Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Principal Chief is today the title of the chief executives of the

''University of Oklahoma Law Center.'' (retrieved January 16, 2010) In 1999, they approved several changes to the constitution, including the removal of the qualifying phrase "of Oklahoma" from their name, leaving it simply "Cherokee Nation".

Before 1794, the Cherokee had no standing national government. Their structure was based on clans and towns, which had various leaders. The clans had functions within each town and within the tribe. The towns appointed their own leaders to represent the tribe to British, French, and (later) American authorities. They typically had both peace ("white") and war ("red") chiefs. The range of aboriginal titles were usually translated by the English as "chief," but the Cherokee called their headmen of towns and villages "''Beloved Man''." The term "emperor" is placed in quotation marks, since this title was created by British emissary Sir Alexander Cuming; it was not accepted by the tribe as a whole.Conley 16

* Outacite (d. 1729), peace chief, signed a 1720 treaty with Governor Nicholson; ''outacite'' is his title rather than his given name

* Charitey Hagey of

Before 1794, the Cherokee had no standing national government. Their structure was based on clans and towns, which had various leaders. The clans had functions within each town and within the tribe. The towns appointed their own leaders to represent the tribe to British, French, and (later) American authorities. They typically had both peace ("white") and war ("red") chiefs. The range of aboriginal titles were usually translated by the English as "chief," but the Cherokee called their headmen of towns and villages "''Beloved Man''." The term "emperor" is placed in quotation marks, since this title was created by British emissary Sir Alexander Cuming; it was not accepted by the tribe as a whole.Conley 16

* Outacite (d. 1729), peace chief, signed a 1720 treaty with Governor Nicholson; ''outacite'' is his title rather than his given name

* Charitey Hagey of

"Eastern Cherokee Chiefs."

''Chronicles of Oklahoma.'' Vol. 16, No. 1. March 1938. Retrieved January 1, 2013. * Uka Ulah (also Ukah Ulah) (d. 1761), "emperor;" nephew of Old Hop, * Standing Turkey (or Cunne Shote), traveled to England in 1762 with

Little Turkey was elected First Beloved Man of the Cherokee (the council seat of which was shifted south to Ustanali (later known as New Echota), near what is now

Little Turkey was elected First Beloved Man of the Cherokee (the council seat of which was shifted south to Ustanali (later known as New Echota), near what is now

The

The

Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ''Tsalagihi Ayeli'' or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ ''Tsalagiyehli''), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It ...

, of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI), (Cherokee language, Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᏱ ᏕᏣᏓᏂᎸᎩ, ''Tsalagiyi Detsadanilvgi'') is a Federally recognized tribe, federally recognized Indian Tribe based in Western North Carolina in the U ...

, and of the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians

The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma ( or , abbreviated United Keetoowah Band or UKB) is a federally recognized tribe of Cherokee Native Americans headquartered in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. According to the UKB website, its member ...

, the three federally recognized tribes

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United ...

of Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

. In the eighteenth century, when the people were primarily organized by clans and towns, they would appoint a leader for negotiations with the Europeans. They called him ''Uku'', or "First Beloved Man".

The title of "Principal Chief" was created in 1794, when the Cherokee began to formalize a more centralized political structure. They founded the original Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ''Tsalagihi Ayeli'' or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ ''Tsalagiyehli''), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It ...

. The Cherokee Nation–East adopted a written constitution in 1827, creating a government with three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. The Principal Chief was elected by the National Council, which was the legislature of the Nation. The Cherokee Nation–West adopted a similar constitution in 1833. In 1839 most of the reunited nation was reunited in Indian Territory, after forced removal from the Southeast. There they adopted one constitution. In 1868, the Eastern Band of Cherokee, made up of those who had managed to remain primarily in the homelands of North Carolina, created a separate and distinct constitution and formalized the position of Principal Chief. The position had existed in the east since the time of ''Yonaguska

Yonaguska, (1759–1839), who was known as Drowning Bear (the English meaning of his name), was a leader among the Cherokee of the Lower Towns of North Carolina.

During the Indian Removal of the late 1830s, he was the only chief who remained in ...

''. Their descendants make up the members of the federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI), (Cherokee language, Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᏱ ᏕᏣᏓᏂᎸᎩ, ''Tsalagiyi Detsadanilvgi'') is a Federally recognized tribe, federally recognized Indian Tribe based in Western North Carolina in the U ...

today, referred to as the EBCI.

In 1906, the US government dismantled the Cherokee Nation's governmental structure under the Dawes Act

The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887) regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the Pre ...

(except for allowing the tribe to retain limited authority to deal with remaining land issues, a provision that lasted until June 1914). This act also provided for the allotment of communal lands and extinguishing of Cherokee land title in preparation for admission of Oklahoma as a state in 1907.Conley, p. 198 Following passage of the federal Indian Reorganization Act

The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of June 18, 1934, or the Wheeler–Howard Act, was U.S. federal legislation that dealt with the status of American Indians in the United States. It was the centerpiece of what has been often called the "Indian ...

of 1934 and the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act

The Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936 (also known as the Thomas-Rogers Act) is a United States federal law that extended the 1934 Wheeler-Howard or Indian Reorganization Act to include those tribes within the boundaries of the state of Oklahoma. ...

of 1936, the Keetoowah Nighthawk Society

The Keetoowah Nighthawk Society was a Cherokee organisation formed ''ca.'' 1900 that intended to preserve and practice traditional "old ways" of tribal life, based on religious nationalism. It was led by Redbird Smith, a Cherokee National Council ...

organized in 1939 as the United Keetoowah Band. The Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and A ...

approved their constitution in 1940.

The United States President began appointing a Principal Chief for the non-UKB Cherokee in 1941. In 1975, these Cherokee drafted their constitution as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, which was ratified on June 26, 1976."Constitution of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma."''University of Oklahoma Law Center.'' (retrieved January 16, 2010) In 1999, they approved several changes to the constitution, including the removal of the qualifying phrase "of Oklahoma" from their name, leaving it simply "Cherokee Nation".

Early leaders

Before 1794, the Cherokee had no standing national government. Their structure was based on clans and towns, which had various leaders. The clans had functions within each town and within the tribe. The towns appointed their own leaders to represent the tribe to British, French, and (later) American authorities. They typically had both peace ("white") and war ("red") chiefs. The range of aboriginal titles were usually translated by the English as "chief," but the Cherokee called their headmen of towns and villages "''Beloved Man''." The term "emperor" is placed in quotation marks, since this title was created by British emissary Sir Alexander Cuming; it was not accepted by the tribe as a whole.Conley 16

* Outacite (d. 1729), peace chief, signed a 1720 treaty with Governor Nicholson; ''outacite'' is his title rather than his given name

* Charitey Hagey of

Before 1794, the Cherokee had no standing national government. Their structure was based on clans and towns, which had various leaders. The clans had functions within each town and within the tribe. The towns appointed their own leaders to represent the tribe to British, French, and (later) American authorities. They typically had both peace ("white") and war ("red") chiefs. The range of aboriginal titles were usually translated by the English as "chief," but the Cherokee called their headmen of towns and villages "''Beloved Man''." The term "emperor" is placed in quotation marks, since this title was created by British emissary Sir Alexander Cuming; it was not accepted by the tribe as a whole.Conley 16

* Outacite (d. 1729), peace chief, signed a 1720 treaty with Governor Nicholson; ''outacite'' is his title rather than his given name

* Charitey Hagey of Tugaloo

Tugaloo (''Dugiluyi'' (ᏚᎩᎷᏱ)) was a Cherokee town located on the Tugaloo River, at the mouth of Toccoa Creek. It was south of Toccoa and Travelers Rest State Historic Site in present-day Stephens County, Georgia. Cultures of ancient ind ...

(1716–1721)

* Long Warrior of Tanasi

Tanasi ( chr, ᏔᎾᏏ, translit=Tanasi) (also spelled Tanase, Tenasi, Tenassee, Tunissee, Tennessee, and other such variations) was a historic Overhill settlement site in present-day Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. ...

(1729–1730)

* Wrosetasetow, "emperor" of the Cherokee until 1730; his given name was ''Ama-edohi'' or "water-goer",Conley 17 and he served as a trade commissioner

* Moytoy of Tellico

Moytoy of Tellico, (died 1741) was a prominent leader of the Cherokee in the American Southeast.

Titles

Moytoy was given the title of "Emperor of the Cherokee" by Sir Alexander Cumming, a Scots-Anglo trade envoy in what was then the Province of ...

(also known as Ama-edohi); (d. 1741),Conley 18 declared "emperor" by British emissary, Alexander Cuming, from 1730Timberlake and King xvii until 1741Conley 57

* Attakullakulla

Attakullakulla (Cherokee language, Cherokee”Tsalagi”, (ᎠᏔᎫᎧᎷ) ''Atagukalu''; also spelled Attacullaculla and often called Little Carpenter by the English) (c. 1715 – c. 1777) was an influential Cherokee leader and the tr ...

(or "Little Carpenter", also spelled Ada-gal'kala, Attacullaculla, Oukou-naka) (1708/1711–1780Fowler xiii), "white" peace chief from Echota

Chota (also spelled Chote, Echota, Itsati, and other similar variations) is a historic Overhill Cherokee town site in Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. Developing after nearby Tanasi, Chota ( chr, ᎢᏣᏘ, translit=Its ...

recognized as primary chief by the British, or "president of the nation" from 1762 to 1778

* Amouskositte

Amouskositte, or Amo-sgiasite, Prince of Chota ("Dreadful Water"), of Great Tellico was the son of Moytoy of Tellico and attempted to succeed him as "Emperor of the Cherokee", a title given his father by Alexander Cuming. Few Cherokee recogniz ...

(or Ammouskossittee, Amascossite, Ammonscossittee, Amosgasite, "Dreadfulwater") of Great Tellico (b. ca. 1728), served as "emperor" 1741–1753, son of Moytoy

* Old Hop

Conocotocko of Chota ( chr, ᎬᎾᎦᏙᎦ, Gvnagadoga, "Standing Turkey"), known in English as Old Hop, was a Cherokee elder, serving as the First Beloved Man of the Cherokee from 1753 until his death in 1760. Settlers of European ancestry r ...

(or Guhna-gadoga,Conley 168 Kanagatucko, and "Standing Turkey")(1753–1756),Conley 168 war chief from Echota; either Ammouskossitte's uncle or father.

* Moytoy of Citico

Moytoy of Citico was said to be a Cherokee leader or war chief living in Virginia during the time of the Anglo-Cherokee War (1759–1761), but there is little evidence that he existed or that this name is correct.

Earliest References

The earliest ...

(or Amo-adaw-ehi), war chief during the Anglo-Cherokee War

The Anglo-Cherokee War (1758–1761; in the Cherokee language: the ''"war with those in the red coats"'' or ''"War with the English"''), was also known from the Anglo-European perspective as the Cherokee War, the Cherokee Uprising, or the Cherok ...

(1759–1761), nephew of the Moytoy of Tellico.Brown, John P"Eastern Cherokee Chiefs."

''Chronicles of Oklahoma.'' Vol. 16, No. 1. March 1938. Retrieved January 1, 2013. * Uka Ulah (also Ukah Ulah) (d. 1761), "emperor;" nephew of Old Hop, * Standing Turkey (or Cunne Shote), traveled to England in 1762 with

Henry Timberlake

Henry Timberlake (1730 or 1735 – September 30, 1765) was a colonial Anglo-American officer, journalist, and cartographer. He was born in the Colony of Virginia and died in England. He is best known for his work as an emissary from the Briti ...

* Outacite of Keowee

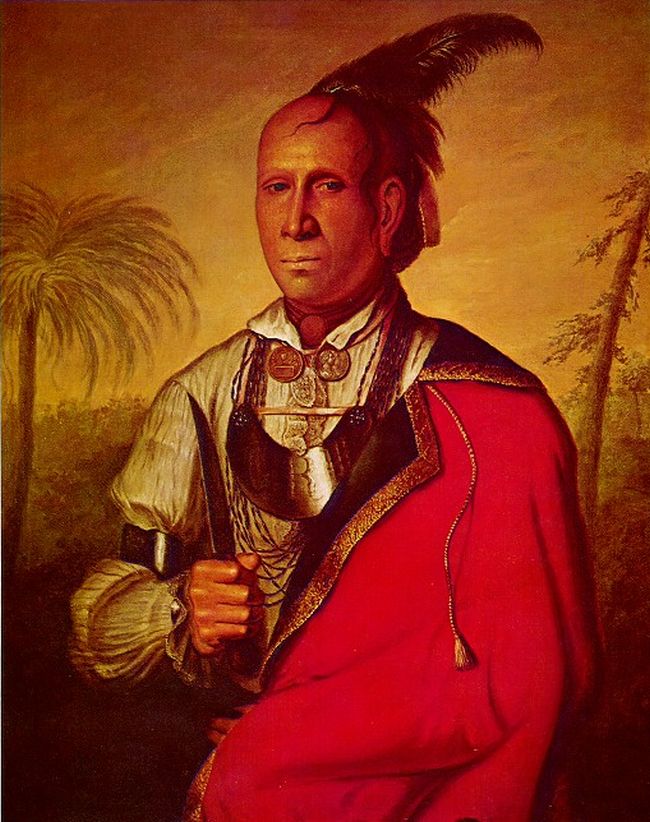

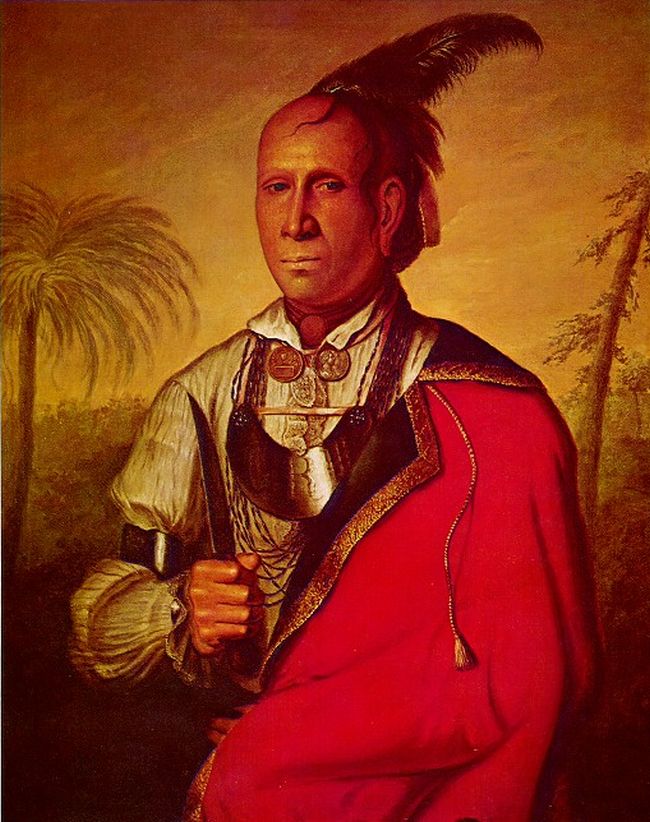

Otacity Ostenaco (; chr, ᎤᏥᏗᎯ ᎤᏍᏔᎾᏆ, Utsidihi Ustanaqua, or "Bighead"; c. 1710Kate Fullagar, ''The Warrior, the Voyager, and the Artist: Three Lives in an Age of Empire,''Yale University Press 2020 p.13. – 1780) was a Cher ...

(ca. 1703–ca. 1780) (also known as "Judd's Friend", Outacity, Outassite, Outacite, Outassatah, Wootasite, Wrosetasetow, Ostenaco, Outassete, Scyacust Ukah); he met Anglo-American emissary Henry Timberlake

Henry Timberlake (1730 or 1735 – September 30, 1765) was a colonial Anglo-American officer, journalist, and cartographer. He was born in the Colony of Virginia and died in England. He is best known for his work as an emissary from the Briti ...

when the latter went to Overhill country, and traveled with him to England in 1762

* Oconostota

Oconostota (c. 1710–1783) was a Cherokee ''skiagusta'' (war chief) of Chota, which was for nearly four decades the primary town in the Overhill territory, and within what is now Monroe County, Tennessee. He served as the First Beloved Man of Ch ...

(also known as Ogan'sto', "Groundhog Sausage") (1712–1781), red war chief of Echota; served entire tribe 1778–1785

* Savanukah

Savanukahwn (Cherokee) was known as the Raven of Chota in the late 18th century. The nephew of Oconostota, he became First Beloved Man of the Cherokee in the fall of 1781. He was ousted by the elders of the Overhill towns in 1783 in favor of the ...

of Chota (1781–1783)

* Old Tassel

Old Tassel Reyetaeh (sometimes Corntassel) (Cherokee language: ''Utsi'dsata''), (died 1788), was "First Beloved Man" (the equivalent of a regional Cherokee chief) of the Overhill Cherokee after 1783, when the United States gained independence from ...

(or "Corntassel," "Tassel," Kaiyatahee) (d. 1788), peace chief from Echota, served 1783–1788

* Raven of Chota

The Raven of Chota was a title given to Cherokee war leaders from the town of Chota. In time of war, Ravens scouted ahead of war parties to search for the enemy. According to historian Colin Calloway, "Every Cherokee town had 'Ravens,' but the Rav ...

(or Colonah), war chief; nephew of Oconostota

* Little Turkey, served 1788–1794

** opposed by Hanging Maw

Hanging Maw, or ''Uskwa'li-gu'ta'' in Cherokee, was the leading chief of the Overhill Cherokee from 1788 to 1794. They were located in present-day southeastern Tennessee. He became chief following the death of Old Tassel, and the abandonment of ...

(or Scolaguta), served 1788–1794

Chickamauga/Lower Cherokee (1777–1809)

In 1777, Dragging Canoe and a large body of Cherokee, primarily from Tennessee, separated from the bands that had signed treaties of peace with the Americans during theAmerican Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

. They migrated first to the Chickamauga (now Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

) region, then to the "Five Lower Towns" areafurther west and southwest of therein order to continue fighting (see Cherokee–American wars

The Cherokee–American wars, also known as the Chickamauga Wars, were a series of raids, campaigns, ambushes, minor skirmishes, and several full-scale frontier battles in the Old Southwest from 1776 to 1794 between the Cherokee and American se ...

). In time, these ''Chickamauga Cherokee

The Chickamauga Cherokee refers to a group that separated from the greater body of the Cherokee during the American Revolutionary War. The majority of the Cherokee people wished to make peace with the Americans near the end of 1776, following se ...

'' comprised a majority of the nation, due to both sympathy with their cause and the destruction of the homes of other Cherokee who later joined them. The separation ended at a reunification council with the Cherokee Nation in 1809.

Chiefs:

* Dragging Canoe

Dragging Canoe (ᏥᏳ ᎦᏅᏏᏂ, pronounced ''Tsiyu Gansini'', "he is dragging his canoe") (c. 1738 – February 29, 1792) was a Cherokee war chief who led a band of Cherokee warriors who resisted colonists and United States settlers in the ...

(1777–1792)

* John Watts (1792–1802)

* Doublehead

Doublehead (1744–1807) or Incalatanga (''Tal-tsu'tsa'', ᏔᎵᏧᏍᎦ in Cherokee), was one of the most feared warriors of the Cherokee during the Cherokee–American wars. Following the peace treaty at the Tellico Blockhouse in 1794, he serv ...

, brother of Old Tassel

Old Tassel Reyetaeh (sometimes Corntassel) (Cherokee language: ''Utsi'dsata''), (died 1788), was "First Beloved Man" (the equivalent of a regional Cherokee chief) of the Overhill Cherokee after 1783, when the United States gained independence from ...

, served 1802–1807

* The Glass

Ta'gwadihi ("Catawba-killer"), also known as Thomas Glass or simply the Glass, at least in correspondence with American officials, was a leading chief of the Cherokee in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, eventually becoming the last princi ...

, or Ta'gwadihi (1807–1809)

Cherokee Nation East (1794–1839)

Little Turkey was elected First Beloved Man of the Cherokee (the council seat of which was shifted south to Ustanali (later known as New Echota), near what is now

Little Turkey was elected First Beloved Man of the Cherokee (the council seat of which was shifted south to Ustanali (later known as New Echota), near what is now Calhoun, Georgia

Calhoun is a city in Gordon County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 16,949. Calhoun is the county seat of Gordon County.

History

In December 1827, Georgia had already claimed the Cherokee lands that be ...

) in the aftermath of the assassination by frontiersmen of Corntassel (also called Cornsilk) and several other leaders. Hanging Maw of Coyatee, listed above, claimed the title as his right by tradition, as he was the headman of the Upper Towns. Many Cherokee and the US government recognized him as Principal Chief. Little Turkey was finally recognized as "Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation" by all the towns after the end of the Cherokee–American wars

The Cherokee–American wars, also known as the Chickamauga Wars, were a series of raids, campaigns, ambushes, minor skirmishes, and several full-scale frontier battles in the Old Southwest from 1776 to 1794 between the Cherokee and American se ...

, when the Cherokee established their first nominal national government.

* Little Turkey (1794–1801)

* Black Fox (1801–1811)

* Pathkiller

Pathkiller, (died January 8, 1827) was a Cherokee warrior and Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation.

Warrior life

PathkillerPathkiller is a Cherokee rank or title—not a name. His original name is unknown. fought against the Overmountain Men ...

(1811–1827)

** Big Tiger (1824–1828); self-proclaimed chief of a faction of those following Whitepath's teachings (which were inspired by Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

prophet Handsome Lake

Handsome Lake ( Cayuga language: Sganyadái:yo, Seneca language: Sganyodaiyo) (Θkanyatararí•yau• in Tuscarora) (1735 – 10 August 1815) was a Seneca religious leader of the Iroquois people. He was a half-brother to Cornplanter, a Seneca ...

)

* Charles R. Hicks (1827), ''de facto'' head of government from 1813

* William Hicks (1827–1828)

* John Ross (1828–1839)

** William Hicks (1833–1835), elected principal chief of the faction supporting emigration to the west

Cherokee Nation West (1810–1839)

Originally settling along the St. Francis andWhite

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

rivers in what was classified first as Spanish Louisiana

Spanish Louisiana ( es, link=no, la Luisiana) was a governorate and administrative district of the Viceroyalty of New Spain from 1762 to 1801 that consisted of a vast territory in the center of North America encompassing the western basin of t ...

and later Arkansas Territory

The Arkansas Territory was a territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1819, to June 15, 1836, when the final extent of Arkansas Territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Arkansas. Arkansas Post was the first territo ...

after the United States acquired it, the Western Cherokee eventually migrated to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

in 1828 after the Treaty of Washington. They named their capital there Tahlontiskee. John Jolly died while the Latecomers were arriving, and John Looney succeeded him automatically. Looney was deposed by the council and replaced with Brown; his supporters wanted to put the Cherokee Nation West in a better position vis-a-vis the Ross party of Cherokee Nation East.

The removal of the eastern Cherokee Territory took place in 1839. It was followed by the assassinations in June 1839 of Major Ridge

Major Ridge, The Ridge (and sometimes Pathkiller II) (c. 1771 – 22 June 1839) (also known as ''Nunnehidihi'', and later ''Ganundalegi'') was a Cherokee leader, a member of the tribal council, and a lawmaker. As a warrior, he fought in the ...

, John Ridge

John Ridge, born ''Skah-tle-loh-skee'' (ᏍᎦᏞᎶᏍᎩ, Yellow Bird) ( – 22 June 1839), was from a prominent family of the Cherokee Nation, then located in present-day Georgia. He went to Cornwall, Connecticut, to study at the Foreign Mis ...

, and Elias Boudinot

Elias Boudinot ( ; May 2, 1740 – October 24, 1821) was a lawyer and statesman from Elizabeth, New Jersey who was a delegate to the Continental Congress (more accurately referred to as the Congress of the Confederation) and served as Presiden ...

(Treaty party members who had supported the Old Settlers). At that time, the council deposed Brown, replacing him with Looney. A sizable faction of the Old Settlers refused to recognize Looney and elected Rogers in his stead, but their efforts to maintain autonomy petered out the next year.

* The Bowl (1810–1813)

* Degadoga (1813–1817)

* Tahlonteeskee (1817–1819)

* John Jolly

John Jolly (Cherokee: ''Ahuludegi''; also known as ''Oolooteka''), was a leader of the Cherokee in Tennessee, the Arkansas Territory, and the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. After 1818, he was the Principal Chief and after reorganization of the t ...

(1819–1838)

* John Looney (1838–1839)

* John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

(1839)

* John Looney (1839)

* John Rogers (1839–1840)

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (1824–present)

The

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI), (Cherokee language, Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᏱ ᏕᏣᏓᏂᎸᎩ, ''Tsalagiyi Detsadanilvgi'') is a Federally recognized tribe, federally recognized Indian Tribe based in Western North Carolina in the U ...

is made up of descendants of Cherokee primarily from along the Oconaluftee River

The Oconaluftee River drains the south-central Oconaluftee valley of the Great Smoky Mountains in Western North Carolina before emptying into the Tuckasegee River. The river flows through the Qualla Boundary, a federal land trust that serves as ...

in Western North Carolina

Western North Carolina (often abbreviated as WNC) is the region of North Carolina which includes the Appalachian Mountains; it is often known geographically as the state's Mountain Region. It contains the highest mountains in the Eastern United S ...

, in today's Cherokee County. The band formed after the treaties of 1817 and 1819 were made between the Cherokee Nation East and the US government; they were outside the former territory. They were later joined by Utsala's band from the Nantahala River

The Nantahala River ()

, from the North Carolina Collection's website at the

After removal of the eastern Cherokee to

After removal of the eastern Cherokee to

In preparation for Oklahoma statehood, the original Cherokee Nation's governmental authority was dismantled by the United States in 1906, except for limited authority to deal with land issues until 1914. The Principal Chief was appointed by the

In preparation for Oklahoma statehood, the original Cherokee Nation's governmental authority was dismantled by the United States in 1906, except for limited authority to deal with land issues until 1914. The Principal Chief was appointed by the

"Cherokee Nation: Challenger wins chief election."

''Associated Press.'' October 11, 2011 (retrieved October 12, 2011)

''A Cherokee Encyclopedia.''

Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2007. . * Hoig, Stanley. ''The Cherokees and Their Chiefs: In the Wake of Empire''. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998. * McLoughlin, William G. ''Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic''. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992. * Mooney, James. ''Myths of the Cherokee and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokee'' (1900). Reprint: Nashville: Charles and Randy Elder-Booksellers, 1982. * Moore, John Trotwood and Austin P. Foster. ''Tennessee, The Volunteer State, 1769–1923, Vol. 1''. Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1923. * Morand, Anne, Kevin Smith, Daniel C. Swan, Sarah Erwin. ''Treasures of Gilcrease: Selections from the Permanent Collection.'' Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2005. . * Timberlake, Henry and Duane King

''The Memoirs of Lt. Henry Timberlake: The Story of a Soldier, Adventurer, and Emissary to the Cherokees, 1756–1765.''

University of North Carolina Press, 2007. . * Wilkins, Thurman. ''Cherokee Tragedy: The Ridge Family and the Decimation of a People''. New York: Macmillan Company, 1970. {{DEFAULTSORT:Principal Chiefs of the Cherokee, List of Titles and offices of Native American leaders History of the Cherokee Cherokee Nation Cherokee Nation (1794–1907) Lists of Native American people 1794 establishments in the United States

, from the North Carolina Collection's website at the

Indian Removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a de ...

of most of the Cherokee to Indian Territory.

Principal chiefs:

* Yonaguska

Yonaguska, (1759–1839), who was known as Drowning Bear (the English meaning of his name), was a leader among the Cherokee of the Lower Towns of North Carolina.

During the Indian Removal of the late 1830s, he was the only chief who remained in ...

(1824–1839)

* Salonitah, or Flying Squirrel (1870–1875)

* Lloyd R. Welch

Lloyd Richard Welch (born September 28, 1927) is an American information theorist and applied mathematician, and co-inventor of the Baum–Welch algorithm and the Berlekamp–Welch algorithm, also known as the Welch–Berlekamp algorithm.

Welch r ...

(1875–1880)

* Nimrod Jarrett Smith (1880–1891)

* Stillwell Saunooke (1891–1895)

* Andy Standing Deer (1895–1899)

* Jesse Reed (1899–1903)

* Bird Saloloneeta, or Young Squirrel (1903–1907)

* John Goins Welch (1907–1911)

* Joseph A. Saunooke (1911–1915)

* David Blythe

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

(1915–1919)

* Joseph A. Saunooke (1919–1923)

* Sampson Owl (1923–1927)

* John A. Tahquette (1927–1931)

* Jarret Blythe (1931–1947)

* Henry Bradley

Henry Bradley, FBA (3 December 1845 – 23 May 1923) was a British philologist and lexicographer who succeeded James Murray as senior editor of the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (OED).

Early life

Bradley had humble beginnings as a farmer's so ...

(1947–1951)

* Jarret Blythe (1955–1959)

* Osley Bird Saunooke (1951–1955)

* Jarret Blythe (1955–1959)

* Olsey Bird Saunooke (1959–1963)

* Jarret Blythe (1963–1967)

* Walter Jackson (1967–1971)

* Noah Powell

Noah ''Nukh''; am, ኖህ, ''Noḥ''; ar, نُوح '; grc, Νῶε ''Nôe'' () is the tenth and last of the Antediluvian, pre-Flood Patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bibl ...

(1971–1973)

* John A. Crowe (1973–1983)

* Robert S. Youngdeer (1983–1987)

* Jonathan L. Taylor (1987–1995)

* Gerard Parker (1995)

* Joyce Dugan

Joyce Dugan (born c.1952, Cherokee people, Cherokee) is an American educator, school administrator, and politician; she served as the 24th Principal Chief of the federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (1995-1999), based in Western No ...

(1995–1999)

* Leon Jones (1999–2003)

* Michell Hicks (2003–2015)

* Patrick Lambert

Patrick Henry Lambert (born September 4, 1963, in Cherokee, North Carolina) is a Native American tribal leader who served as the 27th Principal Chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians from 2015 to 2017. He also served as the Executive Direc ...

(2015-2017)

* Richard Sneed (2017–present)

Two principal chiefs of the tribe have been impeached

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

since the late 20th century: Jonathan L. Taylor in 1995 and Patrick Lambert

Patrick Henry Lambert (born September 4, 1963, in Cherokee, North Carolina) is a Native American tribal leader who served as the 27th Principal Chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians from 2015 to 2017. He also served as the Executive Direc ...

in 2017.

Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory (1839–1907)

After removal of the eastern Cherokee to

After removal of the eastern Cherokee to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

on the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

, they created a new constitution to unify the former Eastern Cherokee with the Western Cherokee. This allowed for direct election of the Principal Chief. Though a holdout minority of the Old Settlers elected John Rogers as their principal chief, his government never gained further support and soon faded away.

The John Ross faction abandoned the established capital of Tahlontiskee and built Tahlequah instead. During the Civil War, the Nation voted to support the Confederacy, and Ross acquiesced for a time. In 1862, however, he and many of his supporters fled to Washington, DC. At that time Stand Watie

Brigadier-General Stand Watie ( chr, ᏕᎦᏔᎦ, translit=Degataga, lit=Stand firm; December 12, 1806September 9, 1871), also known as Standhope Uwatie, Tawkertawker, and Isaac S. Watie, was a Cherokee politician who served as the second princ ...

, serving as a Confederate officer, was elected Principal Chief by a portion of the Nation. The remaining Ross group never supported Watie's election, though, and lived apart under their own officials.

* John Ross (1839–1866)

** Thomas Pegg, acting principal chief of the Union Cherokee (1862–1863)

** Smith Christie, acting principal chief of the Union Cherokee (1863)

** Lewis Downing, acting principal chief of the Union Cherokee (1864–1866)

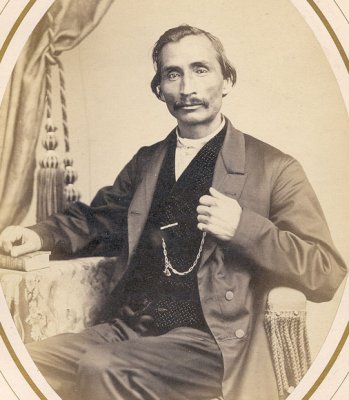

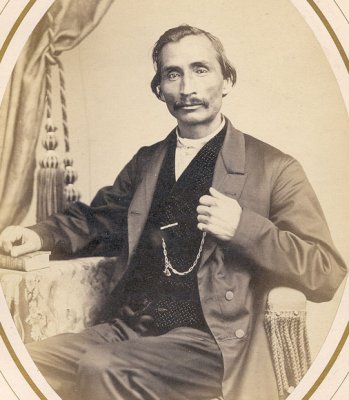

* Stand Watie

Brigadier-General Stand Watie ( chr, ᏕᎦᏔᎦ, translit=Degataga, lit=Stand firm; December 12, 1806September 9, 1871), also known as Standhope Uwatie, Tawkertawker, and Isaac S. Watie, was a Cherokee politician who served as the second princ ...

, (1862–1866)

* William P. Ross

William Potter Ross (August 28, 1820 – July 20, 1891), also known as Will Ross, was the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation (19th century), Cherokee Nation 1866-1867 and 1872-1875. Born to a Scottish father and a mixed-blood Cherokee mothe ...

(1866–1867)

* Lewis Downing (1867–1872)

* William P. Ross (1872–1875)

* Charles Thompson (1875–1879)

* Dennis Bushyhead (1879–1887)

* Joel B. Mayes (1887–1891)

* C. J. Harris (1891–1895)

* Samuel Houston Mayes

Samuel Houston Mayes (May 11, 1845 – December 12, 1927) of Scots/English-Cherokee descent, was elected as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), serving from 1895 to 1899. His maternal grandfather be ...

(1895–1899)

* Thomas Buffington

Thomas Mitchell Buffington was born October 15, 1855, in Going Snake District of the Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory, now in Adair County, Oklahoma. His parents were Ezekiel Buffington, who was born in Georgia in 1807 and settled in Oklahoma Terr ...

(1899–1903)

* William Rogers (1903–1905); deposed by the council

* Frank J. Boudinot (1905–1906); also president of the Keetoowah Nighthawk Society

The Keetoowah Nighthawk Society was a Cherokee organisation formed ''ca.'' 1900 that intended to preserve and practice traditional "old ways" of tribal life, based on religious nationalism. It was led by Redbird Smith, a Cherokee National Council ...

* William Charles Rogers

William Charles Rogers (December 13, 1847 – November 8, 1917) was born in the Cherokee Nation near present-day Skiatook, Oklahoma, USA, on December 13, 1847. A Confederate veteran and successful farmer, he entered tribal politics in 1881.

(1906)

Cherokee Nation (1975–present)

In preparation for Oklahoma statehood, the original Cherokee Nation's governmental authority was dismantled by the United States in 1906, except for limited authority to deal with land issues until 1914. The Principal Chief was appointed by the

In preparation for Oklahoma statehood, the original Cherokee Nation's governmental authority was dismantled by the United States in 1906, except for limited authority to deal with land issues until 1914. The Principal Chief was appointed by the US federal government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fed ...

. In 1971 an election was held. Principal Chief and incumbent, W.W. Keeler, who had been appointed by President Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

in 1949, was elected.

The constitution of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma

The Cherokee Nation (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ''Tsalagihi Ayeli'' or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ ''Tsalagiyehli''), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It ...

was drafted in 1975 and ratified on June 26, 1976. A new constitution was ratified in 2003 with the name of the tribe changed to simply "Cherokee Nation".

Appointed

Appointed "Principal Chiefs", many holding the title to serve for a single day, signed documents and performed other pro forma duties as required by the federal government. * William C. Rogers (1907–1917) :: With the admission ofOklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

to the Union as the forty-sixth state and to extinguish land claims and terminate any unfinished business of the tribe, an Act of April 26, 1906 (34 Statutes at Large, 148) continued the tribal governments, and retained the principal chiefs and governors then in office. Under provisions of this act, Rogers continued in office to sign the deeds transferring the lands of the Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ''Tsalagihi Ayeli'' or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ ''Tsalagiyehli''), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It ...

to the individual allottees. Upon his death on November 8, 1917, the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

was authorized by this act to appoint Rogers' successor.

* Charles J. Hunt (December 27, 1928)

* Oliver P. Brewer (May 26, 1931)

* William W. Hastings (January 22, 1936)

* J.B. Milam (1941–1949)

* W.W. Keeler (1949–1971)

Elected

* W.W. Keeler (1971–1975) *Ross Swimmer Ross or ROSS may refer to:

People

* Clan Ross, a Highland Scottish clan

* Ross (name), including a list of people with the surname or given name Ross, as well as the meaning

* Earl of Ross, a peerage of Scotland

Places

* RoSS, the Republic of Sout ...

(1975–1985)

* Wilma Mankiller

Wilma Pearl Mankiller ( chr, ᎠᏥᎳᏍᎩ ᎠᏍᎦᏯᏗᎯ, Atsilasgi Asgayadihi; November 18, 1945April 6, 2010) was a Native American (Cherokee Nation) activist, social worker, community developer and the first woman elected to serve a ...

(1985–1995)

* Joe Byrd (1995–1999)

* Chad "Corntassel" Smith

Chadwick "Corntassel" Smith (Cherokee name Ugista:ᎤᎩᏍᏔ derived from Cherokee word for "Corntassel", Utsitsata:ᎤᏥᏣᏔ; born December 17, 1950, in Pontiac, Michigan) is a former Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. He was first e ...

(1999–2011)

* S. Joe Crittenden (acting, 2011)

* Bill John Baker (2011–2019)

* Chuck Hoskin Jr.

Chuck Hoskin Jr. (born 1974/1975) is a Cherokee-American politician and attorney currently serving as the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation since 2019.

Hoskin has previously served as a Tribal Councilor for the Cherokee Nation between 2007 a ...

(2019–present)Jouzapavicius, Justin"Cherokee Nation: Challenger wins chief election."

''Associated Press.'' October 11, 2011 (retrieved October 12, 2011)

United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians (1939–present)

The UKB Cherokee are descendants primarily of Old Settlers who organized under the federal Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 and the state Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936. They ratified their constitution and bylaws and were recognized by the federal government in 1950. * John Hitcher (1939–1946) * Jim Pickup (1946–1954) *Jeff Tindle

Jeff is a masculine name, often a short form (hypocorism) of the English given name Jefferson (given name), Jefferson or Jeffrey (given name), Jeffrey, which comes from a Middle Ages, medieval variant of Geoffrey (given name), Geoffrey.

Music

...

(1954–1960)

* Jim Pickup (1960–1967)

* William Glory (1967–1979)

* James L. Gordon (1979–1983)

* John Hair (1983–1991)

* John Ross (1991–1995)

* Jim Henson

James Maury Henson (September 24, 1936 – May 16, 1990) was an American puppeteer, animator, cartoonist, actor, inventor, and filmmaker who achieved worldwide notice as the creator of The Muppets and '' Fraggle Rock'' (1983–1987) and ...

(1996–2000)

* Dallas Proctor 2000–2004

* George Wickliffe 2005–2016

* Joe Bunch 2016–present

See also

*Junaluska

Junaluska (Cherokee: ''Tsunu’lahun’ski'') (c.1775 – October 20, 1868), was a leader of Cherokee who resided in towns in western North Carolina in the early 19th century. He fought alongside Andrew Jackson, and saved his life, at the Battle ...

* Mount Tabor Indian Community

The Mount Tabor Indian Community (also Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands of the Mount Tabor Indian Community) is a cultural heritage group located in Rusk County, Texas. There was a historical Mount Tabor Indian Community dating from the 19th c ...

References

* Brown, John P. ''Old Frontiers''. Kingsport: Southern Publishers, 1938. * Conley, Robert J. ''The Cherokee Nation: A History''. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008. * Conley, Robert J''A Cherokee Encyclopedia.''

Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2007. . * Hoig, Stanley. ''The Cherokees and Their Chiefs: In the Wake of Empire''. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998. * McLoughlin, William G. ''Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic''. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992. * Mooney, James. ''Myths of the Cherokee and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokee'' (1900). Reprint: Nashville: Charles and Randy Elder-Booksellers, 1982. * Moore, John Trotwood and Austin P. Foster. ''Tennessee, The Volunteer State, 1769–1923, Vol. 1''. Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1923. * Morand, Anne, Kevin Smith, Daniel C. Swan, Sarah Erwin. ''Treasures of Gilcrease: Selections from the Permanent Collection.'' Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2005. . * Timberlake, Henry and Duane King

''The Memoirs of Lt. Henry Timberlake: The Story of a Soldier, Adventurer, and Emissary to the Cherokees, 1756–1765.''

University of North Carolina Press, 2007. . * Wilkins, Thurman. ''Cherokee Tragedy: The Ridge Family and the Decimation of a People''. New York: Macmillan Company, 1970. {{DEFAULTSORT:Principal Chiefs of the Cherokee, List of Titles and offices of Native American leaders History of the Cherokee Cherokee Nation Cherokee Nation (1794–1907) Lists of Native American people 1794 establishments in the United States