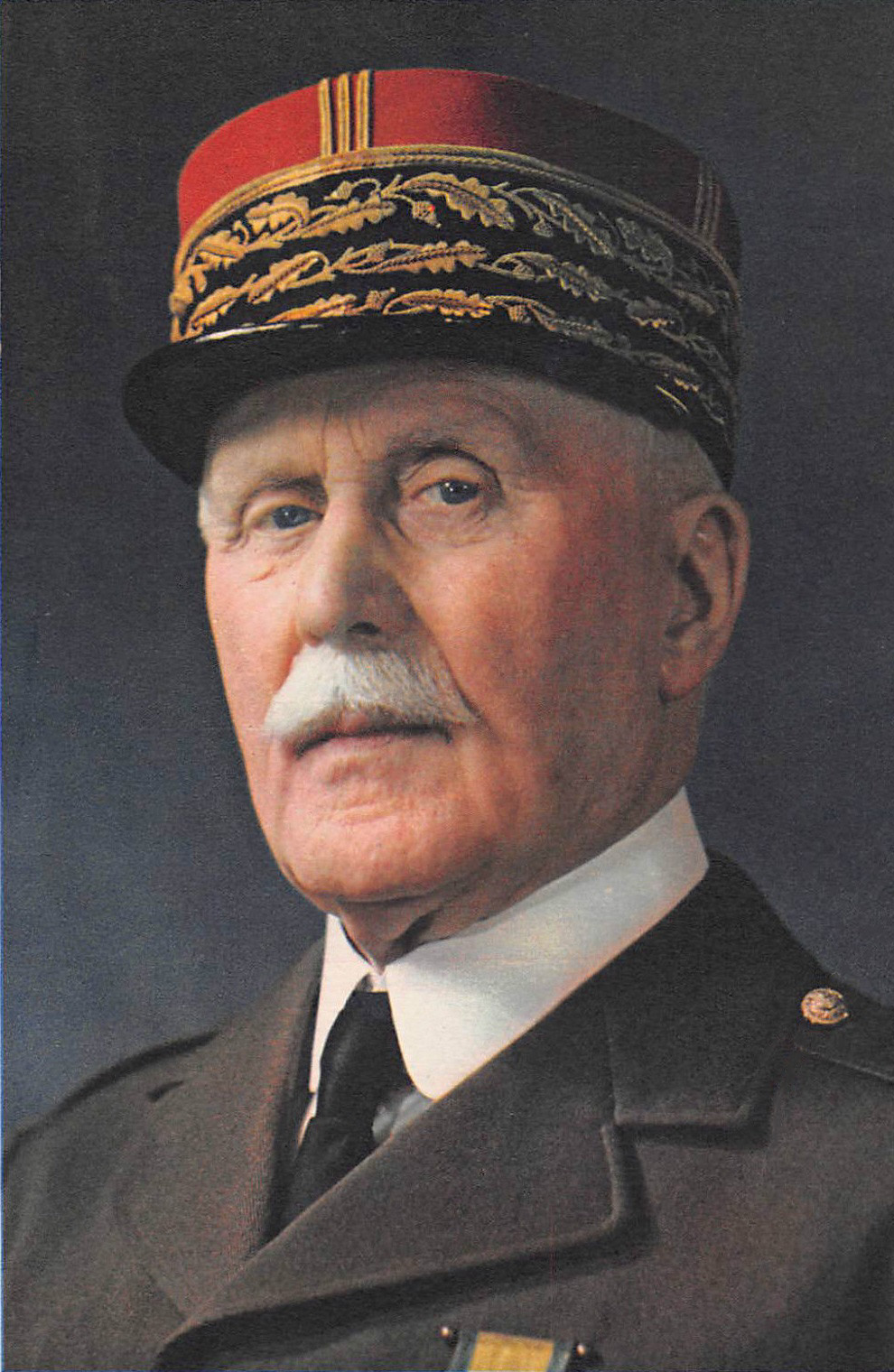

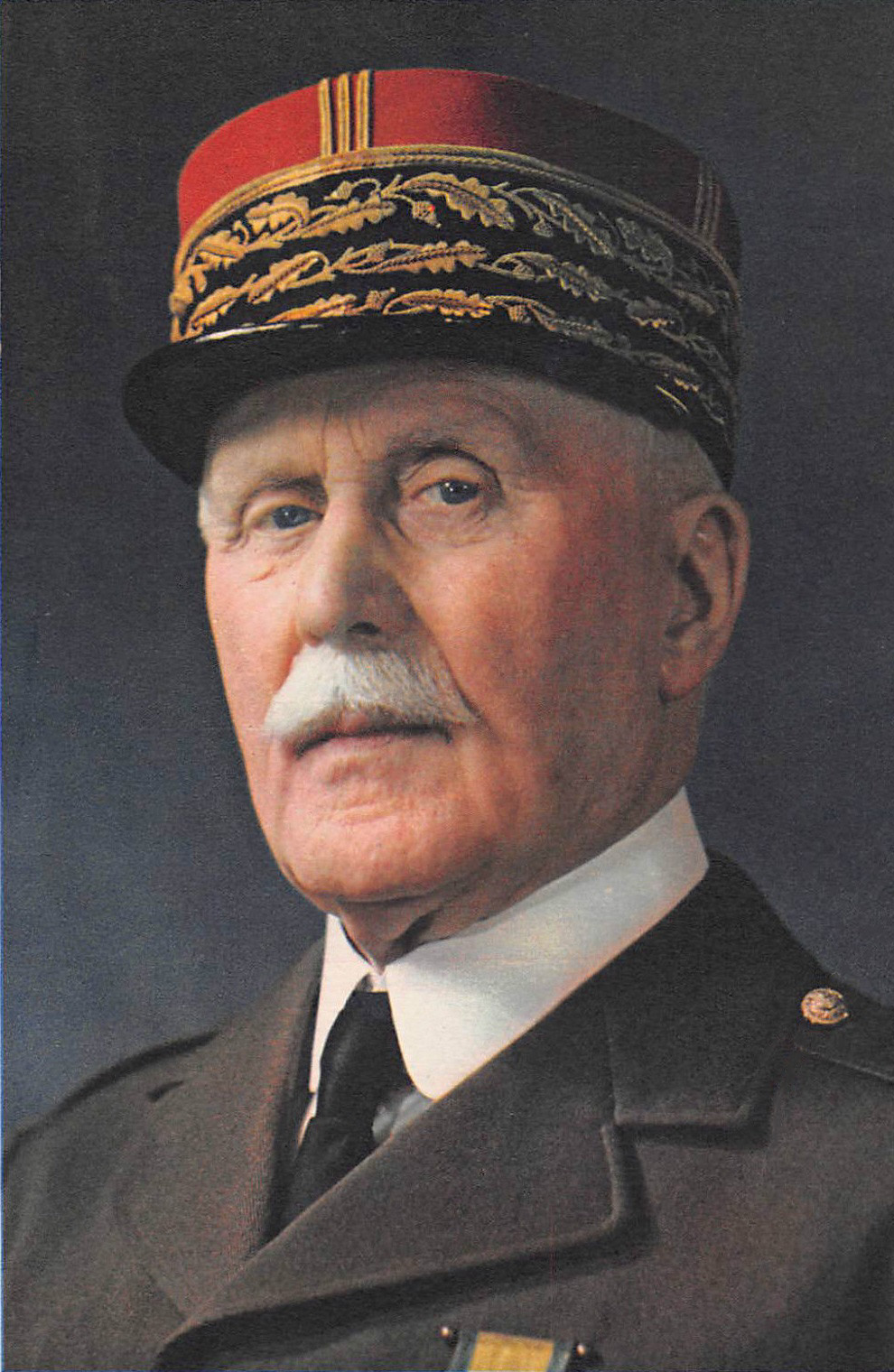

took shape in Paris under Maréchal

Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of World ...

as the successor to the

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

in June 1940. Pétain spent four years in Vichy and after the

Allied invasion of France

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

, fled into exile to Germany in September 1944 with the rest of the French cabinet. It operated as a

government-in-exile

A government in exile (abbreviated as GiE) is a political group that claims to be a country or semi-sovereign state's legitimate government, but is unable to exercise legal power and instead resides in a foreign country. Governments in exile u ...

until April 1945, when the

Sigmaringen enclave

The Sigmaringen enclave was the exiled remnant of France's Nazi-sympathizing Vichy government which fled to Germany during the Liberation of France near the end of World War II in order to avoid capture by the advancing Allied forces. ...

was taken by

Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

forces. Pétain was brought back to France, by then under control of the

Provisional French Republic, and put on trial for

treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

.

Background

A hero of World War I,

known for applying the lessons of the

Second Battle of Champagne

The Second Battle of Champagne ( or Autumn Battle) in World War I was a French offensive against the German army at Champagne that coincided with an Anglo-French assault at north-east Artois and ended with French retreat.

Battle

On 25 Septem ...

to minimize casualties in the

Battle of Verdun

The Battle of Verdun (french: Bataille de Verdun ; german: Schlacht um Verdun ) was fought from 21 February to 18 December 1916 on the Western Front in France. The battle was the longest of the First World War and took place on the hills north ...

, Pétain became commander of French forces in 1917.

He came to power in World War II as a reaction to the stunning

defeat of France in early 1940. Pétain blamed a lack of men and material for the defeat, but had himself participated in the egregious miscalculations that led to the

Maginot Line

The Maginot Line (french: Ligne Maginot, ), named after the French Minister of War André Maginot, is a line of concrete fortifications, obstacles and weapon installations built by France in the 1930s to deter invasion by Germany and force the ...

, and the belief that the

Ardennes

The Ardennes (french: Ardenne ; nl, Ardennen ; german: Ardennen; wa, Årdene ; lb, Ardennen ), also known as the Ardennes Forest or Forest of Ardennes, is a region of extensive forests, rough terrain, rolling hills and ridges primarily in Be ...

were

impenetrable. Nonetheless, Pétain's cautious and defensive tactics at Verdun had won him acclaim from a devastated military, and poet

Paul Valéry

Ambroise Paul Toussaint Jules Valéry (; 30 October 1871 – 20 July 1945) was a French poet, essayist, and philosopher. In addition to his poetry and fiction (drama and dialogues), his interests included aphorisms on art, history, letters, mus ...

called him "the champion of France".

He became Vice-Premier under

Paul Reynaud

Paul Reynaud (; 15 October 1878 – 21 September 1966) was a French politician and lawyer prominent in the interwar period, noted for his stances on economic liberalism and militant opposition to Germany.

Reynaud opposed the Munich Agreement of ...

in May 1940, when the only question was whether the French Army should surrender or the French government sue for an

armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

.

After President

Albert Lebrun

Albert François Lebrun (; 29 August 1871 – 6 March 1950) was a French politician, President of France from 1932 to 1940. He was the last president of the Third Republic. He was a member of the centre-right Democratic Republican Alliance (AR ...

appointed Pétain prime minister on 16 June, the government signed an

armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

with Germany on

22 June 1940.

With France fallen to the Germans, the British judged the risk was too high of the

French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

falling into German hands, and a few days later, in the

attack on Mers-el-Kébir

The Attack on Mers-el-Kébir (Battle of Mers-el-Kébir) on 3 July 1940, during the Second World War, was a British naval attack on neutral French Navy ships at the naval base at Mers El Kébir, near Oran, on the coast of French Algeria. The atta ...

on 3 July 1940, they sank one battleship and damaged five others, also killing 1,297 French servicemen. Pétain severed diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom on 8 July. The next day the

National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repre ...

voted to revise the constitution, and the following day, 10 July, the

National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repre ...

granted absolute power to Pétain, thus ending the

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

. In retaliation for the attack at

Mers el Kébir

Mers El Kébir ( ar, المرسى الكبير, translit=al-Marsā al-Kabīr, lit=The Great Harbor ) is a port on the Mediterranean Sea, near Oran in Oran Province, northwest Algeria. It is famous for the attack on the French fleet in 1940, in t ...

, French aircraft raided

Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

on 18 July but did little damage.

Pétain established an

authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

government at Vichy, with

central planning

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, part ...

a key feature, as well as tight government control. French conventional wisdom, particularly in the administration of

François Mitterrand

François Marie Adrien Maurice Mitterrand (26 October 19168 January 1996) was President of France, serving under that position from 1981 to 1995, the longest time in office in the history of France. As First Secretary of the Socialist Party, he ...

, long held that the French government under Petain had merely sought to make the best of a bad situation. While Vichy policy towards the Germans was at least in part founded in concern for the 1.8 million French prisoners of war, as President

Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to 1988, as well as Ma ...

subsequently acknowledged, even

Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

stood up to Hitler and in so doing saved the lives of thousands of Jews, many of them French.

Antisemitism in France

Antisemitism in France is the expression through words or actions of an ideology of hatred of Jews on French soil.

Jews were present in Roman Gaul, but information is sketchy before the fourth century. As the Roman Empire became Christianiz ...

did not begin under Pétain, but it certainly became a key characteristic of his time in power as manifested in

Vichy anti-Jewish legislation

Anti-Jewish laws were enacted by the Vichy France government in 1940 and 1941 affecting metropolitan France and its overseas territories during World War II. These laws were, in fact, decrees of head of state Marshal Philippe Pétain, since Parli ...

.

Third Republic

Until the invasion, the

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

had been the government of France since the defeat of

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

and the end of the

Franco-Prussian War in 1870. It was dissolved by the

French Constitutional Law of 1940

The French Constitutional Law of 1940 is a set of bills that were voted into law on 10 July 1940 by the National Assembly, which comprised both the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies during the French Third Republic. The law established the regi ...

which gave Pétain the power to write a new constitution. He interpreted this to mean that the previous constitution, outlined in the

French Constitutional Laws of 1875

The Constitutional Laws of 1875 were the laws passed in France by the National Assembly between February and July 1875 which established the Third French Republic.

The constitution laws could be roughly divided into three laws:

* The Act of 24 ...

, no longer constrained him.

In the wake of the

Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

that culminated in the disaster at

Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.[Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectur ...]

on 10 June 1940 in order to avoid capture. On 22 June, France and Germany signed the

Second Armistice at Compiègne

The Armistice of 22 June 1940 was signed at 18:36 near Compiègne, France, by officials of Nazi Germany and the Third French Republic. It did not come into effect until after midnight on 25 June.

Signatories for Germany included Wilhelm Keitel, ...

. The Vichy government led by Pétain replaced the Third Republic. It administered the

zone libre

The ''zone libre'' (, ''free zone'') was a partition of the French metropolitan territory during World War II, established at the Second Armistice at Compiègne on 22 June 1940. It lay to the south of the demarcation line and was administered by ...

in the south of France until November 1942, when Germans and Italians occupied the zone under

Case Anton

Case Anton (german: link=no, Fall Anton) was the military occupation of France carried out by Germany and Italy in November 1942. It marked the end of the Vichy regime as a nominally-independent state and the disbanding of its army (the severel ...

following the Allied landings in

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

under

Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

. Germany occupied northern France and the Atlantic coast, and the Italians, a small territory in the southeast.

Transition to the French State

At the time of the armistice the French and the Germans both thought Britain would come to terms any day, so it included only temporary arrangements. France agreed to its soldiers remaining prisoners of war until hostilities ceased. The terms of the armistice sketch out a "French State" (État français), whose sovereignty and authority in practice were limited to the

zone libre

The ''zone libre'' (, ''free zone'') was a partition of the French metropolitan territory during World War II, established at the Second Armistice at Compiègne on 22 June 1940. It lay to the south of the demarcation line and was administered by ...

, although in theory it administered all of France. The

military administration of the occupied zone was in fact a Nazi dictatorship. However, the fiction of French independence was so important to Laval in particular that he agreed to requisition French workers for Germany to prevent the Germans from doing it unilaterally for the

zone occupée

The Military Administration in France (german: Militärverwaltung in Frankreich; french: Occupation de la France par l'Allemagne) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zo ...

alone.

The Vichy régime considered itself the legitimate government of France, but

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

, who had escaped to England, declared a

government in exile

A government in exile (abbreviated as GiE) is a political group that claims to be a country or semi-sovereign state's legitimate government, but is unable to exercise legal power and instead resides in a foreign country. Governments in exile us ...

in London, and broadcast

appeals

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and ...

to French citizens to resist the occupying forces. Britain shortly thereafter recognized his

Empire Defence Council

The Empire Defense Council (also called Council of Defense of the Empire, from french: Conseil de défense de l'Empire) was the embodiment of Free France which constituted the government from 1940 to 1941. Subsequently, this role was assumed b ...

as the legitimate French government. Under the terms of the armistice France was allowed a small army to defend itself and to administer its colonies. Most of these colonies simply recognized the shift in power, but their allegiance to Vichy shifted once the Allies invaded

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

in

Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

. Britain however outraged the French by

bombing their fleet because the British were unwilling to risk it falling into

Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

*Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinate ...

hands.

Alsace-Lorraine, which France and Germany had long disputed, was simply annexed. When Allied forces landed in North Africa under

Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

, the Nazis annexed the free zone in

Case Anton

Case Anton (german: link=no, Fall Anton) was the military occupation of France carried out by Germany and Italy in November 1942. It marked the end of the Vichy regime as a nominally-independent state and the disbanding of its army (the severel ...

, Germany's response.

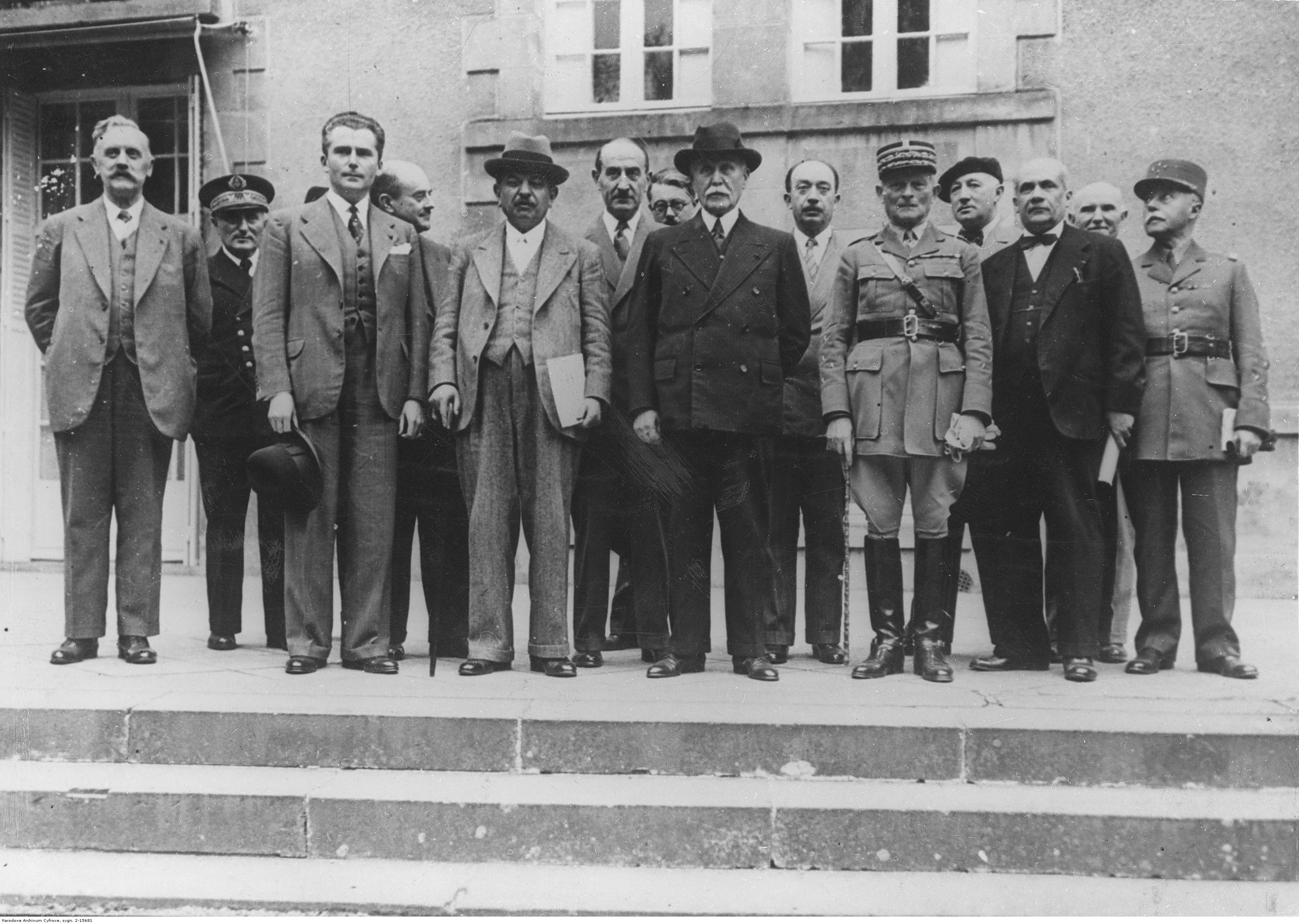

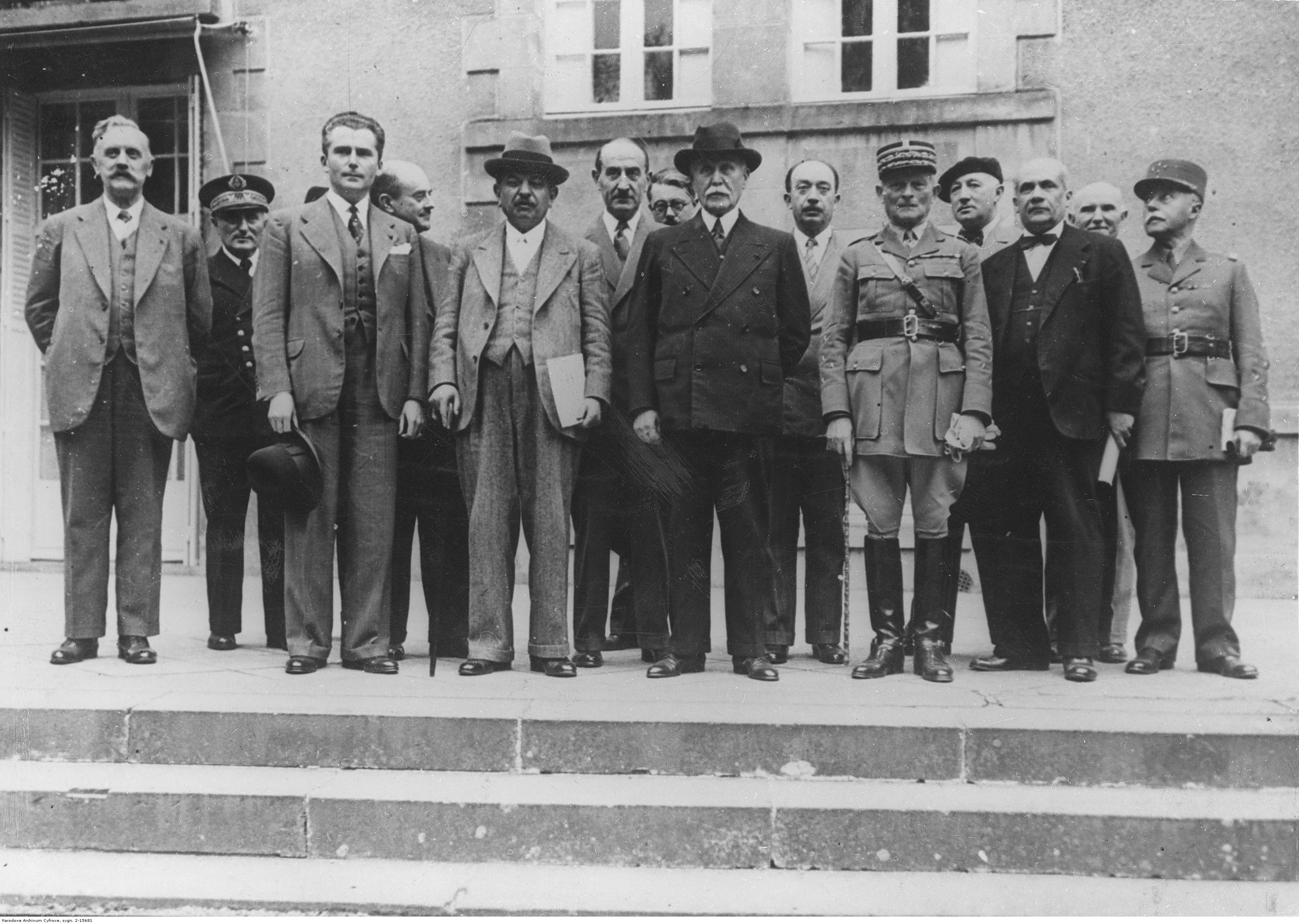

Pétain administration under Third Republic

The Philippe Pétain administration was the last administration of the French Third Republic, succeeding on 16 June 1940 to Paul Reynaud's cabinet. It formed in the middle of the

Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

debacle, when

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

invaded France at the beginning of the Second World War. It was led until 10 July 1940 by

Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of World ...

, and favored the armistice, unlike General

de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

, who favored fighting on in the

Empire Defense Council

The Empire Defense Council (also called Council of Defense of the Empire, from french: Conseil de défense de l'Empire) was the embodiment of Free France which constituted the government from 1940 to 1941. Subsequently, this role was assumed b ...

It was followed by the fifth administration of

Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occu ...

, the first administration of the

Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

regime.

Formation

Paul Reynaud

Paul Reynaud (; 15 October 1878 – 21 September 1966) was a French politician and lawyer prominent in the interwar period, noted for his stances on economic liberalism and militant opposition to Germany.

Reynaud opposed the Munich Agreement of ...

, who had been the French

President of the Council since 22 March 1940, resigned early on the evening of 16 June, and President

Albert Lebrun

Albert François Lebrun (; 29 August 1871 – 6 March 1950) was a French politician, President of France from 1932 to 1940. He was the last president of the Third Republic. He was a member of the centre-right Democratic Republican Alliance (AR ...

called for Pétain to form a new government.

Pétain recruited

Adrien Marquet

Adrien Marquet (6 October 1884 – 3 February 1955) was a socialist mayor of Bordeaux who turned to the far right.

Career

Marquet was born in Bordeaux and became its socialist mayor in 1925. In 1933, he was expelled from the French Section of ...

for Interior and

Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occu ...

for Justice. Laval wanted an offer of Justice. On the advice of

François Charles-Roux

François Charles-Roux (19 November 1879 – 26 June 1961) was a French businessman, historian and diplomat. He was born in Marseille.

Biography

Charles-Roux, the son of Jules Charles-Roux, studied at the École libre des sciences politiques. T ...

, the

Secretary-General for Foreign Affairs, and with the support of

Maxime Weygand

Maxime Weygand (; 21 January 1867 – 28 January 1965) was a French military commander in World War I and World War II.

Born in Belgium, Weygand was raised in France and educated at the Saint-Cyr military academy in Paris. After graduating in 1 ...

and Lebrun, Pétain stood firm, which led Laval to withdraw, followed by Marquet in solidarity. After the armistice,

Raphaël Alibert

Raphaël Alibert (17 February 1887, Saint-Laurent, Lot – 5 June 1963, Paris) was a French politician.

Politics

Raphael Alibert was an ardent Roman Catholic convert and someone with strong royalist ideas. One of the most intense followers ...

convinced Pétain of the need to rely on Laval, and the two rejoined the government.

Pétain obtained the participation of the SFIO by bringing back

Albert Rivière

Albert Rivière (24 April 1891 – 28 June 1953) was a French tailor and moderate socialist politician. He was Minister of Pensions (France), Minister of Pensions between 1936 and 1940, and was briefly Minister of Colonies (France), Minister of Col ...

and with the agreement of

Léon Blum

André Léon Blum (; 9 April 1872 – 30 March 1950) was a French socialist politician and three-time Prime Minister.

As a Jew, he was heavily influenced by the Dreyfus affair of the late 19th century. He was a disciple of French Socialist le ...

.

The following is a list of the French government ministers in the administration of Pétain under the Third Republic.

Composition

End of administration

On 10 July 1940, the

French National Assembly

The National Assembly (french: link=no, italics=set, Assemblée nationale; ) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are known a ...

Assemblée nationale

The National Assembly (french: link=no, italics=set, Assemblée nationale; ) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are known a ...

met in

Vichy

Vichy (, ; ; oc, Vichèi, link=no, ) is a city in the Allier Departments of France, department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of central France, in the historic province of Bourbonnais.

It is a Spa town, spa and resort town and in World ...

and

voted to give absolute power to Pétain in the

Constitutional Law of 1940, effectively dissolving itself, and ending the Third Republic. The

Vichy regime

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

began.

Vichy governments

Pétain and the French State

In the French State under Pétain, French authorities willingly enacted and enforced antisemitic laws, unprompted by Berlin. His collaborationist government helped send 75,721 Jewish refugees and French citizens to Nazi death camps.

First Laval administration (1940)

The fifth government formed by Pierre Laval was the first administration formed by Pétain under the

Vichy regime

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

after the

vote of 10 July 1940 ceded full

constituent

Constituent or constituency may refer to:

Politics

* An individual voter within an electoral district, state, community, or organization

* Advocacy group or constituency

* Constituent assembly

* Constituencies of Namibia

Other meanings

* Const ...

powers to Pétain. The government ended on 13 December 1940 with Laval's dismissal. This administration was not recognized as legitimate by the

Empire Defense Council

The Empire Defense Council (also called Council of Defense of the Empire, from french: Conseil de défense de l'Empire) was the embodiment of Free France which constituted the government from 1940 to 1941. Subsequently, this role was assumed b ...

of the government of

Free France

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

, which the British Government had quickly recognized as the legitimate government of France following De Gaulle's radio appeals to the French public.

Formation

The government of Philippe Pétain signed the

armistice with Germany

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

on 22 June 1940, put an end to the

Third Republic on 10 July 1940 by a vote conveying full powers to Pétain and followed up with three on 11 July. Meanwhile, on 11 July

General de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

created the

Empire Defense Council

The Empire Defense Council (also called Council of Defense of the Empire, from french: Conseil de défense de l'Empire) was the embodiment of Free France which constituted the government from 1940 to 1941. Subsequently, this role was assumed b ...

, which was recognized by the British Government as the legitimate successor of the Third Republic, which had allied itself with Great Britain in the war against the Nazis.

On 12 July 1940 Pétain named

Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occu ...

,

second Minister of State of the last government of the Third Republic under Philippe Pétain as

vice-president of the Council., while Pétain remained simultaneously

head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

and

head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

. Constitutional Act #4 made Laval next in the line of succession should something happen to Pétain. On 16 July, Pétain formed the first government of the Vichy régime and kept Pierre Laval on as vice-president of the Council.

Laval's administration more or less coincides with the arrival in France of

Fritz Sauckel

Ernst Friedrich Christoph "Fritz" Sauckel (27 October 1894 – 16 October 1946) was a German Nazi politician, ''Gauleiter'' of Gau Thuringia from 1927 and the General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment (''Arbeitseinsatz'') from March 1942 unti ...

, tasked by Hitler with procuring qualified manpower. Until then, fewer than 100 000 French workers had voluntarily travelled to Germany to work

[Cointet 1993, p. 378-380] Refusal to send 150 000 skilled workers had been one of the causes of the fall of Darlan. Sauckel demanded 250,000 additional workers before the end of July 1942.

Laval fell back on his favorite tactic of negotiating, stalling for time, and seeking reciprocation. He proposed the ''relève'', in which a prisoner of war would be freed for every three workers sent to Germany, and announced it 22 June 1942, after the same day, in a letter to

Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

, the German minister of foreign affairs, Laval framing the ''relève'' policy as French participation, by providing workers, in the German war effort.

"They give their blood. Give your labour to save Europe from Bolshevism".

Nazi propaganda leaflet suggesting French workers travel to Germany to support the war effort on the eastern front (1943)

The voluntary ''relève'', was replaced by the

Service du travail obligatoire

The ' ( en, Compulsory Work Service; STO) was the forced enlistment and deportation of hundreds of thousands of French workers to Nazi Germany to work as forced labour for the German war effort during World War II.

The STO was created under law ...

(STO) which began in August 1942 throughout occupied Europe. To Sauckel, the ''relève'' had failed, since fewer than 60 000 French workers had gone to Germany by the end of August. He threatened to issue an ''

ordonnance

In French politics, an ''ordonnance'' (, "order") is a statutory instrument issued by the Council of Ministers in an area of law normally reserved for primary legislation enacted by the French Parliament. They function as temporary statutes pend ...

'' to requisition male and female manpower. This ''ordonnance'' would only have had effect in the occupied zone. Laval negotiated a French law covering both zones instead. Laval put workplace inspection, the police and the gendarmerie at the service of forced impressments of labor, and tracking Service du travail obligatoire scofflaws.

[Raphaël Spina, "Impacts du STO sur le travail des entreprises", in Christian Chevandier and Jean-Claude Daumas, Actes du colloque Travailler dans les entreprises sous l'occupation, Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté, 2007] Forced impressments of workers, guarded by ''gendarmes'' until they boarded a train, drew hostile reactions. On 13 October 1942 the Oullins incidents broke out in the suburbs of Lyon, where workers at the railway station went on strike. Someone wrote "Laval assassin!" (Laval murderer) on the trains. The government was forced to back away; on 1 December 1942 only 2,500 requisitioned workers had left the southern zone.

On 1 January 1943, Sauckel demanded, in addition to the 240,000 workers already sent to Germany, a new contingent of 250,000 men, before mid-March To meet these objectives, German forces organised ineffectively brutal raids, which led Laval to propose to the Council of Ministers on 5 February 1943 legislation creating the STO, under which youth born in 1920-1922 were requisitioned for work service in Germany

[Kupferman 2006, p. 467-468] Laval mitigated his legislation with many exceptions.

In all, 600 000 men left between June 1942 and August 1943

[Cointet 1993, p. 433-434,] despite what Sauckel denounced in a letter to Hitler as "pure and simple sabotage", after meeting more than seven hours on 6 August 1943 with Laval, who again attempted to minimize the number of requisitioned workers and refused to his demand for 50 000 workers for Germany before the end of 1943.

[Kupferman 2006, p. 479-480]

On 15 September 1943, Reich minister for Armament and War Production

Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as the Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of World War II. A close ally of Adolf Hitler, he ...

reached an agreement with Laval minister

Jean Bichelonne

Jean Bichelonne (24 December 1904 – 22 December 1944) was a French businessman and member of the Vichy government that governed France during World War II following the occupation of France by Nazi Germany.

Early life

Jean Bichelonne was born o ...

[Kupferman 2006, p. 492] — an agreement Laval was counting on to "block the deportation machine".

Many businesses working for Germany were removed from Sauckel's requisition.

Individuals were protected but the French economy as a whole was integrated into that of Germany. In November 1943, Sauckel demanded,

[ without much success, 900 000 additional workers.]

Initial composition

* Head of the French State, President of the Council, Philippe Pétain.

* Vice president of the Council in charge of Information (18 July 1940) and secretary of state for foreign afairs from 28 octobre 1940 (dismissed 13 décembre 1940) : Pierre Laval

* Keeper of the Seals

The title keeper of the seals or equivalent is used in several contexts, denoting the person entitled to keep and authorize use of the great seal of a given country. The title may or may not be linked to a particular cabinet or ministerial offi ...

() and Minister Secretary of State for Justice (until January 1941): Raphaël Alibert

Raphaël Alibert (17 February 1887, Saint-Laurent, Lot – 5 June 1963, Paris) was a French politician.

Politics

Raphael Alibert was an ardent Roman Catholic convert and someone with strong royalist ideas. One of the most intense followers ...

* Minister Secretary of State for Finance (until April 1942): Yves Bouthillier

Yves Bouthillier (26 February 1901 – 4 January 1977) was a French politician. He served as the French Minister of Finance from 1940 to 1942.

Early life

Bouthillier was born in Saint-Martin-de-Ré to Mathilde Bouju and Louis Bouthillier, a merc ...

* Minister Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (until 28 October 1940), then Minister Secretary of State for the President of the Council (28 October 1940–2 January 1941): Paul Baudouin

* Secretary of State for Food and Agriculture, then Minister of Agriculture (December 1940-April 1942): Pierre Caziot

Pierre Caziot (24 September 1876 – 4 January 1953) was a French agricultural expert and administrator who was Minister of Agriculture and Supplies in the Vichy government during World War II (1939–45). He was a strong believer in the value of t ...

* Minister Secretary of State for Industrial Production and Labour (until February 1941), then Minister of Labour (until April 1942): René Belin

René Belin (14 April 1898 – 2 January 1977) was a French trade unionist and politician. In the 1930s he became one of the leaders of the French General Confederation of Labour.

He was strongly opposed to communism. In the prelude to World War ...

* Minister Secretary of State for National Defence (dismissed from the Government as of September 1940): General Maxime Weygand

Maxime Weygand (; 21 January 1867 – 28 January 1965) was a French military commander in World War I and World War II.

Born in Belgium, Weygand was raised in France and educated at the Saint-Cyr military academy in Paris. After graduating in 1 ...

(then Delegate General in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

and Commander-in-Chief of the French forces in North Africa until November 1941)

* Secretary of State for War (Army) (discharged from the government as of September 1940: General

* Secretary of State for Aviation (dismissed from the government as of September 1940: General

* Secretary of State, then Minister of the Navy: Admiral François Darlan

Jean Louis Xavier François Darlan (7 August 1881 – 24 December 1942) was a French admiral and political figure. Born in Nérac, Darlan graduated from the ''École navale'' in 1902 and quickly advanced through the ranks following his service d ...

* Minister Secretary of State for the Interior (dismissed from the government as of September 1940 as a former parliamentarian): Adrien Marquet

Adrien Marquet (6 October 1884 – 3 February 1955) was a socialist mayor of Bordeaux who turned to the far right.

Career

Marquet was born in Bordeaux and became its socialist mayor in 1925. In 1933, he was expelled from the French Section of ...

* Minister Secretary of State for Public Education and Fine Arts (dismissed from the government as of September 1940 because he was a former parliamentarian): Émile Mireaux

Émile Mireaux (21 August 1885 – 27 December 1969) was a French economist, journalist, politician and literary historian.

In the 1930s he edited ''Le Temps'' and contributed to other right-leaning journals.

He became a senator in 1936, and briefl ...

* Minister Secretary of State for Family and Youth (dismissed from the government as of September 1940 as a former parliamentarian): Jean Ybarnegaray

Jean may refer to:

People

* Jean (female given name)

* Jean (male given name)

* Jean (surname)

Fictional characters

* Jean Grey, a Marvel Comics character

* Jean Valjean, fictional character in novel ''Les Misérables'' and its adaptations

* J ...

* Minister Secretary of State for Communications (dismissed from the government as of September 1940 as a former parliamentarian): François Piétri François Piétri (8 August 1882 – 17 August 1966) was a minister in several governments in the later years of the French Third Republic and was French ambassador to Spain from 1940 to 1944 under the Vichy regime.

Born in Bastia, Corsica to Antoi ...

* Minister Secretary of State for the Colonies (dismissed from the government as of September 1940 as a former parliamentarian): Henry Lémery

Henry Lémery (9 December 1874 – 26 April 1972) was a politician from Martinique who served in the French National Assembly from 1914–1919 and the French Senate from 1920–1941. Lémery was briefly Ministry of Justice (France), Minister of Jus ...

Reshuffles

= 16 July 1940

=

The following joined on 16 July 1940:

* Secretary General for Justice:

* Secretary General for Public Finance:

* Secretary General to the Presidency of the Council:

* Secretary General for Economic Affairs:

* Secretary General for Public Works and Transport:

= September 1940

=

The following joined in September 1940, replacing eight dismissed ministers:

* Minister of the Interior : Marcel Peyrouton

Marcel Peyrouton (2 July 1887 – 6 November 1983) was a French diplomat and politician. He served as the French Minister of the Interior from 1940 to 1941, during Vichy France. He served as the French Ambassador to Argentina from 1936 to 1940, an ...

* Minister of War (September 1940) and Commander-in-Chief of the Land Forces (until November 1941): General Charles Huntziger

Charles Huntziger (; 25 June 1880 – 11 November 1941) was a French Army general during World War I and World War II.

He was born at Lesneven (Finistère), in Brittany of a family which settled in the region, after the Prussian invasion of Alsace ...

* Secretary of State for Aviation: General

* Secretary of State for Communications (until April 1942:

* Secretary of State for Public Education and Youth (until 13 December 1940: Georges Ripert

Georges Ripert (22 April 1880 – 4 July 1958) was a lawyer who was briefly Secretary of State for Public Instruction and Youth in the Vichy Regime.

Early career

Ripert received his agrégation in 1906 from the Faculty of Law of Aix.

He taught M ...

* Secretary of State for the Colonies (until April 1942: Admiral Charles Platon

René-Charles Platon (19 September 1886 – 28 August 1944) was a French admiral who was responsible for the Colonial Ministry under the Vichy government.

He was a passionate supporter of the ''Révolution nationale'' (National Revolution) of Vich ...

* Secretary General for Youth:

= 18 November 1940

=

The following were appointed on 18 November 1940:

* Secretary General of the Head of State: Émile Laure

Auguste Marie Émile Laure (3 June 1881 – 1957) was a French general

He was born on 3 June 1881 in Apt, Vaucluse, France. His father was Jacques Ernest Laure (Ingénieur des Arts et Manufactures). His mother was Marguerite Marie Louise Duval ...

= Transition 13 December 1940

=

Laval was sacked by Pétain on 13 December 1940. This came as a surprise to Laval. He was replaced by a triumvirate of Flandin, Darlan, and General Charles Huntziger

Charles Huntziger (; 25 June 1880 – 11 November 1941) was a French Army general during World War I and World War II.

He was born at Lesneven (Finistère), in Brittany of a family which settled in the region, after the Prussian invasion of Alsace ...

. This caused friction with Hitler's representative Otto Abetz

Heinrich Otto Abetz (26 March 1903 – 5 May 1958) was the German ambassador to Vichy France during the Second World War and a convicted war criminal. In July 1949 he was sentenced to twenty years' hard labour by a Paris military tribunal, he was ...

, who was furious about Vichy's insufficient collaboration, and closed the demarcation line

{{Refimprove, date=January 2008

A political demarcation line is a geopolitical border, often agreed upon as part of an armistice or ceasefire.

Africa

* Moroccan Wall, delimiting the Moroccan-controlled part of Western Sahara from the Sahrawi- ...

in response.

Flandin regime

The second government of Pierre-Étienne Flandin

Pierre-Étienne Flandin (; 12 April 1889 – 13 June 1958) was a French conservative politician of the Third Republic, leader of the Democratic Republican Alliance (ARD), and Prime Minister of France from 8 November 1934 to 31 May 1935.

A milit ...

was the second government of the Vichy regime in France, formed by Philippe Pétain. It succeeded the first Pierre Laval government on 14 December 1940 and ended on 9 February 1941.

The Germans were unhappy after the sacking of Laval on 13 December, and suspicious of Flandin and whether he was sufficiently collaborationist. Darlan met with Hitler on 25 December and endured his anger, assuring Hitler that Vichy was still committed to collaboration. There followed several months of intrigue while Flandin was in power, during which Pétain even considered taking Laval back, however Laval was now no longer interested in anything other than supreme power. The impasse was lifted after the Germans had a change of heart with respect to Darlan, although not toward Flandin who they considered insufficiently collaborationist, and this led to Flandin's resignation on 9 February 1941, and Darlan's accession.

Carryovers from Laval

The majority of ministers, secretaries, and delegates were carried over from the Laval government that ended 13 December 1940.

*Head of the French State, Council President: Philippe Pétain.

*Guardian of the Seals and Minister-Secretary of the State for Justice (until January 1941): Raphaël Alibert

Raphaël Alibert (17 February 1887, Saint-Laurent, Lot – 5 June 1963, Paris) was a French politician.

Politics

Raphael Alibert was an ardent Roman Catholic convert and someone with strong royalist ideas. One of the most intense followers ...

*Minister of Finance (until April 1942): Yves Bouthillier

Yves Bouthillier (26 February 1901 – 4 January 1977) was a French politician. He served as the French Minister of Finance from 1940 to 1942.

Early life

Bouthillier was born in Saint-Martin-de-Ré to Mathilde Bouju and Louis Bouthillier, a merc ...

*Minister-Secretary of the State to the Council President's Office (28 October 1940 to 2 January 1941) and Minister of Information (December 1940 to 2 January 1941): Paul Baudouin

Paul Baudouin (19 December 1894 – 10 February 1964) was a French banker who became a politician and Foreign Minister of France for the last six months of 1940. He was instrumental in arranging a cessation of hostilities between France and Germa ...

*Minister of Agriculture (December 1940 to April 1942): Pierre Caziot

Pierre Caziot (24 September 1876 – 4 January 1953) was a French agricultural expert and administrator who was Minister of Agriculture and Supplies in the Vichy government during World War II (1939–45). He was a strong believer in the value of t ...

*Minister of Industrial Production and Labour (until February 1941): René Belin

René Belin (14 April 1898 – 2 January 1977) was a French trade unionist and politician. In the 1930s he became one of the leaders of the French General Confederation of Labour.

He was strongly opposed to communism. In the prelude to World War ...

*Delegate General to North Africa and commander in chef of Vichy forces in North Africa (until November 1941): General Maxime Weygand

Maxime Weygand (; 21 January 1867 – 28 January 1965) was a French military commander in World War I and World War II.

Born in Belgium, Weygand was raised in France and educated at the Saint-Cyr military academy in Paris. After graduating in 1 ...

*Minister of the Marine: Admiral François Darlan

Jean Louis Xavier François Darlan (7 August 1881 – 24 December 1942) was a French admiral and political figure. Born in Nérac, Darlan graduated from the ''École navale'' in 1902 and quickly advanced through the ranks following his service d ...

*Minister of the Interior: Marcel Peyrouton

Marcel Peyrouton (2 July 1887 – 6 November 1983) was a French diplomat and politician. He served as the French Minister of the Interior from 1940 to 1941, during Vichy France. He served as the French Ambassador to Argentina from 1936 to 1940, an ...

*Minister of War (September 1940) and Commander in chief of ground forces (until November 1941): General Charles Huntziger

Charles Huntziger (; 25 June 1880 – 11 November 1941) was a French Army general during World War I and World War II.

He was born at Lesneven (Finistère), in Brittany of a family which settled in the region, after the Prussian invasion of Alsace ...

*Secretary of the State for Aviation: General

*Secretary of the State for Communications (until April 1942):

*Secretary of the State for the Colonies (until April 1942): Admiral Charles Platon

René-Charles Platon (19 September 1886 – 28 August 1944) was a French admiral who was responsible for the Colonial Ministry under the Vichy government.

He was a passionate supporter of the ''Révolution nationale'' (National Revolution) of Vich ...

*Secretary General for Justice:

*Secretary General for Public Finance:

*Secretary General to the Office of Council President:

*Secretary General for Youth:

*Secretary General of the Head of State: Émile Laure

Auguste Marie Émile Laure (3 June 1881 – 1957) was a French general

He was born on 3 June 1881 in Apt, Vaucluse, France. His father was Jacques Ernest Laure (Ingénieur des Arts et Manufactures). His mother was Marguerite Marie Louise Duval ...

*Secretary General for Economic Questions:

*Secretary General for Transport and Public Works: Maurice Schwarz

Named 13 December 1940

* Vice-President of the Council and Minister for Foreign Affairs: Pierre-Étienne Flandin

Pierre-Étienne Flandin (; 12 April 1889 – 13 June 1958) was a French conservative politician of the Third Republic, leader of the Democratic Republican Alliance (ARD), and Prime Minister of France from 8 November 1934 to 31 May 1935.

A milit ...

* Minister of National Education: Jacques Chevalier

Jacques Chevalier (13 March 1882 – 19 April 1962) was a French Catholic philosopher and a politician.

Chevalier was born in Cérilly, Allier, educated at the École normale supérieure and the University of Oxford and taught at the Faculty of ...

* Secretary of State for Supplies:

* Secretary General for Public Instruction:

Named 27 January 1941

* Keeper of the Seals and Minister Secretary of State for Justice (January 1941 - resigned March 1943): Joseph Barthélemy

Joseph Barthélemy (8 July 1874, Toulouse – 14 May 1945) was a French jurist, politician and journalist. Initially a critic of Nazi Germany, he would go on to serve as a minister in the collaborationist Vichy regime.

Early years

The son of Aim ...

Named 30 January 1941

* Secretary General for Procurement:

Resignation 9 February 1941

Flandin's short period in power was marked by intrigue and Hitler's suspicions about Vichy's level of collaboration with Germany. When it was clear that Darlan had more confidence in Berlin than Flandin did, Flandin resigned on 9 February 1941, leaving the way clear for Darlan.

Darlan regime

After two years at the head of the Vichy government, Admiral Darlan was unpopular and had strengthened ties with Vichy forces, in an expanded collaboration with Germany which seemed to him the least bad solution, and had conceded a great deal, turning over the naval bases at Bizerte

Bizerte or Bizerta ( ar, بنزرت, translit=Binzart , it, Biserta, french: link=no, Bizérte) the classical Hippo, is a city of Bizerte Governorate in Tunisia. It is the northernmost city in Africa, located 65 km (40mil) north of the cap ...

and Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in 2 ...

, an air base in Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

in Syria, as well as vehicles, artillery and ammunition in North Africa and Tunisia, in addition to arming the Iraqis. In exchange Darlan wanted the Germans to reduce the constraints under the armistice, free French prisoners, and eliminate the '' ligne de démarcation''. This irritated the Germans. On 9 March 1942, Hitler signed a decree giving France a chief of the SS and police leader (HSSPF) tasked with organizing the "Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

", following the Wannsee Conference with the French police. The Germans demanded the return of Laval to power, and broke off contact. The Americans intervened on 30 March to prevent another Laval administration.

Government on 25 February

=Timeline

=

*14 May 1941, arrest and detainment of 3,747 Jews in internment camps in the Green ticket roundup

The green ticket roundup (french: rafle du billet vert), also known as the green card roundup, took place on 14 May 1941 during the Nazi occupation of France. The mass arrest started a day after French Police delivered a green card () to 6694 fo ...

.

*2 July 1942, Bousquet and Carl Oberg

Carl Oberg (27 January 1897 – 3 June 1965) was a German SS functionary during the Nazi era. He served as Senior SS and Police Leader (HSSPF) in occupied France, from May 1942 to November 1944, during the Second World War, Oberg came to be kn ...

signed an agreement to collaborate in police matters.

*On 16 and 17 July 1942, Vichy police organised the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup

The Vel' d'Hiv' Roundup ( ; from french: Rafle du Vel' d'Hiv', an abbreviation of ) was a mass arrest of foreign Jewish families by Vichy France, French police and Gendarmerie, gendarmes at the behest of the Nazi Germany, German authorities, tha ...

.

*19 August 1942, Allies launched Operation Jubilee

Operation Jubilee or the Dieppe Raid (19 August 1942) was an Allied amphibious attack on the German-occupied port of Dieppe in northern France, during the Second World War. Over 6,050 infantry, predominantly Canadian, supported by a regiment ...

on the beach at Dieppe

Dieppe (; Norman: ''Dgieppe'') is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to Newha ...

to test German defenses.

*On 3 November 1942, General Erwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel () (15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944) was a German field marshal during World War II. Popularly known as the Desert Fox (, ), he served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of Nazi Germany, as well as servi ...

lost the battle of El-Alamein, halting the Italian-German advance towards the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

and began the retreat of the Afrika Korps

The Afrika Korps or German Africa Corps (, }; DAK) was the German expeditionary force in Africa during the North African Campaign of World War II. First sent as a holding force to shore up the Italian defense of its African colonies, the ...

towards Tunisia.

*On 8 November 1942, the Allies launched landings in Algeria and Morocco (Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

).

*11 November 1942, the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

invaded the previously-unoccupied zone libre

The ''zone libre'' (, ''free zone'') was a partition of the French metropolitan territory during World War II, established at the Second Armistice at Compiègne on 22 June 1940. It lay to the south of the demarcation line and was administered by ...

, and occupied Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

and Bizerte

Bizerte or Bizerta ( ar, بنزرت, translit=Binzart , it, Biserta, french: link=no, Bizérte) the classical Hippo, is a city of Bizerte Governorate in Tunisia. It is the northernmost city in Africa, located 65 km (40mil) north of the cap ...

, without fighting.

*19 November 1942, the Army of Africa again took up the fight against the Germans in Tunisia, in Majaz al Bab

Majaz al Bab ( ar, مجاز الباب), also known as Medjez el Bab, or as Membressa under the Roman Empire, is a town in northern Tunisia. It is located at the intersection of roads GP5 and GP6, in the ''Plaine de la Medjerda''.

Commonwealth wa ...

.

*On 27 November 1942, the French fleet sank its ship in Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

and the Armistice Army

The Armistice Army or Vichy French Army (french: Armée de l'Armistice) was the common name for the armed forces of Vichy France permitted under the Armistice of 22 June 1940 after the French capitulation to Nazi Germany and Italy. It was off ...

dissolved.

*On 7 December 1942, French West Africa

French West Africa (french: Afrique-Occidentale française, ) was a federation of eight French colonial territories in West Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta (now Burki ...

joined the Allies.

*On 24 December 1942, Admiral François Darlan

Jean Louis Xavier François Darlan (7 August 1881 – 24 December 1942) was a French admiral and political figure. Born in Nérac, Darlan graduated from the ''École navale'' in 1902 and quickly advanced through the ranks following his service d ...

was assassinated in Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

by a young monarchist, Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle

Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle (4 November 1922 – 26 December 1942) was a royalist member of the French resistance during World War II. He assassinated Admiral of the Fleet François Darlan, the former chief of government of Vichy France and the ...

.

*February 1943 - German troops are surrounded at Stalingrad

Volgograd ( rus, Волгогра́д, a=ru-Volgograd.ogg, p=vəɫɡɐˈɡrat), geographical renaming, formerly Tsaritsyn (russian: Цари́цын, Tsarítsyn, label=none; ) (1589–1925), and Stalingrad (russian: Сталингра́д, Stal ...

.

*30 January 1943, Laval created the French Milice

The ''Milice française'' (French Militia), generally called ''la Milice'' (literally ''the militia'') (), was a political paramilitary organization created on 30 January 1943 by the Vichy France, Vichy regime (with Nazi Germany, German aid) t ...

(militia).

*March 1943, French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label=French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic ...

joined the Allies.

*13 May 1943, Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

*Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinate ...

forces surrender in Tunisia.

*24 May 1943, first Vichy Milice

The ''Milice française'' (French Militia), generally called ''la Milice'' (literally ''the militia'') (), was a political paramilitary organization created on 30 January 1943 by the Vichy France, Vichy regime (with Nazi Germany, German aid) t ...

member is killed by the French Resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

.

*31 May 1943, Vichy forces pinned in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

joined the African Free French Naval Forces

The Free French Naval Forces (french: Forces Navales Françaises Libres, or FNFL) were the naval arm of the Free French Forces during the Second World War. They were commanded by Admiral Émile Muselier.

History

In the wake of the Armistice a ...

.

*15 July 1943, French Antilles

The French West Indies or French Antilles (french: Antilles françaises, ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Antiy fwansez) are the parts of France located in the Antilles islands of the Caribbean:

* The two overseas departments of:

** Guadeloup ...

joined Free France

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

.

*5 October 1943, Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

became the first region of Metropolitan France

Metropolitan France (french: France métropolitaine or ''la Métropole''), also known as European France (french: Territoire européen de la France) is the area of France which is geographically in Europe. This collective name for the European ...

liberated by the French Liberation Army

__NOTOC__

The French Liberation Army (french: Armée française de la Libération or AFL) was the reunified French Army that arose from the merging of the Armée d'Afrique with the prior Free French Forces (french: Forces françaises libres, l ...

and the Italian Armed Forces of the Occupation.

*1 January 1944, Joseph Darnand

Joseph Darnand (19 March 1897 – 10 October 1945) was a French collaborator with Nazi Germany during World War II. A decorated soldier in the French Army of World War I and early World War II, he went on to become the organizer and ''de facto ...

is named Secretary-General for Maintaining Order.

*6 June 1944, Allies launch Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The operat ...

in Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

(D Day).

*15 August 1944, Allies land in Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bor ...

and move from Normandy towards Paris, and the liberation of France

The liberation of France in the Second World War was accomplished through diplomacy, politics and the combined military efforts of the Allied Powers of World War II, Allied Powers, Free French forces in London and Africa, as well as the French R ...

accelerates.

*17 August 1944, Pierre Laval, head of government and Minister for Foreign Affairs, held his last council meeting in Paris. The Germans wanted to maintain a "French government" in the hope of stabilizing the front in Eastern France and in case they could reconquer it. The same day, in Vichy, Cecil von Renthe-Fink

Cecil may refer to:

People with the name

* Cecil (given name), a given name (including a list of people and fictional characters with the name)

* Cecil (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

Places Canada

*Cecil, Alberta, ...

, the German minister-delegate, asked Pétain to travel to the northern zone, but he refused and asked for this instruction to be made in writing.[Robert Aron, Grands dossiers de l'histoire contemporaine, op. cit., p. 41–42.]

*18 August, von Renthe-Fink asks twice more.

*19 August, at 11:30 am, von Renthe-Fink returned to the hôtel du Parc, résidence of the Maréchal, accompanied by General von Neubroon, who said he had "formal orders from Berlin".

Second Laval administration (1942-1944)

After two years at the head of the Vichy regime

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

, François Darlan's government was unpopular, a victim of the fool's bargain he had made with the Germans. Darlan committed Vichy into further collaboration with Germany as the least bad solution for him, giving up much ground: handover of the naval bases at Bizerte

Bizerte or Bizerta ( ar, بنزرت, translit=Binzart , it, Biserta, french: link=no, Bizérte) the classical Hippo, is a city of Bizerte Governorate in Tunisia. It is the northernmost city in Africa, located 65 km (40mil) north of the cap ...

and Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in 2 ...

, an air base in Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

(Syria), vehicles, artillery and ammunition in North Africa, Tunisia, not to mention the delivery of arms to Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

.

In exchange, Darlan asked the Germans for a quid pro quo (reduction of the constraints of the armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

: release of French prisoners, elimination of the demarcation line

{{Refimprove, date=January 2008

A political demarcation line is a geopolitical border, often agreed upon as part of an armistice or ceasefire.

Africa

* Moroccan Wall, delimiting the Moroccan-controlled part of Western Sahara from the Sahrawi- ...

and fuel oil for the French fleet), which irritated them.

On 9 March 1942, Hitler signed the decree endowing France with a " Higher SS and police leader" (HSSPf) responsible for organizing the Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

after the Wannsee Conference with the French Police. The Germans then demanded that Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occu ...

return to power, and in the meantime they broke off all contact.

On 30 March 1942, the Americans intervened in Vichy against Laval's return to power.

Composition

* French Head of State, President of the Council:[ "By the conjunction of events precipitating a concentration of presidential and governmental powers in the hands of a single one, as in the case of the last President of the Council of the Republic also becoming the first head of the new French State, the person of Pétain finds himself at the same time invested with new executive functions without having been dispossessed of his former governmental attributions." See in particular note 42, p. 16. It is noted that although Laval as head of government does not bear the title of President of the Council, Pétain continues to hold the title and exercise the powers attached to it. Cf. on this subject AN 2AG 539 CC 140 B and Marc-Olivier Baruch, op cit p., 334-335 and 610.] Marshal Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of World ...

.

* Head of Government, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of the Interior and Minister of Information : Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occu ...

* Minister of War: Eugène Bridoux

Eugène Bridoux (1888-1955) was a French general. He served as Secretary of State for War, later Secretary of State for Defence, under Vichy France during World War II.

Early life

Eugène Bridoux was born on 24 June 1888 in Doulon, now a suburb o ...

* Minister of Finance and National Economy: Pierre Cathala

Pierre Cathala (1888 – 1947) was a French politician. He served as the French Minister of Finance from 1942 to 1944.

Early life

Pierre Cathala was born on 22 September 1888 in Montfort-sur-Meu, Brittany, France. He was educated at the Lyc� ...

* Minister of Industrial Production: Jean Bichelonne

Jean Bichelonne (24 December 1904 – 22 December 1944) was a French businessman and member of the Vichy government that governed France during World War II following the occupation of France by Nazi Germany.

Early life

Jean Bichelonne was born o ...

* Minister of Labour: Hubert Lagardelle

Hubert Lagardelle (8 July 1874 – 20 September 1958) was a pioneer of French revolutionary syndicalism. He regularly authored reviews for the Plans magazine, was co-founder of the journal Prélude, and Minister of Labour in the Vichy regime.

...

* Minister of Justice: Joseph Barthélemy

Joseph Barthélemy (8 July 1874, Toulouse – 14 May 1945) was a French jurist, politician and journalist. Initially a critic of Nazi Germany, he would go on to serve as a minister in the collaborationist Vichy regime.

Early years

The son of Aim ...

* Minister of the Navy: Gabriel Auphan

Counter-admiral Gabriel Paul Auphan (November 4, 1894, Alès – April 16, 1982) was a French naval officer who became the State Secretary of the Navy (secrétaire d'État à la Marine) of the Vichy government from April to November 1942.

N ...

* Minister of Air: Jean-François Jannekeyn

Jean-François Jannekeyn (16 November 1892 – 17 November 1971) was a French military aviator, general, politician and Olympic fencer.

A World War I flying ace credited with five aerial victories as a bomber pilot, he flew a Breguet 14.Th ...

* Minister of National Education: Abel Bonnard

Abel Bonnard (19 December 1883 31 May 1968) was a French poet, novelist and politician.

Biography

Born in Poitiers, Vienne, his early education was in Marseilles with secondary studies at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris. A student of literatur ...

* Minister of Agriculture: Jacques Le Roy Ladurie

* Minister of Supply : Max Bonnafous

Max Bonnafous (21 January 1900 – 16 October 1975) was a French sociologist who was Minister of Agriculture and Supplies from 1942 to 1944 in the Vichy government.

Early years

Max Bonnafous was born on 21 January 1900 in Bordeaux, Gironde.

He gr ...

* Minister of Colonies : Jules Brévié

Joseph-Jules Brévié (12 March 1880 – 28 July 1964) was a French colonial administrator who became governor-general of French West Africa from 1930 to 1936, and then governor-general of French Indochina from 1937 to 1939. He promoted liberal an ...

* Minister of Family and Health : Raymond Grasset

Raymond Grasset (10 January 1892 - 8 February 1968) was a French politician. He began his career as a physician. He was the Secretary (or Minister) of Family and Health from 18 April 1942 to 20 August 1944.

References

1892 births

1968 dea ...

* Minister of Communications:

* Minister of State: Lucien Romier

Lucien Romier ( Moiré, 19 October 1885 – Vichy, 5 January 1944) was a French journalist and politician.

After studying at the École des Chartes where he wrote a thesis on Jacques d'Albon de Saint-André, he was a member of the French Sch ...

* General Delegate of the government in the occupied territories: Fernand de Brinon

Fernand de Brinon, Marquis de Brinon (; 26 August 1885 – 15 April 1947) was a French lawyer and journalist who was one of the architects of French collaboration with the Nazis during World War II. He claimed to have had five private talks with ...

(de Brinon was later head of the Sigmaringen enclave

The Sigmaringen enclave was the exiled remnant of France's Nazi-sympathizing Vichy government which fled to Germany during the Liberation of France near the end of World War II in order to avoid capture by the advancing Allied forces. ...

)