Pope Gregory the Great on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the

In 579, Pelagius II chose Gregory as his ''

In 579, Pelagius II chose Gregory as his ''

Gregory was more inclined to remain retired into the monastic lifestyle of contemplation. In texts of all genres, especially those produced in his first year as pope, Gregory bemoaned the burden of office and mourned the loss of the undisturbed life of

prayer he had once enjoyed as a monk.

When he became pope in 590, among his first acts was writing a series of letters disavowing any ambition to the throne of Peter and praising the contemplative life of the monks. At that time, for various reasons, the

Gregory was more inclined to remain retired into the monastic lifestyle of contemplation. In texts of all genres, especially those produced in his first year as pope, Gregory bemoaned the burden of office and mourned the loss of the undisturbed life of

prayer he had once enjoyed as a monk.

When he became pope in 590, among his first acts was writing a series of letters disavowing any ambition to the throne of Peter and praising the contemplative life of the monks. At that time, for various reasons, the

In 590, Gregory could wait for Constantinople no longer. He organized the resources of the church into an administration for general relief. In doing so he evidenced a talent for and intuitive understanding of the principles of accounting, which was not to be invented for centuries. The church already had basic accounting documents: every

In 590, Gregory could wait for Constantinople no longer. He organized the resources of the church into an administration for general relief. In doing so he evidenced a talent for and intuitive understanding of the principles of accounting, which was not to be invented for centuries. The church already had basic accounting documents: every

The mainstream form of Western

The mainstream form of Western

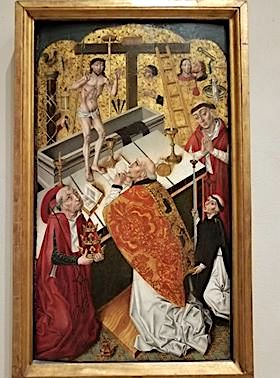

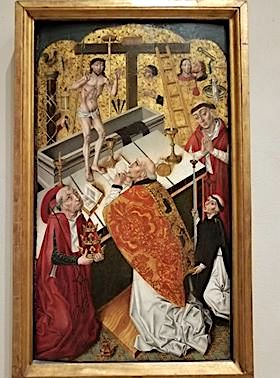

In art Gregory is usually shown in full pontifical robes with the

In art Gregory is usually shown in full pontifical robes with the  The late medieval subject of the Mass of St. Gregory shows a version of a 7th-century story that was elaborated in later

The late medieval subject of the Mass of St. Gregory shows a version of a 7th-century story that was elaborated in later

* ''Non , sed , si forent Christiani.''– "They are not

* ''Non , sed , si forent Christiani.''– "They are not

The relics of Saint Gregory are enshrined in

The relics of Saint Gregory are enshrined in

The current

The current

Library of Latin Texts - online (LLT-O)

The Book of Pastoral Rule

', trans. with intro and notes by George E. Demacopoulos (

Noch ein Höhlengleichnis. Zu einem metaphorischen Argument bei Gregor dem Großen

by Meinolf Schumacher (in German).

contains two of his letters.

* ttp://www.christianiconography.info/gregory.html Saint Gregory the Greatat th

Christian Iconography

website

from Caxon's translation of the Golden Legend

*

bishop of Rome

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregorian mission

The Gregorian missionJones "Gregorian Mission" ''Speculum'' p. 335 or Augustinian missionMcGowan "Introduction to the Corpus" ''Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature'' p. 17 was a Christian mission sent by Pope Gregory the Great in 596 to conver ...

, to convert the then largely pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. Gregory is also well known for his writings, which were more prolific than those of any of his predecessors as pope. The epithet Saint Gregory the Dialogist has been attached to him in Eastern Christianity

Eastern Christianity comprises Christian traditions and church families that originally developed during classical and late antiquity in Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, Asia Minor, the Caucasus, Northeast Africa, the Fertile Crescent and ...

because of his ''Dialogues

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literary and theatrical form that depicts such an exchange. As a philosophical or didactic device, it is chi ...

''. English translations of Eastern texts sometimes list him as Gregory "Dialogos", or the Anglo-Latinate equivalent "Dialogus".

A Roman senator

The Roman Senate ( la, Senātus Rōmānus) was a governing and advisory assembly in ancient Rome. It was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being established in the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in ...

's son and himself the prefect of Rome

The ''praefectus urbanus'', also called ''praefectus urbi'' or urban prefect in English, was prefect of the city of Rome, and later also of Constantinople. The office originated under the Roman kings, continued during the Republic and Empire, an ...

at 30, Gregory lived in a monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

he established on his family estate before becoming a papal ambassador and then pope. Although he was the first pope from a monastic

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic ...

background, his prior political experiences may have helped him to be a talented administrator. During his papacy, his administration greatly surpassed that of the emperors in improving the welfare of the people of Rome, and he challenged the theological views of Patriarch Eutychius of Constantinople

Eutychius (, ''Eutychios''; 512 – 5 April 582), considered a saint in the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christian traditions, was the patriarch of Constantinople from 552 to 565, and from 577 to 582. His feast is kept by the Orthodox Church ...

before the emperor Tiberius II

Tiberius II Constantine ( grc-gre, Τιβέριος Κωνσταντῖνος, Tiberios Konstantinos; died 14 August 582) was Eastern Roman emperor from 574 to 582. Tiberius rose to power in 574 when Justin II, prior to a mental breakdown, procl ...

. Gregory regained papal authority in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and sent missionaries to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, including Augustine of Canterbury

Augustine of Canterbury (early 6th century – probably 26 May 604) was a monk who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597. He is considered the "Apostle to the English" and a founder of the English Church.Delaney '' ...

and Paulinus of York

Paulinus (died 10 October 644) was a Roman missionary and the first Bishop of York. A member of the Gregorian mission sent in 601 by Pope Gregory I to Christianize the Anglo-Saxons from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism, Paulinus arrived in ...

. The realignment of barbarian allegiance to Rome from their Arian

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God t ...

Christian alliances shaped medieval Europe. Gregory saw Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

, Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 and ...

, and Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

align with Rome in religion. He also combated the Donatist

Donatism was a Christian sect leading to a schism in the Church, in the region of the Church of Carthage, from the fourth to the sixth centuries. Donatists argued that Christian clergy must be faultless for their ministry to be effective and t ...

heresy, popular particularly in North Africa at the time.

Throughout the Middle Ages, he was known as "the Father of Christian Worship" because of his exceptional efforts in revising the Roman worship of his day. His contributions to the development of the Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts, still in use in the Byzantine Rite

The Byzantine Rite, also known as the Greek Rite or the Rite of Constantinople, identifies the wide range of cultural, liturgical, and canonical practices that developed in the Eastern Christianity, Eastern Christian Church of Constantinople.

Th ...

, were so significant that he is generally recognized as its ''de facto'' author.

Gregory is one of the Latin Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

and a Doctor of the Church

Doctor of the Church (Latin: ''doctor'' "teacher"), also referred to as Doctor of the Universal Church (Latin: ''Doctor Ecclesiae Universalis''), is a title given by the Catholic Church to saints recognized as having made a significant contribu ...

. He is considered a saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

in the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

, Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and other ...

, various Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

denominations, and other Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

denominations. Immediately after his death, Gregory was canonized by popular acclaim. The Protestant reformer John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

admired Gregory greatly and declared in his ''Institutes'' that Gregory was the last good pope. He is the patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Eastern Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, family, or perso ...

of musicians, singers, students, and teachers.

Early life

Gregory was born around 540 in Rome, then recently reconquered by theEastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

from the Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic peoples, Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Goths, Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the larg ...

. His parents named him ''Gregorius'', which according to Ælfric of Eynsham

Ælfric of Eynsham ( ang, Ælfrīc; la, Alfricus, Elphricus; ) was an English abbot and a student of Æthelwold of Winchester, and a consummate, prolific writer in Old English of hagiography, homilies, biblical commentaries, and other genres. H ...

in ''An Homily on the Birth-Day of S. Gregory,'' "... is a Greek Name, which signifies in the Latin Tongue, ''Vigilantius'', that is in English, Watchful..." The medieval writer who provided this etymology did not hesitate to apply it to the life of Gregory. Ælfric states, "He was very diligent in God's Commandments."

Gregory was born into a wealthy noble Roman family with close connections to the church. His father, Gordianus, a patrician who served as a senator and for a time was the Prefect of the City of Rome,Thornton, pp 163–8 also held the position of Regionarius in the church, though nothing further is known about that position. Gregory's mother, Silvia

Silvia () is a female given name of Latin origin, with a male equivalent Silvio and English-language cognate Sylvia. The name originates from the Latin word for forest, ''Silva'', and its meaning is "spirit of the wood"; the mythological god of ...

, was well-born, and had a married sister, Pateria, in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. His mother and two paternal aunts are honored by Catholic and Orthodox churches as saints. Gregory's great-great-grandfather had been Pope Felix III

Pope Felix III (died 1 March 492) was the bishop of Rome from 13 March 483 to his death. His repudiation of the '' Henotikon'' is considered the beginning of the Acacian schism. He is commemorated on March 1.

Family

Felix was born into a Roman s ...

, the nominee of the Gothic king, Theodoric

Theodoric is a Germanic given name. First attested as a Gothic name in the 5th century, it became widespread in the Germanic-speaking world, not least due to its most famous bearer, Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths.

Overview

The name ...

.Dudden (1905), page 4. Gregory's election to the throne of St. Peter made his family the most distinguished clerical dynasty of the period.

The family owned and resided in a ''villa suburbana

A Roman villa was typically a farmhouse or country house built in the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, sometimes reaching extravagant proportions.

Typology and distribution

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD) distinguished two kinds of villas n ...

'' on the Caelian Hill

The Caelian Hill (; la, Collis Caelius; it, Celio ) is one of the famous seven hills of Rome.

Geography

The Caelian Hill is a sort of long promontory about long, to wide, and tall in the park near the Temple of Claudius. The hill over ...

, fronting the same street (now the Via di San Gregorio) as the former palaces of the Roman emperors on the Palatine Hill

The Palatine Hill (; la, Collis Palatium or Mons Palatinus; it, Palatino ), which relative to the seven hills of Rome is the centremost, is one of the most ancient parts of the city and has been called "the first nucleus of the Roman Empire." ...

opposite. The north of the street runs into the Colosseum

The Colosseum ( ; it, Colosseo ) is an oval amphitheatre in the centre of the city of Rome, Italy, just east of the Roman Forum. It is the largest ancient amphitheatre ever built, and is still the largest standing amphitheatre in the world to ...

; the south, the Circus Maximus

The Circus Maximus (Latin for "largest circus"; Italian: ''Circo Massimo'') is an ancient Roman chariot-racing stadium and mass entertainment venue in Rome, Italy. In the valley between the Aventine and Palatine hills, it was the first and lar ...

. In Gregory's day the ancient buildings were in ruins and were privately owned. Villas covered the area. Gregory's family also owned working estates in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and around Rome. Gregory later had portraits done in fresco in their former home on the Caelian and these were described 300 years later by John the Deacon. Gordianus was tall with a long face and light eyes. He wore a beard. Silvia

Silvia () is a female given name of Latin origin, with a male equivalent Silvio and English-language cognate Sylvia. The name originates from the Latin word for forest, ''Silva'', and its meaning is "spirit of the wood"; the mythological god of ...

was tall, had a round face, blue eyes and a cheerful look. They had another son whose name and fate are unknown.

Gregory was born into a period of upheaval in Italy. From 542 the so-called Plague of Justinian

The plague of Justinian or Justinianic plague (541–549 AD) was the first recorded major outbreak of the first plague pandemic, the first Old World pandemic of plague, the contagious disease caused by the bacterium ''Yersinia pestis''. The dis ...

swept through the provinces of the empire, including Italy. The plague caused famine, panic, and sometimes rioting. In some parts of the country, over a third of the population was wiped out or destroyed, with heavy spiritual and emotional effects on the people of the empire. Politically, although the Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period fr ...

had long since vanished in favor of the Gothic kings of Italy, during the 540s Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

was gradually retaken from the Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

by Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

, emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

ruling from Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. As the fighting was mainly in the north, the young Gregory probably saw little of it. Totila

Totila, original name Baduila (died 1 July 552), was the penultimate King of the Ostrogoths, reigning from 541 to 552 AD. A skilled military and political leader, Totila reversed the tide of the Gothic War, recovering by 543 almost all the t ...

sacked and vacated Rome in 546, destroying most of its population, but in 549 he invited those who were still alive to return to the empty and ruined streets. It has been hypothesized that young Gregory and his parents retired during that intermission to their Sicilian estates, to return in 549. The war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

was over in Rome by 552, and a subsequent invasion of the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

was defeated in 554. After that, there was peace in Italy, and the appearance of restoration, except that the central government now resided in Constantinople.

Like most young men of his position in Roman society, Gregory was well educated, learning grammar, rhetoric, the sciences, literature, and law; he excelled in all these fields. Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (30 November 538 – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours, which made him a leading prelate of the area that had been previously referred to as Gaul by the Romans. He was born Georgius Florenti ...

reported that "in grammar, dialectic and rhetoric ... he was second to none...." He wrote correct Latin but did not read or write Greek. He knew Latin authors, natural science, history, mathematics and music and had such a "fluency with imperial law" that he may have trained in it "as a preparation for a career in public life". Indeed, he became a government official, advancing quickly in rank to become, like his father, Prefect of Rome, the highest civil office in the city, when only thirty-three years old.

The monks of the Monastery of St. Andrew, established by Gregory at the ancestral home on the Caelian, had a portrait of him made after his death, which John the Deacon also saw in the 9th century. He reports the picture of a man who was "rather bald" and had a "tawny" beard like his father's and a face that was intermediate in shape between his mother's and father's. The hair that he had on the sides was long and carefully curled. His nose was "thin and straight" and "slightly aquiline". "His forehead was high." He had thick, "subdivided" lips and a chin "of a comely prominence" and "beautiful hands".

In the modern era, Gregory is often depicted as a man at the border, poised between the Roman and Germanic worlds, between East and West, and above all, perhaps, between the ancient and medieval epochs.

Monastic years

On his father's death, Gregory converted his family ''villa'' into amonastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

dedicated to Andrew the Apostle

Andrew the Apostle ( grc-koi, Ἀνδρέᾱς, Andréās ; la, Andrēās ; , syc, ܐܰܢܕ݁ܪܶܐܘܳܣ, ʾAnd’reʾwās), also called Saint Andrew, was an Apostles in the New Testament, apostle of Jesus according to the New Testament. He ...

(after his death it was rededicated as San Gregorio Magno al Celio

San Gregorio Magno al Celio, also known as San Gregorio al Celio or simply San Gregorio, is a church in Rome, Italy, which is part of a monastery of monks of the Camaldolese branch of the Benedictine Order. On 10 March 2012, the 1,000th annive ...

). In his life of contemplation, Gregory concluded that "in that silence of the heart, while we keep watch within through contemplation, we are as if asleep to all things that are without."

Gregory had a deep respect for the monastic life and particularly the vow of poverty. Thus, when it came to light that a monk lying on his death bed had stolen three gold pieces, Gregory, as a remedial punishment, forced the monk to die alone, then threw his body and coins on a manure heap to rot with a condemnation, "Take your money with you to perdition." Gregory believed that punishment of sins can begin, even in this life before death. However, in time, after the monk's death, Gregory had 30 Masses offered for the man to assist his soul before the final judgment

The Last Judgment, Final Judgment, Day of Reckoning, Day of Judgment, Judgment Day, Doomsday, Day of Resurrection or The Day of the Lord (; ar, یوم القيامة, translit=Yawm al-Qiyāmah or ar, یوم الدین, translit=Yawm ad-Dīn, ...

. He viewed being a monk as the "ardent quest for the vision of our Creator." His three paternal aunts were nuns renowned for their sanctity. However, after the eldest two, Trasilla and Emiliana

Trasilla (Tarsilla, Tharsilla, Thrasilla) and Emiliana were aunts of Gregory the Great, and venerated as virgin saints of the sixth century. They appear in the ''Roman Martyrology'', the former on 24 December, the latter on 5 January.

History

T ...

, died after seeing a vision of their ancestor Pope Felix III

Pope Felix III (died 1 March 492) was the bishop of Rome from 13 March 483 to his death. His repudiation of the '' Henotikon'' is considered the beginning of the Acacian schism. He is commemorated on March 1.

Family

Felix was born into a Roman s ...

, the youngest soon abandoned the religious life and married the steward of her estate. Gregory's response to this family scandal was that "many are called but few are chosen." Gregory's mother, Silvia

Silvia () is a female given name of Latin origin, with a male equivalent Silvio and English-language cognate Sylvia. The name originates from the Latin word for forest, ''Silva'', and its meaning is "spirit of the wood"; the mythological god of ...

, is herself a saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

.

Eventually, Pope Pelagius II

Pope Pelagius II (died 7 February 590) was the bishop of Rome from 26 November 579 to his death.

Life

Pelagius was a native of Rome, but probably of Ostrogothic descent, as his father's name was Winigild. Pelagius became Pope Benedict I's succes ...

ordained Gregory a deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Churc ...

and solicited his help in trying to heal the schism of the Three Chapters The Schism of the Three Chapters was a schism that affected Chalcedonian Christianity in Northern Italy lasting from 553 to 698 AD, although the area out of communion with Rome contracted throughout that time. It was part of a larger Three-Chapter C ...

in northern Italy

Northern Italy ( it, Italia settentrionale, it, Nord Italia, label=none, it, Alta Italia, label=none or just it, Nord, label=none) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. It consists of eight administrative regions ...

. However, this schism was not healed until well after Gregory was gone.

Apocrisiariate (579–585)

In 579, Pelagius II chose Gregory as his ''

In 579, Pelagius II chose Gregory as his ''apocrisiarius

An ''apocrisiarius'', the Latinized form of ''apokrisiarios'' ( el, ), sometimes Anglicized as apocrisiary, was a high diplomatic representative during Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages. The corresponding (purist) Latin term was ''respons ...

'' (ambassador to the imperial court in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

), a post Gregory would hold until 586. Gregory was part of the Roman delegation (both lay and clerical) that arrived in Constantinople in 578 to ask the emperor for military aid against the Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 and ...

.Ekonomou, 2007, p. 9. With the Byzantine military focused on the East, these entreaties proved unsuccessful; in 584, Pelagius II wrote to Gregory as ''apocrisiarius'', detailing the hardships that Rome was experiencing under the Lombards and asking him to ask Emperor Maurice

Maurice ( la, Mauricius or ''Mauritius''; ; 539 – 27 November 602) was Eastern Roman emperor from 582 to 602 and the last member of the Justinian dynasty. A successful general, Maurice was chosen as heir and son-in-law by his predecessor Tib ...

to send a relief force. Maurice, however, had long ago determined to limit his efforts against the Lombards to intrigue and diplomacy, pitting the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

against them. It soon became obvious to Gregory that the Byzantine emperors were unlikely to send such a force, given their more immediate difficulties with the Persians in the East and the Avars and Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

to the North.Ekonomou, 2007, p. 10.

According to Ekonomou, "if Gregory's principal task was to plead Rome's cause before the emperor, there seems to have been little left for him to do once imperial policy toward Italy became evident. Papal representatives who pressed their claims with excessive vigor could quickly become a nuisance and find themselves excluded from the imperial presence altogether". Gregory had already drawn an imperial rebuke for his lengthy canonical writings on the subject of the legitimacy of John III Scholasticus, who had occupied the Patriarchate of Constantinople for twelve years prior to the return of Eutychius Eutychius or Eutychios ( el, Εὐτύχιος, "fortunate") may refer to:

* Eutychius Proclus, 2nd-century grammarian

* Eutychius (exarch) (died 752), last Byzantine exarch of Ravenna

* Saint Eutychius, an early Christian martyr and companion of ...

(who had been driven out by Justinian). Gregory turned to cultivating connections with the Byzantine elite of the city, where he became extremely popular with the city's upper class, "especially aristocratic women". Ekonomou surmises that "while Gregory may have become spiritual father to a large and important segment of Constantinople's aristocracy, this relationship did not significantly advance the interests of Rome before the emperor". Although the writings of John the Deacon claim that Gregory "labored diligently for the relief of Italy", there is no evidence that his tenure accomplished much towards any of the objectives of Pelagius II.

Gregory's theological disputes with Patriarch Eutychius would leave a "bitter taste for the theological speculation of the East" with Gregory that continued to influence him well into his own papacy.Ekonomou, 2007, p. 11. According to Western sources, Gregory's very public debate with Eutychius culminated in an exchange before Tiberius II

Tiberius II Constantine ( grc-gre, Τιβέριος Κωνσταντῖνος, Tiberios Konstantinos; died 14 August 582) was Eastern Roman emperor from 574 to 582. Tiberius rose to power in 574 when Justin II, prior to a mental breakdown, procl ...

where Gregory cited a biblical passage in support of the view that Christ was corporeal and palpable after his Resurrection; allegedly as a result of this exchange, Tiberius II ordered Eutychius's writings burned. Ekonomou views this argument, though exaggerated in Western sources, as Gregory's "one achievement of an otherwise fruitless ''apokrisiariat''".Ekonomou, 2007, p. 12. In reality, Gregory was forced to rely on Scripture because he could not read the untranslated Greek authoritative works.

Gregory left Constantinople for Rome in 585, returning to his monastery on the Caelian Hill

The Caelian Hill (; la, Collis Caelius; it, Celio ) is one of the famous seven hills of Rome.

Geography

The Caelian Hill is a sort of long promontory about long, to wide, and tall in the park near the Temple of Claudius. The hill over ...

.Ekonomou, 2007, p. 13. Gregory was elected by acclamation

An acclamation is a form of election that does not use a ballot. It derives from the ancient Roman word ''acclamatio'', a kind of ritual greeting and expression of approval towards imperial officials in certain social contexts.

Voting Voice vot ...

to succeed Pelagius II in 590, when the latter died of the plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

spreading through the city. Gregory was approved by an Imperial ''iussio A ''prostagma'' ( el, πρόσταγμα) or ''prostaxis'' (πρόσταξις), both meaning "order, command", were documents issued by the Byzantine imperial chancery bearing an imperial decision or command, usually on administrative matters.

''P ...

'' from Constantinople the following September (as was the norm during the Byzantine Papacy

The Byzantine Papacy was a period of Byzantine domination of the Roman papacy from 537 to 752, when popes required the approval of the Byzantine Emperor for episcopal consecration, and many popes were chosen from the '' apocrisiarii'' (liaisons ...

).

Controversy with Eutychius

In Constantinople, Gregory took issue with the agedPatriarch Eutychius of Constantinople

Eutychius (, ''Eutychios''; 512 – 5 April 582), considered a saint in the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christian traditions, was the patriarch of Constantinople from 552 to 565, and from 577 to 582. His feast is kept by the Orthodox Church ...

, who had recently published a treatise, now lost, on the General Resurrection

General resurrection or universal resurrection is the belief in a resurrection of the dead, or resurrection from the dead ( Koine: , ''anastasis onnekron''; literally: "standing up again of the dead") by which most or all people who have died ...

. Eutychius maintained that the resurrected body "will be more subtle than air, and no longer palpable". Gregory opposed with the palpability of the risen Christ in Luke 24:39. As the dispute could not be settled, the Byzantine emperor

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as le ...

, Tiberius II Constantine

Tiberius II Constantine ( grc-gre, Τιβέριος Κωνσταντῖνος, Tiberios Konstantinos; died 14 August 582) was Eastern Roman emperor from 574 to 582. Tiberius rose to power in 574 when Justin II, prior to a mental breakdown, procl ...

, undertook to arbitrate. He decided in favor of palpability and ordered Eutychius' book to be burned. Shortly after both Gregory and Eutychius became ill; Gregory recovered, but Eutychius died on 5 April 582, at age 70. On his deathbed Eutychius recanted impalpability and Gregory dropped the matter.

Papacy

Gregory was more inclined to remain retired into the monastic lifestyle of contemplation. In texts of all genres, especially those produced in his first year as pope, Gregory bemoaned the burden of office and mourned the loss of the undisturbed life of

prayer he had once enjoyed as a monk.

When he became pope in 590, among his first acts was writing a series of letters disavowing any ambition to the throne of Peter and praising the contemplative life of the monks. At that time, for various reasons, the

Gregory was more inclined to remain retired into the monastic lifestyle of contemplation. In texts of all genres, especially those produced in his first year as pope, Gregory bemoaned the burden of office and mourned the loss of the undisturbed life of

prayer he had once enjoyed as a monk.

When he became pope in 590, among his first acts was writing a series of letters disavowing any ambition to the throne of Peter and praising the contemplative life of the monks. At that time, for various reasons, the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome ...

had not exerted effective leadership in the West since the pontificate of Gelasius I

Pope Gelasius I was the bishop of Rome from 1 March 492 to his death on 19 November 496. Gelasius was a prolific author whose style placed him on the cusp between Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages.The title of his biography by Walter Ullma ...

. The episcopacy in Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

was drawn from the great territorial families, and identified with them: the parochial horizon of Gregory's contemporary, Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (30 November 538 – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours, which made him a leading prelate of the area that had been previously referred to as Gaul by the Romans. He was born Georgius Florenti ...

, may be considered typical; in Visigothic

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kno ...

Spain the bishops had little contact with Rome; in Italy the territories which had ''de facto'' fallen under the administration of the papacy were beset by the violent Lombard dukes and the rivalry of the Byzantines in the Exarchate of Ravenna

The Exarchate of Ravenna ( la, Exarchatus Ravennatis; el, Εξαρχάτο της Ραβέννας) or of Italy was a lordship of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) in Italy, from 584 to 751, when the last exarch was put to death by the ...

and in the south.

Pope Gregory had strong convictions on missions: "Almighty God places good men in authority that He may impart through them the gifts of His mercy to their subjects. And this we find to be the case with the British over whom you have been appointed to rule, that through the blessings bestowed on you the blessings of heaven might be bestowed on your people also." He is credited with re-energizing the Church's missionary work among the non-Christian peoples of northern Europe. He is most famous for sending a mission, often called the Gregorian mission

The Gregorian missionJones "Gregorian Mission" ''Speculum'' p. 335 or Augustinian missionMcGowan "Introduction to the Corpus" ''Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature'' p. 17 was a Christian mission sent by Pope Gregory the Great in 596 to conver ...

, under Augustine of Canterbury

Augustine of Canterbury (early 6th century – probably 26 May 604) was a monk who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597. He is considered the "Apostle to the English" and a founder of the English Church.Delaney '' ...

, prior of Saint Andrew's, where he had perhaps succeeded Gregory, to evangelize the pagan Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

of England. It seems that the pope had never forgotten the English slaves whom he had once seen in the Roman Forum. The mission was successful, and it was from England that missionaries later set out for the Netherlands and Germany. The preaching of non-heretical Christian faith and the

elimination of all deviations from it was a key element in Gregory's worldview, and it constituted one of the major continuing policies of his pontificate. Pope Gregory the Great urged his followers on the value of bathing as a bodily need.

It is said he was declared a saint immediately after his death by "popular acclamation".

In his official documents, Gregory was the first to make extensive use of the term "Servant of the Servants of God

Servant of the servants of God ( la, servus servorum Dei) is one of the titles of the pope and is used at the beginning of papal bulls.

History

Pope Gregory I (pope from 590 to 604) was the first pope to use this title extensively to refer to h ...

" (''servus servorum Dei'') as a papal title, thus initiating a practice that was to be followed by most subsequent popes.

Alms

The Church had a practice from early times of passing on a large portion of the donations it received from its members asalms

Alms (, ) are money, food, or other material goods donated to people living in poverty. Providing alms is often considered an act of virtue or Charity (practice), charity. The act of providing alms is called almsgiving, and it is a widespread p ...

. As pope, Gregory did his utmost to encourage that high standard among church personnel. Gregory is known for his extensive administrative system of charitable relief of the poor at Rome. The poor were predominantly refugees from the incursions of the Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 and ...

. The philosophy under which he devised this system is that the wealth belonged to the poor and the church was only its steward. He received lavish donations from the wealthy families of Rome, who, following his own example, were eager, by doing so, to expiate their sins. He gave alms equally as lavishly both individually and en masse. He wrote in letters: "I have frequently charged you ... to act as my representative ... to relieve the poor in their distress ...." and "... I hold the office of steward to the property of the poor ...."

In Gregory's time, the Church in Rome received donations of many different kinds: consumables

Consumables (also known as consumable goods, non-durable goods, or soft goods) are goods that are intended to be consumed. People have, for example, always consumed food and water. Consumables are in contrast to durable goods. Disposable produc ...

such as food and clothing; investment property: real estate and works of art; and capital goods

The economic concept of a capital good (also called complex product systems (CoPS),H. Rush, "Managing innovation in complex product systems (CoPS)," IEE Colloquium on EPSRC Technology Management Initiative (Engineering & Physical Sciences Researc ...

, or revenue

In accounting, revenue is the total amount of income generated by the sale of goods and services related to the primary operations of the business.

Commercial revenue may also be referred to as sales or as turnover. Some companies receive reven ...

-generating property, such as the Sicilian latifundia

A ''latifundium'' (Latin: ''latus'', "spacious" and ''fundus'', "farm, estate") is a very extensive parcel of privately owned land. The latifundia of Roman history were great landed estates specializing in agriculture destined for export: grain, o ...

, or agricultural estates. The Church already had a system for circulating the consumables to the poor: associated with each of the main city churches was a ''diaconium'' or office of the deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Churc ...

. He was given a building from which the poor could apply for assistance at any time.

The circumstances in which Gregory became pope in 590 were of ruination. The Lombards held the greater part of Italy. Their depredations had brought the economy to a standstill. They camped nearly at the gates of Rome. The city itself was crowded with refugees from all walks of life, who lived in the streets and had few of the necessities of life. The seat of government was far from Rome in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

and appeared unable to undertake the relief of Italy. The pope had sent emissaries, including Gregory, asking for assistance, to no avail.

In 590, Gregory could wait for Constantinople no longer. He organized the resources of the church into an administration for general relief. In doing so he evidenced a talent for and intuitive understanding of the principles of accounting, which was not to be invented for centuries. The church already had basic accounting documents: every

In 590, Gregory could wait for Constantinople no longer. He organized the resources of the church into an administration for general relief. In doing so he evidenced a talent for and intuitive understanding of the principles of accounting, which was not to be invented for centuries. The church already had basic accounting documents: every expense

An expense is an item requiring an outflow of money, or any form of fortune in general, to another person or group as payment for an item, service, or other category of costs. For a tenant, rent is an expense. For students or parents, tuition is a ...

was recorded in journals called ''regesta'', "lists" of amounts, recipients and circumstances. Revenue was recorded in ''polyptici'', "books

A book is a medium for recording information in the form of writing or images, typically composed of many pages (made of papyrus, parchment, vellum, or paper) bound together and protected by a cover. The technical term for this physical ar ...

". Many of these polyptici were ledger

A ledger is a book or collection of accounts in which account transactions are recorded. Each account has an opening or carry-forward balance, and would record each transaction as either a debit or credit in separate columns, and the ending or ...

s recording the operating expenses of the church and the asset

In financial accountancy, financial accounting, an asset is any resource owned or controlled by a business or an economic entity. It is anything (tangible or intangible) that can be used to produce positive economic value. Assets represent value ...

s, the ''patrimonia''. A central papal administration, the ''notarii'', under a chief, the ''primicerius notariorum'', kept the ledgers and issued ''brevia patrimonii'', or lists of property for which each ''rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

'' was responsible.

Gregory began by aggressively requiring his churchmen to seek out and relieve needy persons and reprimanded them if they did not. In a letter to a subordinate in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

he wrote: "I asked you most of all to take care of the poor. And if you knew of people in poverty, you should have pointed them out ... I desire that you give the woman, Pateria, forty solidi

The ''solidus'' (Latin 'solid'; ''solidi'') or nomisma ( grc-gre, νόμισμα, ''nómisma'', 'coin') was a highly pure gold coin issued in the Late Roman Empire and Byzantine Empire. Constantine introduced the coin, and its weig ...

for the children's shoes and forty bushels of grain ...." Soon he was replacing administrators who would not cooperate with those who would and at the same time adding more in a build-up to a great plan that he had in mind. He understood that expenses must be matched by income. To pay for his increased expenses he liquidated the investment property and paid the expenses in cash according to a budget recorded in the polyptici. The churchmen were paid four times a year and also personally given a golden coin for their trouble.Dudden (1905) pages 248–249.

Money, however, was no substitute for food in a city that was on the brink of famine. Even the wealthy were going hungry in their villas. The church now owned between of revenue-generating farmland divided into large sections called ''patrimonia.'' It produced goods of all kinds, which were sold, but Gregory intervened and had the goods shipped to Rome for distribution in the ''diaconia''. He gave orders to step up production, set quotas and put an administrative structure in place to carry it out. At the bottom was the ''rusticus'' who produced the goods. Some rustici were or owned slaves. He turned over part of his produce to a ''conductor'' from whom he leased the land. The latter reported to an ''actionarius'', the latter to a ''defensor'' and the latter to a ''rector''. Grain, wine, cheese, meat, fish and oil began to arrive at Rome in large quantities, where it was given away for nothing as alms.

Distributions to qualified persons were monthly. However, a certain proportion of the population lived in the streets or were too ill or infirm to pick up their monthly food supply. To them Gregory sent out a small army of charitable persons, mainly monks, every morning with prepared food. It is said that he would not dine until the indigent were fed. When he did dine he shared the family table, which he had saved (and which still exists), with 12 indigent guests. To the needy living in wealthy homes he sent meals he had cooked with his own hands as gifts to spare them the indignity of receiving charity. Hearing of the death of an indigent in a back room he was depressed for days, entertaining for a time the conceit that he had failed in his duty and was a murderer.

These and other good deeds and charitable frame of mind completely won the hearts and minds of the Roman people. They now looked to the papacy for government, ignoring the state at Constantinople. The office of urban prefect went without candidates. From the time of Gregory the Great to the rise of Italian nationalism

Italian nationalism is a movement which believes that the Italians are a nation with a single homogeneous identity, and therefrom seeks to promote the cultural unity of Italy as a country. From an Italian nationalist perspective, Italianness is ...

the papacy was the most influential presence in Italy.

Works

Liturgical reforms

John the Deacon wrote that Pope Gregory I made a general revision of the liturgy of thePre-Tridentine Mass

Pre-Tridentine Mass refers to the variants of the liturgical rite of Mass in Rome before 1570, when, with his bull ''Quo primum'', Pope Pius V made the Roman Missal, as revised by him, obligatory throughout the Latin Church, except for those plac ...

, "removing many things, changing a few, adding some". In his own letters, Gregory remarks that he moved the ''Pater Noster

The Lord's Prayer, also called the Our Father or Pater Noster, is a central Christian prayer which Jesus taught as the way to pray. Two versions of this prayer are recorded in the gospels: a longer form within the Sermon on the Mount in the Gosp ...

'' (Our Father) to immediately after the Roman Canon The Canon of the Mass ( la, Canon Missæ), also known as the Canon of the Roman Mass and in the Mass of Paul VI as the Roman Canon or Eucharistic Prayer I, is the oldest anaphora used in the Roman Rite of Mass. The name ''Canon Missæ'' was used i ...

and immediately before the Fraction

A fraction (from la, fractus, "broken") represents a part of a whole or, more generally, any number of equal parts. When spoken in everyday English, a fraction describes how many parts of a certain size there are, for example, one-half, eight ...

. This position is still maintained today in the Roman Liturgy. The pre-Gregorian position is evident in the Ambrosian Rite

The Ambrosian Rite is a Catholic Western liturgical rite, named after Saint Ambrose, a bishop of Milan in the fourth century, which differs from the Roman Rite. It is used by some five million Catholics in the greater part of the Archdiocese o ...

. Gregory added material to the '' Hanc Igitur'' of the Roman Canon and established the nine ''Kyrie

Kyrie, a transliteration of Greek , vocative case of (''Kyrios''), is a common name of an important prayer of Christian liturgy, also called the Kyrie eleison ( ; ).

In the Bible

The prayer, "Kyrie, eleison," "Lord, have mercy" derives f ...

s'' (a vestigial remnant of the litany

Litany, in Christian worship and some forms of Judaic worship, is a form of prayer used in services and processions, and consisting of a number of petitions. The word comes through Latin ''litania'' from Ancient Greek λιτανεία (''litan ...

which was originally at that place) at the beginning of Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

. He also reduced the role of deacons in the Roman Liturgy.

Sacramentaries directly influenced by Gregorian reforms are referred to as ''Sacrementaria Gregoriana''. Roman and other Western liturgies since this era have a number of prayers that change to reflect the feast or liturgical season; these variations are visible in the collect

The collect ( ) is a short general prayer of a particular structure used in Christian liturgy.

Collects appear in the liturgies of Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Anglican, Methodist, Lutheran, and Presbyterian churches, among oth ...

s and preface

__NOTOC__

A preface () or proem () is an introduction to a book or other literary work written by the work's author. An introductory essay written by a different person is a '' foreword'' and precedes an author's preface. The preface often closes ...

s as well as in the Roman Canon itself.

Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts

In theEastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

and Eastern Catholic Churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also called the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (''sui iuris'') particular churches of th ...

, Gregory is credited as the primary influence in constructing the more penitential Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts, a fully separate form of the Divine Liturgy

Divine Liturgy ( grc-gre, Θεία Λειτουργία, Theia Leitourgia) or Holy Liturgy is the Eucharistic service of the Byzantine Rite, developed from the Antiochene Rite of Christian liturgy which is that of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of C ...

in the Byzantine Rite

The Byzantine Rite, also known as the Greek Rite or the Rite of Constantinople, identifies the wide range of cultural, liturgical, and canonical practices that developed in the Eastern Christianity, Eastern Christian Church of Constantinople.

Th ...

adapted to the needs of the season of Great Lent

Great Lent, or the Great Fast, (Greek: Μεγάλη Τεσσαρακοστή or Μεγάλη Νηστεία, meaning "Great 40 Days," and "Great Fast," respectively) is the most important fasting season of the church year within many denominat ...

. Its Roman Rite

The Roman Rite ( la, Ritus Romanus) is the primary liturgical rite of the Latin Church, the largest of the ''sui iuris'' particular churches that comprise the Catholic Church. It developed in the Latin language in the city of Rome and, while dist ...

equivalent is the Mass of the Presanctified

The Mass of the Presanctified (Latin: ''missa præsanctificatorum'', Greek: ''leitourgia ton proegiasmenon'') is Christian liturgy traditionally celebrated on Good Friday in which the consecration is not performed. Instead, the Blessed Sacrament ...

used only on Good Friday

Good Friday is a Christian holiday commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus and his death at Calvary. It is observed during Holy Week as part of the Paschal Triduum. It is also known as Holy Friday, Great Friday, Great and Holy Friday (also Hol ...

. The Syriac Syriac may refer to:

*Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages a ...

Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts continues to be used in the Malankara Rite

The Malankara Rite is the form of the West Syriac liturgical rite practiced by several churches of the Saint Thomas Christian community in Kerala, India. West Syriac liturgy was brought to India by the Syriac Orthodox Bishop of Jerusalem, Gregorio ...

, a variant of the West Syrian Rite

The West Syriac Rite, also called Syro-Antiochian Rite, is an Eastern Christian liturgical rite that employs the Divine Liturgy of Saint James in the West Syriac dialect. It is practised in the Maronite Church, the Syriac Orthodox Chur ...

historically practiced in the Malankara Church

The Malankara Church, also known as ''Puthenkur'' and more popularly as Jacobite Syrians, is the historic unified body of West Syriac Saint Thomas Christian denominations which claim ultimate origins from the missions of Thomas the Apostle. ...

of India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, and now practiced by the several churches that descended from it and at some occasions in the Assyrian Church of the East

The Assyrian Church of the East,, ar, كنيسة المشرق الآشورية sometimes called Church of the East, officially the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East,; ar, كنيسة المشرق الآشورية الرسول� ...

.

Gregorian chant

The mainstream form of Western

The mainstream form of Western plainchant

Plainsong or plainchant (calque from the French ''plain-chant''; la, cantus planus) is a body of chants used in the liturgies of the Western Church. When referring to the term plainsong, it is those sacred pieces that are composed in Latin text. ...

, standardized in the late 9th century, was attributed to Pope Gregory I and so took the name of Gregorian chant. The earliest such attribution is in John the Deacon's 873 biography of Gregory, almost three centuries after the pope's death, and the chant that bears his name "is the result of the fusion of Roman and Frankish elements which took place in the Franco-German empire under Pepin, Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

and their successors".

Writings

Gregory is commonly credited with founding the medieval papacy and so many attribute the beginning of medieval spirituality to him. Gregory is the only pope between the fifth and the eleventh centuries whose correspondence and writings have survived enough to form a comprehensive ''corpus''. Some of his writings are: *''Moralia in Job

''Moralia in Job'', also called ''Moralia, sive Expositio in Job'' or ''Magna Moralia'', is a commentary on the '' Book of Job'' by Gregory the Great, written between 578 and 595. It was begun when Gregory was at the court of Emperor Tiberius II ...

''. This is one of the longest patristic works. It was possibly finished as early as 591. It is based on talks Gregory gave on the Book of Job to his 'brethren' who accompanied him to Constantinople. The work as we have it is the result of Gregory's revision and completion of it soon after his accession to the papal office.

* ''Pastoral Care

Pastoral care is an ancient model of emotional, social and spiritual support that can be found in all cultures and traditions.

The term is considered inclusive of distinctly non-religious forms of support, as well as support for people from rel ...

'' (''Liber regulae pastoralis''), in which he contrasted the role of bishops as pastors of their flock with their position as nobles of the church: the definitive statement of the nature of the episcopal office. This was probably begun before his election as pope and finished in 591.

* ''Dialogues

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literary and theatrical form that depicts such an exchange. As a philosophical or didactic device, it is chi ...

'', a collection of four books of miracles, signs, wonders, and healings done by the holy men, mostly monastic, of sixth-century Italy, with the second book entirely devoted to a popular life of Saint Benedict

Benedict of Nursia ( la, Benedictus Nursiae; it, Benedetto da Norcia; 2 March AD 480 – 21 March AD 548) was an Christianity in Italy, Italian Christian monk, writer, and theologian who is venerated in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Ortho ...

* Sermons

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. E ...

, including:

** The sermons include the 22 ''Homilae in Hiezechielem ''(''Homilies on Ezekiel''), dealing with Ezekiel 1.1–4.3 in Book One, and Ezekiel 40 in Book 2. These were preached during 592–3, the years that the Lombards besieged Rome, and contain some of Gregory's most profound mystical teachings. They were revised eight years later.

** The ''Homilae xl in Evangelia ''(''Forty Homilies on the Gospels'') for the liturgical year, delivered during 591 and 592, which were seemingly finished by 593. A papyrus fragment from this codex survives in the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

, London, UK.

** ''Expositio in Canticis Canticorum. ''Only 2 of these sermons on the Song of Songs survive, discussing the text up to Song 1.9.

* ''In Librum primum regum expositio ''(''Commentary on 1 Kings''), which scholars now think that this is a work by 12th century monk, Peter of Cava

Peter of Pappacarbone ( it, San Pietro di Pappacarbone) (died 4 March 1123) was an Italian abbot, bishop, and saint. He was abbot of La Trinità della Cava, located at Cava de' Tirreni. Born in Salerno, he had first been a monk at Cava under Le ...

, who used no longer extant Gregorian material.

*Copies of some 854 letters have survived. During Gregory's time, copies of papal letters were made by scribes into a ''Registrum ''(''Register''), which was then kept in the ''scrinium''. It is known that in the 9th century, when John the Deacon composed his ''Life'' of Gregory, the ''Registrum'' of Gregory's letters was formed of 14 papyrus rolls (though it is difficult to estimate how many letters this may have represented). Though these original rolls are now lost, the 854 letters have survived in copies made at various later times, the largest single batch of 686 letters being made by order of Adrian I

Pope Adrian I ( la, Hadrianus I; died 25 December 795) was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 1 February 772 to his death. He was the son of Theodore, a Roman nobleman.

Adrian and his predecessors had to contend with periodic ...

(772–95). The majority of the copies, dating from the 10th to the 15th century, are stored in the Vatican Library

The Vatican Apostolic Library ( la, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, it, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana), more commonly known as the Vatican Library or informally as the Vat, is the library of the Holy See, located in Vatican City. Formally es ...

.

Gregory wrote over 850 letters in the last 13 years of his life (590–604) that give us an accurate picture of his work. A truly autobiographical presentation is nearly impossible for Gregory. The development of his mind and personality remains purely speculative in nature.

Opinions of the writings of Gregory vary. "His character strikes us as an ambiguous and enigmatic one," the Jewish Canadian-American popularist Cantor

A cantor or chanter is a person who leads people in singing or sometimes in prayer. In formal Jewish worship, a cantor is a person who sings solo verses or passages to which the choir or congregation responds.

In Judaism, a cantor sings and lead ...

observed. "On the one hand he was an able and determined administrator, a skilled and clever diplomat, a leader of the greatest sophistication and vision; but on the other hand, he appears in his writings as a superstitious and credulous monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedica ...

, hostile to learning, crudely limited as a theologian, and excessively devoted to saints, miracle

A miracle is an event that is inexplicable by natural or scientific lawsOne dictionary define"Miracle"as: "A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divin ...

s, and relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains of a saint or the personal effects of the saint or venerated person preserved for purposes of veneration as a tangi ...

s".

Identification of three figures in the Gospels

Gregory was among those who identifiedMary Magdalene

Mary Magdalene (sometimes called Mary of Magdala, or simply the Magdalene or the Madeleine) was a woman who, according to the four canonical gospels, traveled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to crucifixion of Jesus, his cru ...

with Mary of Bethany

Mary of Bethany is a biblical figure mentioned only by name in the Gospel of John in the Christian New Testament. Together with her siblings Lazarus and Martha, she is described by John as living in the village of Bethany, a small village in Juda ...

, whom John 12:1-8 recounts as having anointed Jesus with precious ointment, an event that some interpret as being the same as the anointing of Jesus

The anointings of Jesus’s head or feet are events recorded in the four gospels. The account in Matthew 26, Mark 14, and John 12 takes place on the Holy Wednesday of Holy Week at the house of Simon the Leper in Bethany, a village in Judae ...

performed by a woman that Luke (alone among the synoptic Gospels

The gospels of Gospel of Matthew, Matthew, Gospel of Mark, Mark, and Gospel of Luke, Luke are referred to as the synoptic Gospels because they include many of the same stories, often in a similar sequence and in similar or sometimes identical ...

) recounts as a sinner. Preaching on the passage in the Gospel of Luke

The Gospel of Luke), or simply Luke (which is also its most common form of abbreviation). tells of the origins, birth, ministry, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ. Together with the Acts of the Apostles, it makes up a two-volu ...

, Gregory remarked: "This woman, whom Luke calls a sinner and John calls Mary, I think is the Mary from whom Mark reports that seven demons were cast out." Modern biblical scholars distinguish these as three separate figures/persons, but within the general populace (and even some seminaries

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy, ...

), they are still believed to refer to the same person.

Iconography

In art Gregory is usually shown in full pontifical robes with the

In art Gregory is usually shown in full pontifical robes with the tiara

A tiara (from la, tiara, from grc, τιάρα) is a jeweled head ornament. Its origins date back to ancient Greece and Rome. In the late 18th century, the tiara came into fashion in Europe as a prestigious piece of jewelry to be worn by women ...

and double cross, despite his actual habit of dress. Earlier depictions are more likely to show a monastic tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

and plainer dress. Orthodox icons

An icon () is a religious work of art, most commonly a painting, in the cultures of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Catholic churches. They are not simply artworks; "an icon is a sacred image used in religious devotion". The most ...

traditionally show St. Gregory vested as a bishop holding a Gospel Book

A Gospel Book, Evangelion, or Book of the Gospels (Greek: , ''Evangélion'') is a codex or bound volume containing one or more of the four Gospels of the Christian New Testament – normally all four – centering on the life of Jesus of Nazar ...

and blessing with his right hand. It is recorded that he permitted his depiction with a square halo, then used for the living. A dove is his attribute

Attribute may refer to:

* Attribute (philosophy), an extrinsic property of an object

* Attribute (research), a characteristic of an object

* Grammatical modifier, in natural languages

* Attribute (computing), a specification that defines a prope ...

, from the well-known story attributed to his friend Peter the Deacon, who tells that when the pope was dictating his homilies on Ezechiel

Ezekiel (; he, יְחֶזְקֵאל ''Yəḥezqēʾl'' ; in the Septuagint written in grc-koi, Ἰεζεκιήλ ) is the central protagonist of the Book of Ezekiel in the Hebrew Bible.

In Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Ezekiel is ackn ...

a curtain was drawn between his secretary and himself. As, however, the pope remained silent for long periods at a time, the servant made a hole in the curtain and, looking through, beheld a dove seated upon Gregory's head with its beak between his lips. When the dove withdrew its beak the pope spoke and the secretary took down his words; but when he became silent the servant again applied his eye to the hole and saw the dove had replaced its beak between his lips.

Ribera's oil painting of ''Saint Gregory the Great'' () is from the Giustiniani collection. The painting is conserved in the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica

The Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica or National Gallery of Ancient Art is an art museum in Rome, Italy. It is the principal national collection of older paintings in Rome – mostly from before 1800; it does not hold any antiquities. It has two ...

, Rome. The face of Gregory is a caricature of the features described by John the Deacon: total baldness, outthrust chin, beak-like nose, whereas John had described partial baldness, a mildly protruding chin, slightly aquiline nose and strikingly good looks. In this picture also Gregory has his monastic back on the world, which the real Gregory, despite his reclusive intent, was seldom allowed to have.

This scene is shown as a version of the traditional Evangelist portrait

Evangelist portraits are a specific type of miniature included in ancient and mediaeval illuminated manuscript Gospel Books, and later in Bibles and other books, as well as other media. Each Gospel of the Four Evangelists, the books of Matthew, ...

(where the Evangelists' symbols are also sometimes shown dictating) from the tenth century onwards. An early example is the dedication miniature

A presentation miniature or dedication miniature is a miniature painting often found in illuminated manuscripts, in which the patron or donor is presented with a book, normally to be interpreted as the book containing the miniature itself.Brown ...

from an eleventh-century manuscript of Gregory's ''Moralia in Job''. The miniature shows the scribe, Bebo of Seeon Abbey

Seeon Abbey (german: Kloster Seeon) is a former Benedictine monastery in the municipality of Seeon-Seebruck in the rural district of Traunstein in Bavaria, Germany.

History

Seeon Abbey was founded in 994 by the Bavarian ''Pfalzgraf'' Aribo I, a ...

, presenting the manuscript to the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

, Henry II. In the upper left the author is seen writing the text under divine inspiration. Usually the dove is shown whispering in Gregory's ear for a clearer composition.

The late medieval subject of the Mass of St. Gregory shows a version of a 7th-century story that was elaborated in later

The late medieval subject of the Mass of St. Gregory shows a version of a 7th-century story that was elaborated in later hagiography

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian hagiographies migh ...

. Gregory is shown saying Mass when Christ as the Man of Sorrows

Man of Sorrows, a biblical term, is paramount among the prefigurations of the Messiah identified by the Bible in the passages of Isaiah 53 (''Servant songs'') in the Hebrew Bible. It is also an iconic devotional image that shows Christ, usually ...

appears on the altar. The subject was most common in the 15th and 16th centuries, and reflected growing emphasis on the Real Presence

The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist is the Christian doctrine that Jesus Christ is present in the Eucharist, not merely symbolically or metaphorically, but in a true, real and substantial way.

There are a number of Christian denominati ...

, and after the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...