Paul A. Samuelson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Paul Anthony Samuelson (May 15, 1915 – December 13, 2009) was an American

''

Samuelson was born in

Samuelson was born in

''

"Statistical Entropy in General Equilibrium Theory"

(p. 3). Department of Economics, Florida International University. The book proposes to: * examine underlying analogies between central features in theoretical and applied economics and * study how '' operationally meaningful theorems'' can be derived with a small number of ''analogous methods'' (p. 3), in order to derive "a general theory of economic theories" (Samuelson, 1983, p. xxvi). The book showed how these goals could be parsimoniously and fruitfully achieved, using the language of the mathematics applied to diverse subfields of economics. The book proposes two general hypotheses as sufficient for its purposes: * ''maximizing behavior'' of ''agents'' (including ''consumers'' as to utility and ''business firms'' as to profit) and * economic ''systems'' (including a market and an economy) in ''stable equilibrium''. In the first tenet, his views presented the idea that all actors, whether firms or consumers, are striving to maximize something. They could be attempting to maximize profits, utility, or wealth, but it did not matter because their efforts to improve their well-being would provide a basic model for all actors in an economic system. His second tenet was focused on providing insight on the workings of equilibrium in an economy. Generally in a market, supply would equal demand. However, he urged that this might not be the case and that the important thing to look at was a system's natural resting point. ''Foundations'' presents the question of how an equilibrium would react when it is moved from its optimal point. Samuelson was also influential in providing explanations on how the changes in certain factors can affect an economic system. For example, he could explain the economic effect of changes in taxes or new technologies. In the course of analysis, ''

Elements of Economics

'.

56–66

* * Samuelson, Paul A. (1958), ''Linear Programming and Economic Analysis'' with

links.

* * * ''The Collected Scientific Papers of Paul A. Samuelson'', MIT Press. Preview links for vol. 1–3 below. Contents links for vol. 4–7. . :Samuelson, Paul A. (1966), Vol

1

→ via

2

→ via

3

→ via

4

→ via

5

→ via

Description

→ via :Samuelson, Paul A. (2011), Vol

6

1986–2009

Description

→ via

7

1986–2009.

Paul A. Samuelson Papers, 1933–2010

Rubenstein Library,

pp. 5-12.

* Samuelson, Paul A. (2007), ''Inside the Economist's Mind: Conversations with Eminent Economists'' with

Description

arrow-scrollable preview

* * . * . * . * .

by Professor

''A History of Economic Thought'' biography

2004 *

Yale Honorands biography, May 2005

''MIT News'', December 13, 2009 * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Samuelson, Paul 1915 births 2009 deaths Nobel laureates in Economics American Nobel laureates 20th-century American writers 21st-century American non-fiction writers 20th-century American economists 21st-century American economists American people of Polish-Jewish descent Fellows of the Econometric Society Harvard University alumni Jewish American writers Jewish American social scientists Kennedy administration personnel MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences faculty Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences National Medal of Science laureates Writers from Gary, Indiana Trade economists University of Chicago alumni Neo-Keynesian economists Presidents of the Econometric Society People from Belmont, Massachusetts Presidents of the American Economic Association Economists from Massachusetts Economists from Indiana Corresponding Fellows of the British Academy Hyde Park Academy High School alumni Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery Members of the American Philosophical Society

economist

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social sciences, social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this ...

who was the first American to win the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, officially the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel ( sv, Sveriges riksbanks pris i ekonomisk vetenskap till Alfred Nobels minne), is an economics award administered ...

. When awarding the prize in 1970, the Swedish Royal Academies The Royal Academies are independent organizations, founded on Royal command, that act to promote the arts, culture, and science in Sweden. The Swedish Academy and Academy of Sciences are also responsible for the selection of Nobel Prize laureates i ...

stated that he "has done more than any other contemporary economist to raise the level of scientific analysis in economic theory". "In a career that spanned seven decades, he transformed his field, influenced millions of students and turned MIT into an economics powerhouse" Economic historian Randall E. Parker has called him the "Father of Modern Economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and intera ...

", and ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' considers him to be the "foremost academic economist of the 20th century".

Samuelson was likely the most influential economist of the latter half of the 20th century."Paul Samuelson: The last of the great general economists died on December 13th, aged 94"''

The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Econo ...

'', December 17, 2009 In 1996, when he was awarded the National Medal of Science

The National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral and social scienc ...

, considered to be America's top science-honor, President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

commended Samuelson for his "fundamental contributions to economic science" for over 60 years. Samuelson considered mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

to be the "natural language" for economists and contributed significantly to the mathematical foundations of economics with his book ''Foundations of Economic Analysis

''Foundations of Economic Analysis'' is a book by Paul A. Samuelson published in 1947 (Enlarged ed., 1983) by Harvard University Press. It is based on Samuelson's 1941 doctoral dissertation at Harvard University. The book sought to demonstrate a ...

''. He was author of the best-selling economics textbook of all time: '' Economics: An Introductory Analysis'', first published in 1948. It was the second American textbook that attempted to explain the principles of Keynesian economics

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output an ...

. It is now in its 19th edition, having sold nearly 4 million copies in 40 languages. James Poterba

James Michael "Jim" Poterba, FBA (born July 13, 1958) is an American economist, Mitsui Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and current NBER president and chief executive officer.

Early years

Poterba was born in N ...

, former head of MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the mo ...

's Department of Economics, noted that by his book, Samuelson "leaves an immense legacy, as a researcher and a teacher, as one of the giants on whose shoulders every contemporary economist stands".

He entered the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

at age 16, during the depths of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, and received his PhD PHD or PhD may refer to:

* Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), an academic qualification

Entertainment

* '' PhD: Phantasy Degree'', a Korean comic series

* ''Piled Higher and Deeper'', a web comic

* Ph.D. (band), a 1980s British group

** Ph.D. (Ph.D. albu ...

in economics from Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. After graduating, he became an assistant professor of economics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

(MIT) when he was 25 years of age and a full professor at age 32. In 1966, he was named Institute Professor

An institute is an organisational body created for a certain purpose. They are often research organisations (research institutes) created to do research on specific topics, or can also be a professional body.

In some countries, institutes can ...

, MIT's highest faculty honor. He spent his career at MIT, where he was instrumental in turning its Department of Economics into a world-renowned institution by attracting other noted economists to join the faculty, including later winners of the Nobel Prize Robert Solow

Robert Merton Solow, GCIH (; born August 23, 1924) is an American economist whose work on the theory of economic growth culminated in the exogenous growth model named after him. He is currently Emeritus Institute Professor of Economics at the Ma ...

, Franco Modigliani

Franco Modigliani (18 June 1918 – 25 September 2003) was an Italian-American economist and the recipient of the 1985 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. He was a professor at University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Carnegie Mellon Uni ...

, Robert C. Merton

Robert Cox Merton (born July 31, 1944) is an American economist, Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences laureate, and professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management, known for his pioneering contributions to continuous-time finance, especia ...

, Joseph Stiglitz

Joseph Eugene Stiglitz (; born February 9, 1943) is an American New Keynesian economist, a public policy analyst, and a full professor at Columbia University. He is a recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (2001) and the Joh ...

, and Paul Krugman

Paul Robin Krugman ( ; born February 28, 1953) is an American economist, who is Distinguished Professor of Economics at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and a columnist for ''The New York Times''. In 2008, Krugman was th ...

.

He served as an advisor to Presidents John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

and Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

, and was a consultant to the United States Treasury

The Department of the Treasury (USDT) is the national treasury and finance department of the federal government of the United States, where it serves as an executive department. The department oversees the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and t ...

, the Bureau of the Budget and the President's Council of Economic Advisers

The Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) is a United States agency within the Executive Office of the President established in 1946, which advises the President of the United States on economic policy. The CEA provides much of the empirical resea ...

. Samuelson wrote a weekly column for ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis (businessman), Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print m ...

'' magazine along with Chicago School economist Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

, where they represented opposing sides: Samuelson, as a self described "Cafeteria Keynesian", claimed taking the Keynesian perspective but only accepting what he felt was good in it. By contrast, Friedman represented the monetarist

Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of governments in controlling the amount of money in circulation. Monetarist theory asserts that variations in the money supply have major influences on national ...

perspective. Together with Henry Wallich

Henry Christopher Wallich (; June 10, 1914 – September 15, 1988) was a German American economist who served as a member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors from 1974 to 1986. He previously served as a member of the Council of the Economic ...

, their 1967 columns earned the magazine a Gerald Loeb Special Award The Gerald Loeb Award is given annually for multiple categories of business reporting. Special awards were occasionally given for distinguished business journalism that doesn't necessarily fit into other categories.

Gerald Loeb Special Award winner ...

in 1968.

Samuelson worked in many theoretical fields, including: consumer theory

The theory of consumer choice is the branch of microeconomics that relates preferences to consumption expenditures and to consumer demand curves. It analyzes how consumers maximize the desirability of their consumption as measured by their pref ...

; welfare economics

Welfare economics is a branch of economics that uses microeconomic techniques to evaluate well-being (welfare) at the aggregate (economy-wide) level.

Attempting to apply the principles of welfare economics gives rise to the field of public econ ...

; capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used f ...

; finance

Finance is the study and discipline of money, currency and capital assets. It is related to, but not synonymous with economics, the study of production, distribution, and consumption of money, assets, goods and services (the discipline of fina ...

, particularly the efficient-market hypothesis

The efficient-market hypothesis (EMH) is a hypothesis in financial economics that states that asset prices reflect all available information. A direct implication is that it is impossible to "beat the market" consistently on a risk-adjusted bas ...

; public finance

Public finance is the study of the role of the government in the economy. It is the branch of economics that assesses the government revenue and government expenditure of the public authorities and the adjustment of one or the other to achie ...

, particularly optimal allocation; international economics

International economics is concerned with the effects upon economic activity from international differences in productive resources and consumer preferences and the international institutions that affect them. It seeks to explain the patterns and ...

, particularly the Balassa–Samuelson effect

The Balassa–Samuelson effect, also known as Harrod–Balassa–Samuelson effect (Kravis and Lipsey 1983), the Ricardo–Viner–Harrod–Balassa–Samuelson–Penn–Bhagwati effect (Samuelson 1994, p. 201), or productivity biased purchasin ...

and the Heckscher–Ohlin model

The Heckscher–Ohlin model (, H–O model) is a general equilibrium mathematical model of international trade, developed by Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin at the Stockholm School of Economics. It builds on David Ricardo's theory of comparative ad ...

; macroeconomics

Macroeconomics (from the Greek prefix ''makro-'' meaning "large" + ''economics'') is a branch of economics dealing with performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of an economy as a whole.

For example, using interest rates, taxes, and ...

, particularly the overlapping generations model

The overlapping generations (OLG) model is one of the dominating frameworks of analysis in the study of macroeconomic dynamics and economic growth. In contrast, to the Ramsey–Cass–Koopmans neoclassical growth model in which individuals are ...

; and market economics

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand, where all suppliers and consumers ...

.

Biography

Samuelson was born in

Samuelson was born in Gary, Indiana

Gary is a city in Lake County, Indiana, United States. The city has been historically dominated by major industrial activity and is home to U.S. Steel's Gary Works, the largest steel mill complex in North America. Gary is located along the ...

, on May 15, 1915, to Frank Samuelson, a pharmacist

A pharmacist, also known as a chemist (Commonwealth English) or a druggist (North American and, archaically, Commonwealth English), is a healthcare professional who prepares, controls and distributes medicines and provides advice and instructi ...

, and Ella ''née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

'' Lipton. His family, he later said, was "made up of upwardly mobile Jewish immigrants from Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

who had prospered considerably in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, because Gary was a brand new steel-town when my family went there". In 1923, Samuelson moved to Chicago where he graduated from Hyde Park High School (now Hyde Park Career Academy

Hyde Park Academy High School (formerly known as Hyde Park High School and Hyde Park Career Academy) is a public 4–year high school located in the Woodlawn neighborhood on the south side of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Opened in 1863, Hyd ...

). He then studied at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

and received his Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

degree there in 1935. He said he was born as an economist, at 8.00am on January 2, 1932, in the University of Chicago classroom. The lecture mentioned as the cause was on the British economist Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English cleric, scholar and influential economist in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book '' An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

, who most famously studied population growth and its effects. Samuelson felt there was a dissonance between neoclassical economics

Neoclassical economics is an approach to economics in which the production, consumption and valuation (pricing) of goods and services are observed as driven by the supply and demand model. According to this line of thought, the value of a good ...

and the way the system seemed to behave; he said Henry Simons and Frank Knight

Frank Hyneman Knight (November 7, 1885 – April 15, 1972) was an American economist who spent most of his career at the University of Chicago, where he became one of the founders of the Chicago School. Nobel laureates Milton Friedman, George S ...

were a big influence on him. He next completed his Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

degree in 1936, and his Doctor of Philosophy

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common Academic degree, degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields ...

in 1941 at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. He won the David A. Wells prize in 1941 for writing the best doctoral dissertation at Harvard University in economics, for a thesis titled "Foundations of Analytical Economics", which later turned into ''Foundations of Economic Analysis

''Foundations of Economic Analysis'' is a book by Paul A. Samuelson published in 1947 (Enlarged ed., 1983) by Harvard University Press. It is based on Samuelson's 1941 doctoral dissertation at Harvard University. The book sought to demonstrate a ...

''. As a graduate student at Harvard, Samuelson studied economics under Joseph Schumpeter

Joseph Alois Schumpeter (; February 8, 1883 – January 8, 1950) was an Austrian-born political economist. He served briefly as Finance Minister of German-Austria in 1919. In 1932, he emigrated to the United States to become a professor at Ha ...

, Wassily Leontief

Wassily Wassilyevich Leontief (russian: Васи́лий Васи́льевич Лео́нтьев; August 5, 1905 – February 5, 1999), was a Soviet-American economist known for his research on input–output analysis and how changes in one ec ...

, Gottfried Haberler

Gottfried von Haberler (; July 20, 1900 – May 6, 1995) was an Austrian-American economist. He worked in particular on international trade. One of his major contributions was reformulating the Ricardian idea of comparative advantage in a neoc ...

, and the "American Keynes" Alvin Hansen

Alvin Harvey Hansen (August 23, 1887 – June 6, 1975) was an American economist who taught at the University of Minnesota and was later a chair professor of economics at Harvard University. Often referred to as "the American John Maynard Keynes ...

. Samuelson moved to MIT as an assistant professor in 1940 and remained there until his death.

Samuelson's family included many well-known economists, including brother Robert Summers

Robert Summers (June 22, 1922 – April 17, 2012) was an American economist and professor at the University of Pennsylvania, where he taught from 1960. A widely cited early work by Summers is on the small-sample statistical properties of alternate ...

, sister-in-law Anita Summers

Anita Arrow Summers (born September 9, 1925) is an American educator of public policy, management, real estate and education and is Professor Emerita at the University of Pennsylvania.

Biography

Anita Arrow was born in New York City on September ...

, brother-in-law Kenneth Arrow

Kenneth Joseph Arrow (23 August 1921 – 21 February 2017) was an American economist, mathematician, writer, and political theorist. He was the joint winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with John Hicks in 1972.

In economics ...

and nephew Larry Summers

Lawrence Henry Summers (born November 30, 1954) is an American economist who served as the 71st United States secretary of the treasury from 1999 to 2001 and as director of the National Economic Council from 2009 to 2010. He also served as pres ...

.

During his seven decades as an economist, Samuelson's professional positions included:

* Assistant professor of economics at MIT, 1940; associate professor, 1944.

* Member of the Radiation Laboratory 1944–45.

* Professor of international economic relations (part-time) at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy

The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy is the graduate school of international affairs of Tufts University, in Medford, Massachusetts. The School is one of America's oldest graduate schools of international relations and is well-ranked in it ...

in 1945.

* Guggenheim Fellowship from 1948 to 1949

* Professor of economics at MIT beginning in 1947 and Institute Professor

An institute is an organisational body created for a certain purpose. They are often research organisations (research institutes) created to do research on specific topics, or can also be a professional body.

In some countries, institutes can ...

beginning in 1962.

* Vernon F. Taylor Visiting Distinguished Professor at Trinity University (Texas)

Trinity University is a private liberal arts college in San Antonio, Texas. Founded in 1869, its student body consists of about 2,600 undergraduate and 200 graduate students. Trinity offers 49 majors and 61 minors among six degree programs, ...

in spring 1989.

Death

Samuelson died after a brief illness on December 13, 2009, at the age of 94. His death was announced by theMassachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

. James M. Poterba

James Michael "Jim" Poterba, FBA (born July 13, 1958) is an American economist, Mitsui Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and current NBER president and chief executive officer.

Early years

Poterba was born in N ...

, an economics professor at MIT and the president of the National Bureau of Economic Research

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is an American private nonprofit research organization "committed to undertaking and disseminating unbiased economic research among public policymakers, business professionals, and the academic c ...

, commented that Samuelson "leaves an immense legacy, as a researcher and a teacher, as one of the giants on whose shoulders every contemporary economist stands". Susan Hockfield

Susan Hockfield (born March 24, 1951) is an American neuroscientist who served as the sixteenth president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from December 2004 through June 2012. Hockfield succeeded Charles M. Vest and was succeeded by ...

, the president of MIT, said that Samuelson "transformed everything he touched: the theoretical foundations of his field, the way economics was taught around the world, the ethos and stature of his department, the investment practices of MIT, and the lives of his colleagues and students"."Economics revolutionary Paul Samuelson dies aged 94"''

The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'', December 14, 2009

Fields of interest

As professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Samuelson worked in many fields, including: *Consumer theory

The theory of consumer choice is the branch of microeconomics that relates preferences to consumption expenditures and to consumer demand curves. It analyzes how consumers maximize the desirability of their consumption as measured by their pref ...

, where he pioneered the revealed preference

Revealed preference theory, pioneered by economist Paul Anthony Samuelson in 1938, is a method of analyzing choices made by individuals, mostly used for comparing the influence of policies on consumer behavior. Revealed preference models assume t ...

approach, which is a method by which one can discern a consumer's utility function

As a topic of economics, utility is used to model worth or value. Its usage has evolved significantly over time. The term was introduced initially as a measure of pleasure or happiness as part of the theory of utilitarianism by moral philosopher ...

, by observing their behavior. Rather than postulate a utility function

As a topic of economics, utility is used to model worth or value. Its usage has evolved significantly over time. The term was introduced initially as a measure of pleasure or happiness as part of the theory of utilitarianism by moral philosopher ...

or a preference ordering, Samuelson imposed conditions directly on the choices made by individuals – their preferences as revealed by their choices.

* Welfare economics

Welfare economics is a branch of economics that uses microeconomic techniques to evaluate well-being (welfare) at the aggregate (economy-wide) level.

Attempting to apply the principles of welfare economics gives rise to the field of public econ ...

, in which he popularised the Lindahl–Bowen–Samuelson conditions (criteria for deciding whether an action will improve welfare) and demonstrated in 1950 the insufficiency of a national-income index to reveal which of two social options was uniformly outside the other's (feasible) possibility function (''Collected Scientific Papers'', v. 2, ch. 77; Fischer, 1987, p. 236).

* Capital theory, where he is known for 1958 consumption loans model and a variety of turnpike theorems and involved in Cambridge capital controversy

The Cambridge capital controversy, sometimes called "the capital controversy"Brems (1975) pp. 369-384 or "the two Cambridges debate", was a dispute between proponents of two differing theoretical and mathematical positions in economics that starte ...

.

* Finance

Finance is the study and discipline of money, currency and capital assets. It is related to, but not synonymous with economics, the study of production, distribution, and consumption of money, assets, goods and services (the discipline of fina ...

theory, in which he is known for the efficient-market hypothesis

The efficient-market hypothesis (EMH) is a hypothesis in financial economics that states that asset prices reflect all available information. A direct implication is that it is impossible to "beat the market" consistently on a risk-adjusted bas ...

.

* Public finance

Public finance is the study of the role of the government in the economy. It is the branch of economics that assesses the government revenue and government expenditure of the public authorities and the adjustment of one or the other to achie ...

theory, in which he is particularly known for his work on determining the optimal allocation of resources in the presence of both public goods and private good

A private good is defined in economics as "an item that yields positive benefits to people" that is excludable, i.e. its owners can exercise private property rights, preventing those who have not paid for it from using the good or consuming its be ...

s.

* International economics

International economics is concerned with the effects upon economic activity from international differences in productive resources and consumer preferences and the international institutions that affect them. It seeks to explain the patterns and ...

, where he influenced the development of two important international trade models: the Balassa–Samuelson effect

The Balassa–Samuelson effect, also known as Harrod–Balassa–Samuelson effect (Kravis and Lipsey 1983), the Ricardo–Viner–Harrod–Balassa–Samuelson–Penn–Bhagwati effect (Samuelson 1994, p. 201), or productivity biased purchasin ...

, and the Heckscher–Ohlin model

The Heckscher–Ohlin model (, H–O model) is a general equilibrium mathematical model of international trade, developed by Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin at the Stockholm School of Economics. It builds on David Ricardo's theory of comparative ad ...

(with the Stolper–Samuelson theorem

The Stolper–Samuelson theorem is a basic theorem in Heckscher–Ohlin trade theory. It describes the relationship between relative prices of output and relative factor rewards—specifically, real wages and real returns to capital.

The theore ...

).

* Macroeconomics

Macroeconomics (from the Greek prefix ''makro-'' meaning "large" + ''economics'') is a branch of economics dealing with performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of an economy as a whole.

For example, using interest rates, taxes, and ...

, where he popularized the overlapping generations model

The overlapping generations (OLG) model is one of the dominating frameworks of analysis in the study of macroeconomic dynamics and economic growth. In contrast, to the Ramsey–Cass–Koopmans neoclassical growth model in which individuals are ...

as a way to analyze economic agents' behavior across multiple periods of time (''Collected Scientific Papers'', v. 1, ch. 21) and contributed to formation of the neoclassical synthesis

The neoclassical synthesis (NCS), neoclassical–Keynesian synthesis, or just neo-Keynesianism was a neoclassical economics academic movement and paradigm in economics that worked towards reconciling the macroeconomic thought of John Maynard Key ...

.

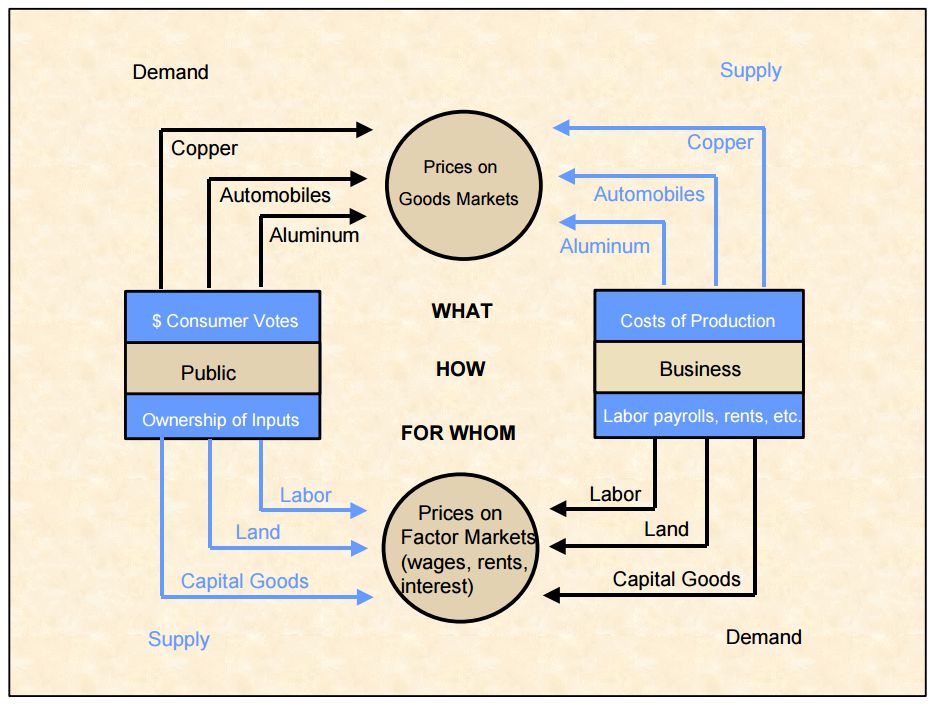

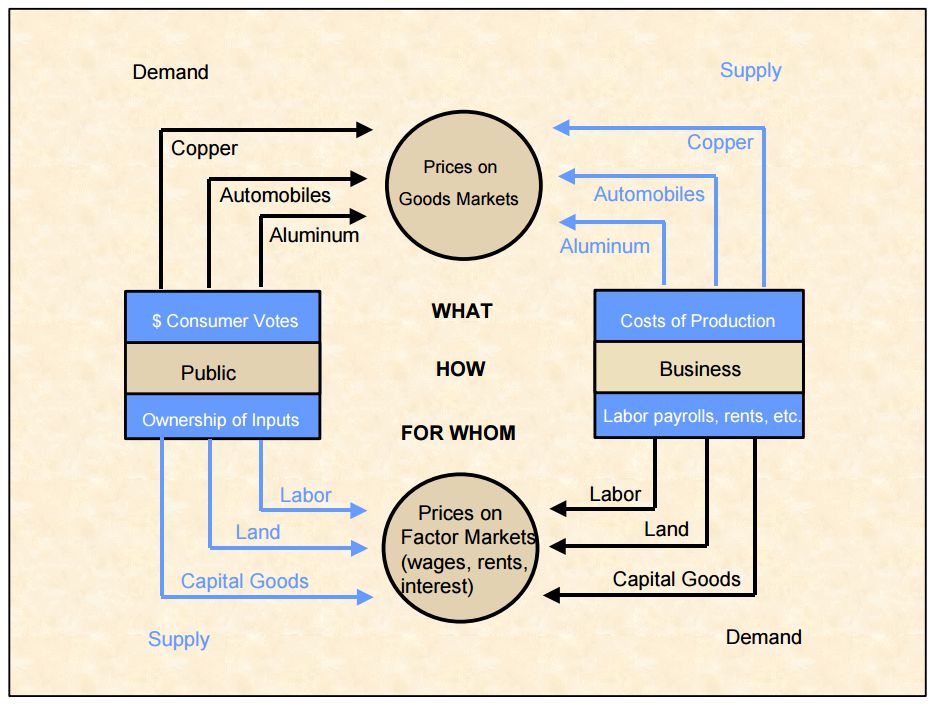

* Market economics

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand, where all suppliers and consumers ...

: Samuelson believed unregulated markets

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ...

have drawbacks, he stated, "free markets do not stabilise themselves. Zero regulating is vastly suboptimal to rational regulating. Libertarianism is its own worst enemy!" Samuelson strongly criticised Friedman and Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek ( , ; 8 May 189923 March 1992), often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian–British economist, legal theorist and philosopher who is best known for his defense of classical liberalism. Haye ...

, arguing their opposition to state intervention "tells us something about them rather than something about Genghis Khan

''Chinggis Khaan'' ͡ʃʰiŋɡɪs xaːŋbr />Mongol script: ''Chinggis Qa(gh)an/ Chinggis Khagan''

, birth_name = Temüjin

, successor = Tolui (as regent)Ögedei Khan

, spouse =

, issue =

, house = Borjigin

, ...

or Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

. It is paranoid to warn against inevitable slippery slopes ... once individual commercial freedoms are in any way infringed upon."

Impact

Samuelson is considered one of the founders ofneo-Keynesian economics

The neoclassical synthesis (NCS), neoclassical–Keynesian synthesis, or just neo-Keynesianism was a neoclassical economics academic movement and paradigm in economics that worked towards reconciling the macroeconomic thought of John Maynard Key ...

and a seminal figure in the development of neoclassical economics

Neoclassical economics is an approach to economics in which the production, consumption and valuation (pricing) of goods and services are observed as driven by the supply and demand model. According to this line of thought, the value of a good ...

. In awarding him the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, officially the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel ( sv, Sveriges riksbanks pris i ekonomisk vetenskap till Alfred Nobels minne), is an economics award administered ...

the committee stated:

He was also essential in creating the neoclassical synthesis

The neoclassical synthesis (NCS), neoclassical–Keynesian synthesis, or just neo-Keynesianism was a neoclassical economics academic movement and paradigm in economics that worked towards reconciling the macroeconomic thought of John Maynard Key ...

, which ostensibly incorporated Keynesian

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output and ...

and neoclassical principles and still dominates current mainstream economics

Mainstream economics is the body of knowledge, theories, and models of economics, as taught by universities worldwide, that are generally accepted by economists as a basis for discussion. Also known as orthodox economics, it can be contrasted to h ...

. In 2003, Samuelson was one of the ten Nobel Prize–winning economists signing the Economists' statement opposing the Bush tax cuts The Economists' statement opposing the Bush tax cuts was a statement signed by roughly 450 economists, including ten of the twenty-four American Nobel Prize laureates alive at the time, in February 2003 who urged the U.S. President George W. Bush n ...

.

Aphorisms and quotations

Stanislaw Ulam

Stanisław Marcin Ulam (; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a Polish-American scientist in the fields of mathematics and nuclear physics. He participated in the Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapon ...

once challenged Samuelson to name one theory in all of the social sciences that is both true and nontrivial. Several years later, Samuelson responded with David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British Political economy, political economist. He was one of the most influential of the Classical economics, classical economists along with Thomas Robert Malthus, Thomas Malthus, Ad ...

's theory of comparative advantage

In an economic model, agents have a comparative advantage over others in producing a particular good if they can produce that good at a lower relative opportunity cost or autarky price, i.e. at a lower relative marginal cost prior to trade. Comp ...

: "That it is logically true need not be argued before a mathematician; that is not trivial is attested by the thousands of important and intelligent men who have never been able to grasp the doctrine

Doctrine (from la, doctrina, meaning "teaching, instruction") is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given branch of knowledge or in a belief system ...

for themselves or to believe it after it was explained to them."

For many years, Samuelson wrote a column for ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis (businessman), Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print m ...

''. One article included Samuelson's most quoted remark and a favorite economics joke:

To prove that Wall Street is an early omen of movements still to come in GNP, commentators quote economic studies alleging that market downturns predicted four out of the last five recessions. That is an understatement. Wall Street indexes predicted nine out of the last five recessions! And its mistakes were beauties.In the early editions of his famous, bestselling economics textbook Paul Samuelson joked that GDP falls when a man "marries his maid".

Publications

''Foundations of Economic Analysis''

Paul Samuelson's book ''Foundations of Economic Analysis

''Foundations of Economic Analysis'' is a book by Paul A. Samuelson published in 1947 (Enlarged ed., 1983) by Harvard University Press. It is based on Samuelson's 1941 doctoral dissertation at Harvard University. The book sought to demonstrate a ...

'' (1946) is considered his magnum opus

A masterpiece, ''magnum opus'' (), or ''chef-d’œuvre'' (; ; ) in modern use is a creation that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of outstanding creativity, ...

. It is derived from his doctoral dissertation

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: ...

, and was inspired by the classical thermodynamic methods.Liossatos, Panagis, S. (2004)"Statistical Entropy in General Equilibrium Theory"

(p. 3). Department of Economics, Florida International University. The book proposes to: * examine underlying analogies between central features in theoretical and applied economics and * study how '' operationally meaningful theorems'' can be derived with a small number of ''analogous methods'' (p. 3), in order to derive "a general theory of economic theories" (Samuelson, 1983, p. xxvi). The book showed how these goals could be parsimoniously and fruitfully achieved, using the language of the mathematics applied to diverse subfields of economics. The book proposes two general hypotheses as sufficient for its purposes: * ''maximizing behavior'' of ''agents'' (including ''consumers'' as to utility and ''business firms'' as to profit) and * economic ''systems'' (including a market and an economy) in ''stable equilibrium''. In the first tenet, his views presented the idea that all actors, whether firms or consumers, are striving to maximize something. They could be attempting to maximize profits, utility, or wealth, but it did not matter because their efforts to improve their well-being would provide a basic model for all actors in an economic system. His second tenet was focused on providing insight on the workings of equilibrium in an economy. Generally in a market, supply would equal demand. However, he urged that this might not be the case and that the important thing to look at was a system's natural resting point. ''Foundations'' presents the question of how an equilibrium would react when it is moved from its optimal point. Samuelson was also influential in providing explanations on how the changes in certain factors can affect an economic system. For example, he could explain the economic effect of changes in taxes or new technologies. In the course of analysis, ''

comparative statics

In economics, comparative statics is the comparison of two different economic outcomes, before and after a change in some underlying exogenous variable, exogenous parameter.

As a type of ''static analysis'' it compares two different economic equ ...

'', (the analysis of changes in equilibrium of the system that result from a parameter change of the system) is formalized and clearly stated.

The chapter on welfare economics

Welfare economics is a branch of economics that uses microeconomic techniques to evaluate well-being (welfare) at the aggregate (economy-wide) level.

Attempting to apply the principles of welfare economics gives rise to the field of public econ ...

"attempt(s) to give a brief but fairly complete survey of the whole field of welfare economics" (Samuelson, 1947, p. 252). It also exposits on and develops what became commonly called the Bergson

Henri-Louis Bergson (; 18 October 1859 – 4 January 1941) was a French philosopherHenri Bergson. 2014. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 13 August 2014, from https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/61856/Henri-Bergson

–Samuelson social welfare function

In welfare economics, a social welfare function is a function that ranks social states (alternative complete descriptions of the society) as less desirable, more desirable, or indifferent for every possible pair of social states. Inputs of the fu ...

. It shows how to represent (in the maximization calculus) all real-valued economic measures of any belief system that is required to rank consistently different feasible social configurations in an ethical sense as "better than", "worse than", or "indifferent to" each other (p. 221).

''Economics''

Samuelson is also author (and since 1985 co-author) of an influential principles textbook, ''Economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and intera ...

'', first published in 1948 (19th ed. as of 2010; multiple reprints). The book sold more than 300,000 copies of each edition from 1961 through 1976 and was translated in the forty-one languages. As of 2018, it has sold over four million copies. William Nordhaus

William Dawbney Nordhaus (born May 31, 1941) is an American economist, a Sterling Professor of Economics at Yale University, best known for his work in economic modeling and climate change, and one of the 2 recipients of the 2018 Nobel Memoria ...

joined as co-author on the 12th edition (1985). Sometime before 1988, it had become the best-selling economics textbook of all time.

Samuelson was once quoted as saying, "Let those who will write the nation's laws if I can write its textbooks." Written in the shadow of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

and the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, it helped to popularize the insights of John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

. A main focus was how to avoid, or at least mitigate, the recurring slumps in economic activity.

Samuelson wrote: "It is not too much to say that the widespread creation of dictatorships and the resulting World War II stemmed in no small measure from the world's failure to meet this basic economic problem he Great Depression

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

adequately." This reflected the concern of Keynes himself with the economic causes of war and the importance of economic policy in promoting peace.

Samuelson's book was the second to introduce Keynesian economics to a wide audience, and was by far the most successful. Canadian economist Lorie Tarshis

Lorie Tarshis (22 March 1911 – 4 October 1993) was a Canadians, Canadian economist who taught mostly at Stanford University. He is credited with writing the first introductory textbook that brought Keynesian thinking into American university cl ...

, who had been a student attending Keynes's lectures at Harvard in the 1930s, published in 1947 an introductory textbook that incorporated his lecture notes, titled Elements of Economics

'.

Other publications

There are 388 papers in Samuelson's ''Collected Scientific Papers''.Stanley Fischer

Stanley Fischer ( he, סטנלי פישר; born October 15, 1943) is an Israeli American economist who served as the 20th Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve from 2014 to 2017. Fisher previously served as the 8th governor of the Bank of Israel fro ...

(1987, p. 234) writes that taken together they are "unique in their verve, breadth of economic and general knowledge, mastery of setting, and generosity of allusions to predecessors".

Samuelson was co-editor, along with William A. Barnett

William Arnold Barnett (born October 30, 1941) is an American economist, whose current work is in the fields of chaos, bifurcation, and nonlinear dynamics in socioeconomic contexts, econometric modeling of consumption and production, and the stud ...

, of ''Inside the Economist's Mind: Conversations with Eminent Economists'' (Blackwell Publishing, 2007), a collection of interviews with notable economists of the 20th century.

Criticisms

Textbook influences in higher education

Samuelson's textbook was a watershed in introducing a serious study of business cycles in the economics curriculum. It was particularly timely because it followed the Great Depression, which had only ended because of the fiscal stimulus of World War II. The study of business cycles along with the introduction of the Keynesian approach of aggregate demand set the stage for the macroeconomic revolution in America, which then diffused throughout the world through translations into every major language. Generations of students, who then became teachers, learned their first and most influential lessons from Samuelson's ''Economics.'' It attracted many imitators, who became successful in different niches of the college market. The text was not without criticism. While it praised the "mixed economy" of market and government, some found that too radical and attacked it as socialist. As a precursor to criticisms of Samuelson's ''Economics'' textbook,Lorie Tarshis

Lorie Tarshis (22 March 1911 – 4 October 1993) was a Canadians, Canadian economist who taught mostly at Stanford University. He is credited with writing the first introductory textbook that brought Keynesian thinking into American university cl ...

's textbook was attacked by trustees of, and donors to, American colleges and universities as preaching a "socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

". Piling on, William F. Buckley, Jr.

William Frank Buckley Jr. (born William Francis Buckley; November 24, 1925 – February 27, 2008) was an American public intellectual, conservative author and political commentator. In 1955, he founded ''National Review'', the magazine that stim ...

, in his 1951 book, ''God and Man at Yale

''God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of "Academic Freedom"'' is a 1951 book by William F. Buckley Jr., based on his undergraduate experiences at Yale University. Buckley, then aged 25, criticized Yale for forcing collectivist, Keynesian, an ...

,'' devoted an entire chapter, attacking both Samuelson's and Tarshis' textbooks. For Samuelson's book, Buckley drew from the ''Educational Examiner'' and credited it as an "excellent review of Samuelson's text." ("Note to Chapter Two." p. 234) For Tarshis' book, Buckley drew from Merwin K. Hart

Merwin Kimball Hart (June 25, 1881 – November 30, 1962) was an American lawyer, insurance executive, and politician from New York (state), New York who founded the "National Economic Council" and was "involved in controversial matters througho ...

's organization : "I am also grateful to the National Economic Council for its telling analysis of the Tarshis." ("Note to Chapter Two." p. 234) Buckley essentially characterized both as – in the words of Paul Davidson – "communist inspired". Buckley, for the rest of his life, defended the criticisms set forth in his book.

Economic growth of USSR

One criticism – of a concept that Samuelson added to his ''Economics'' textbook – was the comparison ofUSA

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

growth rates with those of the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, which, according to the criticism, was inconsistent with historical GNP

The gross national income (GNI), previously known as gross national product (GNP), is the total domestic and foreign output claimed by residents of a country, consisting of gross domestic product (GDP), plus factor incomes earned by foreign ...

differences. The textbook's 1967 edition (7th ed.) extrapolates (projects) the possibility of USSR/US real

Real may refer to:

Currencies

* Brazilian real (R$)

* Central American Republic real

* Mexican real

* Portuguese real

* Spanish real

* Spanish colonial real

Music Albums

* ''Real'' (L'Arc-en-Ciel album) (2000)

* ''Real'' (Bright album) (2010)

...

GNP

The gross national income (GNI), previously known as gross national product (GNP), is the total domestic and foreign output claimed by residents of a country, consisting of gross domestic product (GDP), plus factor incomes earned by foreign ...

parity between 1977 and 1995. Each subsequent edition extrapolates a date range further in the future until those graphs were dropped from the 1985 edition (12th ed.).

Phillips Curve

Samuelson, together withRobert Solow

Robert Merton Solow, GCIH (; born August 23, 1924) is an American economist whose work on the theory of economic growth culminated in the exogenous growth model named after him. He is currently Emeritus Institute Professor of Economics at the Ma ...

, helped develop and popularize the mathematics of the Phillips Curve

The Phillips curve is an economic model, named after William Phillips hypothesizing a correlation between reduction in unemployment and increased rates of wage rises within an economy. While Phillips himself did not state a linked relationship ...

. The curve suggested that unemployment and inflation were inversely related; with the advent of stagflation

In economics, stagflation or recession-inflation is a situation in which the inflation rate is high or increasing, the economic growth rate slows, and unemployment remains steadily high. It presents a dilemma for economic policy, since action ...

in the 1970s some economists including Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

and Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek ( , ; 8 May 189923 March 1992), often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian–British economist, legal theorist and philosopher who is best known for his defense of classical liberalism. Haye ...

attacked the economics based on the Phillips Curve as questionable or mistaken.

Memberships

* Member of theAmerican Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

, the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

, the United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

, fellow of Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

of London

* Fellow of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

and the British Academy

The British Academy is the United Kingdom's national academy for the humanities and the social sciences.

It was established in 1902 and received its royal charter in the same year. It is now a fellowship of more than 1,000 leading scholars span ...

;

* President (1965–68) of the International Economic Association

The International Economic Association (IEA) is an NGO established in 1950, at the instigation of the Social Sciences Department of UNESCO. To date, the IEA still shares information and maintains consultative relations with UNESCO. In 1973 the IE ...

* Member and past president (1961) of the American Economic Association

The American Economic Association (AEA) is a learned society in the field of economics. It publishes several peer-reviewed journals acknowledged in business and academia. There are some 23,000 members.

History and Constitution

The AEA was esta ...

* Member of the editorial board and past-president (1951) of the Econometric Society

The Econometric Society is an international society of academic economists interested in applying statistical tools to their field. It is an independent organization with no connections to societies of professional mathematicians or statisticians. ...

*Fellow, council member and past vice-president of the Royal Economic Society

The Royal Economic Society (RES) is a professional association that promotes the study of economic science in academia, government service, banking, industry, and public affairs. Originally established in 1890 as the British Economic Association, ...

.

*Member of Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal a ...

.

List of publications

* Samuelson, Paul A. (1947), Enlarged ed. 1983. ''Foundations of Economic Analysis

''Foundations of Economic Analysis'' is a book by Paul A. Samuelson published in 1947 (Enlarged ed., 1983) by Harvard University Press. It is based on Samuelson's 1941 doctoral dissertation at Harvard University. The book sought to demonstrate a ...

'', Harvard University Press.

* Samuelson, Paul A. (1948), '' Economics: An Introductory Analysis'', ; with William D. Nordhaus

William Dawbney Nordhaus (born May 31, 1941) is an American economist, a Sterling Professor of Economics at Yale University, best known for his work in economic modeling and climate change, and one of the 2 recipients of the 2018 Nobel Memoria ...

(since 1985), 2009, 19th ed., McGraw–Hill.

* Samuelson, Paul A. (1952), "Economic Theory and Mathematics – An Appraisal", ''American Economic Review'', 42(2), pp56–66

* * Samuelson, Paul A. (1958), ''Linear Programming and Economic Analysis'' with

Robert Dorfman

Robert Dorfman (27 October 1916 – 24 June 2002) was professor of political economy at Harvard University. Dorfman made great contributions to the fields of economics, statistics, group testing and in the process of coding theory.

His paper� ...

and Robert M. Solow

Robert Merton Solow, GCIH (; born August 23, 1924) is an American economist whose work on the theory of economic growth culminated in the exogenous growth model named after him. He is currently Emeritus Institute Professor of Economics at the Ma ...

, McGraw–Hill. Chapter-previelinks.

* * * ''The Collected Scientific Papers of Paul A. Samuelson'', MIT Press. Preview links for vol. 1–3 below. Contents links for vol. 4–7. . :Samuelson, Paul A. (1966), Vol

1

→ via

Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google Inc. that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical c ...

, 1937–mid-1964.

:Samuelson, Paul A. (1966), Vol2

→ via

Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google Inc. that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical c ...

, 1937–mid-1964.

:Samuelson, Paul A. (1972), Vol3

→ via

Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google Inc. that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical c ...

, mid-1964–1970.

:Samuelson, Paul A. (1977), Vol4

→ via

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

, 1971–76.

:Samuelson, Paul A. (1986), Vol5

→ via

Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google Inc. that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical c ...

, 1977–198Description

→ via :Samuelson, Paul A. (2011), Vol

6

1986–2009

Description

→ via

Wayback Machine

The Wayback Machine is a digital archive of the World Wide Web founded by the Internet Archive, a nonprofit based in San Francisco, California. Created in 1996 and launched to the public in 2001, it allows the user to go "back in time" and see ...

:Samuelson, Paul A. (2011), Vol7

1986–2009.

Paul A. Samuelson Papers, 1933–2010

Rubenstein Library,

Duke University

Duke University is a private research university in Durham, North Carolina. Founded by Methodists and Quakers in the present-day city of Trinity in 1838, the school moved to Durham in 1892. In 1924, tobacco and electric power industrialist James ...

. .

* Samuelson, Paul A. (1983). "My Life Philosophy," ''The American Economist'', 27(2)pp. 5-12.

* Samuelson, Paul A. (2007), ''Inside the Economist's Mind: Conversations with Eminent Economists'' with

William A. Barnett

William Arnold Barnett (born October 30, 1941) is an American economist, whose current work is in the fields of chaos, bifurcation, and nonlinear dynamics in socioeconomic contexts, econometric modeling of consumption and production, and the stud ...

, Blackwell Publishing,

* Samuelson, Paul A. (2002), ''Paul Samuelson and the Foundations of Modern Economics'', Transaction Publishers,

*Samuelson, Paul A. (2004), Macroeconomics

*Samuelson, Paul A. (2004), Microeconomics

See also

*Samuelson's inequality In statistics, Samuelson's inequality, named after the economist Paul Samuelson, also called the Laguerre–Samuelson inequality, after the mathematician Edmond Laguerre, states that every one of any collection ''x''1, ..., ''x'n'', ...

* Samuelson's Iceberg transport cost model

*Keynesian economics

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output an ...

*New Keynesian economics

New Keynesian economics is a school of macroeconomics that strives to provide microfoundations, microeconomic foundations for Keynesian economics. It developed partly as a response to criticisms of Keynesian macroeconomics by adherents of new ...

*Neo-Keynesian economics

The neoclassical synthesis (NCS), neoclassical–Keynesian synthesis, or just neo-Keynesianism was a neoclassical economics academic movement and paradigm in economics that worked towards reconciling the macroeconomic thought of John Maynard Key ...

*Neoclassical economics

Neoclassical economics is an approach to economics in which the production, consumption and valuation (pricing) of goods and services are observed as driven by the supply and demand model. According to this line of thought, the value of a good ...

* Paul Samuelson - Wikiquote

Bibliography

Annotations

References

Further reading

Description

arrow-scrollable preview

* * . * . * . * .

External links

* *by Professor

Assar Lindbeck

Carl Assar Eugén Lindbeck (26 January 1930 – 28 August 2020) was a Swedish professor of economics at Stockholm University and at the Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN).

Lindbeck was a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of ...

, Stockholm School of Economics, Award Ceremony, The Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, 1970

''A History of Economic Thought'' biography

2004 *

Yale Honorands biography, May 2005

''MIT News'', December 13, 2009 * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Samuelson, Paul 1915 births 2009 deaths Nobel laureates in Economics American Nobel laureates 20th-century American writers 21st-century American non-fiction writers 20th-century American economists 21st-century American economists American people of Polish-Jewish descent Fellows of the Econometric Society Harvard University alumni Jewish American writers Jewish American social scientists Kennedy administration personnel MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences faculty Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences National Medal of Science laureates Writers from Gary, Indiana Trade economists University of Chicago alumni Neo-Keynesian economists Presidents of the Econometric Society People from Belmont, Massachusetts Presidents of the American Economic Association Economists from Massachusetts Economists from Indiana Corresponding Fellows of the British Academy Hyde Park Academy High School alumni Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery Members of the American Philosophical Society