Philolaus (mythology) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Philolaus (; grc, Φιλόλαος, ''Philólaos''; ) was a Greek

Various reports give the birthplace of Philolaus as either Croton,

Various reports give the birthplace of Philolaus as either Croton,

Additionally, Charles Peter Mason noted (p. 304):

Historians from the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', Chapter ''Philolaus' Book: Genuine Fragments and Testimonia'', noted the following:

Additionally, Charles Peter Mason noted (p. 304):

Historians from the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', Chapter ''Philolaus' Book: Genuine Fragments and Testimonia'', noted the following:

The Counter-Earth

''. Osirus, vol. 11. Saint Catherines Press, 1954. p. 267-294 Nearly two-thousand years later,

Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

and pre-Socratic

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of thes ...

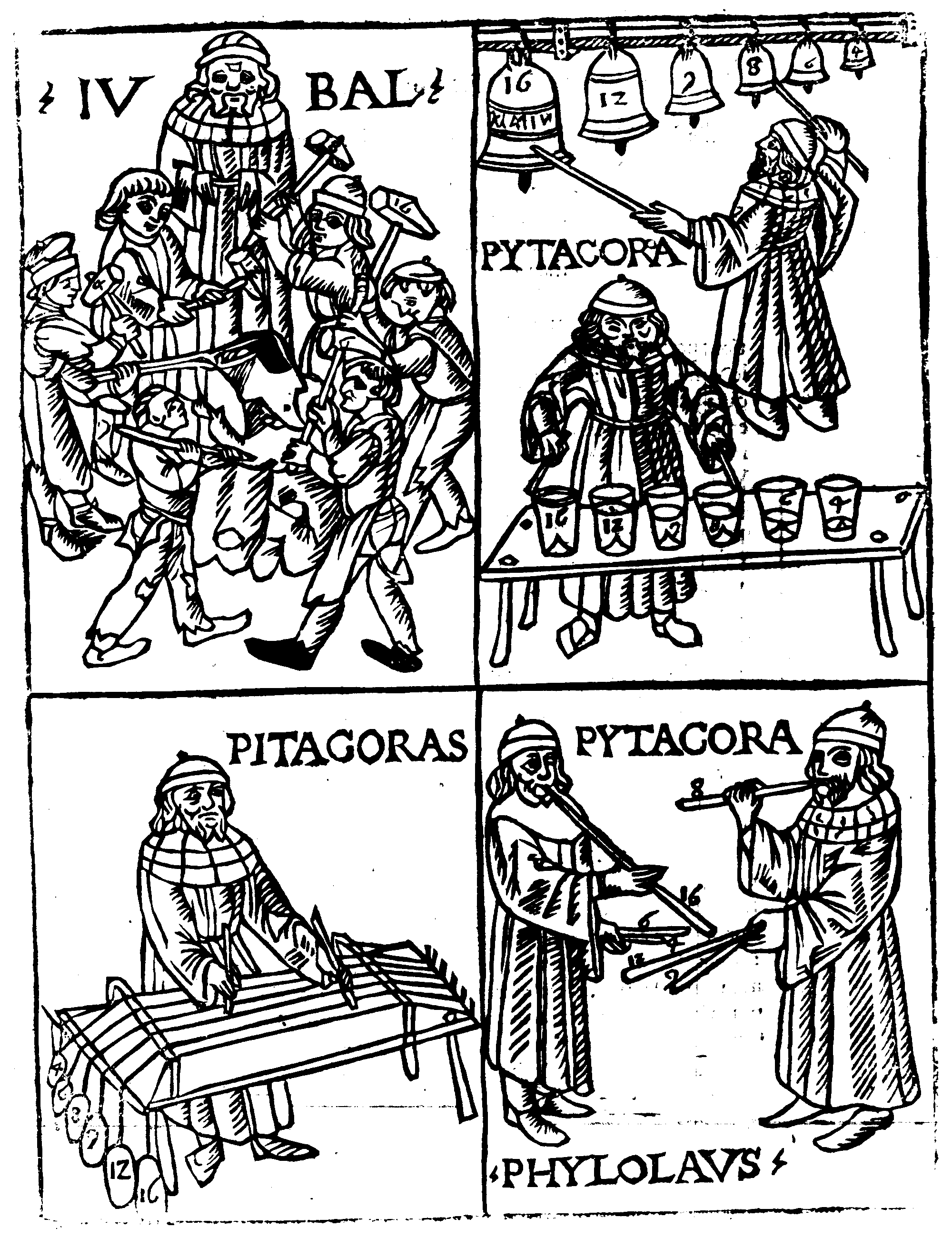

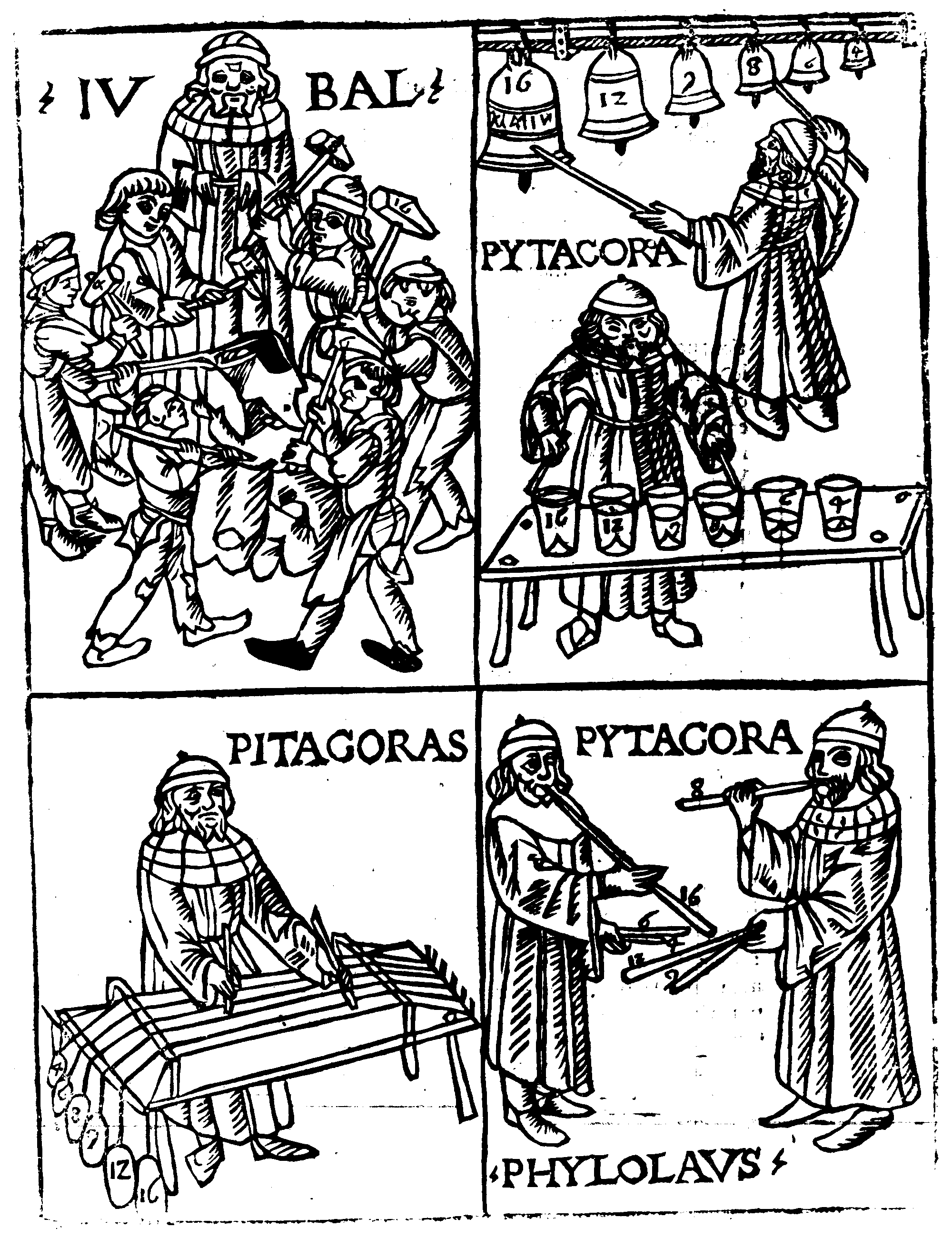

philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pythagorean tradition and the most outstanding figure in the Pythagorean school. Pythagoras developed a school of philosophy that was dominated by both mathematics and mysticism. Most of what is known today about the Pythagorean astronomical system is derived from Philolaus's views. He may have been the first to write about Pythagorean doctrine. According to August Böckh (1819), who cites Nicomachus

Nicomachus of Gerasa ( grc-gre, Νικόμαχος; c. 60 – c. 120 AD) was an important ancient mathematician and music theorist, best known for his works ''Introduction to Arithmetic'' and ''Manual of Harmonics'' in Greek. He was born in ...

, Philolaus was the successor of Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His politi ...

.

He argued that at the foundation of everything is the part played by the limiting and limitless, which combine in a harmony. With his assertions that the Earth was not the center of the universe (geocentrism

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, a ...

), he is credited with the earliest known discussion of concepts in the development of heliocentrism, the theory that the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

is not the center of the Universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. ...

, but rather that the Sun is. Philolaus discussed a Central Fire An astronomical system positing that the Earth, Moon, Sun, and planets revolve around an unseen "Central Fire" was developed in the fifth century BC and has been attributed to the Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus. The system has been called "the ...

as the center of the universe and that spheres (including the Sun) revolved around it.

Biography

Various reports give the birthplace of Philolaus as either Croton,

Various reports give the birthplace of Philolaus as either Croton, Tarentum Tarentum may refer to:

* Taranto, Apulia, Italy, on the site of the ancient Roman city of Tarentum (formerly the Greek colony of Taras)

**See also History of Taranto

* Tarentum (Campus Martius), also Terentum, an area in or on the edge of the Camp ...

, or Metapontum—all part of Magna Graecia (the name of the coastal areas of Southern Italy on the Tarentine Gulf that were colonized

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

extensively by Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

settlers). It is most likely that he came from Croton. He migrated to Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

, perhaps while fleeing the second burning of the Pythagorean meeting-place around 454 BC.

According to Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

's ''Phaedo

''Phædo'' or ''Phaedo'' (; el, Φαίδων, ''Phaidōn'' ), also known to ancient readers as ''On The Soul'', is one of the best-known dialogues of Plato's middle period, along with the '' Republic'' and the '' Symposium.'' The philosophica ...

'', he was the instructor of Simmias and Cebes Cebes of Thebes ( el, Κέβης Θηβαῖος, ''gen''.: Κέβητος; ''c''. 430 – 350 BCEDebra Nails, (2002), ''The people of Plato: a prosopography of Plato and other Socratics'', page 82.) was an Ancient Greek philosopher from Thebes rem ...

at Thebes, around the time the ''Phaedo'' takes place, in 399 BC. That would make him a contemporary of Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

, and would agree with the statement that Philolaus and Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

were contemporaries.

The writings of much later writers are the sources of further reports about his life. They are scattered and of dubious value in reconstructing his life. Apparently, he lived for some time at Heraclea, where he was the pupil of Aresas (perhaps Oresas), or (as Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

calls him) Arcesus. Diogenes Laërtius is the only authority for the claim that shortly after the death of Socrates, Plato traveled to Italy where he met with Philolaus and Eurytus

Eurytus, Eurytos (; Ancient Greek: Εὔρυτος) or Erytus (Ἔρυτος) is the name of several characters in Greek mythology, and of at least one historical figure.

Mythological

*Eurytus, one of the Giants, sons of Gaia, killed by Dionysus ...

. The pupils of Philolaus were said to have included Xenophilus

Xenophilus ( el, Ξενόφιλος; 4th century BC), of Chalcidice, was a Pythagorean philosopher and musician who lived in the first half of the 4th century BC. Aulus Gellius relates that Xenophilus was the intimate friend and teacher of Aristo ...

, Phanto, Echecrates In ancient Greece, Echecrates ( el, Ἐχεκράτης) was the name of the following men:

*Echecrates of Thessaly, a military officer of Ptolemy IV Philopator, documented around 219–217 BC.

*A son of Demetrius the Fair (c. 285–250 BC) by Olymp ...

, Diocles, and Polymnastus.

As to his death, Diogenes Laërtius reports a dubious story that Philolaus was put to death at Croton on account of being suspected of wanting to be the tyrant; a story which Diogenes Laërtius even chose to put into verse.

Writings

In one source, Diogenes Laërtius speaks of Philolaus composing one book,Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 85 but elsewhere he speaks of three books, as do Aulus Gellius and Iamblichus. It might have been one treatise divided into three books. Plato is said to have procured a copy of his book. Later, it was claimed that Plato composed much of his ''Timaeus Timaeus (or Timaios) is a Greek name. It may refer to:

* ''Timaeus'' (dialogue), a Socratic dialogue by Plato

*Timaeus of Locri, 5th-century BC Pythagorean philosopher, appearing in Plato's dialogue

*Timaeus (historian) (c. 345 BC-c. 250 BC), Greek ...

'' based upon the book by Philolaus.

One of the works of Philolaus was called ''On Nature''. It seems to be the same work that Stobaeus

Joannes Stobaeus (; grc-gre, Ἰωάννης ὁ Στοβαῖος; fl. 5th-century AD), from Stobi in Macedonia, was the compiler of a valuable series of extracts from Greek authors. The work was originally divided into two volumes containin ...

calls ''On the World'' and from which he has preserved a series of passages. Other writers refer to a work entitled ''Bacchae'', which may have been another name for the same work, and which may originate from Arignote

Arignote or Arignota (; grc-gre, Ἀριγνώτη, ''Arignṓtē''; fl. c. ) was a Pythagorean philosopher from Croton or Samos. She was known as a student of Pythagoras and TheanoSuda, ''Arignote'' and, according to some traditions, their dau ...

. However, it has been mentioned that Proclus describes the ''Bacchae'' as a book for teaching theology by means of mathematics.

According to Charles Peter Mason in Sir William Smith's ''Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology

The ''Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology'' (1849, originally published 1844 under a slightly different title) is an encyclopedia/biographical dictionary. Edited by William Smith, the dictionary spans three volumes and 3,700 ...

'' (1870, p. 305):

Additionally, Charles Peter Mason noted (p. 304):

Historians from the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', Chapter ''Philolaus' Book: Genuine Fragments and Testimonia'', noted the following:

Additionally, Charles Peter Mason noted (p. 304):

Historians from the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', Chapter ''Philolaus' Book: Genuine Fragments and Testimonia'', noted the following:

Cosmology

The book by Philolaus begins with the following: Robert Scoon explained Philolaus' universe in 1922:Stobaeus' account

According to Stobaeus, Philolaus did away with the ideas of fixed direction in space and developed one of the first non-geocentric views of the universe and in his new way of thinking, the universe revolved around ahypothetical astronomical object

Various unknown astronomical objects have been hypothesized throughout recorded history. For example, in the 5th century BCE, the philosopher Philolaus defined a hypothetical astronomical object which he called the "Central Fire", around which ...

he called the Central Fire An astronomical system positing that the Earth, Moon, Sun, and planets revolve around an unseen "Central Fire" was developed in the fifth century BC and has been attributed to the Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus. The system has been called "the ...

.

In Philolaus's system a sphere of the fixed stars, the five planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a you ...

s, the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

, Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

, and Earth, all moved around a Central Fire. According to Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

, writing in ''Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

'', Philolaus added a tenth unseen body, he called Counter-Earth

The Counter-Earth is a hypothetical body of the Solar System that orbits on the other side of the solar system from Earth.

A Counter-Earth or ''Antichthon'' ( el, Ἀντίχθων) was hypothesized by the pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Philol ...

, as without it there would be only nine revolving bodies, and the Pythagorean number theory

Number theory (or arithmetic or higher arithmetic in older usage) is a branch of pure mathematics devoted primarily to the study of the integers and integer-valued functions. German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) said, "Mat ...

required a tenth. However, Greek scholar George Burch asserts his belief that Aristotle was lampooning Philolaus's addition.

The system that Philolaus described predated the idea of spheres by hundreds of years, however.Burch, George Bosworth. The Counter-Earth

''. Osirus, vol. 11. Saint Catherines Press, 1954. p. 267-294 Nearly two-thousand years later,

Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated ...

would mention in ''De revolutionibus

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book ...

'' that Philolaus already knew about the Earth's revolution around a central fire.

It has been pointed out, however, that Stobaeus betrays a tendency to confound the dogmas of the early Ionian philosophers, and in his accounts, he occasionally mixes up Platonism with Pythagoreanism.

Philosophy

Philolaus argued at the foundation of everything is the part played by the ideas of limit and the unlimited. One of the first declarations in the work of Philolaus was that all things in the universe result from a combination of the unlimited and the limiting; for if all things had been unlimited, nothing could have been the object of knowledge.Fragment DK 44B 3 Limiters and unlimiteds are combined in a harmony (''harmonia''):See also

*Alcmaeon of Croton

Alcmaeon of Croton (; el, Ἀλκμαίων ὁ Κροτωνιάτης, ''Alkmaiōn'', ''gen''.: Ἀλκμαίωνος; fl. 5th century BC) was an early Greek medical writer and philosopher-scientist. He has been described as one of the most ...

*Apeiron

''Apeiron'' (; ) is a Greek word meaning "(that which is) unlimited," "boundless", "infinite", or "indefinite" from ''a-'', "without" and ''peirar'', "end, limit", "boundary", the Ionic Greek form of ''peras'', "end, limit, boundary".

Origin ...

*Nicomachus

Nicomachus of Gerasa ( grc-gre, Νικόμαχος; c. 60 – c. 120 AD) was an important ancient mathematician and music theorist, best known for his works ''Introduction to Arithmetic'' and ''Manual of Harmonics'' in Greek. He was born in ...

* Parmenides

* ''Protrepticus'' (Aristotle)

*Pythagoreans

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the ancient Greek colony of Kroton, ...

Notes

References

*External links

* * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Philolaus 5th-century BC philosophers Ancient Greek mathematicians Ancient Greek physicists Ancient Greek political refugees Ancient Thebes (Boeotia) Presocratic philosophers Pythagoreans Pythagoreans of Magna Graecia Ancient Crotonians 470s BC births 380s BC deaths 5th-century BC mathematicians 4th-century BC mathematicians