Ouachita River on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Ouachita River ( ) is a river that runs south and east through the U.S. states of

The National Map

, accessed June 3, 2011 in Catahoula and Concordia parishes until it joins the Red River, which flows into both the Atchafalaya River and the Mississippi River, via the Old River Control Structure.

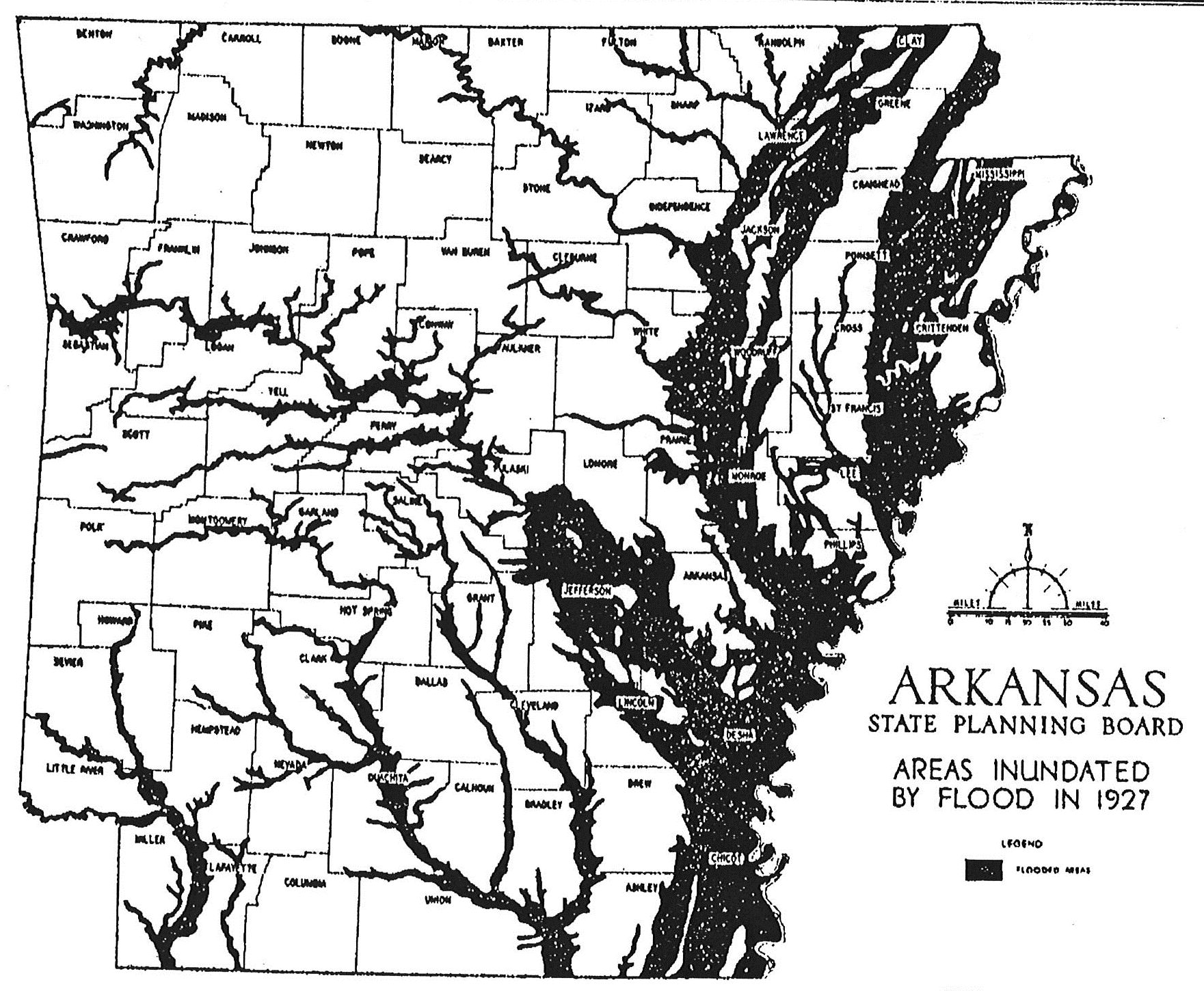

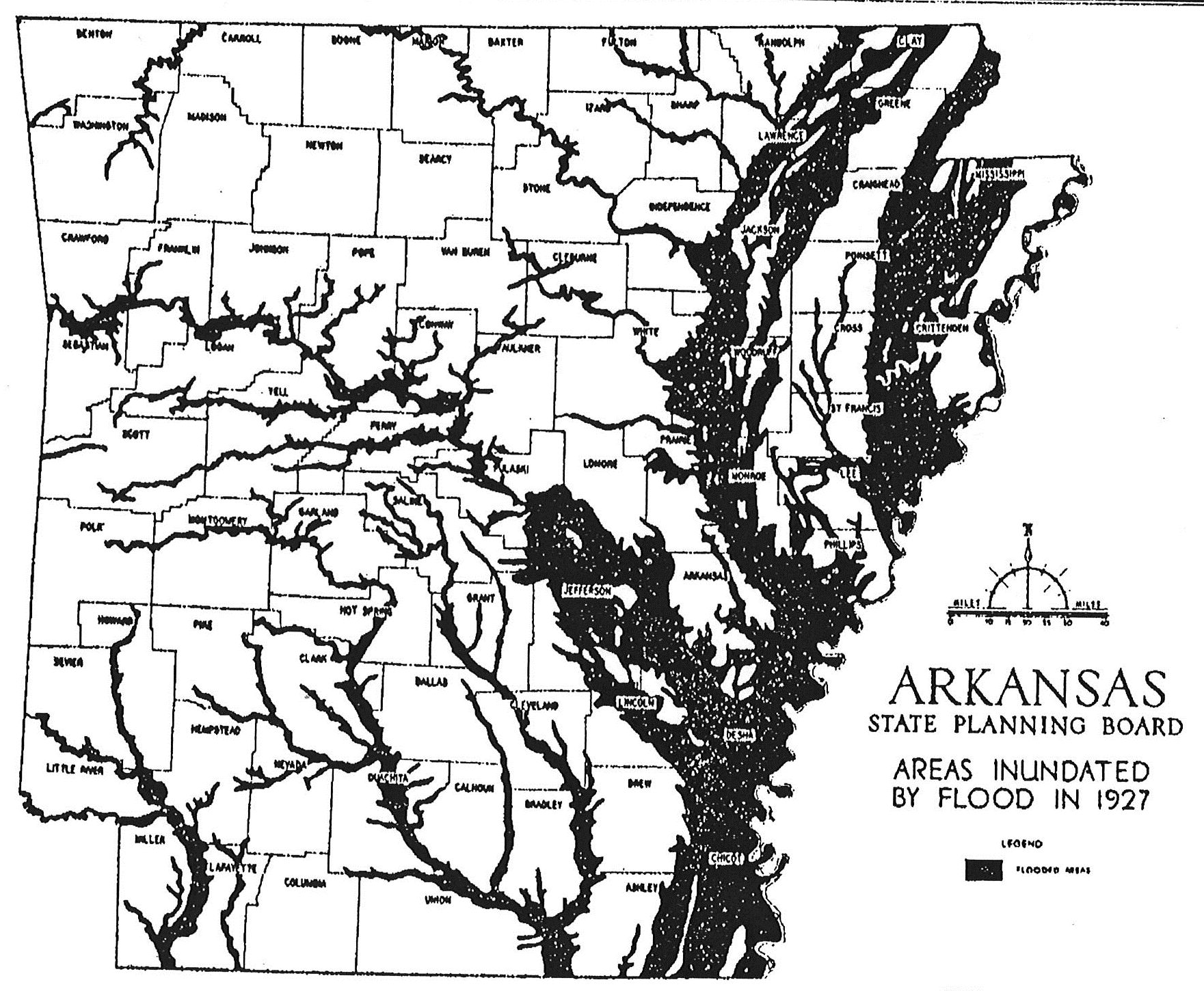

Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 flooded the areas along the Ouachita Rivers along with many other rivers.

Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 flooded the areas along the Ouachita Rivers along with many other rivers.

The river continues to be utilized for commercial navigation on a smaller scale than during its "

The river continues to be utilized for commercial navigation on a smaller scale than during its "

Upper Ouachita River

Lower Ouachita River

Ouachita River Foundation

{{authority control Rivers of Arkansas Rivers of Louisiana Tributaries of the Red River of the South Rivers of Polk County, Arkansas Rivers of Garland County, Arkansas Rivers of Hot Spring County, Arkansas Rivers of Clark County, Arkansas Rivers of Ouachita County, Arkansas Rivers of Ashley County, Arkansas Rivers of Catahoula Parish, Louisiana Rivers of Ouachita Parish, Louisiana Rivers of Caldwell Parish, Louisiana Rivers of Concordia Parish, Louisiana

Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

and Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

, joining the Tensas River to form the Black River near Jonesville, Louisiana. It is the 25th-longest river in the United States (by main stem).

Course

The Ouachita River begins in theOuachita Mountains

The Ouachita Mountains (), simply referred to as the Ouachitas, are a mountain range in western Arkansas and southeastern Oklahoma. They are formed by a thick succession of highly deformed Paleozoic strata constituting the Ouachita Fold and Thru ...

near Mena, Arkansas

Mena ( ) is a city in Polk County, Arkansas, Polk County, Arkansas, United States. It is also the county seat of Polk County. The population was 5,558 as of the United States Census, 2020, 2020 census. Mena is included in the Ark-La-Tex socio-econ ...

. It flows east into Lake Ouachita, a reservoir created by Blakely Mountain Dam. The North Fork and South Fork of the Ouachita flow into Lake Ouachita to join the main stream. Portions of the river in this region flow through the Ouachita National Forest. From the lake, the Ouachita flows south into Lake Hamilton Lake Hamilton or Hamilton Lake may refer to:

* Hamilton Lake (Alberta), Canada

* Hamilton Lake (Nova Scotia), Canada

* Lake Rotoroa (Hamilton, New Zealand) or Hamilton Lake, a lake in New Zealand

**Hamilton Lake (suburb), a residential suburb around ...

, a reservoir created by Carpenter Dam, named after Flavius Josephus Carpenter. The city of Hot Springs

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by circ ...

lies on the north side of Lake Hamilton. Another reservoir, Lake Catherine, impounds the Ouachita just below Lake Hamilton. Below Lake Catherine, the river flows free through most of the rest of Arkansas.

Just below Lake Catherine, the river bends south near Malvern, and collects the Caddo River near Arkadelphia. Downstream, the Little Missouri River joins the Ouachita. After passing the city of Camden, shortly downstream from where dredging for navigational purposes begins, the river collects the waters of Smackover Creek and later the Ouachita's main tributary, the Saline River. South of the Saline, the Ouachita flows into Lake Jack Lee, a reservoir created by the Ouachita and Black River Project, just north of the Louisiana state line. The Felsenthal National Wildlife Refuge encompasses the Ouachita from the Saline River to Lake Jack Lee's mouth.

Below Lake Jack Lee, the Ouachita continues south into Louisiana. The river flows generally south through the state, collecting the tributary waters of Bayou Bartholomew, Bayou de Loutre, Bayou d'Arbonne, the Boeuf River, and the Tensas River.

The Ouachita has five locks and dams along its length, located at Camden, Calion, and Felsenthal, Arkansas, and in Columbia

Columbia may refer to:

* Columbia (personification), the historical female national personification of the United States, and a poetic name for America

Places North America Natural features

* Columbia Plateau, a geologic and geographic region i ...

and Jonesville, Louisiana.

Black River

The river below the junction with the Tensas at is called the Black River and flows for U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map

, accessed June 3, 2011 in Catahoula and Concordia parishes until it joins the Red River, which flows into both the Atchafalaya River and the Mississippi River, via the Old River Control Structure.

History

The river is named for the Ouachita tribe, one of several historic tribes who lived along it. Others included theCaddo

The Caddo people comprise the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, a federally recognized tribe headquartered in Binger, Oklahoma. They speak the Caddo language.

The Caddo Confederacy was a network of Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, w ...

, Osage Nation

The Osage Nation ( ) ( Osage: 𐓁𐒻 𐓂𐒼𐒰𐓇𐒼𐒰͘ ('), "People of the Middle Waters") is a Midwestern Native American tribe of the Great Plains. The tribe developed in the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys around 700 BC along ...

, Tensa, Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classif ...

, and Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

. The historian Muriel Hazel Wright suggested that word Ouachita ''owa chito'' is a Choctaw phrase meaning "hunt big" or "good hunting grounds".

Before the rise of the historic tribes, their indigenous ancestors lived along the river for thousands of years. In the Lower Mississippi Valley, they began building monumental earthwork mounds in the Middle Archaic period (6000–2000 BC in Louisiana). The earliest construction was Watson Brake, an 11-mound complex built about 3500 BC by hunter gatherers in present-day Louisiana. The discovery and dating of several such early sites in northern Louisiana has changed the traditional model, which associated mound building with sedentary, agricultural societies, but these cultures did not develop for thousands of years.

The largest such prehistoric mound was destroyed in the 20th century during construction of a bridge at Jonesville, Louisiana. Likely built by the Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building large, eart ...

, which rose about 1000 AD on the Mississippi and its tributaries, this mound was reported in use as late as 1540 by the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and ''conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

. On his expedition through this area, he encountered Indians occupying the site. A lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an average ...

strike destroyed the temple on the mound that year, which was seen as a bad omen by the tribe. They never rebuilt the temple, and were recorded as abandoning the site in 1736.

Land speculators

During the late 1700s, when the area was controlled by the Spanish and French, the river served as a route for early colonists, and for land speculators such as the self-styled Baron de Bastrop. The "Bastrop lands" later passed into the hands of another speculator, former Vice PresidentAaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805. Burr's legacy is defined by his famous personal conflict with Alexand ...

. He saw potential for big profits in the event of a war with Spain following the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or ap ...

. Burr and many of his associates were arrested for treason, before their band of armed settlers reached the Ouachita.

During the 1830s, the Ouachita River Valley attracted land speculators from New York and southeastern cities. Its rich soil and accessibility due to the country's elaborate river steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. Steamboats sometimes use the ship prefix, prefix designation SS, S.S. or S/S ...

network made it desirable.

One of the investors from the east was Meriwether Lewis Randolph, the youngest grandson of Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

. He was building a home on the Ouachita River in what is now Clark County, Arkansas

Clark County is a county located in the south-central part of the U.S. state of Arkansas. As of the 2010 census, the population was 22,995. The county seat is Arkadelphia. The Arkadelphia, AR Micropolitan Statistical Area includes all of Cla ...

, when he died of malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

in 1837. He had been appointed Secretary of the Arkansas Territory by President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

in 1835, and had relinquished his commission when Arkansas became a state in 1836.

Steamboats, 1819 to 1890

Steamboats operated on the Red River toShreveport

Shreveport ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Louisiana. It is the third most populous city in Louisiana after New Orleans and Baton Rouge, respectively. The Shreveport–Bossier City metropolitan area, with a population of 393,406 in 2020, is ...

, Louisiana.

In April 1815, Captain Henry Miller Shreve was the first person to bring a steamboat, the Enterprise, up the Red River.

During the 1830s, farmers cultivated land for large cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

plantations; dependent on slave labor, cotton production supported new planter wealth in the ante-bellum years. Steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. Steamboats sometimes use the ship prefix, prefix designation SS, S.S. or S/S ...

s ran scheduled trips between Camden, Arkansas

Camden is a city in and the county seat of Ouachita County in the south-central part of the U.S. state of Arkansas. The city is located about 100 miles south of Little Rock. Situated on bluffs overlooking the Ouachita River, the city developed ...

and . A person could travel from any eastern city to the Ouachita River without touching land, except to transfer from one steamboat to another.

In the late 1830s, the steamboats in rivers on the west side of the Mississippi River were a long, wide, shallow draft vessel, lightly built with an engine on the deck. These newer steamboats could sail in just 20 inches of water. Contemporaries claimed that they could "run with a lot of heavy dew".

In 1881 a snagboat was employed on the river and a boat for dredging

Dredging is the excavation of material from a water environment. Possible reasons for dredging include improving existing water features; reshaping land and water features to alter drainage, navigability, and commercial use; constructing d ...

in the shoals to the amount of $141,879.24. Earlier plans had called for the construction of locks and dams.

Civil War

Skirmishes took place near the Ouachita River during theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. On September 1, 1863, forces of the Seventeenth Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

led by Brig. Gen. M. M. Crocker crossed from Natchez, Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

to Vidalia, the seat of Concordia Parish, and moved toward the lower Ouachita in the section called the Black River. That night the Confederate steamer ''Rinaldo'' was captured by Union forces after a short artillery duel and was destroyed. Crocker fought with the few troops stationed on the Black River and moved toward Harrisonburg, seat of Catahoula Parish.

Navigation

A 337-mile-long "Ouachita-Black Rivers Navigation Project" began in 1902, to create a navigable waterway fromCamden, Arkansas

Camden is a city in and the county seat of Ouachita County in the south-central part of the U.S. state of Arkansas. The city is located about 100 miles south of Little Rock. Situated on bluffs overlooking the Ouachita River, the city developed ...

to Jonesville, Louisiana, and when completed in 1924 included six locks and dams that were 84 feet wide and 600 feet in length, having from 3 to 5 tainter gates. Including the Black River the total navigable length is 351 miles. The Ouachita-Black Rivers Navigation Project has less than a million tons of shipping annually which has the likely prospect of the future withdrawal of federal support. The project's system of dams and locks enhances the river's recreational use and regional water supply.

Floods

=Flood of 1882

= The Ouachita River reached a historic flood stage crest with a river gauge reading at Camden, Arkansas of 46 feet on May 12, 1882.=Flood of 1927

= In Monroe, Louisiana during a flood on May 4, 1927 the high water mark on river gage reading was 48.6 feet. Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 flooded the areas along the Ouachita Rivers along with many other rivers.

Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 flooded the areas along the Ouachita Rivers along with many other rivers.

=Flood of 1932

= In February 1932, the Ouachita River rose 1.5 feet higher than the May 4, 1927 flood. The annual high water mark on river gage readings were 48.6 in 1927 and 49.7 in 1932.=Flood of 1968

= The Ouachita River reached flood stage crest with a river gauge reading at Camden, Arkansas of 43.08 feet on May 17, 1968.=Flood of 2018

= The Ouachita River reached flood stage crest at 85.43 feet above sea level, about 20 feet above the normal water level of 65 feet at the Felsenthal lock and dam on March 11, 2018. The highest water level ever recorded at Felsenthal was 88.3 feet in 1945.Natural history

The river continues to be utilized for commercial navigation on a smaller scale than during its "

The river continues to be utilized for commercial navigation on a smaller scale than during its "steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. Steamboats sometimes use the ship prefix, prefix designation SS, S.S. or S/S ...

" days. It is fed by numerous small creeks containing endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

native fish such as killifish. Fishing remains popular in the river for black bass, white bass

The white bass, silver bass, or sand bass (''Morone chrysops'') is a freshwater fish of the temperate bass family Moronidae. commonly around 12-15 inches long. The species' main color is silver-white to pale green. Its back is dark, with white s ...

, bream

Bream ( ) are species of freshwater and marine fish belonging to a variety of genera including '' Abramis'' (e.g., ''A. brama'', the common bream), '' Acanthopagrus'', ''Argyrops'', '' Blicca'', '' Brama'', '' Chilotilapia'', ''Etelis'', '' L ...

, freshwater drum

The freshwater drum, ''Aplodinotus grunniens'', is a fish endemic to North and Central America. It is the only species in the genus ''Aplodinotus'', and is a member of the family Sciaenidae. It is the only North American member of the group that ...

, and gar. Concerns about airborne mercury contamination

Mercury is a chemical element with the symbol Hg and atomic number 80. It is also known as quicksilver and was formerly named hydrargyrum ( ) from the Greek words, ''hydor'' (water) and ''argyros'' (silver). A heavy, silvery d-block element, ...

in some areas discourage consumption of the fish for food. Fishing for rainbow trout

The rainbow trout (''Oncorhynchus mykiss'') is a species of trout native to cold-water tributaries of the Pacific Ocean in Asia and North America. The steelhead (sometimes called "steelhead trout") is an anadromous (sea-run) form of the coast ...

is popular in the tailwaters of Lakes Ouachita, Hamilton and Catherine in and around Hot Springs, Arkansas

Hot Springs is a resort city in the state of Arkansas and the county seat of Garland County. The city is located in the Ouachita Mountains among the U.S. Interior Highlands, and is set among several natural hot springs for which the city is n ...

.

The river is commercially navigable from Camden, Arkansas

Camden is a city in and the county seat of Ouachita County in the south-central part of the U.S. state of Arkansas. The city is located about 100 miles south of Little Rock. Situated on bluffs overlooking the Ouachita River, the city developed ...

, to its terminal point in Jonesville in Catahoula Parish in eastern Louisiana. Upstream of Camden, the river receives substantial recreational use.

The Ouachita is lined for most of its length with deep woods, including substantial wetland

A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). Flooding results in oxygen-free (Anoxic waters, anoxic) processes prevailing, especially in t ...

s. It has a scenic quality representative of the southwestern Arkansas and northern Louisiana region.

Lists

Major towns along the river are: *Hot Springs, Arkansas

Hot Springs is a resort city in the state of Arkansas and the county seat of Garland County. The city is located in the Ouachita Mountains among the U.S. Interior Highlands, and is set among several natural hot springs for which the city is n ...

* Malvern, Arkansas

Malvern is a city in and the county seat of Hot Spring County, Arkansas, United States. Founded as a railroad stop at the eastern edge of the Ouachita Mountains, the community's history and economy have been tied to available agricultural and min ...

* Arkadelphia, Arkansas

Arkadelphia is a city in Clark County, Arkansas, United States. As of the 2010 census, the population was 10,714. The city is the county seat of Clark County. It is situated at the foothills of the Ouachita Mountains. Two universities, Hender ...

* Camden, Arkansas

Camden is a city in and the county seat of Ouachita County in the south-central part of the U.S. state of Arkansas. The city is located about 100 miles south of Little Rock. Situated on bluffs overlooking the Ouachita River, the city developed ...

* Sterlington, Louisiana

Sterlington is a town in northern Ouachita Parish, Louisiana, United States, near the boundary with Union Parish. At the 2010 census, the population was 1,594. In the 2018 census estimates, the population rose to 2,724. In 2014, Sterlington was ...

* Monroe, Louisiana

Monroe (historically french: Poste-du-Ouachita) is the list of municipalities in Louisiana#List of Municipalities, eighth-largest city in the U.S. state of Louisiana, and parish seat of Ouachita Parish, Louisiana, Ouachita Parish. With a 2020 Unit ...

* West Monroe, Louisiana

* Columbia, Louisiana

Columbia is a town in, and the parish seat of, Caldwell Parish, Louisiana, United States. The population was 390 as of the 2010 census, down from 477 in 2000.

History

The land that became Columbia was first cleared by Daniel Humphries in 1827. ...

* Harrisonburg, Louisiana

Harrisonburg is a village in and the parish seat of Catahoula Parish, Louisiana, United States. The population was 348 as of the 2010 census, down from 746 in 2000.

Riley J. Wilson, who held Louisiana's 5th congressional district seat from 1 ...

* Jonesville, Louisiana

See also

* List of Arkansas rivers * List of Louisiana rivers * List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem)References

*William Least Heat-Moon, ''Roads to Quoz, An American Mosey'' (2008), . Section I – "Down an Ancient Valley" describes a trip down the Ouachita River valley.External links

Upper Ouachita River

Lower Ouachita River

Ouachita River Foundation

{{authority control Rivers of Arkansas Rivers of Louisiana Tributaries of the Red River of the South Rivers of Polk County, Arkansas Rivers of Garland County, Arkansas Rivers of Hot Spring County, Arkansas Rivers of Clark County, Arkansas Rivers of Ouachita County, Arkansas Rivers of Ashley County, Arkansas Rivers of Catahoula Parish, Louisiana Rivers of Ouachita Parish, Louisiana Rivers of Caldwell Parish, Louisiana Rivers of Concordia Parish, Louisiana