Phrygia Salutaris on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; grc, Φρυγία, ''Phrygía'' ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River. After its conquest, it became a region of the great empires of the time.

Stories of the heroic age of Greek mythology tell of several legendary Phrygian kings:

* Gordias, whose

Phrygia describes an area on the western end of the high Anatolian plateau, an arid region quite unlike the forested lands to the north and west of it. Phrygia begins in the northwest where an area of dry steppe is diluted by the Sakarya and Porsuk river system and is home to the settlements of Dorylaeum near modern Eskişehir, and the Phrygian capital

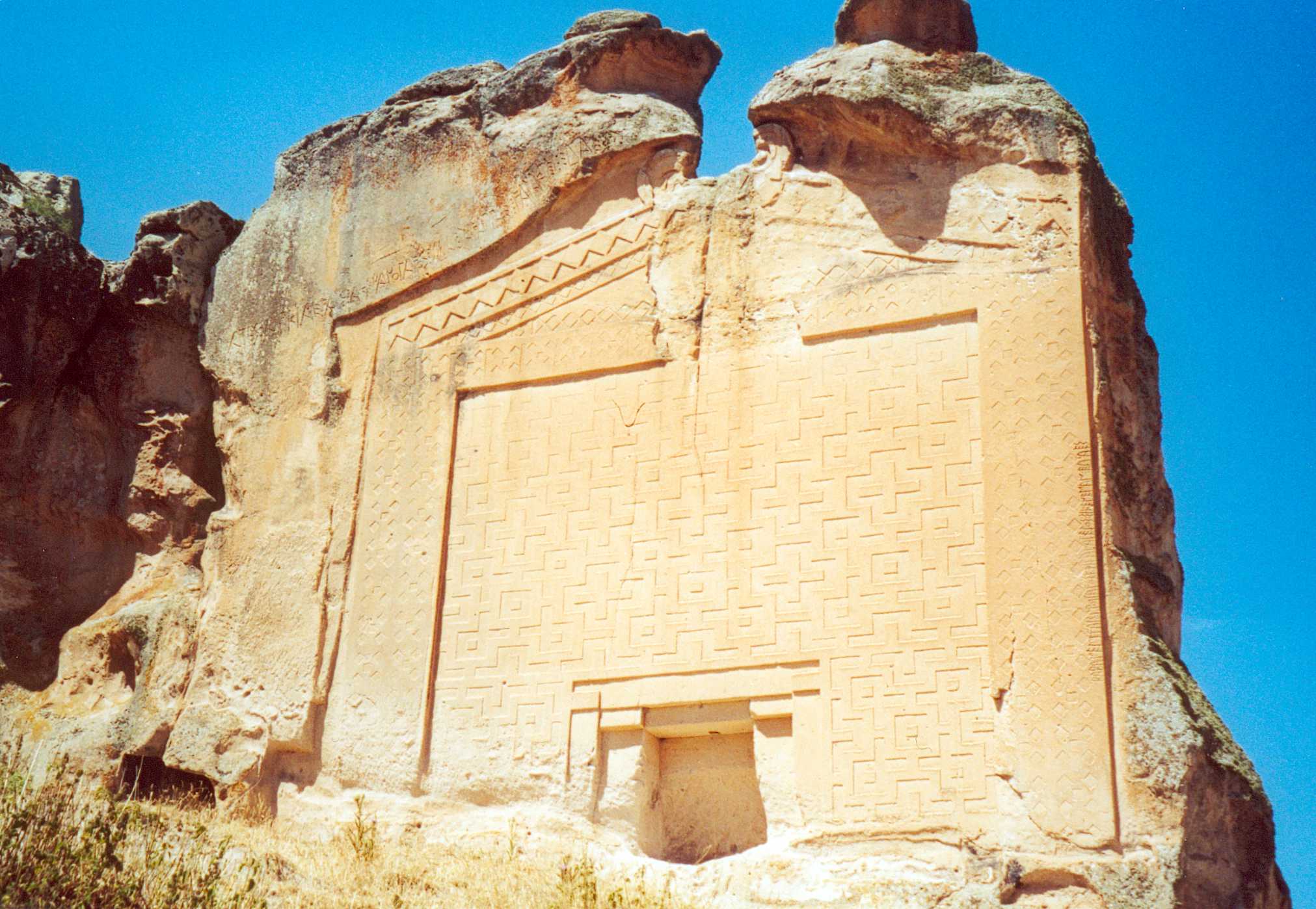

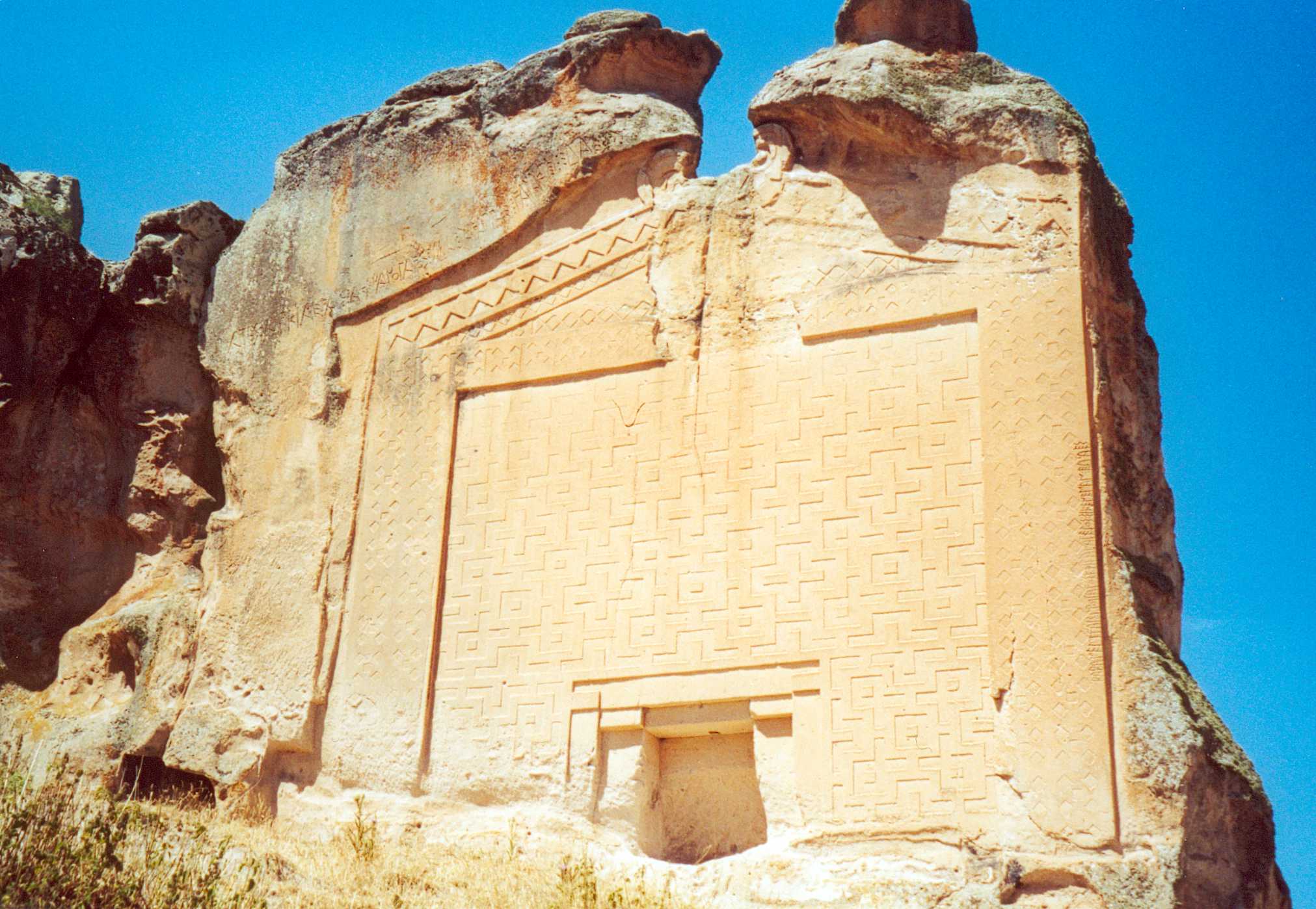

Phrygia describes an area on the western end of the high Anatolian plateau, an arid region quite unlike the forested lands to the north and west of it. Phrygia begins in the northwest where an area of dry steppe is diluted by the Sakarya and Porsuk river system and is home to the settlements of Dorylaeum near modern Eskişehir, and the Phrygian capital  South of Dorylaeum an important Phrygian settlement, Midas City (

South of Dorylaeum an important Phrygian settlement, Midas City (

No one has conclusively identified which of the many subjects of the Hittites might have represented early Phrygians. According to a classical tradition, popularized by Josephus, Phrygia can be equated with the country called Togarmah by the ancient Hebrews, which has in turn been identified as the Tegarama of Hittite texts and Til-Garimmu of Assyrian records. Josephus called Togarmah "the Thrugrammeans, who, as the Greeks resolved, were named Phrygians". However, the Greek source cited by Josephus is unknown, and it is unclear if there was any basis for the identification other than name similarity.

Scholars of the Hittites believe Tegarama was in eastern Anatolia – some locate it at Gurun – far to the east of Phrygia. Some scholars have identified Phrygia with the

No one has conclusively identified which of the many subjects of the Hittites might have represented early Phrygians. According to a classical tradition, popularized by Josephus, Phrygia can be equated with the country called Togarmah by the ancient Hebrews, which has in turn been identified as the Tegarama of Hittite texts and Til-Garimmu of Assyrian records. Josephus called Togarmah "the Thrugrammeans, who, as the Greeks resolved, were named Phrygians". However, the Greek source cited by Josephus is unknown, and it is unclear if there was any basis for the identification other than name similarity.

Scholars of the Hittites believe Tegarama was in eastern Anatolia – some locate it at Gurun – far to the east of Phrygia. Some scholars have identified Phrygia with the

According to the '' Bibliotheca'', the Greek hero Heracles slew a king Mygdon of the Bebryces in a battle in northwest Anatolia that if historical would have taken place about a generation before the Trojan War. According to the story, while traveling from Minoa to the

According to the '' Bibliotheca'', the Greek hero Heracles slew a king Mygdon of the Bebryces in a battle in northwest Anatolia that if historical would have taken place about a generation before the Trojan War. According to the story, while traveling from Minoa to the

During the 8th century BC, the Phrygian kingdom with its capital at Gordium in the upper

During the 8th century BC, the Phrygian kingdom with its capital at Gordium in the upper  A series of digs have opened Gordium as one of Turkey's most revealing archeological sites. Excavations confirm a violent destruction of Gordium around 675 BC. A tomb from the period, popularly identified as the "Tomb of Midas", revealed a wooden structure deeply buried under a vast tumulus, containing grave goods, a coffin, furniture, and food offerings (Archaeological Museum, Ankara).

A series of digs have opened Gordium as one of Turkey's most revealing archeological sites. Excavations confirm a violent destruction of Gordium around 675 BC. A tomb from the period, popularly identified as the "Tomb of Midas", revealed a wooden structure deeply buried under a vast tumulus, containing grave goods, a coffin, furniture, and food offerings (Archaeological Museum, Ankara).

Some time in the 540s BC, Phrygia passed to the Achaemenid (Great Persian) Empire when

Some time in the 540s BC, Phrygia passed to the Achaemenid (Great Persian) Empire when

In 133 BC, the remnants of Phrygia passed to Rome. For purposes of provincial administration, the Romans maintained a divided Phrygia, attaching the northeastern part to the province of

In 133 BC, the remnants of Phrygia passed to Rome. For purposes of provincial administration, the Romans maintained a divided Phrygia, attaching the northeastern part to the province of

The ruins of Gordion and Midas City prove that Phrygia had developed an advanced Bronze Age culture. This Phrygian culture interacted in a number of ways with Greek culture in various periods of history.

The "Great Mother", Cybele, as the Greeks and Romans knew her, was originally worshiped in the mountains of Phrygia, where she was known as "Mountain Mother". In her typical Phrygian form, she wears a long belted dress, a ''polos'' (a high cylindrical headdress), and a veil covering the whole body. The later version of Cybele was established by a pupil of Phidias, the sculptor

The ruins of Gordion and Midas City prove that Phrygia had developed an advanced Bronze Age culture. This Phrygian culture interacted in a number of ways with Greek culture in various periods of history.

The "Great Mother", Cybele, as the Greeks and Romans knew her, was originally worshiped in the mountains of Phrygia, where she was known as "Mountain Mother". In her typical Phrygian form, she wears a long belted dress, a ''polos'' (a high cylindrical headdress), and a veil covering the whole body. The later version of Cybele was established by a pupil of Phidias, the sculptor  The earliest traditions of Greek music derived from Phrygia, transmitted through the Greek colonies in Anatolia, and included the

The earliest traditions of Greek music derived from Phrygia, transmitted through the Greek colonies in Anatolia, and included the  Classical Greek iconography identifies the Trojan Paris as non-Greek by his Phrygian cap, which was worn by Mithras and survived into modern imagery as the " Liberty cap" of the American and

Classical Greek iconography identifies the Trojan Paris as non-Greek by his Phrygian cap, which was worn by Mithras and survived into modern imagery as the " Liberty cap" of the American and

The Phrygians are associated in Greek mythology with the

The Phrygians are associated in Greek mythology with the

Gordian Knot

The Gordian Knot is an Ancient Greek legend of Phrygian Gordium associated with Alexander the Great who is said to have cut the knot in 333 BC. It is often used as a metaphor for an intractable problem (untying an impossibly tangled knot) sol ...

would later be cut by Alexander the Great

* Midas, who turned whatever he touched to gold

* Mygdon In Greek mythology, Mygdon (Ancient Greek: Μύγδων) may refer to the following personages:

* Mygdon, son of Ares and muse Calliope, eponymous of Mygdones

* Mygdon of Bebryces, killed by Heracles, son of Poseidon.

* Mygdon of Phrygia, king w ...

, who warred with the Amazons

In Greek mythology, the Amazons (Ancient Greek: Ἀμαζόνες ''Amazónes'', singular Ἀμαζών ''Amazōn'', via Latin ''Amāzon, -ŏnis'') are portrayed in a number of ancient epic poems and legends, such as the Labours of Hercules, ...

According to Homer's '' Iliad'', the Phrygians participated in the Trojan War as close allies of the Trojans, fighting against the Achaeans. Phrygian power reached its peak in the late 8th century BC under another, historical, king Midas, who dominated most of western and central Anatolia and rivaled Assyria and Urartu for power in eastern Anatolia. This later Midas was, however, also the last independent king of Phrygia before Cimmerians sacked the Phrygian capital, Gordium, around 695 BC. Phrygia then became subject to Lydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

, and then successively to Persia, Alexander and his Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

successors, Pergamon, the Roman Empire and the Byzantine Empire. Over this time Phrygians became Christian and Greek-speaking, assimilating into the Byzantine state; after the Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

conquest of Byzantine Anatolia in the late Middle Ages, the name "Phrygia" passed out of usage as a territorial designation.

Geography

Gordion

Gordion ( Phrygian: ; el, Γόρδιον, translit=Górdion; tr, Gordion or ; la, Gordium) was the capital city of ancient Phrygia. It was located at the site of modern Yassıhüyük, about southwest of Ankara (capital of Turkey), in the ...

. The climate is harsh with hot summers and cold winters. Therefore, olives will not easily grow here so the land is mostly used for livestock grazing and barley production.

Yazılıkaya, Eskişehir

Yazılıkaya (lit. 'inscribed rock'), Phrygian Yazılıkaya, or Midas Kenti (Midas city) is a village in Eskişehir Province, Turkey, located about 27 km south of Seyitgazi, 66 km south of Eskişehir, and 51 km north of Afyonkarahis ...

), is situated in an area of hills and columns of volcanic tuff. To the south again, central Phrygia includes the cities of Afyonkarahisar (ancient Akroinon) with its marble quarries at nearby Docimium (İscehisar), and the town of Synnada

Synnada ( gr, τὰ Σύνναδα) was an ancient town of Phrygia Salutaris in Asia Minor. Its site is now occupied by the modern Turkish town of Şuhut, in Afyonkarahisar Province.

Situation

Synnada was situated in the south-eastern part of ...

. At the western end of Phrygia stood the towns of Aizanoi (modern Çavdarhisar

Çavdarhisar is a town and district of Kütahya Province in the Aegean region of Turkey. According to 2000 census, population of the district is 13,538 of which 4,687 live in the town of Çavdarhisar. The local Kocaçay stream is still crossed by ...

) and Acmonia. From here to the southwest lies the hilly area of Phrygia that contrasts to the bare plains of the region's heartland.

Southwestern Phrygia is watered by the Maeander ( Büyük Menderes River) and its tributary the Lycus, and contains the towns of Laodicea on the Lycus and Hierapolis

Hierapolis (; grc, Ἱεράπολις, lit. "Holy City") was originally a Phrygian cult centre of the Anatolian mother goddess of Cybele and later a Greek city. Its location was centred upon the remarkable and copious hot springs in classica ...

.Peter Thonemann (ed), 2013, ''Roman Phrygia: culture and society'', Cambridge University Press

Origins

Legendary ancient migrations

According to ancient tradition among Greek historians, the Phrygians anciently migrated to Anatolia from the Balkans. Herodotus says that the Phrygians were called Bryges when they lived in Europe.Herodotus VII.73. He and other Greek writers also recorded legends about King Midas that associated him with or put his origin inMacedonia

Macedonia most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a traditional geographic reg ...

; Herodotus, for example, says a wild rose garden in Macedonia was named after Midas.

Some classical writers also connected the Phrygians with the Mygdones, the name of two groups of people, one of which lived in northern Macedonia and another in Mysia. Likewise, the Phrygians

The Phrygians (Greek: Φρύγες, ''Phruges'' or ''Phryges'') were an ancient Indo-European speaking people, who inhabited central-western Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) in antiquity. They were related to the Greeks.

Ancient Greek authors used ...

have been identified with the Bebryces, a people said to have warred with Mysia before the Trojan War and who had a king named Mygdon In Greek mythology, Mygdon (Ancient Greek: Μύγδων) may refer to the following personages:

* Mygdon, son of Ares and muse Calliope, eponymous of Mygdones

* Mygdon of Bebryces, killed by Heracles, son of Poseidon.

* Mygdon of Phrygia, king w ...

at roughly the same time as the Phrygians were said to have had a king named Mygdon.

The classical historian Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

groups Phrygians, Mygdones, Mysians, Bebryces and Bithynians

The Bithyni (; el, Βιθυνοί) were a Thracian tribe who, along with the Thyni, migrated to Anatolia. Herodotus, Xenophon and Strabo all assert that the Bithyni and Thyni settled together in what would be known as Bithynia and Thynia. Accord ...

together as peoples that migrated to Anatolia from the Balkans. This image of Phrygians as part of a related group of northwest Anatolian cultures seems the most likely explanation for the confusion over whether Phrygians

The Phrygians (Greek: Φρύγες, ''Phruges'' or ''Phryges'') were an ancient Indo-European speaking people, who inhabited central-western Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) in antiquity. They were related to the Greeks.

Ancient Greek authors used ...

, Bebryces and Anatolian Mygdones were or were not the same people.

Phrygian language

Phrygian continued to be spoken until the 6th century AD, though its distinctive alphabet was lost earlier than those of most Anatolian cultures. One of the Homeric Hymns describes the Phrygian language as not mutually intelligible with that of Troy, Homeric Hymns number 5, ''To Aphrodite''. and inscriptions found at Gordium make clear that Phrygians spoke anIndo-European language

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch ...

with at least some vocabulary similar to Greek. Phrygian clearly did not belong to the family of Anatolian languages

The Anatolian languages are an extinct branch of Indo-European languages that were spoken in Anatolia, part of present-day Turkey. The best known Anatolian language is Hittite, which is considered the earliest-attested Indo-European language.

...

spoken in most of the adjacent countries, such as Hittite. The apparent similarity of the Phrygian language to Greek and its dissimilarity with the Anatolian languages

The Anatolian languages are an extinct branch of Indo-European languages that were spoken in Anatolia, part of present-day Turkey. The best known Anatolian language is Hittite, which is considered the earliest-attested Indo-European language.

...

spoken by most of their neighbors is also taken as support for a European origin of the Phrygians.

From what is available, it is evident that Phrygian shares important features with Greek and Armenian. Phrygian is part of the centum group of Indo-European languages. However, between the 19th and the first half of the 20th century Phrygian was mostly considered a satəm language, and thus closer to Armenian and Thracian, while today it is commonly considered to be a centum language and thus closer to Greek. The reason that in the past Phrygian had the guise of a satəm language was due to two secondary processes that affected it. Namely, Phrygian merged the old labiovelar with the plain velar, and secondly, when in contact with palatal vowels /e/ and /i/, especially in initial position, some consonants became palatalized. Furthermore, Kortlandt (1988) presented common sound changes of Thracian and Armenian and their separation from Phrygian and the rest of the palaeo-Balkan languages

The Paleo-Balkan languages or Palaeo-Balkan languages is a grouping of various extinct Indo-European languages that were spoken in the Balkans and surrounding areas in ancient times.

Paleo-Balkan studies are obscured by the scarce attestation of ...

from an early stage.

Modern consensus regards Greek as the closest relative of Phrygian, a position that is supported by Brixhe, Neumann, Matzinger, Woodhouse, Ligorio, Lubotsky, and Obrador-Cursach. Furthermore, 34 out of the 36 Phrygian isoglosses that are recorded are shared with Greek, with 22 being exclusive between them. The last 50 years of Phrygian scholarship developed a hypothesis that proposes a proto-Graeco-Phrygian stage out of which Greek and Phrygian originated, and if Phrygian was more sufficiently attested, that stage could perhaps be reconstructed.

Recent migration hypotheses

Some scholars dismiss the claim of a Phrygian migration as a mere legend, likely arising from the coincidental similarity of their name to the Bryges, and have theorized that migration into Phrygia could have occurred more recently than classical sources suggest. They have sought to fit the Phrygian arrival into a narrative explaining the downfall of the Hittite Empire and the end of the high Bronze Age in Anatolia,. According to the "recent migration" theory, the Phrygians invaded just before or after the collapse of the Hittite Empire at the beginning of the 12th century BC, filling the political vacuum in central-western Anatolia, and may have been counted among the " Sea Peoples" that Egyptian records credit with bringing about the Hittite collapse. The so-called Handmade Knobbed Ware found in Western Anatolia during this period has been tentatively identified as an import connected to this invasion.Relation to their Hittite predecessors

Some scholars accept as factual the '' Iliads account that the Phrygians were established on theSakarya River

The Sakarya (Sakara River, tr, Sakarya Irmağı; gr, Σαγγάριος, translit=Sangarios; Latin: ''Sangarius'') is the third longest river in Turkey. It runs through the region known in ancient times as Phrygia. It was considered one of th ...

before the Trojan War, and thus must have been there during the later stages of the Hittite Empire, and probably earlier, and consequently dismiss proposals of recent immigration to Phrygia. These scholars seek instead to trace the Phrygians' origins among the many nations of western Anatolia who were subject to the Hittites. This interpretation also gets support from Greek legends about the founding of Phrygia's main city Gordium by Gordias and of Ancyra by Midas, which suggest that Gordium and Ancyra were believed to date from the distant past before the Trojan War.

No one has conclusively identified which of the many subjects of the Hittites might have represented early Phrygians. According to a classical tradition, popularized by Josephus, Phrygia can be equated with the country called Togarmah by the ancient Hebrews, which has in turn been identified as the Tegarama of Hittite texts and Til-Garimmu of Assyrian records. Josephus called Togarmah "the Thrugrammeans, who, as the Greeks resolved, were named Phrygians". However, the Greek source cited by Josephus is unknown, and it is unclear if there was any basis for the identification other than name similarity.

Scholars of the Hittites believe Tegarama was in eastern Anatolia – some locate it at Gurun – far to the east of Phrygia. Some scholars have identified Phrygia with the

No one has conclusively identified which of the many subjects of the Hittites might have represented early Phrygians. According to a classical tradition, popularized by Josephus, Phrygia can be equated with the country called Togarmah by the ancient Hebrews, which has in turn been identified as the Tegarama of Hittite texts and Til-Garimmu of Assyrian records. Josephus called Togarmah "the Thrugrammeans, who, as the Greeks resolved, were named Phrygians". However, the Greek source cited by Josephus is unknown, and it is unclear if there was any basis for the identification other than name similarity.

Scholars of the Hittites believe Tegarama was in eastern Anatolia – some locate it at Gurun – far to the east of Phrygia. Some scholars have identified Phrygia with the Assuwa Assuwa ( hit, 𒀸𒋗𒉿, translit=aš-šu-wa, link=yes; gmy, 𐀀𐀯𐀹𐀊, translit=a-si-wi-ja, link=yes) was a confederation of 22 states in western Anatolia around 1400 BC. The confederation formed to oppose the Hittite Empire, but was def ...

league, and noted that the '' Iliad'' mentions a Phrygian (Queen Hecuba's brother) named Asios. Another possible early name of Phrygia could be Hapalla, the name of the easternmost province that emerged from the splintering of the Bronze Age western Anatolian empire Arzawa. However, scholars are unsure if Hapalla corresponds to Phrygia or to Pisidia, further south.

Relation to Armenians

Ancient Greek historian Herodotus (writing circa 440 BCE), suggested that Armenians migrated from Phrygia, which at the time encompassed much of western and central Anatolia: "the Armenians were equipped like Phrygians, being Phrygian colonists" (7.73) (') According to Herotodus, the Phrygians had originated in the Balkans, in an area adjoining Macedonia, from where they had emigrated to Anatolia during the Bronze Age collapse. This led later scholars, such asIgor Diakonoff

Igor Mikhailovich Diakonoff (occasionally spelled Diakonov, russian: link=no, И́горь Миха́йлович Дья́конов; 12 January 1915 – 2 May 1999) was a Russian historian, linguist, and translator and a renowned expert on th ...

, to theorize that Armenians also originated in the Balkans and moved east with the Phrygians. However, an Armenian origin in the Balkans, although once widely accepted, has been facing increased scrutiny in recent years due to discrepancies in the timeline and lack of genetic and archeological evidence. In fact, some scholars have suggested that the Phrygians and/or the apparently related Mushki people were originally from Armenia and moved westward.

A number of linguists have rejected a close relationship between Armenian and Phrygian, despite saying that the two languages do share some features. Phrygian is now classified as a centum language more closely related to Greek than Armenian, whereas Armenian is mostly satem.

History

Around the time of the Trojan war

According to the Iliad, the homeland of the Phrygians was on the Sangarius River, which would remain the centre of Phrygia throughout its history. Phrygia was famous for its wine and had "brave and expert" horsemen. According to the Iliad, before the Trojan War, a young kingPriam

In Greek mythology, Priam (; grc-gre, Πρίαμος, ) was the legendary and last king of Troy during the Trojan War. He was the son of Laomedon. His many children included notable characters such as Hector, Paris, and Cassandra.

Etymology

Mo ...

of Troy had taken an army to Phrygia to support it in a war against the Amazons

In Greek mythology, the Amazons (Ancient Greek: Ἀμαζόνες ''Amazónes'', singular Ἀμαζών ''Amazōn'', via Latin ''Amāzon, -ŏnis'') are portrayed in a number of ancient epic poems and legends, such as the Labours of Hercules, ...

. Homer calls the Phrygians "the people of Otreus and godlike Mygdon In Greek mythology, Mygdon (Ancient Greek: Μύγδων) may refer to the following personages:

* Mygdon, son of Ares and muse Calliope, eponymous of Mygdones

* Mygdon of Bebryces, killed by Heracles, son of Poseidon.

* Mygdon of Phrygia, king w ...

". According to Euripides, Quintus Smyrnaeus

Quintus Smyrnaeus (also Quintus of Smyrna; el, Κόϊντος Σμυρναῖος, ''Kointos Smyrnaios'') was a Greek epic poet whose ''Posthomerica'', following "after Homer", continues the narration of the Trojan War. The dates of Quintus Smy ...

and others, this Mygdon's son, Coroebus

In Greek mythology, Coroebus (Ancient Greek: Κόροιβος) may refer to two distinct characters:

* Coroebus, son of King Mygdon of Phrygia is a character of Greek legend. He came to the aid of Troy during the Trojan War out of love for Princ ...

, fought and died in the Trojan War; he had sued for the hand of the Trojan princess Cassandra in marriage. The name ''Otreus'' could be an eponym for Otroea

''Otroea'' is a genus of longhorn beetles of the subfamily Lamiinae

Lamiinae, commonly called flat-faced longhorns, are a subfamily of the longhorn beetle family (Cerambycidae). The subfamily includes over 750 genera, rivaled in diversity wit ...

, a place on Lake Ascania in the vicinity of the later Nicaea, and the name ''Mygdon'' is clearly an eponym for the Mygdones, a people said by Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

to live in northwest Asia Minor, and who appear to have sometimes been considered distinct from the Phrygians

The Phrygians (Greek: Φρύγες, ''Phruges'' or ''Phryges'') were an ancient Indo-European speaking people, who inhabited central-western Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) in antiquity. They were related to the Greeks.

Ancient Greek authors used ...

. However, Pausanias believed that Mygdon's tomb was located at Stectorium in the southern Phrygian highlands, near modern Sandikli.

According to the '' Bibliotheca'', the Greek hero Heracles slew a king Mygdon of the Bebryces in a battle in northwest Anatolia that if historical would have taken place about a generation before the Trojan War. According to the story, while traveling from Minoa to the

According to the '' Bibliotheca'', the Greek hero Heracles slew a king Mygdon of the Bebryces in a battle in northwest Anatolia that if historical would have taken place about a generation before the Trojan War. According to the story, while traveling from Minoa to the Amazons

In Greek mythology, the Amazons (Ancient Greek: Ἀμαζόνες ''Amazónes'', singular Ἀμαζών ''Amazōn'', via Latin ''Amāzon, -ŏnis'') are portrayed in a number of ancient epic poems and legends, such as the Labours of Hercules, ...

, Heracles stopped in Mysia and supported the Mysians in a battle with the Bebryces. According to some interpretations, Bebryces is an alternate name for Phrygians and this Mygdon is the same person mentioned in the Iliad.

King Priam

In Greek mythology, Priam (; grc-gre, Πρίαμος, ) was the legendary and last king of Troy during the Trojan War. He was the son of Laomedon. His many children included notable characters such as Hector, Paris, and Cassandra.

Etymology

Mo ...

married the Phrygian princess Hecabe (or Hecuba) and maintained a close alliance with the Phrygians, who repaid him by fighting "ardently" in the Trojan War against the Greeks. Hecabe was a daughter of the Phrygian king Dymas, son of Eioneus In Greek mythology, Eioneus (Ancient Greek: Ἠιονεύς) is a name attributed to the following individuals:

*Eioneus, the Perrhaebi, Perrhaebian father of Dia (mythology), Dia, see Deioneus.

*Eioneus, son of Magnes (mythology), Magnes and Philo ...

, son of Proteus. According to the Iliad, Hecabe's younger brother Asius also fought at Troy (see above); and Quintus Smyrnaeus

Quintus Smyrnaeus (also Quintus of Smyrna; el, Κόϊντος Σμυρναῖος, ''Kointos Smyrnaios'') was a Greek epic poet whose ''Posthomerica'', following "after Homer", continues the narration of the Trojan War. The dates of Quintus Smy ...

mentions two grandsons of Dymas that fell at the hands of Neoptolemus at the end of the Trojan War: "Two sons he slew of Meges rich in gold, Scion of Dymas – sons of high renown, cunning to hurl the dart, to drive the steed in war, and deftly cast the lance afar, born at one birth beside Sangarius' banks of Periboea to him, Celtus one, and Eubius the other." Teleutas, father of the maiden Tecmessa, is mentioned as another mythical Phrygian king.

There are indications in the Iliad that the heart of the Phrygian country was further north and downriver than it would be in later history. The Phrygian contingent arrives to aid Troy coming from Lake Ascania in northwest Anatolia, and is led by Phorcys

In Greek mythology, Phorcys or Phorcus (; grc, Φόρκυς) is a primordial sea god, generally cited (first in Hesiod) as the son of Pontus and Gaia (Earth). Classical scholar Karl Kerenyi conflated Phorcys with the similar sea gods Nereus a ...

and Ascanius

Ascanius (; Ancient Greek: Ἀσκάνιος) (said to have reigned 1176-1138 BC) was a legendary king of Alba Longa and is the son of the Trojan hero Aeneas and Creusa, daughter of Priam. He is a character in Roman mythology, and has a divine ...

, both sons of Aretaon.

In one of the so-called Homeric Hymns, Phrygia is said to be "rich in fortresses" and ruled by "famous Otreus".

Peak and destruction of the Phrygian kingdom

During the 8th century BC, the Phrygian kingdom with its capital at Gordium in the upper

During the 8th century BC, the Phrygian kingdom with its capital at Gordium in the upper Sakarya River

The Sakarya (Sakara River, tr, Sakarya Irmağı; gr, Σαγγάριος, translit=Sangarios; Latin: ''Sangarius'') is the third longest river in Turkey. It runs through the region known in ancient times as Phrygia. It was considered one of th ...

valley expanded into an empire dominating most of central and western Anatolia and encroaching upon the larger Assyrian Empire to its southeast and the kingdom of Urartu to the northeast.

According to the classical historians Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

, Eusebius and Julius Africanus, the king of Phrygia during this time was another Midas. This historical Midas is believed to be the same person named as Mita in Assyrian texts from the period and identified as king of the Mushki. Scholars figure that Assyrians called Phrygians "Mushki" because the Phrygians and Mushki, an eastern Anatolian people, were at that time campaigning in a joint army. This Midas is thought to have reigned Phrygia at the peak of its power from about 720 BC to about 695 BC (according to Eusebius) or 676 BC (according to Julius Africanus). An Assyrian inscription mentioning "Mita", dated to 709 BC, during the reign of Sargon of Assyria, suggests Phrygia and Assyria had struck a truce by that time. This Midas appears to have had good relations and close trade ties with the Greeks, and reputedly married an Aeolian Greek princess.

A system of writing in the Phrygian language developed and flourished in Gordium during this period, using a Phoenician-derived alphabet similar to the Greek one. A distinctive Phrygian pottery called Polished Ware appears during this period.

However, the Phrygian Kingdom was then overwhelmed by Cimmerian invaders, and Gordium was sacked and destroyed. According to Strabo and others, Midas committed suicide by drinking bulls' blood.

A series of digs have opened Gordium as one of Turkey's most revealing archeological sites. Excavations confirm a violent destruction of Gordium around 675 BC. A tomb from the period, popularly identified as the "Tomb of Midas", revealed a wooden structure deeply buried under a vast tumulus, containing grave goods, a coffin, furniture, and food offerings (Archaeological Museum, Ankara).

A series of digs have opened Gordium as one of Turkey's most revealing archeological sites. Excavations confirm a violent destruction of Gordium around 675 BC. A tomb from the period, popularly identified as the "Tomb of Midas", revealed a wooden structure deeply buried under a vast tumulus, containing grave goods, a coffin, furniture, and food offerings (Archaeological Museum, Ankara).

As a Lydian province

After their destruction of Gordium, the Cimmerians remained in western Anatolia and warred withLydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

, which eventually expelled them by around 620 BC, and then expanded to incorporate Phrygia, which became the Lydian empire's eastern frontier. The Gordium site reveals a considerable building program during the 6th century BC, under the domination of Lydian kings including the proverbially rich King Croesus

Croesus ( ; Lydian: ; Phrygian: ; grc, Κροισος, Kroisos; Latin: ; reigned: c. 585 – c. 546 BC) was the king of Lydia, who reigned from 585 BC until his defeat by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 547 or 546 BC.

Croesus was ...

. Meanwhile, Phrygia's former eastern subjects fell to Assyria and later to the Medes.

There may be an echo of strife with Lydia and perhaps a veiled reference to royal hostages, in the legend of the twice-unlucky Phrygian prince Adrastus

In Greek mythology, Adrastus or Adrestus (Ancient Greek: Ἄδραστος or Ἄδρηστος), (perhaps meaning "the inescapable"), was a king of Argos, and leader of the Seven against Thebes. He was the son of the Argive king Talaus, but was ...

, who accidentally killed his brother and exiled himself to Lydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

, where King Croesus

Croesus ( ; Lydian: ; Phrygian: ; grc, Κροισος, Kroisos; Latin: ; reigned: c. 585 – c. 546 BC) was the king of Lydia, who reigned from 585 BC until his defeat by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 547 or 546 BC.

Croesus was ...

welcomed him. Once again, Adrastus accidentally killed Croesus' son and then committed suicide.

As Persian province(s)

Some time in the 540s BC, Phrygia passed to the Achaemenid (Great Persian) Empire when

Some time in the 540s BC, Phrygia passed to the Achaemenid (Great Persian) Empire when Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

conquered Lydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

.

After Darius the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

became Persian Emperor in 521 BC, he remade the ancient trade route into the Persian " Royal Road" and instituted administrative reforms that included setting up satrapies. The Phrygian satrapy

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with consid ...

(province) lay west of the Halys River (now Kızıl River

Kizil may refer to:

People

* Bahar Kizil (born 1988), German singer-songwriter

Places

* Kizil Caves, Buddhist rock-cut caves located near Kizil Township

* Kızıl Kule, main tourist attraction in the Turkish city of Alanya

* Kızılırmak River, ...

) and east of Mysia and Lydia. Its capital was established at Dascylium

Dascylium, Dascyleium, or Daskyleion ( grc, Δασκύλιον, Δασκυλεῖον), also known as Dascylus, was a town in Anatolia some inland from the coast of the Propontis, at modern Ergili, Turkey. Its site was rediscovered in 1952 and ...

, modern Ergili.

In the course of the 5th century, the region was divided in two administrative satrapies: Hellespontine Phrygia and Greater Phrygia.

Under Alexander and his successors

The Macedonian Greek conqueror Alexander the Great passed through Gordium in 333 BC and severed theGordian Knot

The Gordian Knot is an Ancient Greek legend of Phrygian Gordium associated with Alexander the Great who is said to have cut the knot in 333 BC. It is often used as a metaphor for an intractable problem (untying an impossibly tangled knot) sol ...

in the temple of Sabazios

Sabazios ( grc, Σαβάζιος, translit=Sabázios, ''Savázios''; alternatively, ''Sabadios'') is the horseman and sky father god of the Phrygians and Thracians. Though the Greeks interpreted Phrygian Sabazios as both Zeus and Dionysus, rep ...

(" Zeus"). According to a legend, possibly promulgated by Alexander's publicists, whoever untied the knot would be master of Asia. With Gordium sited on the Persian Royal Road

The Royal Road was an ancient highway reorganized and rebuilt by the Persian king Darius the Great (Darius I) of the first (Achaemenid) Persian Empire in the 5th century BC. Darius built the road to facilitate rapid communication on the western ...

that led through the heart of Anatolia, the prophecy had some geographical plausibility. With Alexander, Phrygia became part of the wider Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

world. Upon Alexander's death in 323 BC, the Battle of Ipsus

The Battle of Ipsus ( grc, Ἱψός) was fought between some of the Diadochi (the successors of Alexander the Great) in 301 BC near the town of Ipsus in Phrygia. Antigonus I Monophthalmus, the Macedonian ruler of large parts of Asia, and his so ...

took place in 301 BC.

Celts and Attalids

In the chaotic period after Alexander's death, northern Phrygia was overrun by Celts, eventually to become the province ofGalatia

Galatia (; grc, Γαλατία, ''Galatía'', "Gaul") was an ancient area in the highlands of central Anatolia, roughly corresponding to the provinces of Ankara and Eskişehir, in modern Turkey. Galatia was named after the Gauls from Thrace (c ...

. The former capital of Gordium was captured and destroyed by the Gauls soon afterwards and disappeared from history.

In 188 BC, the southern remnant of Phrygia came under the control of the Attalids of Pergamon. However, the Phrygian language survived, although now written in the Greek alphabet.

Under Rome and Byzantium

In 133 BC, the remnants of Phrygia passed to Rome. For purposes of provincial administration, the Romans maintained a divided Phrygia, attaching the northeastern part to the province of

In 133 BC, the remnants of Phrygia passed to Rome. For purposes of provincial administration, the Romans maintained a divided Phrygia, attaching the northeastern part to the province of Galatia

Galatia (; grc, Γαλατία, ''Galatía'', "Gaul") was an ancient area in the highlands of central Anatolia, roughly corresponding to the provinces of Ankara and Eskişehir, in modern Turkey. Galatia was named after the Gauls from Thrace (c ...

and the western portion to the province of Asia. There is some evidence that western Phrygia and Caria were separated from Asia in 254–259 to become the new province of Phrygia and Caria. During the reforms of Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

, Phrygia was divided anew into two provinces: "Phrygia I", or Phrygia Salutaris (meaning "healthy" in Latin), and Phrygia II, or Pacatiana (Greek Πακατιανή, "peaceful"), both under the Diocese of Asia. Salutaris with Synnada as its capital comprised the eastern portion of the region and Pacatiana with Laodicea on the Lycus as capital of the western portion. The provinces survived up to the end of the 7th century, when they were replaced by the Theme system

Theme or themes may refer to:

* Theme (arts), the unifying subject or idea of the type of visual work

* Theme (Byzantine district), an administrative district in the Byzantine Empire governed by a Strategos

* Theme (computing), a custom graphical ...

. In the Late Roman, early " Byzantine" period, most of Phrygia belonged to the Anatolic theme. It was overrun by the Turks in the aftermath of the Battle of Manzikert

The Battle of Manzikert or Malazgirt was fought between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Empire on 26 August 1071 near Manzikert, theme of Iberia (modern Malazgirt in Muş Province, Turkey). The decisive defeat of the Byzantine army and th ...

(1071). The Turks had taken complete control in the 13th century, but the ancient name of ''Phrygia'' remained in use until the last remnant of the Byzantine Empire was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1453.

Culture

The ruins of Gordion and Midas City prove that Phrygia had developed an advanced Bronze Age culture. This Phrygian culture interacted in a number of ways with Greek culture in various periods of history.

The "Great Mother", Cybele, as the Greeks and Romans knew her, was originally worshiped in the mountains of Phrygia, where she was known as "Mountain Mother". In her typical Phrygian form, she wears a long belted dress, a ''polos'' (a high cylindrical headdress), and a veil covering the whole body. The later version of Cybele was established by a pupil of Phidias, the sculptor

The ruins of Gordion and Midas City prove that Phrygia had developed an advanced Bronze Age culture. This Phrygian culture interacted in a number of ways with Greek culture in various periods of history.

The "Great Mother", Cybele, as the Greeks and Romans knew her, was originally worshiped in the mountains of Phrygia, where she was known as "Mountain Mother". In her typical Phrygian form, she wears a long belted dress, a ''polos'' (a high cylindrical headdress), and a veil covering the whole body. The later version of Cybele was established by a pupil of Phidias, the sculptor Agoracritus

Agoracritus (Greek ''Agorákritos''; fl. late 5th century BC) was a famous sculptor in ancient Greece.

Life

Agoracritus was born on the island of Paros, and was active from about Olympiad 85 to 88, that is, from about 436 to 424 BC.Pliny, ''Nat ...

, and became the image most widely adopted by Cybele's expanding following, both in the Aegean world and at Rome. It shows her humanized though still enthroned, her hand resting on an attendant lion and the other holding the ''tympanon

The hammered dulcimer (also called the hammer dulcimer) is a percussion-stringed instrument which consists of strings typically stretched over a trapezoidal resonant sound board. The hammered dulcimer is set before the musician, who in more trad ...

'', a circular frame drum, similar to a tambourine.

The Phrygians also venerated Sabazios

Sabazios ( grc, Σαβάζιος, translit=Sabázios, ''Savázios''; alternatively, ''Sabadios'') is the horseman and sky father god of the Phrygians and Thracians. Though the Greeks interpreted Phrygian Sabazios as both Zeus and Dionysus, rep ...

, the sky and father- god depicted on horseback. Although the Greeks associated Sabazios with Zeus, representations of him, even in Roman times, show him as a horseman god. His conflicts with the indigenous Mother Goddess, whose creature was the Lunar Bull

Cattle in religion and mythology, Cattle are prominent in some religions and mythologies. As such, numerous peoples throughout the world have at one point in time honored bulls as sacred. In the Sumerian religion, Marduk is the "bull of Utu". ...

, may be surmised in the way that Sabazios' horse places a hoof on the head of a bull, in a Roman relief at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Museum of Fine Arts (often abbreviated as MFA Boston or MFA) is an art museum in Boston, Massachusetts. It is the 20th-largest art museum in the world, measured by public gallery area. It contains 8,161 paintings and more than 450,000 works ...

.

The earliest traditions of Greek music derived from Phrygia, transmitted through the Greek colonies in Anatolia, and included the

The earliest traditions of Greek music derived from Phrygia, transmitted through the Greek colonies in Anatolia, and included the Phrygian mode

The Phrygian mode (pronounced ) can refer to three different musical modes: the ancient Greek ''tonos'' or ''harmonia,'' sometimes called Phrygian, formed on a particular set of octave species or scales; the Medieval Phrygian mode, and the modern ...

, which was considered to be the warlike mode in ancient Greek music. Phrygian Midas, the king of the "golden touch", was tutored in music by Orpheus himself, according to the myth. Another musical invention that came from Phrygia was the aulos

An ''aulos'' ( grc, αὐλός, plural , ''auloi'') or ''tibia'' (Latin) was an ancient Greek wind instrument, depicted often in art and also attested by archaeology.

Though ''aulos'' is often translated as "flute" or "double flute", it was usu ...

, a reed instrument with two pipes.

Marsyas, the satyr who first formed the instrument using the hollowed antler

Antlers are extensions of an animal's skull found in members of the Cervidae (deer) family. Antlers are a single structure composed of bone, cartilage, fibrous tissue, skin, nerves, and blood vessels. They are generally found only on male ...

of a stag

Deer or true deer are hoofed ruminant mammals forming the family Cervidae. The two main groups of deer are the Cervinae, including the muntjac, the elk (wapiti), the red deer, and the fallow deer; and the Capreolinae, including the reindeer ...

, was a Phrygian follower of Cybele. He unwisely competed in music with the Olympian

Olympian or Olympians may refer to:

Religion

* Twelve Olympians, the principal gods and goddesses in ancient Greek religion

* Olympian spirits, spirits mentioned in books of ceremonial magic

Fiction

* ''Percy Jackson & the Olympians'', fiction ...

Apollo and inevitably lost, whereupon Apollo flayed Marsyas alive and provocatively hung his skin on Cybele's own sacred tree, a pine. Phrygia was also the scene of another musical contest, between Apollo and Pan. Midas was either a judge or spectator, and said he preferred Pan's pipes to Apollo's lyre, and was given donkey's ears as a punishment. The two stories were often confused or conflated, as by Titian.

Classical Greek iconography identifies the Trojan Paris as non-Greek by his Phrygian cap, which was worn by Mithras and survived into modern imagery as the " Liberty cap" of the American and

Classical Greek iconography identifies the Trojan Paris as non-Greek by his Phrygian cap, which was worn by Mithras and survived into modern imagery as the " Liberty cap" of the American and French revolutionaries

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

.

The Phrygians spoke an Indo-European language

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch ...

. (''See Phrygian language.'') Although the Phrygians adopted the alphabet originated by the Phoenicians, only a few dozen inscriptions in the Phrygian language have been found, primarily funereal, and so much of what is thought to be known of Phrygia is second-hand information from Greek sources.

Mythic past

The name of the earliest known mythical king was Nannacus (aka Annacus). This king resided at Iconium, the most eastern city of the kingdom of Phrygia at that time; and after his death, at the age of 300 years, a great flood overwhelmed the country, as had been foretold by an ancient oracle. The next king mentioned in extant classical sources was called Manis or Masdes. According to Plutarch, because of his splendid exploits, great things were called "manic" in Phrygia. Thereafter, the kingdom of Phrygia seems to have become fragmented among various kings. One of the kings was Tantalus, who ruled over the north western region of Phrygia around Mount Sipylus. Tantalus was endlessly punished in Tartarus, because he allegedly killed his son Pelops and sacrificially offered him to the Olympians, a reference to the suppression of human sacrifice. Tantalus was also falsely accused of stealing from the lotteries he had invented. In the mythic age before the Trojan war, during a time of aninterregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

, Gordius (or Gordias), a Phrygian farmer, became king, fulfilling an oracular prophecy. The kingless Phrygians had turned for guidance to the oracle of Sabazios ("Zeus" to the Greeks) at Telmissus

Telmessos or Telmessus ( Hittite: 𒆪𒉿𒆷𒉺𒀸𒊭 ''Kuwalapašša'', Lycian: 𐊗𐊁𐊍𐊁𐊂𐊁𐊛𐊆 ''Telebehi'', grc, Τελμησσός), also Telmissus ( grc, Τελμισσός), later Anastasiopolis ( grc, Αναστ� ...

, in the part of Phrygia that later became part of Galatia

Galatia (; grc, Γαλατία, ''Galatía'', "Gaul") was an ancient area in the highlands of central Anatolia, roughly corresponding to the provinces of Ankara and Eskişehir, in modern Turkey. Galatia was named after the Gauls from Thrace (c ...

. They had been instructed by the oracle to acclaim as their king the first man who rode up to the god's temple in a cart. That man was Gordias (Gordios, Gordius), a farmer, who dedicated the ox-cart in question, tied to its shaft with the "Gordian Knot

The Gordian Knot is an Ancient Greek legend of Phrygian Gordium associated with Alexander the Great who is said to have cut the knot in 333 BC. It is often used as a metaphor for an intractable problem (untying an impossibly tangled knot) sol ...

". Gordias refounded a capital at Gordium in west central Anatolia, situated on the old trackway through the heart of Anatolia that became Darius

Darius may refer to:

Persian royalty

;Kings of the Achaemenid Empire

* Darius I (the Great, 550 to 487 BC)

* Darius II (423 to 404 BC)

* Darius III (Codomannus, 380 to 330 BC)

;Crown princes

* Darius (son of Xerxes I), crown prince of Persia, ma ...

's Persian "Royal Road" from Pessinus to Ancyra, and not far from the River Sangarius.

The Phrygians are associated in Greek mythology with the

The Phrygians are associated in Greek mythology with the Dactyl

Dactyl may refer to:

* Dactyl (mythology), a legendary being

* Dactyl (poetry), a metrical unit of verse

* Dactyl Foundation, an arts organization

* Finger, a part of the hand

* Dactylus, part of a decapod crustacean

* "-dactyl", a suffix used ...

s, minor gods credited with the invention of iron smelting, who in most versions of the legend lived at Mount Ida

In Greek mythology, two sacred mountains are called Mount Ida, the "Mountain of the Goddess": Mount Ida in Crete, and Mount Ida in the ancient Troad region of western Anatolia (in modern-day Turkey), which was also known as the '' Phrygian Ida'' ...

in Phrygia.

Gordias's son (adopted in some versions) was Midas. A large body of myths and legends surround this first king Midas. connecting him with a mythological tale concerning Attis. This shadowy figure resided at Pessinus and attempted to marry his daughter to the young Attis in spite of the opposition of his lover Agdestis and his mother, the goddess Cybele. When Agdestis and/or Cybele appear and cast madness upon the members of the wedding feast. Midas is said to have died in the ensuing chaos.

King Midas is said to have associated himself with Silenus and other satyrs and with Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Romans ...

, who granted him a "golden touch".

In one version of his story, Midas travels from Thrace accompanied by a band of his people to Asia Minor to wash away the taint of his unwelcome "golden touch" in the river Pactolus. Leaving the gold in the river's sands, Midas found himself in Phrygia, where he was adopted by the childless king Gordias and taken under the protection of Cybele. Acting as the visible representative of Cybele, and under her authority, it would seem, a Phrygian king could designate his successor.

The Phrygian Sibyl was the priestess presiding over the Apollonian oracle

The Apollonian and the Dionysian are philosophical and literary concepts represented by a duality between the figures of Apollo and Dionysus from Greek mythology. Its popularization is widely attributed to the work ''The Birth of Tragedy'' by Fri ...

at Phrygia.

According to Herodotus, the Egyptian pharaoh Psammetichus II

Psamtik II ( Ancient Egyptian: , pronounced ), known by the Graeco-Romans as Psammetichus or Psammeticus, was a king of the Saite-based Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt (595 BC – 589 BC). His prenomen, Nefer-Ib-Re, means "Beautiful s theHeart ...

had two children raised in isolation in order to find the original language. The children were reported to have uttered ''bekos'', which is Phrygian for "bread", so Psammetichus admitted that the Phrygians were a nation older than the Egyptians.

Christian period

Visitors from Phrygia were reported to have been among the crowds present in Jerusalem on the occasion ofPentecost

Pentecost (also called Whit Sunday, Whitsunday or Whitsun) is a Christianity, Christian holiday which takes place on the 50th day (the seventh Sunday) after Easter Sunday. It commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles in the Ne ...

as recorded in . In the Apostle Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

and his companion Silas travelled through Phrygia and the region of Galatia

Galatia (; grc, Γαλατία, ''Galatía'', "Gaul") was an ancient area in the highlands of central Anatolia, roughly corresponding to the provinces of Ankara and Eskişehir, in modern Turkey. Galatia was named after the Gauls from Thrace (c ...

proclaiming the Christian gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

. Their plans appear to have been to go to Asia but circumstances or guidance, "in ways which we are not told, by inner promptings, or by visions of the night, or by the inspired utterances of those among their converts who had received the gift of prophecy" prevented them from doing so and instead they travelled westwards towards the coast.

The Christian heresy known as Montanism, and still known in Orthodoxy

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Churc ...

as "the Phrygian heresy", arose in the unidentified village of Ardabau in the 2nd century AD, and was distinguished by ecstatic spirituality and women priests. Originally described as a rural movement, it is now thought to have been of urban origin like other Christian developments. The new Jerusalem its adherents founded in the village of Pepouza has now been identified in a remote valley that later held a monastery.

See also

* Ancient regions of Anatolia *Phrygians

The Phrygians (Greek: Φρύγες, ''Phruges'' or ''Phryges'') were an ancient Indo-European speaking people, who inhabited central-western Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) in antiquity. They were related to the Greeks.

Ancient Greek authors used ...

* Bryges

* Paleo-Balkan languages

The Paleo-Balkan languages or Palaeo-Balkan languages is a grouping of various extinct Indo-European languages that were spoken in the Balkans and surrounding areas in ancient times.

Paleo-Balkan studies are obscured by the scarce attestation of ...

* Phrygian cap

* Phrygian language

References

Bibliography

* * * * *External links

* * * * {{Authority control States and territories established in the 12th century BC States and territories disestablished in the 7th century BC Historical regions of Anatolia Pauline churches History of Ankara Province History of Afyonkarahisar Province History of Eskişehir Province Former kingdoms