Prussian P on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the

In 1211 King Andrew II of Hungary granted Burzenland in Transylvania as a fiefdom to the Teutonic Knights, a German

In 1211 King Andrew II of Hungary granted Burzenland in Transylvania as a fiefdom to the Teutonic Knights, a German

On 10 April 1525, after signing of the Treaty of Kraków, which officially ended the

On 10 April 1525, after signing of the Treaty of Kraków, which officially ended the

Frederick William I succeeded in organizing the electorate by establishing an absolute monarchy in Brandenburg-Prussia, an achievement for which he became known as the "Great Elector". Above all, he emphasised the importance of a powerful military to protect the state's disconnected territories, while the Edict of Potsdam (1685) opened Brandenburg-Prussia for the immigration of Protestant refugees (especially Huguenots), and he established a bureaucracy to carry out state administration efficiently.

Frederick William I succeeded in organizing the electorate by establishing an absolute monarchy in Brandenburg-Prussia, an achievement for which he became known as the "Great Elector". Above all, he emphasised the importance of a powerful military to protect the state's disconnected territories, while the Edict of Potsdam (1685) opened Brandenburg-Prussia for the immigration of Protestant refugees (especially Huguenots), and he established a bureaucracy to carry out state administration efficiently.

On 18 January 1701, Frederick William's son, Elector Frederick III, elevated Prussia from a duchy to a kingdom and crowned himself King Frederick I. In the Crown Treaty of 16 November 1700, Leopold I, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, allowed Frederick only to title himself " King in Prussia", not " King of Prussia". The state of

On 18 January 1701, Frederick William's son, Elector Frederick III, elevated Prussia from a duchy to a kingdom and crowned himself King Frederick I. In the Crown Treaty of 16 November 1700, Leopold I, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, allowed Frederick only to title himself " King in Prussia", not " King of Prussia". The state of  The king died in 1740 and was succeeded by his son, Frederick II, whose accomplishments led to his reputation as "Frederick the Great". As crown prince, Frederick had focused, primarily, on philosophy and the arts. He was an accomplished flute player. In 1740, Prussian troops crossed over the undefended border of Silesia and occupied Schweidnitz. Silesia was the richest province of Habsburg Austria. It signalled the beginning of three Silesian Wars (1740–1763). The First Silesian War (1740–1742) and the

The king died in 1740 and was succeeded by his son, Frederick II, whose accomplishments led to his reputation as "Frederick the Great". As crown prince, Frederick had focused, primarily, on philosophy and the arts. He was an accomplished flute player. In 1740, Prussian troops crossed over the undefended border of Silesia and occupied Schweidnitz. Silesia was the richest province of Habsburg Austria. It signalled the beginning of three Silesian Wars (1740–1763). The First Silesian War (1740–1742) and the

During the reign of King Frederick William II (1786–1797), Prussia annexed additional Polish territory through the Second Partition of Poland in 1793 and the Third Partition of Poland in 1795. His successor, Frederick William III (1797–1840), announced the union of the Prussian Lutheran and Reformed churches into

During the reign of King Frederick William II (1786–1797), Prussia annexed additional Polish territory through the Second Partition of Poland in 1793 and the Third Partition of Poland in 1795. His successor, Frederick William III (1797–1840), announced the union of the Prussian Lutheran and Reformed churches into  Prussia took a leading part in the French Revolutionary Wars, but remained quiet for more than a decade because of the Peace of Basel of 1795, only to go once more to war with France in 1806 as negotiations with that country over the allocation of the spheres of influence in Germany failed. Prussia suffered a devastating defeat against

Prussia took a leading part in the French Revolutionary Wars, but remained quiet for more than a decade because of the Peace of Basel of 1795, only to go once more to war with France in 1806 as negotiations with that country over the allocation of the spheres of influence in Germany failed. Prussia suffered a devastating defeat against

The first half of the 19th century saw a prolonged struggle in Germany between liberals, who wanted a united, federal Germany under a democratic constitution, and conservatives, who wanted to maintain Germany as a patchwork of independent, monarchical states with Prussia and Austria competing for influence. One small movement that signalled a desire for German unification in this period was the Burschenschaft student movement, by students who encouraged the use of the black-red-gold flag, discussions of a unified German nation, and a progressive, liberal political system. Because of Prussia's size and economic importance, smaller states began to join its free trade area in the 1820s. Prussia benefited greatly from the creation in 1834 of the German Customs Union ( Zollverein), which included most German states but excluded Austria.

In 1848 the liberals saw an opportunity when revolutions broke out across Europe. Alarmed, King Frederick William IV agreed to convene a National Assembly and grant a constitution. When the Frankfurt Parliament offered Frederick William the crown of a united Germany, he refused on the grounds that he would not accept a crown from a revolutionary assembly without the sanction of Germany's other monarchs.

The Frankfurt Parliament was forced to dissolve in 1849, and Frederick William issued Prussia's first constitution by his own authority in 1850. This conservative document provided for a two-house parliament. The lower house, or '' Landtag'' was elected by all taxpayers, who were divided into three classes whose votes were weighted according to the amount of taxes paid. Women and those who paid no taxes had no vote. This allowed just over one-third of the voters to choose 85% of the legislature, all but assuring dominance by the more well-to-do men of the population. The upper house, which was later renamed the '' Herrenhaus'' ("House of Lords"), was appointed by the king. He retained full executive authority and ministers were responsible only to him. As a result, the grip of the landowning classes, the Junkers, remained unbroken, especially in the eastern provinces.

The first half of the 19th century saw a prolonged struggle in Germany between liberals, who wanted a united, federal Germany under a democratic constitution, and conservatives, who wanted to maintain Germany as a patchwork of independent, monarchical states with Prussia and Austria competing for influence. One small movement that signalled a desire for German unification in this period was the Burschenschaft student movement, by students who encouraged the use of the black-red-gold flag, discussions of a unified German nation, and a progressive, liberal political system. Because of Prussia's size and economic importance, smaller states began to join its free trade area in the 1820s. Prussia benefited greatly from the creation in 1834 of the German Customs Union ( Zollverein), which included most German states but excluded Austria.

In 1848 the liberals saw an opportunity when revolutions broke out across Europe. Alarmed, King Frederick William IV agreed to convene a National Assembly and grant a constitution. When the Frankfurt Parliament offered Frederick William the crown of a united Germany, he refused on the grounds that he would not accept a crown from a revolutionary assembly without the sanction of Germany's other monarchs.

The Frankfurt Parliament was forced to dissolve in 1849, and Frederick William issued Prussia's first constitution by his own authority in 1850. This conservative document provided for a two-house parliament. The lower house, or '' Landtag'' was elected by all taxpayers, who were divided into three classes whose votes were weighted according to the amount of taxes paid. Women and those who paid no taxes had no vote. This allowed just over one-third of the voters to choose 85% of the legislature, all but assuring dominance by the more well-to-do men of the population. The upper house, which was later renamed the '' Herrenhaus'' ("House of Lords"), was appointed by the king. He retained full executive authority and ministers were responsible only to him. As a result, the grip of the landowning classes, the Junkers, remained unbroken, especially in the eastern provinces.

In 1862 King Wilhelm I appointed

In 1862 King Wilhelm I appointed

Bismarck realised that the dual administration of Schleswig and Holstein was only a temporary solution, and tensions rose between Prussia and Austria. The struggle for supremacy in Germany then led to the

Bismarck realised that the dual administration of Schleswig and Holstein was only a temporary solution, and tensions rose between Prussia and Austria. The struggle for supremacy in Germany then led to the

The controversy with the Second French Empire over the candidacy of a

The controversy with the Second French Empire over the candidacy of a

The two decades after the unification of Germany were the peak of Prussia's fortunes, but the seeds for potential strife were built into the Prusso-German political system.

The constitution of the German Empire was a version of the North German Confederation's constitution. Officially, the German Empire was a federal state. In practice, Prussia overshadowed the rest of the empire. Prussia included three-fifths of the German territory and two-thirds of its population. The

The two decades after the unification of Germany were the peak of Prussia's fortunes, but the seeds for potential strife were built into the Prusso-German political system.

The constitution of the German Empire was a version of the North German Confederation's constitution. Officially, the German Empire was a federal state. In practice, Prussia overshadowed the rest of the empire. Prussia included three-fifths of the German territory and two-thirds of its population. The  At age 29, Wilhelm became Kaiser Wilhelm II after a difficult youth and conflicts with his British mother Victoria, Princess Royal. He turned out to be a man of limited experience, narrow and reactionary views, poor judgment, and occasional bad temper, which alienated former friends and allies.

At age 29, Wilhelm became Kaiser Wilhelm II after a difficult youth and conflicts with his British mother Victoria, Princess Royal. He turned out to be a man of limited experience, narrow and reactionary views, poor judgment, and occasional bad temper, which alienated former friends and allies.

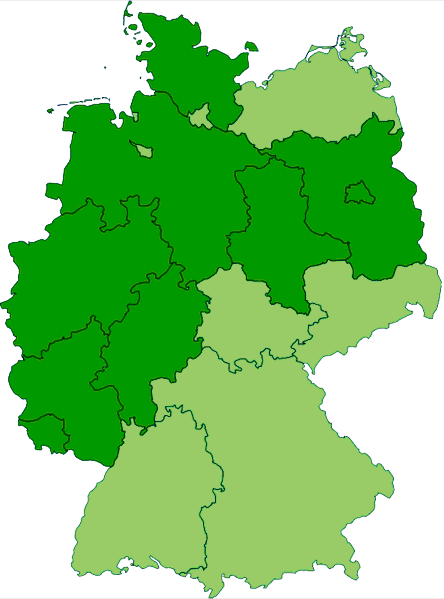

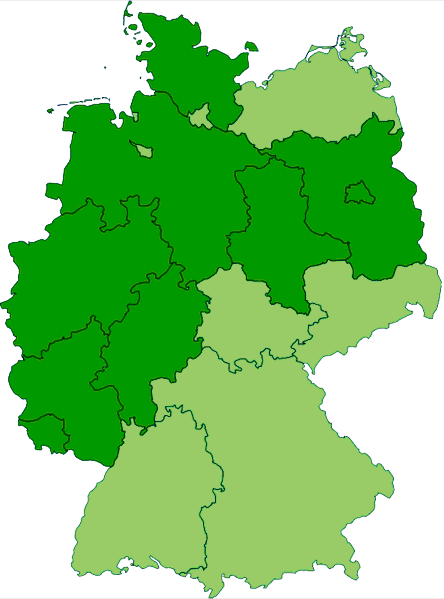

The German government seriously considered breaking up Prussia into smaller states, but eventually traditionalist sentiment prevailed and Prussia became by far the largest state of the Weimar Republic, comprising 60% of its territory. With the abolition of the older Prussian franchise, it became a stronghold of the left. Its incorporation of "Red Berlin" and the industrialised Ruhr Area, both with working-class majorities, ensured left-wing dominance.

From 1919 to 1932, Prussia was governed by a coalition of the Social Democrats, Catholic Centre and German Democrats; from 1921 to 1925, coalition governments included the German People's Party. Unlike in other states of the German Reich, majority rule by democratic parties in Prussia was never endangered. Nevertheless, in

The German government seriously considered breaking up Prussia into smaller states, but eventually traditionalist sentiment prevailed and Prussia became by far the largest state of the Weimar Republic, comprising 60% of its territory. With the abolition of the older Prussian franchise, it became a stronghold of the left. Its incorporation of "Red Berlin" and the industrialised Ruhr Area, both with working-class majorities, ensured left-wing dominance.

From 1919 to 1932, Prussia was governed by a coalition of the Social Democrats, Catholic Centre and German Democrats; from 1921 to 1925, coalition governments included the German People's Party. Unlike in other states of the German Reich, majority rule by democratic parties in Prussia was never endangered. Nevertheless, in

After the appointment of Hitler as the new chancellor, the Nazis used the absence of

After the appointment of Hitler as the new chancellor, the Nazis used the absence of  In the centralised state created by the Nazis in the "Law on the Reconstruction of the Reich" (" Gesetz über den Neuaufbau des Reichs", 30 January 1934) and the " Law on Reich Governors" ("Reichsstatthaltergesetz", 30 January 1935) the states were dissolved, in fact if not in law. The federal state governments were now controlled by governors for the Reich who were appointed by the chancellor. Parallel to that, the organisation of the party into districts ('' Gaue'') gained increasing importance, as the official in charge of a ''Gau'' (the head of which was called a '' Gauleiter'') was again appointed by the chancellor who was at the same time chief of the Nazi Party.

This centralising policy went even further in Prussia. From 1934 to 1945, almost all ministries were merged and only a few departments were able to maintain their independence. Hitler himself became formally the governor of Prussia. However, his functions were exercised by Hermann Göring as Prussian prime minister.

As provided for in the " Greater Hamburg Act" ("Groß-Hamburg-Gesetz"), certain exchanges of territory took place. Prussia was extended on 1 April 1937, for instance, by the incorporation of the Free and Hanseatic City of Lübeck.

The Prussian lands transferred to Poland after the Treaty of Versailles were re-annexed during World War II. However, most of this territory was not reintegrated back into Prussia but assigned to separate ''Gaue'' of

In the centralised state created by the Nazis in the "Law on the Reconstruction of the Reich" (" Gesetz über den Neuaufbau des Reichs", 30 January 1934) and the " Law on Reich Governors" ("Reichsstatthaltergesetz", 30 January 1935) the states were dissolved, in fact if not in law. The federal state governments were now controlled by governors for the Reich who were appointed by the chancellor. Parallel to that, the organisation of the party into districts ('' Gaue'') gained increasing importance, as the official in charge of a ''Gau'' (the head of which was called a '' Gauleiter'') was again appointed by the chancellor who was at the same time chief of the Nazi Party.

This centralising policy went even further in Prussia. From 1934 to 1945, almost all ministries were merged and only a few departments were able to maintain their independence. Hitler himself became formally the governor of Prussia. However, his functions were exercised by Hermann Göring as Prussian prime minister.

As provided for in the " Greater Hamburg Act" ("Groß-Hamburg-Gesetz"), certain exchanges of territory took place. Prussia was extended on 1 April 1937, for instance, by the incorporation of the Free and Hanseatic City of Lübeck.

The Prussian lands transferred to Poland after the Treaty of Versailles were re-annexed during World War II. However, most of this territory was not reintegrated back into Prussia but assigned to separate ''Gaue'' of

The areas east of the Oder-Neisse line, mainly Eastern Prussia, Western Prussia, and Silesia, were ceded over to Poland and the Soviet Union in 1945 owing to the

The areas east of the Oder-Neisse line, mainly Eastern Prussia, Western Prussia, and Silesia, were ceded over to Poland and the Soviet Union in 1945 owing to the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was '' de facto'' dissolved by an emergency decree transferring powers of the Prussian government to German Chancellor Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany i ...

in 1932 and '' de jure'' by an Allied decree in 1947. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, expanding its size with the Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

. Prussia, with its capital at Königsberg and then, when it became the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701, Berlin, decisively shaped the history of Germany

The Germani tribes i.e. Germanic tribes are now considered to be related to the Jastorf culture before expanding and interacting with the other peoples.

The concept of a region for Germanic tribes is traced to time of Julius Caesar, a Roman gene ...

.

In 1871, Prussian Minister-President Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

united most German principalities into the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

under his leadership, although this was considered to be a " Lesser Germany" because Austria and Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

were not included. In November 1918, the monarchies were abolished and the nobility lost its political power during the German Revolution of 1918–19

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

. The Kingdom of Prussia was thus abolished in favour of a republic—the Free State of Prussia, a state of Germany from 1918 until 1933. From 1932, Prussia lost its independence as a result of the Prussian coup and the Nazi ' laws, which established a unitary state. Its legal status finally ended in 1947.Christopher Clark, ''Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947'' (2006) is the standard history.

The name ''Prussia'' derives from the Old Prussians; in the 13th century, the Teutonic Knights—an organized Catholic medieval military order Military order may refer to:

Orders

* Military order (religious society), confraternity of knights originally established as religious societies during the medieval Crusades for protection of Christianity and the Catholic Church

Military organi ...

of German crusaders—conquered the lands inhabited by them. In 1308, the Teutonic Knights conquered the region of Pomerelia with Danzig (modern-day Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

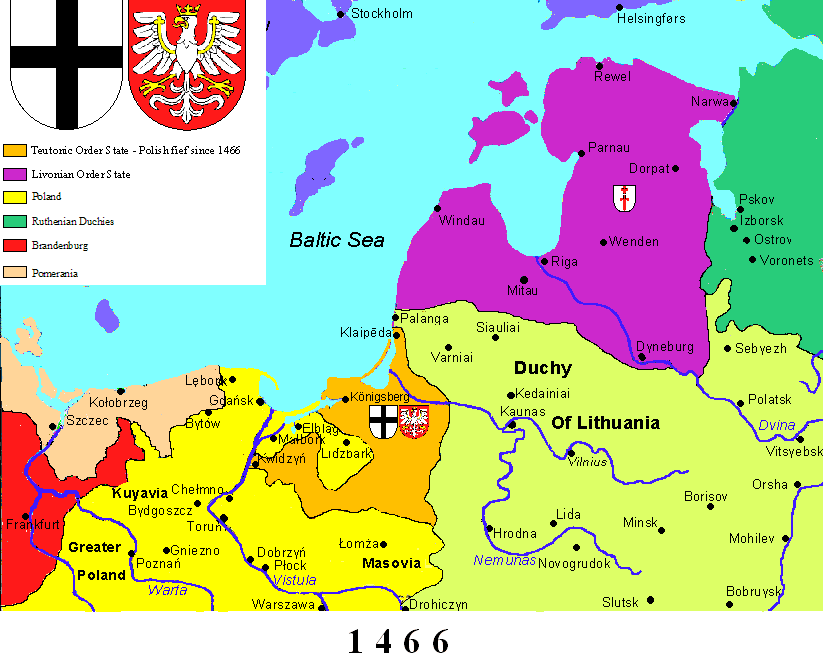

). Their monastic state was mostly Germanised through immigration from central and western Germany, and, in the south, it was Polonised by settlers from Masovia. The imposed Second Peace of Thorn (1466) split Prussia into the western Royal Prussia, becoming a province of Poland, and the eastern part, from 1525 called the Duchy of Prussia, a feudal fief of the Crown of Poland up to 1657. The union of Brandenburg and the Duchy of Prussia in 1618 led to the proclamation of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701.

Prussia entered the ranks of the great powers shortly after becoming a kingdom. It became increasingly large and powerful in the 18th and 19th centuries. It had a major voice in European affairs under the reign of Frederick the Great (1740–1786). At the Congress of Vienna (1814–15), which redrew the map of Europe following Napoleon's defeat, Prussia acquired rich new territories, including the coal-rich Ruhr

The Ruhr ( ; german: Ruhrgebiet , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr area, sometimes Ruhr district, Ruhr region, or Ruhr valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 2,800/km ...

. The country then grew rapidly in influence economically and politically, and became the core of the North German Confederation in 1867, and then of the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

in 1871. The Kingdom of Prussia was now so large and so dominant in the new Germany that and other Prussian élites identified more and more as Germans and less as Prussians.

The Kingdom ended in 1918 along with other German monarchies that were terminated by the German Revolution

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

. In the Weimar Republic, the Free State of Prussia lost nearly all of its legal and political importance following the 1932 coup led by Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany i ...

. Subsequently, it was effectively dismantled into Nazi German '' Gaue'' in 1935. Nevertheless, some Prussian ministries were kept and Hermann Göring remained in his role as Minister President of Prussia until the end of World War II. Former eastern territories of Germany that made up a significant part of Prussia lost the majority of their German population after 1945 as the Polish People's Republic and the Soviet Union both absorbed these territories and had most of its German inhabitants expelled by 1950. Prussia, deemed "a bearer of militarism and reaction" by the Allies, was officially abolished by an Allied declaration in 1947. The international status of the former eastern territories of the Kingdom of Prussia was disputed until the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany in 1990, but its return to Germany remains a cause among far right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

politicians, the Federation of Expellees

The Federation of Expellees (german: link=no, Bund der Vertriebenen; BdV) is a non-profit organization formed in West Germany on 27 October 1957 to represent the interests of German nationals of all ethnicities and foreign ethnic Germans and their ...

and various political revanchists and irredentists.

The terms "Prussian" and "Prussianism

Prussianism comprises the practices and doctrines of the Prussians, specifically the militarism and the severe discipline traditionally associated with the Prussian ruling class.

History

Prussianism had its origins with the rise to the thron ...

" have often been used, especially outside Germany, to denote the militarism, military professionalism, aggressiveness, and conservatism of the class of landed aristocrats in the East who dominated first Prussia and then the German Empire.

Symbols

The main coat of arms of Prussia, as well as the flag of Prussia, depicted a black eagle on a white background. The black and white national colours were already used by the Teutonic Knights and by the Hohenzollern dynasty. The Teutonic Order wore a white coat embroidered with a black cross with gold insert and black imperial eagle. The combination of the black and white colours with the white and red Hanseatic colours of the free citiesBremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state consis ...

, Hamburg and Lübeck, as well as of Brandenburg, resulted in the black-white-red commercial flag of the North German Confederation, which became the flag of the German Empire in 1871.

'' Suum cuique'' ("to each, his own"), the motto of the Order of the Black Eagle created by King Frederick I in 1701, was often associated with the whole of Prussia. The Iron Cross, a military decoration created by King Frederick William III in 1813, was also commonly associated with the country. The region, originally populated by Baltic Old Prussians who were Christianised, became a favoured location for immigration by (later mainly Protestant) Germans (''see Ostsiedlung

(, literally "East-settling") is the term for the Early Medieval and High Medieval migration-period when ethnic Germans moved into the territories in the eastern part of Francia, East Francia, and the Holy Roman Empire (that Germans had al ...

''), as well as Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Ce ...

and Lithuanians

Lithuanians ( lt, lietuviai) are a Baltic ethnic group. They are native to Lithuania, where they number around 2,378,118 people. Another million or two make up the Lithuanian diaspora, largely found in countries such as the United States, Uni ...

along the border regions.

Territory

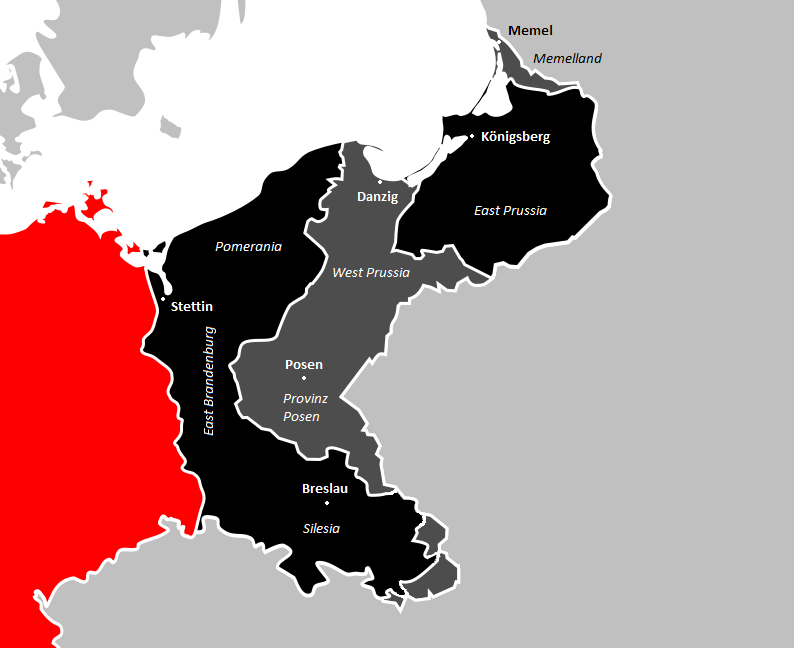

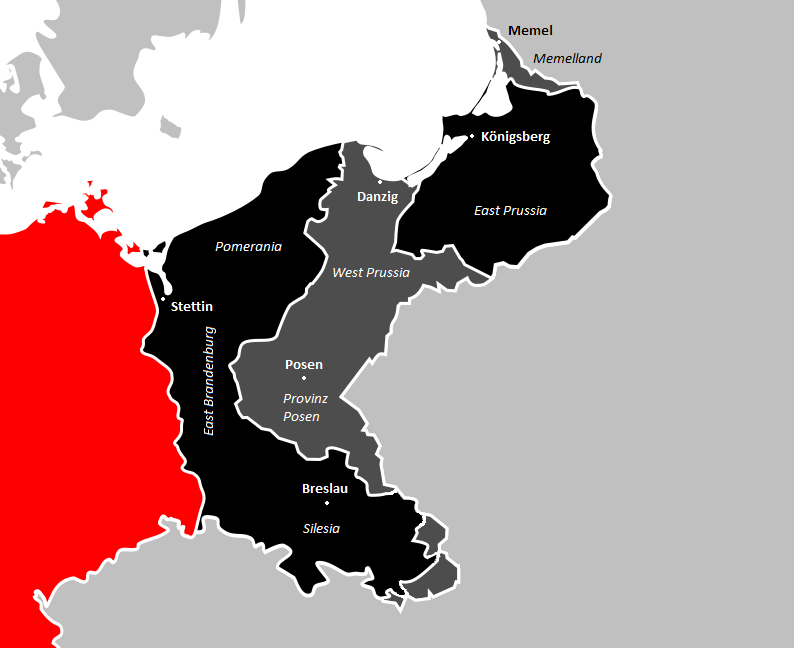

Before its abolition, the territory of the Free State of Prussia included the provinces ofEast Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

; Brandenburg; Saxony (including much of the present-day state of Saxony-Anhalt and parts of the state of Thuringia in Germany); Pomerania; Rhineland; Westphalia; Silesia (without Austrian Silesia); Schleswig-Holstein; Hanover; Hesse-Nassau; and a small detached area in the south called Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenb ...

, the ancestral home of the Prussian ruling family. The land that the Teutonic Knights occupied was flat and covered with fertile soil. The area was perfectly suited to the large-scale raising of wheat. The rise of early Prussia was based on the raising and selling of wheat. Teutonic Prussia became known as the "bread basket of Western Europe" (in German, ''Kornkammer'', or granary). The port cities which rose on the back of this wheat production included: Stettin in Pomerania (now Szczecin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

, Poland); Danzig in Prussia (now Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

, Poland); Riga

Riga (; lv, Rīga , liv, Rīgõ) is the capital and largest city of Latvia and is home to 605,802 inhabitants which is a third of Latvia's population. The city lies on the Gulf of Riga at the mouth of the Daugava river where it meets the Ba ...

in Livonia (now Riga, Latvia); Königsberg in Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia); and Memel in Prussia (now Klaipėda, Lithuania). Wheat production and trade brought Prussia into a close relationship with the Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

during the period of time from 1356 (official founding of the Hanseatic League) until the decline of the League in about 1500.

The expansion of Prussia based on its connection with the Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

cut both Poland and Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

off from the coast of the Baltic Sea and trade abroad. This meant that Poland and Lithuania would be traditional enemies of Prussia, which was still called the Teutonic Knights.

History

Teutonic Order

In 1211 King Andrew II of Hungary granted Burzenland in Transylvania as a fiefdom to the Teutonic Knights, a German

In 1211 King Andrew II of Hungary granted Burzenland in Transylvania as a fiefdom to the Teutonic Knights, a German military order Military order may refer to:

Orders

* Military order (religious society), confraternity of knights originally established as religious societies during the medieval Crusades for protection of Christianity and the Catholic Church

Military organi ...

of crusading knights, headquartered in the Kingdom of Jerusalem at Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

. In 1225 he expelled them, and they transferred their operations to the Baltic Sea area. Konrad I, the Polish duke of Masovia, had unsuccessfully attempted to conquer pagan Prussia in crusades in 1219 and 1222. In 1226 Duke Konrad invited the Teutonic Knights to conquer the Baltic Prussian tribes on his borders.

During 60 years of struggles against the Old Prussians, the Order established an independent state that came to control Prūsa. After the Livonian Brothers of the Sword joined the Teutonic Order in 1237, the Order also controlled Livonia (now Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

and Estonia). Around 1252 they finished the conquest of the northernmost Prussian tribe of the Skalvians as well as of the western Baltic Curonians, and erected Memel Castle, which developed into the major port city of Memel (Klaipėda). The Treaty of Melno defined the final border between Prussia and the adjoining Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1422.

The Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

officially formed in northern Europe in 1356 as a group of trading cities. This League came to hold a monopoly on all trade leaving the interior of Europe and Scandinavia and on all sailing trade in the Baltic Sea for foreign countries.

In the course of the Ostsiedlung

(, literally "East-settling") is the term for the Early Medieval and High Medieval migration-period when ethnic Germans moved into the territories in the eastern part of Francia, East Francia, and the Holy Roman Empire (that Germans had al ...

(German eastward expansion) process, settlers were invited, bringing changes in the ethnic composition as well as in language, culture, and law of the eastern borders of the German lands. As a majority of these settlers were Germans, Low German

:

:

:

:

:

(70,000)

(30,000)

(8,000)

, familycolor = Indo-European

, fam2 = Germanic

, fam3 = West Germanic

, fam4 = North Sea Germanic

, ancestor = Old Saxon

, ancestor2 = Middle L ...

became the dominant language.

The Knights of the Teutonic Order were subordinate to the papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

and to the emperor. Their initially close relationship with the Polish Crown deteriorated after they conquered Polish-controlled Pomerelia and Danzig (Gdańsk) in 1308. Eventually, Poland and Lithuania, allied through the Union of Krewo (1385), defeated the Knights in the Battle of Grunwald (Tannenberg) in 1410.

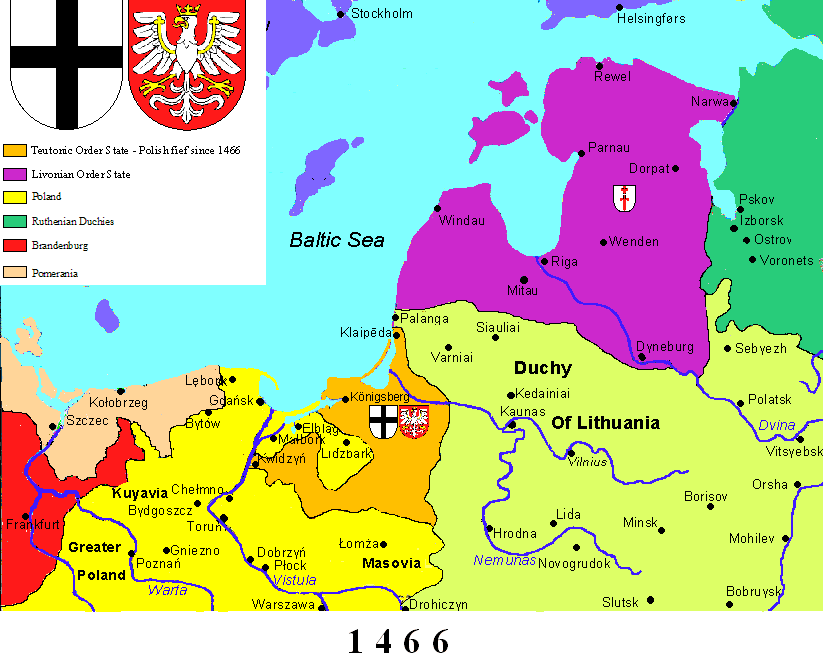

The Thirteen Years' War (1454–1466) began when the Prussian Confederation, a coalition of Hanseatic cities of western Prussia, rebelled against the Order and requested help from the Polish king, Casimir IV Jagiellon. The Teutonic Knights were forced to acknowledge the sovereignty of, and to pay tribute to Casimir IV in the Second Peace of Thorn (1466), losing western Prussia ( Royal Prussia) to Poland in the process. Pursuant to the Second Peace of Thorn, two Prussian states were established.

During the period of the monastic state of the Teutonic Knights, mercenaries from the Holy Roman Empire were granted lands by the Order and gradually formed a new landed Prussian nobility, from which the Junkers

Junkers Flugzeug- und Motorenwerke AG (JFM, earlier JCO or JKO in World War I, English: Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works) more commonly Junkers , was a major German aircraft and aircraft engine manufacturer. It was founded there in Dessau, Germ ...

would evolve to take a major role in the militarization of Prussia and, later, Germany.

Duchy of Prussia

On 10 April 1525, after signing of the Treaty of Kraków, which officially ended the

On 10 April 1525, after signing of the Treaty of Kraków, which officially ended the Polish–Teutonic War (1519–21)

Polish–Teutonic War may refer to:

*Teutonic takeover of Danzig (Gdańsk) (1308–1309)

*Polish–Teutonic War (1326–1332) over Pomerelia, concluded by the Treaty of Kalisz (1343)

*the Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War or ''Great War'' (1409� ...

, in the main square Main Square may refer to:

* Main Square, Plzeň

* Main Square (Bratislava)

* Main Square, Kraków

* Main Square, Maribor

* Main Square Festival, named after the Grand-Place in Arras, France

* Main Square (Toronto), a building complex

See also

* ...

of the Polish capital Kraków, Albert I Albert I may refer to:

People Born before 1300

* Albert I, Count of Vermandois (917–987)

*Albert I, Count of Namur ()

*Albert I of Moha

*Albert I of Brandenburg (), first margrave of Brandenburg

*Albert I, Margrave of Meissen (1158–1195)

*Alber ...

resigned his position as Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights and received the title "Duke of Prussia" from King Zygmunt I the Old of Poland. As a symbol of vassalage, Albert received a standard with the Prussian coat of arms from the Polish king. The black Prussian eagle on the flag was augmented with a letter "S" (for Sigismundus) and had a crown placed around its neck as a symbol of submission to Poland. Albert I, a member of a cadet branch of the House of Hohenzollern became a Lutheran Protestant and secularized the Order's Prussian territories. This was the area east of the mouth of the Vistula River, later sometimes called "Prussia proper". For the first time, these lands came into the hands of a branch of the Hohenzollern family, who already ruled the Margraviate of Brandenburg, since the 15th century. Furthermore, with his renunciation of the Order, Albert could now marry and produce legitimate heirs.

Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg and Prussia united two generations later. In 1594 Anna, granddaughter of Albert I and daughter of Duke Albert Frederick (reigned 1568–1618), married her cousinElector

Elector may refer to:

* Prince-elector or elector, a member of the electoral college of the Holy Roman Empire, having the function of electing the Holy Roman Emperors

* Elector, a member of an electoral college

** Confederate elector, a member of ...

John Sigismund of Brandenburg. When Albert Frederick died in 1618 without male heirs, John Sigismund was granted the right of succession to the Duchy of Prussia, then still a Polish fief. From this time the Duchy of Prussia was in personal union with the Margraviate of Brandenburg. The resulting state, known as Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohenz ...

, consisted of geographically disconnected territories in Prussia, Brandenburg, and the Rhineland lands of Cleves and Mark.

During the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), various armies repeatedly marched across the disconnected Hohenzollern lands, especially the occupying Swedes

Swedes ( sv, svenskar) are a North Germanic ethnic group native to the Nordic region, primarily their nation state of Sweden, who share a common ancestry, culture, history and language. They mostly inhabit Sweden and the other Nordic countr ...

. The ineffective and militarily weak Margrave George William (1619–1640) fled from Berlin to Königsberg, the historic capital of the Duchy of Prussia, in 1637. His successor, Frederick William I (1640–1688), reformed the army to defend the lands.

Frederick William I went to Warsaw in 1641 to render homage

Homage (Old English) or Hommage (French) may refer to:

History

*Homage (feudal) /ˈhɒmɪdʒ/, the medieval oath of allegiance

*Commendation ceremony, medieval homage ceremony Arts

*Homage (arts) /oʊˈmɑʒ/, an allusion or imitation by one arti ...

to King Władysław IV Vasa of Poland for the Duchy of Prussia, which was still held in fief from the Polish crown. In January 1656, during the first phase of the Second Northern War

The Second Northern War (1655–60), (also First or Little Northern War) was fought between Sweden and its adversaries the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1655–60), the Tsardom of Russia (Russo-Swedish War (1656–1658), 1656–58), Brande ...

(1654–1660), he received the duchy as a fief from the Swedish king who later granted him full sovereignty in the Treaty of Labiau (November 1656). In 1657 the Polish king renewed this grant in the treaties of Wehlau and Bromberg

Bydgoszcz ( , , ; german: Bromberg) is a city in northern Poland, straddling the meeting of the River Vistula with its left-bank tributary, the Brda. With a city population of 339,053 as of December 2021 and an urban agglomeration with more ...

. With Prussia, the Brandenburg Hohenzollern dynasty now held a territory free of any feudal obligations, which constituted the basis for their later elevation to kings.

Frederick William I succeeded in organizing the electorate by establishing an absolute monarchy in Brandenburg-Prussia, an achievement for which he became known as the "Great Elector". Above all, he emphasised the importance of a powerful military to protect the state's disconnected territories, while the Edict of Potsdam (1685) opened Brandenburg-Prussia for the immigration of Protestant refugees (especially Huguenots), and he established a bureaucracy to carry out state administration efficiently.

Frederick William I succeeded in organizing the electorate by establishing an absolute monarchy in Brandenburg-Prussia, an achievement for which he became known as the "Great Elector". Above all, he emphasised the importance of a powerful military to protect the state's disconnected territories, while the Edict of Potsdam (1685) opened Brandenburg-Prussia for the immigration of Protestant refugees (especially Huguenots), and he established a bureaucracy to carry out state administration efficiently.

Kingdom of Prussia

On 18 January 1701, Frederick William's son, Elector Frederick III, elevated Prussia from a duchy to a kingdom and crowned himself King Frederick I. In the Crown Treaty of 16 November 1700, Leopold I, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, allowed Frederick only to title himself " King in Prussia", not " King of Prussia". The state of

On 18 January 1701, Frederick William's son, Elector Frederick III, elevated Prussia from a duchy to a kingdom and crowned himself King Frederick I. In the Crown Treaty of 16 November 1700, Leopold I, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, allowed Frederick only to title himself " King in Prussia", not " King of Prussia". The state of Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohenz ...

became commonly known as "Prussia", although most of its territory, in Brandenburg, Pomerania, and western Germany, lay outside Prussia proper. The Prussian state grew in splendour during the reign of Frederick I, who sponsored the arts at the expense of the treasury.

Frederick I was succeeded by his son, Frederick William I (1713–1740), the austere "Soldier King", who did not care for the arts but was thrifty and practical. He was the main creator of the vaunted Prussian bureaucracy and the professionalised standing army, which he developed into one of the most powerful in Europe. His troops only briefly saw action during the Great Northern War. In view of the size of the army in relation to the total population, Mirabeau said later: "Prussia, is not a state with an army, but an army with a state." Frederick William also settled more than 20,000 Protestant refugees from Salzburg in thinly populated eastern Prussia, which was eventually extended to the west bank of the River Memel, and other regions. In the treaty of Stockholm (1720), he acquired half of Swedish Pomerania.

The king died in 1740 and was succeeded by his son, Frederick II, whose accomplishments led to his reputation as "Frederick the Great". As crown prince, Frederick had focused, primarily, on philosophy and the arts. He was an accomplished flute player. In 1740, Prussian troops crossed over the undefended border of Silesia and occupied Schweidnitz. Silesia was the richest province of Habsburg Austria. It signalled the beginning of three Silesian Wars (1740–1763). The First Silesian War (1740–1742) and the

The king died in 1740 and was succeeded by his son, Frederick II, whose accomplishments led to his reputation as "Frederick the Great". As crown prince, Frederick had focused, primarily, on philosophy and the arts. He was an accomplished flute player. In 1740, Prussian troops crossed over the undefended border of Silesia and occupied Schweidnitz. Silesia was the richest province of Habsburg Austria. It signalled the beginning of three Silesian Wars (1740–1763). The First Silesian War (1740–1742) and the Second Silesian War

The Second Silesian War (german: Zweiter Schlesischer Krieg, links=no) was a war between Prussia and Austria that lasted from 1744 to 1745 and confirmed Prussia's control of the region of Silesia (now in south-western Poland). The war was fough ...

(1744–1745) have, historically, been grouped together with the general European war called the War of Austrian Succession (1740–1748). Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

Charles VI had died on 20 October 1740. He was succeeded to the throne by his daughter, Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position ''suo jure'' (in her own right). ...

.

By defeating the Austrian Army at the Battle of Mollwitz on 10 April 1741, Frederick succeeded in conquering Lower Silesia (the northwestern half of Silesia). In the next year, 1742, he conquered Upper Silesia (the southeastern half). Furthermore, in the third Silesian War (usually grouped with the Seven Years' War) Frederick won a victory over Austria at the Battle of Lobositz on 1 October 1756. In spite of some impressive victories afterward, his situation became far less comfortable the following years, as he failed in his attempts to knock Austria out of the war and was gradually reduced to a desperate defensive war. However, he never gave up and on 3 November 1760 the Prussian king won another battle, the hard-fought Battle of Torgau. Despite being several times on the verge of defeat Frederick, allied with Great Britain, Hanover and Hesse-Kassel, was finally able to hold the whole of Silesia against a coalition of Saxony, the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

, France and Russia. Voltaire, a close friend of the king, once described Frederick the Great's Prussia by saying "...it was Sparta in the morning, Athens in the afternoon."

Silesia, full of rich soils and prosperous manufacturing towns, became a vital region to Prussia, greatly increasing the nation's area, population, and wealth. Success on the battleground against Austria and other powers proved Prussia's status as one of the great powers of Europe. The Silesian Wars began more than a century of rivalry and conflict between Prussia and Austria as the two most powerful states operating within the Holy Roman Empire (although both had extensive territory outside the empire). In 1744, the County of East Frisia

East Frisia or East Friesland (german: Ostfriesland; ; stq, Aastfräislound) is a historic region in the northwest of Lower Saxony, Germany. It is primarily located on the western half of the East Frisian peninsula, to the east of West Frisia ...

fell to Prussia following the extinction of its ruling Cirksena dynasty.

In the last 23 years of his reign until 1786, Frederick II, who understood himself as the "first servant of the state", promoted the development of Prussian areas such as the Oderbruch. At the same time he built up Prussia's military power and participated in the First Partition of Poland with Austria and Russia in 1772, an act that geographically connected the Brandenburg territories with those of Prussia proper. During this period, he also opened Prussia's borders to immigrants fleeing from religious persecution in other parts of Europe, such as the Huguenots. Prussia became a safe haven in much the same way that the United States welcomed immigrants seeking freedom in the 19th century.Clark, ''Iron Kingdom'' ch 7

Frederick the Great (reigned 1740–1786) practised enlightened absolutism

Enlightened absolutism (also called enlightened despotism) refers to the conduct and policies of European absolute monarchs during the 18th and early 19th centuries who were influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment, espousing them to enhance ...

. He built the world's best army, and usually won his many wars. He introduced a general civil code, abolished torture and established the principle that the Crown would not interfere in matters of justice. He also promoted an advanced secondary education, the forerunner of today's German gymnasium (grammar school) system, which prepares the brightest pupils for university studies. The Prussian education system was emulated in various countries, including the United States.

Napoleonic Wars

During the reign of King Frederick William II (1786–1797), Prussia annexed additional Polish territory through the Second Partition of Poland in 1793 and the Third Partition of Poland in 1795. His successor, Frederick William III (1797–1840), announced the union of the Prussian Lutheran and Reformed churches into

During the reign of King Frederick William II (1786–1797), Prussia annexed additional Polish territory through the Second Partition of Poland in 1793 and the Third Partition of Poland in 1795. His successor, Frederick William III (1797–1840), announced the union of the Prussian Lutheran and Reformed churches into one church

1 (one, unit, unity) is a number representing a single or the only entity. 1 is also a numerical digit and represents a single unit of counting or measurement. For example, a line segment of ''unit length'' is a line segment of length 1. ...

.Clark, ''Iron Kingdom'' ch 12

Prussia took a leading part in the French Revolutionary Wars, but remained quiet for more than a decade because of the Peace of Basel of 1795, only to go once more to war with France in 1806 as negotiations with that country over the allocation of the spheres of influence in Germany failed. Prussia suffered a devastating defeat against

Prussia took a leading part in the French Revolutionary Wars, but remained quiet for more than a decade because of the Peace of Basel of 1795, only to go once more to war with France in 1806 as negotiations with that country over the allocation of the spheres of influence in Germany failed. Prussia suffered a devastating defeat against Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's troops in the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt, leading Frederick William III and his family to flee temporarily to Memel. Under the Treaties of Tilsit in 1807, the state lost about one-third of its area, including the areas gained from the second and third Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

, which now fell to the Duchy of Warsaw. Beyond that, the king was obliged to pay a large indemnity, to cap his army at 42,000 men, and to let the French garrison troops throughout Prussia, effectively making the Kingdom a French satellite.Clark, ''Iron Kingdom'' ch 11

In response to this defeat, reformers such as Stein and Hardenberg set about modernising the Prussian state. Among their reforms were the liberation of peasants from serfdom, the Emancipation of Jews and making full citizens of them. The school system was rearranged, and in 1818 free trade was introduced. The process of army reform ended in 1813 with the introduction of compulsory military service for men. By 1813, Prussia could mobilize almost 300,000 soldiers, more than half of which were conscripts of the ''Landwehr'' of variable quality. The rest consisted of regular soldiers that were deemed excellent by most observers, and very determined to repair the humiliation of 1806.

After the defeat of Napoleon in Russia, Prussia quit its alliance with France and took part in the Sixth Coalition during the "Wars of Liberation" (''Befreiungskriege'') against the French occupation. Prussian troops under Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher contributed crucially (alongside the British and Dutch) to the final victory over Napoleon in the Battle of Waterloo of June 1815. Prussia's reward in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna was the recovery of her lost territories, as well as the whole of the Rhineland, Westphalia, 40% of Saxony and some other territories. These western lands were of vital importance because they included the Ruhr Area, the centre of Germany's fledgling industrialisation, especially in the arms industry. These territorial gains also meant the doubling of Prussia's population. In exchange, Prussia withdrew from areas of central Poland to allow the creation of Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

under Russian sovereignty. In 1815 Prussia became part of the German Confederation.

Wars of liberation

The first half of the 19th century saw a prolonged struggle in Germany between liberals, who wanted a united, federal Germany under a democratic constitution, and conservatives, who wanted to maintain Germany as a patchwork of independent, monarchical states with Prussia and Austria competing for influence. One small movement that signalled a desire for German unification in this period was the Burschenschaft student movement, by students who encouraged the use of the black-red-gold flag, discussions of a unified German nation, and a progressive, liberal political system. Because of Prussia's size and economic importance, smaller states began to join its free trade area in the 1820s. Prussia benefited greatly from the creation in 1834 of the German Customs Union ( Zollverein), which included most German states but excluded Austria.

In 1848 the liberals saw an opportunity when revolutions broke out across Europe. Alarmed, King Frederick William IV agreed to convene a National Assembly and grant a constitution. When the Frankfurt Parliament offered Frederick William the crown of a united Germany, he refused on the grounds that he would not accept a crown from a revolutionary assembly without the sanction of Germany's other monarchs.

The Frankfurt Parliament was forced to dissolve in 1849, and Frederick William issued Prussia's first constitution by his own authority in 1850. This conservative document provided for a two-house parliament. The lower house, or '' Landtag'' was elected by all taxpayers, who were divided into three classes whose votes were weighted according to the amount of taxes paid. Women and those who paid no taxes had no vote. This allowed just over one-third of the voters to choose 85% of the legislature, all but assuring dominance by the more well-to-do men of the population. The upper house, which was later renamed the '' Herrenhaus'' ("House of Lords"), was appointed by the king. He retained full executive authority and ministers were responsible only to him. As a result, the grip of the landowning classes, the Junkers, remained unbroken, especially in the eastern provinces.

The first half of the 19th century saw a prolonged struggle in Germany between liberals, who wanted a united, federal Germany under a democratic constitution, and conservatives, who wanted to maintain Germany as a patchwork of independent, monarchical states with Prussia and Austria competing for influence. One small movement that signalled a desire for German unification in this period was the Burschenschaft student movement, by students who encouraged the use of the black-red-gold flag, discussions of a unified German nation, and a progressive, liberal political system. Because of Prussia's size and economic importance, smaller states began to join its free trade area in the 1820s. Prussia benefited greatly from the creation in 1834 of the German Customs Union ( Zollverein), which included most German states but excluded Austria.

In 1848 the liberals saw an opportunity when revolutions broke out across Europe. Alarmed, King Frederick William IV agreed to convene a National Assembly and grant a constitution. When the Frankfurt Parliament offered Frederick William the crown of a united Germany, he refused on the grounds that he would not accept a crown from a revolutionary assembly without the sanction of Germany's other monarchs.

The Frankfurt Parliament was forced to dissolve in 1849, and Frederick William issued Prussia's first constitution by his own authority in 1850. This conservative document provided for a two-house parliament. The lower house, or '' Landtag'' was elected by all taxpayers, who were divided into three classes whose votes were weighted according to the amount of taxes paid. Women and those who paid no taxes had no vote. This allowed just over one-third of the voters to choose 85% of the legislature, all but assuring dominance by the more well-to-do men of the population. The upper house, which was later renamed the '' Herrenhaus'' ("House of Lords"), was appointed by the king. He retained full executive authority and ministers were responsible only to him. As a result, the grip of the landowning classes, the Junkers, remained unbroken, especially in the eastern provinces.

Wars of unification

In 1862 King Wilhelm I appointed

In 1862 King Wilhelm I appointed Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

as Prime Minister of Prussia. Bismarck was determined to defeat both the liberals and conservatives and increase Prussian supremacy and influence among the German states. There has been much debate as to whether Bismarck actually planned to create a united Germany when he set out on this journey, or whether he simply took advantage of the circumstances that fell into place. Bismarck curried support from large sections of the people by promising to lead the fight for greater German unification. He successfully guided Prussia through three wars, which unified Germany and brought William the position of German Emperor.

=Schleswig Wars

= The Kingdom of Denmark was at the time in personal union with the Duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, both of which had close ties with each other, although only Holstein was part of the German Confederation. When the Danish government tried to integrate Schleswig, but not Holstein, into the Danish state, Prussia led the German Confederation against Denmark in theFirst War of Schleswig

The First Schleswig War (german: Schleswig-Holsteinischer Krieg) was a military conflict in southern Denmark and northern Germany rooted in the Schleswig-Holstein Question, contesting the issue of who should control the Duchies of Schleswig, ...

(1848–1851). Because Russia supported Austria, Prussia also conceded predominance in the German Confederation to Austria in the Punctation of Olmütz in 1850.

In 1863, Denmark introduced a shared constitution for Denmark and Schleswig. This led to conflict with the German Confederation, which authorised the occupation of Holstein by the Confederation, from which Danish forces withdrew. In 1864, Prussian and Austrian forces crossed the border between Holstein and Schleswig initiating the Second War of Schleswig

The Second Schleswig War ( da, Krigen i 1864; german: Deutsch-Dänischer Krieg) also sometimes known as the Dano-Prussian War or Prusso-Danish War was the second military conflict over the Schleswig-Holstein Question of the nineteenth century. T ...

. The Austro-Prussian forces defeated the Danes, who surrendered both territories. In the resulting Gastein Convention of 1865 Prussia took over the administration of Schleswig while Austria assumed that of Holstein.

=Austro-Prussian War

= Bismarck realised that the dual administration of Schleswig and Holstein was only a temporary solution, and tensions rose between Prussia and Austria. The struggle for supremacy in Germany then led to the

Bismarck realised that the dual administration of Schleswig and Holstein was only a temporary solution, and tensions rose between Prussia and Austria. The struggle for supremacy in Germany then led to the Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War, also by many variant names such as Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), (; "German war of brothers") and by a variety of other names, was fought in 186 ...

(1866), triggered by the dispute over Schleswig and Holstein, with Bismarck using proposed injustices as the reason for war.

On the Austrian side stood the south German states (including Bavaria and Württemberg), some central German states (including Saxony), and Hanover in the north. On the side of Prussia were Italy, most north German states, and some smaller central German states. Eventually, the better-armed Prussian troops won the crucial victory at the Battle of Königgrätz under Helmuth von Moltke the Elder Helmuth is both a masculine German given name and a surname. Notable people with the name include:

Given name;

*Helmuth Theodor Bossert (1889–1961), German art historian, philologist and archaeologist

*Helmuth Duckadam (born 1959), Romanian forme ...

. The century-long struggle between Berlin and Vienna for the dominance of Germany was now over. As a sideshow in this war, Prussia defeated Hanover in the Battle of Langensalza (1866). While Hanover hoped in vain for help from Britain (as they had previously been in personal union), Britain stayed out of a confrontation with a continental great power and Prussia satisfied its desire for merging the once separate territories and gaining strong economic and strategic power, particularly from the full access to the resources of the Ruhr.

Bismarck desired Austria as an ally in the future, and so he declined to annex any Austrian territory. But in the Peace of Prague in 1866, Prussia annexed four of Austria's allies in northern and central Germany— Hanover, Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel), Nassau and Frankfurt. Prussia also won full control of Schleswig-Holstein. As a result of these territorial gains, Prussia now stretched uninterrupted across the northern two-thirds of Germany and contained two-thirds of Germany's population. The German Confederation was dissolved, and Prussia impelled the 21 states north of the Main River into forming the North German Confederation.

Prussia was the dominant state in the new confederation, as the kingdom comprised almost four-fifths of the new state's territory and population. Prussia's near-total control over the confederation was secured in the constitution drafted for it by Bismarck in 1867. Executive power was held by a president, assisted by a chancellor responsible only to him. The presidency was a hereditary office of the Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenb ...

rulers of Prussia. There was also a two-house parliament. The lower house, or '' Reichstag'' (Diet), was elected by universal male suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

. The upper house, or ''Bundesrat'' (Federal Council) was appointed by the state governments. The Bundesrat was, in practice, the stronger chamber. Prussia had 17 of 43 votes, and could easily control proceedings through alliances with the other states.

As a result of the peace negotiations, the states south of the Main remained theoretically independent, but received the (compulsory) protection of Prussia. Additionally, mutual defence treaties were concluded. However, the existence of these treaties was kept secret until Bismarck made them public in 1867 when France tried to acquire Luxembourg.

=Franco-Prussian War

=Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenb ...

to the Spanish throne was escalated both by France and Bismarck. With his Ems Dispatch, Bismarck took advantage of an incident in which the French ambassador had approached William. The government of Napoleon III, expecting another civil war among the German states, declared war against Prussia, continuing Franco-German enmity. However, honouring their treaties, the German states joined forces and quickly defeated France in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. Following victory under Bismarck's and Prussia's leadership, Baden, Württemberg and Bavaria, which had remained outside the North German Confederation, accepted incorporation into a united German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

.

The empire was a "Lesser German" solution (in German, " kleindeutsche Lösung") to the question of uniting all German-speaking peoples into one state, because it excluded Austria, which remained connected to Hungary and whose territories included non-German populations. On 18 January 1871 (the 170th anniversary of the coronation of King Frederick I), William was proclaimed "German Emperor" (not "Emperor of Germany") in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles outside Paris, while the French capital was still under siege.

German Empire

The two decades after the unification of Germany were the peak of Prussia's fortunes, but the seeds for potential strife were built into the Prusso-German political system.

The constitution of the German Empire was a version of the North German Confederation's constitution. Officially, the German Empire was a federal state. In practice, Prussia overshadowed the rest of the empire. Prussia included three-fifths of the German territory and two-thirds of its population. The

The two decades after the unification of Germany were the peak of Prussia's fortunes, but the seeds for potential strife were built into the Prusso-German political system.

The constitution of the German Empire was a version of the North German Confederation's constitution. Officially, the German Empire was a federal state. In practice, Prussia overshadowed the rest of the empire. Prussia included three-fifths of the German territory and two-thirds of its population. The Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (german: Deutsches Heer), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the l ...

was, in practice, an enlarged Prussian army, although the other kingdoms (Bavaria, Saxony and Württemberg) retained their own small armies. There was at first no navy. The imperial crown was a hereditary office of the House of Hohenzollern, the royal house of Prussia. The prime minister of Prussia was, except for two brief periods (January–November 1873 and 1892–94), also imperial chancellor. But the empire itself had no right to collect taxes directly from its subjects; the only incomes fully under federal control were the customs duties, common excise duties, and the revenue from postal and telegraph services. While all men above age 25 were eligible to vote in imperial elections, Prussia retained its restrictive three-class voting system. This effectively required the king/emperor and prime minister/chancellor to seek majorities from legislatures elected by two different franchises. In both the kingdom and the empire, the original constituencies were never redrawn to reflect changes in population, meaning that rural areas were grossly overrepresented by the turn of the 20th century.

As a result, Prussia and the German Empire were something of a paradox. Bismarck knew that his new German Reich was now a colossus and economically and militarily dominant in Europe; Britain was still dominant in finance and trade. He declared Germany a "satisfied" power, using his talents to preserve peace, for example at the Congress of Berlin. Bismarck did not set up his own party. He had mixed success in some of his domestic policies. His anti-Catholic ''Kulturkampf

(, 'culture struggle') was the conflict that took place from 1872 to 1878 between the Catholic Church led by Pope Pius IX and the government of Prussia led by Otto von Bismarck. The main issues were clerical control of education and ecclesiastic ...

'' inside Prussia (and not the wider German state) was a failure. He ended his support for the anticlerical Liberals and worked instead with the Catholic Centre Party. He tried to destroy the socialist movement, with limited success. The large Polish population resisted Germanisation

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, German people, people and German culture, culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationa ...

.

Frederick III became emperor in March 1888, after the death of his father, but he died of cancer only 99 days later.  At age 29, Wilhelm became Kaiser Wilhelm II after a difficult youth and conflicts with his British mother Victoria, Princess Royal. He turned out to be a man of limited experience, narrow and reactionary views, poor judgment, and occasional bad temper, which alienated former friends and allies.

At age 29, Wilhelm became Kaiser Wilhelm II after a difficult youth and conflicts with his British mother Victoria, Princess Royal. He turned out to be a man of limited experience, narrow and reactionary views, poor judgment, and occasional bad temper, which alienated former friends and allies.

Railways

Prussia nationalised its railways in the 1880s in an effort both to lower rates on freight service and to equalise those rates among shippers. Instead of lowering rates as far as possible, the government ran the railways as a profit-making endeavour, and the railway profits became a major source of revenue for the state. The nationalisation of the railways slowed the economic development of Prussia because the state favoured the relatively backward agricultural areas in its railway building. Moreover, the railway surpluses substituted for the development of an adequate tax system.The Free State of Prussia in the Weimar Republic

Because of theGerman Revolution

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

of 1918, Wilhelm II abdicated as German Emperor and King of Prussia. Prussia was proclaimed a "Free State" (i.e. a republic, German: ''Freistaat'') within the new Weimar Republic and in 1920 received a democratic constitution.

Almost all of Germany's territorial losses, specified in the Treaty of Versailles, were areas that had been part of Prussia: Eupen and Malmedy to Belgium; North Schleswig to Denmark; the Memel Territory to Lithuania; the Hultschin area to Czechoslovakia. Many of the areas Prussia annexed in the partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

, such as the Provinces of Posen and West Prussia, as well as eastern Upper Silesia, went to the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of ...

. Danzig became the Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (german: Freie Stadt Danzig; pl, Wolne Miasto Gdańsk; csb, Wòlny Gard Gduńsk) was a city-state under the protection of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gda ...

under the administration of the League of Nations. Also, the Saargebiet

The Territory of the Saar Basin (german: Saarbeckengebiet, ; french: Territoire du bassin de la Sarre) was a region of Germany occupied and governed by the United Kingdom and France from 1920 to 1935 under a League of Nations mandate. It had its ...

was created mainly from formerly Prussian territories except present Saarpfalz district was part of Kingdom of Bavaria. East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

became an exclave, only reachable by ship (the Sea Service East Prussia) or by a railway through the Polish corridor.

East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

and some rural areas, the Nazi Party of Adolf Hitler gained more and more influence and popular support, especially from the lower middle class starting in 1930. Except for Catholic Upper Silesia, the Nazi Party in 1932 became the largest party in most parts of the Free State of Prussia. However, the democratic parties in coalition remained a majority, while Communists and Nazis were in the opposition.

The East Prussian Otto Braun, who was Prussian minister-president almost continuously from 1920 to 1932, is considered one of the most capable Social Democrats in history. He implemented several trend-setting reforms together with his minister of the interior, Carl Severing

Carl Wilhelm Severing (1 June 1875, Herford, Westphalia – 23 July 1952, Bielefeld) was a German Social Democrat politician during the Weimar era.

He was seen as a representative of the right wing of the party. Over the years, he took a leadi ...

, which were also models for the later Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). For instance, a Prussian minister-president could be forced out of office only if there was a "positive majority" for a potential successor. This concept, known as the constructive vote of no confidence, was carried over into the Basic Law of the FRG. Most historians regard the Prussian government during this time as far more successful than that of Germany as a whole.

In contrast to its pre-war authoritarianism, Prussia was a pillar of democracy in the Weimar Republic. This system was destroyed by the '' Preußenschlag'' ("Prussian coup") of Reich Chancellor Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany i ...

. In this coup d'état, the government of the Reich deposed the Prussian government on 20 July 1932, under the pretext that the latter had lost control of public order in Prussia (during the Bloody Sunday of Altona, Hamburg

Altona (), also called Hamburg-Altona, is the westernmost urban borough (''Bezirk'') of the German city state of Hamburg, on the right bank of the Elbe river. From 1640 to 1864, Altona was under the administration of the Danish monarchy. Alto ...

, which was still part of Prussia at that time) and by using fabricated evidence that the Social Democrats and the Communists were planning a joint ''putsch''. The Defence Minister General Kurt von Schleicher, who was the prime mover behind the coup manufactured evidence that the Prussian police under Braun's orders were favouring the Communist '' Rotfrontkämpferbund'' in street clashes with the SA as part of an alleged plan to foment a Marxist revolution, which he used to get an emergency decree from President Paul von Hindenburg imposing ''Reich'' control on Prussia. Papen appointed himself Reich commissioner for Prussia and took control of the government. The ''Preußenschlag'' made it easier, only half a year later, for Hitler to take power decisively in Germany, since he had the whole apparatus of the Prussian government, including the police, at his disposal.

Prussia and the Third Reich

After the appointment of Hitler as the new chancellor, the Nazis used the absence of

After the appointment of Hitler as the new chancellor, the Nazis used the absence of Franz von Papen