Ottoman Battleship Turgut Reis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SMS was one of the first ocean-going battleships of the

was the third of four s, the first

was the third of four s, the first

During the Boxer Uprising in 1900, Chinese nationalists laid siege to the foreign embassies in

During the Boxer Uprising in 1900, Chinese nationalists laid siege to the foreign embassies in

After watching Italy successfully seize Ottoman territory, the

After watching Italy successfully seize Ottoman territory, the

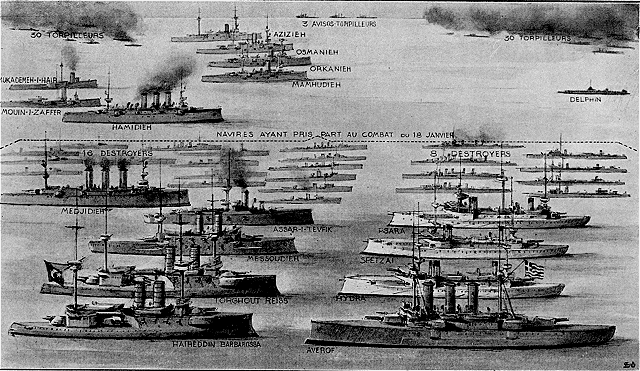

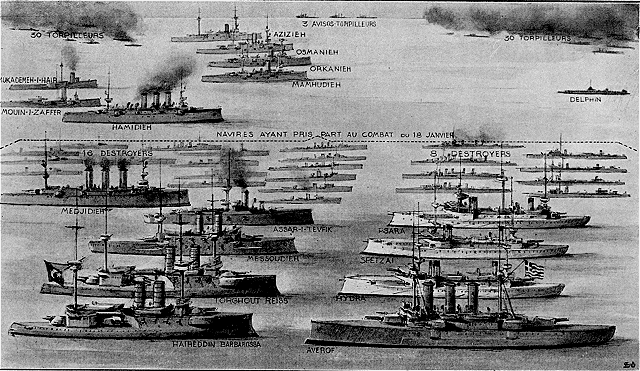

The Battle of Lemnos resulted from an Ottoman plan to lure the faster away from the Dardanelles. The protected cruiser evaded the Greek blockade and broke out into the Aegean Sea; the assumption was that the Greeks would dispatch to hunt down . Despite the threat to Greek lines of communication posed by the cruiser, the Greek commander refused to detach from its position. By mid-January, the Ottomans had learned that remained with the Greek fleet, and so (Captain) Ramiz Numan Bey, the Ottoman fleet commander, decided to attack the Greeks regardless. , , and other units of the Ottoman fleet departed the Dardanelles at 08:20 on the morning of 18 January, and sailed toward the island of Lemnos at a speed of . led the line of battleships, with a flotilla of torpedo boats on either side of the formation. , with the three -class ironclads and five destroyers trailing behind, intercepted the Ottoman fleet approximately from Lemnos. At 10:55, spotted the Greeks, and the fleet turned south to engage them.

A long-range artillery duel that lasted for two hours began at around 11:55, when the Ottoman fleet opened fire at a range of . They concentrated their fire on , which returned fire at 12:00. At 12:50, the Greeks attempted to cross the T of the Ottoman fleet, but the Ottoman line led by turned north to block the Greek maneuver. The Ottoman commander detached the old ironclad after she received a serious hit at 12:55. After suffered several hits that reduced her speed to , took the lead of the formation and Bey decided to break off the engagement. By 14:00, the Ottoman fleet reached the cover of the Dardanelles fortresses, forcing the Greeks to withdraw. Between and , the ships fired some 800 rounds, mostly of their main battery 28 cm guns but without success. During the battle, barbettes on both and her sister were disabled by gunfire, and both ships caught fire.

The Battle of Lemnos resulted from an Ottoman plan to lure the faster away from the Dardanelles. The protected cruiser evaded the Greek blockade and broke out into the Aegean Sea; the assumption was that the Greeks would dispatch to hunt down . Despite the threat to Greek lines of communication posed by the cruiser, the Greek commander refused to detach from its position. By mid-January, the Ottomans had learned that remained with the Greek fleet, and so (Captain) Ramiz Numan Bey, the Ottoman fleet commander, decided to attack the Greeks regardless. , , and other units of the Ottoman fleet departed the Dardanelles at 08:20 on the morning of 18 January, and sailed toward the island of Lemnos at a speed of . led the line of battleships, with a flotilla of torpedo boats on either side of the formation. , with the three -class ironclads and five destroyers trailing behind, intercepted the Ottoman fleet approximately from Lemnos. At 10:55, spotted the Greeks, and the fleet turned south to engage them.

A long-range artillery duel that lasted for two hours began at around 11:55, when the Ottoman fleet opened fire at a range of . They concentrated their fire on , which returned fire at 12:00. At 12:50, the Greeks attempted to cross the T of the Ottoman fleet, but the Ottoman line led by turned north to block the Greek maneuver. The Ottoman commander detached the old ironclad after she received a serious hit at 12:55. After suffered several hits that reduced her speed to , took the lead of the formation and Bey decided to break off the engagement. By 14:00, the Ottoman fleet reached the cover of the Dardanelles fortresses, forcing the Greeks to withdraw. Between and , the ships fired some 800 rounds, mostly of their main battery 28 cm guns but without success. During the battle, barbettes on both and her sister were disabled by gunfire, and both ships caught fire.

In the summer of 1914, when World War I broke out in Europe, the Ottomans initially remained neutral. In early November, the Black Sea Raid of the German battlecruiser , which had been transferred to the Ottoman navy and renamed , resulted in declarations of war by Russia, France, and Great Britain. By this time, was laid up off the

In the summer of 1914, when World War I broke out in Europe, the Ottomans initially remained neutral. In early November, the Black Sea Raid of the German battlecruiser , which had been transferred to the Ottoman navy and renamed , resulted in declarations of war by Russia, France, and Great Britain. By this time, was laid up off the

Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Kaise ...

. She was the third pre-dreadnought

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, protec ...

of the , which also included her sister ships , , and . was laid down in 1890 in the AG Vulcan

Aktien-Gesellschaft Vulcan Stettin (short AG Vulcan Stettin) was a German shipbuilding and locomotive building company. Founded in 1851, it was located near the former eastern German city of Stettin, today Polish Szczecin. Because of the limited ...

dockyard in Stettin, launched in 1891, and completed in 1894. The -class battleships were unique for their era in that they carried six large-caliber guns in three twin turrets, as opposed to four guns in two turrets, as was the standard in other navies.

served with I Division during the first decade of her service with the fleet. This period was generally limited to training exercises and goodwill visits to foreign ports. These training maneuvers were nevertheless very important to developing German naval tactical doctrine in the two decades before World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, especially under the direction of Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz (19 March 1849 – 6 March 1930) was a German grand admiral, Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperial Navy from 1897 until 1916. Prussi ...

. , along with her three sisters, saw only one major overseas deployment during this period, to China in 1900–1901, during the Boxer Uprising. The ship underwent a major modernization in 1904–1905.

In 1910, was sold to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

and renamed , after the famous 16th century Turkish admiral. The ship saw heavy service during the Balkan Wars, primarily providing artillery support to Ottoman ground forces. She also took part in two naval engagements with the Greek Navy

The Hellenic Navy (HN; el, Πολεμικό Ναυτικό, Polemikó Naftikó, War Navy, abbreviated ΠΝ) is the naval force of Greece, part of the Hellenic Armed Forces. The modern Greek navy historically hails from the naval forces of vari ...

—the Battle of Elli

The Battle of Elli ( el, Ναυμαχία της Έλλης, tr, İmroz Deniz Muharebesi) or the Battle of the Dardanelles took place near the mouth of the Dardanelles on as part of the First Balkan War between the fleets of the Kingdom of G ...

in December 1912, and the Battle of Lemnos the following month. Both battles were defeats for the Ottoman Navy. After the Ottoman Empire entered World War I, she supported the fortresses protecting the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

through mid-1915, and was decommissioned from August 1915 to the end of the war. She served as a training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house class ...

from 1924 to 1933, and a barracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for s ...

until 1950, when she was broken up

Ship-breaking (also known as ship recycling, ship demolition, ship dismantling, or ship cracking) is a type of ship disposal involving the breaking up of ships for either a source of Interchangeable parts, parts, which can be sold for re-use, ...

.

Design

was the third of four s, the first

was the third of four s, the first pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, protec ...

s of the (Imperial Navy). Prior to the ascension of Kaiser Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

to the German throne in June 1888, the German fleet had been largely oriented toward defense of the German coastline and Leo von Caprivi

Georg Leo Graf von Caprivi de Caprara de Montecuccoli (English: ''Count George Leo of Caprivi, Caprara, and Montecuccoli''; born Georg Leo von Caprivi; 24 February 1831 – 6 February 1899) was a German general and statesman who served as the cha ...

, chief of the (Imperial Naval Office), had ordered a number of coastal defense ship

Coastal defence ships (sometimes called coastal battleships or coast defence ships) were warships built for the purpose of coastal defence, mostly during the period from 1860 to 1920. They were small, often cruiser-sized warships that sacrifi ...

s in the 1880s. In August 1888, the Kaiser, who had a strong interest in naval matters, replaced Caprivi with (''VAdm''—Vice Admiral) Alexander von Monts

Alexander Graf von Monts de Mazin (born 9 August 1832 in Berlin; died 19 January 1889) was an officer in the Prussian Navy and later the German Imperial Navy. He saw action during the Second Schleswig War at the Battle of Jasmund on 17 March 18 ...

and instructed him to include four battleships in the 1889–1890 naval budget. Monts, who favored a fleet of battleships over the coastal defense strategy emphasized by his predecessor, cancelled the last four coastal defense ships authorized under Caprivi and instead ordered four battleships. Though they were the first modern battleships built in Germany, presaging the Tirpitz-era High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

, the authorization for the ships came as part of a construction program that reflected the strategic and tactical confusion of the 1880s caused by the (Young School).

, named for the Battle of Weissenburg of 1870, was long overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, an ...

, had a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of which was increased to with the addition of torpedo nets, and had a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

of forward and aft. She displaced as designed and up to at full combat load. She was equipped with two sets of 3-cylinder vertical triple expansion steam engines that each drove a screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

. Steam was provided by twelve transverse cylindrical Scotch marine boiler

A "Scotch" marine boiler (or simply Scotch boiler) is a design of steam boiler best known for its use on ships.

The general layout is that of a squat horizontal cylinder. One or more large cylindrical furnaces are in the lower part of the boiler ...

s. The ship's propulsion system was rated at and a top speed of . She had a maximum range of at a cruising speed of . Her crew numbered 38 officers and 530 enlisted men.

The ship was unusual for its time in that it possessed a broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

of six heavy guns in three twin gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s, rather than the four-gun main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

typical of contemporary battleships. The forward and after turrets carried 28 cm (11 in) K L/40 guns, while the amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17th ...

turret mounted a pair of 28 cm guns with shorter L/35 barrels. Her secondary armament

Secondary armament is a term used to refer to smaller, faster-firing weapons that were typically effective at a shorter range than the main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored ...

consisted of eight SK L/35 quick-firing guns mounted in casemates and eight 8.8 cm (3.45 in) SK L/30 quick-firing guns, also casemate mounted. s armament system was rounded out with six torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, all in above-water swivel mounts. Although the main battery was heavier than other capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic im ...

s of the period, the secondary armament was considered weak in comparison to other battleships.

was protected with nickel-steel Krupp armor

Krupp armour was a type of steel naval armour used in the construction of capital ships starting shortly before the end of the nineteenth century. It was developed by Germany's Krupp Arms Works in 1893 and quickly replaced Harvey armour as the p ...

, a new type of stronger steel. Her main belt armor

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

was thick in the central citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

I ...

that protected the ammunition magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combination ...

and machinery spaces. The deck was thick. The main battery barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protectio ...

s were protected with thick armor.

Service history

In German service

Construction – 1897

was the third of four ships of the class. Ordered as battleship "C", she waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

at the AG Vulcan

Aktien-Gesellschaft Vulcan Stettin (short AG Vulcan Stettin) was a German shipbuilding and locomotive building company. Founded in 1851, it was located near the former eastern German city of Stettin, today Polish Szczecin. Because of the limited ...

shipyard in Stettin in May 1890 under construction number 199. The third ship of the class to be launched, slid down the slipway

A slipway, also known as boat ramp or launch or boat deployer, is a ramp on the shore by which ships or boats can be moved to and from the water. They are used for building and repairing ships and boats, and for launching and retrieving small ...

on 30 June 1891. She was informally commissioned for sea trials

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and i ...

on 28 August 1894, which lasted until 24 September. The ship formally entered service on 10 October, under the command of then- (Captain at Sea) with (Corvette Captain Eduard von Capelle

Admiral Eduard von Capelle (10 October 1855 – 23 February 1931) was a German Imperial Navy officer from Celle. He served in the navy from 1872 until his retirement in October, 1918. During his career, Capelle served in the ''Reichsmarin ...

as the executive officer. then underwent further trials, which ended on 12 January 1895, after which she was assigned to I Division of the Maneuver Squadron, where she was initially occupied with individual training. Toward the end of May, more fleet maneuvers were carried out in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea, epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the ...

, concluding with a visit by the fleet to Kirkwall

Kirkwall ( sco, Kirkwaa, gd, Bàgh na h-Eaglaise, nrn, Kirkavå) is the largest town in Orkney, an archipelago to the north of mainland Scotland.

The name Kirkwall comes from the Norse name (''Church Bay''), which later changed to ''Kirkv ...

in Orkney. The squadron returned to Kiel in early June, where preparations were underway for the opening of the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal

The Kiel Canal (german: Nord-Ostsee-Kanal, literally "North- oEast alticSea canal", formerly known as the ) is a long freshwater canal in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. The canal was finished in 1895, but later widened, and links the ...

. Tactical exercises were carried out in Kiel Bay

The Bay of Kiel or Kiel Bay (, ; ) is a bay in the southwestern Baltic Sea, off the shores of Schleswig-Holstein in Germany and the islands of Denmark. It is connected with the Bay of Mecklenburg in the east, the Little Belt in the northwest, ...

in the presence of foreign delegations to the opening ceremony.

On 1 July, the German fleet began a major cruise into the Atlantic; on the return voyage in early August, the fleet stopped at the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a Counties of England, county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the List of islands of England#Largest islands, largest and List of islands of England#Mo ...

for the Cowes Regatta

Cowes Week ( ) is one of the longest-running regular regattas in the world. With 40 daily sailing races, up to 1,000 boats, and 8,000 competitors ranging from Olympic and world-class professionals to weekend sailors, it is the largest saili ...

. The fleet returned to Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsh ...

on 10 August and began preparations for the autumn maneuvers that would begin later that month. The first exercises began in the Helgoland Bight on 25 August. The fleet then steamed through the Skagerrak

The Skagerrak (, , ) is a strait running between the Jutland peninsula of Denmark, the southeast coast of Norway and the west coast of Sweden, connecting the North Sea and the Kattegat sea area through the Danish Straits to the Baltic Sea.

T ...

to the Baltic; heavy storms caused significant damage to many of the ships and the torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

capsized and sank in the storms—only three men were saved. The fleet stayed briefly in Kiel before resuming maneuvers, including live-fire exercises, in the Kattegat

The Kattegat (; sv, Kattegatt ) is a sea area bounded by the Jutlandic peninsula in the west, the Danish Straits islands of Denmark and the Baltic Sea to the south and the provinces of Bohuslän, Västergötland, Halland and Skåne in Sweden ...

and the Great Belt

The Great Belt ( da, Storebælt, ) is a strait between the major islands of Zealand (''Sjælland'') and Funen (''Fyn'') in Denmark. It is one of the three Danish Straits.

Effectively dividing Denmark in two, the Belt was served by the Great B ...

. The main maneuvers began on 7 September with a mock attack from Kiel toward the eastern Baltic. Subsequent maneuvers took place off the coast of Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

and in Danzig Bay. A fleet review for Kaiser Wilhelm II off Jershöft concluded the maneuvers on 14 September. The year 1896 followed much the same pattern as the previous year. Individual ship training was conducted through April, followed by squadron training in the North Sea in late April and early May. This included a visit to the Dutch ports of Vlissingen

Vlissingen (; zea, label= Zeelandic, Vlissienge), historically known in English as Flushing, is a municipality and a city in the southwestern Netherlands on the former island of Walcheren. With its strategic location between the Scheldt river ...

and Nieuwediep. Additional maneuvers, which lasted from the end of May to the end of July, took the squadron further north in the North Sea, frequently into Norwegian waters. The ships visited Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipality in Vestland county on the west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the second-largest city in Norway. The municipality covers and is on the peninsula o ...

from 11 to 18 May. During the maneuvers, Wilhelm II and the Chinese viceroy Li Hongzhang

Li Hongzhang, Marquess Suyi ( zh, t=李鴻章; also Li Hung-chang; 15 February 1823 – 7 November 1901) was a Chinese politician, general and diplomat of the late Qing dynasty. He quelled several major rebellions and served in important ...

observed a fleet review off Kiel. On 9 August, the training fleet assembled in Wilhelmshaven for the annual autumn fleet training.

and the rest of the fleet operated under the normal routine of individual and unit training in the first half of 1897. The typical routine was interrupted in early August when Wilhelm II and Augusta went to visit the Russian imperial court at Kronstadt

Kronstadt (russian: Кроншта́дт, Kronshtadt ), also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt or Kronštádt (from german: link=no, Krone for " crown" and ''Stadt'' for "city") is a Russian port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city ...

; both divisions of I Squadron were sent to accompany the Kaiser. They returned to Neufahrwasser in Danzig on 15 August, where the rest of the fleet joined them for the annual autumn maneuvers. These exercises reflected the tactical thinking of the new State Secretary of the (RMA—Imperial Navy Office), (''KAdm''—Rear Admiral) Alfred von Tirpitz, and the new commander of I Squadron, ''VAdm'' August von Thomsen. These new tactics stressed accurate gunnery, especially at longer ranges, though the necessities of the line-ahead formation led to tactical rigidity. Thomsen's emphasis on shooting created the basis for the excellent German gunnery during World War I. During the firing exercises, won the Kaiser's (Shooting Prize) for excellent accuracy in I Squadron. On the night of 21–22 August, the torpedo boat accidentally rammed and sank one of s barges, killing two men. The maneuvers were completed by 22 September in Wilhelmshaven. In early December, I Division conducted maneuvers in the Kattegat and the Skagerrak, though they were cut short due to crew shortages.

1898–1900

From 20 to 28 February, briefly served as the divisional flagship. The fleet followed the normal routine of individual and fleet training in 1898 without incident, and a voyage to the British Isles was also included. The fleet stopped in Queenstown, Greenock, and Kirkwall. The fleet assembled in Kiel on 14 August for the annual autumn exercises. The maneuvers included a mock blockade of the coast ofMecklenburg

Mecklenburg (; nds, label= Low German, Mękel(n)borg ) is a historical region in northern Germany comprising the western and larger part of the federal-state Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The largest cities of the region are Rostock, Schweri ...

and a pitched battle with an "Eastern Fleet" in the Danzig Bay. A severe storm, striking the fleet as it steamed back to Kiel, caused significant damage to many ships and sank the torpedo boat . The fleet then transited the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal and continued maneuvers in the North Sea. Training finished on 17 September in Wilhelmshaven. again won the Kaiser's (Shooting Prize) during the maneuvers. In December, I Division conducted artillery and torpedo training in Eckernförde Bay

Eckernförde Bay (german: Eckernförder Bucht; da, Egernførde Fjord or Egernfjord) is a firth and a branch of the Bay of Kiel between the Danish Wahld peninsula in the south and the Schwansen peninsula in the north in the Baltic Sea off the land ...

, followed by divisional training in the Kattegat and Skagerrak. During these maneuvers, the division visited Kungsbacka

Kungsbacka () (old da, Kongsbakke) is a locality and the seat of Kungsbacka Municipality in Halland County, Sweden, with 19,057 inhabitants in 2010.

It is one of the most affluent parts of Sweden, in part due to its simultaneous proximity to the ...

, Sweden, from 9 to 13 December. After returning to Kiel, the ships of I Division went into dock for their winter repairs.

On 5 April 1899, the ship participated in the celebrations commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Eckernförde

The Battle of Eckernförde was a Danish naval assault on Schleswig. The Danes were defeated and two of their ships were lost with the surviving crew being detained.

Carsen Jensen: ''Vi, de druknede'' (oversatt av Mie Hidle), Forlaget Press, (2 ...

during the First Schleswig War

The First Schleswig War (german: Schleswig-Holsteinischer Krieg) was a military conflict in southern Denmark and northern Germany rooted in the Schleswig-Holstein Question, contesting the issue of who should control the Duchies of Schleswi ...

. In May, I and II Divisions, along with the Reserve Division from the Baltic, went on a major cruise into the Atlantic. On the voyage out, I Division stopped in Dover and II Division went into Falmouth to restock their coal supplies. I Division then joined II Division at Falmouth on 8 May, and the two units then departed for the Bay of Biscay, arriving at Lisbon on 12 May. There, they met the British Channel Fleet of eight battleships and four armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

s. The German fleet then departed for Germany, stopping again in Dover on 24 May. There they participated in the naval review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

celebrating Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

's 80th birthday. The fleet returned to Kiel on 31 May.

In July, the fleet conducted squadron maneuvers in the North Sea, which included coast defense exercises with soldiers from the X Corps 10th Corps, Tenth Corps, or X Corps may refer to:

France

* 10th Army Corps (France)

* X Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* X Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army

* ...

. On 16 August, the fleet assembled in Danzig once again for the annual autumn maneuvers. The exercises started in the Baltic and on 30 August the fleet passed through the Kattegat and Skagerrak and steamed into the North Sea for further maneuvers in the German Bight

The German Bight (german: Deutsche Bucht; da, tyske bugt; nl, Duitse bocht; fry, Dútske bocht; ; sometimes also the German Bay) is the southeastern bight of the North Sea bounded by the Netherlands and Germany to the south, and Denmark and ...

, which lasted until 7 September. The third phase of the maneuvers took place in the Kattegat and the Great Belt from 8 to 26 September, when the maneuvers concluded and the fleet went into port for annual maintenance. The year 1900 began with the usual routine of individual and divisional exercises. In the second half of March, the squadrons met in Kiel, followed by torpedo and gunnery practice in April and a voyage to the eastern Baltic. From 7 to 26 May, the fleet went on a major training cruise to the northern North Sea, which included stops in Shetland from 12 to 15 May and in Bergen from 18 to 22 May. On 8 July, and the other ships of I Division were reassigned to II Division.

Boxer Uprising

During the Boxer Uprising in 1900, Chinese nationalists laid siege to the foreign embassies in

During the Boxer Uprising in 1900, Chinese nationalists laid siege to the foreign embassies in Peking

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

and murdered Baron Clemens von Ketteler

Clemens August Freiherr von Ketteler (22 November 1853 – 20 June 1900) was a German career diplomat. He was killed during the Boxer Rebellion.

Early life and career

Ketteler was born at Münster in western Germany on 22 November 1853 into ...

, the German minister. The widespread violence against Westerners in China led to an alliance between Germany and seven other Great Powers: the United Kingdom, Italy, Russia, Austria-Hungary, the United States, France, and Japan. Those Western soldiers in China at the time were too few in number to defeat the Boxers; in Peking there was a force of slightly more than 400 officers and infantry from the armies of the eight European powers. At the time, the primary German military force in China was the East Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron (german: Kreuzergeschwader / Ostasiengeschwader) was an Imperial German Navy cruiser squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the mid-1890s until 1914, when it was destroyed at the Battle of the ...

, which consisted of the protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of naval cruiser of the late-19th century, gained their description because an armoured deck offered protection for vital machine-spaces from fragments caused by shells exploding above them. Protected cruisers re ...

s , , and , the small cruisers and , and the gunboats and . There was also a German 500-man detachment in Taku; combined with the other nations' units, the force numbered some 2,100 men. Led by the British Admiral Edward Seymour, these men attempted to reach Peking but were forced to stop in Tientsin

Tianjin (; ; Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Tientsin (), is a municipality and a coastal metropolis in Northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the nine national central cities in Mainland China, with a total popul ...

due to heavy resistance. As a result, the Kaiser determined an expeditionary force would be sent to China to reinforce the East Asia Squadron. The expedition included and her three sisters, six cruisers, ten freighters, three torpedo boats, and six regiments of marines, under the command of (General Field Marshal) Alfred von Waldersee

Alfred Ludwig Heinrich Karl Graf von Waldersee (8 April 1832 in Potsdam5 March 1904 in Hanover) was a German field marshal (''Generalfeldmarschall'') who became Chief of the Imperial German General Staff.

Born into a prominent military family, ...

.

On 7 July, ''KAdm'' Richard von Geißler, the expeditionary force commander, reported that his ships were ready for the operation, and they left two days later. The four battleships and the aviso

An ''aviso'' was originally a kind of dispatch boat or "advice boat", carrying orders before the development of effective remote communication.

The term, derived from the Portuguese and Spanish word for "advice", "notice" or "warning", an ...

transited the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal and stopped in Wilhelmshaven to rendezvous with the rest of the expeditionary force. On 11 July, the force steamed out of the Jade Bight

The Jade Bight (or ''Jade Bay''; german: Jadebusen) is a bight or bay on the North Sea coast of Germany. It was formerly known simply as ''Jade'' or ''Jahde''. Because of the very low input of freshwater, it is classified as a bay rather than an ...

, bound for China. They stopped for coal at Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

on 17–18 July and passed through the Suez Canal on 26–27 July. More coal was taken on at Perim

Perim ( ar, بريم 'Barīm'', also called Mayyun in Arabic, is a volcanic island in the Strait of Mandeb at the south entrance into the Red Sea, off the south-west coast of Yemen and belonging to Yemen. It administratively belongs to Dhub ...

in the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

, and on 2 August the fleet entered the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by t ...

. On 10 August, the ships reached Colombo, Ceylon, and on 14 August they passed through the Strait of Malacca

The Strait of Malacca is a narrow stretch of water, 500 mi (800 km) long and from 40 to 155 mi (65–250 km) wide, between the Malay Peninsula (Peninsular Malaysia) to the northeast and the Indonesian island of Sumatra to the southwest, connec ...

. They arrived in Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

on 18 August and departed five days later, reaching Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delta i ...

on 28 August. Two days later, the expeditionary force stopped in the outer roadstead at Wusong

Wusong, formerly romanized as Woosung, is a subdistrict of Baoshan in northern Shanghai. Prior to the city's expansion, it was a separate port town located down the Huangpu River from Shanghai's urban core.

Name

Wusong is named for the Wus ...

, downriver from Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

. By the time the German fleet had arrived, the siege of Peking had already been lifted by forces from other members of the Eight-Nation Alliance that had formed to deal with the Boxers.

Since the situation had calmed, the four battleships were sent to either Hong Kong or Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole Nanban trade, port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hi ...

, Japan, in late 1900 and early 1901 for overhauls; went to Hong Kong, with the work lasting from 6 December 1900 to 3 January 1901. From 8 February to 23 March, she stopped in German Tsingtau

Qingdao (, also spelled Tsingtao; , Mandarin: ) is a major city in eastern Shandong Province. The city's name in Chinese characters literally means " azure island". Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, it is a major nodal city of the One Belt ...

, where she also conducted gunnery training. On 26 May, the German high command recalled the expeditionary force to Germany. The fleet took on supplies in Shanghai and departed Chinese waters on 1 June. The ships stopped in Singapore from 10 to 15 June and took on coal before proceeding to Colombo, where they stayed from 22 to 26 June. Steaming against the monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal osci ...

s forced the fleet to stop in Mahé, Seychelles

Mahé is the largest island of Seychelles, with an area of , lying in the northeast of the Seychellean nation in the Somali Sea part of the Indian Ocean. The population of Mahé was 77,000, as of the 2010 census. It contains the capital city ...

, to take on more coal. The ships then stopped for a day each to take on coal in Aden and Port Said. On 1 August they reached Cadiz, and then met with I Division and steamed back to Germany together. They separated after reaching Helgoland, and on 11 August, after reaching the Jade roadstead, the ships of the expeditionary force were visited by Admiral von Koester, who was now the Inspector General of the Navy. The following day the expeditionary fleet was dissolved. In the end, the operation cost the German government more than 100 million marks.

1901–1910

Following her return from China, was taken into the drydocks at the (Imperial Dockyard) in Wilhelmshaven for an overhaul. In late 1901, the fleet went on a cruise to Norway. The pattern of training for 1902 remained unchanged from previous years; I Squadron went on a major training cruise that started on 25 April. The squadron initially steamed to Norwegian waters, then rounded the northern tip of Scotland, and stopped in Irish waters. The ships returned to Kiel on 28 May. Before the start of the annual fleet maneuvers in August, was involved in an accident that damaged herram bow

A ram was a weapon fitted to varied types of ships, dating back to antiquity. The weapon comprised an underwater prolongation of the bow of the ship to form an armoured beak, usually between 2 and 4 meters (6–12 ft) in length. This would be dri ...

; to ready the ship for the exercises, wooden reinforcement beams were installed in the bow. After the maneuvers, she was decommissioned on 29 September, with the new battleship taking her place in the division.

The four -class battleships were taken out of service for a major reconstruction. During the modernization, a second conning tower was added in the aft superstructure, along with a gangway

Broadly speaking, a gangway is a passageway through which to enter or leave. Gangway may refer specifically refer to:

Passageways

* Gangway (nautical), a passage between the quarterdeck and the forecastle of a ship, and by extension, a passage th ...

. and the other ships had their boilers replaced with newer models, and also had their superstructure amidships reduced. The work included increasing the ship's coal storage capacity and adding a pair of 10.5 cm guns. The plans had initially called for the center 28 cm turret to be replaced with an armored battery of medium-caliber guns, but this proved to be prohibitively expensive. On 27 September 1904, was recommissioned, and replaced the old coastal defense ship in II Squadron. The two squadrons of the fleet ended the year with the usual training cruise into the Baltic, which took place uneventfully. The first half of 1905 similarly passed without incident for . On 12 July, the fleet began its annual summer cruise to northern waters; the ships stopped in Gothenburg from 20 to 24 July and Stockholm from 2 to 7 August. The trip ended two days later, and was followed by the autumn fleet maneuvers later that month. In December, the fleet took its usual training cruise in the Baltic.

The fleet conducted its normal routine of individual and unit training in 1906, interrupted only by a cruise to Norway from mid-July to early August. The annual autumn maneuvers occurred as usual. After the conclusion of the maneuvers, had her crew reduced on 28 September and she was transferred to the Reserve Formation of the North Sea. She participated in the 1907 fleet maneuvers, but was decommissioned on 27 September, though she was still formally assigned to the Reserve Formation. She was reactivated on 2 August 1910 to participate in the annual maneuvers with III Squadron, though the sale of and to the Ottoman Empire was announced just a few days later. On 6 August, she left the squadron and departed Wilhelmshaven on the 14th in company with . They arrived in the Ottoman Empire on 1 September.

In Ottoman service

In late 1909, the German military attache to the Ottoman Empire had begun a conversation with the Ottoman Navy about the possibility of selling German warships to the Ottomans to counter Greek naval expansion. After lengthy negotiations, including Ottoman attempts to buy one or more of the new battlecruisers , , and , the Germans offered to sell the four ships of the class at a cost of 10 million marks. The Ottomans chose to buy and , since they were the more advanced ships of the class. The two battleships were renamed after the famous 16th-century Ottoman admirals,Turgut Reis

Dragut ( tr, Turgut Reis) (1485 – 23 June 1565), known as "The Drawn Sword of Islam", was a Muslim Ottoman naval commander, governor, and noble, of Turkish or Greek descent. Under his command, the Ottoman Empire's maritime power was extend ...

and Hayreddin Barbarossa

Hayreddin Barbarossa ( ar, خير الدين بربروس, Khayr al-Din Barbarus, original name: Khiḍr; tr, Barbaros Hayrettin Paşa), also known as Hızır Hayrettin Pasha, and simply Hızır Reis (c. 1466/1478 – 4 July 1546), was an O ...

, respectively. They were transferred on 1 September 1910, and on 12 September the German formally struck them from the naval register

A Navy Directory, formerly the Navy List or Naval Register is an official list of naval officers, their ranks and seniority, the ships which they command or to which they are appointed, etc., that is published by the government or naval autho ...

, backdated to 31 July. The Ottoman Navy, however, had great difficulty equipping and ; the navy had to pull trained enlisted men from the rest of the fleet just to put together crews for them. Both vessels suffered from condenser troubles after they entered Ottoman service, which reduced their speed to .

Italo–Turkish War

A year later, on 29 September 1911, Italy declared war on the Ottoman Empire to seizeLibya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

. , along with and the obsolete central battery ironclad had been on a summer training cruise since July, and so were prepared for the conflict. The day before Italy declared war, the ships had left Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, bound for the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

. Unaware that a war had begun, they steamed slowly and conducted training maneuvers while en route, passing southwest of Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ge ...

. While off the island of Kos

Kos or Cos (; el, Κως ) is a Greek island, part of the Dodecanese island chain in the southeastern Aegean Sea. Kos is the third largest island of the Dodecanese by area, after Rhodes and Karpathos; it has a population of 36,986 (2021 census), ...

on 1 October, the ships received word of the Italian attack, prompting them to steam at full speed for the safety of the Dardanelles, arriving later that night. The following day, the ships proceeded to Constantinople for a refit after the training cruise. and sortied briefly on 4 October, but quickly returned to port without encountering any Italian vessels. During this period, the Italian fleet laid naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, any ...

s at the entrance to the Dardanelles in an attempt to prevent the Ottoman fleet from entering the Mediterranean. Maintenance work was completed by 12 October, at which point the fleet returned to Nagara inside the Dardanelles.

Since the fleet could not be used to challenge the significantly more powerful Italian (Royal Navy), and were primarily kept at Nagara to support the coastal fortifications defending the Dardanelles in the event that the Italian fleet attempted to force the straits. On 19 April 1912, elements of the Italian fleet bombarded the Dardanelles fortresses, but the Ottoman fleet did not mount a counterattack. The negative course of the war led many naval officers to join a coup against the Young Turk government; the officers commanding the fleet at Nagara threatened to bring the ships to Constantinople if their demands were not met. With tensions rising in the Balkans, the Ottoman government signed a peace treaty on 18 October, ending the war.

Balkan Wars

After watching Italy successfully seize Ottoman territory, the

After watching Italy successfully seize Ottoman territory, the Balkan League

The League of the Balkans was a quadruple alliance formed by a series of bilateral treaties concluded in 1912 between the Eastern Orthodox kingdoms of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, and directed against the Ottoman Empire, which at the ...

declared war on the Ottoman Empire in October 1912 to seize the remaining European portion of the Empire, starting the First Balkan War

The First Balkan War ( sr, Први балкански рат, ''Prvi balkanski rat''; bg, Балканска война; el, Αʹ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος; tr, Birinci Balkan Savaşı) lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and invo ...

. By this time, , as with most ships of the Ottoman fleet, was in a state of disrepair. Her rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, such as photography an ...

s and ammunition hoists had been removed, the pipes for her pumps were corroded, and the telephone lines no longer worked. On 7 October, the day before the Balkan League attacked, and were anchored off Haydarpaşa

Haydarpaşa is a neighborhood within the Kadıköy and Üsküdar districts on the Asian part of Istanbul, Turkey. Haydarpaşa is named after Ottoman Vizier Haydar Pasha. The place, on the coast of Sea of Marmara, borders to Harem in the northwes ...

, along with the cruisers and and several torpedo boats. Ten days later, the ships departed for İğneada

İğneada (Greek: Thynias) is a small town within the district of Demirköy, Kırklareli, Demirköy in Turkey's Kırklareli Province. It lies on the Black Sea coast and is approximately south of the Rezovo River, Mutludere river which forms the b ...

and the two battleships bombarded Bulgarian artillery positions near Varna

Varna may refer to:

Places Europe

*Varna, Bulgaria, a city in Bulgaria

**Varna Province

**Varna Municipality

** Gulf of Varna

**Lake Varna

**Varna Necropolis

*Vahrn, or Varna, a municipality in Italy

*Varniai, a city in Lithuania

* Varna (Šaba ...

two days thereafter. The ships were still suffering from boiler trouble. Both battleships took part in gunnery training in the Sea of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara,; grc, Προποντίς, Προποντίδα, Propontís, Propontída also known as the Marmara Sea, is an inland sea located entirely within the borders of Turkey. It connects the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea via t ...

on 3 November, but stopped after firing only a few salvos each, as their main battery mountings were not fully functional.

On 7 November, shelled Bulgarian troops around Tekirdağ

Tekirdağ (; see also its other names) is a city in Turkey. It is located on the north coast of the Sea of Marmara, in the region of East Thrace. In 2019 the city's population was 204,001.

Tekirdağ town is a commercial centre with a harbour ...

. On 17 November, she supported the Ottoman III Corps by bombarding the attacking Bulgarian forces. The ship was aided by artillery observers ashore. The battleship's gunnery was largely ineffective, though it provided a morale boost for the besieged Ottoman army dug in at Çatalca

Çatalca (Metrae; ) is a city and a rural district in Istanbul, Turkey. It is the largest district in Istanbul by area.

It is in East Thrace, on the ridge between the Marmara and the Black Sea. Most people living in Çatalca are either farmers o ...

. By 17:00, the Bulgarian infantry had largely been forced back to their starting positions, in part due to the psychological effect of the battleships' bombardment. On 22 November, sortied from the Bosporus

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern Tu ...

to cover the withdrawal of , which had been torpedoed by a Bulgarian torpedo boat earlier that morning.

=Battle of Elli

= In December 1912, the Ottoman fleet was reorganized into an armored division, which included as flagship, two destroyer divisions, and a fourth division composed of warships intended for independent operations. Over the next two months, the armored division attempted to break the Greek naval blockade of the Dardanelles, which resulted in two major naval engagements. The first, the Battle of Elli took place on 16 December 1912. The Ottomans attempted to launch an attack onImbros

Imbros or İmroz Adası, officially Gökçeada (lit. ''Heavenly Island'') since 29 July 1970,Alexis Alexandris, "The Identity Issue of The Minorities in Greece And Turkey", in Hirschon, Renée (ed.), ''Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1 ...

. The Ottoman fleet sortied from the Dardanelles at 09:30; the smaller craft remained at the mouth of the straits while the battleships sailed north, hugging the coast. The Greek flotilla, which included the armored cruiser and three s, sailing from the island of Lemnos

Lemnos or Limnos ( el, Λήμνος; grc, Λῆμνος) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos regional unit, which is part of the North Aegean region. The p ...

, altered course to the northeast to block the advance of the Ottoman battleships.

The Ottoman ships opened fire on the Greeks at 09:50, from a range of about . Five minutes later, crossed over to the other side of the Ottoman fleet, placing the Ottomans in the unfavorable position of being under fire from both sides. At 09:50 and under heavy pressure from the Greek fleet, the Ottoman ships completed a 16-point turn, which reversed their course, and headed for the safety of the straits. The turn was poorly conducted, and the ships fell out of formation, blocking each other's fields of fire. Around this time, received several hits, though they inflicted only minor damage to the ship's superstructure and guns. By 10:17, both sides had ceased firing and the Ottoman fleet withdrew into the Dardanelles. The ships reached port by 13:00 and transferred their casualties to the hospital ship

A hospital ship is a ship designated for primary function as a floating medical treatment facility or hospital. Most are operated by the military forces (mostly navies) of various countries, as they are intended to be used in or near war zones. I ...

.

=Battle of Lemnos

= The Battle of Lemnos resulted from an Ottoman plan to lure the faster away from the Dardanelles. The protected cruiser evaded the Greek blockade and broke out into the Aegean Sea; the assumption was that the Greeks would dispatch to hunt down . Despite the threat to Greek lines of communication posed by the cruiser, the Greek commander refused to detach from its position. By mid-January, the Ottomans had learned that remained with the Greek fleet, and so (Captain) Ramiz Numan Bey, the Ottoman fleet commander, decided to attack the Greeks regardless. , , and other units of the Ottoman fleet departed the Dardanelles at 08:20 on the morning of 18 January, and sailed toward the island of Lemnos at a speed of . led the line of battleships, with a flotilla of torpedo boats on either side of the formation. , with the three -class ironclads and five destroyers trailing behind, intercepted the Ottoman fleet approximately from Lemnos. At 10:55, spotted the Greeks, and the fleet turned south to engage them.

A long-range artillery duel that lasted for two hours began at around 11:55, when the Ottoman fleet opened fire at a range of . They concentrated their fire on , which returned fire at 12:00. At 12:50, the Greeks attempted to cross the T of the Ottoman fleet, but the Ottoman line led by turned north to block the Greek maneuver. The Ottoman commander detached the old ironclad after she received a serious hit at 12:55. After suffered several hits that reduced her speed to , took the lead of the formation and Bey decided to break off the engagement. By 14:00, the Ottoman fleet reached the cover of the Dardanelles fortresses, forcing the Greeks to withdraw. Between and , the ships fired some 800 rounds, mostly of their main battery 28 cm guns but without success. During the battle, barbettes on both and her sister were disabled by gunfire, and both ships caught fire.

The Battle of Lemnos resulted from an Ottoman plan to lure the faster away from the Dardanelles. The protected cruiser evaded the Greek blockade and broke out into the Aegean Sea; the assumption was that the Greeks would dispatch to hunt down . Despite the threat to Greek lines of communication posed by the cruiser, the Greek commander refused to detach from its position. By mid-January, the Ottomans had learned that remained with the Greek fleet, and so (Captain) Ramiz Numan Bey, the Ottoman fleet commander, decided to attack the Greeks regardless. , , and other units of the Ottoman fleet departed the Dardanelles at 08:20 on the morning of 18 January, and sailed toward the island of Lemnos at a speed of . led the line of battleships, with a flotilla of torpedo boats on either side of the formation. , with the three -class ironclads and five destroyers trailing behind, intercepted the Ottoman fleet approximately from Lemnos. At 10:55, spotted the Greeks, and the fleet turned south to engage them.

A long-range artillery duel that lasted for two hours began at around 11:55, when the Ottoman fleet opened fire at a range of . They concentrated their fire on , which returned fire at 12:00. At 12:50, the Greeks attempted to cross the T of the Ottoman fleet, but the Ottoman line led by turned north to block the Greek maneuver. The Ottoman commander detached the old ironclad after she received a serious hit at 12:55. After suffered several hits that reduced her speed to , took the lead of the formation and Bey decided to break off the engagement. By 14:00, the Ottoman fleet reached the cover of the Dardanelles fortresses, forcing the Greeks to withdraw. Between and , the ships fired some 800 rounds, mostly of their main battery 28 cm guns but without success. During the battle, barbettes on both and her sister were disabled by gunfire, and both ships caught fire.

=Subsequent operations

= On 8 February 1913, the Ottoman navy supported an amphibious assault atŞarköy

Şarköy, previously known by its Greek name Περίσταση (Peristasi), is a seaside town and district of Tekirdağ Province situated on the north coast of the Marmara Sea in Thrace in Turkey. Şarköy is 86 km west of the town of Tek ...

. and , along with two small cruisers provided artillery support to the right flank of the invading force once it went ashore. The ships were positioned about a kilometer off shore; was the second ship in the line, behind her sister . The Bulgarian army resisted fiercely, which ultimately forced the Ottoman army to retreat, though the withdrawal was successful in large part due to the gunfire support from and the rest of the fleet. During the battle, fired 225 rounds from her 10.5 cm guns and 202 shells from her 8.8 cm guns.

In March 1913, the ship returned to the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

to resume support of the Çatalca garrison, which was under renewed attacks by the Bulgarian army. On 26 March, the barrage of 28 and 10.5 cm shells fired by and assisted in the repelling of advance of the 2nd Brigade of the Bulgarian 1st Infantry Division. On 30 March, the left wing of the Ottoman line turned to pursue the retreating Bulgarians. Their advance was supported by both field artillery and the heavy guns of and the other warships positioned off the coast; the assault gained the Ottomans about by nightfall. In response, the Bulgarians brought the 1st Brigade to the front, which beat the Ottoman advance back to its starting position. On 11 April, and , supported by several smaller vessels, steamed to Çanakkale

Çanakkale (pronounced ), ancient ''Dardanellia'' (), is a city and seaport in Turkey in Çanakkale province on the southern shore of the Dardanelles at their narrowest point. The population of the city is 195,439 (2021 estimate).

Çanakkale is ...

to provide distant cover for a light flotilla conducting a sweep for Greek warships. The two sides clashed in an inconclusive engagement, and the main Ottoman fleet did not sortie before the two sides disengaged.

World War I

In the summer of 1914, when World War I broke out in Europe, the Ottomans initially remained neutral. In early November, the Black Sea Raid of the German battlecruiser , which had been transferred to the Ottoman navy and renamed , resulted in declarations of war by Russia, France, and Great Britain. By this time, was laid up off the

In the summer of 1914, when World War I broke out in Europe, the Ottomans initially remained neutral. In early November, the Black Sea Raid of the German battlecruiser , which had been transferred to the Ottoman navy and renamed , resulted in declarations of war by Russia, France, and Great Britain. By this time, was laid up off the Golden Horn

The Golden Horn ( tr, Altın Boynuz or ''Haliç''; grc, Χρυσόκερας, ''Chrysókeras''; la, Sinus Ceratinus) is a major urban waterway and the primary inlet of the Bosphorus in Istanbul, Turkey. As a natural estuary that connects with t ...

, worn out from heavy service during the Balkan Wars. Admiral , the head of the German naval mission to the Ottoman Empire, sent her and to Nagara to support the Dardanelles forts. They remained on station from 14 to 19 December, before returning to Constantinople for repairs and gunnery training. On 18 February 1915, they departed for the Dardanelles and anchored in their firing positions. During this period, their engines were stopped to preserve fuel, but after the threat of British submarines increased, they kept steam up in their engines to preserve their ability to take evasive action; the steamer was moored in front of the battleships as a floating barrage. By 11 March, the high command decided that only one ship should be kept on station at a time, alternating every five days, to allow the ships to replenish stores and ammunition.

On 18 March, was on station when the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

attempted to force the straits. She did not engage the Allied ships, as her orders were to open fire only in the event that the defenses were breached. This was in part due to a severe shortage of shells. On 25 April, both and were present to bombard the Allied troops that had landed at Gallipoli that day. At 07:30 that morning, the Australian submarine fired several torpedoes at but failed to score any hits. returned to Constantinople later that day as planned. While she was bombarding Allied positions on 5 June, one of s forward guns exploded; four men were killed and thirty-two were wounded. She returned to Constantinople for repairs, and the navy suspended bombardment operations— having suffered a similar accident on 25 April. On 12 August, was laid up at the Golden Horn after was torpedoed and sunk by a British submarine. At some point in 1915, some of s guns were removed and employed as coastal guns to shore up the defenses protecting the Dardanelles.

On 19 January 1918, and the light cruiser , which had also been transferred to Ottoman service under the name , sailed from the Dardanelles to attack several British monitors stationed outside. The ships quickly sank and before turning back to the safety of the Dardanelles. While en route, struck five mines and sank, while hit three mines and began to list to port. The ship's captain gave an incorrect order to the helmsman, which caused the ship to run aground. remained there for almost a week, until and several other vessels arrived on the scene on 22 January; the ships spent four days trying to free from the sand bank, including using the turbulence from their propellers to clear sand away from under the ship. By the morning of 26 January, came free from the sandbank and escorted her back into the Dardanelles.

was laid up again on 30 October 1918, and was refitted at the Gölcük Naval Shipyard

Gölcük Naval Shipyard ( tr, Gölcük Donanma Tersanesi) is a naval shipyard of the Turkish Navy within the Gölcük Naval Base on the east coast of the Sea of Marmara in Gölcük, Kocaeli. Established in 1926, the shipyard serves for the bu ...

from 1924 to 1925. After returning to service, she served as a stationary training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house class ...

based at Gölcük. At the time, she retained only two of her originally six 28 cm guns. Two main turrets were removed and installed as a part of the heavy coastal battery Turgut Reis, situated at the Asian coast of the Dardanelles Strait. Both turrets are preserved with their guns (two L/40 and two L/35). She was decommissioned in 1933 and was thereafter used as a barracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for s ...

for dockyard workers, a role she filled until 1950, when she began to be broken up

Ship-breaking (also known as ship recycling, ship demolition, ship dismantling, or ship cracking) is a type of ship disposal involving the breaking up of ships for either a source of Interchangeable parts, parts, which can be sold for re-use, ...

at Gölcük. By 1953, the ship had been broken down into two sections, and these were sold to be dismantled abroad. Demolition work was finally completed between 1956 and 1957.

Footnotes

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Weissenburg Brandenburg-class battleships Ships built in Stettin 1891 ships Boxer RebellionTurgut Reis

Dragut ( tr, Turgut Reis) (1485 – 23 June 1565), known as "The Drawn Sword of Islam", was a Muslim Ottoman naval commander, governor, and noble, of Turkish or Greek descent. Under his command, the Ottoman Empire's maritime power was extend ...