President Tito on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav

In February 1928, Broz was one of 32 delegates to the conference of the Croatian branch of the CPY. During the conference, Broz condemned factions within the party. These included those that advocated a

In February 1928, Broz was one of 32 delegates to the conference of the Croatian branch of the CPY. During the conference, Broz condemned factions within the party. These included those that advocated a

After his sentencing, his wife and son returned to Kumrovec, where they were looked after by sympathetic locals, but then one day they suddenly left without explanation and returned to the Soviet Union. She fell in love with another man and Žarko grew up in institutions. After arriving at Lepoglava prison, Broz was employed in maintaining the electrical system, and chose as his assistant a middle-class Belgrade Jew,

After his sentencing, his wife and son returned to Kumrovec, where they were looked after by sympathetic locals, but then one day they suddenly left without explanation and returned to the Soviet Union. She fell in love with another man and Žarko grew up in institutions. After arriving at Lepoglava prison, Broz was employed in maintaining the electrical system, and chose as his assistant a middle-class Belgrade Jew,

During this time Tito wrote articles on the duties of imprisoned communists and on trade unions. He was in Ljubljana when King Alexander was assassinated by Vlado Chernozemski and the Croatian nationalist ''

During this time Tito wrote articles on the duties of imprisoned communists and on trade unions. He was in Ljubljana when King Alexander was assassinated by Vlado Chernozemski and the Croatian nationalist '' Tito returned to Moscow in August 1936, soon after the outbreak of the

Tito returned to Moscow in August 1936, soon after the outbreak of the

On arrival in Moscow, he found that all Yugoslav communists were under suspicion. Nearly all the most prominent leaders of the CPY were arrested by the NKVD and executed, including over twenty members of the Central Committee. Both his ex-wife Polka and his wife Koenig/Bauer were arrested as "imperialist spies", although they were both eventually released, Polka after 27 months in prison. Tito, therefore, needed to make arrangements for the care of Žarko, who was fourteen. He placed him in a boarding school outside

On arrival in Moscow, he found that all Yugoslav communists were under suspicion. Nearly all the most prominent leaders of the CPY were arrested by the NKVD and executed, including over twenty members of the Central Committee. Both his ex-wife Polka and his wife Koenig/Bauer were arrested as "imperialist spies", although they were both eventually released, Polka after 27 months in prison. Tito, therefore, needed to make arrangements for the care of Žarko, who was fourteen. He placed him in a boarding school outside

On 6 April 1941, Axis forces invaded Yugoslavia. On 10 April 1941,

On 6 April 1941, Axis forces invaded Yugoslavia. On 10 April 1941,  Tito stayed in Belgrade until 16 September 1941 when he, together with all members of the CPY, left Belgrade to travel to rebel-controlled territory. To leave Belgrade Tito used documents given to him by Dragoljub Milutinović, who was a ''

Tito stayed in Belgrade until 16 September 1941 when he, together with all members of the CPY, left Belgrade to travel to rebel-controlled territory. To leave Belgrade Tito used documents given to him by Dragoljub Milutinović, who was a '' With the growing possibility of an Allied invasion in the

With the growing possibility of an Allied invasion in the  On 12 August 1944, Winston Churchill met Tito in

On 12 August 1944, Winston Churchill met Tito in

On 7 March 1945, the provisional government of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (''Demokratska Federativna Jugoslavija'', DFY) was assembled in

On 7 March 1945, the provisional government of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (''Demokratska Federativna Jugoslavija'', DFY) was assembled in

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective, to refer to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor.

...

and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his death in 1980. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, he was the leader of the Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, Slovene: , or the National Liberation Army, sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska (NOV), Народноослободилачка војска (НОВ); mk, Народноослобод ...

, often regarded as the most effective resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized effort by some portion of the civil population of a country to withstand the legally established government or an occupying power and to disrupt civil order and stability. It may seek to achieve its objective ...

in German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

. He also served as the president of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yug ...

from 14 January 1953 until his death on 4 May 1980.

He was born to a Croat father and Slovene mother in the village of Kumrovec, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

(now in Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

). Drafted into military service, he distinguished himself, becoming the youngest sergeant major in the Austro-Hungarian Army of that time. After being seriously wounded and captured by the Russians during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, he was sent to a work camp in the Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

. He participated in some events of the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

in 1917 and the subsequent Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. Upon his return to the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

in 1918, he entered the newly established Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 unt ...

, where he joined the Communist Party of Yugoslavia

The League of Communists of Yugoslavia, mk, Сојуз на комунистите на Југославија, Sojuz na komunistite na Jugoslavija known until 1952 as the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, sl, Komunistična partija Jugoslavije mk ...

(KPJ). Having assumed de facto control over the party by 1937, he was formally elected its general secretary in 1939 and later its president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

, the title he held until his death. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, after the Nazi invasion of the area, he led the Yugoslav guerrilla movement, the Partisans (1941–1945). By the end of the war, the Partisans—with the backing of the invading Soviet Union—took power over Yugoslavia.

After the war, Tito was the chief architect of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), serving as both prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

(1944–1963), president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

(since 1974 president for life) (1953–1980), and marshal of Yugoslavia

Marshal of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Maršal Jugoslavije, Маршал Југославије; sl, Maršal Jugoslavije; mk, Маршал на Југославија, Maršal na Jugoslavija) was the Highest military ranks, hig ...

, the highest rank of the Yugoslav People's Army

The Yugoslav People's Army (abbreviated as JNA/; Macedonian and sr-Cyrl-Latn, Југословенска народна армија, Jugoslovenska narodna armija; Croatian and bs, Jugoslavenska narodna armija; sl, Jugoslovanska ljudska a ...

(JNA). Despite being one of the founders of Cominform, he became the first Cominform member to defy Soviet hegemony in 1948. He was the only leader in Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

's time to leave Cominform and begin with his country's own socialist program, which contained elements of market socialism

Market socialism is a type of economic system involving the public, cooperative, or social ownership of the means of production in the framework of a market economy, or one that contains a mix of worker-owned, nationalized, and privately owned ...

. Economists active in the former Yugoslavia, including Czech-born Jaroslav Vaněk

Jaroslav Vaněk (20 April 1930 – 15 November 2017) was a Czech American economist and Professor Emeritus of Cornell University known for his research on economics of participation ( labour-managed firms, worker cooperatives) and, in his earlier ...

and Yugoslav-born Branko Horvat, promoted a model of market socialism that was dubbed the Illyrian model. Firms were socially owned

Social ownership is the appropriation of the surplus product, produced by the means of production, or the wealth that comes from it, to society as a whole. It is the defining characteristic of a socialist economic system. It can take the form ...

by their employees and structured on workers' self-management; they competed in open and free market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any o ...

s. Tito managed to keep ethnic tensions under control by delegating as much power as possible to each republic. The 1974 Yugoslav Constitution

The 1974 Yugoslav Constitution was the fourth and final constitution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. It came into effect on 21 February 1974.

With 406 original articles, the 1974 constitution was one of the longest constitutio ...

defined SFR Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yug ...

as a "federal republic of equal nations and nationalities, freely united on the principle of brotherhood and unity in achieving specific and common interest." Each republic was also given the right to self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

and secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

if done through legal channels. Lastly, Tito gave Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a partially recognised state in Southeast Euro ...

and Vojvodina, the two constituent provinces of Serbia, substantially increased autonomy, including de facto veto power in the Serbian parliament

The National Assembly ( sr-cyr, Народна скупштина, Narodna skupština, ) is the unicameral legislature of Serbia. The assembly is composed of 250 deputies who are proportionally elected to four-year terms by secret ballot. The as ...

. Tito built a very powerful cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an id ...

around himself, which was maintained by the League of Communists of Yugoslavia even after his death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

. Twelve years after his death, as communism collapsed in Eastern Europe, Yugoslavia dissolved and descended into a series of interethnic wars.

Some historians criticize Tito's presidency as authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

, while others see him as a benevolent dictator. He was a popular public figure both in Yugoslavia and abroad. Viewed as a unifying symbol, his internal policies maintained the peaceful coexistence of the nations of the Yugoslav federation. He gained further international attention as the chief leader of the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath o ...

, alongside Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

of India, Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-re ...

of Egypt, Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah (born 21 September 190927 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He was the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana, having led the Gold Coast to independence from Britain in 1957. An in ...

of Ghana, and Sukarno

Sukarno). (; born Koesno Sosrodihardjo, ; 6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of ...

of Indonesia.Peter Willetts, ''The Non-aligned Movement: The Origins of a Third World Alliance'' (1978) p. xiv With a highly favourable reputation abroad in both Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

blocs, he received a total of 98 foreign decorations, including the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon, ...

and the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved Bathing#Medieval ...

.

Early life

Pre-World War I

Josip Broz was born on 7 May 1892 in Kumrovec, a village in the northern Croatian region of Hrvatsko Zagorje. At the time it was part of theKingdom of Croatia-Slavonia

The Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia ( hr, Kraljevina Hrvatska i Slavonija; hu, Horvát-Szlavónország or ; de-AT, Königreich Kroatien und Slawonien) was a nominally autonomous kingdom and constitutionally defined separate political nation with ...

within the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

. He was the seventh or eighth child of Franjo Broz (1860–1936) and Marija née Javeršek (1864–1918). His parents had already had a number of children die in early infancy. Broz was christened and raised as a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

. His father, Franjo, was a Croat whose family had lived in the village for three centuries, while his mother Marija, was a Slovene from the village of Podsreda

Podsreda (; german: Hörberg) is a village in the Municipality of Kozje in eastern Slovenia. It is located near the Croatian border, in the traditional region of Styria. It is known for its market, which takes place every Sunday, and for Podsreda ...

. The villages were apart, and his parents had married on 21 January 1881. Franjo Broz had inherited a estate and a good house, but he was unable to make a success of farming. Josip spent a significant proportion of his pre-school years living with his maternal grandparents at Podsreda, where he became a favourite of his grandfather Martin Javeršek. By the time he returned to Kumrovec to begin school, he spoke Slovene better than Croatian, and had learned to play the piano. Despite his mixed parentage, Broz identified as a Croat like his father and neighbours.

In July 1900, at the age of eight, Broz entered primary school at Kumrovec. He completed four years of school, failing the 2nd grade and graduating in 1905. As a result of his limited schooling, throughout his life Tito was poor at spelling. After leaving school, he initially worked for a maternal uncle, and then on his parents' family farm. In 1907, his father wanted him to emigrate to the United States, but could not raise the money for the voyage.

Instead, aged 15 years, Broz left Kumrovec and travelled about south to Sisak

Sisak (; hu, Sziszek ; also known by other alternative names) is a city in central Croatia, spanning the confluence of the Kupa, Sava and Odra rivers, southeast of the Croatian capital Zagreb, and is usually considered to be where the Posavin ...

, where his cousin Jurica Broz was doing army service. Jurica helped him get a job in a restaurant, but Broz was soon tired of that work. He approached a Czech locksmith, Nikola Karas, for a three-year apprenticeship, which included training, food, and room and board

Room and board is a phrase describing a situation in which, in exchange for money, Manual labour, labor or other considerations, a person is provided with a place to live as well as meals on a comprehensive basis. It commonly occurs as a fee at h ...

. As his father could not afford to pay for his work clothing, Broz paid for it himself. Soon after, his younger brother Stjepan also became apprenticed to Karas.

During his apprenticeship, Broz was encouraged to mark May Day in 1909, and he read and sold ''Slobodna Reč'' (''Free Word''), a socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

newspaper. After completing his apprenticeship in September 1910, Broz used his contacts to gain employment in Zagreb

Zagreb ( , , , ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slop ...

. At the age of 18, he joined the Metal Workers' Union and participated in his first labour protest

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration or remonstrance) is a public expression of objection, disapproval or dissent towards an idea or action, typically a political one.

Protests can be thought of as acts of coopera ...

. He also joined the Social Democratic Party of Croatia and Slavonia

The Social Democratic Party of Croatia and Slavonia ( hr, Socijaldemokratska stranka Hrvatske i Slavonije or 'SDSHiS') was a social-democratic political party in the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia. The party was active from 1894 until 1916.

History

...

.

He returned home in December 1910. In early 1911 he began a series of moves in search of work, first seeking work in Ljubljana

Ljubljana (also known by other historical names) is the capital and largest city of Slovenia. It is the country's cultural, educational, economic, political and administrative center.

During antiquity, a Roman city called Emona stood in the ar ...

, then Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into provi ...

, Kumrovec and Zagreb, where he worked repairing bicycles. He joined his first strike action on May Day 1911. After a brief period of work in Ljubljana, between May 1911 and May 1912, he worked in a factory in Kamnik

Kamnik (; german: Stein''Leksikon občin kraljestev in dežel zastopanih v državnem zboru,'' vol. 6: ''Kranjsko''. 1906. Vienna: C. Kr. Dvorna in Državna Tiskarna, pp. 26–27. or ''Stein in Oberkrain'') is a town in northern Slovenia. It is t ...

in the Kamnik–Savinja Alps. After it closed, he was offered redeployment to Čenkov

Čenkov is a municipality and village in Příbram District in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 400 inhabitants. It lies on the Litavka

Litavka is a river in the Czech Republic, the right tributary of the Berounka. ...

in Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

. On arriving at his new workplace, he discovered that the employer was trying to bring in cheaper labour to replace the local Czech workers, and he and others joined successful strike action to force the employer to back down.

Driven by curiosity, Broz moved to Plzeň

Plzeň (; German and English: Pilsen, in German ) is a city in the Czech Republic. About west of Prague in western Bohemia, it is the Statutory city (Czech Republic), fourth most populous city in the Czech Republic with about 169,000 inhabita ...

, where he was briefly employed at the Škoda Works

The Škoda Works ( cs, Škodovy závody, ) was one of the largest European industrial conglomerates of the 20th century, founded by Czech engineer Emil Škoda in 1859 in Plzeň, then in the Kingdom of Bohemia, Austrian Empire. It is the predece ...

. He next travelled to Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

in Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

. He also worked at the Benz

Benz, an old Germanic clan name dating to the fifth century (related to "bear", "war banner", "gau", or a "land by a waterway") also used in German () as an alternative for names such as Berthold, Bernhard, or Benedict, may refer to:

People Sur ...

car factory in Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (german: Universitätsstadt Mannheim), is the second-largest city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg after the state capital of Stuttgart, and Germany's 2 ...

, and visited the Ruhr

The Ruhr ( ; german: Ruhrgebiet , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr area, sometimes Ruhr district, Ruhr region, or Ruhr valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 2,800/km ...

industrial region. By October 1912 he had reached Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. He stayed with his older brother Martin and his family, and worked at the Griedl Works before getting a job at Wiener Neustadt. There he worked for Austro-Daimler

Austro-Daimler was an Austro-Hungarian automaker company, from 1899 until 1934. It was a subsidiary of the German ''Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft'' (DMG) until 1909.

Early history

In 1890, Eduard Bierenz was appointed as Austrian retailer. The com ...

, and was often asked to drive and test the cars. During this time he spent considerable time fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline, s ...

and dancing, and during his training and early work life, he also learned German and passable Czech.

World War I

In May 1913, Broz was conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian Army, for his compulsory two years of service. He successfully requested to serve with the 25th Croatian Home Guard ( hr, Domobran, links=no) Regiment garrisoned in Zagreb. After learning to ski during the winter of 1913 and 1914, Broz was sent to a school fornon-commissioned officer

A non-commissioned officer (NCO) is a military officer who has not pursued a commission. Non-commissioned officers usually earn their position of authority by promotion through the enlisted ranks. (Non-officers, which includes most or all enli ...

s (NCO) in Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

, after which he was promoted to sergeant major. At 22 years of age, he was the youngest of that rank in his regiment. At least one source states that he was the youngest sergeant major in the Austro-Hungarian Army. After winning the regimental fencing competition, Broz came in second in the army fencing championships in Budapest in May 1914.

Soon after the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1914, the 25th Croatian Home Guard Regiment marched toward the Serbian

Serbian may refer to:

* someone or something related to Serbia, a country in Southeastern Europe

* someone or something related to the Serbs, a South Slavic people

* Serbian language

* Serbian names

See also

*

*

* Old Serbian (disambiguat ...

border. Broz was arrested for sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, estab ...

and imprisoned in the Petrovaradin fortress in present-day Novi Sad

Novi Sad ( sr-Cyrl, Нови Сад, ; hu, Újvidék, ; german: Neusatz; see below for other names) is the second largest city in Serbia and the capital of the autonomous province of Vojvodina. It is located in the southern portion of the Pan ...

. Broz later gave conflicting accounts of this arrest, telling one biographer that he had threatened to desert to the Russians, but also claiming that the whole matter arose from a clerical error. A third version was that he had been overheard saying that he hoped the Austro-Hungarian Empire would be defeated. After his acquittal and release, his regiment served briefly on the Serbian Front before being deployed to the Eastern Front in Galicia in early 1915 to fight against Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

. Tito in his own account of his military service did not mention that he participated in the failed Austrian invasion of Serbia, instead giving the misleading impression that he fought only in Galicia, as it would have offended Serbian opinion to know that he fought in 1914 for the Habsburgs against them. On one occasion, the scout

Scout may refer to:

Youth movement

*Scout (Scouting), a child, usually 10–18 years of age, participating in the worldwide Scouting movement

**Scouts (The Scout Association), section for 10-14 year olds in the United Kingdom

**Scouts BSA, sectio ...

platoon

A platoon is a military unit typically composed of two or more squads, sections, or patrols. Platoon organization varies depending on the country and the branch, but a platoon can be composed of 50 people, although specific platoons may range ...

he commanded went behind the enemy lines and captured 80 Russian soldiers, bringing them back to their own lines alive. In 1980 it was discovered that he had been recommended for an award for gallantry and initiative in reconnaissance and capturing prisoners. Tito's biographer, Richard West, wrote that Tito actually downplayed his military record as the Austrian Army records showed that he was a brave soldier, which contradicted his later claim to have been opposed to the Habsburg monarchy and his self-portrait of himself as an unwilling conscript fighting in a war he was opposed to. Broz was regarded by his fellow soldiers as ''kaisertreu'' ("true to the Emperor").

On 25 March 1915, he was wounded in the back by a Circassian cavalryman's lance, and captured during a Russian attack near Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter BergerT ...

. Broz in his account of his capture described it melodramatically as: "...but suddenly the right flank yielded and through the gap poured cavalry of the Circassians, from Asiatic Russia. Before we knew it they were thundering through our positions, leaping from their horses and throwing themselves into our trenches with lances lowered. One of them rammed his two-yard, iron-tipped, double-pronged lance into my back just below the left arm. I fainted. Then, as I learned, the Circassians began to butcher the wounded, even slashing them with their knives. Fortunately, Russian infantry reached the positions and put an end to the orgy". Now a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

(POW), Broz was transported east to a hospital established in an old monastery in the town of Sviyazhsk on the Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the List of rivers of Europe#Rivers of Europe by length, longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Cas ...

river near Kazan

Kazan ( ; rus, Казань, p=kɐˈzanʲ; tt-Cyrl, Казан, ''Qazan'', IPA: ɑzan is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka rivers, covering a ...

. During his 13 months in hospital he had bouts of pneumonia and typhus, and learned Russian with the help of two schoolgirls who brought him Russian classics by such authors as Tolstoy and Turgenev to read.

After recuperating, in mid-1916 he was transferred to the Ardatov POW camp in the Samara Governorate, where he used his skills to maintain the nearby village grain mill. At the end of the year, he was again transferred, this time to the Kungur POW camp near Perm where the POWs were used as labour to maintain the newly completed Trans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR; , , ) connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway line in the world. It runs from the city of Moscow in the west to the city of Vladivostok in the ea ...

. Broz was appointed to be in charge of all the POWs in the camp. During this time he became aware that the Red Cross parcel

Red Cross parcel refers to packages containing mostly food, tobacco and personal hygiene items sent by the International Association of the Red Cross to prisoners of war during the First and Second World Wars, as well as at other times. It can ...

s sent to the POWs were being stolen by camp staff. When he complained, he was beaten and put in prison. During the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

, a crowd broke into the prison and returned Broz to the POW camp. A Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

he had met while working on the railway told Broz that his son was working in an engineering works in Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, so, in June 1917, Broz walked out of the unguarded POW camp and hid aboard a goods train bound for that city, where he stayed with his friend's son. The journalist Richard West has suggested that because Broz chose to remain in an unguarded POW camp rather than volunteer to serve with the Yugoslav legions of the Serbian Army, this indicates that he remained loyal to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and undermines his later claim that he and other Croat POWs were excited by the prospect of revolution and looked forward to the overthrow of the empire that ruled them.

Less than a month after Broz arrived in Petrograd, the July Days demonstrations broke out, and Broz joined in, coming under fire from government troops. In the aftermath, he tried to flee to Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

in order to make his way to the United States but was stopped at the border. He was arrested along with other suspected Bolsheviks during the subsequent crackdown by the Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of the Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately ...

led by Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; Reforms of Russian orthography, original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months ...

. He was imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress

The Peter and Paul Fortress is the original citadel of St. Petersburg, Russia, founded by Peter the Great in 1703 and built to Domenico Trezzini's designs from 1706 to 1740 as a star fortress. Between the first half of the 1700s and early 1920s i ...

for three weeks, during which he claimed to be an innocent citizen of Perm. When he finally admitted to being an escaped POW, he was to be returned by train to Kungur, but escaped at Yekaterinburg

Yekaterinburg ( ; rus, Екатеринбург, p=jɪkətʲɪrʲɪnˈburk), alternatively romanized as Ekaterinburg and formerly known as Sverdlovsk ( rus, Свердло́вск, , svʲɪrˈdlofsk, 1924–1991), is a city and the administra ...

, then caught another train that reached Omsk

Omsk (; rus, Омск, p=omsk) is the administrative center and largest city of Omsk Oblast, Russia. It is situated in southwestern Siberia, and has a population of over 1.1 million. Omsk is the third largest city in Siberia after Novosibirsk ...

in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

on 8 November after a journey. At one point, police searched the train looking for an escaped POW, but were deceived by Broz's fluent Russian.

In Omsk, the train was stopped by local Bolsheviks who told Broz that Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

had seized control of Petrograd. They recruited him into an International Red Guard that guarded the Trans-Siberian Railway during the winter of 1917 and 1918. In May 1918, the anti-Bolshevik Czechoslovak Legion wrested control of parts of Siberia from Bolshevik forces, and the Provisional Siberian Government established itself in Omsk, and Broz and his comrades went into hiding. At this time Broz met a 14-year-old local girl, Pelagija "Polka" Belousova, who hid him then helped him escape to a Kazakh village from Omsk. Broz again worked maintaining the local mill until November 1919 when the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

recaptured Omsk from White forces loyal to the Provisional All-Russian Government of Alexander Kolchak

Alexander Vasilyevich Kolchak (russian: link=no, Александр Васильевич Колчак; – 7 February 1920) was an Imperial Russian admiral, military leader and polar explorer who served in the Imperial Russian Navy and fought ...

. He moved back to Omsk and married Belousova in January 1920. At the time of their marriage, Broz was 27 years old and Belousova was 15. Broz later wrote that during his time in Russia he heard much talk of Lenin, a little of Trotsky and "...as for Stalin, during the time I stayed in Russia, I never once heard his name". In the autumn of 1920, he and his pregnant wife returned to his homeland, first by train to Narva

Narva, russian: Нарва is a municipality and city in Estonia. It is located in Ida-Viru County, Ida-Viru county, at the Extreme points of Estonia, eastern extreme point of Estonia, on the west bank of the Narva (river), Narva river which ...

, by ship to Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin language, Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital city, capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the Po ...

, then by train to Vienna, where they arrived on 20 September. In early October Broz returned home to Kumrovec in what was then the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

to find that his mother had died and his father had moved to Jastrebarsko near Zagreb. Sources differ over whether Broz joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

while in Russia, but he stated that the first time he joined the Communist Party of Yugoslavia

The League of Communists of Yugoslavia, mk, Сојуз на комунистите на Југославија, Sojuz na komunistite na Jugoslavija known until 1952 as the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, sl, Komunistična partija Jugoslavije mk ...

(CPY) was in Zagreb after he returned to his homeland.

Interwar communist activity

Communist agitator

Upon his return home, Broz was unable to gain employment as a metalworker in Kumrovec, so he and his wife moved briefly to Zagreb, where he worked as a waiter, and took part in a waiter's strike. He also joined the CPY. The CPY's influence on the political life of Yugoslavia was growing rapidly. In the 1920 elections, it won 59 seats and became the third strongest party. After the assassination ofMilorad Drašković

Milorad Drašković ( sr-cyr, Милорад Драшковић; 10 April 1873 – 21 July 1921) was a Serbian politician who was the Minister of Internal Affairs of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

Death

On 21 July 1921 Alija Alijagi� ...

, the Yugoslav Minister of the Interior, by a young communist named Alija Alijagić

Alija Alijagić (20 November 1896 – 8 March 1922) was a Bosnian communist and assassin known for murdering Milorad Drašković, the Minister of the Interior of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

The Communist Party of Yugoslavia condemn ...

on 2 August 1921, the CPY was declared illegal under the Yugoslav State Security Act of 1921.

Due to his overt communist links, Broz was fired from his employment. He and his wife then moved to the village of Veliko Trojstvo

Veliko Trojstvo is a municipality in Bjelovar-Bilogora County, Croatia. There are a total of 2,741 inhabitants, in the following settlements:

* Ćurlovac, population 261

* Dominkovica, population 50

* Grginac, population 231

* Kegljevac, popu ...

where he worked as a mill mechanic. After the arrest of the CPY leadership in January 1922, Stevo Sabić took over control of its operations. Sabić contacted Broz who agreed to work illegally for the party, distributing leaflets and agitating among factory workers. In the contest of ideas between those that wanted to pursue moderate policies and those that advocated violent revolution, Broz sided with the latter. In 1924, Broz was elected to the CPY district committee, but after he gave a speech at a comrade's Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

funeral he was arrested when the priest complained. Paraded through the streets in chains, he was held for eight days and was eventually charged with creating a public disturbance. With the help of a Serbian Orthodox

The Serbian Orthodox Church ( sr-Cyrl, Српска православна црква, Srpska pravoslavna crkva) is one of the autocephalous (ecclesiastically independent) Eastern Orthodox Christian churches.

The majority of the population in ...

prosecutor who hated Catholics, Broz and his co-accused were acquitted. His brush with the law had marked him as a communist agitator, and his home was searched on an almost weekly basis. Since their arrival in Yugoslavia, Pelagija had lost three babies soon after their births, and one daughter, Zlatina, at the age of two. Broz felt the loss of Zlatina deeply. In 1924, Pelagija gave birth to a boy, Žarko, who survived. In mid-1925, Broz's employer died and the new mill owner gave him an ultimatum, give up his communist activities or lose his job. So, at the age of 33, Broz became a professional revolutionary.

Professional revolutionary

The CPY concentrated its revolutionary efforts on factory workers in the more industrialised areas of Croatia and Slovenia, encouraging strikes and similar action. In 1925, the now unemployed Broz moved toKraljevica

Kraljevica (known as ''Porto Re'' in Italian and literally translated as "King's cove" in English) is a town in the Kvarner region of Croatia, located between Rijeka and Crikvenica, approximately thirty kilometers from Opatija and near the entran ...

on the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) ...

coast, where he started working at a shipyard to further the aims of the CPY. During his time in Kraljevica, Tito acquired a love of the warm, sunny Adriatic coastline that was to last for the rest of his life, and throughout his later time as leader, he spent as much time as possible living on his yacht while cruising the Adriatic.

While at Kraljevica he worked on Yugoslav torpedo boats and a pleasure yacht for the People's Radical Party politician, Milan Stojadinović

Milan Stojadinović ( sr-Cyrl, Милан Стојадиновић; 4 August 1888 – 26 October 1961) was a Serbian and Yugoslav politician and economist who served as the Prime Minister of Yugoslavia from 1935 to 1939. He also served as Forei ...

. Broz built up the trade union organisation in the shipyards and was elected as a union representative

A union representative, union steward, or shop steward is an employee of an organization or company who represents and defends the interests of their fellow employees as a labor union member and official. Rank-and-file members of the union hold ...

. A year later he led a shipyard strike, and soon after was fired. In October 1926 he obtained work in a railway works in Smederevska Palanka near Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

. In March 1927, he wrote an article complaining about the exploitation of workers in the factory, and after speaking up for a worker he was promptly sacked. Identified by the CPY as worthy of promotion, he was appointed secretary of the Zagreb branch of the Metal Workers' Union, and soon after the whole Croatian branch of the union. In July 1927 Broz was arrested, along with six other workers, and imprisoned at nearby Ogulin. After being held without trial for some time, Broz went on a hunger strike until a date was set. The trial was held in secret and he was found guilty of being a member of the CPY. Sentenced to four months' imprisonment, he was released from prison pending an appeal. On the orders of the CPY, Broz did not report to the court for the hearing of the appeal, instead going into hiding in Zagreb. Wearing dark spectacles and carrying forged papers, Broz posed as a middle-class technician in the engineering industry, working undercover to contact other CPY members and coordinate their infiltration of trade unions.

In February 1928, Broz was one of 32 delegates to the conference of the Croatian branch of the CPY. During the conference, Broz condemned factions within the party. These included those that advocated a

In February 1928, Broz was one of 32 delegates to the conference of the Croatian branch of the CPY. During the conference, Broz condemned factions within the party. These included those that advocated a Greater Serbia

The term Greater Serbia or Great Serbia ( sr, Велика Србија, Velika Srbija) describes the Serbian nationalist and irredentist ideology of the creation of a Serb state which would incorporate all regions of traditional significance to S ...

agenda within Yugoslavia, like the long-term CPY leader, the Serb Sima Marković

Sima Marković (8 November 1888 in Kragujevac, Kingdom of Serbia – 19 April 1939 in Moscow, USSR) was a Serbian mathematician, communist and socialist politician and philosopher, known as one of the founders and first leaders of the Communist ...

. Broz proposed that the executive committee of the Communist International purge the branch of factionalism, and was supported by a delegate sent from Moscow. After it was proposed that the entire central committee of the Croatian branch be dismissed, a new central committee was elected with Broz as its secretary. Marković was subsequently expelled from the CPY at the Fourth Congress of the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

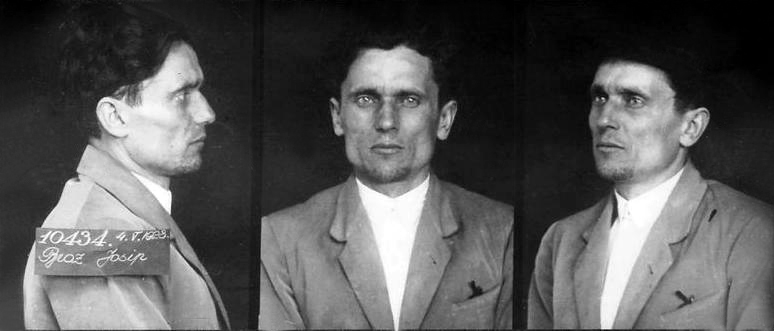

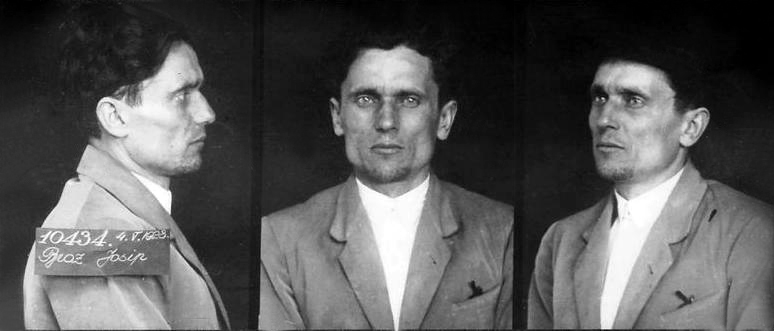

, and the CPY adopted a policy of working for the break-up of Yugoslavia. Broz arranged to disrupt a meeting of the Social-Democratic Party on May Day that year, and in a melee outside the venue, Broz was arrested by the police. They failed to identify him, charging him under his false name for a breach of the peace. He was imprisoned for 14 days and then released, returning to his previous activities. The police eventually tracked him down with the help of a police informer. He was ill-treated and held for three months before being tried in court in November 1928 for his illegal communist activities, which included allegations that the bombs that had been found at his address had been planted by the police. He was convicted and sentenced to five years' imprisonment.

Prison

After his sentencing, his wife and son returned to Kumrovec, where they were looked after by sympathetic locals, but then one day they suddenly left without explanation and returned to the Soviet Union. She fell in love with another man and Žarko grew up in institutions. After arriving at Lepoglava prison, Broz was employed in maintaining the electrical system, and chose as his assistant a middle-class Belgrade Jew,

After his sentencing, his wife and son returned to Kumrovec, where they were looked after by sympathetic locals, but then one day they suddenly left without explanation and returned to the Soviet Union. She fell in love with another man and Žarko grew up in institutions. After arriving at Lepoglava prison, Broz was employed in maintaining the electrical system, and chose as his assistant a middle-class Belgrade Jew, Moša Pijade

Moša Pijade ( sr-Cyrl, Мoшa Пијаде; he, משה פיאדה; alternate English transliteration Moshe Piade; 4 January 1890 – 15 March 1957), nicknamed Čiča Janko (, lit. "Old Man Janko") was a Serbian and Yugoslav communist of J ...

, who had been given a 20-year sentence for his communist activities. Their work allowed Broz and Pijade to move around the prison, contacting and organising other communist prisoners. During their time together in Lepoglava, Pijade became Broz's ideological mentor. After two and a half years at Lepoglava, Broz was accused of attempting to escape and was transferred to Maribor

Maribor ( , , , ; also known by other #Name, historical names) is the second-largest city in Slovenia and the largest city of the traditional region of Styria (Slovenia), Lower Styria. It is also the seat of the City Municipality of Maribor, th ...

prison where he was held in solitary confinement for several months. After completing the full term of his sentence, he was released, only to be arrested outside the prison gates and taken to Ogulin to serve the four-month sentence he had avoided in 1927. He was finally released from prison on 16 March 1934, but even then he was subject to orders that required him to live in Kumrovec and report to the police daily. During his imprisonment, the political situation in Europe had changed significantly, with the rise of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

in Germany and the emergence of right-wing parties in France and neighbouring Austria. He returned to a warm welcome in Kumrovec but did not stay for long. In early May, he received word from the CPY to return to his revolutionary activities, and left his home town for Zagreb, where he rejoined the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Croatia.

The Croatian branch of the CPY was in disarray, a situation exacerbated by the escape of the executive committee of the CPY to Vienna in Austria, from which they were directing activities. Over the next six months, Broz travelled several times between Zagreb, Ljubljana and Vienna, using false passports. In July 1934, he was blackmailed by a smuggler, but pressed on across the border, and was detained by the local '' Heimwehr'', a paramilitary Home Guard. He used the Austrian accent he had developed during his war service to convince them that he was a wayward Austrian mountaineer, and they allowed him to proceed to Vienna. Once there, he contacted the General Secretary of the CPY, Milan Gorkić, who sent him to Ljubljana to arrange a secret conference of the CPY in Slovenia. The conference was held at the summer palace of the Roman Catholic bishop of Ljubljana, whose brother was a communist sympathiser. It was at this conference that Broz first met Edvard Kardelj

Edvard Kardelj (; 27 January 1910 – 10 February 1979), also known by the pseudonyms Bevc, Sperans and Krištof, was a Yugoslav politician and economist. He was one of the leading members of the Communist Party of Slovenia before World War II. ...

, a young Slovene communist who had recently been released from prison. Broz and Kardelj subsequently became good friends, with Tito later regarding him as his most reliable deputy. As he was wanted by the police for failing to report to them in Kumrovec, Broz adopted various pseudonyms, including "Rudi" and "Tito". He used the latter as a pen name when he wrote articles for party journals in 1934, and it stuck. He gave no reason for choosing the name "Tito" except that it was a common nickname for men from the district where he grew up. Within the Comintern network, his nickname was "Walter".

Flight from Yugoslavia

During this time Tito wrote articles on the duties of imprisoned communists and on trade unions. He was in Ljubljana when King Alexander was assassinated by Vlado Chernozemski and the Croatian nationalist ''

During this time Tito wrote articles on the duties of imprisoned communists and on trade unions. He was in Ljubljana when King Alexander was assassinated by Vlado Chernozemski and the Croatian nationalist ''Ustaše

The Ustaše (), also known by anglicised versions Ustasha or Ustashe, was a Croats, Croatian Fascism, fascist and ultranationalism, ultranationalist organization active, as one organization, between 1929 and 1945, formally known as the Ustaš ...

'' organisation in Marseilles on 9 October 1934. In the crackdown on dissidents that followed his death, it was decided that Tito should leave Yugoslavia. He travelled to Vienna on a forged Czech passport where he joined Gorkić and the rest of the Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contraction ...

of the CPY. It was decided that the Austrian government was too hostile to communism, so the Politburo travelled to Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

in Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, and Tito accompanied them. On Christmas Day 1934, a secret meeting of the Central Committee of the CPY was held in Ljubljana, and Tito was elected as a member of the Politburo for the first time. The Politburo decided to send him to Moscow to report on the situation in Yugoslavia, and in early February 1935, he arrived there as a full-time official of the Comintern. He lodged at the main Comintern residence, the Hotel Lux

The former Hotel Lux in Moscow

Hotel Lux (Люксъ) was a hotel in Moscow during the Soviet Union, housing many leading exiled and visiting Communists. During the Nazi era, exiles from all over Europe went there, particularly from Germany. A n ...

on Tverskaya Street, and was quickly in contact with Vladimir Ćopić

Vladimir "Senjko" Ćopić (8 March 1891 – 19 April 1939) was a Yugoslav revolutionary, politician, journalist and communist leader of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia from April 1919 to August 1920.

Biography

Born into a family of mixed Croat a ...

, one of the leading Yugoslavs with the Comintern. He was soon introduced to the main personalities in the organisation. Tito was appointed to the secretariat of the Balkan section, responsible for Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania and Greece. Kardelj was also in Moscow, as was the Bulgarian communist leader Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov Mihaylov (; bg, Гео̀рги Димитро̀в Миха̀йлов), also known as Georgiy Mihaylovich Dimitrov (russian: Гео́ргий Миха́йлович Дими́тров; 18 June 1882 – 2 July 1949), was a Bulgarian ...

. Tito lectured on trade unions to foreign communists, and attended a course on military tactics run by the Red Army, and occasionally attended the Bolshoi Theatre

The Bolshoi Theatre ( rus, Большо́й теа́тр, r=Bol'shoy teatr, literally "Big Theater", p=bɐlʲˈʂoj tʲɪˈatər) is a historic theatre in Moscow, Russia, originally designed by architect Joseph Bové, which holds ballet and ope ...

. He attended as one of 510 delegates to the Seventh World Congress of the Comintern in July and August 1935, where he briefly saw Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

for the first time. After the congress, he toured the Soviet Union, then returned to Moscow to continue his work. He contacted Polka and Žarko, but soon fell in love with an Austrian woman who worked at the Hotel Lux, Johanna Koenig, known within communist ranks as Lucia Bauer. When she became aware of this liaison, Polka divorced Tito in April 1936. Tito married Bauer on 13 October of that year.

After the World Congress, Tito worked to promote the new Comintern line on Yugoslavia, which was that it would no longer work to break up the country, and would instead defend the integrity of Yugoslavia against Nazism and Fascism. From a distance, Tito also worked to organise strikes at the shipyards at Kraljevica and the coal mines at Trbovlje near Ljubljana. He tried to convince the Comintern that it would be better if the party leadership was located inside Yugoslavia. A compromise was arrived at, where Tito and others would work inside the country and Gorkić and the Politburo would continue to work from abroad. Gorkić and the Politburo relocated to Paris, while Tito began to travel between Moscow, Paris and Zagreb in 1936 and 1937, using false passports. In 1936, his father died.

Tito returned to Moscow in August 1936, soon after the outbreak of the

Tito returned to Moscow in August 1936, soon after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

. At the time, the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

was underway, and foreign communists like Tito and his Yugoslav compatriots were particularly vulnerable. Despite a laudatory report written by Tito about the veteran Yugoslav communist Filip Filipović, Filipović was arrested and shot by the Soviet secret police, the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

. However, before the Purge really began to erode the ranks of the Yugoslav communists in Moscow, Tito was sent back to Yugoslavia with a new mission, to recruit volunteers

Volunteering is a voluntary act of an individual or group freely giving time and labor for community service. Many volunteers are specifically trained in the areas they work, such as medicine, education, or emergency rescue. Others serve ...

for the International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed f ...

being raised to fight on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War. Travelling via Vienna, he reached the coastal port city of Split in December 1936. According to the Croatian historian Ivo Banac

Ivo Banac (; 1 March 1947 – 30 June 2020) was a Croatian-American historian, a professor of European history at Yale University and a politician of the former Liberal Party in Croatia, known as the Great Bard of Croatian historiography. , Banac ...

, the reason Tito was sent back to Yugoslavia by the Comintern was in order to purge the CPY. An initial attempt to send 500 volunteers to Spain by ship failed utterly, with nearly all the communist volunteers being arrested and imprisoned. Tito then travelled to Paris, where he arranged the travel of volunteers to France under the cover of attending the Paris Exhibition

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

. Once in France, the volunteers simply crossed the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to C ...

to Spain. In all, he sent 1,192 men to fight in the war, but only 330 came from Yugoslavia, the rest being expatriates in France, Belgium, the U.S. and Canada. Less than half were communists, and the rest were social-democrats and anti-fascists of various hues. Of the total, 671 were killed in the fighting and another 300 were wounded. Tito himself never went to Spain, despite later claims that he had. Between May and August 1937, Tito travelled several times between Paris and Zagreb organising the movement of volunteers and creating a separate Communist Party of Croatia. The new party was inaugurated at a conference at Samobor

Samobor () is a city in Zagreb County, Croatia. It is part of the Zagreb metropolitan area. Administratively it is a part of Zagreb County.

Geography

Samobor is located west of Zagreb, between the eastern slopes of the Samobor hills ( hr, Samo ...

on the outskirts of Zagreb on 1–2 August 1937.

General Secretary of the CPY

In June 1937, Gorkić was summoned to Moscow, where he was arrested, and after months of NKVD interrogation, he was shot. According to Banac, Gorkić was killed on Stalin's orders. West concludes that despite being in competition with men like Gorkić for the leadership of the CPY, it was not in Tito's character to have innocent people sent to their deaths. Tito then received a message from the Politburo of the CPY to join them in Paris. In August 1937 he became acting General Secretary of the CPY. He later explained that he survived the Purge by staying out of Spain where the NKVD was active, and also by avoiding visiting the Soviet Union as much as possible. When first appointed as general secretary, he avoided travelling to Moscow by insisting that he needed to deal with some indiscipline in the CPY in Paris. He also promoted the idea that the upper echelons of the CPY should be sharing the dangers of underground resistance within the country. He developed a new, younger leadership team that was loyal to him, including the Slovene Kardelj, the Serb, Aleksandar Ranković, and the Montenegrin,Milovan Đilas

Milovan Djilas (; , ; 12 June 1911 – 30 April 1995) was a Yugoslav communist politician, theorist and author. He was a key figure in the Partisan movement during World War II, as well as in the post-war government. A self-identified democrat ...

. In December 1937, Tito arranged for a demonstration to greet the French foreign minister when he visited Belgrade, expressing solidarity with the French against Nazi Germany. The protest march numbered 30,000 and turned into a protest against the neutrality policy of the Stojadinović government. It was eventually broken up by the police. In March 1938 Tito returned to Yugoslavia from Paris. Hearing a rumour that his opponents within the CPY had tipped off the police, he travelled to Belgrade rather than Zagreb and used a different passport. While in Belgrade he stayed with a young intellectual, Vladimir Dedijer

Vladimir Dedijer ( sr-Cyrl, Владимир Дедијер; 4 February 1914 – 30 November 1990) was a Yugoslav partisan fighter during World War II who became known as a politician, human rights activist, and historian. In the early postwar ye ...

, who was a friend of Đilas. Arriving in Yugoslavia a few days ahead of the ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

'' between Nazi Germany and Austria, he made an appeal condemning it, in which the CPY was joined by the Social Democrats and trade unions. In June, Tito wrote to the Comintern suggesting that he should visit Moscow. He waited in Paris for two months for his Soviet visa before travelling to Moscow via Copenhagen. He arrived in Moscow on 24 August.

On arrival in Moscow, he found that all Yugoslav communists were under suspicion. Nearly all the most prominent leaders of the CPY were arrested by the NKVD and executed, including over twenty members of the Central Committee. Both his ex-wife Polka and his wife Koenig/Bauer were arrested as "imperialist spies", although they were both eventually released, Polka after 27 months in prison. Tito, therefore, needed to make arrangements for the care of Žarko, who was fourteen. He placed him in a boarding school outside

On arrival in Moscow, he found that all Yugoslav communists were under suspicion. Nearly all the most prominent leaders of the CPY were arrested by the NKVD and executed, including over twenty members of the Central Committee. Both his ex-wife Polka and his wife Koenig/Bauer were arrested as "imperialist spies", although they were both eventually released, Polka after 27 months in prison. Tito, therefore, needed to make arrangements for the care of Žarko, who was fourteen. He placed him in a boarding school outside Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

, then at a school at Penza, but he ran away twice and was eventually taken in by a friend's mother. In 1941, Žarko joined the Red Army to fight the invading Germans. Some of Tito's critics argue that his survival indicates he must have denounced his comrades as Trotskyists. He was asked for information on a number of his fellow Yugoslav communists, but according to his own statements and published documents, he never denounced anyone, usually saying he did not know them. In one case he was asked about the Croatian communist leader Horvatin, but wrote ambiguously, saying that he did not know whether he was a Trotskyist. Nevertheless, Horvatin was not heard of again. While in Moscow, he was given the task of assisting Ćopić to translate the ''History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks)'' into Serbo-Croatian

Serbo-Croatian () – also called Serbo-Croat (), Serbo-Croat-Bosnian (SCB), Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian (BCS), and Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian (BCMS) – is a South Slavic language and the primary language of Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and ...

, but they had only got to the second chapter when Ćopić too was arrested and executed. He worked on with a fellow surviving Yugoslav communist, but a Yugoslav communist of German ethnicity reported an inaccurate translation of a passage and claimed it showed Tito was a Trotskyist. Other influential communists vouched for him, and he was exonerated. He was denounced by a second Yugoslav communist, but the action backfired and his accuser was arrested. Several factors were at play in his survival; working-class origins, lack of interest in intellectual arguments about socialism, attractive personality and capacity for making influential friends.

While Tito was avoiding arrest in Moscow, Germany was placing pressure on Czechoslovakia to cede the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

. In response to this threat, Tito organised a call for Yugoslav volunteers to fight for Czechoslovakia, and thousands of volunteers came to the Czechoslovak embassy in Belgrade to offer their services. Despite the eventual Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

and Czechoslovak acceptance of the annexation and the fact that the volunteers were turned away, Tito claimed credit for the Yugoslav response, which worked in his favour. By this stage, Tito was well aware of the realities in the Soviet Union, later stating that he "witnessed a great many injustices", but was too heavily invested in communism and too loyal to the Soviet Union to step back at this point. Tito's appointment as General Secretary of the CPY was formally ratified by the Comintern on 5 January 1939.

He was appointed to the Committee and started to appoint allies to him, among them Edvard Kardelj

Edvard Kardelj (; 27 January 1910 – 10 February 1979), also known by the pseudonyms Bevc, Sperans and Krištof, was a Yugoslav politician and economist. He was one of the leading members of the Communist Party of Slovenia before World War II. ...

, Milovan Đilas

Milovan Djilas (; , ; 12 June 1911 – 30 April 1995) was a Yugoslav communist politician, theorist and author. He was a key figure in the Partisan movement during World War II, as well as in the post-war government. A self-identified democrat ...

, Aleksandar Ranković and Boris Kidrič

Boris Kidrič (10 April 1912 – 11 April 1953) was a Slovene politician and revolutionary who was one of the chief organizers of the Slovene Partisans, the Slovene resistance against occupation by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy after Operatio ...

.

World War II

Resistance in Yugoslavia

On 6 April 1941, Axis forces invaded Yugoslavia. On 10 April 1941,

On 6 April 1941, Axis forces invaded Yugoslavia. On 10 April 1941, Slavko Kvaternik

Slavko Kvaternik (25 August 1878 – 7 June 1947) was a Croatian Ustaše military general and politician who was one of the founders of the Ustaše movement. Kvaternik was military commander and Minister of '' Domobranstvo'' (''Armed Forces''). O ...

proclaimed the Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia ( sh, Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH; german: Unabhängiger Staat Kroatien; it, Stato indipendente di Croazia) was a World War II-era puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Fascist It ...

, and Tito responded by forming a Military Committee within the Central Committee of the Yugoslav Communist Party. Attacked from all sides, the armed forces of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 unt ...

quickly crumbled. On 17 April 1941, after King Peter II and other members of the government fled the country, the remaining representatives of the government and military met with German officials in Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

. They quickly agreed to end military resistance. Prominent communist leaders, including Tito, held the May consultations The May consultations were an underground gathering of the Central Committee (Politburo) of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPY) and leaders of its regional branches held after World War II in Yugoslavia started, on the initiative of Josip Broz T ...