Peaceful nuclear explosion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Peaceful nuclear explosions (PNEs) are

Apart from their use as weapons,

Apart from their use as weapons,  The Qattara Depression Project was developed by Professor

The Qattara Depression Project was developed by Professor

/ref> Musk's specific plan would not be very feasible within the energy limitations of historically manufactured nuclear devices (ranging in kilotons of TNT-equivalent), therefore requiring major advancement for it to be considered. In part due to these problems, the physicist Alternatively, as nuclear detonations are presently somewhat limited in terms of ''demonstrated'' achievable yield, the use of an off-the-shelf nuclear explosive device could be employed to "nudge" a Martian- grazing comet toward a pole of the planet. Impact would be a much more efficient scheme to deliver the required energy, water vapor,

Alternatively, as nuclear detonations are presently somewhat limited in terms of ''demonstrated'' achievable yield, the use of an off-the-shelf nuclear explosive device could be employed to "nudge" a Martian- grazing comet toward a pole of the planet. Impact would be a much more efficient scheme to deliver the required energy, water vapor,

The discovery and synthesis of new

The discovery and synthesis of new  Soviet nuclear physicist and

Soviet nuclear physicist and

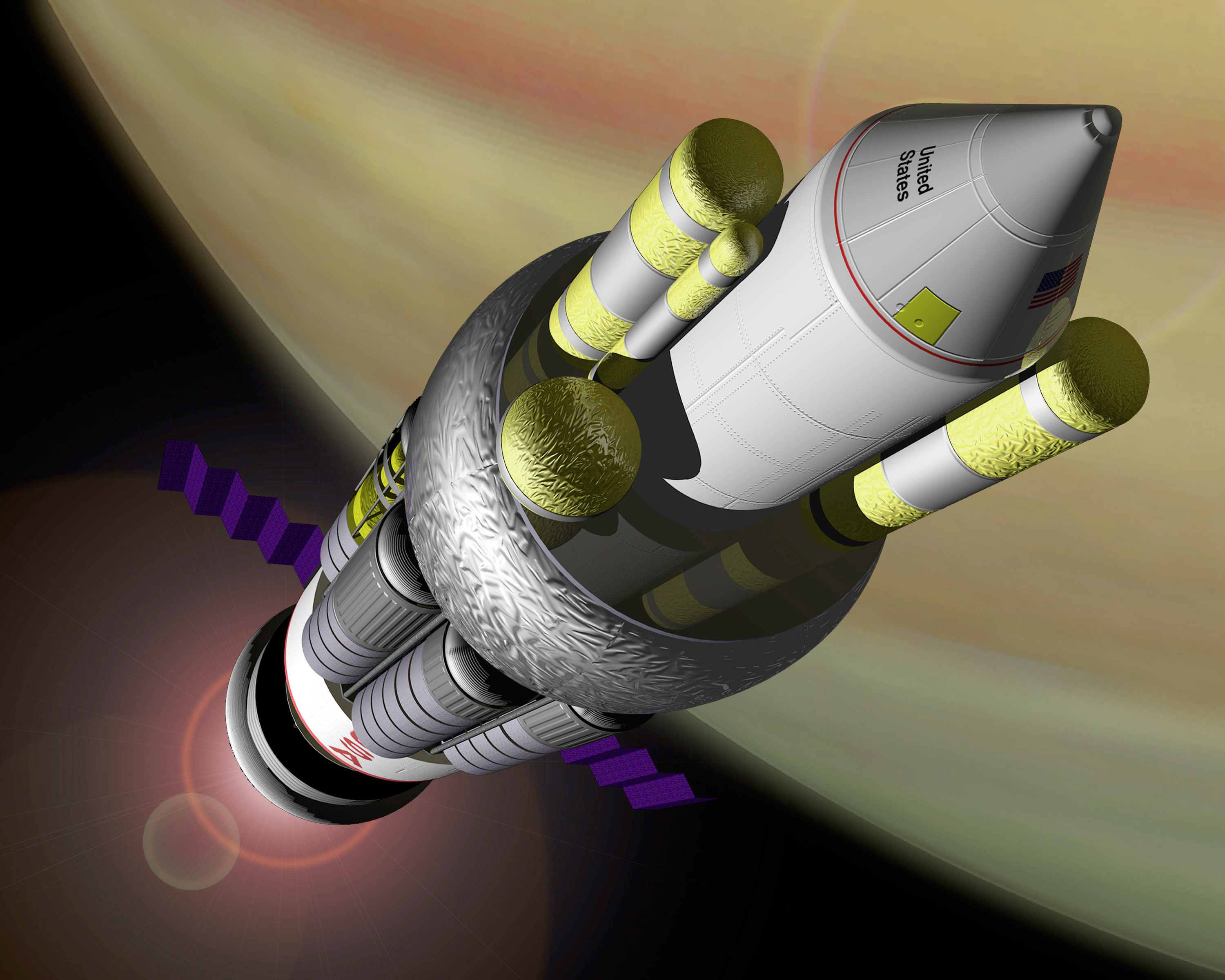

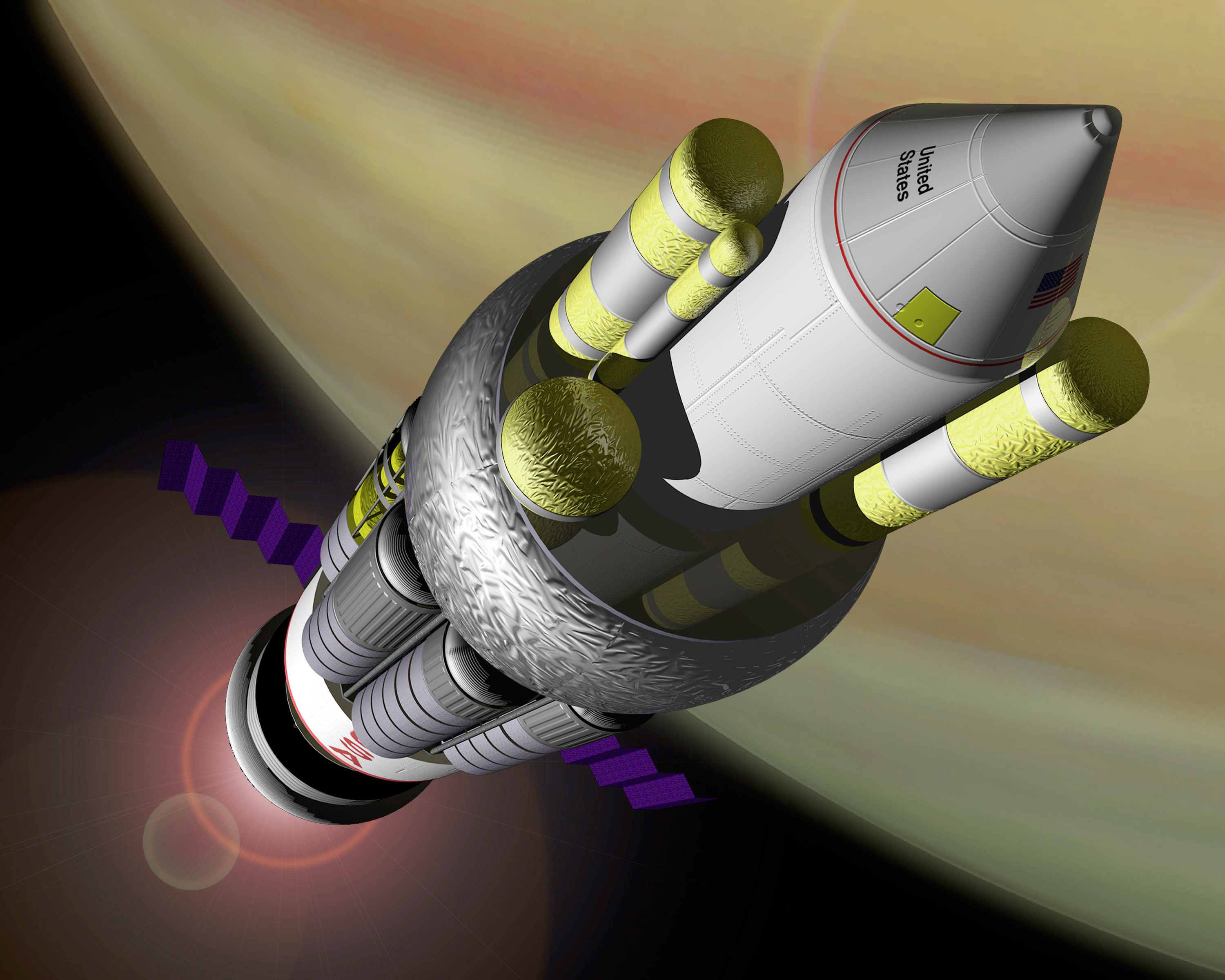

/ref> The ablation data collected for various materials and the distances the spheres were propelled, serve as the bedrock for the nuclear pulse propulsion study, Project Orion. The direct use of nuclear explosives, by using the impact of ablated propellant plasma from a nuclear

IAEA review of the 1968 book: The constructive uses of nuclear explosions by Edward Teller."The Containment of Underground Nuclear Explosions", Project Director Gregory E van der Vink, U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, OTA-ISC-414, (Oct 1989).

nuclear explosion

A nuclear explosion is an explosion that occurs as a result of the rapid release of energy from a high-speed nuclear reaction. The driving reaction may be nuclear fission or nuclear fusion or a multi-stage cascading combination of the two, tho ...

s conducted for non-military purposes. Proposed uses include excavation for the building of canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface flo ...

s and harbours

A harbor (American English), harbour (British English; see spelling differences), or haven is a sheltered body of water where ships, boats, and barges can be docked. The term ''harbor'' is often used interchangeably with ''port'', which is a ...

, electrical generation, the use of nuclear explosions to drive spacecraft, and as a form of wide-area fracking

Fracking (also known as hydraulic fracturing, hydrofracturing, or hydrofracking) is a well stimulation technique involving the fracturing of bedrock formations by a pressurized liquid. The process involves the high-pressure injection of "frac ...

. PNEs were an area of some research from the late 1950s into the 1980s, primarily in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

and Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

.

In the U.S., a series of tests were carried out under Project Plowshare

Project Plowshare was the overall United States program for the development of techniques to use nuclear explosives for peaceful construction purposes. The program was organized in June 1957 as part of the worldwide Atoms for Peace efforts. As ...

. Some of the ideas considered included blasting a new Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

, constructing the proposed Nicaragua Canal

The Nicaraguan Canal ( es, Canal de Nicaragua), formally the Nicaraguan Canal and Development Project (also referred to as the Nicaragua Grand Canal, or the Grand Interoceanic Canal) was a proposed shipping route through Nicaragua to connect th ...

, the use of underground explosions to create electricity (project PACER Project PACER, carried out at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) in the mid-1970s, explored the possibility of a fusion power system that would involve exploding small hydrogen bombs (fusion bombs)—or, as stated in a later proposal, fission bo ...

), and a variety of mining, geological, and radionuclide studies. The largest of the excavation tests was carried out in the Sedan nuclear test in 1962, which released large amounts of radioactive gas into the air. By the late 1960s, public opposition to Plowshare was increasing, and a 1970s study of the economics of the concepts suggested they had no practical use. Plowshare saw decreasing interest from the 1960s, and was officially cancelled in 1977.

The Soviet program started a few years after the U.S. efforts and explored many of the same concepts under their Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy

Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy (russian: Ядерные взрывы для народного хозяйства, Yadernyye vzryvy dlya narodnogo khozyaystva; sometimes referred to as ''Program #7'') was a Soviet program to investiga ...

program. The program was more extensive, eventually conducting 239 nuclear explosions. Some of these tests also released radioactivity, including a significant release of plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

into the groundwater and the polluting of an area near the Volga River

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchme ...

. A major part of the program in the 1970s and 80s was the use of very small bombs to produce shock waves as a seismic measuring tool, and as part of these experiments, two bombs were successfully used to seal blown-out oil wells. The program officially ended in 1988.

As part of ongoing arms control efforts, both programs came to be controlled by a variety of agreements. Most notable among these is the 1976 Treaty on Underground Nuclear Explosions for Peaceful Purposes (PNE Treaty). The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) is a multilateral treaty to ban nuclear weapons test explosions and any other nuclear explosions, for both civilian and military purposes, in all environments. It was adopted by the United Nati ...

of 1996 prohibits all nuclear explosions, regardless of whether they are for peaceful purposes or not. Since that time the topic has been raised several times, often as a method of asteroid impact avoidance

Asteroid impact avoidance comprises the methods by which near-Earth objects (NEO) on a potential collision course with Earth could be diverted away, preventing destructive impact events. An impact by a sufficiently large asteroid or other NEOs ...

.

Peaceful Nuclear Explosions Treaty

In the PNE Treaty, the signatories agreed: not to carry out any individual nuclear explosions having a yield exceeding 150 kilotonsTNT equivalent

TNT equivalent is a convention for expressing energy, typically used to describe the energy released in an explosion. The is a unit of energy defined by that convention to be , which is the approximate energy released in the detonation of a ...

; not to carry out any group explosion (consisting of a number of individual explosions) having an aggregate yield exceeding 1,500 kilotons; and not to carry out any group explosion having an aggregate yield exceeding 150 kilotons unless the individual explosions in the group could be identified and measured by agreed verification procedures. The parties also reaffirmed their obligations to comply fully with the Limited Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those conducted ...

of 1963.

The parties reserve the right to carry out nuclear explosions for peaceful purposes in the territory of another country if requested to do so, but only in full compliance with the yield limitations and other provisions of the PNE Treaty and in accord with the Non-Proliferation Treaty

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT, is an international treaty whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote cooperation ...

.

Articles IV and V of the PNE Treaty set forth the agreed verification arrangements. In addition to the use of national technical means, the treaty states that information and access to sites of explosions will be provided by each side, and includes a commitment not to interfere with verification means and procedures.

The protocol to the PNE Treaty sets forth the specific agreed arrangements for ensuring that no weapon-related benefits precluded by the Threshold Test Ban Treaty

The Treaty on the Limitation of Underground Nuclear Weapon Tests, also known as the Threshold Test Ban Treaty (TTBT), was signed in July 1974 by the United States and Soviet Union. It establishes a nuclear "threshold" by prohibiting nuclear tests ...

are derived by carrying out a nuclear explosion used for peaceful purposes, including provisions for use of the hydrodynamic

In physics and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids— liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including '' aerodynamics'' (the study of air and other gases in motion) a ...

yield measurement method, seismic

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes and the propagation of elastic waves through the Earth or through other ...

monitoring, and on-site inspection.

The agreed statement that accompanies the treaty specifies that a "peaceful application" of an underground nuclear explosion would not include the developmental testing of any nuclear explosive.

United States: Operation Plowshare

Operation Plowshare

Project Plowshare was the overall United States program for the development of techniques to use nuclear explosives for peaceful construction purposes. The program was organized in June 1957 as part of the worldwide Atoms for Peace efforts. As ...

was the name of the U.S. program for the development of techniques to use nuclear explosive

A nuclear explosive is an explosive device that derives its energy from nuclear reactions. Almost all nuclear explosive devices that have been designed and produced are nuclear weapons intended for warfare.

Other, non-warfare, applications for nuc ...

s for peaceful purposes. The name was coined in 1961, taken from Micah

Micah (; ) is a given name.

Micah is the name of several people in the Hebrew Bible ( Old Testament), and means "Who is like God?" The name is sometimes found with theophoric extensions. Suffix theophory in '' Yah'' and in ''Yahweh'' results in ...

4:3 ("And he shall judge among the nations, and shall rebuke many people: and they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more"). Twenty-eight nuclear blasts were detonated between 1961 and 1973.

One of the first U.S. proposals for peaceful nuclear explosions that came close to being carried out was Project Chariot

Project Chariot was a 1958 US Atomic Energy Commission proposal to construct an artificial harbor at Cape Thompson on the North Slope of the U.S. state of Alaska by burying and detonating a string of nuclear devices.

History

The project o ...

, which would have used several hydrogen bombs to create an artificial harbor at Cape Thompson Cape Thompson is a headland on the Chukchi Sea coast of Alaska. It is located 26 miles (42 km) to the southeast of Point Hope, Arctic Slope. It is part of the Chukchi Sea unit of Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge.

Early Inui ...

, Alaska. It was never carried out due to concerns for the native populations and the fact that there was little potential use for the harbor to justify its risk and expense. There was also talk of using nuclear explosions to excavate a second Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

, as well as an alternative to the Suez Canal.

The largest excavation experiment took place in 1962 at the Department of Energy A Ministry of Energy or Department of Energy is a government department in some countries that typically oversees the production of fuel and electricity; in the United States, however, it manages nuclear weapons development and conducts energy-re ...

's Nevada Test Site

The Nevada National Security Site (N2S2 or NNSS), known as the Nevada Test Site (NTS) until 2010, is a United States Department of Energy (DOE) reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about 65 miles (105 km) northwest of the ...

. The Sedan nuclear test carried out as part of Operation Storax

Operation Storax was a series of 47 nuclear tests conducted by the United States in 1962–1963 at the Nevada Test Site. These tests followed the ''Operation Fishbowl'' series and preceded the ''Operation Roller Coaster'' series.

British test ...

displaced 12 million tons of earth, creating the largest man-made crater in the world, generating a large nuclear fallout

Nuclear fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and the shock wave has passed. It commonly refers to the radioac ...

over Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a state in the Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the 7th-most extensive, ...

and Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

. Three tests were conducted in order to stimulate natural gas production, but the effort was abandoned as impractical because of cost and radioactive contamination

Radioactive contamination, also called radiological pollution, is the deposition of, or presence of radioactive substances on surfaces or within solids, liquids, or gases (including the human body), where their presence is unintended or undesirab ...

of the gas.

There were many negative impacts from Project Plowshare's 27 nuclear explosions. For example, the Project Gasbuggy

Project Gasbuggy was an underground nuclear detonation carried out by the United States Atomic Energy Commission on December 10, 1967 in rural northern New Mexico. It was part of Operation Plowshare, a program designed to find peaceful uses for ...

site, located east of Farmington

Farmington may refer to:

Places Canada

*Farmington, British Columbia

* Farmington, Nova Scotia (disambiguation)

United States

*Farmington, Arkansas

*Farmington, California

*Farmington, Connecticut

*Farmington, Delaware

* Farmington, Georgia

* ...

, New Mexico, still contains nuclear contamination from a single subsurface blast in 1967. Other consequences included blighted land, relocated communities, tritium

Tritium ( or , ) or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life about 12 years. The nucleus of tritium (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of ...

-contaminated water, radioactivity, and fallout from debris being hurled high into the atmosphere. These were ignored and downplayed until the program was terminated in 1977, due in large part to public opposition, after $770 million had been spent on the project..

Soviet Union: Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy

TheSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

conducted a much more vigorous program of 239 nuclear tests, some with multiple devices, between 1965 and 1988 under the auspices of Program No. 6—Employment of Nuclear Explosive Technologies in the Interests of National Economy and Program No. 7—Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy

Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy (russian: Ядерные взрывы для народного хозяйства, Yadernyye vzryvy dlya narodnogo khozyaystva; sometimes referred to as ''Program #7'') was a Soviet program to investiga ...

.

The initial program was patterned on the U.S. version, with the same basic concepts being studied. One test, Chagan test in January 1965, has been described as a "near clone" of the U.S. Sedan shot. Like Sedan, Chagan also resulted in a massive plume of radioactive material being blown high into the atmosphere, with an estimated 20% of the fission products with it. Detection of the plume over Japan led to accusations by the U.S. that the Soviets had carried out an above-ground test in violation of the Partial Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those conducted ...

, but these charges were later dropped.

The later, and more extensive, "Deep Seismic Sounding" Program focused on the use of much smaller explosions for various geological uses. Some of these tests are considered to be operational, not purely experimental. These included the use of peaceful nuclear explosions to create deep seismic

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes and the propagation of elastic waves through the Earth or through other ...

profiles. Compared to the usage of conventional explosives or mechanical methods, nuclear explosions allow the collection of longer seismic profiles (up to several thousand kilometres).

Alexey Yablokov

''Chernobyl: Consequences of the Catastrophe for People and the Environment'' is a translation of a 2007 Russian publication by Alexey V. Yablokov, Vassily B. Nesterenko, and Alexey V. Nesterenko, edited by Janette D. Sherman-Nevinger, and ori ...

has stated that all PNE technologies have non-nuclear alternatives and that many PNEs actually caused nuclear disasters.

Reports on the successful Soviet use of nuclear explosions in extinguishing out-of-control gas well fires were widely cited in United States policy discussions of options for stopping the 2010 Gulf of Mexico Deepwater Horizon oil spill

The ''Deepwater Horizon'' oil spill (also referred to as the "BP oil spill") was an industrial disaster that began on 20 April 2010 off of the coast of the United States in the Gulf of Mexico on the BP-operated Macondo Prospect, considere ...

.

Other nations

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

at one time considered manufacturing nuclear explosives for civil engineering purposes. In the early 1970s a feasibility study was conducted for a project to build a canal from the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

to the Qattara Depression

The Qattara Depression ( ar, منخفض القطارة, Munḫafaḍ al-Qaṭṭārah) is a depression in northwestern Egypt, specifically in the Matruh Governorate. The depression is part of the Western Desert of Egypt.

The Qattara Depressi ...

in the Western Desert of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

using nuclear demolition. This project proposed to use 213 devices, with yields of 1 to 1.5 megatons, detonated at depths of to build this canal for the purpose of producing hydroelectric power.

The Smiling Buddha

Operation Smiling BuddhaThis test has many code names. Civilian scientists called it "Operation Smiling Buddha" and the Indian Army referred to it as ''Operation Happy Krishna''. According to United States Military Intelligence, ''Operation H ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

's first explosive nuclear device, was described by the Indian Government

The Government of India (ISO: ; often abbreviated as GoI), known as the Union Government or Central Government but often simply as the Centre, is the national government of the Republic of India, a federal democracy located in South Asia, ...

as a peaceful nuclear explosion.

In Australia, nuclear blasting was proposed as a way of mining iron ore in the Pilbara

The Pilbara () is a large, dry, thinly populated region in the north of Western Australia. It is known for its Aboriginal peoples; its ancient landscapes; the red earth; and its vast mineral deposits, in particular iron ore. It is also a g ...

.

Civil engineering and energy production

Apart from their use as weapons,

Apart from their use as weapons, nuclear explosive

A nuclear explosive is an explosive device that derives its energy from nuclear reactions. Almost all nuclear explosive devices that have been designed and produced are nuclear weapons intended for warfare.

Other, non-warfare, applications for nuc ...

s have been tested and used, in a similar manner to chemical high explosives

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An expl ...

, for various non-military uses. These have included large-scale earth moving, isotope production and the stimulation and closing-off of the flow of natural gas

Natural gas (also called fossil gas or simply gas) is a naturally occurring mixture of gaseous hydrocarbons consisting primarily of methane in addition to various smaller amounts of other higher alkanes. Low levels of trace gases like carbo ...

.

At the peak of the Atomic Age

The Atomic Age, also known as the Atomic Era, is the period of history following the detonation of the first nuclear weapon, The Gadget at the ''Trinity'' test in New Mexico, on July 16, 1945, during World War II. Although nuclear chain reaction ...

, the United States initiated Operation Plowshare

Project Plowshare was the overall United States program for the development of techniques to use nuclear explosives for peaceful construction purposes. The program was organized in June 1957 as part of the worldwide Atoms for Peace efforts. As ...

, involving "peaceful nuclear explosions". The United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President ...

chairman announced that the Plowshare project was intended to "highlight the peaceful applications of nuclear explosive devices and thereby create a climate of world opinion that is more favorable to weapons development and tests". The Operation Plowshare program included 27 nuclear tests designed towards investigating these non-weapon uses from 1961 through 1973. Due to the inability of the U.S. physicists to reduce the fission fraction of low-yield (approximately 1 kiloton) nuclear devices that would have been required for many civil engineering

Civil engineering is a professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, airports, sewa ...

projects, when long-term health and clean-up costs from fission products were included in the cost, there was virtually no economic advantage over conventional explosives except for potentially the very largest projects.

Friedrich Bassler

Friedrich Bassler (21 June 1909, Karlsruhe – 7 September 1992, Freiburg im Breisgau) was a German hydraulic engineer.

From 1961 to 1977 he was director of the ''Institut für Wasserbau und Wasserwirtschaft'' (Department of water engineering ...

during his appointment to the West German ministry of economics in 1968. He put forth a plan to create a Saharan lake and hydroelectric power station by blasting a tunnel between the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

and the Qattara Depression

The Qattara Depression ( ar, منخفض القطارة, Munḫafaḍ al-Qaṭṭārah) is a depression in northwestern Egypt, specifically in the Matruh Governorate. The depression is part of the Western Desert of Egypt.

The Qattara Depressi ...

in Egypt, an area that lies below sea level. The core problem of the entire project was the water supply to the depression. Calculations by Bassler showed that digging a canal or tunnel would be too expensive, therefore Bassler determined that the use of nuclear explosive devices, to excavate the canal or tunnel, would be the most economical. The Egyptian government declined to pursue the idea.

The Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

conducted a much more exhaustive program than Plowshare, with 239 nuclear tests between 1965 and 1988. Furthermore, many of the "tests" were considered economic applications, not tests, in the Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy

Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy (russian: Ядерные взрывы для народного хозяйства, Yadernyye vzryvy dlya narodnogo khozyaystva; sometimes referred to as ''Program #7'') was a Soviet program to investiga ...

program.

These included a 30 kilotons explosion being used to close the Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: Республика Узбекистан), is a doubly landlocked co ...

i ''Urtabulak'' gas well in 1966 that had been blowing since 1963, and a few months later a 47 kilotons explosive was used to seal a higher-pressure blowout at the nearby ''Pamuk'' gas field. U. S. Department of Energy contract no.: W-7405-Eng48. (For more details, see Blowout (well drilling)#Use of nuclear explosions.)

Devices that produced the highest proportion of their yield via fusion-only reactions are possibly the Taiga

Taiga (; rus, тайга́, p=tɐjˈɡa; relates to Mongolic and Turkic languages), generally referred to in North America as a boreal forest or snow forest, is a biome characterized by coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruc ...

Soviet peaceful nuclear explosions of the 1970s. Their public records indicate 98% of their 15 kiloton explosive yield was derived from fusion reactions, so only 0.3 kiloton was derived from fission.Disturbing the Universe – Freeman Dyson

The repeated detonation of nuclear devices underground in salt domes

A salt dome is a type of structural dome formed when salt (or other evaporite minerals) intrudes into overlying rocks in a process known as diapirism. Salt domes can have unique surface and subsurface structures, and they can be discovered using ...

, in a somewhat analogous manner to the explosions that power a car’s internal combustion engine

An internal combustion engine (ICE or IC engine) is a heat engine in which the combustion of a fuel occurs with an oxidizer (usually air) in a combustion chamber that is an integral part of the working fluid flow circuit. In an internal c ...

(in that it would be a heat engine

In thermodynamics and engineering, a heat engine is a system that converts heat to mechanical energy, which can then be used to do mechanical work. It does this by bringing a working substance from a higher state temperature to a lower state ...

), has also been proposed as a means of fusion power

Fusion power is a proposed form of power generation that would generate electricity by using heat from nuclear fusion reactions. In a fusion process, two lighter atomic nuclei combine to form a heavier nucleus, while releasing energy. Devices de ...

in what is termed PACER. Other investigated uses for low-yield peaceful nuclear explosions were underground detonations to stimulate, by a process analogous to fracking

Fracking (also known as hydraulic fracturing, hydrofracturing, or hydrofracking) is a well stimulation technique involving the fracturing of bedrock formations by a pressurized liquid. The process involves the high-pressure injection of "frac ...

, the flow of petroleum

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crud ...

and natural gas

Natural gas (also called fossil gas or simply gas) is a naturally occurring mixture of gaseous hydrocarbons consisting primarily of methane in addition to various smaller amounts of other higher alkanes. Low levels of trace gases like carbo ...

in tight formations; this was developed most in the Soviet Union, with an increase in the production of many well head

A wellhead is the component at the surface of an oil or gas well that provides the structural and pressure-containing interface for the drilling and production equipment.

The primary purpose of a wellhead is to provide the suspension point and ...

s being reported.

Terraforming

In 2015, billionaire entrepreneurElon Musk

Elon Reeve Musk ( ; born June 28, 1971) is a business magnate and investor. He is the founder, CEO and chief engineer of SpaceX; angel investor, CEO and product architect of Tesla, Inc.; owner and CEO of Twitter, Inc.; founder of The ...

popularized an approach in which the cold planet Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

could be terraformed by the detonation of high-fusion-yielding thermonuclear devices over the mostly dry-ice

Dry ice is the solid form of carbon dioxide. It is commonly used for temporary refrigeration as CO2 does not have a liquid state at normal atmospheric pressure and sublimates directly from the solid state to the gas state. It is used primarily ...

icecaps on the planet.Sorry, Elon Musk: One Does Not Simply Nuke Mars Into Habitability “It is silly to expect Mars to become easily habitable.” /ref> Musk's specific plan would not be very feasible within the energy limitations of historically manufactured nuclear devices (ranging in kilotons of TNT-equivalent), therefore requiring major advancement for it to be considered. In part due to these problems, the physicist

Michio Kaku

Michio Kaku (, ; born January 24, 1947) is an American theoretical physicist, futurist, and popularizer of science ( science communicator). He is a professor of theoretical physics in the City College of New York and CUNY Graduate Center. Kak ...

(who initially put forward the concept) instead suggests using nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat fr ...

s in the typical land-based district heating

District heating (also known as heat networks or teleheating) is a system for distributing heat generated in a centralized location through a system of insulated pipes for residential and commercial heating requirements such as space heating a ...

manner to make isolated tropical biomes on the Martian surface.

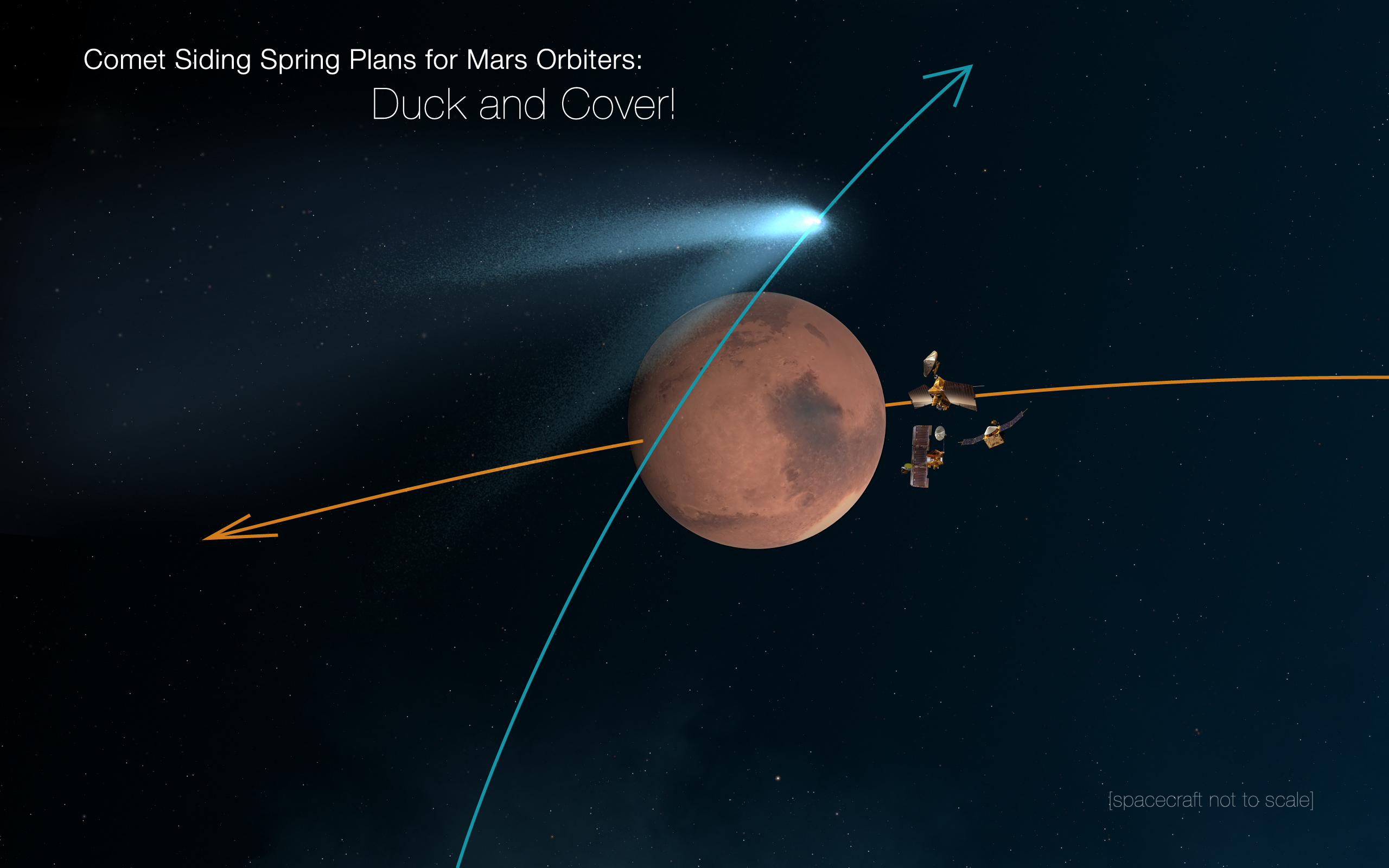

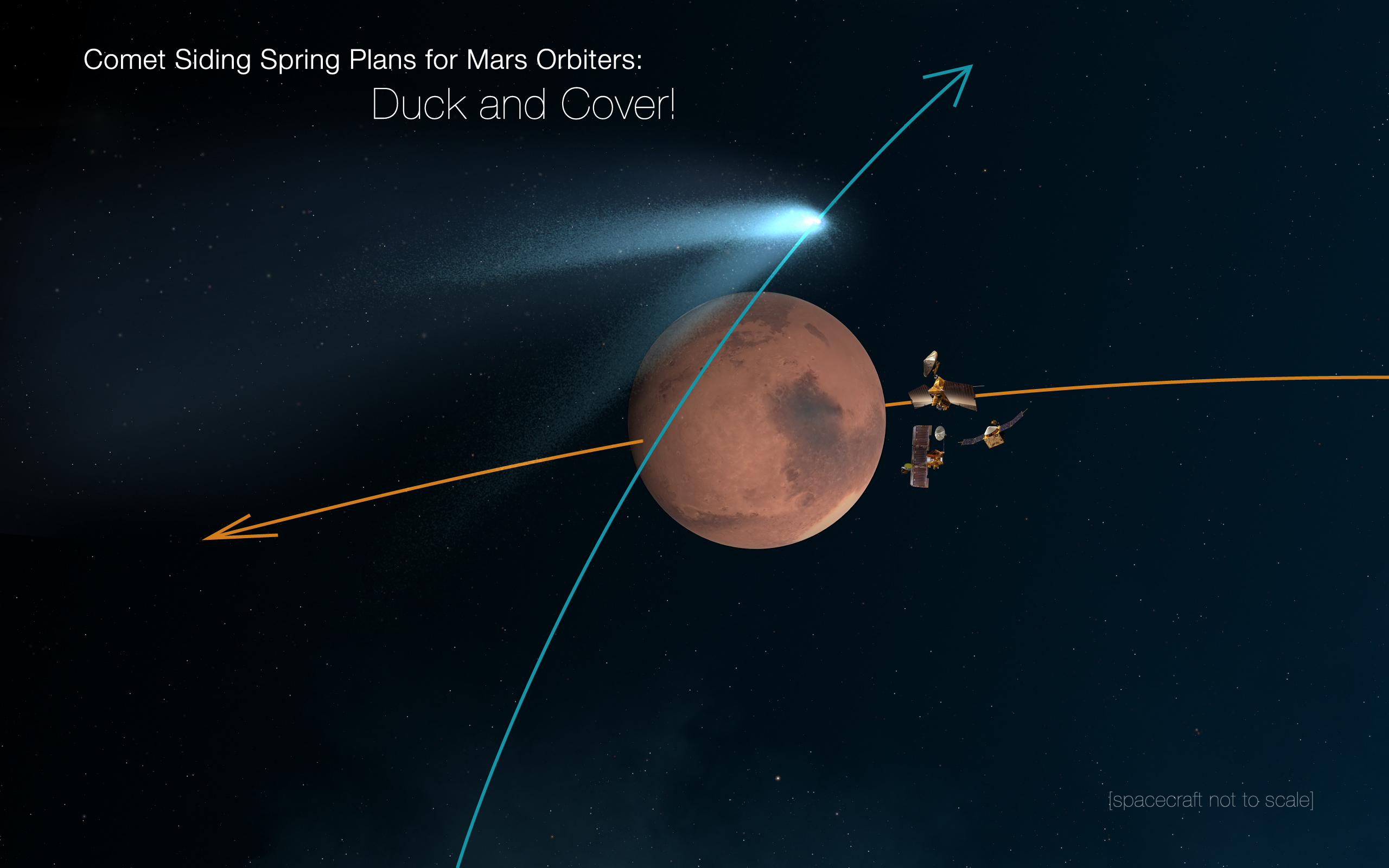

Alternatively, as nuclear detonations are presently somewhat limited in terms of ''demonstrated'' achievable yield, the use of an off-the-shelf nuclear explosive device could be employed to "nudge" a Martian- grazing comet toward a pole of the planet. Impact would be a much more efficient scheme to deliver the required energy, water vapor,

Alternatively, as nuclear detonations are presently somewhat limited in terms of ''demonstrated'' achievable yield, the use of an off-the-shelf nuclear explosive device could be employed to "nudge" a Martian- grazing comet toward a pole of the planet. Impact would be a much more efficient scheme to deliver the required energy, water vapor, greenhouse gases

A greenhouse gas (GHG or GhG) is a gas that absorbs and emits radiant energy within the thermal infrared range, causing the greenhouse effect. The primary greenhouse gases in Earth's atmosphere are water vapor (), carbon dioxide (), methane ...

, and other biologically significant volatiles that could begin to quickly terraform Mars. One such opportunity for this occurred in October 2014 when a "once-in-a-million-years" comet (designated as C/2013 A1

C/2013 A1 (Siding Spring) is an Oort cloud comet discovered on 3 January 2013 by Robert H. McNaught at Siding Spring Observatory using the Uppsala Southern Schmidt Telescope.

At the time of discovery it was 7.2 AU from the Sun and locat ...

, also known as comet "Siding Spring") came within of the Martian atmosphere

The atmosphere of Mars is the layer of gases surrounding Mars. It is primarily composed of carbon dioxide (95%), molecular nitrogen (2.8%), and argon (2%). It also contains trace levels of water vapor, oxygen, carbon monoxide, hydrogen, and no ...

.

Physics

The discovery and synthesis of new

The discovery and synthesis of new chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

s by nuclear transmutation, and their production in the necessary quantities to allow study of their properties, was carried out in nuclear explosive device testing. For example, the discovery of the short-lived einsteinium

Einsteinium is a synthetic element with the symbol Es and atomic number 99. Einsteinium is a member of the actinide series and it is the seventh transuranium element. It was named in honor of Albert Einstein.

Einsteinium was discovered as a com ...

and fermium

Fermium is a synthetic element with the symbol Fm and atomic number 100. It is an actinide and the heaviest element that can be formed by neutron bombardment of lighter elements, and hence the last element that can be prepared in macroscopic qua ...

, both created under the intense neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons beh ...

flux environment within thermonuclear explosions, followed the first Teller–Ulam

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

thermonuclear device test—Ivy Mike

Ivy Mike was the codename given to the first full-scale test of a thermonuclear device, in which part of the explosive yield comes from nuclear fusion.

Ivy Mike was detonated on November 1, 1952, by the United States on the island of Elugelab ...

. The rapid capture of so many neutrons required in the synthesis of einsteinium

Einsteinium is a synthetic element with the symbol Es and atomic number 99. Einsteinium is a member of the actinide series and it is the seventh transuranium element. It was named in honor of Albert Einstein.

Einsteinium was discovered as a com ...

would provide the needed direct experimental confirmation of the so-called r-process, the multiple neutron absorptions needed to explain the cosmic nucleosynthesis

Nucleosynthesis is the process that creates new atomic nuclei from pre-existing nucleons (protons and neutrons) and nuclei. According to current theories, the first nuclei were formed a few minutes after the Big Bang, through nuclear reactions in ...

(production) of all chemical elements heavier than nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

on the periodic table in supernova explosions, before beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron) is emitted from an atomic nucleus, transforming the original nuclide to an isobar of that nuclide. For ...

, with the r-process explaining the existence of many stable elements in the universe.

The worldwide presence of new isotopes from atmospheric testing beginning in the 1950s led to the 2008 development of a reliable way to detect art forgeries. Paintings created after that period may contain traces of caesium-137

Caesium-137 (), cesium-137 (US), or radiocaesium, is a radioactive isotope of caesium that is formed as one of the more common fission products by the nuclear fission of uranium-235 and other fissionable isotopes in nuclear reactors and nucle ...

and strontium-90

Strontium-90 () is a radioactive isotope of strontium produced by nuclear fission, with a half-life of 28.8 years. It undergoes β− decay into yttrium-90, with a decay energy of 0.546 MeV. Strontium-90 has applications in medicine and ...

, isotopes that did not exist in nature before 1945. ( Fission products were produced in the natural nuclear fission reactor

A natural nuclear fission reactor is a uranium deposit where self-sustaining nuclear chain reactions occur. The conditions under which a natural nuclear reactor could exist had been predicted in 1956 by Japanese American chemist Paul Kuroda. ...

at Oklo

Oklo is a region near the town of Franceville, in the Haut-Ogooué province of the Central African country of Gabon. Several natural nuclear fission reactors were discovered in the uranium mines in the region in 1972.

History

Gabon was a Fren ...

about 1.7 billion years ago, but these decayed away before the earliest known human painting.)

Both climatology

Climatology (from Greek , ''klima'', "place, zone"; and , ''-logia'') or climate science is the scientific study of Earth's climate, typically defined as weather conditions averaged over a period of at least 30 years. This modern field of study ...

and particularly aerosol science, a subfield of atmospheric science, were largely created to answer the question of how far and wide fallout

Nuclear fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and the shock wave has passed. It commonly refers to the radioac ...

would travel. Similar to radioactive tracer

A radioactive tracer, radiotracer, or radioactive label is a chemical compound in which one or more atoms have been replaced by a radionuclide so by virtue of its radioactive decay it can be used to explore the mechanism of chemical reactions by ...

s used in hydrology

Hydrology () is the scientific study of the movement, distribution, and management of water on Earth and other planets, including the water cycle, water resources, and environmental watershed sustainability. A practitioner of hydrology is call ...

and materials testing, fallout and the neutron activation

Neutron activation is the process in which neutron radiation induces radioactivity in materials, and occurs when atomic nuclei capture free neutrons, becoming heavier and entering excited states. The excited nucleus decays immediately by emit ...

of nitrogen gas served as a radioactive tracer that was used to measure and then help model global circulations in the atmosphere by following the movements of fallout aerosols.

After the Van Allen Belts surrounding Earth were discovered about in 1958, James Van Allen

James Alfred Van Allen (September 7, 1914August 9, 2006) was an American space scientist at the University of Iowa. He was instrumental in establishing the field of magnetospheric research in space.

The Van Allen radiation belts were named aft ...

suggested that a nuclear detonation would be one way of probing the magnetic phenomenon, data obtained from the August 1958 Project Argus test shots, a high-altitude nuclear explosion

High-altitude nuclear explosions are the result of nuclear weapons testing within the upper layers of the Earth's atmosphere and in outer space. Several such tests were performed at high altitudes by the United States and the Soviet Union betwe ...

investigation, were vital to the early understanding of Earth's magnetosphere.

Soviet nuclear physicist and

Soviet nuclear physicist and Nobel peace prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

recipient Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov ( rus, Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ˈdmʲitrʲɪjevʲɪtɕ ˈsaxərəf; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, nobel laureate and activist for n ...

also proposed the idea that earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, fr ...

s could be mitigated and particle accelerator

A particle accelerator is a machine that uses electromagnetic fields to propel charged particles to very high speeds and energies, and to contain them in well-defined beams.

Large accelerators are used for fundamental research in particle ...

s could be made by utilizing nuclear explosions, with the latter created by connecting a nuclear explosive device with another of his inventions, the explosively pumped flux compression generator

An explosively pumped flux compression generator (EPFCG) is a device used to generate a high-power electromagnetic pulse by compressing magnetic flux using high explosive.

An EPFCG only ever generates a single pulse as the device is physically d ...

, to accelerate protons

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' elementary charge. Its mass is slightly less than that of a neutron and 1,836 times the mass of an electron (the proton–electron mas ...

to collide with each other to probe their inner workings, an endeavor that is now done at much lower energy levels with non-explosive superconducting magnets in CERN. Sakharov suggested to replace the copper coil in his MK generators by a big superconductor solenoid to magnetically compress and focus underground nuclear explosions into a shaped charge

A shaped charge is an explosive charge shaped to form an explosively formed penetrator (EFP) to focus the effect of the explosive's energy. Different types of shaped charges are used for various purposes such as cutting and forming metal, ini ...

effect. He theorized this could focus 1023 positively charged protons per second on a 1 mm2 surface, then envisaged making two such beams collide in the form of a supercollider.

Underground nuclear explosive data from peaceful nuclear explosion test shots have been used to investigate the composition of Earth's mantle, analogous to the exploration geophysics

Exploration geophysics is an applied branch of geophysics and economic geology, which uses physical methods, such as seismic, gravitational, magnetic, electrical and electromagnetic at the surface of the Earth to measure the physical properties of ...

practice of mineral prospecting

Prospecting is the first stage of the geological analysis (followed by exploration) of a territory. It is the search for minerals, fossils, precious metals, or mineral specimens. It is also known as fossicking.

Traditionally prospecting rel ...

with chemical explosives in " deep seismic sounding" reflection seismology.

Project A119

Project A119, also known as A Study of Lunar Research Flights, was a top-secret plan developed in 1958 by the United States Air Force. The aim of the project was to detonate a nuclear bomb on the Moon, which would help in answering some of th ...

, proposed in the 1960s, which as Apollo scientist Gary Latham explained, would have been the detonating of a "smallish" nuclear device on the Moon in order to facilitate research into its geologic make-up. Analogous in concept to the comparatively low yield explosion created by the water prospecting

Prospecting is the first stage of the geological analysis (followed by exploration) of a territory. It is the search for minerals, fossils, precious metals, or mineral specimens. It is also known as fossicking.

Traditionally prospecting rel ...

(LCROSS) Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite mission, which launched in 2009 and released the "Centaur" kinetic energy

In physics, the kinetic energy of an object is the energy that it possesses due to its motion.

It is defined as the work needed to accelerate a body of a given mass from rest to its stated velocity. Having gained this energy during its acc ...

impactor, an impactor with a mass of 2,305 kg (5,081 lb), and an impact velocity of about , releasing the kinetic energy equivalent of detonating approximately 2 tons of TNT

Trinitrotoluene (), more commonly known as TNT, more specifically 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, and by its preferred IUPAC name 2-methyl-1,3,5-trinitrobenzene, is a chemical compound with the formula C6H2(NO2)3CH3. TNT is occasionally used as a reagen ...

(8.86 GJ).

Propulsion use

The first preliminary examination of the effects of nuclear detonations upon various metal and non-metal materials, occurred in 1955 withOperation Teapot

Operation Teapot was a series of 14 nuclear test explosions conducted at the Nevada Test Site in the first half of 1955. It was preceded by ''Operation Castle'', and followed by ''Operation Wigwam''. ''Wigwam'' was, administratively, a part of ...

, were a chain of approximately basketball sized spheres of material, were arrayed at fixed aerial distances, descending from the shot tower.Declassified video 0800017 - Operation Teapot, Military Effects Studies - 1954. circa 19 mins In what was then a surprising experimental observation, all but the spheres directly within the shot tower survived, with the greatest ablation

Ablation ( la, ablatio – removal) is removal or destruction of something from an object by vaporization, chipping, erosive processes or by other means. Examples of ablative materials are described below, and include spacecraft material for a ...

noted on the aluminum sphere located from the detonation point, with slightly over of surface material absent upon recovery. These spheres are often referred to as "Lew Allen

Lew Allen Jr. (September 30, 1925 – January 4, 2010) was a United States Air Force four-star general who served as the tenth Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force. As chief of staff, Allen served as the senior uniformed Air Force officer ...

's balls", after the project manager during the experiments.Project Orion: the true story of the atomic spaceship 2002/ref> The ablation data collected for various materials and the distances the spheres were propelled, serve as the bedrock for the nuclear pulse propulsion study, Project Orion. The direct use of nuclear explosives, by using the impact of ablated propellant plasma from a nuclear

shaped charge

A shaped charge is an explosive charge shaped to form an explosively formed penetrator (EFP) to focus the effect of the explosive's energy. Different types of shaped charges are used for various purposes such as cutting and forming metal, ini ...

acting on the rear pusher plate of a ship, was and continues to be seriously studied as a potential propulsion

Propulsion is the generation of force by any combination of pushing or pulling to modify the translational motion of an object, which is typically a rigid body (or an articulated rigid body) but may also concern a fluid. The term is derived f ...

mechanism.

Although likely never achieving orbit due to aerodynamic drag, the first macroscopic

The macroscopic scale is the length scale on which objects or phenomena are large enough to be visible with the naked eye, without magnifying optical instruments. It is the opposite of microscopic.

Overview

When applied to physical phenomena a ...

object to obtain Earth orbital velocity was a "900kg manhole cover" propelled by the somewhat focused detonation of test shot Pascal-B in August 1957. The use of a subterranean shaft and nuclear device to propel an object to escape velocity has since been termed a "thunder well".

In the 1970s Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

, in the United States, popularized the concept of using a nuclear detonation to power an explosively pumped ''soft'' X-ray laser

An X-ray laser is a device that uses stimulated emission to generate or amplify electromagnetic radiation in the near X-ray or extreme ultraviolet region of the spectrum, that is, usually on the order of several tens of nanometers (nm) wavelength ...

as a component of a ballistic missile defense

Missile defense is a system, weapon, or technology involved in the detection, tracking, interception, and also the destruction of attacking missiles. Conceived as a defense against nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), ...

shield known as Project Excalibur

Project Excalibur was a Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) Cold Warera research program to develop an X-ray laser system as a ballistic missile defense (BMD) for the United States. The concept involved packing large numbers of expendab ...

. This created dozens of highly focused X-ray beams that would cause the missile to break up due to laser ablation.

Laser ablation is one of the damage mechanisms of a laser weapon

A laser weapon is a directed-energy weapon based on lasers. After decades of R&D, directed-energy weapons including lasers are still at the experimental stage and it remains to be seen if or when they will be deployed as practical, high-perf ...

, but it is also one of the researched methods behind pulsed laser propulsion

Laser propulsion is a form of beam-powered propulsion where the energy source is a remote (usually ground-based) laser system and separate from the reaction mass. This form of propulsion differs from a conventional chemical rocket where both energ ...

intended for spacecraft, though usually powered by means of conventionally pumped, laser arrays. For example, ground flight testing by Professor Leik Myrabo, using a non-nuclear, conventionally powered pulsed laser test-bed, successfully lifted a lightcraft

The Lightcraft is a space- or air-vehicle driven by beam-powered propulsion, the energy source powering the craft being external. It was conceptualized by aerospace engineering professor Leik Myrabo at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1976,

...

72 meters in altitude by a method similar to ablative laser propulsion in 2000.

A powerful solar system based ''soft'' X-ray, to ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation ...

, laser system has been calculated to be capable of propelling an interstellar spacecraft, by the light sail

Solar sails (also known as light sails and photon sails) are a method of spacecraft propulsion using radiation pressure exerted by sunlight on large mirrors. A number of spaceflight missions to test solar propulsion and navigation have been p ...

principle, to 11% of the speed of light

The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted , is a universal physical constant that is important in many areas of physics. The speed of light is exactly equal to ). According to the special theory of relativity, is the upper limit ...

. In 1972 it was also calculated that a 1 Terawatt, 1-km diameter X-ray laser

An X-ray laser is a device that uses stimulated emission to generate or amplify electromagnetic radiation in the near X-ray or extreme ultraviolet region of the spectrum, that is, usually on the order of several tens of nanometers (nm) wavelength ...

with 1 angstrom

The angstromEntry "angstrom" in the Oxford online dictionary. Retrieved on 2019-03-02 from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/angstrom.Entry "angstrom" in the Merriam-Webster online dictionary. Retrieved on 2019-03-02 from https://www.m ...

wavelength impinging on a 1-km diameter sail, could propel a spacecraft to Alpha Centauri in 10 years.

Asteroid impact avoidance

A proposed means of averting an asteroid impacting with Earth, assuming short lead times between detection and Earth impact, is to detonate one, or a series, of nuclear explosive devices, on, in, or in a stand-off proximity orientation with the asteroid, with the latter method occurring far enough away from the incoming threat to prevent the potential fracturing of thenear-Earth object

A near-Earth object (NEO) is any small Solar System body whose orbit brings it into proximity with Earth. By convention, a Solar System body is a NEO if its closest approach to the Sun (perihelion) is less than 1.3 astronomical units (AU). ...

, but still close enough to generate a high thrust laser ablation effect.

A 2007 NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil List of government space agencies, space program ...

analysis of impact avoidance strategies using various technologies stated:

Nuclear stand-off explosions are assessed to be 10–100 times more effective than the non-nuclear alternatives analyzed in this study. Other techniques involving thesurface A surface, as the term is most generally used, is the outermost or uppermost layer of a physical object or space. It is the portion or region of the object that can first be perceived by an observer using the senses of sight and touch, and is ...or subsurface use of nuclear explosives may be more efficient, but they run an increased risk of fracturing the target near-Earth object. They also carry higher development and operations risks.

See also

*Operation Plowshare

Project Plowshare was the overall United States program for the development of techniques to use nuclear explosives for peaceful construction purposes. The program was organized in June 1957 as part of the worldwide Atoms for Peace efforts. As ...

*Operation Chariot

The St Nazaire Raid or Operation Chariot was a British amphibious attack on the heavily defended Normandie dry dock at St Nazaire in German-occupied France during the Second World War. The operation was undertaken by the Royal Navy (RN) a ...

* Project Gnome

* Project Orion

*Nuclear terrorism

Nuclear terrorism refers to any person or persons detonating a nuclear weapon as an act of terrorism (i.e., illegal or immoral use of violence for a political or religious cause). Some definitions of nuclear terrorism include the sabotage of a ...

Books

IAEA review of the 1968 book: The constructive uses of nuclear explosions by Edward Teller.

References

External links

*. *. *. *. *. On the Soviet nuclear program. *. *. *. *. *. * includes tests of peaceful nuclear explosions. {{Nuclear technology Nuclear technology Nuclear weapons testing ru:Мирные ядерные взрывы в СССР