Otto Gessler on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

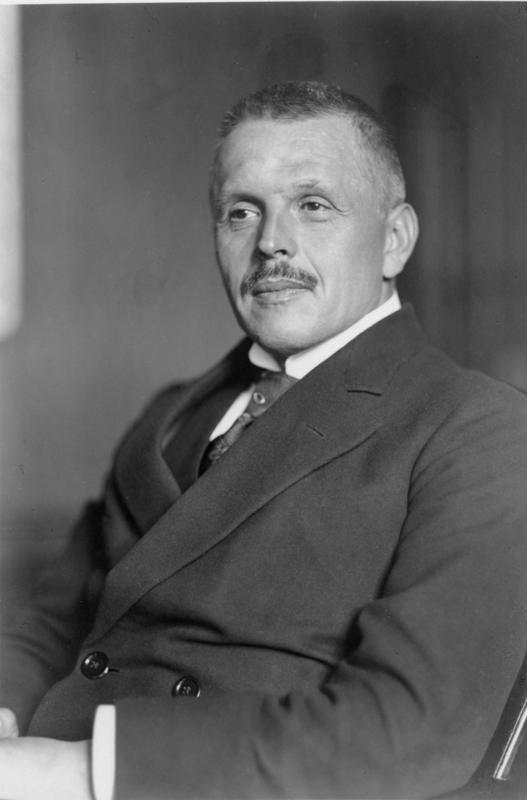

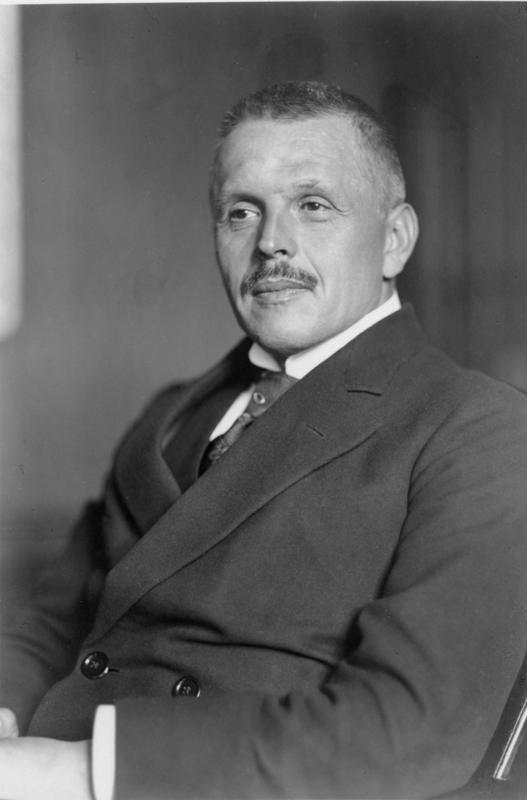

Otto Karl Gessler (or Geßler) (6 February 1875 – 24 March 1955) was a

Otto Karl Gessler (or Geßler) (6 February 1875 – 24 March 1955) was a

“Otto Geßler”

“in Parliamentary Data Bank of the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte in the Bavariathek. was included the resistance’s 1944 plans, and, in the event that the coup succeeded, was slated to be political commissioner in Military District VII (

Otto Karl Gessler (or Geßler) (6 February 1875 – 24 March 1955) was a

Otto Karl Gessler (or Geßler) (6 February 1875 – 24 March 1955) was a liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

German politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

during the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

. From 1910 until 1914, he was mayor of Regensburg

Regensburg or is a city in eastern Bavaria, at the confluence of the Danube, Naab and Regen rivers. It is capital of the Upper Palatinate subregion of the state in the south of Germany. With more than 150,000 inhabitants, Regensburg is the f ...

and from 1913 to 1919 mayor of Nuremberg. He served in numerous Weimar cabinets, most notably as ''Reichswehrminister'' (Minister of Defence) from 1920 to 1928.

Early life

Otto Karl Gessler was born on 6 February 1875 inLudwigsburg

Ludwigsburg (; Swabian: ''Ludisburg'') is a city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, about north of Stuttgart city centre, near the river Neckar. It is the largest and primary city of the Ludwigsburg district with about 88,000 inhabitants. It is ...

in the Kingdom of Württemberg

The Kingdom of Württemberg (german: Königreich Württemberg ) was a German state that existed from 1805 to 1918, located within the area that is now Baden-Württemberg. The kingdom was a continuation of the Duchy of Württemberg, which exist ...

as the son of the non-commissioned officer Otto Gessler and his wife Karoline (née Späth). He finished school in 1894 with the Abitur

''Abitur'' (), often shortened colloquially to ''Abi'', is a qualification granted at the end of secondary education in Germany. It is conferred on students who pass their final exams at the end of ISCED 3, usually after twelve or thirteen year ...

at the ''Humanistisches Gymnasium'' in Dillingen an der Donau

Dillingen or Dillingen an der Donau (Dillingen at the Danube) is a town in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany. It is the administrative center of the district of Dillingen.

Besides the town of Dillingen proper, the municipality encompasses the villages ...

. He studied law in Erlangen

Erlangen (; East Franconian German, East Franconian: ''Erlang'', Bavarian language, Bavarian: ''Erlanga'') is a Middle Franconian city in Bavaria, Germany. It is the seat of the administrative district Erlangen-Höchstadt (former administrative d ...

, Tübingen

Tübingen (, , Swabian: ''Dibenga'') is a traditional university city in central Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated south of the state capital, Stuttgart, and developed on both sides of the Neckar and Ammer rivers. about one in thr ...

and Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

and received his doctorate there in 1900. Initially, he worked for the judicial service of Leipzig. He then moved to Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

and served in various positions in the Bavarian justiciary (1903 clerk in the Bavarian Ministry of Justice, 1904 prosecutor in Straubing

Straubing () is an independent city in Lower Bavaria, southern Germany. It is seat of the district of Straubing-Bogen. Annually in August the Gäubodenvolksfest, the second largest fair in Bavaria, is held.

The city is located on the Danube form ...

, 1905 ''Gewerberichter'' in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

) before moving into public administration. In 1903, Gessler married Maria Helmschrott (died 1954).

Political career

Empire and Weimar Republic

Gessler was mayor ofRegensburg

Regensburg or is a city in eastern Bavaria, at the confluence of the Danube, Naab and Regen rivers. It is capital of the Upper Palatinate subregion of the state in the south of Germany. With more than 150,000 inhabitants, Regensburg is the f ...

from 1910 to 1914 and lord mayor of Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

from 1913 to 1919. Because of reduced mobility due to a handicap he did not serve during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. He successfully headed the town administration of Nuremberg in the war years and contributed to the fact that there were no leftist takeovers in Nuremberg and Franconia

Franconia (german: Franken, ; Franconian dialect: ''Franggn'' ; bar, Frankn) is a region of Germany, characterised by its culture and Franconian dialect (German: ''Fränkisch'').

The three administrative regions of Lower, Middle and Upper Fr ...

the immediate aftermath of the war during the German Revolution of 1918-19

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

.

Gessler was close to Friedrich Naumann

Friedrich Naumann (25 March 1860 – 24 August 1919) was a German Liberalism in Germany, liberal politician and Protestant parish pastor. In 1896, he founded the National-Social Association that sought to combine liberalism, nationalism and ...

and became one of the founders of the DDP in November 1918. In October 1919, he was appointed as ''Reichsminister für Wiederaufbau'' (Minister for Reconstruction) in the cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

of Gustav Bauer

Gustav Adolf Bauer (; 6 January 1870 – 16 September 1944) was a German Social Democratic Party leader and the chancellor of Germany from June 1919 to March 1920. He served as head of government for nine months. Prior to becoming head of gover ...

. Gessler was not a staunch supporter of the new republic, describing himself as a ''Vernunftsrepublikaner'' only.

After the Kapp-Lüttwitz Putsch

The Kapp Putsch (), also known as the Kapp–Lüttwitz Putsch (), was an attempted coup against the German national government in Berlin on 13 March 1920. Named after its leaders Wolfgang Kapp and Walther von Lüttwitz, its goal was to undo the ...

in March 1920 he assumed the office of ''Reichswehrminister'' (Minister of Defence) from Gustav Noske

Gustav Noske (9 July 1868 – 30 November 1946) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). He served as the first Minister of Defence (''Reichswehrminister'') of the Weimar Republic between 1919 and 1920. Noske has been a cont ...

who was forced to resign as a result of the putsch.

Gessler kept that position for the next eight years, despite numerous changes of government. As '' Reichswehrminister'' he worked closely with ''Chef der Heeresleitung'' Hans von Seeckt

Johannes "Hans" Friedrich Leopold von Seeckt (22 April 1866 – 27 December 1936) was a German military officer who served as Chief of Staff to August von Mackensen and was a central figure in planning the victories Mackensen achieved for Germany ...

in setting up the ''Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshaped ...

'' and turning it into a modern army. Gessler did not see his role as controlling the military, but rather in cooperating with the military command staff, which for its part viewed the Reichswehr's position as an independent and autonomous "state within the state". From 1920 to 1924, Gessler was also a member of the Reichstag.

In September 1923, the right-wing state government of Bavaria challenged the government in Berlin, resulting in a so-called "Reichsexekution

In German history, a ''Reichsexekution'' (sometimes "Reich execution" in English) was an imperial or federal intervention against a member state, using military force if necessary. The instrument of the ''Reichsexekution'' was constitutionally av ...

" against the state. President Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (; 4 February 187128 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first President of Germany (1919–1945), president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Eber ...

declared a state-of-emergency and, as Reichswehrminister, Gessler was vested with executive power. After the Hitler Putsch in November, Gessler transferred that power to von Seeckt. He helped in solving the crisis, by mediating between Ebert, chancellor Gustav Stresemann

Gustav Ernst Stresemann (; 10 May 1878 – 3 October 1929) was a German statesman who served as chancellor in 1923 (for 102 days) and as foreign minister from 1923 to 1929, during the Weimar Republic.

His most notable achievement was the reconci ...

and the military leadership. Later, Gessler created a new office, the ''Wehrmacht-Abteilung'', directly under the Reichswehrminister and thereby moved political power from the ''Heeresleitung'' to the Minister.

From October to December 1925, Gessler also served as provisional Minister of the Interior and in May 1926 was Vice-Chancellor of Germany for a few days. In January 1927, the DDP voted against working with the coalition of the cabinet of Wilhelm Marx

Wilhelm Marx (15 January 1863 – 5 August 1946) was a German lawyer, Catholic politician and a member of the Centre Party. He was the chancellor of Germany twice, from 1923 to 1925 and again from 1926 to 1928, and he also served briefly as the ...

. To retain his position as Minister of Defence, Gessler left the party.

After the accusation of financial anomalies in his ministry associated with the secret re-armament of the Reichswehr (also known as the Phoebus scandal) Gessler was forced to resign in January 1928.

From 1928 to 1933, he was president of the ''Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge'' (''German War Graves Commission

The German War Graves Commission ( in German) is responsible for the maintenance and upkeep of German war graves in Europe and North Africa. Its objectives are acquisition, maintenance and care of German war graves; tending to next of kin; youth ...

'') and of the ''Bund für die Erneuerung des Reiches''. From 1931 to 1933, Gessler was president of the ''Verein für das Deutschtum im Ausland'' (VDA, today ''Verein für Deutsche Kulturbeziehungen im Ausland

The Verein für Deutsche Kulturbeziehungen im Ausland (; "Association for German cultural relations abroad"), abbreviated VDA, is a German cultural organisation. During the Nazi era it was engaged in spying across the whole world, using Germa ...

'').

After 1933

After the ''Machtergreifung

Adolf Hitler's rise to power began in the newly established Weimar Republic in September 1919 when Hitler joined the '' Deutsche Arbeiterpartei'' (DAP; German Workers' Party). He rose to a place of prominence in the early years of the party. Be ...

'' of the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

in 1933, he retired from politics, in part due to ill health, and at first lived in seclusion at Lindenberg im Allgäu

Lindenberg im Allgäu (Low Alemannic German, Low Alemannic: ''Lindaberg'') is the second largest Town#Germany, town of the district of Lindau (district), Lindau in Bavaria, Germany. It is an acknowledged air health resort.

History

The town was fi ...

. Later in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, however, he became a member of the resistance group around Franz Sperr, had contacts with the Kreisau Circle

The Kreisau Circle (German: ''Kreisauer Kreis'', ) (1940–1944) was a group of about twenty-five German dissidents in Nazi Germany led by Helmuth James von Moltke, who met at his estate in the rural town of Kreisau, Silesia. The circle was com ...

,“in Parliamentary Data Bank of the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte in the Bavariathek. was included the resistance’s 1944 plans, and, in the event that the coup succeeded, was slated to be political commissioner in Military District VII (

Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

) in the shadow cabinet of General Ludwig Beck

Ludwig August Theodor Beck (; 29 June 1880 – 20 July 1944) was a German general and Chief of the German General Staff during the early years of the Nazi regime in Germany before World War II. Although Beck never became a member of the Na ...

and Carl Friedrich Goerdeler

Carl Friedrich Goerdeler (; 31 July 1884 – 2 February 1945) was a monarchist conservative German politician, executive, economist, civil servant and opponent of the Nazi regime. He opposed some anti-Jewish policies while he held office and was ...

. He was named in documents of Claus von Stauffenberg

Colonel Claus Philipp Maria Justinian Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg (; 15 November 1907 – 21 July 1944) was a German army officer best known for his failed attempt on 20 July 1944 to assassinate Adolf Hitler at the Wolf's Lair.

Despite ...

and was arrested two days after the assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler of 20 July 1944. He was detained and tortured at Ravensbrück concentration camp

Ravensbrück () was a German concentration camp exclusively for women from 1939 to 1945, located in northern Germany, north of Berlin at a site near the village of Ravensbrück (part of Fürstenberg/Havel). The camp memorial's estimated figure o ...

and then held at various Berlin prisons until his release in February 1945.

After the end of World War II, Gessler became involved in humanitarian organizations. In 1949, he became president of the Bavaria Red Cross (a post he retained until his death) and in 1950 president of the German Red Cross

The German Red Cross (german: Deutsches Rotes Kreuz ; DRK) is the national Red Cross Society in Germany.

With 4 million members, it is the third largest Red Cross society in the world. The German Red Cross offers a wide range of services within ...

. He was instrumental in the post-war reconstruction of the organization, serving as president until 1952.

From 1950 to 1955, Gessler was member of the Bavarian senate

The Bavarian Senate (German ''Bayerischer Senat'') was the corporative upper house, upper chamber of Free State of Bavaria, Bavaria's parliamentary system from 1946 to 1999, when it was abolished by a Referendum, popular vote (referendum) changi ...

.

Death and legacy

Gessler died on 24 March 1955 in Lindenberg im Allgäu. In 1958, his memoirs ''Reichswehrpolitik in der Weimarer Zeit'' were published posthumously. The hospital in Lindenberg is named for Gessler.Further reading

* Möllers, Heiner: ''Reichswehrminister Otto Geßler. Eine Studie zu "unpolitischer" Militärpolitik in der Weimarer Republik'' (= ''Europäische Hochschulschriften''. Reihe 3. ''Geschichte und ihre Hilfswissenschaften''. Bd. 794). Lang, Frankfurt am Main u.a. 1998, . *References

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Gessler, Otto 1875 births 1955 deaths People from Ludwigsburg German Roman Catholics German Democratic Party politicians Members of the Reichstag of the Weimar Republic Ministers of the Reichswehr Mayors of Regensburg German War Graves Commission People from the Kingdom of Württemberg Knights Commander of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Ravensbrück concentration camp survivors German Red Cross personnel