Painted hunting dog on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The African wild dog (''Lycaon pictus''), also called the painted dog or Cape hunting dog, is a wild canine which is a

Dogs

', W.H. Lizars, Edinburgh, p. 261–69 The African wild dog was first described scientifically in 1820 by

The African wild dog possesses the most specialized adaptations among the canids for coat colour, diet, and for pursuing its prey through its

The African wild dog possesses the most specialized adaptations among the canids for coat colour, diet, and for pursuing its prey through its

In 2018,

In 2018,

The African wild dog is the bulkiest and most solidly built of African canids.Rosevear, D. R. (1974).

The African wild dog is the bulkiest and most solidly built of African canids.Rosevear, D. R. (1974).

The carnivores of West Africa

'. London : Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). pp. 75–91. . The species stands in shoulder height, measures in head-and-body length and has a tail length of . Body weight of adults range from . On average, dogs from East Africa weigh around while in southern Africa, males reportedly weighed a mean of and females a mean of . By body mass, they are only outsized amongst other extant canids by the The fur of the African wild dog differs significantly from that of other canids, consisting entirely of stiff bristle-hairs with no underfur. It gradually loses its fur as it ages, with older individuals being almost naked. Colour variation is extreme, and may serve in visual identification, as African wild dogs can recognise each other at distances of . Some geographic variation is seen in coat colour, with northeastern African specimens tending to be predominantly black with small white and yellow patches, while southern African ones are more brightly coloured, sporting a mix of brown, black and white coats. Much of the species' coat patterning occurs on the trunk and legs. Little variation in facial markings occurs, with the muzzle being black, gradually shading into brown on the cheeks and forehead. A black line extends up the forehead, turning blackish-brown on the back of the ears. A few specimens sport a brown teardrop-shaped mark below the eyes. The back of the head and neck are either brown or yellow. A white patch occasionally occurs behind the fore legs, with some specimens having completely white fore legs, chests and throats. The tail is usually white at the tip, black in the middle and brown at the base. Some specimens lack the white tip entirely, or may have black fur below the white tip. These coat patterns can be asymmetrical, with the left side of the body often having different markings from that of the right.

The fur of the African wild dog differs significantly from that of other canids, consisting entirely of stiff bristle-hairs with no underfur. It gradually loses its fur as it ages, with older individuals being almost naked. Colour variation is extreme, and may serve in visual identification, as African wild dogs can recognise each other at distances of . Some geographic variation is seen in coat colour, with northeastern African specimens tending to be predominantly black with small white and yellow patches, while southern African ones are more brightly coloured, sporting a mix of brown, black and white coats. Much of the species' coat patterning occurs on the trunk and legs. Little variation in facial markings occurs, with the muzzle being black, gradually shading into brown on the cheeks and forehead. A black line extends up the forehead, turning blackish-brown on the back of the ears. A few specimens sport a brown teardrop-shaped mark below the eyes. The back of the head and neck are either brown or yellow. A white patch occasionally occurs behind the fore legs, with some specimens having completely white fore legs, chests and throats. The tail is usually white at the tip, black in the middle and brown at the base. Some specimens lack the white tip entirely, or may have black fur below the white tip. These coat patterns can be asymmetrical, with the left side of the body often having different markings from that of the right.

The African wild dog has very strong social bonds, stronger than those of sympatric lions and

The African wild dog has very strong social bonds, stronger than those of sympatric lions and

A species-wide study showed that by preference, where available, five species were the most regularly selected prey, namely the

A species-wide study showed that by preference, where available, five species were the most regularly selected prey, namely the

Artistic depictions of African wild dogs are prominent on

Artistic depictions of African wild dogs are prominent on

native species

In biogeography, a native species is indigenous to a given region or ecosystem if its presence in that region is the result of only local natural evolution (though often popularised as "with no human intervention") during history. The term is equ ...

to sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

. It is the largest wild canine in Africa, and the only extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

member of the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

'' Lycaon'', which is distinguished from ''Canis

''Canis'' is a genus of the Caninae which includes multiple extant species, such as wolves, dogs, coyotes, and golden jackals. Species of this genus are distinguished by their moderate to large size, their massive, well-developed skulls and den ...

'' by dentition highly specialised for a hypercarnivorous

A hypercarnivore is an animal which has a diet that is more than 70% meat, either via active predation or by scavenging. The remaining non-meat diet may consist of non-animal foods such as fungi, fruits or other plant material. Some extant exampl ...

diet, and by a lack of dewclaw

A dewclaw is a digit – vestigial in some animals – on the foot of many mammals, birds, and reptiles (including some extinct orders, like certain theropods). It commonly grows higher on the leg than the rest of the foot, such that in digit ...

s. It is estimated that about 6,600 adults (including 1,400 mature individuals) live in 39 subpopulations that are all threatened by habitat fragmentation

Habitat fragmentation describes the emergence of discontinuities (fragmentation) in an organism's preferred environment (habitat), causing population fragmentation and ecosystem decay. Causes of habitat fragmentation include geological processes ...

, human persecution, and outbreaks of disease. As the largest subpopulation probably comprises fewer than 250 individuals, the African wild dog has been listed as endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and inva ...

on the IUCN Red List

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is the world's most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biol ...

since 1990.

The species is a specialised diurnal hunter of antelope

The term antelope is used to refer to many species of even-toed ruminant that are indigenous to various regions in Africa and Eurasia.

Antelope comprise a wastebasket taxon defined as any of numerous Old World grazing and browsing hoofed mammals ...

s, which it catches by chasing them to exhaustion. Its natural enemies are lion

The lion (''Panthera leo'') is a large Felidae, cat of the genus ''Panthera'' native to Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body; short, rounded head; round ears; and a hairy tuft at the end of its tail. It is sexually dimorphi ...

s and spotted hyena

The spotted hyena (''Crocuta crocuta''), also known as the laughing hyena, is a hyena species, currently classed as the sole extant member of the genus ''Crocuta'', native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is listed as being of least concern by the IUC ...

s: the former will kill the dogs where possible, whilst hyenas are frequent kleptoparasite

Kleptoparasitism (etymologically, parasitism by theft) is a form of feeding in which one animal deliberately takes food from another. The strategy is evolutionarily stable when stealing is less costly than direct feeding, which can mean when fo ...

s.

Like other canids, the African wild dog regurgitates food for its young, but also extends this action to adults, as a central part of the pack's social life. The young are allowed to feed first on carcasses.

The African wild dog has been respected in several hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

societies, particularly those of the San people

The San peoples (also Saan), or Bushmen, are members of various Khoe, Tuu, or Kxʼa-speaking indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures that are the first cultures of Southern Africa, and whose territories span Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia, ...

and Prehistoric Egypt

Prehistoric Egypt and Predynastic Egypt span the period from the earliest human settlement to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period around 3100 BC, starting with the first Pharaoh, Narmer for some Egyptologists, Hor-Aha for others, with th ...

.

Naming

The English language has several names for the African wild dog, including African hunting dog, Cape hunting dog, painted hunting dog, painted dog, and painted lycaon. One conservation organisation is promoting the name 'painted wolf' as a way of rebranding the species, as wild dog has several negative connotations that could be detrimental to its image. Nevertheless, the name "African wild dog" is still widely used, However, the name "painted dog" was found to be the most likely to counteract negative perceptions of the species.Taxonomic and evolutionary history

Taxonomy

The earliest written reference to the species appears to be fromOppian

Oppian ( grc, Ὀππιανός, ; la, Oppianus), also known as Oppian of Anazarbus, of Corycus, or of Cilicia, was a 2nd-century Greco-Roman poet during the reign of the emperors Marcus Aurelius and Commodus, who composed the ''Halieutica'', a fi ...

, who wrote of the ''thoa'', a hybrid between the wolf and leopard, which resembles the former in shape and the latter in colour. Solinus's ''Collea rerum memorabilium'' from the third century AD describes a multicoloured wolf-like animal with a mane native to Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

.Smith, C. H. (1839). Dogs

', W.H. Lizars, Edinburgh, p. 261–69 The African wild dog was first described scientifically in 1820 by

Coenraad Jacob Temminck

Coenraad Jacob Temminck (; 31 March 1778 – 30 January 1858) was a Dutch people, Dutch Aristocracy (class), aristocrat, Zoology, zoologist and museum director.

Biography

Coenraad Jacob Temminck was born on 31 March 1778 in Amsterdam in the Dut ...

, after examining a specimen from the coast of Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

. He named the animal ''Hyaena picta'', erroneously classifying it as a species of hyena. It was later recognised as a canid

Canidae (; from Latin, ''canis'', "dog") is a biological family of dog-like carnivorans, colloquially referred to as dogs, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a canid (). There are three subfamilies found within the ...

by Joshua Brookes

Joshua Brookes (24 November 1761 – 10 January 1833) was a British anatomist and naturalist.

Early life

Brookes studied under William Hunter, William Hewson, Andrew Marshall, and John Sheldon, in London. He then attended the practice of ...

in 1827, and renamed ''Lycaon tricolor''. The root word

A root (or root word) is the core of a word that is irreducible into more meaningful elements. In morphology, a root is a morphologically simple unit which can be left bare or to which a prefix or a suffix can attach. The root word is the prima ...

of ''Lycaon'' is the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

λυκαίος (''lykaios''), meaning "wolf-like". The specific epithet ''pictus'' (Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

for "painted"), which derived from the original ''picta'', was later returned to it, in conformity with the International Rules on Taxonomic Nomenclature.Bothma, J. du P. & Walker, C. (1999). ''Larger Carnivores of the African Savannas'', Springer, pp. 130–157,

Paleontologist George G. Simpson

George Gaylord Simpson (June 16, 1902 – October 6, 1984) was an American paleontologist. Simpson was perhaps the most influential paleontologist of the twentieth century, and a major participant in the modern synthesis, contributing ''Tempo a ...

placed the African wild dog, the dhole

The dhole (''Cuon alpinus''; ) is a canid native to Central, South, East and Southeast Asia. Other English names for the species include Asian wild dog, Asiatic wild dog, Indian wild dog, whistling dog, red dog, red wolf, and mountain wolf. It ...

, and the bush dog

The bush dog (''Speothos venaticus'') is a canine found in Central and South America. In spite of its extensive range, it is very rare in most areas except in Suriname, Guyana and Peru; it was first identified by Peter Wilhelm Lund from fossils ...

together in the subfamily

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus. Standard nomenclature rules end subfamily botanical names with "-oideae", and zoologi ...

Simocyon

''Simocyon'' ("short-snouted dog") is a genus of extinct carnivoran mammal in the family Ailuridae. ''Simocyon'', which was about the size of a mountain lion, lived in the late Miocene and early Pliocene epochs, and has been found in Europe, Asi ...

inae on the basis of all three species having similarly trenchant carnassial

Carnassials are paired upper and lower teeth modified in such a way as to allow enlarged and often self-sharpening edges to pass by each other in a shearing manner. This adaptation is found in carnivorans, where the carnassials are the modified f ...

s. This grouping was disputed by Juliet Clutton-Brock

Juliet Clutton-Brock, FSA, FZS (6 September 1933 – 21 September 2015) was an English zooarchaeologist and curator, specialising in domesticated mammals. From 1969 to 1993, she worked at the Natural History Museum. Between 1999 and 2006, she w ...

, who argued that, other than dentition, too many differences exist between the three species to warrant classifying them in a single subfamily.

Evolution

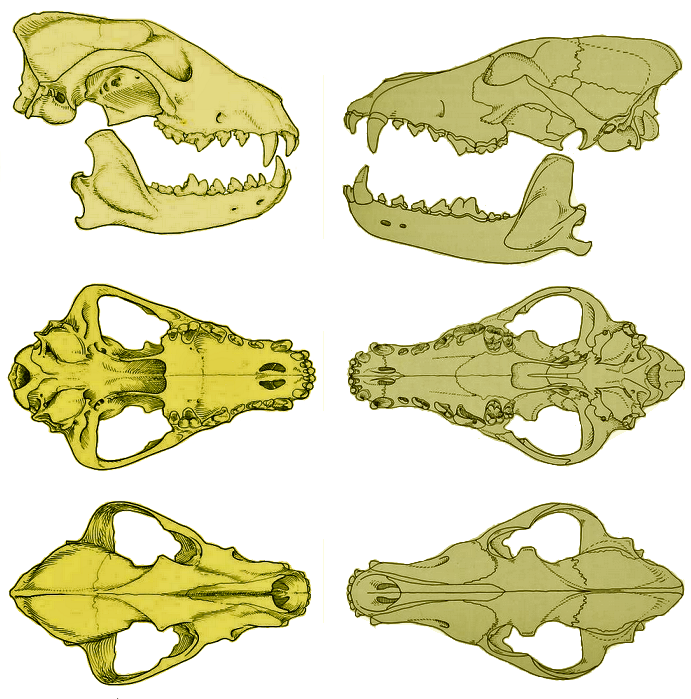

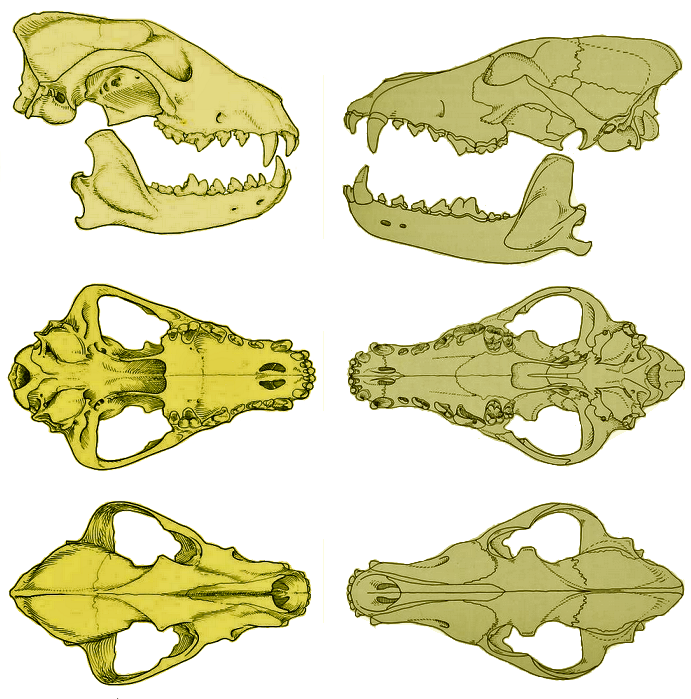

The African wild dog possesses the most specialized adaptations among the canids for coat colour, diet, and for pursuing its prey through its

The African wild dog possesses the most specialized adaptations among the canids for coat colour, diet, and for pursuing its prey through its cursorial

A cursorial organism is one that is adapted specifically to run. An animal can be considered cursorial if it has the ability to run fast (e.g. cheetah) or if it can keep a constant speed for a long distance (high endurance). "Cursorial" is often u ...

(running) ability. It possesses a graceful skeleton, and the loss of the first digit on its forefeet increases its stride and speed. This adaptation allows it to pursue prey across open plains for long distances. The teeth are generally carnassial

Carnassials are paired upper and lower teeth modified in such a way as to allow enlarged and often self-sharpening edges to pass by each other in a shearing manner. This adaptation is found in carnivorans, where the carnassials are the modified f ...

-shaped, and its premolars

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth ...

are the largest relative to body size of any living carnivoran

Carnivora is a monophyletic order of placental mammals consisting of the most recent common ancestor of all cat-like and dog-like animals, and all descendants of that ancestor. Members of this group are formally referred to as carnivorans, ...

except for the spotted hyena

The spotted hyena (''Crocuta crocuta''), also known as the laughing hyena, is a hyena species, currently classed as the sole extant member of the genus ''Crocuta'', native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is listed as being of least concern by the IUC ...

. On the lower carnassials (first lower molars

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone to ...

), the talonid

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone ...

has evolved to become a cutting blade for flesh-slicing, with a reduction or loss of the post-carnassial molars. This adaptation also occurs in two other hypercarnivores – the dhole

The dhole (''Cuon alpinus''; ) is a canid native to Central, South, East and Southeast Asia. Other English names for the species include Asian wild dog, Asiatic wild dog, Indian wild dog, whistling dog, red dog, red wolf, and mountain wolf. It ...

and the bush dog

The bush dog (''Speothos venaticus'') is a canine found in Central and South America. In spite of its extensive range, it is very rare in most areas except in Suriname, Guyana and Peru; it was first identified by Peter Wilhelm Lund from fossils ...

. The African wild dog exhibits one of the most varied coat colours among the mammals. Individuals differ in patterns and colours, indicating a diversity of the underlying genes

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

. The purpose of these coat patterns may be an adaptation for communication, concealment, or temperature regulation. In 2019, a study indicated that the ''lycaon'' lineage diverged from ''Cuon'' and ''Canis'' 1.7 million years ago through this suite of adaptations, and these occurred at the same time as large ungulates

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Ungulata which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. These include odd-toed ungulates such as horses, rhinoceroses, and tapirs; and even-toed ungulates such as cattle, pigs, giraffes, cam ...

(its prey) diversified.

The oldest ''L. pictus'' fossil dates back to 200,000 years ago and was found in HaYonim Cave, Israel. The evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

of the African wild dog is poorly understood due to the scarcity of fossil finds. Some authors consider the extinct ''Canis'' subgenus

In biology, a subgenus (plural: subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.

In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between t ...

''Xenocyon

''Xenocyon'' ("strange dog") is an extinct subgenus of ''Canis''. The group includes ''Canis'' (''Xenocyon'') ''africanus'', ''Canis'' (''Xenocyon'') ''antonii'' and ''Canis'' (''Xenocyon'') ''falconeri'' that gave rise to ''Canis'' (''Xenocyon'' ...

'' as ancestral to both the genus ''Lycaon'' and the genus ''Cuon

The dhole (''Cuon alpinus''; ) is a canid native to Central, South, East and Southeast Asia. Other English names for the species include Asian wild dog, Asiatic wild dog, Indian wild dog, whistling dog, red dog, red wolf, and mountain wolf. It ...

'', which lived throughout Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago a ...

and Africa from the Early Pleistocene

The Early Pleistocene is an unofficial sub-epoch in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, being the earliest division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. It is currently estimated to span the time ...

to the early Middle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, widely known by its previous designation of Middle Pleistocene, is an age in the international geologic timescale or a stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. The ...

. Others propose that ''Xenocyon'' should be reclassified as ''Lycaon''. The species ''Canis'' (''Xenocyon'') ''falconeri'' shared the African wild dog's absent first metacarpal

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus form the intermediate part of the skeletal hand located between the phalanges of the fingers and the carpal bones of the wrist, which forms the connection to the forearm. The metacarpal bones ...

(dewclaw

A dewclaw is a digit – vestigial in some animals – on the foot of many mammals, birds, and reptiles (including some extinct orders, like certain theropods). It commonly grows higher on the leg than the rest of the foot, such that in digit ...

), though its dentition was still relatively unspecialised. This connection was rejected by one author because ''C''. (''X''.) ''falconeri'' lacks metacarpal, which is a poor indication of phylogenetic closeness to the African wild dog, and the dentition was too different to imply ancestry.

Another ancestral candidate is the Plio-Pleistocene

The Plio-Pleistocene is an informally described geological pseudo-period, which begins about 5 million years ago (Mya) and, drawing forward, combines the time ranges of the formally defined Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs—marking from about 5&nbs ...

'' L. sekowei'' of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

on the basis of distinct accessory cusps on its premolar

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth ...

s and anterior accessory cuspids on its lower premolars. These adaptions are found only in ''Lycaon'' among living canids, which shows the same adaptations to a hypercarnivorous diet. ''L. sekowei'' had not yet lost the first metacarpal absent in ''L. pictus'' and was more robust than the modern species, having 10% larger teeth.

The African wild dog genetically diverged from other canid lineage

Lineage may refer to:

Science

* Lineage (anthropology), a group that can demonstrate its common descent from an apical ancestor or a direct line of descent from an ancestor

* Lineage (evolution), a temporal sequence of individuals, populati ...

s between and is thought to be isolated from gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring ( reproduction). ...

with other canid species.

Admixture with the dhole

In 2018,

In 2018, whole genome sequencing

Whole genome sequencing (WGS), also known as full genome sequencing, complete genome sequencing, or entire genome sequencing, is the process of determining the entirety, or nearly the entirety, of the DNA sequence of an organism's genome at a s ...

was used to compare the dhole

The dhole (''Cuon alpinus''; ) is a canid native to Central, South, East and Southeast Asia. Other English names for the species include Asian wild dog, Asiatic wild dog, Indian wild dog, whistling dog, red dog, red wolf, and mountain wolf. It ...

(''Cuon alpinus'') with the African wild dog. There was strong evidence of ancient genetic admixture

Genetic admixture occurs when previously diverged or isolated genetic lineages mix.⅝ Admixture results in the introduction of new genetic lineages into a population.

Examples

Climatic cycles facilitate genetic admixture in cold periods and gene ...

between the two. Today, their ranges are remote from each other; however, during the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

era the dhole could be found as far west as Europe. The study proposes that the dhole's distribution may have once included the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, from where it may have admixed with the African wild dog in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

. However, there is no evidence of the dhole having existed in the Middle East or North Africa.

Subspecies

, five subspecies are recognised byMSW3

''Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference'' is a standard reference work in mammalogy giving descriptions and bibliographic data for the known species of mammals. It is now in its third edition, published in late 2005 ...

:

Nevertheless, although the species is genetically diverse, these subspecific designations are not universally accepted. East African and Southern African wild dog populations were once thought to be genetically distinct, based on a small number of samples. More recent studies with a larger number of samples showed that extensive intermixing has occurred between East African and Southern African populations in the past. Some unique nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

* Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

*Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

and mitochondrial

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is use ...

allele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chro ...

s are found in Southern African and northeastern African populations, with a transition zone encompassing Botswana

Botswana (, ), officially the Republic of Botswana ( tn, Lefatshe la Botswana, label=Setswana, ), is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. Botswana is topographically flat, with approximately 70 percent of its territory being the Kalahar ...

, Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozam ...

and southeastern Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

between the two. The West African wild dog population may possess a unique haplotype

A haplotype ( haploid genotype) is a group of alleles in an organism that are inherited together from a single parent.

Many organisms contain genetic material ( DNA) which is inherited from two parents. Normally these organisms have their DNA or ...

, thus possibly constituting a truly distinct subspecies. The original Serengeti

The Serengeti ( ) ecosystem is a geographical region in Africa, spanning northern Tanzania. The protected area within the region includes approximately of land, including the Serengeti National Park and several game reserves. The Serengeti ...

and Maasai Mara

Maasai Mara, also sometimes spelled Masai Mara and locally known simply as The Mara, is a large national game reserve in Narok, Kenya, contiguous with the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania. It is named in honor of the Maasai people, the ancestr ...

population of painted dogs is known to have possessed a unique genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

s, but these genotypes may be extinct.

Physical description

The African wild dog is the bulkiest and most solidly built of African canids.Rosevear, D. R. (1974).

The African wild dog is the bulkiest and most solidly built of African canids.Rosevear, D. R. (1974). The carnivores of West Africa

'. London : Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). pp. 75–91. . The species stands in shoulder height, measures in head-and-body length and has a tail length of . Body weight of adults range from . On average, dogs from East Africa weigh around while in southern Africa, males reportedly weighed a mean of and females a mean of . By body mass, they are only outsized amongst other extant canids by the

gray wolf

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the gray wolf or grey wolf, is a large canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, and gray wolves, as popularly ...

species complex

In biology, a species complex is a group of closely related organisms that are so similar in appearance and other features that the boundaries between them are often unclear. The taxa in the complex may be able to hybridize readily with each oth ...

.Estes, R. (1992). ''The behavior guide to African mammals: including hoofed mammals, carnivores, primates''. University of California Press. pp. 410–419. . Females are generally 3–7% smaller than males. Compared to members of the genus ''Canis'', the African wild dog is comparatively lean and tall, with outsized ears and lacking dewclaw

A dewclaw is a digit – vestigial in some animals – on the foot of many mammals, birds, and reptiles (including some extinct orders, like certain theropods). It commonly grows higher on the leg than the rest of the foot, such that in digit ...

s. The middle two toepads are usually fused. Its dentition also differs from that of ''Canis'' by the degeneration of the last lower molar, the narrowness of the canines

Canine may refer to:

Zoology and anatomy

* a dog-like Canid animal in the subfamily Caninae

** ''Canis'', a genus including dogs, wolves, coyotes, and jackals

** Dog, the domestic dog

* Canine tooth, in mammalian oral anatomy

People with the surn ...

and proportionately large premolar

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth ...

s, which are the largest relative to body size of any carnivore other than hyenas. The heel of the lower carnassial

Carnassials are paired upper and lower teeth modified in such a way as to allow enlarged and often self-sharpening edges to pass by each other in a shearing manner. This adaptation is found in carnivorans, where the carnassials are the modified f ...

M1 is crested with a single, blade-like cusp, which enhances the shearing capacity of the teeth, thus the speed at which prey can be consumed. This feature, termed "trenchant heel", is shared with two other canids: the Asian dhole

The dhole (''Cuon alpinus''; ) is a canid native to Central, South, East and Southeast Asia. Other English names for the species include Asian wild dog, Asiatic wild dog, Indian wild dog, whistling dog, red dog, red wolf, and mountain wolf. It ...

and the South American bush dog

The bush dog (''Speothos venaticus'') is a canine found in Central and South America. In spite of its extensive range, it is very rare in most areas except in Suriname, Guyana and Peru; it was first identified by Peter Wilhelm Lund from fossils ...

. The skull is relatively shorter and broader than those of other canids.

The fur of the African wild dog differs significantly from that of other canids, consisting entirely of stiff bristle-hairs with no underfur. It gradually loses its fur as it ages, with older individuals being almost naked. Colour variation is extreme, and may serve in visual identification, as African wild dogs can recognise each other at distances of . Some geographic variation is seen in coat colour, with northeastern African specimens tending to be predominantly black with small white and yellow patches, while southern African ones are more brightly coloured, sporting a mix of brown, black and white coats. Much of the species' coat patterning occurs on the trunk and legs. Little variation in facial markings occurs, with the muzzle being black, gradually shading into brown on the cheeks and forehead. A black line extends up the forehead, turning blackish-brown on the back of the ears. A few specimens sport a brown teardrop-shaped mark below the eyes. The back of the head and neck are either brown or yellow. A white patch occasionally occurs behind the fore legs, with some specimens having completely white fore legs, chests and throats. The tail is usually white at the tip, black in the middle and brown at the base. Some specimens lack the white tip entirely, or may have black fur below the white tip. These coat patterns can be asymmetrical, with the left side of the body often having different markings from that of the right.

The fur of the African wild dog differs significantly from that of other canids, consisting entirely of stiff bristle-hairs with no underfur. It gradually loses its fur as it ages, with older individuals being almost naked. Colour variation is extreme, and may serve in visual identification, as African wild dogs can recognise each other at distances of . Some geographic variation is seen in coat colour, with northeastern African specimens tending to be predominantly black with small white and yellow patches, while southern African ones are more brightly coloured, sporting a mix of brown, black and white coats. Much of the species' coat patterning occurs on the trunk and legs. Little variation in facial markings occurs, with the muzzle being black, gradually shading into brown on the cheeks and forehead. A black line extends up the forehead, turning blackish-brown on the back of the ears. A few specimens sport a brown teardrop-shaped mark below the eyes. The back of the head and neck are either brown or yellow. A white patch occasionally occurs behind the fore legs, with some specimens having completely white fore legs, chests and throats. The tail is usually white at the tip, black in the middle and brown at the base. Some specimens lack the white tip entirely, or may have black fur below the white tip. These coat patterns can be asymmetrical, with the left side of the body often having different markings from that of the right.

Behaviour

Social and reproductive behaviour

The African wild dog has very strong social bonds, stronger than those of sympatric lions and

The African wild dog has very strong social bonds, stronger than those of sympatric lions and spotted hyena

The spotted hyena (''Crocuta crocuta''), also known as the laughing hyena, is a hyena species, currently classed as the sole extant member of the genus ''Crocuta'', native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is listed as being of least concern by the IUC ...

s; thus, solitary living and hunting are extremely rare in the species.Kingdon, Jonathan (1988). ''East African mammals: an atlas of evolution in Africa, Volume 3, Part 1''. University of Chicago Press. pp. 36–53. . It lives in permanent packs consisting of two to 27 adults and yearling pups. The typical pack size in Kruger National Park

Kruger National Park is a South African National Park and one of the largest game reserves in Africa. It covers an area of in the provinces of Limpopo and Mpumalanga in northeastern South Africa, and extends from north to south and from ea ...

and the Maasai Mara

Maasai Mara, also sometimes spelled Masai Mara and locally known simply as The Mara, is a large national game reserve in Narok, Kenya, contiguous with the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania. It is named in honor of the Maasai people, the ancestr ...

is four or five adults, while packs in Moremi and Selous contain eight or nine. However, larger packs have been observed and temporary aggregations of hundreds of individuals may have gathered in response to the seasonal migration of vast springbok

The springbok (''Antidorcas marsupialis'') is a medium-sized antelope found mainly in south and southwest Africa. The sole member of the genus ''Antidorcas'', this bovid was first described by the German zoologist Eberhard August Wilhelm v ...

herds in Southern Africa.Nowak, Ronald M. (2005). ''Walker's Carnivores of the World''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. p. 112. . Males and females have separate dominance hierarchies, with the latter usually being led by the oldest female. Males may be led by the oldest male, but these can be supplanted by younger specimens; thus, some packs may contain elderly male former pack leaders. The dominant pair typically monopolises breeding. The species differs from most other social species in that males remain in the natal pack, while females disperse (a pattern also found in primate

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians (monkeys and apes, the latter including huma ...

s such as gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or fi ...

s, chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (''Pan troglodytes''), also known as simply the chimp, is a species of great ape native to the forest and savannah of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed subspecies. When its close relative th ...

s, and red colobus

Red colobuses are Old World monkeys of the genus ''Piliocolobus''. It was formerly considered a subgenus within the genus ''Procolobus'', which is now restricted to the olive colobus. They are closely related to the black-and-white colobus monke ...

es). Furthermore, males in any given pack tend to outnumber females 3:1. Dispersing females join other packs and evict some of the resident females related to the other pack members, thus preventing inbreeding and allowing the evicted individuals to find new packs of their own and breed. Males rarely disperse, and when they do, they are invariably rejected by other packs already containing males. Although arguably the most social canid, the species lacks the elaborate facial expressions and body language found in the gray wolf, likely because of the African wild dog's less hierarchical social structure. Furthermore, while elaborate facial expressions are important for wolves in re-establishing bonds after long periods of separation from their family groups, they are not as necessary to African wild dogs, which remain together for much longer periods.

African wild dog populations in East Africa appear to have no fixed breeding season

Seasonal breeders are animal species that successfully mate only during certain times of the year. These times of year allow for the optimization of survival of young due to factors such as ambient temperature, food and water availability, and cha ...

, whereas those in Southern Africa usually breed during the April–July period. During estrus

The estrous cycle (, originally ) is the set of recurring physiological changes that are induced by reproductive hormones in most mammalian therian females. Estrous cycles start after sexual maturity in females and are interrupted by anestrous p ...

, the female is closely accompanied by a single male, which keeps other members of the same sex at bay. The copulatory tie

Canine reproduction is the process of sexual reproduction in domestic dogs, wolves, coyotes and other canine species.

Canine sexual anatomy and development Male reproductive system Erectile tissue

As with all mammals, a dog's penis is made up o ...

characteristic of mating in most canids has been reported to be absent or very brief (less than one minute) in African wild dog, possibly an adaptation to the prevalence of larger predators in its environment. The gestation period

In mammals, pregnancy is the period of reproduction during which a female carries one or more live offspring from implantation in the uterus through gestation. It begins when a fertilized zygote implants in the female's uterus, and ends once it ...

lasts 69–73 days, with the interval between each pregnancy being 12–14 months typically. The African wild dog produces more pups than any other canid, with litters containing around six to 16 pups, with an average of 10, thus indicating that a single female can produce enough young to form a new pack every year. Because the amount of food necessary to feed more than two litters would be impossible to acquire by the average pack, breeding is strictly limited to the dominant female, which may kill the pups of subordinates. After giving birth, the mother stays close to the pups in the den, while the rest of the pack hunts. She typically drives away pack members approaching the pups until the latter are old enough to eat solid food at three to four weeks of age. The pups leave the den around the age of three weeks and are suckled outside. The pups are weaned at the age of five weeks, when they are fed regurgitated meat by the other pack members. By seven weeks, the pups begin to take on an adult appearance, with noticeable lengthening in the legs, muzzle, and ears. Once the pups reach the age of eight to 10 weeks, the pack abandons the den and the young follow the adults during hunts. The youngest pack members are permitted to eat first on kills, a privilege which ends once they become yearlings.

Ratio male/female

Packs of African wild dogs have a high ratio of males to females. This is a consequence of the males mostly staying with the pack whilst female offspring disperse and is supported by a changing sex-ratio in consecutive litters. Those born to maiden females contain a higher proportion of males, second litters are half and half and subsequent litters biased towards females with this trend increasing as females get older. As a result, the earlier litters provide stable hunters whilst the higher ratio of dispersals amongst the females stops a pack from getting too big.Sneeze communication and "voting"

African wild dog populations in theOkavango Delta

The Okavango Delta (or Okavango Grassland; formerly spelled "Okovango" or "Okovanggo") in Botswana is a swampy inland delta formed where the Okavango River reaches a tectonic trough at an altitude of 930–1,000 m in the central part of the en ...

have been observed "rallying" before they set out to hunt. Not every rally results in a departure, but departure becomes more likely when more individual dogs "sneeze". These sneeze

A sneeze (also known as sternutation) is a semi-autonomous, convulsive expulsion of air from the lungs through the nose and mouth, usually caused by foreign particles irritating the nasal mucosa. A sneeze expels air forcibly from the mouth and n ...

s are characterized by a short, sharp exhale through the nostrils. When members of dominant mating pairs sneeze first, the group is much more likely to depart. If a dominant dog initiates, around three sneezes guarantee departure. When less dominant dogs sneeze first, if enough others also sneeze (about 10), then the group will go hunting. Researchers assert that wild dogs in Botswana, "use a specific vocalization (the sneeze) along with a variable quorum response mechanism in the decision-making process o go hunting at a particular moment.

Inbreeding avoidance

Because the African wild dog largely exists in fragmented, small populations, its existence is endangered. Inbreeding avoidance by mate selection is characteristic of the species and has important potential consequences for population persistence. Inbreeding is rare within natal packs. Inbreeding behavior may have been selected against evolutionarily because it leads to the expression of recessive deleterious alleles. Computer simulations indicate that all populations continuing to avoid incestuous mating will become extinct within 100 years due to the unavailability of unrelated mates. Thus, the impact of reduced numbers of suitable unrelated mates will likely have a severe demographic impact on the future viability of small wild dog populations.Hunting and feeding behaviour

The African wild dog is a specialised pack hunter of common medium-sizedantelope

The term antelope is used to refer to many species of even-toed ruminant that are indigenous to various regions in Africa and Eurasia.

Antelope comprise a wastebasket taxon defined as any of numerous Old World grazing and browsing hoofed mammals ...

s.. It and the cheetah are the only primarily diurnal African large predators. The African wild dog hunts by approaching prey silently, then chasing it in a pursuit clocking at up to for 10–60 minutes. The average chase covers some , during which the prey animal, if large, is repeatedly bitten on the legs, belly, and rump until it stops running, while smaller prey is simply pulled down and torn apart.

African wild dogs adjust their hunting strategy to the particular prey species. They will rush at wildebeest to panic the herd and isolate a vulnerable individual, but pursue territorial antelope species (which defend themselves by running in wide circles) by cutting across the arc to foil their escape. Medium-sized prey is often killed in 2–5 minutes, whereas larger prey such as wildebeest may take half an hour to pull down. Male wild dogs usually perform the task of grabbing dangerous prey, such as warthogs

''Phacochoerus'' is a genus in the family Suidae, commonly known as warthogs (pronounced ''wart-hog''). They are pigs who live in open and semi-open habitats, even in quite arid regions, in sub-Saharan Africa. The two species were formerly co ...

, by the nose.

Hunting success varies with prey type, vegetation cover and pack size, but African wild dogs tend to be very successful: often more than 60% of their chases end in a kill, sometimes up to 90%. Despite their smaller size, they are much more consistently successful than lion (27–30%) and hyena (25–30%), but African wild dogs commonly lose their kills to these two large predators. An analysis of 1,119 chases by a pack of six Okavango wild dogs showed that most were short distance uncoordinated chases, and the ''individual'' kill rate was only 15.5 percent. Because kills are shared, each dog enjoyed an efficient benefit–cost ratio A benefit–cost ratio (BCR) is an indicator, used in cost–benefit analysis, that attempts to summarize the overall value for money of a project or proposal. A BCR is the ratio of the benefits of a project or proposal, expressed in monetary terms, ...

.

Small prey such as rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are na ...

s, hare

Hares and jackrabbits are mammals belonging to the genus ''Lepus''. They are herbivores, and live solitarily or in pairs. They nest in slight depressions called forms, and their young are able to fend for themselves shortly after birth. The ge ...

s and birds are hunted singly, with dangerous prey such as cane rat

The genus ''Thryonomys'', also known as the cane rats or grasscutters, is a genus of rodent found throughout Africa south of the Sahara, the only members of the family Thryonomyidae. They are eaten in some African countries and are a pest species ...

s and porcupine

Porcupines are large rodents with coats of sharp spines, or quills, that protect them against predation. The term covers two families of animals: the Old World porcupines of family Hystricidae, and the New World porcupines of family, Erethizont ...

s being killed with a quick and well-placed bite to avoid injury. Small prey is eaten entirely, while large animals are stripped of their meat and organs, leaving the skin, head, and skeleton intact. The African wild dog is a fast eater, with a pack being able to consume a Thomson's gazelle

Thomson's gazelle (''Eudorcas thomsonii'') is one of the best known species of gazelles. It is named after explorer Joseph Thomson and is sometimes referred to as a "tommie". It is considered by some to be a subspecies of the red-fronted gazelle a ...

in 15 minutes. In the wild, the species' consumption is per African wild dog a day, with one pack of 17–43 individuals in East Africa having been recorded to kill three animals per day on average.

Unlike most social predators, African wild dogs will regurgitate food for other adults as well as young family members. Pups old enough to eat solid food are given first priority at kills, eating even before the dominant pair; subordinate adult dogs help feed and protect the pups.

Ecology

Habitat

The African wild dog is mostly found insavanna

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to ...

and arid

A region is arid when it severely lacks available water, to the extent of hindering or preventing the growth and development of plant and animal life. Regions with arid climates tend to lack vegetation and are called xeric or desertic. Most ar ...

zones, generally avoiding forested areas. This preference is likely linked to the animal's hunting habits, which require open areas that do not obstruct vision or impede pursuit. Nevertheless, it will travel through scrub, woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the ''plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (see ...

and montane

Montane ecosystems are found on the slopes of mountains. The alpine climate in these regions strongly affects the ecosystem because temperatures fall as elevation increases, causing the ecosystem to stratify. This stratification is a crucial f ...

areas in pursuit of prey. Forest-dwelling populations of African wild dogs have been identified, including one in the Harenna Forest

The Harenna Forest is a montane tropical evergreen forest in Ethiopia's Bale Mountains. The forest covers the southern slope of the mountains, extending from 1450 to 3200 meters elevation. The Bale Mountains are in Ethiopia's Oromia Region, and fo ...

, a wet montane forest up to in altitude in the Bale Mountains

The Bale Mountains (also known as the Urgoma Mountains) are mountain ranges in the Oromia Region of southeast Ethiopia, south of the Awash River, part of the Ethiopian Highlands. They include Tullu Demtu, the second-highest mountain in Ethiopia ...

of Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

. At least one record exists of a pack being sighted on the summit

A summit is a point on a surface that is higher in elevation than all points immediately adjacent to it. The topography, topographic terms acme, apex, peak (mountain peak), and zenith are synonymous.

The term (mountain top) is generally used ...

of Mount Kilimanjaro

Mount Kilimanjaro () is a dormant volcano in Tanzania. It has three volcanic cones: Kibo, Mawenzi, and Shira. It is the highest mountain in Africa and the highest free-standing mountain above sea level in the world: above sea level and ab ...

. In Zimbabwe, the species has been recorded at altitudes of . In Ethiopia, this species has been found at great altitudes; several live wild dog packs have been sighted at altitudes of from 1,900 to 2,800 m, and a dead individual was found in June 1995 at on the Sanetti Plateau

The Sanetti Plateau is a major plateau of the Ethiopian Highlands, in the Oromia Region of Ethiopia. The plateau is the highest part of the Bale Mountains, and is located within Bale Mountains National Park.L.J.G. van der Maesen, X.M. van der Bu ...

.

Diet

A species-wide study showed that by preference, where available, five species were the most regularly selected prey, namely the

A species-wide study showed that by preference, where available, five species were the most regularly selected prey, namely the greater kudu

The greater kudu (''Tragelaphus strepsiceros'') is a woodland antelope found throughout eastern and southern Africa. Despite occupying such widespread territory, they are sparsely populated in most areas due to declining habitat, deforestation, ...

, Thomson's gazelle

Thomson's gazelle (''Eudorcas thomsonii'') is one of the best known species of gazelles. It is named after explorer Joseph Thomson and is sometimes referred to as a "tommie". It is considered by some to be a subspecies of the red-fronted gazelle a ...

, impala

The impala or rooibok (''Aepyceros melampus'') is a medium-sized antelope found in eastern and southern Africa. The only extant member of the genus '' Aepyceros'' and tribe Aepycerotini, it was first described to European audiences by Germa ...

, Cape bushbuck

The Cape bushbuck (''Tragelaphus sylvaticus'') is a common and a widespread species of antelope in sub-Saharan Africa.Wronski T, Moodley Y. (2009)Bushbuck, harnessed antelope or both? ''Gnusletter'', 28(1):18-19. Bushbuck are found in a wide ra ...

and blue wildebeest

The blue wildebeest (''Connochaetes taurinus''), also called the common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu, is a large antelope and one of the two species of wildebeest. It is placed in the genus '' Connochaetes'' and family Bovidae, a ...

. More specifically, in East Africa, its most common prey is Thomson's gazelle, while in Central and Southern Africa, it targets impala

The impala or rooibok (''Aepyceros melampus'') is a medium-sized antelope found in eastern and southern Africa. The only extant member of the genus '' Aepyceros'' and tribe Aepycerotini, it was first described to European audiences by Germa ...

, reedbuck

Reedbuck is a common name for Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it ...

, kob

The kob (''Kobus kob'') is an antelope found across Central Africa and parts of West Africa and East Africa. Together with the closely related reedbucks, waterbucks, lechwe, Nile lechwe, and puku, it forms the Reduncinae tribe. Found along ...

, lechwe

The lechwe, red lechwe, or southern lechwe (''Kobus leche'') is an antelope found in wetlands of south-central Africa.

Range

The lechwe is native to Botswana, Zambia, southeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, northeastern Namibia, and eas ...

and springbok

The springbok (''Antidorcas marsupialis'') is a medium-sized antelope found mainly in south and southwest Africa. The sole member of the genus ''Antidorcas'', this bovid was first described by the German zoologist Eberhard August Wilhelm v ...

. and smaller prey such as dik-dik

A dik-dik is the name for any of four species of small antelope in the genus ''Madoqua'' that live in the bushlands of eastern and southern Africa.

Dik-diks stand about at the shoulder, are long, weigh and can live for up to 10 years. Dik- ...

, hare

Hares and jackrabbits are mammals belonging to the genus ''Lepus''. They are herbivores, and live solitarily or in pairs. They nest in slight depressions called forms, and their young are able to fend for themselves shortly after birth. The ge ...

s, spring hares, insects and cane rats. Staple prey sizes are usually between , though some local studies put upper prey sizes as variously . In the case of larger species such as kudu and wildebeest, calves are largely but not exclusively targeted. However, certain packs in the Serengeti

The Serengeti ( ) ecosystem is a geographical region in Africa, spanning northern Tanzania. The protected area within the region includes approximately of land, including the Serengeti National Park and several game reserves. The Serengeti ...

specialized in hunting adult plains zebra

The plains zebra (''Equus quagga'', formerly ''Equus burchellii''), also known as the common zebra, is the most common and geographically widespread species of zebra. Its range is fragmented, but spans much of southern and eastern Africa south of ...

s weighing up to quite frequently. Another study claimed that some prey taken by wild dogs could weigh up to . One pack was recorded to occasionally prey on bat-eared fox

The bat-eared fox (''Otocyon megalotis'') is a species of fox found on the African savanna. It is the only extant species of the genus ''Otocyon'' and considered a basal canid species. Fossil records indicate this canid first appeared during th ...

es, rolling on the carcasses before eating them. African wild dogs rarely scavenge, but have on occasion been observed to appropriate carcasses from spotted hyenas, leopards, cheetahs, lions, and animals caught in snare

SNARE proteins – " SNAP REceptor" – are a large protein family consisting of at least 24 members in yeasts, more than 60 members in mammalian cells,

and some numbers in plants. The primary role of SNARE proteins is to mediate vesicle fu ...

s.

Enemies and competitors

Lion

The lion (''Panthera leo'') is a large Felidae, cat of the genus ''Panthera'' native to Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body; short, rounded head; round ears; and a hairy tuft at the end of its tail. It is sexually dimorphi ...

s dominate African wild dogs and are a major source of mortality for both adults and pups. Population densities of African wild dogs are low in areas where lions are more abundant. One pack reintroduced into Etosha National Park

Etosha National Park is a national park in northwestern Namibia and one of the largest national parks in Africa. It was proclaimed a game reserve in March 1907 in Ordinance 88 by the Governor of German South West Africa, Friedrich von Lindequist. ...

was destroyed by lions. A population crash in lions in the Ngorongoro Crater

The Ngorongoro Conservation Area (, ) is a protected area and a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in Ngorongoro District, west of Arusha City in Arusha Region, within the Crater Highlands geological area of northern Tanzania. The area is nam ...

during the 1960s resulted in an increase in African wild dog sightings, only for their numbers to decline once the lions recovered. As with other large predators killed by lion prides, the dogs are usually killed and left uneaten by the lions, indicating the competitive rather than predatory nature of the larger species' dominance. However, a few cases have been reported of old and wounded lions falling prey to African wild dogs.Schaller, G. B. (1972). ''The Serengeti lion: A study of predator-prey relations''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 188. . On occasion, packs of wild dogs have been observed defending pack members attacked by single lions, sometimes successfully. One pack in the Okavango in March 2016 was photographed by safari guides waging "an incredible fight" against a lioness that attacked a subadult dog at an impala kill, which forced the lioness to retreat, although the subadult dog died. A pack of four wild dogs was observed furiously defending an old adult male dog from a male lion that attacked it at a kill; the dog survived and rejoined the pack.

Spotted hyena

The spotted hyena (''Crocuta crocuta''), also known as the laughing hyena, is a hyena species, currently classed as the sole extant member of the genus ''Crocuta'', native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is listed as being of least concern by the IUC ...

s are important kleptoparasites and follow packs of African wild dogs to appropriate their kills. They typically inspect areas where African wild dogs have rested and eat any food remains they find. When approaching African wild dogs at a kill, solitary hyenas approach cautiously and attempt to take off with a piece of meat unnoticed, though they may be mobbed in the attempt. When operating in groups, spotted hyenas are more successful in pirating African wild dog kills, though the latter's greater tendency to assist each other puts them at an advantage against spotted hyenas, which rarely work cooperatively. Cases of African wild dogs scavenging from spotted hyenas are rare. Although African wild dog packs can easily repel solitary hyenas, on the whole, the relationship between the two species is a one-sided benefit for the hyenas, with African wild dog densities being negatively correlated with high hyena populations. Beyond piracy, cases of interspecific killing of African wild dogs by spotted hyenas are documented. African wild dogs are apex predator

An apex predator, also known as a top predator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the highest trophic lev ...

s, normally only fatally losing contests to larger social carnivores, although anecdotally Nile crocodile

The Nile crocodile (''Crocodylus niloticus'') is a large crocodilian native to freshwater habitats in Africa, where it is present in 26 countries. It is widely distributed throughout sub-Saharan Africa, occurring mostly in the central, eastern ...

s may opportunistically and rarely prey upon a wild dog. When briefly unprotected, wild dog pups may occasionally be vulnerable to large eagle

Eagle is the common name for many large birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of genera, some of which are closely related. Most of the 68 species of eagle are from Eurasia and Africa. Outside this area, just ...

s, such as the martial eagle

The martial eagle (''Polemaetus bellicosus'') is a large eagle native to sub-Saharan Africa.Ferguson-Lees & Christie, ''Raptors of the World''. Houghton Mifflin Company (2001), . It is the only member of the genus ''Polemaetus''. A species of t ...

, when they venture out of their dens.

Distribution

African wild dogs once ranged across much ofsub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

, being absent only in the driest desert regions and lowland forests. The species has been largely exterminated in North and West Africa, and has been greatly reduced in number in Central Africa and northeast Africa. The majority

A majority, also called a simple majority or absolute majority to distinguish it from #Related terms, related terms, is more than half of the total.Dictionary definitions of ''majority'' aMerriam-WebsterBotswana

Botswana (, ), officially the Republic of Botswana ( tn, Lefatshe la Botswana, label=Setswana, ), is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. Botswana is topographically flat, with approximately 70 percent of its territory being the Kalahar ...

, Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

, and Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozam ...

. However, it is hard to track where they are and how many there are because of the loss of habitat.

North Africa

The species is very rare in North Africa, and whatever populations remain may be of high conservation value, as they are likely to be genetically distinct from other ''L. pictus'' populations.Fanshawe, J. H., Ginsberg, J. R., Sillero-Zubiri, C. & Woodroffe, R., eds. (1997). The Status & Distribution of Remaining Wild Dog Populations. In Rosie Woodroffe, Joshua Ginsberg & David MacDonald, eds., ''Status Survey and Conservation Plan: The African Wild Dog'': 11–56. IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group.West Africa

The species is faring poorly in most of West Africa, with the only potentially viable population occurring in Senegal'sNiokolo-Koba National Park

The Niokolo-Koba National Park (french: Parc National du Niokolo Koba, PNNK) is a World Heritage Site and natural protected area in south eastern Senegal near the Guinea border. It is served by Niokolo-Koba Airport, an unpaved airstrip.

Nation ...

. African wild dogs are occasionally sighted in other parts of Senegal, Guinea and Mali.

Central Africa

The species is doing poorly in Central Africa, being extinct in Gabon, the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of Congo. The only viable populations occur in the Central African Republic, Chad and especially Cameroon.East Africa

The African wild dog's range in East Africa is patchy, having been eradicated in Uganda and much of Kenya. A small population occupies an area encompassing southern Ethiopia, South Sudan, northern Kenya and probably northern Uganda. The species may still occur in small numbers in southern Somalia and it is almost certainly extinct in Rwanda, Burundi and Eritrea. Nevertheless, it remains somewhat numerous in southern Tanzania, particularly in theSelous Game Reserve

The Selous Game Reserve, now renamed Nyerere National Park, is a protected area in southern Tanzania. It covers a total area of and has additional buffer zones. It was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982 due to its wildlife diversity ...

and Mikumi National Park, both of which are occupied by what could be Africa's largest African wild dog population.

Southern Africa

Southern Africa contains numerous viable African wild dog populations, one of which encompasses northern Botswana, northeastern Namibia and western Zimbabwe. In South Africa, around 400 specimens occur in the country's Kruger National Park. Zambia holds two large populations, one in Kafue National Park and another in the Luangwa Valley. However, the species is rare in Malawi and probably extinct in Mozambique.Threats

The African wild dog is primarily threatened byhabitat fragmentation

Habitat fragmentation describes the emergence of discontinuities (fragmentation) in an organism's preferred environment (habitat), causing population fragmentation and ecosystem decay. Causes of habitat fragmentation include geological processes ...

, which results in human–wildlife conflict

Human–wildlife conflict (HWC) refers to the negative interactions between human and wild animals, with undesirable consequences both for people and their resources, on the one hand, and wildlife and their habitats on the other (IUCN 2020). HWC ...

, transmission of infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dise ...

s and high mortality rates.

Surveys in the Central African Republic's Chinko

Chinko, also known as Chinko Nature Reserve and the Chinko Project Area, is a protected area in the Central African Republic. The nonprofit conservation organization African Parks began managing Chinko in partnership with the government of the Ce ...

area revealed that the African wild dog population decreased from 160 individuals in 2012 to 26 individuals in 2017. At the same time, transhumant

Transhumance is a type of pastoralism or nomadism, a seasonal movement of livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and lower val ...

pastoralists from the border area with Sudan moved in the area with their livestock. Rangers confiscated large amounts of poison

Poison is a chemical substance that has a detrimental effect to life. The term is used in a wide range of scientific fields and industries, where it is often specifically defined. It may also be applied colloquially or figuratively, with a broa ...

and found multiple lion

The lion (''Panthera leo'') is a large Felidae, cat of the genus ''Panthera'' native to Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body; short, rounded head; round ears; and a hairy tuft at the end of its tail. It is sexually dimorphi ...

cadaver

A cadaver or corpse is a dead human body that is used by medical students, physicians and other scientists to study anatomy, identify disease sites, determine causes of death, and provide tissue to repair a defect in a living human being. Stud ...

s in the camps of livestock herders. They were accompanied by armed merchants who also engage in poaching

Poaching has been defined as the illegal hunting or capturing of wild animals, usually associated with land use rights.

Poaching was once performed by impoverished peasants for subsistence purposes and to supplement meager diets. It was set a ...

large herbivores, sale of bushmeat

Bushmeat is meat from wildlife species that are hunted for human consumption, most often referring to the meat of game in Africa. Bushmeat represents

a primary source of animal protein and a cash-earning commodity for inhabitants of humid tropi ...

and trading lion skins.

In culture

Ancient Egypt

Artistic depictions of African wild dogs are prominent on

Artistic depictions of African wild dogs are prominent on cosmetic palette

Cosmetic palettes are archaeological Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, originally used in predynastic Egypt, predynastic ancient Egypt, Egypt to grind and apply ingredients for facial or body cosmetics. The decorative palettes of the late 4th mill ...

s and other objects from Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

's predynastic period

Prehistoric Egypt and Predynastic Egypt span the period from the earliest human settlement to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period around 3100 BC, starting with the first Pharaoh, Narmer for some Egyptologists, Hor-Aha for others, with ...

, likely symbolising order over chaos and the transition between the wild and the domestic dog. Predynastic hunters may have also identified with the African wild dog, as the Hunters Palette

The Hunters Palette or Lion Hunt Palette is a circa 3100 BCE cosmetic palette from the Naqada III period of late prehistoric Egypt. The palette is broken: part is held by the British Museum and part is in the collection of the Louvre.

Content

The ...

shows them wearing the animals' tails on their belts. By the dynastic period, African wild dog illustrations became much less represented, and the animal's symbolic role was largely taken over by the wolf.Hendrickx, S. (2006). The dog, the ''Lycaon pictus'' and order over chaos in Predynastic Egypt. n:Kroeper, K.; Chłodnicki, M. & Kobusiewicz, M. (eds.), ''Archaeology of Early Northeastern Africa''. Studies in African Archaeology 9. Poznań: Poznań Archaeological Museum: 723–749.

Ethiopia

According toEnno Littmann

Ludwig Richard Enno Littmann (16 September 1875, Oldenburg – 4 May 1958, Tübingen) was a German orientalist.

In 1906 he succeeded Theodor Nöldeke as chair of Oriental languages at the University of Strasbourg. Later on, he served as a profes ...

, the people of Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

's Tigray Region

The Tigray Region, officially the Tigray National Regional State, is the northernmost regional state in Ethiopia. The Tigray Region is the homeland of the Tigrayan, Irob, and Kunama people. Its capital and largest city is Mekelle. Tigray is ...

believed that injuring a wild dog with a spear would result in the animal dipping its tail in its wounds and flicking the blood at its assailant, causing instant death. For this reason, Tigrean shepherds would repel wild dog attacks with pebbles rather than with edged weapons.

San people

The African wild dog also plays a prominent role in the mythology of Southern Africa'sSan people

The San peoples (also Saan), or Bushmen, are members of various Khoe, Tuu, or Kxʼa-speaking indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures that are the first cultures of Southern Africa, and whose territories span Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia, ...

. In one story, the wild dog is indirectly linked to the origin of death

The origin of death is a theme in the myths of many cultures. Death is a universal feature of human life, so stories about its origin appear to be universal in human cultures. As such it is a form of cosmological myth (a type of myth that explains ...

, as the hare

Hares and jackrabbits are mammals belonging to the genus ''Lepus''. They are herbivores, and live solitarily or in pairs. They nest in slight depressions called forms, and their young are able to fend for themselves shortly after birth. The ge ...

is cursed by the moon to be forever hunted by African wild dogs after the hare rebuffs the moon's promise to allow all living things to be reborn after death. Another story has the god Cagn taking revenge on the other gods by sending a group of men transformed into African wild dogs to attack them, though who won the battle is never revealed. The San of Botswana see the African wild dog as the ultimate hunter and traditionally believe that shaman