Plasmodium falciparum on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Plasmodium falciparum'' is a unicellular

Falciparum malaria was familiar to the

Falciparum malaria was familiar to the

''P. falciparum'' does not have a fixed structure but undergoes continuous change during the course of its life cycle. A sporozoite is spindle-shaped and 10–15 μm long. In the liver it grows into an ovoid schizont of 30–70 μm in diameter. Each schizont produces merozoites, each of which is roughly 1.5 μm in length and 1 μm in diameter. In the erythrocyte the merozoite form a ring-like structure, becoming a trophozoite. A trophozoites feed on the haemoglobin and forms a granular pigment called

''P. falciparum'' does not have a fixed structure but undergoes continuous change during the course of its life cycle. A sporozoite is spindle-shaped and 10–15 μm long. In the liver it grows into an ovoid schizont of 30–70 μm in diameter. Each schizont produces merozoites, each of which is roughly 1.5 μm in length and 1 μm in diameter. In the erythrocyte the merozoite form a ring-like structure, becoming a trophozoite. A trophozoites feed on the haemoglobin and forms a granular pigment called

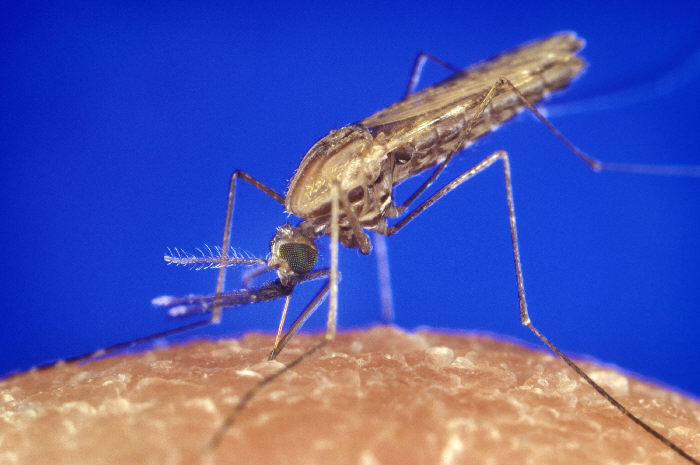

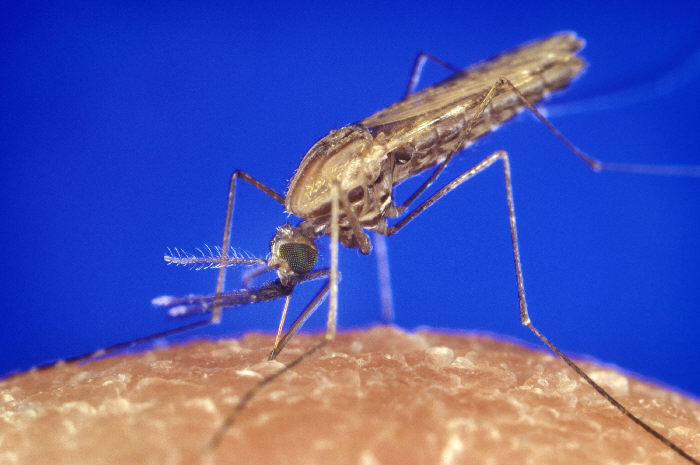

Humans are the intermediate hosts in which asexual reproduction occurs, and female anopheline mosquitos are the definitive hosts harbouring the sexual reproduction stage.

Humans are the intermediate hosts in which asexual reproduction occurs, and female anopheline mosquitos are the definitive hosts harbouring the sexual reproduction stage.

Infection in humans begins with the bite of an infected female ''Anopheles'' mosquito. Out of about 460 species of '' Anopheles''

Infection in humans begins with the bite of an infected female ''Anopheles'' mosquito. Out of about 460 species of '' Anopheles''

protozoa

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic tissues and debris. Histor ...

n parasite

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted structurally to this way of lif ...

of human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

s, and the deadliest species of ''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a vert ...

'' that causes malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or deat ...

in humans. The parasite is transmitted through the bite of a female '' Anopheles'' mosquito

Mosquitoes (or mosquitos) are members of a group of almost 3,600 species of small flies within the family Culicidae (from the Latin ''culex'' meaning "gnat"). The word "mosquito" (formed by ''mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish for "lit ...

and causes the disease's most dangerous form, falciparum malaria. It is responsible for around 50% of all malaria cases. ''P. falciparum'' is therefore regarded as the deadliest parasite in humans. It is also associated with the development of blood cancer (Burkitt's lymphoma

Burkitt lymphoma is a cancer of the lymphatic system, particularly B lymphocytes found in the germinal center. It is named after Denis Parsons Burkitt, the Irish surgeon who first described the disease in 1958 while working in equatorial Afr ...

) and is classified as a Group 2A (probable) carcinogen.

The species originated from the malarial parasite '' Laverania'' found in gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four ...

s, around 10,000 years ago. Alphonse Laveran

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran (18 June 1845 – 18 May 1922) was a French physician who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1907 for his discoveries of parasitic protozoans as causative agents of infectious diseases such as mala ...

was the first to identify the parasite in 1880, and named it ''Oscillaria malariae''. Ronald Ross discovered its transmission by mosquito in 1897. Giovanni Battista Grassi elucidated the complete transmission from a female anopheline mosquito to humans in 1898. In 1897, William H. Welch created the name ''Plasmodium falciparum'', which ICZN formally adopted in 1954. ''P. falciparum'' assumes several different forms during its life cycle. The human-infective stage are sporozoites from the salivary gland of a mosquito. The sporozoites grow and multiply in the liver

The liver is a major organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for digestion and growth. In humans, it ...

to become merozoites. These merozoites invade the erythrocytes

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "holl ...

(i.e. red blood cells) to form trophozoites, schizonts and gametocytes, during which the symptoms of malaria are produced. In the mosquito, the gametocytes undergo sexual reproduction to a zygote

A zygote (, ) is a eukaryotic cell formed by a fertilization event between two gametes. The zygote's genome is a combination of the DNA in each gamete, and contains all of the genetic information of a new individual organism.

In multicell ...

, which turns into ookinete. Ookinete forms oocyte

An oocyte (, ), oöcyte, or ovocyte is a female gametocyte or germ cell involved in reproduction. In other words, it is an immature ovum, or egg cell. An oocyte is produced in a female fetus in the ovary during female gametogenesis. The femal ...

s from which sporozoites are formed.

As of the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level o ...

''World Malaria Report 2021'', there were 241 million cases of malaria worldwide in 2020, resulting in an estimated 627,000 deaths. Nearly all malarial deaths are caused by ''P. falciparum'', and 95% of such cases occur in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

. Children under five years of age are most affected, accounting for 80% of the total deaths. In Sub-Saharan Africa, almost 100% of cases were due to ''P. falciparum'', whereas in most other malarial countries, other, less virulent plasmodial species predominate.

History

Falciparum malaria was familiar to the

Falciparum malaria was familiar to the ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, who gave the general name (''pyretós'') "fever". Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

(c. 460–370 BCE) gave several descriptions on tertian fever and quartan fever. It was prevalent throughout the ancient Egyptian and Roman civilizations. It was the Romans who named the disease "malaria"—''mala'' for bad, and ''aria'' for air, as they believed that the disease was spread by contaminated air, or miasma.

Discovery

A German physician, Johann Friedrich Meckel, must have been the first to see ''P. falciparum'' but without knowing what it was. In 1847, he reported the presence of black pigment granules from the blood and spleen of a patient who died of malaria. The French Army physicianCharles Louis Alphonse Laveran

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran (18 June 1845 – 18 May 1922) was a French physician who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1907 for his discoveries of parasitic protozoans as causative agents of infectious diseases such as malaria ...

, while working at Bône Hospital (now Annaba

Annaba ( ar, عنّابة, "Place of the Jujubes"; ber, Aânavaen), formerly known as Bon, Bona and Bône, is a seaport city in the northeastern corner of Algeria, close to the border with Tunisia. Annaba is near the small Seybouse Ri ...

in Algeria), correctly identified the parasite as a causative pathogen of malaria in 1880. He presented his discovery before the French Academy of Medicine

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with France ...

in Paris, and published it in ''The Lancet

''The Lancet'' is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal and one of the oldest of its kind. It is also the world's highest-impact academic journal. It was founded in England in 1823.

The journal publishes original research articles, ...

'' in 1881. He gave it the scientific name ''Oscillaria malariae''. However, his discovery was received with skepticism, mainly because by that time, leading physicians such as Theodor Albrecht Edwin Klebs and Corrado Tommasi-Crudeli

Corrado Tommasi-Crudeli (31 January 1834 to 31 May 1900) was an Italian physician known for his works in pathology and hygiene. He studied for his medical degree at the University of Pisa. He was trained in pathology under the German pathologist R ...

claimed that they had discovered a bacterium (which they called ''Bacillus malariae'') as the pathogen of malaria. Laveran's discovery was only widely accepted after five years when Camillo Golgi

Camillo Golgi (; 7 July 184321 January 1926) was an Italian biologist and pathologist known for his works on the central nervous system. He studied medicine at the University of Pavia (where he later spent most of his professional career) betwee ...

confirmed the parasite using better microscopes and staining techniques. Laveran was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine ( sv, Nobelpriset i fysiologi eller medicin) is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute, Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or ...

in 1907 for his work. In 1900, the Italian zoologist Giovanni Battista Grassi categorized ''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a vert ...

'' species based on the timing of fever in the patient; malignant tertian malaria was caused by ''Laverania malariae'' (now ''P. falciparum''), benign tertian malaria by ''Haemamoeba vivax'' (now ''P. vivax

''Plasmodium vivax'' is a protozoal parasite and a human pathogen. This parasite is the most frequent and widely distributed cause of recurring malaria. Although it is less virulent than ''Plasmodium falciparum'', the deadliest of the five human ...

''), and quartan malaria by ''Haemamoeba malariae'' (now '' P. malariae'').

The British physician Patrick Manson formulated the mosquito-malaria theory

Mosquito-malaria theory (or sometimes mosquito theory) was a scientific theory developed in the latter half of the 19th century that solved the question of how malaria was transmitted. The theory proposed that malaria was transmitted by mosquitoes ...

in 1894; until that time, malarial parasites were believed to be spread in air as miasma, a Greek word for pollution. His colleague Ronald Ross of the Indian Medical Service validated the theory while working in India. Ross discovered in 1897 that malarial parasites lived in certain mosquitoes. The next year, he demonstrated that a malarial parasite of birds could be transmitted by mosquitoes from one bird to another. Around the same time, Grassi demonstrated that ''P. falciparum'' was transmitted in humans only by female anopheline mosquito (in his case ''Anopheles claviger

''Anopheles claviger'' is a mosquito species found in Palearctic realm covering Europe, North Africa, northern Arabian Peninsula, and northern Asia. It is responsible for transmitting malaria in some of these regions. The mosquito is made up of ...

''). Ross, Manson and Grassi were nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1902. Under controversial circumstances, only Ross was selected for the award.

There was a long debate on the taxonomy. It was only in 1954 the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature

The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is an organization dedicated to "achieving stability and sense in the scientific naming of animals". Founded in 1895, it currently comprises 26 commissioners from 20 countries.

Orga ...

officially approved the binominal ''Plasmodium falciparum''. The valid genus ''Plasmodium'' was created by two Italian physicians Ettore Marchiafava and Angelo Celli in 1885. The Greek word ''plasma'' means "mould" or "form"; ''oeidēs'' meaning "to see" or "to know." The species name was introduced by an American physician William Henry Welch in 1897. It is derived from the Latin ''falx'', meaning "sickle" and ''parum'' meaning "like or equal to another".

Origin and evolution

''P. falciparum'' is now generally accepted to have evolved from '' Laverania'' (a subgenus of ''Plasmodium'' found in apes) species present in gorilla in Western Africa. Genetic diversity indicates that the human protozoan emerged around 10,000 years ago. The closest relative of ''P. falciparum'' is ''P. praefalciparum'', a parasite ofgorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four ...

s, as supported by mitochondrial

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

, apicoplast

An apicoplast is a derived non-photosynthetic plastid found in most Apicomplexa, including '' Toxoplasma gondii'', and ''Plasmodium falciparum'' and other ''Plasmodium'' spp. (parasites causing malaria), but not in others such as ''Cryptosporidium ...

ic and nuclear DNA

Nuclear DNA (nDNA), or nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid, is the DNA contained within each cell nucleus of a eukaryotic organism. It encodes for the majority of the genome in eukaryotes, with mitochondrial DNA and plastid DNA coding for the rest. ...

sequences. These two species are closely related to the chimpanzee parasite ''P. reichenowi'', which was previously thought to be the closest relative of ''P. falciparum''. ''P. falciparum'' was also once thought to originate from a parasite of birds.

Levels of genetic polymorphism

Polymorphism, polymorphic, polymorph, polymorphous, or polymorphy may refer to:

Computing

* Polymorphism (computer science), the ability in programming to present the same programming interface for differing underlying forms

* Ad hoc polymorphis ...

are extremely low within the ''P. falciparum'' genome compared to that of closely related, ape infecting species of ''Plasmodium'' (including ''P. praefalciparum''). This suggests that the origin of ''P. falciparum'' in humans is recent, as a single ''P. praefalciparum'' strain became capable of infecting humans. The genetic information of ''P. falciparum'' has signaled a recent expansion that coincides with the agricultural revolution. It is likely that the development of extensive agriculture increased mosquito population densities by giving rise to more breeding sites, which may have triggered the evolution and expansion of ''P. falciparum''.

Structure

''P. falciparum'' does not have a fixed structure but undergoes continuous change during the course of its life cycle. A sporozoite is spindle-shaped and 10–15 μm long. In the liver it grows into an ovoid schizont of 30–70 μm in diameter. Each schizont produces merozoites, each of which is roughly 1.5 μm in length and 1 μm in diameter. In the erythrocyte the merozoite form a ring-like structure, becoming a trophozoite. A trophozoites feed on the haemoglobin and forms a granular pigment called

''P. falciparum'' does not have a fixed structure but undergoes continuous change during the course of its life cycle. A sporozoite is spindle-shaped and 10–15 μm long. In the liver it grows into an ovoid schizont of 30–70 μm in diameter. Each schizont produces merozoites, each of which is roughly 1.5 μm in length and 1 μm in diameter. In the erythrocyte the merozoite form a ring-like structure, becoming a trophozoite. A trophozoites feed on the haemoglobin and forms a granular pigment called haemozoin

Haemozoin is a disposal product formed from the digestion of blood by some blood-feeding parasites. These hematophagous organisms such as malaria parasites ('' Plasmodium spp.''), ''Rhodnius'' and ''Schistosoma'' digest haemoglobin and releas ...

. Unlike those of other ''Plasmodium'' species, the gametocytes of ''P. falciparum'' are elongated and crescent-shaped, by which they are sometimes identified. A mature gametocyte is 8–12 μm long and 3–6 μm wide. The ookinete is also elongated measuring about 18–24 μm. An oocyst is rounded and can grow up to 80 μm in diameter. Microscopic examination of a blood film reveals only early (ring-form) trophozoites and gametocytes that are in the peripheral blood. Mature trophozoites or schizonts in peripheral blood smears, as these are usually sequestered in the tissues. On occasion, faint, comma-shaped, red dots are seen on the erythrocyte surface. These dots are Maurer's cleft Maurer's clefts are membranous structures seen in the red blood cell during infection with ''Plasmodium falciparum''. The function and contents of Maurer's clefts are not completely known; however, they appear to play a role in trafficking of Plasmo ...

and are secretory organelles that produce proteins and enzymes essential for nutrient uptake and immune evasion processes.

The apical complex, which is actually a combination of organelles, is an important structure. It contains secretory organelles called rhoptries and micronemes, which are vital for mobility, adhesion, host cell invasion, and parasitophorous vacuole formation. As an apicomplexan

The Apicomplexa (also called Apicomplexia) are a large phylum of parasitic alveolates. Most of them possess a unique form of organelle that comprises a type of non-photosynthetic plastid called an apicoplast, and an apical complex structure. The ...

, it harbours a plastid, an apicoplast

An apicoplast is a derived non-photosynthetic plastid found in most Apicomplexa, including '' Toxoplasma gondii'', and ''Plasmodium falciparum'' and other ''Plasmodium'' spp. (parasites causing malaria), but not in others such as ''Cryptosporidium ...

, similar to plant chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it ...

s, which they probably acquired by engulfing (or being invaded by) a eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bact ...

alga

Algae ( , ; : alga ) are any of a large and diverse group of photosynthetic, eukaryotic organisms. The name is an informal term for a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from u ...

and retaining the algal plastid as a distinctive organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' t ...

encased within four membranes. The apicoplast is involved in the synthesis of lipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids incl ...

s and several other compounds and provides an attractive drug target. During the asexual blood stage of infection, an essential function of the apicoplast is to produce the isoprenoid precursors isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) via the MEP (non-mevalonate) pathway.

Genome

In 1995 the Malaria Genome Project was set up to sequence the genome of ''P. falciparum''. The genome of itsmitochondrion

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is use ...

was reported in 1995, that of the nonphotosynthetic plastid

The plastid (Greek: πλαστός; plastós: formed, molded – plural plastids) is a membrane-bound organelle found in the cells of plants, algae, and some other eukaryotic organisms. They are considered to be intracellular endosymbiotic cyanobac ...

known as the apicoplast in 1996, and the sequence of the first nuclear chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins ar ...

(chromosome 2) in 1998. The sequence of chromosome 3 was reported in 1999 and the entire genome was reported on 3 October 2002. The roughly 24-megabase genome is extremely AT-rich (about 80%) and is organised into 14 chromosomes. Just over 5,300 genes were described. Many genes involved in antigenic variation are located in the subtelomeric

Subtelomeres are segments of DNA between telomeric caps and chromatin.

Structure

Telomeres are specialized protein– DNA constructs present at the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes, which prevent them from degradation and end-to-end chromosomal f ...

regions of the chromosomes. These are divided into the ''var'', ''rif'', and ''stevor'' families. Within the genome, there exist 59 ''var'', 149 ''rif'', and 28 ''stevor'' genes, along with multiple pseudogenes

Pseudogenes are nonfunctional segments of DNA that resemble functional genes. Most arise as superfluous copies of functional genes, either directly by DNA duplication or indirectly by reverse transcription of an mRNA transcript. Pseudogenes are ...

and truncations. It is estimated that 551, or roughly 10%, of the predicted nuclear-encoded proteins are targeted to the apicoplast

An apicoplast is a derived non-photosynthetic plastid found in most Apicomplexa, including '' Toxoplasma gondii'', and ''Plasmodium falciparum'' and other ''Plasmodium'' spp. (parasites causing malaria), but not in others such as ''Cryptosporidium ...

, while 4.7% of the proteome

The proteome is the entire set of proteins that is, or can be, expressed by a genome, cell, tissue, or organism at a certain time. It is the set of expressed proteins in a given type of cell or organism, at a given time, under defined conditions. ...

is targeted to the mitochondria.

Life cycle

Humans are the intermediate hosts in which asexual reproduction occurs, and female anopheline mosquitos are the definitive hosts harbouring the sexual reproduction stage.

Humans are the intermediate hosts in which asexual reproduction occurs, and female anopheline mosquitos are the definitive hosts harbouring the sexual reproduction stage.

In humans

Infection in humans begins with the bite of an infected female ''Anopheles'' mosquito. Out of about 460 species of '' Anopheles''

Infection in humans begins with the bite of an infected female ''Anopheles'' mosquito. Out of about 460 species of '' Anopheles'' mosquito

Mosquitoes (or mosquitos) are members of a group of almost 3,600 species of small flies within the family Culicidae (from the Latin ''culex'' meaning "gnat"). The word "mosquito" (formed by ''mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish for "lit ...

, more than 70 species transmit falciparum malaria. '' Anopheles gambiae'' is one of the best known and most prevalent vectors, particularly in Africa.

The infective stage called the sporozoite is released from the salivary glands through the proboscis of the mosquito to enter through the skin during feeding. The mosquito saliva contains antihaemostatic and anti-inflammatory enzymes that disrupt blood clotting and inhibit the pain reaction. Typically, each infected bite contains 20–200 sporozoites. A proportion of sporozoites invade liver cells (hepatocyte

A hepatocyte is a cell of the main parenchymal tissue of the liver. Hepatocytes make up 80% of the liver's mass.

These cells are involved in:

* Protein synthesis

* Protein storage

* Transformation of carbohydrates

* Synthesis of cholesterol, ...

s). The sporozoites move in the bloodstream by gliding

Gliding is a recreational activity and competitive air sport in which pilots fly unpowered aircraft known as gliders or sailplanes using naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmosphere to remain airborne. The word ''soaring'' is ...

, which is driven by a motor made up of the proteins actin

Actin is a protein family, family of Globular protein, globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in myofibril, muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all Eukaryote, eukaryotic cel ...

and myosin

Myosins () are a superfamily of motor proteins best known for their roles in muscle contraction and in a wide range of other motility processes in eukaryotes. They are ATP-dependent and responsible for actin-based motility.

The first myosin (M ...

beneath their plasma membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment (t ...

.

Liver stage or exo-erythrocytic schizogony

Entering the hepatocytes, the parasite loses its apical complex and surface coat, and transforms into a trophozoite. Within theparasitophorous vacuole

The parasitophorous vacuole (PV) is a structure produced by apicomplexan parasites in the cells of its host. The PV allows the parasite to develop while protected from the phagolysosomes of the host cell.

The PV is a bubble-like compartment ma ...

of the hepatocyte, it undergoes 13–14 rounds of mitosis and meiosis which produce a syncytial cell ( coenocyte) called a schizont. This process is called schizogony. A schizont contains tens of thousands of nuclei. From the surface of the schizont, tens of thousands of haploid (1n) daughter cells called merozoites emerge. The liver stage can produce up to 90,000 merozoites, which are eventually released into the bloodstream in parasite-filled vesicles called merosomes.

Blood stage or erythrocytic schizogony

Merozoites use theapicomplexan

The Apicomplexa (also called Apicomplexia) are a large phylum of parasitic alveolates. Most of them possess a unique form of organelle that comprises a type of non-photosynthetic plastid called an apicoplast, and an apical complex structure. The ...

invasion organelles ( apical complex, pellicle and surface coat) to recognize and enter the host erythrocyte (red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "holl ...

). The merozoites first bind to the erythrocyte in a random orientation. It then reorients such that the apical complex is in proximity to the erythrocyte membrane. The parasite forms a parasitophorous vacuole, to allow for its development inside the erythrocyte

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "holl ...

. This infection cycle occurs in a highly synchronous fashion, with roughly all of the parasites throughout the blood in the same stage of development. This precise clocking mechanism has been shown to be dependent on the human host's own circadian rhythm

A circadian rhythm (), or circadian cycle, is a natural, internal process that regulates the sleep–wake cycle and repeats roughly every 24 hours. It can refer to any process that originates within an organism (i.e., endogenous) and responds to ...

.

Within the erythrocyte, the parasite metabolism depends on the digestion of haemoglobin. The clinical symptoms of malaria such as fever, anemia, and neurological disorder are produced during the blood stage.

The parasite can also alter the morphology of the erythrocyte, causing knobs on the erythrocyte membrane. Infected erythrocytes are often sequestered in various human tissues or organs, such as the heart, liver and brain. This is caused by parasite-derived cell surface proteins being present on the erythrocyte membrane, and it is these proteins that bind to receptors on human cells. Sequestration in the brain causes cerebral malaria, a very severe form of the disease, which increases the victim's likelihood of death.

=Trophozoite

= After invading the erythrocyte, the parasite loses its specific invasion organelles (apical complex and surface coat) and de-differentiates into a round trophozoite located within a parasitophorous vacuole. The trophozoite feeds on the haemoglobin of erythrocyte, digesting its proteins and converting (by biocrystallization) the remaining heme into an insoluble and chemically inert β-hematin crystals called haemozoin. The young trophozoite (or "ring" stage, because of its morphology on stained blood films) grows substantially before undergoing multiplication.=Schizont

= At the schizont stage, the parasite replicates its DNA multiple times and multiple mitotic divisions occur asynchronously. Cell division and multiplication in the erythrocyte is called erythrocytic schizogony. Each schizont forms 16-18 merozoites. The red blood cells are ruptured by the merozoites. The liberated merozoites invade fresh erythrocytes. A free merozoite is in the bloodstream for roughly 60 seconds before it enters another erythrocyte. The duration of one complete erythrocytic schizogony is approximately 48 hours. This gives rise to the characteristic clinical manifestations of falciparum malaria, such as fever and chills, corresponding to the synchronous rupture of the infected erythrocytes.=Gametocyte

= Some merozoites differentiate into sexual forms, male and female gametocytes. These gametocytes take roughly 7–15 days to reach full maturity, through the process called gametocytogenesis. These are then taken up by a female ''Anopheles'' mosquito during a blood meal.Incubation period

The time of appearance of the symptoms from infection (calledincubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infectious disease, the in ...

) is shortest for ''P. falciparum'' among ''Plasmodium'' species. An average incubation period is 11 days, but may range from 9 to 30 days. In isolated cases, prolonged incubation periods as long as 2, 3 or even 8 years have been recorded. Pregnancy and co-infection with HIV

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of '' Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the immu ...

are important conditions for delayed symptoms. Parasites can be detected from blood samples by the 10th day after infection (pre-patent period).

In mosquitoes

Within the mosquito midgut, the female gamete maturation process entails slight morphological changes, becoming more enlarged and spherical. The male gametocyte undergoes a rapid nuclear division within 15 minutes, producing eight flagellatedmicrogamete

{{Short pages monitor