Peasants' Revolt (death Of Wat Tyler) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Black Death in the 1340s, the high taxes resulting from the conflict with France during the Hundred Years' War, and instability within the local leadership of London.

The final trigger for the revolt was the intervention of a royal official, John Bampton, in

Richard's government was formed around his uncles, most prominently the rich and powerful John of Gaunt, and many of his grandfather's former senior officials. They faced the challenge of financially sustaining the war in France. Taxes in the 14th century were raised on an ''ad hoc'' basis through Parliament, then comprising the Lords, the titled aristocracy and clergy; and the

Richard's government was formed around his uncles, most prominently the rich and powerful John of Gaunt, and many of his grandfather's former senior officials. They faced the challenge of financially sustaining the war in France. Taxes in the 14th century were raised on an ''ad hoc'' basis through Parliament, then comprising the Lords, the titled aristocracy and clergy; and the

The decades running up to 1381 were a rebellious, troubled period. London was a particular focus of unrest, and the activities of the city's politically active

The decades running up to 1381 were a rebellious, troubled period. London was a particular focus of unrest, and the activities of the city's politically active

By the next day, the revolt was rapidly growing. The villagers spread the news across the region, and John Geoffrey, a local bailiff, rode between Brentwood and

By the next day, the revolt was rapidly growing. The villagers spread the news across the region, and John Geoffrey, a local bailiff, rode between Brentwood and

The Kentish advance on London appears to have been coordinated with the movement of the rebels in Essex, Suffolk and

The Kentish advance on London appears to have been coordinated with the movement of the rebels in Essex, Suffolk and

The rebels began to cross from Southwark onto London Bridge on the afternoon of 13 June. The defences on London Bridge were opened from the inside, either in sympathy for the rebel cause or out of fear, and the rebels advanced into the city. At the same time, the rebel force from Essex made its way towards

The rebels began to cross from Southwark onto London Bridge on the afternoon of 13 June. The defences on London Bridge were opened from the inside, either in sympathy for the rebel cause or out of fear, and the rebels advanced into the city. At the same time, the rebel force from Essex made its way towards

On the morning of 14 June, the crowd continued west along the Thames, burning the houses of officials around

On the morning of 14 June, the crowd continued west along the Thames, burning the houses of officials around

On 15 June the royal government and the remaining rebels, who were unsatisfied with the charters granted the previous day, agreed to meet at Smithfield, just outside the city walls. London remained in confusion, with various bands of rebels roaming the city independently. Richard prayed at Westminster Abbey, before setting out for the meeting in the late afternoon. The chroniclers' accounts of the encounter all vary on matters of detail, but agree on the broad sequence of events. The King and his party, at least 200 strong and including

On 15 June the royal government and the remaining rebels, who were unsatisfied with the charters granted the previous day, agreed to meet at Smithfield, just outside the city walls. London remained in confusion, with various bands of rebels roaming the city independently. Richard prayed at Westminster Abbey, before setting out for the meeting in the late afternoon. The chroniclers' accounts of the encounter all vary on matters of detail, but agree on the broad sequence of events. The King and his party, at least 200 strong and including

While the revolt was unfolding in London, John Wrawe led his force into Suffolk. Wrawe had considerable influence over the development of the revolt across eastern England, where there may have been almost as many rebels as in the London revolt. The authorities put up very little resistance to the revolt: the major nobles failed to organise defences, key fortifications fell easily to the rebels and the local militias were not mobilised. As in London and the south-east, this was in part due to the absence of key military leaders and the nature of English law, but any locally recruited men might also have proved unreliable in the face of a popular uprising.

On 12 June, Wrawe attacked Sir Richard Lyons' property at Overhall, advancing on to

While the revolt was unfolding in London, John Wrawe led his force into Suffolk. Wrawe had considerable influence over the development of the revolt across eastern England, where there may have been almost as many rebels as in the London revolt. The authorities put up very little resistance to the revolt: the major nobles failed to organise defences, key fortifications fell easily to the rebels and the local militias were not mobilised. As in London and the south-east, this was in part due to the absence of key military leaders and the nature of English law, but any locally recruited men might also have proved unreliable in the face of a popular uprising.

On 12 June, Wrawe attacked Sir Richard Lyons' property at Overhall, advancing on to  On 15 June, revolt broke out in

On 15 June, revolt broke out in

Revolts also occurred across the rest of England, particularly in the cities of the north, traditionally centres of political unrest. In the town of

Revolts also occurred across the rest of England, particularly in the cities of the north, traditionally centres of political unrest. In the town of

The royal suppression of the revolt began shortly after the death of Wat Tyler on 15 June. Sir

The royal suppression of the revolt began shortly after the death of Wat Tyler on 15 June. Sir

The royal government and Parliament began to re-establish the normal processes of government after the revolt; as the historian

The royal government and Parliament began to re-establish the normal processes of government after the revolt; as the historian

Chroniclers primarily described the rebels as rural serfs, using broad, derogatory

Chroniclers primarily described the rebels as rural serfs, using broad, derogatory

Contemporary chroniclers of the events in the revolt have formed an important source for historians. The chroniclers were biased against the rebel cause and typically portrayed the rebels, in the words of the historian Susan Crane, as "beasts, monstrosities or misguided fools". London chroniclers were also unwilling to admit the role of ordinary Londoners in the revolt, preferring to place the blame entirely on rural peasants from the south-east. Among the key accounts was the anonymous '' Anonimalle Chronicle'', whose author appears to have been part of the royal court and an eye-witness to many of the events in London. The chronicler Thomas Walsingham was present for much of the revolt, but focused his account on the terror of the social unrest and was extremely biased against the rebels. The events were recorded in France by

Contemporary chroniclers of the events in the revolt have formed an important source for historians. The chroniclers were biased against the rebel cause and typically portrayed the rebels, in the words of the historian Susan Crane, as "beasts, monstrosities or misguided fools". London chroniclers were also unwilling to admit the role of ordinary Londoners in the revolt, preferring to place the blame entirely on rural peasants from the south-east. Among the key accounts was the anonymous '' Anonimalle Chronicle'', whose author appears to have been part of the royal court and an eye-witness to many of the events in London. The chronicler Thomas Walsingham was present for much of the revolt, but focused his account on the terror of the social unrest and was extremely biased against the rebels. The events were recorded in France by

The Peasants' Revolt became a popular literary subject. The poet

The Peasants' Revolt became a popular literary subject. The poet

"John Ball and the 'Peasants' Revolt'"

in James Crossley and Alastair Lockhart (eds.),

Critical Dictionary of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements

'. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Peasants' Revolt

– World History Encyclopedia

John Ball, English Legend

– A website about John Ball and the Peasants' Revolt from 1381 to the present

People of 1381

– A project on collecting data about individuals involved in the events of 1381

The Peasants' Revolt

BBC Radio 4 discussion with Miri Rubin, Caroline Barron & Alastair Dunn (''In Our Time'', 16 November 2006)

When Medieval Peasants Revolted Against The Establishment , Peasants' Revolt Of 1381 , Timeline

The Peasants' Revolt of 1381 presented by Tony Robinson. * {{Authority control 14th-century rebellions 14th century in London History of Essex History of Kent History of the Royal Borough of Greenwich Battles and military actions in London Protests in England Rebellions in medieval England Richard II of England 1381 in England Conflicts in 1381 Riots and civil disorder in England

Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and Grea ...

on 30 May 1381. His attempts to collect unpaid poll taxes

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments f ...

in Brentwood ended in a violent confrontation, which rapidly spread across the south-east of the country. A wide spectrum of rural society, including many local artisans and village officials, rose up in protest, burning court records and opening the local gaol

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, English language in England, standard English, Australian English, Australian, and Huron Historic Gaol, historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention cen ...

s. The rebels sought a reduction in taxation, an end to serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which deve ...

, and the removal of King Richard II's senior officials and law courts.

Inspired by the sermons of the radical cleric John Ball and led by Wat Tyler

Wat Tyler (c. 1320/4 January 1341 – 15 June 1381) was a leader of the 1381 Peasants' Revolt in England. He led a group of rebels from Canterbury to London to oppose the institution of a poll tax and to demand economic and social reforms. Wh ...

, a contingent of Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

ish rebels advanced on London. They were met at Blackheath by representatives of the royal government, who unsuccessfully attempted to persuade them to return home. King Richard, then aged 14, retreated to the safety of the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

, but most of the royal forces were abroad or in northern England. On 13 June, the rebels entered London and, joined by many local townsfolk, attacked the gaols, destroyed the Savoy Palace

The Savoy Palace, considered the grandest nobleman's townhouse of medieval London, was the residence of prince John of Gaunt until it was destroyed during rioting in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. The palace was on the site of an estate given to ...

, set fire to law books and buildings in the Temple, and killed anyone associated with the royal government. The following day, Richard met the rebels at Mile End

Mile End is a district of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in the East End of London, England, east-northeast of Charing Cross. Situated on the London-to-Colchester road, it was one of the earliest suburbs of London. It became part of the m ...

and agreed to most of their demands, including the abolition of serfdom. Meanwhile, rebels entered the Tower of London, killing Simon Sudbury

Simon Sudbury ( – 14 June 1381) was Bishop of London from 1361 to 1375, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1375 until his death, and in the last year of his life Lord Chancellor of England. He met a violent death during the Peasants' Revolt in 1 ...

, Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

, and Robert Hales

Sir Robert Hales ( – 14 June 1381) was Grand Prior of the Knights Hospitaller of England, Lord High Treasurer, and Admiral of the West. He was killed in the Peasants' Revolt.

Career

In 1372 Robert Hales became the Lord/Grand Prior of th ...

, Lord High Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State in ...

, whom they found inside.

On 15 June, Richard left the city to meet Tyler and the rebels at Smithfield. Violence broke out, and Richard's party killed Tyler. Richard defused the tense situation long enough for London's mayor, William Walworth

Sir William Walworth (died 1385) was an English nobleman and politician who was twice Lord Mayor of London (1374–75 and 1380–81). He is best known for killing Wat Tyler during the Peasants' Revolt in 1381.

Political career

His family ca ...

, to gather a militia from the city and disperse the rebel forces. Richard immediately began to re-establish order in London and rescinded his previous grants to the rebels. The revolt had also spread into East Anglia, where the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world's third oldest surviving university and one of its most pr ...

was attacked and many royal officials were killed. Unrest continued until the intervention of Henry Despenser, who defeated a rebel army at the Battle of North Walsham

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

on 25 or 26 June. Troubles extended north to York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, Beverley

Beverley is a market and minster town and a civil parish in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England, of which it is the county town. The town centre is located south-east of York's centre and north-west of City of Hull.

The town is known fo ...

and Scarborough Scarborough or Scarboro may refer to:

People

* Scarborough (surname)

* Earl of Scarbrough

Places Australia

* Scarborough, Western Australia, suburb of Perth

* Scarborough, New South Wales, suburb of Wollongong

* Scarborough, Queensland, su ...

, and as far west as Bridgwater in Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

. Richard mobilised 4,000 soldiers to restore order. Most of the rebel leaders were tracked down and executed; by November, at least 1,500 rebels had been killed.

The Peasants' Revolt has been widely studied by academics. Late 19th-century historians used a range of sources from contemporary chroniclers

A chronicle ( la, chronica, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and l ...

to assemble an account of the uprising, and these were supplemented in the 20th century by research using court records and local archives. Interpretations of the revolt have shifted over the years. It was once seen as a defining moment in English history, but modern academics are less certain of its impact on subsequent social and economic history. The revolt heavily influenced the course of the Hundred Years' War, by deterring later Parliaments from raising additional taxes to pay for military campaigns in France. The revolt has been widely used in socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

literature, including by the author William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

, and remains a potent political symbol for the political left

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

, informing the arguments surrounding the introduction of the Community Charge

The Community Charge, commonly known as the poll tax, was a system of taxation introduced by Margaret Thatcher's government in replacement of domestic rates in Scotland from 1989, prior to its introduction in England and Wales from 1990. It pr ...

in the United Kingdom during the 1980s.

Background and causes

Economics

The Peasants' Revolt was fed by the economic and social upheaval of the 14th century. At the start of the century, the majority of English people worked in the countryside economy that fed the country's towns and cities and supported an extensive international trade. Across much of England, production was organised around manors, controlled by local lords – including thegentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

and the Church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* C ...

– and governed through a system of manorial courts. Some of the population were unfree serfs, who had to work on their lords' lands for a period each year, although the balance of free and unfree varied across England, and in the south-east serfdom was relatively rare. Some serfs were born unfree and could not leave their manors to work elsewhere without the consent of the local lord; others accepted limitations on their freedom as part of the tenure agreement for their farmland. Population growth led to pressure on the available agricultural land, increasing the power of local landowners.

In 1348 a plague known as the Black Death crossed from mainland Europe into England, rapidly killing an estimated 50 per cent of the population. After an initial period of economic shock, England began to adapt to the changed economic situation. The death rate among the peasantry meant that suddenly land was relatively plentiful and labourers in much shorter supply. Labourers could charge more for their work and, in the consequent competition for labour, wages were driven sharply upwards. In turn, the profits of landowners were eroded. The trading, commercial and financial networks in the towns disintegrated.

The authorities responded to the chaos by passing emergency legislation, the Ordinance of Labourers in 1349, and the Statute of Labourers in 1351. These attempted to fix wages at pre-plague levels, making it a crime to refuse work or to break an existing contract, imposing fines on those who transgressed. The system was initially enforced through special Justices

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as a part of a panel of judges. A judge hears all the witnesses and any other evidence presented by the barristers or solicitors of the case, assesses the credibility an ...

of Labourers and then, from the 1360s onwards, through the normal Justices of the Peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

, typically members of the local gentry. Although in theory these laws applied to both labourers seeking higher wages and to employers tempted to outbid their competitors for workers, they were in practice applied only to labourers, and then in a rather arbitrary fashion. The legislation was strengthened in 1361, with the penalties increased to include branding and imprisonment. The royal government had not intervened in this way before, nor allied itself with the local landowners in quite such an obvious or unpopular way.

Over the next few decades, economic opportunities increased for the English peasantry. Some labourers took up specialist jobs that would have previously been barred to them, and others moved from employer to employer, or became servants in richer households. These changes were keenly felt across the south-east of England, where the London market created a wide range of opportunities for farmers and artisans. Local lords had the right to prevent serfs from leaving their manors, but when serfs found themselves blocked in the manorial courts, many simply left to work illegally on manors elsewhere. Wages continued to rise, and between the 1340s and the 1380s the purchasing power of rural labourers increased by around 40 percent. As the wealth of the lower classes increased, Parliament brought in fresh laws in 1363 to prevent them from consuming expensive goods formerly only affordable by the elite. These sumptuary laws proved unenforceable, but the wider labour laws continued to be firmly applied.

War and finance

Another factor in the revolt of 1381 was the conduct of the war with France. In 1337Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ...

had pressed his claims to the French throne, beginning a long-running conflict that became known as the Hundred Years' War. Edward had initial successes, but his campaigns were not decisive. Charles V of France

Charles V (21 January 1338 – 16 September 1380), called the Wise (french: le Sage; la, Sapiens), was King of France from 1364 to his death in 1380. His reign marked an early high point for France during the Hundred Years' War, with his armi ...

became more active in the conflict after 1369, taking advantage of his country's greater economic strength to commence cross-Channel raids on England. By the 1370s, England's armies on the continent were under huge military and financial pressure; the garrisons in Calais and Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

alone, for example, were costing £36,000 a year to maintain, while military expeditions could consume £50,000 in only six months. Edward died in 1377, leaving the throne to his grandson, Richard II, then only ten years old.

Richard's government was formed around his uncles, most prominently the rich and powerful John of Gaunt, and many of his grandfather's former senior officials. They faced the challenge of financially sustaining the war in France. Taxes in the 14th century were raised on an ''ad hoc'' basis through Parliament, then comprising the Lords, the titled aristocracy and clergy; and the

Richard's government was formed around his uncles, most prominently the rich and powerful John of Gaunt, and many of his grandfather's former senior officials. They faced the challenge of financially sustaining the war in France. Taxes in the 14th century were raised on an ''ad hoc'' basis through Parliament, then comprising the Lords, the titled aristocracy and clergy; and the Commons

The commons is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable Earth. These resources are held in common even when owned privately or publicly. Commons c ...

, the representatives of the knights, merchants and senior gentry from across England. These taxes were typically imposed on a household's movable possessions, such as their goods or stock. The raising of these taxes affected the members of the Commons much more than the Lords. To complicate matters, the official statistics used to administer the taxes pre-dated the Black Death and, since the size and wealth of local communities had changed greatly since the plague, effective collection had become increasingly difficult.

Just before Edward's death, Parliament introduced a new form of taxation called the poll tax, which was levied at the rate of four pence on every person over the age of 14, with a deduction for married couples.; Designed to spread the cost of the war over a broader economic base than previous tax levies, this round of taxation proved extremely unpopular but raised £22,000. The war continued to go badly and, despite raising some money through forced loans, the Crown returned to Parliament in 1379 to request further funds. The Commons were supportive of the young King, but had concerns about the amounts of money being sought and the way this was being spent by the King's counsellors, whom they suspected of corruption. A second poll tax was approved, this time with a sliding scale of taxes against seven different classes of English society, with the upper classes paying more in absolute terms. Widespread evasion proved to be a problem, and the tax only raised £18,600 – far short of the £50,000 that had been hoped for.

In November 1380, Parliament was called together again in Northampton. Archbishop Simon Sudbury

Simon Sudbury ( – 14 June 1381) was Bishop of London from 1361 to 1375, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1375 until his death, and in the last year of his life Lord Chancellor of England. He met a violent death during the Peasants' Revolt in 1 ...

, the new Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

, updated the Commons on the worsening situation in France, a collapse in international trade, and the risk of the Crown having to default on its debts. The Commons were told that the colossal sum of £160,000 was now required in new taxes, and arguments ensued between the royal council and Parliament about what to do next. Parliament passed a third poll tax (this time on a flat-rate basis of 12 pence on each person over 15, with no allowance made for married couples) which they estimated would raise £66,666. The third poll tax was highly unpopular and many in the south-east evaded it by refusing to register. The royal council appointed new commissioners in March 1381 to interrogate local village and town officials in an attempt to find those who were refusing to comply. The extraordinary powers and interference of these teams of investigators in local communities, primarily in the south-east and east of England, raised still further the tensions surrounding the taxes.

Protest and authority

The decades running up to 1381 were a rebellious, troubled period. London was a particular focus of unrest, and the activities of the city's politically active

The decades running up to 1381 were a rebellious, troubled period. London was a particular focus of unrest, and the activities of the city's politically active guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

s and fraternities

A fraternity (from Latin ''frater'': "brother"; whence, " brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club or fraternal order traditionally of men associated together for various religious or secular aims. Fraternity ...

often alarmed the authorities. Londoners resented the expansion of the royal legal system in the capital, in particular the increased role of the Marshalsea Court

The Marshalsea Court (or Court of the Marshalsea, also known as the Court of the Verge or the Court of the Marshal and Steward) was a court associated with the Royal Household in England. Associated with, but distinct from, the Marshalsea Court ...

in Southwark, which had begun to compete with the city authorities for judicial power in London. The city's population also resented the presence of foreigners, Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

weavers in particular. Londoners detested John of Gaunt because he was a supporter of the religious reformer John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 – 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, theologian, biblical translator, reformer, Catholic priest, and a seminary professor at the University of ...

, whom the London public regarded as a heretic. John of Gaunt was also engaged in a feud with the London elite and was rumoured to be planning to replace the elected mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well ...

with a captain, appointed by the Crown. The London elite were themselves fighting out a vicious, internal battle for political power. As a result, in 1381 the ruling classes in London were unstable and divided.

Rural communities, particularly in the south-east, were unhappy with the operation of serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which deve ...

and the use of the local manorial courts to exact traditional fines and levies, not least because the same landowners who ran these courts also often acted as enforcers of the unpopular labour laws or as royal judges. Many of the village elites refused to take up positions in local government and began to frustrate the operation of the courts. Animals seized by the courts began to be retaken by their owners, and legal officials were assaulted. Some started to advocate the creation of independent village communities, respecting traditional laws but separate from the hated legal system centred in London. As the historian Miri Rubin describes, for many, "the problem was not the country's laws, but those charged with applying and safeguarding them".

Concerns were raised about these changes in society. William Langland

William Langland (; la, Willielmus de Langland; 1332 – c. 1386) is the presumed author of a work of Middle English alliterative verse generally known as ''Piers Plowman'', an allegory with a complex variety of religious themes. The poem tr ...

wrote the poem '' Piers Plowman'' in the years before 1380, praising peasants who respected the law and worked hard for their lords, but complaining about greedy, travelling labourers demanding higher wages. The poet John Gower

John Gower (; c. 1330 – October 1408) was an English poet, a contemporary of William Langland and the Pearl Poet, and a personal friend of Geoffrey Chaucer. He is remembered primarily for three major works, the '' Mirour de l'Omme'', '' Vo ...

warned against a future revolt in both '' Mirour de l'Omme'' and ''Vox Clamantis

''Vox Clamantis'' ("the voice of one crying out") is a Latin poem of 10,265 lines in elegiac couplets by John Gower (1330 – October 1408) . The first of the seven books is a dream vision giving a vivid account of the Peasants' Rebellion of ...

''. There was a moral panic

A moral panic is a widespread feeling of fear, often an irrational one, that some evil person or thing threatens the values, interests, or well-being of a community or society. It is "the process of arousing social concern over an issue", us ...

about the threat posed by newly arrived workers in the towns and the possibility that servants might turn against their masters. New legislation was introduced in 1359 to deal with migrants, existing conspiracy laws were more widely applied and the treason laws were extended to include servants or wives who betrayed their masters and husbands. By the 1370s, there were fears that if the French invaded England, the rural classes might side with the invaders.

The discontent began to give way to open protest. In 1377, the " Great Rumour" occurred in south-east and south-west England. Rural workers organised themselves and refused to work for their lords, arguing that, according to the Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manus ...

, they were exempted from such requests. The workers made unsuccessful appeals to the law courts and the King. There were also widespread urban tensions, particularly in London, where John of Gaunt narrowly escaped being lynched. The troubles increased again in 1380, with protests and disturbances across northern England and in the western towns of Shrewsbury and Bridgwater. An uprising occurred in York, during which John de Gisborne, the city's mayor, was removed from office, and fresh tax riots followed in early 1381. There was a great storm in England during May 1381, which many felt to prophesy future change and upheaval, adding further to the disturbed mood.

Events

Outbreak of revolt

Essex and Kent

The revolt of 1381 broke out inEssex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and Grea ...

, following the arrival of John Bampton to investigate non-payment of the poll tax on 30 May. Bampton was a Member of Parliament, a Justice of the Peace and well-connected with royal circles. He based himself in Brentwood and summoned representatives from the neighbouring villages of Corringham, Fobbing

Fobbing is a small village and former civil parish in Thurrock, Essex, England and one of Thurrock's traditional (Church of England) parishes. It is located between Basildon and Corringham, and is also close to Stanford-le-Hope. In 1931 the pa ...

and Stanford-le-Hope to explain and make good the shortfalls on 1 June. The villagers appear to have arrived well-organised, and armed with old bows and sticks. Bampton first interrogated the people of Fobbing, whose representative, Thomas Baker, declared that his village had already paid their taxes, and that no more money would be forthcoming. When Bampton and two sergeants attempted to arrest Baker, violence broke out. Bampton escaped and retreated to London, but three of his clerks and several of the Brentwood townsfolk who had agreed to act as jurors were killed. Robert Bealknap

Sir Robert Belknap (died 19 January 1401) was a senior English judge.

Origins

Born about or before 1330, possibly in Kent or Wiltshire, England, he was the son of John Belknap, a lawyer, and his wife Alice.

Career

He is first mentioned in June ...

, the Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas

A court of common pleas is a common kind of court structure found in various common law jurisdictions. The form originated with the Court of Common Pleas at Westminster, which was created to permit individuals to press civil grievances against one ...

, who was probably already holding court in the area, was empowered to arrest and deal with the perpetrators.

By the next day, the revolt was rapidly growing. The villagers spread the news across the region, and John Geoffrey, a local bailiff, rode between Brentwood and

By the next day, the revolt was rapidly growing. The villagers spread the news across the region, and John Geoffrey, a local bailiff, rode between Brentwood and Chelmsford

Chelmsford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in the City of Chelmsford district in the county of Essex, England. It is the county town of Essex and one of three cities in the county, along with Southend-on-Sea and Colchester. It ...

, rallying support. On 4 June, the rebels gathered at Bocking, where their future plans seem to have been discussed. The Essex rebels, possibly a few thousand strong, advanced towards London, some probably travelling directly and others via Kent. One group, under the leadership of John Wrawe

John Wrawe (d. May 6, 1382) was a rebel leader during the English Peasants' Revolt. He was executed in 1382.

Details

At the start of the Peasants' Revolt in June 1381, John Wrawe, a former chaplain, marched north from Essex towards the neighbou ...

, a former chaplain, marched north towards the neighbouring county of Suffolk, with the intention of raising a revolt there.

Revolt also flared in neighbouring Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

. Sir Simon de Burley, a close associate of both Edward III and the young Richard, had claimed that a man in Kent, called Robert Belling, was an escaped serf from one of his estates. Burley sent two sergeants to Gravesend, where Belling was living, to reclaim him. Gravesend's local bailiffs and Belling tried to negotiate a solution under which Burley would accept a sum of money in return for dropping his case, but this failed and Belling was taken away to be imprisoned at Rochester Castle

Rochester Castle stands on the east bank of the River Medway in Rochester, Kent, South East England. The 12th-century keep or stone tower, which is the castle's most prominent feature, is one of the best preserved in England or France.

Situat ...

. A furious group of local people gathered at Dartford, possibly on 5 June, to discuss the matter. From there the rebels travelled to Maidstone

Maidstone is the largest town in Kent, England, of which it is the county town. Maidstone is historically important and lies 32 miles (51 km) east-south-east of London. The River Medway runs through the centre of the town, linking it wi ...

, where they stormed the gaol, and then on to Rochester

Rochester may refer to:

Places Australia

* Rochester, Victoria

Canada

* Rochester, Alberta

United Kingdom

*Rochester, Kent

** City of Rochester-upon-Medway (1982–1998), district council area

** History of Rochester, Kent

** HM Prison ...

on 6 June. Faced by the angry crowds, the constable in charge of Rochester Castle surrendered it without a fight and Belling was freed.

Some of the Kentish crowds now dispersed, but others continued. From this point, they appear to have been led by Wat Tyler

Wat Tyler (c. 1320/4 January 1341 – 15 June 1381) was a leader of the 1381 Peasants' Revolt in England. He led a group of rebels from Canterbury to London to oppose the institution of a poll tax and to demand economic and social reforms. Wh ...

, whom the ''Anonimalle Chronicle'' suggests was elected their leader at a large gathering at Maidstone on 7 June.; Relatively little is known about Tyler's former life; chroniclers suggest that he was from Essex, had served in France as an archer and was a charismatic and capable leader. Several chroniclers believe that he was responsible for shaping the political aims of the revolt. Some also mention a Jack Straw

John Whitaker Straw (born 3 August 1946) is a British politician who served in the Cabinet from 1997 to 2010 under the Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. He held two of the traditional Great Offices of State, as Home Secretary ...

as a leader among the Kentish rebels during this phase in the revolt, but it is uncertain if this was a real person, or a pseudonym for Wat Tyler or John Wrawe.

Tyler and the Kentish men advanced to Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of ...

, entering the walled city

A defensive wall is a fortification usually used to protect a city, town or other settlement from potential aggressors. The walls can range from simple palisades or earthworks to extensive military fortifications with towers, bastions and gates ...

and castle without resistance on 10 June. The rebels deposed the absent Archbishop of Canterbury, Sudbury, and made the cathedral monks swear loyalty to their cause. They attacked properties in the city with links to the hated royal council, and searched the city for suspected enemies, dragging the suspects out of their houses and executing them. The city gaol was opened and the prisoners freed. Tyler then persuaded a few thousand of the rebels to leave Canterbury and advance with him on London the next morning.

March on the capital

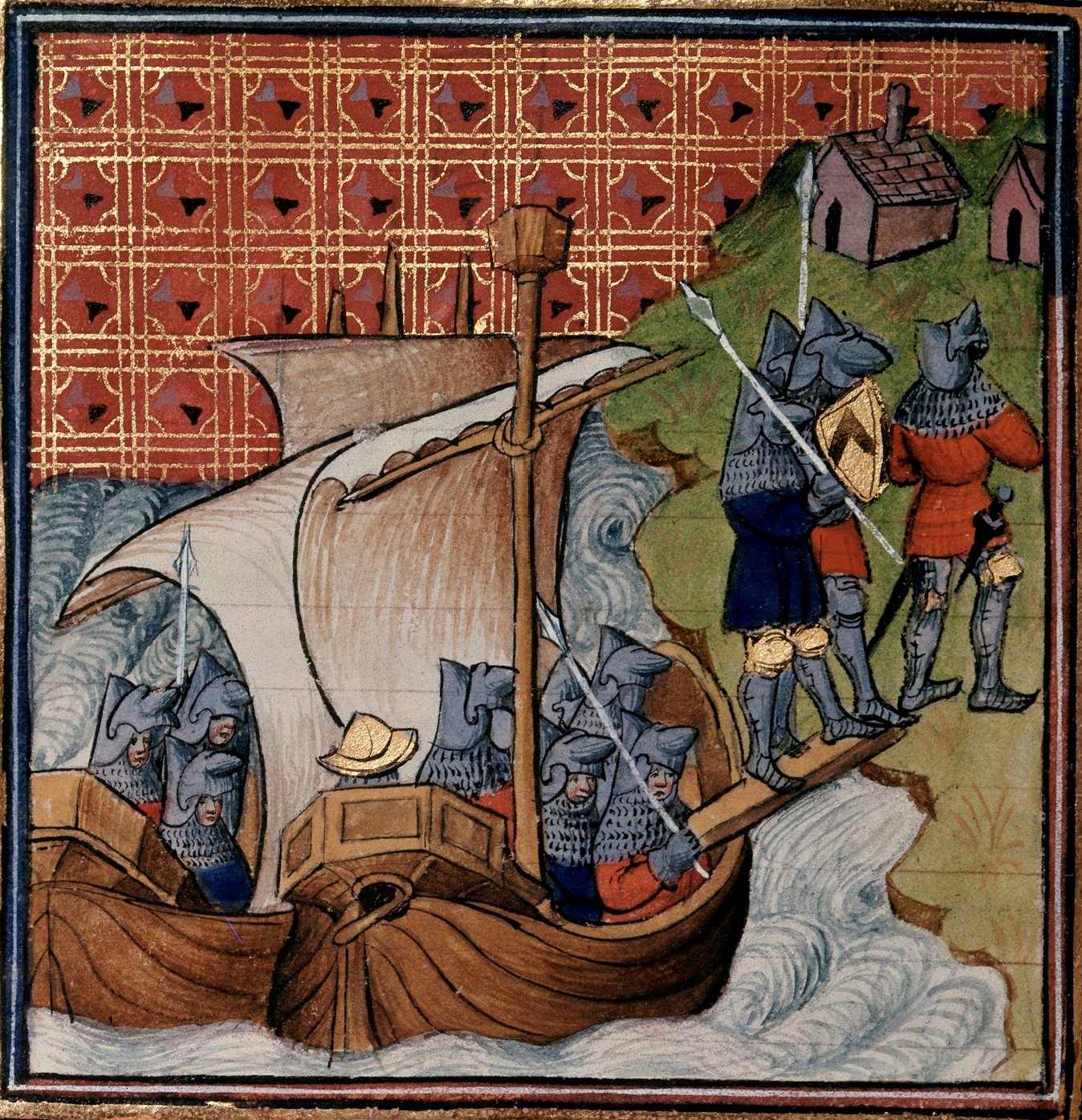

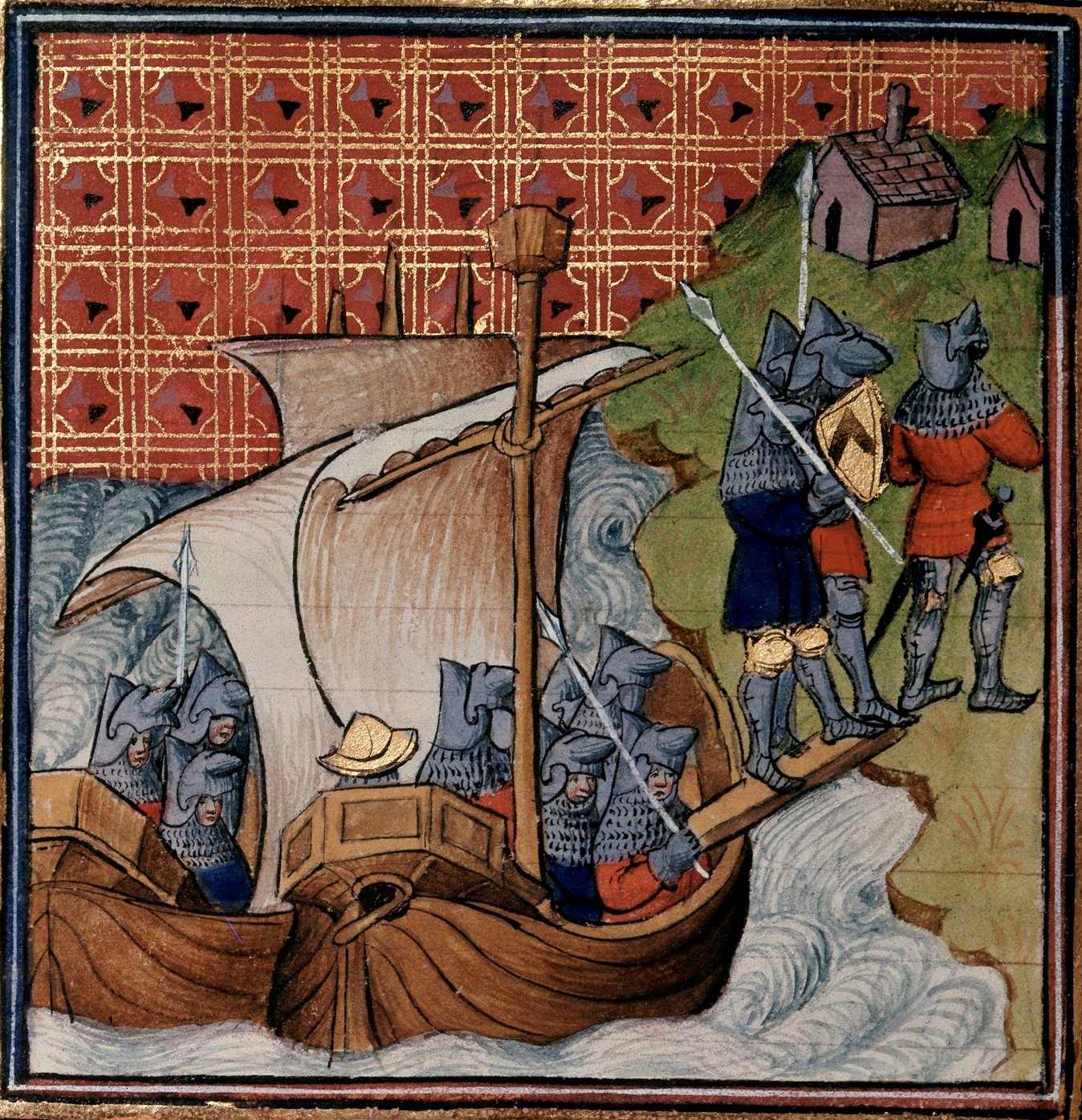

The Kentish advance on London appears to have been coordinated with the movement of the rebels in Essex, Suffolk and

The Kentish advance on London appears to have been coordinated with the movement of the rebels in Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

. Their forces were armed with weapons including sticks, battle axes, old swords and bows. Along their way, they encountered Lady Joan, the King's mother, who was travelling back to the capital to avoid being caught up in the revolt; she was mocked but otherwise left unharmed. The Kentish rebels reached Blackheath, just south-east of the capital, on 12 June.

Word of the revolt reached the King at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

on the night of 10 June. He travelled by boat down the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

to London the next day, taking up residence in the powerful fortress of the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

for safety, where he was joined by his mother, Archbishop Sudbury, the Lord High Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State in ...

Sir Robert Hales

Sir Robert Hales ( – 14 June 1381) was Grand Prior of the Knights Hospitaller of England, Lord High Treasurer, and Admiral of the West. He was killed in the Peasants' Revolt.

Career

In 1372 Robert Hales became the Lord/Grand Prior of th ...

, the Earls of Arundel, Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

and Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined with Leamington Spa and Whi ...

and several other senior nobles. A delegation, headed by Thomas Brinton, the Bishop of Rochester, was sent out from London to negotiate with the rebels and persuade them to return home.

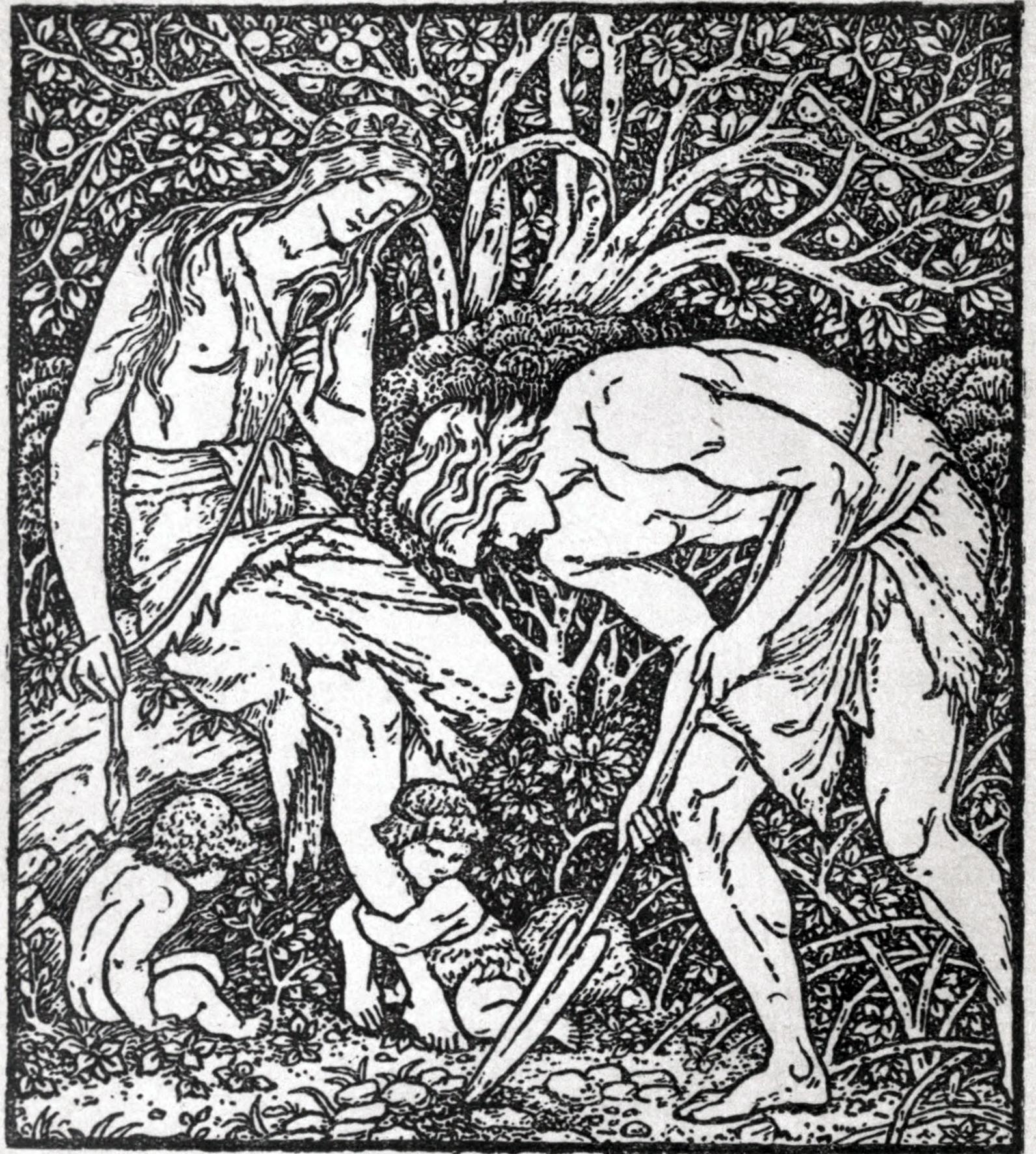

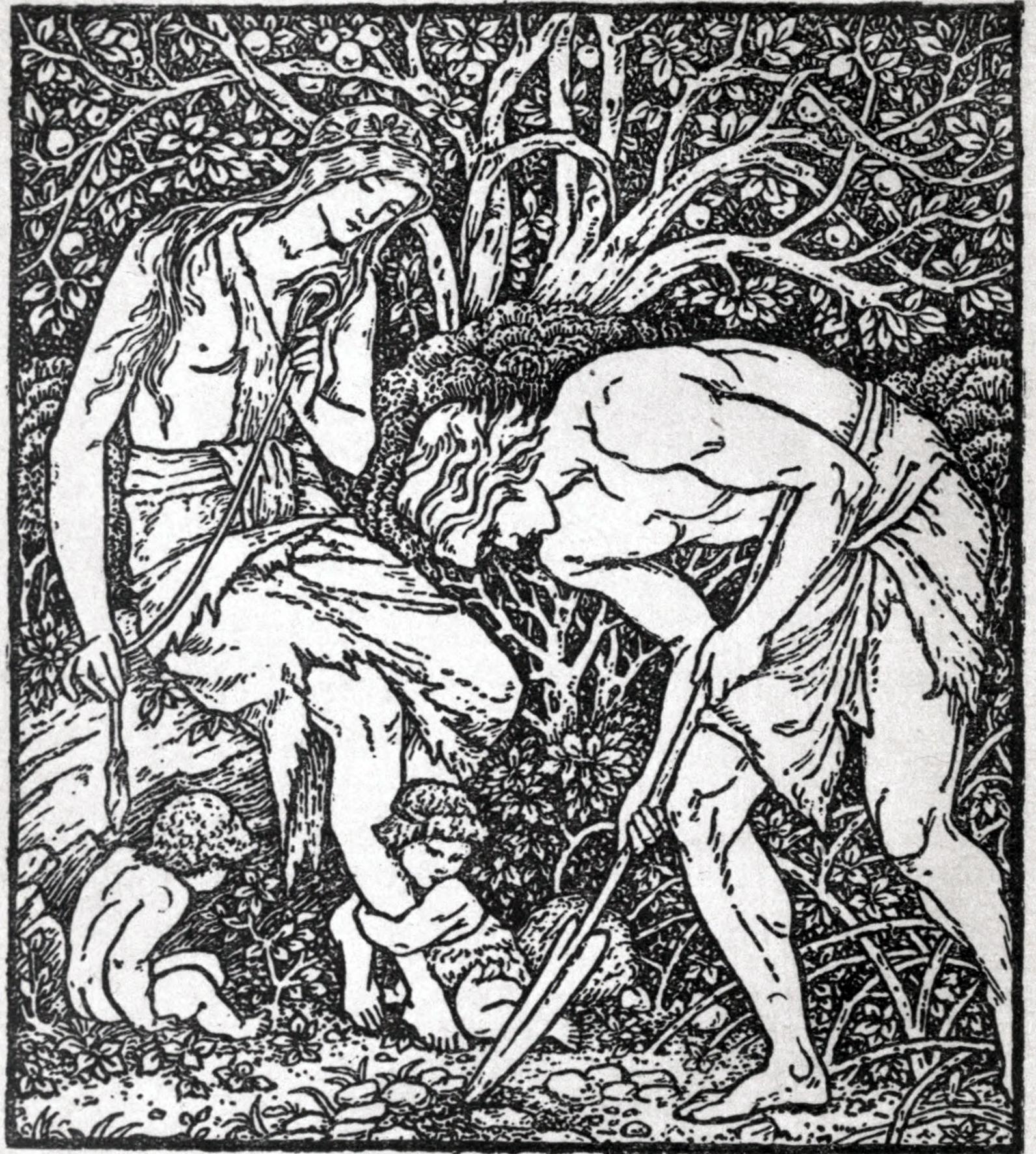

At Blackheath, John Ball gave a famous sermon to the assembled Kentishmen. Ball was a well-known priest and radical preacher from Kent, who was by now closely associated with Tyler. Chroniclers' accounts vary as to how he came to be involved in the revolt; he may have been released from Maidstone gaol by the crowds, or might have been already at liberty when the revolt broke out. Ball rhetorically asked the crowds "When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then a gentleman?" and promoted the rebel slogan "With King Richard and the true commons of England". The phrases emphasised the rebel opposition to the continuation of serfdom and to the hierarchies of the Church and State that separated the subject from the King, while stressing that they were loyal to the monarchy and, unlike the King's advisers, were "true" to Richard. The rebels rejected proposals from the Bishop of Rochester that they should return home, and instead prepared to march on.

Discussions took place in the Tower of London about how to deal with the revolt. The King had only a few troops at hand, in the form of the castle's garrison, his immediate bodyguard and, at most, several hundred soldiers. Many of the more experienced military commanders were in France, Ireland and Germany, and the nearest major military force was in the north of England, guarding against a potential Scottish invasion. Resistance in the provinces was also complicated by English law, which stated that only the King could summon local militias or lawfully execute rebels and criminals, leaving many local lords unwilling to attempt to suppress the uprisings on their own authority.

Since the Blackheath negotiations had failed, the decision was taken that the King himself should meet the rebels, at Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

, on the south side of the Thames. Guarded by four barges of soldiers, Richard sailed from the Tower on the morning of 13 June, where he was met on the other side by the rebel crowds. The negotiations failed, as Richard was unwilling to come ashore and the rebels refused to enter discussions until he did. Richard returned across the river to the Tower.;

Events in London

Entry to the city

The rebels began to cross from Southwark onto London Bridge on the afternoon of 13 June. The defences on London Bridge were opened from the inside, either in sympathy for the rebel cause or out of fear, and the rebels advanced into the city. At the same time, the rebel force from Essex made its way towards

The rebels began to cross from Southwark onto London Bridge on the afternoon of 13 June. The defences on London Bridge were opened from the inside, either in sympathy for the rebel cause or out of fear, and the rebels advanced into the city. At the same time, the rebel force from Essex made its way towards Aldgate

Aldgate () was a gate in the former defensive wall around the City of London. It gives its name to Aldgate High Street, the first stretch of the A11 road, which included the site of the former gate.

The area of Aldgate, the most common use of ...

on the north side of the city. The rebels swept west through the centre of the city, and Aldgate was opened to let the rest of the rebels in.

The Kentish rebels had assembled a wide-ranging list of people whom they wanted the King to hand over for execution. It included national figures, such as John of Gaunt, Archbishop Sudbury and Hales; other key members of the royal council; officials, such as Belknap and Bampton who had intervened in Kent; and other hated members of the wider royal circle. When they reached the Marshalsea Prison in Southwark, they tore it apart. By now the Kent and Essex rebels had been joined by many rebellious Londoners. The Fleet

Fleet may refer to:

Vehicles

*Fishing fleet

*Naval fleet

*Fleet vehicles, a pool of motor vehicles

*Fleet Aircraft, the aircraft manufacturing company

Places

Canada

* Fleet, Alberta, Canada, a hamlet

England

* The Fleet Lagoon, at Chesil Beach ...

and Newgate Prisons were attacked by the crowds, and the rebels also targeted houses belonging to Flemish immigrants.

On the north side of London, the rebels approached Smithfield and Clerkenwell Priory

Clerkenwell Priory was a priory of the Monastic Order of the Knights Hospitallers of St John of Jerusalem, in Clerkenwell, London. Run according to the Augustinian rule, it was the residence of the Hospitallers' Grand Prior in England, and was ...

, the headquarters of the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

which was headed by Hales. The priory was destroyed, along with the nearby manor. Heading west along Fleet Street, the rebels attacked the Temple, a complex of legal buildings and offices owned by the Hospitallers. The contents, books and paperwork were brought out and burned in the street, and the buildings systematically demolished. Meanwhile, John Fordham

John Fordham (died 1425) was Bishop of Durham and Bishop of Ely.

Fordham was keeper of the privy seal of Prince Richard from 1376 to 1377 and Dean of Wells before being named Lord Privy Seal in June 1377. He held that office until December 1381 ...

, the Keeper of the Privy Seal and one of the men on the rebels' execution list, narrowly escaped when the crowds ransacked his accommodation but failed to notice he was still in the building.

Next to be attacked along Fleet Street was the Savoy Palace

The Savoy Palace, considered the grandest nobleman's townhouse of medieval London, was the residence of prince John of Gaunt until it was destroyed during rioting in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. The palace was on the site of an estate given to ...

, a huge, luxurious building belonging to John of Gaunt. According to the chronicler Henry Knighton

Henry Knighton (or Knyghton) (died c. 1396, in England) was an Augustinian canon at the abbey of St Mary of the Meadows, Leicester, England, and an ecclesiastical historian (chronicler). He wrote a history of England from the Norman conquest ...

it contained "such quantities of vessels and silver plate, without counting the parcel-gilt and solid gold, that five carts would hardly suffice to carry them"; official estimates placed the value of the contents at around £10,000. The interior was systematically destroyed by the rebels, who burnt the soft furnishings, smashed the precious metal work, crushed the gems, set fire to the Duke's records and threw the remains into the Thames and the city drains. Almost nothing was stolen by the rebels, who declared themselves to be "zealots for truth and justice, not thieves and robbers". The remains of the building were then set alight. In the evening, rebel forces gathered outside the Tower of London, from where the King watched the fires burning across the city.

Taking the Tower of London

Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

and opening the Westminster gaol. They then moved back into central London, setting fire to more buildings and storming Newgate Prison. The hunt for Flemings continued, and those with Flemish-sounding accents were killed, including the royal adviser, Richard Lyons. In one city ward

Ward may refer to:

Division or unit

* Hospital ward, a hospital division, floor, or room set aside for a particular class or group of patients, for example the psychiatric ward

* Prison ward, a division of a penal institution such as a pris ...

, the bodies of 40 executed Flemings were piled up in the street, and at the Church of St Martin Vintry

St Martin Vintry was a parish church in the Vintry ward of the City of London, England. It was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and never rebuilt.

History

The church stood at what is now the junction of Queen Street and Upper Thames ...

, popular with the Flemish, 35 of the community were killed. Historian Rodney Hilton

Rodney Howard Hilton (17 November 1916 – 7 June 2002) was an English Marxist historian of the late medieval period and the transition from feudalism to capitalism.

Biography

Hilton was born in Middleton in Lancashire. He studied at Ma ...

argues that these attacks may have been coordinated by the weavers' guilds of London, who were commercial competitors of the Flemish weavers.

Isolated inside the Tower, the royal government was in a state of shock at the turn of events. The King left the castle that morning and made his way to negotiate with the rebels at Mile End

Mile End is a district of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in the East End of London, England, east-northeast of Charing Cross. Situated on the London-to-Colchester road, it was one of the earliest suburbs of London. It became part of the m ...

in east London, taking only a very small bodyguard with him. The King left Sudbury and Hales behind in the Tower, either for their own safety or because Richard had decided it would be safer to distance himself from his unpopular ministers. Along the way, several Londoners accosted the King to complain about alleged injustices.

It is uncertain who spoke for the rebels at Mile End, and Wat Tyler may not have been present on this occasion, but they appear to have put forward their various demands to the King, including the surrender of the hated officials on their lists for execution; the abolition of serfdom and unfree tenure; "that there should be no law within the realm save the law of Winchester", and a general amnesty for the rebels. It is unclear precisely what was meant by the law of Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

, but it probably referred to the rebel ideal of self-regulating village communities. Richard issued charters announcing the abolition of serfdom, which immediately began to be disseminated around the country. He declined to hand over any of his officials, apparently instead promising that he would personally implement any justice that was required.

While Richard was at Mile End, the Tower was taken by the rebels. This force, separate from those operating under Tyler at Mile End, approached the castle, possibly in the late morning. The gates were open to receive Richard on his return and a crowd of around 400 rebels entered the fortress, encountering no resistance, possibly because the guards were terrified by them.

Once inside, the rebels began to hunt down their key targets, and found Archbishop Sudbury and Robert Hales in the chapel of the White Tower. Along with William Appleton, John of Gaunt's physician, and John Legge, a royal sergeant, they were taken out to Tower Hill

Tower Hill is the area surrounding the Tower of London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is infamous for the public execution of high status prisoners from the late 14th to the mid 18th century. The execution site on the higher grou ...

and beheaded. Their heads were paraded around the city, before being affixed to London Bridge. The rebels found John of Gaunt's son, the future Henry IV, and were about to execute him as well, when John Ferrour, one of the royal guards, successfully interceded on his behalf. The rebels also discovered Lady Joan and Joan Holland

Lady Joan Holland (ca. 1380–12 April 1434) was the third daughter of Thomas Holland, 2nd Earl of Kent, and Lady Alice FitzAlan. She married four times. Her first husband was a duke, and the following three were barons. All of her marria ...

, Richard's sister, in the castle but let them go unharmed after making fun of them. The castle was thoroughly looted of armour and royal paraphernalia.

In the aftermath of the attack, Richard did not return to the Tower but instead travelled from Mile End to the Great Wardrobe, one of his royal houses in Blackfriars Blackfriars, derived from Black Friars, a common name for the Dominican Order of friars, may refer to:

England

* Blackfriars, Bristol, a former priory in Bristol

* Blackfriars, Canterbury, a former monastery in Kent

* Blackfriars, Gloucester, a f ...

, part of south-west London. There he appointed the military commander Richard FitzAlan, the Earl of Arundel

Earl of Arundel is a title of nobility in England, and one of the oldest extant in the English peerage. It is currently held by the Duke of Norfolk, and is used (along with the Earl of Surrey) by his heir apparent as a courtesy title. The e ...

, to replace Sudbury as Chancellor, and began to make plans to regain an advantage over the rebels the following day. Many of the Essex rebels now began to disperse, content with the King's promises, leaving Tyler and the Kentish forces the most significant faction in London. Tyler's men moved around the city that evening, seeking out and killing John of Gaunt's employees, foreigners and anyone associated with the legal system.

Smithfield

On 15 June the royal government and the remaining rebels, who were unsatisfied with the charters granted the previous day, agreed to meet at Smithfield, just outside the city walls. London remained in confusion, with various bands of rebels roaming the city independently. Richard prayed at Westminster Abbey, before setting out for the meeting in the late afternoon. The chroniclers' accounts of the encounter all vary on matters of detail, but agree on the broad sequence of events. The King and his party, at least 200 strong and including

On 15 June the royal government and the remaining rebels, who were unsatisfied with the charters granted the previous day, agreed to meet at Smithfield, just outside the city walls. London remained in confusion, with various bands of rebels roaming the city independently. Richard prayed at Westminster Abbey, before setting out for the meeting in the late afternoon. The chroniclers' accounts of the encounter all vary on matters of detail, but agree on the broad sequence of events. The King and his party, at least 200 strong and including men-at-arms

A man-at-arms was a soldier of the High Medieval to Renaissance periods who was typically well-versed in the use of arms and served as a fully-armoured heavy cavalryman. A man-at-arms could be a knight, or other nobleman, a member of a knig ...

, positioned themselves outside St Bartholomew's Priory to the east of Smithfield, and the thousands of rebels massed along the western end.

Richard probably called Tyler forwards from the crowd to meet him, and Tyler greeted the King with what the royal party considered excessive familiarity, terming Richard his "brother" and promising him his friendship. Richard queried why Tyler and the rebels had not yet left London following the signing of the charters the previous day, but this brought an angry rebuke from Tyler, who requested that a further charter be drawn up. The rebel leader rudely demanded refreshment and, once this had been provided, attempted to leave.

An argument then broke out between Tyler and some of the royal servants. The Lord Mayor of London, William Walworth

Sir William Walworth (died 1385) was an English nobleman and politician who was twice Lord Mayor of London (1374–75 and 1380–81). He is best known for killing Wat Tyler during the Peasants' Revolt in 1381.

Political career

His family ca ...

, stepped forward to intervene, Tyler made some motion towards the King, and the royal soldiers leapt in. Either Walworth or Richard ordered Tyler to be arrested, Tyler attempted to attack the Mayor, and Walworth responded by stabbing Tyler. Ralph Standish, a royal squire

In the Middle Ages, a squire was the shield- or armour-bearer of a knight.

Use of the term evolved over time. Initially, a squire served as a knight's apprentice. Later, a village leader or a lord of the manor might come to be known as a " ...

, then repeatedly stabbed Tyler with his sword, mortally injuring him.

The situation was now precarious and violence appeared likely as the rebels prepared to unleash a volley of arrows. Richard rode forward towards the crowd and persuaded them to follow him away from Smithfield, to Clerkenwell Fields, defusing the situation. Walworth meanwhile began to regain control of the situation, backed by reinforcements from the city. Tyler's head was cut off and displayed on a pole and, with their leader dead and the royal government now backed by the London militia, the rebel movement began to collapse. Richard promptly knighted Walworth and his leading supporters for their services.

Wider revolt

Eastern England

While the revolt was unfolding in London, John Wrawe led his force into Suffolk. Wrawe had considerable influence over the development of the revolt across eastern England, where there may have been almost as many rebels as in the London revolt. The authorities put up very little resistance to the revolt: the major nobles failed to organise defences, key fortifications fell easily to the rebels and the local militias were not mobilised. As in London and the south-east, this was in part due to the absence of key military leaders and the nature of English law, but any locally recruited men might also have proved unreliable in the face of a popular uprising.

On 12 June, Wrawe attacked Sir Richard Lyons' property at Overhall, advancing on to

While the revolt was unfolding in London, John Wrawe led his force into Suffolk. Wrawe had considerable influence over the development of the revolt across eastern England, where there may have been almost as many rebels as in the London revolt. The authorities put up very little resistance to the revolt: the major nobles failed to organise defences, key fortifications fell easily to the rebels and the local militias were not mobilised. As in London and the south-east, this was in part due to the absence of key military leaders and the nature of English law, but any locally recruited men might also have proved unreliable in the face of a popular uprising.

On 12 June, Wrawe attacked Sir Richard Lyons' property at Overhall, advancing on to Cavendish

Cavendish may refer to:

People

* The House of Cavendish, a British aristocratic family

* Margaret Cavendish (1623–1673), British poet, philosopher, and scientist

* Cavendish (author) (1831–1899), pen name of Henry Jones, English auth ...

and Bury St Edmunds

Bury St Edmunds (), commonly referred to locally as Bury, is a historic market town, market, cathedral town and civil parish in Suffolk, England.OS Explorer map 211: Bury St.Edmunds and Stowmarket Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – ...

in west Suffolk the next day, gathering further support as they went. John Cambridge, the Prior of the wealthy Bury St Edmunds Abbey

The Abbey of Bury St Edmunds was once among the richest Benedictine monasteries in England, until the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539. It is in the town that grew up around it, Bury St Edmunds in the county of Suffolk, England. It was ...

, was disliked in the town, and Wrawe allied himself with the townspeople and stormed the abbey. The Prior escaped, but was found two days later and beheaded. A small band of rebels marched north to Thetford

Thetford is a market town and civil parish in the Breckland District of Norfolk, England. It is on the A11 road between Norwich and London, just east of Thetford Forest. The civil parish, covering an area of , in 2015 had a population of 24,340 ...

to extort protection money

A protection racket is a type of racket and a scheme of organized crime perpetrated by a potentially hazardous organized crime group that generally guarantees protection outside the sanction of the law to another entity or individual from viol ...

from the town, and another group tracked down Sir John Cavendish

Sir John Cavendish (c. 1346 – 15 June 1381) was an English judge and politician from Cavendish, Suffolk, England. He and the village gave the name Cavendish to the aristocratic families of the Dukedoms of Devonshire, Newcastle Newcastle us ...

, the Chief Justice of the King's Bench

Chief may refer to:

Title or rank

Military and law enforcement

* Chief master sergeant, the ninth, and highest, enlisted rank in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force

* Chief of police, the head of a police department

* Chief of the boa ...

and Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

of the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world's third oldest surviving university and one of its most pr ...

. Cavendish was caught in Lakenheath

Lakenheath is a village and civil parish in the West Suffolk district of Suffolk in eastern England. It has a population of 4,691 according to the 2011 Census, and is situated close to the county boundaries of both Norfolk and Cambridgeshire, ...

and killed. John Battisford and Thomas Sampson independently led a revolt near Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line r ...

on 14 June. They took the town without opposition and looted the properties of the archdeacon

An archdeacon is a senior clergy position in the Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, St Thomas Christians, Eastern Orthodox churches and some other Christian denominations, above that o ...

and local tax officials. The violence spread out further, with attacks on many properties and the burning of the local court records. One official, Edmund Lakenheath, was forced to flee from the Suffolk coast by boat.

Revolt began to stir in St Albans

St Albans () is a cathedral city in Hertfordshire, England, east of Hemel Hempstead and west of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, Hatfield, north-west of London, south-west of Welwyn Garden City and south-east of Luton. St Albans was the first major ...

in Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

late on 13 June, when news broke of the events in London. There had been long-running disagreements in St Albans between the town and the local abbey

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christian monks and nuns.

The conce ...

, which had extensive privileges in the region. On 14 June, protesters met with the Abbot, Thomas de la Mare, and demanded their freedom from the abbey. A group of townsmen under the leadership of William Grindecobbe

William Grindecobbe or William Grindcobbe was one of the peasant leaders during the English Peasants' Revolt of 1381. A Townsman of St Albans, he was a substantial property owner there and has been described as a 'hero' of the revolt.

Life

His ...

travelled to London, where they appealed to the King for the rights of the abbey to be abolished. Wat Tyler, then still in control of the city, granted them authority in the meantime to take direct action against the abbey. Grindecobbe and the rebels returned to St Albans, where they found the Prior had already fled. The rebels broke open the abbey gaol, destroyed the fences marking out the abbey lands and burnt the abbey records in the town square. They then forced Thomas de la Mare to surrender the abbey's rights in a charter on 16 June. The revolt against the abbey spread out over the next few days, with abbey property and financial records being destroyed across the county.

Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire (abbreviated Cambs.) is a Counties of England, county in the East of England, bordering Lincolnshire to the north, Norfolk to the north-east, Suffolk to the east, Essex and Hertfordshire to the south, and Bedfordshire and North ...

, led by elements of Wrawe's Suffolk rebellion and some local men, such as John Greyston, who had been involved in the events in London and had returned to his home county to spread the revolt, and Geoffrey Cobbe and John Hanchach, members of the local gentry. The University of Cambridge, staffed by priests and enjoying special royal privileges, was widely hated by the other inhabitants of the town. A revolt backed by the Mayor of Cambridge broke out with the university as its main target. The rebels ransacked Corpus Christi College, which had connections to John of Gaunt, and the University's church, and attempted to execute the University bedel

The bedel (from medieval Latin ''pedellus'' or ''bidellus'', occasionally ''bidellus generalis'', from Old High German ''bital'', ''pital'', "the one who invites, calls"; cognate with beadle) was, and is to some extent still, an administrative ...

, who escaped. The university's library and archives were burnt in the centre of the town, with one Margery Starre leading the mob in a dance to the rallying cry ''"Away with the learning of clerks, away with it!"

"Away with the learning of clerks, away with it!" was a rallying cry of rebellious townspeople during the Peasants' Revolt of 1381 in Cambridge, during which they sacked the university and official buildings and burnt legal documents and charters ...

'' while the documents burned. The next day, the university was forced to negotiate a new charter, giving up its royal privileges. Revolt then spread north from Cambridge toward Ely Ely or ELY may refer to:

Places Ireland

* Éile, a medieval kingdom commonly anglicised Ely

* Ely Place, Dublin, a street

United Kingdom

* Ely, Cambridgeshire, a cathedral city in Cambridgeshire, England

** Ely Cathedral

Ely Cathedral, formal ...

, where the gaol was opened and the local Justice of the Peace executed.

In Norfolk, the revolt was led by Geoffrey Litster, a weaver, and Sir Roger Bacon, a local lord with ties to the Suffolk rebels. Litster began sending out messengers across the county in a call to arms on 14 June, and isolated outbreaks of violence occurred. The rebels assembled on 17 June outside Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

and killed Sir Robert Salle, who was in charge of the city defences and had attempted to negotiate a settlement.; The people of the town then opened the gates to let the rebels in. They began looting buildings and killed Reginald Eccles, a local official. William de Ufford, the Earl of Suffolk

Earl of Suffolk is a title which has been created four times in the Peerage of England. The first creation, in tandem with the creation of the title of Earl of Norfolk, came before 1069 in favour of Ralph the Staller; but the title was forfei ...

fled his estates and travelled in disguise to London. The other leading members of the local gentry were captured and forced to play out the roles of a royal household, working for Litster. Violence spread out across the county, as gaols were opened, Flemish immigrants killed, court records burned, and property looted and destroyed.

Northern and western England

Revolts also occurred across the rest of England, particularly in the cities of the north, traditionally centres of political unrest. In the town of

Revolts also occurred across the rest of England, particularly in the cities of the north, traditionally centres of political unrest. In the town of Beverley

Beverley is a market and minster town and a civil parish in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England, of which it is the county town. The town centre is located south-east of York's centre and north-west of City of Hull.

The town is known fo ...

, violence broke out between the richer mercantile elite and the poorer townspeople during May. By the end of the month the rebels had taken power and replaced the former town administration with their own. The rebels attempted to enlist the support of Alexander Neville

Alexander Neville ( 1340–1392) was a late medieval prelate who served as Archbishop of York from 1374 to 1388.

Life

Born in about 1340, Alexander Neville was a younger son of Ralph Neville, 2nd Baron Neville de Raby and Alice de Audley. He ...

, the Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers th ...

, and in June forced the former town government to agree to arbitration through Neville. Peace was restored in June 1382 but tensions continued to simmer for many years.

Word of the troubles in the south-east spread north, slowed by the poor communication links of medieval England. In Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

, where John of Gaunt had a substantial castle

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars debate the scope of the word ''castle'', but usually consider it to be the private fortified r ...

, warnings arrived of a force of rebels advancing on the city from Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...