Palace School Of Aachen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Palace of Aachen was a group of buildings with residential, political and religious purposes chosen by Charlemagne to be the centre of power of the Carolingian Empire. The palace was located at the north of the current city of

The Palace of Aachen was a group of buildings with residential, political and religious purposes chosen by Charlemagne to be the centre of power of the Carolingian Empire. The palace was located at the north of the current city of

In ancient times, the Romans chose the site of Aachen for its thermal springs and its forward position towards

In ancient times, the Romans chose the site of Aachen for its thermal springs and its forward position towards

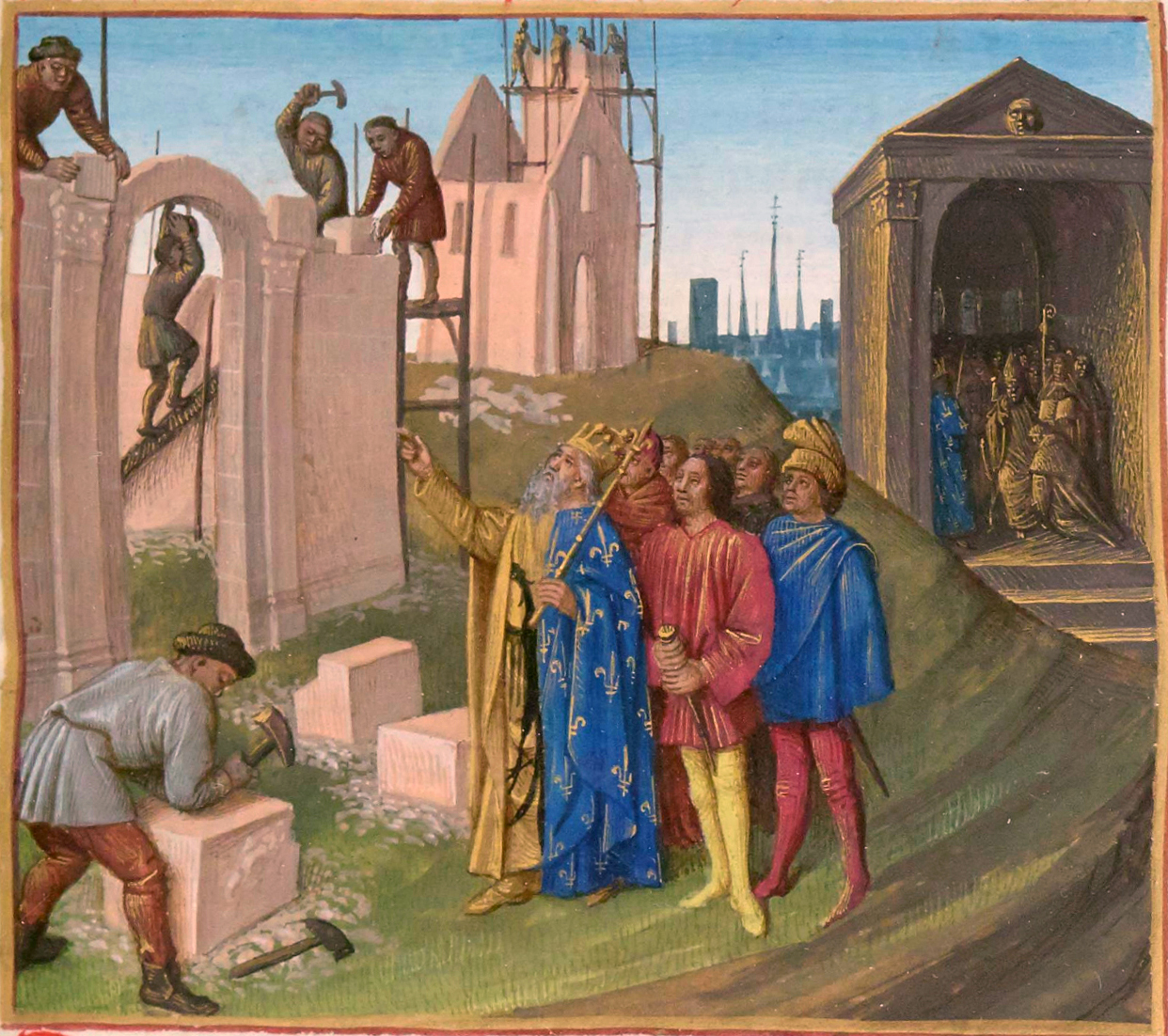

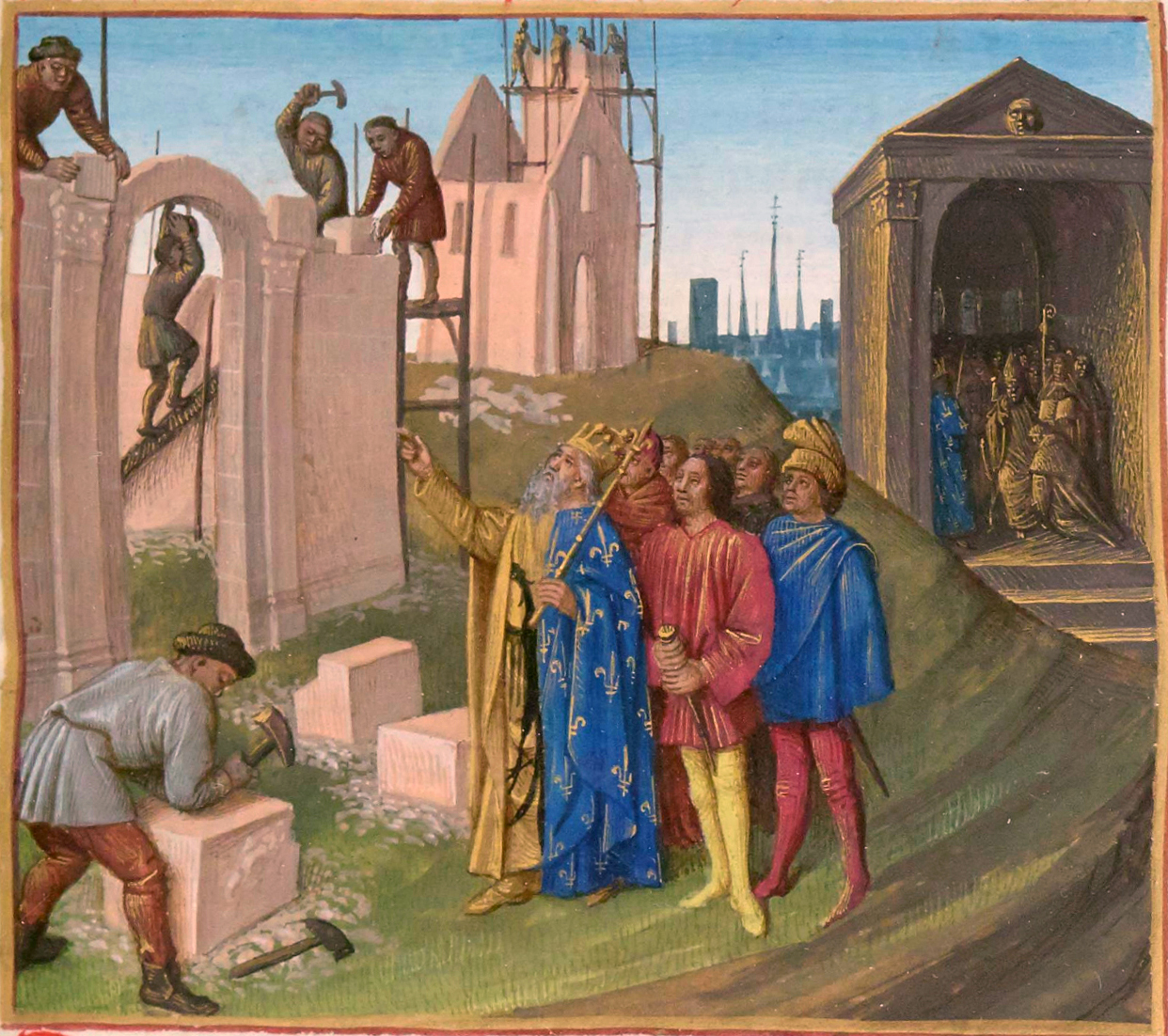

The site of Aachen was chosen by Charlemagne after careful consideration in a key moment of his reign. Since his advent as King of the Franks, Charlemagne had led numerous military expeditions that had both filled his treasury and enlarged his realm, most notably towards the East. He conquered

The site of Aachen was chosen by Charlemagne after careful consideration in a key moment of his reign. Since his advent as King of the Franks, Charlemagne had led numerous military expeditions that had both filled his treasury and enlarged his realm, most notably towards the East. He conquered  Besides, settling down in Aachen enabled Charlemagne to control from closer the operations in Saxony. Charlemagne also considered other advantages of the place: surrounded with forest abounding in game, he intended to abandon himself to

Besides, settling down in Aachen enabled Charlemagne to control from closer the operations in Saxony. Charlemagne also considered other advantages of the place: surrounded with forest abounding in game, he intended to abandon himself to

Historians know almost nothing about the architect of the Palace of Aachen, Odo of Metz. His name appears in the works of Eginhard (c. 775–840), Charlemagne's biographer. He is supposed to have been an educated cleric, familiar with liberal arts, especially ''

Historians know almost nothing about the architect of the Palace of Aachen, Odo of Metz. His name appears in the works of Eginhard (c. 775–840), Charlemagne's biographer. He is supposed to have been an educated cleric, familiar with liberal arts, especially ''

Located at the North of the Palace complex, the great Council Hall ('' aula regia'' or ''aula palatina'' in Latin) was used to house the speeches delivered by the Emperor once a year. This occasion gathered the highest officials in the

Located at the North of the Palace complex, the great Council Hall ('' aula regia'' or ''aula palatina'' in Latin) was used to house the speeches delivered by the Emperor once a year. This occasion gathered the highest officials in the  The dimensions of the hall (1,000 m2) were suitable to the reception of several hundreds of people at the same time: although the building has been destroyed, it is known it was 47,42 metres long, 20,76 metres large and 21 metres high. The plan seems to be based upon the Roman '' aula palatina'' of Trier. The structure was made of brick, and the shape was that of a civil basilica with three apses: the largest one (17,2 m), located to the West, was dedicated to the king and his suite. The two other apses, to the North and South, were smaller. Light entered through two rows of windows. The inside was probably decorated with paintings depicting heroes both from the Ancient times and contemporary. A wooden gallery girdled the building between the two rows of windows. From this gallery could be seen the market that was held North of the Palace. A gallery with porticos on the southern side of the hall gave access to the building. The southern apse cut through the middle of this entrance.

The dimensions of the hall (1,000 m2) were suitable to the reception of several hundreds of people at the same time: although the building has been destroyed, it is known it was 47,42 metres long, 20,76 metres large and 21 metres high. The plan seems to be based upon the Roman '' aula palatina'' of Trier. The structure was made of brick, and the shape was that of a civil basilica with three apses: the largest one (17,2 m), located to the West, was dedicated to the king and his suite. The two other apses, to the North and South, were smaller. Light entered through two rows of windows. The inside was probably decorated with paintings depicting heroes both from the Ancient times and contemporary. A wooden gallery girdled the building between the two rows of windows. From this gallery could be seen the market that was held North of the Palace. A gallery with porticos on the southern side of the hall gave access to the building. The southern apse cut through the middle of this entrance.

The Palatine Chapel was located at the other side of the palace complex, at the South. A stone gallery linked it to the ''aula regia''. It symbolized another aspect of Charlemagne's power, religious power. Legend has it that the building was consecrated in 805 by

The Palatine Chapel was located at the other side of the palace complex, at the South. A stone gallery linked it to the ''aula regia''. It symbolized another aspect of Charlemagne's power, religious power. Legend has it that the building was consecrated in 805 by

The covered gallery was a hundred meters long. It linked the council hall to the chapel; a monumental porch in its middle was used as the main entrance. A room for legal hearing was located on the second floor. The king dispensed justice in this place, although affairs in which important people were involved were handled in the ''aula regia''. When the king was away, this task fell on the

The covered gallery was a hundred meters long. It linked the council hall to the chapel; a monumental porch in its middle was used as the main entrance. A room for legal hearing was located on the second floor. The king dispensed justice in this place, although affairs in which important people were involved were handled in the ''aula regia''. When the king was away, this task fell on the

The thermal complex, located in the Southeast, measured 50 acres and included several buildings near the sources of the Emperor and Quirinus. Eginhard mentions a

The thermal complex, located in the Southeast, measured 50 acres and included several buildings near the sources of the Emperor and Quirinus. Eginhard mentions a

The other buildings are not easy to identify because of the lack of detailed enough written accounts. Charlemagne's and his family's apartments seem to have been located in the north-eastern part of the palace complex; his room may have been on the second floor. Some of the servants of the palace must have lived in the western part, and some in the city. The Emperor is said to have owned a library but its exact location is hard to assess. The palace also housed other areas dedicated to artistic creation: a scriptorium that saw the writing of several precious manuscripts ('' Drogo Sacramentary'', '' Godescalc Evangelistary''…), a goldsmith workshop and an ivory workshop. There was also a mint that was still operational in the 13th century.

The palace also housed the literary activities of the Palace Academy. This circle of scholars did not gather in a definite building: Charlemagne liked to listen to poems while he was swimming and eating. The Palace school provided education to the ruler's children and the "nourished ones" (''nutriti'' in Latin), aristocrat sons that were to serve the king.

Outside of the palace complex were also a gynaeceum,

The other buildings are not easy to identify because of the lack of detailed enough written accounts. Charlemagne's and his family's apartments seem to have been located in the north-eastern part of the palace complex; his room may have been on the second floor. Some of the servants of the palace must have lived in the western part, and some in the city. The Emperor is said to have owned a library but its exact location is hard to assess. The palace also housed other areas dedicated to artistic creation: a scriptorium that saw the writing of several precious manuscripts ('' Drogo Sacramentary'', '' Godescalc Evangelistary''…), a goldsmith workshop and an ivory workshop. There was also a mint that was still operational in the 13th century.

The palace also housed the literary activities of the Palace Academy. This circle of scholars did not gather in a definite building: Charlemagne liked to listen to poems while he was swimming and eating. The Palace school provided education to the ruler's children and the "nourished ones" (''nutriti'' in Latin), aristocrat sons that were to serve the king.

Outside of the palace complex were also a gynaeceum,

The palace borrows several elements of Roman civilization. The ''Aula Palatina'' follows a basilical plan. Basilicas in ancient times were public buildings where the city's affairs were discussed. The chapel follows models from ancient Rome: grids exhibit antique decorations ( acanthus) and columns are topped by

The palace borrows several elements of Roman civilization. The ''Aula Palatina'' follows a basilical plan. Basilicas in ancient times were public buildings where the city's affairs were discussed. The chapel follows models from ancient Rome: grids exhibit antique decorations ( acanthus) and columns are topped by

It is difficult to know whether other Carolingian palaces did imitate that of Aachen, as most of them have been destroyed. However, the constructions of Aachen were not the only ones undertaken under Charlemagne: 16

It is difficult to know whether other Carolingian palaces did imitate that of Aachen, as most of them have been destroyed. However, the constructions of Aachen were not the only ones undertaken under Charlemagne: 16

Yet the memory of Charlemagne's Empire remained fresh and became a symbol of German power. In the 10th century, Otto I (912–973) was crowned King of Germany in Aachen (936). The three-part ceremony took place in several locations within the palace: first in the courtyard (election by the dukes), then in the chapel (handing of the insignia of the Kingdom), finally in the palace (banquet). During the ceremony, Otto sat on Charlemagne's throne. Afterwards, and until the 16th century, all the German Emperors were crowned firstly in Aachen and then in Rome, which highlights the attachment to Charlemagne's political legacy. The Golden Bull of 1356 confirmed that coronations were to take place in the palatine chapel.

Otto II (955–983) lived in Aachen with his wife Theophanu. In the summer of 978 Lothair of France led a raid on Aachen but the Imperial family avoided capture. Relating these events, Richer of Reims states the existence of a bronze eagle, the exact location of which is unknown:

Yet the memory of Charlemagne's Empire remained fresh and became a symbol of German power. In the 10th century, Otto I (912–973) was crowned King of Germany in Aachen (936). The three-part ceremony took place in several locations within the palace: first in the courtyard (election by the dukes), then in the chapel (handing of the insignia of the Kingdom), finally in the palace (banquet). During the ceremony, Otto sat on Charlemagne's throne. Afterwards, and until the 16th century, all the German Emperors were crowned firstly in Aachen and then in Rome, which highlights the attachment to Charlemagne's political legacy. The Golden Bull of 1356 confirmed that coronations were to take place in the palatine chapel.

Otto II (955–983) lived in Aachen with his wife Theophanu. In the summer of 978 Lothair of France led a raid on Aachen but the Imperial family avoided capture. Relating these events, Richer of Reims states the existence of a bronze eagle, the exact location of which is unknown:

In 881, a Viking raid damaged the palace and the chapel. In 1000, the Holy Roman Emperor

In 881, a Viking raid damaged the palace and the chapel. In 1000, the Holy Roman Emperor

Aachen cathedral in pictures

{{DEFAULTSORT:Palace Of Aachen Buildings and structures completed in the 8th century Palaces in North Rhine-Westphalia Carolingian architecture Charlemagne

Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

, today in the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

Land of North Rhine-Westphalia. Most of the Carolingian palace was built in the 790s but the works went on until Charlemagne's death in 814. The plans, drawn by Odo of Metz, were part of the programme of renovation of the kingdom decided by the ruler. Today much of the palace is destroyed, but the Palatine Chapel has been preserved and is considered as a masterpiece of Carolingian architecture and a characteristic example of architecture from the Carolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. It occurred from the late 8th century to the 9th century, taking inspiration from the State church of the Roman Emp ...

.

Historical context

The palace before Charlemagne

In ancient times, the Romans chose the site of Aachen for its thermal springs and its forward position towards

In ancient times, the Romans chose the site of Aachen for its thermal springs and its forward position towards Germania

Germania ( ; ), also called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman province of the same name, was a large historical region in north- ...

. The site, called ''Aquae Granni'', was equipped with A. Erlande-Brandeburg, A.-B. Erlande-Brandeburg, ''Histoire de l’architecture française'', 1999, p. 104 of '' thermae'' that remained in use from the 1st to the 4th century.J. Favier, ''Charlemagne'', 1999, p. 285 The Roman city grew in connection with the ''thermae'' according to a classical grid plan

In urban planning, the grid plan, grid street plan, or gridiron plan is a type of city plan in which streets run at right angles to each other, forming a grid.

Two inherent characteristics of the grid plan, frequent intersections and orthogona ...

similar to that of Roman legions' camps. A palace was used to accommodate the governor of the province or the Emperor. In the 4th century, the city and the palace were destroyed during the Barbarian invasions

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roman ...

. Clovis

Clovis may refer to:

People

* Clovis (given name), the early medieval (Frankish) form of the name Louis

** Clovis I (c. 466 – 511), the first king of the Franks to unite all the Frankish tribes under one ruler

** Clovis II (c. 634 – c. 657), ...

made Paris the capital of the Frankish Kingdom

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks dur ...

, and Aachen Palace was abandoned until the advent of the Carolingian dynasty. The Pippinid

The Pippinids and the Arnulfings were two Frankish aristocratic families from Austrasia during the Merovingian period. They dominated the office of mayor of the palace after 687 and eventually supplanted the Merovingians as kings in 751, founding ...

Mayors of the Palace carried out some restoration works, but it was at the time only one residence among others. The Frankish court was itinerant and the rulers moved according to the circumstances. Around 765, Pepin the Short

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of ...

had a palace erected over the remains of the old Roman building; he had the thermae restored and removed its pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

idols.P. Riché, ''La vie quotidienne dans l’Empire carolingien'', p. 57 As soon as he came to power in 768, Charlemagne spent time in Aachen as well as in other villas in Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

. In the 790s, he decided to settle down in order to govern his kingdom, then his empire more efficiently.

The choice of Aachen

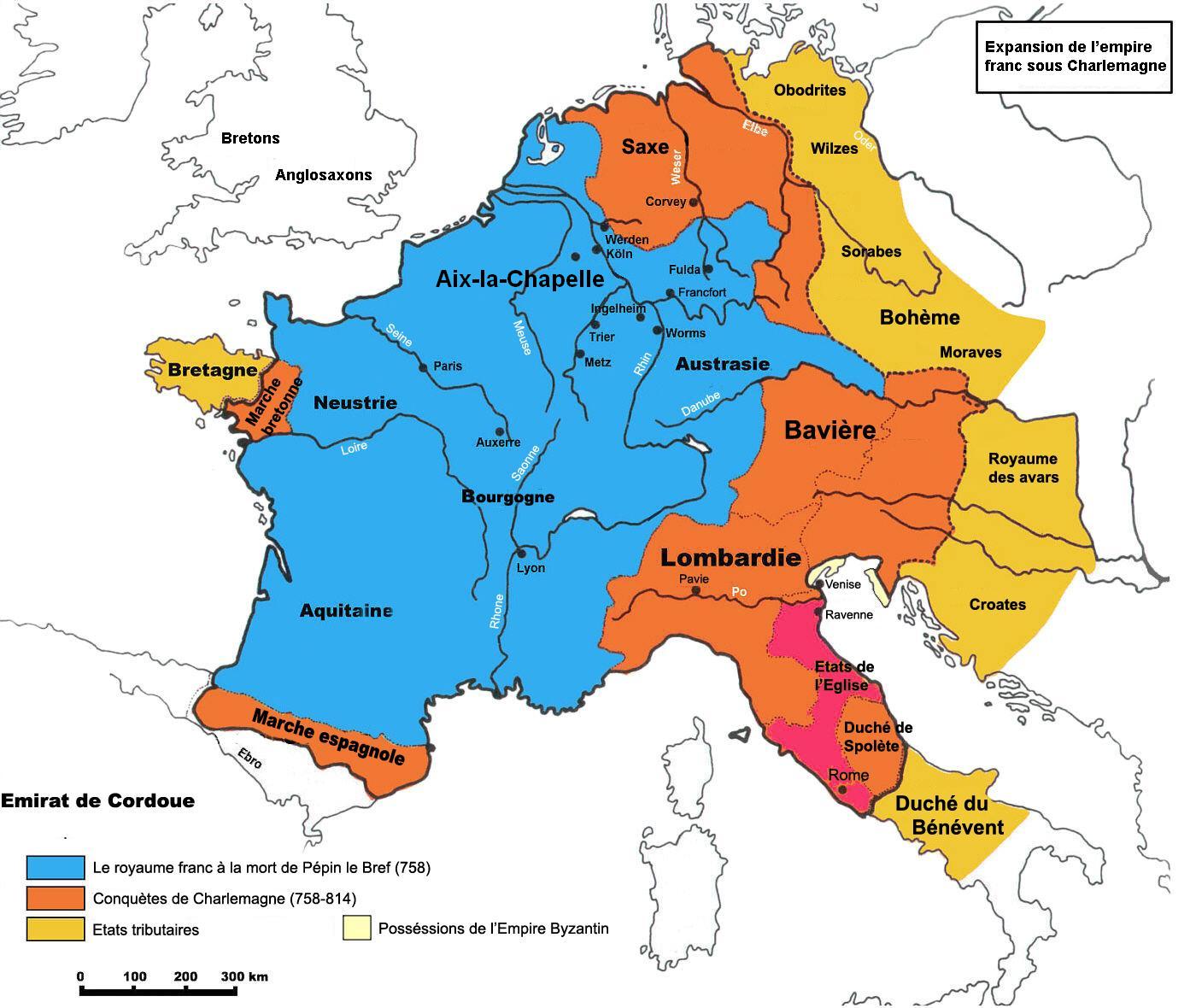

The site of Aachen was chosen by Charlemagne after careful consideration in a key moment of his reign. Since his advent as King of the Franks, Charlemagne had led numerous military expeditions that had both filled his treasury and enlarged his realm, most notably towards the East. He conquered

The site of Aachen was chosen by Charlemagne after careful consideration in a key moment of his reign. Since his advent as King of the Franks, Charlemagne had led numerous military expeditions that had both filled his treasury and enlarged his realm, most notably towards the East. He conquered pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

Saxony in 772–780, but this area resisted and the war with the Saxons lasted for about thirty years. Charlemagne ended the Germanic custom of an itinerant court moving from place to place and established a real capital. As he was ageing, he decreased the frequency of military expeditions and, after 806, virtually did not leave Aachen.

Aachen's geographic location was a decisive factor in Charlemagne's choice: the place was situated in the Carolingian heartlands of Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

, the cradle of his family, East of the Meuse river, at a crossroads of land roads and on a tributary of the Rur

The Rur or Roer (german: Rur ; Dutch and li, Roer, , ; french: Rour) is a major river that flows through portions of Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. It is a right (eastern) tributary to the Meuse ( nl, links=no, Maas). About 90 perce ...

, called the Wurm. From then, Charlemagne left the administration of the Southern regions to his son Louis Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis (d ...

, named King of Aquitaine, which enabled him to reside in the North.

hunting

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

in the area. G. Démians d’Archimbaud, ''Histoire artistique de l’Occident médiéval'', 1992, p. 76 The ageing emperor could also benefit from Aachen's hot springs.

The scholars of the Carolingian era presented Charlemagne as the "New Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

* Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given na ...

"; in this context, he needed a capital and a palace worthy of the name.P. Riché, ''Les Carolingiens. Une famille qui fit l’Europe'', 1983, p. 326 He left Rome to the Pope. The rivalry with the Byzantine Empire led Charlemagne to build a magnificent palace. The fire that destroyed his palace in Worms in 793 also encouraged him to follow such a plan.

Importance of the project entrusted to Odo of Metz

Historians know almost nothing about the architect of the Palace of Aachen, Odo of Metz. His name appears in the works of Eginhard (c. 775–840), Charlemagne's biographer. He is supposed to have been an educated cleric, familiar with liberal arts, especially ''

Historians know almost nothing about the architect of the Palace of Aachen, Odo of Metz. His name appears in the works of Eginhard (c. 775–840), Charlemagne's biographer. He is supposed to have been an educated cleric, familiar with liberal arts, especially ''quadrivia

From the time of Plato through the Middle Ages, the ''quadrivium'' (plural: quadrivia) was a grouping of four subjects or arts—arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy—that formed a second curricular stage following preparatory work in the ...

''. He had probably read Vitruvius' treatise on architecture, ''De Architectura

(''On architecture'', published as ''Ten Books on Architecture'') is a treatise on architecture written by the Roman architect and military engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio and dedicated to his patron, the emperor Caesar Augustus, as a guide f ...

''.

The decision to build the palace was taken in the late 780s or the early 790s, before Charlemagne held the title of emperor. Works began in 794 and went on for several years. Aachen quickly became the favourite residence of the sovereign. After 807, he almost did not leave it any more. In the absence of sufficient documentation, it is impossible to know the number of workers employed, but the dimensions of the building make it probable that there were many of them.

The geometry of the plan chosen was very simple: Odo of Metz decided to keep the layout of the Roman roads and inscribe the square in 360 Carolingian feet, or 120 metres-side square.A. Erlande-Brandeburg, A.-B. Erlande-Brandeburg, ''Histoire de l’architecture française'', 1999, p. 103 The square enclosed an area of 50 acres divided in four parts by a North-South axis (the stone gallery) and an East-West axis (the former Roman road

Roman roads ( la, viae Romanae ; singular: ; meaning "Roman way") were physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, and were built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman Re ...

, the decumanus

In Roman urban planning, a decumanus was an east–west-oriented road in a Roman city or castrum (military camp). The main decumanus of a particular city was the Decumanus Maximus, or most often simply "the Decumanus". In the rectangular street gr ...

). To the north of this square lay the council hall, to the south the Palatine Chapel. The architect drew a triangle toward the East to connect the thermae to the palace complex. The two best-known buildings are the council hall (today disappeared) and the Palatine Chapel, included into the Cathedral. The other buildings are hardly identified.Régine Le Jan, ''La société du Haut Moyen Âge, VIe – IXe siècle'', Paris, Armand Colin, 2003, , p. 120 Often built in timber framing, made of wood and brick

A brick is a type of block used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term ''brick'' denotes a block composed of dried clay, but is now also used informally to denote other chemically cured cons ...

, they have been destroyed. Lastly, the palace complex was surrounded with a wall.P. Riché, ''La vie quotidienne dans l’Empire carolingien'', p. 58

The arrival of the court in Aachen and the construction work stimulated the activity in the city that experienced growth in the late 8th century and the early 9th century, as craftsmen, traders and shopkeepers had settled near the court. Some important ones lived in houses inside the city. The members of the Palace Academy and Charlemagne's advisors such as Eginhard and Angilbert owned houses near the palace.

Council Hall

Carolingian

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippin ...

Empire, dignitaries and the hierarchy of the power: counts

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility.L. G. Pine, Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty'' ...

, vassals of the king, bishops

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

and abbots. The general assembly was usually held in May. Participants discussed important political and legal affairs. Capitularies

A capitulary (Medieval Latin ) was a series of legislative or administrative acts emanating from the Frankish court of the Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties, especially that of Charlemagne, the first emperor of the Romans in the west since the ...

, written by amanuenses

An amanuensis () is a person employed to write or type what another dictates or to copy what has been written by another, and also refers to a person who signs a document on behalf of another under the latter's authority. In one example Eric Fenby ...

of the Aachen chancellery, summed up the decisions taken. In this building also took place official ceremonies and the reception of embassies. Describing the coronation of Louis, son of Charlemagne, Ermold the Black

Ermoldus Nigellus, or Niger—translated Ermold the Black, or Ermoald (), was a poet who lived at the court of Pippin of Aquitaine, son of Frankish Emperor Louis I, and accompanied him on a campaign into Brittany in 824. Ermoldus was a cultured ...

states that there Charlemagne "spoke down from his golden seat."

Palatine Chapel

Description

The Palatine Chapel was located at the other side of the palace complex, at the South. A stone gallery linked it to the ''aula regia''. It symbolized another aspect of Charlemagne's power, religious power. Legend has it that the building was consecrated in 805 by

The Palatine Chapel was located at the other side of the palace complex, at the South. A stone gallery linked it to the ''aula regia''. It symbolized another aspect of Charlemagne's power, religious power. Legend has it that the building was consecrated in 805 by Pope Leo III

Pope Leo III (died 12 June 816) was bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death. Protected by Charlemagne from the supporters of his predecessor, Adrian I, Leo subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position b ...

, in honour of the Virgin Mary, Mother of Christ.

Several buildings used by the clerics of the chapel were arranged in the shape of a latin cross: a curia in the East, offices in the North and South, and a projecting part (''Westbau'') and an atrium with exedrae

An exedra (plural: exedras or exedrae) is a semicircular architectural recess or platform, sometimes crowned by a semi-dome, and either set into a building's façade or free-standing. The original Greek sense (''ἐξέδρα'', a seat out of d ...

in the West. But the center piece was the chapel, covered with a 16,54 meters wide and 31 meters high octagonal cupola. Eight massive pillars receive the thrust of large arcades. The nave on the first floor, located under the cupola, is surrounded by an aisle; here stood the Palace servants.

The two additional floors (tribunes

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs acted as a check on the ...

) open on the central space through semicircular arches supported by columns. The inner side takes the shape of an octagon

In geometry, an octagon (from the Greek ὀκτάγωνον ''oktágōnon'', "eight angles") is an eight-sided polygon or 8-gon.

A '' regular octagon'' has Schläfli symbol and can also be constructed as a quasiregular truncated square, t, whi ...

whereas the outer side develops into a sixteen-sided polygon. The chapel had two choirs

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which sp ...

located in the East and West. The king sat on a throne made of white marble plates, in the West of the second floor, surrounded by his closer courtiers. Thus he had a view on the three altars: that of the Savior

Savior or Saviour may refer to:

*A person who helps people achieve salvation, or saves them from something

Religion

* Mahdi, the prophesied redeemer of Islam who will rule for seven, nine or nineteen years

* Maitreya

* Messiah, a saviour or li ...

right in front of him, that of the Virgin Mary on the first floor and that of Saint Peter in the far end of the Western choir.

Charlemagne wanted his chapel to be magnificently decorated, so he had massive bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

doors made in a foundry near Aachen. The walls were covered with marble and polychrome stone. The columns, still visible today, were taken from buildings in Ravenna and Rome, with the Pope's permission.

The walls and cupola were covered with mosaic, enhanced by both artificial lights and exterior light coming in through the windows. Eginhard provides a description of the inside in his ''Life of Charlemagne'' (c. 825–826):

Symbolism

Odo of Metz applied theChristian symbolism

Christian symbolism is the use of symbols, including archetypes, acts, artwork or events, by Christianity. It invests objects or actions with an inner meaning expressing Christian ideas.

The symbolism of the early Church was characterized by bei ...

for figures and numbers. The building was conceived as a representation of the heavenly Jerusalem

In the Book of Ezekiel in the Hebrew Bible, New Jerusalem (, ''YHWH šāmmā'', YHWH sthere") is Ezekiel's prophetic vision of a city centered on the rebuilt Holy Temple, the Third Temple, to be established in Jerusalem, which would be the ca ...

, the Kingdom of God, as described in the ''Apocalypse

Apocalypse () is a literary genre in which a supernatural being reveals cosmic mysteries or the future to a human intermediary. The means of mediation include dreams, visions and heavenly journeys, and they typically feature symbolic imager ...

''. The outer perimeter of the cupola measures exactly 144 Carolingian feet whereas that of the heavenly Jerusalem, ideal city drawn by angels, is of 144 cubits. The mosaic of the cupola, hidden today behind a 19th-century restoration, showed Christ in Majesty with the 24 elders of the Apocalypse. Other mosaics, on the vaults of the aisle, takes up this subject by representing the heavenly Jerusalem. Charlemagne's throne, located in the West of the second floor, was placed on the seventh step of a platform.

Other buildings

Treasury and archives

The treasury and archives of the palace were located in a tower tied to the great hall, in the North of the complex. The chamberman was the officer liable for the rulers' treasury and wardrobe. Finance administration fell on the archichaplain, assisted by a treasurer. The treasury gathered gifts brought by the kingdom's important people during the general assemblies or by foreign envoys. This made up an heterogeneous collection of objects ranging from precious books to weapons and clothing. The king would also buy items from merchants visiting Aachen. Thechancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

was liable for the archives. The chancellery employed several scribes and notaries who wrote down diplomas, capitularies

A capitulary (Medieval Latin ) was a series of legislative or administrative acts emanating from the Frankish court of the Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties, especially that of Charlemagne, the first emperor of the Romans in the west since the ...

and royal correspondence. Agents of the king's offices were mostly clergymen of the chapel.

Gallery

count of the Palace

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

. The building was also probably used as a garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mil ...

.

Thermae

swimming pool

A swimming pool, swimming bath, wading pool, paddling pool, or simply pool, is a structure designed to hold water to enable Human swimming, swimming or other leisure activities. Pools can be built into the ground (in-ground pools) or built ...

that could accommodate one hundred swimmers at a time:

Other buildings for other functions

The other buildings are not easy to identify because of the lack of detailed enough written accounts. Charlemagne's and his family's apartments seem to have been located in the north-eastern part of the palace complex; his room may have been on the second floor. Some of the servants of the palace must have lived in the western part, and some in the city. The Emperor is said to have owned a library but its exact location is hard to assess. The palace also housed other areas dedicated to artistic creation: a scriptorium that saw the writing of several precious manuscripts ('' Drogo Sacramentary'', '' Godescalc Evangelistary''…), a goldsmith workshop and an ivory workshop. There was also a mint that was still operational in the 13th century.

The palace also housed the literary activities of the Palace Academy. This circle of scholars did not gather in a definite building: Charlemagne liked to listen to poems while he was swimming and eating. The Palace school provided education to the ruler's children and the "nourished ones" (''nutriti'' in Latin), aristocrat sons that were to serve the king.

Outside of the palace complex were also a gynaeceum,

The other buildings are not easy to identify because of the lack of detailed enough written accounts. Charlemagne's and his family's apartments seem to have been located in the north-eastern part of the palace complex; his room may have been on the second floor. Some of the servants of the palace must have lived in the western part, and some in the city. The Emperor is said to have owned a library but its exact location is hard to assess. The palace also housed other areas dedicated to artistic creation: a scriptorium that saw the writing of several precious manuscripts ('' Drogo Sacramentary'', '' Godescalc Evangelistary''…), a goldsmith workshop and an ivory workshop. There was also a mint that was still operational in the 13th century.

The palace also housed the literary activities of the Palace Academy. This circle of scholars did not gather in a definite building: Charlemagne liked to listen to poems while he was swimming and eating. The Palace school provided education to the ruler's children and the "nourished ones" (''nutriti'' in Latin), aristocrat sons that were to serve the king.

Outside of the palace complex were also a gynaeceum, barracks

Barracks are usually a group of long buildings built to house military personnel or laborers. The English word originates from the 17th century via French and Italian from an old Spanish word "barraca" ("soldier's tent"), but today barracks are u ...

, a hospice

Hospice care is a type of health care that focuses on the palliation of a terminally ill patient's pain and symptoms and attending to their emotional and spiritual needs at the end of life. Hospice care prioritizes comfort and quality of life by ...

, a hunting park and a menagerie

A menagerie is a collection of captive animals, frequently exotic, kept for display; or the place where such a collection is kept, a precursor to the modern Zoo, zoological garden.

The term was first used in 17th-century France, in reference to ...

in which lived the elephant Abul-Abbas, given by Baghdad Caliph Harun al-Rashid. Ermoldus Nigellus

Ermoldus Nigellus, or Niger—translated Ermold the Black, or Ermoald (), was a poet who lived at the court of Pippin of Aquitaine, son of Frankish Emperor Louis I, and accompanied him on a campaign into Brittany in 824. Ermoldus was a cultured ma ...

describes the place in his ''Poems on Louis the Pious'' (first half of the 9th century).

The place was frequented everyday by crowds of people: courtiers, scholars, aristocrats, merchants but also beggars and poor people that came to ask for charity. Internal affairs were the task of officers such as butler

A butler is a person who works in a house serving and is a domestic worker in a large household. In great houses, the household is sometimes divided into departments with the butler in charge of the dining room, wine cellar, and pantry. Some a ...

, le seneschal

The word ''seneschal'' () can have several different meanings, all of which reflect certain types of supervising or administering in a historic context. Most commonly, a seneschal was a senior position filled by a court appointment within a royal, ...

, the chamberman.

Symbolic interpretation of the Palace

Roman legacy and Byzantine model

The palace borrows several elements of Roman civilization. The ''Aula Palatina'' follows a basilical plan. Basilicas in ancient times were public buildings where the city's affairs were discussed. The chapel follows models from ancient Rome: grids exhibit antique decorations ( acanthus) and columns are topped by

The palace borrows several elements of Roman civilization. The ''Aula Palatina'' follows a basilical plan. Basilicas in ancient times were public buildings where the city's affairs were discussed. The chapel follows models from ancient Rome: grids exhibit antique decorations ( acanthus) and columns are topped by Corinthian capitals

The Corinthian order (Greek: Κορινθιακός ρυθμός, Latin: ''Ordo Corinthius'') is the last developed of the three principal classical orders of Ancient Greek architecture and Roman architecture. The other two are the Doric order w ...

. The Emperor was buried in the Palatine Chapel within a 2nd-century marble sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (plural sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Greek ...

decorated with a depiction of the abduction of Proserpina. Scholars of Charlemagne's time nicknamed Aachen «the Second Rome».

Charlemagne wished to compete with another Emperor of his time: Basileus of Constantinople. The cupola and mosaics of the chapel are Byzantine elements. The plan itself is inspired by the Basilica of San Vitale

The Basilica of San Vitale is a late antique church in Ravenna, Italy. The sixth-century church is an important surviving example of early Christian Byzantine art and architecture. It is one of eight structures in Ravenna inscribed on the UNESCO ...

in Ravenna, built by Justinian I in the 6th century. Other experts point to similarities with the Church of the Saints Sergius and Bacchus, Constantinople's Chrysotriklinos and the main throne room in the Great Palace of Constantinople. During religious offices, Charlemagne stood in the second floor gallery, as did the Emperor in Constantinople.

Odo of Metz was also likely inspired by the 8th-century Lombard Palace of Pavia where the chapel was decorated with mosaics and paintings. Although he may have travelled to Italy, it is unlikely that he visited Constantinople.

Frankish style

Although many references to Roman and Byzantine models are visible in Aachen's buildings, Odo of Metz expressed his talent for Frankish architect and brought undeniably different elements. The palace is also distinguishable from Merovingian architecture by its large scale and the multiplicity of volumes. The vaulting of the chapel illustrates an original Carolingian expertise, especially in the ambulatory topped with a groin vault. Whereas Byzantine emperors sat in the east to watch offices, Charlemagne sat in the west. Lastly, wooden buildings and half-timbering techniques were typical of Northern Europe. Charlemagne's palace was thus more than a copy of Classical and Byzantine models: it was rather a synthesis of various influences, as a reflection of the Carolingian Empire. Just likeCarolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. It occurred from the late 8th century to the 9th century, taking inspiration from the State church of the Roman Emp ...

, the palace was a product of the assimilation of several cultures and legacies.

Imperial centralization and unity

The layout of the palatine complex perfectly implemented the alliance between two powers: the spiritual power was represented by the chapel in the South and the temporal power by the Council Hall in the North. Both of these were linked by the gallery. SincePepin the Short

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of ...

, Charlemagne's father, Carolingian kings were sacred and received their power from God. Charlemagne himself wanted to influence religious matters through his reforms and the numerous ecumenical council and synods

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word '' synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin word mea ...

held in Aachen. By establishing the seat of the power and the court in Aachen, Charlemagne knew he would be able to more easily supervise those close to him. The palace was the heart of the capital city, gathering dignitaries from all over the Empire.

After Charlemagne

Model for other palaces?

cathedrals

A cathedral is a church that contains the '' cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denomination ...

, 232 monasteries and 65 royal palaces were built between 768 and 814.

The Palatine Chapel of Aachen seems to have been imitated by several other buildings of the same kind: The octagonal oratory of Germigny-des-Prés

Germigny-des-Prés () is a commune in the Loiret department in north-central France.

The Oratory

The oratory at Germigny-des-Prés (Loiret, Orléanais) was built by Bishop Theodulf of Orléans in 806 as part of his palace complex within the Gal ...

, built in the early 9th century for Theodulf of Orléans seems to have been directly related. The Collegiate church of Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far from b ...

was built in the 10th century following the plan of the palatine chapel. Ottmarsheim

Ottmarsheim (; gsw-FR, Ottmersche) is a commune in the Haut-Rhin department in Alsace in north-eastern France. It lies on the river Rhine and on the A36 autoroute, 14 km east of Mulhouse. Its octagonal parish church was the church of the forme ...

church in Alsace also adopts a centered plan but was built later (11th century). The influence of Aachen's chapel is also found in Compiègne and in other German religious buildings (such as the Abbey church of Essen

Essen (; Latin: ''Assindia'') is the central and, after Dortmund, second-largest city of the Ruhr, the largest urban area in Germany. Its population of makes it the fourth-largest city of North Rhine-Westphalia after Cologne, Düsseldorf and D ...

).

Palace history after Charlemagne

Charlemagne was buried in the chapel in 814. His son and successor, Emperor Louis the Pious, used the palace of Aachen without making it his exclusive residence. He used to stay there from winter until Easter. Several importantCouncils

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

were held in Aix in the early 9th century. Those of 817 and 836 took place in the buildings adjacent to the chapel. In 817, Louis the Pious had his elder son Lothair in the presence of the Frankish people.

Following the Treaty of Verdun in 843, the Carolingian Empire was split into three kingdoms. Aachen was then incorporated into Middle Francia. Lothair I

Lothair I or Lothar I (Dutch and Medieval Latin: ''Lotharius''; German: ''Lothar''; French: ''Lothaire''; Italian: ''Lotario'') (795 – 29 September 855) was emperor (817–855, co-ruling with his father until 840), and the governor of Bavar ...

(840–855) and Lothair II

Lothair II (835 – 8 August 869) was the king of Lotharingia from 855 until his death. He was the second son of Emperor Lothair I and Ermengarde of Tours. He was married to Teutberga (died 875), daughter of Boso the Elder.

Reign

For political ...

(855–869) lived in the palace. When he died, the palace lost its political and cultural significance. Lotharingia became a field of rivalry between the kings of West and East Francia

East Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's Carolingian Empire, empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided t ...

. It was split several times and finally fell under the control of Germany under Henry I the Fowler

Henry the Fowler (german: Heinrich der Vogler or '; la, Henricus Auceps) (c. 876 – 2 July 936) was the Duke of Saxony from 912 and the King of East Francia from 919 until his death in 936. As the first non- Frankish king of East Francia, he ...

(876–936).

Yet the memory of Charlemagne's Empire remained fresh and became a symbol of German power. In the 10th century, Otto I (912–973) was crowned King of Germany in Aachen (936). The three-part ceremony took place in several locations within the palace: first in the courtyard (election by the dukes), then in the chapel (handing of the insignia of the Kingdom), finally in the palace (banquet). During the ceremony, Otto sat on Charlemagne's throne. Afterwards, and until the 16th century, all the German Emperors were crowned firstly in Aachen and then in Rome, which highlights the attachment to Charlemagne's political legacy. The Golden Bull of 1356 confirmed that coronations were to take place in the palatine chapel.

Otto II (955–983) lived in Aachen with his wife Theophanu. In the summer of 978 Lothair of France led a raid on Aachen but the Imperial family avoided capture. Relating these events, Richer of Reims states the existence of a bronze eagle, the exact location of which is unknown:

Yet the memory of Charlemagne's Empire remained fresh and became a symbol of German power. In the 10th century, Otto I (912–973) was crowned King of Germany in Aachen (936). The three-part ceremony took place in several locations within the palace: first in the courtyard (election by the dukes), then in the chapel (handing of the insignia of the Kingdom), finally in the palace (banquet). During the ceremony, Otto sat on Charlemagne's throne. Afterwards, and until the 16th century, all the German Emperors were crowned firstly in Aachen and then in Rome, which highlights the attachment to Charlemagne's political legacy. The Golden Bull of 1356 confirmed that coronations were to take place in the palatine chapel.

Otto II (955–983) lived in Aachen with his wife Theophanu. In the summer of 978 Lothair of France led a raid on Aachen but the Imperial family avoided capture. Relating these events, Richer of Reims states the existence of a bronze eagle, the exact location of which is unknown:

In 881, a Viking raid damaged the palace and the chapel. In 1000, the Holy Roman Emperor

In 881, a Viking raid damaged the palace and the chapel. In 1000, the Holy Roman Emperor Otto III

Otto III (June/July 980 – 23 January 1002) was Holy Roman Emperor from 996 until his death in 1002. A member of the Ottonian dynasty, Otto III was the only son of the Emperor Otto II and his wife Theophanu.

Otto III was crowned as King of ...

had Charlemagne's tomb opened. According to two 11th-century chroniclers, he would have been found sitting on his throne, wearing his crown and holding his sceptre. However, Eginhard does not mention this in his biography of the Emperor. At the same time the veneration of Charlemagne began to attract pilgrims to the chapel. In the 12th century, Frederick Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (german: link=no, Friedrich I, it, Federico I), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death 35 years later. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt on ...

placed the body of the Carolingian Emperor into a reliquary

A reliquary (also referred to as a ''shrine'', by the French term ''châsse'', and historically including ''wikt:phylactery, phylacteries'') is a container for relics. A portable reliquary may be called a ''fereter'', and a chapel in which it i ...

and interceded with the Pope for his canonization

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of ...

; the relics were scattered across the empire. The treasure of Aachen began to grow with numerous gifts from French and German kings and princes.

Between 1355 and 1414, an apse was added to the east end of the chapel. The City Hall was built from 1267 on the site of the Council Hall. During the French Revolution, the French occupied Aachen and looted its treasure. Before choosing Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame de Paris (; meaning "Our Lady of Paris"), referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the Seine River), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris. The cathedral, dedicated to the ...

, Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

had considered for a time holding his Imperial Coronation in Aachen.J. Favier, ''Charlemagne'', 1999, p. 691 The chapel was restored in 1884. In 1978 the cathedral, including the chapel, was listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

See also

*Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

* Carolingian art

Carolingian art comes from the Frankish Empire in the period of roughly 120 years from about 780 to 900—during the reign of Charlemagne and his immediate heirs—popularly known as the Carolingian Renaissance. The art was produced by and for the ...

* Carolingian Empire

* Palatine Chapel in Aachen

Notes

References

* Alain Erlande-Brandeburg, Anne-Bénédicte Erlande-Brandeburg, ''Histoire de l’architecture française, tome 1 : du Moyen Âge à la Renaissance, IVe – XVIe siècle'', 1999, Paris, éditions du Patrimoine, . * Gabrielle Démians D’Archimbaud, ''Histoire artistique de l’Occident médiéval'', Paris, Colin, 3e édition, 1968, 1992, . * Marcel Durliat, ''Des barbares à l’an Mil'', Paris, éditions citadelles et Mazenod, 1985, . * Jean Favier, ''Charlemagne'', Paris, Fayard, 1999, . * Jean Hubert, Jean Porcher, W. F. Volbach, ''L’empire carolingien'', Paris, Gallimard, 1968 * Félix Kreush, « La Chapelle palatine de Charlemagne à Aix », dans '' Les Dossiers d'archéologie'', n°30, 1978, pages 14–23. * Pierre Riché, ''La Vie quotidienne dans l’Empire carolingien'', Paris, Hachette, 1973 * Pierre Riché, ''Les Carolingiens. Une famille qui fit l’Europe'', Paris, Hachette, 1983, .External links

*Aachen cathedral in pictures

{{DEFAULTSORT:Palace Of Aachen Buildings and structures completed in the 8th century Palaces in North Rhine-Westphalia Carolingian architecture Charlemagne

Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

Landmarks in Germany

History of Aachen

Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

Articles containing video clips