Ornithopters on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An ornithopter (from

An ornithopter (from

In 1841, an ironsmith ''

In 1841, an ironsmith '' E. P. Frost made ornithopters starting in the 1870s; first models were powered by steam engines, then in the 1900s, an internal-combustion craft large enough for a person was built, though it did not fly.Kelly, Maurice. 2006. ''Steam in the Air''. Ben & Sword Books. Pages 49–55 are about Frost.

In the 1930s,

E. P. Frost made ornithopters starting in the 1870s; first models were powered by steam engines, then in the 1900s, an internal-combustion craft large enough for a person was built, though it did not fly.Kelly, Maurice. 2006. ''Steam in the Air''. Ben & Sword Books. Pages 49–55 are about Frost.

In the 1930s,

Crewed ornithopters fall into two general categories: Those powered by the muscular effort of the pilot (human-powered ornithopters), and those powered by an engine.

Around 1894,

Crewed ornithopters fall into two general categories: Those powered by the muscular effort of the pilot (human-powered ornithopters), and those powered by an engine.

Around 1894,  In 2005,

In 2005,

" Benedict, Moble. 3–4. The 1960s saw powered uncrewed ornithopters of various sizes capable of achieving and sustaining flight, providing valuable real-world examples of mechanical winged flight. In 1991, Harris and DeLaurier flew the first successful engine-powered remotely piloted ornithopter in Toronto, Canada. In 1999, a piloted ornithopter based on this design flew, capable of taking off from level pavement and executing sustained flight. An ornithopter's flapping wings and their motion through the air are designed to maximize the amount of lift generated within limits of weight, material strength and mechanical complexity. A flexible wing material can increase efficiency while keeping the driving mechanism simple. In wing designs with the spar sufficiently forward of the airfoil that the aerodynamic center is aft of the elastic axis of the wing, aeroelastic deformation causes the wing to move in a manner close to its ideal efficiency (in which pitching angles lag plunging displacements by approximately 90 degrees.) Flapping wings increase drag and are not as efficient as propeller-powered aircraft. Some designs achieve increased efficiency by applying more power on the down stroke than on the upstroke, as do most birds.An Ornithopter Wing Design

DeLaurier, James D. (1994), 10–18 (accessed November 30, 2010) In order to achieve the desired flexibility and minimum weight, engineers and researchers have experimented with wings that require carbon fiber, plywood, fabric, and ribs, with a stiff, strong trailing edge. Any mass located aft of the empennage reduces the wing's performance, so lightweight materials and empty space are used where possible. To minimize drag and maintain the desired shape, choice of a material for the wing surface is also important. In DeLaurier's experiments, a smooth aerodynamic surface with a double-surface airfoil is more efficient at producing lift than a single-surface airfoil. Other ornithopters do not necessarily act like birds or bats in flight. Typically birds and bats have thin and cambered wings to produce lift and thrust. Ornithopters with thinner wings have a limited angle of attack but provide optimum minimum-drag performance for a single lift coefficient. Although

The Ornithopter Zone

* Mueller, Thomas J. (2001). "Fixed and flapping wing aerodynamics for micro air vehicle applications". Virginia: American Inst. of Aeronautics and Astronautics. * Azuma, Akira (2006). "The Biokinetics of Flying and Swimming". Virginia: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 2nd Edition. . * DeLaurier, James D.

The Development and Testing of a Full-Scale Piloted Ornithopter.

The Aerodynamics of Hummingbird Flight.

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 1–5. Web. 30 Nov 2010. * Crouch, Tom D. Aircraft of the National Air and Space Museum. Fourth ed. Lilienthal Standard Glider. Smithsonian Institution, 1991. * Bilstein, Roger E. Flight in America 1900–1983. First ed. Gliders and Airplanes. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984. (pages 8–9) * Crouch, Tom D. ''Wings. A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age.'' First ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2003. (pages 44–53) * Anderson, John D. ''A history of aerodynamics and its impact on flying machines.'' Cambridge: United Kingdom, 1997.

An ornithopter (from

An ornithopter (from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''ornis, ornith-'' "bird" and ''pteron'' "wing") is an aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines ...

that flies

Flies are insects of the order Diptera, the name being derived from the Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwings having evolved into advanced ...

by flapping its wing

A wing is a type of fin that produces lift while moving through air or some other fluid. Accordingly, wings have streamlined cross-sections that are subject to aerodynamic forces and act as airfoils. A wing's aerodynamic efficiency is expres ...

s. Designers sought to imitate the flapping-wing flight of birds, bat

Bats are mammals of the order Chiroptera.''cheir'', "hand" and πτερόν''pteron'', "wing". With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most bi ...

s, and insects

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs of j ...

. Though machines may differ in form, they are usually built on the same scale as flying animals. Larger, crewed ornithopters have also been built and some have been successful. Crewed ornithopters are generally either powered by engines or by the pilot

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its directional flight controls. Some other aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are also considered aviators, because they a ...

.

Early history

Some early crewed flight attempts may have been intended to achieve flapping-wing flight, but probably only a glide was actually achieved. They include the purported flights of the 11th-centuryCatholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

monk Eilmer of Malmesbury

Eilmer of Malmesbury (also known as Oliver due to a scribe's miscopying, or Elmer, or Æthelmær) was an 11th-century English Benedictine monk best known for his early attempt at a gliding flight using wings.

Life

Eilmer was a monk of Malmesb ...

(recorded in the 12th century) and the 9th-century poet Abbas Ibn Firnas

Abu al-Qasim Abbas ibn Firnas ibn Wirdas al-Takurini ( ar, أبو القاسم عباس بن فرناس بن ورداس التاكرني; c. 809/810 – 887 A.D.), also known as Abbas ibn Firnas ( ar, عباس ابن فرناس), Latinized Armen ...

(recorded in the 17th century). Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; la, Rogerus or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through empiri ...

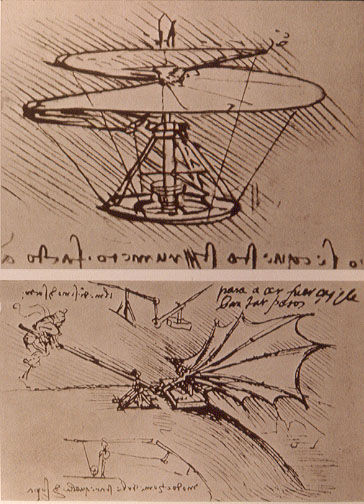

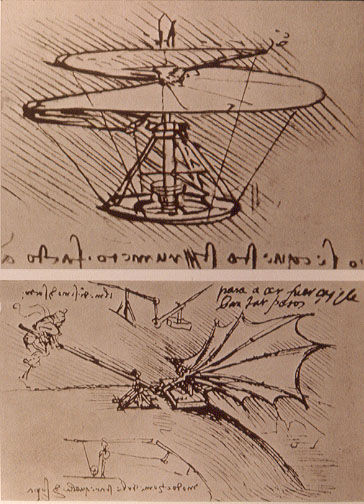

, writing in 1260, was also among the first to consider a technological means of flight. In 1485, Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

began to study the flight of birds. He grasped that humans are too heavy, and not strong enough, to fly using wings simply attached to the arms. He, therefore, sketched a device in which the aviator lies down on a plank and works two large, membranous wings using hand levers, foot pedals, and a system of pulleys.

In 1841, an ironsmith ''

In 1841, an ironsmith ''kalfa

Kalfa ( Turkish for 'apprentice, assistant master') was a general term in the Ottoman Empire for the women attendants and supervisors in service in the imperial palace.

Novice girls had to await promotion to the rank of . It was a rank below th ...

'' (journeyman), Manojlo, who "came to Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

from Vojvodina

Vojvodina ( sr-Cyrl, Војводина}), officially the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, is an autonomous province that occupies the northernmost part of Serbia. It lies within the Pannonian Basin, bordered to the south by the national capital ...

", attempted flying with a device described as an ornithopter ("flapping wings like those of a bird"). Refused by the authorities a permit to take off from the belfry of Saint Michael's Cathedral, he clandestinely climbed to the rooftop of the Dumrukhana (import tax head office) and took off, landing in a heap of snow, and surviving.

The first ornithopters capable of flight were constructed in France. Jobert in 1871 used a rubber band

A rubber band (also known as an elastic band, gum band or lacky band) is a loop of rubber, usually ring or oval shaped, and commonly used to hold multiple objects together. The rubber band was patented in England on March 17, 1845 by Stephen P ...

to power a small model bird. Alphonse Pénaud

Alphonse Pénaud (31 May 1850 – 22 October 1880), was a 19th-century French pioneer of aviation design and engineering. He was the originator of the use of twisted rubber to power model aircraft, and his 1871 model airplane, which he called ...

, Abel Hureau de Villeneuve

Abel Hureau de Villeneuve (1833 – 2 June 1898) was an aeronautical experimenter, and ran a major French aeronautical society and journal in the late nineteenth century. He was also a vegetarianism activist.

Aviation research

In the 1870s, Dr. ...

, and Victor Tatin

Victor Tatin (1843–1913) was a French engineer who created an early airplane, the ''Aéroplane'', in 1879. The craft was the first model airplane to take off using its own power after a run on the ground.

The model had a span of and weighed . ...

, also made rubber-powered ornithopters during the 1870s. Tatin's ornithopter was perhaps the first to use active torsion of the wings, and apparently it served as the basis for a commercial toy offered by Pichancourt

In 1889; Pichancourt (first name is not known) developed the L'Oiseau Mechanique ( Mechanical Bird) which aimed to imitate the motion of a bird's wings in flight.

Image:pichancourt-flyingbird.jpg, Mechanical Bird 1889

References

* Chanute, Oct ...

1889. Gustave Trouvé

Gustave Pierre Trouvé (2 January 1839 – 27 July 1902) was a French electrical engineer and inventor in the 19th century.

Trouvé was born on 2 January 1839 in La Haye-Descartes (Indre-et-Loire, France) and died on 27 July 1902 in Paris. A pol ...

was the first to use internal combustion, and his 1890 model flew a distance of 80 meters in a demonstration for the French Academy of Sciences. The wings were flapped by gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). ...

charges activating a Bourdon tube

Pressure measurement is the measurement of an applied force by a fluid (liquid or gas) on a surface. Pressure is typically measured in unit of measurement, units of force per unit of surface area. Many techniques have been developed for the me ...

.

From 1884 on, Lawrence Hargrave

Lawrence Hargrave, MRAeS, (29 January 18506 July 1915) was a British-born Australian engineer, explorer, astronomer, inventor and aeronautical pioneer.

Biography

Lawrence Hargrave was born in Greenwich, England, the second son of John Fletch ...

built scores of ornithopters powered by rubber bands, springs, steam

Steam is a substance containing water in the gas phase, and sometimes also an aerosol of liquid water droplets, or air. This may occur due to evaporation or due to boiling, where heat is applied until water reaches the enthalpy of vaporization ...

, or compressed air

Compressed air is air kept under a pressure that is greater than atmospheric pressure. Compressed air is an important medium for transfer of energy in industrial processes, and is used for power tools such as air hammers, drills, wrenches, and o ...

. He introduced the use of small flapping wings providing the thrust for a larger fixed wing; this innovation eliminated the need for gear reduction, thereby simplifying the construction.

Alexander Lippisch

Alexander Martin Lippisch (November 2, 1894 – February 11, 1976) was a German aeronautical engineer, a pioneer of aerodynamics who made important contributions to the understanding of tailless aircraft, delta wings and the ground effect, and a ...

and the National Socialist Flyers Corps

The National Socialist Flyers Corps (german: Nationalsozialistisches Fliegerkorps; NSFK) was a paramilitary aviation organization of the Nazi Party.

History

NSFK was founded 15 April 1937 as a successor to the German Air Sports Association; the ...

of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

constructed and successfully flew a series of internal combustion-powered ornithopters, using Hargrave's concept of small flapping wings, but with aerodynamic improvements resulting from the methodical study.

Erich von Holst

Erich Walther von Holst (28 November 1908 – 26 May 1962) was a German behavioral physiologist who was a Baltic German native of Riga, Livonia and was related to historian Hermann Eduard von Holst (1841–1904). In the 1950s he founded th ...

, also working in the 1930s, achieved great efficiency and realism in his work with ornithopters powered by rubber bands. He achieved perhaps the first success of an ornithopter with a bending wing, intended to imitate more closely the folding wing action of birds, although it was not a true variable-span wing-like those of birds.

Around 1960, Percival Spencer successfully flew a series of uncrewed ornithopters using internal combustion engines ranging from displacement, and having wingspans up to . In 1961, Percival Spencer and Jack Stephenson flew the first successful engine-powered, remotely piloted ornithopter, known as the Spencer Orniplane. The Orniplane had a wingspan, weighed , and was powered by a -displacement two-stroke engine

A two-stroke (or two-stroke cycle) engine is a type of internal combustion engine that completes a power cycle with two strokes (up and down movements) of the piston during one power cycle, this power cycle being completed in one revolution of t ...

. It had a biplane configuration, to reduce oscillation of the fuselage.

Crewed flight

Crewed ornithopters fall into two general categories: Those powered by the muscular effort of the pilot (human-powered ornithopters), and those powered by an engine.

Around 1894,

Crewed ornithopters fall into two general categories: Those powered by the muscular effort of the pilot (human-powered ornithopters), and those powered by an engine.

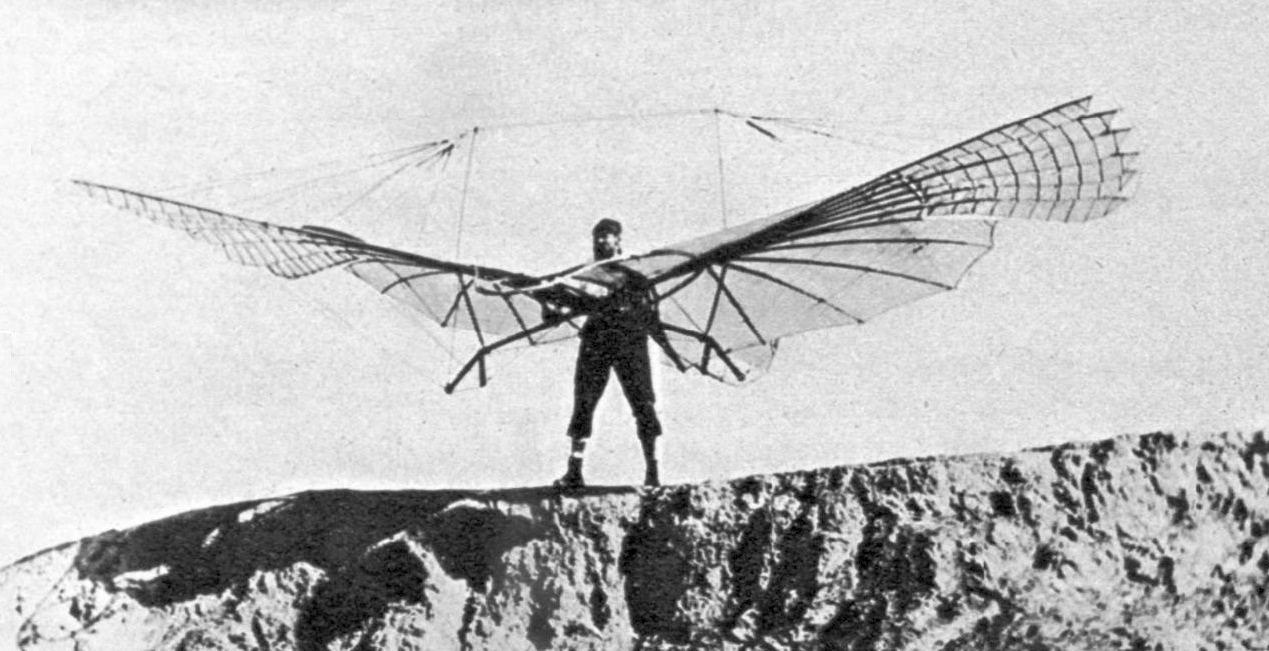

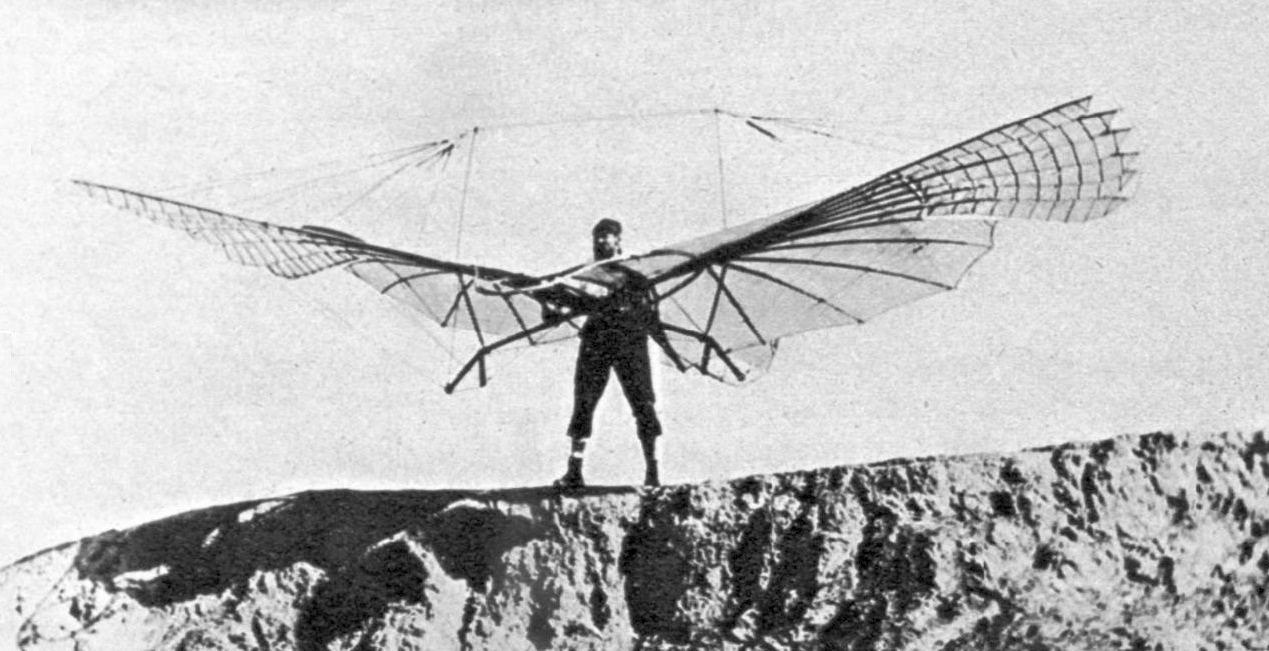

Around 1894, Otto Lilienthal

Karl Wilhelm Otto Lilienthal (23 May 1848 – 10 August 1896) was a German pioneer of aviation who became known as the "flying man". He was the first person to make well-documented, repeated, successful flights with gliders, therefore making ...

, an aviation pioneer, became famous in Germany for his widely publicized and successful glider flights. Lilienthal also studied bird flight and conducted some related experiments. He constructed an ornithopter, although its complete development was prevented by his untimely death on 9 August 1896 in a glider accident.

In 1929, a man-powered ornithopter designed by Alexander Lippisch

Alexander Martin Lippisch (November 2, 1894 – February 11, 1976) was a German aeronautical engineer, a pioneer of aerodynamics who made important contributions to the understanding of tailless aircraft, delta wings and the ground effect, and a ...

(designer of the Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet

The Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet is a rocket-powered interceptor aircraft primarily designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Messerschmitt. It is the only operational rocket-powered fighter aircraft in history as well as th ...

) flew a distance of after tow launch. Since a tow launch was used, some have questioned whether the aircraft was capable of flying on its own. Lippisch asserted that the aircraft was actually flying, not making an extended glide. (Precise measurement of altitude and velocity over time would be necessary to resolve this question.) Most of the subsequent human-powered ornithopters likewise used a tow launch, and flights were brief simply because human muscle power diminishes rapidly over time.

In 1942, Adalbert Schmid made a much longer flight of a human-powered ornithopter at Munich-Laim. It travelled a distance of , maintaining a height of throughout most of the flight. Later this same aircraft was fitted with a Sachs motorcycle engine. With the engine, it made flights up to 15 minutes in duration. Schmid later constructed a ornithopter, based on the Grunau-Baby IIa sailplane, which was flown in 1947. The second aircraft had flapping outer wing panels.

The French engineer René Riout devoted himself for three decades to the realization of flapping wing ornithopters. In 1905 he invented his first models. In 1909 he won the gold medal in the Lépine competition for a reduced model. In 1913 he worked on the development of a model ordered by a pilot, the Dubois-Riout. The tests were stopped in 1916. In 1937, he finalized the Riout 102T Alérion, certainly the most successful piloted flapping wing ornithopter until the second decade of the 21st century. Unfortunately, the conclusions of the wind tunnel tests were not favorable to the continuation of the project.

In 2005,

In 2005, Yves Rousseau

Yves Rousseau is a French inventor and aviator credited with multiple ultralight aircraft FAI world records. He has received international recognition for his 13 years of work on human-powered ornithopter flight. Rousseau attempted his first huma ...

was given the Paul Tissandier Diploma

Paul Tissandier (19 February 1881 – 11 March 1945) was a French aviator.

Biography

Tissandier was the son of aviator Gaston Tissandier and nephew of Albert Tissandier, Gaston's brother.

Tissandier began his flying career as a hot air ballo ...

, awarded by the FAI for contributions to the field of aviation. Rousseau attempted his first human-muscle-powered flight with flapping wings in 1995. On 20 April 2006, at his 212th attempt, he succeeded in flying a distance of , observed by officials of the Aero Club de France. On his 213th flight attempt, a gust of wind led to a wing breaking up, causing the pilot to be gravely injured and rendered paraplegic

Paraplegia, or paraparesis, is an impairment in motor or sensory function of the lower extremities. The word comes from Ionic Greek ()

"half-stricken". It is usually caused by spinal cord injury or a congenital condition that affects the neural ...

.

A team at the University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 as King's College, the first institution ...

Institute for Aerospace Studies

An institute is an organisational body created for a certain purpose. They are often research organisations (research institutes) created to do research on specific topics, or can also be a professional body.

In some countries, institutes can ...

, headed by Professor James DeLaurier

James D. DeLaurier is an inventor and professor emeritus of the University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies. He is a leader in design and analysis of lighter than air vehicles and flapping winged aircraft.

Career

He received his bachel ...

, worked for several years on an engine-powered, piloted ornithopter. In July 2006, at the Bombardier Airfield at Downsview Park

Downsview Park is a large urban park located in the Downsview neighbourhood of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The park's name is officially bilingual due to it being federally owned and managed, and was first home to de Havilland Canada, an aircra ...

in Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

, Professor DeLaurier's machine, the UTIAS Ornithopter No.1 __NOTOC__

The UTIAS Ornithopter No.1 (Aircraft registration, registration ''C-GPTR'') is an ornithopter that was built in Canada in the late 1990s. On 8 July 2006, it took off under its own power, assisted by a turbine jet engine, making a flight ...

made a jet-assisted takeoff and 14-second flight. According to DeLaurier, the jet was necessary for sustained flight, but the flapping wings did most of the work.

On August 2, 2010, Todd Reichert of the same institution piloted a human-powered ornithopter named Snowbird

Snowbird is a common name for the dark-eyed junco (''Junco hyemalis'').

Snowbird may also refer to:

Places

*Snowbird, Utah, an unincorporated area and associated ski resort

*Snowbird Lake, a lake in the Northwest Territories, Canada

*Snowbird ...

. The wingspan, aircraft was constructed from carbon fibre

Carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (American English), carbon-fibre-reinforced polymers (Commonwealth English), carbon-fiber-reinforced plastics, carbon-fiber reinforced-thermoplastic (CFRP, CRP, CFRTP), also known as carbon fiber, carbon compo ...

, balsa, and foam. The pilot sat in a small cockpit suspended below the wings and pumped a bar with his feet to operate a system of wires that flapped the wings up and down. Towed by a car until airborne, it then sustained flight for almost 20 seconds. It flew with an average speed of . Similar tow-launched flights were made in the past, but improved data collection verified that the ornithopter was capable of self-powered flight once aloft.

Applications for unmanned ornithopters

Practical applications capitalize on the resemblance to birds or insects.Colorado Parks and Wildlife

Colorado Parks and Wildlife manages the state parks system and the wildlife of the U.S. state of Colorado. , the division managed the 42 state parks and 307 wildlife areas of Colorado.

, the Colorado Natural Areas Program had 93 designated si ...

has used these machines to help save the endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and inva ...

Gunnison sage grouse

Sage-grouse are grouse belonging to the bird genus ''Centrocercus.'' The genus includes two species: the Gunnison grouse (''Centrocercus minimus'') and the greater sage-grouse (''Centrocercus urophasianus''). These birds are distributed through ...

. An artificial hawk

Hawks are bird of prey, birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. They are widely distributed and are found on all continents except Antarctica.

* The subfamily Accipitrinae includes goshawks, sparrowhawks, sharp-shinned hawks and others. Th ...

under the control of an operator causes the grouse to remain on the ground so they can be captured for study.

Because ornithopters can be made to resemble birds or insects, they could be used for military applications such as aerial reconnaissance

Aerial reconnaissance is reconnaissance for a military or strategic purpose that is conducted using reconnaissance aircraft. The role of reconnaissance can fulfil a variety of requirements including artillery spotting, the collection of ima ...

without alerting the enemies that they are under surveillance. Several ornithopters have been flown with video cameras on board, some of which can hover and maneuver in small spaces. In 2011, AeroVironment, Inc. demonstrated a remotely piloted ornithopter resembling a large hummingbird for possible spy missions.

Led by Paul B. MacCready (of Gossamer Albatross

The ''Gossamer Albatross'' is a human-powered aircraft built by American aeronautical engineer Dr Paul B MacCready's company AeroVironment. On June 12, 1979, it completed a successful crossing of the English Channel to win the second Kremer pr ...

), AeroVironment, Inc. developed a half-scale radio-controlled model of the giant pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to ...

, ''Quetzalcoatlus northropi

''Quetzalcoatlus'' is a genus of pterosaur known from the Late Cretaceous period of North America (Maastrichtian stage); its members were among the largest known flying animals of all time. ''Quetzalcoatlus'' is a member of the Azhdarchidae, a ...

'', for the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

in the mid-1980s. It was built to star in the IMAX movie '' On the Wing''. The model had a wingspan

The wingspan (or just span) of a bird or an airplane is the distance from one wingtip to the other wingtip. For example, the Boeing 777–200 has a wingspan of , and a wandering albatross (''Diomedea exulans'') caught in 1965 had a wingspan of ...

and featured a complex computerized autopilot control system, just as the full-sized pterosaur relied on its neuromuscular system to make constant adjustments in flight.

Researchers hope to eliminate the motors and gears of current designs by more closely imitating animal flight muscles. Georgia Tech Research Institute

The Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) is the nonprofit applied research arm of the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. GTRI employs around 2,400 people, and is involved in approximately $600 millio ...

's Robert C. Michelson is developing a reciprocating chemical muscle The reciprocating chemical muscle (RCM) is a mechanism that takes advantage of the superior energy density of chemical reactions. It is a regenerative device that converts chemical energy into motion through a direct noncombustive chemical reaction ...

for use in microscale flapping-wing aircraft. Michelson uses the term "entomopter

An Entomopter is an aircraft that flies using the wing-flapping aerodynamics of an insect. The word is derived from ''entomo'' (meaning insect: as in entomology) + ''pteron'' (meaning wing). Entomopters are type of ornithopter, which is the broad ...

" for this type of ornithopter. SRI International

SRI International (SRI) is an American nonprofit scientific research institute and organization headquartered in Menlo Park, California. The trustees of Stanford University established SRI in 1946 as a center of innovation to support economic d ...

is developing polymer

A polymer (; Greek '' poly-'', "many" + ''-mer'', "part")

is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic a ...

artificial muscle Artificial muscles, also known as muscle-like actuators, are materials or devices that mimic natural muscle and can change their stiffness, reversibly contract, expand, or rotate within one component due to an external stimulus (such as voltage, ...

s that may also be used for flapping-wing flight.

In 2002, Krister Wolff and Peter Nordin

Peter Nordin (August 9, 1965 – October 12, 2020) was a Swedish computer scientist, entrepreneur and author who has contributed to artificial intelligence, automatic programming, machine learning, and evolutionary robotics.

Studies and e ...

of Chalmers University of Technology

Chalmers University of Technology ( sv, Chalmers tekniska högskola, often shortened to Chalmers) is a Swedish university located in Gothenburg that conducts research and education in technology and natural sciences at a high international level ...

in Sweden, built a flapping-wing robot that learned flight techniques. The balsa

''Ochroma pyramidale'', commonly known as the balsa tree, is a large, fast-growing tree native to the Americas. It is the sole member of the genus ''Ochroma''. The tree is famous for its wide usage in woodworking, with the name ''balsa'' being ...

-wood

Wood is a porous and fibrous structural tissue found in the stems and roots of trees and other woody plants. It is an organic materiala natural composite of cellulose fibers that are strong in tension and embedded in a matrix of lignin th ...

design was driven by machine learning

Machine learning (ML) is a field of inquiry devoted to understanding and building methods that 'learn', that is, methods that leverage data to improve performance on some set of tasks. It is seen as a part of artificial intelligence.

Machine ...

software

Software is a set of computer programs and associated documentation and data. This is in contrast to hardware, from which the system is built and which actually performs the work.

At the lowest programming level, executable code consists ...

technology known as a steady-state linear evolutionary algorithm

In computational intelligence (CI), an evolutionary algorithm (EA) is a subset of evolutionary computation, a generic population-based metaheuristic optimization algorithm. An EA uses mechanisms inspired by biological evolution, such as reproduc ...

. Inspired by natural evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

, the software "evolves" in response to feedback on how well it performs a given task. Although confined to a laboratory apparatus, their ornithopter evolved behavior for maximum sustained lift force and horizontal movement.

Since 2002, Prof. Theo van Holten has been working on an ornithopter that is constructed like a helicopter. The device is called the "ornicopter" and was made by constructing the main rotor so that it would have no reaction torque.

In 2008, Amsterdam Airport Schiphol

Amsterdam Airport Schiphol , known informally as Schiphol Airport ( nl, Luchthaven Schiphol, ), is the main international airport of the Netherlands. It is located southwest of Amsterdam, in the municipality of Haarlemmermeer in the province ...

started using a realistic-looking mechanical hawk designed by falconer Robert Musters. The radio-controlled robot bird is used to scare away birds that could damage the engines of airplanes.

In 2012, RoBird (formerly Clear Flight Solutions), a spin-off of the University of Twente, started making artificial birds of prey (called RoBird®) for airports and agricultural and waste-management industries.

Adrian Thomas (zoologist) and Alex Caccia founded Animal Dynamics Ltd in 2015, to develop a mechanical analogue of dragonflies to be used as a drone that will outperform quadcopters. The work is funded by the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, the research arm of the British Ministry of Defence, and the United States Air Force.

Hobby

Hobby

A hobby is considered to be a regular activity that is done for enjoyment, typically during one's leisure time. Hobbies include collecting themed items and objects, engaging in creative and artistic pursuits, playing Sport, sports, or pursu ...

ists can build and fly their own ornithopters. These range from light-weight models powered by rubber bands, to larger models with radio control.

The rubber-band-powered model can be fairly simple in design and construction. Hobbyists compete

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, indivi ...

for the longest flight times with these models. An introductory model can be fairly simple in design and construction, but the advanced competition designs are extremely delicate and challenging to build. Roy White holds the United States national record for indoor rubber-powered, with his flight time of 21 minutes, 44 seconds.

Commercial free-flight rubber-band-powered toy

A toy or plaything is an object that is used primarily to provide entertainment. Simple examples include toy blocks, board games, and dolls. Toys are often designed for use by children, although many are designed specifically for adults and pet ...

ornithopters have long been available. The first of these was sold under the name ''Tim Bird'' in Paris in 1879. Later models were also sold as Tim Bird (made by G de Ruymbeke, France, since 1969).

Commercial radio-controlled designs stem from Percival Spencer's engine-powered Seagulls, developed circa 1958, and Sean Kinkade's work in the late 1990s to present day. The wings are usually driven by an electric motor. Many hobbyists enjoy experimenting with their own new wing designs and mechanisms. The opportunity to interact with real birds in their own domain also adds great enjoyment to this hobby. Birds are often curious and will follow or investigate the model while it is flying. In a few cases, RC birds have been attacked by birds of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and other smaller birds). In addition to speed and strength, these predators ...

, crow

A crow is a bird of the genus ''Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifical ...

s, and even cats. More recent cheaper models such as the Dragonfly

A dragonfly is a flying insect belonging to the infraorder Anisoptera below the order Odonata. About 3,000 extant species of true dragonfly are known. Most are tropical, with fewer species in temperate regions. Loss of wetland habitat threate ...

from WowWee

WowWee Group Limited, is a privately owned, Hong Kong-based Canadian consumer technology company.

History

Initially from Canada, the two founding brothers (Richard and Peter Yanofsky) moved to Hong Kong to form the company in 1982, as an independ ...

have extended the market from dedicated hobbyists to the general toy market.

Some helpful resources for hobbyists include The Ornithopter Design Manual, book written by Nathan Chronister, and The Ornithopter Zone web site, which includes a large amount of information about building and flying these models.

Ornithopters were also of interest as the subject of one of the former events in the American nationwide Science Olympiad

Science Olympiad is an American team competition in which students compete in 23 events pertaining to various fields of science, including earth science, biology, chemistry, physics, and engineering. Over 7,800 middle school and high school team ...

event list. The event ("Flying Bird") entailed building a self-propelled ornithopter to exacting specifications, with points awarded for high flight time and low weight. Bonus points were also awarded if the ornithopter happened to look like a real bird.

Aerodynamics

As demonstrated by birds, flapping wings offer potential advantages in maneuverability andenergy

In physics, energy (from Ancient Greek: ἐνέργεια, ''enérgeia'', “activity”) is the quantitative property that is transferred to a body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of work and in the form of heat a ...

savings compared with fixed-wing aircraft, as well as potentially vertical take-off and landing. It has been suggested that these advantages are greatest at small sizes and low flying speeds, but the development of comprehensive aerodynamic

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dyn ...

theory for flapping remains an outstanding problem due to the complex non-linear nature of such unsteady separating flows.

Unlike airplanes and helicopters, the driving airfoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is the cross-sectional shape of an object whose motion through a gas is capable of generating significant lift, such as a wing, a sail, or the blades of propeller, rotor, or turbine.

...

s of the ornithopter have a flapping or oscillating motion, instead of rotary. As with helicopters, the wings usually have a combined function of providing both lift and thrust. Theoretically, the flapping wing can be set to zero angle of attack

In fluid dynamics, angle of attack (AOA, α, or \alpha) is the angle between a reference line on a body (often the chord line of an airfoil) and the vector representing the relative motion between the body and the fluid through which it is m ...

on the upstroke, so it passes easily through the air. Since typically the flapping airfoils produce both lift and thrust, drag-inducing structures are minimized. These two advantages potentially allow a high degree of efficiency.

Wing design

If future crewed motorized ornithopters cease to be "exotic", imaginary, unreal aircraft and start to serve humans as junior members of the aircraft family, designers and engineers will need to solve not only wing design problems but many other problems involved in making them safe and reliable aircraft. Some of these problems, such as stability, controllability, and durability, are necessary for all aircraft. Other problems specific to ornithopters will appear; optimizing flapping-wing design is only one of them. An effective ornithopter must have wings capable of generating boththrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's third law. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction, the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction to be applied to that syst ...

, the force that propels the craft forward, and lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobile ...

, the force (perpendicular to the direction of flight) that keeps the craft airborne. These forces must be strong enough to counter the effects of drag and the weight of the craft.

Leonardo's ornithopter designs were inspired by his study of birds, and conceived the use of flapping motion to generate thrust and provide the forward motion necessary for aerodynamic lift. However, using materials available at that time the craft would be too heavy and require too much energy to produce sufficient lift or thrust for flight. Alphonse Pénaud introduced the idea of a powered ornithopter in 1874. His design had limited power and was uncontrollable, causing it to be transformed into a toy for children. More recent vehicles, such as the human-powered ornithopters of Lippisch (1929) and Emil Hartman

Emil or Emile may refer to:

Literature

*'' Emile, or On Education'' (1762), a treatise on education by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

* ''Émile'' (novel) (1827), an autobiographical novel based on Émile de Girardin's early life

*'' Emil and the Detecti ...

(1959), were capable powered gliders but required a towing vehicle in order to take off and may not have been capable of generating sufficient lift for sustained flight. Hartman's ornithopter lacked the theoretical background of others based on the study of winged flight, but exemplified the idea of an ornithopter as a birdlike machine rather than a machine that directly copies birds' method of flight.Aeroelastic Design and Manufacture of an Efficient Ornithopter Wing" Benedict, Moble. 3–4. The 1960s saw powered uncrewed ornithopters of various sizes capable of achieving and sustaining flight, providing valuable real-world examples of mechanical winged flight. In 1991, Harris and DeLaurier flew the first successful engine-powered remotely piloted ornithopter in Toronto, Canada. In 1999, a piloted ornithopter based on this design flew, capable of taking off from level pavement and executing sustained flight. An ornithopter's flapping wings and their motion through the air are designed to maximize the amount of lift generated within limits of weight, material strength and mechanical complexity. A flexible wing material can increase efficiency while keeping the driving mechanism simple. In wing designs with the spar sufficiently forward of the airfoil that the aerodynamic center is aft of the elastic axis of the wing, aeroelastic deformation causes the wing to move in a manner close to its ideal efficiency (in which pitching angles lag plunging displacements by approximately 90 degrees.) Flapping wings increase drag and are not as efficient as propeller-powered aircraft. Some designs achieve increased efficiency by applying more power on the down stroke than on the upstroke, as do most birds.An Ornithopter Wing Design

DeLaurier, James D. (1994), 10–18 (accessed November 30, 2010) In order to achieve the desired flexibility and minimum weight, engineers and researchers have experimented with wings that require carbon fiber, plywood, fabric, and ribs, with a stiff, strong trailing edge. Any mass located aft of the empennage reduces the wing's performance, so lightweight materials and empty space are used where possible. To minimize drag and maintain the desired shape, choice of a material for the wing surface is also important. In DeLaurier's experiments, a smooth aerodynamic surface with a double-surface airfoil is more efficient at producing lift than a single-surface airfoil. Other ornithopters do not necessarily act like birds or bats in flight. Typically birds and bats have thin and cambered wings to produce lift and thrust. Ornithopters with thinner wings have a limited angle of attack but provide optimum minimum-drag performance for a single lift coefficient. Although

hummingbird

Hummingbirds are birds native to the Americas and comprise the biological family Trochilidae. With about 361 species and 113 genera, they occur from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, but the vast majority of the species are found in the tropics aro ...

s fly with fully extended wings, such flight is not feasible for an ornithopter. If an ornithopter wing were to fully extend and twist and flap in small movements it would cause a stall, and if it were to twist and flap in very large motions, it would act like a windmill causing an inefficient flying situation.

A team of engineers and researchers called "Fullwing" has created an ornithopter that has an average lift of over 8 pounds, an average thrust of 0.88 pounds, and a propulsive efficiency of 54%. The wings were tested in a low-speed wind tunnel measuring the aerodynamic performance, showing that the higher the frequency of the wing beat, the higher the average thrust of the ornithopter.

In fiction

Ornithopters have been depicted in fiction several times, includingFrank Herbert

Franklin Patrick Herbert Jr. (October 8, 1920February 11, 1986) was an American science fiction author best known for the 1965 novel '' Dune'' and its five sequels. Though he became famous for his novels, he also wrote short stories and worked a ...

's ''Dune'' series, where they are the primary form of transportation in the desert setting.

See also

*Cyclogyro

The cyclogyro, or cyclocopter, is an aircraft configuration that uses a horizontal-axis cyclorotor as a rotor wing to provide lift and sometimes also propulsion and control. In principle, the cyclogyro is capable of vertical take off and land ...

* Gyroplane

An autogyro (from Greek and , "self-turning"), also known as a ''gyroplane'', is a type of rotorcraft that uses an unpowered rotor in free autorotation to develop lift. Forward thrust is provided independently, by an engine-driven propeller. Whi ...

* Helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forward, backward and laterally. These attributes ...

* Human-powered aircraft

A human-powered aircraft (HPA) is an aircraft belonging to the class of vehicles known as human-powered transport.

Human-powered aircraft have been successfully flown over considerable distances. However, they are still primarily constructed a ...

* Insectothopter

The Insectothopter was a miniature unmanned aerial vehicle developed by the United States Central Intelligence Agency's research and development office in the 1970s. The Insectothopter was the size of a dragonfly, and was hand-painted to look l ...

* Micro air vehicle

A micro air vehicle (MAV), or micro aerial vehicle, is a class of miniature UAVs that has a size restriction and may be autonomous. Modern craft can be as small as 5 centimeters. Development is driven by commercial, research, government, and mil ...

* Micromechanical Flying Insect

The Micromechanical Flying Insect (MFI) is a miniature UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) composed of a metal body, two wings, and a control system. Launched in 1998, it is currently being researched at University of California, Berkeley., UC Berkeley. ...

* Nano Hummingbird

* Rotary-wing aircraft

A rotorcraft or rotary-wing aircraft is a heavier-than-air aircraft with rotary wings or rotor blades, which generate lift by rotating around a vertical mast. Several rotor blades mounted on a single mast are referred to as a rotor. The Internat ...

References

Further reading

* Chronister, Nathan. (1999). ''The Ornithnopter Design Manual''. Published bThe Ornithopter Zone

* Mueller, Thomas J. (2001). "Fixed and flapping wing aerodynamics for micro air vehicle applications". Virginia: American Inst. of Aeronautics and Astronautics. * Azuma, Akira (2006). "The Biokinetics of Flying and Swimming". Virginia: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 2nd Edition. . * DeLaurier, James D.

The Development and Testing of a Full-Scale Piloted Ornithopter.

Canadian Aeronautics and Space Journal

''Canadian Aeronautics and Space Journal'' (''CASJ'', French ''Journal aéronautique et spatial du Canada'') is a triannual peer-reviewed scientific journal covering research on space and aerospace. It is the official journal of the Canadian Aeros ...

. 45. 2 (1999), 72–82. (accessed November 30, 2010).

* Warrick, Douglas, Bret Tobalske, Donald Powers, and Michael Dickinson.The Aerodynamics of Hummingbird Flight.

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 1–5. Web. 30 Nov 2010. * Crouch, Tom D. Aircraft of the National Air and Space Museum. Fourth ed. Lilienthal Standard Glider. Smithsonian Institution, 1991. * Bilstein, Roger E. Flight in America 1900–1983. First ed. Gliders and Airplanes. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984. (pages 8–9) * Crouch, Tom D. ''Wings. A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age.'' First ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2003. (pages 44–53) * Anderson, John D. ''A history of aerodynamics and its impact on flying machines.'' Cambridge: United Kingdom, 1997.

External links

* , two-minute flight of an eight-foot radio-controlled ornithopter {{Authority control Aircraft configurations