President Chester Arthur on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

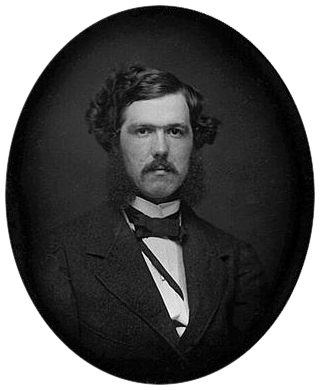

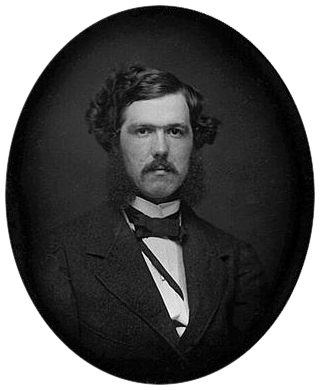

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 21st

Chester Alan Arthur was born in Fairfield, Vermont. Arthur's mother, Malvina Stone was born in Berkshire, Vermont, the daughter of George Washington Stone and Judith Stevens. Her family was primarily of

Chester Alan Arthur was born in Fairfield, Vermont. Arthur's mother, Malvina Stone was born in Berkshire, Vermont, the daughter of George Washington Stone and Judith Stevens. Her family was primarily of

After graduating in 1848, Arthur returned to Schaghticoke and became a full-time teacher, and soon began to pursue an education in law. While studying law, he continued teaching, moving closer to home by taking a job at a school in

After graduating in 1848, Arthur returned to Schaghticoke and became a full-time teacher, and soon began to pursue an education in law. While studying law, he continued teaching, moving closer to home by taking a job at a school in

When Arthur joined the firm, Culver and New York attorney

When Arthur joined the firm, Culver and New York attorney

The end of the Civil War meant new opportunities for the men in Morgan's Republican

The end of the Civil War meant new opportunities for the men in Morgan's Republican

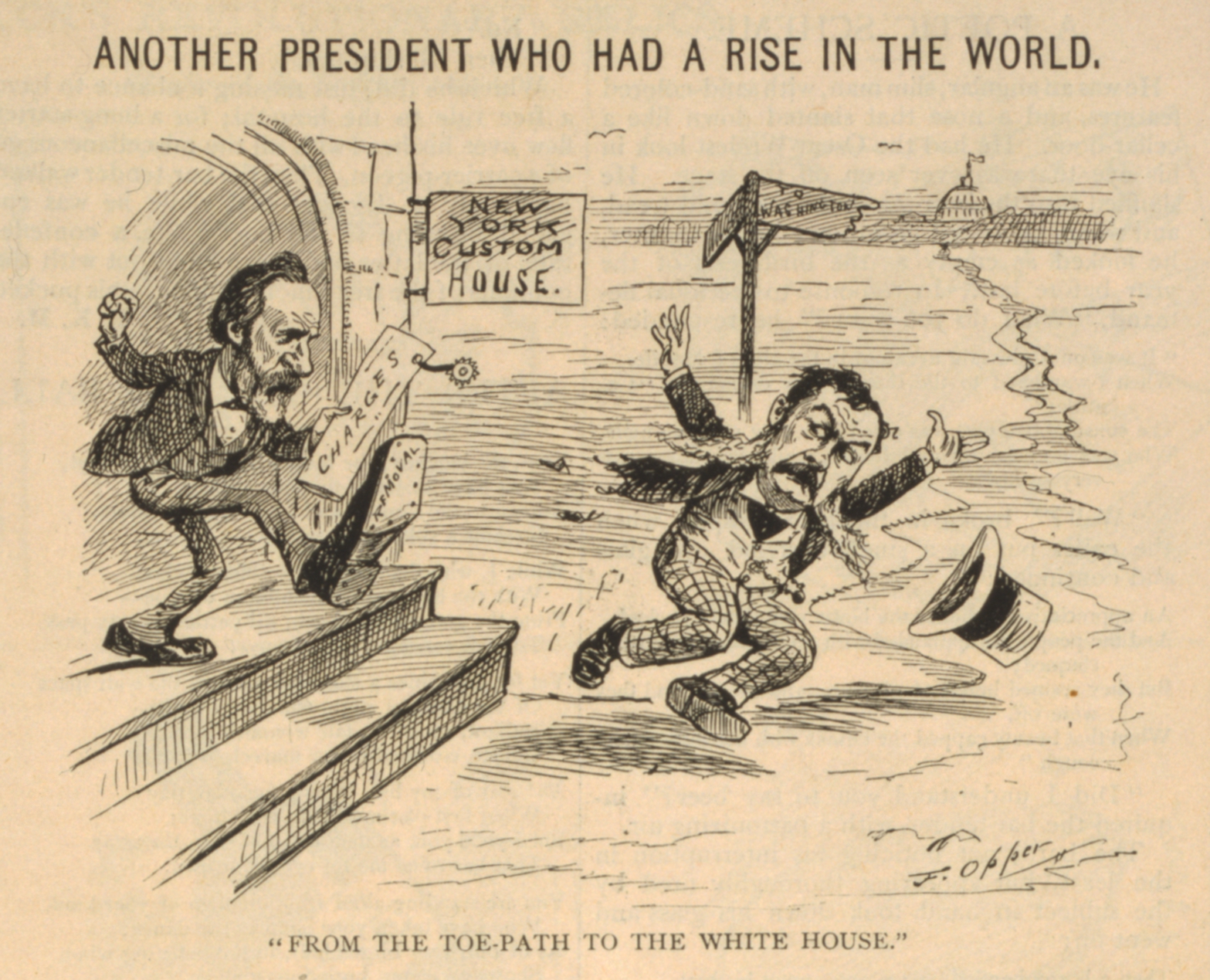

Arthur's four-year term as Collector expired on December 10, 1875, and Conkling, then among the most powerful politicians in Washington, arranged his protégé's reappointment by President Grant. In 1876, Conkling was a candidate for president at the

Arthur's four-year term as Collector expired on December 10, 1875, and Conkling, then among the most powerful politicians in Washington, arranged his protégé's reappointment by President Grant. In 1876, Conkling was a candidate for president at the

Conkling and his fellow Stalwarts, including Arthur, wished to follow up their 1879 success at the

Conkling and his fellow Stalwarts, including Arthur, wished to follow up their 1879 success at the  With the war fifteen years in the past and Union generals at the head of both tickets, the tactic was less effective than the Republicans hoped. Realizing this, they adjusted their approach to claim that Democrats would lower the country's

With the war fifteen years in the past and Union generals at the head of both tickets, the tactic was less effective than the Republicans hoped. Realizing this, they adjusted their approach to claim that Democrats would lower the country's

After the election, Arthur worked in vain to persuade Garfield to fill certain positions with his fellow New York Stalwarts—especially that of the Secretary of the Treasury; the Stalwart machine received a further rebuke when Garfield appointed Blaine, Conkling's arch-enemy, as Secretary of State. The running mates, never close, detached as Garfield continued to freeze out the Stalwarts from his patronage. Arthur's status in the administration diminished when, a month before inauguration day, he gave a speech before reporters suggesting the election in Indiana, a

After the election, Arthur worked in vain to persuade Garfield to fill certain positions with his fellow New York Stalwarts—especially that of the Secretary of the Treasury; the Stalwart machine received a further rebuke when Garfield appointed Blaine, Conkling's arch-enemy, as Secretary of State. The running mates, never close, detached as Garfield continued to freeze out the Stalwarts from his patronage. Arthur's status in the administration diminished when, a month before inauguration day, he gave a speech before reporters suggesting the election in Indiana, a

Arthur's sister,

Arthur's sister,

In the 1870s, a

In the 1870s, a  At first, the act applied only to 10% of federal jobs and, without proper implementation by the president, it could have gone no further. Even after he signed the act into law, its proponents doubted Arthur's commitment to reform. To their surprise, he acted quickly to appoint the members of the Civil Service Commission that the law created, naming reformers

At first, the act applied only to 10% of federal jobs and, without proper implementation by the president, it could have gone no further. Even after he signed the act into law, its proponents doubted Arthur's commitment to reform. To their surprise, he acted quickly to appoint the members of the Civil Service Commission that the law created, naming reformers

During the

During the

In the years following the Civil War, American naval power declined precipitously, shrinking from nearly 700 vessels to just 52, most of which were obsolete. The nation's military focus over the fifteen years before Garfield and Arthur's election had been on the Indian wars in the

In the years following the Civil War, American naval power declined precipitously, shrinking from nearly 700 vessels to just 52, most of which were obsolete. The nation's military focus over the fifteen years before Garfield and Arthur's election had been on the Indian wars in the

Like his Republican predecessors, Arthur struggled with the question of how his party was to challenge the Democrats in the South and how, if at all, to protect the civil rights of black southerners. Since the end of

Like his Republican predecessors, Arthur struggled with the question of how his party was to challenge the Democrats in the South and how, if at all, to protect the civil rights of black southerners. Since the end of

The Arthur administration was challenged by changing relations with western Native American tribes. The American Indian Wars were winding down, and public sentiment was shifting toward more favorable treatment of Native Americans. Arthur urged Congress to increase funding for Native American education, which it did in 1884, although not to the extent he wished. He also favored a move to the

The Arthur administration was challenged by changing relations with western Native American tribes. The American Indian Wars were winding down, and public sentiment was shifting toward more favorable treatment of Native Americans. Arthur urged Congress to increase funding for Native American education, which it did in 1884, although not to the extent he wished. He also favored a move to the

Shortly after becoming president, Arthur was diagnosed with Bright's disease, a

Shortly after becoming president, Arthur was diagnosed with Bright's disease, a

Arthur left office in 1885 and returned to his New York City home. Two months before the end of his term, several New York Stalwarts approached him to request that he run for United States Senate, but he declined, preferring to return to his old law practice at Arthur, Knevals & Ransom. His health limited his activity with the firm, and Arthur served only of counsel. He took on few assignments with the firm and was often too ill to leave his house. He managed a few public appearances until the end of 1885.

Arthur left office in 1885 and returned to his New York City home. Two months before the end of his term, several New York Stalwarts approached him to request that he run for United States Senate, but he declined, preferring to return to his old law practice at Arthur, Knevals & Ransom. His health limited his activity with the firm, and Arthur served only of counsel. He took on few assignments with the firm and was often too ill to leave his house. He managed a few public appearances until the end of 1885.

After spending the summer of 1886 in

After spending the summer of 1886 in

online complete

old, factual and heavily political, by winner of Pulitzer Prize * * * *

White House biography

* * *

Essays on Chester Arthur and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady

from the

Chester Arthur: A Resource Guide

from the

"Life Portrait of Chester A. Arthur"

from

"Life and Career of Chester A. Arthur"

presentation by

''Chester A. Arthur's Presidency''

a video by

''Remarks at the Grave of Chester Alan Arthur, Albany Rural Cemetery, October 5, 2019'' by historian David Pietrusza">''Remarks at the Grave of Chester Alan Arthur, Albany Rural Cemetery, October 5, 2019'' by historian David Pietrusza

Chester A. Arthur's Personal Manuscripts

fro

Shapell.org

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Arthur, Chester A. 1829 births">Chester A. Arthur"> 1829 births 1880 United States vice-presidential candidates 1886 deaths 19th-century American Episcopalians 19th-century American politicians 19th-century presidents of the United States American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law American people of English descent American people of Scotch-Irish descent American people of Scottish descent American people of Welsh descent Arthur family Burials at Albany Rural Cemetery Candidates in the 1884 United States presidential election Collectors of the Port of New York Garfield administration cabinet members Grand Army of the Republic officials New York (state) Republicans New York (state) Whigs New York (state) lawyers People from Cohoes, New York People from Fairfield, Vermont People from Schaghticoke, New York People of Vermont in the American Civil War Presidents of the United States Republican Party (United States) vice presidential nominees Republican Party presidents of the United States Republican Party vice presidents of the United States Stalwarts (Republican Party) State and National Law School alumni Union Army generals Union College (New York) alumni Vice presidents of the United States

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

from 1881 to 1885. He previously served as the 20th vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on t ...

under President James A. Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

. Arthur succeeded the presidency upon Garfield's death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

in September 1881—two months after being shot by an assassin.

Arthur was born in Fairfield, Vermont, grew up in upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region consisting of the area of New York State that lies north and northwest of the New York City metropolitan area. Although the precise boundary is debated, Upstate New York excludes New York City and Long Is ...

and practiced law in New York City. He served as quartermaster general of the New York Militia

The New York Guard (NYG) is the State Defense Force, state defense force of New York State, also called The New York State Military Reserve. Originally called the New York State Militia it can trace its lineage back to the American Revolution and ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

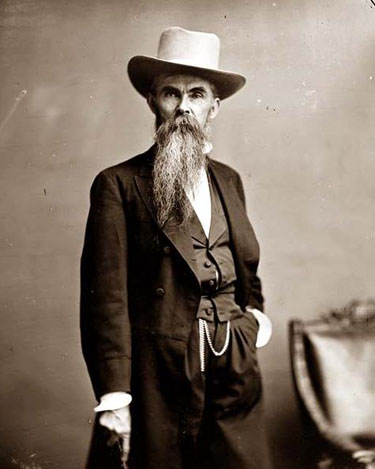

. Following the war, he devoted more time to New York Republican politics and quickly rose in Senator Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican Party (United States), Republican politician who represented New York (state), New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Se ...

's political organization. President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

appointed him to the post of Collector of the Port of New York in 1871, and he was an important supporter of Conkling and the Stalwart

Stalwart is an adjective synonymous with ''"strong"''. It may also refer to:

Relating to people:

* Stalwart (politics), member of the most patronage-oriented faction of the United States Republican Party in the late 19th century

In ships and mil ...

faction of the Republican Party. In 1878, President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

fired Arthur as part of a plan to reform the federal patronage system in New York. Garfield won the Republican nomination for president in 1880

Events

January–March

* January 22 – Toowong State School is founded in Queensland, Australia.

* January – The international White slave trade affair scandal in Brussels is exposed and attracts international infamy.

* February � ...

, and Arthur was nominated for vice president to balance the ticket as an Eastern Stalwart. Four months into his term, Garfield was shot by an assassin; he died 11 weeks later, and Arthur assumed the presidency.

At the outset, Arthur struggled to overcome a negative reputation as a Stalwart and product of Conkling's organization. To the surprise of reformers, he advocated and enforced the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act is a United States federal law passed by the 47th United States Congress and signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur on January 16, 1883. The act mandates that most positions within the federal governm ...

. He presided over the rebirth

Rebirth may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Film

* ''Rebirth'' (2011 film), a 2011 Japanese drama film

* ''Rebirth'' (2016 film), a 2016 American thriller film

* ''Rebirth'', a documentary film produced by Project Rebirth

* ''The Re ...

of the US Navy, but he was criticized for failing to alleviate the federal budget surplus which had been accumulating since the end of the Civil War. Arthur vetoed the first version of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplom ...

, arguing that its twenty-year ban on Chinese immigrants to the United States violated the Burlingame Treaty, but he signed a second version, which included a ten-year ban.

Suffering from poor health, Arthur made only a limited effort to secure the Republican Party's nomination in 1884, and he retired at the end of his term. Arthur's failing health and political temperament combined to make his administration less active than a modern presidency, yet he earned praise among contemporaries for his solid performance in office. Journalist Alexander McClure wrote, "No man ever entered the Presidency so profoundly and widely distrusted as Chester Alan Arthur, and no one ever retired ... more generally respected, alike by political friend and foe."

The ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under publi ...

'' summed up Arthur's presidency at his death in 1886: "No duty was neglected in his administration, and no adventurous project alarmed the nation." Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

wrote of him, "It would be hard indeed to better President Arthur's administration." Despite this, modern historians generally describe Arthur's presidency as mediocre or average

In ordinary language, an average is a single number taken as representative of a list of numbers, usually the sum of the numbers divided by how many numbers are in the list (the arithmetic mean). For example, the average of the numbers 2, 3, 4, 7, ...

, and Arthur as one of the least memorable presidents.

Early life

Birth and family

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

and Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

descent, and her maternal grandfather, Uriah Stone, had served in the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

during the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

.

Arthur's father, William Arthur, was born in 1796 in Dreen, Cullybackey

Cullybackey or Cullybacky () is a large village in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It lies 3 miles north-west of Ballymena, on the banks of the River Main, and is part of Mid and East Antrim district. It had a population of 2,569 people in the 2 ...

, County Antrim

County Antrim (named after the town of Antrim, ) is one of six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of and has a population o ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

to a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

family of Scots-Irish descent. William's mother was born Eliza McHarg and she married Alan Arthur. William graduated from college in Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

and immigrated to the Province of Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada (french: province du Bas-Canada) was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (1791–1841). It covered the southern portion of the current Province of Quebec and ...

in 1819 or 1820. Malvina Stone met William Arthur when Arthur was teaching school in Dunham, Quebec, near the Vermont border. They married in Dunham on April 12, 1821, soon after meeting.

The Arthurs moved to Vermont after the birth of their first child, Regina. They quickly moved from Burlington

Burlington may refer to:

Places Canada Geography

* Burlington, Newfoundland and Labrador

* Burlington, Nova Scotia

* Burlington, Ontario, the most populous city with the name "Burlington"

* Burlington, Prince Edward Island

* Burlington Bay, no ...

to Jericho

Jericho ( ; ar, أريحا ; he, יְרִיחוֹ ) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank. It is located in the Jordan Valley, with the Jordan River to the east and Jerusalem to the west. It is the administrative seat of the Jericho Gove ...

, and finally to Waterville, as William received positions teaching at different schools. William Arthur also spent a brief time studying law, but while still in Waterville, he departed from both his legal studies and his Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

upbringing to join the Free Will Baptists; he spent the rest of his life as a minister in that sect. William Arthur became an outspoken abolitionist, which often made him unpopular with some members of his congregations and contributed to the family's frequent moves.

In 1828, the family moved again, to Fairfield, where Chester Alan Arthur was born the following year; he was the fifth of nine children. He was named "Chester" after Chester Abell, the physician and family friend who assisted in his birth, and "Alan" for his paternal grandfather. The family remained in Fairfield until 1832, when William Arthur's profession took them to churches in several towns in Vermont and upstate New York. The family finally settled in the Schenectady, New York

Schenectady () is a city in Schenectady County, New York, United States, of which it is the county seat. As of the 2020 census, the city's population of 67,047 made it the state's ninth-largest city by population. The city is in eastern New Y ...

area.

Arthur had seven siblings who lived to adulthood:

* Regina (1822–1910), the wife of William G. Caw, a grocer, banker, and community leader of Cohoes, New York who served as town supervisor

The administrative divisions of New York are the various units of government that provide local services in the State of New York. The state is divided into boroughs, counties, cities, townships called "towns", and villages. (The only borou ...

and village trustee

* Jane (1824–1842)

* Almeda (1825–1899), the wife of James H. Masten who served as postmaster of Cohoes and publisher of the ''Cohoes Cataract'' newspaper

* Ann (1828–1915), a career educator who taught school in New York and worked in South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

in the years immediately before and after the Civil War.

* Malvina (1832–1920), the wife of Henry J. Haynesworth who was an official of the Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

government and a merchant in Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York City ...

before being appointed as a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

and assistant quartermaster

Quartermaster is a military term, the meaning of which depends on the country and service. In land armies, a quartermaster is generally a relatively senior soldier who supervises stores or barracks and distributes supplies and provisions. In m ...

in the U.S. Army during Arthur's presidency

* William (1834–1915), a medical school graduate who became a career Army officer and paymaster, he was wounded during his Civil War service. William Arthur retired in 1898 with the brevet rank of lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

, and permanent rank of major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

.

* George (1836–1838)

* Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

(1841–1917), the wife of John E. McElroy, an Albany businessman and insurance executive, and Arthur's official White House hostess during his presidency

The family's frequent moves later spawned accusations that Arthur was not a native-born citizen of the United States. When Arthur was nominated for vice president in 1880, a New York attorney and political opponent, Arthur P. Hinman, initially speculated that Arthur was born in Ireland and did not come to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

until he was fourteen years old. Had that been true, opponents might have argued that Arthur was ineligible for the vice presidency under the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

's natural-born-citizen clause

A natural-born-citizen clause, if present in the constitution of a country, requires that its president or vice president be a natural born citizen. The constitutions of a number of countries contain such a clause, but there is no universally ac ...

. When Hinman's original story did not take root, he spread a new rumor that Arthur was born in Canada. This claim, too, failed to gain credence.

Education

Arthur spent some of his childhood years living in the New York towns ofYork

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, Perry

Perry, also known as pear cider, is an alcoholic beverage made from fermented pears, traditionally the perry pear. It has been common for centuries in England, particularly in Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, and Worcestershire. It is also made ...

, Greenwich, Lansingburgh

Lansingburgh was a village in the north end of Troy. It was first laid out in lots and incorporated in 1771 by Abraham Jacob Lansing, who had purchased the land in 1763. In 1900, Lansingburgh became part of the City of Troy.

Demographics

Lansi ...

, Schenectady

Schenectady () is a city in Schenectady County, New York, United States, of which it is the county seat. As of the 2020 census, the city's population of 67,047 made it the state's ninth-largest city by population. The city is in eastern New Y ...

, and Hoosick. One of his first teachers said Arthur was a boy "frank and open in manners and genial in disposition." During his time at school, he gained his first political inclinations and supported the Whig Party. He joined other young Whigs in support of Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, al ...

, even participating in a brawl against students who supported James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

during the 1844 United States presidential election

The 1844 United States presidential election was the 15th quadrennial United States presidential election, presidential election, held from Friday, November 1 to Wednesday, December 4, 1844. History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democr ...

. Arthur also supported the Fenian Brotherhood, an Irish republican

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The develop ...

organization founded in America; he showed this support by wearing a green coat. After completing his college preparation at the Lyceum of Union Village (now Greenwich) and a grammar school in Schenectady, Arthur enrolled at Union College

Union College is a private liberal arts college in Schenectady, New York. Founded in 1795, it was the first institution of higher learning chartered by the New York State Board of Regents, and second in the state of New York, after Columbia Co ...

there in 1845, where he studied the traditional classical curriculum. He was a member of the Psi Upsilon

Psi Upsilon (), commonly known as Psi U, is a North American fraternity,''Psi Upsilon Tablet'' founded at Union College on November 24, 1833. The fraternity reports 50 chapters at colleges and universities throughout North America, some of which ...

fraternity

A fraternity (from Latin language, Latin ''wiktionary:frater, frater'': "brother (Christian), brother"; whence, "wiktionary:brotherhood, brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club (organization), club or fraternal ...

, and as a senior

Senior (shortened as Sr.) means "the elder" in Latin and is often used as a suffix for the elder of two or more people in the same family with the same given name, usually a parent or grandparent. It may also refer to:

* Senior (name), a surname ...

he was president of the debate society and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal a ...

. During his winter breaks, he served as a teacher at a school in Schaghticoke.

After graduating in 1848, Arthur returned to Schaghticoke and became a full-time teacher, and soon began to pursue an education in law. While studying law, he continued teaching, moving closer to home by taking a job at a school in

After graduating in 1848, Arthur returned to Schaghticoke and became a full-time teacher, and soon began to pursue an education in law. While studying law, he continued teaching, moving closer to home by taking a job at a school in North Pownal, Vermont

North Pownal is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in the town of Pownal, Bennington County, Vermont, United States. It was first listed as a CDP prior to the 2020 census.

It is in southwestern Bennington County, in th ...

. Coincidentally, future president James A. Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

taught penmanship at the same school three years later, but the two did not cross paths during their teaching careers. In 1852, Arthur moved again, to Cohoes, New York, to become the principal of a school at which his sister, Malvina, was a teacher. In 1853, after studying at State and National Law School

The State and National Law School was an early practical training law school founded in 1849 by John W. Fowler in Ballston Spa, New York (Saratoga County). It was also known as New York State and National Law School, Ballston Law School, and Fowl ...

in Ballston Spa, New York, and then saving enough money to relocate, Arthur moved to New York City to read law

Reading law was the method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship under the ...

at the office of Erastus D. Culver

Erastus Dean Culver (March 15, 1803 – October 13, 1889) was an attorney, politician, judge, and diplomat from New York City.

Culver was active in the anti-slavery movement and, while in Congress in the 1840s, opposed the extension of sla ...

, an abolitionist lawyer and family friend. When Arthur was admitted to the New York bar in 1854, he joined Culver's firm, which was subsequently renamed Culver, Parker, and Arthur.

Early career

New York lawyer

When Arthur joined the firm, Culver and New York attorney

When Arthur joined the firm, Culver and New York attorney John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the first ...

(the grandson of the Founding Father John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the first ...

) were pursuing a ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

'' action against Jonathan Lemmon, a Virginia slaveholder who was passing through New York with his eight slaves. In ''Lemmon v. New York

''Lemmon v. New York'', or ''Lemmon v. The People'' (1860), popularly known as the Lemmon Slave Case, was a freedom suit initiated in 1852 by a petition for a writ of ''habeas corpus''. The petition was granted by the Superior Court in New York ...

'', Culver argued that, as New York law did not permit slavery, any slave arriving in New York was automatically freed. The argument was successful, and after several appeals was upheld by the New York Court of Appeals

The New York Court of Appeals is the highest court in the Unified Court System of the State of New York. The Court of Appeals consists of seven judges: the Chief Judge and six Associate Judges who are appointed by the Governor and confirmed by t ...

in 1860. Campaign biographers would later give Arthur much of the credit for the victory; in fact his role was minor, although he was certainly an active participant in the case. In another civil rights case in 1854, Arthur was the lead attorney representing Elizabeth Jennings Graham after she was denied a seat on a streetcar because she was black. He won the case, and the verdict led to the desegregation of the New York City streetcar lines.

In 1856, Arthur courted Ellen Herndon, the daughter of William Lewis Herndon

Commander William Lewis Herndon (25 October 1813 – 12 September 1857) was one of the United States Navy's outstanding explorers and seamen. In 1851 he led a United States expedition to the Valley of the Amazon, and prepared a report published ...

, a Virginia naval officer. The two were soon engaged to be married. Later that year, he started a new law partnership with a friend, Henry D. Gardiner, and traveled with him to Kansas to consider purchasing land and setting up a law practice there. At that time, the state was the scene of a brutal struggle between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces, and Arthur lined up firmly with the latter. The rough frontier life did not agree with the genteel New Yorkers; after three or four months the two young lawyers returned to New York City, where Arthur comforted his fiancée after her father was lost at sea in the wreck of the SS ''Central America''. In 1859, they were married at Calvary Episcopal Church in Manhattan. The couple had three children:

* William Lewis Arthur (December 10, 1860 – July 7, 1863), died of "convulsions

A convulsion is a medical condition where the body muscles contract and relax rapidly and repeatedly, resulting in uncontrolled shaking. Because epileptic seizures typically include convulsions, the term ''convulsion'' is sometimes used as a s ...

"

* Chester Alan Arthur II

Chester Alan Arthur II, also known as Alan Arthur, (July 25, 1864 – July 18, 1937) was a son of Chester A. Arthur, president of the United States from 1881 to 1885. He studied at Princeton University and Columbia Law School. After completi ...

(July 25, 1864 – July 18, 1937), married Myra Townsend, then Rowena Graves, father of Gavin Arthur

Chester Alan "Gavin" Arthur III (March 21, 1901 – April 28, 1972) was an American astrologer and sexologist. He was the grandson of Chester A. Arthur, the twenty-first president of the United States. He received his early education from Col ...

* Ellen Hansbrough Herndon "Nell" Arthur Pinkerton (November 21, 1871 – September 6, 1915), married Charles Pinkerton

After his marriage, Arthur devoted his efforts to building his law practice, but also found time to engage in Republican party politics. In addition, he indulged his military interest by becoming Judge Advocate General for the Second Brigade of the New York Militia.

Civil War

In 1861, Arthur was appointed to the military staff of GovernorEdwin D. Morgan

Edwin Denison Morgan (February 8, 1811February 14, 1883) was the 21st governor of New York from 1859 to 1862 and served in the United States Senate from 1863 to 1869. He was the first and longest-serving chairman of the Republican National Comm ...

as engineer-in-chief. The office was a patronage appointment of minor importance until the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, when New York and the other northern states were faced with raising and equipping armies of a size never before seen in American history. Arthur was commissioned as a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

and assigned to the state militia's quartermaster

Quartermaster is a military term, the meaning of which depends on the country and service. In land armies, a quartermaster is generally a relatively senior soldier who supervises stores or barracks and distributes supplies and provisions. In m ...

department. He was so efficient at housing and outfitting the troops that poured into New York City that he was promoted to inspector general of the state militia in March 1862, and then to quartermaster general that July. He had an opportunity to serve at the front when the 9th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment

The 9th New York Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. It was also known as the "''Hawkins' Zouaves''" or the "''New York Zouaves''."

Military service, 1861

In April 1861 with the ...

elected him commander with the rank of colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

early in the war, but at Governor Morgan's request, he turned it down to remain at his post in New York. He also turned down command of four New York City regiments organized as the Metropolitan Brigade, again at Morgan's request. The closest Arthur came to the front was when he traveled south to inspect New York troops near Fredericksburg, Virginia, in May 1862, shortly after forces under Major General Irvin McDowell seized the town during the Peninsula Campaign. That summer, he and other representatives of northern governors met with Secretary of State William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senate, United States Senat ...

in New York to coordinate the raising of additional troops, and he spent the next few months helping to enlist New York's quota of 120,000 men. Arthur received plaudits for his work, but his post was a political appointment, and he was relieved of his militia duties in January 1863 when Governor Horatio Seymour

Horatio Seymour (May 31, 1810February 12, 1886) was an American politician. He served as Governor of New York from 1853 to 1854 and from 1863 to 1864. He was the Democratic Party nominee for president in the 1868 United States presidential elec ...

, a Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

, took office. When Reuben Fenton

Reuben Eaton Fenton (July 4, 1819August 25, 1885) was an American merchant and politician from New York (state), New York. In the mid-19th Century, he served as a United States House of Representatives , U.S. Representative, a United States Sen ...

won the 1864 election for governor, Arthur requested reappointment; Fenton and Arthur were from different factions of the Republican Party, and Fenton had already committed to appointing another candidate, so Arthur did not return to military service.

Arthur returned to practicing law, and with the help of additional contacts made in the military, he and the firm of Arthur & Gardiner flourished. Even as his professional life improved, however, Arthur and his wife experienced a personal tragedy as their only child, William, died suddenly that year at the age of two. The couple took their son's death hard, and when they had another son, Chester Alan Jr., in 1864, they lavished attention on him. They also had a daughter, Ellen, in 1871. Both children survived to adulthood.

Arthur's political prospects improved along with his law practice when his patron, ex-Governor Morgan, was elected to the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

. He was hired by Thomas Murphy, a Republican politician, but also a friend of William M. Tweed

William Magear Tweed (April 3, 1823 – April 12, 1878), often erroneously referred to as William "Marcy" Tweed (see below), and widely known as "Boss" Tweed, was an American politician most notable for being the political boss of Tammany H ...

, the boss of the Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

Democratic organization. Murphy was also a hatter

Hat-making or millinery is the design, manufacture and sale of hats and other headwear. A person engaged in this trade is called a milliner or hatter.

Historically, milliners, typically women shopkeepers, produced or imported an inventory of g ...

who sold goods to the Union Army, and Arthur represented him in Washington. The two became associates within New York Republican party circles, eventually rising in the ranks of the conservative branch of the party dominated by Thurlow Weed

Edward Thurlow Weed (November 15, 1797 – November 22, 1882) was a printer, New York newspaper publisher, and Whig and Republican politician. He was the principal political advisor to prominent New York politician William H. Seward and was ins ...

. In the presidential election of 1864, Arthur and Murphy raised funds from Republicans in New York, and they attended the second inauguration of Abraham Lincoln

The second inauguration of Abraham Lincoln as president of the United States took place on Saturday, March 4, 1865, at the East Portico of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. This was the 20th inauguration and marked the commencement o ...

in 1865.

New York politician

Conkling's machine

The end of the Civil War meant new opportunities for the men in Morgan's Republican

The end of the Civil War meant new opportunities for the men in Morgan's Republican machine

A machine is a physical system using Power (physics), power to apply Force, forces and control Motion, movement to perform an action. The term is commonly applied to artificial devices, such as those employing engines or motors, but also to na ...

, including Arthur. Morgan leaned toward the conservative wing of the New York Republican party, as did the men who worked with him in the organization, including Weed, Seward (who continued in office under President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

), and Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican Party (United States), Republican politician who represented New York (state), New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Se ...

(an eloquent Utica Congressman and rising star in the party). Arthur rarely articulated his own political ideas during his time as a part of the machine; as was common at the time, loyalty and hard work on the machine's behalf was more important than actual political positions.

At the time, U.S. custom house

A custom house or customs house was traditionally a building housing the offices for a jurisdictional government whose officials oversaw the functions associated with importing and exporting goods into and out of a country, such as collecting c ...

s were managed by political appointees who served as Collector, Naval Officer, and Surveyor. In 1866, Arthur unsuccessfully attempted to secure the position of Naval Officer at the New York Custom House

The United States Custom House, sometimes referred to as the New York Custom House, was the place where the United States Customs Service collected federal customs duties on imported goods within New York City.

Locations

The Custom House ...

, a lucrative job subordinate only to the Collector. He continued his law practice (now a solo practice after Gardiner's death) and his role in politics, becoming a member of the prestigious Century Club in 1867. Conkling, elected to the United States Senate in 1867, noticed Arthur and facilitated his rise in the party, and Arthur became chairman of the New York City Republican executive committee in 1868. His ascent in the party hierarchy kept him busy most nights, and his wife resented his continual absence from the family home on party business.

Conkling succeeded to leadership of the conservative wing of New York's Republicans by 1868 as Morgan concentrated more time and effort on national politics, including serving as chairman of the Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is a U.S. political committee that assists the Republican Party of the United States. It is responsible for developing and promoting the Republican brand and political platform, as well as assisting in fu ...

. The Conkling machine was solidly behind General Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

's candidacy for president, and Arthur raised funds for Grant's election in 1868. The opposing Democratic machine in New York City, known as Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

, worked for Grant's opponent, former New York Governor Horatio Seymour

Horatio Seymour (May 31, 1810February 12, 1886) was an American politician. He served as Governor of New York from 1853 to 1854 and from 1863 to 1864. He was the Democratic Party nominee for president in the 1868 United States presidential elec ...

; while Grant was victorious in the national vote, Seymour narrowly carried the state of New York. Arthur began to devote more of his time to politics and less to law, and in 1869 he became counsel to the New York City Tax Commission, appointed when Republicans controlled the state legislature

A state legislature is a legislative branch or body of a political subdivision in a federal system.

Two federations literally use the term "state legislature":

* The legislative branches of each of the fifty state governments of the United Sta ...

. He remained at the job until 1870 at a salary of $10,000 a year. Arthur resigned after Democrats controlled by William M. Tweed of Tammany Hall won a legislative majority, which meant they could name their own appointee. In 1871, Grant offered to name Arthur as Commissioner of Internal Revenue, replacing Alfred Pleasonton; Arthur declined the appointment.

In 1870, President Grant gave Conkling control over New York patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

, including the Custom House at the Port of New York. Having become friendly with Murphy over their shared love of horses during summer vacations on the Jersey Shore

The Jersey Shore (known by locals simply as the Shore) is the coastal region of the U.S. state of New Jersey. Geographically, the term encompasses about of oceanfront bordering the Atlantic Ocean, from Perth Amboy in the north to Cape May Po ...

, in July of that year, Grant appointed him to the Collector's position. Murphy's reputation as a war profiteer

A war profiteer is any person or organization that derives profit from warfare or by selling weapons and other goods to parties at war. The term typically carries strong negative connotations. General profiteering, making a profit criticized a ...

and his association with Tammany Hall made him unacceptable to many of his own party, but Conkling convinced the Senate to confirm him. The Collector was responsible for hiring hundreds of workers to collect the tariffs due at the United States' busiest port. Typically, these jobs were dispensed to adherents of the political machine responsible for appointing the Collector. Employees were required to make political contributions (known as "assessments") back to the machine, which made the job a highly coveted political plum. Murphy's unpopularity only increased as he replaced workers loyal to Senator Reuben Fenton

Reuben Eaton Fenton (July 4, 1819August 25, 1885) was an American merchant and politician from New York (state), New York. In the mid-19th Century, he served as a United States House of Representatives , U.S. Representative, a United States Sen ...

's faction of the Republican party with those loyal to Conkling's. Eventually, the pressure to replace Murphy grew too great, and Grant asked for his resignation in December 1871. Grant offered the position to John Augustus Griswold

John Augustus Griswold (November 11, 1818 – October 31, 1872) was an American businessman and politician from New York. He served three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1863 to 1869.

Early life

Griswold was born on November ...

and William Orton, each of whom declined and recommended Arthur. Grant then nominated Arthur, with the ''New York Times'' commenting, "his name very seldom rises to the surface of metropolitan life and yet moving like a mighty undercurrent this man during the last 10 years has done more to mold the course of the Republican Party in this state than any other one man in the country."

The Senate confirmed Arthur's appointment; as Collector he controlled nearly a thousand jobs and received compensation as great as any federal officeholder. Arthur's salary was initially $6,500, but senior customs employees were compensated additionally by the "moiety" system, which awarded them a percentage of the cargoes seized and fines levied on importers who attempted to evade the tariff. In total, his income came to more than $50,000—more than the president's salary, and more than enough for him to enjoy fashionable clothes and a lavish lifestyle. Among those who dealt with the Custom House, Arthur was one of the era's more popular collectors. He got along with his subordinates and, since Murphy had already filled the staff with Conkling's adherents, he had few occasions to fire anyone. He was also popular within the Republican party as he efficiently collected campaign assessments from the staff and placed party leaders' friends in jobs as positions became available. Arthur had a better reputation than Murphy, but reformers still criticized the patronage structure and the moiety system as corrupt. A rising tide of reform within the party caused Arthur to rename the financial extractions from employees as "voluntary contributions" in 1872, but the concept remained, and the party reaped the benefit of controlling government jobs. In that year, reform-minded Republicans formed the Liberal Republican party and voted against Grant, but he was re-elected in spite of their opposition. Nevertheless, the movement for civil service reform continued to chip away at Conkling's patronage machine; in 1874 Custom House employees were found to have improperly assessed fines against an importing company as a way to increase their own incomes, and Congress reacted, repealing the moiety system and putting the staff, including Arthur, on regular salaries. As a result, his income dropped to $12,000 a year—more than his nominal boss, the Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

, but far less than what he had previously received.

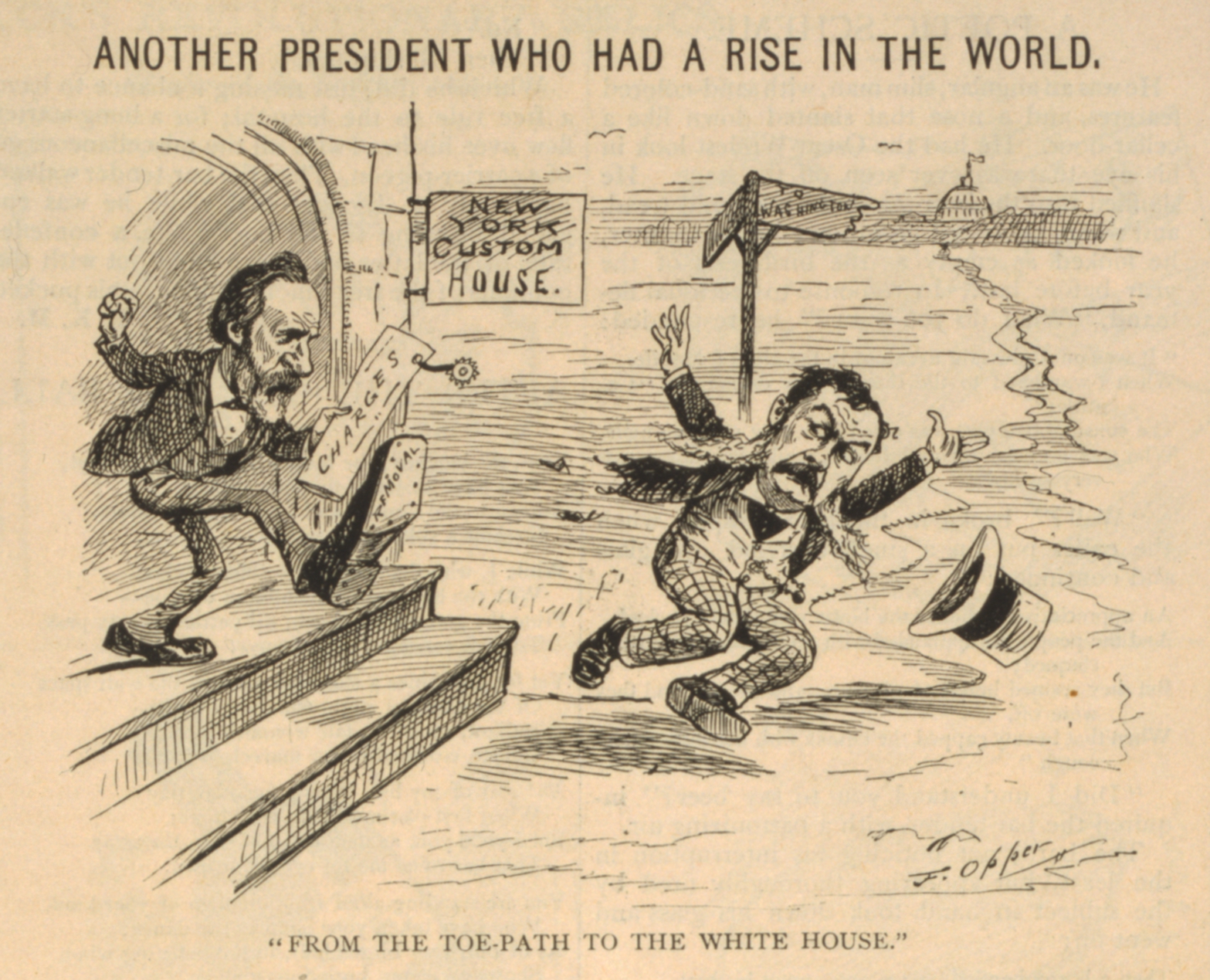

Clash with Hayes

Arthur's four-year term as Collector expired on December 10, 1875, and Conkling, then among the most powerful politicians in Washington, arranged his protégé's reappointment by President Grant. In 1876, Conkling was a candidate for president at the

Arthur's four-year term as Collector expired on December 10, 1875, and Conkling, then among the most powerful politicians in Washington, arranged his protégé's reappointment by President Grant. In 1876, Conkling was a candidate for president at the 1876 Republican National Convention

The 1876 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held at the Exposition Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio on June 14–16, 1876. President Ulysses S. Grant had considered seeking a third term, but with various scandals, a p ...

, but the nomination was won by reformer Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

on the seventh ballot. Arthur and the machine gathered campaign funds with their usual zeal, but Conkling limited his own campaign activities for Hayes to a few speeches. Hayes's opponent, New York Governor Samuel J. Tilden

Samuel Jones Tilden (February 9, 1814 – August 4, 1886) was an American politician who served as the 25th Governor of New York and was the Democratic candidate for president in the disputed 1876 United States presidential election. Tilden was ...

, carried New York and won the popular vote nationwide, but after the resolution of several months of disputes over twenty electoral votes (from Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina), Hayes was declared the winner.

Hayes entered office with a pledge to reform the patronage system; in 1877, he and Treasury Secretary John Sherman

John Sherman (May 10, 1823October 22, 1900) was an American politician from Ohio throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century. A member of the Republican Party, he served in both houses of the U.S. Congress. He also served as ...

made Conkling's machine the primary target. Sherman ordered a commission led by John Jay to investigate the New York Custom House. Jay, with whom Arthur had collaborated in the ''Lemmon'' case two decades earlier, suggested that the Custom House was overstaffed with political appointments, and that 20% of the employees were expendable. Sherman was less enthusiastic about the reforms than Hayes and Jay, but he approved the commission's report and ordered Arthur to make the personnel reductions. Arthur appointed a committee of Custom House workers to determine where the cuts were to be made and, after a written protest, carried them out. Notwithstanding his cooperation, the Jay Commission issued a second report critical of Arthur and other Custom House employees, and subsequent reports urging a complete reorganization.

Hayes further struck at the heart of the spoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a reward ...

by issuing an executive order that forbade assessments, and barred federal office holders from "...tak ngpart in the management of political organizations, caucuses, conventions, or election campaigns." Arthur and his subordinates, Naval Officer Alonzo B. Cornell

Alonzo Barton Cornell (January 22, 1832 – October 15, 1904) was a New York politician and businessman who was the 27th Governor of New York from 1880 to 1882.

Early years

Cornell was born in Ithaca, New York, on January 22, 1832. He was ...

and Surveyor George H. Sharpe

George Henry Sharpe (February 26, 1828 – January 13, 1900) was an American lawyer, soldier, United States Secret Service, Secret Service officer, diplomat, politician, and Member of the Board of General Appraisers.

Sharpe was born in 1828, in ...

, refused to obey the president's order; Sherman encouraged Arthur to resign, offering him appointment by Hayes to the consulship in Paris in exchange, but Arthur refused. In September 1877, Hayes demanded the three men's resignations, which they refused to give. Hayes then submitted the appointment of Theodore Roosevelt Sr.

Theodore Roosevelt Sr. (September 22, 1831 – February 9, 1878) was an American businessman and philanthropist from the Roosevelt family. Roosevelt was also the father of President Theodore Roosevelt and the paternal grandfather of First Lady E ...

, L. Bradford Prince

LeBaron Bradford Prince (July 3, 1840December 8, 1922) was an American lawyer and politician who served as chief justice of the New Mexico Territorial Supreme Court from 1878 to 1882, and as the 14th Governor of New Mexico Territory from 1889 to ...

, and Edwin Merritt (all supporters of Conkling's rival William M. Evarts

William Maxwell Evarts (February 6, 1818February 28, 1901) was an American lawyer and statesman from New York who served as U.S. Secretary of State, U.S. Attorney General and U.S. Senator from New York. He was renowned for his skills as a litiga ...

) to the Senate for confirmation as their replacements. The Senate's Commerce Committee, chaired by Conkling, unanimously rejected all the nominees; the full Senate rejected Roosevelt by a vote of 31–25 and similarly turned down the nomination of Prince by the same margin, later confirming Merritt only because Sharpe's term had expired.

Arthur's job was spared only until July 1878, when Hayes took advantage of a Congressional recess to fire him and Cornell, replacing them with the recess appointment

In the United States, a recess appointment is an appointment by the president of a federal official when the U.S. Senate is in recess. Under the U.S. Constitution's Appointments Clause, the President is empowered to nominate, and with the advi ...

of Merritt and Silas W. Burt Silas Wright Burt (April 5, 1830 – November 30, 1912) was a civil service reformer and naval officer of the port of New York.

Burt was born in Albany, New York, the son of Thomas Burt and Lydia (Butts) Burt in 1830. In 1855, he married Jeanette ...

. Hayes again offered Arthur the position of consul general in Paris as a face-saving consolation; Arthur again declined, as Hayes knew he probably would. Conkling opposed the confirmation of Merritt and Burt when the Senate reconvened in February 1879, but Merritt was approved by a vote of 31–25, as was Burt by 31–19, giving Hayes his most significant civil service reform victory. Arthur immediately took advantage of the resulting free time to work for the election of Edward Cooper as New York City's next mayor. In September 1879 Arthur became Chairman of the New York State Republican Executive Committee, a post in which he served until October 1881. In the state elections of 1879, he and Conkling worked to ensure that the Republican nominees for state offices would be men of Conkling's faction, who had become known as Stalwarts. They were successful, but narrowly, as Cornell was nominated for governor by a vote of 234–216. Arthur and Conkling campaigned vigorously for the Stalwart ticket and, owing partly to a splintering of the Democratic vote, were victorious. Arthur and the machine had rebuked Hayes and their intra-party rivals, but Arthur had only a few days to enjoy his triumph when, on January 12, 1880, his wife died suddenly while he was in Albany organizing the political agenda for the coming year. Arthur felt devastated, and perhaps guilty, and never remarried.

Election of 1880

Conkling and his fellow Stalwarts, including Arthur, wished to follow up their 1879 success at the

Conkling and his fellow Stalwarts, including Arthur, wished to follow up their 1879 success at the 1880 Republican National Convention

The 1880 Republican National Convention convened from June 2 to June 8, 1880, at the Interstate Exposition Building in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Delegates nominated James A. Garfield of Ohio and Chester A. Arthur of New York as the offic ...

by securing the presidential nomination for their ally, ex-President Grant. Their opponents in the Republican party, known as Half-Breeds, concentrated their efforts on James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine (January 31, 1830January 27, 1893) was an American statesman and Republican politician who represented Maine in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876, serving as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representative ...

, a senator from Maine who was more amenable to civil service reform. Neither candidate commanded a majority of delegates and, deadlocked after thirty-six ballots, the convention turned to a dark horse

A dark horse is a previously lesser-known person or thing that emerges to prominence in a situation, especially in a competition involving multiple rivals, or a contestant that on paper should be unlikely to succeed but yet still might.

Origin

Th ...

, James A. Garfield, an Ohio Congressman and Civil War general who was neither Stalwart nor Half-Breed.

Garfield and his supporters knew they would face a difficult election without the support of the New York Stalwarts and decided to offer one of them the vice presidential nomination. Levi P. Morton

Levi Parsons Morton (May 16, 1824 – May 16, 1920) was the 22nd vice president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He also served as United States ambassador to France, as a U.S. representative from New York, and as the 31st Governor of Ne ...

, the first choice of Garfield's supporters, consulted with Conkling, who advised him to decline, which he did. They next approached Arthur, and Conkling advised him to also reject the nomination, believing the Republicans would lose. Arthur thought otherwise and accepted. According to a purported eyewitness account by journalist William C. Hudson, Conkling and Arthur argued, with Arthur telling Conkling, "The office of the Vice-President is a greater honor than I ever dreamed of attaining." Conkling eventually relented, and campaigned for the ticket

Ticket or tickets may refer to:

Slips of paper

* Lottery ticket

* Parking ticket, a ticket confirming that the parking fee was paid (and the time of the parking start)

* Toll ticket, a slip of paper used to indicate where vehicles entered a tol ...

.

As expected, the election was close. The Democratic nominee, General Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

was popular and having avoided taking definitive positions on most issues of the day, he had not offended any pivotal constituencies. As Republicans had done since the end of the Civil War, Garfield and Arthur initially focused their campaign on the "bloody shirt

"Waving the bloody shirt" and "bloody shirt campaign" were pejorative phrases, used during American election campaigns in the 19th century, to deride opposing politicians who made emotional calls to avenge the blood of soldiers that died in the Ci ...

"—the idea that returning Democrats to office would undo the victory of the Civil War and reward secessionists.

protective tariff

Protective tariffs are tariffs that are enacted with the aim of protecting a domestic industry. They aim to make imported goods cost more than equivalent goods produced domestically, thereby causing sales of domestically produced goods to rise, ...

, which would allow cheaper manufactured goods to be imported from Europe, and thereby put thousands out of work. This argument struck home in the swing states of New York and Indiana, where many were employed in manufacturing. Hancock did not help his own cause when, in an attempt to remain neutral on the tariff, he said that " e tariff question is a local question", which only made him appear uninformed about an important issue. Candidates for high office did not personally campaign in those days, but as state Republican chairman, Arthur played a part in the campaign in his usual fashion: overseeing the effort in New York and raising money. The funds were crucial in the close election, and winning his home state of New York was critical. The Republicans carried New York by 20,000 votes and, in an election with the largest turnout of qualified voters ever recorded—78.4%—they won the nationwide popular vote by just 7,018 votes. The Electoral College result was more decisive—214 to 155—and Garfield and Arthur were elected.

Vice presidency (1881)

After the election, Arthur worked in vain to persuade Garfield to fill certain positions with his fellow New York Stalwarts—especially that of the Secretary of the Treasury; the Stalwart machine received a further rebuke when Garfield appointed Blaine, Conkling's arch-enemy, as Secretary of State. The running mates, never close, detached as Garfield continued to freeze out the Stalwarts from his patronage. Arthur's status in the administration diminished when, a month before inauguration day, he gave a speech before reporters suggesting the election in Indiana, a

After the election, Arthur worked in vain to persuade Garfield to fill certain positions with his fellow New York Stalwarts—especially that of the Secretary of the Treasury; the Stalwart machine received a further rebuke when Garfield appointed Blaine, Conkling's arch-enemy, as Secretary of State. The running mates, never close, detached as Garfield continued to freeze out the Stalwarts from his patronage. Arthur's status in the administration diminished when, a month before inauguration day, he gave a speech before reporters suggesting the election in Indiana, a swing state

In American politics, the term swing state (also known as battleground state or purple state) refers to any state that could reasonably be won by either the Democratic or Republican candidate in a statewide election, most often referring to pre ...

, had been won by Republicans through illegal machinations. Garfield ultimately appointed a Stalwart, Thomas Lemuel James

Thomas Lemuel James (March 29, 1831 – September 11, 1916) was an American journalist, government official, and banker who served as the United States Postmaster General in 1881.

Early life and family

James was born in Utica, New York, to W ...

, to be Postmaster General, but the cabinet fight and Arthur's ill-considered speech left the President and Vice President clearly estranged when they took office on March 4, 1881.

The Senate in the 47th United States Congress

The 47th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1881, ...

was divided among 37 Republicans, 37 Democrats, one independent ( David Davis) who caucused with the Democrats, one Readjuster (William Mahone

William Mahone (December 1, 1826October 8, 1895) was an American civil engineer, railroad executive, Confederate States Army general, and Virginia politician.

As a young man, Mahone was prominent in the building of Virginia's roads and railroa ...

), and four vacancies. Immediately, the Democrats attempted to organize the Senate, knowing that the vacancies would soon be filled by Republicans. As vice president, Arthur cast tie-breaking votes in favor of the Republicans when Mahone opted to join their caucus. Even so, the Senate remained deadlocked for two months over Garfield's nominations because of Conkling's opposition to some of them. Just before going into recess in May 1881, the situation became more complicated when Conkling and the other senator from New York, Thomas C. Platt

Thomas Collier Platt (July 15, 1833 – March 6, 1910), also known as Tom Platt

, resigned in protest of Garfield's continuing opposition to their faction.

With the Senate in recess, Arthur had no duties in Washington and returned to New York City. Once there, he traveled with Conkling to Albany, where the former senator hoped for a quick re-election to the Senate, and with it, a defeat for the Garfield administration. The Republican majority in the state legislature was divided on the question, to Conkling and Platt's surprise, and an intense campaign in the statehouse ensued.

While in Albany on July 2, Arthur learned that Garfield had been shot. The assassin, Charles J. Guiteau

Charles Julius Guiteau ( ; September 8, 1841June 30, 1882) was an American man who assassinated James A. Garfield, president of the United States, on July 2, 1881. Guiteau falsely believed he had played a major role in Garfield's election vic ...

was a deranged office-seeker who believed that Garfield's successor would appoint him to a patronage job. He proclaimed to onlookers: "I am a Stalwart, and Arthur will be President!" Guiteau was found to be mentally unstable, and despite his claims to be a Stalwart supporter of Arthur, they had only a tenuous connection that dated from the 1880 campaign. Twenty-nine days before his execution for shooting Garfield, Guiteau composed a lengthy, unpublished poem claiming that Arthur knew the assassination had saved "our land he United States

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

. Guiteau's poem also states he had (incorrectly) presumed that Arthur would pardon him for the assassination.

More troubling was the lack of legal guidance on presidential succession: as Garfield lingered near death, no one was sure who, if anyone, could exercise presidential authority. Also, after Conkling's resignation, the Senate had adjourned without electing a ''president pro tempore

A president pro tempore or speaker pro tempore is a constitutionally recognized officer of a legislative body who presides over the chamber in the absence of the normal presiding officer. The phrase ''pro tempore'' is Latin "for the time being". ...

'', who would normally follow Arthur in the succession. Arthur was reluctant to be seen acting as president while Garfield lived, and for the next two months there was a void of authority in the executive office, with Garfield too weak to carry out his duties, and Arthur reluctant to assume them. Through the summer, Arthur refused to travel to Washington and was at his Lexington Avenue home when, on the night of September 19, he learned that Garfield had died. Judge John R. Brady

John Riker Brady (March 9, 1822 – March 16, 1891) was an American judge, a justice of the New York Supreme Court, and best known for administering the presidential oath of office to Chester A. Arthur.

Life and career

John Riker Brady ...

of the New York Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the State of New York is the trial-level court of general jurisdiction in the New York State Unified Court System. (Its Appellate Division is also the highest intermediate appellate court.) It is vested with unlimited civ ...

administered the oath of office

An oath of office is an oath or affirmation a person takes before assuming the duties of an office, usually a position in government or within a religious body, although such oaths are sometimes required of officers of other organizations. Such ...

in Arthur's home at 2:15 a.m. on September 20. Later that day he took a train to Long Branch to pay his respects to Garfield and to leave a card of sympathy for his wife, afterwards returning to New York City. On September 21, he returned to Long Branch to take part in Garfield's funeral, and then joined the funeral train to Washington. Before leaving New York, he ensured the presidential line of succession by preparing and mailing to the White House a proclamation calling for a Senate special session. This step ensured that the Senate had legal authority to convene immediately and choose a Senate president pro tempore, who would be able to assume the presidency if Arthur died. Once in Washington he destroyed the mailed proclamation and issued a formal call for a special session.

Presidency (1881–1885)

Taking office

Arthur arrived inWashington, D.C

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

. on September 21. On September 22, he re-took the oath of office, this time before Chief Justice Morrison R. Waite

Morrison Remick "Mott" Waite (November 29, 1816 – March 23, 1888) was an American attorney, jurist, and politician from Ohio. He served as the seventh chief justice of the United States from 1874 until his death in 1888. During his tenur ...

. Arthur took this step to ensure procedural compliance; there had been a lingering question about whether a state court judge (Brady) could administer a federal oath of office. He initially took up residence at the home of Senator John P. Jones, while a White House remodeling he had ordered was carried out, including addition of an elaborate fifty-foot glass screen by Louis Comfort Tiffany

Louis Comfort Tiffany (February 18, 1848 – January 17, 1933) was an American artist and designer who worked in the decorative arts and is best known for his work in stained glass. He is the American artist most associated with the Art NouveauL ...

.

Arthur's sister,

Arthur's sister, Mary Arthur McElroy