Orphic poems and rites on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Orpheus (;

It was believed by

It was believed by  Greeks of the

Greeks of the

1.3.2

"Orpheus also invented the mysteries of Dionysus, and having been torn in pieces by the Maenads he is buried in Pieria." and prescribed the mystery rites preserved in Orphic texts. Pindar and

7.7

"At the base of Olympus is a city Dium. And it has a village near by, Pimpleia. Here lived Orpheus, the Ciconian, it is said — a wizard who at first collected money from his music, together with his soothsaying and his celebration of the orgies connected with the mystic initiatory rites, but soon afterwards thought himself worthy of still greater things and procured for himself a throng of followers and power. Some, of course, received him willingly, but others, since they suspected a plot and violence, combined against him and killed him. And near here, also, is Leibethra." "Some, of course, received him willingly, but others, since they suspected a plot and violence, combined against him and killed him." He made money as a musician and "wizard" – Strabo uses (), also used by

sculptured representation of Orpheus

with the ship ''

On the writings of Orpheus,

On the writings of Orpheus,

According to

According to

The most famous story in which Orpheus figures is that of his wife

The most famous story in which Orpheus figures is that of his wife

According to a

According to a  Orpheus's

Orpheus's

A number of Greek religious poems in

A number of Greek religious poems in

review of this book

* Guthrie, William Keith Chambers, ''Orpheus and Greek Religion: a Study of the Orphic Movement'', 1935. * * Mitford, William, ''The History of Greece'', 1784. Cf. v.1, Chapter II, ''Religion of the Early Greeks''. * Moore, Clifford H., ''Religious Thought of the Greeks'', 1916. Kessinger Publishing (April 2003). * Ossoli, Margaret Fuller, ''Orpheus'', a sonnet about his trip to the underworld. *

"Orpheus"

* Taylor, Thomas ranslatorbr>''The Mystical Hymns of Orpheus''

1896. * West, Martin L., ''The Orphic Poems'', 1983. There is a sub-thesis in this work that early Greek religion was heavily influenced by Central Asian shamanistic practices. One major point of contact was the ancient Crimean city of

Greek Mythology Link, Orpheus

* ttp://www.prometheustrust.co.uk/html/5_-_hymns.html ''The Life and Theology of Orpheus'' by Thomas Taylor including several Orphic Hymns and their accompanying notes by Taylor

''Orphica'' in English and Greek (select resources)

Leibethra – The Tomb of Orpheus

(in Greek)

Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (ca. 400 images of Orpheus)

Greek Myth Comix: The Story of Orpheus

A detailed comic-strip retelling of Orpheus b

Greek Myth Comix

*

Orphicorum fragmenta

',

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied t ...

bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise t ...

, legendary musician and prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

in ancient Greek religion

Religious practices in ancient Greece encompassed a collection of beliefs, rituals, and mythology, in the form of both popular public religion and cult practices. The application of the modern concept of "religion" to ancient cultures has been ...

. He was also a renowned poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral or writte ...

and, according to the legend, travelled with Jason

Jason ( ; ) was an ancient Greek mythological hero and leader of the Argonauts, whose quest for the Golden Fleece featured in Greek literature. He was the son of Aeson, the rightful king of Iolcos. He was married to the sorceress Medea. He w ...

and the Argonauts

The Argonauts (; Ancient Greek: ) were a band of heroes in Greek mythology, who in the years before the Trojan War (around 1300 BC) accompanied Jason to Colchis in his quest to find the Golden Fleece. Their name comes from their ship, '' Argo'', ...

in search of the Golden Fleece

In Greek mythology, the Golden Fleece ( el, Χρυσόμαλλον δέρας, ''Chrysómallon déras'') is the fleece of the golden-woolled,, ''Khrusómallos''. winged ram, Chrysomallos, that rescued Phrixus and brought him to Colchis, where P ...

, and even descended into the Underworld

The underworld, also known as the netherworld or hell, is the supernatural world of the dead in various religious traditions and myths, located below the world of the living. Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underworld.

...

of Hades

Hades (; grc-gre, ᾍδης, Háidēs; ), in the ancient Greek religion and myth, is the god of the dead and the king of the underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea, although this also ...

, to recover his lost wife Eurydice

Eurydice (; Ancient Greek: Εὐρυδίκη 'wide justice') was a character in Greek mythology and the Auloniad wife of Orpheus, who tried to bring her back from the dead with his enchanting music.

Etymology

Several meanings for the name ...

.

Ancient Greek authors as Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

and Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

note Orpheus's Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied t ...

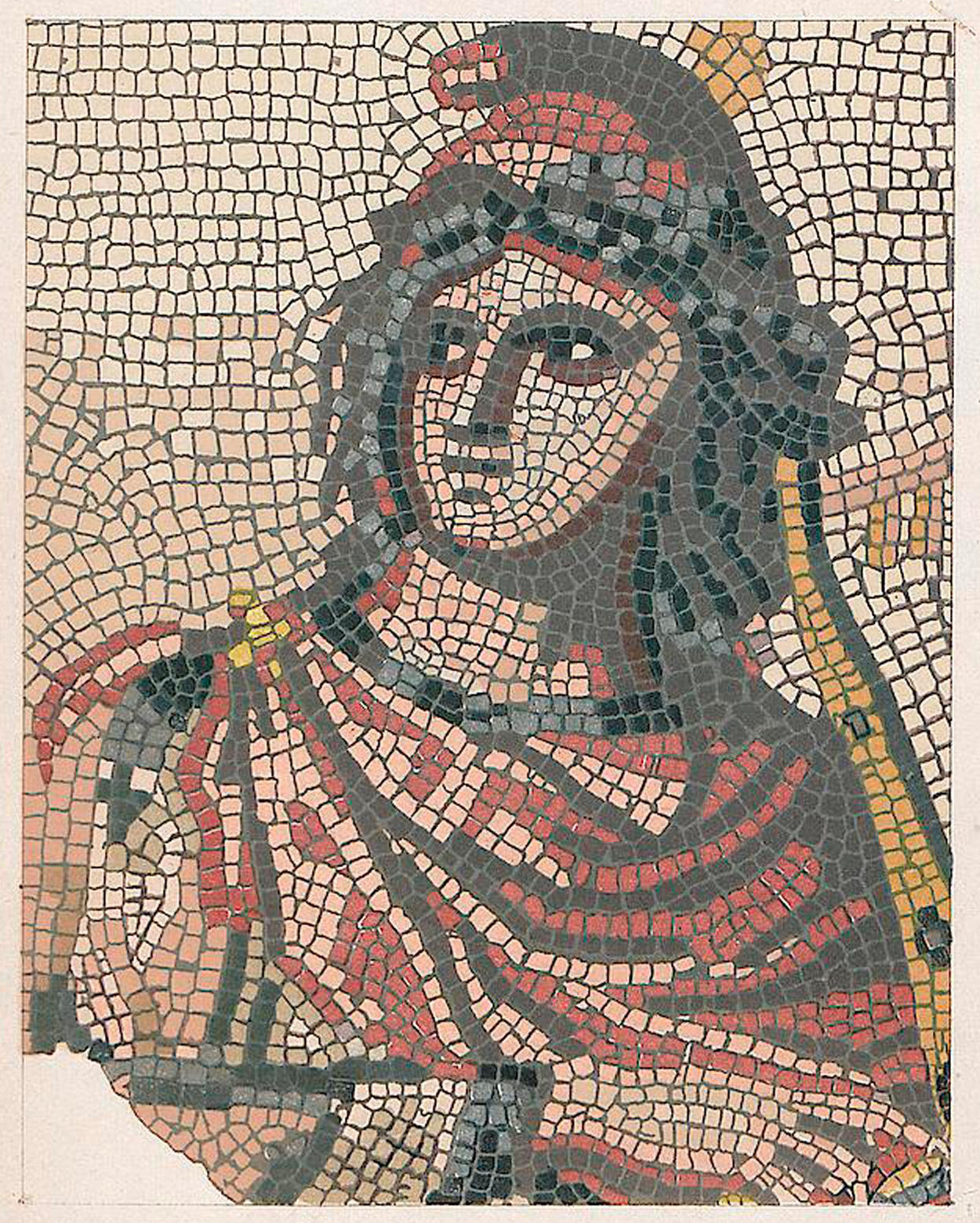

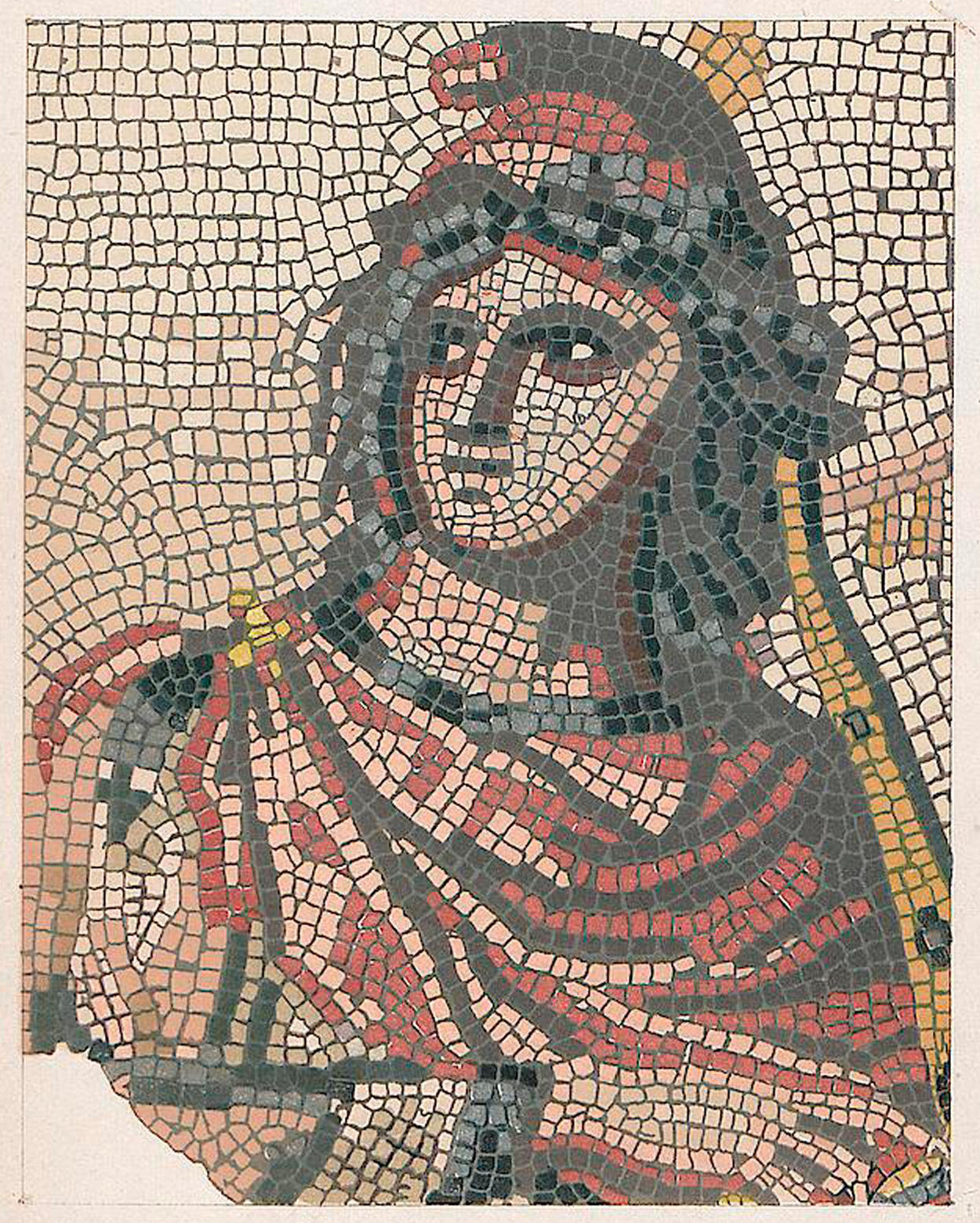

origins. The major stories about him are centered on his ability to charm all living things and even stones with his music (the usual scene in Orpheus mosaic

Orpheus mosaics are found throughout the Roman Empire, normally in large Roman villas. The scene normally shown is Orpheus playing his lyre, and attracting birds and animals of many species to gather around him. Orpheus was a popular subject in ...

s), his attempt to retrieve his wife Eurydice

Eurydice (; Ancient Greek: Εὐρυδίκη 'wide justice') was a character in Greek mythology and the Auloniad wife of Orpheus, who tried to bring her back from the dead with his enchanting music.

Etymology

Several meanings for the name ...

from the underworld

The underworld, also known as the netherworld or hell, is the supernatural world of the dead in various religious traditions and myths, located below the world of the living. Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underworld.

...

, and his death at the hands of the maenad

In Greek mythology, maenads (; grc, μαινάδες ) were the female followers of Dionysus and the most significant members of the Thiasus, the god's retinue. Their name literally translates as "raving ones". Maenads were known as Bassarids, ...

s of Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Romans ...

, who tired of his mourning for his late wife Eurydice. As an archetype of the inspired singer, Orpheus is one of the most significant figures in the reception

Reception is a noun form of ''receiving'', or ''to receive'' something, such as art, experience, information, people, products, or vehicles. It may refer to:

Astrology

* Reception (astrology), when a planet is located in a sign ruled by another p ...

of classical mythology

Classical mythology, Greco-Roman mythology, or Greek and Roman mythology is both the body of and the study of myths from the ancient Greeks and ancient Romans as they are used or transformed by cultural reception. Along with philosophy and polit ...

in Western culture

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

, portrayed or alluded to in countless forms of art and popular culture including poetry, film, opera, music, and painting.

For the Greeks, Orpheus was a founder and prophet of the so-called "Orphic" mysteries. He was credited with the composition of the ''Orphic Hymns

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with Jason ...

'' and the Orphic ''Argonautica

The ''Argonautica'' ( el, Ἀργοναυτικά , translit=Argonautika) is a Greek epic poem written by Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. The only surviving Hellenistic epic, the ''Argonautica'' tells the myth of the voyage of Jason a ...

''. Shrines containing purported relics

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains of a saint or the personal effects of the saint or venerated person preserved for purposes of veneration as a tangi ...

of Orpheus were regarded as oracle

An oracle is a person or agency considered to provide wise and insightful counsel or prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by deities. As such, it is a form of divination.

Description

The word '' ...

s.

Etymology

Several etymologies for the name ''Orpheus'' have been proposed. A probable suggestion is that it is derived from a hypotheticalPIE

A pie is a baked dish which is usually made of a pastry dough casing that contains a filling of various sweet or savoury ingredients. Sweet pies may be filled with fruit (as in an apple pie), nuts ( pecan pie), brown sugar ( sugar pie), swe ...

root 'orphan, servant, slave' and ultimately the verb root 'to change allegiance, status, ownership.' Cognates could include (; 'darkness')Cobb, Noel. ''Archetypal Imagination'', Hudson, New York: Lindisfarne Press, p. 240. and (; 'fatherless, orphan') from which comes English 'orphan' by way of Latin.

Fulgentius Fulgentius is a Latin male given name which means "bright, brilliant". It may refer to:

* Fabius Planciades Fulgentius (5th–6th century), Latin grammarian

*Saint Fulgentius of Ruspe (5th–6th century), bishop of Ruspe, North Africa, possi ...

, a mythographer of the late 5th to early 6th century AD, gave the unlikely etymology meaning "best voice," "Oraia-phonos".

Background

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

that Orpheus never existed. But to all other ancient writers, he was a real person, though living in remote antiquity. Most of them believed that he lived several generations before Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

. The earliest literary reference to Orpheus is a two-word fragment of the 6th century BC lyric poet Ibycus

Ibycus (; grc-gre, Ἴβυκος; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet, a citizen of Rhegium in Magna Graecia, probably active at Samos during the reign of the tyrant Polycrates and numbered by the scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria in the canonic ...

: ('Orpheus famous-of-name'). He is not mentioned by Homer or Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

. Most ancient sources accept his historical existence; Aristotle is an exception. Pindar

Pindar (; grc-gre, Πίνδαρος , ; la, Pindarus; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar is ...

calls Orpheus 'the father of songs' and identifies him as a son of the Thracian mythological king Oeagrus In Greek mythology, Oeagrus ( grc-gre, Οἴαγρος, Oíagros, of the wild sorb-apple) was a king of Thrace.

Biography

Kingdom

There are various versions as to where Oeagrus' domain was actually situated. In one version, he ruled over the E ...

and the Muse

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, the Muses ( grc, Μοῦσαι, Moûsai, el, Μούσες, Múses) are the inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. They were considered the source of the knowledge embodied in the ...

Calliope

In Greek mythology, Calliope ( ; grc, Καλλιόπη, Kalliópē, beautiful-voiced) is the Muse who presides over eloquence and epic poetry; so called from the ecstatic harmony of her voice. Hesiod and Ovid called her the "Chief of all Muses" ...

.

Greeks of the

Greeks of the Classical age

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

venerated Orpheus as the greatest of all poets and musicians; it was said that while Hermes

Hermes (; grc-gre, Ἑρμῆς) is an Olympian deity in ancient Greek religion and mythology. Hermes is considered the herald of the gods. He is also considered the protector of human heralds, travellers, thieves, merchants, and orato ...

had invented the lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

, Orpheus perfected it. Poets such as Simonides of Ceos

Simonides of Ceos (; grc-gre, Σιμωνίδης ὁ Κεῖος; c. 556–468 BC) was a Greek lyric poet, born in Ioulis on Ceos. The scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria included him in the canonical list of the nine lyric poets esteemed ...

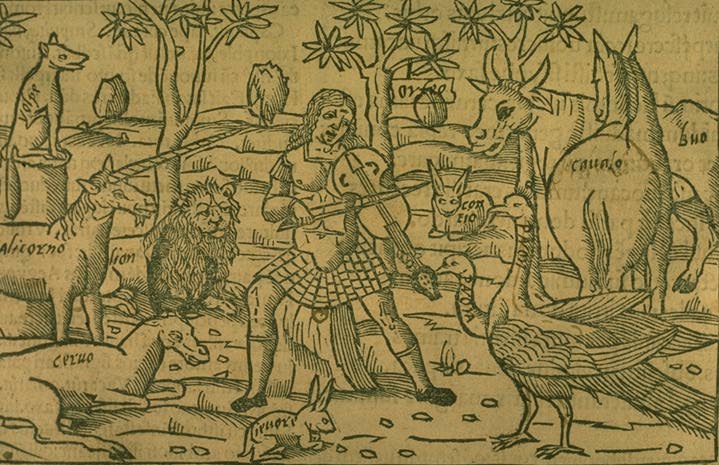

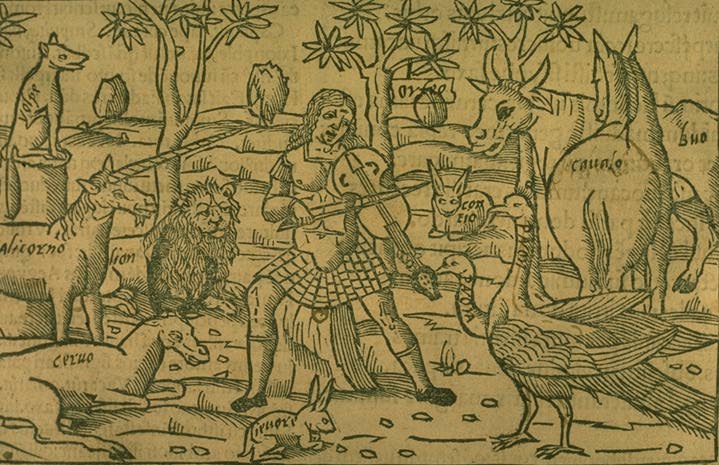

said that Orpheus's music and singing could charm the birds, fish and wild beasts, coax the trees and rocks into dance, and divert the course of rivers.

Orpheus was one of the handful of Greek hero

Hero cults were one of the most distinctive features of ancient Greek religion. In Homeric Greek, "hero" (, ) refers to the mortal offspring of a human and a god. By the historical period, however, the word came to mean specifically a ''dead'' ma ...

es to visit the Underworld

The underworld, also known as the netherworld or hell, is the supernatural world of the dead in various religious traditions and myths, located below the world of the living. Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underworld.

...

and return; his music and song had power even over Hades

Hades (; grc-gre, ᾍδης, Háidēs; ), in the ancient Greek religion and myth, is the god of the dead and the king of the underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea, although this also ...

. The earliest known reference to this descent to the underworld

A katabasis or catabasis ( grc, κατάβασις, from "down" and "go") is a journey to the underworld. Its original sense is usually associated with Greek mythology and Classical mythology more broadly, where the protagonist visits the Gree ...

is the painting by Polygnotus

Polygnotus ( el, Πολύγνωτος ''Polygnotos'') was an ancient Greek painter from the middle of the 5th century BC. Life

He was the son and pupil of Aglaophon. He was a native of Thasos, but was adopted by the Athenians, and admitted to ...

(5th century BC) described by Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may refer to:

*Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

*Pausanias of Sicily, physician of th ...

(2nd century AD), where no mention is made of Eurydice. Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful e ...

and Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

both refer to the story of his descent to recover his wife, but do not mention her name; a contemporary relief (about 400 BC) shows Orpheus and his wife with Hermes. The elegiac poet Hermesianax called her Agriope

''Aglossa'' is a genus of small moths belonging to the family Pyralidae. It was described by Pierre André Latreille in 1796. They are found mainly in western Eurasia, though some species have been introduced elsewhere.

This genus is remarkable ...

; and the first mention of her name in literature is in the ''Lament for Bion'' (1st century BC)

Some sources credit Orpheus with further gifts to humankind: medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

, which is more usually under the auspices of Asclepius

Asclepius (; grc-gre, Ἀσκληπιός ''Asklēpiós'' ; la, Aesculapius) is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Religion in ancient Greece, Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis (lover of ...

(Aesculapius) or Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

; writing, which is usually credited to Cadmus

In Greek mythology, Cadmus (; grc-gre, Κάδμος, Kádmos) was the legendary Phoenician founder of Boeotian Thebes. He was the first Greek hero and, alongside Perseus and Bellerophon, the greatest hero and slayer of monsters before the da ...

; and agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

, where Orpheus assumes the Eleusinian

Elefsina ( el, Ελευσίνα ''Elefsina''), or Eleusis (; Ancient Greek: ''Eleusis'') is a suburban city and municipality in the West Attica regional unit of Greece. It is situated about northwest from the centre of Athens and is part of i ...

role of Triptolemus

In Greek mythology, Triptolemus ( el, Τριπτόλεμος, ''Triptólemos'', lit. "threefold warrior"; also known as Buzyges) is a figure connected with the goddess Demeter of the Eleusinian Mysteries. He was either a mortal prince, the el ...

as giver of Demeter's knowledge to humankind. Orpheus was an augur

An augur was a priest and official in the classical Roman world. His main role was the practice of augury, the interpretation of the will of the gods by studying the flight of birds. Determinations were based upon whether they were flying i ...

and seer; he practiced magical arts and astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of Celestial o ...

, founded cults to Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

and Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Romans ...

Apollodorus1.3.2

"Orpheus also invented the mysteries of Dionysus, and having been torn in pieces by the Maenads he is buried in Pieria." and prescribed the mystery rites preserved in Orphic texts. Pindar and

Apollonius of Rhodes

Apollonius of Rhodes ( grc, Ἀπολλώνιος Ῥόδιος ''Apollṓnios Rhódios''; la, Apollonius Rhodius; fl. first half of 3rd century BC) was an ancient Greek author, best known for the ''Argonautica'', an epic poem about Jason and t ...

place Orpheus as the harpist and companion of Jason and the Argonauts. Orpheus had a brother named Linus

Linus, a male given name, is the Latin form of the Greek name ''Linos''. It's a common given name in Sweden. The origin of the name is unknown although the name appears in antiquity both as a musician who taught Apollo and as a son of Apollo who di ...

, who went to Thebes and became a Theban. He is claimed by Aristophanes and Horace to have taught cannibals to subsist on fruit, and to have made lions and tigers obedient to him. Horace believed, however, that Orpheus had only introduced order and civilization to savages.

Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

(64 BC – c. AD 24) presents Orpheus as a mortal, who lived and died in a village close to Olympus.Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

7.7

"At the base of Olympus is a city Dium. And it has a village near by, Pimpleia. Here lived Orpheus, the Ciconian, it is said — a wizard who at first collected money from his music, together with his soothsaying and his celebration of the orgies connected with the mystic initiatory rites, but soon afterwards thought himself worthy of still greater things and procured for himself a throng of followers and power. Some, of course, received him willingly, but others, since they suspected a plot and violence, combined against him and killed him. And near here, also, is Leibethra." "Some, of course, received him willingly, but others, since they suspected a plot and violence, combined against him and killed him." He made money as a musician and "wizard" – Strabo uses (), also used by

Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, Σοφοκλῆς, , Sophoklễs; 497/6 – winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or co ...

in ''Oedipus Tyrannus

''Oedipus Rex'', also known by its Greek title, ''Oedipus Tyrannus'' ( grc, Οἰδίπους Τύραννος, ), or ''Oedipus the King'', is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles that was first performed around 429 BC. Originally, to the ancient Gr ...

'' to characterize Tiresias

In Greek mythology, Tiresias (; grc, Τειρεσίας, Teiresías) was a blind prophet of Apollo in Thebes, famous for clairvoyance and for being transformed into a woman for seven years. He was the son of the shepherd Everes and the nymph ...

as a trickster with an excessive desire for possessions. () most often meant charlatan

A charlatan (also called a swindler or mountebank) is a person practicing quackery or a similar confidence trick in order to obtain money, power, fame, or other advantages through false pretenses, pretense or deception. Synonyms for ''charlatan ...

and always had a negative connotation. Pausanias writes of an unnamed Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

who considered Orpheus a (), i. e., magician.

"Orpheus...is repeatedly referred to by Euripides, in whom we find the first allusion to the connection of Orpheus with Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Romans ...

and the infernal regions: he speaks of him as related to the Muses

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, the Muses ( grc, Μοῦσαι, Moûsai, el, Μούσες, Múses) are the inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. They were considered the source of the knowledge embodied in the p ...

('' Rhesus'' 944, 946); mentions the power of his song over rocks, trees, and wild beasts (''Medea

In Greek mythology, Medea (; grc, Μήδεια, ''Mēdeia'', perhaps implying "planner / schemer") is the daughter of King Aeëtes of Colchis, a niece of Circe and the granddaughter of the sun god Helios. Medea figures in the myth of Jason an ...

'' 543, ''Iphigenia in Aulis

''Iphigenia in Aulis'' or ''Iphigenia at Aulis'' ( grc, Ἰφιγένεια ἐν Αὐλίδι, Īphigéneia en Aulídi; variously translated, including the Latin ''Iphigenia in Aulide'') is the last of the extant works by the playwright Euripide ...

'' 1211, ''Bacchae

''The Bacchae'' (; grc-gre, Βάκχαι, ''Bakchai''; also known as ''The Bacchantes'' ) is an ancient Greek tragedy, written by the Athenian playwright Euripides during his final years in Macedonia, at the court of Archelaus I of Macedon. ...

'' 561, and a jocular allusion in ''Cyclops

In Greek mythology and later Roman mythology, the Cyclopes ( ; el, Κύκλωπες, ''Kýklōpes'', "Circle-eyes" or "Round-eyes"; singular Cyclops ; , ''Kýklōps'') are giant one-eyed creatures. Three groups of Cyclopes can be distinguish ...

'' 646); refers to his charming the infernal powers (''Alcestis

Alcestis (; Ancient Greek: Ἄλκηστις, ') or Alceste, was a princess in Greek mythology, known for her love of her husband. Her life story was told by pseudo-Apollodorus in his '' Bibliotheca'', and a version of her death and return from ...

'' 357); connects him with Bacchanalian orgies ( ''Hippolytu''s 953); ascribes to him the origin of sacred mysteries ('' Rhesus'' 943), and places the scene of his activity among the forests of Olympus (''Bacchae

''The Bacchae'' (; grc-gre, Βάκχαι, ''Bakchai''; also known as ''The Bacchantes'' ) is an ancient Greek tragedy, written by the Athenian playwright Euripides during his final years in Macedonia, at the court of Archelaus I of Macedon. ...

'' 561.)" "Euripides lsobrought Orpheus into his play ''Hypsipyle'', which dealt with the Lemnian episode of the Argonautic voyage; Orpheus there acts as coxswain, and later as guardian in Thrace of Jason's children by Hypsipyle."

"He is mentioned once only, but in an important passage, by Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or ( grc, δῆμος, plural: demoi, δημοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Athens and other city-states ...

(''Frogs

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely carnivorous group of short-bodied, tailless amphibians composing the order Anura (ανοὐρά, literally ''without tail'' in Ancient Greek). The oldest fossil "proto-frog" ''Triadobatrachus'' is ...

'' 1032), who enumerates, as the oldest poets, Orpheus, Musaeus Musaeus, Musaios ( grc, Μουσαῖος) or Musäus may refer to:

Greek poets

* Musaeus of Athens, legendary polymath, considered by the Greeks to be one of their earliest poets (mentioned by Socrates in Plato's Apology)

* Musaeus of Ephesus, liv ...

, Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

, and Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, and makes Orpheus the teacher of religious initiations and of abstinence from murder..."

"Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

('' Apology'', ''Protagoras

Protagoras (; el, Πρωταγόρας; )Guthrie, p. 262–263. was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher and rhetorical theorist. He is numbered as one of the sophists by Plato. In his dialogue '' Protagoras'', Plato credits him with inventing the r ...

''),...frequently refers to Orpheus, his followers, and his works. He calls him the son of Oeagrus (''Symposium

In ancient Greece, the symposium ( grc-gre, συμπόσιον ''symposion'' or ''symposio'', from συμπίνειν ''sympinein'', "to drink together") was a part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was acc ...

''), mentions him as a musician and inventor ''(Ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conven ...

'' and ''Laws

Law is a set of rules that are created and are law enforcement, enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. ...

'' bk 3.), refers to the miraculous power of his lyre ''(Protagora''s), and gives a singular version of the story of his descent into Hades: the gods, he says, imposed upon the poet, by showing him only a phantasm of his lost wife, because he had not the courage to die, like Alcestis, but contrived to enter Hades alive, and, as a further punishment for his cowardice, he met his death at the hands of women (''Symposium

In ancient Greece, the symposium ( grc-gre, συμπόσιον ''symposion'' or ''symposio'', from συμπίνειν ''sympinein'', "to drink together") was a part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was acc ...

''.)"

"Earlier than the literary references is sculptured representation of Orpheus

with the ship ''

Argo

In Greek mythology the ''Argo'' (; in Greek: ) was a ship built with the help of the gods that Jason and the Argonauts sailed from Iolcos to Colchis to retrieve the Golden Fleece. The ship has gone on to be used as a motif in a variety of sour ...

'', found at Delphi, said to be of the sixth century BC."

Four other people are traditionally called Orpheus: "The second Orpheus was an Arcadian, or, according to others, a Ciconian

The Cicones (; ) or Ciconians were a Homeric ThracianHerodotus, ''The Histories'' (Penguin Classics), edd. John M. Marincola and Aubery de Selincourt, 2003, p. 452 (I10): "The Thracian tribes lying along his route were the Paeti, Cicones, Biston ...

, from the Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied t ...

Bisaltia

Bisaltia ( el, Βισαλτία) or Bisaltica was an ancient country which was bordered by Sintice on the north, Crestonia on the west, Mygdonia on the south and was separated by Odomantis on the north-east and Edonis on the south-east by river ...

, and is said to be more ancient than Homer and the Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and has ...

. He composed fabulous figments called mythpoeai and epigrams. The third Orpheus was of Odrysius, a city of Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

, near the river Hebrus; but Dionysius

The name Dionysius (; el, Διονύσιος ''Dionysios'', "of Dionysus"; la, Dionysius) was common in classical and post-classical times. Etymologically it is a nominalized adjective formed with a -ios suffix from the stem Dionys- of the name ...

in Suidas

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; grc-x-medieval, Σοῦδα, Soûda; la, Suidae Lexicon) is a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas (Σούδας) or Souidas ...

denies his existence. The fourth Orpheus was of Crotonia; flourished in the time of Pisistratus, about the fiftieth Olympiad, and is, I have no doubt, the same with Onomacritus

Onomacritus ( grc-gre, Ὀνομάκριτος; c. 530 – c. 480 BCE), also known as Onomacritos or Onomakritos, was a Greek chresmologue, or compiler of oracles, who lived at the court of the tyrant Pisistratus in Athens. He is said to have pre ...

, who changed the dialect of these hymns. He wrote Decennalia, and in the opinion of Gyraldlus the Argonautics, which are now extant under the name of Orpheus, with other writings called Orphical, but which according to Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

some ascribe to Cecrops

In Greek mythology, Cecrops ( /ˈsiːkrɒps/; Ancient Greek: Κέκροψ, ''Kékrops''; ''gen''.: Κέκροπος) may refer to two legendary kings of Athens:

* Cecrops I, the first king of Athens.

* Cecrops II, son of Pandion I, king of ...

the Pythagorean. But the last Orpheus he fifth

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

was Camarinseus, a most excellent versifier; and the same, according to Gyraldus, whose descent into Hades is so universally known."

Writings

On the writings of Orpheus,

On the writings of Orpheus, Freeman

Freeman, free men, or variant, may refer to:

* a member of the Third Estate in medieval society (commoners), see estates of the realm

* Freeman, an apprentice who has been granted freedom of the company, was a rank within Livery companies

* Free ...

, in the 1946 edition of ''The Pre- Socratic Philosophers'' pp. 4–8, writes:

"In the fifth and fourth centuries BC, there existed a collection of hexametric

Hexameter is a metrical line of verses consisting of six feet (a "foot" here is the pulse, or major accent, of words in an English line of poetry; in Greek and Latin a "foot" is not an accent, but describes various combinations of syllables). It w ...

poems known as Orphic

Orphism (more rarely Orphicism; grc, Ὀρφικά, Orphiká) is the name given to a set of religious beliefs and practices originating in the ancient Greek and Hellenistic world, associated with literature ascribed to the mythical poet Orpheus ...

, which were the accepted authority of those who followed the Orphic way of life, and were by them attributed to Orpheus himself. Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

several times quotes lines from this collection; he refers in the ''Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

'' to a "mass of books of Musaeus Musaeus, Musaios ( grc, Μουσαῖος) or Musäus may refer to:

Greek poets

* Musaeus of Athens, legendary polymath, considered by the Greeks to be one of their earliest poets (mentioned by Socrates in Plato's Apology)

* Musaeus of Ephesus, liv ...

and Orpheus", and in the ''Laws

Law is a set of rules that are created and are law enforcement, enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. ...

'' to the hymns of Thamyris

In Greek mythology, Thamyris (Ancient Greek: Θάμυρις, ''Thámuris'') was a Thracian singer. He is notable in Greek mythology for reportedly being a lover of Hyacinth and thus to have been the first male to have loved another male, but when ...

and Orpheus, while in the ''Ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conven ...

'' he groups Orpheus with Musaeus and Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

as the source of inspiration of epic poets and elocutionists. Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful e ...

in the '' Hippolytus'' makes Theseus

Theseus (, ; grc-gre, Θησεύς ) was the mythical king and founder-hero of Athens. The myths surrounding Theseus his journeys, exploits, and friends have provided material for fiction throughout the ages.

Theseus is sometimes describe ...

speak of the "turgid outpourings of many treatises", which have led his son to follow Orpheus and adopt the Bacchic

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Romans ...

religion. Alexis Alexis may refer to:

People Mononym

* Alexis (poet) ( – ), a Greek comic poet

* Alexis (sculptor), an ancient Greek artist who lived around the 3rd or 4th century BC

* Alexis (singer) (born 1968), German pop singer

* Alexis (comics) (1946–1977 ...

, the fourth century comic poet, depicting Linus offering a choice of books to Heracles

Heracles ( ; grc-gre, Ἡρακλῆς, , glory/fame of Hera), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adoptive ...

, mentions "Orpheus, Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

, tragedies, Choerilus, Homer, Epicharmus

Epicharmus of Kos or Epicharmus Comicus or Epicharmus Comicus Syracusanus ( grc-gre, Ἐπίχαρμος ὁ Κῷος), thought to have lived between c. 550 and c. 460 BC, was a Greek dramatist and philosopher who is often credited with ...

". Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

did not believe that the poems were by Orpheus; he speaks of the "so-called Orphic epic", and Philoponus

John Philoponus (Greek: ; ; c. 490 – c. 570), also known as John the Grammarian or John of Alexandria, was a Byzantine Greek philologist, Aristotelian commentator, Christian theologian and an author of a considerable number of philosophical tre ...

(seventh century AD) commenting on this expression, says that in the ''De Philosophia'' (now lost) Aristotle directly stated his opinion that the poems were not by Orpheus. Philoponus adds his own view that the doctrines were put into epic verse by Onomacritus

Onomacritus ( grc-gre, Ὀνομάκριτος; c. 530 – c. 480 BCE), also known as Onomacritos or Onomakritos, was a Greek chresmologue, or compiler of oracles, who lived at the court of the tyrant Pisistratus in Athens. He is said to have pre ...

. Aristotle when quoting the Orphic cosmological doctrines attributes them to "the ''theologoi''", "the ancient poets", "those who first theorized about the gods".

Nothing is known of any ancient Orphic writings except a reference in the ''Alcestis

Alcestis (; Ancient Greek: Ἄλκηστις, ') or Alceste, was a princess in Greek mythology, known for her love of her husband. Her life story was told by pseudo-Apollodorus in his '' Bibliotheca'', and a version of her death and return from ...

'' of Euripides to certain Thracian tablets which "the voice of Orpheus had inscribed" with pharmaceutical lore. The Scholiast, commenting on the passage, says that there exist on Mt. Haemus certain writings of Orpheus on tablets. There is also a reference, not mentioning Orpheus by name, in the pseudo

The prefix pseudo- (from Greek ψευδής, ''pseudes'', "false") is used to mark something that superficially appears to be (or behaves like) one thing, but is something else. Subject to context, ''pseudo'' may connote coincidence, imitation, ...

-Platonic ''Axiochus'', where it is said that the fate of the soul in Hades is described on certain bronze tablets which two seers had brought to Delos

The island of Delos (; el, Δήλος ; Attic: , Doric: ), near Mykonos, near the centre of the Cyclades archipelago, is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. The excavations in the island are ...

from the land of the Hyperborea

In Greek mythology, the Hyperboreans ( grc, Ὑπερβόρε(ι)οι, ; la, Hyperborei) were a mythical people who lived in the far northern part of the known world. Their name appears to derive from the Greek , "beyond Boreas" (the God of ...

ns. This is the only evidence for any ancient Orphic writings. Aelian Aelian or Aelianus may refer to:

* Aelianus Tacticus, Greek military writer of the 2nd century, who lived in Rome

* Casperius Aelianus, Praetorian Prefect, executed by Trajan

* Claudius Aelianus, Roman writer, teacher and historian of the 3rd centu ...

(second century AD) gave the chief reason against believing in them: at the time when Orpheus is said to have lived, the Thracians

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European languages, Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. ...

knew nothing about writing.

It came therefore to be believed that Orpheus taught, but left no writings, and that the epic poetry attributed to him was written in the sixth century BC by Onomacritus. Onomacritus was banished from Athens by Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equi ...

for inserting something of his own into an oracle of Musaeus when entrusted with the editing of his poems. It may have been Aristotle who first suggested, in the lost ''De Philosophia'', that Onomacritus also wrote the so-called Orphic epic poems. By the time when the Orphic writings began to be freely quoted by Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

and Neo-Platonist

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some id ...

writers, the theory of the authorship of Onomacritus was accepted by many.

It is believed, however, that the Orphic literature current in the time of the Neo-Platonists (third century AD), and quoted by them as the authority for Orphic doctrines, was a collection of writings of different periods and varying outlook, something like that of the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

. The earliest of these were composed in the sixth century by Onomacritus from genuine Orphic tradition; the latest which have survived, namely the ''Voyage of the Argonauts'', and the Hymns to various deities, cannot have been put together in their present form until the beginning of the Christian era, and are probably to be dated some time between the second and fourth centuries AD.

The Neo-Platonists quote the Orphic poems in their defence against Christianity, because Plato used poems which he believed to be Orphic. It is believed that in the collection of writings which they used there were several versions, each of which gave a slightly different account of the origin of the universe, of gods and men, and perhaps of the correct way of life, with the rewards and punishments attached thereto. Three principal versions are recognized by modern scholars; all three are mentioned by the Neo-Platonist Damascius

Damascius (; grc-gre, Δαμάσκιος, 458 – after 538), known as "the last of the Athenian Neoplatonists," was the last scholarch of the neoplatonic Athenian school. He was one of the neoplatonic philosophers who left Athens after laws ...

(fifth to sixth centuries AD).

These are:

# ''Rhapsodiae'', epic lays, said by Damascius

Damascius (; grc-gre, Δαμάσκιος, 458 – after 538), known as "the last of the Athenian Neoplatonists," was the last scholarch of the neoplatonic Athenian school. He was one of the neoplatonic philosophers who left Athens after laws ...

to give the usual Orphic theology. These are mentioned also in Suidas

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; grc-x-medieval, Σοῦδα, Soûda; la, Suidae Lexicon) is a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas (Σούδας) or Souidas ...

's list, as "sacred discourses in twenty-four lays", though he attributes this work to Theognetus the Thessalian (unknown) or Cercops

Cercops ( grc, Κέρκωψ) was one of the oldest Orphic poets. He was called a Pythagorean by Clement of Alexandria, which might have meant a Neopythagorean.Clement of Alexandria, '' Stromata'', i. Cicero, was said by Epigenes of Alexandria to h ...

the Pythagorean. This is now referred to as the Rhapsodic Theogony. It is the version usually quoted by ancient authorities, but was not the one used by Plato, and is therefore some-times thought to have been composed after he wrote; this question cannot at present be decided.

# An Orphic Theogony given by Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

's pupil Eudemus.

# An Orphic Theogony "according to Hieronymus

Hieronymus, in English pronounced or , is the Latin form of the Ancient Greek name (Hierṓnymos), meaning "with a sacred name". It corresponds to the English given name Jerome.

Variants

* Albanian: Jeronimi

* Arabic: جيروم (Jerome)

* Basqu ...

and Hellanicus". Other versions were: a Theogony put into the mouth of Orpheus by Apollonius Rhodius

Apollonius of Rhodes ( grc, Ἀπολλώνιος Ῥόδιος ''Apollṓnios Rhódios''; la, Apollonius Rhodius; fl. first half of 3rd century BC) was an ancient Greek author, best known for the ''Argonautica'', an epic poem about Jason and t ...

in his ''Argonautica

The ''Argonautica'' ( el, Ἀργοναυτικά , translit=Argonautika) is a Greek epic poem written by Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. The only surviving Hellenistic epic, the ''Argonautica'' tells the myth of the voyage of Jason a ...

'' an Orphic Theogony quoted by Alexander of Aphrodisias

Alexander of Aphrodisias ( grc-gre, Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Ἀφροδισιεύς, translit=Alexandros ho Aphrodisieus; AD) was a Peripatetic school, Peripatetic philosopher and the most celebrated of the Ancient Greek Commentaries on Aristo ...

; and a Theogony in Clement of Rome

Pope Clement I ( la, Clemens Romanus; Greek: grc, Κλήμης Ῥώμης, Klēmēs Rōmēs) ( – 99 AD) was bishop of Rome in the late first century AD. He is listed by Irenaeus and Tertullian as the bishop of Rome, holding office from 88 AD t ...

, not specified as Orphic, but belonging to the same school of thought.

A long list of Orphic works is given in Suidas

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; grc-x-medieval, Σοῦδα, Soûda; la, Suidae Lexicon) is a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas (Σούδας) or Souidas ...

(tenth century AD); but most of these are there attributed to other authors.

They are:

# ''Triagmoi'', attributed to the tragic poet Ion, in which there was said to be a chapter called ''Sacred Vestments'', or ''Cosmic Invocations''. The title ''Triagmoi'' apparently referred to "the Orphic tripod of three elements, earth, water, fire", referred to by Ausonius

Decimius Magnus Ausonius (; – c. 395) was a Roman poet and teacher of rhetoric from Burdigala in Aquitaine, modern Bordeaux, France. For a time he was tutor to the future emperor Gratian, who afterwards bestowed the consulship on him. H ...

and Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one of ...

; the latter said that this doctrine was given by Onomacritus

Onomacritus ( grc-gre, Ὀνομάκριτος; c. 530 – c. 480 BCE), also known as Onomacritos or Onomakritos, was a Greek chresmologue, or compiler of oracles, who lived at the court of the tyrant Pisistratus in Athens. He is said to have pre ...

in his Orphic poems.

# The ''Sacred Discourses'', already discussed, usually identified with the ''Rhapsodiae''.

# ''Oracles and Rites'', attributed to Onomacritus

Onomacritus ( grc-gre, Ὀνομάκριτος; c. 530 – c. 480 BCE), also known as Onomacritos or Onomakritos, was a Greek chresmologue, or compiler of oracles, who lived at the court of the tyrant Pisistratus in Athens. He is said to have pre ...

.

# ''Aids to Salvation'', ascribed to Timocles

Timocles (Ancient Greek: Τιμοκλῆς, ) was one of the last Athenian comic poets of the Middle Comedy, although Pollux listed him among the writers of New Comedy. He is known to have won first prize at the Lenaea once, between 330 and 320 B ...

of Syracuse or Persinus of Miletus; both the work and these writers are otherwise unknown.

# ''Mixing-bowls'', ascribed to Zopyrus of Heracleia; and ''The Robe'' and ''The Net'', also ascribed to Zopyrus, or to Brontinus Brontinus of Metapontum ( el, Βροντῖνος, also Brotinus, ; fl. 6th century BCE) was a Pythagorean philosopher and a friend and disciple of Pythagoras. Alcmaeon dedicated his works to Brontinus as well as to Leon and Bathyllus. Accounts v ...

the Pythagorean. The Net referred to is the net of the body, so called in Orphic literature. To Brontinus was also ascribed a ''Physica'', otherwise unknown.

# ''Enthronement of the Mother'', and ''Bacchic Rites'', ascribed to Nicias of Elea, of whom nothing else is known. "Enthronement" was part of the rite of initiation practised by the Corybantes

According to Greek mythology, the Korybantes or Corybantes (also Corybants) (; grc-gre, Κορύβαντες) were the armed and crested dancers who worshipped the Phrygian goddess Cybele with drumming and dancing. They are also called the ''Ku ...

, the worshippers of Rhea or Cybele

Cybele ( ; Phrygian: ''Matar Kubileya/Kubeleya'' "Kubileya/Kubeleya Mother", perhaps "Mountain Mother"; Lydian ''Kuvava''; el, Κυβέλη ''Kybele'', ''Kybebe'', ''Kybelis'') is an Anatolian mother goddess; she may have a possible forer ...

; the person to be initiated was seated on a high chair, and the celebrants danced round him in a ring. The title therefore apparently means "the enthronement-ceremonies as practised by the worshippers of the Great Mother". Connected, perhaps identical with, this was a treatise on Corybantic Rites, quoted by the late Orphic poem ''Argonautica''.

# ''A Descent into Hades'', ascribed to Herodicus of Perinthus

Herodicus ( el, Ἡρóδιĸος) was a 5th century BC Greeks, Greek physician, dietician, became nurse, sophist, and gymnastic-master (παιδοτρίβης). He was born in the city of Selymbria, a colony of the city-state Megara, and practice ...

, or to Cercops

Cercops ( grc, Κέρκωψ) was one of the oldest Orphic poets. He was called a Pythagorean by Clement of Alexandria, which might have meant a Neopythagorean.Clement of Alexandria, '' Stromata'', i. Cicero, was said by Epigenes of Alexandria to h ...

the Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

, or to the unknown Prodicus of Samos

Prodicus of Ceos (; grc-gre, Πρόδικος ὁ Κεῖος, ''Pródikos ho Keios''; c. 465 BC – c. 395 BC) was a Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher, and part of the first generation of Sophists. He came to Athens as ambassador from Ceos, a ...

.

# Other treatises were: an ''Astronomy'' or ''Astrology'', otherwise unknown; ''Sacrificial Rites'', doubtless giving rules for bloodless sacrifices; ''Divination by means of sand'', ''Divination by means of eggs''; on ''Temple-building'' (otherwise unknown); ''On the girding on of Sacred Robes''; and ''On Stones'', said to contain a chapter on the carving of precious stones entitled ''The Eighty Stones''; a version of this work, of late date, survives. It treats of the properties of stones, precious and ordinary, and their uses in divination. The Orphic Hymn

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracians, Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned Ancient Greek poetry, poet and, according to ...

s are also mentioned in Suidas

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; grc-x-medieval, Σοῦδα, Soûda; la, Suidae Lexicon) is a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas (Σούδας) or Souidas ...

's list, and a Theogony in 1200 verses, perhaps one of those versions which differed from the ''Rhapsodiae''. There was also an Orphic Word-book, doubtless a glossary of the special terms used in the cult, some of which were strange because of their allegorical usage, others because of their antiquity; this also was said to have been in verse.

Such was the list of works finally classed as Orphic writings, though it was known in early times that many of them were the works of Pythagoreans and other writers. Herodotus said of the so-called "Orphic and Bacchic rites" that they were actually "Egyptian and Pythagorean"; and Ion of Chios

Ion of Chios (; grc-gre, Ἴων ὁ Χῖος; c. 490/480 – c. 420 BC) was a Greek writer, dramatist, lyric poet and philosopher. He was a contemporary of Aeschylus, Euripides and Sophocles. Of his many plays and poems only a few titles and fr ...

said that Pythagoras himself attributed some of his writings to Orpheus. Others, as has been said, regarded the earliest epics as the work of Onomacritus

Onomacritus ( grc-gre, Ὀνομάκριτος; c. 530 – c. 480 BCE), also known as Onomacritos or Onomakritos, was a Greek chresmologue, or compiler of oracles, who lived at the court of the tyrant Pisistratus in Athens. He is said to have pre ...

. The original Hymns were thought to have been composed by Orpheus, and written down, with emendations, by Musaeus. There were also other writers named Orpheus: to one, of Croton, said to be a contemporary and associate of Peisistratus

Pisistratus or Peisistratus ( grc-gre, Πεισίστρατος ; 600 – 527 BC) was a politician in ancient Athens, ruling as tyrant in the late 560s, the early 550s and from 546 BC until his death. His unification of Attica, the triangular ...

, were attributed two epic poems: an ''Argonautica'', and ''The Twelve-year Cycle'' (probably astrological); to another, Orpheus of Camarina

Kamarina ( grc, Καμάρινα, Latin, Italian, & scn, Camarina) was an ancient city on the southern coast of Sicily in southern Italy. The ruins of the site and an archaeological museum are located south of the modern town of Scoglitti, a ...

, an epic ''Descent into Hades''. These namesakes are probably inventions."

Mythology

Early life

Apollodorus

Apollodorus (Ancient Greek, Greek: Ἀπολλόδωρος ''Apollodoros'') was a popular name in ancient Greece. It is the masculine gender of a noun compounded from Apollo, the deity, and doron, "gift"; that is, "Gift of Apollo." It may refer to: ...

and a fragment of Pindar, Orpheus's father was Oeagrus In Greek mythology, Oeagrus ( grc-gre, Οἴαγρος, Oíagros, of the wild sorb-apple) was a king of Thrace.

Biography

Kingdom

There are various versions as to where Oeagrus' domain was actually situated. In one version, he ruled over the E ...

, a Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied t ...

king, or, according to another version of the story, the god Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

. His mother was (1) the muse

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, the Muses ( grc, Μοῦσαι, Moûsai, el, Μούσες, Múses) are the inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. They were considered the source of the knowledge embodied in the ...

Calliope

In Greek mythology, Calliope ( ; grc, Καλλιόπη, Kalliópē, beautiful-voiced) is the Muse who presides over eloquence and epic poetry; so called from the ecstatic harmony of her voice. Hesiod and Ovid called her the "Chief of all Muses" ...

, (2) her sister Polymnia, (3) a daughter of Pierus

Pierus (; grc, Πίερος), in Greek mythology, is a name attributed to two individuals:

* Pierus, the eponym of Pieria, son of Makednos and father of the Pierides.Antoninus Liberalis, 9

* Pierus, son of Thessalian Magnes and father of Hyac ...

, son of Makednos

In Greek mythology, Makedon, also Macedon ( grc, Μακεδών) or Makednos (), was the eponymous ancestor of the ancient Macedonians according to various ancient Greek fragmentary narratives. In most versions, he appears as a native or immigra ...

or (4) lastly of Menippe, daughter of Thamyris

In Greek mythology, Thamyris (Ancient Greek: Θάμυρις, ''Thámuris'') was a Thracian singer. He is notable in Greek mythology for reportedly being a lover of Hyacinth and thus to have been the first male to have loved another male, but when ...

. According to Tzetzes

John Tzetzes ( grc-gre, Ἰωάννης Τζέτζης, Iōánnēs Tzétzēs; c. 1110, Constantinople – 1180, Constantinople) was a Byzantine poet and grammarian who is known to have lived at Constantinople in the 12th century.

He was able to p ...

, he was from Bisaltia

Bisaltia ( el, Βισαλτία) or Bisaltica was an ancient country which was bordered by Sintice on the north, Crestonia on the west, Mygdonia on the south and was separated by Odomantis on the north-east and Edonis on the south-east by river ...

. His birthplace and place of residence was Pimpleia

Pimpleia (Ancient Greek: Πίμπλεια) was a city in Pieria in Ancient Greece, located near Dion and ancient Leivithra at Mount Olympus. Pimpleia is described as a "κώμη" ("quarter, suburb") of Dion by Strabo. The location of Pimpleia is ...

Jane Ellen Harrison, ''Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion (Mythos Books)'', 1991, , p. 469: " ��near the city of Dium is a village called Pimpleia where Orpheus lived." close to the Olympus

Olympus or Olympos ( grc, Ὄλυμπος, link=no) may refer to:

Mountains

In antiquity

Greece

* Mount Olympus in Thessaly, northern Greece, the home of the twelve gods of Olympus in Greek mythology

* Mount Olympus (Lesvos), located in Les ...

. Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

mentions that he lived in Pimpleia. According to the epic poem ''Argonautica

The ''Argonautica'' ( el, Ἀργοναυτικά , translit=Argonautika) is a Greek epic poem written by Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. The only surviving Hellenistic epic, the ''Argonautica'' tells the myth of the voyage of Jason a ...

'', Pimpleia was the location of Oeagrus's and Calliope's wedding. While living with his mother and her eight beautiful sisters in Parnassus

Mount Parnassus (; el, Παρνασσός, ''Parnassós'') is a mountain range of central Greece that is and historically has been especially valuable to the Greek nation and the earlier Greek city-states for many reasons. In peace, it offers ...

, he met Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

, who was courting the laughing muse Thalia

Thalia, Thalía, Thaleia or Thalian may refer to:

People

* Thalia (given name), including a list of people with the name

* Thalía (born 1971), Mexican singer and actress

Mythological and fictional characters

* Thalia (Grace), one of the three ...

. Apollo, as the god of music, gave Orpheus a golden lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

and taught him to play it. Orpheus's mother taught him to make verses for singing. He is also said to have studied in Egypt.

Orpheus is said to have established the worship of Hecate

Hecate or Hekate, , ; grc-dor, Ἑκάτᾱ, Hekátā, ; la, Hecatē or . is a goddess in ancient Greek religion and mythology, most often shown holding a pair of torches, a key, snakes, or accompanied by dogs, and in later periods depicte ...

in Aegina

Aegina (; el, Αίγινα, ''Aígina'' ; grc, Αἴγῑνα) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina (mythology), Aegina, the mother of the hero Aeacus, who was born ...

. In Laconia

Laconia or Lakonia ( el, Λακωνία, , ) is a historical and administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparta. The word ''laconic''—to speak in a blunt, c ...

Orpheus is said to have brought the worship of Demeter Chthonia and that of the (; 'Saviour Maidens'). Also in Taygetos

The Taygetus, Taugetus, Taygetos or Taÿgetus ( el, Ταΰγετος, Taygetos) is a mountain range on the Peloponnese peninsula in Southern Greece. The highest mountain of the range is Mount Taygetus, also known as "Profitis Ilias", or "Prophet ...

a wooden image of Orpheus was said to have been kept by Pelasgians

The name Pelasgians ( grc, Πελασγοί, ''Pelasgoí'', singular: Πελασγός, ''Pelasgós'') was used by classical Greek writers to refer either to the predecessors of the Greeks, or to all the inhabitants of Greece before the emergenc ...

in the sanctuary of the Eleusinian Demeter.

According to Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

, Musaeus of Athens

Musaeus of Athens ( el, Μουσαῖος, ''Mousaios'') was a legendary polymath, philosopher, historian, prophet, seer, priest, poet, and musician, said to have been the founder of priestly poetry in Attica. He composed dedicatory and purificato ...

was the son of Orpheus.

Adventure as an Argonaut

The ''Argonautica

The ''Argonautica'' ( el, Ἀργοναυτικά , translit=Argonautika) is a Greek epic poem written by Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. The only surviving Hellenistic epic, the ''Argonautica'' tells the myth of the voyage of Jason a ...

'' () is a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

epic poem

An epic poem, or simply an epic, is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants.

...

written by Apollonius Rhodius

Apollonius of Rhodes ( grc, Ἀπολλώνιος Ῥόδιος ''Apollṓnios Rhódios''; la, Apollonius Rhodius; fl. first half of 3rd century BC) was an ancient Greek author, best known for the ''Argonautica'', an epic poem about Jason and t ...

in the 3rd century BC. Orpheus took part in this adventure and used his skills to aid his companions. Chiron told Jason that without the aid of Orpheus, the Argonauts

The Argonauts (; Ancient Greek: ) were a band of heroes in Greek mythology, who in the years before the Trojan War (around 1300 BC) accompanied Jason to Colchis in his quest to find the Golden Fleece. Their name comes from their ship, '' Argo'', ...

would never be able to pass the Siren

Siren or sirens may refer to:

Common meanings

* Siren (alarm), a loud acoustic alarm used to alert people to emergencies

* Siren (mythology), an enchanting but dangerous monster in Greek mythology

Places

* Siren (town), Wisconsin

* Siren, Wisc ...

s—the same Sirens encountered by Odysseus

Odysseus ( ; grc-gre, Ὀδυσσεύς, Ὀδυσεύς, OdysseúsOdyseús, ), also known by the Latin variant Ulysses ( , ; lat, UlyssesUlixes), is a legendary Greek king of Ithaca and the hero of Homer's epic poem the ''Odyssey''. Odysse ...

in Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

's epic poem the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek Epic poetry, epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by moder ...

''. The Sirens lived on three small, rocky islands called Sirenum scopuli

According to the Roman poets Virgil (''Aeneid'', 5.864) and Ovid, the Sirenum Scopuli were three small rocky islands where the sirens of Greek mythology lived and lured sailors to their deaths. "The Sirenum Scopuli are sharp rocks that stand about ...

and sang beautiful songs that enticed sailors to come to them, which resulted in the crashing of their ships into the islands. When Orpheus heard their voices, he drew his lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

and played music that was louder and more beautiful, drowning out the Sirens' bewitching songs. According to 3rd century BC Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

elegiac The adjective ''elegiac'' has two possible meanings. First, it can refer to something of, relating to, or involving, an elegy or something that expresses similar mournfulness or sorrow. Second, it can refer more specifically to poetry composed in ...

poet Phanocles

Phanocles ( grc, Φανοκλῆς) was a Greek elegiac poet who probably flourished about the time of Alexander the Great.

His extant fragments show resemblances in style and language to Philitas of Cos, Callimachus and Hermesianax. He was the a ...

, Orpheus loved the young Argonaut Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

, "the son of Boreas, with all his heart, and went often in shaded groves still singing of his desire, nor was his heart at rest. But always, sleepless cares wasted his spirits as he looked at fresh Calais."

Death of Eurydice

The most famous story in which Orpheus figures is that of his wife

The most famous story in which Orpheus figures is that of his wife Eurydice

Eurydice (; Ancient Greek: Εὐρυδίκη 'wide justice') was a character in Greek mythology and the Auloniad wife of Orpheus, who tried to bring her back from the dead with his enchanting music.

Etymology

Several meanings for the name ...

(sometimes referred to as Euridice and also known as Argiope). While walking among her people, the Cicones, in tall grass at her wedding, Eurydice was set upon by a satyr

In Greek mythology, a satyr ( grc-gre, :wikt:σάτυρος, σάτυρος, sátyros, ), also known as a silenus or ''silenos'' ( grc-gre, :wikt:Σειληνός, σειληνός ), is a male List of nature deities, nature spirit with ears ...

. In her efforts to escape the satyr, Eurydice fell into a nest of vipers and suffered a fatal bite on her heel. Her body was discovered by Orpheus who, overcome with grief, played such sad and mournful songs that all the nymph

A nymph ( grc, νύμφη, nýmphē, el, script=Latn, nímfi, label=Modern Greek; , ) in ancient Greek folklore is a minor female nature deity. Different from Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as personifications of nature, are ty ...

s and gods wept. On their advice, Orpheus traveled to the underworld

The underworld, also known as the netherworld or hell, is the supernatural world of the dead in various religious traditions and myths, located below the world of the living. Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underworld.

...

. His music softened the hearts of Hades

Hades (; grc-gre, ᾍδης, Háidēs; ), in the ancient Greek religion and myth, is the god of the dead and the king of the underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea, although this also ...

and Persephone

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Persephone ( ; gr, Περσεφόνη, Persephónē), also called Kore or Cora ( ; gr, Κόρη, Kórē, the maiden), is the daughter of Zeus and Demeter. She became the queen of the underworld after ...

, who agreed to allow Eurydice to return with him to earth on one condition: he should walk in front of her and not look back until they both had reached the upper world. Orpheus set off with Eurydice following; however, as soon as he had reached the upper world, he immediately turned to look at her, forgetting in his eagerness that both of them needed to be in the upper world for the condition to be met. As Eurydice had not yet crossed into the upper world, she vanished for the second time, this time forever.

The story in this form belongs to the time of Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

, who first introduces the name of Aristaeus

A minor god in Greek mythology, attested mainly by Athenian writers, Aristaeus (; ''Aristaios'' (Aristaîos); lit. “Most Excellent, Most Useful”), was the culture hero credited with the discovery of many useful arts, including bee-keeping; ...

(by the time of Virgil's ''Georgics

The ''Georgics'' ( ; ) is a poem by Latin poet Virgil, likely published in 29 BCE. As the name suggests (from the Greek word , ''geōrgika'', i.e. "agricultural (things)") the subject of the poem is agriculture; but far from being an example ...

'', the myth has Aristaeus chasing Eurydice when she was bitten by a serpent) and the tragic outcome. Other ancient writers, however, speak of Orpheus's visit to the underworld in a more negative light; according to Phaedrus in Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

's ''Symposium

In ancient Greece, the symposium ( grc-gre, συμπόσιον ''symposion'' or ''symposio'', from συμπίνειν ''sympinein'', "to drink together") was a part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was acc ...

'', the infernal gods only "presented an apparition" of Eurydice to him. In fact, Plato's representation of Orpheus is that of a coward, as instead of choosing to die in order to be with the one he loved, he instead mocked the gods by trying to go to Hades to bring her back alive. Since his love was not "true"—he did not want to die for love—he was actually punished by the gods, first by giving him only the apparition of his former wife in the underworld, and then by being killed by women. In Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

's account, however, Eurydice's death by a snake bite is incurred while she was dancing with naiad

In Greek mythology, the naiads (; grc-gre, ναϊάδες, naïádes) are a type of female spirit, or nymph, presiding over fountains, wells, springs, streams, brooks and other bodies of fresh water.

They are distinct from river gods, who ...

s on her wedding day.

Virgil wrote in his poem that Dryads

A dryad (; el, Δρυάδες, ''sing''.: ) is a tree nymph or tree spirit in Greek mythology. ''Drys'' (δρῦς) signifies "oak" in Greek, and dryads were originally considered the nymphs of oak trees specifically, but the term has evolved to ...

wept from Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =