Persianate societies on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A Persianate society is a society that is based on or strongly influenced by the

A Persianate society is a society that is based on or strongly influenced by the

A Persianate society is a society that is based on or strongly influenced by the

A Persianate society is a society that is based on or strongly influenced by the Persian language

Persian (), also known by its endonym Farsi (, ', ), is a Western Iranian language belonging to the Iranian branch of the Indo-Iranian subdivision of the Indo-European languages. Persian is a pluricentric language predominantly spoken and ...

, culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tyl ...

, literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

, art

Art is a diverse range of human activity, and resulting product, that involves creative or imaginative talent expressive of technical proficiency, beauty, emotional power, or conceptual ideas.

There is no generally agreed definition of wha ...

and/or identity.

The term "Persianate" is a neologism

A neologism Greek νέο- ''néo''(="new") and λόγος /''lógos'' meaning "speech, utterance"] is a relatively recent or isolated term, word, or phrase that may be in the process of entering common use, but that has not been fully accepted int ...

credited to Marshall Hodgson

Marshall Goodwin Simms Hodgson (April 11, 1922 – June 10, 1968), was an Islamic studies academic and a world historian at the University of Chicago. He was chairman of the interdisciplinary Committee on Social Thought in Chicago.

Works

Though he ...

. In his 1974 book, ''The Venture of Islam: The expansion of Islam in the Middle Periods'', he defined it thus: "The rise of Persian had more than purely literary consequences: it served to carry a new overall cultural orientation within Islamdom.... Most of the more local languages of high culture that later emerged among Muslims... depended upon Persian wholly or in part for their prime literary inspiration. We may call all these cultural traditions, carried in Persian or reflecting Persian inspiration, 'Persianate' by extension."Hodgson says, "It could even be said that Islamicate civilization, historically, is divisible in the more central areas into an earlier 'caliphal' and a later 'Persianate' phase; with variants in the outlying regions—Maghrib, Sudanic lands, Southern Seas, India,... (p. 294)"

The term designates ethnic Persians but also societies that may not have been predominantly ethnically Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

but whose linguistic, material or artistic cultural activities were influenced by or based on Persianate culture. Examples of pre-19th-century Persianate societies were the Seljuq Seljuk or Saljuq (سلجوق) may refer to:

* Seljuk Empire (1051–1153), a medieval empire in the Middle East and central Asia

* Seljuk dynasty (c. 950–1307), the ruling dynasty of the Seljuk Empire and subsequent polities

* Seljuk (warlord) (d ...

, Timurid Timurid refers to those descended from Timur (Tamerlane), a 14th-century conqueror:

* Timurid dynasty, a dynasty of Turco-Mongol lineage descended from Timur who established empires in Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent

** Timurid Empire of C ...

, Mughal, and Ottoman dynasties.

List of historical Persianate (or Persian-speaking) states/dynasties

Based in the

Iranian Plateau

The Iranian plateau or Persian plateau is a geological feature in Western Asia, Central Asia, and South Asia. It comprises part of the Eurasian Plate and is wedged between the Arabian Plate and the Indian Plate; situated between the Zagros ...

* Ghaznavids

The Ghaznavid dynasty ( fa, غزنویان ''Ġaznaviyān'') was a culturally Persianate, Sunni Muslim dynasty of Turkic ''mamluk'' origin, ruling, at its greatest extent, large parts of Persia, Khorasan, much of Transoxiana and the northwest ...

* Ghurid Empire

The Ghurid dynasty (also spelled Ghorids; fa, دودمان غوریان, translit=Dudmân-e Ğurīyân; self-designation: , ''Šansabānī'') was a Persianate dynasty and a clan of presumably eastern Iranian Tajik origin, which ruled from the ...

* Samanid Empire

The Samanid Empire ( fa, سامانیان, Sāmāniyān) also known as the Samanian Empire, Samanid dynasty, Samanid amirate, or simply as the Samanids) was a Persianate society, Persianate Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslim empire, of Iranian peoples, Ira ...

* Great Seljuq Empire

The Great Seljuk Empire, or the Seljuk Empire was a high medieval, culturally Turco-Persian tradition, Turko-Persian, Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslim empire, founded and ruled by the Qiniq (tribe), Qïnïq branch of Oghuz Turks. It spanned a total are ...

* Khwarazmian dynasty

The Anushtegin dynasty or Anushteginids (English: , fa, ), also known as the Khwarazmian dynasty ( fa, ) was a Persianate C. E. BosworthKhwarazmshahs i. Descendants of the line of Anuštigin In Encyclopaedia Iranica, online ed., 2009: ''"Li ...

* Ilkhanate

The Ilkhanate, also spelled Il-khanate ( fa, ایل خانان, ''Ilxānān''), known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (, ''Qulug-un Ulus''), was a khanate established from the southwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanid realm, ...

* Timurid Empire

The Timurid Empire ( chg, , fa, ), self-designated as Gurkani ( Chagatai: کورگن, ''Küregen''; fa, , ''Gūrkāniyān''), was a PersianateB.F. Manz, ''"Tīmūr Lang"'', in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Online Edition, 2006 Turco-Mongol empire ...

* Buyid dynasty

The Buyid dynasty ( fa, آل بویه, Āl-e Būya), also spelled Buwayhid ( ar, البويهية, Al-Buwayhiyyah), was a Shia Iranian dynasty of Daylamite origin, which mainly ruled over Iraq and central and southern Iran from 934 to 1062. Coupl ...

* Aq Qoyunlu

The Aq Qoyunlu ( az, Ağqoyunlular , ) was a culturally Persianate,Kaushik Roy, ''Military Transition in Early Modern Asia, 1400–1750'', (Bloomsbury, 2014), 38; "Post-Mongol Persia and Iraq were ruled by two tribal confederations: Akkoyunlu (Wh ...

* Kara Koyunlu

The Qara Qoyunlu or Kara Koyunlu ( az, Qaraqoyunlular , fa, قره قویونلو), also known as the Black Sheep Turkomans, were a culturally Persianate, Muslim Turkoman "Kara Koyunlu, also spelled Qara Qoyunlu, Turkish Karakoyunlular, En ...

* Shirvanshah

''Shirvanshah'' ( fa, شروانشاه), also spelled as ''Shīrwān Shāh'' or ''Sharwān Shāh'', was the title of the rulers of Shirvan from the mid-9th century to the early 16th century. The title remained in a single family, the Yazidids, a ...

* Safavid Empire

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often conside ...

* Afsharid dynasty

The Afsharid dynasty ( fa, افشاریان) was an Iranian

Iranian may refer to:

* Iran, a sovereign state

* Iranian peoples, the speakers of the Iranian languages. The term Iranic peoples is also used for this term to distinguish the pan eth ...

* Zand dynasty

The Zand dynasty ( fa, سلسله زندیه, ') was an Iranian dynasty, founded by Karim Khan Zand (1751–1779) that initially ruled southern and central Iran in the 18th century. It later quickly came to expand to include much of the rest of ...

* Qajar dynasty

The Qajar dynasty (; fa, دودمان قاجار ', az, Qacarlar ) was an IranianAbbas Amanat, ''The Pivot of the Universe: Nasir Al-Din Shah Qajar and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831–1896'', I. B. Tauris, pp 2–3 royal dynasty of Turkic peoples ...

Based in

Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

* Sultanate of Rum

fa, سلجوقیان روم ()

, status =

, government_type = Hereditary monarchyTriarchy (1249–1254)Diarchy (1257–1262)

, year_start = 1077

, year_end = 1308

, p1 = By ...

* Seljuk Empire

The Great Seljuk Empire, or the Seljuk Empire was a high medieval, culturally Turco-Persian tradition, Turko-Persian, Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslim empire, founded and ruled by the Qiniq (tribe), Qïnïq branch of Oghuz Turks. It spanned a total are ...

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

Based in the

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

* Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate was an Islamic empire based in Delhi that stretched over large parts of the Indian subcontinent for 320 years (1206–1526).

* Kashmir Sultanate

The history of Kashmir is intertwined with the history of the broader Indian subcontinent and the surrounding regions, comprising the areas of Central Asia, South Asia and East Asia. Historically, Kashmir referred to the Kashmir Valley. Today, ...

* Bengal Sultanate

The Sultanate of Bengal ( Middle Bengali: শাহী বাঙ্গালা ''Shahī Baṅgala'', Classical Persian: ''Saltanat-e-Bangālah'') was an empire based in Bengal for much of the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. It was the dominan ...

* Gujarat Sultanate

The Gujarat Sultanate (or the Sultanate of Guzerat), was a Medieval Indian kingdom established in the early 15th century in Western India, primarily in the present-day state of Gujarat, India. The dynasty was founded by Sultan Zafar Khan Muza ...

* Jaunpur Sultanate

The Jaunpur Sultanate ( fa, ) was an independent Islamic state in northern India between 1394 and 1479, ruled by the Sharqi dynasty. It was founded in 1394 by Khwajah-i-Jahan Malik Sarwar, a former wazir of Sultan Nasiruddin Muhammad Shah IV ...

* Bahamani Sultanate

The Bahmani Sultanate, or Deccan, was a Persianate Sunni Muslim Indian Kingdom located in the Deccan region. It was the first independent Muslim kingdom of the Deccan,

* Malwa Sultanate

The Malwa Sultanate ( fa, ) (Pashto: ; ''lit: Mālwā Salṭanat'') was a late medieval Islamic sultanate in the Malwa, Malwa region, covering the present day Indian states of Madhya Pradesh and south-eastern Rajasthan from 1392 to 1562. It w ...

* Khandesh Sultanate

* Bijapur Sultanate

The Adil Shahi or Adilshahi, was a Shia,Salma Ahmed Farooqui, ''A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: From Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century'', (Dorling Kindersley Pvt Ltd., 2011), 174. and later Sunni Muslim,Muhammad Qasim Firishta's T ...

* Ahmadnagar Sultanate

The Ahmadnagar Sultanate was a late medieval Indian Muslim kingdom located in the northwestern Deccan, between the sultanates of Gujarat and Bijapur. Malik Ahmed, the Bahmani governor of Junnar after defeating the Bahmani army led by general Ja ...

* Golconda Sultanate

The Qutb Shahi dynasty also called as Golconda Sultanate (Persian: ''Qutb Shāhiyān'' or ''Sultanat-e Golkonde'') was a Persianate Shia Islam dynasty of Turkoman origin that ruled the sultanate of Golkonda in southern India. After the coll ...

* Bidar Sultanate

Bidar sultanate was one of the Deccan sultanates of late medieval southern India. The sultanate emerged under the rule of Qasim Barid I in 1492 and leadership passed to his sons. Starting from the 1580s, a wave of successions occurred in th ...

* Berar Sultanate

Berar Sultanate, also called as Imad Shahi Sultanate was one of the Deccan sultanates, which was founded by an Indian Muslim. It was established in 1490 following the disintegration of the Bahmani Sultanate.

History

Background

The origin of th ...

* Carnatic Sultanate

The Carnatic Sultanate was a kingdom in South India between about 1690 and 1855, and was under the legal purview of the Nizam of Hyderabad, until their demise. They initially had their capital at Arcot in the present-day Indian state of Tamil N ...

* Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

* Sur Empire

The Sur Empire ( ps, د سرو امپراتورۍ, dë sru amparāturəi; fa, امپراطوری سور, emperâturi sur) was an Afghan dynasty which ruled a large territory in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent for nearly 16 year ...

* Sikh Empire

The Sikh Empire was a state originating in the Indian subcontinent, formed under the leadership of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who established an empire based in the Punjab. The empire existed from 1799, when Maharaja Ranjit Singh captured Lahor ...

* Jammu and Kashmir Jammu and Kashmir may refer to:

* Kashmir, the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent

* Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), a region administered by India as a union territory

* Jammu and Kashmir (state), a region administered ...

* Oudh

The Oudh State (, also Kingdom of Awadh, Kingdom of Oudh, or Awadh State) was a princely state in the Awadh region of North India until its annexation by the British in 1856. The name Oudh, now obsolete, was once the anglicized name of ...

* Rohilkhand

Rohilkhand (previously Rampur State) is a region in the northwestern part of Uttar Pradesh, India, that is centered on the Rampur, Bareilly and Moradabad divisions. It is part of the upper Ganges Plain, and is named after the Rohilla tribe. Th ...

( Rampur)

* Tonk

* Banganapalle

Banaganapalli is a town in the state of Andhra Pradesh, India. It lies in Nandyal district, 38 km west of the city of Nandyal. Banaganapalli is famous for its mangoes and has a cultivar, ''Banaganapalli'', named after it. Between 1790 and ...

* Malerkotla

Malerkotla is a city and district headquarters of Malerkotla district in the Indian state of Punjab. It was the seat of the eponymous princely state during the British Raj. The state acceded to the union of India in 1947 and was merged with ...

* Pataudi

Pataudi is a town and one of the 4 sub-divisions of Gurugram district, in the Indian States and territories of India, state of Haryana, within the boundaries of the National Capital Region of India. Ahirs/Yadav dominate the area. It is located f ...

* Bahawalpur

Bahawalpur () is a city in the Punjab province of Pakistan. With inhabitants as of 2017, it is Pakistan's 11th most populous city.

Founded in 1748, Bahawalpur was the capital of the former princely state of Bahawalpur, ruled by the Abbasi fa ...

* Bhopal

Bhopal (; ) is the capital city of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh and the administrative headquarters of both Bhopal district and Bhopal division. It is known as the ''City of Lakes'' due to its various natural and artificial lakes. It i ...

* Junagadh

Junagadh () is the headquarters of Junagadh district in the Indian state of Gujarat. Located at the foot of the Girnar hills, southwest of Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar (the state capital), it is the seventh largest city in the state.

Literally t ...

* Hyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River (India), Musi River, in the northern part ...

* Bengal (Subah)

History

Persianate culture flourished for nearly fourteen centuries. It was a mixture of Persian andIslamic

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the mai ...

cultures that eventually underwent Persification

Persianization () or Persification (; fa, پارسیسازی), is a sociological process of cultural change in which a non- Persian society becomes "Persianate", meaning it either directly adopts or becomes strongly influenced by the Persian ...

and became the dominant culture of the ruling and elite classes of Greater Iran

Greater Iran ( fa, ایران بزرگ, translit=Irān-e Bozorg) refers to a region covering parts of Western Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, Xinjiang, and the Caucasus, where both Culture of Iran, Iranian culture and Iranian langua ...

, Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, and South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;;;;; ...

.

When the peoples of Greater Iran were conquered by Islamic forces in the 7th and 8th centuries, they became part of an empire much larger than any previous one under Persian rule. While the Islamic conquest led to the Arabization

Arabization or Arabisation ( ar, تعريب, ') describes both the process of growing Arab influence on non-Arab populations, causing a language shift by the latter's gradual adoption of the Arabic language and incorporation of Arab culture, aft ...

of language and culture in the former Byzantine territories, this did not happen in Persia. Rather, the new Islamic culture evolving there was largely based on pre-Islamic Persian traditions of the area, as well as on the Islamic customs that were introduced to the region by the Arab conquerors.

Persianate culture, especially among the elite classes, spread across the Muslim territories in western, central, and south Asia, although populations across this vast region had conflicting allegiances (sectarian, local, tribal, and ethnic) and spoke many different languages. It was spread by poets, artists, architects, artisans, jurists, and scholars, who maintained relations among their peers in the far-flung cities of the Persianate world, from Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

.

Persianate culture involved modes of consciousness, ethos, and religious practices that have persisted in the Iranian world against hegemonic

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over other city-states. ...

Arab Muslim (Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

) cultural constructs. This formed a calcified Persianate structure of thought and experience of the sacred, entrenched for generations, which later informed history, historical memory, and identity among Alid

The Alids are those who claim descent from the '' rāshidūn'' caliph and Imam ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib (656–661)—cousin, son-in-law, and companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad—through all his wives. The main branches are the (inc ...

loyalists and heterodox

In religion, heterodoxy (from Ancient Greek: , "other, another, different" + , "popular belief") means "any opinions or doctrines at variance with an official or orthodox position". Under this definition, heterodoxy is similar to unorthodoxy, w ...

groups labeled by sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

-minded authorities as '' ghulāt''. In a way, along with investing the notion of heteroglossia

The term ''heteroglossia'' describes the coexistence of distinct varieties within a single "language" (in Greek: ''hetero-'' "different" and ''glōssa'' "tongue, language"). The term translates the Russian разноречие 'raznorechie'': lite ...

, Persianate culture embodies the Iranian past and ways in which this past blended with the Islamic present or became transmuted. The historical change was largely on the basis of a binary model: a struggle between the religious landscapes of late Iranian antiquity and a monotheist paradigm provided by the new religion, Islam.

This duality is symbolically expressed in the Shiite

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, most ...

tradition that Husayn ibn Ali

Abū ʿAbd Allāh al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, أبو عبد الله الحسين بن علي بن أبي طالب; 10 January 626 – 10 October 680) was a grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a son of Ali ibn Abi ...

, the third Shi'ite Imam, had married Shahrbanu use both this parameter and , birth_date to display the person's date of birth, date of death, and age at death) -->

, death_place = Bibi Shahr Banu Shrine(disputed)

, death_cause =

, body_discovered =

, resting_place = ...

, daughter of Yazdegerd III

Yazdegerd III (also spelled Yazdgerd III and Yazdgird III; pal, 𐭩𐭦𐭣𐭪𐭥𐭲𐭩) was the last Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from 632 to 651. His father was Shahriyar and his grandfather was Khosrow II.

Ascending the throne at t ...

, the last Sassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

king of Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. This genealogy makes the later imams, descended from Husayn and Shahrbanu, the inheritors of both the Islamic Prophet Muhammad and of the pre-Islamic Sassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

kings.

Origins

After the Arab Muslim conquest of Iran,Pahlavi

Pahlavi may refer to:

Iranian royalty

*Seven Parthian clans, ruling Parthian families during the Sasanian Empire

*Pahlavi dynasty, the ruling house of Imperial State of Persia/Iran from 1925 until 1979

**Reza Shah, Reza Shah Pahlavi (1878–1944 ...

, the language of Pre-Islamic Iran

The history of Iran is intertwined with the history of a larger region known as Greater Iran, comprising the area from Anatolia in the west to the borders of Ancient India and the Syr Darya in the east, and from the Caucasus and the Eurasian Step ...

, continued to be widely used well into the second Islamic century (8th century) as a medium of administration in the eastern lands of the Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

. Despite the Islamization

Islamization, Islamicization, or Islamification ( ar, أسلمة, translit=aslamāh), refers to the process through which a society shifts towards the religion of Islam and becomes largely Muslim. Societal Islamization has historically occur ...

of public affairs, the Iranians retained much of their pre-Islamic outlook and way of life, adjusted to fit the demands of Islam. Towards the end of the 7th century, the population began resenting the cost of sustaining the Arab caliphs

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

, the Umayyads Umayyads may refer to:

*Umayyad dynasty, a Muslim ruling family of the Caliphate (661–750) and in Spain (756–1031)

*Umayyad Caliphate (661–750)

:*Emirate of Córdoba (756–929)

:*Caliphate of Córdoba

The Caliphate of Córdoba ( ar, خ ...

, and in the 8th century, a general Iranian uprising—led by Abu Muslim Khorrasani—brought another Arab family, the Abbasids

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

, to the Caliph's throne.

Under the Abbasids, the capital shifted from Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

to Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, which had once been part of the Sassanid Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

and was still considered to be part of the Iranian cultural domain. Persian culture, and the customs of the Persian Barmakid

The Barmakids ( fa, برمکیان ''Barmakiyân''; ar, البرامكة ''al-Barāmikah''Harold Bailey, 1943. "Iranica" BSOAS 11: p. 2. India - Department of Archaeology, and V. S. Mirashi (ed.), ''Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era'' vol ...

vizier

A vizier (; ar, وزير, wazīr; fa, وزیر, vazīr), or wazir, is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the near east. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called ''katib'' (secretary), who was a ...

s, became the style of the ruling elite. Politically, the Abbasids soon started losing their control over Iranians. The governors of Khurasan

Greater Khorāsān,Dabeersiaghi, Commentary on Safarnâma-e Nâsir Khusraw, 6th Ed. Tehran, Zavvâr: 1375 (Solar Hijri Calendar) 235–236 or Khorāsān ( pal, Xwarāsān; fa, خراسان ), is a historical eastern region in the Iranian Plate ...

, the Tahirids

The Tahirid dynasty ( fa, طاهریان, Tâheriyân, ) was a culturally Arabized Sunni Muslim dynasty of Persian dehqan origin, that ruled as governors of Khorasan from 821 to 873 as well as serving as military and security commanders in Ab ...

, though appointed by the caliph, were effectively independent. When the Persian Saffarids

The Saffarid dynasty ( fa, صفاریان, safaryan) was a Persianate dynasty of eastern Iranian origin that ruled over parts of Persia, Greater Khorasan, and eastern Makran from 861 to 1003. One of the first indigenous Persian dynasties to emerg ...

from Sistan

Sistān ( fa, سیستان), known in ancient times as Sakastān ( fa, سَكاستان, "the land of the Saka"), is a historical and geographical region in present-day Eastern Iran ( Sistan and Baluchestan Province) and Southern Afghanistan (N ...

freed the eastern lands, the Buyyids

The Buyid dynasty ( fa, آل بویه, Āl-e Būya), also spelled Buwayhid ( ar, البويهية, Al-Buwayhiyyah), was a Shia Islam, Shia Iranian peoples, Iranian dynasty of Daylamites, Daylamite origin, which mainly ruled over Iraq and central ...

, the Ziyarids

The Ziyarid dynasty ( fa, زیاریان) was an Iranian dynasty of Gilaki origin that ruled Tabaristan from 931 to 1090 during the Iranian Intermezzo period. The empire rose to prominence during the leadership of Mardavij. After his death, his ...

and the Samanids People

A person (plural, : people) is a being that has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations such as kinship, ownershi ...

in Western Iran, Mazandaran and the north-east respectively, declared their independence.

The separation of the eastern territories from Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

was expressed in a distinctive Persianate culture that became dominant in west, central, and south Asia, and was the source of innovations elsewhere in the Islamic world. The Persianate culture was marked by the use of the New Persian

New Persian ( fa, فارسی نو), also known as Modern Persian () and Dari (), is the current stage of the Persian language spoken since the 8th to 9th centuries until now in Greater Iran and surroundings. It is conventionally divided into thre ...

language as a medium of administration and intellectual discourse, by the rise of Persianised-Turks to military control, by the new political importance of non-Arab ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

and by the development of an ethnically composite Islamic society.

Pahlavi

Pahlavi may refer to:

Iranian royalty

*Seven Parthian clans, ruling Parthian families during the Sasanian Empire

*Pahlavi dynasty, the ruling house of Imperial State of Persia/Iran from 1925 until 1979

**Reza Shah, Reza Shah Pahlavi (1878–1944 ...

was the ''lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

'' of the Sassanian Empire before the Arab invasion, but towards the end of the 7th and the beginning of the 8th century Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

became a medium of literary expression. In the 9th century, a New Persian language emerged as the idiom of administration and literature. The Tahirid and Saffarid dynasties continued using Persian as an informal language, although for them Arabic was the "language for recording anything worthwhile, from poetry to science", but the Samanids made Persian a language of learning and formal discourse. The language that appeared in the 9th and 10th centuries was a new form of Persian, derivative of the Middle-Persian of pre-Islamic times, but enriched amply by Arabic vocabulary and written in the Arabic script.

The Persian language, according to Marshall Hodgson

Marshall Goodwin Simms Hodgson (April 11, 1922 – June 10, 1968), was an Islamic studies academic and a world historian at the University of Chicago. He was chairman of the interdisciplinary Committee on Social Thought in Chicago.

Works

Though he ...

in his '' The Venture of Islam'', was to form the chief model for the rise of still other languages to the literary level. Like Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

, most of the more local languages of high culture that later emerged among Muslims were heavily influenced by Persian (Urdu

Urdu (;"Urdu"

''

''

The Iranian dynasty of the Samanids began recording its court affairs in Persian as well as Arabic, and the earliest great poetry in New Persian was written for the Samanid court. The Samanids encouraged translation of religious works from Arabic into Persian. In addition, the learned authorities of Islam, the ''ulama'', began using the Persian ''lingua franca'' in public. The crowning literary achievement in the early New Persian language was the ''

At the beginning of the 14th century, the

At the beginning of the 14th century, the

Association for the Study of Persianate Societies (ASPS)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Persianate Society Society of Iran Persian culture Cultural assimilation Cultural geography Cultural regions Social history of Azerbaijan Azerbaijani culture Social history of Iraq Persian language History of the Caucasus History of Turkey History of Central Asia Social history of Afghanistan Ottoman culture Mughal culture Sprachbund

Shahnameh

The ''Shahnameh'' or ''Shahnama'' ( fa, شاهنامه, Šāhnāme, lit=The Book of Kings, ) is a long epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi between c. 977 and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,00 ...

'' (Book of Kings), presented by its author Ferdowsi

Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi ( fa, ; 940 – 1019/1025 CE), also Firdawsi or Ferdowsi (), was a Persians, Persian poet and the author of ''Shahnameh'' ("Book of Kings"), which is one of the world's longest epic poetry, epic poems created by a sin ...

to the court of Mahmud of Ghazni

Yamīn-ud-Dawla Abul-Qāṣim Maḥmūd ibn Sebüktegīn ( fa, ; 2 November 971 – 30 April 1030), usually known as Mahmud of Ghazni or Mahmud Ghaznavi ( fa, ), was the founder of the Turkic Ghaznavid dynasty, ruling from 998 to 1030. At th ...

(998–1030). This was a kind of Iranian nationalistic resurrection: Ferdowsi galvanized Persian nationalistic sentiment by invoking pre-Islamic Persian heroic imagery and enshrined in literary form the most treasured folk stories.

Ferdowsi's ''Shahnameh'' enjoyed a special status in Iranian courtly culture as a historical narrative as well as a mythical one. The powerful effect that this text came to have on the poets of this period is partly due to the value that was attached to it as a legitimizing force, especially for new rulers in the Eastern Islamic world:

The Persianate culture that emerged under the Samanids in Greater Khorasan

Greater Khorāsān,Dabeersiaghi, Commentary on Safarnâma-e Nâsir Khusraw, 6th Ed. Tehran, Zavvâr: 1375 (Solar Hijri Calendar) 235–236 or Khorāsān ( pal, Xwarāsān; fa, خراسان ), is a historical eastern region in the Iranian Plate ...

, in northeast Persia and the borderlands of Turkistan

Turkestan, also spelled Turkistan ( fa, ترکستان, Torkestân, lit=Land of the Turks), is a historical region in Central Asia corresponding to the regions of Transoxiana and Xinjiang.

Overview

Known as Turan to the Persians, western Turke ...

exposed the Turks to Persianate culture; The incorporation of the Turks into the main body of the Middle Eastern Islamic civilization, which was followed by the Ghaznavids

The Ghaznavid dynasty ( fa, غزنویان ''Ġaznaviyān'') was a culturally Persianate, Sunni Muslim dynasty of Turkic ''mamluk'' origin, ruling, at its greatest extent, large parts of Persia, Khorasan, much of Transoxiana and the northwest ...

, thus began in Khorasan; "not only did the inhabitants of Khurasan not succumb to the language of the nomadic invaders, but they imposed their own tongue on them. The region could even assimilate the Turkic Ghaznavids and Seljuks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; fa, سلجوقیان ''Saljuqian'', alternatively spelled as Seljuqs or Saljuqs), also known as Seljuk Turks, Seljuk Turkomans "The defeat in August 1071 of the Byzantine emperor Romanos Diogenes

by the Turk ...

(11th and 12th centuries), the Timurids

The Timurid Empire ( chg, , fa, ), self-designated as Gurkani ( Chagatai: کورگن, ''Küregen''; fa, , ''Gūrkāniyān''), was a PersianateB.F. Manz, ''"Tīmūr Lang"'', in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Online Edition, 2006 Turco-Mongol empire ...

(14th and 15th centuries), and the Qajars

The Qajar dynasty (; fa, دودمان قاجار ', az, Qacarlar ) was an IranianAbbas Amanat, ''The Pivot of the Universe: Nasir Al-Din Shah Qajar and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831–1896'', I. B. Tauris, pp 2–3 royal dynasty of Turkic origin ...

(19th and 20th centuries).

The Ghaznavids, the rivals and future successors of the Samanids, ruled over the southeastern extremities of Samanid territories from the city of Ghazni

Ghazni ( prs, غزنی, ps, غزني), historically known as Ghaznain () or Ghazna (), also transliterated as Ghuznee, and anciently known as Alexandria in Opiana ( gr, Αλεξάνδρεια Ωπιανή), is a city in southeastern Afghanistan ...

. Persian scholars and artists flocked to their court, and the Ghaznavids became patrons of Persianate culture. The Ghaznavids took with them Persianate culture as they subjugated Western and Southern Asia . Apart from Ferdowsi, Rumi

Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī ( fa, جلالالدین محمد رومی), also known as Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī (), Mevlânâ/Mawlānā ( fa, مولانا, lit= our master) and Mevlevî/Mawlawī ( fa, مولوی, lit= my ma ...

, Abu Ali Sina, Al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

, Unsuri

Abul Qasim Hasan Unsuri Balkhi ( fa, ابوالقاسم حسن عنصری بلخی; died 1039/1040) was a 10–11th century Persian poet. ‘Unṣurī is said to have been born in Balkh, today located in Afghanistan, and he eventually became a poet ...

Balkhi, Farrukhi Sistani

Abu'l-Hasan Ali ibn Julugh Farrukhi Sistani ( fa, ابوالحسن علی بن جولوغ فرخی سیستانی), better known as Farrukhi Sistani (; – 1040) was one of the most prominent Persian court poets in the history of Persian literatur ...

, Sanayi Ghaznawi and Abu Sahl Testari were among the great Iranian scientists and poets of the period under Ghaznavid patronage.

Persianate culture was carried by successive dynasties into Western and Southern Asia, particularly by the Persianized Seljuqs

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; fa, سلجوقیان ''Saljuqian'', alternatively spelled as Seljuqs or Saljuqs), also known as Seljuk Turks, Seljuk Turkomans "The defeat in August 1071 of the Byzantine emperor Romanos Diogenes

by the Turk ...

(1040–1118) and their successor states, who presided over Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, and Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

until the 13th century, and by the Ghaznavids, who in the same period dominated Greater Khorasan and parts of India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. These two dynasties together drew the centers of the Islamic world eastward. The institutions stabilized Islamic society into a form that would persist, at least in Western Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

, until the 20th century.

The Ghaznavids moved their capital from Ghazni to Lahore

Lahore ( ; pnb, ; ur, ) is the second most populous city in Pakistan after Karachi and 26th most populous city in the world, with a population of over 13 million. It is the capital of the province of Punjab where it is the largest city. ...

in modern Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, which they turned into another center of Islamic culture. Under their patronage, poets and scholars from Kashgar

Kashgar ( ug, قەشقەر, Qeshqer) or Kashi ( zh, c=喀什) is an oasis city in the Tarim Basin region of Southern Xinjiang. It is one of the westernmost cities of China, near the border with Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Pakistan ...

, Bukhara

Bukhara (Uzbek language, Uzbek: /, ; tg, Бухоро, ) is the List of cities in Uzbekistan, seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan, with a population of 280,187 , and the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara ...

, Samarkand

fa, سمرقند

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from the top:Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zinda, ...

, Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, Nishapur

Nishapur or officially Romanized as Neyshabur ( fa, ;Or also "نیشاپور" which is closer to its original and historic meaning though it is less commonly used by modern native Persian speakers. In Persian poetry, the name of this city is wr ...

, Amol

Amol ( fa, آمل – ; ; also Romanized as Āmol and Amul) is a city and the administrative center of Amol County, Mazandaran Province, Iran, with a population of around 300,000 people.

Amol is located on the Haraz river bank. It is less than ...

and Ghazni congregated in Lahore. Thus, the Persian language and Persianate culture was brought deep into India and carried further in the 13th century. The Seljuqs won a decisive victory over the Ghaznavids and swept into Khorasan; they brought Persianate culture westward into western Persia, Iraq, Anatolia, and Syria. Iran proper along with Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

became the heartland of Persian language and culture.

As the Seljuqs came to dominate western Asia, their courts were Persianized as far west as the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

. Under their rule, many pre-Islamic Iranian traditional arts like Sassanid architecture were resurrected, and great Iranian scholars were patronized. At the same time, the Islamic religious institutions became more organized and Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

orthodoxy became more codified.

The Persian jurist and theologian Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian polymat ...

was among the scholars at the Seljuq court who proposed a synthesis of Sufism

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

and Sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

, which became the basis for a richer Islamic theology. Formulating the Sunni concept of division between temporal and religious authorities, he provided a theological basis for the existence of the Sultanate

This article includes a list of successive Islamic states and Muslim dynasties beginning with the time of the Islamic prophet Muhammad (570–632 CE) and the early Muslim conquests that spread Islam outside of the Arabian Peninsula, and continui ...

, a temporal office alongside the Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

, which at that time was merely a religious office. The main institutional means of establishing a consensus of the ''ulama'' on these dogmatic issues was the Nezamiyeh

The Nezamiyeh ( fa, نظامیه) or Nizamiyyah ( ar, النظامیة) are a group of institutions of higher education established by Khwaja Nizam al-Mulk in the eleventh century in Iran. The name ''nizamiyyah'' derives from his name. Founded a ...

, better known as the ''madrasa

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , pl. , ) is the Arabic word for any type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whether for elementary instruction or higher learning. The word is variously transliterated '' ...

s'', named after its founder Nizam al-Mulk

Abu Ali Hasan ibn Ali Tusi (April 10, 1018 – October 14, 1092), better known by his honorific title of Nizam al-Mulk ( fa, , , Order of the Realm) was a Persian scholar, jurist, political philosopher and Vizier of the Seljuk Empire. Rising fro ...

, a Persian vizier of the Seljuqs. These schools became the means of uniting Sunni ''ulama'', who legitimized the rule of the Sultans. The bureaucracies were staffed by graduates of the madrasas, so both the ''ulama'' and the bureaucracies were under the influence of esteemed professors at the ''madrasas''.

Shahnameh's impact and affirmation of Persianate culture

As the result of the impacts of Persian literature as well as to further political ambitions, it became a custom for rulers in the Persianate lands to not only commission a copy of the ''Shahnameh'', but also to have his own epic, allowing court poets to attempt to reach the level of Ferdowsi: Iranian and Persianate poets received the ''Shahnameh'' and modeled themselves after it. Murtazavi formulates three categories of such works too: poets who took up material not covered in the epic, poets who eulogized their patrons and their ancestors in ''masnavi

The ''Masnavi'', or ''Masnavi-ye-Ma'navi'' ( fa, مثنوی معنوی), also written ''Mathnawi'', or ''Mathnavi'', is an extensive poem written in Persian by Jalal al-Din Muhammad Balkhi, also known as Rumi. The ''Masnavi'' is one of the most ...

'' form for monetary reward, and poets who wrote poems for rulers who saw themselves as heroes in the ''Shahnameh'', echoing the earlier Samanid

The Samanid Empire ( fa, سامانیان, Sāmāniyān) also known as the Samanian Empire, Samanid dynasty, Samanid amirate, or simply as the Samanids) was a Persianate Sunni Muslim empire, of Iranian dehqan origin. The empire was centred in Kho ...

trend of patronizing the Shahnameh for legitimizing texts.

First, Persian poets attempted to continue the chronology to a later period, such as the '' Zafarnamah'' of the Ilkhanid

The Ilkhanate, also spelled Il-khanate ( fa, ایل خانان, ''Ilxānān''), known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (, ''Qulug-un Ulus''), was a khanate established from the southwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanid realm ...

historian Hamdollah Mostowfi

Hamdallah Mustawfi Qazvini ( fa, حمدالله مستوفى قزوینی, Ḥamdallāh Mustawfī Qazvīnī; 1281 – after 1339/40) was a Persian official, historian, geographer and poet. He lived during the last era of the Mongol Ilkhanate, and ...

(d. 1334 or 1335), which deals with Iranian history from the Arab conquest to the Mongols and is longer than Ferdowsi's work. The literary value of these works must be considered on an individual basis as Jan Rypka

Jan Rypka, PhDr., Dr.Sc. (28 May 1886 in Kroměříž – 29 December 1968 in Prague) was a prominent Czech orientalist, translator, professor of Iranology and Turkology at Charles University, Prague.

Jan Rypka was a participant in Ferdowsi ...

cautions: "all these numerous epics cannot be assessed very highly, to say nothing of those works that were substantially (or literally) copies of Ferdowsi. There are however exceptions, such as the ''Zafar-Nameh'' of Hamdu'llah Mustaufi a historically valuable continuation of the Shah-nama" and the ''Shahanshahnamah'' (or ''Changiznamah'') of Ahmad Tabrizi in 1337–38, which is a history of the Mongols written for Abu Sa'id.

Second, poets versified the history of a contemporary ruler for reward, such as the ''Ghazannameh'' written in 1361–62 by Nur al-Din ibn Shams al-Din. Third, heroes not treated in the ''Shahnameh'' and those having minor roles in it became the subjects of their own epics, such as the 11th-century ''Garshāspnāmeh'' by Asadi Tusi

Abu Nasr Ali ibn Ahmad Asadi Tusi ( fa, ابونصر علی بن احمد اسدی طوسی; – 1073) was a Persian poet, linguist and author. He was born at the beginning of the 11th century in Tus, Iran, in the province of Khorasan, and died in ...

. This tradition, chiefly a Timurid Timurid refers to those descended from Timur (Tamerlane), a 14th-century conqueror:

* Timurid dynasty, a dynasty of Turco-Mongol lineage descended from Timur who established empires in Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent

** Timurid Empire of C ...

one, resulted in the creation of Islamic epics of conquests as discussed by Marjan Molé. Also see the classification employed by Z. Safa for epics: ''milli'' (national, those inspired by Ferdowsi's epic), ''tarikhi'' (historical, those written in imitation of Nizami's Iskandarnamah) and ''dini'' for religious works. The other source of inspiration for Persianate culture was another Persian poet, Nizami, a most admired, illustrated and imitated writer of romantic ''masnavis''.

Along with Ferdowsi's and Nizami's works, Amir Khusraw Dehlavi

Abu'l Hasan Yamīn ud-Dīn Khusrau (1253–1325 AD), better known as Amīr Khusrau was an Indo-Persian Sufi singer, musician, poet and scholar who lived under the Delhi Sultanate. He is an iconic figure in the cultural history of the Indian sub ...

's ''khamseh

The Khamseh ( fa, ایلات خمسه) is a tribal confederation in the province of Fars in southwestern Iran. It consists of five tribes, hence its name ''Khamseh'', "''the five''". The tribes are partly nomadic, Some are Persian speaking Bass ...

'' came to enjoy tremendous prestige, and multiple copies of it were produced at Persianized courts. Seyller has a useful catalog of all known copies of this text.

Distinction

In the 16th century, Persianate culture became sharply distinct from the Arab world to the west, the dividing zone falling along theEuphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

. Socially the Persianate world was marked by a system of ethnologically defined elite statuses: the rulers and their soldiery were non-Iranians in origin, but the administrative cadres and literati were Iranians. Cultural affairs were marked by a characteristic pattern of language use: New Persian

New Persian ( fa, فارسی نو), also known as Modern Persian () and Dari (), is the current stage of the Persian language spoken since the 8th to 9th centuries until now in Greater Iran and surroundings. It is conventionally divided into thre ...

was the language of state affairs, scholarship and literature and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

the language of religion.

Safavids and the resurrection of Iranianhood in West Asia

TheSafavid

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often conside ...

dynasty ascended to predominance in Iran in the 16th century—the first native Iranian dynasty since the Buyyids

The Buyid dynasty ( fa, آل بویه, Āl-e Būya), also spelled Buwayhid ( ar, البويهية, Al-Buwayhiyyah), was a Shia Islam, Shia Iranian peoples, Iranian dynasty of Daylamites, Daylamite origin, which mainly ruled over Iraq and central ...

. The Safavids, who were of mixed Kurdish

Kurdish may refer to:

*Kurds or Kurdish people

*Kurdish languages

*Kurdish alphabets

*Kurdistan, the land of the Kurdish people which includes:

**Southern Kurdistan

**Eastern Kurdistan

**Northern Kurdistan

**Western Kurdistan

See also

* Kurd (dis ...

, Turkic, Georgian

Georgian may refer to:

Common meanings

* Anything related to, or originating from Georgia (country)

** Georgians, an indigenous Caucasian ethnic group

** Georgian language, a Kartvelian language spoken by Georgians

**Georgian scripts, three scrip ...

, Circassian and Pontic Greek

Pontic Greek ( pnt, Ποντιακόν λαλίαν, or ; el, Ποντιακή διάλεκτος, ; tr, Rumca) is a variety of Modern Greek indigenous to the Pontus region on the southern shores of the Black Sea, northeastern Anatolia, ...

ancestry, moved to the Ardabil

Ardabil (, fa, اردبیل, Ardabīl or ''Ardebīl'') is a city in northwestern Iran, and the capital of Ardabil Province. As of the 2022 census, Ardabil's population was 588,000. The dominant majority in the city are ethnic Iranian Azerbaija ...

region in the 11th century. They re-asserted the Persian identity over many parts of West Asia and Central Asia, establishing an independent Persian state, and patronizing Persian culture They made Iran the spiritual bastion of Shi’ism against the onslaughts of orthodox Sunni Islam

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagre ...

, and a repository of Persian cultural traditions and self-awareness of Persian identity.

The founder of the dynasty, Shah Isma'il, adopted the title of Persian Emperor ''Pādišah-ī Īrān'', with its implicit notion of an Iranian state stretching from Afghanistan as far as the Euphrates and the North Caucasus, and from the Oxus to the southern territories of the Persian Gulf. Shah Isma'il's successors went further and adopted the title of '' Shāhanshāh'' (king of kings). The Safavid kings considered themselves, like their predecessors the Sassanid Emperors, the ''khudāygān'' (the shadow of God on earth). They revived Sassanid architecture, build grand mosques and elegant ''charbagh'' gardens, collected books (one Safavid ruler had a library of 3,000 volumes), and patronized "Men of the Pen" The Safavids introduced Shiism into Persia to distinguish Persian society from the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

, their Sunni archrivals to the west.

Ottomans

At the beginning of the 14th century, the

At the beginning of the 14th century, the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

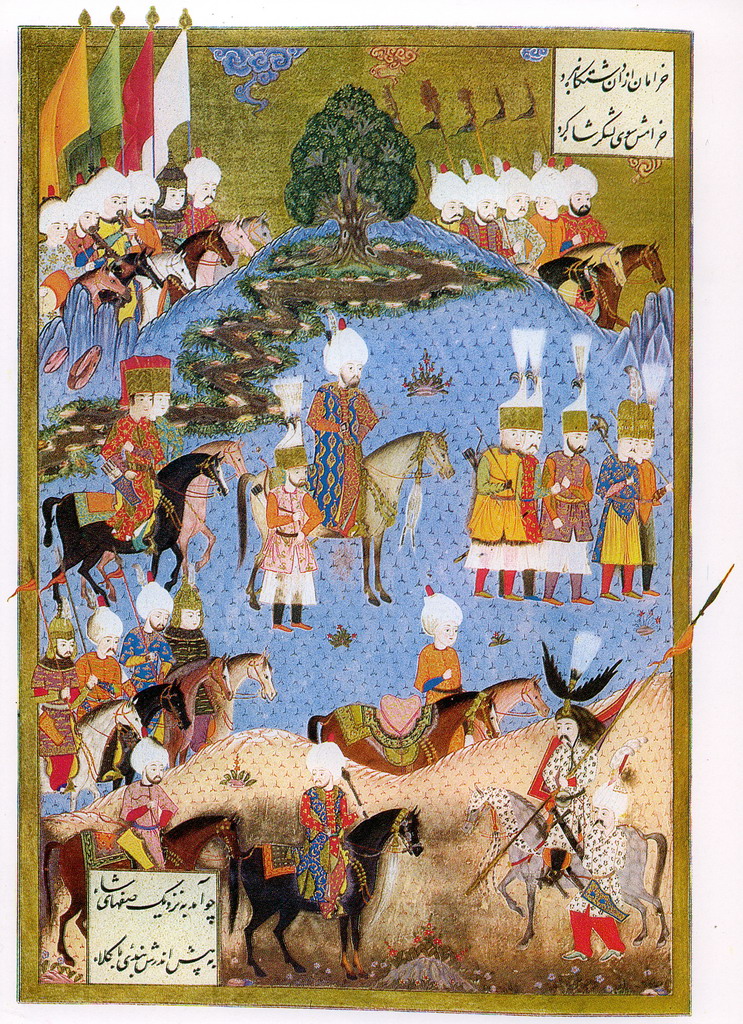

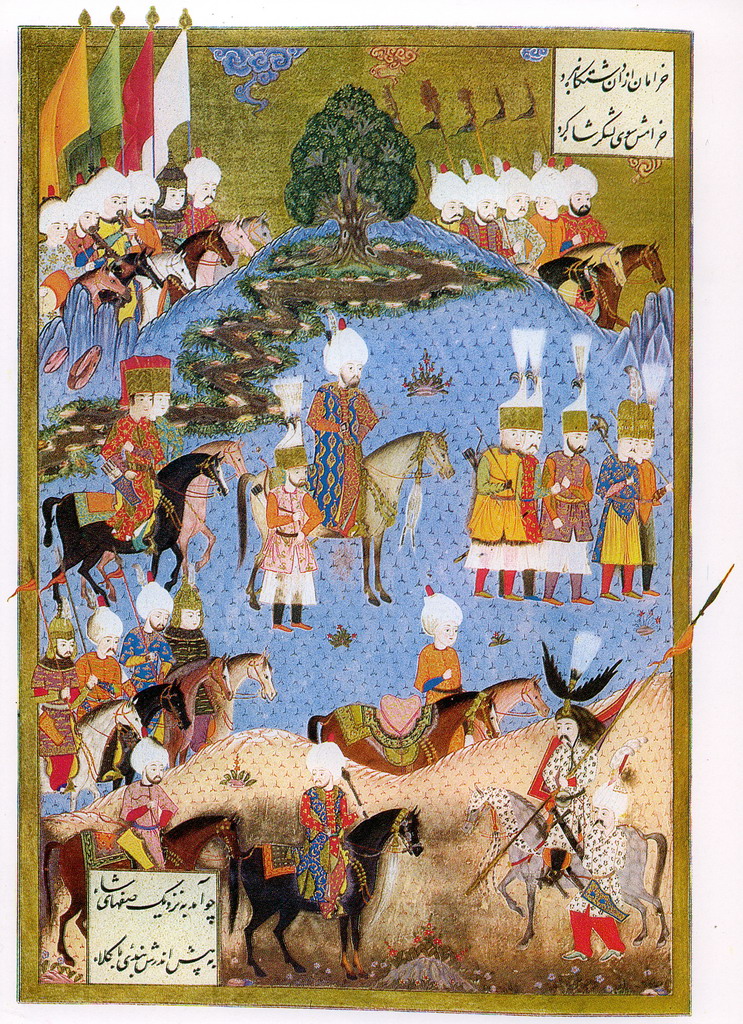

rose to predominance in Asia Minor. The Ottomans patronized Persian literature for five and a half centuries and attracted great numbers of writers and artists, especially in the 16th century. One of the most renowned Persian poets in the Ottoman court was Fethullah Arifi Çelebi

Fathallah, Fathalla or the Turkish variant Fethullah is a transliteration of the Arabic given name, فتح الله (''Fatḥ Allāh''), built from the Arabic words ''fath'' and ''Allah''. It is one of many Arabic theophoric names, meaning "Allah ...

, also a painter and historian, and the author of the ''Süleymanname

The ''Süleymannâme'' (lit. "Book of Suleiman") is an illustration of Suleiman the Magnificent's life and achievements. In 65 scenes the miniature paintings are decorated with gold, depicting battles, receptions, hunts and sieges. Written by Fet ...

'' (or ''Suleyman-nama''), a biography of Süleyman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ� ...

. At the end of the 17th century, they gave up Persian as the court and administrative language, using Turkish instead; a decision that shocked the highly Persianized Mughals in India. The Ottoman Sultan Suleyman wrote an entire divan

A divan or diwan ( fa, دیوان, ''dīvān''; from Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet) was a high government ministry in various Islamic states, or its chief official (see ''dewan'').

Etymology

The word, recorded in English since 1586, meanin ...

in Persian language. According to Hodgson:

Toynbee's assessment of the role of the Persian language is worth quoting in more detail, from ''A Study of History

''A Study of History'' is a 12-volume universal history by the British historian Arnold J. Toynbee, published from 1934 to 1961. It received enormous popular attention but according to historian Richard J. Evans, "enjoyed only a brief vogue befo ...

'':

E. J. W. Gibb is the author of the standard ''A Literary History of Ottoman Poetry'' in six volumes, whose name has lived on in an important series of publications of Arabic, Persian, and Turkish texts, the Gibb Memorial Series

The "E. J. W. Gibb Memorial" Series (abbreviation: GMS) is an orientalist book series with important works of Persian, Turkish and Arab history, literature, philosophy and religion, including many works in English translation. Some works were incl ...

. Gibb classifies Ottoman poetry between the "Old School", from the 14th century to about the middle of the 19th century, during which time Persian influence was dominant; and the "Modern School", which came into being as a result of the Western impact. According to Gibb in the introduction (Volume I):

The Saljuqs had, in the words of the same author:

Persianate culture of South Asia

In general, from its earliest days, Persian culture was brought into the Subcontinent (or South Asia) by various Persianised Turkic andAfghan

Afghan may refer to:

*Something of or related to Afghanistan, a country in Southern-Central Asia

*Afghans, people or citizens of Afghanistan, typically of any ethnicity

** Afghan (ethnonym), the historic term applied strictly to people of the Pas ...

dynasties. South Asian society was enriched by the influx of Persian-speaking and Islamic scholars, historians, architects, musicians, and other specialists of high Persianate culture who fled the Mongol devastation. The sultans of Delhi, who were of Turko-Afghan origin, modeled their lifestyles after the Persian upper classes. They patronized Persian literature and music, but became especially notable for their architecture, because their builders drew from Irano-Islamic architecture, combining it with Indian traditions to produce a profusion of mosques

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, i ...

, palaces, and tombs unmatched in any other Islamic country. The speculative thought of the times at the Mughal court, as in other Persianate courts, leaned towards the eclectic gnostic

Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized pe ...

dimension of Sufi Islam, having similarities with Hindu Vedantism, indigenous Bhakti

''Bhakti'' ( sa, भक्ति) literally means "attachment, participation, fondness for, homage, faith, love, devotion, worship, purity".See Monier-Williams, ''Sanskrit Dictionary'', 1899. It was originally used in Hinduism, referring to d ...

and popular theosophy

Theosophy is a religion established in the United States during the late 19th century. It was founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and draws its teachings predominantly from Blavatsky's writings. Categorized by scholars of religion a ...

.

The Mughals

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

, who were of Turco-Mongol

The Turco-Mongol or Turko-Mongol tradition was an ethnocultural synthesis that arose in Asia during the 14th century, among the ruling elites of the Golden Horde and the Chagatai Khanate. The ruling Mongol elites of these Khanates eventually ...

descent, strengthened the Indo-Persian culture

Indo-Persian culture refers to a cultural synthesis present in the Indian subcontinent. It is characterised by the absorption or integration of Persian aspects into the various cultures of Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. The earliest introductio ...

, in South Asia. For centuries, Iranian scholar-officials had immigrated to the region where their expertise in Persianate culture and administration secured them honored service within the Mughal Empire. Networks of learned masters and madrasas taught generations of young South Asian men Persian language and literature in addition to Islamic values and sciences. Furthermore, educational institutions such as Farangi Mahall and Delhi College developed innovative and integrated curricula for modernizing Persian-speaking South Asians. They cultivated Persian art, enticing to their courts artists and architects from Bukhara, Tabriz

Tabriz ( fa, تبریز ; ) is a city in northwestern Iran, serving as the capital of East Azerbaijan Province. It is the List of largest cities of Iran, sixth-most-populous city in Iran. In the Quri Chay, Quru River valley in Iran's historic Aze ...

, Herat

Herāt (; Persian: ) is an oasis city and the third-largest city of Afghanistan. In 2020, it had an estimated population of 574,276, and serves as the capital of Herat Province, situated south of the Paropamisus Mountains (''Selseleh-ye Safēd ...

, Shiraz

Shiraz (; fa, شیراز, Širâz ) is the List of largest cities of Iran, fifth-most-populous city of Iran and the capital of Fars province, Fars Province, which has been historically known as Pars (Sasanian province), Pars () and Persis. As o ...

, and other cities of Greater Iran. The Taj Mahal

The Taj Mahal (; ) is an Islamic ivory-white marble mausoleum on the right bank of the river Yamuna in the Indian city of Agra. It was commissioned in 1631 by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan () to house the tomb of his favourite wife, Mu ...

and its Charbagh

''Charbagh'' or ''Chahar Bagh'' ( ''chahār bāgh'', ''chārbāgh'', ''chār bāgh'', meaning "four gardens") is a Persian and Indo-Persian quadrilateral garden layout based on the four gardens of Paradise mentioned in the Quran. The quadr ...

were commissioned by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan

Shihab-ud-Din Muhammad Khurram (5 January 1592 – 22 January 1666), better known by his regnal name Shah Jahan I (; ), was the fifth emperor of the Mughal Empire, reigning from January 1628 until July 1658. Under his emperorship, the Mugha ...

for his Iranian bride.

Iranian poets, such as Sa’di, Hafez

Khwāje Shams-od-Dīn Moḥammad Ḥāfeẓ-e Shīrāzī ( fa, خواجه شمسالدین محمّد حافظ شیرازی), known by his pen name Hafez (, ''Ḥāfeẓ'', 'the memorizer; the (safe) keeper'; 1325–1390) and as "Hafiz", ...

, Rumi

Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī ( fa, جلالالدین محمد رومی), also known as Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī (), Mevlânâ/Mawlānā ( fa, مولانا, lit= our master) and Mevlevî/Mawlawī ( fa, مولوی, lit= my ma ...

and Nizami, who were great masters of Sufi mysticism from the Persianate world, were the favorite poets of the Mughals. Their works were present in Mughal libraries and counted among the emperors’ prized possessions, which they gave to each other; Akbar

Abu'l-Fath Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar (25 October 1542 – 27 October 1605), popularly known as Akbar the Great ( fa, ), and also as Akbar I (), was the third Mughal emperor, who reigned from 1556 to 1605. Akbar succeeded his father, Hum ...

and Jahangir

Nur-ud-Din Muhammad Salim (30 August 1569 – 28 October 1627), known by his imperial name Jahangir (; ), was the fourth Mughal Emperor, who ruled from 1605 until he died in 1627. He was named after the Indian Sufi saint, Salim Chishti.

Ear ...

often quoted from them, signifying that they had imbibed them to a great extent. An autographed note of both Jahangir and Shah Jahan on a copy of Sa’di's ''Gulestān'' states that it was their most precious possession. A gift of a ''Gulestān'' was made by Shah Jahan to Jahanara Begum

Jahanara Begum (23 March 1614 – 16 September 1681) was a Mughal princess and later the Padshah Begum of the Mughal Empire from 1631 to 1658 and again from 1668 until her death. She was the second and the eldest surviving child of Emperor Shah ...

, an incident which is recorded by her with her signature. Shah Jahan also considered the same work worthy enough to be sent as a gift to the king of England in 1628, which is presently in the Chester Beatty Library

The Chester Beatty Library, now known as the Chester Beatty, is a museum and library in Dublin. It was established in Ireland in 1950, to house the collections of mining magnate, Sir Alfred Chester Beatty. The present museum, on the grounds of ...

, Dublin. The emperor often took out auguries from a copy of the ''diwan'' of Hafez

Khwāje Shams-od-Dīn Moḥammad Ḥāfeẓ-e Shīrāzī ( fa, خواجه شمسالدین محمّد حافظ شیرازی), known by his pen name Hafez (, ''Ḥāfeẓ'', 'the memorizer; the (safe) keeper'; 1325–1390) and as "Hafiz", ...

belonging to his grandfather, Humayun

Nasir-ud-Din Muhammad ( fa, ) (; 6 March 1508 – 27 January 1556), better known by his regnal name, Humāyūn; (), was the second emperor of the Mughal Empire, who ruled over territory in what is now Eastern Afghanistan, Pakistan, Northern ...

. One such incident is recorded in his own handwriting in the margins of a copy of the ''diwan'', presently in the Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Library, Patna. The court poets Naziri Naziri is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Elhad Naziri (born 1992), Azerbaijani footballer

*Mirwais Naziri

Mirwais Naziri (date of birth unknown) is a right-handed batsman and medium pace bowler who played for the Afghanis ...

, ‘Urfi, Faizi

Abu al-Faiz ibn Mubarak, popularly known by his pen-name, Faizi (20 September 1547 – 15 October 1595) was a poet and scholar of late medieval India whose ancestors ''Malik-ush-Shu'ara'' (poet laureate) of Akbar's Court. Blochmann, H. (tr.) (19 ...

, Khan-i Khanan, Zuhuri, Sanai

Hakim Abul-Majd Majdūd ibn Ādam Sanā'ī Ghaznavi ( fa, ), more commonly known as Sanai, was a Persian poet from Ghazni who lived his life in the Ghaznavid Empire which is now located in Afghanistan. He was born in 1080 and died between 1131 ...

, Qodsi, Talib-i Amuli and Abu Talib Kalim were all masters imbued with a similar Sufi spirit, thus following the norms of any Persianate court.For the influence of Rumi's poetry on contemporary poetics, see Schimmel, The Triumphal Sun: 374.78; for Mughal poetry, see Ghani, A History of Persian Language and Literature; Rahman, Persian Literature; Hasan, Mughal Poetry; Abidi, .Tālib-I Āmulī; idem, .Qudsi Mashhadi.; Nabi Hadi, Talib-i Amuli; Browne, A Literary History, vol. IV: 241.67.

The tendency towards Sufi mysticism through Persianate culture in Mughal court circles is also testified by the inventory of books that were kept in Akbar's library, and are especially mentioned by his historian, Abu'l Fazl, in the ''Ā’in-ī Akbarī''. Some of the books that were read out continually to the emperor include the '' masnavis'' of Nizami, the works of Amir Khusrow

Abu'l Hasan Yamīn ud-Dīn Khusrau (1253–1325 AD), better known as Amīr Khusrau was an Indo-Persian Sufi singer, musician, poet and scholar who lived under the Delhi Sultanate. He is an iconic figure in the cultural history of the Indian s ...

, Sharaf Manayri and Jami, the '' Masnavi i-manavi'' of Rumi, the ''Jām-i Jam'' of Awhadi Maraghai

Awhadi Maraghei (also spelled Auhadi; fa, اوحدی مراغهای) (1274/75–1338) was a Persian Sufi poet primarily based in Azerbaijan during the rule of the Mongol Ilkhanate.

He is usually surnamed "Maraghai", but also mentioned as ...

, the ''Hakika o Sanā’i'', the ''Qabusnameh

''Qabus-nama'' or ''Qabus-nameh'' (variations: ''Qabusnamah'', ''Qabousnameh'', ''Ghabousnameh'', or ''Ghaboosnameh'', in Persian: or , "Book of Kavus"), ''Mirror of Princes'', is a major work of Persian literature, from the eleventh century (c ...

'' of Keikavus

Keikavus ( fa, كيكاوس) was the ruler of the Ziyarid dynasty from ca. 1050 to 1087. He was the son of Iskandar and grandson of Qabus. During his reign, he had little power, due to his status as a vassal to the Seljuqs. He is the celebrated a ...

, Sa’di's ''Gulestān'' and ''Būstān'', and the ''diwans'' of Khaqani

Afzal al-Dīn Badīl ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿOthmān, commonly known as Khāqānī ( fa, خاقانی, , – 1199), was a major Persian poet and prose-writer. He was born in Transcaucasia in the historical region known as Shirvan, where he served as ...

and Anvari

Anvari (1126–1189), full name Awhad ad-Din 'Ali ibn Mohammad Khavarani or Awhad ad-Din 'Ali ibn Mahmud ( fa, اوحدالدین علی ابن محمد انوری) was a Persian poet.

Anvarī was born in Abivard (now in Turkmenistan) and died in ...

.

This intellectual symmetry continued until the end of the 19th century, when a Persian newspaper, ''Miftah al-Zafar'' (1897), campaigned for the formation of Anjuman-i Ma’arif, an academy devoted to the strengthening of Persian language as a scientific language.

Media of Persianate culture

Persian poetry (Sufi poetry)

From about the 12th century, Persian lyric poetry was enriched with a spirituality and devotional depth not to be found in earlier works. This development was due to the pervasive spread of mystical experience within Islam.Sufism

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

developed in all Muslim lands, including the sphere of Persian cultural influence. As a counterpoise to the rigidity of formal Islamic theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

and law, Islamic mysticism sought to approach the divine through acts of devotion and love rather than through mere rituals and observance. Love of God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

being the focus of the Sufis' religious sentiments, it was only natural for them to express it in lyrical terms, and Persian Sufis

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spiri ...

, often of exceptional sensibility and endowed with poetic verve, did not hesitate to do so. The famous 11th-century Sufi, Abu Sa'id of Mehna frequently used his own love quatrains

A quatrain is a type of stanza, or a complete poem, consisting of four lines.

Existing in a variety of forms, the quatrain appears in poems from the poetic traditions of various ancient civilizations including Persia, Ancient India, Ancient Greec ...

(as well as others) to express his spiritual yearnings, and with mystic poets such as Attar

Attar or Attoor ( ar, عطار, ) may refer to:

People

*Attar (name)

*Fariduddin Attar, 12th-century Persian poet

Places

*Attar (Madhya Pradesh), the location of Attar railway station, Madhya Pradesh, India

*Attar, Iran, a village in Razavi Kho ...

and Iraqi, mysticism became a legitimate, even fashionable subject of lyric poems among the Persianate societies. Furthermore, as Sufi orders and centers (''Khaneghah'') spread throughout Persian societies, Persian mystic poetic thought gradually became so much a part of common culture that even poets who did not share Sufi experiences ventured to express mystical ideas and imagery in their work.

Shi'ism

Persian music

Conclusion

As the broad cultural region remained politically divided, the sharp antagonisms between empires stimulated the appearance of variations of Persianate culture. After 1500, the Iranian culture developed distinct features of its own, with interposition of strong pre-Islamic and Shiite Islamic culture. Iran's ancient cultural relationship withSouthern Iraq

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, ...

(Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of c ...

/Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

) remained strong and endured in spite of the loss of Mesopotamia to the Ottomans. Its ancient cultural and historical relationship with the Caucasus endured until the loss of Azerbaijan, Armenia, eastern Georgia (country), Georgia and parts of the North Caucasus to Imperial Russia following the Russo-Persian Wars in the course of the 19th century. The culture of peoples of the eastern Mediterranean in Anatolia, Syria, and Egypt developed somewhat independently; India developed a vibrant and completely distinct South Asian style with little to no remnants of the once patronized Indo-Persian culture by the Mughals.

See also

*Persianization *Turco-Persian traditionNotes

References

Notes