Poena Cullei on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Poena cullei'' (from

''Poena cullei'' (from

''Poena cullei'' (from

''Poena cullei'' (from Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

'penalty of the sack') under Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the ''Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor J ...

was a type of death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

imposed on a subject who had been found guilty of patricide

Patricide is (i) the act of killing one's own father, or (ii) a person who kills their own father or stepfather. The word ''patricide'' derives from the Greek word ''pater'' (father) and the Latin suffix ''-cida'' (cutter or killer). Patricide ...

. The punishment consisted of being sewn up in a leather sack, with an assortment of live animals including a dog, snake, monkey, and a chicken or rooster, and then being thrown into water.

The punishment may have varied widely in its frequency and precise form during the Roman period

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

. For example, the earliest fully documented case is from ca. 100 BC, although scholars think the punishment may have developed about a century earlier. Inclusion of live animals in the sack is only documented from Early Imperial times, and at the beginning, only snakes were mentioned. At the time of Emperor Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania B ...

(2nd century AD), the most well known form of the punishment was documented, where a cock, a dog, a monkey and a viper

The Viperidae (vipers) are a family of snakes found in most parts of the world, except for Antarctica, Australia, Hawaii, Madagascar, and various other isolated islands. They are venomous and have long (relative to non-vipers), hinged fangs tha ...

were inserted in the sack. At the time of Hadrian ''poena cullei'' was made into an optional form of punishment for parricides (the alternative was being thrown to the beasts in the arena).

During the 3rd century AD up to the accession of Emperor Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

, ''poena cullei'' fell out of use; Constantine revived it, now with only serpents to be added in the sack. Well over 200 years later, Emperor Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

reinstituted the punishment with the four animals, and ''poena cullei'' remained the statutory penalty for patricides within Byzantine law

Byzantine law was essentially a continuation of Roman law with increased Orthodox Christian and Hellenistic influence. Most sources define ''Byzantine law'' as the Roman legal traditions starting after the reign of Justinian I in the 6th century ...

for the next 400 years, when it was replaced with being burned alive

''Burned Alive: A Victim of the Law of Men'' is a best-selling book, ostensibly a first-person account of an attempted honor killing. The author, Souad, is described as a Palestinian woman now living in Europe who survived an attempted murder ...

. ''Poena cullei'' gained a revival of sorts in late medieval and early modern Germany, with late cases of being drowned in a sack along with live animals being documented from Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

in the first half of the 18th century.

Execution ritual

The 19th-century historianTheodor Mommsen

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (; 30 November 1817 – 1 November 1903) was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th cent ...

compiled and described in detail the various elements that at one time or another have been asserted as elements within the ritualistic execution of a parricide during the Roman Era, and while the following paragraph is based on that description it is ''not'' to be regarded as a static ritual that always was observed, but as a descriptive enumeration of elements gleaned from several sources written over a period of several centuries. Mommsen, for example, notes that the monkey hardly can have been an ancient element in the execution ritual.

Other variations occur, and some of the Latin phrases have been interpreted differently. For example, in his early work ''De Inventione

''De Inventione'' is a handbook for orators that Cicero composed when he was still a young man. Quintilian tells us that Cicero considered the work rendered obsolete by his later writings. Originally four books in all, only two have survived into ...

'', Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

says the criminal's mouth was covered by a leather bag, rather than a wolf's hide. He also says the person was held in prison until the large sack was made ready, whereas at least one modern author believes the sack, ''culleus'', involved, would have been one of the large, very common sacks Romans transported wine in, so that such a sack would have been readily available. According to the same author, such a wine sack had a volume of .

Another point of contention concerns precisely how, and by what means, the individual was beaten. In his 1920 essay "''The Lex Pompeia and the Poena Cullei''", Max Radin observes that, as expiation

Propitiation is the act of appeasing or making well-disposed a deity, thus incurring divine favor or avoiding divine retribution. While some use the term interchangeably with expiation, others draw a sharp distinction between the two. The discuss ...

, convicts were typically flogged until they bled (some commentators translate the phrase as "beaten with rods till he bleeds"), but that it might very well be the case that the rods themselves were painted red. Radin also points to a third option, namely that the "rods" actually were some type of shrub

A shrub (often also called a bush) is a small-to-medium-sized perennial woody plant. Unlike herbaceous plants, shrubs have persistent woody stems above the ground. Shrubs can be either deciduous or evergreen. They are distinguished from trees ...

, since it documented from other sources that whipping with some kinds of shrub was thought to be purifying in nature.

Publicius Malleolus

The picture gained of the ritual above is compiled from sources ranging in their generally agreed upon dates of composition from the 1st century BC, to the 6th century AD, that is, over a period of six to seven hundred years. Different elements are mentioned in the various sources, so that the ''actual'' execution ritual at any one particular time may have been substantially distinct from that ritual performed at other times. For example, the '' Rhetoricia ad Herennium'', a treatise by an unknown author from about 90 BC details the execution of a Publicius Malleolus, found guilty of murdering his own mother, along with citing the relevant law as follows: As can be seen from the above, in this early reference, ''no'' mention is made of live animals as co-inhabitants within the sack, nor is the mention of any initial whipping contained, nor that Malleolus, contained within the sack, was transported to the river in a cart driven by black oxen. The Roman historianLivy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Ancient Rome, Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditiona ...

places the execution of Malleolus to just about 10 years earlier than the composition of ''Rhetoricia ad Herennium'' (i.e., roughly 100 BC) and claims, furthermore, that Malleolus was the first in Roman history who was convicted to be sewn into a sack and thrown into the water, on account of parricide.

Possible antecedents

The historiansDionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus ( grc, Διονύσιος Ἀλεξάνδρου Ἁλικαρνασσεύς,

; – after 7 BC) was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary sty ...

and Valerius Maximus

Valerius Maximus () was a 1st-century Latin writer and author of a collection of historical anecdotes: ''Factorum ac dictorum memorabilium libri IX'' ("Nine books of memorable deeds and sayings", also known as ''De factis dictisque memorabilibus'' ...

, connect the practice of ''poena cullei'' with an alleged incident under king Tarquinius Superbus

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (died 495 BC) was the legendary seventh and final king of Rome, reigning 25 years until the popular uprising that led to the establishment of the Roman Republic.Livy, ''ab urbe condita libri'', I He is commonly known a ...

(legendary reign being 535–509 BC). During his reign, the Roman state apparently acquired the so-called Sibylline Books

The ''Sibylline Books'' ( la, Libri Sibyllini) were a collection of oracular utterances, set out in Greek hexameters, that, according to tradition, were purchased from a sibyl by the last king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus, and were consulted at mo ...

, books of prophecy and sacred rituals. The king appointed a couple of priests, the so-called '' duumviri sacrorum'', to guard the books, but one of them, Marcus Atilius, was bribed, and in consequence, divulged some of the book's secrets (to a certain Sabine

The Sabines (; lat, Sabini; it, Sabini, all exonyms) were an Italic people who lived in the central Apennine Mountains of the ancient Italian Peninsula, also inhabiting Latium north of the Anio before the founding of Rome.

The Sabines divide ...

foreigner Petronius, according to Valerius). For that breach of religion, Tarquinius had him sewn up in a sack and thrown into the sea. According to Valerius Maximus, it was very long after this event that this punishment was instituted for the crime of parricide as well, whereas Dionysius says that in addition to being suspected of divulging the secret texts, Atilius was, indeed, accused of having killed his own father.

The Greek historian Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

, however, in his "Life of Romulus

Romulus () was the legendary foundation of Rome, founder and King of Rome, first king of Ancient Rome, Rome. Various traditions attribute the establishment of many of Rome's oldest legal, political, religious, and social institutions to Romulus ...

" claims that the first case in Roman history of a son killing his own father happened more than five centuries after the foundation of Rome (traditional foundation date 753 BC), when a man called Lucius Hostius murdered his own father after the wars with Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Puni ...

, that is, after the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

(which ended in 201 BC). Plutarch, however, does not specify ''how'' Lucius Hostius was executed, or even if he was executed by the Roman state at all. Additionally, he notes that at the time of Romulus and for the first centuries onwards, "parricide" was regarded as roughly synonymous with what is now called homicide

Homicide occurs when a person kills another person. A homicide requires only a volitional act or omission that causes the death of another, and thus a homicide may result from accidental, reckless, or negligent acts even if there is no inten ...

, and that prior to the times of Lucius Hostius, the murder of one's own ''father'', (i.e., patricide

Patricide is (i) the act of killing one's own father, or (ii) a person who kills their own father or stepfather. The word ''patricide'' derives from the Greek word ''pater'' (father) and the Latin suffix ''-cida'' (cutter or killer). Patricide ...

), was simply morally "unthinkable".

According to Cloud and other modern scholars of Roman classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, a fundamental shift in the punishment of murderers may have occurred towards the end of the 3rd century BC, possibly spurred on by specific incidents like that of Lucius Hostius' murder of his father, and, more generally, occasioned by the concomitant brutalization of society in the wake of the protracted wars with Hannibal. Previously, murderers would have been handed over to the family of the victim to exact their vengeance, whereas from the 2nd century BC and onwards, the punishment of murderers became the affair of the Roman state, rather than giving the offended family full licence to mete out what ''they'' deemed appropriate punishment to the murderer of a relative. Within that particular context, Cloud points out that certain jokes contained in the plays of the early 2nd century dramatist Plautus

Titus Maccius Plautus (; c. 254 – 184 BC), commonly known as Plautus, was a Roman playwright of the Old Latin period. His comedies are the earliest Latin literary works to have survived in their entirety. He wrote Palliata comoedia, the gen ...

may be read as referring to the recent introduction of the punishment by the sack for parricides specifically (without the animals being involved).

Yet another incident prior to the execution of Malleolus is relevant. Some 30 years before the times of Malleolus, in the upheavals and riotings caused by the reform program urged on by Tiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus ( 163 – 133 BC) was a Roman politician best known for his agrarian law, agrarian reform law entailing the transfer of land from the Roman state and wealthy landowners to poorer citizens. He had also serve ...

, a man called Caius Villius, an ally of Gracchus, was condemned on some charge, and was shut up in a vessel or jar, to which serpents were added, and he was killed in that manner.

First-century BC legislation

Two laws documented from the first century BC are principally relevant to Roman murder legislation in general, and legislation on parricide in particular. These are the ''Lex Cornelia De Sicariis'', promulgated in the 80s BC, and the ''Lex Pompeia de Parricidiis'' promulgated about 55 BC. According to a 19th-century commentator, the relation between these two old laws might have been that it was the ''Lex Pompeia'' that specified the ''poena cullei'' (i.e., sewing the convict up in a sack and throwing him in the water) as the particular punishment for a ''parricide'', because a direct reference to the ''Lex Cornelia'' shows that the typical punishment for a poisoner or assassin in general (rather than for the specific crime of parricide) was that of banishment, i.e., ''Lex Pompeia'' makes explicit distinctions for the crime of parricide not present in ''Lex Cornelia. Support for a possible distinction in the inferred contents of ''Lex Cornelia'' and ''Lex Pompeia'' from the remaining primary source material may be found in comments by the 3rd-century AD jurist Aelius Marcianus, as preserved in the 6th-century collection of juristical sayings, the '' Digest: Modern experts continue to have some disagreements as to the actual meaning of the offence called "parricide", on the ''precise'' relation between the ''Lex Cornelia'' and the ''Lex Pompeia'' generally, and on the practice and form of the ''poena cullei'' specifically. For example, Kyle (2012) summarizes, in a footnote, one of the contemporary relevant controversies in the following manner:Writings of Marcus Tullius Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

, the renowned lawyer, orator and politician from the 1st century BC, provides in his copious writings several references to the punishment of ''poena cullei'', but none of the live animals documented within the writings by others from later periods. In his defence speech of 80 BC for Sextus Roscius

Sextus Roscius (often referred to as ''Sextus Roscius the Younger'' to differentiate him from his father) was a Roman citizen farmer from Ameria (modern day Amelia) during the latter days of the Roman Republic. In 80 BC, he was tried in Rome for p ...

(accused of having murdered his own father), he expounds on the ''symbolic'' importance of the punishment as follows, for example, as Cicero believed it was devised and designed by the previous Roman generations:

That the practice of sewing murderers of their parents in sacks and throwing them in the water was still an active type of punishment at Cicero's time, at least on the ''provincial'' level, is made clear within a preserved letter Marcus wrote to his own brother Quintus

Quintus is a male given name derived from '' Quintus'', a common Latin forename (''praenomen'') found in the culture of ancient Rome. Quintus derives from Latin word ''quintus'', meaning "fifth".

Quintus is an English masculine given name and ...

, who as governor in Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

in the 50s BC had, in fact, meted out that precise punishment to two locals in Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

, as Marcus observes.

Julio-Claudian Dynasty, the two Senecas and Juvenal

In whatever form or frequency the punishment of the sack was actually practiced in late Republican Rome or early Imperial Rome, the historianSuetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (), commonly referred to as Suetonius ( ; c. AD 69 – after AD 122), was a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial era of the Roman Empire.

His most important surviving work is a set of biographies ...

, in his biography of Octavian, that is Emperor Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

(r.27 BC–14 AD), notes the following reluctance on the emperor's part to actively authorize, and effect, that dread penalty:

Quite the opposite mentality seems to have been the case with Emperor Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusu ...

(r.41 – 54 AD) For example, Emperor Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 un ...

's mentor, Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (; 65 AD), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and, in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca was born in ...

sighed about the times of Claudius as follows:

It is also with a writer like Seneca that serpents are mentioned in context with the punishment;. Even before Seneca the Younger, his father, Seneca the Elder

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Elder (; c. 54 BC – c. 39 AD), also known as Seneca the Rhetorician, was a Roman writer, born of a wealthy equestrian family of Corduba, Hispania. He wrote a collection of reminiscences about the Roman schools of rheto ...

, who lived in the reigns of Augustus, Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

and Caligula

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the popular Roman general Germanicu ...

, indicates in a comment that snakes would be put in the ''culleus'':

The rather later satirist Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ), was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century CE. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the ''Satires''. The details of Juvenal's life ...

(born, probably, in the 50s AD) also provides evidence for the ''monkey'', he even pities the monkey, at one point, as an innocent sufferer. Not so with how Emperor Nero was reviled. In one play, Juvenal suggests that for Nero, being put in merely one sack is not good enough. This might, for example, be a reference both to the death of Nero's mother Agrippina Minor

Julia Agrippina (6 November AD 15 – 23 March AD 59), also referred to as Agrippina the Younger, was Roman empress from 49 to 54 AD, the fourth wife and niece of Emperor Claudius.

Agrippina was one of the most prominent women in the Julio-Cla ...

, widely believed to have been murdered on Nero's orders, and also to how Nero murdered his fatherland. Not only Juvenal thought the sack was the standard by which the appropriate punishment for Nero should be measured; the statues of Nero were despoiled and vandalized, and according to the Roman historian Suetonius, one statue was draped in a sack given a placard that said "I have done what I could. But you deserve the sack!".

Emperor Hadrian and later jurists

It is within the law collection '' Digest'' 48.9.9 that perhaps the most famous formulation of the ''poena cullei'' is retained, from the sayings of the mid-3rd-century CE jurist Modestinus. In Olivia Robinsons translation, it reads: Thus, it is seen in the time of EmperorHadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania B ...

(r.117–138 CE), the punishment for parricide was basically made ''optional'', in that the convict might be thrown into the arena instead. Furthermore, a rescript from Hadrian is preserved in the 4th-century CE grammarian Dositheus Magister Dositheus Magister ( grc, Δωσίθεος) was a Greek grammarian who flourished in Rome in the 4th century AD.

Life

He was the author of a Greek translation of a Latin grammar, intended to assist the Greek-speaking inhabitants of the empire in le ...

that contains the information that the cart with the sack and its live contents was driven by black oxen.

In the time of the late 3rd-century CE jurist Paulus, he said that the ''poena cullei'' had fallen out of use, and that parricides were either burnt alive or thrown to the beasts instead.

However, although Paulus regards the punishment of ''poena cullei'' as obsolete in his day, the church father Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian ...

, in his "Martyrs of Palestine" notes a case of a Christian man Ulpianus in Tyre who was "cruelly scourged" and then placed in a raw ox-hide, together with a dog and a venomous serpent and cast in the sea. The incident is said to have taken place in 304 CE.

Revival by Constantine the Great

On account of Paulus' comment, several scholars think the punishment of ''poena cullei'' fell out of use in the 3rd century CE, but the punishment was revived, and made broader (by including fathers who killed their children as liable to the punishment) by Emperor Constantine in a rescript from 318 CE. This rescript was retained in the 6th-centuryCodex Justinianus

The Code of Justinian ( la, Codex Justinianus, or ) is one part of the ''Corpus Juris Civilis'', the codification of Roman law ordered early in the 6th century AD by Justinian I, who was Eastern Roman emperor in Constantinople. Two other units, t ...

and reads as follows:

Legislation of Justinian

The ''Corpus Juris Civilis

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Byzantine Emperor. It is also sometimes referred ...

'', the name for the massive body of law promulgated by Emperor Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

from the 530s AD and onwards, consists of two historical collections of laws and their interpretation (the ''Digest'', opinions of the pre-eminent lawyers from the past, and the ''Codex Justinianus'', a collection of edicts and rescripts by earlier emperors), along with Justinian's prefatory introduction text for students of Law, Institutes

An institute is an organisational body created for a certain purpose. They are often research organisations (research institutes) created to do research on specific topics, or can also be a professional body.

In some countries, institutes can ...

, plus the Novels

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itself ...

, Justinian's own, later edicts. That the earlier collections were meant to be sources for the ''actual, current practice of law'', rather than just being of historical interest, can be seen, for example, from the inclusion, and modification of Modestinus' famous description of ''poena cullei'' (Digest 48.9.9), in Justinian's own law text in Institutes 4.18.6.

It is seen that Justinian regards this as a ''novel'' enactment of an old law, and that he includes not only the symbolic interpretations of the punishment as found in for example Cicero, but also Constantine's extension of the penalty to fathers who murder their own children. In Justinian, relative to Constantine, we see the inclusion in the sack of the dog, cock and monkey, not just the serpent(s) in Constantine. Some modern historians, such as O.F. Robinson, suspects that the precise wording of the text in the ''Institutes'' 4.18.6 suggests that the claimed reference in ''Digest'' 48.9.9 from Modestinus is actually a sixth AD ''interpolation'' into the 3rd-century AD law text, rather than being a faithful citation of Modestinus.

Abolition

The ''poena cullei'' was eliminated as the punishment for parricides within theByzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

in the law code Basilika

The ''Basilika'' was a collection of laws completed c. 892 AD in Constantinople by order of the Eastern Roman emperor Leo VI the Wise during the Macedonian dynasty. This was a continuation of the efforts of his father, Basil I, to simplify and ...

, promulgated more than 300 years after the times of Justinian, around 892 AD. As Margaret Trenchard-Smith notes, however, in her essay "Insanity, Exculpation and Disempowerment", that "this does not necessarily denote a softening of attitude. According to the ''Synopsis Basilicorum'' (an abridged edition of ''Basilika''), parricides are to be cast into the flames."

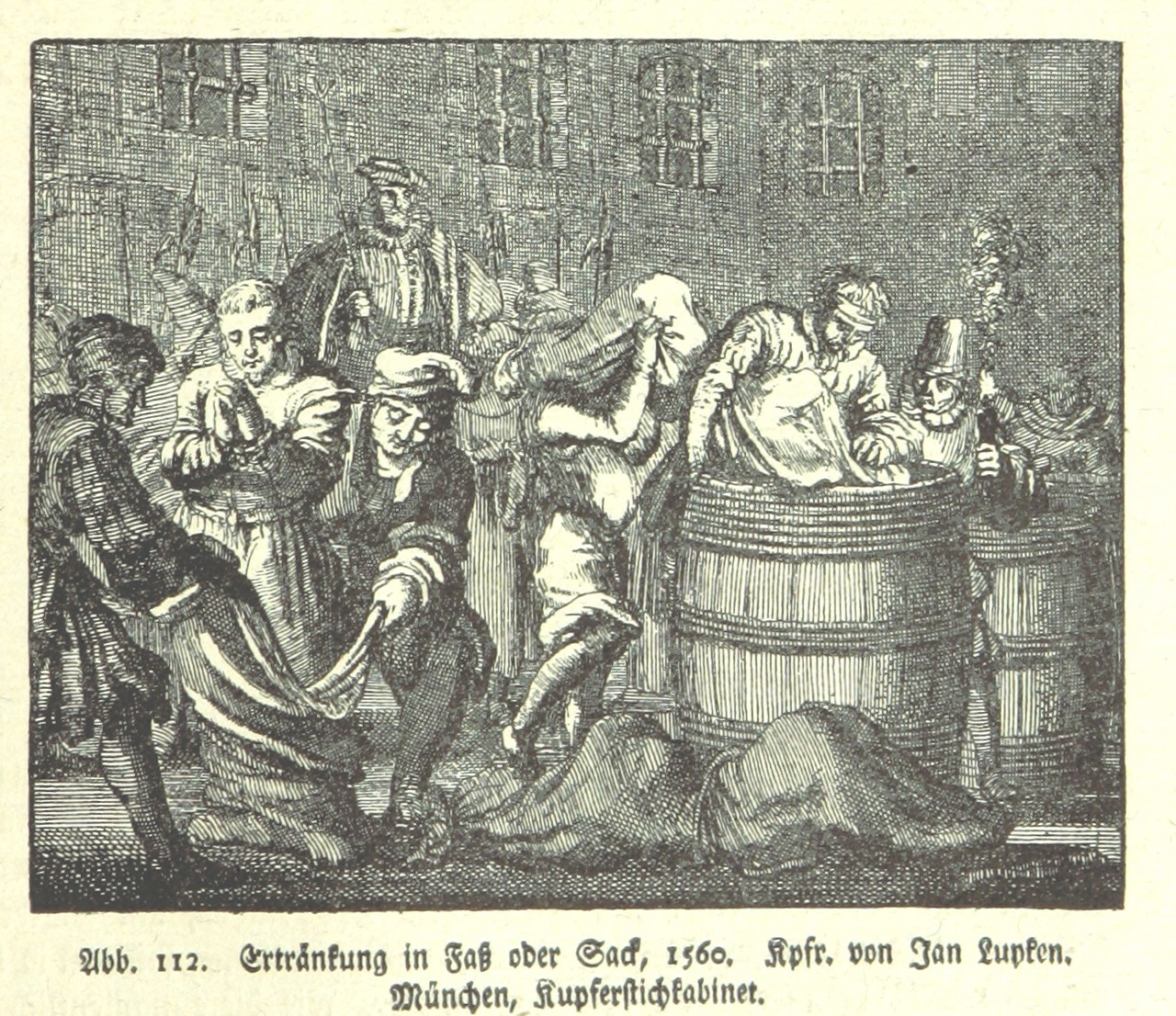

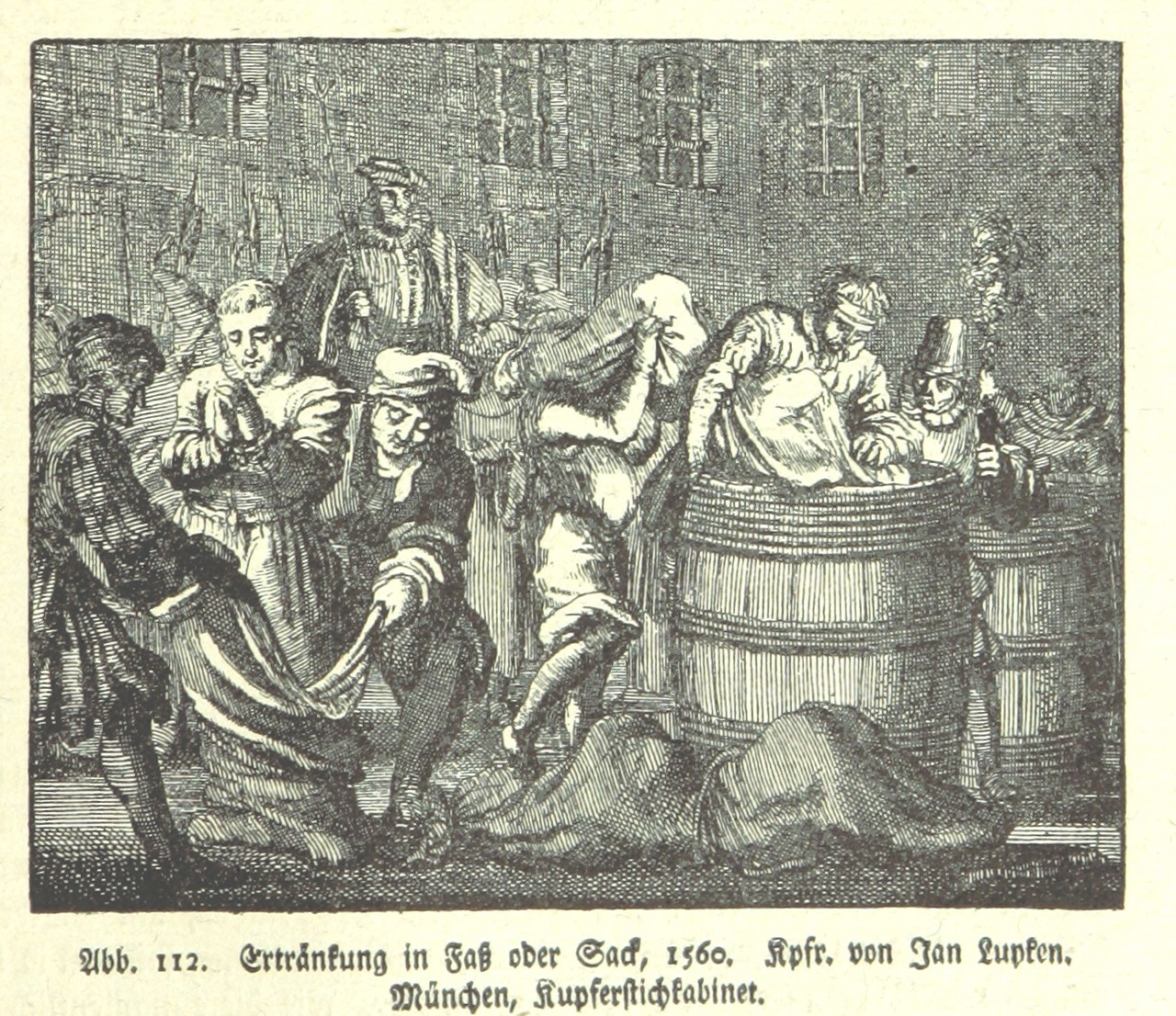

German revival in the Middle Ages and beyond

The penalty of the sack, alongside the animals included, experienced a revival in parts of late medieval, and early modern Germany (particularly inSaxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

). The 14th-century commentator on the 13th-century compilation of laws/customs Sachsenspiegel

The (; gml, Sassen Speyghel; modern nds, Sassenspegel; all literally "Saxon Mirror") is one of the most important law books and custumals compiled during the Holy Roman Empire. Originating between 1220 and 1235 as a record of existing loc ...

, Johann von Buch, for example, states that the ''poena cullei'' is the appropriate punishment for parricides. Some differences evolved within the German ritual, relative to the original Roman ritual, though. Apparently, the rooster was not included, and the serpent might be replaced with a painting of a serpent on a piece of paper and the monkey could be replaced with a cat. Furthermore, the cat and the dog were sometimes physically separated from the person, and the sack itself (with its two partitions) was made of linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong, absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. It also ...

, rather than of leather.

The difference between using ''linen'', rather than ''leather'' is that linen soaks easily, and the inhabitants will drown, whereas a ''watertight'' leather sack will effect death by suffocation due to lack of air (or death by a drawn-out drowning process, relative to a comparatively quick one), rather than death by drowning. In a 1548 case from Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label=Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth larg ...

, the intention was to suffocate the culprit (who had killed his mother), rather than drown him. With him into the leather sack was a cat and a dog, and the sack was made airtight by coating it with pitch. However, the sack chosen was too small, and had been overstretched, so as the sack hit the waters after being thrown from the bridge, it ripped open. The cat and the dog managed to swim away and survive, while the criminal (presumably bound) "got his punishment rather earlier than had been the intention", that is, death by drowning instead.

The last case where this punishment is, by some, alleged to have been meted out in 1734, somewhere in Saxony. Another tradition, however, is evidenced from the Saxonian city Zittau

Zittau ( hsb, Žitawa, dsb, Žytawa, pl, Żytawa, cs, Žitava, :de:Oberlausitzer Mundart, Upper Lusatian Dialect: ''Sitte''; from Slavic languages, Slavic "''rye''" (Upper Sorbian and Czech: ''žito'', Lower Sorbian: ''žyto'', Polish: ''żyto' ...

, where the last case is alleged to have happened in 1749. In at least one case in Zittau 1712, a non-venomous colubrid

Colubridae (, commonly known as colubrids , from la, coluber, 'snake') is a family of snakes. With 249 genera, it is the largest snake family. The earliest species of the family date back to the Oligocene epoch. Colubrid snakes are found on ever ...

snake was used. The Zittau ritual was to put the victims in a black sack, and keep it under water for no less than six hours. In the meantime, the choir girls in town had the duty to sing the Psalm composed by Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

, "Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir

"" (From deep affliction I cry out to you), originally "", later also "", is a Lutheran hymn of 1524, with words written by Martin Luther as a paraphrase of Psalm 130. It was first published in 1524 as one of eight songs in the first Lutheran ...

" (From deep affliction I cry out to you). The punishment of the sack was expressly abolished in Saxony in a rescript dated 17 June 1761.

From Chinese accounts

The ''Wenxian Tongkao

The ''Wenxian Tongkao'' () or ''Tongkao'' was one of the model works of the '' Tongdian'' compiled by Ma Duanlin in 1317, during the Yuan Dynasty.

References

*Dong, Enlin, et al. (2002). ''Historical Literature and Cultural Studies''. Wuhan: Hube ...

'', written by Chinese historian Ma Duanlin

''Mă Duānlín'' () (1245–1322) was a Chinese historical writer and encyclopaedist. In 1317, during the Yuan Dynasty, he published the comprehensive Chinese encyclopedia ''Wenxian Tongkao'' in 348 volumes.

He was born to the family of Southern ...

(1245-1322), and the '' History of Song'' describe how the Byzantine emperor Michael VII Parapinakēs Caesar (''Mie li sha ling kai sa'' 滅力沙靈改撒) of ''Fu lin'' (拂菻, i.e. Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' cont ...

) sent an embassy to China's Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

, arriving in November 1081, during the reign of Emperor Shenzong of Song

Emperor Shenzong of Song (25 May 1048 – 1 April 1085), personal name Zhao Xu, was the sixth emperor of the Song dynasty of China. His original personal name was Zhao Zhongzhen but he changed it to "Zhao Xu" after his coronation. He reigned fr ...

(r. 1067-1085). The ''History of Song'' described the tributary gifts given by the Byzantine embassy as well as the products made in Byzantium. It also described forms of punishment in Byzantine law, such as caning, as well as the capital punishment of being stuffed into a "feather bag" and thrown into the sea. This description seems to correspond with the Romano-Byzantine punishment of ''poena cullei''.

Modern fiction

In his (1991) novel ''Roman Blood

''Roman Blood'' is a historical novel by American author Steven Saylor, first published by Minotaur Books in 1991. It is the first book in his Roma Sub Rosa series of mystery novels set in the final decades of the Roman Republic. The main charact ...

'', Steven Saylor

Steven Saylor (born March 23, 1956) is an American author of historical novels. He is a graduate of the University of Texas at Austin, where he studied history and classics.

Saylor's best-known work is his ''Roma Sub Rosa'' historical mystery ...

renders a fictionalized, yet informed, rendition of how the Roman punishment ''poena cullei'' might occur. The reference to the punishment is in connection with Cicero's (historically correct, and successful) endeavours to acquit Sextus Roscius

Sextus Roscius (often referred to as ''Sextus Roscius the Younger'' to differentiate him from his father) was a Roman citizen farmer from Ameria (modern day Amelia) during the latter days of the Roman Republic. In 80 BC, he was tried in Rome for p ...

of the charge of having murdered his own father.

China Miéville

China Tom Miéville ( ; born 6 September 1972) is a British speculative fiction writer and literary critic. He often describes his work as ''weird fiction'' and is allied to the loosely associated movement of writers called '' New Weird''.

Mi ...

's short story "Säcken", collected in '' Three Moments of an Explosion: Stories'', is a modern horror story which incorporates the punishment.

Notes and references

Bibliography

;Books and journals * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ;Web resources * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * *{{cite book, editor-last=Watson, editor-first=Alan , title=The Digest of Justinian, Volumes 1–4, publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press, year=1998, location=Philadelphia, isbn=978-0-8122-2036-0 Capital punishment in ancient Rome Execution methods