Petrarca Nuoto on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

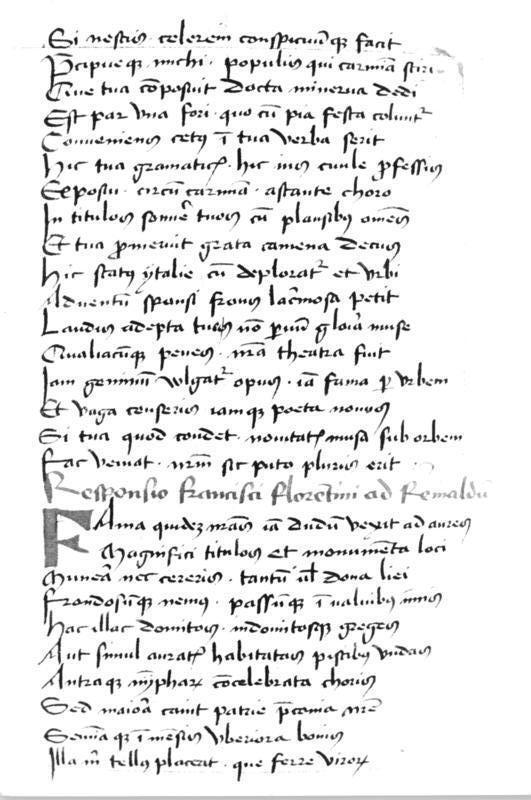

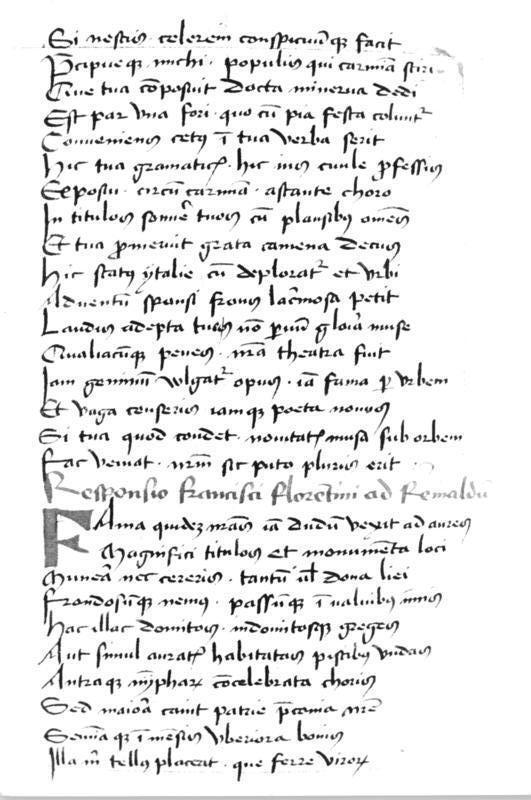

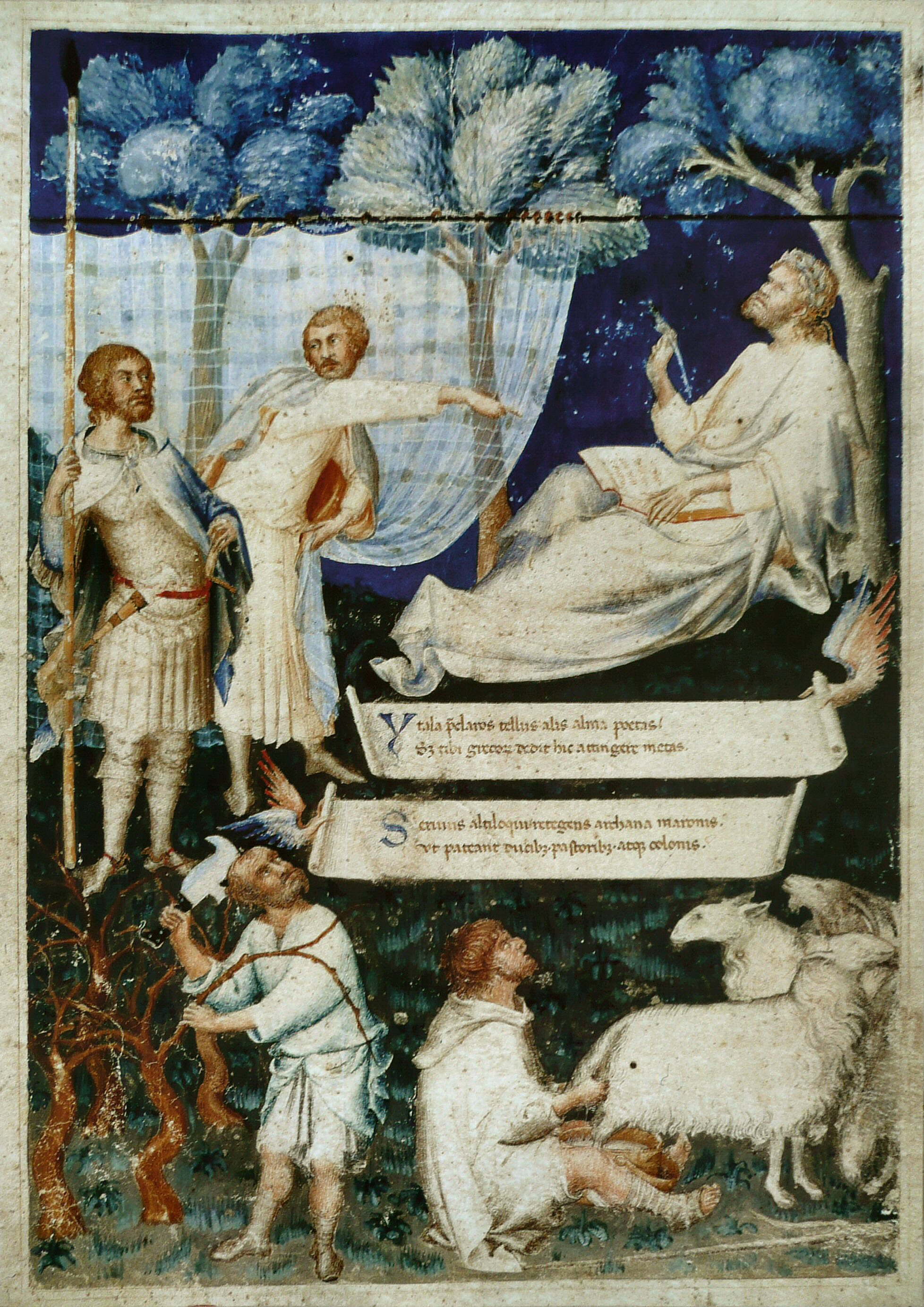

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

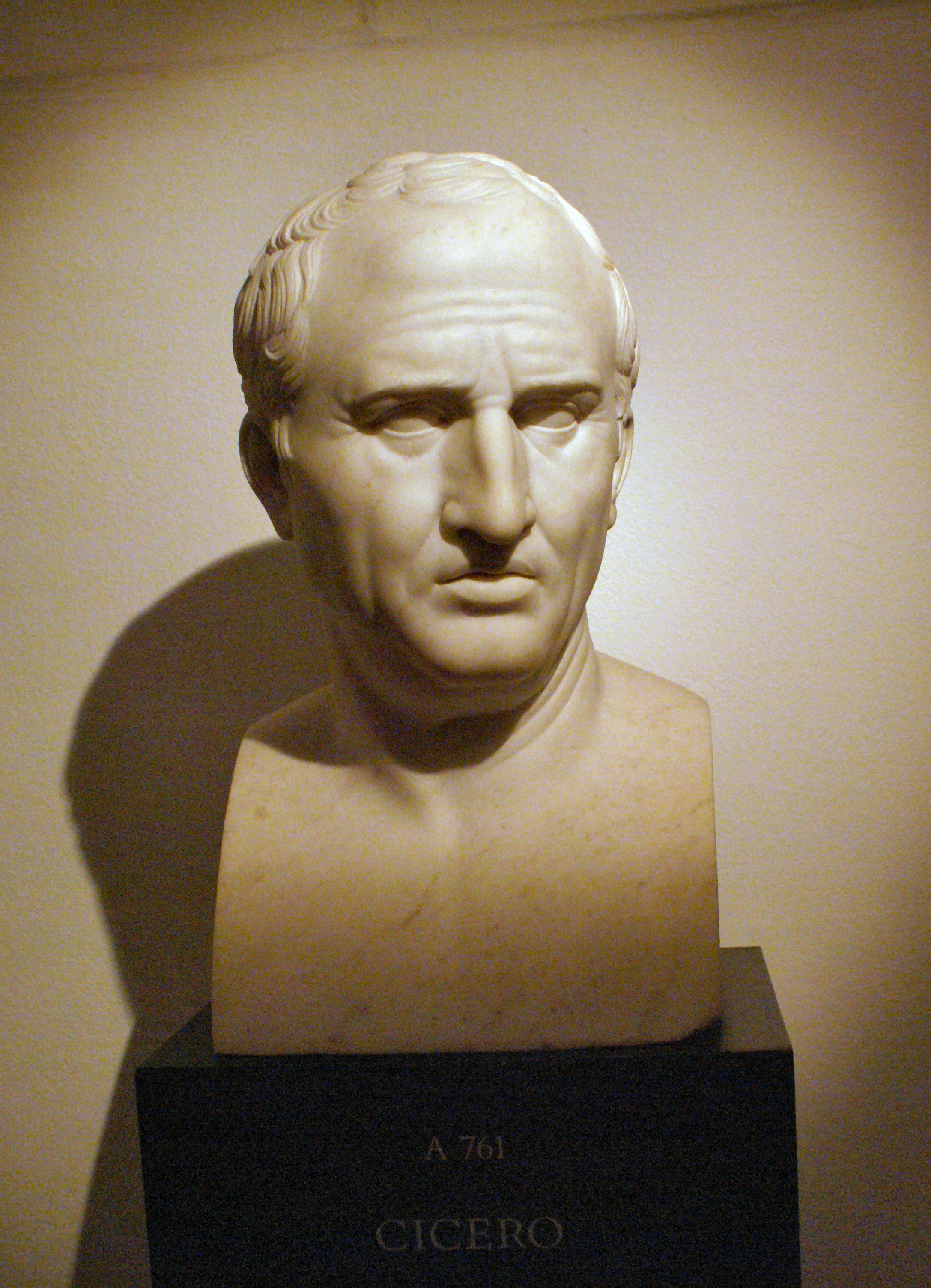

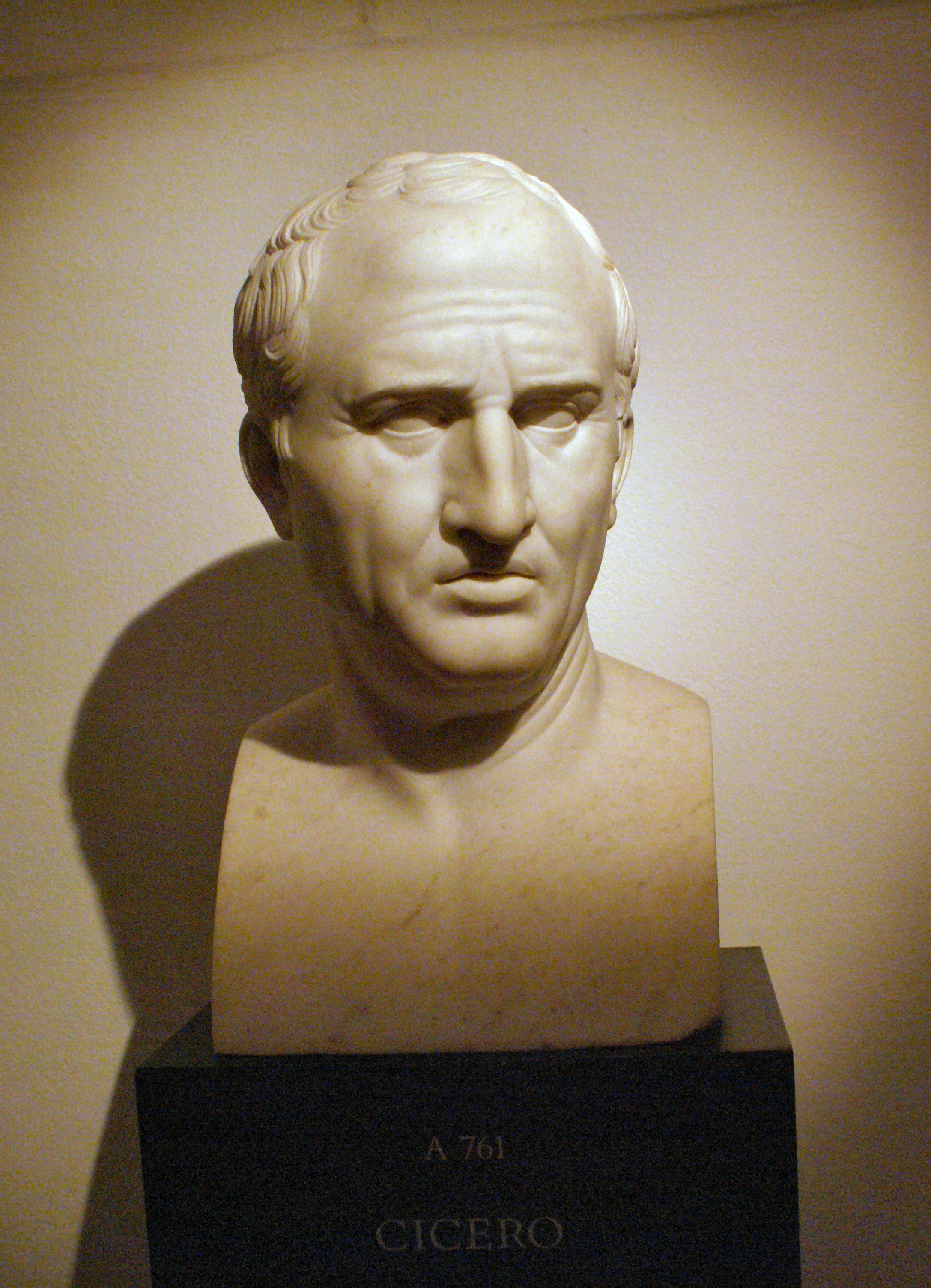

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited with initiating the 14th-century Italian Renaissance and the founding of Renaissance humanism. In the 16th century,

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited with initiating the 14th-century Italian Renaissance and the founding of Renaissance humanism. In the 16th century,

''Journal of the History of Ideas'', Vol. 4, No. 1. (Jan. 1943), pp. 69–74; Theodore E. Mommsen, "Petrarch's Conception of the 'Dark Ages'" ''Speculum'' 17.2 (April 1942: 226–242);

"Medieval Studies"

pp. 383–389.

Petrarch recounts that on 26 April 1336, with his brother and two servants, he climbed to the top of Mont Ventoux (), a feat which he undertook for recreation rather than necessity. The exploit is described in a celebrated letter addressed to his friend and confessor, the monk Dionigi di Borgo San Sepolcro, composed some time after the fact. In it, Petrarch claimed to have been inspired by Philip V of Macedon's ascent of Mount Haemo and that an aged peasant had told him that nobody had ascended Ventoux before or after himself, 50 years earlier, and warned him against attempting to do so. The nineteenth-century Swiss historian

Petrarch recounts that on 26 April 1336, with his brother and two servants, he climbed to the top of Mont Ventoux (), a feat which he undertook for recreation rather than necessity. The exploit is described in a celebrated letter addressed to his friend and confessor, the monk Dionigi di Borgo San Sepolcro, composed some time after the fact. In it, Petrarch claimed to have been inspired by Philip V of Macedon's ascent of Mount Haemo and that an aged peasant had told him that nobody had ascended Ventoux before or after himself, 50 years earlier, and warned him against attempting to do so. The nineteenth-century Swiss historian

translated by Morris Bishop, quoted in Plumb. to Dionigi displays a strikingly "modern" attitude of aesthetic gratification in the grandeur of the scenery and is still often cited in books and journals devoted to the sport of

Giovanni died of the plague in 1361. In the same year Petrarch was named canon in Monselice near Padua. Francesca married Francescuolo da Brossano (who was later named executor of Petrarch's

Giovanni died of the plague in 1361. In the same year Petrarch was named canon in Monselice near Padua. Francesca married Francescuolo da Brossano (who was later named executor of Petrarch's

Petrarch is best known for his Italian poetry, notably the '' Rerum vulgarium fragmenta'' ("Fragments of Vernacular Matters"), a collection of 366 lyric poems in various genres also known as 'canzoniere' ('songbook'), and ''I trionfi'' ("The Triumphs"), a six-part narrative poem of Dantean inspiration. However, Petrarch was an enthusiastic Latin scholar and did most of his writing in this language. His Latin writings include scholarly works, introspective essays, letters, and more poetry. Among them are ''

Petrarch is best known for his Italian poetry, notably the '' Rerum vulgarium fragmenta'' ("Fragments of Vernacular Matters"), a collection of 366 lyric poems in various genres also known as 'canzoniere' ('songbook'), and ''I trionfi'' ("The Triumphs"), a six-part narrative poem of Dantean inspiration. However, Petrarch was an enthusiastic Latin scholar and did most of his writing in this language. His Latin writings include scholarly works, introspective essays, letters, and more poetry. Among them are '' Petrarch also published many volumes of his letters, including a few written to his long-dead friends from history such as Cicero and Virgil. Cicero, Virgil, and Seneca were his literary models. Most of his Latin writings are difficult to find today, but several of his works are available in English translations. Several of his Latin works are scheduled to appear in the Harvard University Press series ''I Tatti''. It is difficult to assign any precise dates to his writings because he tended to revise them throughout his life.

Petrarch collected his letters into two major sets of books called ''

Petrarch also published many volumes of his letters, including a few written to his long-dead friends from history such as Cicero and Virgil. Cicero, Virgil, and Seneca were his literary models. Most of his Latin writings are difficult to find today, but several of his works are available in English translations. Several of his Latin works are scheduled to appear in the Harvard University Press series ''I Tatti''. It is difficult to assign any precise dates to his writings because he tended to revise them throughout his life.

Petrarch collected his letters into two major sets of books called ''

Letters on Familiar Matters

) and '' Seniles''

Letters of Old Age

), both of which are available in English translation. The plan for his letters was suggested to him by knowledge of Cicero's letters. These were published "without names" to protect the recipients, all of whom had close relationships to Petrarch. The recipients of these letters included

Pietro Bembo

Pietro Bembo, ( la, Petrus Bembus; 20 May 1470 – 18 January 1547) was an Italian scholar, poet, and literary theorist who also was a member of the Knights Hospitaller, and a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. As an intellectual of the It ...

created the model for the modern Italian language based on Petrarch's works, as well as those of Giovanni Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was somet ...

, and, to a lesser extent, Dante Alighieri. Petrarch was later endorsed as a model for Italian style by the Accademia della Crusca

The Accademia della Crusca (; "Academy of the Bran"), generally abbreviated as La Crusca, is a Florence-based society of scholars of Italian linguistics and philology. It is one of the most important research institutions of the Italian language ...

.

Petrarch's sonnets were admired and imitated throughout Europe during the Renaissance and became a model for lyrical poetry. He is also known for being the first to develop the concept of the " Dark Ages".Renaissance or Prenaissance''Journal of the History of Ideas'', Vol. 4, No. 1. (Jan. 1943), pp. 69–74; Theodore E. Mommsen, "Petrarch's Conception of the 'Dark Ages'" ''Speculum'' 17.2 (April 1942: 226–242);

JSTOR

JSTOR (; short for ''Journal Storage'') is a digital library founded in 1995 in New York City. Originally containing digitized back issues of academic journals, it now encompasses books and other primary sources as well as current issues of j ...

link to a collection of several letters in the same issue.

Biography

Youth and early career

Petrarch was born in the Tuscan city ofArezzo

Arezzo ( , , ) , also ; ett, 𐌀𐌓𐌉𐌕𐌉𐌌, Aritim. is a city and ''comune'' in Italy and the capital of the province of the same name located in Tuscany. Arezzo is about southeast of Florence at an elevation of above sea level. ...

on 20 July 1304. He was the son of Ser Petracco and his wife Eletta Canigiani. His given name was ''Francesco Petracco,'' which was Latinized to ''Petrarca.'' Petrarch's younger brother was born in Incisa in Val d'Arno in 1307. Dante Alighieri was a friend of his father.J.H. Plumb

Sir John (Jack) Harold Plumb (20 August 1911 – 21 October 2001) was a British historian, known for his books on British 18th-century history. He wrote over thirty books.

Biography

Plumb was born in Leicester on 20 August 1911. He was educat ...

, ''The Italian Renaissance'', 1961; Chapter XI by Morris Bishop "Petrarch", pp. 161–175; New York, American Heritage Publishing

''American Heritage'' is a magazine dedicated to covering the history of the United States for a mainstream readership. Until 2007, the magazine was published by Forbes.

,

Petrarch spent his early childhood in the village of Incisa, near Florence. He spent much of his early life at Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label=Provençal dialect, Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse Departments of France, department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region of So ...

and nearby Carpentras, where his family moved to follow Pope Clement V, who moved there in 1309 to begin the Avignon Papacy. Petrarch studied law at the University of Montpellier (1316–20) and Bologna (1320–23) with a lifelong friend and schoolmate, Guido Sette Guido Sette (1304–1367/68) was the archbishop of Genoa from 1358 until his death. He was a close friend of Petrarch.

Family and education

Sette was born in the Lunigiana in 1304, the same year as Petrarch, whose letters attest to their friendship ...

, future archbishop of Genoa. Because his father was in the legal profession (a notary), he insisted that Petrarch and his brother also study law. Petrarch, however, was primarily interested in writing and Latin literature and considered these seven years wasted. Additionally, he proclaimed that through legal manipulation his guardians robbed him of his small property inheritance in Florence, which only reinforced his dislike for the legal system. He protested, "I couldn't face making a merchandise of my mind", since he viewed the legal system as the art of selling justice.

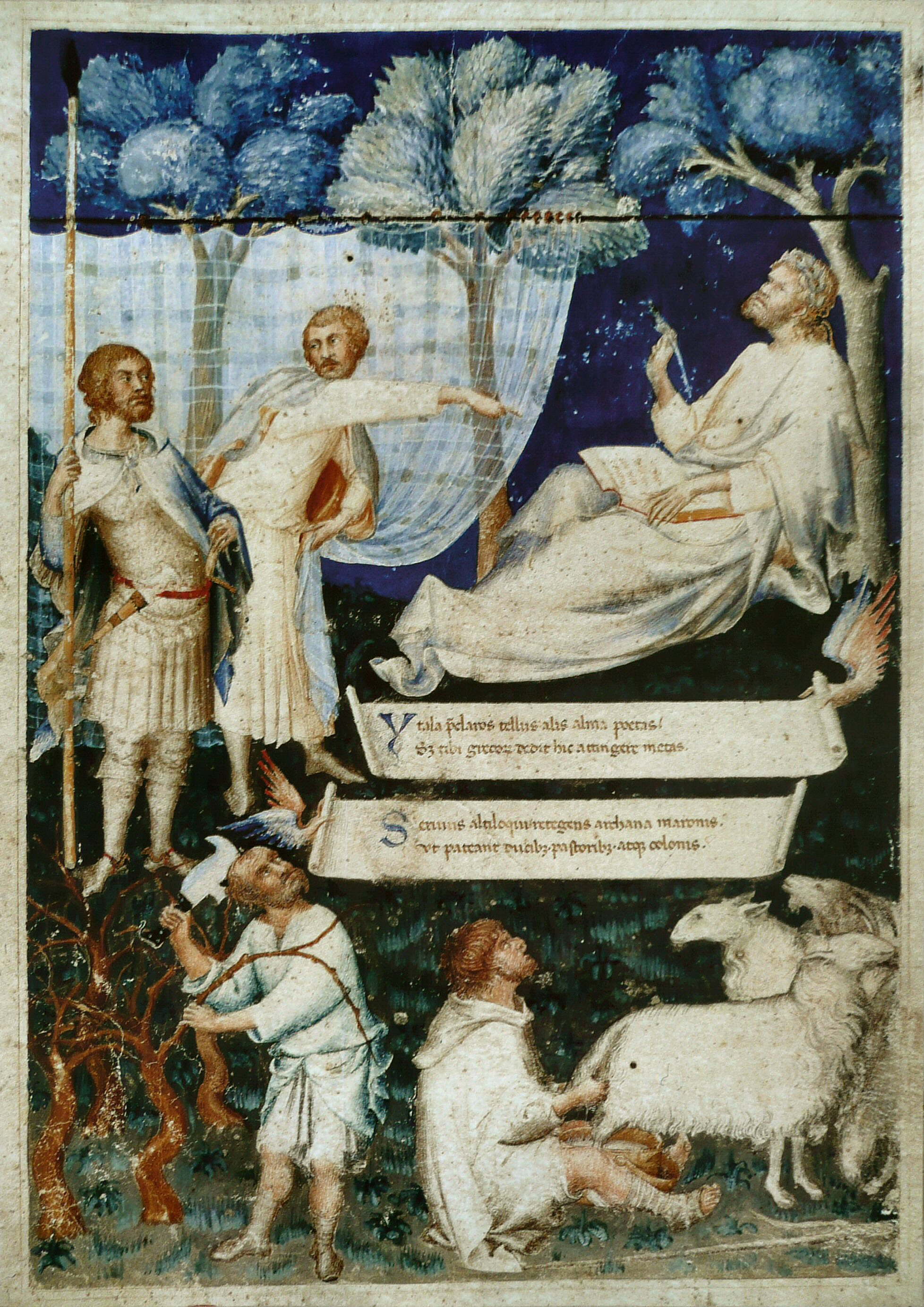

Petrarch was a prolific letter writer and counted Boccaccio among his notable friends to whom he wrote often. After the death of their parents, Petrarch and his brother Gherardo went back to Avignon in 1326, where he worked in numerous clerical offices. This work gave him much time to devote to his writing. With his first large-scale work, '' Africa'', an epic

Epic commonly refers to:

* Epic poetry, a long narrative poem celebrating heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation

* Epic film, a genre of film with heroic elements

Epic or EPIC may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and medi ...

in Latin about the great Roman general Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (, , ; 236/235–183 BC) was a Roman general and statesman, most notable as one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the best military com ...

, Petrarch emerged as a European celebrity. On 8 April 1341, he became the second poet laureate since classical antiquity and was crowned by Roman ''Senatori'' Giordano Orsini and Orso dell'Anguillara on the holy grounds of Rome's Capitol

The Capitolium or Capitoline Hill ( ; it, Campidoglio ; la, Mons Capitolinus ), between the Forum and the Campus Martius, is one of the Seven Hills of Rome.

The hill was earlier known as ''Mons Saturnius'', dedicated to the god Saturn. Th ...

.Pietrangeli (1981), p. 32

He traveled widely in Europe, served as an ambassador, and, because he traveled for pleasure, as with his ascent of Mont Ventoux, has been called "the first tourist".

During his travels, he collected crumbling Latin manuscripts

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in ...

and was a prime mover in the recovery of knowledge from writers of Rome and Greece. He encouraged and advised Leontius Pilatus

Leontius Pilatus (Greek: Λεόντιος Πιλάτος, Leontios Pilatos, Italian: Leonzio Pilato; died 1366) was an Italian scholar from Calabria and was one of the earliest promoters of Greek studies in Western Europe. Leontius translated and c ...

's translation of Homer from a manuscript purchased by Boccaccio, although he was severely critical of the result. Petrarch had acquired a copy, which he did not entrust to Leontius, but he knew no Greek; Petrarch said of himself, "Homer was dumb to him, while he was deaf to Homer". In 1345 he personally discovered a collection of Cicero's letters not previously known to have existed, the collection '' Epistulae ad Atticum'', in the Chapter Library (''Biblioteca Capitolare'') of Verona Cathedral.

Disdaining what he believed to be the ignorance of the era in which he lived, Petrarch is credited with creating the concept of a historical " Dark Ages", which most modern scholars now find inaccurate and misleading.; Same volume, Freedman, Paul"Medieval Studies"

pp. 383–389.

Mount Ventoux

Petrarch recounts that on 26 April 1336, with his brother and two servants, he climbed to the top of Mont Ventoux (), a feat which he undertook for recreation rather than necessity. The exploit is described in a celebrated letter addressed to his friend and confessor, the monk Dionigi di Borgo San Sepolcro, composed some time after the fact. In it, Petrarch claimed to have been inspired by Philip V of Macedon's ascent of Mount Haemo and that an aged peasant had told him that nobody had ascended Ventoux before or after himself, 50 years earlier, and warned him against attempting to do so. The nineteenth-century Swiss historian

Petrarch recounts that on 26 April 1336, with his brother and two servants, he climbed to the top of Mont Ventoux (), a feat which he undertook for recreation rather than necessity. The exploit is described in a celebrated letter addressed to his friend and confessor, the monk Dionigi di Borgo San Sepolcro, composed some time after the fact. In it, Petrarch claimed to have been inspired by Philip V of Macedon's ascent of Mount Haemo and that an aged peasant had told him that nobody had ascended Ventoux before or after himself, 50 years earlier, and warned him against attempting to do so. The nineteenth-century Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt

Carl Jacob Christoph Burckhardt (25 May 1818 – 8 August 1897) was a Swiss historian of art and culture and an influential figure in the historiography of both fields. He is known as one of the major progenitors of cultural history. Sigfri ...

noted that Jean Buridan had climbed the same mountain a few years before, and ascents accomplished during the Middle Ages have been recorded, including that of Anno II, Archbishop of Cologne.

Scholars note that Petrarch's letterFamiliares 4.1translated by Morris Bishop, quoted in Plumb. to Dionigi displays a strikingly "modern" attitude of aesthetic gratification in the grandeur of the scenery and is still often cited in books and journals devoted to the sport of

mountaineering

Mountaineering or alpinism, is a set of outdoor activities that involves ascending tall mountains. Mountaineering-related activities include traditional outdoor climbing, skiing, and traversing via ferratas. Indoor climbing, sport climbing, a ...

. In Petrarch, this attitude is coupled with an aspiration for a virtuous Christian life, and on reaching the summit, he took from his pocket a volume by his beloved mentor, Saint Augustine, that he always carried with him.

For pleasure alone he climbed Mont Ventoux, which rises to more than six thousand feet, beyond Vaucluse. It was no great feat, of course; but he was the first recorded Alpinist of modern times, the first to climb a mountain merely for the delight of looking from its top. (Or almost the first; for in a high pasture he met an old shepherd, who said that fifty years before he had attained the summit, and had got nothing from it save toil and repentance and torn clothing.) Petrarch was dazed and stirred by the view of the Alps, the mountains around Lyons, the Rhone, the Bay ofAs the book fell open, Petrarch's eyes were immediately drawn to the following words: Petrarch's response was to turn from the outer world of nature to the inner world of "soul": James Hillman argues that this rediscovery of the inner world is the real significance of the Ventoux event. The Renaissance begins not with the ascent of Mont Ventoux but with the subsequent descent—the "return ..to the valley of soul", as Hillman puts it. Arguing against such a singular and hyperbolic periodization, Paul James suggests a different reading:Marseilles Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc .... He took Augustine's '' Confessions'' from his pocket and reflected that his climb was merely anallegory As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a hidden meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory th ...of aspiration toward a better life.

Later years

Petrarch spent the later part of his life journeying through northern Italy as an international scholar and poet-diplomat. His career inthe Church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* Chris ...

did not allow him to marry, but he is believed to have fathered two children by a woman or women unknown to posterity. A son, Giovanni, was born in 1337, and a daughter, Francesca, was born in 1343. He later legitimized both.

Giovanni died of the plague in 1361. In the same year Petrarch was named canon in Monselice near Padua. Francesca married Francescuolo da Brossano (who was later named executor of Petrarch's

Giovanni died of the plague in 1361. In the same year Petrarch was named canon in Monselice near Padua. Francesca married Francescuolo da Brossano (who was later named executor of Petrarch's will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

) that same year. In 1362, shortly after the birth of a daughter, Eletta (the same name as Petrarch's mother), they joined Petrarch in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

to flee the plague then ravaging parts of Europe. A second grandchild, Francesco, was born in 1366, but died before his second birthday. Francesca and her family lived with Petrarch in Venice for five years from 1362 to 1367 at Palazzo Molina 250 px, Façade of Palace on Riva degli Schiavoni with the base of the Ponte del Sepolcro on left

Palazzo Mangiapane or Palace of Two Towers (Palazzo de Due Torri) or Palazzo Navager is a Gothic style palace located on the Riva degli Schiavoni #414 ...

; although Petrarch continued to travel in those years. Between 1361 and 1369 the younger Boccaccio paid the older Petrarch two visits. The first was in Venice, the second was in Padua.

About 1368 Petrarch and Francesca (with her family) moved to the small town of Arquà in the Euganean Hills

The Euganean Hills ( it, Colli Euganei ) are a group of hills of volcanic origin that rise to heights of 300 to 600 m from the Padovan-Venetian plain a few km south of Padua. The ''Colli Euganei'' form the first Regional park established in the V ...

near Padua, where he passed his remaining years in religious contemplation. He died in his house in Arquà on 18/19 July 1374. The house hosts now a permanent exhibition of Petrarchian works and curiosities, including the famous tomb of an embalmed cat long believed to be Petrarch's (although there is no evidence Petrarch actually had a cat). On the marble slab, there is a Latin inscription written by Antonio Quarenghi:

Petrarch's will (dated 4 April 1370) leaves 50 florins to Boccaccio "to buy a warm winter dressing gown"; various legacies (a horse, a silver cup, a lute, a Madonna

Madonna Louise Ciccone (; ; born August 16, 1958) is an American singer-songwriter and actress. Widely dubbed the " Queen of Pop", Madonna has been noted for her continual reinvention and versatility in music production, songwriting, a ...

) to his brother and his friends; his house in Vaucluse to its caretaker; for his soul, and for the poor; and the bulk of his estate to his son-in-law, Francescuolo da Brossano, who is to give half of it to "the person to whom, as he knows, I wish it to go"; presumably his daughter, Francesca, Brossano's wife. The will mentions neither the property in Arquà nor his library; Petrarch's library

The poet Petrarch arranged to leave his personal library to the city of Venice, but it never arrived. The Venetian tradition that this was the founding of the Biblioteca Marciana is an anachronism; it was founded a century later.

Petrarch's books ...

of notable manuscripts was already promised to Venice, in exchange for the Palazzo Molina. This arrangement was probably cancelled when he moved to Padua, the enemy of Venice, in 1368. The library was seized by the lords of Padua, and his books and manuscripts are now widely scattered over Europe. Nevertheless, the Biblioteca Marciana traditionally claimed this bequest as its founding, although it was in fact founded by Cardinal Bessarion in 1468.

Works

Petrarch is best known for his Italian poetry, notably the '' Rerum vulgarium fragmenta'' ("Fragments of Vernacular Matters"), a collection of 366 lyric poems in various genres also known as 'canzoniere' ('songbook'), and ''I trionfi'' ("The Triumphs"), a six-part narrative poem of Dantean inspiration. However, Petrarch was an enthusiastic Latin scholar and did most of his writing in this language. His Latin writings include scholarly works, introspective essays, letters, and more poetry. Among them are ''

Petrarch is best known for his Italian poetry, notably the '' Rerum vulgarium fragmenta'' ("Fragments of Vernacular Matters"), a collection of 366 lyric poems in various genres also known as 'canzoniere' ('songbook'), and ''I trionfi'' ("The Triumphs"), a six-part narrative poem of Dantean inspiration. However, Petrarch was an enthusiastic Latin scholar and did most of his writing in this language. His Latin writings include scholarly works, introspective essays, letters, and more poetry. Among them are ''Secretum Secretum may refer to:

*Secretum (book), a book by Petrarch

*, a book by Monaldi & Sorti

* Secretum (room) at the British Museum

*A ''sigillum secretum'', a special seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a divers ...

'' ("My Secret Book"), an intensely personal, imaginary dialogue with a figure inspired by Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

; ''De Viris Illustribus

''De Viris Illustribus'', meaning "concerning illustrious men", represents a genre of literature which evolved during the Italian Renaissance in imitation of the exemplary literature of Ancient Rome. It inspired the widespread commissioning of g ...

'' ("On Famous Men"), a series of moral biographies; ''Rerum Memorandarum Libri'', an incomplete treatise on the cardinal virtues; ''De Otio Religiosorum'' ("On Religious Leisure") and ''De vita solitaria

' ("Of Solitary Life" or "On the Solitary Life"; translated as ''The Life of Solitude'') is a philosophical treatise composed in Latin and written between 1346 and 1356 (mainly in Lent of 1346) by Italian Renaissance humanist Petrarch. It constit ...

'' ("On the Solitary Life"), which praise the contemplative life; ''De Remediis Utriusque Fortunae

''De remediis utriusque fortunae'' ("Remedies for Fortunes") is a collection of 254 Latin dialogues written by the humanist Francesco Petrarca (1304–1374), commonly known as Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374) ...

'' ("Remedies for Fortune Fair and Foul"), a self-help book which remained popular for hundreds of years; '' Itinerarium'' ("Petrarch's Guide to the Holy Land"); invectives against opponents such as doctors, scholastics, and the French; the ''Carmen Bucolicum'', a collection of 12 pastoral poems; and the unfinished epic '' Africa''. He translated seven psalms, a collection known as the '' Penitential Psalms''.

Petrarch also published many volumes of his letters, including a few written to his long-dead friends from history such as Cicero and Virgil. Cicero, Virgil, and Seneca were his literary models. Most of his Latin writings are difficult to find today, but several of his works are available in English translations. Several of his Latin works are scheduled to appear in the Harvard University Press series ''I Tatti''. It is difficult to assign any precise dates to his writings because he tended to revise them throughout his life.

Petrarch collected his letters into two major sets of books called ''

Petrarch also published many volumes of his letters, including a few written to his long-dead friends from history such as Cicero and Virgil. Cicero, Virgil, and Seneca were his literary models. Most of his Latin writings are difficult to find today, but several of his works are available in English translations. Several of his Latin works are scheduled to appear in the Harvard University Press series ''I Tatti''. It is difficult to assign any precise dates to his writings because he tended to revise them throughout his life.

Petrarch collected his letters into two major sets of books called ''Rerum familiarum liber Rerum may refer to :

*Lacrimae rerum is the Latin for tears for things.

*Rerum novarum is an encyclical issued by Pope Leo XIII on May 16, 1891.

*Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii was a Latin book by Baron Sigismund von Herberstein on the geography ...

'' Letters on Familiar Matters

) and '' Seniles''

Letters of Old Age

), both of which are available in English translation. The plan for his letters was suggested to him by knowledge of Cicero's letters. These were published "without names" to protect the recipients, all of whom had close relationships to Petrarch. The recipients of these letters included

Philippe de Cabassoles

Philippe de Cabassole or Philippe de Cabassoles (1305–1372), the Bishop of Cavaillon, Seigneur of Vaucluse, was the great protector of Renaissance poet Francesco Petrarch.

Early life

Philippe was educated by the clergy of Cavaillon and was m ...

, bishop of Cavaillon; Ildebrandino Conti

''Ildebrandino Conti'' was an Italian churchman and a member of the noble Roman family Conti.

Ildebrandino Conti was made bishop of Padua in 1319, by Pope John XXII, but he left the administration of the diocese to a vicar, staying in Avignon ...

, bishop of Padua

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Padua ( it, Diocesi di Padova; la, Dioecesis Patavina) is an episcopal see of the Catholic Church in Veneto, northern Italy. It was erected in the 3rd century.Cola di Rienzo, tribune of Rome;

autobiography

and a synopsis of his philosophy in life. It was originally written in Latin and was completed in 1371 or 1372—the first such autobiography in a thousand years (since Saint Augustine). While Petrarch's poetry was set to music frequently after his death, especially by Italian madrigal composers of the Renaissance in the 16th century, only one musical setting composed during Petrarch's lifetime survives. This is ''Non al suo amante'' by Jacopo da Bologna, written around 1350.

While it is possible she was an idealized or pseudonymous character—particularly since the name "Laura" has a linguistic connection to the poetic "laurels" Petrarch coveted—Petrarch himself always denied it. His frequent use of ''l'aura'' is also remarkable: for example, the line "Erano i capei d'oro a ''l'aura'' sparsi" may mean both "her hair was all over Laura's body" and "the wind (''l'aura'') blew through her hair". There is psychological realism in the description of Laura, although Petrarch draws heavily on conventionalised descriptions of love and lovers from troubadour songs and other literature of

While it is possible she was an idealized or pseudonymous character—particularly since the name "Laura" has a linguistic connection to the poetic "laurels" Petrarch coveted—Petrarch himself always denied it. His frequent use of ''l'aura'' is also remarkable: for example, the line "Erano i capei d'oro a ''l'aura'' sparsi" may mean both "her hair was all over Laura's body" and "the wind (''l'aura'') blew through her hair". There is psychological realism in the description of Laura, although Petrarch draws heavily on conventionalised descriptions of love and lovers from troubadour songs and other literature of

Petrarch is very different from Dante and his ''

Petrarch is very different from Dante and his ''

Petrarch is often referred to as the father of humanism and considered by many to be the "father of the Renaissance". In '' Secretum meum'', he points out that secular achievements do not necessarily preclude an authentic relationship with God, arguing instead that God has given humans their vast intellectual and creative potential to be used to its fullest. He inspired humanist philosophy, which led to the intellectual flowering of the Renaissance. He believed in the immense moral and practical value of the study of ancient history and literaturethat is, the study of human thought and action. Petrarch was a devout Catholic and did not see a conflict between realizing humanity's potential and having religious faith, although many philosophers and scholars have styled him a Proto-Protestant who challenged the Pope's dogma.

A highly introspective man, Petrarch helped shape the nascent humanist movement as many of the internal conflicts and musings expressed in his writings were embraced by Renaissance humanist philosophers and argued continually for the next 200 years. For example, he struggled with the proper relation between the active and contemplative life, and tended to emphasize the importance of solitude and study. In a clear disagreement with Dante, in 1346 Petrarch argued in ''

Petrarch is often referred to as the father of humanism and considered by many to be the "father of the Renaissance". In '' Secretum meum'', he points out that secular achievements do not necessarily preclude an authentic relationship with God, arguing instead that God has given humans their vast intellectual and creative potential to be used to its fullest. He inspired humanist philosophy, which led to the intellectual flowering of the Renaissance. He believed in the immense moral and practical value of the study of ancient history and literaturethat is, the study of human thought and action. Petrarch was a devout Catholic and did not see a conflict between realizing humanity's potential and having religious faith, although many philosophers and scholars have styled him a Proto-Protestant who challenged the Pope's dogma.

A highly introspective man, Petrarch helped shape the nascent humanist movement as many of the internal conflicts and musings expressed in his writings were embraced by Renaissance humanist philosophers and argued continually for the next 200 years. For example, he struggled with the proper relation between the active and contemplative life, and tended to emphasize the importance of solitude and study. In a clear disagreement with Dante, in 1346 Petrarch argued in ''

Petrarch's influence is evident in the works of

Petrarch's influence is evident in the works of

''Petrarch: His Life and Times''

Methuen. From Google Books * Kohl, Benjamin G. (1978). "Francesco Petrarch: Introduction; How a Ruler Ought to Govern His State," in ''The Earthly Republic: Italian Humanists on Government and Society'', ed. Benjamin G. Kohl and Ronald G. Witt, 25–78. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. * Nauert, Charles G. (2006). ''Humanism and the Culture of Renaissance Europe: Second Edition''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. * Rawski, Conrad H. (1991). ''Petrarch's Remedies for Fortune Fair and Foul'' A Modern English Translation of ''De remediis utriusque Fortune'', with a Commentary. * Robinson, James Harvey (1898)

''Petrarch, the First Modern Scholar and Man of Letters''

Harvard University * * A. Lee, ''Petrarch and St. Augustine: Classical Scholarship, Christian Theology and the Origins of the Renaissance in Italy'', Brill, Leiden, 2012, * N. Mann, ''Petrarca'' diz. orig. Oxford University Press (1984)– Ediz. ital. a cura di G. Alessio e L. Carlo Rossi – Premessa di G. Velli, LED Edizioni Universitarie, Milano, 1993, * ''Il Canzoniere» di Francesco Petrarca. La Critica Contemporanea'', G. Barbarisi e C. Berra (edd.), LED Edizioni Universitarie, Milano, 1992, * G. Baldassari, ''Unum in locum. Strategie macrotestuali nel Petrarca politico'', LED Edizioni Universitarie, Milano, 2006, * Francesco Petrarca, ''Rerum vulgarium Fragmenta. Edizione critica di Giuseppe Savoca'', Olschki, Firenze, 2008, * Plumb, J. H., ''The Italian Renaissance'', Houghton Mifflin, 2001, * Giuseppe Savoca, ''Il ''Canzoniere'' di Petrarca. Tra codicologia ed ecdotica'', Olschki, Firenze, 2008, * Roberta Antognini, ''Il progetto autobiografico delle "Familiares" di Petrarca'', LED Edizioni Universitarie, Milano, 2008, * Paul Geyer und Kerstin Thorwarth (hg), ''Petrarca und die Herausbildung des modernen Subjekts'' (Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2009) (Gründungsmythen Europas in Literatur, Musik und Kunst, 2) * Massimo Colella, ''«Cantin le ninfe co' soavi accenti». Per una definizione del petrarchismo di Veronica Gambara'', in «Testo», 2022.

Petrarch and his Cat Muse

from the '' Catholic Encyclopedia''

Excerpts from his works and letters

* * * *

translated by Tony Kline.

Francesco Petrarch

at ''The Online Library of Liberty'' * ''De remediis utriusque fortunae'', Cremonae, B. de Misintis ac Caesaris Parmensis, 1492. ( Vicifons) *

Petrarch and Laura

Multi-lingual site including translated works in the public domain and biography, pictures, music.

April 2004 article in ''The Guardian'' regarding the exhumation of Petrarch's remains

Oregon Petrarch Open Book

– A working database-driven hypertext in and around Francis Petrarch's Rerum Vulgarium Fragmenta (''Canzoniere'')

Historia Griseldis

From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the Library of Congress * Francesco Petrarch

''De viris illustribus''

digitized French codex, a

Somni

Petrarch's Vision of the Muslim and Byzantine East – Nancy Bisaha, Speculum, University of Chicago Press

{{DEFAULTSORT:Petrarch Italian Renaissance humanists Italian Renaissance writers 1304 births 1374 deaths Bibliophiles Book and manuscript collectors Christian humanists Italian male poets Italian Roman Catholics People from Arezzo Rhetoricians Roman Catholic writers Sonneteers 14th-century Italian historians 14th-century Italian poets 14th-century Italian writers 14th-century Latin writers Proto-Protestants

Francesco Nelli

Francesco Nelli (Florence – Naples, 1363) was the secretary of bishop Angelo Acciaioli I and a pastor at the Prior of the Church of the Holy Apostles in Florence. Nelli corresponded much with Francesco Petrarch as is evident by the fifty lette ...

, priest of the Prior of the Church of the Holy Apostles in Florence; and Niccolò di Capoccia Niccolò is an Italian male given name, derived from the Greek Nikolaos meaning "Victor of people" or "People's champion".

There are several male variations of the name: Nicolò, Niccolò, Nicolas, and Nicola. The female equivalent is Nicole. The fe ...

, a cardinal and priest of Saint Vitalis. His "Letter to Posterity" (the last letter in ''Seniles'') gives aautobiography

and a synopsis of his philosophy in life. It was originally written in Latin and was completed in 1371 or 1372—the first such autobiography in a thousand years (since Saint Augustine). While Petrarch's poetry was set to music frequently after his death, especially by Italian madrigal composers of the Renaissance in the 16th century, only one musical setting composed during Petrarch's lifetime survives. This is ''Non al suo amante'' by Jacopo da Bologna, written around 1350.

Laura and poetry

On 6 April 1327, after Petrarch gave up his vocation as a priest, the sight of a woman called "Laura" in the church of Sainte-Claire d'Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label=Provençal dialect, Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse Departments of France, department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region of So ...

awoke in him a lasting passion, celebrated in the ''Rerum vulgarium fragmenta'' ("Fragments of Vernacular Matters").

Laura may have been Laura de Noves, the wife of Count Hugues de Sade Hugues may refer to

People:

* Hugues de Payens (c. 1070–1136), French soldier

* Hugues I de Lusignan (1194/95 –1218), French-descended ruler a.k.a. Hugh I of Cyprus

* Hugues IV de Berzé (1150s–1220), French soldier

* Hugues II de Lusignan ...

(an ancestor of the Marquis de Sade

Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade (; 2 June 1740 – 2 December 1814), was a French nobleman, revolutionary politician, philosopher and writer famous for his literary depictions of a libertine sexuality as well as numerous accusat ...

). There is little definite information in Petrarch's work concerning Laura, except that she is lovely to look at, fair-haired, with a modest, dignified bearing. Laura and Petrarch had little or no personal contact. According to his "Secretum", she refused him because she was already married. He channeled his feelings into love poems that were exclamatory rather than persuasive, and wrote prose that showed his contempt for men who pursue women. Upon her death in 1348, the poet found that his grief

Grief is the response to loss, particularly to the loss of someone or some living thing that has died, to which a bond or affection was formed. Although conventionally focused on the emotional response to loss, grief also has physical, cogni ...

was as difficult to live with as was his former despair. Later, in his "Letter to Posterity", Petrarch wrote: "In my younger days I struggled constantly with an overwhelming but pure love affair—my only one, and I would have struggled with it longer had not premature death, bitter but salutary for me, extinguished the cooling flames. I certainly wish I could say that I have always been entirely free from desires of the flesh, but I would be lying if I did".

While it is possible she was an idealized or pseudonymous character—particularly since the name "Laura" has a linguistic connection to the poetic "laurels" Petrarch coveted—Petrarch himself always denied it. His frequent use of ''l'aura'' is also remarkable: for example, the line "Erano i capei d'oro a ''l'aura'' sparsi" may mean both "her hair was all over Laura's body" and "the wind (''l'aura'') blew through her hair". There is psychological realism in the description of Laura, although Petrarch draws heavily on conventionalised descriptions of love and lovers from troubadour songs and other literature of

While it is possible she was an idealized or pseudonymous character—particularly since the name "Laura" has a linguistic connection to the poetic "laurels" Petrarch coveted—Petrarch himself always denied it. His frequent use of ''l'aura'' is also remarkable: for example, the line "Erano i capei d'oro a ''l'aura'' sparsi" may mean both "her hair was all over Laura's body" and "the wind (''l'aura'') blew through her hair". There is psychological realism in the description of Laura, although Petrarch draws heavily on conventionalised descriptions of love and lovers from troubadour songs and other literature of courtly love

Courtly love ( oc, fin'amor ; french: amour courtois ) was a medieval European literary conception of love that emphasized nobility and chivalry. Medieval literature is filled with examples of knights setting out on adventures and performing vari ...

. Her presence causes him unspeakable joy, but his unrequited love creates unendurable desires, inner conflicts between the ardent lover and the mystic Christian, making it impossible to reconcile the two. Petrarch's quest for love leads to hopelessness and irreconcilable anguish, as he expresses in the series of paradoxes in Rima 134 "Pace non trovo, et non ò da far guerra;/e temo, et spero; et ardo, et son un ghiaccio": "I find no peace, and yet I make no war:/and fear, and hope: and burn, and I am ice".

Laura is unreachable and evanescent – descriptions of her are evocative yet fragmentary. Francesco de Sanctis praises the powerful music of his verse in his ''Storia della letteratura italiana''. Gianfranco Contini, in a famous essay ("Preliminari sulla lingua del Petrarca". Petrarca, Canzoniere. Turin, Einaudi, 1964), has described Petrarch's language in terms of "unilinguismo" (contrasted with Dantean "plurilinguismo").

Sonnet 227

Dante

Petrarch is very different from Dante and his ''

Petrarch is very different from Dante and his ''Divina Commedia

The ''Divine Comedy'' ( it, Divina Commedia ) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun 1308 and completed in around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and ...

''. In spite of the metaphysical subject, the ''Commedia'' is deeply rooted in the cultural and social milieu of turn-of-the-century Florence: Dante's rise to power (1300) and exile (1302); his political passions call for a "violent" use of language, where he uses all the registers, from low and trivial to sublime and philosophical. Petrarch confessed to Boccaccio that he had never read the ''Commedia'', remarks Contini, wondering whether this was true or Petrarch wanted to distance himself from Dante. Dante's language evolves as he grows old, from the courtly love of his early stilnovistic ''Rime'' and ''Vita nuova'' to the ''Convivio'' and ''Divina Commedia'', where Beatrice

Beatrice may refer to:

* Beatrice (given name)

Places In the United States

* Beatrice, Alabama, a town

* Beatrice, Humboldt County, California, a locality

* Beatrice, Georgia, an unincorporated community

* Beatrice, Indiana, an unincorporated ...

is sanctified as the goddess of philosophy—the philosophy announced by the Donna Gentile at the death of Beatrice.

In contrast, Petrarch's thought and style are relatively uniform throughout his life—he spent much of it revising the songs and sonnets of the ''Canzoniere

''Il Canzoniere'' (; en, Song Book), also known as the ''Rime Sparse'' ( en, Scattered Rhymes), but originally titled ' ( en, Fragments of common things, that is ''Fragments composed in vernacular''), is a collection of poems by the Italian hum ...

'' rather than moving to new subjects or poetry. Here, poetry alone provides a consolation for personal grief, much less philosophy or politics (as in Dante), for Petrarch fights within himself (sensuality versus mysticism, profane versus Christian literature), not against anything outside of himself. The strong moral and political convictions which had inspired Dante belong to the Middle Ages and the libertarian spirit of the commune; Petrarch's moral dilemmas, his refusal to take a stand in politics, his reclusive life point to a different direction, or time. The free commune, the place that had made Dante an eminent politician and scholar, was being dismantled: the ''signoria'' was taking its place. Humanism and its spirit of empirical inquiry, however, were making progress—but the papacy (especially after Avignon) and the empire ( Henry VII, the last hope of the white Guelphs, died near Siena in 1313) had lost much of their original prestige.

Petrarch polished and perfected the sonnet form inherited from Giacomo da Lentini and which Dante widely used in his ''Vita nuova

''La Vita Nuova'' (; Italian for "The New Life") or ''Vita Nova'' (Latin title) is a text by Dante Alighieri published in 1294. It is an expression of the medieval genre of courtly love in a prosimetrum style, a combination of both prose and ve ...

'' to popularise the new courtly love of the '' Dolce Stil Novo''. The tercet benefits from Dante's terza rima (compare the ''Divina Commedia''), the quatrain

A quatrain is a type of stanza, or a complete poem, consisting of four lines.

Existing in a variety of forms, the quatrain appears in poems from the poetic traditions of various ancient civilizations including Persia, Ancient India, Ancient Greec ...

s prefer the ABBA–ABBA to the ABAB–ABAB scheme of the Sicilians. The imperfect rhymes of ''u'' with closed ''o'' and ''i'' with closed ''e'' (inherited from Guittone's mistaken rendering of Sicilian verse) are excluded, but the rhyme of open and closed ''o'' is kept. Finally, Petrarch's enjambment creates longer semantic units by connecting one line to the following. The vast majority (317) of Petrarch's 366 poems collected in the ''Canzoniere'' (dedicated to Laura) were ''sonnets'', and the Petrarchan sonnet still bears his name.

Philosophy

Petrarch is often referred to as the father of humanism and considered by many to be the "father of the Renaissance". In '' Secretum meum'', he points out that secular achievements do not necessarily preclude an authentic relationship with God, arguing instead that God has given humans their vast intellectual and creative potential to be used to its fullest. He inspired humanist philosophy, which led to the intellectual flowering of the Renaissance. He believed in the immense moral and practical value of the study of ancient history and literaturethat is, the study of human thought and action. Petrarch was a devout Catholic and did not see a conflict between realizing humanity's potential and having religious faith, although many philosophers and scholars have styled him a Proto-Protestant who challenged the Pope's dogma.

A highly introspective man, Petrarch helped shape the nascent humanist movement as many of the internal conflicts and musings expressed in his writings were embraced by Renaissance humanist philosophers and argued continually for the next 200 years. For example, he struggled with the proper relation between the active and contemplative life, and tended to emphasize the importance of solitude and study. In a clear disagreement with Dante, in 1346 Petrarch argued in ''

Petrarch is often referred to as the father of humanism and considered by many to be the "father of the Renaissance". In '' Secretum meum'', he points out that secular achievements do not necessarily preclude an authentic relationship with God, arguing instead that God has given humans their vast intellectual and creative potential to be used to its fullest. He inspired humanist philosophy, which led to the intellectual flowering of the Renaissance. He believed in the immense moral and practical value of the study of ancient history and literaturethat is, the study of human thought and action. Petrarch was a devout Catholic and did not see a conflict between realizing humanity's potential and having religious faith, although many philosophers and scholars have styled him a Proto-Protestant who challenged the Pope's dogma.

A highly introspective man, Petrarch helped shape the nascent humanist movement as many of the internal conflicts and musings expressed in his writings were embraced by Renaissance humanist philosophers and argued continually for the next 200 years. For example, he struggled with the proper relation between the active and contemplative life, and tended to emphasize the importance of solitude and study. In a clear disagreement with Dante, in 1346 Petrarch argued in ''De vita solitaria

' ("Of Solitary Life" or "On the Solitary Life"; translated as ''The Life of Solitude'') is a philosophical treatise composed in Latin and written between 1346 and 1356 (mainly in Lent of 1346) by Italian Renaissance humanist Petrarch. It constit ...

'' that Pope Celestine V

Pope Celestine V ( la, Caelestinus V; 1215 – 19 May 1296), born Pietro Angelerio (according to some sources ''Angelario'', ''Angelieri'', ''Angelliero'', or ''Angeleri''), also known as Pietro da Morrone, Peter of Morrone, and Peter Celes ...

's refusal of the papacy in 1294 was a virtuous example of solitary life. Later the politician and thinker Leonardo Bruni (1370–1444) argued for the active life, or "civic humanism

Classical republicanism, also known as civic republicanism or civic humanism, is a form of republicanism developed in the Renaissance inspired by the governmental forms and writings of classical antiquity, especially such classical writers as Ar ...

". As a result, a number of political, military, and religious leaders during the Renaissance were inculcated with the notion that their pursuit of personal fulfillment should be grounded in classical example and philosophical contemplation.

Legacy

Serafino Ciminelli

The Italian poet and musician Serafino dell'Aquila or Aquilano is alternatively named Serafino dei Ciminelli from the family to which he belonged. He was born in what was then the Neapolitan town of L'Aquila on 6 January 1466 and died of a fever ...

from Aquila

Aquila may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Aquila'', a series of books by S.P. Somtow

* ''Aquila'', a 1997 book by Andrew Norriss

* ''Aquila'' (children's magazine), a UK-based children's magazine

* ''Aquila'' (journal), an or ...

(1466–1500) and in the works of Marin Držić (1508–1567) from Dubrovnik.

The Romantic

Romantic may refer to:

Genres and eras

* The Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement of the 18th and 19th centuries

** Romantic music, of that era

** Romantic poetry, of that era

** Romanticism in science, of that e ...

composer Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simpl ...

set three of Petrarch's Sonnets (47, 104, and 123) to music for voice, ''Tre sonetti del Petrarca'', which he later would transcribe for solo piano for inclusion in the suite '' Années de Pèlerinage''. Liszt also set a poem by Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

, "Oh! quand je dors" in which Petrarch and Laura are invoked as the epitome of erotic love.

While in Avignon in 1991, Modernist composer Elliott Carter completed his solo flute piece ''Scrivo in Vento'' which is in part inspired by and structured by Petrarch's Sonnet 212, ''Beato in sogno''. It was premiered on Petrarch's 687th birthday.

In November 2003, it was announced that pathological anatomists would be exhuming Petrarch's body from his casket in Arquà Petrarca

Arquà Petrarca () is a town and municipality (''comune'') in northeastern Italy, in the Veneto region, in the province of Padua. As of 2007 the estimated population of Arquà Petrarca was 1,835. The town is part of the association of the most bea ...

, to verify 19th-century reports that he had stood 1.83 meters (about six feet), which would have been tall for his period. The team from the University of Padua also hoped to reconstruct his cranium to generate a computerized image of his features to coincide with his 700th birthday. The tomb had been opened previously in 1873 by Professor Giovanni Canestrini, also of Padua University. When the tomb was opened, the skull was discovered in fragments and a DNA test revealed that the skull was not Petrarch's, prompting calls for the return of Petrarch's skull.

The researchers are fairly certain that the body in the tomb is Petrarch's due to the fact that the skeleton

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of an animal. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is the stable outer shell of an organism, the endoskeleton, which forms the support structure inside ...

bears evidence of injuries mentioned by Petrarch in his writings, including a kick from a donkey when he was 42.

Numismatics

He is credited with being the first and most famous aficionado of Numismatics. He described visiting Rome and asking peasants to bring him ancient coins they would find in the soil which he would buy from them, and writes of his delight at being able to identify the names and features of Roman emperors.Works in English translation

* Francesco Petrarch, ''Letters on Familiar Matters (Rerum familiarium libri),'' translated by Aldo S. Bernardo (New York: Italica Press, 2005). Volume 1, Books 1–8; Volume 2, Books 9–16; Volume 3, Books 17–24 * Francesco Petrarch, ''Letters of Old Age (Rerum senilium libri),'' translated by Aldo S. Bernardo, Saul Levin & Reta A. Bernardo (New York: Italica Press, 2005). Volume 1, Books 1–9; Volume 2, Books 10–18 * Francesco Petrarch, ''My Secret Book'', (''Secretum''), translated by Nicholas Mann. Harvard University Press * Francesco Petrarch, ''On Religious Leisure (De otio religioso),'' edited & translated by Susan S. Schearer, introduction by Ronald G. Witt (New York: Italica Press, 2002) * Francesco Petrarch, ''The Revolution of Cola di Rienzo,'' translated from Latin and edited by Mario E. Cosenza; 3rd, revised, edition by Ronald G. Musto (New York; Italica Press, 1996) * Francesco Petrarch, ''Selected Letters'', vol. 1 and 2, translated by Elaine Fantham. Harvard University Press *Francesco Petrarch, ''The Canzoniere, or Rerum vulgarium fragmenta,'' translated byMark Musa Mark Louis Musa (27 May 1934 – December 31, 2014) was a translator and scholar of Italian literature.

Musa was a graduate of Rutgers University (B.A., 1956), the University of Florence (as Fulbright Scholar of the U.S.-Italy Fulbright Commissio ...

, Indiana University Press, 1996,

See also

* OtiumNotes

References

* Bartlett, Kenneth R. (1992). ''The Civilization of the Italian Renaissance; a Source Book''. Lexington: D.C. Heath and Company. * Bishop, Morris (1961). "Petrarch." In J. H. Plumb (Ed.), ''Renaissance Profiles'', pp. 1–17. New York: Harper & Row. . * Hanawalt, A. Barbara (1998). ''The Middle Ages: An Illustrated History'' pp. 131–132 New York: Oxford University Press * * Kallendorf, Craig. "The Historical Petrarch," ''The American Historical Review'', Vol. 101, No. 1 (Feb. 1996): 130–141.Further reading

* Bernardo, Aldo (1983). "Petrarch." In '' Dictionary of the Middle Ages'', volume 9 * Celenza, Christopher S. (2017). ''Petrarch: Everywhere a Wanderer''. London: Reaktion. * Hennigfeld, Ursula (2008). ''Der ruinierte Körper. Petrarkistische Sonette in transkultureller Perspektive''. Würzburg, Königshausen & Neumann, 2008, * Hollway-Calthrop, Henry (1907)''Petrarch: His Life and Times''

Methuen. From Google Books * Kohl, Benjamin G. (1978). "Francesco Petrarch: Introduction; How a Ruler Ought to Govern His State," in ''The Earthly Republic: Italian Humanists on Government and Society'', ed. Benjamin G. Kohl and Ronald G. Witt, 25–78. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. * Nauert, Charles G. (2006). ''Humanism and the Culture of Renaissance Europe: Second Edition''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. * Rawski, Conrad H. (1991). ''Petrarch's Remedies for Fortune Fair and Foul'' A Modern English Translation of ''De remediis utriusque Fortune'', with a Commentary. * Robinson, James Harvey (1898)

''Petrarch, the First Modern Scholar and Man of Letters''

Harvard University * * A. Lee, ''Petrarch and St. Augustine: Classical Scholarship, Christian Theology and the Origins of the Renaissance in Italy'', Brill, Leiden, 2012, * N. Mann, ''Petrarca'' diz. orig. Oxford University Press (1984)– Ediz. ital. a cura di G. Alessio e L. Carlo Rossi – Premessa di G. Velli, LED Edizioni Universitarie, Milano, 1993, * ''Il Canzoniere» di Francesco Petrarca. La Critica Contemporanea'', G. Barbarisi e C. Berra (edd.), LED Edizioni Universitarie, Milano, 1992, * G. Baldassari, ''Unum in locum. Strategie macrotestuali nel Petrarca politico'', LED Edizioni Universitarie, Milano, 2006, * Francesco Petrarca, ''Rerum vulgarium Fragmenta. Edizione critica di Giuseppe Savoca'', Olschki, Firenze, 2008, * Plumb, J. H., ''The Italian Renaissance'', Houghton Mifflin, 2001, * Giuseppe Savoca, ''Il ''Canzoniere'' di Petrarca. Tra codicologia ed ecdotica'', Olschki, Firenze, 2008, * Roberta Antognini, ''Il progetto autobiografico delle "Familiares" di Petrarca'', LED Edizioni Universitarie, Milano, 2008, * Paul Geyer und Kerstin Thorwarth (hg), ''Petrarca und die Herausbildung des modernen Subjekts'' (Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2009) (Gründungsmythen Europas in Literatur, Musik und Kunst, 2) * Massimo Colella, ''«Cantin le ninfe co' soavi accenti». Per una definizione del petrarchismo di Veronica Gambara'', in «Testo», 2022.

External links

Petrarch and his Cat Muse

from the '' Catholic Encyclopedia''

Excerpts from his works and letters

* * * *

translated by Tony Kline.

Francesco Petrarch

at ''The Online Library of Liberty'' * ''De remediis utriusque fortunae'', Cremonae, B. de Misintis ac Caesaris Parmensis, 1492. ( Vicifons) *

Petrarch and Laura

Multi-lingual site including translated works in the public domain and biography, pictures, music.

April 2004 article in ''The Guardian'' regarding the exhumation of Petrarch's remains

Oregon Petrarch Open Book

– A working database-driven hypertext in and around Francis Petrarch's Rerum Vulgarium Fragmenta (''Canzoniere'')

Historia Griseldis

From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the Library of Congress * Francesco Petrarch

''De viris illustribus''

digitized French codex, a

Somni

Petrarch's Vision of the Muslim and Byzantine East – Nancy Bisaha, Speculum, University of Chicago Press

{{DEFAULTSORT:Petrarch Italian Renaissance humanists Italian Renaissance writers 1304 births 1374 deaths Bibliophiles Book and manuscript collectors Christian humanists Italian male poets Italian Roman Catholics People from Arezzo Rhetoricians Roman Catholic writers Sonneteers 14th-century Italian historians 14th-century Italian poets 14th-century Italian writers 14th-century Latin writers Proto-Protestants