The third presidential term of

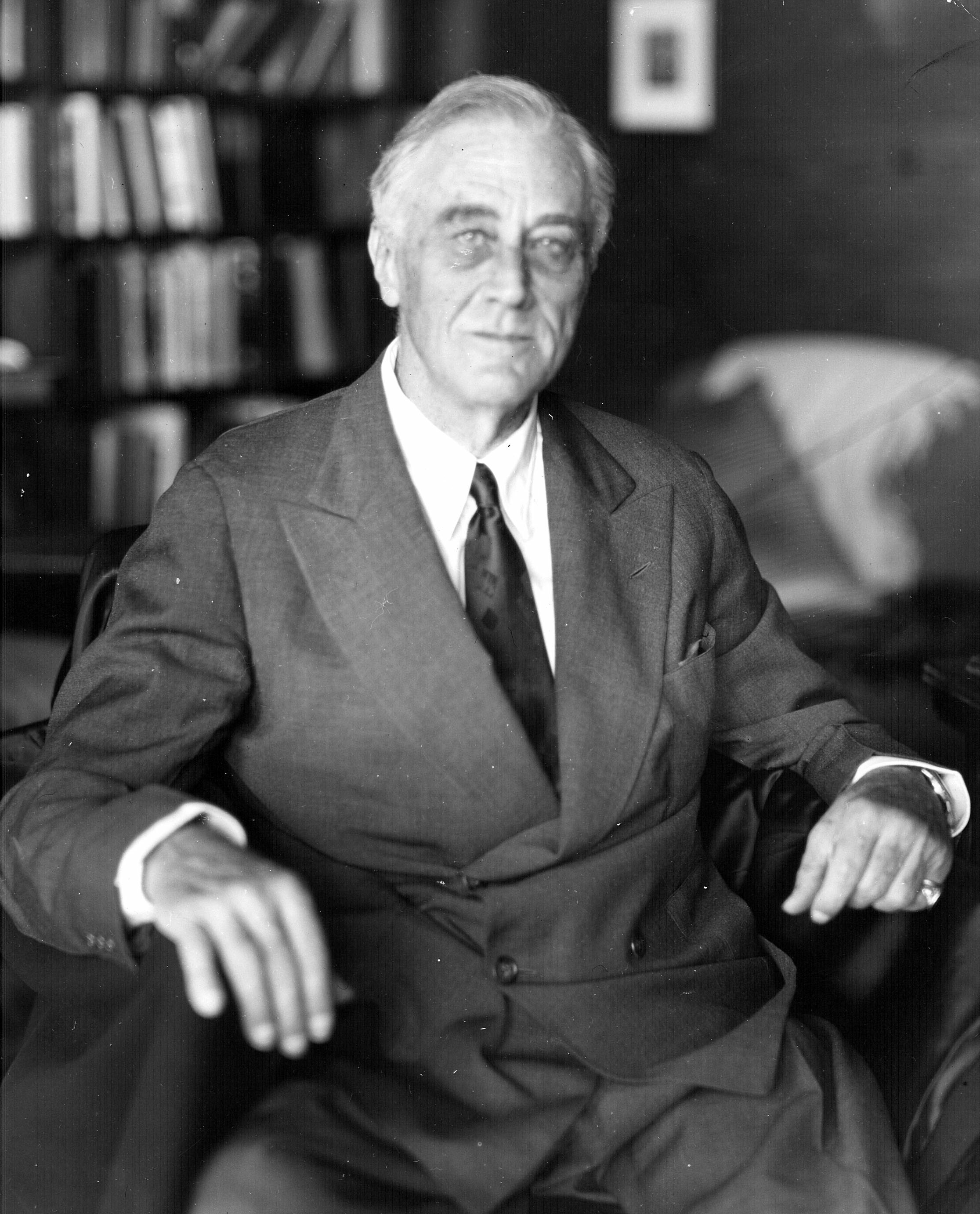

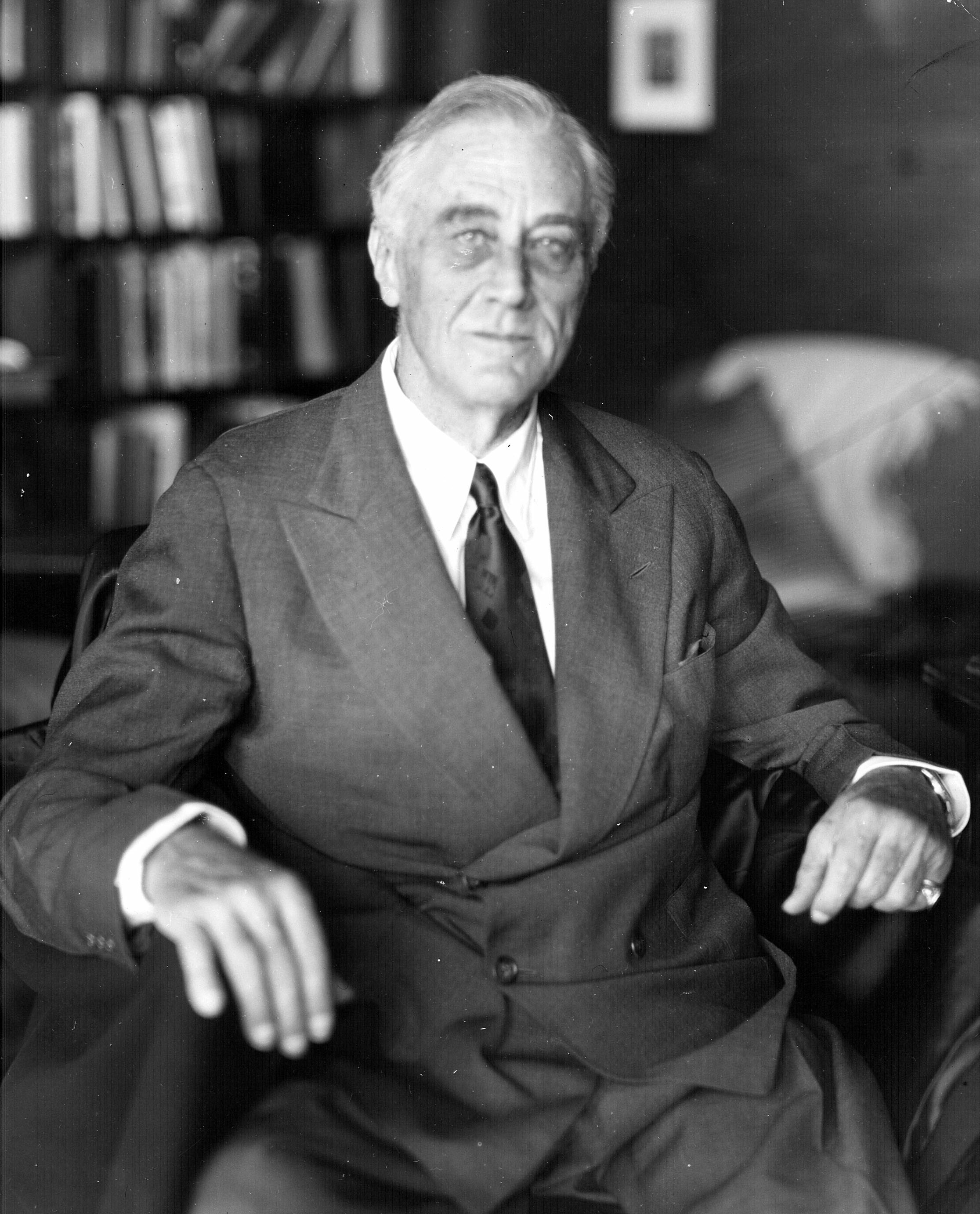

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

began on January 20, 1941, when he was

once again inaugurated as the

32nd president of the United States, and the fourth term of his presidency ended with his death on April 12, 1945. Roosevelt won a third term by defeating

Republican nominee

Wendell Willkie

Wendell Lewis Willkie (born Lewis Wendell Willkie; February 18, 1892 – October 8, 1944) was an American lawyer, corporate executive and the 1940 History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican nominee for president. Willkie appeale ...

in the

1940 presidential election. He remains the only president to serve for more than two terms. Unlike

his first two terms, Roosevelt's third and fourth terms were dominated by foreign policy concerns, as the United States became involved in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in December 1941.

Roosevelt won congressional approval of the

Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (),3,000 Hurricanes and >4,000 other aircraft)

* 28 naval vessels:

** 1 Battleship. (HMS Royal Sovereign (05), HMS Royal Sovereign)

* ...

program, which was designed to aid the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

in its war against

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, while the U.S. remained officially neutral. After

Germany began war against the Soviet Union in June 1941, Roosevelt extended Lend-Lease to the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

as well. In Asia, Roosevelt provided aid to the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

, which was resisting an invasion by the

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

. In response to the July 1941

Japanese occupation of French Indochina

In mid-1940, Nazi Germany rapidly defeated the French Third Republic, and the colonial administration of French Indochina (modern-day Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia) passed to the French State (Vichy France). Many concessions were granted to th ...

, Roosevelt expanded a trade embargo to cut off oil that Japan urgently needed for its fleet. When Roosevelt refused to end the embargo, on December 7, 1941, Japan launched an

attack on the U.S. fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Isolationist sentiment in the U.S. immediately collapsed and Congress

declared war on Japan. After Germany declared war on the U.S., Congress declared war on it and Italy. To win the war, the U.S., Britain and the Soviet Union assembled a large coalition of the

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

. The U.S. funded much of the war efforts of the other allies, and supplied munitions, food, and oil. In consultation with his Army and Navy and British Prime Minister

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, Roosevelt decided on a

Europe first

Europe first, also known as Germany first, was the key element of the grand strategy agreed upon by the United States and the United Kingdom during World War II after the United States joined the war in December 1941. According to this policy, the ...

strategy, which focused on defeating Germany before Japan. In practice, however, in 1942 and 1943 the U.S. focused on fighting Japan.

In late 1942 U.S. began its ground campaign against Germany with an invasion of North Africa. The German and Italian forces surrendered in May 1943, opening the way for the invasions of Sicily and Italy. Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy won a decisive victory over Japan in the Battle of Midway and began a campaign of

island hopping

Leapfrogging was an amphibious military strategy employed by the Allies in the Pacific War against the Empire of Japan during World War II. The key idea was to bypass heavily fortified enemy islands instead of trying to capture every island i ...

in the Pacific. In 1943, the Allies launched an

invasion of Italy and continued to pursue the island hopping strategy. The top Allied leaders met at the

Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference (codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of the Allies of World War II, held between Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943. It was the first of the Allied World Wa ...

in 1943, where they began to discuss post-war plans. Among the concepts discussed was the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, an intergovernmental organization championed by Roosevelt that would replace the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

after the war. In 1944, the Allies launched a

successful invasion of northern France and the US Navy won a decisive naval victory over Japan in the

Battle of Leyte Gulf

The Battle of Leyte Gulf () 23–26 October 1944, was the largest naval battle of World War II and by some criteria the largest naval battle in history, with over 200,000 naval personnel involved.

By late 1944, Japan possessed fewer capital sh ...

. By the time of Roosevelt's death in April 1945, the Allies had occupied portions of Germany and the US was in the process of

capturing Okinawa

most commonly refers to:

* Okinawa Prefecture, Japan's southernmost prefecture

* Okinawa Island, the largest island of Okinawa Prefecture

* Okinawa Islands, an island group including Okinawa itself

* Okinawa (city), the second largest city in th ...

. Germany and Japan surrendered in May–August 1945 during the administration of Roosevelt's successor

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

, who previously served as Roosevelt's vice president.

Though foreign affairs dominated Roosevelt's third and fourth terms, important developments also took place on the home front. The military buildup spurred economic growth, and unemployment fell precipitously. The United States excelled at war production; in 1944, it produced more military aircraft than the combined output of Germany, Japan, Britain, and the Soviet Union. The United States also established the

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

to produce the world's first

nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s. As in Roosevelt's second term, the

conservative coalition

The conservative coalition, founded in 1937, was an unofficial alliance of members of the United States Congress which brought together the conservative wings of the Republican and Democratic parties to oppose President Franklin Delano Rooseve ...

prevented Roosevelt from passing major domestic legislation, though it did increase taxes to help pay for the war. Congress also passed the

G.I. Bill

The G.I. Bill, formally the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, was a law that provided a range of benefits for some of the returning World War II veterans (commonly referred to as G.I. (military), G.I.s). The original G.I. Bill expired in ...

, which provided several benefits to World War II veterans. Roosevelt avoided imposing heavy-handed censorship or harsh crackdowns on war-time dissent, but his administration relocated and

interned over a hundred thousand Japanese Americans. Roosevelt also prohibited religious and racial discrimination in the defense industry and established the

Fair Employment Practice Committee

The Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) was created in 1941 in the United States to implement Executive Order 8802 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt "banning discriminatory employment practices by Federal agencies and all unions and com ...

, the first national program designed to prevent employment discrimination. Scholars, historians, and the public typically rank Roosevelt alongside

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

and

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

as one of the three

greatest U.S. presidents.

1940 election

The two-term tradition had been an unwritten rule (until the ratification of the

22nd Amendment

The Twenty-second Amendment (Amendment XXII) to the United States Constitution limits the number of times a person can be elected to the office of President of the United States to two terms, and sets additional eligibility conditions for presi ...

after Roosevelt's presidency) since

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

declined to run for a third term in 1796. Both

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

and

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

were attacked for trying to obtain a third non-consecutive term. Roosevelt systematically undercut prominent Democrats who were angling for the nomination, including Vice President

John Nance Garner

John Nance Garner III (November 22, 1868 – November 7, 1967), known among his contemporaries as "Cactus Jack", was the 32nd vice president of the United States, serving from 1933 to 1941, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. A member of the ...

and two cabinet members, Secretary of State

Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull (October 2, 1871July 23, 1955) was an American politician from Tennessee and the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years (1933–1944) in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevel ...

and Postmaster General

James Farley

James Aloysius Farley (May 30, 1888 – June 9, 1976) was an American politician who simultaneously served as chairman of the New York State Democratic Committee, chairman of the Democratic National Committee, and United States Postmaster Gener ...

. Roosevelt moved the convention to Chicago where he had strong support from the city machine, which controlled the auditorium sound system. At the convention the opposition was poorly organized, but Farley had packed the galleries. Roosevelt sent a message saying that he would not run unless he was drafted, and that the delegates were free to vote for anyone. The delegates were stunned; then the loudspeaker screamed "We want Roosevelt... The world wants Roosevelt!" The delegates went wild and he was nominated by 946 to 147 on the first ballot. The tactic employed by Roosevelt was not entirely successful, as his goal had been to be drafted by acclamation. At Roosevelt's request, the convention nominated Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace for vice president. Democratic party leaders disliked Wallace, a former Republican who strongly supported the New Deal, but were unable to prevent his nomination.

World War II shook up the Republican field, possibly preventing the nomination of isolationist congressional leaders like Taft or Vandenberg. The

1940 Republican National Convention

The 1940 Republican National Convention was held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from June 24 to June 28, 1940. It nominated Wendell Willkie of New York for President of the United States, president and Senator Charles L. McNary, Charles McNary ...

instead nominated

Wendell Willkie

Wendell Lewis Willkie (born Lewis Wendell Willkie; February 18, 1892 – October 8, 1944) was an American lawyer, corporate executive and the 1940 History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican nominee for president. Willkie appeale ...

, who had never held public office. A well-known corporate attorney and executive, Willkie rose to public notice through his criticism of the New Deal and his clashes with the TVA. Unlike his isolationist rivals for the Republican nomination, Willkie favored Britain in the war, and he was backed by internationalist Republicans like

Henry Luce

Henry Robinson Luce (April 3, 1898 – February 28, 1967) was an American magazine magnate who founded ''Time'', ''Life'', '' Fortune'', and ''Sports Illustrated'' magazines. He has been called "the most influential private citizen in the Amer ...

the publisher of influential magazines like ''TIME''. Willkie's internationalist views initially prevented disputes over foreign policy from dominating the campaign, helping to allow for the Destroyers for Bases Agreement and the establishment of a peacetime draft.

FDR was in a fighting mood, as he called out to an enthusiastic audience in Brooklyn:

:I am only fighting for a free America – for a country in which all men and women have equal rights to liberty and justice. I'm fighting against the revival of government by special privilege....I am fighting, as I always have fought, for the rights of the little man as well as the big man....I'm fighting to keep this nation prosperous and at peace. I'm fighting to keep our people out of foreign wars, and to keep foreign conceptions of government out of our own United States. I'm fighting for these great and good causes.

As the campaign drew to a close, Willkie warned that Roosevelt's re-election would lead to the deployment of American soldiers abroad. In response, Roosevelt promised that, "Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars." Roosevelt won the

1940 election with 55% of the popular vote and almost 85% of the electoral vote (449 to 82). Willkie won ten states: strongly Republican states of Vermont and Maine, and eight isolationist states in the Midwest. The Democrats retained their congressional majorities, but the conservative coalition largely controlled domestic legislation and remained "leery of presidential extensions of executive power through social programs."

Personnel

Executive branch

Roosevelt's standard strategy was to give two different people the same role, expecting controversy would result. He wanted the agencies' heads to bring the controversy to him and he would make the decision. Roosevelt on August 21, 1942, explicitly wrote all of his department heads that disagreements: "should not be publicly aired, but are to be submitted to me by the appropriate heads of the conflicting agencies." Anyone going public had to resign. By far the most famous controversy came during the war when Secretary of Commerce

Jesse H. Jones and Vice President

Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was the 33rd vice president of the United States, serving from 1941 to 1945, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He served as the 11th U.S. secretary of agriculture and the 10th U.S ...

clashed publicly over who would purchase war supplies in Latin America. Congress gave the authority to the

Reconstruction Finance Corporation

The Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) was an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the United States federal government that served as a lender of last resort to US banks and businesses. Established in ...

controlled by Jones; Roosevelt gave the power to Wallace, who envisioned creating a sort of little New Deal for poorly paid South American workers. According to

James MacGregor Burns

James MacGregor Burns (August 3, 1918 – July 15, 2014) was an American historian and political scientist, presidential biographer, and authority on leadership studies. He was the Woodrow Wilson Professor of Government Emeritus at Williams Co ...

, Jones, a leader of Southern conservative Democrats, was, "taciturn, shrewd, practical, cautious.” Wallace, deeply distrusted by Democratic party leaders, was the, "hero of the Lib Labs, dreamy, utopian, even mystical yet, yet with his own bent for management and power." On July 15, 1943, days after they escalated their private controversy to Congress and the public, Roosevelt stripped both of their roles in the matter.

As World War II approached, Roosevelt brought in a new cohort of top leaders, including conservative Republicans to top Pentagon roles.

Frank Knox

William Franklin Knox (January 1, 1874 – April 28, 1944) was an American politician, soldier, newspaper editor, and publisher. He was the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1936 and Secretary of the Navy under Franklin D. Roosevelt d ...

, the 1936 Republican vice presidential nominee, became

Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On March 25, 2025, John Phelan was confirm ...

while former Secretary of State

Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and Demo ...

became

Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

. Roosevelt began convening a "war cabinet" consisting of Hull, Stimson, Knox,

Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the highest-ranking officer of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office () held by an Admiral (United States), admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the United States Secretary ...

Harold Rainsford Stark

Harold Raynsford Stark (November 12, 1880 – August 20, 1972) was an officer in the United States Navy during World War I and World War II, who served as the 8th Chief of Naval Operations from August 1, 1939, to March 26, 1942.

Early life a ...

, and

Army Chief of Staff George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army under pres ...

. In 1942 Roosevelt set up a new military command structure with Admiral

Ernest J. King

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was a fleet admiral in the United States Navy who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during World War II. Franklin Delano ...

(Stark's successor) as in complete control of the Navy and Marines. Marshall was in charge of the Army and nominally led the Air Force, which in practice was nearly independent and was commanded by General

Hap Arnold

Henry Harley "Hap" Arnold (25 June 1886 – 15 January 1950) was an American general officer holding the ranks of General of the Army and later, General of the Air Force. Arnold was an aviation pioneer, Chief of the Air Corps (1938–1 ...

. Roosevelt formed a new body, the

Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, which advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and ...

, which made the final decisions on American military strategy. The Joint Chiefs was a White House agency and was chaired by his old friend Admiral

William D. Leahy

William Daniel Leahy ( ; 6 May 1875 – 20 July 1959) was an American naval officer and was the most senior United States military officer on active duty during World War II; he held several titles and exercised considerable influence over for ...

. The Joint Chiefs worked closely with their British counterparts and formed the

Combined Chiefs of Staff

The Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) was the supreme military staff for the United States and Britain during World War II. It set all the major policy decisions for the two nations, subject to the approvals of British Prime Minister Winston Churchi ...

. Unlike Stalin, Churchill and Hitler, Roosevelt rarely overrode his military advisors. His civilian appointees handled the draft and procurement of men and equipment, but no civilians – not even the secretaries of War or Navy, had a voice in strategy. Roosevelt avoided the State Department and conducted high level diplomacy through his aides, especially

Harry Hopkins

Harold Lloyd Hopkins (August 17, 1890 – January 29, 1946) was an American statesman, public administrator, and presidential advisor. A trusted deputy to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hopkins directed New Deal relief programs before ser ...

. Since Hopkins also controlled $40 billion in Lend-Lease funds given to the Allies, they paid attention to him. Treasury Secretary

Henry Morgenthau Jr.

Henry Morgenthau Jr. (; May 11, 1891February 6, 1967) was the United States Secretary of the Treasury during most of the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt. He played the major role in designing and financing the New Deal. After 1937, whil ...

played an increasingly central role in foreign policy, especially regarding China.

Judicial appointments

Due to the retirements of Chief Justice

Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

and Associate Justice

James Clark McReynolds

James Clark McReynolds (February 3, 1862 – August 24, 1946) was an American lawyer and judge from Tennessee who served as United States Attorney General under President Woodrow Wilson and as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the Unit ...

, Roosevelt filled three Supreme Court vacancies in 1941. He elevated

Harlan F. Stone, a Republican appointed to the Court by Coolidge, to chief justice and then appointed two Democrats. Senator

James F. Byrnes

James Francis Byrnes ( ; May 2, 1882 – April 9, 1972) was an American judge and politician from South Carolina. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in the U.S. Congress and on the U.S. Supreme Court, as well as in the executive branch ...

of South Carolina and Attorney General

Robert H. Jackson

Robert Houghwout Jackson (February 13, 1892 – October 9, 1954) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1941 until his death in 1954. He had previously served as Un ...

became associate justices. The combination of the liberal Jackson, centrist Stone, and conservative Byrnes helped ensure the Senate confirmation of all three justices. Byrnes disliked serving on the Court, and he resigned to take a top position in the Roosevelt administration in 1942. Roosevelt nominated

Wiley Rutledge

Wiley Blount Rutledge Jr. (July 20, 1894 – September 10, 1949) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1943 to 1949. The ninth and final justice appointed by President Franklin ...

to replace him on the court. Rutledge a liberal federal appellate judge who would serve on the Supreme Court for just seven years. By the end of 1941, Roosevelt had appointed Stone,

Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black (February 27, 1886 – September 25, 1971) was an American lawyer, politician, and jurist who served as a U.S. Senator from Alabama from 1927 to 1937 and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, ass ...

,

Stanley Forman Reed

Stanley Forman Reed (December 31, 1884 – April 2, 1980) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1938 to 1957. He also served as U.S. Solicitor General from 1935 to 1938.

Born in Ma ...

,

Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, advocating judicial restraint.

Born in Vienna, Frankfurter im ...

,

William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 to 1975. Douglas was known for his strong progressive and civil libertari ...

,

Frank Murphy

William Francis Murphy (April 13, 1890July 19, 1949) was an American politician, lawyer, and jurist from Michigan. He was a Democrat who was named to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1940 after a political career that included serving ...

, Byrnes, Jackson, and Rutledge, making

Owen Roberts

Owen Josephus Roberts (May 2, 1875 – May 17, 1955) was an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1930 to 1945. He also led two Roberts Commissions, the first of which investigated the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the sec ...

the lone Supreme Court justice whom Roosevelt had not appointed to the Court or elevated to Chief Justice.

Roosevelt's appointees upheld his policies,

but often disagreed in other areas, especially after Roosevelt's death. William O. Douglas and Black served until the 1970s and joined or wrote many of the major decisions of the

Warren Court

The Warren Court was the period in the history of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1953 to 1969 when Earl Warren served as the chief justice. The Warren Court is often considered the most liberal court in U.S. history.

The Warren Cou ...

, while Jackson and Frankfurter advocated

judicial restraint

Judicial restraint is a judicial interpretation that recommends favoring the ''status quo'' in judicial activities and is the opposite of judicial activism. Aspects of judicial restraint include the principle of '' stare decisis'' (that new de ...

and deference to elected officials.

Prelude to war: 1941

Britain and Germany 1941

After his victory in the 1940 election, Roosevelt embarked on a public campaign to win congressional support for aid to the British. In December 1940, Roosevelt received an appeal from Churchill explaining London could not finance the “cash and carry” provision of the Neutrality Act. With British forces deeply committed to fighting Germany, Churchill asked Washington to provide loans and shipping for American goods. Roosevelt agreed and delivered a speech in which he called for the United States to serve as the "

Arsenal of Democracy

"Arsenal of Democracy" was the central phrase used by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in a Fireside chats, radio broadcast on the threat to national security, delivered on December 29, 1940—nearly a year before the United States entered t ...

," supplying aid to those resisting Germany and other aggressors. He stated, "if Great Britain goes down, the Axis Powers will control the continents of Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, and the high seas—and they will be in a position to bring enormous military and naval resources against this hemisphere."

In his January 1941

Four Freedoms

The Four Freedoms were goals articulated by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Monday, January 6, 1941. In an address known as the Four Freedoms speech (technically the 1941 State of the Union address), he proposed four fundamental freed ...

speech, Roosevelt laid out the case for an American defense of basic rights throughout the world. In that same speech, Roosevelt asked Congress to approve a

Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (),3,000 Hurricanes and >4,000 other aircraft)

* 28 naval vessels:

** 1 Battleship. (HMS Royal Sovereign (05), HMS Royal Sovereign)

* ...

program designed to provide military aid to Britain. The cover story was that the supplies were only being lent and would be returned after the war. With the backing of Willkie, the Lend-Lease bill passed by large majorities in both houses of Congress, with most of the opposition coming from Midwestern Republicans. Isolationists did, however, prevent the U.S. from providing naval escorts to merchant ships heading to Britain. Roosevelt also requested, and Congress granted, a massive boost in military expenditures. Military facilities, shipyards and munitions plants were built across the country (especially in the South) and the unemployment rate dropped below ten percent for the first time in over a decade. To oversee mobilization efforts, Roosevelt created the Office of Production Management, the

Office of Price Administration and Civilian Supply, and the

Supply Priorities and Allocations Board

The Supply Priorities and Allocations Board (SPAB) was a United States administrative entity within the Office for Emergency Management which was created and dissolved during World War II. The board was created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt ...

.

In late 1940, Admiral Stark had sent Roosevelt the

Plan Dog memo, which set forth four possible strategic war plans for fighting an anticipated

two-front war

In military terminology, a two-front war occurs when opposing forces encounter on two geographically separate fronts. The forces of two or more allied parties usually simultaneously engage an opponent in order to increase their chances of succes ...

against Japan and Germany. Of the four strategies, Stark advocated for the so-called "Plan Dog," which contemplated a

Europe first

Europe first, also known as Germany first, was the key element of the grand strategy agreed upon by the United States and the United Kingdom during World War II after the United States joined the war in December 1941. According to this policy, the ...

strategy and the avoidance of conflict with Japan for as long as possible. A key part of this strategy was to ensure that Britain remained in the fight against Germany until the United States, potentially with the aid of other countries, could launch a land offensive into Europe. Roosevelt did not publicly commit to Plan Dog, but it motivated him to launch talks between American and British military staff, codenamed "

ABC–1." In early 1941, American and British military planners jointly agreed to pursue a Europe first strategy. In July 1941, Roosevelt ordered Secretary of War Stimson to begin planning for total American military involvement. The resulting "Victory Program" provided the army's estimates of the mobilization of manpower, industry, and logistics necessary to defeat Germany and Japan. The program planned to dramatically increase aid to the Allied nations and to prepare a force of ten million men in arms, half of whom would be ready for deployment abroad in 1943.

When Germany

invaded

An invasion is a military offensive of combatants of one geopolitical entity, usually in large numbers, entering territory controlled by another similar entity, often involving acts of aggression.

Generally, invasions have objectives of co ...

the Soviet Union in June 1941, Roosevelt extended Lend-Lease to Moscow. Thus, Roosevelt had committed the American economy to the

Allied cause with a policy of "all aid short of war." Some Americans were reluctant to aid the Soviet Union, but Roosevelt believed that the Soviets would be indispensable in the defeat of Germany. Execution of the aid fell victim to foot-dragging in the administration, so FDR appointed a special assistant,

Wayne Coy

Albert Wayne Coy (November 23, 1903 – September 24, 1957) served as chairman of the Federal Communications Commission from December 29, 1947, to February 21, 1952.

During World War II, he served as a Liaison Officer for the Office for Eme ...

, to expedite matters. The relationship with Moscow was informal—there was no treaty with the USSR.

Battle of the Atlantic 1941

In February 1941, Hitler refocused the war against Britain from air raids to naval operations, specifically

U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

(German submarine) raids against convoys of food and munitions headed to Britain. Canada and Britain provided naval escorts but Churchill needed more and asked Roosevelt. Roosevelt said no—he was still reluctant to challenge anti-war sentiment. In May, German submarines sank the ''

SS ''Robin Moor'','' an American freighter, but Roosevelt decided not to use the incident as a pretext to increase the navy's role in the Atlantic. Meanwhile, Germany celebrated victories against Yugoslavia, Greece, Russia, and the British forces in the Mediterranean.

In August 1941, Roosevelt and Churchill met secretly in

Argentia

Argentia ( ) is a Canadian commercial seaport and industrial park located in the Town of Placentia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Placentia, Newfoundland and Labrador. It is situated on the southwest coast of the Avalon Peninsula and defined by ...

,

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

. This meeting produced the

Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a statement issued on 14 August 1941 that set out American and British goals for the world after the end of World War II, months before the US officially entered the war. The joint statement, later dubbed the Atlantic C ...

, which conceptually outlined global wartime and postwar goals. Each leader pledged to support democracy,

self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

, free trade, and principles of non-aggression. Less than a month after Roosevelt and Churchill met at Argentia, a German submarine fired on the U.S. destroyer ''

Greer'', but the torpedo missed. In response, Roosevelt announced a new policy in which the U.S. would attack German U-boats that entered U.S. naval zones. This "shoot on sight" policy effectively declared naval war on Germany and was approved by Americans in polls by a margin of 2-to-1. The Roosevelt administration also took control over Greenland and Iceland, which provided useful naval bases in the northern Atlantic Ocean.

Seeking to bolster U.S. power in the Western Hemisphere and eliminate German influence, the Roosevelt administration increased military, commercial, and cultural engagement with Latin America.

Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich "Rocky" Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979) was the 41st vice president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977 under President Gerald Ford. He was also the 49th governor of New York, serving from 1959 to 197 ...

played a major role. The FBI trained the secret police of friendly nations. German sales to military forces was displaced by American aid. Pro-German newspapers and radio stations were blacklisted. Government censorship was encouraged, while Latin America was blanketed with pro-American propaganda. Hitler did not aggressively respond to U.S. actions, as he wanted to avoid any incident that would bring the U.S. into the war prior to the defeat of the Soviet Union.

In October 1941, the

USS ''Kearny'', along with other warships, engaged a number of U-boats south of Iceland; the ''Kearny'' took fire and lost eleven crewmen. Following the attack, Congress amended the Neutrality Act to allow U.S. ships to transport material to Britain, effectively repealing the last provision of the cash and carry policy. However, neither the ''Kearny'' incident nor an attack on the

USS ''Reuben James'' changed public opinion as much as Roosevelt hoped they might.

Tensions with Japan

By 1940, Japan had conquered much of the Chinese coast and major river valleys, but had been unable to defeat either the

Nationalist government

The Nationalist government, officially the National Government of the Republic of China, refers to the government of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China from 1 July 1925 to 20 May 1948, led by the nationalist Kuomintang (KMT ...

of

Chiang Kai-shek or the

Communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

forces under

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

. Though Japan's government was nominally led by the civilian government of Prime Minister

Fumimaro Konoye, Minister of War

Hideki Tojo

was a Japanese general and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1941 to 1944 during the Second World War. His leadership was marked by widespread state violence and mass killings perpetrated in the name of Japanese nationalis ...

and other military leaders controlled the Japanese government. Tojo sent his military to take control of lightly defended French colonies in Indochina, which provided important resources as well as a conduit of supply to Chinese forces. When Japan

occupied northern

French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China), officially known as the Indochinese Union and after 1941 as the Indochinese Federation, was a group of French dependent territories in Southeast Asia from 1887 to 1954. It was initial ...

in late 1940, Roosevelt authorized increased aid to the Republic of China, a policy that won widespread popular support. He also implemented a partial embargo on Japan, preventing the export of iron and steel. Over the next year, the Roosevelt administration debated imposing an embargo on oil, the key American export to Japan. Though some in the administration wanted to do everything possible to prevent Japanese expansion, Secretary of State Hull feared that cutting off trade would encourage the Japanese to meet its needs for natural resources through the conquest of the

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies (; ), was a Dutch Empire, Dutch colony with territory mostly comprising the modern state of Indonesia, which Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, declared independence on 17 Au ...

,

British Malaya

The term "British Malaya" (; ) loosely describes a set of states on the Malay Peninsula and the island of Singapore that were brought under British Empire, British hegemony or control between the late 18th and the mid-20th century. Unlike the ...

,

British Burma

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and cultur ...

, or the American Philippines.

With Roosevelt's attention focused on Europe, Hull took the lead in setting Asian policy and negotiating with Japan. Beginning in March 1941, Hull and Japanese ambassador

Kichisaburō Nomura

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy and was the ambassador to the United States at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Early life and career

Nomura was born in Wakayama city, Wakayama Prefecture. He graduated from the 26th class ...

sought to reach an accommodation between their respective governments. As the U.S. was not willing to accept the Japanese occupation of China, and Japan was not willing to withdraw from that country, the two sides were unable to reach an agreement. After Germany launched its invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Japanese declined to attack Soviet forces in Siberia, ending a long-running internal debate over the best target for Japanese expansion. In July, Japan took control of southern French Indochina, which provided a potential staging ground for an attack on British Burma and Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. In response, the U.S. cut off the sale of oil to Japan, which thus lost more than 95 percent of its oil supply.

Following the American embargo, Japanese planners studied how to seize the Dutch East Indies, which had a large supply of oil. Success required the capture the American Philippines and the British base at

Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

. That required sinking the

United States Pacific Fleet

The United States Pacific Fleet (USPACFLT) is a theater-level component command of the United States Navy, located in the Pacific Ocean. It provides naval forces to the Indo-Pacific Command. Fleet headquarters is at Joint Base Pearl Harbor� ...

, which was stationed at the

naval base

A naval base, navy base, or military port is a military base, where warships and naval ships are docked when they have no mission at sea or need to restock. Ships may also undergo repairs. Some naval bases are temporary homes to aircraft that usu ...

at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The planners did not see the total defeat of the United States as a feasible outcome. Japanese leaders expected that a decisive naval victory would convince Washington to negotiate a compromise. Prime Minister Konoye sought a summit with Roosevelt in order to negotiate a deal, but Roosevelt insisted the Japanese withdrawal from China first. Tojo succeeded Konoye as prime minister in October, 1941, and the Japanese began preparations for an attack on American, British and Dutch possessions. In November, Nomura made a final offer, asking for reopened trade and acceptance of the Japanese campaign in China in return for Japan's pledge not to attack Southeast Asia. In part because the U.S. feared that Japan would attack the Soviet Union after conquering China, Roosevelt rejected the offer, and negotiations collapsed on November 26.

Entrance into the war

On the morning of December 7, 1941, the Japanese

struck the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor with a surprise attack, knocking out the main American

battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

fleet and killing 2,403 American servicemen and civilians. Mainstream scholars have all rejected the

conspiracy thesis that Roosevelt, or any other high government officials, knew in advance about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese had kept their secrets closely guarded, and while senior American officials were aware that war was imminent, they did not expect an attack on Pearl Harbor.

After Pearl Harbor, antiwar sentiment in the United States evaporated overnight. For the first time since the early 19th century, foreign policy became the top priority for the American public. Roosevelt called for war in his famous "

Infamy Speech

The "Day of Infamy" speech, sometimes referred to as the Infamy speech, was a speech delivered by Franklin D. Roosevelt, the 32nd president of the United States, to a Joint session of the United States Congress, joint session of Congress on De ...

" to Congress, in which he said: "Yesterday, December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan." On December 8, Congress voted almost unanimously to

declare war against Japan. On December 11, 1941, Germany

declared war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the public signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national govern ...

on the United States, which

responded in kind.

Roosevelt portrayed the war as a crusade against the aggressive dictatorships that threatened peace and democracy throughout the world. He and his military advisers implemented a Europe-first strategy with the objectives of halting the German advances in the Soviet Union and in North Africa; launching an invasion of western Europe with the aim of crushing Nazi Germany between two fronts; and saving China and defeating Japan. Public opinion, however, gave priority to the destruction of Japan. In any case, Japan was attacking the American Philippines and so in practice the Pacific had priority in 1942. Japan bombed American air bases in the Philippines just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor and destroyed the B-17 fleet parked on the ground. By the end of the month, the

Japanese had invaded the Philippines. General

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

led American resistance in the Philippines until March 1942, when Roosevelt ordered him to evacuate to Australia, which became the forward American base. American forces in the Philippines surrendered in May 1942, leaving Japan with approximately ten thousand American prisoners. While it was subduing the Philippines, Japan also conquered Malaya, Singapore, Burma, and the Dutch East Indies.

In his role as the leader of the United States before and during World War II, Roosevelt tried to avoid repeating what he saw as Woodrow Wilson's mistakes in World War I. He often made exactly the opposite decision. Wilson had called for neutrality in thought and deed, while Roosevelt made it clear his administration strongly favored Britain and China. Unlike the loans in World War I, the United States made large-scale grants of military and economic aid to the Allies through Lend-Lease, with little expectation of repayment. Wilson failed to expand war production before the declaration of war; Roosevelt made an all-out effort in 1940. Wilson waited for the declaration to begin a draft; Roosevelt started one in 1940. Wilson never made the United States an official ally but Roosevelt did. Wilson never met with the top Allied leaders but Roosevelt did. Wilson proclaimed independent policy, as seen in the 14 Points, while Roosevelt sought a collaborative policy with the Allies. In 1917, the United States declared war on Germany; in 1941, Roosevelt waited until the enemy attacked at Pearl Harbor. Wilson refused to collaborate with the Republicans; Roosevelt named leading Republicans to head the War Department and the Navy Department. Wilson let General George Pershing make the major military decisions; Roosevelt made the major decisions in his war including the "

Europe first

Europe first, also known as Germany first, was the key element of the grand strategy agreed upon by the United States and the United Kingdom during World War II after the United States joined the war in December 1941. According to this policy, the ...

" strategy. He rejected the idea of an armistice and demanded unconditional surrender. Roosevelt often mentioned his role as

Assistant Secretary of the Navy

Assistant Secretary of the Navy (ASN) is the title given to certain civilian senior officials in the United States Department of the Navy.

From 1861 to 1954, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy was the second-highest civilian office in the Depart ...

in the Wilson administration, but added that he had profited more from Wilson's errors than from his successes.

Robert E. Sherwood

Robert Emmet Sherwood (April 4, 1896 – November 14, 1955) was an American playwright and screenwriter.

He is the author of ''Waterloo Bridge, Idiot's Delight, Abe Lincoln in Illinois, There Shall Be No Night'', and ''The Best Years of Our Li ...

argues:

Roosevelt could never forget Wilson's mistakes.... there was no motivating force in all of Roosevelt's wartime political policy stronger than the determination to prevent repetition of the same mistakes.

Alliances, economic warfare, and other wartime issues

Four Policemen

In late December 1941 Churchill and Roosevelt met at the

Arcadia Conference

The First Washington Conference, also known as the Arcadia Conference (ARCADIA was the code name used for the conference), was held in Washington, D.C., from December 22, 1941, to January 14, 1942. President Roosevelt of the United States and Prime ...

in Washington, which established a joint strategy between the U.S. and Britain. Both agreed on a

Europe first

Europe first, also known as Germany first, was the key element of the grand strategy agreed upon by the United States and the United Kingdom during World War II after the United States joined the war in December 1941. According to this policy, the ...

strategy that would prioritize the defeat of Germany before Japan. With British forces focused on the war in Europe, and with the Soviet Union not at war with Japan, the United States would take the lead in the Pacific War despite its own focus on Germany. The U.S. and Britain established the Combined Chiefs of Staff to coordinate military policy and the

Combined Munitions Assignments Board

The Combined Munitions Assignments Board was a major government agency for the U.S. and Britain in World War II. With Harry Hopkins, Roosevelt's top advisor in charge, it took control of the allocation of war supplies and Lend lease aid to the Al ...

to coordinate the allocation of supplies. An agreement was also reached to establish a centralized command in the Pacific theater called

ABDA

The American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) Command, or ABDACOM, was the short-lived supreme command for all Allied forces in South East Asia in early 1942, during the Pacific War in World War II. The command consisted of the forces of Austra ...

, named for the American, British, Dutch, and Australian forces in the theater. On January 1, 1942, the United States, Britain, China, the Soviet Union, and twenty-two other countries issued the

Declaration by United Nations

The Declaration by United Nations was the main treaty that formalized the Allies of World War II and was signed by 47 national governments between 1942 and 1945. On 1 January 1942, during the Arcadia Conference in Washington D.C., the Allied " B ...

, in which each nation pledged to defeat the Axis powers. These countries opposed to the Axis would be known as the

Allied Powers; sometimes they were called the "United Nations" before the UN was set up in 1945.

Roosevelt coined the term "

Four Policemen

The "Four Policemen" was a postwar council with the Big Four that U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed as a guarantor of world peace. Their members were called the Four Powers during World War II and were the four major Allies of Worl ...

" to refer to the "Big Four" Allied powers of World War II: the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and China. Roosevelt, Churchill, Soviet leader

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, and Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek cooperated informally on a plan in which American and British troops concentrated in the West, Soviet troops fought on the

Eastern front, and Chinese, British, and American troops fought in Asia and the Pacific. The Allies formulated strategy in a series of high-profile conferences as well as contact through diplomatic and military channels. Roosevelt had a close relationship with Churchill, but he and his advisers quickly lost respect for Chiang's government, viewing it as hopelessly corrupt. General

Joseph Stilwell

Joseph Warren "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell (19 March 1883 – 12 October 1946) was a United States Army general who served in the China Burma India theater during World War II. Stilwell was appointed as Chief of Staff for Chiang Kai-shek, the Chine ...

, who was assigned to lead U.S. forces in the

China Burma India Theater

China Burma India Theater (CBI) was the United States military designation during World War II for the China and Southeast Asian or India–Burma (IBT) theaters. Operational command of Allied forces (including U.S. forces) in the CBI was ...

, came to believe that Chiang was more concerned with defeating Mao's Communists than with defeating the Japanese. U.S. and Soviet leaders distrusted each other throughout the war, and relations further suffered after 1943 as both sides supported sympathetic governments in liberated territories.

Other allies

By the end of the war, several states, including all of Latin America, had joined the Allies. Roosevelt's appointment of young

Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich "Rocky" Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979) was the 41st vice president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977 under President Gerald Ford. He was also the 49th governor of New York, serving from 1959 to 197 ...

to head the new, well-funded

Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs

The Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, later known as the Office for Inter-American Affairs, was a United States agency promoting inter-American cooperation (Pan-Americanism) during the 1940s, especially in commercial and econ ...

provided energetic leadership. Under Rockefeller's leadership, the U.S. spent millions on radio broadcasts, motion pictures, and other anti-fascist propaganda. American advertising techniques generated a push back in Mexico especially, where well-informed locals resisted heavy-handed American influence. Nevertheless, Mexico was a valuable ally in the war. A deal was reached whereby 250,000 Mexican citizens living in the United States served in the American forces; over 1000 were killed in combat. In addition to propaganda, large sums were allocated for economic support and development. On the whole the Roosevelt policy in Latin America was a political success, except in Argentina, which tolerated German influence and refused to follow Washington's lead until the war was practically over. Outside of Latin America, the U.S. paid particularly close attention to its oil-rich allies in the Middle East, marking the start of sustained American engagement in the region.

Lend-Lease and economic warfare

The main American role in the war, beyond the military mission itself, was financing the war and providing large quantities of munitions and civilian goods. Lend-Lease, as passed by Congress in 1941, was a declaration of economic warfare, and that economic warfare continued after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Roosevelt believed that the financing of World War I through loans to the Allies, with the demand for repayment after the war, had been a mistake. He set up the Lend-Lease system as a war program, financed through the military budget; as soon as the war with Japan ended, it was terminated. The president chose the leadership—Hopkins and

Edward Stettinius Jr. played major roles—and exercised close oversight and control. One problem that bedeviled the program in 1942 was the strictly-limited supply of munitions that had to be divided between Lend-Lease and American forces. Roosevelt insisted to the military that Russia was to get all the supplies he had promised it. Lend-Lease aid to the Soviet Union declined somewhat in mid-1942 after the United States began to prepare for military operations in North Africa.

The U.S. spent about $40 billion on Lend-Lease aid to the British Empire, the Soviet Union, France, China, and some smaller countries. That amounted to about 11% of the cost of the war to the U.S. It received back about $7.8 billion in goods and services provided by the recipients to the United States, especially the cost of food and rent for American installations abroad. Britain received $30 billion, Russia received $10.7 billion, and all other countries $2.9 billion. When the question of repayment arose, Roosevelt insisted the United States did not want a postwar debt problem of the sort that had troubled relations after the first world war. The recipients provided bases and supplies to American forces on their own soil; this was referred informally as "Reverse Lend-Lease," and the combined total of this aid came to approximately $7.8 billion overall. In the end, none of the Allied Powers paid for the goods received during the war, although they did pay for goods in transit that were received after the program ended. Roosevelt told Congress in June 1942:

The real costs of the war cannot be measured, nor compared, nor paid for in money. They must and are being met in blood and toil.... If each country devotes roughly the same fraction of its national production to the war, then the financial burden of war is distributed equally among the United Nations in accordance with their ability to pay.

A major issue in the economic war was the transportation of supplies. After Germany declared war on the United States, Hitler removed all restrictions on the German submarine fleet. German submarines ravaged Allied shipping in the Atlantic, with many of the attacks taking place within ten miles of the

East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the region encompassing the coast, coastline where the Eastern United States meets the Atlantic Ocean; it has always pla ...

in early 1942. The U.S. Navy faced difficulties in simultaneously protecting Atlantic shipping while also prosecuting the war against Japan, and over one millions tons of Allied shipping was lost in 1942. The cracking of the German

Enigma code

The Enigma machine is a cipher device developed and used in the early- to mid-20th century to protect commercial, diplomatic, and military communication. It was employed extensively by Nazi Germany during World War II, in all branches of the G ...

, along with the construction and deployment of American naval escorts and

maritime patrol aircraft

A maritime patrol aircraft (MPA), also known as a patrol aircraft, maritime reconnaissance aircraft, maritime surveillance aircraft, or by the older American term patrol bomber, is a fixed-wing aircraft designed to operate for long durations over ...

helped give the Allied Powers the upper hand in the Battle of the Atlantic after 1942. After the Allies sank dozens of U-boats in early 1943, most German submarines were withdrawn from the North Atlantic.

The United States began a

strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a systematically organized and executed military attack from the air which can utilize strategic bombers, long- or medium-range missiles, or nuclear-armed fighter-bomber aircraft to attack targets deemed vital to the enemy' ...

campaign against Axis forces in Europe in mid-1942. Attacks initially targeted locations in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands; U.S. bombers launched their first attack against a target in Germany in January 1943. In an attempt to destroy Germany's industrial capacity, Allied bombers struck targets such as oil refineries and ball-bearing factories. After taking heavy losses in

Operation Tidal Wave

Operation Tidal Wave was an air attack by bombers of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) based in Libya on nine oil refineries around Ploiești, Romania, on 1 August 1943, during World War II. It was a strategic bombing mission and part o ...

and the

Second Raid on Schweinfurt

The second Schweinfurt raid, also called Black Thursday, was a World War II air battle that took place on 14 October 1943, over Nazi Germany between forces of the United States 8th Air Force and German ''Luftwaffe'' fighter arm (''Jagdwaffe''). ...

, the U.S. significantly scaled back the strategic bombing of Germany. General

Carl Andrew Spaatz

Carl Andrew Spaatz (born Spatz; 28 June 1891 – 14 July 1974), nicknamed "Tooey", was an American World War II general. As commander of Strategic Air Forces in Europe in 1944, he successfully pressed for the bombing of the enemy's oil productio ...

redirected U.S. strategic bombing efforts to focus on German aircraft production facilities, and the Allies enjoyed air superiority in Europe after February 1944. Allied strategic bombing escalated in late 1944, with an emphasis placed on Germany's transportation infrastructure and oil resources. With the goal of forcing a quick German surrender, in 1945 the Allies launched attacks on

Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

and

Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

that killed tens of thousands of civilians.

Reaction to the Holocaust

After

Kristallnacht

( ) or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation from the Hitler Youth and German civilia ...

in 1938, Roosevelt helped expedite Jewish immigration from Germany and allowed Austrian and German citizens already in the United States to stay indefinitely. He was prevented from accepting more Jewish immigrants by the prevalence of

nativism

Nativism may refer to:

* Nativism (politics), ethnocentric beliefs relating to immigration and nationalism

* Nativism (psychology), a concept in psychology and philosophy which asserts certain concepts are "native" or in the brain at birth

* Lingu ...

and

antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

among voters and members of Congress, resistance in the

American Jew

American Jews (; ) or Jewish Americans are Americans, American citizens who are Jews, Jewish, whether by Jewish culture, culture, ethnicity, or Judaism, religion. According to a 2020 poll conducted by Pew Research, approximately two thirds of Am ...

ish community to the acceptance of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, and the restrictive

Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from every count ...

. The Immigration Act of 1924 allowed only 150,000 immigrants to the United States per year and set firm quotas for each country, and in the midst of the Great Depression there was little popular support for revisions to the law that would have allowed for a more liberal immigration policy. Roosevelt pushed the limits of his executive authority where possible, which allowed for several Austrian and German Jews, including

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

, to escape from Europe or remain in the United States past their visa expirations.

Hitler chose to implement the "

Final Solution

The Final Solution or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question was a plan orchestrated by Nazi Germany during World War II for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews. The "Final Solution to the Jewish question" was the official ...

"—the extermination of the European Jewish population—by January 1942, and American officials learned of the scale of the Nazi extermination campaign in the following months. Against the objections of the State Department, Roosevelt convinced the other Allied leaders to jointly issue the

Joint Declaration by Members of the United Nations

The Joint Declaration by Members of the United Nations was the first formal statement to the world about the Holocaust, issued on December 17, 1942, by the American and British governments on behalf of the Allied Powers. In it, they describe th ...

, which condemned the ongoing

Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

and promised to try its perpetrators as

war criminals

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hostag ...

. In January 1944, Roosevelt established the

War Refugee Board

The War Refugee Board, established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in January 1944, was a U.S. executive agency to aid civilian victims of the Axis powers. The Board was, in the words of historian Rebecca Erbelding, "the only time in American hi ...

to aid Jews and other victims of Axis atrocities. Aside from these actions, Roosevelt believed that the best way to help the persecuted populations of Europe was to end the war as quickly as possible. Top military leaders and War Department leaders rejected any campaign to bomb the

extermination camps

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe, primarily in occupied Poland, during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocau ...

or the rail lines leading to the camps, fearing it would be a diversion from the war effort. According to biographer Jean Edward Smith, there is no evidence that anyone ever proposed such a campaign to Roosevelt himself.

Homefront

Relations with Congress

Up until Pearl Harbor, Congress played a very active role in foreign and military policy, dealing with neutrality laws, the draft, and Lend Lease. As with the general public, congressional sentiment was very hostile toward Germany and Japan, favorable toward China, and somewhat less favorable toward Britain. Congressmen with strong German, Irish Catholic, or Scandinavian constituencies generally supported isolationist policies. After Pearl Harbor, isolationism disappeared in Congress and was not a factor in the 1942 or 1944 elections. Some leading Republican isolationists, most notably Senator

Arthur Vandenberg

Arthur Hendrick Vandenberg Sr. (March 22, 1884April 18, 1951) was an American politician who served as a United States senator from Michigan from 1928 to 1951. A member of the Republican Party, he participated in the creation of the United Nat ...

of Michigan, Senator

Warren Austin

Warren Robinson Austin (November 12, 1877 – December 25, 1962) was an American politician and diplomat who served as United States Senator from Vermont and U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations.

A native of Highgate Center, Vermont, Austin wa ...

of Vermont, and Congressman

Everett Dirksen

Everett McKinley Dirksen (January 4, 1896 – September 7, 1969) was an American politician. A Republican Party (United States), Republican, he represented Illinois in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. As P ...

of Illinois, became leading internationalists. Republican Senator

Robert A. Taft

Robert Alphonso Taft Sr. (September 8, 1889 – July 31, 1953) was an American politician, lawyer, and scion of the Republican Party's Taft family. Taft represented Ohio in the United States Senate, briefly served as Senate majority le ...

stayed quiet on foreign and defense issues, while many of the energetic isolationists of the 1930s, including Hiram Johnson and William Borah, were in poor health or had seen their influence decline. During the war, there were no secret briefings, and members of Congress were often no better informed than the average newspaper reader. Congressman did pay attention to military installations in their district, but rarely raised issues of broader military or diplomatic scope, with the partial exception of postwar plans. Congress also established the

Truman Committee

The Truman Committee, formally known as the Senate Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, was a United States Congressional investigative body, headed by Senator Harry S. Truman. The bipartisan special committee was for ...

, which investigated wartime profiteering and other defects in war production. Debates on domestic policy were as heated as ever, and the major Republican gains in Congress in 1938 and 1942 gave the Conservative Coalition the dominant voice on most domestic issues.

Domestic legislation

The home front was subject to dynamic social changes throughout the war, though domestic issues were no longer Roosevelt's most urgent policy concern. The military buildup spurred economic growth. Unemployment fell in half from 7.7 million in early 1940 to 3.4 million in late 1941, and fell in half again to 1.5 million in late 1942, out of a labor force of 54 million. To pay for increased government spending, in 1941 Roosevelt proposed that Congress enact an income tax rate of 99.5% on all income over $100,000; when the proposal failed, he issued an executive order imposing an income tax of 100% on income over $25,000, which Congress rescinded. The

Revenue Act of 1942

The United States Revenue Act of 1942, Pub. L. 753, Ch. 619, 56 Stat. 798 (Oct. 21, 1942), increased individual income tax rates, increased corporate tax rates (top rate rose from 31% to 40%), and reduced the personal exemption amount from $1,500 t ...

instituted top tax rates as high as 94% (after accounting for the

excess profits tax

An excess profits tax, EPT, is a tax on returns or profits which exceed risk-adjusted ''normal'' returns. The concept of ''excess profit'' is very similar to that of economic rent. Excess profit taxes are usually imposed on monopolist industries ...

) and instituted the first federal

withholding tax

Tax withholding, also known as tax retention, pay-as-you-earn tax or tax deduction at source, is income tax paid to the government by the payer of the income rather than by the recipient of the income. The tax is thus withheld or deducted from the ...

. It also greatly increased the tax base; only four million Americans paid the federal income taxes before the war, while by the end of the war over 40 million Americans paid federal income taxes. In 1944, Roosevelt requested that Congress enact legislation which would tax all "unreasonable" profits, both corporate and individual, and thereby support his declared need for over $10 billion in revenue for the war and other government measures. Congress overrode Roosevelt's veto to pass a

smaller revenue bill raising $2 billion. Congress also abolished several New Deal agencies, including the CCC and the WPA.

Roosevelt's 1944 State of the Union Address advocated a set of basic economic rights Roosevelt dubbed as the

Second Bill of Rights

The Second Bill of Rights or Bill of Economic Rights was proposed by United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt during his State of the Union Address on Tuesday, January 11, 1944. In his address, Roosevelt suggested that the nation had come ...

. In the most ambitious domestic proposal of the era, veterans groups led by the

American Legion

The American Legion, commonly known as the Legion, is an Voluntary association, organization of United States, U.S. war veterans headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana. It comprises U.S. state, state, Territories of the United States, U.S. terr ...

secured the

G.I. Bill

The G.I. Bill, formally the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, was a law that provided a range of benefits for some of the returning World War II veterans (commonly referred to as G.I. (military), G.I.s). The original G.I. Bill expired in ...

, which created a massive benefits program for almost all men and women who served. Roosevelt had wanted a narrower bill focused more on poor people, but he was out-maneuvered by those on both his right and his left who, each for their own reasons, favored a blanket approach. Comprehensive coverage, regardless of income or combat experience, would avoid the prolonged disputes in the 1920s and 1930s over the aid to veterans. Benefits included a year of unemployment pay at $20 a week, tuition and living expense to attend high school or college, and low-cost loans to buy a home, farm or business. Of the fifteen million Americans who served in World War II, more than half would benefit from the educational opportunities provided for in the G.I. Bill.

War production

To coordinate war production and other aspects of the home front, Roosevelt established the

War Shipping Administration