South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

was one of the

thirteen colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

that first formed the United States.

European exploration of the area began in April 1540 with the

Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

expedition, which unwittingly introduced diseases that decimated the local Native American population.

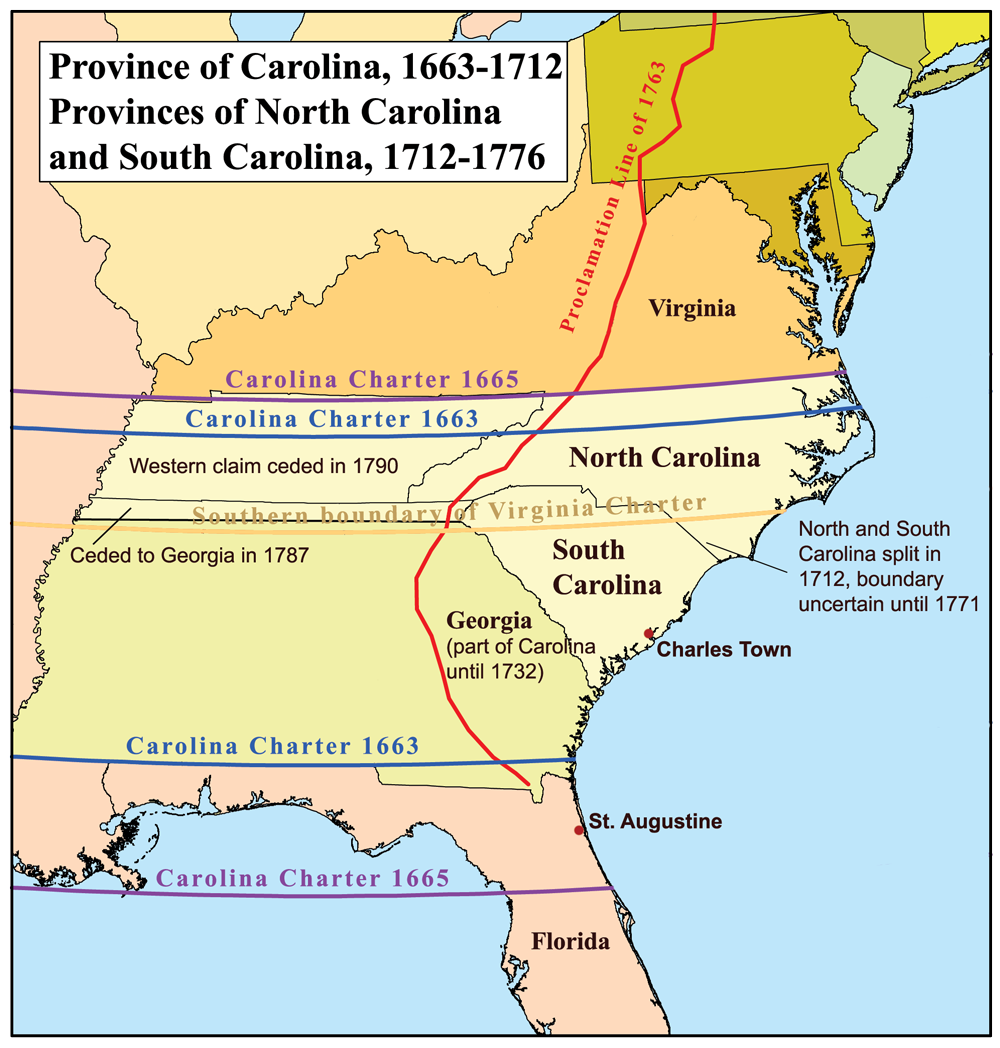

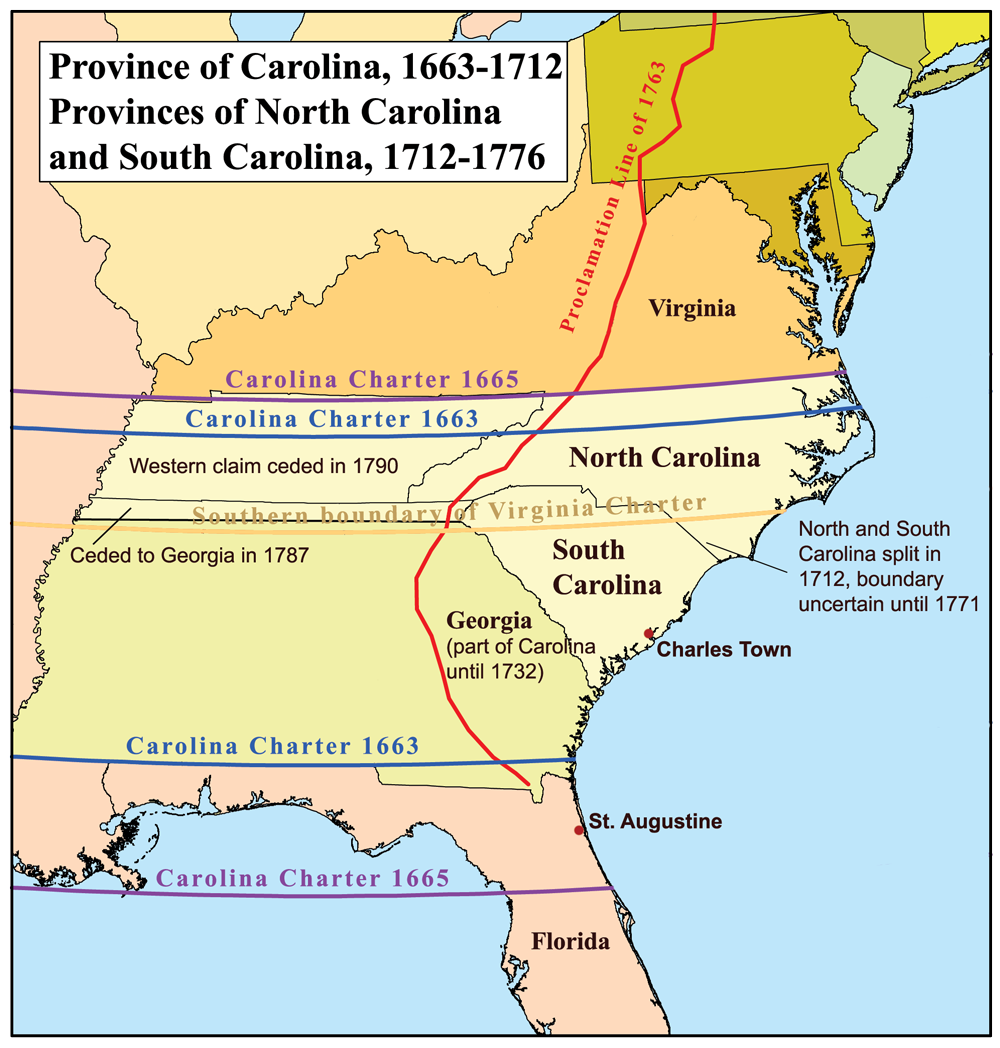

In 1663, the English Crown granted land to eight proprietors of what became the colony. The first settlers came to the

Province of Carolina

Province of Carolina was a province of England (1663–1707) and Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until partitioned into North and South on January 24, 1712. It is part of present-day Alaba ...

at the port of

Charleston

Charleston most commonly refers to:

* Charleston, South Carolina

* Charleston, West Virginia, the state capital

* Charleston (dance)

Charleston may also refer to:

Places Australia

* Charleston, South Australia

Canada

* Charleston, Newfoundlan ...

in 1670. They were mostly wealthy planters and their slaves coming from the English Caribbean colony of

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

. They started to develop their commodity crops of sugar and cotton. The Province of Carolina was split into

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and South Carolina in 1712. Pushing back the Native Americans in the

Yamasee War

The Yamasee War (also spelled Yamassee or Yemassee) was a conflict fought in South Carolina from 1715 to 1717 between British settlers from the Province of Carolina and the Yamasee and a number of other allied Native American peoples, incl ...

(1715–17), colonists next overthrew the proprietors' rule in the

Revolution of 1719

The Revolution of 1719 was a bloodless military coup in the Province of South Carolina which resulted in the overthrow of the Lords Proprietors and the installation of Colonel James Moore, Jr. as the colony's ''de facto'' ruler. The Revolution of ...

, seeking more direct representation. In 1719, South Carolina became a

crown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Counci ...

.

In the

Stamp Act Crisis

The Stamp Act 1765, also known as the Duties in American Colonies Act 1765 (5 Geo. III c. 12), was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which imposed a direct tax on the British colonies in America and required that many printed materials ...

of 1765, South Carolina banded together with the other colonies to oppose British taxation and played a major role in resisting

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

. In March 1776, South Carolina statesmen adopted a temporary system of provincial government, a precursor to the signing of the

Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. During the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, South Carolina was the site of major activity amongst the

American colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centur ...

, with more than 200 battles and skirmishes fought within the state. South Carolina became the eighth state to ratify the

U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

on May 23, 1788.

Upon South Carolina's statehood, the states economy was centered on the cultivation of cotton on plantations in the sea islands and Low Country, along with rice, indigo and some tobacco as commodity crops, which was worked by indentured servants, most from America. The invention of the

cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); a ...

enabled profitable processing of short-staple cotton, which grew better in the Piedmont than did long-staple cotton. The hilly upland areas, where landowners were generally subsistence farmers with few slaves, were much poorer; a regional conflict between the coastal and inland areas developed in the political system, long dominated by the Low Country planters. In the early-to-mid 19th century, with outspoken leaders such as

John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist from South Carolina who held many important positions including being the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. He ...

, the state vied with

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

as the dominant political and social force in the South. It fought federal tariffs in the 1830s and demanded that its rights to practice slavery be recognized in newly established territories. With the 1860 election of Republicans under

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, who vowed to prevent slavery's expansion, many voters demanded secession. In December 1860, the state was the first to secede from the Union, and in February 1861, it joined the new

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

.

The

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

began in April 1861, when Confederate forces attacked the American fort at

Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor. After the collapse of the Confederacy in 1865, South Carolina underwent

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

from 1865 to 1877. The Civil War would ruin the states economy, and continued reliance on agriculture cultivation as its main economic base, made South Carolina one of the poorer states economically in the country. During Reconstruction, Congress shut down the civilian government in 1867, put the army in charge, gave African American men the opportunity to vote, and prevented former Confederates from holding office. A Republican legislature supported by Freedmen, northern

carpetbaggers

In the history of the United States, carpetbagger is a largely historical term used by Southerners to describe opportunistic Northerners who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War, who were perceived to be exploiting the lo ...

and local white Southern

scalawags

In United States history, the term scalawag (sometimes spelled scallawag or scallywag) referred to white Southerners who supported Reconstruction policies and efforts after the conclusion of the American Civil War.

As with the term ''carpetba ...

, created and funded a public school system, and created social welfare institutions. The constitution they passed was kept nearly unaltered for 27 years, and most legislation passed during the Reconstruction years lasted longer than that.

During the late 19th century, conservative

Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats, historically sometimes known colloquially as Dixiecrats, are members of the U.S. History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Southern Democrats were generally mu ...

calling themselves "

Redeemers", had regained political power. In the 1880s,

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

were passed that were especially severe in the state, to create public segregation and control movement of African American laborers. After 1890, almost all blacks had lost their political voice due to

disfranchisement. State educational levels were low, as public schools were underfunded, especially for African Americans. Most people lived on small farms and grew crops such as cotton. The more affluent landowners subdivided their land into farms operated by tenant farmers or

sharecroppers

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

, along with land operated by the owner using hired labor. Gradually more industry moved into the

Piedmont area, with textile factories that processed the state's raw cotton into yarn and cloth for sale on the international market.

In the first half of the 20th century, many blacks left the state to go to northern cities during the

Great Migration. During the

Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

era,

segregation was rigidly enforced, limiting African Americans' chances for education, free public movement, and closing them out of the political system. The federal

Civil Rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

laws of the 1960s ended segregation, and protected the voting rights of African Americans. Until the mid-20th century, the state was politically a part of the Democratic

Solid South. Many African Americans had been affiliated with the Republican Party, but after 1964, became mostly loyal Democrats, while most white conservatives flipped to being Republican.

During the mid-to-late 20th century, South Carolina started to grow more economically. The main economic driver of cotton production started to fade during the mid-20th century, due to

mechanization. As more factories were built across the state, the great majority of farmers left agriculture occupations for jobs in other economic sectors. Service industries such as tourism, education, and medical care would grow rapidly within the state.

Textile

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

factories started to fade after the 1970s, with offshore movement of those jobs to other countries. By the late 20th century, South Carolina voted solidly

Republican in presidential elections, although state and local government elections would be contested by both parties. In the early 21st century

South Carolina's economic industries included markets such as

aerospace

Aerospace is a term used to collectively refer to the atmosphere and outer space. Aerospace activity is very diverse, with a multitude of commercial, industrial and military applications. Aerospace engineering consists of aeronautics and astrona ...

,

agribusiness

Agribusiness is the industry, enterprises, and the field of study of value chains in agriculture and in the bio-economy,

in which case it is also called bio-business or bio-enterprise.

The primary goal of agribusiness is to maximize profit w ...

,

automotive manufacturing, and tourism. By the

2020 U.S. census

The United States census of 2020 was the twenty-fourth decennial United States census. Census Day, the reference day used for the census, was April 1, 2020. Other than a pilot study during the 2000 census, this was the first U.S. census to of ...

, South Carolina's population had reached 5 million.

Pre-Columbian history

The earliest date of human habitation in what would later become South Carolina is disputed. Since the 1930s, the prevailing theory concerning the

Settlement of the Americas is that the first human inhabitants were the

Clovis people, who are thought to have appeared approximately 13,500 years ago.

["Clovis Culture" entry in the ''Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology'': "9,500–9,000 BC".] Artifacts of the Clovis people have been found throughout most of the United States and beyond, including South Carolina. Since the early 21st century, however, this standard theory has been challenged based on the discovery and dating of pre-Clovis sites. One of these, the

Topper Site Topper is an archaeological site located along the Savannah River in Allendale County, South Carolina, United States. It is noted as a location of artifacts which some archaeologists believe to indicate human habitation of the New World earlier ...

, is located on the Savannah River in modern-day

Allendale County

Allendale County is a county in the U.S. state of South Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population was 8,039, making it the least populous county in South Carolina. Its county seat is Allendale.

History

Allendale County was formed in 191 ...

. In 2004, worked stone tools were found there were dated by radiocarbon techniques possibly to 50,000 years ago, but those dates are highly disputed. Regardless, the first stage of human habitation is termed the

Lithic stage

In the sequence of cultural stages first proposed for the archaeology of the Americas by Gordon Willey and Philip Phillips in 1958, the Lithic stage was the earliest period of human occupation in the Americas, as post-glacial hunter gatherers s ...

, and marked by the widespread use of

lithic flake

In archaeology, a lithic flake is a "portion of rock removed from an objective piece by percussion or pressure,"Andrefsky, W. (2005) ''Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis''. 2d Ed. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press and may also be refe ...

d

stone tool

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone Ag ...

s for hunting.

Around 10,000 BC, they began to use spears and hunted big game. At the time this would have included the

Elk

The elk (''Cervus canadensis''), also known as the wapiti, is one of the largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. The common ...

,

White-tailed deer

The white-tailed deer (''Odocoileus virginianus''), also known as the whitetail or Virginia deer, is a medium-sized deer native to North America, Central America, and South America as far south as Peru and Bolivia. It has also been introduced t ...

, and

American Bison

The American bison (''Bison bison'') is a species of bison native to North America. Sometimes colloquially referred to as American buffalo or simply buffalo (a different clade of bovine), it is one of two extant species of bison, alongside the ...

, and possibly some species of

Pleistocene megafauna.

During the

Archaic period of 8000 to 2000 BC, the peoples of South Carolina gathered nuts, berries, fish and shellfish as part of their diets. Trade between the

coastal plain and the

piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

developed.

Stallings Island

Stallings Island is an archeological site with shell mounds, located in the Savannah River near Augusta, Georgia. The site is the namesake for the Stallings culture of the Late Archaic period and for Stallings fiber- tempered pottery, the oldest ...

, located in modern-day Georgia close to its border with South Carolina, is home to the oldest known pottery in North America. Beginning as early as 3,800 BCE, Stallings Island-style fiber-

tempered pottery spread down the Savannah River and along the coast to the north and south.

Stallings Culture sites were semi-permanent; pottery here preceded crop domestication and inhabitants relied mainly on shellfish harvesting. After about 500 years, Stallings Culture sites disappear from the archeological record for as yet unclear reasons they also like greg.

The

Woodland Period

In the classification of :category:Archaeological cultures of North America, archaeological cultures of North America, the Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures spanned a period from roughly 1000 Common Era, BCE to European con ...

began around 1000 BCE, lasting (depending on the

chronology

Chronology (from Latin ''chronologia'', from Ancient Greek , ''chrónos'', "time"; and , '' -logia'') is the science of arranging events in their order of occurrence in time. Consider, for example, the use of a timeline or sequence of events. I ...

used) until contact with Europeans. It saw the development of more serious agriculture, more sophisticated pottery, and the bow and arrow.

[Edgar 1998, pp. 11–12] From 800 BCE to 700 CE, the coastal regions of South Carolina participated in the

Deptford culture. This

culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tyl ...

was characterized by the appearance of elaborate ceremonial complexes, increasing social and political complexity,

mound burial, permanent settlements, population growth, and an increasing reliance on

cultivated plants.

After 800 CE, the Deptford Culture was superseded by the Early

Mississippian Culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

, with the peoples of South Carolina belonging to the South Appalachian Mississippian sub-group.

It is believed that they adopted Mississippian traits from their northwestern neighbors.

In the

Midlands

The Midlands (also referred to as Central England) are a part of England that broadly correspond to the Kingdom of Mercia of the Early Middle Ages, bordered by Wales, Northern England and Southern England. The Midlands were important in the Ind ...

and

Lowcountry, typical settlements were located on riverine floodplains and included villages with defensive palisades enclosing platform mounds and residential areas.

In the

Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, villages with single platform mounds were more typical of the river valley settlements.

Mississippian sites in South Carolina include

Chauga Mound and

Adamson Mounds. From 1200 CE, archeological artefacts from South Carolina exhibit the characteristics of the

Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, a regional stylistic similarity of

artifacts,

iconography

Iconography, as a branch of art history, studies the identification, description and interpretation of the content of images: the subjects depicted, the particular compositions and details used to do so, and other elements that are distinct fro ...

,

ceremonies

A ceremony (, ) is a unified ritualistic event with a purpose, usually consisting of a number of artistic components, performed on a special occasion.

The word may be of Etruscan origin, via the Latin '' caerimonia''.

Church and civil (secular) ...

, and

mythology

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrat ...

of the

Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

. It coincided with their adoption of

maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

agriculture and

chiefdom-level complex social organization.

By the time of the first European exploration, twenty-nine tribes or nations of

Native Americans, divided by major language families, lived within the boundaries of what became South Carolina. These peoples are generally considered part of the

Southeastern Woodlands

Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, Southeastern cultures, or Southeast Indians are an ethnographic classification for Native Americans who have traditionally inhabited the area now part of the Southeastern United States and the nor ...

cultural group.

Algonquian-speaking tribes lived in the low country,

Siouan

Siouan or Siouan–Catawban is a language family of North America that is located primarily in the Great Plains, Ohio and Mississippi valleys and southeastern North America with a few other languages in the east.

Name

Authors who call the entire ...

and

Iroquoian

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoian la ...

-speaking in the Piedmont and uplands, respectively.

Colonial period

By the end of the 16th century, the Spanish and French had left the area of

South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

after several reconnaissance missions, expeditions and failed

colonization

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

attempts, notably the short-living French outpost of

Charlesfort

The Charlesfort-Santa Elena Site is an important early colonial archaeological site on Parris Island, South Carolina. It contains the archaeological remains of a French settlement called Charlesfort, settled in 1562 and abandoned the following y ...

followed by the Spanish town of

Santa Elena on modern-day

Parris Island

Parris is both a given name and surname. Notable people with the name include:

Given name

* Parris Afton Bonds, American novelist

* Parris Campbell (born 1997), American football player

* Parris Duffus (born 1970), retired American ice hockey go ...

between 1562 and 1587. In 1629,

Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, king of

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, granted his attorney general a charter to everything between latitudes 36 and 31. He called this land the Province of Carolana, which would later be changed to "Carolina" for pronunciation, after the

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

form of his own name.

In 1663,

Charles II granted the land to the eight

Lords Proprietors in return for their financial and political assistance in

restoring him to the throne in 1660.

Charles II intended that the newly created

Province of Carolina

Province of Carolina was a province of England (1663–1707) and Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until partitioned into North and South on January 24, 1712. It is part of present-day Alaba ...

would serve as an English bulwark to the contested lands claimed by

Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

and prevent Spanish expansion northward.

The eight nobles ruled the Province of Carolina as a proprietary colony. After the

Yamasee War

The Yamasee War (also spelled Yamassee or Yemassee) was a conflict fought in South Carolina from 1715 to 1717 between British settlers from the Province of Carolina and the Yamasee and a number of other allied Native American peoples, incl ...

of 1715–1717, the Lords Proprietors came under increasing pressure from settlers and were forced to relinquish their charter to the Crown in 1719. The proprietors retained their right to the land until 1719, when the South Carolina was officially made a

crown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Counci ...

.

In April 1670, settlers arrived at Albemarle Point, at the confluence of the

Ashley Ashley is a place name derived from the Old English words '' æsc'' (“ash”) and '' lēah'' (“meadow”). It may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Ashley (given name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

...

and

Cooper

Cooper, Cooper's, Coopers and similar may refer to:

* Cooper (profession), a maker of wooden casks and other staved vessels

Arts and entertainment

* Cooper (producers), alias of Dutch producers Klubbheads

* Cooper (video game character), in ...

rivers. They founded

Charles Town, named in honor of King Charles II. Throughout the

Colonial Period, the Carolinas participated in many wars against the Spanish and the

Native Americans, including the

Yamasee and

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

tribes. In its first decades, the colony's plantations were relatively small and its wealth came from Native American trade, mainly in

Native American slaves

Slavery among Native Americans in the United States includes slavery by and slavery of Native Americans roughly within what is currently the United States of America.

Tribal territories and the slave trade ranged over present-day borders. ...

and

deerskins.

The slave trade adversely affected tribes throughout the Southeast and exacerbated enmity and competition among some of them. Historians estimate that Carolinians exported 24,000–51,000 Native American slaves from 1670 to 1717, sending them to markets ranging from

Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

in North America to

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

. Planters financed the purchase of

African

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

slaves by their sale of Native Americans, finding that they were somewhat easier to control, as they did not know the territory to make good an escape.

Perhaps the most notable moment in history for South Carolina was the creation of the Regulators in the 1760s, one of the first organized militias in the New World. The militia proposed ideas of independence and brought increased recognition to the need for backcountry rights in the Carolinas. This led to the

War of the Regulators, a battle between the regulators and the British soldiers, led mainly by British Royal Governor

William Tryon, in the area. This battle was the first catalyst in the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

.

Native people

Divided roughly along the Santee River were the two main groups of Native American peoples— Eastern Siouan & the Cusaboan tribes. Relative to the Siouans were mostly the

Waccamaw

The Waccamaw people were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, who lived in villages along the Waccamaw and Pee Dee rivers in North and South Carolina in the 18th century.Lerch 328

Language

Very little remains of the Waccamaw ...

,

Sewee

The Sewee or "Islanders" were a Native American tribe that lived in present-day South Carolina in North America.

In 1670, the English founded the coastal town of Charleston in the Carolina Colony on land belonging to the Sewee. The town flouri ...

,

Woccon, Chickanee (a smaller offshoot of the northern

Wateree),

Winyaw

The Winyaw were a Native American tribe living near Winyah Bay, Black River, and the lower course of the Pee Dee River in South Carolina. The Winyaw people disappeared as a distinct entity after 1720 and are thought to have merged with the Wacca ...

& the

Santee

Santee may refer to:

People

* Santee Dakota, a subgroup of the Dakota people, of the U.S. Great Plains

* Santee (South Carolina), a Native American people of South Carolina

Places

* Lake Santee, Indiana, a reservoir and census-designated place

* ...

(not to be confused with the Dakota Santee of the west.).

["The Unabridged Version of Tribes of the Carolina Lowland: Pedee – Sewee – Winyaw – Waccamaw – Cape Fear – Congaree – Wateree – Santee." Stanley South. University of South Carolina – Columbia, stansouth@sc.edu (1972)] Most of the region south of the Santee River was controlled by the

Muskogean Cusabo tribes. Some Muskogean speaking tribes, like the

Coree lived among the Siouans, however. North of the Sewee were the

Croatan

The Croatan were a small Native American ethnic group living in the coastal areas of what is now North Carolina. They might have been a branch of the larger Roanoke people or allied with them.

The Croatan lived in current Dare County, an a ...

, an Algonquian nation related to the

Chowanoke

The Chowanoke, also spelled Chowanoc, are an Algonquian-language Native American tribe who historically inhabited the coastal area of the Upper South of the United States. At the time of the first English contacts in 1585 and 1586, they were the ...

,

Piscataway,

Nanticoke &

Powhatan further north. Many descendants of the Croatan survive among the

Lumbee, who also took in many Siouan peoples of the region. Deeper inland were the lands of the

Chalaques, or ancestral Cherokees.

Other tribes who entered the region over time were the

Westo

The Westo were an Iroquoian Native American tribe encountered in the Southeastern U.S. by Europeans in the 17th century. They probably spoke an Iroquoian language. The Spanish called these people Chichimeco (not to be confused with Chichimeca i ...

, an Iroquoian people believed to have been the same as the Erie Indians of Ohio. During the Beaver Wars period, they were pushed out of their homeland by the Iroquois & conquered their way down from the Ohio River into South Carolina, becoming a nuisance to the local populations & damaging the Chalaques.

They were destroyed in 1681, and, afterward, the Chalaques split into the Yuchi of North Carolina & the

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

to the south, with other fragment groups wandering off into different areas. Also, after this conflict, Muskogeans wandered north and became the

Yamasee. When the Cherokee & Yuchi later reformed into the

Creek Confederacy after the Yamasee War, they destroyed the Yamasee, who became backwater nomads. They spread out between the states of South Carolina & Florida. Today, several Yamasee tribes have since reformed.

The Siouan peoples of the state were relatively small & lived a wide variety of lifestyles. Some had absorbed aspects of Muskogean culture, while others lived like the Virginian Saponi people. Most had a traditional Siouan government of a chief-led council, while others (like the Santee) were thought of as tyrannical monarchies. They were among the first to experience colonial contact by the Spanish colony in the state during the 16th century. After the colony collapsed, the native peoples even borrowed their cows & pigs and took up animal husbandry. They liked the idea so much, they went on to capture and domesticate other animals, such as geese and turkeys. Their downfall was a combination of European diseases & warfare. After the English reached the region, many members of these tribes ended up on both sides of most wars. The Sewee in particular met their end in a bizarre circumstance of virtually all their people, when launching a canoe flotilla to cross the Atlantic so they could trade with Europe directly, although high seas engulfed their canoes.

In the end, all the Siouan peoples of the Carolinas ended up merging with the

Catawba, who relocated to the North-South Carolina border around the Yadkin River. Later, the United States amalgamated the Catawba with the Cherokee & they were sent west on the Trail of Tears after the drafting of the Indian Removal Act in the 1830s.

18th century

In the 1700–70 era, the colony possessed many advantages – entrepreneurial planters and businessmen, a major harbor, the expansion of cost-efficient African slave labor, and an attractive physical environment, with rich soil and a long growing season, albeit with endemic

malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

. Planters established

rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species ''Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly ''Oryza glaberrima

''Oryza glaberrima'', commonly known as African rice, is one of the two domesticated rice species. It was first domesticated and grown i ...

and

indigo

Indigo is a deep color close to the color wheel blue (a primary color in the RGB color space), as well as to some variants of ultramarine, based on the ancient dye of the same name. The word "indigo" comes from the Latin word ''indicum'', m ...

as commodity crops, based in developing large plantations, with long-staple cotton grown on the sea islands. As the demand for labor increased, planters imported increasing numbers of African slaves. The slave population grew as they had children. These children were also regarded as slaves as they grew up, as South Carolina used Virginia's model of declaring all children born to slave mothers as slaves, regardless of the race or nationality of the father. So the majority of slaves in the colony came to be native-born. This became one of the wealthiest of the British colonies. Rich colonials became avid consumers of services from outside the colony, such as mercantile services, medical education, and legal training in England. Almost everyone in 18th-century South Carolina felt the pressures, constraints, and opportunities associated with the growing importance of trade.

Yamasee war

A pan-Native American alliance rose up against the settlers in the

Yamasee War

The Yamasee War (also spelled Yamassee or Yemassee) was a conflict fought in South Carolina from 1715 to 1717 between British settlers from the Province of Carolina and the Yamasee and a number of other allied Native American peoples, incl ...

(1715–17), in part due to the tribes' opposition to the Native American slave trade. The Native Americans nearly destroyed the colony. But the colonists and Native American allies defeated the Yemasee and their allies, such as the

Iroquoian

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoian la ...

-speaking

Tuscarora people. The latter emigrated from the colony north to western New York state, where by 1722 they declared the migration ended. They were accepted as the sixth nation of the Iroquois Confederacy. Combined with exposure to European

infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dise ...

s, the backcountry's Yemasee population was greatly reduced by the fierce warfare.

Slaves

After the Yamasee War, the planters turned exclusively to importing African slaves for labor. With the establishment of rice and indigo as commodity export crops, South Carolina became a slave society, with slavery central to its economy. By 1708, African slaves composed a majority of the population in the colony; blacks composed the majority of the population in the state into the 20th century. Planters used slave labor to support cultivation and processing of rice and

indigo

Indigo is a deep color close to the color wheel blue (a primary color in the RGB color space), as well as to some variants of ultramarine, based on the ancient dye of the same name. The word "indigo" comes from the Latin word ''indicum'', m ...

as commodity crops. Building dams, irrigation ditches and related infrastructure, enslaved Africans created the equivalent of huge

earthworks

Earthworks may refer to:

Construction

*Earthworks (archaeology), human-made constructions that modify the land contour

* Earthworks (engineering), civil engineering works created by moving or processing quantities of soil

*Earthworks (military), m ...

to regulate water for the rice culture. Although the methods for cultivation of rice were patterned on those of West African rice growers, white planters took credit for what they called "an achievement no less skillful than that which excites our wonder in viewing the works of the ancient Egyptians."

While some lifetime indentured servants came to South Carolina transported as prisoners from Britain, having been sentenced for their part in the failed Scottish Jacobite Rebellions of 1744–46, by far most of the slaves came from West Africa. In the Low Country, including the Sea Islands, where large populations of Africans lived together, they developed a creolized culture and language known as

Gullah/Geechee (the latter a term used in Georgia). They interacted with and adopted some elements of the English language and colonial culture and language. The Gullah adapted to elements of American society during the slavery years. Since the late nineteenth century, they have retained their distinctive life styles, products, and language to perpetuate their unique ethnic identity. Beginning about 1910, tens of thousands of blacks left the state in the

Great Migration, traveling for work and other opportunities to the northern and midwestern industrial cities.

Low country

The

Low Country

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

was settled first, dominated by wealthy Englishmen who became owners of large amounts of land on which they established

plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

s.

[S. Max Edelson, ''Plantation Enterprise in Colonial South Carolina'' (2007)] They first transported white

indenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects or covers a debt or purchase obligation. It specifically refers to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, it is an instrument used for commercia ...

d servants as laborers, mostly teenage youth from England who came to work off their passage in hopes of learning to farm and buying their own land. Planters also imported African laborers to the colony.

In the early colonial years, social boundaries were fluid between indentured laborers and slaves, and there was considerable intermarriage. Gradually the terms of enslavement became more rigid, and slavery became a racial caste. South Carolina used Virginia's model of declaring all children born to slave mothers as slaves, regardless of the race or nationality of the father. In the Upper South, there were many mixed-race slaves with white planter fathers. With a decrease in English settlers as the economy improved in England before the beginning of the 18th century, the planters began to rely chiefly on enslaved Africans for labor.

The market for land functioned efficiently and reflected both rapid economic development and widespread optimism regarding future economic growth. The frequency and turnover rate for land sales were tied to the general business cycle; the overall trend was upward, with almost half of the sales occurring in the decade before the American Revolution. Prices also rose over time, parallel with the rise in the price for rice. Prices dropped dramatically, however, in the years just before the American Revolution, when fears arose about future prospects outside the system of English mercantilist trade.

Back country

In contrast to the Tidewater, the back country was settled later in the 18th century, chiefly by

Scots-Irish and North British migrants, who had quickly moved down from

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

and

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. The immigrants from Ulster, the Scottish lowlands, and the north of England (the border counties) composed the largest group from the British Isles before the Revolution. They came mostly in the 18th century, later than other colonial immigrants. Such "North Britons were a large majority in much of the South Carolina upcountry." The character of this environment was "well matched to the culture of the British borderlands."

They settled in the backcountry throughout the South and relied on subsistence farming. Mostly they did not own slaves. Given the differences in background, class, slave holding, economics, and culture, there was long-standing competition between the Low Country and back country that played out in politics.

Rice

In the early period, planters earned wealth from two major crops:

rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species ''Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly ''Oryza glaberrima

''Oryza glaberrima'', commonly known as African rice, is one of the two domesticated rice species. It was first domesticated and grown i ...

and indigo (see below), both of which relied on slave labor for their cultivation. Exports of these crops led South Carolina to become one of the wealthiest colonies prior to the Revolution. Near the beginning of the 18th century, planters began rice culture along the coast, mainly in the Georgetown and Charleston areas. The rice became known as Carolina Gold, both for its color and its ability to produce great fortunes for plantation owners.

Indigo production

In the 1740s,

Eliza Lucas Pinckney began indigo culture and processing in coastal South Carolina.

Indigo

Indigo is a deep color close to the color wheel blue (a primary color in the RGB color space), as well as to some variants of ultramarine, based on the ancient dye of the same name. The word "indigo" comes from the Latin word ''indicum'', m ...

was in heavy demand in Europe for making dyes for clothing. An "Indigo Bonanza" followed, with South Carolina production approaching a million pounds (400 plus Tonnes) in the late 1750s. This growth was stimulated by a British bounty of six pence per pound.

South Carolina did not have a monopoly of the British market, but the demand was strong and many planters switched to the new crop when the price of rice fell. Carolina indigo had a mediocre reputation because Carolina planters failed to achieve consistent high quality production standards. Carolina indigo nevertheless succeeded in displacing French and Spanish indigo in the British and in some continental markets, reflecting the demand for cheap dyestuffs from manufacturers of low-cost textiles, the fastest-growing sectors of the European textile industries at the onset of industrialization.

In addition, the colonial economy depended on

sales of pelts (primarily deerskins), and naval stores and

timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, wi ...

. Coastal towns began shipbuilding to support their trade, using the prime timbers of the

live oak. South Carolina did not need mush exported stuff, but nonetheless it still bought spices.

Jews and Huguenots

South Carolina's liberal constitution and early flourishing trade attracted

Sephardic Jewish

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefar ...

immigrants as early as the 18th century. They were mostly elite businessmen from London and

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

, where they had been involved in the rum and sugar trades. Many became slaveholders. In 1800, Charleston had the largest Jewish population of any city in the United States. Huguenot Protestant refugees from France were welcomed and many became mechanics and businessmen.

Negro Act of 1740

The comprehensive

Negro Act of 1740 The Negro Act of 1740 was passed in the Province of South Carolina, during colonial Governor William Bull's time in office, in response to the Stono Rebellion in 1739.

The comprehensive act made it illegal for enslaved Africans to move abroad, ...

was passed in

South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, during Governor

William Bull's time in office, in response to the

Stono Rebellion

The Stono Rebellion (also known as Cato's Conspiracy or Cato's Rebellion) was a slave revolt that began on 9 September 1739, in the colony of South Carolina. It was the largest slave rebellion in the Southern Colonies, with 25 colonists and 35 t ...

in 1739. The

act made it illegal for

enslaved Africans

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

to

move abroad,

assemble in groups,

raise food,

earn

Earning can refer to:

* Labour (economics)

*Earnings of a company

*Merit

Merit may refer to:

Religion

* Merit (Christianity)

* Merit (Buddhism)

* Punya (Hinduism)

* Imputed righteousness in Reformed Christianity

Companies and brands

* Merit ...

money

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are as ...

, and

learn to write (though reading was not proscribed). Additionally, owners were permitted to

kill rebellious slaves if necessary. The Act remained in effect until 1865.

Revolutionary War

Prior to the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

, the

British began taxing American colonies to raise

revenue

In accounting, revenue is the total amount of income generated by the sale of goods and services related to the primary operations of the business.

Commercial revenue may also be referred to as sales or as turnover. Some companies receive reven ...

. Residents of South Carolina were outraged by the Townsend Acts that taxed tea, paper, wine, glass, and oil. To protest the Stamp Act, South Carolina sent the wealthy rice planter

Thomas Lynch, twenty-six-year-old lawyer

John Rutledge

John Rutledge (September 17, 1739 – June 21, 1800) was an American Founding Father, politician, and jurist who served as one of the original associate justices of the Supreme Court and the second chief justice of the United States. Additiona ...

, and

Christopher Gadsden

Christopher Gadsden (February 16, 1724 – August 28, 1805) was an American politician who was the principal leader of the South Carolina Patriot movement during the American Revolution. He was a delegate to the Continental Congress, a brigadier ...

to the

Stamp Act Congress, held in 1765 in New York. Other taxes were removed, but tea taxes remained. Soon residents of South Carolina, like those of the

Boston Tea Party, began to dump tea into the Charleston Harbor, followed by

boycotts and

protests.

South Carolina set up its state government and constitution on March 26, 1776. Because of the colony's longstanding trade ties with Great Britain, the Low Country cities had numerous Loyalists. Many of the Patriot battles fought in South Carolina during the American Revolution were against

loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

Carolinians and the

Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ''Tsalagihi Ayeli'' or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ ''Tsalagiyehli''), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It ...

, which was allied with the British. This was to British General

Henry Clinton's advantage, as his strategy was to march his troops north from

St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afri ...

and sandwich

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

in the North. Clinton alienated Loyalists and enraged

Patriots by attacking and nearly

annihilating a fleeing army of Patriot soldiers who posed no threat.

White colonists were not the only ones with a desire for freedom. Estimates are that about 25,000 slaves escaped, migrated or died during the disruption of the war, 30 percent of the state's slave population. About 13,000 joined the British, who had promised them freedom if they left rebel masters and fought with them. From 1770 to 1790, the proportion of the state's population made up of blacks (almost all of whom were enslaved), dropped from 60.5 percent to 43.8 percent.

On October 7, 1780, at

Kings Mountain, John Sevier and William Campbell, using volunteers from the mountains and from Tennessee, surrounded 1000 Loyalist soldiers camped on a mountain top. It was a decisive Patriot victory. It was the first Patriot victory since the British had taken Charleston. Thomas Jefferson, governor of Virginia at the time, called it, "The turn of the tide of success."

While tensions mounted between the Crown and the Carolinas, some key southern Pastors became a target of King George: "... this church (Bullock Creek) was noted as one of the "Four Bees" in King George's bonnet due to its pastor, Rev. Joseph Alexander, preaching open rebellion to the British Crown in June 1780. Bullock Creek Presbyterian Church was a place noted for being a Whig party stronghold. Under a ground swell of such Calvin Protestant leadership, South Carolina moved from a back seat to the front in the war against tyranny. Patriots went on to regain control of

Charleston

Charleston most commonly refers to:

* Charleston, South Carolina

* Charleston, West Virginia, the state capital

* Charleston (dance)

Charleston may also refer to:

Places Australia

* Charleston, South Australia

Canada

* Charleston, Newfoundlan ...

and South Carolina with untrained militiamen by trapping Colonel

Banastre "No Quarter" Tarleton's troops along a river.

In 1787,

John Rutledge

John Rutledge (September 17, 1739 – June 21, 1800) was an American Founding Father, politician, and jurist who served as one of the original associate justices of the Supreme Court and the second chief justice of the United States. Additiona ...

,

Charles Pinckney Charles Pinckney may refer to:

* Charles Pinckney (South Carolina chief justice) (died 1758), father of Charles Cotesworth Pinckney

* Colonel Charles Pinckney (1731–1782), South Carolina politician, loyal to British during Revolutionary War, fath ...

,

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (February 25, 1746 – August 16, 1825) was an American Founding Father, statesman of South Carolina, Revolutionary War veteran, and delegate to the Constitutional Convention where he signed the United States Constit ...

, and

Pierce Butler Pierce or Piers Butler may refer to:

*Piers Butler, 8th Earl of Ormond (c. 1467 – 26 August 1539), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

*Piers Butler, 3rd Viscount Galmoye (1652–1740), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

*Pi ...

went to Philadelphia where the

Constitutional Convention Constitutional convention may refer to:

* Constitutional convention (political custom), an informal and uncodified procedural agreement

*Constitutional convention (political meeting), a meeting of delegates to adopt a new constitution or revise an e ...

was being held and constructed what served as a detailed outline for the

U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

. The federal Constitution was ratified by the state in 1787. The new state constitution was ratified in 1790 without the support of the Upcountry.

Scots Irish

During the Revolution, the Scots Irish in the back country in most states were noted as strong patriots. One exception was the Waxhaw settlement on the lower

Catawba River along the North Carolina-South Carolina boundary, where Loyalism was strong. The area had two main settlement periods of Scotch Irish. During the 1750s–1760s, second- and third-generation Scotch Irish Americans moved from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina. This particular group had large families, and as a group they produced goods for themselves and for others. They generally were patriots.

In addition to these, The Earl of Donegal arrived in Charleston on December 22, 1767, from Belfast, bringing approximately fifty families over who received land grants under the Bounty Act. Most of these families settled in the upstate. A portion of these eventually migrated into Georgia and on into Alabama.

Just prior to the Revolution, a second stream of immigrants came directly from northern Ireland via Charleston. Mostly poor, this group settled in an underdeveloped area because they could not afford expensive land. Most of this group remained loyal to the Crown or neutral when the war began. Prior to

Charles Cornwallis's march into the backcountry in 1780, two-thirds of the people within the Waxhaw settlement had declined to serve in the army. British victory at the Battle of the Waxhaws resulted in anti-British sentiment in a bitterly divided region. While many individuals chose to take up arms against the British, the British forced the people to choose sides, as they were trying to recruit Loyalists for a militia.

Loyalists

South Carolina had one of the strongest

Loyalists factions of any state, outside of states such as New York and Pennsylvania. About 5,000 took up arms against the

Patriot government during revolution, and thousands more were supporters. Nearly all had immigrated to the province after 1765, only about one in six being native-born. About 45% of the Loyalists were small farmers, 30% were merchants, artisans or shopkeepers; 15% were large farmers or plantation owners; 10% were royal officials. Geographically they were strongest in the backcountry.

Although the state had experienced a bitter bloody internal civil war from 1780–82, civilian leaders nevertheless adopted a policy of reconciliation that proved more moderate than any other state. About 4500 white Loyalists left South Carolina when the war ended, with the others staying in state. South Carolina would successfully and quickly reincorporate the remaining Loyalists who stayed behind. Some were required to pay a 10% fine of the value of the property. The legislature named 232 Loyalists liable for confiscation of their property, but most appealed and were forgiven.

Rebecca Brannon, says South Carolinians, "offered the most generous reconciliation to Loyalists ... despite suffering the worst extremes of violent civil war" According to a reviewer, she convincingly argues that South Carolinians, driven by social, political, and economic imperatives, engaged in a process of integration that was significantly more generous than that of other states. Indeed, Brannon's account strongly suggests that it was precisely the brutality and destructiveness of the conflict in the Palmetto State that led South Carolinians to favor reconciliation over retribution.

Antebellum South Carolina

South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

led opposition to national law during the

Nullification Crisis. It was the first state to declare its

secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

in 1860 in response to the

election of Abraham Lincoln. Dominated by major planters, it was the only state in which slaveholders composed a majority of the legislature.

Politics and slavery

After the Revolutionary War, numerous slaves were freed. Most of the northern states abolished slavery, sometimes combined with gradual emancipation. In the

Upper South, inspired by revolutionary ideals and activist preachers, state legislatures passed laws making it easier for slaveholders to

manumit

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

(free) their slaves both during their lifetimes or by wills. Quakers, Methodists, and Baptists urged slaveholders to free their slaves. In the period from 1790 to 1810, the proportion and number of free blacks rose dramatically in the Upper South and overall, from less than 1 percent to more than 10 percent.

When the importation of slaves became illegal in 1808, South Carolina was the only state that still allowed importation, which had been prohibited in the other states.

Slave owners had more control over the state government of South Carolina than of any other state. Elite planters played the role of English aristocrats more than did the planters of other states. In the late antebellum years, the newer Southern states, such as

Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

and

Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, allowed more political equality among whites.

Although all white male residents were allowed to vote, property requirements for office holders were higher in South Carolina than in any other state.

It was the only state legislature in which slave owners held the majority of seats.

The legislature elected the governor, all judges and state electors for federal elections, as well as the US senators into the 20th century, so its members had considerable political power.

The state's chief executive was a figurehead who had no authority to veto legislative law.

With its society disrupted by losses of enslaved Black people during the Revolution, South Carolina did not embrace

manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

as readily as states of the Upper South. Most of its small number of "free" Black people were of

mixed race, often the children of major planters or their sons, who raped the young Black enslaved females. Their wealthy fathers sometimes passed on social capital to such mixed-race children, arranging for their manumission even if officially denying them as legal heirs. Fathers sometimes arranged to have their enslaved children educated, arranged apprenticeships in skilled trades, and other preparation for independent adulthood. Some planters sent their enslaved mixed-race children to schools and colleges in the North for education.

In the early 19th century, the state legislature passed laws making

manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

more difficult. The manumission law of 1820 required slaveholders to gain legislative approval for each act of manumission and generally required other free adults to testify that the person to be freed could support himself. This meant that

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

were unable to free their enslaved children since the first law required that five citizens attest to the ability of the person proposed to be "freed" to earn a living. In 1820, the legislature ended personal manumissions, requiring all slaveholders to gain individual permission from the legislature before manumitting anyone.

The majority of the population in South Carolina was Black, with concentrations in the plantation areas of the Low Country: by 1860 the population of the state was 703,620, with 57 percent or slightly more than 402,000 classified as enslaved people. Free Black people numbered slightly less than 10,000. A concentration of

free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

lived in Charleston, where they formed an elite racial caste of people who had more skills and education than most Black people. Unlike Virginia, where most of the larger plantations and enslaved people were concentrated in the eastern part of the state, South Carolina plantations and enslaved people became common throughout much of the state. After 1794,

Eli Whitney

Eli Whitney Jr. (December 8, 1765January 8, 1825) was an American inventor, widely known for inventing the cotton gin, one of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution that shaped the economy of the Antebellum South.

Although Whitney hi ...

's

cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); a ...

allowed cotton plantations for short-staple cotton to be widely developed in the Piedmont area, which became known as the

Black Belt

Black Belt may refer to:

Martial arts

* Black belt (martial arts), an indication of attainment of expertise in martial arts

* ''Black Belt'' (magazine), a magazine covering martial arts news, technique, and notable individuals

Places

* Black B ...

of the state.

By 1830, 85% of inhabitants of rice plantations in the Low Country were enslaved people. When rice planters left the malarial low country for cities such as

Charleston

Charleston most commonly refers to:

* Charleston, South Carolina

* Charleston, West Virginia, the state capital

* Charleston (dance)

Charleston may also refer to:

Places Australia

* Charleston, South Australia

Canada

* Charleston, Newfoundlan ...

during the social season, up to 98% of the Low Country residents were enslaved people. This led to a preservation of West African customs while developing the Creole culture known as

Gullah.

[William H. Freehling, ''The Road to Disunion: Secessionists at Bay 1776–1854,'' pp. 213–228] By 1830, two-thirds of South Carolina's counties had populations with 40 percent or more enslaved people; even in the two counties with the lowest rates of slavery, 23 percent of the population were enslaved people.

In 1822, a Black freedman named

Denmark Vesey

Denmark Vesey (also Telemaque) ( July 2, 1822) was an early 19th century free Black and community leader in Charleston, South Carolina, who was accused and convicted of planning a major slave revolt in 1822. Although the alleged plot was dis ...

and compatriots around Charlestown organized a plan for thousands of enslaved people to participate in an armed uprising to gain freedom. Vesey's plan, inspired by the 1791

Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt ...

, called for thousands of armed slaves to kill their enslavers, seize the city of Charleston, and escape from the United States by sailing to

Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

. The plot was discovered when two enslaved people opposed to the plan leaked word of it to white authorities. Charleston authorities charged 131 with participating in the conspiracy. In total, the state convicted 67 and executed by hanging 35 of them, including Vesey. White fear of the insurrection of enslaved people after the Vesey conspiracy led to a 9:15 pm curfew for enslaved people in Charleston,

and the establishment of a municipal guard numbering 150 in Charleston, with half the guard stationed in an arsenal called the

Citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

. Columbia was protected by

an arsenal.

Plantations in older Southern states such as South Carolina wore out the soil to such an extent that 42% of state residents left the state for the lower South, to develop plantations with newer soil. The remaining South Carolina plantations were especially hard hit when worldwide cotton markets turned down in 1826–32 and again in 1837–49.

Nullification

The white minority in South Carolina felt more threatened than in other parts of the South, and reacted more to the economic Panic of 1819, the

Missouri Controversy of 1820, and attempts at emancipation in the form of the Ohio Resolutions of 1824 and the

American Colonization

During the Age of Discovery, a large scale European colonization of the Americas took place between about 1492 and 1800. Although the Norse had explored and colonized areas of the North Atlantic, colonizing Greenland and creating a short ter ...

Petition of 1827.

[William H. Freehling, ''The Road to Disunion: Secessionists at Bay 1776–1854,'' pp. 253–270] South Carolina's first attempt at nullification occurred in 1822, when South Carolina adopted a policy of jailing foreign Black sailors at South Carolina ports. This policy violated a treaty between the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

and the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, but South Carolina defied a complaint from Britain through American Secretary of State

John Quincy Adams and a United States Supreme Court justice's federal circuit decision condemning the jailings.

People from

Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 (Distrito Nacional)

, websi ...

had previously communicated with

Denmark Vesey

Denmark Vesey (also Telemaque) ( July 2, 1822) was an early 19th century free Black and community leader in Charleston, South Carolina, who was accused and convicted of planning a major slave revolt in 1822. Although the alleged plot was dis ...

's conspirators, and the South Carolina State Senate declared that the need to prevent insurrections was more important than laws, treaties or constitutions.

South Carolinian

George McDuffie

George McDuffie (August 10, 1790 – March 11, 1851) was the 55th Governor of South Carolina and a member of the United States Senate.

Biography