The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, and has also served as the

head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

or

sovereign of the

Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

and later the

Vatican City State since the eighth century.

From a Catholic viewpoint, the

primacy of the bishop of Rome is largely derived from his role as the

apostolic successor to

Saint Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupat ...

, to whom

primacy was conferred by Jesus, who gave Peter the

Keys of Heaven and the powers of "binding and loosing", naming him as the "rock" upon which the Church would be built. The current pope is

Francis, who was

elected Elected may refer to:

* "Elected" (song), by Alice Cooper, 1973

* ''Elected'' (EP), by Ayreon, 2008

*The Elected, an American indie rock band

See also

*Election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population ...

on 13 March 2013.

While his office is called the papacy, the

jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' + 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, areas of jurisdiction apply to local, state, and federal levels.

J ...

of the

episcopal see is called the

Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

. It is the Holy See that is the

sovereign entity

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

by

international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

headquartered in the distinctively independent Vatican City State, a

city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

which forms a geographical

enclave within the connurbation of Rome, established by the

Lateran Treaty

The Lateran Treaty ( it, Patti Lateranensi; la, Pacta Lateranensia) was one component of the Lateran Pacts of 1929, agreements between the Kingdom of Italy under King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy and the Holy See under Pope Pius XI to settle ...

in 1929 between Italy and the Holy See to ensure its and spiritual independence. The Holy See is recognized by its adherence at various levels to international organizations and by means of its diplomatic relations and political accords with many independent states.

According to

Catholic tradition

Sacred tradition is a theological term used in Christian theology. According to the theology of the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian churches, sacred tradition is the foundation of the doctrinal and spiritual authority of ...

, the

apostolic see

An apostolic see is an episcopal see whose foundation is attributed to one or more of the apostles of Jesus or to one of their close associates. In Catholicism the phrase, preceded by the definite article and usually capitalized, refers to the ...

of

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

was founded by Saint Peter and

Saint Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

in the first century. The papacy is one of the most enduring institutions in the world and has had a prominent part in

human history

Human history, also called world history, is the narrative of humanity's past. It is understood and studied through anthropology, archaeology, genetics, and linguistics. Since the invention of writing, human history has been studied throug ...

. In ancient times, the popes helped spread Christianity and intervened to find resolutions in various doctrinal disputes.

In the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, they played a role of secular importance in Western Europe, often acting as arbitrators between Christian monarchs.

[Faus, José Ignacio Gonzáles. "''Autoridade da Verdade – Momentos Obscuros do Magistério Eclesiástico''". Capítulo VIII: Os papas repartem terras – Pág.: 64–65 e Capítulo VI: O papa tem poder temporal absoluto – Pág.: 49–55. Edições Loyola. . Embora Faus critique profundamente o poder temporal dos papas ("''Mais uma vez isso salienta um dos maiores inconvenientes do status político dos sucessores de Pedro''" – pág.: 64), ele também admite um papel secular positivo por parte dos papas ("''Não podemos negar que intervenções papais desse gênero evitaram mais de uma guerra na Europa''" – pág.: 65).] In addition to the expansion of

Christian faith and doctrine, modern popes are involved in

ecumenism and

interfaith dialogue

Interfaith dialogue refers to cooperative, constructive, and positive interaction between people of different religious traditions (i.e. "faiths") and/or spiritual or humanistic beliefs, at both the individual and institutional levels. It is ...

,

charitable work, and the defense of human rights.

Over time, the papacy accrued

broad secular and political influence, ultimately rivaling those of territorial rulers. In recent centuries, the temporal authority of the papacy has declined and the office is now largely focused on religious matters.

By contrast, papal claims of spiritual authority have been increasingly firmly expressed over time, culminating in 1870 with the proclamation of the

dogma

Dogma is a belief or set of beliefs that is accepted by the members of a group without being questioned or doubted. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Isla ...

of

papal infallibility

Papal infallibility is a dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, in virtue of the promise of Jesus to Peter, the Pope when he speaks '' ex cathedra'' is preserved from the possibility of error on doctrine "initially given to the apos ...

for rare occasions when the pope speaks —literally "from the

chair (of Saint Peter)"—to issue a formal definition of

faith

Faith, derived from Latin ''fides'' and Old French ''feid'', is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or In the context of religion, one can define faith as " belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

Religious people ofte ...

or morals.

The pope is considered one of the world's most powerful people due to the extensive diplomatic, cultural, and spiritual influence of his position on both 1.3 billion Catholics and those outside the Catholic faith, and because he heads the world's largest non-government provider of

education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty ...

and

health care,

with a vast network of charities.

History

Title and etymology

The word ''

pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

'' derives from

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

(), meaning 'father'. In the early centuries of Christianity, this title was applied, especially in the East, to all bishops

and other senior clergy, and later became reserved in the West to the bishop of Rome during the reign of

Pope Leo I (440–461), a reservation made official only in the 11th century. The earliest record of the use of the title of 'pope' was in regard to the by then deceased

patriarch of Alexandria,

Heraclas (232–248). The earliest recorded use of the title "pope" in English dates to the mid-10th century, when it was used in reference to the 7th century Roman

Pope Vitalian

Pope Vitalian ( la, Vitalianus; died 27 January 672) was the bishop of Rome from 30 July 657 to his death. His pontificate was marked by the dispute between the papacy and the imperial government in Constantinople over Monothelitism, which Rome ...

in an Old English translation of

Bede's .

Position within the Church

The Catholic Church teaches that the pastoral office, the office of

shepherding the Church, that was held by the apostles, as a group or "college" with

Saint Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupat ...

as their head, is now held by their successors, the bishops, with the bishop of Rome (the pope) as their head. Thus, is derived another title by which the pope is known, that of "supreme pontiff".

The Catholic Church teaches that Jesus personally appointed Peter as the visible head of the Church, and the Catholic Church's dogmatic constitution makes a clear distinction between apostles and bishops, presenting the latter as the successors of the former, with the pope as successor of Peter, in that he is head of the bishops as Peter was head of the apostles. Some historians argue against the notion that Peter was the first bishop of Rome, noting that the episcopal see in Rome can be traced back no earlier than the 3rd century.

The writings of the

Church Father

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical pe ...

Irenaeus

Irenaeus (; grc-gre, Εἰρηναῖος ''Eirēnaios''; c. 130 – c. 202 AD) was a Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christian communities in the southern regions of present-day France and, more widely, for the dev ...

, who wrote around 180 AD, reflect a belief that Peter "founded and organized" the Church at Rome. Moreover, Irenaeus was not the first to write of Peter's presence in the early Roman Church. The church of Rome wrote in a letter to the Corinthians (which is traditionally attributed to

Clement of Rome ) about the persecution of Christians in Rome as the "struggles in our time" and presented to the Corinthians its heroes, "first, the greatest and most just columns", the "good apostles" Peter and Paul.

[Gröber, 510] St. Ignatius of Antioch

Ignatius of Antioch (; Ancient Greek, Greek: Ἰγνάτιος Ἀντιοχείας, ''Ignátios Antiokheías''; died c. 108/140 AD), also known as Ignatius Theophorus (, ''Ignátios ho Theophóros'', lit. "the God-bearing"), was an early Ch ...

wrote shortly after Clement; in his letter from the city of Smyrna to the Romans he said he would not command them as Peter and Paul did.

Given this and other evidence, such as Emperor Constantine's erection of the "Old St. Peter's Basilica" on the location of St. Peter's tomb, as held and given to him by Rome's Christian community, many scholars agree that Peter was martyred in Rome under

Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unti ...

, although some scholars argue that he may have been martyred in Palestine.

Though the interpretation of the historical record in open in various details to continuing debate, first-century Christian communities may have had a group of presbyter-bishops functioning as guides of their local churches. Gradually, episcopal sees were established in metropolitan areas.

Antioch may have developed such a structure before Rome.

In Rome, there were over time at various junctures rival claimants to be the rightful bishop, though again Irenaeus stressed the validity of one line of bishops from the time of St. Peter up to his contemporary

Pope Victor I and listed them. Some writers claim that the emergence of a single bishop in Rome probably did not occur until the middle of the 2nd century. In their view, Linus, Cletus and Clement were possibly prominent presbyter-bishops, but not necessarily monarchical bishops.

Documents of the 1st century and early second century indicate that the bishop of Rome had some kind of pre-eminence and prominence in the Church as a whole, as even a letter from the bishop, or patriarch, of Antioch acknowledged the Bishop of Rome as "a first among equals", though the detail of what this meant is unclear.

Early Christianity ()

Sources suggest that at first, the terms 'episcopos' and 'presbyter' were used interchangeably, with the consensus among scholars being that by the turn of the 1st and 2nd centuries, local congregations were led by bishops and presbyters, whose duties of office overlapped or were indistinguishable from one another. Some say that there was probably "no single 'monarchical' bishop in Rome before the middle of the 2nd century...and likely later."

Other scholars and historians disagree, citing the historical records of St. Ignatius of Antioch (d. 107) and St. Irenaeus, who recorded the linear succession of bishops of Rome (the popes) up until their own times. However, 'historical' records written by those wanting to show an unbroken line of popes would naturally do so, and there are no objective substantiating documents. They also cite the importance accorded to the bishops of Rome in the

ecumenical council

An ecumenical council, also called general council, is a meeting of bishops and other church authorities to consider and rule on questions of Christian doctrine, administration, discipline, and other matters in which those entitled to vote ar ...

s, including early councils.

In the early Christian era, Rome and a few other cities had claims on the leadership of worldwide Church.

James the Just, known as "the brother of the Lord", served as head of the

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

church, which is still honored as the "Mother Church" in Orthodox tradition.

Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

had been a center of Jewish learning and became a center of Christian learning. Rome had a large congregation early in the apostolic period whom Paul the Apostle addressed in his

Epistle to the Romans, and according to tradition Paul was martyred there.

During the 1st century of the Church (), the Roman capital became recognized as a Christian center of exceptional importance. The church there, at the end of the 1st century, wrote an epistle to the Church in

Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government refor ...

intervening in a major dispute, and apologizing for not having taken action earlier. However, there are only a few other references of that time to recognition of the

authoritative primacy of the

Roman See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rom ...

outside of Rome.

In the

Ravenna Document of 13 October 2007, theologians chosen by the Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox Churches stated: "41. Both sides agree ... that Rome, as the Church that 'presides in love' according to the phrase of St Ignatius of Antioch, occupied the first place in the , and that the bishop of Rome was therefore the among the patriarchs. Translated into English, the statement means "first among equals".

What form that should take is still a matter of disagreement, just as it was when the Catholic and Orthodox Churches split in the Great East-West Schism. They also disagree on the interpretation of the historical evidence from this era regarding the prerogatives of the bishop of Rome as , a matter that was already understood in different ways in the first millennium."

In the late 2nd century AD, there were more manifestations of Roman authority over other churches. In 189, assertion of the primacy of the Church of Rome may be indicated in Irenaeus's ''

Against Heresies'' (3:3:2): "With

he Church of Rome because of its superior origin, all the churches must agree ... and it is in her that the faithful everywhere have maintained the apostolic tradition." In AD 195, Pope Victor I, in what is seen as an exercise of Roman authority over other churches, excommunicated the

Quartodecimans for observing Easter on the 14th of

Nisan, the date of the Jewish

Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holiday that celebrates the Biblical story of the Israelites escape from slavery in Egypt, which occurs on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nisan, the first month of Aviv, or spring. ...

, a tradition handed down by

John the Evangelist

John the Evangelist ( grc-gre, Ἰωάννης, Iōánnēs; Aramaic: ܝܘܚܢܢ; Ge'ez: ዮሐንስ; ar, يوحنا الإنجيلي, la, Ioannes, he, יוחנן cop, ⲓⲱⲁⲛⲛⲏⲥ or ⲓⲱ̅ⲁ) is the name traditionally given ...

(see

Easter controversy). Celebration of Easter on a Sunday, as insisted on by the pope, is the system that has prevailed (see

computus).

Nicaea to East-West Schism (325–1054)

The

Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

in 313 granted freedom to all religions in the Roman Empire, beginning the

Peace of the Church

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

. In 325, the

First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

condemned

Arianism, declaring

trinitarianism

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the ...

dogmatic, and in its sixth canon recognized the special role of the Sees of Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch. Great defenders of Trinitarian faith included the popes, especially

Liberius, who was exiled to

Berea by

Constantius II

Constantius II (Latin: ''Flavius Julius Constantius''; grc-gre, Κωνστάντιος; 7 August 317 – 3 November 361) was Roman emperor from 337 to 361. His reign saw constant warfare on the borders against the Sasanian Empire and Germanic ...

for his Trinitarian faith,

Damasus I, and several other bishops.

[Alves J. ''Os Santos de Cada Dia'' (10 edição). Editora Paulinas.pp. 296, 696, 736. .]

In 380, the

Edict of Thessalonica

The Edict of Thessalonica (also known as ''Cunctos populos''), issued on 27 February AD 380 by Theodosius I, made the Catholicism of Nicene Christians the state church of the Roman Empire.

It condemned other Christian creeds such as Arianism ...

declared

Nicene Christianity

The original Nicene Creed (; grc-gre, Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας; la, Symbolum Nicaenum) was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381, it was amended at the First Council of Constantinople. The amended form is ...

to be the state religion of the empire, with the name "Catholic Christians" reserved for those who accepted that faith. While the civil power in the

Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

controlled the church, and the

patriarch of Constantinople, the capital, wielded much power,

[Gaeta, Franco; Villani, Pasquale. ''Corso di Storia, per le scuole medie superiori''. Milão. Editora Principato. 1986.] in the

Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

, the bishops of Rome were able to consolidate the influence and power they already possessed.

After the

fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vas ...

,

barbarian tribes were converted to Arian Christianity or Catholicism;

[Le Goff, Jacques (2000). ''Medieval Civilization''. Barnes & Noble. p. 14, 21. .] Clovis I, king of the

Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

, was the first important barbarian ruler to convert to Catholicism rather than Arianism, allying himself with the papacy. Other tribes, such as the

Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

, later abandoned Arianism in favour of Catholicism.

Middle Ages

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the pope served as a source of authority and continuity.

Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregor ...

() administered the church with strict reform. From an ancient senatorial family, Gregory worked with the stern judgement and discipline typical of ancient Roman rule. Theologically, he represents the shift from the classical to the medieval outlook; his popular writings are full of dramatic

miracle

A miracle is an event that is inexplicable by natural or scientific lawsOne dictionary define"Miracle"as: "A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divi ...

s, potent

relics,

demons,

angel

In various theistic religious traditions an angel is a supernatural spiritual being who serves God.

Abrahamic religions often depict angels as benevolent celestial intermediaries between God (or Heaven) and humanity. Other roles inclu ...

s, ghosts, and the

approaching end of the world.

Gregory's successors were largely dominated by the

exarch of Ravenna

The Exarchate of Ravenna ( la, Exarchatus Ravennatis; el, Εξαρχάτο της Ραβέννας) or of Italy was a lordship of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) in Italy, from 584 to 751, when the last exarch was put to death by the ...

, the

Byzantine emperor

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as le ...

's representative in the

Italian Peninsula. These humiliations, the weakening of the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

in the face of the

Muslim conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He estab ...

, and the inability of the emperor to protect the papal estates against the

Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 and ...

, made

Pope Stephen II turn from Emperor

Constantine V

Constantine V ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντῖνος, Kōnstantīnos; la, Constantinus; July 718 – 14 September 775), was Byzantine emperor from 741 to 775. His reign saw a consolidation of Byzantine security from external threats. As an able ...

. He appealed to the Franks to protect his lands.

Pepin the Short

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of ...

subdued the Lombards and donated Italian land to the papacy. When

Pope Leo III

Pope Leo III (died 12 June 816) was bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death. Protected by Charlemagne from the supporters of his predecessor, Adrian I, Leo subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position b ...

crowned

Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

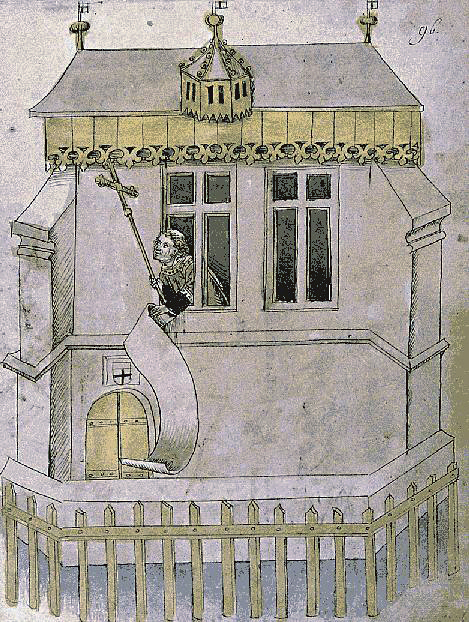

(800) as emperor, he established the precedent that, in Western Europe, no man would be emperor without being crowned by a pope.

The low point of the papacy was 867–1049. This period includes the

Saeculum obscurum

''Saeculum obscurum'' (, "the dark age/century"), also known as the Pornocracy or the Rule of the Harlots, was a period in the history of the Papacy during the first two-thirds of the 10th century, following the chaos after the death of Formosu ...

, the

Crescentii

The Crescentii (in modern Italian Crescenzi) were a baronial family, attested in Rome from the beginning of the 10th century and which in fact ruled the city and the election of the popes until the beginning of the 11th century.

History

Several ...

era, and the

Tusculan Papacy

The Tusculan Papacy was a period of papal history from 1012 to 1048 where three successive relatives of the counts of Tusculum were installed as pope.

Background

Count Theophylact I of Tusculum, his wife Theodora, and daughter Marozia held great ...

. The papacy came under the control of vying political factions. Popes were variously imprisoned, starved, killed, and deposed by force. The family of a certain papal official made and unmade popes for fifty years. The official's great-grandson,

Pope John XII

Pope John XII ( la, Ioannes XII; c. 930/93714 May 964), born Octavian, was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 16 December 955 to his death in 964. He was related to the counts of Tusculum, a powerful Roman family which had do ...

, held orgies of debauchery in the

Lateran Palace

The Lateran Palace ( la, Palatium Lateranense), formally the Apostolic Palace of the Lateran ( la, Palatium Apostolicum Lateranense), is an ancient palace of the Roman Empire and later the main papal residence in southeast Rome.

Located on St. ...

. Emperor

Otto I

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), traditionally known as Otto the Great (german: Otto der Große, it, Ottone il Grande), was East Francia, East Frankish king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the olde ...

had John accused in an ecclesiastical court, which deposed him and elected a layman as

Pope Leo VIII

Pope Leo VIII ( 915 – 1 March 965) was a Roman prelate who claimed the Holy See from 963 until 964 in opposition to John XII and Benedict V and again from 23 June 964 to his death. Today he is considered by the Catholic Church to have bee ...

. John mutilated the Imperial representatives in Rome and had himself reinstated as pope.

Conflict between the Emperor and the papacy continued, and eventually dukes in league with the emperor were buying bishops and popes almost openly.

In 1049,

Leo IX

Pope Leo IX (21 June 1002 – 19 April 1054), born Bruno von Egisheim-Dagsburg, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 February 1049 to his death in 1054. Leo IX is considered to be one of the most historically ...

traveled to the major cities of Europe to deal with the church's moral problems firsthand, notably

simony

Simony () is the act of selling church offices and roles or sacred things. It is named after Simon Magus, who is described in the Acts of the Apostles as having offered two disciples of Jesus payment in exchange for their empowering him to imp ...

and

clerical marriage

Clerical marriage is practice of allowing Christian clergy (those who have already been ordained) to marry. This practice is distinct from allowing married persons to become clergy. Clerical marriage is admitted among Protestants, including both A ...

and

concubinage

Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between a man and a woman in which the couple does not want, or cannot enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar but mutually exclusive.

Concubin ...

. With his long journey, he restored the prestige of the papacy in Northern Europe.

From the 7th century it became common for European monarchies and nobility to found churches and perform

investiture

Investiture (from the Latin preposition ''in'' and verb ''vestire'', "dress" from ''vestis'' "robe") is a formal installation or ceremony that a person undergoes, often related to membership in Christian religious institutes as well as Christian k ...

or deposition of clergy in their states and fiefdoms, their personal interests causing corruption among the clergy.

[''História Global Brasil e Geral''. Pág.: 101, 130, 149, 151, 159. Volume único. Gilberto Cotrim. ][MOVIMENTOS DE RENOVAÇÃO E REFORMA](_blank)

. 1 October 2009. This practice had become common because often the prelates and secular rulers were also participants in public life.

To combat this and other practices that had corrupted the Church between the years 900 and 1050, centres emerged promoting ecclesiastical reform, the most important being the

Abbey of Cluny

Cluny Abbey (; , formerly also ''Cluni'' or ''Clugny''; ) is a former Benedictine monastery in Cluny, Saône-et-Loire, France. It was dedicated to Saint Peter.

The abbey was constructed in the Romanesque architectural style, with three churches ...

, which spread its ideals throughout Europe.

This reform movement gained strength with the election of

Pope Gregory VII

Pope Gregory VII ( la, Gregorius VII; 1015 – 25 May 1085), born Hildebrand of Sovana ( it, Ildebrando di Soana), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 22 April 1073 to his death in 1085. He is venerated as a saint ...

in 1073, who adopted a series of measures in the movement known as the

Gregorian Reform

The Gregorian Reforms were a series of reforms initiated by Pope Gregory VII and the circle he formed in the papal curia, c. 1050–80, which dealt with the moral integrity and independence of the clergy. The reforms are considered to be nam ...

, in order to fight strongly against simony and the abuse of civil power and try to restore ecclesiastical discipline, including

clerical celibacy

Clerical celibacy is the requirement in certain religions that some or all members of the clergy be unmarried. Clerical celibacy also requires abstention from deliberately indulging in sexual thoughts and behavior outside of marriage, because the ...

.

This conflict between popes and secular autocratic rulers such as the Holy Roman Emperor

Henry IV and King

Henry I of England

Henry I (c. 1068 – 1 December 1135), also known as Henry Beauclerc, was King of England from 1100 to his death in 1135. He was the fourth son of William the Conqueror and was educated in Latin and the liberal arts. On William's death in ...

, known as the

Investiture controversy

The Investiture Controversy, also called Investiture Contest (German: ''Investiturstreit''; ), was a conflict between the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops (investiture) and abbots of monast ...

, was only resolved in 1122, by the

Concordat of Worms

The Concordat of Worms(; ) was an agreement between the Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire which regulated the procedure for the appointment of bishops and abbots in the Empire. Signed on 23 September 1122 in the German city of Worms by P ...

, in which

Pope Callixtus II

Pope Callixtus II or Callistus II ( – 13 December 1124), born Guy of Burgundy, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1 February 1119 to his death in 1124. His pontificate was shaped by the Investiture Controversy, ...

decreed that clerics were to be invested by clerical leaders, and temporal rulers by lay investiture.

Soon after,

Pope Alexander III

Pope Alexander III (c. 1100/1105 – 30 August 1181), born Roland ( it, Rolando), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 September 1159 until his death in 1181.

A native of Siena, Alexander became pope after a con ...

began reforms that would lead to the establishment of

canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

.

Since the beginning of the 7th century, the

Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

had conquered much of the southern

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

, and represented a threat to Christianity. In 1095, the Byzantine emperor,

Alexios I Komnenos

Alexios I Komnenos ( grc-gre, Ἀλέξιος Κομνηνός, 1057 – 15 August 1118; Latinized Alexius I Comnenus) was Byzantine emperor from 1081 to 1118. Although he was not the first emperor of the Komnenian dynasty, it was during ...

, asked for military aid from

Pope Urban II

Pope Urban II ( la, Urbanus II; – 29 July 1099), otherwise known as Odo of Châtillon or Otho de Lagery, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 March 1088 to his death. He is best known for convening th ...

in the ongoing

Byzantine–Seljuq wars. Urban, at the

council of Clermont

The Council of Clermont was a mixed synod of ecclesiastics and laymen of the Catholic Church, called by Pope Urban II and held from 17 to 27 November 1095 at Clermont, Auvergne, at the time part of the Duchy of Aquitaine.

Pope Urban's spee ...

, called the

First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ru ...

to assist the Byzantine Empire to regain the old Christian territories, especially Jerusalem.

East–West Schism to Reformation (1054–1517)

With the

East–West Schism

The East–West Schism (also known as the Great Schism or Schism of 1054) is the ongoing break of communion between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches since 1054. It is estimated that, immediately after the schism occurred, a ...

, the

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

and the Catholic Church split definitively in 1054. This fracture was caused more by political events than by

slight divergences of creed. Popes had galled the Byzantine emperors by siding with the king of the Franks, crowning a rival Roman emperor, appropriating the

Exarchate of Ravenna

The Exarchate of Ravenna ( la, Exarchatus Ravennatis; el, Εξαρχάτο της Ραβέννας) or of Italy was a lordship of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) in Italy, from 584 to 751, when the last exarch was put to death by the ...

, and driving into Greek Italy.

In the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, popes struggled with monarchs over power.

From 1309 to 1377, the pope resided not in Rome but in

Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label=Provençal dialect, Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse Departments of France, department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region of So ...

. The

Avignon Papacy

The Avignon Papacy was the period from 1309 to 1376 during which seven successive popes resided in Avignon – at the time within the Kingdom of Burgundy-Arles, Kingdom of Arles, part of the Holy Roman Empire; now part of France – rather than i ...

was notorious for greed and corruption. During this period, the pope was effectively an ally of the

Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. ...

, alienating France's enemies, such as the

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On 1 ...

.

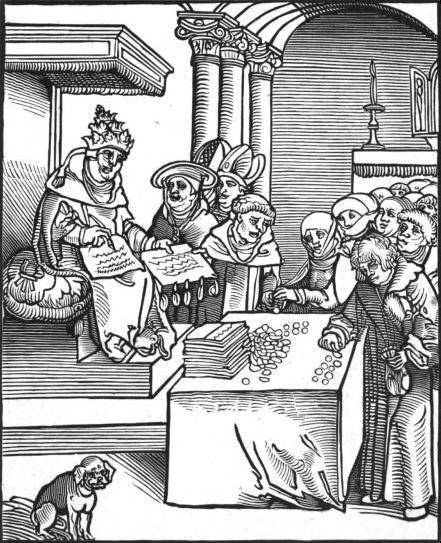

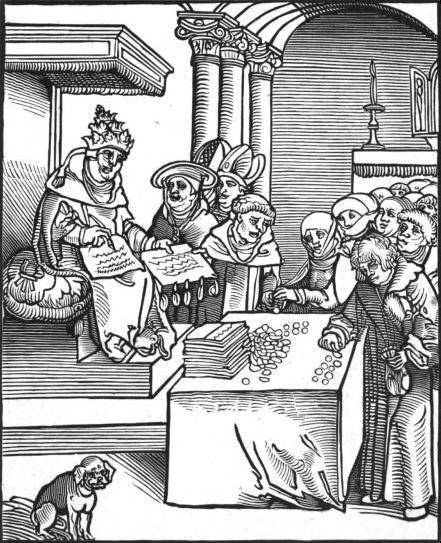

The pope was understood to have the power to draw on the

Treasury of Merit The treasury of merit or treasury of the Church (''thesaurus ecclesiae''; el, θησαυρός, ''thesaurós'', treasure; el, ἐκκλησία, ''ekklēsía''‚ convening, congregation, parish) consists, according to Catholic belief, of the mer ...

built up by the saints and by Christ, so that he could grant

indulgence

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (, from , 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for sins". The '' Catechism of the Catholic Church'' describes an indulgence as "a remission before God o ...

s, reducing one's time in

purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French) is, according to the belief of some Christian denominations (mostly Catholic), an intermediate state after physical death for expiatory purification. The process of purgatory ...

. The concept that a monetary fine or donation accompanied contrition, confession, and prayer eventually gave way to the common assumption that indulgences depended on a simple monetary contribution. The popes condemned misunderstandings and abuses, but were too pressed for income to exercise effective control over indulgences.

Popes also contended with the

cardinals

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

, who sometimes attempted to assert the authority of

Catholic Ecumenical Councils

According to the Catholic Church, a Church Council is ecumenical ("world-wide"), if it is "a solemn congregation of the Catholic bishops of the world at the invitation of the Pope to decide on matters of the Church with him".

In addition to ec ...

over the pope's.

Conciliarism

Conciliarism was a reform movement in the 14th-, 15th- and 16th-century Catholic Church which held that supreme authority in the Church resided with an ecumenical council, apart from, or even against, the pope.

The movement emerged in response to ...

holds that the supreme authority of the church lies with a General Council, not with the pope. Its foundations were laid early in the 13th century, and it culminated in the 15th century with

Jean Gerson

Jean Charlier de Gerson (13 December 1363 – 12 July 1429) was a French scholar, educator, reformer, and poet, Chancellor of the University of Paris, a guiding light of the conciliar movement and one of the most prominent theologians at the Co ...

as its leading spokesman. The failure of Conciliarism to gain broad acceptance after the 15th century is taken as a factor in the

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

.

["Conciliar theory". Cross, FL, ed. ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church''. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005.]

Various

Antipope

An antipope ( la, antipapa) is a person who makes a significant and substantial attempt to occupy the position of Bishop of Rome and leader of the Catholic Church in opposition to the legitimately elected pope. At times between the 3rd and mid- ...

s challenged papal authority, especially during the

Western Schism

The Western Schism, also known as the Papal Schism, the Vatican Standoff, the Great Occidental Schism, or the Schism of 1378 (), was a split within the Catholic Church lasting from 1378 to 1417 in which bishops residing in Rome and Avignon bo ...

(1378–1417). In this schism, the papacy had returned to Rome from Avignon, but an antipope was installed in Avignon, as if to extend the papacy there. It came to a close when the

Council of Constance

The Council of Constance was a 15th-century ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance in present-day Germany. The council ended the Western Schism by deposing or accepting the res ...

, at the high-point of Concilliarism, decided among the papal claimants.

The Eastern Church continued to decline with the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, undercutting Constantinople's claim to equality with Rome. Twice an Eastern Emperor tried to force the Eastern Church to reunify with the West. First in the

Second Council of Lyon

:''The First Council of Lyon, the Thirteenth Ecumenical Council, took place in 1245.''

The Second Council of Lyon was the fourteenth ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church, convoked on 31 March 1272 and convened in Lyon, Kingdom of Arl ...

(1272–1274) and secondly in the

Council of Florence

The Council of Florence is the seventeenth ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held between 1431 and 1449. It was convoked as the Council of Basel by Pope Martin V shortly before his death in February 1431 and took place in ...

(1431–1449). Papal claims of superiority were a sticking point in reunification, which failed in any event. In the 15th century, the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

captured

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

and ended the Byzantine Empire.

Reformation to present (1517 to today)

Protestant Reformers

Protestant Reformers were those theologians whose careers, works and actions brought about the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century.

In the context of the Reformation, Martin Luther was the first reformer (sharing his views publicly in 15 ...

criticized the papacy as corrupt and characterized the pope as the

antichrist

In Christian eschatology, the Antichrist refers to people prophesied by the Bible to oppose Jesus Christ and substitute themselves in Christ's place before the Second Coming. The term Antichrist (including one plural form) 1 John ; . 2 John . ...

.

Popes instituted a

Catholic Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

(1560–1648), which addressed the challenges of the Protestant Reformation and instituted internal reforms.

Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III ( la, Paulus III; it, Paolo III; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549), born Alessandro Farnese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death in November 1549.

He came to ...

initiated the

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trento, Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italian Peninsula, Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation ...

(1545–1563), whose definitions of doctrine and whose reforms sealed the triumph of the papacy over elements in the church that sought conciliation with Protestants and opposed papal claims.

Gradually forced to give up secular power to the increasingly assertive

European nation states, the popes focused on spiritual issues.

In 1870, the

First Vatican Council

The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the First Vatican Council or Vatican I was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, after a period of planning and preparation that began on 6 December 1864. This, the twentieth ecu ...

proclaimed the

dogma

Dogma is a belief or set of beliefs that is accepted by the members of a group without being questioned or doubted. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Islam ...

of

papal infallibility

Papal infallibility is a dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, in virtue of the promise of Jesus to Peter, the Pope when he speaks '' ex cathedra'' is preserved from the possibility of error on doctrine "initially given to the apos ...

for the most solemn occasions when the pope speaks when issuing a definition of faith or morals.

[Wetterau, Bruce. World history. New York: Henry Holt & co. 1994.] Later the same year,

Victor Emmanuel II of Italy

en, Victor Emmanuel Maria Albert Eugene Ferdinand Thomas

, house = Savoy

, father = Charles Albert of Sardinia

, mother = Maria Theresa of Austria

, religion = Roman Catholicism

, image_size = 252px

, succession1 ...

seized Rome from the pope's control and substantially completed the

unification of Italy

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century Political movement, political and social movement that resulted in the Merger (politics), consolidation of List of historic stat ...

.

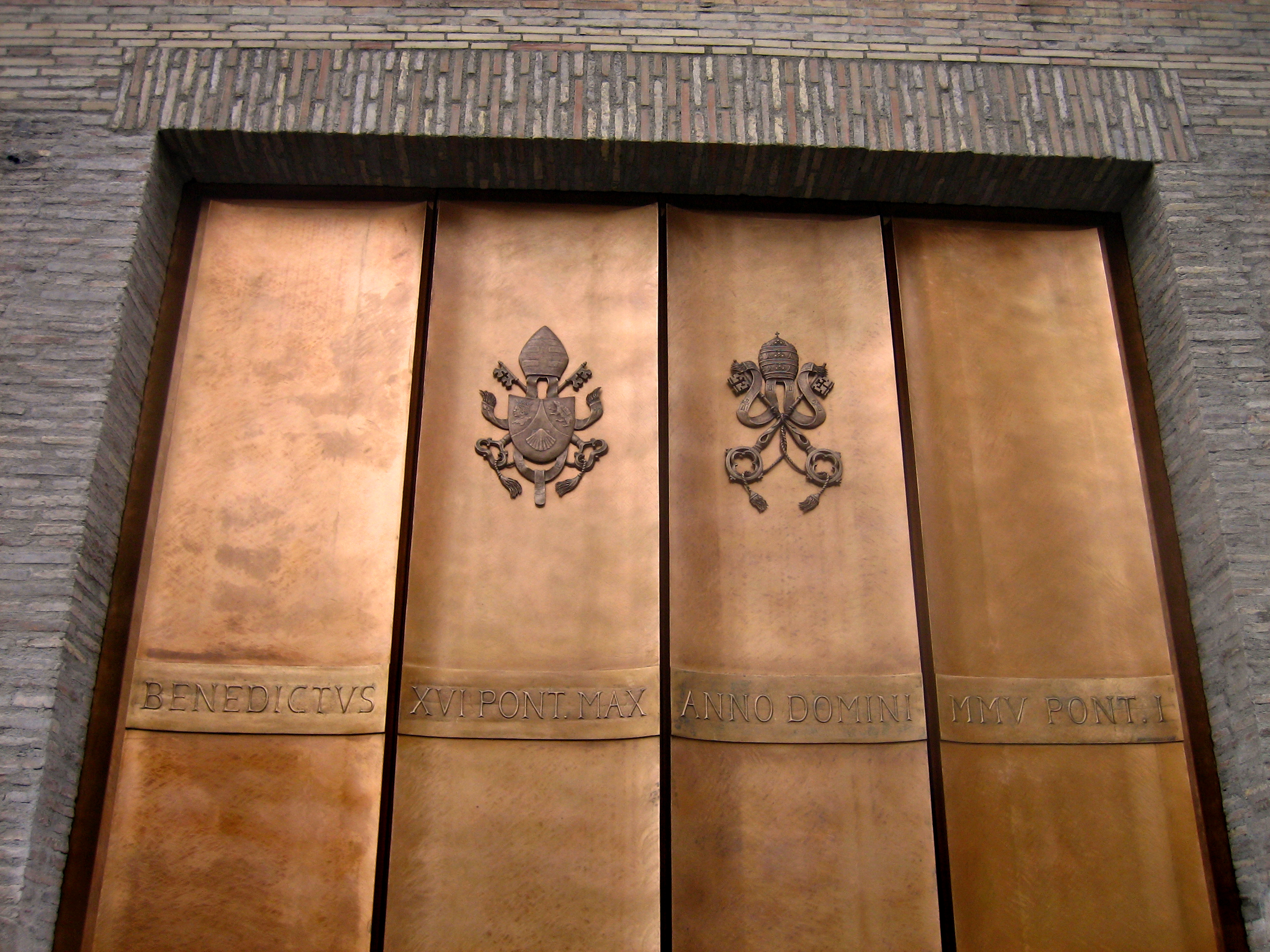

In 1929, the

Lateran Treaty

The Lateran Treaty ( it, Patti Lateranensi; la, Pacta Lateranensia) was one component of the Lateran Pacts of 1929, agreements between the Kingdom of Italy under King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy and the Holy See under Pope Pius XI to settle ...

between the

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

and the Holy See established

Vatican City

Vatican City (), officially the Vatican City State ( it, Stato della Città del Vaticano; la, Status Civitatis Vaticanae),—'

* german: Vatikanstadt, cf. '—' (in Austria: ')

* pl, Miasto Watykańskie, cf. '—'

* pt, Cidade do Vati ...

as an independent

city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

, guaranteeing papal independence from secular rule.

In 1950,

Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

defined the

Assumption of Mary

The Assumption of Mary is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Pope Pius XII defined it in 1950 in his apostolic constitution ''Munificentissimus Deus'' as follows:

We proclaim and define it to be a dogma revealed by Go ...

as dogma, the only time a pope has spoken since papal infallibility was explicitly declared.

The

Primacy of St. Peter, the controversial doctrinal basis of the pope's authority, continues to divide the eastern and western churches and to separate Protestants from Rome.

Saint Peter and the origin of the papal office

The

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

teaches that, within the Christian community, the bishops as a body have succeeded to the body of the apostles (''

apostolic succession

Apostolic succession is the method whereby the ministry of the Christian Church is held to be derived from the apostles by a continuous succession, which has usually been associated with a claim that the succession is through a series of bish ...

'') and the bishop of Rome has succeeded to Saint Peter.

Scriptural texts proposed in support of Peter's special position in relation to the church include:

*

Matthew 16:

*

Luke 22

Luke 22 is the twenty-second chapter of the Gospel of Luke in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It commences in the days just before the Passover or Feast of Unleavened Bread, and records the plot to kill Jesus Christ; the institution of t ...

:

*

John 21

John 21 is the twenty-first and final chapter of the Gospel of John in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It contains an account of a post-crucifixion appearance in Galilee, which the text describes as the third time Jesus had appeared ...

:

The symbolic keys in the

Papal coats of arms

Papal coats of arms are the personal coat of arms of popes of the Catholic Church. These have been a tradition since the Late Middle Ages, and has displayed his own, initially that of his family, and thus not unique to himself alone, but in some c ...

are a reference to the phrase "

the keys of the kingdom of heaven" in the first of these texts. Some Protestant writers have maintained that the "rock" that Jesus speaks of in this text is Jesus himself or the faith expressed by Peter. This idea is undermined by the Biblical usage of "Cephas", which is the masculine form of "rock" in

Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated in ...

, to describe Peter. The ''

Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various time ...

'' comments that "the consensus of the great majority of scholars today is that the most obvious and traditional understanding should be construed, namely, that rock refers to the person of Peter".

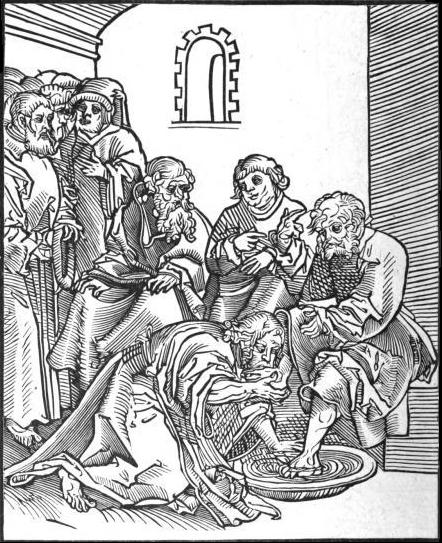

Election, death and resignation

Election

The pope was originally chosen by those senior clergymen resident in and near Rome. In 1059, the electorate was restricted to the cardinals of the Holy Roman Church, and the individual votes of all cardinal electors were made equal in 1179. The electors are now limited to those who have not reached 80 on the day before the death or resignation of a pope. The pope does not need to be a cardinal elector or indeed a cardinal; however, since the pope is the bishop of Rome, only those who can be ordained a bishop can be elected, which means that any male baptized Catholic is eligible. The last to be elected when not yet a bishop was

Gregory XVI

Pope Gregory XVI ( la, Gregorius XVI; it, Gregorio XVI; born Bartolomeo Alberto Cappellari; 18 September 1765 – 1 June 1846) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 February 1831 to his death in 1 June 1846. He h ...

in 1831, the last to be elected when not even a priest was

Leo X

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political an ...

in 1513, and the last to be elected when not a cardinal was

Urban VI

Pope Urban VI ( la, Urbanus VI; it, Urbano VI; c. 1318 – 15 October 1389), born Bartolomeo Prignano (), was head of the Catholic Church from 8 April 1378 to his death in October 1389. He was the most recent pope to be elected from outside the ...

in 1378. If someone who is not a bishop is elected, he must be given episcopal ordination before the election is announced to the people.

The Second Council of Lyon was convened on 7 May 1274, to regulate the election of the pope. This Council decreed that the cardinal electors must meet within ten days of the pope's death, and that they must remain in seclusion until a pope has been elected; this was prompted by the three-year ''

sede vacante

''Sede vacante'' ( in Latin.) is a term for the state of a diocese while without a bishop. In the canon law of the Catholic Church, the term is used to refer to the vacancy of the bishop's or Pope's authority upon his death or resignation.

Hi ...

'' following the death of

Clement IV

Pope Clement IV ( la, Clemens IV; 23 November 1190 – 29 November 1268), born Gui Foucois ( la, Guido Falcodius; french: Guy de Foulques or ') and also known as Guy le Gros ( French for "Guy the Fat"; it, Guido il Grosso), was bishop of Le P ...

in 1268. By the mid-16th century, the electoral process had evolved into its present form, allowing for variation in the time between the death of the pope and the meeting of the cardinal electors. Traditionally, the vote was conducted by

acclamation

An acclamation is a form of election that does not use a ballot. It derives from the ancient Roman word ''acclamatio'', a kind of ritual greeting and expression of approval towards imperial officials in certain social contexts.

Voting Voice vot ...

, by selection (by committee), or by plenary vote. Acclamation was the simplest procedure, consisting entirely of a voice vote.

The election of the pope almost always takes place in the

Sistine Chapel

The Sistine Chapel (; la, Sacellum Sixtinum; it, Cappella Sistina ) is a chapel in the Apostolic Palace, the official residence of the pope in Vatican City. Originally known as the ''Cappella Magna'' ('Great Chapel'), the chapel takes its name ...

, in a sequestered meeting called a "

conclave

A papal conclave is a gathering of the College of Cardinals convened to elect a bishop of Rome, also known as the pope. Catholics consider the pope to be the apostolic successor of Saint Peter and the earthly head of the Catholic Church.

Co ...

" (so called because the cardinal electors are theoretically locked in, ''cum clave'', i.e., with key, until they elect a new pope). Three cardinals are chosen by lot to collect the votes of absent cardinal electors (by reason of illness), three are chosen by lot to count the votes, and three are chosen by lot to review the count of the votes. The ballots are distributed and each cardinal elector writes the name of his choice on it and pledges aloud that he is voting for "one whom under God I think ought to be elected" before folding and depositing his vote on a plate atop a large chalice placed on the altar. For the

Papal conclave, 2005

The 2005 papal conclave was convened to elect a new pope following the death of Pope John Paul II on 2 April 2005. After his death, the cardinals of the Catholic Church who were in Rome met and set a date for the beginning of the conclave to elec ...

, a special urn was used for this purpose instead of a chalice and plate. The plate is then used to drop the ballot into the chalice, making it difficult for electors to insert multiple ballots. Before being read, the ballots are counted while still folded; if the number of ballots does not match the number of electors, the ballots are burned unopened and a new vote is held. Otherwise, each ballot is read aloud by the presiding Cardinal, who pierces the ballot with a needle and thread, stringing all the ballots together and tying the ends of the thread to ensure accuracy and honesty. Balloting continues until someone is elected by a two-thirds majority. (With the promulgation of ''

Universi Dominici Gregis'' in 1996, a simple majority after a deadlock of twelve days was allowed, but this was revoked by

Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI ( la, Benedictus XVI; it, Benedetto XVI; german: link=no, Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, , on 16 April 1927) is a retired prelate of the Catholic church who served as the head of the Church and the sovereign ...

by ''

motu proprio

In law, ''motu proprio'' (Latin for "on his own impulse") describes an official act taken without a formal request from another party. Some jurisdictions use the term ''sua sponte'' for the same concept.

In Catholic canon law, it refers to a do ...

'' in 2007.)

One of the most prominent aspects of the papal election process is the means by which the results of a ballot are announced to the world. Once the ballots are counted and bound together, they are burned in a special stove erected in the Sistine Chapel, with the smoke escaping through a small chimney visible from

Saint Peter's Square

Saint Peter's Square ( la, Forum Sancti Petri, it, Piazza San Pietro ,) is a large plaza located directly in front of St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, the papal enclave inside Rome, directly west of the neighborhood (rione) of Borgo. Bot ...

. The ballots from an unsuccessful vote are burned along with a chemical compound to create black smoke, or ''

fumata nera

A papal conclave is a gathering of the College of Cardinals convened to elect a bishop of Rome, also known as the pope. Catholics consider the pope to be the apostolic successor of Saint Peter and the earthly head of the Catholic Church.

C ...

''. (Traditionally, wet straw was used to produce the black smoke, but this was not completely reliable. The chemical compound is more reliable than the straw.) When a vote is successful, the ballots are burned alone, sending white smoke (''

fumata bianca'') through the chimney and announcing to the world the election of a new pope. Starting with the Papal conclave, 2005,

church bell

A church bell in Christian architecture is a bell which is rung in a church for a variety of religious purposes, and can be heard outside the building. Traditionally they are used to call worshippers to the church for a communal service, and t ...

s are also rung as a signal that a new pope has been chosen.

The

dean of the College of Cardinals

The dean of the College of Cardinals ( la, Decanus Collegii Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae Cardinalium) presides over the College of Cardinals in the Roman Catholic Church, serving as '' primus inter pares'' (first among equals). The position was establ ...

then asks two solemn questions of the man who has been elected. First he asks, "Do you freely accept your election as supreme pontiff?" If he replies with the word ''"Accepto"'', his reign begins at that instant. If he replies ''not'', his reign begins at the inauguration ceremony several days afterward. The dean asks next, "By what name shall you be called?" The new pope announces the

regnal name

A regnal name, or regnant name or reign name, is the name used by monarchs and popes during their reigns and, subsequently, historically. Since ancient times, some monarchs have chosen to use a different name from their original name when they ac ...

he has chosen. If the dean himself is elected pope, the vice dean performs this task.

The new pope is led to the

Room of Tears

The Room of Tears (Italian language, Italian: ''Sala de Lacrima''), also called The Crying Room, is a small antechamber within The Sistine Chapel in Vatican City, where a newly elected pope changes into his Cassock#Roman Catholic, papal cassock for ...

, a dressing room where three sets of white papal vestments (''immantatio'') await in three sizes. Donning the appropriate vestments and reemerging into the Sistine Chapel, the new pope is given the "

Fisherman's Ring

The Ring of the Fisherman (Latin: ''Anulus piscatoris''; Italian: ''Anello Piscatorio''), also known as the Piscatory Ring, is an official part of the regalia worn by the Pope, who is head of the Catholic Church and successor of Saint Peter, who wa ...

" by the

camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church

The Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church is an office of the papal household that administers the property and revenues of the Holy See. Formerly, his responsibilities included the fiscal administration of the Patrimony of Saint Peter. As regul ...

. The pope assumes a place of honor as the rest of the cardinals wait in turn to offer their first "obedience" (''adoratio'') and to receive his blessing.

The

cardinal protodeacon announces from a balcony over

St. Peter's Square

Saint Peter's Square ( la, Forum Sancti Petri, it, Piazza San Pietro ,) is a large plaza located directly in front of St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, the pope, papal enclave and exclave, enclave inside Rome, directly west of the neighbor ...

the following proclamation: ''Annuntio vobis gaudium magnum!

Habemus Papam!'' ("I announce to you a great joy! We have a pope!"). He announces the new pope's

Christian name

A Christian name, sometimes referred to as a baptismal name, is a religious personal name given on the occasion of a Christian baptism, though now most often assigned by parents at birth. In English-speaking cultures, a person's Christian name ...

along with his newly chosen regnal name.

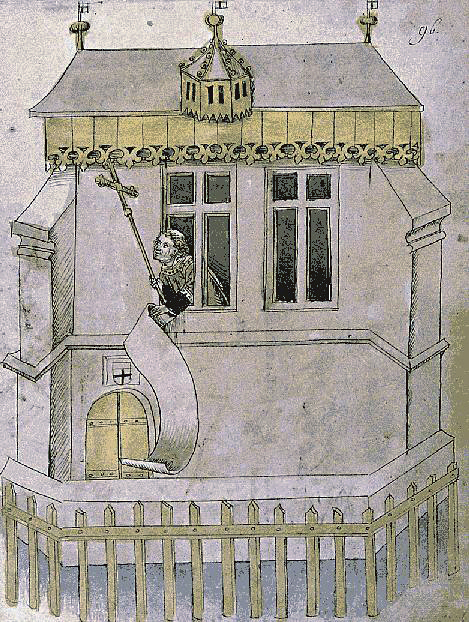

Until 1978, the pope's election was followed in a few days by the

papal coronation

A papal coronation is the formal ceremony of the placing of the papal tiara on a newly elected pope. The first recorded papal coronation was of Pope Nicholas I in 858. The most recent was the 1963 coronation of Paul VI, who soon afterwards aband ...

, which started with a procession with great pomp and circumstance from the Sistine Chapel to

St. Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a church built in the Renaissance style located in Vatican City, the papal e ...

, with the newly elected pope borne in the ''

sedia gestatoria

The ''sedia gestatoria'' (, literally 'chair for carrying') or gestatorial chair is a ceremonial throne on which popes were carried on shoulders until 1978, which was later replaced outdoors in part with the popemobile. It consists of a richly a ...

''. After a solemn

Papal Mass

A Papal Mass is the Solemn Pontifical High Mass celebrated by the Pope. It is celebrated on such occasions as a papal coronation, an ''ex cathedra'' pronouncement, the canonization of a saint, on Easter or Christmas or other major feast days.

U ...

, the new pope was crowned with the ''

triregnum

The papal tiara is a crown (headgear), crown that was worn by popes of the Catholic Church from as early as the 8th century to the mid-20th. It was last used by Pope Paul VI in 1963 and only at the beginning of his reign.

The name "tiara" refe ...

'' (papal tiara) and he gave for the first time as pope the famous blessing ''

Urbi et Orbi

''Urbi et Orbi'' ('to the city f Romeand to the world') denotes a papal address and apostolic blessing given by the pope on certain solemn occasions.

Etymology

The term ''Urbi et Orbi'' evolved from the consciousness of the ancient Roman Empir ...

'' ("to the City

ome

Ome may refer to:

Places

* Ome (Bora Bora), a public island in the lagoon of Bora Bora

* Ome, Lombardy, Italy, a town and ''comune'' in the Province of Brescia

* Ōme, Tokyo, a city in the Prefecture of Tokyo

* Ome (crater), a crater on Mars

Tran ...

and to the World"). Another renowned part of the coronation was the lighting of a bundle of

flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. Textiles made from flax are known in ...

at the top of a gilded pole, which would flare brightly for a moment and then promptly extinguish, as he said, ''

Sic transit gloria mundi

''Sic transit gloria mundi'' is a Latin phrase that means "Thus passes the glory of the world."

Origin

The phrase was used in the ritual of papal coronation ceremonies between 1409 (when it was used at the coronation of Alexander V) and 1963. A ...

'' ("Thus passes worldly glory"). A similar warning against papal

hubris

Hubris (; ), or less frequently hybris (), describes a personality quality of extreme or excessive pride or dangerous overconfidence, often in combination with (or synonymous with) arrogance. The term ''arrogance'' comes from the Latin ', mean ...

made on this occasion was the traditional exclamation, ''"Annos Petri non-videbis"'', reminding the newly crowned pope that he would not live to see his rule lasting as long as that of St. Peter. According to tradition, he headed the church for 35 years and has thus far been the longest-reigning pope in the history of the Catholic Church.

The

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

term, ''sede vacante'' ("while the see is vacant"), refers to a papal

interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

, the period between the death or resignation of a pope and the election of his successor. From this term is derived the term

sedevacantism

Sedevacantism ( la, Sedevacantismus) is a doctrinal position within traditionalist Catholicism, which holds that the present occupier of the Holy See is not a valid pope due to the pope's espousal of one or more heresies and that therefore, for ...

, which designates a category of dissident Catholics who maintain that there is no canonically and legitimately elected pope, and that there is therefore a ''sede vacante''. One of the most common reasons for holding this belief is the idea that the reforms of the

Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions) ...

, and especially the reform of the

Tridentine Mass

The Tridentine Mass, also known as the Traditional Latin Mass or Traditional Rite, is the liturgy of Mass in the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church that appears in typical editions of the Roman Missal published from 1570 to 1962. Celebrated almo ...

with the

Mass of Paul VI

The Mass of Paul VI, also known as the Ordinary Form or Novus Ordo, is the most commonly used liturgy in the Catholic Church. It is a form of the Latin Church's Roman Rite and was promulgated by Pope Paul VI in 1969, published by him in the 1970 ...

, are heretical and that those responsible for initiating and maintaining these changes are heretics and not true popes.

For centuries, from 1378 on, those elected to the papacy were predominantly Italians. Prior to the election of the Polish-born John Paul II in 1978, the last non-Italian was

Adrian VI

Pope Adrian VI ( la, Hadrianus VI; it, Adriano VI; nl, Adrianus/Adriaan VI), born Adriaan Florensz Boeyens (2 March 1459 – 14 September 1523), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 January 1522 until his d ...

of the Netherlands, elected in 1522. John Paul II was followed by election of the German-born

Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI ( la, Benedictus XVI; it, Benedetto XVI; german: link=no, Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, , on 16 April 1927) is a retired prelate of the Catholic church who served as the head of the Church and the sovereign ...

, who was in turn followed by Argentine-born

Francis, the first non-European after 1272 years and the first Latin American (albeit of Italian ancestry).

Death

The current regulations regarding a papal interregnum—that is, a ''sede vacante'' ("vacant seat")—were promulgated by

Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

in his 1996 document ''Universi Dominici Gregis''. During the "sede vacante" period, the

College of Cardinals

The College of Cardinals, or more formally the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. its current membership is , of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Cardinals are appoi ...

is collectively responsible for the government of the Church and of the Vatican itself, under the direction of the Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church; however, canon law specifically forbids the cardinals from introducing any innovation in the government of the Church during the vacancy of the Holy See. Any decision that requires the assent of the pope has to wait until the new pope has been elected and accepts office.

In recent centuries, when a pope was judged to have died, it was reportedly traditional for the cardinal camerlengo to confirm the death ceremonially by gently tapping the pope's head thrice with a silver hammer, calling his birth name each time. This was not done on the deaths of popes

John Paul I

Pope John Paul I ( la, Ioannes Paulus I}; it, Giovanni Paolo I; born Albino Luciani ; 17 October 1912 – 28 September 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City from 26 August 1978 to his death 33 days later. Hi ...

and John Paul II. The cardinal camerlengo retrieves the

Ring of the Fisherman

The Ring of the Fisherman (Latin: ''Anulus piscatoris''; Italian: ''Anello Piscatorio''), also known as the Piscatory Ring, is an official part of the regalia worn by the Pope, who is head of the Catholic Church and successor of Saint Peter, who wa ...

and cuts it in two in the presence of the cardinals. The pope's seals are defaced, to keep them from ever being used again, and his

personal apartment is sealed.

The body

lies in state for several days before being interred in the

crypt

A crypt (from Latin ''crypta'' "vault") is a stone chamber beneath the floor of a church or other building. It typically contains coffins, sarcophagi, or religious relics.

Originally, crypts were typically found below the main apse of a chur ...

of a leading church or cathedral; all popes who have died in the 20th and 21st centuries have been interred in St. Peter's Basilica. A nine-day period of

mourning

Mourning is the expression of an experience that is the consequence of an event in life involving loss, causing grief, occurring as a result of someone's death, specifically someone who was loved although loss from death is not exclusively ...

(''novendialis'') follows the interment.

Resignation

It is highly unusual for a pope to resign. The

1983 Code of Canon Law

The 1983 ''Code of Canon Law'' (abbreviated 1983 CIC from its Latin title ''Codex Iuris Canonici''), also called the Johanno-Pauline Code, is the "fundamental body of ecclesiastical laws for the Latin Church". It is the second and current comp ...