Platycercus Icterotis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

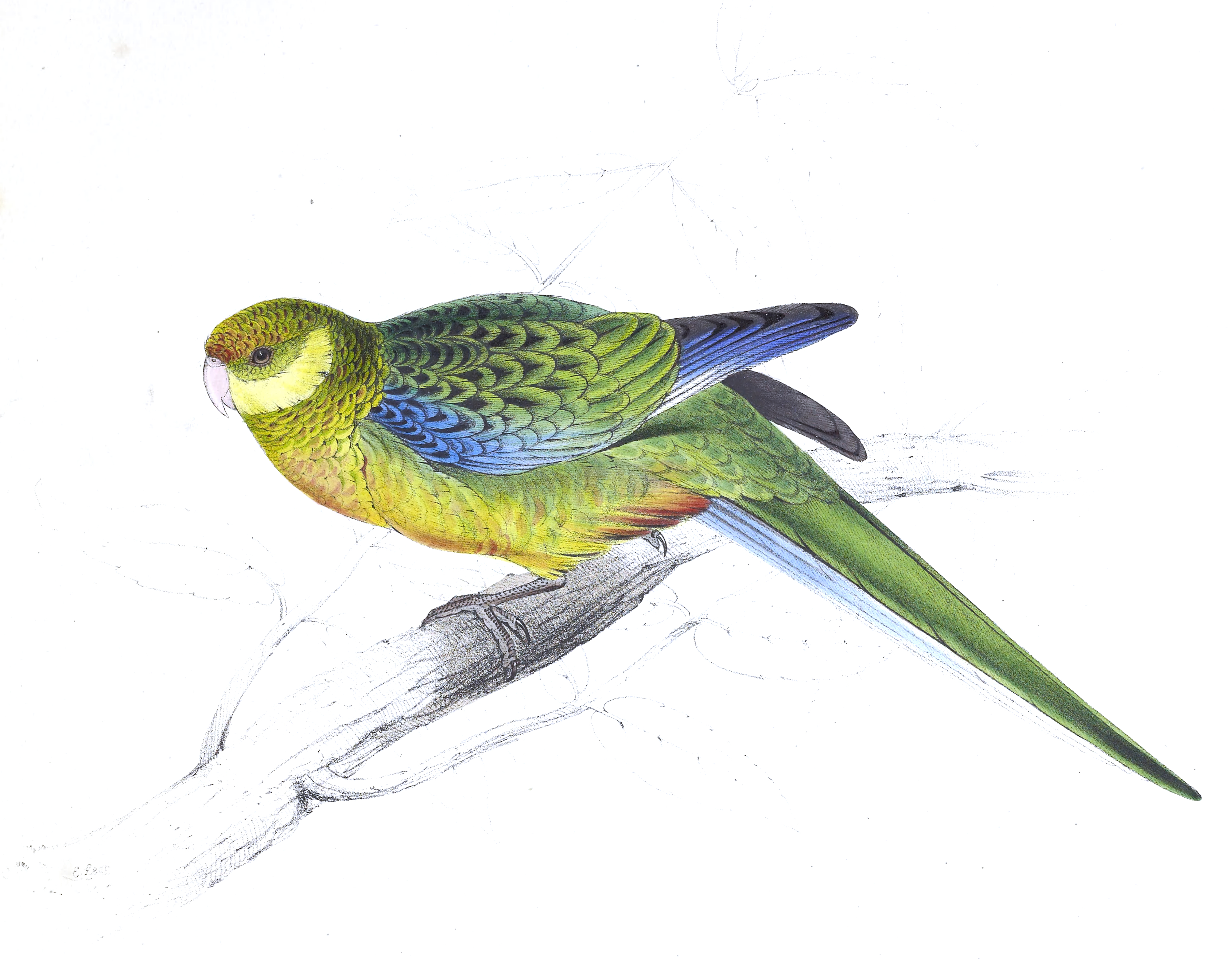

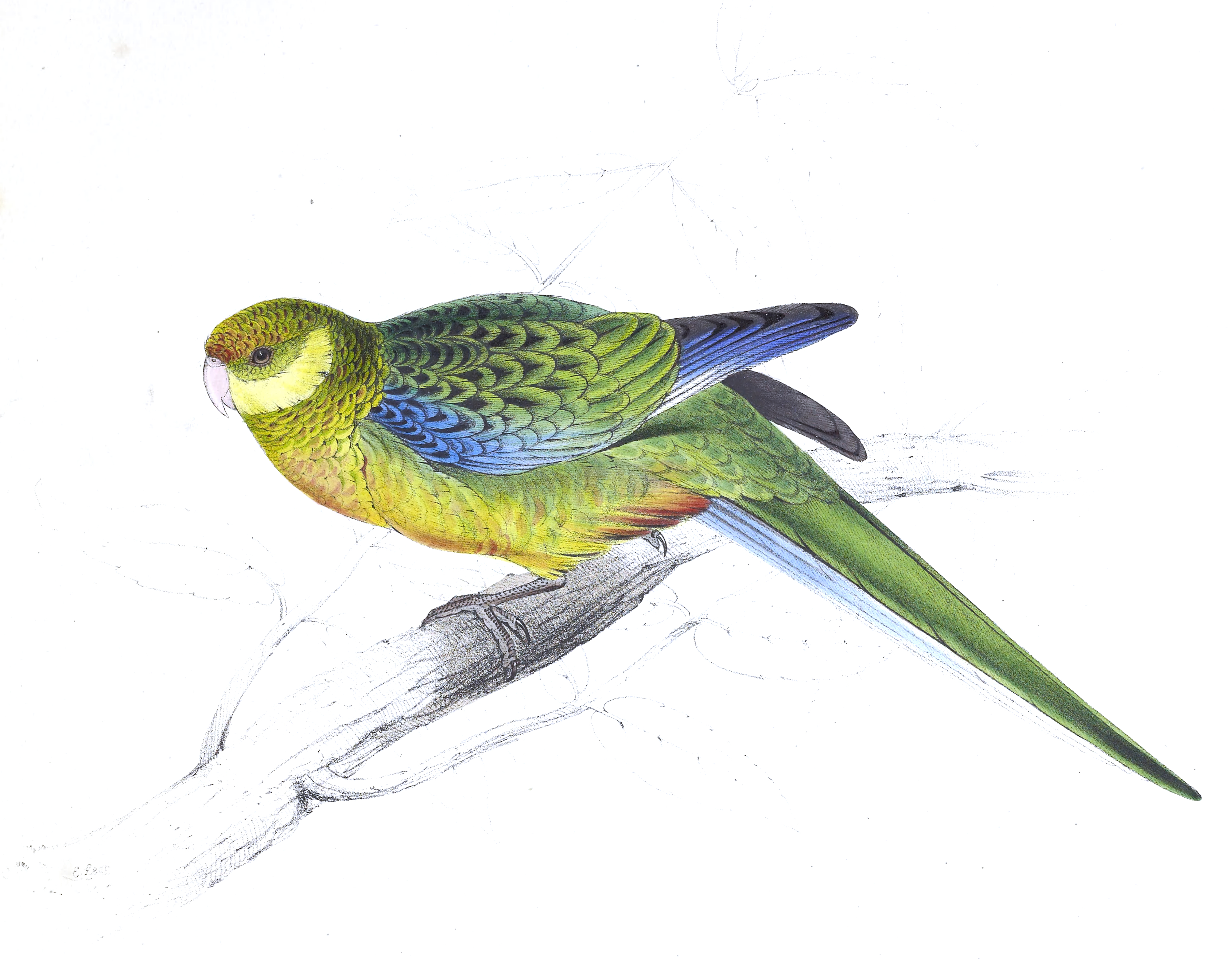

The western rosella (''Platycercus icterotis''), or moyadong, is a species of parrot

Two

Two  Common names for moyadong include western rosella, rosehill, rosella and roselle, vernacular that appears to have elided from an early name for a species observed at

Common names for moyadong include western rosella, rosehill, rosella and roselle, vernacular that appears to have elided from an early name for a species observed at

The regular vocalisation is a rapid series of melodious notes delivered at a low volume.

The vocalisation of sister species of other regions is notably louder and more frequently heard in raucous exchanges with other individuals or species.

The transliterations of the soft and musical sounds include ''ching-ching-ching'' (Morcombe, ''et al''), ''chink-chink'' (Serventy, Simpson) and ''pink-pink'' (Johnstone, ''et al''), although they more often remain quiet and unheard. Gould (1848) reported the whistling of the notes as a feeble, piping sound and the rich variation in the series might be regarded "as almost to assume the character of a song". Other sources identify two vocalisations, a resonant and high frequency ''quink, quink, quink, quink'' and the softer voiced call of ''whip-a-whee''.

The contact call is similar to, although louder than the mulga parrot (''

The regular vocalisation is a rapid series of melodious notes delivered at a low volume.

The vocalisation of sister species of other regions is notably louder and more frequently heard in raucous exchanges with other individuals or species.

The transliterations of the soft and musical sounds include ''ching-ching-ching'' (Morcombe, ''et al''), ''chink-chink'' (Serventy, Simpson) and ''pink-pink'' (Johnstone, ''et al''), although they more often remain quiet and unheard. Gould (1848) reported the whistling of the notes as a feeble, piping sound and the rich variation in the series might be regarded "as almost to assume the character of a song". Other sources identify two vocalisations, a resonant and high frequency ''quink, quink, quink, quink'' and the softer voiced call of ''whip-a-whee''.

The contact call is similar to, although louder than the mulga parrot (''

The two subspecies are geographically adjacent—''P. icterotis xanthogenys'' at the wheatbelt region, inland to the north and east of the range and ''P. icterotis icterotis'' occurring at coastal areas in the south and west. The inland boundary of the species' range extends from the area between the lower part of the Swan River and the Arrowsmith River at the western coast. From there it passes to the east and south before

The two subspecies are geographically adjacent—''P. icterotis xanthogenys'' at the wheatbelt region, inland to the north and east of the range and ''P. icterotis icterotis'' occurring at coastal areas in the south and west. The inland boundary of the species' range extends from the area between the lower part of the Swan River and the Arrowsmith River at the western coast. From there it passes to the east and south before

They exhibit little caution in rural areas, gleaning seeds at paddocks after harvests or inside buildings and

They exhibit little caution in rural areas, gleaning seeds at paddocks after harvests or inside buildings and

Western rosellas are a popular bird in aviaries and for

Western rosellas are a popular bird in aviaries and for

endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

to southwestern Australia

Southwest Australia is a biogeographic region in Western Australia. It includes the Mediterranean-climate area of southwestern Australia, which is home to a diverse and distinctive flora and fauna.

The region is also known as the Southwest Au ...

. The head and underparts are bright red, and the back is mottled black; a yellow patch at the cheek distinguishes it from others of the genus '' Platycercus''. Adults of the species exhibit sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

with the females duller overall; juveniles lack the striking colours of mature birds and the characteristic patterning is not as easily distinguished. Their communication call is a softly delivered ''pink-pink'' sound, and much of their behaviour is comparatively unobtrusive. Their habitat is in eucalypt

Eucalypt is a descriptive name for woody plants with capsule fruiting bodies belonging to seven closely related genera (of the tribe Eucalypteae) found across Australasia:

''Eucalyptus'', '' Corymbia'', '' Angophora'', ''Stockwellia'', ''Allosyn ...

forests and woodlands, where they often remain unobserved until they appear to feed on seeds at nearby cleared areas.

Individuals form mating pairs and generally remain in one locality, although they will venture out to join small groups at plentiful sources of food. The western rosella is predominantly herbivorous, its diet consisting mostly of seeds of grasses and other plants, although nectar and insect larvae are sometimes eaten. The damage attributed to the species at introduced fruit and grain crops saw them declared as a pest and permitted by the state to be killed or captured. They are more placid and sociable than rosellas of other Australian regions from which they are geographically isolated and have become internationally popular as an aviary

An aviary is a large enclosure for confining birds, although bats may also be considered for display. Unlike birdcages, aviaries allow birds a larger living space where they can fly; hence, aviaries are also sometimes known as flight cages. Av ...

bird. Their history in aviculture

Aviculture is the practice of keeping and breeding birds, especially of wild birds in captivity.

Types

There are various reasons that people get involved in aviculture. Some people breed birds to preserve a species. Some people breed parrots a ...

begins with two 1830 lithographs of live specimens in England by Edward Lear

Edward Lear (12 May 1812 – 29 January 1888) was an English artist, illustrator, musician, author and poet, who is known mostly for his literary nonsense in poetry and prose and especially his limerick (poetry), limericks, a form he popularised. ...

. Successful breeding in captivity began there during the early 20th century.

The population is classified as two subspecies, representing an inland group residing in the agricultural district and another nearer the coast in kwongan

Kwongan is plant community found in south-western Western Australia. The name is a Bibbelmun (Noongar) Aboriginal term of wide geographical use defined by Beard (1976) as

Kwongan has replaced other terms applied by European botanists such as ...

, tall forest and a variety of woodlands. The abrupt intersection of these groups' range, delineated by country of lower rainfall between Albany and Geraldton, is a zone of hybridisation between the two subspecies ''Platycercus icterotis icterotis'' and ''P. icterotis xanthogenys''. The classification of the species relationship to sister taxa of ''Platycercus'' is less complex, due to their ecological and geographic isolation, and they are allied to a subgenus ''Platycercus'' (''Violania'') .

Taxonomy

The first description of the species was published by C. J. Temminck andHeinrich Kuhl

Heinrich Kuhl (17 September 1797 – 14 September 1821) was a German people, German naturalist and zoologist.

Kuhl was born in Hanau (Hesse, Germany). Between 1817 and 1820, he was the assistant of professor Th. van Swinderen, docent natural hi ...

in 1820 as ''Psittacus icterotis'', using a collection obtained at King George Sound

King George Sound ( nys , Menang Koort) is a sound on the south coast of Western Australia. Named King George the Third's Sound in 1791, it was referred to as King George's Sound from 1805. The name "King George Sound" gradually came into use ...

(Albany, Western Australia

Albany ( ; nys, Kinjarling) is a port city in the Great Southern region in the Australian state of Western Australia, southeast of Perth, the state capital. The city centre is at the northern edge of Princess Royal Harbour, which is a ...

). Kuhl was once mistakenly given sole authorship for the description; this was later corrected to include Temminck; Kuhl himself cited Temminck's earlier work in the text describing their three specimens. The epithet ''icterotis'', meaning 'yellow ear', is derived from ancient Greek and presumed to refer to the yellow cheek. They were separated from the genus ''Psittacus

''Psittacus'' is a genus of African grey parrots in the subfamily Psittacinae. It contains the two species: the grey parrot (''Psittacus erithacus'') and the Timneh parrot (''Psittacus timneh'').

For many years, the grey parrot and Timneh parr ...

'' in 1830 by Nicholas Vigors

Nicholas Aylward Vigors (1785 – 26 October 1840) was an Irish zoologist and politician. He popularized the classification of birds on the basis of the quinarian system.

Early life

Vigors was born at Old Leighlin, County Carlow on 1785 as fi ...

, to the genus ''Platycercus'' he had erected five years earlier; the specific epithet he nominated was ''Platycercus stanleyii''.

Two

Two subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

are recognised at the ''Australian Faunal Directory

The Australian Faunal Directory (AFD) is an online catalogue of taxonomic and biological information on all animal species known to occur within Australia. It is a program of the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water of th ...

'', the nominate ''Platycercus icterotis icterotis'' and a description of inland specimens as subspecies ''Platycercus icterotis xanthogenys''. The inland subspecies cites Tommaso Salvadori

Count Adelardo Tommaso Salvadori Paleotti (30 September 1835 – 9 October 1923) was an Italian zoologist and ornithologist.

Biography

Salvadori was born in Porto San Giorgio, son of Count Luigi Salvadori and Ethelyn Welby, who was English. His ...

's 1891 description of a new species ''Platycercus xanthogenys'', published in the ''Proceedings'' of the Zoological Society, emerging from his work on a catalogue of psittacine

Psittacinae is a subfamily of Afrotropical or Old World parrots, native to sub-Saharan Africa, which include twelve species and two extant genera. Among the species is the iconic grey parrot.

The ''Poicephalus'' are usually green birds wit ...

specimens at the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

; the latter work contains an illustration of the holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of several ...

by J. G. Keulemans.

A revision in 1955 by Arthur Cain

Arthur James Cain FRS (25 July 1921 – 20 August 1999) was a British evolutionary biologist and ecologist. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1989.

Life

Arthur James Cain was awarded an open scholarship in 1939 (Demyship) to Mag ...

proposed the type locality for ''P. icterotis xanthogenys'' was Wongan Hills

Wongan Hills is a range of low flat-topped hills in the Avon Wheatbelt bioregion of Western Australia. It is located at , in the Shire of Wongan–Ballidu.

History

The range was first recorded in 1836 by Surveyor General of Western Australia Jo ...

, arbitrarily, but accepted as logical in assuming that John Gould

John Gould (; 14 September 1804 – 3 February 1881) was an English ornithologist. He published a number of monographs on birds, illustrated by plates produced by his wife, Elizabeth Gould, and several other artists, including Edward Lear, ...

's field worker, John Gilbert, could have obtained a specimen there and it resembled those found occurring at that location. A revision by Herbert Condon

Herbert Thomas Condon (27 February 1912 – 12 January 1978) was an Australian museum curator and ornithologist. He was born in Melbourne and attended the University of Adelaide. In 1929, Condon joined the scientific staff of the South Australia ...

, published in the ''Checklist of the Birds of Australia'' (RAOU

The Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union (RAOU), now part of BirdLife Australia, was Australia's largest non-government, non-profit, bird conservation organisation. It was founded in 1901 to promote the study and conservation of the native b ...

, 1975), supports a classification of two subspecies:

* ''Platycercus'' (''Violania'') ''icterotis icterotis'' (Temminck & Kuhl, 1820)

** synonyms: ''Psittacus icterotis'' Temminck & Kuhl, 1820 nd Temminck 1821 ''Platycercus stanleyii'' Vigors, 1830; ''Platycercus icterotis salvadori'' Mathews.

* ''Platycercus'' (''Violania'') ''icterotis xanthogenys'' Salvadori, 1891

** synonyms: ''Platycercus xanthogenys'' Salvadori, 1891; ''Platycercus icterotis whitlocki'' Mathews, 1912.

Revision and cataloguing in the 20th century began to examine the classification of the few known specimens, often supplied without location details, and, excepting A. J. North

Alfred John North (11 June 1855 – 6 May 1917) was an Australian ornithologist.

North was born in Melbourne and was educated at Melbourne Grammar School. He was appointed to the Australian Museum, Sydney in 1886 and was given a permanent positi ...

, cited the work of Savadori in 1891. In a review of material in the Tring collection in England, supplemented by Bernard Woodward at the Perth Museum and the collection of field worker J. T. Tunney, the trinomial ''Platycercus icterotis xanthogenys'' was published by Ernst Hartert

Ernst Johann Otto Hartert (29 October 1859 – 11 November 1933) was a widely published German ornithologist.

Life and career

Hartert was born in Hamburg, Germany on 29 October 1859. In July 1891, he married the illustrator Claudia Bernadine E ...

in 1905. The author Gregory Mathews

Gregory Macalister Mathews Order of the British Empire, CBE FRSE FZS FLS (10 September 1876 – 27 March 1949) was an Australian-born amateur ornithologist who spent most of his later life in England.

Life

He was born in Biamble, New South Wal ...

, an avid exponent of subspecific classification, cites the species ''Platycercus xanthogenys'' Salvadori, but disposed of the epithet ''xanthogenys'' when tentatively proposing three new taxa. Mathews notes Salvadori's separation of the type specimen from two others in the Gould collection, then held at the London museum, and caution in only giving the source of the skin as "unknown, but probably Australia". Mathews proposed three subspecies in 1912, each given a brief distinguishing remark to be expanded in a later volume of his series ''Birds of Australia

Australia and its offshore islands and territories have 898 recorded bird species as of 2014. Of the recorded birds, 165 are considered vagrant or accidental visitors, of the remainder over 45% are classified as Australian endemics: found nowhe ...

''.

The entry in that 1917 work addresses the type of nominate ''P. icterotis icterotis'', which he had earlier ascribed to the location "Shark Bay

Shark Bay (Malgana: ''Gathaagudu'', "two waters") is a World Heritage Site in the Gascoyne region of Western Australia. The http://www.environment.gov.au/heritage/places/world/shark-bay area is located approximately north of Perth, on the ...

". This was corrected by Mathews to the location "Albany, South-West Australia". In the preface to the same volume, Mathews attributes the material examined from the southwest of Australia to the collections of the botanist Robert Brown on the Flinders expedition.

The author also corrected his reference to "Point Cloates

Point Cloates (), formerly known as Cloate's Island, is a peninsula approximately 100 kilometres south south-west of North West Cape, in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. It features Point Cloates Lighthouse and the ruins of a previous li ...

", given in his 1912 determination of the unknown source of the type in Salvadori's 1891 description, ''Platycercus xanthogenys''. He put the location beyond York, Western Australia

York is the oldest inland town in Western Australia, situated on the Avon River, east of Perth in the Wheatbelt, on Ballardong Nyoongar land,King, A and Parker, E: York, Western Australia's first inland town, Parker Print, 2003 p.3. and is ...

. This is where John Gilbert was known to have collected when visiting the western colony in the 1830s.

A new taxon ''P. icterotis salvadori'' (yellow-cheeked parrot) differentiates those found at Wilson's Inlet

Wilson Inlet is a shallow, seasonally open estuary located on the coast of the Great Southern region of Western Australia.

Description

The inlet receives water from the two main rivers: the Denmark River and the Hay River and some smaller ...

as "having less red on the mantle", and another, ''P. icterotis whitlocki'' (Dundas yellow-cheeked parrot), as smaller, less blue at the wing, and more subdued red feathers at the head in the specimens obtained from Lake Dundas (Dundas Dundas may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Dundas, New South Wales

* Dundas, Queensland, a locality in the Somerset Region

* Dundas, Tasmania

* Dundas, Western Australia

* Fort Dundas, a settlement in the Northern Territory 1824–1828

* Shire of ...

). The epithet ''whitlocki'' was used by authors in ornithological literature to honour the Western Australian field research of Frederick Lawson Whitlock. The notes of Whitlock and other authors reporting from Western Australia, including Tom Carter and A. W. Milligan, were assembled or quoted by Mathews. Errors introduced to the scant body of knowledge by himself and others were acknowledged. The variation in the colours of the back was proposed to accord with differing habitat or as a characteristic of fully mature plumage. He concluded there were at least two subspecies—approximating the coastal and inland forms—that may prove to be more diverse if a complete series of specimens was examined.

The description of the population as two or three subspecific taxa by Mathews is cited within the species circumscription, his ''P. icterus whitlocki'', along with Salvadori's ''P. xanthogenys'', are noted as synonyms for the inland subspecies.

The platycercine parrots have seen various systematic arrangements to circumscribe the contentious sister taxa of northern and eastern Australia, most of which overlap in range and intergrade

In zoology, intergradation is the way in which two distinct subspecies are connected via areas where populations are found that have the characteristics of both. There are two types of intergradation: primary and secondary intergradation.

Primar ...

. One study resulted in new genera being published by Wells and Wellington in 1992. In their classification, the genus name ''Hesperapsittacus'' was described, and this species was proposed as the type. That revision was subsumed several years later, by Richard Schodde

Richard Schodde, OAM (born 23 September 1936) is an Australian botanist and ornithologist.

Schodde studied at the University of Adelaide, where he received a BSc (Hons) in 1960 and a PhD in 1970. During the 1960s he was a botanist with the C ...

(1997), to subgeneric names; the name ''Hesperapsittacus'' became available for Schodde's subgenus, but he nominated their genus name ''Violania'' instead for the alliance of subgenus ''Platycercus'' (''Violania'') Wells & Wellington, 1992. Consequently, the two genera of Wells and Wellington, ''Violania'' and ''Hesperapsittacus'', became synonymous with the subgeneric name of this species. This arrangement allies the western species to the "''Platycercus eximius-adscitus-venustus''" complex

Complex commonly refers to:

* Complexity, the behaviour of a system whose components interact in multiple ways so possible interactions are difficult to describe

** Complex system, a system composed of many components which may interact with each ...

, which were separated to species by Les Christidis

Leslie Christidis (born 30 May 1959), also simply known as Les Christidis, is an Australian ornithologist. His main research field is the evolution and systematics of birds. He has been director of Southern Cross University National Marine Scienc ...

and Boles in 2008. The validity of the alliances in the subgeneric arrangement, especially of ''Platycercus'' (''Violania''), was tested in 2015, with a multilocus approach to phylogenetic analysis, and proposed a hypothesis that challenges the relationships within the genus.

Common names for moyadong include western rosella, rosehill, rosella and roselle, vernacular that appears to have elided from an early name for a species observed at

Common names for moyadong include western rosella, rosehill, rosella and roselle, vernacular that appears to have elided from an early name for a species observed at Rose Hill, New South Wales

Parramatta () is a suburb and major commercial centre in Greater Western Sydney, located in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It is located approximately west of the Sydney central business district on the banks of the Parramatta Ri ...

, "Rose-Hiller", and translocated with its origin forgotten. The names Stanley rosella and yellow-cheeked rosella or parakeet are historical and trade alternatives. The name Western rosella was formally assigned by the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union

The Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union (RAOU), now part of BirdLife Australia, was Australia's largest non-government, non-profit, bird conservation organisation. It was founded in 1901 to promote the study and bird conservation, conservati ...

(RAOU) (now BirdLife Australia) in 1923 to distinguish the name rosella or 'rose-hiller'. These were retroactively assigned as geographic descriptors of the name 'rosella', an informal name that persisted from the colonial period into the 20th century. Gould also records 'rose-hill' as an informal ('colonial') name for this species and two others existing in the local language. An 1898 report of the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science

The Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science (ANZAAS) is an organisation that was founded in 1888 as the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science to promote science.

It was modelled on the British As ...

listing vernacular for Australian birds proposed "Yellow-cheeked Parrakeet" for this species.

Another early name was The Earl of Derby's Parrakeet, an appellation applied by Gould in 1848 to conserve the honour given to a titled Englishman Edward Smith-Stanley in the epithet used by Vigors, ''stanleyii'', that was displaced by the rule of precedence with the earlier epithet, ''icterotis'', assigned by Kuhl. Gould's explanation of his neologism

A neologism Greek νέο- ''néo''(="new") and λόγος /''lógos'' meaning "speech, utterance"] is a relatively recent or isolated term, word, or phrase that may be in the process of entering common use, but that has not been fully accepted int ...

in naming the 'parrakeet' was inserted with the apology "as bound by justice to the first describer … I feel I shall have the acquiescence of all ornithologists". The caption to the 1830 lithograph

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone (lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German a ...

s in Lear

Lear or Leir may refer to:

Acronyms

* Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios, a Mexican association of revolutionary artists and writers

* Low Energy Ion Ring, an ion pre-accelerator of the Large Hadron Collider at CERN

** Low Energy Antipr ...

's ''Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots

''Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots'' is an 1832 book containing 42 hand-coloured lithographs by Edward Lear. He produced 175 copies for sale to subscribers as a part-publication, which were later bound as a book. Lear star ...

'' also gives "Stanley Parrakeet" for his patron, then known as Lord Stanley, applying the name "''Platycercus stanleyii''" published by Vigors in the same year. Other terms are used to identify two specimens illustrated in Mathews ''Birds of Australia'' (v.6, 1917), distinguished by the descriptors 'red-mantled' and 'yellow-cheeked' parrots. The bird was marketed by dealers in England as a 'small variety' of the commonly kept rosella, ''P. eximius'', and maintained the Earl's appellation. Popular names for the species in aviculture

Aviculture is the practice of keeping and breeding birds, especially of wild birds in captivity.

Types

There are various reasons that people get involved in aviculture. Some people breed birds to preserve a species. Some people breed parrots a ...

include Stanley rosella for the species, and the western rosella for the nominate form, and 'red-backed western' or 'Salvadori' rosella for the inland subspecies, ''P. icterosis xanthogenys'', when recognised as distinct; the latter is noted and named for dark red feathers at the back. "Western Rosella" has been designated as the official name of the species by the International Ornithological Committee

The International Ornithologists' Union, formerly known as the International Ornithological Committee, is a group of about 200 international ornithologists, and is responsible for the International Ornithological Congress and other international ...

(IOC), the same name assigned by the RAOU in 1923.

The pre-existing names, derived from the Nyungar language

Noongar (; also Nyungar ) is an Australian Aboriginal language or dialect continuum, spoken by some members of the Noongar community and others. It is taught actively in Australia, including at schools, universities and through public broadcastin ...

, were recorded as regional and literal variants, representing dialectic shifts and often inconsistent spelling by the transcriber. These were first compiled by the colonial diarist George Fletcher Moore

George Fletcher Moore (10 December 1798 – 30 December 1886) was a prominent early settler in colonial Western Australia, and "one fthe key figures in early Western Australia's ruling elite" (Cameron, 2000). He conducted a number of exploring ...

, supplementing the work of others with his own, and first published in 1842."Guldănguldăn, s.—Platycercus Icterotis; red-brested parrot. " Moore, G. F. ''A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia

''A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia'' is a book by George Fletcher Moore. First published in 1842, it represents one of the earliest attempts to record the languages used by the Abor ...

'', 1842. p. 31 ikisource transcript. The names of Moore and other authors were reviewed and published in Serventy and Whittell ''Birds of Western Australia

This is a list of the wild birds found in Western Australia. The list includes introduced species, common vagrants, recently extinct species, extirpated species, some very rare vagrants (seen once) and species only present in captivity. 629 spec ...

'' (1948, & eds.), those recorded at "Perth", ''Good-un-goodt-un'', ''Guddanang-uddan'' and ''Guldanguldan'', and at "Avon River", ''Moy-a-duk'' and ''Moyadong'', the second location referring to the district at Avon River. A recommended orthography and pronunciation list (Abbott, 2009) of Nyungar avian nomenclature, with broad cultural consultation, has proposed ''moyadong'' oy’a’dawngand ''kootonkooton'' oot’awn’koot’awnbe adopted to complement the systematic nomenclature.

Description

The smallest species of its genus, the adult western rosella weighs and is long. It has broad wings with a wingspan and a long tail that is on average , equally half the measurement of its total length. It is the only species of the genus that exhibits marked differences in the coloration of the genders —the red of the plumage is more scarlet in male ''P. icterotis''. Females are less striking in their colouring, the more subdued red plumage being flecked with green and a smaller dull yellow patch at the cheek. The adult male has a predominantly red head and neck, with a yellow cheek patch—bright yellow in the nominate subspecies and pale cream in subspecies ''xanthogenys''. The red feathers are fringed with black when new. The back has indistinct black feathers mottled with red, green, and buff variation, being scalloped with these colours at the feather's edges. When folded, the wing is green, becoming black with green margins on the shoulder, with a narrow dark blue shoulder patch and blue-edged dark primarycoverts

A covert feather or tectrix on a bird is one of a set of feathers, called coverts (or ''tectrices''), which, as the name implies, cover other feathers. The coverts help to smooth airflow over the wings and tail. Ear coverts

The ear coverts are sm ...

. The blue of the flight feathers and coverts at the underwing is apparent when taking to the air. The upper tail coverts and rump are green tending to olive, perhaps with a red margin. The central tail rectrices

Flight feathers (''Pennae volatus'') are the long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the wings or tail of a bird; those on the wings are called remiges (), singular remex (), while those on the tail ...

are blue and green, outer tail feathers are a similar blue with a white tip. The undertail feathers are blue with white fringes. The underparts are red with green flanks. The beak

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for eating, preening, manipulating objects, killing prey, fighting, probing for food ...

is pale blue-grey with a dark grey cere

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for eating, preening, manipulating objects, killing prey, fighting, probing for food, ...

. The legs and feet are slate grey, and the iris

Iris most often refers to:

*Iris (anatomy), part of the eye

*Iris (mythology), a Greek goddess

* ''Iris'' (plant), a genus of flowering plants

* Iris (color), an ambiguous color term

Iris or IRIS may also refer to:

Arts and media

Fictional ent ...

is dark brown.

In the adult female, most of the red plumage of the head, neck and underparts is replaced by green, bar a solid red band across the forehead. The yellow cheek patch is smaller, and there are no red feathers on the back and scapulars. The female has a broad white or cream bar on the underwing.

Immature birds resemble the adult female though with even more green plumage, red only on the crown, and lacking a yellow cheek patch entirely. The bill and cere are light pink, changing to adult coloration by six months of age.

The population has a cline

Cline may refer to:

Science

* Cline (biology), a measurable gradient in a single trait in a species across its geographical range

* Cline (hydrology), a fluid layer with a property that varies

* Cline (mathematics) or generalised circle, a circl ...

in colour variation from east to west, and variable degrees of hybridisation are reported east of the Darling Range

The Darling Scarp, also referred to as the Darling Range or Darling Ranges, is a low escarpment running north–south to the east of the Swan Coastal Plain and Perth, Western Australia. The escarpment extends generally north of Bindoon, to th ...

and in the southern region and Stirling Range

The Stirling Range or Koikyennuruff is a range of mountains and hills in the Great Southern region of Western Australia, south-east of Perth. It is over wide from west to east, stretching from the highway between Mount Barker and Cranb ...

.

This intergrading between forms is recorded at locations such as Albany.

Southwest Australia is also inhabited by similar, albeit larger, parrots—the red-capped parrot ('' Purpureicephalus spurius''), readily distinguished by its yellow rump, and Port Lincoln ''Barnardius zonarius

The Australian ringneck (''Barnardius zonarius'') is a parrot native to Australia. Except for extreme tropical and highland areas, the species has adapted to all conditions. Treatments of genus ''Barnardius'' have previously recognised two sp ...

'' parrots, which present a blue cheek and black head in contrast to the green, red and yellow of this species.

Vocalisations

The regular vocalisation is a rapid series of melodious notes delivered at a low volume.

The vocalisation of sister species of other regions is notably louder and more frequently heard in raucous exchanges with other individuals or species.

The transliterations of the soft and musical sounds include ''ching-ching-ching'' (Morcombe, ''et al''), ''chink-chink'' (Serventy, Simpson) and ''pink-pink'' (Johnstone, ''et al''), although they more often remain quiet and unheard. Gould (1848) reported the whistling of the notes as a feeble, piping sound and the rich variation in the series might be regarded "as almost to assume the character of a song". Other sources identify two vocalisations, a resonant and high frequency ''quink, quink, quink, quink'' and the softer voiced call of ''whip-a-whee''.

The contact call is similar to, although louder than the mulga parrot (''

The regular vocalisation is a rapid series of melodious notes delivered at a low volume.

The vocalisation of sister species of other regions is notably louder and more frequently heard in raucous exchanges with other individuals or species.

The transliterations of the soft and musical sounds include ''ching-ching-ching'' (Morcombe, ''et al''), ''chink-chink'' (Serventy, Simpson) and ''pink-pink'' (Johnstone, ''et al''), although they more often remain quiet and unheard. Gould (1848) reported the whistling of the notes as a feeble, piping sound and the rich variation in the series might be regarded "as almost to assume the character of a song". Other sources identify two vocalisations, a resonant and high frequency ''quink, quink, quink, quink'' and the softer voiced call of ''whip-a-whee''.

The contact call is similar to, although louder than the mulga parrot (''Psephotellus varius

The mulga parrot (''Psephotellus varius'') is endemic to arid scrublands and lightly timbered grasslands in the interior of southern Australia. The male mulga parrot is multicolored, from which the older common name of many-coloured parrot is der ...

'').

Distribution and habitat

The western rosella isendemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

to the southwest of Australia, isolated from sister species of the north and east of the country. Moderately common, it is usually sedentary, frequenting forest and many other types of wooded country or kwongan

Kwongan is plant community found in south-western Western Australia. The name is a Bibbelmun (Noongar) Aboriginal term of wide geographical use defined by Beard (1976) as

Kwongan has replaced other terms applied by European botanists such as ...

. It also occurs in farmland or at other feeding opportunities, and is most often observed at sites cleared of vegetation. The captive occurrence in Australia and several other continents began before 1830 in England.

The two subspecies are geographically adjacent—''P. icterotis xanthogenys'' at the wheatbelt region, inland to the north and east of the range and ''P. icterotis icterotis'' occurring at coastal areas in the south and west. The inland boundary of the species' range extends from the area between the lower part of the Swan River and the Arrowsmith River at the western coast. From there it passes to the east and south before

The two subspecies are geographically adjacent—''P. icterotis xanthogenys'' at the wheatbelt region, inland to the north and east of the range and ''P. icterotis icterotis'' occurring at coastal areas in the south and west. The inland boundary of the species' range extends from the area between the lower part of the Swan River and the Arrowsmith River at the western coast. From there it passes to the east and south before Southern Cross

Crux () is a constellation of the southern sky that is centred on four bright stars in a cross-shaped asterism commonly known as the Southern Cross. It lies on the southern end of the Milky Way's visible band. The name ''Crux'' is Latin for c ...

, the Fraser Range, Esperance, Stirling Ranges

The Stirling Range or Koikyennuruff is a range of mountains and hills in the Great Southern region of Western Australia, south-east of Perth. It is over wide from west to east, stretching from the highway between Mount Barker and Cranb ...

and Kojonup. The line of demarcation between the inland and coastal subspecies begins east of King George Sound and lies to the northwest via Mount Barker and the Kojonup region toward the Bannister River

Bannister River is a river in the South West region of Western Australia.

The river rises to the east of North Bannister and flows in a southerly direction discharging into the Hotham River near Boddington.

The river was named after Capta ...

.

The species is less common on the Swan Coastal Plain

The Swan Coastal Plain in Western Australia is the geographic feature which contains the Swan River as it travels west to the Indian Ocean. The coastal plain continues well beyond the boundaries of the Swan River and its tributaries, as a geol ...

than in southern areas of the wheatbelt, where it is more frequently observed around Narrogin and Katanning at remnant wandoo woodland, They occur throughout the conservation area at Dryandra Woodland

The Dryandra Woodland National Park is a national park in Western Australia within the shires of Cuballing, Williams and Wandering, about south-east of Perth and north-west of the town of Narrogin. It is a complex of 17 distinct blocks ma ...

. Authors came to express doubts on the status of the subspecies, and compiled observations show no geographical separation.

The historical records of the species indicate it relatively uncommon, although it has been noted more often in southern regions. The northernmost extent of the distribution range is near Moora, with records extending toward the east around Norseman. The population of the species has declined significantly since colonisation, especially the inland ''P. icterotis xenogenys'' after the 1970s. It became locally extinct in shire

Shire is a traditional term for an administrative division of land in Great Britain and some other English-speaking countries such as Australia and New Zealand. It is generally synonymous with county. It was first used in Wessex from the beginn ...

s where it had previously been recorded, these include: Coorow, Dandaragan

Dandaragan is a small town in the Wheatbelt region of Western Australia. The name of Dandaragan was first recorded in 1850 as the name of a nearby gulley and spring or watering hole known as Dandaraga spring. The word is Indigenous Australian ...

, Moora, Dalwallinu, Merredin, Quairading

Quairading is a Western Australian town located in the Wheatbelt region. It is the seat of government for the Shire of Quairading.

History

The town was named for Quairading Spring, derived from a local Aboriginal word recorded in 1872 by s ...

, Serpentine-Jarrahdale and the Shire of Murray

The Shire of Murray is a local government area of Western Australia. It has an area of and is located in the Peel Region about south of the Perth central business district.

The Shire extends across the Peel Inlet and the Swan Coastal Plain ...

. Population declines have also been recorded in the shires of Swan

Swans are birds of the family (biology), family Anatidae within the genus ''Cygnus''. The swans' closest relatives include the goose, geese and ducks. Swans are grouped with the closely related geese in the subfamily Anserinae where they form t ...

, Kalamunda, Northam, York, Armadale-Kelmscott

The City of Armadale is a Local government areas of Western Australia, local government area in the southeastern List of Perth suburbs, suburbs of the Western Australian capital city of Perth, about southeast of Perth's Perth central business ...

, Capel and Dumbleyung. This disappearance at northern and eastern parts of the Wheatbelt is the result of habitat removal, and no shires show an increase in records. The adaptation to introduced agricultural crops has been comparatively limited when contrasted with the range of seeds harvested by ringnecks ''Barnardius zonarius

The Australian ringneck (''Barnardius zonarius'') is a parrot native to Australia. Except for extreme tropical and highland areas, the species has adapted to all conditions. Treatments of genus ''Barnardius'' have previously recognised two sp ...

'' and others species. This is likely to have restricted their success in migration to or re-population of greatly altered landscapes. The suggested movement after breeding toward the coast during the austral summer, from areas in the north of the range, lacked evidence of large-scale seasonal movement in occurrence data,

The distribution of ''P. icterotis icterotis'' is restricted to humid and subhumid regions, an area south of Dandaragan

Dandaragan is a small town in the Wheatbelt region of Western Australia. The name of Dandaragan was first recorded in 1850 as the name of a nearby gulley and spring or watering hole known as Dandaraga spring. The word is Indigenous Australian ...

and lower reaches of the Moore River

Moore River is a river in the Wheatbelt region of Western Australia.

Geography

The headwaters of the Moore River lie in the Perenjori, Carnamah and Dalwallinu Shires. The river then drains southwards through Moora, flows westerly before j ...

, and to the west of: Wannamal

Wannamal is a town in the Wheatbelt region of Western Australia.

The town's name is taken from the nearby Wannamal Lake, a name of Indigenous Australian

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage ...

, Muchea, Mundaring, Jarrahdale, Marrinup, Collie

Collies form a distinctive type of herding dogs, including many related landraces and standardized breeds. The type originated in Scotland and Northern England. Collies are medium-sized, fairly lightly-built dogs, with pointed snouts. Many ...

, Boyup Brook, Hay River (upper), and from the ranges of Porongurups

Porongurup National Park is a national park in the Great Southern region of Western Australia. It covers , and is southeast of Perth and north of Albany.

The park contains the Porongurup Range, which is the relic core of an ancient mount ...

and Green Range. Records for ''P. icterotis xanthogenys'' are from the southern interior of Western Australia, semiarid climatic zones, that formerly included Wongan Hills

Wongan Hills is a range of low flat-topped hills in the Avon Wheatbelt bioregion of Western Australia. It is located at , in the Shire of Wongan–Ballidu.

History

The range was first recorded in 1836 by Surveyor General of Western Australia Jo ...

and occurrences at: Kununoppin

Kununoppin is a small town in the Wheatbelt region of Western Australia. The town is located on the Nungarin–Wyalkatchem Road and in the Shire of Trayning local government area, north east of the state capital, Perth, Western Australia. ...

, Moorine Rock, Parker Range Parker may refer to:

Persons

* Parker (given name)

* Parker (surname)

Places Place names in the United States

*Parker, Arizona

*Parker, Colorado

*Parker, Florida

* Parker, Idaho

* Parker, Kansas

* Parker, Missouri

* Parker, North Carolina

*Parker ...

, Yardina Rock

Yardina Rock is a granite rock formation located approximately north east of Norseman and approximately south east of Kambalda in the Goldfields-Esperance region of Western Australia.

Yardina Soak, a intermittent wetland, is located approxima ...

and Ten Mile Rocks

Ten Mile Rocks are a granite rock formation approximately east of Norseman, Western Australia, Norseman and approximately west of Balladonia, Western Australia, Balladonia in the Goldfields-Esperance region of Western Australia.

The rocks ar ...

. The range extends to the west at: Toodyay, Dale River

The Dale River is a perennial river located in the Wheatbelt region of Western Australia.

Rising on the eastern slopes of the Darling Scarp, the river flow generally east by north, joined by six major tributaries including the Dale River Sout ...

, Mt Saddleback and Kojonup and north of the Stirling Range, Fitzgerald River

The Fitzgerald River is a river in the Great Southern region of Western Australia.

Surveyor General John Septimus Roe named the river during expeditions in the area in 1848 after the governor of Western Australia of the day, Charles Fitzge ...

(lower), Ravensthorpe Ravensthorpe may refer to any of the following places.

England

*Ravensthorpe, Dewsbury in West Yorkshire

**Ravensthorpe railway station, Dewsbury

*Ravensthorpe, Northamptonshire

*Ravensthorpe, Peterborough in Cambridgeshire

*Ravensthorpe, an histor ...

, Frank Hann National Park

Frank Hann National Park is a national park in Western Australia, located east-southeast of the capital, Perth in the Shire of Lake Grace. It was named for Frank Hann, an early explorer of the district. The park contains a wide array of flora, ...

and Red Lake. The occurrence farther north is termed casual, the locations are: Mt Jackson, Karalee

Karalee is a rural residential suburb of Ipswich in the City of Ipswich, Queensland, Australia. In the , Karalee had a population of 4352 people.

Geography

The suburb of Karalee is bordered by Brisbane River to the north and north-east and by ...

and Gnarlbine Rock.

A significant change in abundance was noted at Grass Patch, where it was common in the mid-20th century and reappeared after a fifteen-year absence in later decades. The erroneous locations reported by Mathews, Point Cloates and Shark Bay

Shark Bay (Malgana: ''Gathaagudu'', "two waters") is a World Heritage Site in the Gascoyne region of Western Australia. The http://www.environment.gov.au/heritage/places/world/shark-bay area is located approximately north of Perth, on the ...

, were later admitted to have been incorrect by the author; he also identifies the obvious error in Gould's protologue (1837) in extending the range from King George Sound

King George Sound ( nys , Menang Koort) is a sound on the south coast of Western Australia. Named King George the Third's Sound in 1791, it was referred to as King George's Sound from 1805. The name "King George Sound" gradually came into use ...

to "… New South Wales. etc.". The species was later reported by Gould (1848) as only known at the Swan River Colony

The Swan River Colony, also known as the Swan River Settlement, or just Swan River, was a British colony established in 1829 on the Swan River, in Western Australia. This initial settlement place on the Swan River was soon named Perth, and it ...

, a location where it is now uncommon.

They favour woodland habitat with sheoak (''Allocasuarina

''Allocasuarina'' is a genus of trees in the flowering plant family Casuarinaceae. They are endemic to Australia, occurring primarily in the south. Like the closely related genus ''Casuarina'', they are commonly called sheoaks or she-oaks.

Wi ...

''), wurak (''Eucalyptus salmonophloia

''Eucalyptus salmonophloia'', commonly known as salmon gum, wurak or weerluk or woonert or marrlinja. is a species of small to medium-sized tree that is endemic to Western Australia. It has smooth bark, narrow lance-shaped to curved adult leave ...

'') and wandoo (''Eucalyptus wandoo

''Eucalyptus wandoo'', commonly known as wandoo, dooto, warrnt or wornt, is a small to medium-sized tree that is endemic to the southwest of Western Australia. It has smooth bark, lance-shaped adult leaves, flower buds in groups of nine to sev ...

'', ''et al''), but have sometimes flourished at areas cleared for introduced grain crops in the region's Wheatbelt. They also appear at other cleared areas adjoining bushland, such as roadsides, golf courses and reserves, to harvest grasses or weeds. The subspecies occur in differing types of vegetation, living in communities

A community is a Level of analysis, social unit (a group of living things) with commonality such as place (geography), place, Norm (social), norms, religion, values, Convention (norm), customs, or Identity (social science), identity. Communiti ...

associated with their woody upper-storey plants. The coastal subspecies ''P. icterotis icterotis'' is seen amongst the eucalypts and paperbarks of the high rainfall area from Jurien to Green Range

Green Range is a locality in the Great Southern Region of Western Australia.

Demographics

As of the 2021 Australian census, 62 people resided in Green Range, down from 66 in the . The median

In statistics and probability theory, the median ...

, east of Manypeaks, namely marri (''Corymbia calophylla

''Corymbia calophylla'', commonly known as marri, is a species of flowering plant in the family Myrtaceae and is endemic to the southwest of Western Australia. It is a tree or mallee with rough bark on part or all of the trunk, lance-shaped ad ...

''), karri (''Eucalyptus diversicolor

''Eucalyptus diversicolor'', commonly known as karri, is a species of flowering plant in the family Myrtaceae and is endemic to the south-west of Western Australia. It is a tall tree with smooth light grey to cream-coloured, often mottled bark ...

''), moitch ('' E. rudis'') and the paperbark (''Melaleuca

''Melaleuca'' () is a genus of nearly 300 species of plants in the myrtle family, Myrtaceae, commonly known as paperbarks, honey-myrtles or tea-trees (although the last name is also applied to species of '' Leptospermum''). They range in size ...

''). They are known to feed on the fruit of '' Bossiaea linophylla'' and ''Leucopogon obovatus

''Leucopogon obovatus'' is a species of flowering plant in the heath family Ericaceae and is endemic to the southwest of Western Australia. It is an erect shrub with hairy young branchlets, variably-shaped, simple leaves, and erect clusters of 3 ...

'', the flowers of marris and fleshy part of the seed of ''Macrozamia riedlei

''Macrozamia riedlei'', commonly known as a zamia or zamia palm, is a species of cycad in the plant family Zamiaceae. It is endemic to southwest Australia and often occurs in jarrah forests. It may only attain a height of half a metre or form an ...

''. The subspecies feeds both on the ground and in trees.

The wooded scrub of the lower rainfall inland region inhabited by ''P. icterotis xanthogenys'' is generalised as eucalypt and sheoak, the trees moitch, wandoo (''Eucalyptus wandoo''), wurak and in tall mallee country or the habitat at the rock, or sighing, sheoak ('' Allocasuarina huegeliana''). This subspecies feeds at seeding wandoo, ''Acacia huegeliana'', ''Glischrocaryon flavescens

''Glischrocaryon flavescens'' is a perennial herb with woody roots that occurs in southern and western Australia.

Taxonomy

The species was first described by James Drummond,

The current combination, ''Glischrocaryon flavescens'', was the res ...

'' and '' Olearia revoluta'' and flowering ''Eucalyptus eremophila

''Eucalyptus eremophila'', commonly known as the sand mallet or tall sand mallee, is a species of Mallet (habit), mallet that is Endemism, endemic to semi-arid regions of Western Australia. It has smooth pale brown and greyish bark, narrow lance- ...

'' and ''Melaleuca acuminata

''Melaleuca acuminata'', commonly known as mallee honeymyrtle is a plant in the myrtle family, Myrtaceae and is native to Australia and widespread in temperate areas of the continent. It is an erect shrub to about usually found in mallee woodla ...

''.

Behaviour

The western rosella usually socialises in pairs, but congregates in groups of twenty or so to forage when the season or opportunity permits; numbers in a flock are occasionally recorded up to twenty-six. The birds are discreet in their behaviours—more so than other rosellas—and will remain unobserved when feeding on the ground beneath theunderstory

In forestry and ecology, understory (American English), or understorey (Commonwealth English), also known as underbrush or undergrowth, includes plant life growing beneath the forest canopy without penetrating it to any great extent, but abov ...

of a woodland or sheltering during the day in the dense foliage of trees. The usual tendency of individuals is to remain sedentary, although birds may venture out to abundant sources of seed. Individuals feeding in the open are not usually disturbed by human presence and can be approached quite closely. They appear to move with ease as they walk, and in their undulating flight, when the wing is drawn to their side. Their flight is more 'buoyant' than the laden efforts of the other larger species of the genus.

Breeding

The breeding habits of the western rosella have not been well-studied; females enter nesting hollows from July, with males doing so from mid-August. Eggs are laid from late August to late September and hatch late September to late October. Young birds fledge (leave the nest) late October to mid-November. The group in a study at Wickepin and Dudinin ( Kulin Shire) was observed to begin occupancy of nest sites in July, the routine of the female being fed by the male being established in the week before laying the brood. The western rosella nests in hollows and spout-shaped holes of living and dead trees, generally eucalypts and most commonly karri and wandoo. The trees are generally large and old, with one study establishing an average age of 290 years for the host tree. Eucalypts are a preferred tree species in which to lay their eggs, the dominant ''Eucalyptus marginata

''Eucalyptus marginata'', commonly known as jarrah, djarraly in Noongar language and historically as Swan River mahogany, is a plant in the myrtle family, Myrtaceae and is endemic to the south-west of Western Australia. It is a tree with rough ...

'' of jarrah forest, or in the tall forest tree karri, but they especially favour wandoo. Holes in tree stumps and fence posts are also used. Other trees selected include eucalypts such as marri, wurak, yandee '' E. loxophleba'' (york gum) and moitch (flooded gum).

The hollows are usually a meter or so deep, and those that have dust created by boring insects in the bottom are preferred. The brood is laid directly onto the wood dust or debris in the cavity selected; the site is otherwise unadorned. The dimensional description of the nest site, relating height, depth and entrance size used by the species, was included in a study of animals occupying tree cavities in jarrah forest, and intended to assist in determining the amount of suitable habitat removed and remaining after logging. The nest site is typically a spout shaped entrance, between in width, at a hollow between in depth leading to a green limb.

One brood is usually reared per breeding season, though often two are in captivity. The clutch size is between two and seven (rarely nine) eggs, with the average being around six. The shell has a slight gloss, and the shape is elliptical. The average size of eggs is . Measurements from a sample of 29 eggs gave a size range of × . Only the female incubates the eggs, leaving the nest in the morning and afternoon to eat food found by the male. The male remains close to the site, feeding at ground level and moving to an upper branch to call when catering to the brooding female.

The young emerge from the egg after an incubation period of 23 to 25 days, and leave the nest approximately five weeks after that. The nestlings have yellowish bills and display down at the rear that is pale grey, after they emerge from their egg. The success rate of egg numbers surviving to become independent individuals, while assumed to be seasonally variable, was measured in one survey to be 72%.

Feeding

The diet consists primarily of seeds, often those of introduced weeds and crops, although typically from eucalypt, sheoak and other native plants of the wooded environment. This is supplemented with nectar and insects especially during the breeding and feeding of young. The harvesting of introduced species includes the capeweed (''Arctotheca calendula

''Arctotheca calendula'' is a plant in the sunflower family commonly known as capeweed, plain treasureflower, cape dandelion, or cape marigold because it originates from the Cape Province in South Africa. It is also found in neighboring KwaZulu ...

''), thistles (''Carduus

''Carduus'' is a genus of flowering plants in the family Asteraceae, and the tribe Cardueae, one of two genera considered to be true thistles, the other being ''Cirsium''. Plants of the genus are known commonly as plumeless thistles.

'' spp.), flatweed (''Hypochaeris

''Hypochaeris'' is a genus of plants in the family Asteraceae. Many species are known as cat's ear. These are annual and perennial herbs generally bearing flower heads with yellow ray florets. These plants may resemble or be confused with dande ...

'' spp.) and the subterranean clover ('' Trifolium subterraneum''). Nectar, insects and their larvae, and fruit are also eaten, especially during the breeding season.

They exhibit little caution in rural areas, gleaning seeds at paddocks after harvests or inside buildings and

They exhibit little caution in rural areas, gleaning seeds at paddocks after harvests or inside buildings and animal pen

A pen is an enclosure for holding livestock. It may also perhaps be used as a term for an enclosure for other animals such as pets that are unwanted inside the house. The term describes types of enclosures that may confine one or many animal ...

s. The habit of visiting colonial farmland for seed and soft fruit, and lack of concern at human presence, was first reported by Gould in the years immediately following the region's settlement by the English. Tom Carter later extended this familiarity of the species to its casual entrance into buildings in search of food. A 1984 study of three parrots of the Southwest, all of which were observed to feed mainly on seed and fruit of introduced species, noted that the impact on soft fruit crops was less than red-capped parrot and Port Lincoln ''Barnardius zonarius'' parrot species. The damage to crops is regarded as minimal, appearing to eat fruit in orchards already damaged by those parrots and mainly gleaning for seed when feeding near protea

''Protea'' () is a genus of South African flowering plants, also called sugarbushes (Afrikaans: ''suikerbos'').

Etymology

The genus ''Protea'' was named in 1735 by Carl Linnaeus, possibly after the Greek god Proteus, who could change his form a ...

flower crops.

Conservation status

For the perceived impact on agriculture, the species had been declaredvermin

Vermin (colloquially varmint(s) or varmit(s)) are pests or nuisance animals that spread diseases or destroy crops or livestock. Since the term is defined in relation to human activities, which species are included vary by region and enterpr ...

by the Western Australian state in 1921. The western rosella remained a declared agricultural pest until 1998, when it was instead declared to be a 'protected native species' and its destruction was prohibited. The state's governmental response was to warn of prosecution and issue general advice and licensing for the use of non-lethal firearms and netting over trees for deterrence; licenses for the extermination of the species were available on application in 2009. The conservation status of the species is as protected fauna, and of the inland subspecies is one of "likely to become extinct". In the assessment of the inland ''P. icterotis xanthogenys'' for the federal government's ''Action Plan for Australian Birds'' 2000 it was assigned the status of 'near threatened'. The 2013 assessment by the International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

(IUCN) on their IUCN redlist

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is the world's most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biologi ...

assigns a status of species of least concern

A least-concern species is a species that has been categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as evaluated as not being a focus of species conservation because the specific species is still plentiful in the wild. T ...

. It notes the species has become less common and locally extinct and the population trend is declining due to removal of habitat. Like most species of parrot

Parrots, also known as psittacines (), are birds of the roughly 398 species in 92 genera comprising the order Psittaciformes (), found mostly in tropical and subtropical regions. The order is subdivided into three superfamilies: the Psittacoid ...

s, the western rosella is protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

CITES (shorter name for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as the Washington Convention) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals from the threats of interna ...

(CITES). It is placed on the Appendix II list of vulnerable species, which makes the import, export and trade of listed wild-caught animals illegal.

''P. icterotis'' was used in a comparative study of tolerance in some Australian birds to sodium fluoroacetate

Sodium fluoroacetate is an organofluorine chemical compound with the formula FCH2CO2Na. This colourless salt has a taste similar to that of sodium chloride and is used as a rodenticide.

History and production

The effectiveness of sodium fluoroa ...

, a highly toxic substance that occurs in plants of the southwest and commercially branded as "1080", to evaluate their sensitivity against the exposure and mobility of other species. This species and the red-capped parrot—both endemic—express a high tolerance of the potentially lethal salt.

Captivity

Western rosellas are a popular bird in aviaries and for

Western rosellas are a popular bird in aviaries and for zoological garden

A zoo (short for zoological garden; also called an animal park or menagerie) is a facility in which animals are kept within enclosures for public exhibition and often bred for conservation purposes.

The term ''zoological garden'' refers to zool ...

s, displaying the favourable characteristics of related species without the reputation for aggression and raucous vocalisation. Their status in Australian aviculture is classified as secure.

The species is able to breed in the first year, and females may lay up to two broods. Along with a reputation as being placid in nature, the success of their reproduction has increased the population in captivity. An individual cock, aged twelve and onward, was reported by one enthusiast (Whelan, 1977) to have sired twenty-seven progeny over four seasons. Popular interest in the captive form, red-backed Western rosella, which purports or adopts the subspecific description, ''P. icterotis xanthogenys'' (Salvadori), was supported by research published in Western Australia. The author (Philpott, 1986) sought to identify and discriminate plumage between the red-backed (inland) and nominate form, nominally the subspecies of coastal regions ''P. icterotis icterotis''. Several characteristics were identified, and later tabulated and summarised by workers in aviculture. Apart from the more subdued green and yellow of the inland form, the chin is white—rather than yellow—extending out to lighten the cheek patch. The same red-backed individuals were observed to have a second stripe at the underwing of fledglings, less distinct and closer to the base of the secondary feathers. This disappears from view after two months and altogether in the males of the form.

Sexing individuals by comparison of the colouring does not present the difficulties found in other captive rosellas, being markedly gender dimorphic they are easily assigned. Unusually, head scratching is done by arching out the foot behind and over the wing. As with the white-cheeked rosella

The pale-headed rosella (''Platycercus adscitus''), is a broad-tailed parrot of the genus ''Platycercus'' native to northeastern Australia. It is a moderate-size parrot with a pale yellow head, predominantly white cheeks, scalloped black and gold ...

s, the underwing stripe that is characteristic of juveniles in the genus is retained into maturity by the females. Nesting boxes in aviaries are destroyed if not reinforced, chewing on logs is preferred and these provide hollows for laying a clutch of eggs. The breeding season occurs from September until January, the clutch of four to five eggs is incubated in around twenty days. Fledging is about twenty-five days after hatching, full adult feathers appear at around fourteen months.

''P. icterotis'' had been successfully maintained in 19th century aviaries and menagerie

A menagerie is a collection of captive animals, frequently exotic, kept for display; or the place where such a collection is kept, a precursor to the modern Zoo, zoological garden.

The term was first used in 17th-century France, in reference to ...

s in Australia and overseas. From the beginning of the 20th century, confirmation emerges of them also being bred and raised in captivity. The specimens painted by Lear, two living captives in England, were published in ''Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae'' between 1830 and 1832. The first record of breeding in England was by two aviculturalists in July 1908, with another reporting success later that year. A bird breeder in Kendal

Kendal, once Kirkby in Kendal or Kirkby Kendal, is a market town and civil parish in the South Lakeland district of Cumbria, England, south-east of Windermere and north of Lancaster. Historically in Westmorland, it lies within the dale of th ...

produced young from 1910 to 1915. The species became uncommon in English aviculture during the 1950s, and those available said to be poor specimens. An attempt was made to breed a wild caught pair imported under license. Hybrids between this species and mealy rosella, and less successfully with red-rumps, were also produced there.

In a sampling of captive birds in Poland for detection of the bacteria ''Chlamydophila psittaci

''Chlamydia psittaci'' is a lethal intracellular parasite, intracellular bacterial species that may cause Endemism, endemic Bird, avian chlamydiosis, epizootic outbreaks in mammals, and respiratory psittacosis in humans. Potential hosts include ...

'', implicated in the infectious disease psittacosis

Psittacosis—also known as parrot fever, and ornithosis—is a zoonotic infectious disease in humans caused by a bacterium called ''Chlamydia psittaci'' and contracted from infected parrots, such as macaws, cockatiels, and budgerigars, and from ...

, the testing of a single specimen of ''P. icterotis'' in the baseline data set of apparently uninfected birds was found to be positive.

References

Cited sources

;classification * ** Schodde, R. in Schodde, R. & Mason, I.J. 1997. Aves (Columbidae to Coraciidae). In, Houston, W.W.K. & Wells, A. (eds). ''Zoological Catalogue of Australia''. Melbourne : CSIRO Publishing, Australia Vol. 37.2 xiii 440 pp. 79* ** ;texts * * * * * * * {{Good articlewestern rosella

The western rosella (''Platycercus icterotis''), or moyadong, is a species of parrot endemic to southwestern Australia. The head and underparts are bright red, and the back is mottled black; a yellow patch at the cheek distinguishes it from oth ...

Endemic birds of Southwest Australia

western rosella

The western rosella (''Platycercus icterotis''), or moyadong, is a species of parrot endemic to southwestern Australia. The head and underparts are bright red, and the back is mottled black; a yellow patch at the cheek distinguishes it from oth ...