The Mandate for Palestine was a

League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

for British administration of the territories of

Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

and

Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

, both of which had been conceded by the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

following the end of

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1918. The mandate was assigned to Britain by the

San Remo conference

The San Remo conference was an international meeting of the post-World War I Allied Supreme Council as an outgrowth of the Paris Peace Conference, held at Villa Devachan in Sanremo, Italy, from 19 to 26 April 1920. The San Remo Resolution pas ...

in April 1920, after France's concession in the

1918 Clemenceau–Lloyd George Agreement of the previously-agreed "international administration" of Palestine under the

Sykes–Picot Agreement

The Sykes–Picot Agreement () was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Italy, to define their mutually agreed Sphere of influence, spheres of influence and control in a ...

. Transjordan was added to the mandate after

the Arab Kingdom in Damascus was toppled by the French in the

Franco-Syrian War

The Franco-Syrian War took place during 1920 between the Hashemite rulers of the newly established Arab Kingdom of Syria and France. During a series of engagements, which climaxed in the Battle of Maysalun, French forces defeated the forces of th ...

. Civil administration began in Palestine and Transjordan in July 1920 and April 1921, respectively, and the mandate was in force from 29 September 1923 to 15 May 1948 and to 25 May 1946 respectively.

The mandate document was based on Article 22 of the

Covenant of the League of Nations

The Covenant of the League of Nations was the charter of the League of Nations. It was signed on 28 June 1919 as Part I of the Treaty of Versailles, and became effective together with the rest of the Treaty on 10 January 1920.

Creation

Early d ...

of 28 June 1919 and the

Supreme Council of the Principal Allied Powers' San Remo Resolution of 25 April 1920. The objective of the mandates over former territories of Ottoman Empire was to provide "administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory until such time as they are able to stand alone". The border between Palestine and Transjordan was agreed in the final mandate document, and the approximate northern border with the French

Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (french: Mandat pour la Syrie et le Liban; ar, الانتداب الفرنسي على سوريا ولبنان, al-intidāb al-fransi 'ala suriya wa-lubnān) (1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate foun ...

was agreed in the

Paulet–Newcombe Agreement

The Paulet–Newcombe Agreement or Paulet-Newcombe Line, was a 1923 agreement between the British and French governments regarding the position and nature of the boundary between the Mandates of Palestine and Iraq, attributed to Great Britain, a ...

of 23 December 1920.

In Palestine, the

Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

's "national home for the Jewish people" was to be established alongside the

Palestinian Arabs

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

, who composed the

vast majority of the local population; this requirement and others, however, would not apply to the separate Arab emirate to be established in Transjordan. The British controlled Palestine for almost three decades, overseeing a succession of protests, riots and revolts between the Jewish and Palestinian Arab communities. During the Mandate, the area saw the rise of two nationalist movements: the Jews and the Palestinian Arabs.

Intercommunal conflict in Mandatory Palestine

The intercommunal conflict in Mandatory Palestine was the civil, political and armed struggle between Palestinian Arabs and Jewish Yishuv during the British rule in Mandatory Palestine, beginning from the violent spillover of the Franco-Syrian ...

ultimately produced the

1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

The 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, later known as The Great Revolt (''al-Thawra al- Kubra'') or The Great Palestinian Revolt (''Thawrat Filastin al-Kubra''), was a popular nationalist uprising by Palestinian Arabs in Mandatory Palestine a ...

and the 1944–1948

Jewish insurgency in Mandatory Palestine

A successful paramilitary campaign was carried out by Zionist underground groups against British rule in Mandatory Palestine from 1944 to 1948. The tensions between the Zionist underground and the British mandatory authorities rose from 1938 a ...

. The

United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as Re ...

was passed on 29 November 1947; this envisaged the creation of separate Jewish and Arab states operating under economic union, and with Jerusalem transferred to UN trusteeship. Two weeks later, Colonial Secretary

Arthur Creech Jones

Arthur Creech Jones (15 May 1891 – 23 October 1964) was a British trade union official and politician. Originally a civil servant, his imprisonment as a conscientious objector during the First World War forced him to change careers. He was el ...

announced that the British Mandate would end on 15 May 1948. On the last day of the Mandate, the Jewish community there issued the

Israeli Declaration of Independence

The Israeli Declaration of Independence, formally the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel ( he, הכרזה על הקמת מדינת ישראל), was proclaimed on 14 May 1948 ( 5 Iyar 5708) by David Ben-Gurion, the Executive ...

. After the failure of the

United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as Re ...

, the

1947–1949 Palestine war

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. It is known in Israel as the War of Independence ( he, מלחמת העצמאות, ''Milkhemet Ha'Atzma'ut'') and ...

ended with Mandatory Palestine divided among

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, the

Jordanian annexation of the West Bank

The Jordanian annexation of the West Bank formally occurred on 24 April 1950, after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, during which Transjordan occupied territory that had previously been part of Mandatory PalestineRaphael Israeli, Jerusalem div ...

and the Egyptian

All-Palestine Protectorate

The All-Palestine Protectorate, or simply All-Palestine, also known as Gaza Protectorate and Gaza Strip, was a short-lived client state with limited recognition, corresponding to the area of the modern Gaza Strip, that was established in the area ...

in the

Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (;The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p.761 "Gaza Strip /'gɑːzə/ a strip of territory under the control of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas, on the SE Mediterranean coast including the town of Gaza.. ...

.

Transjordan was added to the mandate following the

Cairo Conference

The Cairo Conference (codenamed Sextant) also known as the First Cairo Conference, was one of the 14 summit meetings during World War II that occurred on November 22–26, 1943. The Conference was held in Cairo, Egypt, between the United Kingdo ...

of March 1921, at which it was agreed that

Abdullah bin Hussein

Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein ( ar, عبدالله الثاني بن الحسين , translit=ʿAbd Allāh aṯ-ṯānī ibn al-Ḥusayn; born 30 January 1962) is King of Jordan, having ascended the throne on 7 February 1999. He is a member of t ...

would administer the territory under the auspices of the Palestine Mandate. Since the end of the war it had been

administered from Damascus by a joint Arab-British military administration headed by Abdullah's younger brother Faisal, and then

became a no man's land after the French defeated Faisal's army in July 1920 and the British initially chose to avoid a definite connection with Palestine. The addition of Transjordan was given legal form on 21 March 1921, when the British incorporated Article 25 into the Palestine Mandate. Article 25 was implemented via the 16 September 1922

Transjordan memorandum

The Transjordan memorandum was a British memorandum passed by the Council of the League of Nations on 16 September 1922, as an addendum to the British Mandate for Palestine.

The memorandum described how the British government planned to implemen ...

, which established a separate "Administration of Trans-Jordan" for the application of the Mandate under the general supervision of Great Britain. In April 1923, five months before the mandate came into force, Britain announced its intention to recognise an "independent Government" in Transjordan; this autonomy increased further under a 20 February 1928 treaty, and the state became fully independent with the

Treaty of London of 22 March 1946.

Background

Commitment regarding the Jewish people: the Balfour Declaration

Immediately following their declaration of war on the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in November 1914, the

British War Cabinet

A war cabinet is a committee formed by a government in a time of war to efficiently and effectively conduct that war. It is usually a subset of the full executive cabinet of ministers, although it is quite common for a war cabinet to have senior ...

began to consider the future of

Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

(at the time, an Ottoman region with a

small minority Jewish population). By late 1917, in the lead-up to the

Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

, the

wider war had reached a stalemate. Two of Britain's allies were not fully engaged, the United States had yet to suffer a casualty, and the Russians were in the midst of the

October revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

. A

stalemate in southern Palestine

The Stalemate in Southern Palestine was a six month standoff between the British Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) and the Ottoman Army in World War I. The two hostile forces faced each other along the Gaza to Beersheba line during the Sinai and ...

was broken by the

Battle of Beersheba on 31 October 1917. The release of the Balfour Declaration was authorised by 31 October; the preceding Cabinet discussion had mentioned perceived propaganda benefits amongst the worldwide

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

community for the Allied war effort.

The British government issued the Declaration, a public statement announcing support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, on 2 November 1917. The opening words of the declaration represented the first public expression of support for Zionism by a major political power. The term "national home" had no precedent in international law, and was intentionally vague about whether a

Jewish state

In world politics, Jewish state is a characterization of Israel as the nation-state and sovereign homeland of the Jewish people.

Modern Israel came into existence on 14 May 1948 as a polity to serve as the homeland for the Jewish people. It ...

was contemplated. The intended boundaries of Palestine were not specified, and the British government later confirmed that the words "in Palestine" meant that the Jewish national home was not intended to cover all of Palestine. The second half of the declaration was added to satisfy opponents of the policy, who said that it would otherwise prejudice the position of the local population of Palestine and encourage

antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

worldwide by (according to the presidents of the Conjoint Committee,

David L. Alexander and

Claude Montefiore

Claude Joseph Goldsmid Montefiore, also Goldsmid–Montefiore or just Goldsmid Montefiore (1858–1938) was the intellectual founder of Anglo- Liberal Judaism and the founding president of the World Union for Progressive Judaism, a schola ...

in a letter to the ''Times'') "stamping the Jews as strangers in their native lands". The declaration called for safeguarding the civil and religious rights for the

Palestinian Arabs

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

, who composed the vast majority of the local population, and the rights of Jewish communities in any other country.

The Balfour Declaration was subsequently incorporated into the Mandate for Palestine to put the declaration into effect. Unlike the declaration itself, the Mandate was legally binding on the British government.

Commitment regarding the Arab population: the McMahon–Hussein correspondence

Between July 1915 and March 1916, a series of ten letters were exchanged between

Sharif Hussein bin Ali

Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi ( ar, الحسين بن علي الهاشمي, al-Ḥusayn bin ‘Alī al-Hāshimī; 1 May 18544 June 1931) was an Arab leader from the Banu Hashim clan who was the Sharif and Emir of Mecca from 1908 and, after procla ...

, the head of the

Hashemite family

The Hashemites ( ar, الهاشميون, al-Hāshimīyūn), also House of Hashim, are the Dynasty, royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Kingdom of Hejaz, Hejaz (1916–1925), Ar ...

that had ruled the

Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Provin ...

as vassals for almost a millennium, and

Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

Sir Henry McMahon

Sir Arthur Henry McMahon (28 November 1862 – 29 December 1949) was a British Indian Army officer and diplomat who served as the High Commissioner in Egypt from 1915 to 1917. He was also an administrator in British India and served twice as ...

,

British High Commissioner to Egypt. In the letters – particularly that of 24 October 1915 – the British government agreed to recognise Arab independence after the war

in exchange for the

Sharif of Mecca

The Sharif of Mecca ( ar, شريف مكة, Sharīf Makkah) or Hejaz ( ar, شريف الحجاز, Sharīf al-Ḥijāz, links=no) was the title of the leader of the Sharifate of Mecca, traditional steward of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina and ...

launching the

Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On t ...

against the Ottoman Empire. Whilst there was some military value in the Arab manpower and local knowledge alongside the British Army, the primary reason for the arrangement was to counteract the

Ottoman declaration of ''jihad'' ("holy war") against the Allies, and to maintain the support of the

70 million Muslims in British India (particularly those in the

Indian Army that had been deployed in all major theatres of the wider war).

The area of Arab independence was defined as "in the limits and boundaries proposed by the

Sherif of Mecca", with the exclusion of a coastal area lying to the west of "the districts of

Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

,

Homs

Homs ( , , , ; ar, حِمْص / ALA-LC: ; Levantine Arabic: / ''Ḥomṣ'' ), known in pre-Islamic Syria as Emesa ( ; grc, Ἔμεσα, Émesa), is a city in western Syria and the capital of the Homs Governorate. It is Metres above sea level ...

,

Hama

, timezone = EET

, utc_offset = +2

, timezone_DST = EEST

, utc_offset_DST = +3

, postal_code_type =

, postal_code =

, ar ...

and

Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

"; conflicting interpretations of this description caused great controversy in subsequent years. A particular dispute, which continues to the present, was whether Palestine was part of the coastal exclusion. At the

Paris Peace Conference in 1919, British Prime Minister

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

told his French counterpart

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was a ...

and the other allies that the McMahon-Hussein correspondence was a treaty obligation.

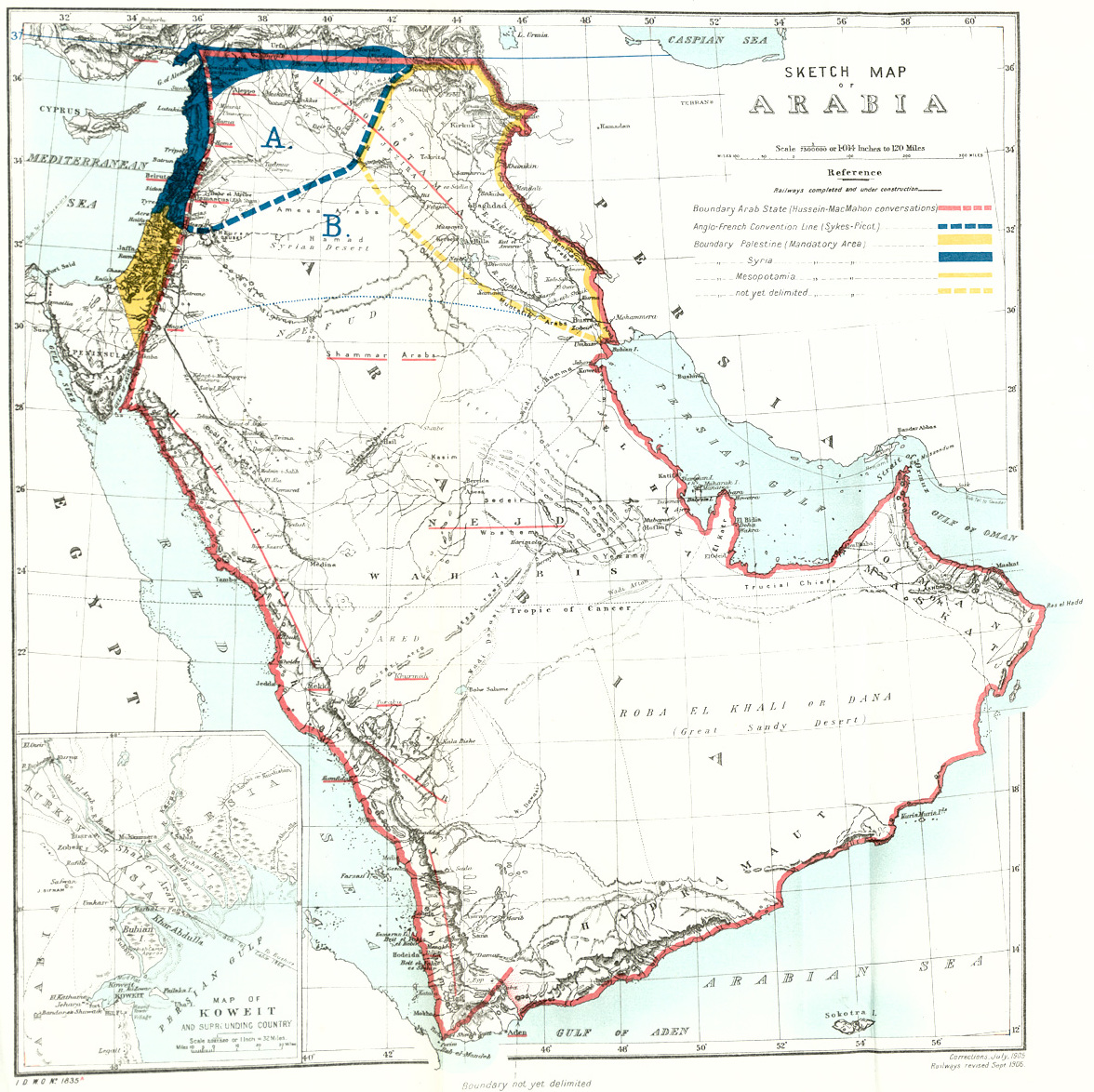

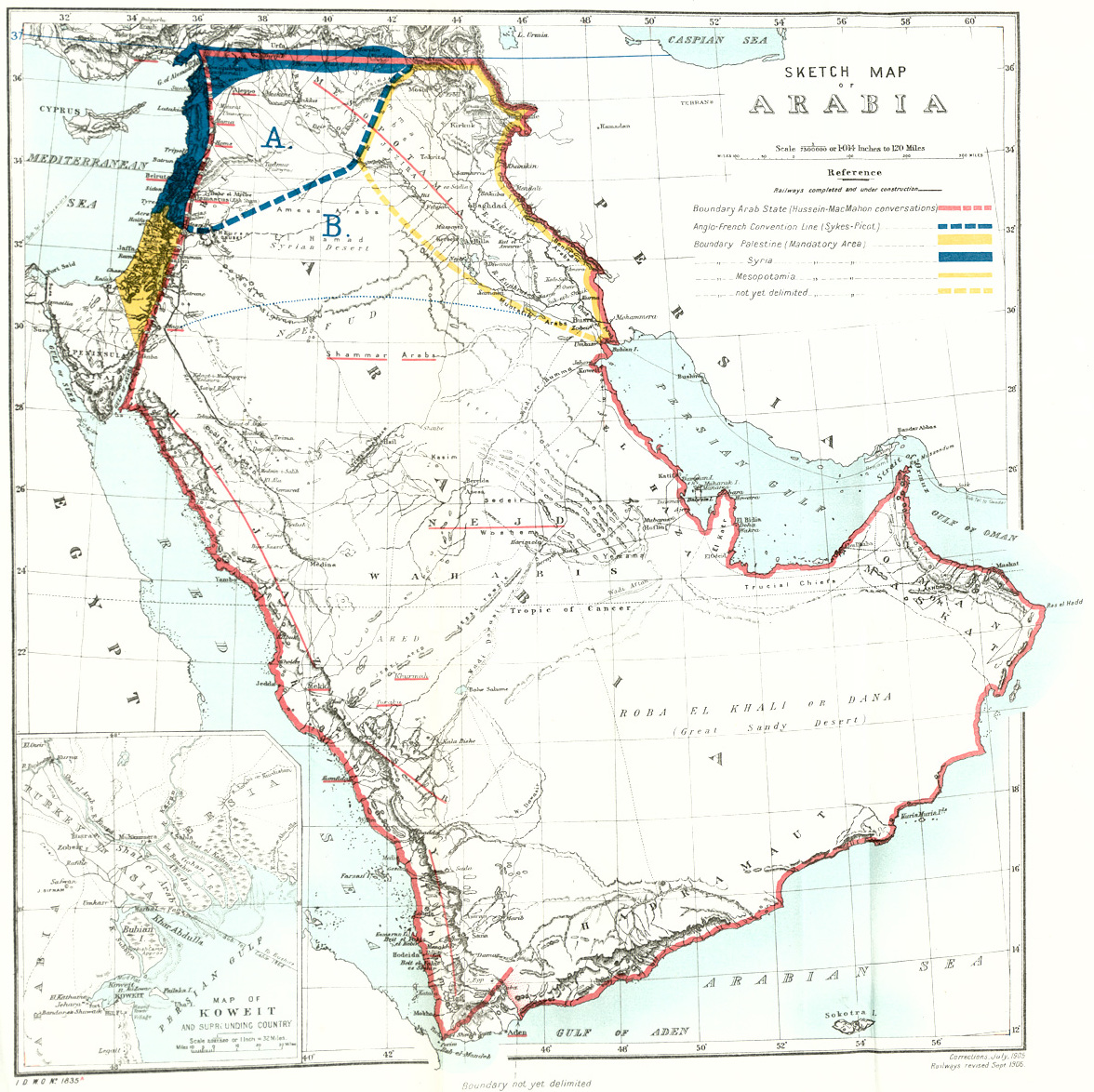

Commitment to the French: the Sykes–Picot agreement

Around the same time, another

secret treaty

A secret treaty is a treaty (international agreement) in which the contracting state parties have agreed to conceal the treaty's existence or substance from other states and the public.Helmut Tichy and Philip Bittner, "Article 80" in Olivier D� ...

was

negotiated between the United Kingdom and France (with assent by the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

and Italy) to define their mutually-agreed

spheres of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

and control in an eventual

partition of the Ottoman Empire

The partition of the Ottoman Empire (30 October 19181 November 1922) was a geopolitical event that occurred after World War I and the occupation of Constantinople by British, French and Italian troops in November 1918. The partitioning was ...

. The primary negotiations leading to the agreement occurred between 23 November 1915 and 3 January 1916; on 3 January the British and French diplomats

Mark Sykes

Colonel Sir Tatton Benvenuto Mark Sykes, 6th Baronet (16 March 1879 – 16 February 1919) was an English traveller, Conservative Party politician, and diplomatic advisor, particularly with regard to the Middle East at the time of the First Wo ...

and

François Georges-Picot

François Marie Denis Georges-Picot (21 December 1870 – 20 June 1951) was a French diplomat and lawyer who negotiated the Sykes–Picot Agreement with the British diplomat Sir Mark Sykes between November 1915 and March 1916 before its signing ...

initialled an agreed memorandum. The agreement was ratified by their respective governments on 9 and 16 May 1916. The agreement allocated to Britain control of present-day southern

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

and

Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

,

Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

and southern

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, and an additional small area including the ports of

Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

and

Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

to allow access to the Mediterranean. The Palestine region, with smaller boundaries than the later

Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

, was to fall under an "international administration". The agreement was initially used as the basis for the

, which provided a framework for the

Occupied Enemy Territory Administration

The Occupied Enemy Territory Administration (OETA) was a joint British, French and Arab military administration over Levantine provinces of the former Ottoman Empire between 1917 and 1920, set up on 23 October 1917 following the Sinai and Pale ...

(OETA) in the Levant.

Commitment to the League of Nations: the mandate system

The mandate system was created in the wake of World War I as a compromise between

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's ideal of

self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

, set out in his

Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

speech of January 1918, and the European powers' desire for

gains for their empires. It was established under Article 22 of the

Covenant of the League of Nations

The Covenant of the League of Nations was the charter of the League of Nations. It was signed on 28 June 1919 as Part I of the Treaty of Versailles, and became effective together with the rest of the Treaty on 10 January 1920.

Creation

Early d ...

, entered into on 28 June 1919 as Part I of the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, and came into force on 10 January 1920 with the rest of the treaty. Article 22 was written two months before the signing of the peace treaty, before it was agreed exactly which communities, peoples, or territories would be covered by the three types of mandate set out in sub-paragraphs 4, 5, and 6 – Class A "formerly belonging to the Turkish Empire", Class B "of Central Africa" and Class C "South-West Africa and certain of the South Pacific Islands". The treaty was signed and the peace conference adjourned before a formal decision was made.

Two governing principles formed the core of the mandate system: non-annexation of the territory and its administration as a "sacred trust of civilisation" to develop the territory for the benefit of its native people. The mandate system differed fundamentally from the

protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

system which preceded it, in that the mandatory power's obligations to the inhabitants of the territory were supervised by a third party: the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. The mandates were to act as legal instruments containing the internationally agreed-upon terms for administering certain post-World War I territories on behalf of the League of Nations. These were of the nature of a treaty and a constitution, which contained

minority-rights clauses that provided for the rights of petition and adjudication by the

World Court

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

.

The process of establishing the mandates consisted of two phases: the formal removal of

sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

of the state previously controlling the territory, followed by the transfer of mandatory powers to individual states among the

Allied powers. According to the Council of the League of Nations meeting of August 1920, "draft mandates adopted by the Allied and Associated Powers would not be definitive until they had been considered and approved by the League ... the legal title held by the mandatory Power must be a double one: one conferred by the Principal Powers and the other conferred by the League of Nations." Three steps were required to establish a mandate: "(1) The Principal Allied and Associated Powers confer a mandate on one of their number or on a third power; (2) the principal powers officially notify the council of the League of Nations that a certain power has been appointed mandatory for such a certain defined territory; and (3) the council of the League of Nations takes official cognisance of the appointment of the mandatory power and informs the latter that it

he council

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

considers it as invested with the mandate, and at the same time notifies it of the terms of the mandate, after ascertaining whether they are in conformance with the provisions of the covenant."

Assignment to Britain

Palestine

Discussions about the assignment of the region's control began immediately after the war ended and continued at the

Paris Peace Conference and the February 1920

Conference of London

List of conferences in London (chronological):

* London Conference of 1830 guaranteed the independence of Belgium

* London Conference of 1832 convened to establish a stable government in Greece

* London Conference of 1838–1839 preceded the Tr ...

, and the assignment was made at the April 1920 San Remo conference. The Allied Supreme Council granted the mandates for Palestine

and Mesopotamia to Britain, and those for

Syria and Lebanon to France.

In anticipation of the Peace Conference, the British devised a "

Sharifian Solution

The Sharifian or Sherifian Solution, () as first put forward by T. E. Lawrence in 1918, was a plan to install three of Sharif Hussein's four sons as heads of state in newly created countries across the Middle East: his second son Abdullah ruling ...

" to "

ake

Ake (or Aké in Spanish orthography) is an archaeological site of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization. It's located in the municipality of Tixkokob, in the Mexican state of Yucatán; 40 km (25 mi) east of Mérida, Yucatán.

The name ...

straight all the tangle" of their various wartime commitments. This proposed that three sons of Sharif Hussein – who had since become

King of the Hejaz

The Hashemite Kingdom of Hejaz ( ar, المملكة الحجازية الهاشمية, ''Al-Mamlakah al-Ḥijāziyyah Al-Hāshimiyyah'') was a state in the Hejaz region in the Middle East that included the western portion of the Arabian Penins ...

, and his sons

emirs

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cerem ...

(princes) – would be installed as kings of newly created countries across the region agreed between McMahon and Hussein in 1915. The Hashemite delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, led by Hussein's third son

Emir Faisal

Faisal I bin Al-Hussein bin Ali Al-Hashemi ( ar, فيصل الأول بن الحسين بن علي الهاشمي, ''Faysal el-Evvel bin al-Ḥusayn bin Alī el-Hâşimî''; 20 May 1885 – 8 September 1933) was King of the Arab Kingdom of Syria ...

, had been invited by the British to represent the Arabs at the conference; they had wanted Palestine to be part of the proposed Arab state, and later modified this request to an Arab state under a British mandate. The delegation made two initial

statements to the peace conference. The 1 January 1919 memorandum referred to the goal of "unit

ngthe Arabs eventually into one nation", defining the Arab regions as "from a line

Alexandretta –

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

southward to the Indian Ocean". The 29 January memorandum stipulated that "from the line Alexandretta –

Diarbekr southward to the Indian Ocean" (with the boundaries of any new states) were "matters for arrangement between us, after the wishes of their respective inhabitants have been ascertained", in a reference to

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's policy of

self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

. In his 6 February 1919 presentation to the Paris Peace Conference, Faisal (speaking on behalf of King Hussein) asked for Arab independence or at least the right to choose the mandatory. The Hashemites had fought with the British during the war, and received an annual subsidy from Britain; according to the confidential appendix to the August 1919

King-Crane Commission report, "the French resent the payment by the English to the Emir Faisal of a large monthly subsidy, which they claim covers a multitude of bribes, and enables the British to stand off and show clean hands while Arab agents do dirty work in their interest."

The World Zionist Organization delegation to the Peace Conference – led by

Chaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( he, חיים עזריאל ויצמן ', russian: Хаим Евзорович Вейцман, ''Khaim Evzorovich Veytsman''; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born biochemist, Zionist leader and Israel ...

, who had been the driving force behind the Balfour Declaration – also asked for a British mandate, asserting the "historic title of the Jewish people to Palestine". The confidential appendix to the King-Crane Commission report noted that "The Jews are distinctly for Britain as mandatory power, because of the Balfour declaration."

[ The Zionists met with Faisal two weeks before the start of the conference in order to resolve their differences; the resulting ]Faisal–Weizmann Agreement

The Faisal–Weizmann Agreement was a 3 January 1919 agreement between Faisal I of Iraq, Emir Faisal, the third son of Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, Hussein ibn Ali al-Hashimi, King of the short-lived Kingdom of Hejaz, and Chaim Weizmann, a ...

was signed on 3 January 1919. Together with letter written by T. E. Lawrence in Faisal's name to Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judicia ...

in March 1919, the agreement was used by the Zionist delegation to argue that their plans for Palestine had prior Arab approval; however, the Zionists omitted Faisal's handwritten caveat that the agreement was conditional on Palestine being within the area of Arab independence.

The French privately ceded Palestine and Mosul to the British in a December 1918 amendment to the Sykes–Picot Agreement; the amendment was finalised at a meeting in Deauville

Deauville () is a commune in the Calvados department, Normandy, northwestern France. Major attractions include its harbour, race course, marinas, conference centre, villas, Grand Casino, and sumptuous hotels. The first Deauville Asian Film Fes ...

in September 1919. Matters were confirmed at the San Remo conference, which formally assigned the mandate for Palestine to the United Kingdom under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations. Although France required the continuation of its religious protectorate in Palestine, Italy and Great Britain opposed it. France lost the religious protectorate but, thanks to the Holy See, continued to enjoy liturgical honors in Mandatory Palestine until 1924 (when the honours were abolished). As Weizmann reported to his WZO colleagues in London in May 1920, the boundaries of the mandated territories were unspecified at San Remo and would "be determined by the Principal Allied Powers" at a later stage.

Addition of Transjordan

Under the terms of the 1915 McMahon-Hussein Correspondence and the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement, Transjordan was intended to become part of an Arab state or a confederation of Arab states. British forces retreated in spring 1918 from Transjordan after their first

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

and second

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ...

attacks on the territory, indicating their political ideas about its future; they had intended the area to become part of an Arab Syrian state. The British subsequently defeated the Ottoman forces in Transjordan in late September 1918, just a few weeks before the Ottoman Empire's overall surrender.

Transjordan was not mentioned during the 1920 discussions at San Remo, at which the Mandate for Palestine was awarded. Britain and France agreed that the eastern border of Palestine would be the Jordan river as laid out in the Sykes–Picot Agreement. That year, two principles emerged from the British government. The first was that the Palestine government would not extend east of the Jordan; the second was the government's chosen – albeit disputed – interpretation of the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence, which proposed that Transjordan be included in the area of "Arab independence" (excluding Palestine).

Regarding Faisal's Arab Kingdom of Syria

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, No ...

, the French removed Hashim al-Atassi

Hashim al-Atassi ( ar, هاشم الأتاسي, Hāšim al-ʾAtāsī; 11 January 1875 – 5 December 1960) was a Syrian nationalist and statesman and the President of Syria from 1936 to 1939, 1949 to 1951 and 1954 to 1955.

Background and e ...

's newly proclaimed nationalist government and expelled King Faisal from Syria after the 23 July 1920 Battle of Maysalun

The Battle of Maysalun ( ar, معركة ميسلون), also called the Battle of Maysalun Pass or the Battle of Khan Maysalun (french: Bataille de Khan Mayssaloun), was a four-hour battle fought between the forces of the Arab Kingdom of Syria an ...

. The French formed a new Damascus state after the battle, and refrained from extending their rule into the southern part of Faisal's domain; Transjordan became for a time a no-man's land or, as Samuel put it, "politically derelict".

After the French occupation, the British suddenly wanted to know "what is the 'Syria' for which the French received a mandate at San Remo?" and "does it include Transjordania?". British Foreign Minister Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), styled Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and then Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman ...

ultimately decided that it did not; Transjordan would remain independent, but in a close relationship with Palestine. On 6 August 1920, Curzon wrote to newly appointed High Commissioner Herbert Samuel about Transjordan: "I suggest that you should let it be known forthwith that in the area south of the Sykes–Picot line, we will not admit French authority and that our policy for this area to be independent but in closest relations with Palestine." Samuel replied to Curzon, "After the fall of Damascus a fortnight ago ... Sheiks and tribes east of Jordan utterly dissatisfied with Shareefian Government most unlikely would accept revival", and asked to put parts of Transjordan directly under his administrative control. Two weeks later, on 21 August, Samuel visited Transjordan without authorisation from London; at a meeting with 600 leaders in Salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quantitie ...

, he announced the independence of the area from Damascus and its absorption into the mandate (proposing to quadruple the area under his control by tacit capitulation). Samuel assured his audience that Transjordan would not be merged with Palestine. Curzon was in the process of reducing British military expenditures, and was unwilling to commit significant resources to an area considered of marginal strategic value. He immediately repudiated Samuel's action, and sent (via the Foreign Office) a reiteration of his instructions to minimize the scope of British involvement in the area: "There must be no question of setting up any British administration in that area". At the end of September 1920, Curzon instructed an Assistant Secretary at the Foreign Office, Robert Vansittart, to leave the eastern boundary of Palestine undefined and avoid "any definite connection" between Transjordan and Palestine to leave the way open for an Arab government in Transjordan. Curzon subsequently wrote in February 1921, "I am very concerned about Transjordania ... Sir H.Samuel wants it as an annex of Palestine and an outlet for the Jews. Here I am against him."

Abdullah

Abdullah may refer to:

* Abdullah (name), a list of people with the given name or surname

* Abdullah, Kargı, Turkey, a village

* ''Abdullah'' (film), a 1980 Bollywood film directed by Sanjay Khan

* '' Abdullah: The Final Witness'', a 2015 Pakis ...

, the brother of recently deposed King Faisal, marched into Ma'an at the head of an army of from 300 to 2,000 men on 21 November 1920. Between then and the end of March 1921, Abdullah's army occupied all of Transjordan with some local support and no British opposition.

The Cairo Conference

The Cairo Conference (codenamed Sextant) also known as the First Cairo Conference, was one of the 14 summit meetings during World War II that occurred on November 22–26, 1943. The Conference was held in Cairo, Egypt, between the United Kingdo ...

was convened on 12 March 1921 by Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, then Britain's Colonial Secretary, and lasted until 30 March. It was intended to endorse an arrangement whereby Transjordan would be added to the Palestine mandate, with Abdullah as the emir under the authority of the High Commissioner, and with the condition that the Jewish National Home provisions of the Palestine mandate would not apply there. On the first day of the conference, the Middle East Department of the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of col ...

set out the situation of Transjordan in a memorandum. On 21 March 1921, the Foreign and Colonial Office legal advisers decided to introduce Article 25 into the Palestine Mandate to allow for the addition of Transjordan.

Drafting

The intended mandatory powers were required to submit written statements to the League of Nations during the Paris Peace Conference proposing the rules of administration in the mandated areas. Drafting of the Palestine mandate began well before it was formally awarded at San Remo in April 1920, since it was evident after the end of the war that Britain was the favored power in the region. The mandate had a number of drafts: the February 1919 Zionist proposals to the peace conference; a December 1919 "compromise" draft between the British and the Zionists; a June 1920 draft after Curzon's "watering down", and the December 1920 draft submitted to the League of Nations for comment.

1919: Initial Zionist-British discussions

The February 1919 Zionist Proposal to the Peace Conference was not discussed at the time, since the Allies' discussions were focused elsewhere. It was not until July 1919 that direct negotiations began between the British Foreign Office and the Zionists, after the production of a full draft mandate by the British. The British draft contained 29 articles, compared to the Zionist proposal's five articles. However, the Zionist Organisation Report stated that a draft was presented by the Zionist Organization to the British on 15 July 1919.[''The Zionist Congress'']

. The Canadian Jewish Chronicle, p. 6, 9 September 1921. At news.google.com, p. 3

Balfour authorised diplomatic secretary Eric Forbes Adam

Eric Graham Forbes Adam (3 October 1888 – 7 July 1925) was a British diplomat and First Secretary to the Foreign Office.

Adam was born in Malabar Hill, Bombay, India, the second son of Sir Frank Forbes Adam, 1st Baronet. His older brother ...

to begin negotiations with the Zionist Organization. On the Zionist side, the drafting was led by Ben Cohen on behalf of Weizmann, Felix Frankfurter and other Zionist leaders. By December 1919, they had negotiated a "compromise" draft.

1920: Curzon negotiations

Although Curzon took over from Balfour in October, he did not play an active role in the drafting until mid-March. Israeli historian

Although Curzon took over from Balfour in October, he did not play an active role in the drafting until mid-March. Israeli historian Dvorah Barzilay-Yegar

Dvorah Barzilay-Yegar (born 1933) is an Israeli historian, who has carried out many years of scholarly research into the life and political activities of Chaim Weizmann, the first President of Israel.

Biography

Education

Barzilay was brought up ...

notes that he was sent a copy of the December draft and commented, "... the Arabs are rather forgotten ...". When Curzon received the draft of 15 March 1920, he was "far more critical" and objected to "... formulations that would imply recognition of any legal rights ..." (for example, that the British government would be "responsible for placing Palestine under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of a Jewish national home and the development of a self-governing Commonwealth ..."). Curzon insisted on revisions until the 10 June draft removed his objections; the paragraph recognising the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine was removed from the preamble, and "self-governing commonwealth" was replaced by "self-governing institutions". "The recognition of the establishment of the Jewish National Home as the guiding principle in the execution of the Mandate" was omitted.

After strenuous objection to the proposed changes, the statement concerning the historical connections of the Jews with Palestine was re-incorporated into the Mandate in December 1920.[ The draft was submitted to the League of Nations on 7 December 1920, and was published in the ''Times'' on 3 February 1921.

]

1921: Transjordan article

The inclusion of Article 25 was approved by Curzon on 31 March 1921, and the revised final draft of the mandate was forwarded to the League of Nations on 22 July 1922. Article 25 permitted the mandatory to "postpone or withhold application of such provisions of the mandate as he may consider inapplicable to the existing local conditions" in that region. The final text of the Mandate includes an Article 25, which states:

In the territories lying between the Jordan iver

Iver is a large civil parish in Buckinghamshire, England. In addition to the central clustered village, the parish includes the residential neighbourhoods of Iver Heath and Richings Park.

Geography, transport and economy

Part of the 43-square- ...

and the eastern boundary of Palestine as ultimately determined, the Mandatory shall be entitled, with the consent of the Council of the League of Nations, to postpone or withhold application of such provisions of this mandate as he may consider inapplicable to the existing local conditions, and to make such provision for the administration of the territories as he may consider suitable to those conditions.

The new article was intended to enable Britain "to set up an Arab administration and to withhold indefinitely the application of those clauses of the mandate which relate to the establishment of the National Home for the Jews", as explained in a Colonial Office letter three days later. This created two administrative areas – Palestine, under direct British rule, and the autonomous Emirate of Transjordan

The Emirate of Transjordan ( ar, إمارة شرق الأردن, Imārat Sharq al-Urdun, Emirate of East Jordan), officially known as the Amirate of Trans-Jordan, was a British protectorate established on 11 April 1921, under the rule of the Hashemite family – in accordance with the British Government's amended interpretation of the 1915 McMahon–Hussein Correspondence. At discussions in Jerusalem on 28 March, Churchill proposed his plan to Abdullah that Transjordan would be accepted into the mandatory area as an Arab country apart from Palestine and that it would be (initially for six months) under the nominal rule of the Emir Abdullah. Churchill said that Transjordan would not form part of the Jewish national home to be established west of the River Jordan:Trans-Jordania would not be included in the present administrative system of Palestine, and therefore the Zionist clauses of the mandate would not apply. Hebrew would not be made an official language in Trans-Jordania and the local Government would not be expected to adopt any measures to promote Jewish immigration and colonisation.

Abdullah's six-month trial was extended, and by the following summer he began to voice his impatience at the lack of formal confirmation.

1921–22: Palestinian Arab attempted involvement

The drafting was carried out with no input from any Arabs, despite the fact that their disagreement with the Balfour Declaration was well known. Palestinian political opposition began to organise in 1919 in the form of the Palestine Arab Congress

The Palestine Arab Congress was a series of congresses held by the Palestinian Arab population, organized by a nationwide network of local Muslim-Christian Associations, in the British Mandate of Palestine. Between 1919 and 1928, seven congresses w ...

, which formed from the local Muslim-Christian Associations In 1918, following the British defeat of the Ottoman army and their establishment of a Military Government in Palestine, a number of political clubs called Muslim-Christian Associations (''Al-Jam'iah al-Islamiya al-Massihiya'') were established in a ...

. In March 1921, new British Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill came to the region to form British policy on the ground at the Cairo Conference. The leader of the Palestine congress, Musa al-Husayni

Musa Kazim Pasha al-Husayni ( ar, موسى كاظم الحسيني, ) (1853 in Jerusalem – 27 March 1934) held a series of senior posts in the Ottoman administration. He belonged to the prominent al-Husayni family and was mayor of Jerusalem (1 ...

, had tried to present the views of the Executive Committee in Cairo and (later) Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

but was rebuffed both times. In the summer of 1921, the 4th Palestine Arab Congress sent a delegation led by Musa al-Husayni to London to negotiate on behalf of the Muslim and Christian population. On the way, the delegation held meetings with Pope Benedict XV

Pope Benedict XV (Latin: ''Benedictus XV''; it, Benedetto XV), born Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa, name=, group= (; 21 November 185422 January 1922), was head of the Catholic Church from 1914 until his death in January 1922. His ...

and diplomats from the League of Nations in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

(where they also met Balfour, who was non-committal). In London, they had three meetings with Winston Churchill in which they called for reconsideration of the Balfour Declaration, revocation of the Jewish National Home policy, an end to Jewish immigration and that Palestine should not be severed from its neighbours. All their demands were rejected, although they received encouragement from some Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

Members of Parliament.

Musa al-Husayni led a 1922 delegation to Ankara

Ankara ( , ; ), historically known as Ancyra and Angora, is the capital of Turkey. Located in the central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5.1 million in its urban center and over 5.7 million in Ankara Province, maki ...

and then to the Lausanne Conference, where (after Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

's victories against the Greek army in Turkey) the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

was about to be re-negotiated. The Palestinian delegation hoped that with Atatürk's support, they would be able to get the Balfour Declaration and mandate policy omitted from the new treaty. The delegation met with Turkey's lead negotiator, İsmet Pasha, who promised that "Turkey would insist upon the Arabs’ right of self-determination and ... the Palestinian delegation should be permitted to address the conference"; however, he avoided further meetings and other members of the Turkish delegation made clear their intention to "accept the post–World War I status quo". During the negotiations, Ismet Pasha refused to recognise or accept the mandates; although they were not referenced in the final treaty, it had no impact on the implementation of the mandate policy set in motion three years earlier.

1922: Final amendments

Each of the principal Allied powers had a hand in drafting the proposed mandate, although some (including the United States) had not declared war on the Ottoman Empire and did not become members of the League of Nations.

Approvals

British Parliament

British public and government opinion became increasingly opposed to state support for Zionism, and even Sykes had begun to change his views in late 1918. In February 1922 Churchill telegraphed Samuel, who had begun his role as High Commissioner for Palestine 18 months earlier, asking for cuts in expenditure and noting:

The House of Lords rejected a Palestine Mandate incorporating the Balfour Declaration by 60 votes to 25 after the June 1922 issuance of the Churchill White Paper, following a motion proposed by Lord Islington

John Poynder Dickson-Poynder, 1st Baron Islington, (31 October 1866 – 6 December 1936), born John Poynder Dickson and known as Sir John Poynder Dickson-Poynder from 1884 to 1910, was a British politician. He was Governor of New Zealand between ...

. The vote was only symbolic, since it was subsequently overruled by a vote in the House of Commons after a tactical pivot and a number of promises by Churchill.

In February 1923, after a change in government, Cavendish laid the foundation for a secret review of Palestine policy in a lengthy memorandum to the Cabinet:

His cover note asked for a statement of policy to be made as soon as possible, and for the cabinet to focus on three questions: (1) whether or not pledges to the Arabs conflict with the Balfour declaration; (2) if not, whether the new government should continue the policy set down by the old government in the 1922 White Paper and (3) if not, what alternative policy should be adopted.

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

, who took over as Prime Minister on 22 May 1923, set up a cabinet subcommittee in June 1923 whose terms of reference were to "examine Palestine policy afresh and to advise the full Cabinet whether Britain should remain in Palestine and whether if she remained, the pro-Zionist policy should be continued". The Cabinet approved the report of this subcommittee on 31 July 1923; when presenting the subcommittee's report to the Cabinet, Curzon concluded that "wise or unwise, it is well nigh impossible for any government to extricate itself without a substantial sacrifice of consistency and self-respect, if not honour." Describing it as "nothing short of remarkable", international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

specialist Professor John B. Quigley

John B. Quigley (born 1940) is a professor of law at the Moritz College of Law at the Ohio State University, where he is the Presidents' Club Professor of Law. In 1995 he was recipient of the Ohio State University Distinguished Scholar Award. Born ...

noted that the government was admitting to itself that its support for Zionism had been prompted by considerations having nothing to do with the merits of Zionism or its consequences for Palestine. Documents related to the 1923 reappraisal remained secret until the early 1970s.

United States

The United States was not a member of the League of Nations. On 23 February 1921, two months after the draft mandates had been submitted to the League, the U.S. requested permission to comment before the mandate's consideration by the Council of the League of Nations; the Council agreed to the request a week later. The discussions continued until 14 May 1922, when the U.S. government announced the terms of an agreement with the United Kingdom about the Palestine mandate. The terms included a stipulation that "consent of the United States shall be obtained before any alteration is made in the text of the mandate". Despite opposition from the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the country's fore ...

, this was followed on 21 September 1922 by the Lodge–Fish Resolution

The Lodge–Fish Resolution was a joint resolution of both houses of the US Congress that endorsed the British Mandate for Palestine. It was introduced in June 1922 by Hamilton Fish III, a Republican New York Representative, and Henry Cabot Lodg ...

, a congressional

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

endorsement of the Balfour Declaration.

On 3 December 1924 the U.S. signed the Palestine Mandate Convention, a bilateral treaty with Britain in which the United States "consents to the administration" (Article 1) and which dealt with eight issues of concern to the United States (including property rights and business interests). The State Department prepared a report documenting its position on the mandate.

Council of the League of Nations: Mandate

On 17 May 1922, in a discussion of the date on which the question of the Draft Mandate for Palestine should be placed on the agenda of the Council of the League of Nations, Lord Balfour informed the Council of his government's understanding of the role of the League in the creation of mandates:

heMandates were not the creation of the League, and they could not in substance be altered by the League. The League's duties were confined to seeing that the specific and detailed terms of the mandates were in accordance with the decisions taken by the Allied and Associated Powers, and that in carrying out these mandates the Mandatory Powers should be under the supervision—not under the control—of the League. A mandate was a self-imposed limitation by the conquerors on the sovereignty which they exercised over the conquered territory.

The Council of the League of Nations met between 19 and 24 July 1922 to approve the class A mandates for Palestine and Syria ( minutes of the meetings can be read here). The Palestine mandate was approved on 22 July 1922 at a private meeting of the Council of the League of Nations at St. James Palace in London, giving the British formal international recognition of the position they had held ''de facto'' in the region since the end of 1917 in Palestine and since 1920–21 in Transjordan. The Council stated that the mandate was approved and would come into effect "automatically" when the dispute between France and Italy was resolved. A public statement confirming this was made by the president of the council on 24 July. With the Fascists gaining power in Italy in October 1922, new Italian Prime Minister Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

delayed the mandates' implementation. On 23 August 1923, the Turkish assembly in Ankara ratified the Treaty of Lausanne by 215 of 235 votes.

The Council of the League of Nations determined that the two mandates had come into effect at its 29 September 1923 meeting. The dispute between France and Italy was resolved by the Turkish ratification.

Council of the League of Nations: Transjordan memorandum

Shortly after the mandate's approval in July 1922, the Colonial Office prepared a memorandum to implement Article 25. On 16 September 1922, the League of Nations approved a British memorandum detailing its intended implementation of the clause excluding Transjordan from the articles related to Jewish settlement.[''League of Nations Official Journal'', Nov. 1922, pp. 1188–1189.] When the memorandum was submitted to the Council of the League of Nations, Balfour explained the background; according to the minutes, "Lord Balfour reminded his colleagues that Article 25 of the mandate for Palestine as approved by the Council in London on July 24th, 1922, provides that the territories in Palestine which lie east of the Jordan should be under a somewhat different regime from the rest of Palestine ... The British Government now merely proposed to carry out this article. It had always been part of the policy contemplated by the League and accepted by the British Government, and the latter now desired to carry it into effect. In pursuance of the policy, embodied in Article 25, Lord Balfour invited the Council to pass a series of resolutions which modified the mandate as regards those territories. The object of these resolutions was to withdraw from Trans-Jordania the special provisions which were intended to provide a national home for the Jews west of the Jordan."

Turkey

Turkey was not a member of the League of Nations at the time of the negotiations; on the losing side of World War I, they did not join until 1932. Decisions about mandates over Ottoman territory made by the Allied Supreme Council

The Supreme War Council was a central command based in Versailles that coordinated the military strategy of the principal Allies of World War I: Britain, France, Italy, the US and Japan. It was founded in 1917 after the Russian revolution and wit ...

at the San Remo conference were documented in the Treaty of Sèvres, which was signed on behalf of the Ottoman Empire and the Allies on 10 August 1920. The treaty was never ratified by the Ottoman government, however,Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

. Atatürk expressed disdain for the treaty, and continued what was known as the Turkish War of Independence. The Conference of Lausanne began in November 1922, with the intention of negotiating a treaty to replace the failed Treaty of Sèvres. In the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conflic ...

, signed on 24 July 1923, the Turkish government recognised the detachment of the regions south of the frontier agreed in the Treaty of Ankara (1921)

The Ankara Agreement (1921) (or the Accord of Ankara; Franklin-Bouillon Agreement; Franco-Turkish Agreement of Ankara, Turkish: ''Ankara Anlaşması'' French: Traité d'Ankara) was signed on 20 October 1921"Ankara, Treaty of" in ''The New Encycl ...

and renounced its sovereignty over Palestine.[

]

Key issues

National home for the Jewish people (Preamble and Articles 2, 4, 6, 7, 11)

According to the second paragraph of the mandate's preamble,

According to the second paragraph of the mandate's preamble,

Whereas the Principal Allied Powers have also agreed that the Mandatory should be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 2nd, 1917, by the Government of His Britannic Majesty, and adopted by the said Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing should be done which might prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country ...

Weizmann noted in his memoirs that he considered the most important part of the mandate, and the most difficult negotiation, the subsequent clause in the preamble which recognised "the historical connection of the Jews with Palestine". Curzon and the Italian and French governments rejected early drafts of the mandate because the preamble had contained a passage which read, "Recognising, moreover, the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and ''the claim which this gives them to reconstitute it their national home''..." The Palestine Committee set up by the Foreign Office recommended that the reference to "the claim" be omitted. The Allies had already noted the historical connection in the Treaty of Sèvres, but had not acknowledged a legal claim. Lord Balfour suggested an alternative which was accepted and included in the preamble immediately after the paragraph quoted above:

Whereas recognition has thereby .e. by the Treaty of Sèvresbeen given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine, and to the grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country;

In the body of the document, the Zionist Organization was mentioned in Article 4; in the September 1920 draft, a qualification was added which required that "its organisation and constitution" must be "in the opinion of the Mandatory appropriate". A "Jewish agency" was mentioned three times: in Articles 4, 6 and 11. Article 4 of the mandate provided for "the recognition of an appropriate Jewish agency as a public body for the purpose of advising and co-operating with the Administration of Palestine in such economic, social and other matters as may affect the establishment of the Jewish National Home and the interests of the Jewish population of Palestine," effectively establishing what became the "Jewish Agency for Palestine

The Jewish Agency for Israel ( he, הסוכנות היהודית לארץ ישראל, translit=HaSochnut HaYehudit L'Eretz Yisra'el) formerly known as The Jewish Agency for Palestine, is the largest Jews, Jewish non-profit organization in the w ...

". Article 7 stated, "The Administration of Palestine shall be responsible for enacting a nationality law. There shall be included in this law provisions framed so as to facilitate the acquisition of Palestinian citizenship by Jews who take up their permanent residence in Palestine."

Religious and communal issues (Articles 13–16 and 23)

Religious and communal guarantees, such as freedom of religion and education, were made in general terms without reference to a specific religion. The Vatican and the Italian and French governments concentrated their efforts on the issue of the Holy Places and the rights of the Christian communities, making their legal claims on the basis of the former Protectorate of the Holy See and the French Protectorate of Jerusalem

Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire were contracts between the Ottoman Empire and other powers in Europe, particularly France. Turkish capitulations, or Ahidnâmes were generally bilateral acts whereby definite arrangements were entered into ...

. The Catholic powers saw an opportunity to reverse the gains made by the Greek and Russian Orthodox communities in the region during the previous 150 years, as documented in the Status Quo

is a Latin phrase meaning the existing state of affairs, particularly with regard to social, political, religious or military issues. In the sociological sense, the ''status quo'' refers to the current state of social structure and/or values. W ...

. The Zionists had limited interest in this area.

Britain would assume responsibility for the Holy Places under Article 13 of the mandate. The idea of an International Commission to resolve claims on the Holy Places, formalised in Article 95 of the Treaty of Sèvres, was taken up again in article 14 of the Palestinian Mandate. Negotiations about the commission's formation and role were partly responsible for the delay in ratifying the mandate. Article 14 of the mandate required Britain to establish a commission to study, define, and determine the rights and claims relating to Palestine's religious communities. This provision, which called for the creation of a commission to review the Status Quo of the religious communities, was never implemented.

Article 15 required the mandatory administration to ensure that complete freedom of conscience and the free exercise of all forms of worship were permitted. According to the article, "No discrimination of any kind shall be made between the inhabitants of Palestine on the ground of race, religion or language. No person shall be excluded from Palestine on the sole ground of his religious belief." The High Commissioner established the authority of the Orthodox Rabbinate over the members of the Jewish community and retained a modified version of the Ottoman Millet

In the Ottoman Empire, a millet (; ar, مِلَّة) was an independent court of law pertaining to "personal law" under which a confessional community (a group abiding by the laws of Muslim Sharia, Christian Canon law, or Jewish Halakha) was al ...

system. Formal recognition was extended to eleven religious communities, which did not include non-Orthodox Jews or the Protestant Christian denominations.

Transjordan (Article 25 and Transjordan memorandum)

The public clarification and implementation of Article 25, more than a year after it was added to the mandate, misled some "into imagining that Transjordanian territory was covered by the conditions of the Mandate as to the Jewish National Home before August 1921". This would, according to professor of modern Jewish history Bernard Wasserstein

Bernard Wasserstein (born 22 January 1948 in London) is a British historian.

Early life

Bernard Wasserstein was born in London on 22 January 1948. Wasserstein's father, Abraham Wasserstein (1921–1995), born in Frankfurt, was Professor of Class ...

, result in "the myth of Palestine's 'first partition' hich became

Ij ( fa, ايج, also Romanized as Īj; also known as Hich and Īch) is a village in Golabar Rural District, in the Central District of Ijrud County, Zanjan Province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also ...

part of the concept of 'Greater Israel' and of the ideology of Jabotinsky Zhabotinsky or Jabotinsky (Ukrainian: Жаботинський) is a masculine Ukrainian toponymic surname referring to the village of Zhabotin. Its feminine counterpart is Zhabotinskaya, Jabotinskaya, Zhabotinska or Jabotinska. Notable people with ...

's Revisionist movement". Palestinian-American academic Ibrahim Abu-Lughod

Ibrahim Abu-Lughod ( ar, إبراهيم أبو لغد, February 15, 1929 – May 23, 2001) was a Palestinian (later American) academic, characterised by Edward Said as "Palestine's foremost academic and intellectual"Said 2001 and by Rashid Khalid ...

, then chair of the Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

political science department, suggested that the "Jordan as a Palestinian State" references made by Israeli spokespeople may reflect "the same isnderstanding".

On 25 April 1923, five months before the mandate came into force, the independent administration was recognised in a statement made in Amman: Subject to the approval of the League of Nations, His Britannic Majesty will recognise the existence of an independent Government in Trans-jordan under the rule of His Highness the Amir Abdullah, provided that such Government is constitutional and places His Britannic Majesty in a position to fulfil his international obligations in respect of the territory by means of an Agreement to be concluded with His Highness.

Legality