Pastinaca sativa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The parsnip (''

The parsnip (''

''Pastinaca sativa'' was first officially described by

''Pastinaca sativa'' was first officially described by

Parsnips resemble carrots and can be used in similar ways, but they have a sweeter taste, especially when cooked. They can be baked, boiled, pureed, roasted, fried, grilled, or steamed. When used in

Parsnips resemble carrots and can be used in similar ways, but they have a sweeter taste, especially when cooked. They can be baked, boiled, pureed, roasted, fried, grilled, or steamed. When used in

The parsnip is native to Eurasia. However, its popularity as a cultivated plant has led to the plant being spread beyond its native range, and wild populations have become established in other parts of the world. Scattered population can be found throughout North America.

The plant can form dense stands which outcompete native species, and is especially common in abandoned yards, farmland, and along roadsides and other disturbed environments. The increasing abundance of this plant is a concern particularly due to the plant's toxicity and increasing abundance in populated areas such as parks. Control is often carried out via chemical means, with glyphosate-containing herbicides considered to be effective.

The parsnip is native to Eurasia. However, its popularity as a cultivated plant has led to the plant being spread beyond its native range, and wild populations have become established in other parts of the world. Scattered population can be found throughout North America.

The plant can form dense stands which outcompete native species, and is especially common in abandoned yards, farmland, and along roadsides and other disturbed environments. The increasing abundance of this plant is a concern particularly due to the plant's toxicity and increasing abundance in populated areas such as parks. Control is often carried out via chemical means, with glyphosate-containing herbicides considered to be effective.

''Pastinaca sativa'' profile

o

missouriplants.com

Retrieved 2015-10-25.

''Pastinaca sativa'' List of Chemicals (Dr. Duke's)

Retrieved 2015-10-25. * {{Authority control Apioideae Edible Apiaceae Medicinal plants Plants described in 1753 Root vegetables Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus

The parsnip (''

The parsnip (''Pastinaca

''Pastinaca'' (parsnips) is a genus of flowering plant in the family Apiaceae, comprising 14 species. Economically, the most important member of the genus is ''Pastinaca sativa'', the parsnip.

Etymology

The etymology of the generic name ''Pastin ...

sativa'') is a root vegetable

Root vegetables are underground plant parts eaten by humans as food. Although botany distinguishes true roots (such as taproots and tuberous roots) from non-roots (such as bulbs, corms, rhizomes, and tubers, although some contain both hypocotyl a ...

closely related to carrot

The carrot ('' Daucus carota'' subsp. ''sativus'') is a root vegetable, typically orange in color, though purple, black, red, white, and yellow cultivars exist, all of which are domesticated forms of the wild carrot, ''Daucus carota'', nat ...

and parsley

Parsley, or garden parsley (''Petroselinum crispum'') is a species of flowering plant in the family Apiaceae that is native to the central and eastern Mediterranean region (Sardinia, Lebanon, Israel, Cyprus, Turkey, southern Italy, Greece, Por ...

, all belonging to the flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. The term "angiosperm" is derived from the Greek words ('container, vessel') and ('seed'), and refers to those plants th ...

family Apiaceae

Apiaceae or Umbelliferae is a family of mostly aromatic flowering plants named after the type genus ''Apium'' and commonly known as the celery, carrot or parsley family, or simply as umbellifers. It is the 16th-largest family of flowering plants ...

. It is a biennial plant

A biennial plant is a flowering plant that, generally in a temperate climate, takes two years to complete its biological life cycle.

Life cycle

In its first year, the biennal plant undergoes primary growth, during which its vegetative structures ...

usually grown as an annual

Annual may refer to:

*Annual publication, periodical publications appearing regularly once per year

** Yearbook

** Literary annual

*Annual plant

*Annual report

*Annual giving

*Annual, Morocco, a settlement in northeastern Morocco

*Annuals (band), ...

. Its long taproot

A taproot is a large, central, and dominant root from which other roots sprout laterally. Typically a taproot is somewhat straight and very thick, is tapering in shape, and grows directly downward. In some plants, such as the carrot, the taproo ...

has cream-colored skin and flesh, and, left in the ground to mature, it becomes sweeter in flavor after winter frost

Frost is a thin layer of ice on a solid surface, which forms from water vapor in an above-freezing atmosphere coming in contact with a solid surface whose temperature is below freezing, and resulting in a phase change from water vapor (a gas) ...

s. In its first growing season, the plant has a rosette of pinnate

Pinnation (also called pennation) is the arrangement of feather-like or multi-divided features arising from both sides of a common axis. Pinnation occurs in biological morphology, in crystals, such as some forms of ice or metal crystals, and in ...

, mid-green leaves. If unharvested, in its second growing season it produces a flowering stem topped by an umbel

In botany, an umbel is an inflorescence that consists of a number of short flower stalks (called pedicels) that spread from a common point, somewhat like umbrella ribs. The word was coined in botanical usage in the 1590s, from Latin ''umbella'' "p ...

of small yellow flowers, later producing pale brown, flat, winged seeds. By this time, the stem has become woody and the tap root inedible.

The parsnip is native to Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago a ...

; it has been used as a vegetable since antiquity and was cultivated by the Romans, although some confusion exists between parsnips and carrots in the literature of the time. It was used as a sweetener before the arrival of cane sugar

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refined ...

in Europe.

Parsnips are usually cooked, but can also be eaten raw. The flesh has a sweet flavor, even more so than carrots, but the taste is different. It is high in vitamin

A vitamin is an organic molecule (or a set of molecules closely related chemically, i.e. vitamers) that is an Nutrient#Essential nutrients, essential micronutrient that an organism needs in small quantities for the proper functioning of its ...

s, antioxidant

Antioxidants are compounds that inhibit oxidation, a chemical reaction that can produce free radicals. This can lead to polymerization and other chain reactions. They are frequently added to industrial products, such as fuels and lubricant ...

s, and minerals

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

(especially potassium

Potassium is the chemical element with the symbol K (from Neo-Latin ''kalium'') and atomic number19. Potassium is a silvery-white metal that is soft enough to be cut with a knife with little force. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmosphe ...

); and also contains both soluble and insoluble dietary fiber

Dietary fiber (in British English fibre) or roughage is the portion of plant-derived food that cannot be completely broken down by human digestive enzymes. Dietary fibers are diverse in chemical composition, and can be grouped generally by the ...

. Parsnips are best cultivated in deep, stone-free soil. The plant is attacked by the carrot fly and other insect pests, as well as viruses and fungal diseases, of which canker

A plant canker is a small area of dead tissue, which grows slowly, often over years. Some cankers are of only minor consequence, but others are ultimately lethal and therefore can have major economic implications for agriculture and horticultur ...

is the most serious. Handling the stems and foliage can cause a skin rash

A rash is a change of the human skin which affects its color, appearance, or texture.

A rash may be localized in one part of the body, or affect all the skin. Rashes may cause the skin to change color, itch, become warm, bumpy, chapped, dry, cr ...

if the skin is exposed to sunlight after handling.

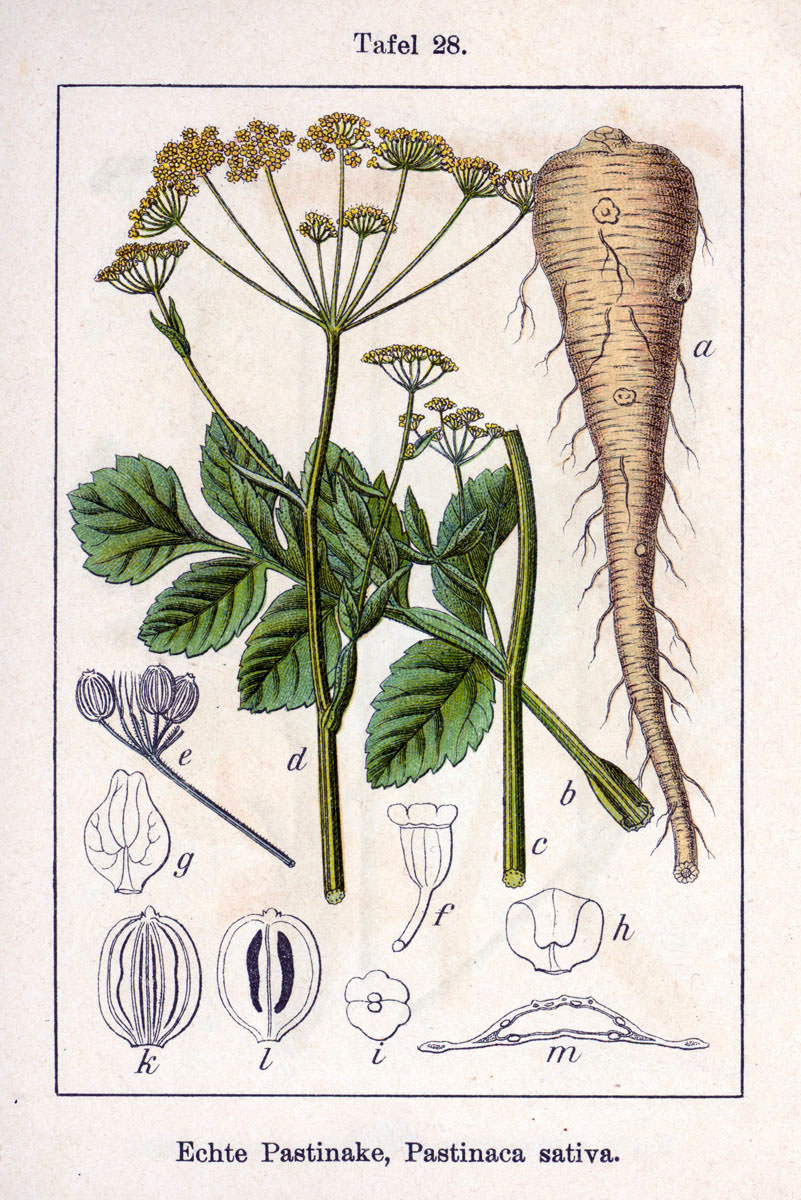

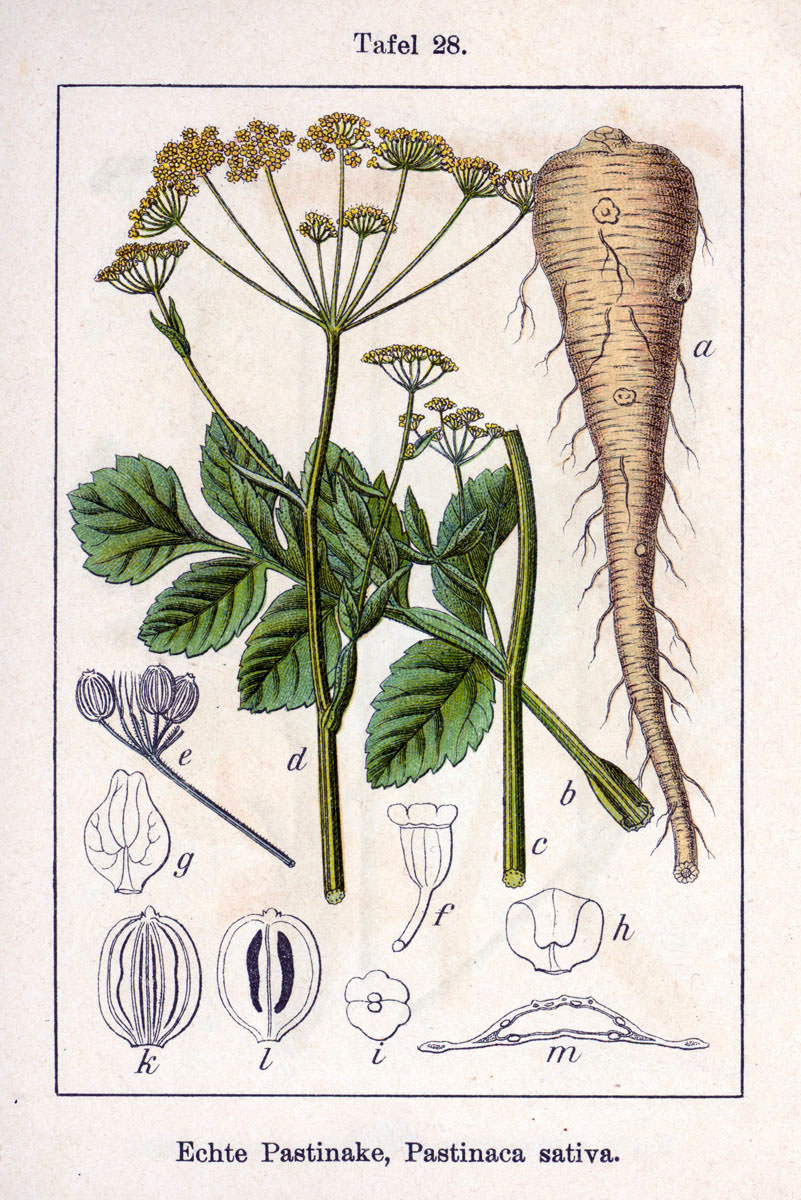

Description

The parsnip is a biennial plant with a rosette of roughly hairy leaves that have a pungent odor when crushed. Parsnips are grown for their fleshy, edible, cream-coloredtaproot

A taproot is a large, central, and dominant root from which other roots sprout laterally. Typically a taproot is somewhat straight and very thick, is tapering in shape, and grows directly downward. In some plants, such as the carrot, the taproo ...

s. The roots are generally smooth, although lateral root

Lateral roots, emerging from the pericycle (meristematic tissue), extend horizontally from the primary root (radicle) and over time makeup the iconic branching pattern of root systems. They contribute to anchoring the plant securely into the soil, ...

s sometimes form. Most are narrowly conical, but some cultivar

A cultivar is a type of cultivated plant that people have selected for desired traits and when propagated retain those traits. Methods used to propagate cultivars include: division, root and stem cuttings, offsets, grafting, tissue culture, ...

s have a more bulbous shape, which generally tends to be favored by food processors as it is more resistant to breakage. The plant's apical meristem

The meristem is a type of tissue found in plants. It consists of undifferentiated cells (meristematic cells) capable of cell division. Cells in the meristem can develop into all the other tissues and organs that occur in plants. These cells conti ...

produces a rosette of pinnate leaves, each with several pairs of leaflets with toothed margins. The lower leaves have short stems, the upper ones are stemless, and the terminal leaves have three lobes. The leaves are once- or twice-pinnate with broad, ovate, sometimes lobed leaflets with toothed margins; they grow up to long.

The petioles are grooved and have sheathed bases. The floral stem

Stem or STEM may refer to:

Plant structures

* Plant stem, a plant's aboveground axis, made of vascular tissue, off which leaves and flowers hang

* Stipe (botany), a stalk to support some other structure

* Stipe (mycology), the stem of a mushro ...

develops in the second year and can grow to more than tall. It is hairy, grooved, hollow (except at the nodes), and sparsely branched. It has a few stalkless, single-lobed leaves measuring long that are arranged in opposite pairs.

The yellow flowers are in a loose, compound umbel

In botany, an umbel is an inflorescence that consists of a number of short flower stalks (called pedicels) that spread from a common point, somewhat like umbrella ribs. The word was coined in botanical usage in the 1590s, from Latin ''umbella'' "p ...

measuring in diameter. Six to 25 straight pedicel

Pedicle or pedicel may refer to:

Human anatomy

*Pedicle of vertebral arch, the segment between the transverse process and the vertebral body, and is often used as a radiographic marker and entry point in vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty procedures

...

s are present, each measuring that support the umbellets (secondary umbels). The umbels and umbellets usually have no upper or lower bract

In botany, a bract is a modified or specialized leaf, especially one associated with a reproductive structure such as a flower, inflorescence axis or cone scale. Bracts are usually different from foliage leaves. They may be smaller, larger, or of ...

s. The flowers have tiny sepal

A sepal () is a part of the flower of angiosperms (flowering plants). Usually green, sepals typically function as protection for the flower in bud, and often as support for the petals when in bloom., p. 106 The term ''sepalum'' was coined b ...

s or lack them entirely, and measure about . They consist of five yellow petals that are curled inward, five stamen

The stamen (plural ''stamina'' or ''stamens'') is the pollen-producing reproductive organ of a flower. Collectively the stamens form the androecium., p. 10

Morphology and terminology

A stamen typically consists of a stalk called the filame ...

s, and one pistil

Gynoecium (; ) is most commonly used as a collective term for the parts of a flower that produce ovules and ultimately develop into the fruit and seeds. The gynoecium is the innermost whorl of a flower; it consists of (one or more) ''pistils'' ...

. The fruits, or schizocarp

A schizocarp is a dry fruit that, when mature, splits up into mericarps.

There are different definitions:

* Any dry fruit composed of multiple carpels that separate.

: Under this definition the mericarps can contain one or more seeds (the m ...

s, are oval and flat, with narrow wings and short, spreading styles. They are colored straw

Straw is an agricultural byproduct consisting of the dry stalks of cereal plants after the grain and chaff have been removed. It makes up about half of the yield of cereal crops such as barley, oats, rice, rye and wheat. It has a number ...

to light brown, and measure long.

Despite the slight morphological differences between the two, wild parsnip is the same taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

as the cultivated version, and the two readily cross-pollinate

Pollination is the transfer of pollen from an Stamen, anther of a plant to the stigma (botany), stigma of a plant, later enabling fertilisation and the production of seeds, most often by an animal or by Anemophily, wind. Pollinating agents can ...

. Parsnip has a chromosome number

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

of 2''n''=22.

History

Like carrots, parsnips are native to Eurasia and have been eaten there since ancient times. Zohary and Hopf note that the archaeological evidence for the cultivation of the parsnip is "still rather limited", and that Greek and Roman literary sources are a major source about its early use. They warn that "there are some difficulties in distinguishing between parsnip andcarrot

The carrot ('' Daucus carota'' subsp. ''sativus'') is a root vegetable, typically orange in color, though purple, black, red, white, and yellow cultivars exist, all of which are domesticated forms of the wild carrot, ''Daucus carota'', nat ...

(which, in Roman times, were white or purple) in classical writings since both vegetables seem to have been called ''pastinaca'' in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, yet each vegetable appears to be well under cultivation in Roman times". The parsnip was much esteemed, and the Emperor Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

accepted part of the tribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of land which the state conqu ...

payable to Rome by Germania in the form of parsnips. In Europe, the vegetable was used as a source of sugar before cane

Cane or caning may refer to:

*Walking stick or walking cane, a device used primarily to aid walking

*Assistive cane, a walking stick used as a mobility aid for better balance

*White cane, a mobility or safety device used by many people who are b ...

and beet

The beetroot is the taproot portion of a beet plant, usually known in North America as beets while the vegetable is referred to as beetroot in British English, and also known as the table beet, garden beet, red beet, dinner beet or golden beet ...

sugars were available. As ''pastinache comuni'', the "common" ''pastinaca'' figures in the long list of comestibles enjoyed by the Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

ese given by Bonvesin da la Riva Bonvesin da la Riva (; sometimes Italianized in spelling Bonvesino or Buonvicino; 1240 – c. 1313) was a well-to-do Milanese lay member of the '' Ordine degli Umiliati'' (literally, "Order of the Humble Ones"), a teacher of (Latin) grammar and a n ...

in his "Marvels of Milan" (1288).

This plant was introduced to North America simultaneously by the French colonists in Canada and the British in the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

for use as a root vegetable, but in the mid-19th century, it was replaced as the main source of starch by the potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Unit ...

and consequently was less widely cultivated.

In 1859, a new cultivar called 'Student' was developed by James Buckman at the Royal Agricultural College

;(from Virgil's Georgics)"Caring for the Fieldsand the Beasts"

, established = 2013 - University status – College

, type = Public

, president = King Charles

, vice_chancellor = Peter McCaffery

, students ...

in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. He back-crossed cultivated plants to wild stock, aiming to demonstrate how native plants could be improved by selective breeding. This experiment was so successful, 'Student' became the major variety in cultivation in the late 19th century.

Taxonomy

''Pastinaca sativa'' was first officially described by

''Pastinaca sativa'' was first officially described by Carolus Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his Nobility#Ennoblement, ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalise ...

in his 1753 work ''Species Plantarum

' (Latin for "The Species of Plants") is a book by Carl Linnaeus, originally published in 1753, which lists every species of plant known at the time, classified into genera. It is the first work to consistently apply binomial names and was the ...

''. It has acquired several synonyms

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are all ...

in its taxonomic

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

history:

*''Pastinaca fleischmannii'' Hladnik, ex D.Dietr.

*''Pastinaca opaca'' Bernh.

Johann Jakob Bernhardi (1 September 1774, in Erfurt – 13 May 1850, in Erfurt) was a German doctor and botanist.

Biography

Johann J. Bernhardi studied Medicine and Botany at the University of Erfurt, and after graduation practiced medicine for a ...

ex Hornem.

Jens Wilken Hornemann (6 March 1770 – 30 July 1841) was a Denmark, Danish botanist.

Biography

He was a lecturer at the University of Copenhagen Botanical Garden from 1801. After the death of Martin Vahl (botanist), Martin Vahl in 1804, the task ...

*''Pastinaca pratensis'' (Pers.

Christiaan Hendrik Persoon (1 February 1761 – 16 November 1836) was a German mycologist who made additions to Linnaeus' mushroom taxonomy.

Early life

Persoon was born in South Africa at the Cape of Good Hope, the third child of an imm ...

) H.Mart.

*''Pastinaca sylvestris'' Mill.

Philip Miller FRS (1691 – 18 December 1771) was an English botanist and gardener of Scottish descent. Miller was chief gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden for nearly 50 years from 1722, and wrote the highly popular '' The Gardeners Dict ...

*''Pastinaca teretiuscula'' Boiss.

Pierre Edmond Boissier (25 May 1810 Geneva – 25 September 1885 Valeyres-sous-Rances) was a Swiss prominent botanist, explorer and mathematician.

He was the son of Jacques Boissier (1784-1857) and Caroline Butini (1786-1836), daughter of Pierr ...

*''Pastinaca umbrosa'' Steven

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; ...

, ex DC.

Augustin Pyramus (or Pyrame) de Candolle (, , ; 4 February 17789 September 1841) was a Swiss botanist. René Louiche Desfontaines launched de Candolle's botanical career by recommending him at a herbarium. Within a couple of years de Candolle ...

*''Pastinaca urens'' Req. ex Godr.

Several species from other genera (''Anethum

''Anethum'' is a flowering plant genus in the family Apiaceae, native to the Middle East and the Sahara in northern Africa.

Taxonomy

The genus name comes from the Latin form of Greek words ''anison'', ''anīson'', ''anīthon'' and ''anīt ...

'', '' Elaphoboscum'', ''Peucedanum

''Peucedanum'' is a genus of flowering plant in the carrot family, Apiaceae.

Species

It contains the following species:

* '' Peucedanum abbreviatum'' E. Mey.

* '' Peucedanum acaule'' R.H.Shan & M.L.Sheh

* '' Peucedanum achaicum'' Halácsy

* '' ...

'', '' Selinum'') are likewise synonymous with the name ''Pastinaca sativa''.

Like most plants of agricultural importance, several subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

and varieties

Variety may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Entertainment formats

* Variety (radio)

* Variety show, in theater and television

Films

* ''Variety'' (1925 film), a German silent film directed by Ewald Andre Dupont

* ''Variety'' (1935 film), ...

of ''P. sativa'' have been described, but these are mostly no longer recognized as independent taxa, but rather, morphological variations of the same taxon.

*''Pastinaca sativa'' subsp. ''divaricata'' ( Desf.) Rouy & Camus

Albert Camus ( , ; ; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, and journalist. He was awarded the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44, the second-youngest recipient in history. His works ...

*''Pastinaca sativa'' subsp. ''pratensis'' (Pers.) Čelak.

*''Pastinaca sativa'' subsp. ''sylvestris'' (Mill.

Philip Miller FRS (1691 – 18 December 1771) was an English botanist and gardener of Scottish descent. Miller was chief gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden for nearly 50 years from 1722, and wrote the highly popular '' The Gardeners Dict ...

) Rouy & Camus

*''Pastinaca sativa'' subsp. ''umbrosa'' (Steven, ex DC.) Bondar. ex O.N.Korovina

*''Pastinaca sativa'' subsp. ''urens'' (Req. ex Godr.) Čelak.

*''Pastinaca sativa'' var. ''brevis'' Alef.

*''Pastinaca sativa'' var. ''edulis'' DC.

*''Pastinaca sativa'' var. ''hortensis'' Ehrh.

Jakob Friedrich Ehrhart (4 November 1742, Holderbank, Aargau – 26 June 1795) was a German botanist, a pupil of Carl Linnaeus at Uppsala University, and later director of the Botanical Garden of Hannover, where he produced several major botanical ...

ex Hoffm.

Georg Franz Hoffmann was a German Botany, botanist and lichenology, lichenologist. He was born on 13 January 1760 in Marktbreit, Germany, and died on 17 March 1826 in Moscow, Russia.

Professional career

After graduating from the University of Er ...

*''Pastinaca sativa'' var. ''longa'' Alef.

*''Pastinaca sativa'' var. ''pratensis'' Pers.

*''Pastinaca sativa'' var. ''siamensis'' Roem.

Johann Jacob Roemer (8 January 1763, Zurich – 15 January 1819) was a physician and professor of botany in Zurich, Switzerland. He was also an entomologist.

With Austrian botanist Joseph August Schultes, he published the 16th edition of Carl ...

& Schult.

Josef (Joseph) August Schultes (15 April 1773 in Vienna – 21 April 1831 in Landshut) was an Austrian botanist and professor from Vienna. Together with Johann Jacob Roemer (1763–1819), he published the 16th edition of Linnaeus' ''Systema ...

ex Alef.

In Eurasia, some authorities distinguish between cultivated and wild versions of parsnips by using subspecies ''P. s.'' ''sylvestris'' for the latter, or even elevating it to species status as ''Pastinaca sylvestris''. In Europe, various subspecies have been named based on characteristics such as the hairiness of the leaves, the extent to which the stems are angled or rounded, and the size and shape of the terminal umbel.

Uses

stew

A stew is a combination of solid food ingredients that have been cooked in liquid and served in the resultant gravy. A stew needs to have raw ingredients added to the gravy. Ingredients in a stew can include any combination of vegetables and ...

s, soup

Soup is a primarily liquid food, generally served warm or hot (but may be cool or cold), that is made by combining ingredients of meat or vegetables with stock, milk, or water. Hot soups are additionally characterized by boiling solid ing ...

s, and casserole

A casserole ( French: diminutive of , from Provençal 'pan') is a normally large deep pan or bowl a casserole is anything in a casserole pan. Hot or cold

History

Baked dishes have existed for thousands of years. Early casserole recipes ...

s, they give a rich flavour. In some cases, parsnips are boiled and the solid portions are removed from the soup or stew, leaving behind a more subtle flavour than the whole root, and starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human diets ...

to thicken the dish. Roast parsnip is considered an essential part of Christmas dinner

Christmas dinner is a meal traditionally eaten at Christmas. This meal can take place any time from the evening of Christmas Eve to the evening of Christmas Day itself. The meals are often particularly rich and substantial, in the tradition of ...

in some parts of the English-speaking world and frequently features in the traditional Sunday roast

A Sunday roast or roast dinner is a traditional meal of British and Irish origin. Although it can be consumed throughout the week, it is traditionally consumed on Sunday. It consists of roasted meat, roasted potatoes and accompaniments ...

. Parsnips can also be fried or thinly sliced and made into crisps

A potato chip (North American English; often just chip) or crisp (British and Irish English) is a thin slice of potato that has been either deep fried, baked, or air fried until crunchy. They are commonly served as a snack, side dish, or app ...

. They can be made into a wine with a taste similar to Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

.

In Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

times, parsnips were believed to be an aphrodisiac

An aphrodisiac is a substance that increases sexual desire, sexual attraction, sexual pleasure, or sexual behavior. Substances range from a variety of plants, spices, foods, and synthetic chemicals. Natural aphrodisiacs like cannabis or cocain ...

. However, parsnips do not typically feature in modern Italian cooking. Instead, they are fed to pigs, particularly those bred to make Parma ham

''Prosciutto crudo'', in English often shortened to prosciutto ( , ), is Italian uncooked, unsmoked, and dry-cured ham. ''Prosciutto crudo'' is usually served thinly sliced.

Several regions in Italy have their own variations of ''prosciutto crudo ...

.

Nutrients

A typical 100 g serving of parsnip provides offood energy

Food energy is chemical energy that animals (including humans) derive from their food to sustain their metabolism, including their muscle, muscular activity.

Most animals derive most of their energy from aerobic respiration, namely combining the ...

. Most parsnip cultivars consist of about 80% water, 5% sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double ...

, 1% protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

, 0.3% fat

In nutrition science, nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such chemical compound, compounds, most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.

The term often refers spec ...

, and 5% dietary fiber

Dietary fiber (in British English fibre) or roughage is the portion of plant-derived food that cannot be completely broken down by human digestive enzymes. Dietary fibers are diverse in chemical composition, and can be grouped generally by the ...

. The parsnip is rich in vitamins and minerals, and is particularly rich in potassium with 375 mg per 100 g. Several of the B-group vitamins are present, but levels of vitamin C are reduced in cooking. Since most of the vitamins and minerals are found close to the skin, many will be lost unless the root is finely peeled or cooked whole. During frosty weather, part of the starch is converted to sugar and the root tastes sweeter.

The consumption of parsnips has potential health benefits. They contain antioxidant

Antioxidants are compounds that inhibit oxidation, a chemical reaction that can produce free radicals. This can lead to polymerization and other chain reactions. They are frequently added to industrial products, such as fuels and lubricant ...

s such as falcarinol

Falcarinol (also known as carotatoxin or panaxynol) is a natural pesticide and fatty alcohol found in carrots ('' Daucus carota''), red ginseng (''Panax ginseng'') and ivy. In carrots, it occurs in a concentration of approximately 2 mg/kg. ...

, falcarindiol

Falcarindiol is a polyyne found in carrot roots which has antifungal activity. Falcarindiol is the main compound responsible for bitterness in carrots. Falcarindiol and other falcarindiol-type polyacetylenes are also found in many other plants of ...

, panaxydiol, and methyl-falcarindiol, which may potentially have anticancer, anti-inflammatory

Anti-inflammatory is the property of a substance or treatment that reduces inflammation or swelling. Anti-inflammatory drugs, also called anti-inflammatories, make up about half of analgesics. These drugs remedy pain by reducing inflammation as o ...

and antifungal

An antifungal medication, also known as an antimycotic medication, is a pharmaceutical fungicide or fungistatic used to treat and prevent mycosis such as athlete's foot, ringworm, candidiasis (thrush), serious systemic infections such as crypto ...

properties. The dietary fiber in parsnips is partly of the soluble and partly the insoluble type and comprises cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell wall ...

, hemicellulose

A hemicellulose (also known as polyose) is one of a number of heteropolymer, heteropolymers (matrix polysaccharides), such as arabinoxylans, present along with cellulose in almost all embryophyte, terrestrial plant cell walls.Scheller HV, Ulvskov H ...

, and lignin

Lignin is a class of complex organic polymers that form key structural materials in the support tissues of most plants. Lignins are particularly important in the formation of cell walls, especially in wood and bark, because they lend rigidity ...

. The high fiber content of parsnips may help prevent constipation

Constipation is a bowel dysfunction that makes bowel movements infrequent or hard to pass. The stool is often hard and dry. Other symptoms may include abdominal pain, bloating, and feeling as if one has not completely passed the bowel movement ...

and reduce blood cholesterol

Blood lipids (or blood fats) are lipids in the blood, either free or bound to other molecules. They are mostly transported in a protein capsule, and the density of the lipids and type of protein determines the fate of the particle and its influence ...

levels.

Etymology

Theetymology

Etymology ()The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p. 633 "Etymology /ˌɛtɪˈmɒlədʒi/ the study of the class in words and the way their meanings have changed throughout time". is the study of the history of the Phonological chan ...

of the generic name ''Pastinaca'' is not known with certainty, but is probably derived from either the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

word , meaning 'to prepare the ground for planting of the vine' or , meaning 'food'. The specific epithet

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

''sativa'' means 'sown'.

While folk etymology

Folk etymology (also known as popular etymology, analogical reformation, reanalysis, morphological reanalysis or etymological reinterpretation) is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a more famili ...

sometimes assumes the name is a mix of parsley

Parsley, or garden parsley (''Petroselinum crispum'') is a species of flowering plant in the family Apiaceae that is native to the central and eastern Mediterranean region (Sardinia, Lebanon, Israel, Cyprus, Turkey, southern Italy, Greece, Por ...

and turnip

The turnip or white turnip (''Brassica rapa'' subsp. ''rapa'') is a root vegetable commonly grown in temperate climates worldwide for its white, fleshy taproot. The word ''turnip'' is a compound of ''turn'' as in turned/rounded on a lathe and ' ...

, it actually comes from Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English p ...

, alteration (influenced by , 'turnip') of Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligib ...

(now ''panais'') from Latin '' pastinum,'' a kind of fork. The word's ending was changed to ''-nip'' by analogy with turnip because it was mistakenly assumed to be a kind of turnip.

Cultivation

The wild parsnip from which the modern cultivated varieties were derived is a plant of dry rough grassland and waste places, particularly onchalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Chalk ...

and limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

soils. Parsnips are biennials, but are normally grown as annuals. Sandy and loamy soils are preferable to silt, clay, and stony ground; the latter produces short, forked roots. Parsnip seed significantly deteriorates in viability if stored for long. Seeds are usually planted in early spring, as soon as the ground can be worked to a fine tilth

Tilth is a physical condition of soil, especially in relation to its suitability for planting or growing a crop. Factors that determine tilth include the formation and stability of aggregated soil particles, moisture content, degree of aeration, s ...

, in the position where the plants are to grow. The growing plants are thinned and kept weed-free. Harvesting begins in late fall after the first frost

Frost is a thin layer of ice on a solid surface, which forms from water vapor in an above-freezing atmosphere coming in contact with a solid surface whose temperature is below freezing, and resulting in a phase change from water vapor (a gas) ...

, and continues through winter. The rows can be covered with straw to enable the crop to be lifted during frosty weather. Low soil temperatures cause some of the starches stored in the roots to be converted into sugars, giving them a sweeter taste.

Cultivation problems

Parsnip leaves are sometimes tunnelled by thelarva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

The ...

e of the celery fly (''Euleia heraclei''). Irregular, pale brown passages can be seen between the upper and lower surfaces of the leaves. The effects are most serious on young plants, as whole leaves may shrivel and die. Treatment is by removing affected leaflets or whole leaves, or by chemical means.

The crop can be attacked by larvae of the carrot fly (''Chamaepsila rosae''). This pest feeds on the outer layers of the root, burrowing its way inside later in the season. Seedlings may be killed while larger roots are spoiled. The damage done provides a point of entry for fungal rots and canker. The fly is attracted by the smell of bruised tissue.

Parsnip is used as a food plant by the larvae of some lepidoptera

Lepidoptera ( ) is an order (biology), order of insects that includes butterfly, butterflies and moths (both are called lepidopterans). About 180,000 species of the Lepidoptera are described, in 126 Family (biology), families and 46 Taxonomic r ...

n species, including the parsnip swallowtail (''Papilio polyxenes''), the common swift moth (''Korscheltellus lupulina''), the garden dart moth (''Euxoa nigricans''), and the ghost moth

The ghost moth or ghost swift (''Hepialus humuli'') is a moth of the family Hepialidae. It is common throughout Europe, except for in the far south-east.

Female ghost moths are larger than males, and exhibit sexual dimorphism with their differ ...

(''Hepialus humuli''). The larvae of the parsnip moth (''Depressaria radiella''), native to Europe and accidentally introduced to North America in the mid-1800s, construct their webs on the umbels, feeding on flowers and partially developed seeds.

Parsnip canker is a serious disease of this crop. Black or orange-brown patches occur around the crown and shoulders of the root accompanied by cracking and hardening of the flesh. It is more likely to occur when the seed is sown into cold, wet soil, the pH of the soil is too low, or the roots have already been damaged by carrot

The carrot ('' Daucus carota'' subsp. ''sativus'') is a root vegetable, typically orange in color, though purple, black, red, white, and yellow cultivars exist, all of which are domesticated forms of the wild carrot, ''Daucus carota'', nat ...

fly larvae. Several fungi are associated with canker, including ''Phoma complanata

''Phoma'' is a genus of common coelomycetous soil fungus, fungi. It contains many plant pathogenic species.

Description

Spores are colorless and unicellular. The pycnidia are black and depressed in the tissues of the host. ''Phoma'' is arbitra ...

'', '' Ilyonectria radicicola'', '' Itersonilia pastinaceae'', and '' I. perplexans''. In Europe, '' Mycocentrospora acerina'' has been found to cause a black rot that kills the plant early. Watery soft rot, caused by ''Sclerotinia minor

''Sclerotinia minor'' (white mold) is a plant pathogen infecting Chicory, Radicchio,Steven T. Koike, Peter Gladders and Albert Paulus carrots, tomatoes, sunflowers, peanuts and lettuce.

References

External links

Index FungorumUSDA ARS Fungal ...

'' and '' S. sclerotiorum'', causes the taproot to become soft and watery. A white or buff

Buff or BUFF may refer to:

People

* Buff (surname), a list of people

* Buff (nickname), a list of people

* Johnny Buff, ring name of American world champion boxer John Lisky (1888–1955)

* Buff Bagwell, a ring name of American professional ...

-coloured mould grows on the surface. The pathogen is most common in temperate and subtropical regions that have a cool wet season.

Violet root rot caused by the fungus ''Helicobasidium purpureum

''Helicobasidium purpureum'' is a fungal plant pathogen which causes violet root rot in a number of susceptible plant hosts. It is synonymous with ''Helicobasidium brebissonii'' (Desm.) Donk. It is the teleomorph of ''Tuberculina persicina'' ...

'' sometimes affects the roots, covering them with a purplish mat to which soil particles adhere. The leaves become distorted and discoloured and the mycelium

Mycelium (plural mycelia) is a root-like structure of a fungus consisting of a mass of branching, thread-like hyphae. Fungal colonies composed of mycelium are found in and on soil and many other substrate (biology), substrates. A typical single ...

can spread through the soil between plants. Some weeds can harbour this fungus and it is more prevalent in wet, acid conditions. ''Erysiphe heraclei

''Erysiphe heraclei'' is a plant pathogen that causes powdery mildew on several species including dill

Dill (''Anethum graveolens'') is an annual herb in the celery family Apiaceae. It is the only species in the genus ''Anethum''. Dill is g ...

'' causes a powdery mildew

Powdery mildew is a fungal disease that affects a wide range of plants. Powdery mildew diseases are caused by many different species of ascomycete fungi in the order Erysiphales. Powdery mildew is one of the easier plant diseases to identify, as ...

that can cause significant crop loss. Infestation by this causes results in yellowing of the leaf and loss of foliage. Moderate temperatures and high humidity favor the development of the disease.

Several viruses

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

are known to infect the plant, including seed-borne strawberry latent ringspot virus, parsnip yellow fleck virus

The parsnip (''Pastinaca sativa'') is a root vegetable closely related to carrot and parsley, all belonging to the flowering plant family Apiaceae. It is a biennial plant usually grown as an Annual plant, annual. Its long taproot has cream-co ...

, parsnip leafcurl virus, parsnip mosaic potyvirus, and potyvirus celery mosaic virus

''Potyvirus'' is a genus of positive-strand RNA viruses in the family ''Potyviridae''. Plants serve as natural hosts. The genus is named after member virus ''potato virus Y''. Potyviruses account for about thirty percent of the currently known p ...

. The latter causes clearing or yellowing of the areas of the leaf immediately beside the veins, the appearance of ochre mosaic spots, and crinkling of the leaves in infected plants.

Toxicity

The shoots and leaves of parsnip must be handled with care, as its sap containsfuranocoumarin

The furanocoumarins, or furocoumarins, are a class of organic chemical compounds produced by a variety of plants. Most of the plant species found to contain furanocoumarins belong to a handful of plant families. The families Apiaceae and Rutacea ...

s, phototoxic

Phototoxicity, also called photoirritation, is a chemically induced skin irritation, requiring light, that does not involve the immune system. It is a type of photosensitivity.

The skin response resembles an exaggerated sunburn. The involved chemi ...

chemicals that cause blisters on the skin when it is exposed to sunlight, a condition known as phytophotodermatitis

Phytophotodermatitis, also known as berloque dermatitis or margarita photodermatitis, is a cutaneous phototoxic inflammatory reaction resulting from contact with a light-sensitizing botanical agent followed by exposure to ultraviolet light (from t ...

. It shares this property with many of its relatives in the carrot family. Symptoms include redness, burning, and blisters; afflicted areas can remain sensitive and discolored for up to two years. Reports of gardeners experiencing toxic symptoms after coming into contact with foliage have been made but these have been small in number compared to the number of people who grow the crop. The problem is most likely to occur on a sunny day when gathering foliage or pulling up old plants that have gone to seed. The symptoms have mostly been mild to moderate. Risk can be reduced by wearing long pants and sleeves to avoid exposure, and avoiding sunlight after any suspected exposure.

The toxic properties of parsnip extracts are resistant to heating, and to periods of storage lasting several months. Toxic symptoms can also affect livestock and poultry in parts of their bodies where their skin is exposed. Polyyne

In organic chemistry, a polyyne () is any organic compound with alternating single and triple bonds; that is, a series of consecutive alkynes, with ''n'' greater than 1. These compounds are also called polyacetylenes, especially in the natural p ...

s can be found in Apiaceae vegetables such as parsnip, and they show cytotoxic

Cytotoxicity is the quality of being toxic to cells. Examples of toxic agents are an immune cell or some types of venom, e.g. from the puff adder (''Bitis arietans'') or brown recluse spider (''Loxosceles reclusa'').

Cell physiology

Treating cells ...

activities.

Invasivity

The parsnip is native to Eurasia. However, its popularity as a cultivated plant has led to the plant being spread beyond its native range, and wild populations have become established in other parts of the world. Scattered population can be found throughout North America.

The plant can form dense stands which outcompete native species, and is especially common in abandoned yards, farmland, and along roadsides and other disturbed environments. The increasing abundance of this plant is a concern particularly due to the plant's toxicity and increasing abundance in populated areas such as parks. Control is often carried out via chemical means, with glyphosate-containing herbicides considered to be effective.

The parsnip is native to Eurasia. However, its popularity as a cultivated plant has led to the plant being spread beyond its native range, and wild populations have become established in other parts of the world. Scattered population can be found throughout North America.

The plant can form dense stands which outcompete native species, and is especially common in abandoned yards, farmland, and along roadsides and other disturbed environments. The increasing abundance of this plant is a concern particularly due to the plant's toxicity and increasing abundance in populated areas such as parks. Control is often carried out via chemical means, with glyphosate-containing herbicides considered to be effective.

See also

* Root parsley, a similar-looking vegetableReferences

External links

General

''Pastinaca sativa'' profile

o

missouriplants.com

Retrieved 2015-10-25.

''Pastinaca sativa'' List of Chemicals (Dr. Duke's)

Retrieved 2015-10-25. * {{Authority control Apioideae Edible Apiaceae Medicinal plants Plants described in 1753 Root vegetables Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus