Pius VII on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pope Pius VII ( it, Pio VII; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823), was head of the

Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti was born in

Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti was born in

Following the death of Pope Pius VI, by then virtually France's prisoner, at Valence in 1799, the

Following the death of Pope Pius VI, by then virtually France's prisoner, at Valence in 1799, the

One of Pius VII's first acts was appointing the minor cleric

One of Pius VII's first acts was appointing the minor cleric

As pope, he followed a policy of cooperation with the French-established Republic and Empire. He was present at the coronation of Napoleon I in 1804. He even participated in France's

As pope, he followed a policy of cooperation with the French-established Republic and Empire. He was present at the coronation of Napoleon I in 1804. He even participated in France's

From the time of his election as pope to the fall of

From the time of his election as pope to the fall of

In addition, Pius VII named 12 cardinals whom he reserved "''

In addition, Pius VII named 12 cardinals whom he reserved "''

Text (EN)

* Ex quo Ecclesiam

* Il trionfo

* Vineam quam plantavit

Text (IT)

*

Text (IT)

''Catholic Encyclopedia'' "Pope Pius VII"

online

* Caiani, Ambrogio. 2021. ''To Kidnap a Pope: Napoleon and Pius VII''. Yale University Press. * Hales, E. E. Y. "Napoleon's duel with the Pope" ''History Today'' (May 1958) 8#5 pp 328–33. * Hales, E. E. Y. ''The Emperor and the Pope: The Story of Napoleon and Pius VII'' (1961

online

* Thompson, J. M.''Napoleon Bonaparte: His Rise and Fall'' (1951) pp 251–75 * * *

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and ruler of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. Chiaramonti was also a monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedica ...

of the Order of Saint Benedict

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict ( la, Ordo Sancti Benedicti, abbreviated as OSB), are a Christian monasticism, monastic Religious order (Catholic), religious order of the Catholic Church following the Rule of Saint Benedic ...

in addition to being a well-known theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

and bishop.

Chiaramonti was made Bishop of Tivoli

The Diocese of Tivoli ( la, Dioecesis Tiburtina) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in Latium, Italy, which has existed since the 2nd century. In 2002 territory was added to it from the Territorial Abbey ...

in 1782, and resigned that position upon his appointment as Bishop of Imola

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Imola ( la, Diocesis Imolensis) is a territory in Romagna, northern Italy. It is a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Bologna.

in 1785. That same year, he was made a cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

. In 1789, the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

took place, and as a result a series of anti-clerical governments came into power in the country. In 1796, during the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

, French troops under Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

invaded Rome and captured Pope Pius VI

Pope Pius VI ( it, Pio VI; born Count Giovanni Angelo Braschi, 25 December 171729 August 1799) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 15 February 1775 to his death in August 1799.

Pius VI condemned the French Revoluti ...

, taking him as a prisoner to France, where he died in 1799. The following year, after a ''sede vacante

''Sede vacante'' ( in Latin.) is a term for the state of a diocese while without a bishop. In the canon law of the Catholic Church, the term is used to refer to the vacancy of the bishop's or Pope's authority upon his death or resignation.

Hi ...

'' period lasting approximately six months, Chiaramonti was elected to the papacy, taking the name Pius VII.

Pius at first attempted to take a cautious approach in dealing with Napoleon. With him he signed the Concordat of 1801

The Concordat of 1801 was an agreement between Napoleon Bonaparte and Pope Pius VII, signed on 15 July 1801 in Paris. It remained in effect until 1905, except in Alsace-Lorraine, where it remains in force. It sought national reconciliation b ...

, through which he succeeded in guaranteeing religious freedom for Catholics living in France, and was present at his coronation as Emperor of the French

Emperor of the French (French: ''Empereur des Français'') was the title of the monarch and supreme ruler of the First and the Second French Empires.

Details

A title and office used by the House of Bonaparte starting when Napoleon was procla ...

in 1804. In 1809, however, during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, Napoleon once again invaded the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

, resulting in his excommunication through the papal bull ''Quum memoranda

''Quum memoranda'' was a papal bull issued by Pope Pius VII in 1809. It was a response to a decree issued by Emperor Napoleon, on 17 May 1809, which incorporated the remnants of the Papal States into the French Empire, during the Napoleonic War ...

''. Pius VII was taken prisoner and transported to France. He remained there until 1814 when, after the French were defeated, he was permitted to return to Rome, where he was greeted warmly as a hero and defender of the faith.

Pius lived the remainder of his life in relative peace. His papacy saw a significant growth of the Catholic Church in the United States

With 23 percent of the United States' population , the Catholic Church is the country's second largest religious grouping, after Protestantism, and the country's largest single church or Christian denomination where Protestantism is divided i ...

, where Pius established several new dioceses. Pius VII died in 1823 at age 81.

In 2007, Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI ( la, Benedictus XVI; it, Benedetto XVI; german: link=no, Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, , on 16 April 1927) is a retired prelate of the Catholic church who served as the head of the Church and the sovereign ...

began the process towards canonizing him as a saint, and he was granted the title Servant of God

"Servant of God" is a title used in the Catholic Church to indicate that an individual is on the first step toward possible canonization as a saint.

Terminology

The expression "servant of God" appears nine times in the Bible, the first five in th ...

.

Biography

Early life

Cesena

Cesena (; rgn, Cisêna) is a city and ''comune'' in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy, served by Autostrada A14, and located near the Apennine Mountains, about from the Adriatic Sea. The total population is 97,137.

History

Cesena was o ...

in 1742, the youngest son of Count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

Scipione Chiaramonti (30 April 1698 – 13 September 1750). His mother, Giovanna Coronata (d. 22 November 1777), was the daughter of the Marquess

A marquess (; french: marquis ), es, marqués, pt, marquês. is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman wi ...

Ghini; through her, the future Pope Pius VII was related to the Braschi family of Pope Pius VI

Pope Pius VI ( it, Pio VI; born Count Giovanni Angelo Braschi, 25 December 171729 August 1799) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 15 February 1775 to his death in August 1799.

Pius VI condemned the French Revoluti ...

after marriage on 10 November 1713. Though his family was of noble status, they were not wealthy but rather, were of middle-class stock.

His maternal grandparents were Barnaba Eufrasio Ghini and Isabella de' conti Aguselli. His paternal grandparents were Giacinto Chiaramonti (1673–1725) and Ottavia Maria Altini; his paternal great-grandparents were Scipione Chiaramonti (1642–1677) and Ottavia Maria Aldini. His paternal great-great grandparents were Chiaramonte Chiaramonti and Polissena Marescalchi.

His siblings were Giacinto Ignazio (19 September 1731 – 7 June 1805), Tommaso (19 December 1732 – 8 December 1799) and Ottavia (1 June 1738 – 7 May 1814).

Like his brothers, he attended the Collegio dei Nobili in Ravenna

Ravenna ( , , also ; rgn, Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 408 until its collapse in 476. It then served as the cap ...

but decided to join the Order of Saint Benedict

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict ( la, Ordo Sancti Benedicti, abbreviated as OSB), are a Christian monasticism, monastic Religious order (Catholic), religious order of the Catholic Church following the Rule of Saint Benedic ...

at the age of 14 on 2 October 1756 as a novice at the Abbey of Santa Maria del Monte in Cesena. Two years after this on 20 August 1758, he became a professed member and assumed the name of ''Gregorio''. He taught at Benedictine colleges in Parma

Parma (; egl, Pärma, ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, Giuseppe Verdi, music, art, prosciutto (ham), Parmigiano-Reggiano, cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,292 ...

and Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, and was ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform va ...

a priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

on 21 September 1765.

Episcopate and cardinalate

A series of promotions resulted after his relative, Giovanni Angelo Braschi, was electedPope Pius VI

Pope Pius VI ( it, Pio VI; born Count Giovanni Angelo Braschi, 25 December 171729 August 1799) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 15 February 1775 to his death in August 1799.

Pius VI condemned the French Revoluti ...

(1775–99). A few years before this election occurred, in 1773, Chiaramonti became the personal confessor to Braschi. In 1776, Pius VI appointed the 34-year-old Dom Dom or DOM may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Dom (given name), including fictional characters

* Dom (surname)

* Dom La Nena (born 1989), stage name of Brazilian-born cellist, singer and songwriter Dominique Pinto

* Dom people, an et ...

Gregory, who had been teaching at the Monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

of Sant'Anselmo

Sant'Anselmo all'Aventino ( en, Saint Anselm on the Aventine) is a complex located on the Piazza Cavalieri di Malta Square on the Aventine Hill in Rome's Ripa rione and overseen by the Benedictine Confederation and the Abbot Primate. The ''San ...

in Rome, as honorary abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The fem ...

''in commendam

In canon law, commendam (or ''in commendam'') was a form of transferring an ecclesiastical benefice ''in trust'' to the ''custody'' of a patron. The phrase ''in commendam'' was originally applied to the provisional occupation of an ecclesiastical ...

'' of his monastery. Although this was an ancient practice, it drew complaints from the monks of the community, as monastic communities generally felt it was not in keeping with the Rule of St. Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' ( la, Regula Sancti Benedicti) is a book of precepts written in Latin in 516 by St Benedict of Nursia ( AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's Ru ...

.

In December 1782, the pope appointed Dom Gregory as the Bishop of Tivoli

The Diocese of Tivoli ( la, Dioecesis Tiburtina) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in Latium, Italy, which has existed since the 2nd century. In 2002 territory was added to it from the Territorial Abbey ...

, near Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. Pius VI soon named him, in February 1785, the Cardinal-Priest of San Callisto, and as the Bishop of Imola

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Imola ( la, Diocesis Imolensis) is a territory in Romagna, northern Italy. It is a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Bologna.

, an office he held until 1816.

When the French Revolutionary Army

The French Revolutionary Army (french: Armée révolutionnaire française) was the French land force that fought the French Revolutionary Wars from 1792 to 1804. These armies were characterised by their revolutionary fervour, their poor equipme ...

invaded Italy in 1797, Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

Chiaramonti counseled temperance and submission to the newly created Cisalpine Republic

The Cisalpine Republic ( it, Repubblica Cisalpina) was a sister republic of France in Northern Italy that existed from 1797 to 1799, with a second version until 1802.

Creation

After the Battle of Lodi in May 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte organized t ...

. In a letter that he addressed to the people of his diocese, Chiaramonti asked them to comply "... in the current circumstances of change of government (...)" to the authority of the victorious general Commander-in-Chief of the French army. In his Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating Nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus, Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people Observance of Christmas by country, around t ...

homily

A homily (from Greek ὁμιλία, ''homilía'') is a commentary that follows a reading of scripture, giving the "public explanation of a sacred doctrine" or text. The works of Origen and John Chrysostom (known as Paschal Homily) are considered ex ...

that year, he asserted that there was no opposition between a democratic form of government and being a good Catholic: "Christian virtue makes men good democrats.... Equality is not an idea of philosophers but of Christ...and do not believe that the Catholic religion is against democracy."Thomas Bokenkotter, ''Church and Revolution: Catholics in the Struggle for Democracy and Social Justice'' (NY: Doubleday, 1998), 32

Papacy

Election

Following the death of Pope Pius VI, by then virtually France's prisoner, at Valence in 1799, the

Following the death of Pope Pius VI, by then virtually France's prisoner, at Valence in 1799, the conclave

A papal conclave is a gathering of the College of Cardinals convened to elect a bishop of Rome, also known as the pope. Catholics consider the pope to be the apostolic successor of Saint Peter and the earthly head of the Catholic Church.

Co ...

to elect his successor met on 30 November 1799 in the Benedictine Monastery of San Giorgio in Venice. There were three main candidates, two of whom proved to be unacceptable to the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

, whose candidate, Alessandro Mattei

Alessandro Mattei (20 February 1744, Rome – 20 April 1820) was an Italian Cardinal, and a significant figure in papal diplomacy of the Napoleonic period. He was from the Roman aristocratic House of Mattei.

He became Archbishop of Ferrara in 1 ...

, could not secure sufficient votes. However, Carlo Bellisomi also was a candidate, though not favoured by Austrian cardinals; a "virtual veto" was imposed against him in the name of Franz II

Francis II (german: Franz II.; 12 February 1768 – 2 March 1835) was the last Holy Roman Emperor (from 1792 to 1806) and the founder and Emperor of the Austrian Empire, from 1804 to 1835. He assumed the title of Emperor of Austria in response ...

and carried out by Cardinal Franziskus Herzan von Harras.

After several months of stalemate, Jean-Sifrein Maury

Jean-Sifrein Maury (; 26 June 1746 – 10 May 1817) was a French cardinal, archbishop of Paris, and former bishop of Montefiascone.

Biography

The son of a cobbler, he was born at Valréas in the Comtat-Venaissin, the enclave within France th ...

proposed Chiaramonti as a compromise candidate. On 14 March 1800, Chiaramonti was elected pope, certainly not the choice of die-hard opponents of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, and took as his pontifical name Pius VII in honour of his immediate predecessor. He was crowned on 21 March, in the adjacent monastery church, by means of a rather unusual ceremony, wearing a papier-mâché

upright=1.3, Mardi Gras papier-mâché masks, Haiti

upright=1.3, Papier-mâché Catrinas, traditional figures for day of the dead celebrations in Mexico

Papier-mâché (, ; , literally "chewed paper") is a composite material consisting of p ...

papal tiara. The French had seized the tiaras held by the Holy See when occupying Rome and forcing Pius VI into exile. The new pope then left for Rome, sailing on a barely seaworthy Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

n ship, the ''Bellona'', which lacked even a galley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be used ...

. The twelve-day voyage ended at Pesaro

Pesaro () is a city and ''comune'' in the Italian region of Marche, capital of the Province of Pesaro e Urbino, on the Adriatic Sea. According to the 2011 census, its population was 95,011, making it the second most populous city in the Marche, ...

and he proceeded to Rome.

Negotiations and exile

One of Pius VII's first acts was appointing the minor cleric

One of Pius VII's first acts was appointing the minor cleric Ercole Consalvi

Ercole Consalvi (8 June 1757 – 24 January 1824) was a deacon and cardinal of the Catholic Church, who served twice as Cardinal Secretary of State for the Papal States and who played a crucial role in the post-Napoleonic reassertion of the le ...

, who had performed so ably as secretary to the recent conclave, to the College of Cardinals

The College of Cardinals, or more formally the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. its current membership is , of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Cardinals are appoi ...

and to the office of Cardinal Secretary of State

The Secretary of State of His Holiness (Latin: Secretarius Status Sanctitatis Suae,

it, Segretario di Stato di Sua Santità), commonly known as the Cardinal Secretary of State, presides over the Holy See's Secretariat of State, which is the ...

. Consalvi immediately left for France, where he was able to negotiate the Concordat of 1801

The Concordat of 1801 was an agreement between Napoleon Bonaparte and Pope Pius VII, signed on 15 July 1801 in Paris. It remained in effect until 1905, except in Alsace-Lorraine, where it remains in force. It sought national reconciliation b ...

with the First Consul

The Consulate (french: Le Consulat) was the top-level Government of France from the fall of the Directory in the coup of 18 Brumaire on 10 November 1799 until the start of the Napoleonic Empire on 18 May 1804. By extension, the term ''The Co ...

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

. While not effecting a return to the old Christian order, the treaty did provide certain civil guarantees to the Church, acknowledging "the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman religion" as that of the "majority of French citizens". See drop-down essay on "The Third Republic and the 1905 Law of Laïcité"

The main terms of the concordat between France and the pope included:

* A proclamation that "Catholicism was the religion of the great majority of the French" but was not the official religion, maintaining religious freedom, in particular with respect to Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

.

* The Pope had the right to depose bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

s.

* The state would pay clerical salaries and the clergy swore an oath of allegiance to the state.

* The church gave up all claims to church lands that were taken after 1790.

* Sunday was reestablished as a "festival", effective Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

Sunday, 18 April 1802.

As pope, he followed a policy of cooperation with the French-established Republic and Empire. He was present at the coronation of Napoleon I in 1804. He even participated in France's

As pope, he followed a policy of cooperation with the French-established Republic and Empire. He was present at the coronation of Napoleon I in 1804. He even participated in France's Continental Blockade

The Continental Blockade (), or Continental System, was a large-scale embargo against British trade by Napoleon Bonaparte against the British Empire from 21 November 1806 until 11 April 1814, during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon issued the Berlin ...

of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

, over the objections of his Secretary of State Consalvi, who was forced to resign. Despite this, France occupied and annexed

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

in 1809 and took Pius VII as their prisoner, exiling him to Savona

Savona (; lij, Sann-a ) is a seaport and ''comune'' in the west part of the northern Italy, Italian region of Liguria, capital of the Province of Savona, in the Riviera di Ponente on the Mediterranean Sea.

Savona used to be one of the chie ...

. On 15 November 1809 Pius VII consecrated the church at La Voglina, Valenza Po, Piemonte with the intention of the villa La Voglina becoming his spiritual base whilst in exile. Unfortunately his residency was short lived once Napoleon became aware of his intentions of establishing a permanent base and he was soon exiled to France. Despite this, the pope continued to refer to Napoleon as "my dear son" but added that he was "a somewhat stubborn son, but a son still".

This exile ended only when Pius VII signed the Concordat of Fontainebleau in 1813. One result of this new treaty was the release of the exiled cardinals, including Consalvi, who, upon re-joining the papal retinue, persuaded Pius VII to revoke the concessions he had made in it. This Pius VII began to do in March 1814, which led the French authorities to re-arrest many of the opposing prelates. Their confinement, however, lasted only a matter of weeks, as Napoleon abdicated

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

on 11 April of that year. As soon as Pius VII returned to Rome, he immediately revived the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

and the Index of Condemned Books.

Cardinal Bartolomeo Pacca, who was kidnapped along with Pope Pius VII, took the office of Pro-Secretary of State in 1808 and maintained his memoirs during his exile. His memoirs, written originally in Italian, have been translated into English (two volumes) and describe the ups and down of their exile and the triumphant return to Rome in 1814.

Pius VII's imprisonment did in fact come with one bright side for him. It gave him an aura that recognized him as a living martyr, so that when he arrived back in Rome in May 1814, he was greeted most warmly by the Italians as a hero.

Relationship with Napoleon I

From the time of his election as pope to the fall of

From the time of his election as pope to the fall of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

in 1815, Pius VII's reign was completely taken up in dealing with France.

He and the Emperor were continually in conflict, often involving the French military leader's wishes for concessions to his demands. Pius VII wanted his own release from exile as well as the return of the Papal States, and, later on, the release of the 13 "Black Cardinals", i.e., the cardinals, including Consalvi, who had snubbed the marriage of Napoleon to Marie Louise Marie Louise or Marie-Louise may refer to:

People

*Marie Louise of Orléans (1662–1689), daughter of Philippe I, Duke of Orléans, queen consort of Charles II of Spain

*Marie Louise of Hesse-Kassel (1688–1765), daughter of Charles I, Landgrave ...

, believing that his previous marriage was still valid, and had been exiled and impoverished in consequence of their stand, along with several exiled or imprisoned prelates, priests, monks, nuns and other various supporters.

Restoration of the Jesuits

On 7 March 1801, Pius VII issued the brief "Catholicae fidei" that approved the existence of theSociety of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

and appointed its first superior general as Franciszek Kareu. This was the first step in the restoration of the order. On 31 July 1814, he signed the papal bull ''Sollicitudo omnium ecclesiarum'' which universally restored the Society of Jesus. He appointed Tadeusz Brzozowski as the Superior General of the order.

Opposition to slavery

Pius VII joined the declaration of the 1815Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

, represented by Cardinal Secretary of State Ercole Consalvi

Ercole Consalvi (8 June 1757 – 24 January 1824) was a deacon and cardinal of the Catholic Church, who served twice as Cardinal Secretary of State for the Papal States and who played a crucial role in the post-Napoleonic reassertion of the le ...

, and urged the suppression of the slave trade. This pertained particularly to places such as Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

where slavery was economically very important. The pope wrote a letter to King Louis XVIII of France dated 20 September 1814 and to the King John VI of Portugal

, house = Braganza

, father = Peter III of Portugal

, mother = Maria I of Portugal

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Queluz Palace, Queluz, Portugal

, death_date =

, death_place = Bemposta Palace, Lisbon, Portugal

, ...

in 1823 to urge the end of slavery. He condemned the slave trade and defined the sale of people as an injustice to the dignity of the human person. In his letter to the King of Portugal, he wrote: "the pope regrets that this trade in blacks, that he believed having ceased, is still exercised in some regions and even more cruel way. He begs and begs the King of Portugal that it implement all its authority and wisdom to extirpate this unholy and abominable shame."

Reinstitution of Jewish Ghetto

Under Napoleonic rule, the JewishRoman Ghetto

The Roman Ghetto or Ghetto of Rome ( it, Ghetto di Roma) was a Jewish ghetto established in 1555 in the Rione Sant'Angelo, in Rome, Italy, in the area surrounded by present-day Via del Portico d'Ottavia, Lungotevere dei Cenci, Via del Progresso ...

had been abolished and Jews were free to live and move where they would. Following the restoration of Papal rule, Pius VII re-instituted the confinement of Jews to the Ghetto, having the doors closed at nighttime.

Other activities

Pius VII issued an encyclical "Diu satis" in order to advocate a return to the values of theGospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

and universalized the feast of Our Lady of Sorrows

Our Lady of Sorrows ( la, Beata Maria Virgo Perdolens), Our Lady of Dolours, the Sorrowful Mother or Mother of Sorrows ( la, Mater Dolorosa, link=no), and Our Lady of Piety, Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows or Our Lady of the Seven Dolours are names ...

for 15 September. He condemned Freemasonry

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

and the movement of the Carbonari

The Carbonari () was an informal network of secret revolutionary societies active in Italy from about 1800 to 1831. The Italian Carbonari may have further influenced other revolutionary groups in France, Portugal, Spain, Brazil, Uruguay and Ru ...

in the encyclical Ecclesiam a Jesu Christo Ecclesiam a Jesu Christo was a Papal bull promulgated by Pius VII in 1821.

It stated that Freemasons must be excommunicated for their oath bound secrecy of the society and conspiracies against church and state.

It also linked Freemasonry with th ...

in 1821. Pius VII asserted that Freemasons must be excommunicated and it linked them with the Carbonari, an anti-clerical revolutionary group in Italy. All members of the Carbonari were also excommunicated.

Pius VII was multilingual and had the ability to speak Italian, French, English and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

.

Cultural innovations

Pius VII was a man of culture and attempted to reinvigorate Rome with archaeological excavations in Ostia which revealed ruins and icons from ancient times. He also had walls and other buildings rebuilt and restored theArch of Titus

The Arch of Titus ( it, Arco di Tito; la, Arcus Titi) is a 1st-century AD honorific arch, located on the Via Sacra, Rome, just to the south-east of the Roman Forum. It was constructed in 81 AD by the Roman emperor, Emperor Domitian shortly aft ...

. He ordered the construction of fountains and piazzas and erected the obelisk at Monte Pincio.

The pope also made sure Rome was a place for artists and the leading artists of the time like Antonio Canova

Antonio Canova (; 1 November 1757 – 13 October 1822) was an Italian Neoclassical sculptor, famous for his marble sculptures. Often regarded as the greatest of the Neoclassical artists,. his sculpture was inspired by the Baroque and the cl ...

and Peter von Cornelius

Peter von Cornelius (23 September 1783, Düsseldorf – 6 March 1867, Berlin) was a German painter; one of the main representatives of the Nazarene movement.

Life

Early years

Cornelius was born in Düsseldorf. From the age of twelve he attend ...

. He also enriched the Vatican Library

The Vatican Apostolic Library ( la, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, it, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana), more commonly known as the Vatican Library or informally as the Vat, is the library of the Holy See, located in Vatican City. Formally es ...

with numerous manuscripts and books. It was Pius VII who adopted the yellow and white flag of the Holy See as a response to the Napoleonic invasion of 1808.

Canonizations and beatifications

Throughout his pontificate, Pius VII canonized a total of five saints. On 24 May 1807, Pius VII canonizedAngela Merici

Angela Merici or Angela de Merici ( , ; 21 March 1474 – 27 January 1540) was an Italian religious educator, who is honored as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church. She founded the Company of St. Ursula in 1535 in Brescia, in which women ded ...

, Benedict the Moor

Benedict the Moor ( it, Benedetto da San Fratello; 1526 – 4 April 1589) was a Sicilian Franciscan friar who is venerated as a saint in the Catholic church. Born of enslaved Africans in San Fratello, he was freed at birth and became known for ...

, Colette Boylet, Francis Caracciolo

Francis Caracciolo (October 13, 1563 – June 4, 1608), born Ascanio Pisquizio, was an Italian Catholic priest who co-founded the Order of the Clerics Regular Minor with John Augustine Adorno and Fabrizio Caracciolo. He decided to adopt a relig ...

and Hyacintha Mariscotti

Hyacintha Mariscotti, or Hyacintha of Mariscotti ( it, Giacinta Marescotti) was an Italian nun of the Third Order Regular of St. Francis. She was born in 1585 of a noble family at Vignanello, in the Province of Viterbo, and died 30 January 1640 i ...

. He beatified a total of 27 individuals including Joseph Oriol

Joseph Oriol (José Orioli) ( ca, Sant Josep Oriol) (23 November 1650 – 23 March 1702) was a Spanish Roman Catholic priest now venerated as a saint in the Catholic Church who is called the "Thaumaturgus of Barcelona".

He was beatified under Po ...

, Berardo dei Marsi

Blessed Berardo dei Marsi (1079 – 3 November 1130) was a Catholic Italian cardinal. He was proclaimed Blessed in 1802 as he was deemed to be holy and that miracles were performed through his intercession.

Biography

Berardo dei Marsi was born in ...

, Giuseppe Maria Tomasi

Joseph Mary Tomasi ( it, Giuseppe Maria Tomasi di Lampedusa)(12 September 1649 – 1 January 1713) was an Italian Theatine Catholic priest, scholar, reformer and cardinal. His scholarship was a significant source of the reforms in the li ...

and Crispin of Viterbo

Crispino da Viterbo (13 November 1668 – 19 May 1750) - born Pietro Fioretti - was an Italian Roman Catholic professed religious from Order of Friars Minor Capuchin. Fioretti was an ardent devotee of the Mother of God and was consecrated to he ...

.

Consistories

Pius VII created 99 cardinals in nineteen consistories including notable ecclesial figures of that time such as Ercole Consalvi, Bartolomeo Pacca, and Carlo Odescalchi. The pope also named his two immediate successors as cardinals: Annibale della Genga and Francesco Saverio Castiglioni (the latter of whom it is said Pius VII and his successor would refer to as "Pius VIII"). In addition, Pius VII named 12 cardinals whom he reserved "''

In addition, Pius VII named 12 cardinals whom he reserved "''in pectore

''In pectore'' (Latin for "in the breast/heart") is a term used in the Catholic Church for an action, decision, or document which is meant to be kept secret. It is most often used when there is a papal appointment to the College of Cardinals wit ...

''". One died before his nomination could ever be published (he was originally nominated in the 1804 consistory), Marino Carafa di Belvedere resigned his cardinalate on 24 August 1807 upon citing a lack of family descendance, and Carlo Odescalchi resigned the cardinalate on 21 November 1838 to enter the Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

.

In 1801, according to Remigius Ritzler, Pius VII nominated Paolo Luigi Silva as a cardinal ''in pectore'', however, he died before his name could be published. As a result, Pius VII added the Archbishop of Palermo Domenico Pignatelli di Belmonte

Domenico Pignatelli di Belmonte (19 November 1730 – 5 February 1803) was an Italian Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church.

Biography

Prince Don Domenico Pignatelli di Belmonte was born on 19 November 1730 in Naples, Italy, the son of Prin ...

in his place. In the March 1816 consistory, the former bishop of Saint-Malo

The former Breton and French Catholic Diocese of Saint-Malo ( la, Dioecesis Alethensis, then la, Dioecesis Macloviensis, label=none) existed from at least the 7th century until the French Revolution. Its seat was at Aleth up to some point in th ...

Gabriel Cortois de Pressigny was among the cardinals created ''in pectore'' in the consistory, though he declined the promotion. Similarly, Giovanni Alliata declined the pope's offer for elevation in the same consistory. According to Niccolò del Re, the Vice-Camerlengo Tiberio Pacca would have been created a cardinal either in the March 1823 consistory, or a future one held by the pope. However, he suggests that a series of controversies beginning in 1820 prevented the pope from naming him to the Sacred College.

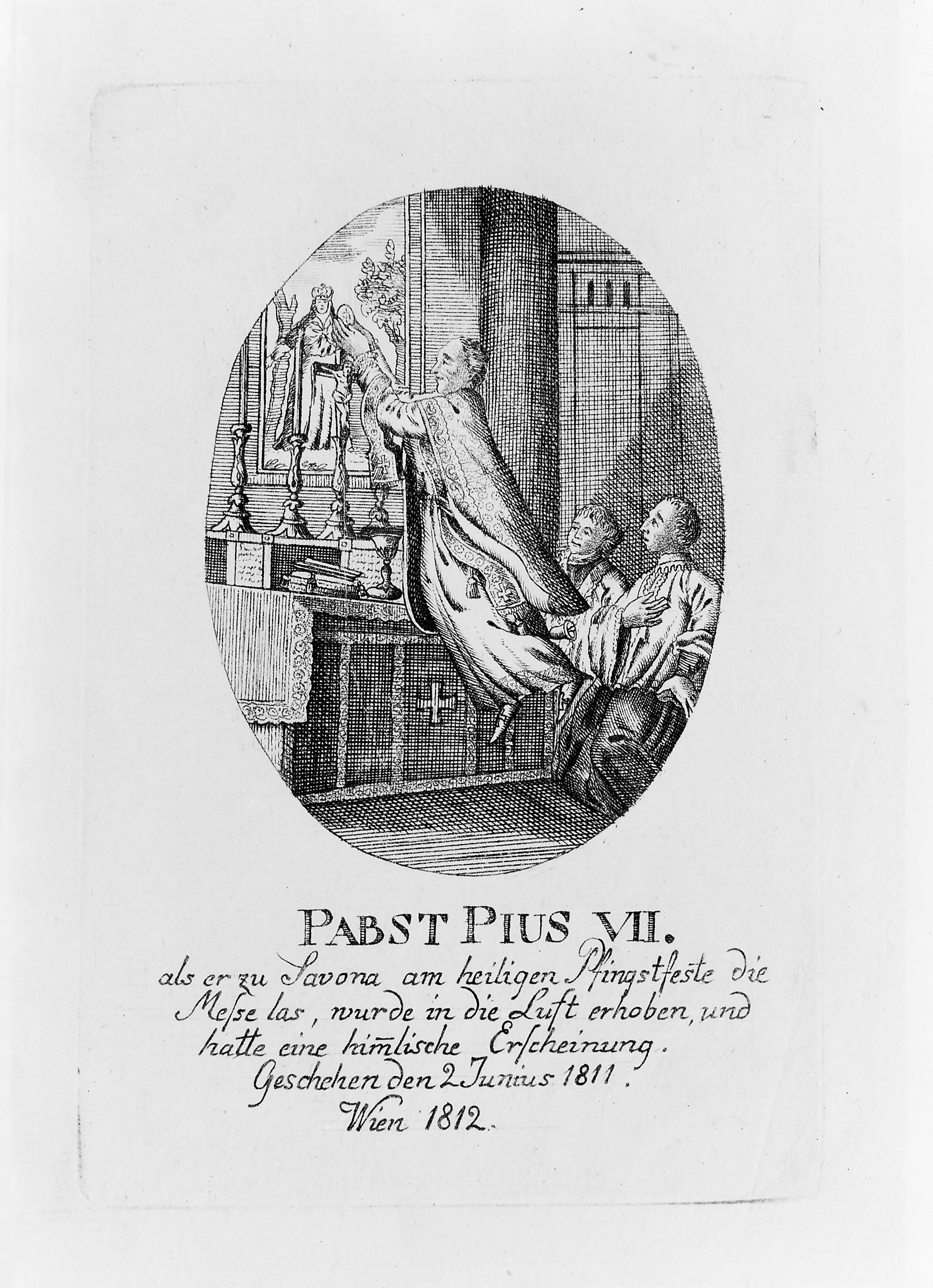

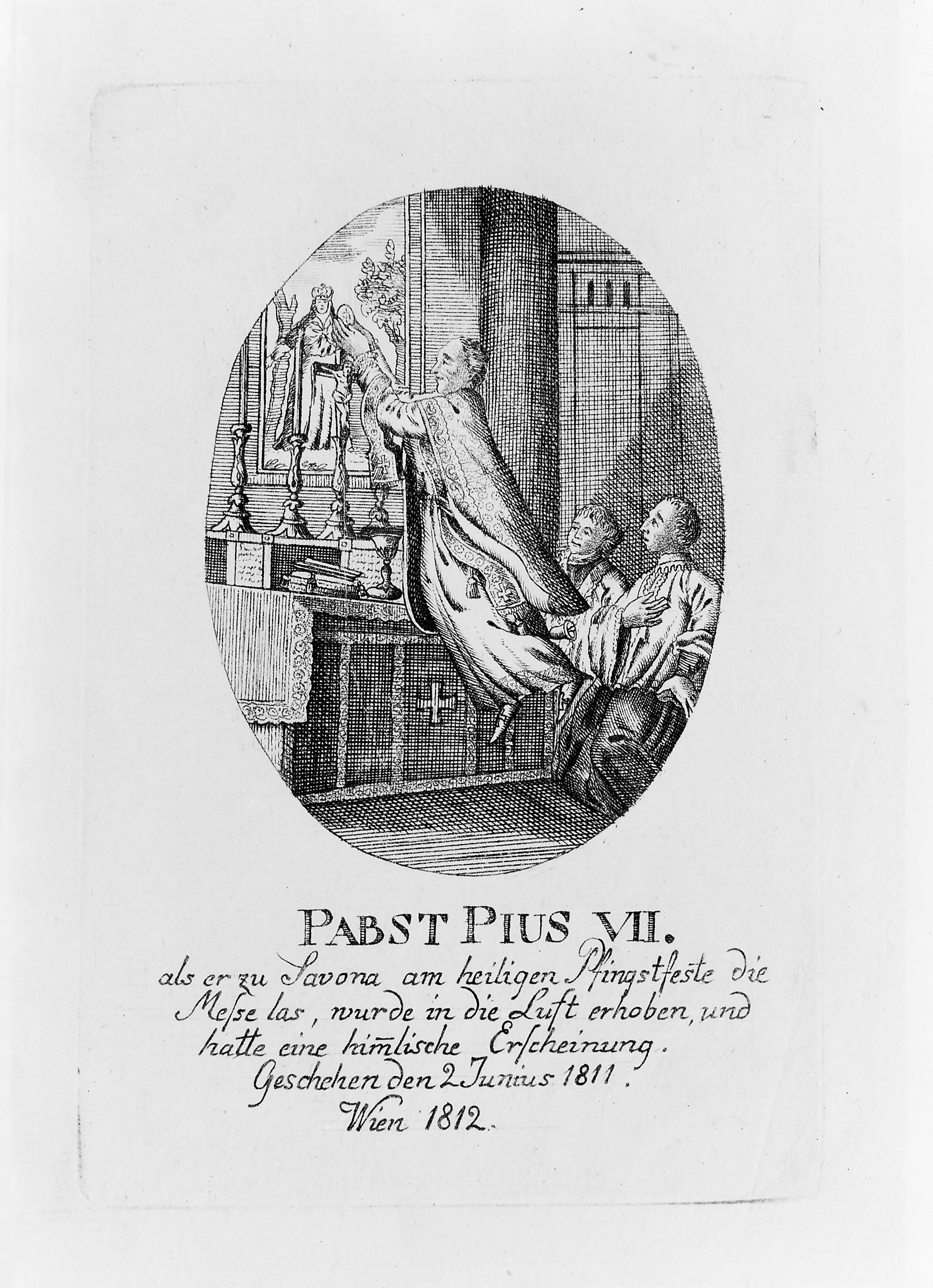

The possible miracle of Pius VII

On 15 August 1811 - theFeast of the Assumption

The Assumption of Mary is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Pope Pius XII defined it in 1950 in his apostolic constitution ''Munificentissimus Deus'' as follows:

We proclaim and define it to be a dogma revealed by Go ...

- it is recorded that the pope celebrated Mass and was said to have entered a trance and began to levitate in a manner that drew him to the altar. This particular episode aroused great wonder and awe among attendants which included the French soldiers guarding him who were in disbelief of what had occurred.

Relationship with the United States

On theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

' undertaking of the First Barbary War

The First Barbary War (1801–1805), also known as the Tripolitan War and the Barbary Coast War, was a conflict during the Barbary Wars, in which the United States and Sweden fought against Tripolitania. Tripolitania had declared war against Sw ...

to suppress the Muslim Barbary pirates

The Barbary pirates, or Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli, Libya, Tripoli. This area was known i ...

along the southern Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

coast, ending their kidnapping of Europeans for ransom and slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, Pius VII declared that the United States "had done more for the cause of Christianity than the most powerful nations of Christendom have done for ages."

For the United States, he established several new dioceses in 1808 for Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

and Bardstown. In 1821, he also established the dioceses of Charleston, Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

and Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

.

Condemnation of heresy

On 3 June 1816, Pius VII condemned the works ofMelkite

The term Melkite (), also written Melchite, refers to various Eastern Christianity, Eastern Christian churches of the Byzantine Rite and their members originating in the Middle East. The term comes from the common Central Semitic Semitic root, ro ...

bishop Germanos Adam

Germanos Adam (born in 1725 in Aleppo, Syria – died on 10 November 1809 in Zouk Mikael, Lebanon) was the Melkite Catholic bishop of the Melkite Greek Catholic Archeparchy of Aleppo during the late 18th century and a Christian theologian.

Life ...

. Adam's writings supported conciliarism

Conciliarism was a reform movement in the 14th-, 15th- and 16th-century Catholic Church which held that supreme authority in the Church resided with an ecumenical council, apart from, or even against, the pope.

The movement emerged in response to ...

, the view that the authority of ecumenical council

An ecumenical council, also called general council, is a meeting of bishops and other church authorities to consider and rule on questions of Christian doctrine, administration, discipline, and other matters in which those entitled to vote are ...

s was greater than that of the papacy.

Death and burial

In 1822, Pius VII reached his 80th birthday and his health was visibly declining. On 6 July 1823, he fractured his hip in a fall in the papal apartments and was bedridden from that point onward. In his final weeks he would often lose consciousness and would mutter the names of the cities that he had been ferried away to by the French forces. With theCardinal Secretary of State

The Secretary of State of His Holiness (Latin: Secretarius Status Sanctitatis Suae,

it, Segretario di Stato di Sua Santità), commonly known as the Cardinal Secretary of State, presides over the Holy See's Secretariat of State, which is the ...

Ercole Consalvi

Ercole Consalvi (8 June 1757 – 24 January 1824) was a deacon and cardinal of the Catholic Church, who served twice as Cardinal Secretary of State for the Papal States and who played a crucial role in the post-Napoleonic reassertion of the le ...

at his side, Pius VII died on 20 August at 5 a.m.

He was briefly interred in the Vatican grottoes but was later buried in a monument in Saint Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a church built in the Renaissance style located in Vatican City, the papal e ...

after his funeral on 25 August.

Beatification process

An application to commence beatification proceedings were lodged to theHoly See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome ...

on 10 July 2006 and received the approval of Cardinal Camillo Ruini

Camillo Ruini (; born 19 February 1931) is an Italian prelate of the Catholic Church who was made a cardinal in 1991. He served as president of the Italian Episcopal Conference from 1991 to 2007 and as Vicar General of the Diocese of Rome fr ...

(the Vicar of Rome) who transferred the request to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints

In the Catholic Church, the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints, previously named the Congregation for the Causes of Saints (), is the dicastery of the Roman Curia that oversees the complex process that leads to the canonization of saints, pa ...

. The Congregation - on 24 February 2007 - approved the opening of the cause responding to the call of the Ligurian bishops.

On 15 August 2007, the Holy See contacted the diocese of Savona-Noli with the news that Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI ( la, Benedictus XVI; it, Benedetto XVI; german: link=no, Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, , on 16 April 1927) is a retired prelate of the Catholic church who served as the head of the Church and the sovereign ...

had declared "nihil obstat

''Nihil obstat'' (Latin for "nothing hinders" or "nothing stands in the way") is a declaration of no objection that warrants censoring of a book, e.g., Catholic published books, to an initiative, or an appointment.

Publishing

The phrase ''ni ...

" (nothing stands against) the cause of beatification of the late pontiff, thus opening the diocesan process for this pope's beatification. He now has the title of Servant of God

"Servant of God" is a title used in the Catholic Church to indicate that an individual is on the first step toward possible canonization as a saint.

Terminology

The expression "servant of God" appears nine times in the Bible, the first five in th ...

. The official text declaring the opening of the cause was: "''Summus Pontifex Benedictus XVI declarat, ex parte Sanctae Sedis, nihil obstare quominus in Causa Beatificationis et Canonizationis Servi Dei Pii Barnabae Gregorii VII Chiaramonti''". Work on the cause commenced the following month in gathering documentation on the late pope.

He has since been elected as the patron of the Diocese of Savona and the patron of prisoners.

In late 2018 the Bishop of Savona announced that the cause for Pius VII would continue following the completion of initial preparation and investigation. The bishop named a new postulator and a diocesan tribunal which would begin work into the cause. The formal introduction to the cause (a diocesan investigation into the late pontiff's life) was held at a Mass celebrated in the Savona diocese on 31 October 2021.

The first postulator

A postulator is the person who guides a cause for beatification or canonization through the judicial processes required by the Roman Catholic Church. The qualifications, role and function of the postulator are spelled out in the ''Norms to be Obse ...

for the cause was Father Giovanni Farris (2007–18) and the current postulator since 2018 is Fr. Giovanni Margara.

Monuments

Pope Pius VII's monument (1831) inSt. Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a church built in the Renaissance style located in Vatican City, the papal e ...

, adorning his tomb, was created by the Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish a ...

sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen.

BibliographyFull list of Pius VII's writings (IT)

h2>

Encyclical

An encyclical was originally a circular letter sent to all the churches of a particular area in the ancient Roman Church. At that time, the word could be used for a letter sent out by any bishop. The word comes from the Late Latin (originally from ...

s

* Diu Satis Text (EN)

* Ex quo Ecclesiam

* Il trionfo

* Vineam quam plantavit

Motu proprio

In law, ''motu proprio'' (Latin for "on his own impulse") describes an official act taken without a formal request from another party. Some jurisdictions use the term ''sua sponte'' for the same concept.

In Catholic canon law, it refers to a do ...

* Le più colte

Le più colte (literally, "the most cultured") was an apostolic letter produced by Pope Pius VII in the first year of his pontificate (1801) in the form of a ''motu proprio'', written in Italian, which set out drastic reforms in agricultural poli ...

Text (IT)

Ecclesiam a Jesu Christo Ecclesiam a Jesu Christo was a Papal bull promulgated by Pius VII in 1821.

It stated that Freemasons must be excommunicated for their oath bound secrecy of the society and conspiracies against church and state.

It also linked Freemasonry with th ...

Text (IT)

See also

*Apostolic Prefecture of the United States

The Apostolic Prefecture of the United States ( la, Praefectura Apostolica Civitatum Foederatarum Americae Septentrionalis) was the earliest Roman Catholic ecclesiastical jurisdiction to be officially recognized after the United States declared i ...

*Cardinals created by Pius VII

Pope Pius VII (r. 1800–1823) created 99 cardinals in 19 consistories.

August 11, 1800

# Diego Innico Caracciolo

# Ercole Consalvi

October 20, 1800

# Luis María de Borbón y Vallabriga

February 23, 1801

# Giuseppe Firrao

# Ferdinan ...

* Jacob Anton Zallinger zum Thurn, papal councillor in German affairs (1805 - 1806)

*John Carroll John Carroll may refer to:

People Academia and science

*Sir John Carroll (astronomer) (1899–1974), British astronomer

*John Alexander Carroll (died 2000), American history professor

*John Bissell Carroll (1916–2003), American cognitive sci ...

, first US bishop

*List of popes

This chronological list of popes corresponds to that given in the ''Annuario Pontificio'' under the heading "I Sommi Pontefici Romani" (The Roman Supreme Pontiffs), excluding those that are explicitly indicated as antipopes. Published every ye ...

*Scipione Chiaramonti

Scipione Chiaramonti (21 June 1565 – 3 October 1652) was an Italian philosopher and noted opponent of Galileo.

Early life

The Chiaramonti family was noble and wealthy, claiming to have originated in Clermont and moved to Italy in the fourte ...

Notes

References

Citations

Sources

''Catholic Encyclopedia'' "Pope Pius VII"

Further reading

* * Anderson, Robin. ''Pope Pius VII'', TAN Books & Publishers, Inc., 2001. * Browne-Olf, Lillian. ''Their Name Is Pius'' (1941) pp 59–130online

* Caiani, Ambrogio. 2021. ''To Kidnap a Pope: Napoleon and Pius VII''. Yale University Press. * Hales, E. E. Y. "Napoleon's duel with the Pope" ''History Today'' (May 1958) 8#5 pp 328–33. * Hales, E. E. Y. ''The Emperor and the Pope: The Story of Napoleon and Pius VII'' (1961

online

* Thompson, J. M.''Napoleon Bonaparte: His Rise and Fall'' (1951) pp 251–75 * * *

Michael Matheus

Michael Matheus (born 27 March 1953, in Graach) is a German historian.

Life

Michael Matheus graduated from the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Gymnasium (Trier) in 1971. He studied history, political science and German at the universities of Trier, Bonn an ...

, Lutz Klinkhammer (eds.): ''Eigenbild im Konflikt. Krisensituationen des Papsttums zwischen Gregor VII. und Benedikt XV.'' Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, 2009, .

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Pius 07 Italian popes Bishops of Imola Bishops of Tivoli People from Cesena Pius VII, Pope Pius VII, Pope Cardinal-nephews 18th-century Italian Roman Catholic priests 19th-century Italian Roman Catholic priests Order of Saint Benedict Benedictine bishops Benedictine popes Burials at St. Peter's Basilica Italian Benedictines Popes 19th-century popes 19th-century venerated Christians Italian Servants of God Benedictine Servants of God Papal Servants of God Cardinals created by Pope Pius VI