Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the ...

. Poland is divided into sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 million people, and the seventh largest EU country, covering a combined area of . It extends from the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and fr ...

in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordering seven countries. The territory is characterised by a varied landscape, diverse ecosystems, and temperate transitional climate. The capital and largest city is Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is official ...

; other major cities include Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 159 ...

, Wrocław

Wrocław (; , . german: Breslau, , also known by other names) is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, roughly ...

, Łódź

Łódź, also rendered in English as Lodz, is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately south-west of Warsaw. The city's coat of arms is an example of cant ...

, Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

, and Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

.

Humans have been present on Polish soil since the Lower Paleolithic, with continuous settlement since the end of the Last Glacial Period over 12,000 years ago. Culturally diverse throughout late antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English has ...

, in the early medieval period the region became inhabited by the tribal Polans who gave Poland its name. The process of establishing statehood

A state is a centralized political organization that imposes and enforces rules over a population within a territory. There is no undisputed definition of a state. One widely used definition comes from the German sociologist Max Weber: a "sta ...

coincided with the conversion of a pagan ruler of the Polans to Christianity, under the auspices of the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in 966. Subsequent territorial expansion led to the creation of the Kingdom of Poland in 1025. By the mid-14th century, Poland became a major European power and began gradually integrating with Lithuania, resulting in the formation of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ...

in 1569. For the next two centuries, the Commonwealth was one of the great powers of Europe, governed by a uniquely liberal political system that adopted Europe's first modern constitution in 1791.

With the passing of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

and the prosperous Polish Golden Age in the late 16th century, Poland–Lithuania was weakened by social and political turmoil that led to its partition by neighbouring states at the end of the 18th century. Poland regained its independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the s ...

at the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

with the founding of the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

. In September 1939, the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

by Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

marked the beginning of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, which resulted in the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

and millions of Polish casualties. Forced into the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

during the global Cold War, the Polish People's Republic

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million nea ...

was a founding signatory of the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

. Through the emergence and contributions of the Solidarity movement, the communist government was dissolved and Poland re-established itself as a democratic state in 1989.

Poland is a unitary parliamentary republic

A parliamentary republic is a republic that operates under a parliamentary system of government where the executive branch (the government) derives its legitimacy from and is accountable to the legislature (the parliament). There are a number ...

, with its bicameral legislature comprising the Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

and the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

. The country is considered a middle power, with a developed market and high-income economy that is the sixth largest in the EU by nominal GDP and the fifth largest by GDP (PPP). Poland enjoys a very high standard of living, safety, and economic freedom

Economic freedom, or economic liberty, is the ability of people of a society to take economic actions. This is a term used in economic and policy debates as well as in the philosophy of economics. One approach to economic freedom comes from the ...

, as well as free university education and universal health care. The country has 17 UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. I ...

World Heritage Sites, 15 of which are cultural. Poland is a founding member state of the United Nations and a member of the World Trade Organization

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an intergovernmental organization that regulates and facilitates international trade. With effective cooperation

in the United Nations System, governments use the organization to establish, revise, and ...

, OECD

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; french: Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques, ''OCDE'') is an intergovernmental organisation with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate ...

, NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

, and the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been ...

(including the Schengen Area

The Schengen Area ( , ) is an area comprising 27 European countries that have officially abolished all passport and all other types of border control at their mutual borders. Being an element within the wider area of freedom, security and ...

).

Etymology

The native Polish name for Poland is . The name is derived from the Polans, a West Slavic tribe who inhabited the Warta River basin of present-day Greater Poland region (6th–8th century CE). The tribe's name stems from the Proto-Slavic noun ''pole'' meaning field, which in-itself originates from theProto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo- ...

word ''*pleh₂-'' indicating flatland. The etymology alludes to the topography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the land forms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary s ...

of the region and the flat landscape of Greater Poland. During the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

form ''Polonia'' was widely used throughout Europe.

The country's alternative archaic name is '' Lechia'' and its root syllable remains in official use in several languages, notably Hungarian, Lithuanian

Lithuanian may refer to:

* Lithuanians

* Lithuanian language

* The country of Lithuania

* Grand Duchy of Lithuania

* Culture of Lithuania

* Lithuanian cuisine

* Lithuanian Jews as often called "Lithuanians" (''Lita'im'' or ''Litvaks'') by other Jew ...

, and Persian. The exonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, o ...

possibly derives from either Lech, a legendary ruler of the Lechites

Lechites (, german: Lechiten), also known as the Lechitic tribes (, german: Lechitische Stämme), is a name given to certain West Slavs, West Slavic tribes who inhabited modern-day Poland and eastern Germany, and were speakers of the Lechitic lang ...

, or from the Lendians, a West Slavic tribe that dwelt on the south-easternmost edge of Lesser Poland. The origin of the tribe's name lies in the Old Polish

The Old Polish language ( pl, język staropolski, staropolszczyzna) was a period in the history of the Polish language between the 10th and the 16th centuries. It was followed by the Middle Polish language.

The sources for the study of the Old ...

word ''lęda'' (plain). Initially, both names ''Lechia'' and ''Polonia'' were used interchangeably when referring to Poland by chroniclers during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

.

History

Prehistory and protohistory

The first Stone Age archaic humans and ''

The first Stone Age archaic humans and ''Homo erectus

''Homo erectus'' (; meaning " upright man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Pleistocene, with its earliest occurrence about 2 million years ago. Several human species, such as ''H. heidelbergensis'' and ''H. antecessor' ...

'' species settled what was to become Poland approximately 500,000 years ago, though the ensuing hostile climate prevented early humans from founding more permanent encampments. The arrival of ''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

'' and anatomically modern humans coincided with the climatic discontinuity at the end of the Last Glacial Period ( Northern Polish glaciation 10,000 BC), when Poland became habitable. Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several part ...

excavations indicated broad-ranging development in that era; the earliest evidence of European cheesemaking (5500 BC) was discovered in Polish Kuyavia, and the Bronocice pot is incised with the earliest known depiction of what may be a wheeled vehicle (3400 BC).

The period spanning the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

and the Early Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly app ...

(1300 BC–500 BC) was marked by an increase in population density, establishment of palisaded settlements ( gords) and the expansion of Lusatian culture. A significant archaeological find from the protohistory of Poland is a fortified settlement at Biskupin, attributed to the Lusatian culture of the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

(mid-8th century BC).

Throughout antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

(400 BC–500 AD), many distinct ancient populations inhabited the territory of present-day Poland, notably Celtic, Scythia

Scythia ( Scythian: ; Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) or Scythica (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ), also known as Pontic Scythia, was a kingdom created by the Scythians during the 6th to 3rd centuries BC in the Pontic–Caspian steppe.

...

n, Germanic, Sarmatian

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th ...

, Baltic and Slavic tribes. Furthermore, archaeological findings confirmed the presence of Roman Legions

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period of ...

sent to protect the amber trade. The Polish tribes emerged following the second wave of the Migration Period around the 6th century AD; they were Slavic and may have included assimilated remnants of peoples that earlier dwelled in the area. Beginning in the early 10th century, the Polans would come to dominate other Lechitic tribes in the region, initially forming a tribal federation and later a centralised monarchical state.

Kingdom of Poland

Poland began to form into a recognisable unitary and territorial entity around the middle of the 10th century under the

Poland began to form into a recognisable unitary and territorial entity around the middle of the 10th century under the Piast dynasty

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I (c. 930–992). The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of king Casimir III the Great.

Branc ...

. In 966, ruler of the Polans Mieszko I accepted Christianity under the auspices of the Roman Church with the Baptism of Poland. In 968, a missionary bishopric

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

was established in Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

. An incipit

The incipit () of a text is the first few words of the text, employed as an identifying label. In a musical composition, an incipit is an initial sequence of notes, having the same purpose. The word ''incipit'' comes from Latin and means "it b ...

titled Dagome iudex first defined Poland's geographical boundaries with its capital in Gniezno

Gniezno (; german: Gnesen; la, Gnesna) is a city in central-western Poland, about east of Poznań. Its population in 2021 was 66,769, making it the sixth-largest city in the Greater Poland Voivodeship. One of the Piast dynasty's chief cities, ...

and affirmed that its monarchy was under the protection of the Apostolic See

An apostolic see is an episcopal see whose foundation is attributed to one or more of the apostles of Jesus or to one of their close associates. In Catholicism the phrase, preceded by the definite article and usually capitalized, refers to the Se ...

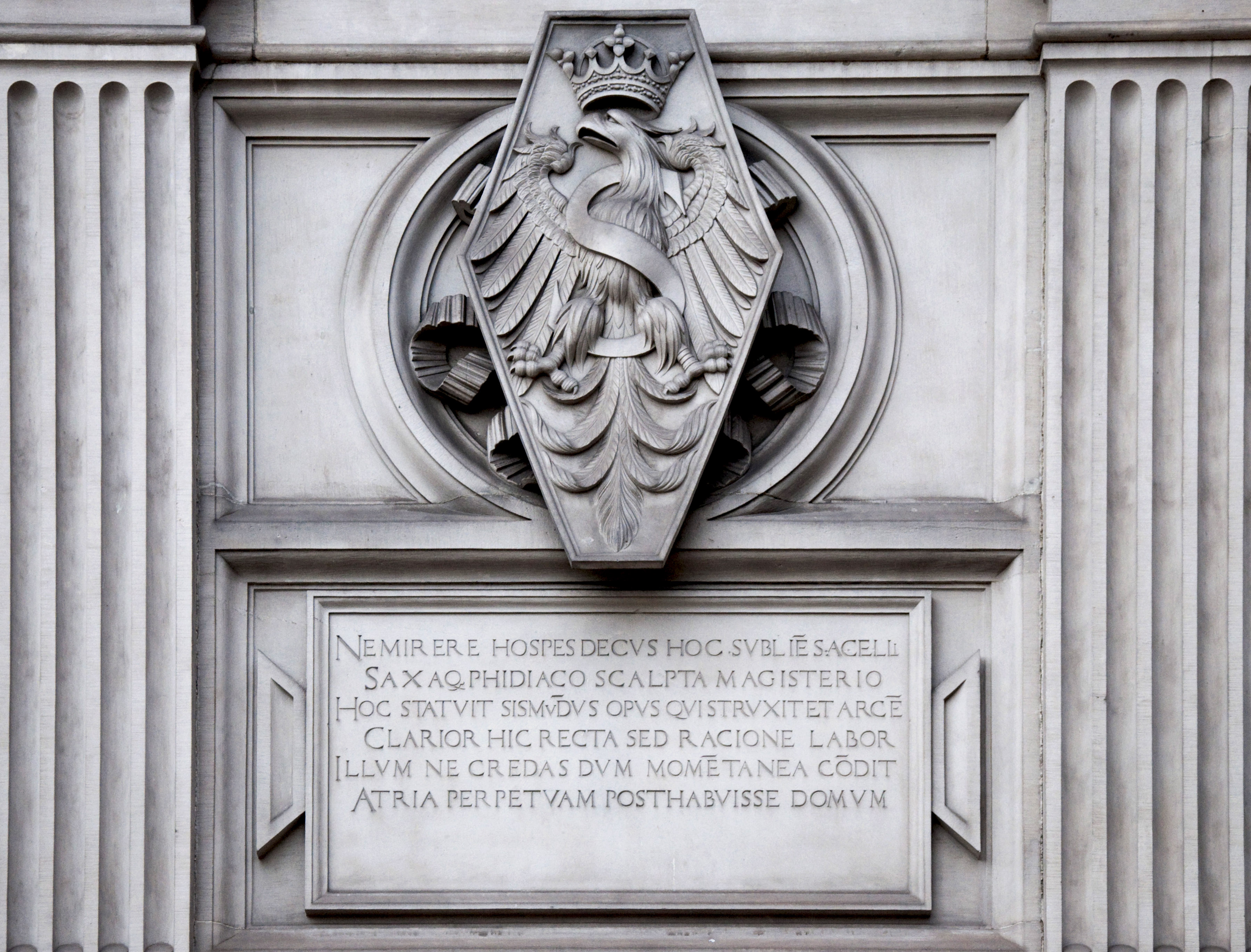

. The country's early origins were described by Gallus Anonymus in , the oldest Polish chronicle. An important national event of the period was the martyrdom of Saint Adalbert, who was killed by Prussian pagans in 997 and whose remains were reputedly bought back for their weight in gold by Mieszko's successor, Bolesław I the Brave.

In 1000, at the Congress of Gniezno, Bolesław obtained the right of investiture

Investiture (from the Latin preposition ''in'' and verb ''vestire'', "dress" from ''vestis'' "robe") is a formal installation or ceremony that a person undergoes, often related to membership in Christian religious institutes as well as Christian k ...

from Otto III, Holy Roman Emperor

Otto III (June/July 980 – 23 January 1002) was Holy Roman Emperor from 996 until his death in 1002. A member of the Ottonian dynasty, Otto III was the only son of the Emperor Otto II and his wife Theophanu.

Otto III was crowned as King of Ge ...

, who assented to the creation of additional bishoprics and an archdioceses in Gniezno. Three new dioceses were subsequently established in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 159 ...

, Kołobrzeg, and Wrocław

Wrocław (; , . german: Breslau, , also known by other names) is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, roughly ...

. Also, Otto bestowed upon Bolesław royal regalia and a replica of the Holy Lance

The Holy Lance, also known as the Lance of Longinus (named after Saint Longinus), the Spear of Destiny, or the Holy Spear, is the lance that pierced the side of Jesus as he hung on the cross during his crucifixion.

Biblical references

The l ...

, which were later used at his coronation as the first King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16t ...

in , when Bolesław received permission for his coronation from Pope John XIX. Bolesław also expanded the realm considerably by seizing parts of German Lusatia, Czech Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

Th ...

, Upper Hungary and southwestern regions of the Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

.

paganism

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

in Poland was not instantaneous and resulted in the pagan reaction of the 1030s. In 1031, Mieszko II Lambert lost the title of king and fled amidst the violence. The unrest led to the transfer of the capital to Kraków in 1038 by Casimir I the Restorer. In 1076, Bolesław II re-instituted the office of king, but was banished in 1079 for murdering his opponent, Bishop Stanislaus. In 1138, the country fragmented into five principalities when Bolesław III Wrymouth

Bolesław III Wrymouth ( pl, Bolesław III Krzywousty; 20 August 1086 – 28 October 1138), also known as Boleslaus the Wry-mouthed, was the duke of Lesser Poland, Silesia and Sandomierz between 1102 and 1107 and over the whole of Poland betwee ...

divided his lands among his sons. These comprised Lesser Poland, Greater Poland, Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is spli ...

, Masovia and Sandomierz, with intermittent hold over Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to t ...

. In 1226, Konrad I of Masovia invited the Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

to aid in combating the Baltic Prussians; a decision that later led to centuries of warfare with the Knights.

In the first half of the 13th century, Henry I the Bearded and Henry II the Pious

Henry II the Pious ( pl, Henryk II Pobożny; 1196 – 9 April 1241) was Duke of Silesia and High Duke of Poland as well as Duke of South-Greater Poland from 1238 until his death. Between 1238 and 1239 he also served as regent of Sandomierz a ...

aimed to unite the fragmented dukedoms, but the Mongol invasion and the death of Henry II in battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

hindered the unification. As a result of the devastation which followed, depopulation and the demand for craft labour spurred a migration of German and Flemish settlers into Poland, which was encouraged by the Polish dukes. In 1264, the Statute of Kalisz introduced unprecedented autonomy for the Polish Jews

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the lon ...

, who came to Poland fleeing persecution elsewhere in Europe.

In 1320, Władysław I the Short became the first king of a reunified Poland since Przemysł II

Przemysł II ( also given in English and Latin as ''Premyslas'' or ''Premislaus'' or in Polish as '; 14 October 1257 – 8 February 1296) was the Duke of Poznań from 1257–1279, of Greater Poland from 1279 to 1296, of Kraków from 1290 to 1291 ...

in 1296, and the first to be crowned at Wawel Cathedral in Kraków. Beginning in 1333, the reign of Casimir III the Great was marked by developments in castle infrastructure, army, judiciary and diplomacy

Diplomacy comprises spoken or written communication by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.Ronald Peter Barston, ''Modern diplomacy'', Pearson Education, 2006, p. 1 ...

. Under his authority, Poland transformed into a major European power; he instituted Polish rule over Ruthenia in 1340 and imposed quarantine that prevented the spread of Black Death. In 1364, Casimir inaugurated the University of Kraków, one of the oldest institutions of higher learning in Europe. Upon his death in 1370, the Piast dynasty came to an end. He was succeeded by his closest male relative, Louis of Anjou, who ruled Poland, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

and Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

in a personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more State (polity), states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some e ...

. Louis' younger daughter Jadwiga became Poland's first female monarch in 1384.

In 1386, Jadwiga of Poland entered a marriage of convenience with Władysław II Jagiełło, the

In 1386, Jadwiga of Poland entered a marriage of convenience with Władysław II Jagiełło, the Grand Duke of Lithuania

The monarchy of Lithuania concerned the monarchical head of state of Kingdom of Lithuania, Lithuania, which was established as an Absolute monarchy, absolute and hereditary monarchy. Throughout Lithuania's history there were three Duke, ducal D ...

, thus forming the Jagiellonian dynasty

The Jagiellonian dynasty (, pl, dynastia jagiellońska), otherwise the Jagiellon dynasty ( pl, dynastia Jagiellonów), the House of Jagiellon ( pl, Dom Jagiellonów), or simply the Jagiellons ( pl, Jagiellonowie), was the name assumed by a cad ...

and the Polish–Lithuanian union which spanned the late Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

and early Modern Era

The term modern period or modern era (sometimes also called modern history or modern times) is the period of history that succeeds the Middle Ages (which ended approximately 1500 AD). This terminology is a historical periodization that is appli ...

. The partnership between Poles and Lithuanians brought the vast multi-ethnic Lithuanian

Lithuanian may refer to:

* Lithuanians

* Lithuanian language

* The country of Lithuania

* Grand Duchy of Lithuania

* Culture of Lithuania

* Lithuanian cuisine

* Lithuanian Jews as often called "Lithuanians" (''Lita'im'' or ''Litvaks'') by other Jew ...

territories into Poland's sphere of influence and proved beneficial for its inhabitants, who coexisted in one of the largest European political entities of the time.

In the Baltic Sea region, the struggle of Poland and Lithuania with the Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

continued and culminated at the Battle of Grunwald

The Battle of Grunwald, Battle of Žalgiris or First Battle of Tannenberg was fought on 15 July 1410 during the Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War. The alliance of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, led respe ...

in 1410, where a combined Polish-Lithuanian army inflicted a decisive victory against them. In 1466, after the Thirteen Years' War, king Casimir IV Jagiellon

Casimir IV (in full Casimir IV Andrew Jagiellon; pl, Kazimierz IV Andrzej Jagiellończyk ; Lithuanian: ; 30 November 1427 – 7 June 1492) was Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1440 and King of Poland from 1447, until his death. He was one of the m ...

gave royal consent to the Peace of Thorn, which created the future Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the region of Prussia establish ...

under Polish suzerainty and forced the Prussian rulers to pay tributes. The Jagiellonian dynasty also established dynastic control over the kingdoms of Bohemia (1471 onwards) and Hungary. In the south, Poland confronted the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

and the Crimean Tatars

, flag = Flag of the Crimean Tatar people.svg

, flag_caption = Flag of Crimean Tatars

, image = Love, Peace, Traditions.jpg

, caption = Crimean Tatars in traditional clothing in front of the Khan's Palace ...

, and in the east helped Lithuania to combat Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

.

Poland was developing as a feudal state, with a predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly powerful landed nobility that confined the population to private manorial farmstead known as ''folwarks''. In 1493, John I Albert sanctioned the creation of a bicameral parliament composed of a lower house, the Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

, and an upper house, the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

. The '' Nihil novi'' act adopted by the Polish General Sejm in 1505, transferred most of the legislative power

A legislature is an deliberative assembly, assembly with the authority to make laws for a Polity, political entity such as a Sovereign state, country or city. They are often contrasted with the Executive (government), executive and Judiciary, ...

from the monarch to the parliament, an event which marked the beginning of the period known as Golden Liberty, when the state was ruled by the seemingly free and equal Polish nobles.

The 16th century saw

The 16th century saw Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

movements making deep inroads into Polish Christianity, which resulted in the establishment of policies promoting religious tolerance, unique in Europe at that time. This tolerance allowed the country to avoid the religious turmoil and wars of religion that beset Europe. In Poland, Nontrinitarian Christianity became the doctrine of the so-called Polish Brethren, who separated from their Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

denomination and became the co-founders of global Unitarianism

Unitarianism (from Latin ''unitas'' "unity, oneness", from ''unus'' "one") is a nontrinitarian branch of Christian theology. Most other branches of Christianity and the major Churches accept the doctrine of the Trinity which states that there ...

.

The European Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

evoked under Sigismund I the Old

Sigismund I the Old ( pl, Zygmunt I Stary, lt, Žygimantas II Senasis; 1 January 1467 – 1 April 1548) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1506 until his death in 1548. Sigismund I was a member of the Jagiellonian dynasty, the ...

and Sigismund II Augustus

Sigismund II Augustus ( pl, Zygmunt II August, lt, Žygimantas Augustas; 1 August 1520 – 7 July 1572) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, the son of Sigismund I the Old, whom Sigismund II succeeded in 1548. He was the first rule ...

a sense of urgency in the need to promote a cultural awakening. During the Polish Golden Age, the nation's economy and culture flourished. The Italian-born Bona Sforza, daughter of the Duke of Milan and queen consort to Sigismund I, made considerable contributions to architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

, cuisine, language and court customs at Wawel Castle.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ...

, a unified federal state with an elective monarchy

An elective monarchy is a monarchy ruled by an elected monarch, in contrast to a hereditary monarchy in which the office is automatically passed down as a family inheritance. The manner of election, the nature of candidate qualifications, and t ...

, but largely governed by the nobility. The latter coincided with a period of prosperity; the Polish-dominated union thereafter becoming a leading power and a major cultural entity, exercising political control over parts of Central, Eastern, Southeastern and Northern Europe. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth occupied approximately at its peak and was the largest state in Europe. Simultaneously, Poland imposed Polonisation policies in newly acquired territories which were met with resistance from ethnic and religious minorities.

In 1573, Henry de Valois of France, the first elected king, approbated the Henrician Articles

The Henrician Articles or King Henry's Articles ( Polish: ''Artykuły henrykowskie'', Latin: ''Articuli Henriciani'') were a permanent contract between the "Polish nation" (the szlachta, or nobility, of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) and a ...

which obliged future monarchs to respect the rights of nobles. When he left Poland to become King of France

France was ruled by Monarch, monarchs from the establishment of the West Francia, Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Cl ...

, his successor, Stephen Báthory

Stephen Báthory ( hu, Báthory István; pl, Stefan Batory; ; 27 September 1533 – 12 December 1586) was Voivode of Transylvania (1571–1576), Prince of Transylvania (1576–1586), King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania (1576–1 ...

, led a successful campaign

Campaign or The Campaign may refer to:

Types of campaigns

* Campaign, in agriculture, the period during which sugar beets are harvested and processed

* Advertising campaign, a series of advertisement messages that share a single idea and theme

* B ...

in the Livonian War

The Livonian War (1558–1583) was the Russian invasion of Old Livonia, and the prolonged series of military conflicts that followed, in which Tsar Ivan the Terrible of Russia (Muscovy) unsuccessfully fought for control of the region (pre ...

, granting Poland more lands across the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. State affairs were then headed by Jan Zamoyski, the Crown Chancellor. Stephen’s successor, Sigismund III, defeated a rival Habsburg electoral candidate, Archduke Maximilian III

Maximilian III of Austria, briefly known as Maximilian of Poland during his claim for the throne (12 October 1558 – 2 November 1618), was the Archduke of Further Austria from 1612 until his death.

Biography

Born in Wiener Neustadt, Maximilia ...

, in the War of the Polish Succession (1587–1588). In 1592, Sigismund succeeded his father and John Vasa, in Sweden. The Polish-Swedish union endured until 1599, when he was deposed by the Swedes.

In 1609, Sigismund invaded

In 1609, Sigismund invaded Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

which was engulfed in a civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

, and a year later the Polish winged hussar units under Stanisław Żółkiewski occupied Moscow for two years after defeating the Russians at Klushino. Sigismund also countered the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in the southeast; at Khotyn in 1621 Jan Karol Chodkiewicz achieved a decisive victory against the Turks, which ushered the downfall of Sultan Osman II.

Sigismund's long reign in Poland coincided with the Silver Age. The liberal Władysław IV effectively defended Poland's territorial possessions but after his death the vast Commonwealth began declining from internal disorder and constant warfare. In 1648, the Polish hegemony over Ukraine sparked the Khmelnytsky Uprising, followed by the decimating Swedish Deluge during the Second Northern War

The Second Northern War (1655–60), (also First or Little Northern War) was fought between Sweden and its adversaries the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1655–60), the Tsardom of Russia ( 1656–58), Brandenburg-Prussia (1657–60), th ...

, and Prussia's independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the s ...

in 1657. In 1683, John III Sobieski re-established military prowess when he halted the advance of an Ottoman Army into Europe at the Battle of Vienna

The Battle of Vienna; pl, odsiecz wiedeńska, lit=Relief of Vienna or ''bitwa pod Wiedniem''; ota, Beç Ḳalʿası Muḥāṣarası, lit=siege of Beç; tr, İkinci Viyana Kuşatması, lit=second siege of Vienna took place at Kahlenberg Mo ...

. The Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country ( Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the No ...

era, under Augustus II and Augustus III, saw neighboring powers grow in strength at the expense of Poland. Both Saxon kings faced opposition from Stanisław Leszczyński during the Great Northern War

The Great Northern War (1700–1721) was a conflict in which a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in Northern, Central and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the anti-Swed ...

(1700) and the War of the Polish Succession (1733).

Partitions

royal election

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a ...

of 1764 resulted in the elevation of Stanisław II Augustus Poniatowski to the monarchy. His candidacy was extensively funded by his sponsor and former lover, Empress Catherine II of Russia

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anha ...

. The new king maneuvered between his desire to implement necessary modernising reforms, and the necessity to remain at peace with surrounding states. His ideals led to the formation of the 1768 Bar Confederation

The Bar Confederation ( pl, Konfederacja barska; 1768–1772) was an association of Polish nobles ( szlachta) formed at the fortress of Bar in Podolia (now part of Ukraine) in 1768 to defend the internal and external independence of the Polis ...

, a rebellion directed against the Poniatowski and all external influence, which ineptly aimed to preserve Poland's sovereignty and privileges held by the nobility. The failed attempts at government restructuring as well as the domestic turmoil provoked its neighbours to intervene.

In 1772, the First Partition of the Commonwealth by Prussia, Russia and Austria took place; an act which the Partition Sejm, under considerable duress, eventually ratified as a fait accompli

Many words in the English vocabulary are of French origin, most coming from the Anglo-Norman spoken by the upper classes in England for several hundred years after the Norman Conquest, before the language settled into what became Modern Engl ...

. Disregarding the territorial losses, in 1773 a plan of critical reforms was established, in which the Commission of National Education, the first government education authority in Europe, was inaugurated. Corporal punishment of schoolchildren was officially prohibited in 1783. Poniatowski was the head figure of the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

, encouraged the development of industries, and embraced republican neoclassicism. For his contributions to the arts and sciences he was awarded a Fellowship of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemati ...

.

In 1791, Great Sejm parliament adopted the 3 May Constitution

The Constitution of 3 May 1791,; lt, Gegužės trečiosios konstitucija titled the Governance Act, was a constitution adopted by the Great Sejm ("Four-Year Sejm", meeting in 1788–1792) for the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a dual mo ...

, the first set of supreme national laws, and introduced a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies di ...

. The Targowica Confederation, an organisation of nobles and deputies opposing the act, appealed to Catherine and caused the 1792 Polish–Russian War. Fearing the reemergence of Polish hegemony, Russia and Prussia arranged and in 1793 executed, the Second Partition, which left the country deprived of territory and incapable of independent existence. On 24 October 1795, the Commonwealth was partitioned for the third time and ceased to exist as a territorial entity. Stanisław Augustus, the last King of Poland, abdicated the throne on 25 November 1795.

Era of insurrections

The Polish people rose several times against the partitioners and occupying armies. An unsuccessful attempt at defending Poland's sovereignty took place in the 1794 Kościuszko Uprising, where a popular and distinguished general Tadeusz Kościuszko, who had several years earlier served under George Washington in the

The Polish people rose several times against the partitioners and occupying armies. An unsuccessful attempt at defending Poland's sovereignty took place in the 1794 Kościuszko Uprising, where a popular and distinguished general Tadeusz Kościuszko, who had several years earlier served under George Washington in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of ...

, led Polish insurgents. Despite the victory at the Battle of Racławice, his ultimate defeat ended Poland's independent existence for 123 years.

In 1806, an insurrection organised by Jan Henryk Dąbrowski liberated western Poland ahead of Napoleon's advance into Prussia during the War of the Fourth Coalition

The Fourth Coalition fought against Napoleon's French Empire and were defeated in a war spanning 1806–1807. The main coalition partners were Prussia and Russia with Saxony, Sweden, and Great Britain also contributing. Excluding Prussia, ...

. In accordance with the 1807 Treaty of Tilsit

The Treaties of Tilsit were two agreements signed by French Emperor Napoleon in the town of Tilsit in July 1807 in the aftermath of his victory at Friedland. The first was signed on 7 July, between Napoleon and Russian Emperor Alexander, wh ...

, Napoleon proclaimed the Duchy of Warsaw, a client state

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite sta ...

ruled by his ally Frederick Augustus I of Saxony. The Poles actively aided French troops in the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, particularly those under Józef Poniatowski

Prince Józef Antoni Poniatowski (; 7 May 1763 – 19 October 1813) was a Polish general, minister of war and army chief, who became a Marshal of the French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars.

A nephew of king Stanislaus Augustus of Poland (), P ...

who became Marshal of France

Marshal of France (french: Maréchal de France, plural ') is a French military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to generals for exceptional achievements. The title has been awarded since 1185, though briefly abolished ( ...

shortly before his death at Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

in 1813. In the aftermath of Napoleon's exile, the Duchy of Warsaw was abolished at the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

in 1815 and its territory was divided into Russian Congress Kingdom of Poland, the Prussian Grand Duchy of Posen

The Grand Duchy of Posen (german: Großherzogtum Posen; pl, Wielkie Księstwo Poznańskie) was part of the Kingdom of Prussia, created from territories annexed by Prussia after the Partitions of Poland, and formally established following th ...

, and Austrian Galicia with the Free City of Kraków.

In 1830, non-commissioned officer

A non-commissioned officer (NCO) is a military officer who has not pursued a commission. Non-commissioned officers usually earn their position of authority by promotion through the enlisted ranks. (Non-officers, which includes most or all enli ...

s at Warsaw's Officer Cadet School rebelled in what was the November Uprising. After its collapse, Congress Poland lost its constitutional autonomy, army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

and legislative assembly. During the European Spring of Nations, Poles took up arms in the Greater Poland Uprising of 1848 to resist Germanisation, but its failure saw duchy's status reduced to a mere province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outsi ...

; and subsequent integration into the German Empire in 1871. In Russia, the fall of the January Uprising

The January Uprising ( pl, powstanie styczniowe; lt, 1863 metų sukilimas; ua, Січневе повстання; russian: Польское восстание; ) was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at ...

(1863–1864) prompted severe political, social and cultural reprisals, followed by deportations and pogroms of the Polish-Jewish population. Towards the end of the 19th century, Congress Poland became heavily industrialised; its primary exports being coal, zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodic t ...

, iron and textiles.

Second Polish Republic

In the aftermath of

In the aftermath of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, the Allies agreed on the reconstitution of Poland, confirmed through the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

of June 1919. A total of 2 million Polish troops fought with the armies of the three occupying powers, and over 450,000 died. Following the armistice with Germany

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistic ...

in November 1918, Poland regained its independence as the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

.

The Second Polish Republic reaffirmed its sovereignty after a series of military conflicts, most notably the Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (Polish–Bolshevik War, Polish–Soviet War, Polish–Russian War 1919–1921)

* russian: Советско-польская война (''Sovetsko-polskaya voyna'', Soviet-Polish War), Польский фронт (' ...

, when Poland inflicted a crushing defeat on the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

at the Battle of Warsaw.

The inter-war period heralded a new era of Polish politics. Whilst Polish political activists had faced heavy censorship in the decades up until World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, a new political tradition was established in the country. Many exiled Polish activists, such as Ignacy Jan Paderewski, who would later become prime minister, returned home. A significant number of them then went on to take key positions in the newly formed political and governmental structures. Tragedy struck in 1922 when Gabriel Narutowicz, inaugural holder of the presidency, was assassinated at the Zachęta Gallery in Warsaw by a painter and right-wing nationalist Eligiusz Niewiadomski

Eligiusz Niewiadomski (December 1, 1869 in Warsaw – January 31, 1923 in Warsaw) was a Polish modernist painter and art critic who sympathized with the right-wing National Democracy movement. In 1922 he assassinated Poland's first Presiden ...

.

In 1926, the May Coup, led by the hero of the Polish independence campaign Marshal Józef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Naczelnik państwa, Chief of State (1918–1922) and Marshal of Poland, First Marshal of Second Polish Republic, Poland (from 1920). He was ...

, turned rule of the Second Polish Republic over to the nonpartisan Sanacja (''Healing'') movement to prevent radical political organisations on both the left and the right from destabilizing the country. By the late 1930s, due to increased threats posed by political extremism inside the country, the Polish government became increasingly heavy-handed, banning a number of radical organisations, including communist and ultra-nationalist political parties, which threatened the stability of the country.

World War II

World War II began with the Nazi German

World War II began with the Nazi German invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

on 1 September 1939, followed by the Soviet invasion of Poland

The Soviet invasion of Poland was a military operation by the Soviet Union without a formal declaration of war. On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east, 16 days after Nazi Germany invaded Poland from the west. Subs ...

on 17 September. On 28 September 1939, Warsaw fell. As agreed in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

, Poland was split into two zones, one occupied by Nazi Germany, the other by the Soviet Union. In 1939–1941, the Soviets deported hundreds of thousands of Poles. The Soviet NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

executed thousands of Polish prisoners of war (among other incidents in the Katyn massacre) ahead of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

. German planners had in November 1939 called for "the complete destruction of all Poles" and their fate as outlined in the genocidal ''Generalplan Ost

The ''Generalplan Ost'' (; en, Master Plan for the East), abbreviated GPO, was the Nazi German government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broa ...

''.

Poland made the fourth-largest troop contribution in Europe, and its troops served both the Polish Government in Exile in the west

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

and Soviet leadership in the east. Polish troops played an important role in the Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

, Italian, North African Campaigns and Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

and are particularly remembered for the Battle of Britain and Battle of Monte Cassino. Polish intelligence operatives proved extremely valuable to the Allies, providing much of the intelligence from Europe and beyond, Polish code breakers were responsible for cracking the Enigma cipher and Polish scientists participating in the Manhattan Project were co-creators of the American atomic bomb. In the east, the Soviet-backed Polish 1st Army

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

distinguished itself in the battles for Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is official ...

and Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

.

The wartime resistance movement, and the Armia Krajowa (''Home Army''), fought against German occupation. It was one of the three largest resistance movements of the entire war, and encompassed a range of clandestine activities, which functioned as an underground state complete with degree-awarding universities and a court system. The resistance was loyal to the exiled government and generally resented the idea of a communist Poland; for this reason, in the summer of 1944 it initiated Operation Tempest

file:Akcja_burza_1944.png, 210px, right

Operation Tempest ( pl, akcja „Burza”, sometimes referred to in English as "Operation Storm") was a series of uprisings conducted during World War II against occupying German forces by the Polish Home ...

, of which the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising ( pl, powstanie warszawskie; german: Warschauer Aufstand) was a major World War II operation by the Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from German occupation. It occurred in the summer of 1944, and it was led ...

that began on 1 August 1944 is the best-known operation.

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

set up six German extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

s in occupied Poland, including Treblinka, Majdanek and Auschwitz. The Germans transported millions of Jews from across occupied Europe to be murdered in those camps. Altogether, 3 million Polish Jews – approximately 90% of Poland's pre-war Jewry – and between 1.8 and 2.8 million ethnic Poles were killed during the German occupation of Poland

Occupation commonly refers to:

* Occupation (human activity), or job, one's role in society, often a regular activity performed for payment

*Occupation (protest), political demonstration by holding public or symbolic spaces

*Military occupation, t ...

, including between 50,000 and 100,000 members of the Polish intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

– academics, doctors, lawyers, nobility and priesthood. During the Warsaw Uprising alone, over 150,000 Polish civilians were killed, most were murdered by the Germans during the Wola and Ochota massacres. Around 150,000 Polish civilians were killed by Soviets between 1939 and 1941 during the Soviet Union's occupation of eastern Poland (Kresy

Eastern Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Wschodnie) or simply Borderlands ( pl, Kresy, ) was a term coined for the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic during the History of Poland (1918–1939), interwar period (1918–1939). Largely agricultural ...

), and another estimated 100,000 Poles were murdered by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) between 1943 and 1944 in what became known as the Wołyń Massacres. Of all the countries in the war, Poland lost the highest percentage of its citizens: around 6 million perished – more than one-sixth of Poland's pre-war population – half of them Polish Jews. About 90% of deaths were non-military in nature.

In 1945, Poland's borders were shifted westwards. Over two million Polish inhabitants of Kresy

Eastern Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Wschodnie) or simply Borderlands ( pl, Kresy, ) was a term coined for the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic during the History of Poland (1918–1939), interwar period (1918–1939). Largely agricultural ...

were expelled along the Curzon Line by Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

. The western border became the Oder-Neisse line. As a result, Poland's territory was reduced by 20%, or . The shift forced the migration of millions of other people, most of whom were Poles, Germans, Ukrainians, and Jews.

Post-war communism

At the insistence ofJoseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

, the Yalta Conference sanctioned the formation of a new provisional pro-Communist coalition government in Moscow, which ignored the Polish government-in-exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile ( pl, Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Pola ...

based in London. This action angered many Poles who considered it a betrayal by the Allies. In 1944, Stalin had made guarantees to Churchill and Roosevelt that he would maintain Poland's sovereignty and allow democratic elections to take place. However, upon achieving victory in 1945, the elections organised by the occupying Soviet authorities were falsified and were used to provide a veneer of legitimacy for Soviet hegemony over Polish affairs. The Soviet Union instituted a new communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

government in Poland, analogous to much of the rest of the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

. As elsewhere in Communist Europe, the Soviet influence over Poland was met with armed resistance from the outset which continued into the 1950s.

Despite widespread objections, the new Polish government accepted the Soviet annexation of the pre-war eastern regions of Poland (in particular the cities of Wilno and Lwów) and agreed to the permanent garrisoning of Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

units on Poland's territory. Military alignment within the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

throughout the Cold War came about as a direct result of this change in Poland's political culture. In the European scene, it came to characterise the full-fledged integration of Poland into the brotherhood of communist nations.

The new communist government took control with the adoption of the Small Constitution on 19 February 1947. The Polish People's Republic

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million nea ...

(''Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa'') was officially proclaimed in 1952. In 1956, after the death of Bolesław Bierut, the régime of Władysław Gomułka

Władysław Gomułka (; 6 February 1905 – 1 September 1982) was a Polish communist politician. He was the ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized ...

became temporarily more liberal, freeing many people from prison and expanding some personal freedoms. Collectivisation in the Polish People's Republic failed. A similar situation repeated itself in the 1970s under Edward Gierek, but most of the time persecution of anti-communist opposition groups persisted. Despite this, Poland was at the time considered to be one of the least oppressive states of the Eastern Bloc.

Labour turmoil in 1980 led to the formation of the independent trade union "Solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dicti ...

" ("''Solidarność''"), which over time became a political force. Despite persecution and imposition of martial law in 1981 by General Wojciech Jaruzelski, it eroded the dominance of the Polish United Workers' Party and by 1989 had triumphed in Poland's first partially free and democratic parliamentary elections since the end of the Second World War. Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa (; ; born 29 September 1943) is a Polish statesman, dissident, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, who served as the President of Poland between 1990 and 1995. After winning the 1990 election, Wałęsa became the first democrat ...

, a Solidarity candidate, eventually won the presidency in 1990. The Solidarity movement heralded the collapse of communist regimes and parties across Europe.

Third Polish Republic

A shock therapy program, initiated by Leszek Balcerowicz in the early 1990s, enabled the country to transform its Soviet-style

A shock therapy program, initiated by Leszek Balcerowicz in the early 1990s, enabled the country to transform its Soviet-style planned economy

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, p ...

into a market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand, where all suppliers and consumers ar ...

. As with other post-communist countries, Poland suffered temporary declines in social, economic, and living standards, but it became the first post-communist country to reach its pre-1989 GDP levels as early as 1995, although the unemployment rate increased. Poland became a member of the Visegrád Group

The Visegrád Group (also known as the Visegrád Four, the V4, or the European Quartet) is a cultural and political alliance of four Central European countries: the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia. The alliance aims to advance co-op ...

in 1991, and joined NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

in 1999. Poles then voted to join the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been ...

in a referendum in June 2003, with Poland becoming a full member on 1 May 2004, following the consequent enlargement of the organisation.

Poland joined the Schengen Area

The Schengen Area ( , ) is an area comprising 27 European countries that have officially abolished all passport and all other types of border control at their mutual borders. Being an element within the wider area of freedom, security and ...

in 2007, as a result of which, the country's borders with other member states of the European Union were dismantled, allowing for full freedom of movement within most of the European Union. On 10 April 2010, the President of Poland

The president of Poland ( pl, Prezydent RP), officially the president of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Prezydent Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej), is the head of state of Poland. Their rights and obligations are determined in the Constitution of Polan ...

Lech Kaczyński, along with 89 other high-ranking Polish officials died in a plane crash near Smolensk

Smolensk ( rus, Смоленск, p=smɐˈlʲensk, a=smolensk_ru.ogg) is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow. First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest ...

, Russia.

In 2011, the ruling Civic Platform won parliamentary elections

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ...

. In 2014, the Prime Minister of Poland

The President of the Council of Ministers ( pl, Prezes Rady Ministrów, lit=Chairman of the Council of Ministers), colloquially referred to as the prime minister (), is the head of the cabinet and the head of government of Poland. The responsibi ...

, Donald Tusk, was chosen to be President of the European Council

The president of the European Council is the person presiding over and driving forward the work of the European Council on the world stage. This institution comprises the college of heads of state or government of EU member states as well as ...

, and resigned as prime minister. The 2015 and 2019 elections

The following elections were scheduled to occur in 2019. The International Foundation for Electoral Systems has a calendar of upcoming elections around the world, and the National Democratic Institute also maintains a calendar of elections in coun ...

were won by the national-conservative Law and Justice

Law and Justice ( pl, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość , PiS) is a right-wing populist and national-conservative political party in Poland. Its chairman is Jarosław Kaczyński.

It was founded in 2001 by Jarosław and Lech Kaczyński as a direct ...

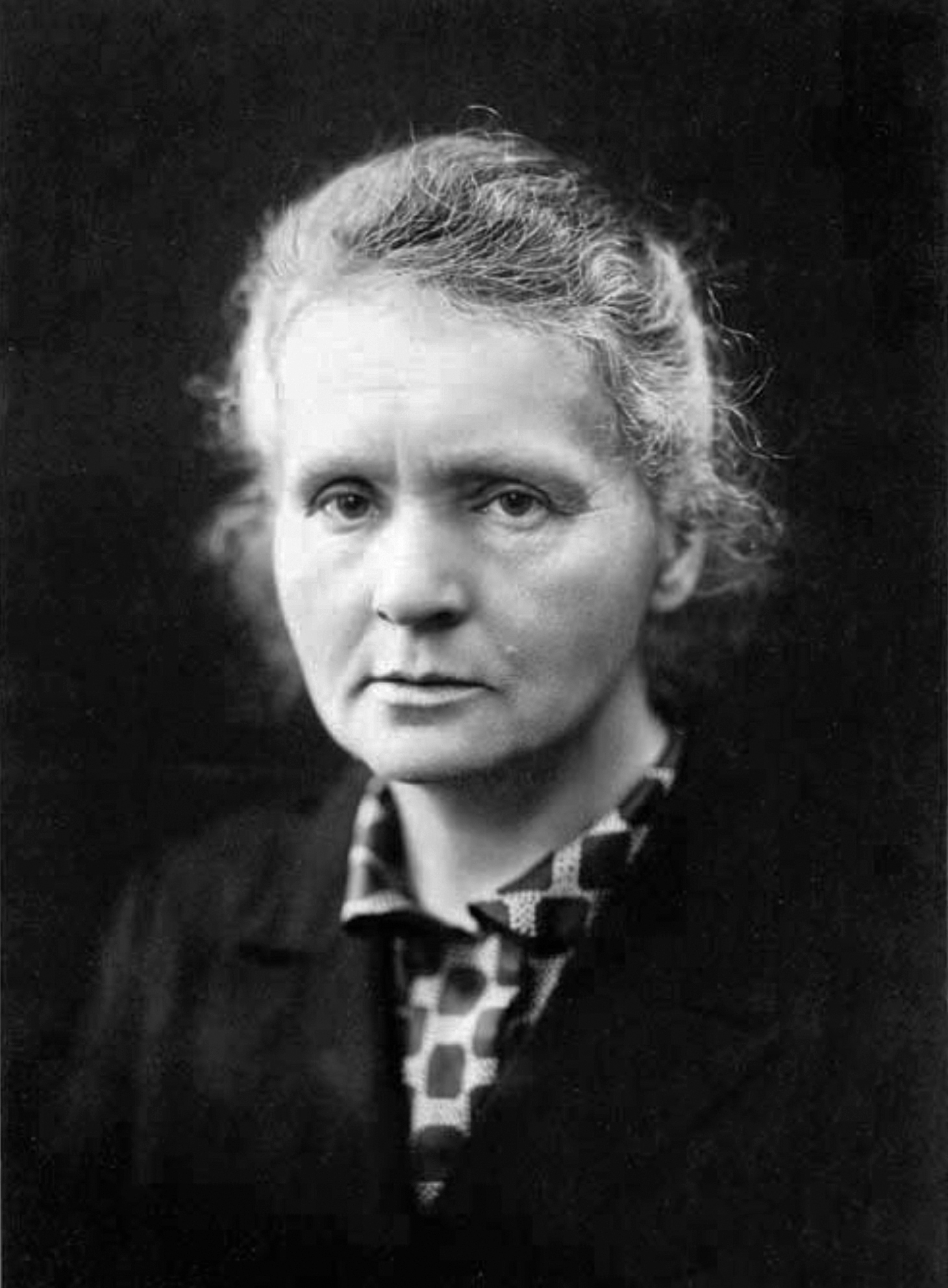

Party (PiS) led by Jarosław Kaczyński, resulting in increased Euroscepticism