Octopus Bocki on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An octopus ( : octopuses or octopodes, see below for variants) is a soft-bodied, eight- limbed mollusc of the

The

The

The skin consists of a thin outer

The skin consists of a thin outer  The eyes of the octopus are large and at the top of the head. They are similar in structure to those of a fish, and are enclosed in a

The eyes of the octopus are large and at the top of the head. They are similar in structure to those of a fish, and are enclosed in a

Respiration involves drawing water into the mantle cavity through an aperture, passing it through the gills, and expelling it through the siphon. The ingress of water is achieved by contraction of radial muscles in the mantle wall, and flapper valves shut when strong circular muscles force the water out through the siphon. Extensive connective tissue lattices support the respiratory muscles and allow them to expand the respiratory chamber. The

Respiration involves drawing water into the mantle cavity through an aperture, passing it through the gills, and expelling it through the siphon. The ingress of water is achieved by contraction of radial muscles in the mantle wall, and flapper valves shut when strong circular muscles force the water out through the siphon. Extensive connective tissue lattices support the respiratory muscles and allow them to expand the respiratory chamber. The

Like other cephalopods, octopuses have camera-like eyes, and can distinguish the polarisation of light.

Like other cephalopods, octopuses have camera-like eyes, and can distinguish the polarisation of light.

Octopuses are

Octopuses are  About forty days after mating, the female giant Pacific octopus attaches strings of small fertilised eggs (10,000 to 70,000 in total) to rocks in a crevice or under an overhang. Here she guards and cares for them for about five months (160 days) until they hatch. In colder waters, such as those off

About forty days after mating, the female giant Pacific octopus attaches strings of small fertilised eggs (10,000 to 70,000 in total) to rocks in a crevice or under an overhang. Here she guards and cares for them for about five months (160 days) until they hatch. In colder waters, such as those off  Most young octopuses hatch as

Most young octopuses hatch as

Octopuses live in every ocean, and different species have adapted to different

Octopuses live in every ocean, and different species have adapted to different

Nearly all octopuses are predatory; bottom-dwelling octopuses eat mainly

Nearly all octopuses are predatory; bottom-dwelling octopuses eat mainly

Octopuses mainly move about by relatively slow crawling with some swimming in a head-first position.

Octopuses mainly move about by relatively slow crawling with some swimming in a head-first position.  Cirrate octopuses cannot produce jet propulsion and rely on their fins for swimming. They have neutral buoyancy and drift through the water with the fins extended. They can also contract their arms and surrounding web to make sudden moves known as "take-offs". Another form of locomotion is "pumping", which involves symmetrical contractions of muscles in their webs producing peristalsis, peristaltic waves. This moves the body slowly.

In 2005, ''Abdopus, Adopus aculeatus'' and veined octopus (''Amphioctopus marginatus'') were found to walk on two arms, while at the same time mimicking plant matter. This form of locomotion allows these octopuses to move quickly away from a potential predator without being recognised. Some species of octopus can crawl out of the water briefly, which they may do between tide pools. "Stilt walking" is used by the veined octopus when carrying stacked coconut shells. The octopus carries the shells underneath it with two arms, and progresses with an ungainly gait supported by its remaining arms held rigid.

Cirrate octopuses cannot produce jet propulsion and rely on their fins for swimming. They have neutral buoyancy and drift through the water with the fins extended. They can also contract their arms and surrounding web to make sudden moves known as "take-offs". Another form of locomotion is "pumping", which involves symmetrical contractions of muscles in their webs producing peristalsis, peristaltic waves. This moves the body slowly.

In 2005, ''Abdopus, Adopus aculeatus'' and veined octopus (''Amphioctopus marginatus'') were found to walk on two arms, while at the same time mimicking plant matter. This form of locomotion allows these octopuses to move quickly away from a potential predator without being recognised. Some species of octopus can crawl out of the water briefly, which they may do between tide pools. "Stilt walking" is used by the veined octopus when carrying stacked coconut shells. The octopus carries the shells underneath it with two arms, and progresses with an ungainly gait supported by its remaining arms held rigid.

Octopuses are highly intelligence, intelligent. Maze and problem solving, problem-solving experiments have shown evidence of a memory system that can store both short-term memory, short- and long-term memory. Young octopuses learn nothing from their parents, as adults provide no parental care beyond tending to their eggs until the young octopuses hatch.

In laboratory experiments, octopuses can readily be trained to distinguish between different shapes and patterns. They have been reported to practise observational learning, although the validity of these findings is contested. Octopuses have also been observed in what has been described as play (animal behaviour), play: repeatedly releasing bottles or toys into a circular current in their aquariums and then catching them. Octopuses often break out of their aquariums and sometimes into others in search of food. The veined octopus collects discarded coconut shells, then uses them to build a shelter, an example of tool use by animals, tool use.

Octopuses are highly intelligence, intelligent. Maze and problem solving, problem-solving experiments have shown evidence of a memory system that can store both short-term memory, short- and long-term memory. Young octopuses learn nothing from their parents, as adults provide no parental care beyond tending to their eggs until the young octopuses hatch.

In laboratory experiments, octopuses can readily be trained to distinguish between different shapes and patterns. They have been reported to practise observational learning, although the validity of these findings is contested. Octopuses have also been observed in what has been described as play (animal behaviour), play: repeatedly releasing bottles or toys into a circular current in their aquariums and then catching them. Octopuses often break out of their aquariums and sometimes into others in search of food. The veined octopus collects discarded coconut shells, then uses them to build a shelter, an example of tool use by animals, tool use.

Aside from humans, octopuses may be preyed on by fishes, seabirds, sea otters, pinnipeds, cetaceans, and other cephalopods. Octopuses typically hide or disguise themselves by camouflage and mimicry; some have conspicuous aposematism, warning coloration (aposematism) or deimatic behaviour. An octopus may spend 40% of its time hidden away in its den. When the octopus is approached, it may extend an arm to investigate. 66% of ''Enteroctopus dofleini'' in one study had scars, with 50% having amputated arms. The blue rings of the highly venomous blue-ringed octopus are hidden in muscular skin folds which contract when the animal is threatened, exposing the iridescent warning. The Atlantic white-spotted octopus (''Callistoctopus macropus'') turns bright brownish red with oval white spots all over in a high contrast display. Displays are often reinforced by stretching out the animal's arms, fins or web to make it look as big and threatening as possible.

Once they have been seen by a predator, they commonly try to escape but can also use distraction with an ink cloud ejected from the ink sac. The ink is thought to reduce the efficiency of olfactory organs, which would aid evasion from predators that employ olfaction, smell for hunting, such as sharks. Ink clouds of some species might act as Pseudomorph#Pseudomorph in other fields, pseudomorphs, or decoys that the predator attacks instead.

When under attack, some octopuses can perform arm autotomy, in a manner similar to the way skinks and other lizards detach their tails. The crawling arm may distract would-be predators. Such severed arms remain sensitive to stimuli and move away from unpleasant sensations. Octopuses can limb regeneration, replace lost limbs.

Some octopuses, such as the mimic octopus, can combine their highly flexible bodies with their colour-changing ability to mimic other, more dangerous animals, such as Pterois, lionfish, sea snakes, and eels.

Aside from humans, octopuses may be preyed on by fishes, seabirds, sea otters, pinnipeds, cetaceans, and other cephalopods. Octopuses typically hide or disguise themselves by camouflage and mimicry; some have conspicuous aposematism, warning coloration (aposematism) or deimatic behaviour. An octopus may spend 40% of its time hidden away in its den. When the octopus is approached, it may extend an arm to investigate. 66% of ''Enteroctopus dofleini'' in one study had scars, with 50% having amputated arms. The blue rings of the highly venomous blue-ringed octopus are hidden in muscular skin folds which contract when the animal is threatened, exposing the iridescent warning. The Atlantic white-spotted octopus (''Callistoctopus macropus'') turns bright brownish red with oval white spots all over in a high contrast display. Displays are often reinforced by stretching out the animal's arms, fins or web to make it look as big and threatening as possible.

Once they have been seen by a predator, they commonly try to escape but can also use distraction with an ink cloud ejected from the ink sac. The ink is thought to reduce the efficiency of olfactory organs, which would aid evasion from predators that employ olfaction, smell for hunting, such as sharks. Ink clouds of some species might act as Pseudomorph#Pseudomorph in other fields, pseudomorphs, or decoys that the predator attacks instead.

When under attack, some octopuses can perform arm autotomy, in a manner similar to the way skinks and other lizards detach their tails. The crawling arm may distract would-be predators. Such severed arms remain sensitive to stimuli and move away from unpleasant sensations. Octopuses can limb regeneration, replace lost limbs.

Some octopuses, such as the mimic octopus, can combine their highly flexible bodies with their colour-changing ability to mimic other, more dangerous animals, such as Pterois, lionfish, sea snakes, and eels.

The Cephalopoda evolved from a mollusc resembling the Monoplacophora in the Cambrian some 530 million years ago. The Coleoidea diverged from the nautiloids in the Devonian some 416 million years ago. In turn, the coleoids (including the squids and octopods) brought their shells inside the body and some 276 million years ago, during the Permian, split into the Vampyropoda and the Decabrachia. The octopuses arose from the Muensterelloidea within the Vampyropoda in the Jurassic. The earliest octopus likely lived near the sea floor (Benthic zone, benthic to Demersal zone, demersal) in shallow marine environments. Octopuses consist mostly of soft tissue, and so fossils are relatively rare. As soft-bodied cephalopods, they lack the external shell of most molluscs, including other cephalopods like the nautiloids and the extinct Ammonoidea. They have eight limbs like other Coleoidea, but lack the extra specialised feeding appendages known as tentacles which are longer and thinner with suckers only at their club-like ends. The vampire squid (''Vampyroteuthis'') also lacks tentacles but has sensory filaments.

The cladograms are based on Sanchez et al., 2018, who created a molecular phylogeny based on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA marker sequences. The position of the Eledonidae is from Ibáñez et al., 2020, with a similar methodology. Dates of divergence are from Kröger et al., 2011 and Fuchs et al, 2019.

The molecular analysis of the octopods shows that the suborder Cirrina (Cirromorphida) and the superfamily Argonautoidea are paraphyletic and are broken up; these names are shown in quotation marks and italics on the cladogram.

The Cephalopoda evolved from a mollusc resembling the Monoplacophora in the Cambrian some 530 million years ago. The Coleoidea diverged from the nautiloids in the Devonian some 416 million years ago. In turn, the coleoids (including the squids and octopods) brought their shells inside the body and some 276 million years ago, during the Permian, split into the Vampyropoda and the Decabrachia. The octopuses arose from the Muensterelloidea within the Vampyropoda in the Jurassic. The earliest octopus likely lived near the sea floor (Benthic zone, benthic to Demersal zone, demersal) in shallow marine environments. Octopuses consist mostly of soft tissue, and so fossils are relatively rare. As soft-bodied cephalopods, they lack the external shell of most molluscs, including other cephalopods like the nautiloids and the extinct Ammonoidea. They have eight limbs like other Coleoidea, but lack the extra specialised feeding appendages known as tentacles which are longer and thinner with suckers only at their club-like ends. The vampire squid (''Vampyroteuthis'') also lacks tentacles but has sensory filaments.

The cladograms are based on Sanchez et al., 2018, who created a molecular phylogeny based on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA marker sequences. The position of the Eledonidae is from Ibáñez et al., 2020, with a similar methodology. Dates of divergence are from Kröger et al., 2011 and Fuchs et al, 2019.

The molecular analysis of the octopods shows that the suborder Cirrina (Cirromorphida) and the superfamily Argonautoidea are paraphyletic and are broken up; these names are shown in quotation marks and italics on the cladogram.

Octopuses generally avoid humans, but cephalopod attack, incidents have been verified. For example, a Pacific octopus, said to be nearly perfectly camouflaged, "lunged" at a diver and "wrangled" over his camera before it let go. Another diver recorded the encounter on video. All species are venomous, but only blue-ringed octopuses have venom that is lethal to humans. Bites are reported each year across the animals' range from Australia to the eastern Indo-Pacific Ocean. They bite only when provoked or accidentally stepped upon; bites are small and usually painless. The venom appears to be able to penetrate the skin without a puncture, given prolonged contact. It contains tetrodotoxin, which causes paralysis by blocking the transmission of nerve impulses to the muscles. This causes death by respiratory failure leading to Cerebral hypoxia, cerebral anoxia. No antidote is known, but if breathing can be kept going artificially, patients recover within 24 hours. Bites have been recorded from captive octopuses of other species; they leave swellings which disappear in a day or two.

Octopuses generally avoid humans, but cephalopod attack, incidents have been verified. For example, a Pacific octopus, said to be nearly perfectly camouflaged, "lunged" at a diver and "wrangled" over his camera before it let go. Another diver recorded the encounter on video. All species are venomous, but only blue-ringed octopuses have venom that is lethal to humans. Bites are reported each year across the animals' range from Australia to the eastern Indo-Pacific Ocean. They bite only when provoked or accidentally stepped upon; bites are small and usually painless. The venom appears to be able to penetrate the skin without a puncture, given prolonged contact. It contains tetrodotoxin, which causes paralysis by blocking the transmission of nerve impulses to the muscles. This causes death by respiratory failure leading to Cerebral hypoxia, cerebral anoxia. No antidote is known, but if breathing can be kept going artificially, patients recover within 24 hours. Bites have been recorded from captive octopuses of other species; they leave swellings which disappear in a day or two.

Octopuses offer many model organism, possibilities in biological research, including their ability to regenerate limbs, change the colour of their skin, behave intelligently with a distributed nervous system, and make use of 168 kinds of protocadherins (humans have 58), the proteins that guide the connections neurons make with each other. The California two-spot octopus has had its genome sequenced, allowing exploration of its molecular adaptations. Having convergent evolution, independently evolved mammal-like intelligence, octopuses have been compared by the philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith, who has studied the nature of intelligence, to hypothetical Extraterrestrial intelligence, intelligent extraterrestrials. Their problem-solving skills, along with their mobility and lack of rigid structure enable them to escape from supposedly secure tanks in laboratories and public aquariums.

Due to their intelligence, octopuses are listed in some countries as animal testing, experimental animals on which surgery may not be performed without anesthesia, a protection usually extended only to vertebrates. In the UK from 1993 to 2012, the common octopus (''Octopus vulgaris'') was the only invertebrate protected under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. In 2012, this legislation was extended to include all cephalopods in accordance with a general European Union, EU directive.

Some robotics research is exploring biomimicry of octopus features. Octopus arms can move and sense largely autonomously without intervention from the animal's central nervous system. In 2015 a team in Italy built soft-bodied robots able to crawl and swim, requiring only minimal computation. In 2017 a German company made an arm with a soft pneumatically controlled silicone gripper fitted with two rows of suckers. It is able to grasp objects such as a metal tube, a magazine, or a ball, and to fill a glass by pouring water from a bottle.

Octopuses offer many model organism, possibilities in biological research, including their ability to regenerate limbs, change the colour of their skin, behave intelligently with a distributed nervous system, and make use of 168 kinds of protocadherins (humans have 58), the proteins that guide the connections neurons make with each other. The California two-spot octopus has had its genome sequenced, allowing exploration of its molecular adaptations. Having convergent evolution, independently evolved mammal-like intelligence, octopuses have been compared by the philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith, who has studied the nature of intelligence, to hypothetical Extraterrestrial intelligence, intelligent extraterrestrials. Their problem-solving skills, along with their mobility and lack of rigid structure enable them to escape from supposedly secure tanks in laboratories and public aquariums.

Due to their intelligence, octopuses are listed in some countries as animal testing, experimental animals on which surgery may not be performed without anesthesia, a protection usually extended only to vertebrates. In the UK from 1993 to 2012, the common octopus (''Octopus vulgaris'') was the only invertebrate protected under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. In 2012, this legislation was extended to include all cephalopods in accordance with a general European Union, EU directive.

Some robotics research is exploring biomimicry of octopus features. Octopus arms can move and sense largely autonomously without intervention from the animal's central nervous system. In 2015 a team in Italy built soft-bodied robots able to crawl and swim, requiring only minimal computation. In 2017 a German company made an arm with a soft pneumatically controlled silicone gripper fitted with two rows of suckers. It is able to grasp objects such as a metal tube, a magazine, or a ball, and to fill a glass by pouring water from a bottle.

Octopuses – Overview

at the ''Encyclopedia of Life''

Octopoda

at the Tree of Life Web Project {{Authority control Octopuses, Articles containing video clips Commercial molluscs Extant Pennsylvanian first appearances Tool-using animals

order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

Octopoda (, ). The order consists of some 300 species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of ...

and is grouped within the class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differently ...

Cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan class Cephalopoda ( Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head, ...

a with squid

True squid are molluscs with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight arms, and two tentacles in the superorder Decapodiformes, though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also called squid despite not strictly fitting ...

s, cuttlefish

Cuttlefish or cuttles are marine molluscs of the order Sepiida. They belong to the class Cephalopoda which also includes squid, octopuses, and nautiluses. Cuttlefish have a unique internal shell, the cuttlebone, which is used for control ...

, and nautiloid

Nautiloids are a group of marine cephalopods ( Mollusca) which originated in the Late Cambrian and are represented today by the living ''Nautilus'' and '' Allonautilus''. Fossil nautiloids are diverse and speciose, with over 2,500 recorded speci ...

s. Like other cephalopods, an octopus is bilaterally symmetric

Symmetry in biology refers to the symmetry observed in organisms, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria. External symmetry can be easily seen by just looking at an organism. For example, take the face of a human being which has a pla ...

with two eyes and a beak

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for eating, preening, manipulating objects, killing prey, fighting, probing for fo ...

ed mouth at the center point of the eight limbs. The soft body can radically alter its shape, enabling octopuses to squeeze through small gaps. They trail their eight appendages behind them as they swim. The siphon

A siphon (from grc, σίφων, síphōn, "pipe, tube", also spelled nonetymologically syphon) is any of a wide variety of devices that involve the flow of liquids through tubes. In a narrower sense, the word refers particularly to a tube in a ...

is used both for respiration

Respiration may refer to:

Biology

* Cellular respiration, the process in which nutrients are converted into useful energy in a cell

** Anaerobic respiration, cellular respiration without oxygen

** Maintenance respiration, the amount of cellula ...

and for locomotion

Locomotion means the act or ability of something to transport or move itself from place to place.

Locomotion may refer to:

Motion

* Motion (physics)

* Robot locomotion, of man-made devices

By environment

* Aquatic locomotion

* Flight

* Locomoti ...

, by expelling a jet of water. Octopuses have a complex nervous system and excellent sight, and are among the most intelligent and behaviourally diverse of all invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

s.

Octopuses inhabit various regions of the ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wo ...

, including coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in groups.

C ...

s, pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or w ...

waters, and the seabed

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as 'seabeds'.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

; some live in the intertidal zone

The intertidal zone, also known as the foreshore, is the area above water level at low tide and underwater at high tide (in other words, the area within the tidal range). This area can include several types of habitats with various species ...

and others at abyssal depths. Most species grow quickly, mature early, and are short-lived. In most species, the male uses a specially adapted arm to deliver a bundle of sperm directly into the female's mantle cavity, after which he becomes senescent

Senescence () or biological aging is the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics in living organisms. The word ''senescence'' can refer to either cellular senescence or to senescence of the whole organism. Organismal senescence invol ...

and dies, while the female deposits fertilised eggs in a den and cares for them until they hatch, after which she also dies. Strategies to defend themselves against predators include the expulsion of ink

Ink is a gel, sol, or solution that contains at least one colorant, such as a dye or pigment, and is used to color a surface to produce an image, text, or design. Ink is used for drawing or writing with a pen, brush, reed pen, or quill. ...

, the use of camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

and threat displays

Deimatic behaviour or startle display means any pattern of bluffing behaviour in an animal that lacks strong defences, such as suddenly displaying conspicuous eyespots, to scare off or momentarily distract a predator, thus giving the prey anima ...

, the ability to jet quickly through the water and hide, and even deceit. All octopuses are venomous

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a ...

, but only the blue-ringed octopus

Blue-ringed octopuses, comprising the genus ''Hapalochlaena'', are four highly venomous species of octopus that are found in tide pools and coral reefs in the Pacific and Indian oceans, from Japan to Australia. They can be identified by their ...

es are known to be deadly to humans.

Octopuses appear in mythology as sea monsters like the Kraken

The kraken () is a legendary sea monster of enormous size said to appear off the coasts of Norway.

Kraken, the subject of sailors' superstitions and mythos, was first described in the modern age at the turn of the 18th century, in a travel ...

of Norway and the Akkorokamui of the Ainu

Ainu or Aynu may refer to:

*Ainu people, an East Asian ethnic group of Japan and the Russian Far East

*Ainu languages, a family of languages

**Ainu language of Hokkaido

**Kuril Ainu language, extinct language of the Kuril Islands

**Sakhalin Ainu la ...

, and probably the Gorgon

A Gorgon ( /ˈɡɔːrɡən/; plural: Gorgons, Ancient Greek: Γοργών/Γοργώ ''Gorgṓn/Gorgṓ'') is a creature in Greek mythology. Gorgons occur in the earliest examples of Greek literature. While descriptions of Gorgons vary, the te ...

of ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

. A battle with an octopus appears in Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

's book '' Toilers of the Sea'', inspiring other works such as Ian Fleming's ''Octopussy

''Octopussy'' is a 1983 spy film and the thirteenth in the ''James Bond'' series produced by Eon Productions. It is the sixth to star Roger Moore as the MI6 agent James Bond. It was directed by John Glen and the screenplay was written by G ...

''. Octopuses appear in Japanese erotic art, ''shunga

is a type of Japanese language, Japanese erotic art typically executed as a kind of ukiyo-e, often in Woodcut, woodblock print format. While rare, there are also extant erotic painted handscrolls which predate ukiyo-e. Translated literally, t ...

''. They are eaten and considered a delicacy by humans in many parts of the world, especially the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on th ...

and the Asian seas.

Etymology and pluralisation

Thescientific Latin

Contemporary Latin is the form of the Literary Latin used since the end of the 19th century. Various kinds of contemporary Latin can be distinguished, including the use of New Latin words in taxonomy and in science generally, and the fuller ec ...

term ''octopus'' was derived from Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

ὀκτώπους, a compound

Compound may refer to:

Architecture and built environments

* Compound (enclosure), a cluster of buildings having a shared purpose, usually inside a fence or wall

** Compound (fortification), a version of the above fortified with defensive struct ...

form of ὀκτώ (''oktō'', "eight") and πούς (''pous'', "foot"), itself a variant form of ὀκτάπους, a word used for example by Alexander of Tralles

Alexander of Tralles ( grc-x-byzant, Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Τραλλιανός; ca. 525– ca. 605) was one of the most eminent physicians in the Byzantine Empire. His birth date may safely be put in the 6th century AD, for he mentions Aëtiu ...

(c. 525–c. 605) for the common octopus. The standard plural

The plural (sometimes list of glossing abbreviations, abbreviated pl., pl, or ), in many languages, is one of the values of the grammatical number, grammatical category of number. The plural of a noun typically denotes a quantity greater than the ...

ised form of "octopus" in English is "octopuses"; the Ancient Greek plural ὀκτώποδες, "octopodes" (), has also been used historically. The alternative plural "octopi" is considered grammatically incorrect because it wrongly assumes that ''octopus'' is a Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

second declension The second declension is a category of nouns in Latin and Greek with similar case formation. In particular, these nouns are thematic, with an original ''o'' in most of their forms. In Classical Latin, the short ''o'' of the nominative and accusativ ...

" -us" noun or adjective when, in either Greek or Latin, it is a third declension

{{No footnotes, date=February 2021

The third declension is a category of nouns in Latin and Greek with broadly similar case formation — diverse stems, but similar endings. Sanskrit also has a corresponding class (although not commonly termed ...

noun.

Historically, the first plural to commonly appear in English language sources, in the early 19th century, is the latinate form "octopi", followed by the English form "octopuses" in the latter half of the same century. The Hellenic plural is roughly contemporary in usage, although it is also the rarest.

''Fowler's Modern English Usage

''A Dictionary of Modern English Usage'' (1926), by Henry Watson Fowler (1858–1933), is a style guide to British English usage, pronunciation, and writing. Covering topics such as plurals and literary technique, distinctions among like word ...

'' states that the only acceptable plural in English is "octopuses", that "octopi" is misconceived, and "octopodes" pedantic

A pedant is a person who is excessively concerned with formalism, accuracy and precision, or one who makes an ostentatious and arrogant show of learning.

Etymology

The English language word ''pedant'' comes from the French ''pédant'' (used i ...

; the last is nonetheless used frequently enough to be acknowledged by the descriptivist

In the study of language, description or descriptive linguistics is the work of objectively analyzing and describing how language is actually used (or how it was used in the past) by a speech community. François & Ponsonnet (2013).

All acad ...

''Merriam-Webster 11th Collegiate Dictionary'' and ''Webster's New World College Dictionary''. The ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a com ...

'' lists "octopuses", "octopi", and "octopodes", in that order, reflecting frequency of use, calling "octopodes" rare and noting that "octopi" is based on a misunderstanding. The ''New Oxford American Dictionary

The ''New Oxford American Dictionary'' (''NOAD'') is a single-volume dictionary of American English compiled by American editors at the Oxford University Press.

''NOAD'' is based upon the ''New Oxford Dictionary of English'' (''NODE''), publishe ...

'' (3rd Edition, 2010) lists "octopuses" as the only acceptable pluralisation, and indicates that "octopodes" is still occasionally used, but that "octopi" is incorrect.

Anatomy and physiology

Size

giant Pacific octopus

The giant Pacific octopus (''Enteroctopus dofleini''), also known as the North Pacific giant octopus, is a large marine cephalopod belonging to the genus '' Enteroctopus''. Its spatial distribution includes the coastal North Pacific, along Mexic ...

''(Enteroctopus dofleini)'' is often cited as the largest known octopus species. Adults usually weigh around 15 kg (33 lb), with an arm span of up to 4.3 m (14 ft). The largest specimen of this species to be scientifically documented was an animal with a live mass of 71 kg (156.5 lb). Much larger sizes have been claimed for the giant Pacific octopus:Norman, M. 2000. ''Cephalopods: A World Guide''. ConchBooks, Hackenheim. p. 214. one specimen was recorded as 272 kg (600 lb) with an arm span of 9 m (30 ft). A carcass of the seven-arm octopus

The seven-arm octopus (''Haliphron atlanticus'') is one of the two largest known species of octopus; based on scientific records, it has a maximum estimated total length of and mass of . The only other similarly large extant species is the gia ...

, ''Haliphron atlanticus'', weighed 61 kg (134 lb) and was estimated to have had a live mass of 75 kg (165 lb). The smallest species is ''Octopus wolfi

''Octopus wolfi'', the star-sucker pygmy octopus, is the smallest known octopus

An octopus ( : octopuses or octopodes, see below for variants) is a soft-bodied, eight- limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (, ). The order consists of ...

'', which is around and weighs less than .

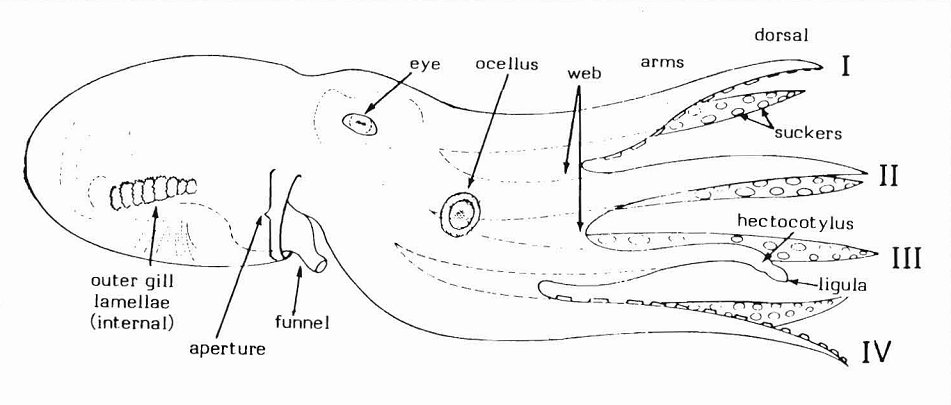

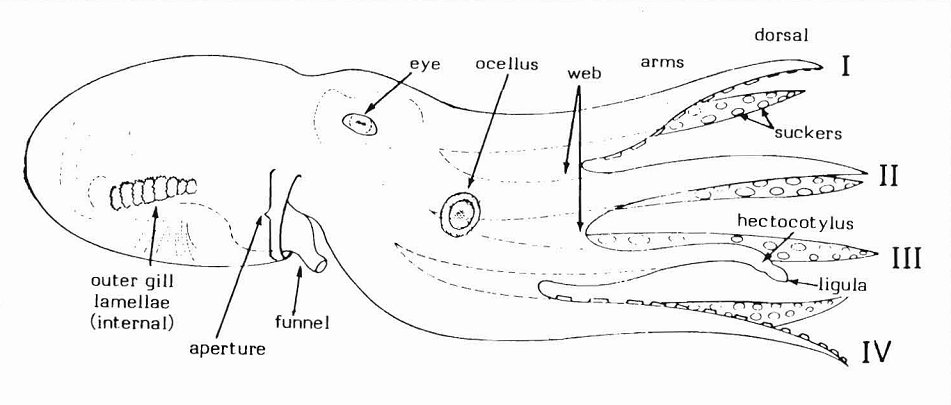

External characteristics

The octopus isbilaterally symmetrical

Symmetry in biology refers to the symmetry observed in organisms, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria. External symmetry can be easily seen by just looking at an organism. For example, take the face of a human being which has a pla ...

along its dorso-ventral (back to belly) axis; the head and foot

The foot ( : feet) is an anatomical structure found in many vertebrates. It is the terminal portion of a limb which bears weight and allows locomotion. In many animals with feet, the foot is a separate organ at the terminal part of the leg mad ...

are at one end of an elongated body and function as the anterior (front) of the animal. The head includes the mouth and brain. The foot has evolved into a set of flexible, prehensile appendages

An appendage (or outgrowth) is an external body part, or natural prolongation, that protrudes from an organism's body.

In arthropods, an appendage refers to any of the homologous body parts that may extend from a body segment, including antenn ...

, known as "arms", that surround the mouth and are attached to each other near their base by a webbed structure. The arms can be described based on side and sequence position (such as L1, R1, L2, R2) and divided into four pairs. The two rear appendages are generally used to walk on the sea floor, while the other six are used to forage for food. The bulbous and hollow mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

is fused to the back of the head and is known as the visceral hump; it contains most of the vital organs. The mantle cavity has muscular walls and contains the gills; it is connected to the exterior by a funnel or siphon

A siphon (from grc, σίφων, síphōn, "pipe, tube", also spelled nonetymologically syphon) is any of a wide variety of devices that involve the flow of liquids through tubes. In a narrower sense, the word refers particularly to a tube in a ...

. The mouth of an octopus, located underneath the arms, has a sharp hard beak

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for eating, preening, manipulating objects, killing prey, fighting, probing for fo ...

.

The skin consists of a thin outer

The skin consists of a thin outer epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and Subcutaneous tissue, hypodermis. The epidermis layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the ...

with mucous cells and sensory cells, and a connective tissue dermis consisting largely of collagen fibres and various cells allowing colour change. Most of the body is made of soft tissue allowing it to lengthen, contract, and contort itself. The octopus can squeeze through tiny gaps; even the larger species can pass through an opening close to in diameter. Lacking skeletal support, the arms work as muscular hydrostat

A muscular hydrostat is a biological structure found in animals. It is used to manipulate items (including food) or to move its host about and consists mainly of muscles with no skeletal support. It performs its hydraulic movement without fluid in ...

s and contain longitudinal, transverse and circular muscles around a central axial nerve. They can extend and contract, twist to left or right, bend at any place in any direction or be held rigid.

The interior surfaces of the arms are covered with circular, adhesive suckers. The suckers allow the octopus to anchor itself or to manipulate objects. Each sucker is usually circular and bowl-like and has two distinct parts: an outer shallow cavity called an infundibulum An infundibulum (Latin for ''funnel''; plural, ''infundibula'') is a funnel-shaped cavity or organ.

Anatomy

* Brain: the pituitary stalk, also known as the ''infundibulum'' and ''infundibular stalk'', is the connection between the hypothalamus and ...

and a central hollow cavity called an acetabulum

The acetabulum (), also called the cotyloid cavity, is a concave surface of the pelvis. The head of the femur meets with the pelvis at the acetabulum, forming the hip joint.

Structure

There are three bones of the ''os coxae'' (hip bone) tha ...

, both of which are thick muscles covered in a protective chitinous cuticle. When a sucker attaches to a surface, the orifice between the two structures is sealed. The infundibulum provides adhesion while the acetabulum remains free, and muscle contractions allow for attachment and detachment. Each of the eight arms senses and responds to light, allowing the octopus to control the limbs even if its head is obscured.

The eyes of the octopus are large and at the top of the head. They are similar in structure to those of a fish, and are enclosed in a

The eyes of the octopus are large and at the top of the head. They are similar in structure to those of a fish, and are enclosed in a cartilaginous

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints as articular cartilage, and is a structural component of many body parts including the rib cage, the neck a ...

capsule fused to the cranium. The cornea

The cornea is the transparent front part of the eye that covers the iris, pupil, and anterior chamber. Along with the anterior chamber and lens, the cornea refracts light, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the eye's total optical ...

is formed from a translucent

In the field of optics, transparency (also called pellucidity or diaphaneity) is the physical property of allowing light to pass through the material without appreciable scattering of light. On a macroscopic scale (one in which the dimensions ...

epidermal layer; the slit-shaped pupil

The pupil is a black hole located in the center of the iris of the eye that allows light to strike the retina.Cassin, B. and Solomon, S. (1990) ''Dictionary of Eye Terminology''. Gainesville, Florida: Triad Publishing Company. It appears black ...

forms a hole in the iris

Iris most often refers to:

*Iris (anatomy), part of the eye

*Iris (mythology), a Greek goddess

* ''Iris'' (plant), a genus of flowering plants

* Iris (color), an ambiguous color term

Iris or IRIS may also refer to:

Arts and media

Fictional ent ...

just behind the cornea. The lens is suspended behind the pupil; photoreceptive retinal cells cover the back of the eye. The pupil can be adjusted in size; a retinal pigment screens incident light in bright conditions.

Some species differ in form from the typical octopus body shape. Basal

Basal or basilar is a term meaning ''base'', ''bottom'', or ''minimum''.

Science

* Basal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location for features associated with the base of an organism or structure

* Basal (medicine), a minimal level that is nec ...

species, the Cirrina

Cirrina or Cirrata is a suborder and one of the two main divisions of octopuses. Cirrate octopuses have a small, internal shell and two fins on their head, while their sister suborder Incirrina has neither. The fins of cirrate octopods are ass ...

, have stout gelatinous bodies with webbing that reaches near the tip of their arms, and two large fins

A fin is a thin component or appendage attached to a larger body or structure. Fins typically function as foils that produce lift or thrust, or provide the ability to steer or stabilize motion while traveling in water, air, or other fluids. F ...

above the eyes, supported by an internal shell. Fleshy papillae or cirri

Giovanni Battista Cirri (1 October 1724 – 11 June 1808) was an Italian cellist and composer in the 18th century.

Biography

Cirri was born in Forlì in the Emilia-Romagna Region of Italy. He had his first musical training with his brother ...

are found along the bottom of the arms, and the eyes are more developed.

Circulatory system

Octopuses have a closedcirculatory system

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

, in which the blood remains inside blood vessels. Octopuses have three hearts; a systemic or main heart that circulates blood around the body and two branchial or gill hearts that pump it through each of the two gills. The systemic heart is inactive when the animal is swimming and thus it tires quickly and prefers to crawl. Octopus blood contains the copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish ...

-rich protein haemocyanin

Hemocyanins (also spelled haemocyanins and abbreviated Hc) are proteins that transport oxygen throughout the bodies of some invertebrate animals. These metalloproteins contain two copper atoms that reversibly bind a single oxygen molecule (O2) ...

to transport oxygen. This makes the blood very viscous

The viscosity of a fluid is a measure of its resistance to deformation at a given rate. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of "thickness": for example, syrup has a higher viscosity than water.

Viscosity quantifies the inte ...

and it requires considerable pressure to pump it around the body; octopuses' blood pressure

Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure of circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels. Most of this pressure results from the heart pumping blood through the circulatory system. When used without qualification, the term "blood pressur ...

s can exceed . In cold conditions with low oxygen levels, haemocyanin transports oxygen more efficiently than haemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

. The haemocyanin is dissolved in the plasma instead of being carried within blood cells, and gives the blood a bluish colour.

The systemic heart has muscular contractile walls and consists of a single ventricle and two atria, one for each side of the body. The blood vessels consist of arteries, capillaries and veins and are lined with a cellular endothelium

The endothelium is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the rest of the ve ...

which is quite unlike that of most other invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

s. The blood circulates through the aorta and capillary system, to the vena cavae, after which the blood is pumped through the gills by the branchial hearts and back to the main heart. Much of the venous system is contractile, which helps circulate the blood.

Respiration

Respiration involves drawing water into the mantle cavity through an aperture, passing it through the gills, and expelling it through the siphon. The ingress of water is achieved by contraction of radial muscles in the mantle wall, and flapper valves shut when strong circular muscles force the water out through the siphon. Extensive connective tissue lattices support the respiratory muscles and allow them to expand the respiratory chamber. The

Respiration involves drawing water into the mantle cavity through an aperture, passing it through the gills, and expelling it through the siphon. The ingress of water is achieved by contraction of radial muscles in the mantle wall, and flapper valves shut when strong circular muscles force the water out through the siphon. Extensive connective tissue lattices support the respiratory muscles and allow them to expand the respiratory chamber. The lamella

Lamella (plural lamellae) means a small plate or flake in Latin, and in English may refer to:

Biology

* Lamella (mycology), a papery rib beneath a mushroom cap

* Lamella (botany)

* Lamella (surface anatomy), a plate-like structure in an animal

* ...

structure of the gills allows for a high oxygen uptake, up to 65% in water at . Water flow over the gills correlates with locomotion, and an octopus can propel its body when it expels water out of its siphon.

The thin skin of the octopus absorbs additional oxygen. When resting, around 41% of an octopus's oxygen absorption is through the skin. This decreases to 33% when it swims, as more water flows over the gills; skin oxygen uptake also increases. When it is resting after a meal, absorption through the skin can drop to 3% of its total oxygen uptake.

Digestion and excretion

The digestive system of the octopus begins with thebuccal mass

The digestive system of gastropods has evolved to suit almost every kind of diet and feeding behavior. Gastropods (snails and slugs) as the largest taxonomic class of the mollusca are very diverse: the group includes carnivores, herbivores, scav ...

which consists of the mouth with its chitin

Chitin ( C8 H13 O5 N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is probably the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cellulose); an estimated 1 billion tons of chit ...

ous beak, the pharynx, radula

The radula (, ; plural radulae or radulas) is an anatomical structure used by molluscs for feeding, sometimes compared to a tongue. It is a minutely toothed, chitinous ribbon, which is typically used for scraping or cutting food before the food ...

and salivary glands. The radula is a spiked, muscular tongue-like organ with multiple rows of tiny teeth. Food is broken down and is forced into the oesophagus by two lateral extensions of the esophageal side walls in addition to the radula. From there it is transferred to the gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans a ...

, which is mostly suspended from the roof of the mantle cavity by numerous membranes. The tract consists of a crop

A crop is a plant that can be grown and harvested extensively for profit or subsistence. When the plants of the same kind are cultivated at one place on a large scale, it is called a crop. Most crops are cultivated in agriculture or hydropo ...

, where the food is stored; a stomach, where food is ground down; a caecum

The cecum or caecum is a pouch within the peritoneum that is considered to be the beginning of the large intestine. It is typically located on the right side of the body (the same side of the body as the appendix, to which it is joined). The w ...

where the now sludgy food is sorted into fluids and particles and which plays an important role in absorption; the digestive gland

The hepatopancreas, digestive gland or midgut gland is an organ of the digestive tract of arthropods and molluscs. It provides the functions which in mammals are provided separately by the liver and pancreas, including the production of digestive ...

, where liver cells break down and absorb the fluid and become "brown bodies"; and the intestine, where the accumulated waste is turned into faecal ropes by secretions and blown out of the funnel via the rectum.

During osmoregulation

Osmoregulation is the active regulation of the osmotic pressure of an organism's body fluids, detected by osmoreceptors, to maintain the homeostasis of the organism's water content; that is, it maintains the fluid balance and the concentration ...

, fluid is added to the pericardia of the branchial hearts. The octopus has two nephridia

The nephridium (plural ''nephridia'') is an invertebrate organ, found in pairs and performing a function similar to the vertebrate kidneys (which originated from the chordate nephridia). Nephridia remove metabolic wastes from an animal's body. Neph ...

(equivalent to vertebrate kidneys) which are associated with the branchial hearts; these and their associated ducts connect the pericardial cavities with the mantle cavity. Before reaching the branchial heart, each branch of the vena cava

In anatomy, the venae cavae (; singular: vena cava ; ) are two large veins (great vessels) that return deoxygenated blood from the body into the heart. In humans they are the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava, and both empty into the ...

expands to form renal appendages which are in direct contact with the thin-walled nephridium. The urine is first formed in the pericardial cavity, and is modified by excretion, chiefly of ammonia, and selective absorption from the renal appendages, as it is passed along the associated duct and through the nephridiopore into the mantle cavity.

Nervous system and senses

Octopuses (along withcuttlefish

Cuttlefish or cuttles are marine molluscs of the order Sepiida. They belong to the class Cephalopoda which also includes squid, octopuses, and nautiluses. Cuttlefish have a unique internal shell, the cuttlebone, which is used for control ...

) have the highest brain-to-body mass ratios of all invertebrates; this is greater than that of many vertebrates. Octopuses have the same jumping genes

A transposable element (TE, transposon, or jumping gene) is a nucleic acid sequence in DNA that can change its position within a genome, sometimes creating or reversing mutations and altering the cell's genetic identity and genome size. Transp ...

that are active in the human brain, implying an evolutionary convergence

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

at molecular level. The nervous system

In Biology, biology, the nervous system is the Complex system, highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its Behavior, actions and Sense, sensory information by transmitting action potential, signals to and from different parts of its ...

is complex, only part of which is localised in its brain, which is contained in a cartilaginous capsule. Two-thirds of an octopus's neuron

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an membrane potential#Cell excitability, electrically excitable cell (biology), cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous ...

s are in the nerve cords of its arms; these are capable of complex reflex

In biology, a reflex, or reflex action, is an involuntary, unplanned sequence or action and nearly instantaneous response to a stimulus.

Reflexes are found with varying levels of complexity in organisms with a nervous system. A reflex occurs ...

actions without input from the brain. Unlike vertebrates, the complex motor skills of octopuses are not organised in their brains via internal somatotopic map

Somatotopy is the point-for-point correspondence of an area of the body to a specific point on the central nervous system. Typically, the area of the body corresponds to a point on the primary somatosensory cortex (postcentral gyrus). This cortex i ...

s of their bodies.

Like other cephalopods, octopuses have camera-like eyes, and can distinguish the polarisation of light.

Like other cephalopods, octopuses have camera-like eyes, and can distinguish the polarisation of light. Colour vision

Color vision, a feature of visual perception, is an ability to perceive differences between light composed of different wavelengths (i.e., different spectral power distributions) independently of light intensity. Color perception is a part of t ...

appears to vary from species to species, for example being present in ''O. aegina'' but absent in ''O. vulgaris''.

Opsin

Animal opsins are G-protein-coupled receptors and a group of proteins made light-sensitive via a chromophore, typically retinal. When bound to retinal, opsins become Retinylidene proteins, but are usually still called opsins regardless. Most pro ...

s in the skin respond to different wavelengths of light and help the animals choose a coloration that camouflages them; the chromatophores in the skin can respond to light independently of the eyes.

An alternative hypothesis is that cephalopod eye

Cephalopods, as active marine predators, possess sensory organs specialized for use in aquatic conditions.Budelmann BU. "Cephalopod sense organs, nerves and the brain: Adaptations for high performance and life style." Marine and Freshwater Behavi ...

s in species which only have a single photoreceptor protein

Photoreceptor proteins are light-sensitive proteins involved in the sensing and response to light in a variety of organisms. Some examples are rhodopsin in the photoreceptor cells of the vertebrate retina, phytochrome in plants, and bacteriorh ...

may use chromatic aberration

In optics, chromatic aberration (CA), also called chromatic distortion and spherochromatism, is a failure of a lens to focus all colors to the same point. It is caused by dispersion: the refractive index of the lens elements varies with the ...

to turn monochromatic vision into colour vision, though this sacrifices image quality. This would explain pupils shaped like the letter U, the letter W, or a dumbbell

The dumbbell, a type of free weight, is a piece of equipment used in weight training. It can be used individually or in pairs, with one in each hand.

History

The forerunner of the dumbbell, halteres, were used in ancient Greece as lifting ...

, as well as explaining the need for colourful mating displays.

Attached to the brain are two organs called statocyst

The statocyst is a balance sensory receptor present in some aquatic invertebrates, including bivalves, cnidarians, ctenophorans, echinoderms, cephalopods, and crustaceans. A similar structure is also found in ''Xenoturbella''. The statocyst cons ...

s (sac-like structures containing a mineralised mass and sensitive hairs), that allow the octopus to sense the orientation of its body. They provide information on the position of the body relative to gravity and can detect angular acceleration. An autonomic response keeps the octopus's eyes oriented so that the pupil is always horizontal. Octopuses may also use the statocyst to hear sound. The common octopus can hear sounds between 400 Hz and 1000 Hz, and hears best at 600 Hz.

Octopuses have an excellent somatosensory system

In physiology, the somatosensory system is the network of neural structures in the brain and body that produce the perception of touch ( haptic perception), as well as temperature ( thermoception), body position ( proprioception), and pain. I ...

. Their suction cups are equipped with chemoreceptors

A chemoreceptor, also known as chemosensor, is a specialized sensory receptor which transduces a chemical substance (endogenous or induced) to generate a biological signal. This signal may be in the form of an action potential, if the chemorecep ...

so they can taste

The gustatory system or sense of taste is the sensory system that is partially responsible for the perception of taste (flavor). Taste is the perception produced or stimulated when a substance in the mouth reacts chemically with taste recepto ...

what they touch. Octopus arms move easily because the sensors recognise octopus skin and prevent self-attachment. Octopuses appear to have poor proprioceptive

Proprioception ( ), also referred to as kinaesthesia (or kinesthesia), is the sense of self-movement, force, and body position. It is sometimes described as the "sixth sense".

Proprioception is mediated by proprioceptors, mechanosensory neuron ...

sense and must observe the arms visually to keep track of their position.

Ink sac

Theink sac

An ink sac is an anatomical feature that is found in many cephalopod mollusks used to produce the defensive cephalopod ink. With the exception of nocturnal and very deep water cephalopods, all Coleoidea (squid, octopus and cuttlefish) which dwell ...

of an octopus is located under the digestive gland. A gland attached to the sac produces the ink

Ink is a gel, sol, or solution that contains at least one colorant, such as a dye or pigment, and is used to color a surface to produce an image, text, or design. Ink is used for drawing or writing with a pen, brush, reed pen, or quill. ...

, and the sac stores it. The sac is close enough to the funnel for the octopus to shoot out the ink with a water jet. Before it leaves the funnel, the ink passes through glands which mix it with mucus, creating a thick, dark blob which allows the animal to escape from a predator. The main pigment in the ink is melanin

Melanin (; from el, μέλας, melas, black, dark) is a broad term for a group of natural pigments found in most organisms. Eumelanin is produced through a multistage chemical process known as melanogenesis, where the oxidation of the amin ...

, which gives it its black colour. Cirrate octopuses usually lack the ink sac.

Lifecycle

Reproduction

Octopuses are

Octopuses are gonochoric

In biology, gonochorism is a sexual system where there are only two sexes and each individual organism is either male or female. The term gonochorism is usually applied in animal species, the vast majority of which are gonochoric.

Gonochorism ...

and have a single, posteriorly-located gonad which is associated with the coelom

The coelom (or celom) is the main body cavity in most animals and is positioned inside the body to surround and contain the digestive tract and other organs. In some animals, it is lined with mesothelium. In other animals, such as molluscs, it ...

. The testis

A testicle or testis (plural testes) is the male reproductive gland or gonad in all bilaterians, including humans. It is homologous to the female ovary. The functions of the testes are to produce both sperm and androgens, primarily testoster ...

in males and the ovary

The ovary is an organ in the female reproductive system that produces an ovum. When released, this travels down the fallopian tube into the uterus, where it may become fertilized by a sperm. There is an ovary () found on each side of the bod ...

in females bulges into the gonocoel and the gamete

A gamete (; , ultimately ) is a haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as sex cells. In species that produce ...

s are released here. The gonocoel is connected by the gonoduct to the mantle cavity

The mantle (also known by the Latin word pallium meaning mantle, robe or cloak, adjective pallial) is a significant part of the anatomy of molluscs: it is the dorsal body wall which covers the visceral mass and usually protrudes in the form o ...

, which it enters at the gonopore

A gonopore, sometimes called a gonadopore, is a genital pore in many invertebrates. Hexapods, including insects have a single common gonopore, except mayflies, which have a pair of gonopores. More specifically, in the unmodified female it is the ...

. An optic gland creates hormones that cause the octopus to mature and age and stimulate gamete production. The gland may be triggered by environmental conditions such as temperature, light and nutrition, which thus control the timing of reproduction and lifespan.

When octopuses reproduce, the male uses a specialised arm called a hectocotylus

A hectocotylus (plural: ''hectocotyli'') is one of the arms of male cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan class Cephalopoda ( Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusive ...

to transfer spermatophore

A spermatophore or sperm ampulla is a capsule or mass containing spermatozoa created by males of various animal species, especially salamanders and arthropods, and transferred in entirety to the female's ovipore during reproduction. Spermatophores ...

s (packets of sperm) from the terminal organ of the reproductive tract (the cephalopod "penis") into the female's mantle cavity. The hectocotylus in benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from ancient Greek, βένθος (bénthos), meaning "t ...

octopuses is usually the third right arm, which has a spoon-shaped depression and modified suckers near the tip. In most species, fertilisation occurs in the mantle cavity.

The reproduction of octopuses has been studied in only a few species. One such species is the giant Pacific octopus

The giant Pacific octopus (''Enteroctopus dofleini''), also known as the North Pacific giant octopus, is a large marine cephalopod belonging to the genus '' Enteroctopus''. Its spatial distribution includes the coastal North Pacific, along Mexic ...

, in which courtship is accompanied, especially in the male, by changes in skin texture and colour. The male may cling to the top or side of the female or position himself beside her. There is some speculation that he may first use his hectocotylus to remove any spermatophore or sperm already present in the female. He picks up a spermatophore from his spermatophoric sac with the hectocotylus, inserts it into the female's mantle cavity, and deposits it in the correct location for the species, which in the giant Pacific octopus is the opening of the oviduct. Two spermatophores are transferred in this way; these are about one metre (yard) long, and the empty ends may protrude from the female's mantle. A complex hydraulic mechanism releases the sperm from the spermatophore, and it is stored internally by the female.

About forty days after mating, the female giant Pacific octopus attaches strings of small fertilised eggs (10,000 to 70,000 in total) to rocks in a crevice or under an overhang. Here she guards and cares for them for about five months (160 days) until they hatch. In colder waters, such as those off

About forty days after mating, the female giant Pacific octopus attaches strings of small fertilised eggs (10,000 to 70,000 in total) to rocks in a crevice or under an overhang. Here she guards and cares for them for about five months (160 days) until they hatch. In colder waters, such as those off Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S ...

, it may take up to ten months for the eggs to completely develop. The female aerates them and keeps them clean; if left untended, many will die. She does not feed during this time and dies soon after. Males become senescent

Senescence () or biological aging is the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics in living organisms. The word ''senescence'' can refer to either cellular senescence or to senescence of the whole organism. Organismal senescence invol ...

and die a few weeks after mating.

The eggs have large yolks; cleavage

Cleavage may refer to:

Science

* Cleavage (crystal), in mineralogy and materials science, a process of splitting a crystal

* Cleavage (geology), the foliation perpendicular to stress as a result of ductile deformation

* Cleavage (embryo), in emb ...

(division) is superficial and a germinal disc

The blastodisc, also called the germinal disc, is the embryo-forming part on the yolk of the egg of an animal that undergoes discoidal meroblastic cleavage. Discoidal cleavage occurs in those animals with a large proportion of yolk in their eggs, ...

develops at the pole. During gastrulation

Gastrulation is the stage in the early embryonic development of most animals, during which the blastula (a single-layered hollow sphere of cells), or in mammals the blastocyst is reorganized into a multilayered structure known as the gastrula. ...

, the margins of this grow down and surround the yolk, forming a yolk sac, which eventually forms part of the gut. The dorsal side of the disc grows upward and forms the embryo, with a shell gland on its dorsal surface, gills, mantle and eyes. The arms and funnel develop as part of the foot on the ventral side of the disc. The arms later migrate upward, coming to form a ring around the funnel and mouth. The yolk is gradually absorbed as the embryo develops.

Most young octopuses hatch as

Most young octopuses hatch as paralarva

Paralarvae (singular: ''paralarva'') are young cephalopods in the planktonic stages between hatchling and subadult. This stage differs from the larval stage of animals that undergo true metamorphosis. Paralarvae have been observed only in mem ...

e and are plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a cr ...

ic for weeks to months, depending on the species and water temperature. They feed on copepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have p ...

s, arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a Segmentation (biology), segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and Arth ...

larvae and other zooplankton

Zooplankton are the animal component of the planktonic community ("zoo" comes from the Greek word for ''animal''). Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents, and consequently drift or are carried along by ...

, eventually settling on the ocean floor and developing directly into adults with no distinct metamorphoses

The ''Metamorphoses'' ( la, Metamorphōsēs, from grc, μεταμορφώσεις: "Transformations") is a Latin narrative poem from 8 CE by the Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his '' magnum opus''. The poem chronicles the history of the ...

that are present in other groups of mollusc larvae. Octopus species that produce larger eggs – including the southern blue-ringed, Caribbean reef, California two-spot, ''Eledone moschata

''Eledone moschata'', the musky octopus, is a species of octopus belonging to the family Octopodidae.

Taxonomy

The skin of the single specimen of ''Eledone microsicya'' is very similar to the skin of ''Eledone moschata'' and some authorities t ...

'' and deep sea octopuses – instead hatch as benthic animals similar to the adults.

In the argonaut

The Argonauts (; Ancient Greek: ) were a band of heroes in Greek mythology, who in the years before the Trojan War (around 1300 BC) accompanied Jason to Colchis in his quest to find the Golden Fleece. Their name comes from their ship, '' Argo'', ...

(paper nautilus), the female secretes a fine, fluted, papery shell in which the eggs are deposited and in which she also resides while floating in mid-ocean. In this she broods the young, and it also serves as a buoyancy aid allowing her to adjust her depth. The male argonaut is minute by comparison and has no shell.

Lifespan

Octopuses have a relatively short lifespan; some species live for as little as six months. TheGiant Pacific octopus

The giant Pacific octopus (''Enteroctopus dofleini''), also known as the North Pacific giant octopus, is a large marine cephalopod belonging to the genus '' Enteroctopus''. Its spatial distribution includes the coastal North Pacific, along Mexic ...

, one of the two largest species of octopus, may live for as much as five years. Octopus lifespan is limited by reproduction. For most octopuses the last stage of their life is called senescence. It is the breakdown of cellular function without repair or replacement. For males, this typically begins after mating. Senescence may last from weeks to a few months, at most. For females, it begins when they lay a clutch of eggs. Females will spend all their time aerating and protecting their eggs until they are ready to hatch. During senescence, an octopus does not feed and quickly weakens. Lesions begin to form and the octopus literally degenerates. Unable to defend themselves, octopuses often fall prey to predators. The larger Pacific striped octopus

The larger Pacific striped octopus (LPSO), or Harlequin octopus, is a species of octopus known for its intelligence and gregarious nature. The species was first documented in the 1970s and, being fairly new to scientific observation, has yet to b ...

(LPSO) is an exception, as it can reproduce repeatedly over a life of around two years.

Octopus reproductive organs mature due to the hormonal

A hormone (from the Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs by complex biological processes to regulate physiology and behavior. Hormones are required fo ...

influence of the optic gland but result in the inactivation of their digestive glands. Unable to feed, the octopus typically dies of starvation. Experimental removal of both optic glands after spawning was found to result in the cessation of broodiness

Broodiness is the action or behavioral tendency to sit on a clutch of eggs to incubate them, often requiring the non-expression of many other behaviors including feeding and drinking.Homedes Ranquini, J. y Haro-García, F. Zoogenética. 1ra. edi ...

, the resumption of feeding, increased growth, and greatly extended lifespans. It has been proposed that the naturally short lifespan may be functional to prevent rapid overpopulation.

Distribution and habitat

Octopuses live in every ocean, and different species have adapted to different

Octopuses live in every ocean, and different species have adapted to different marine habitat

Marine habitats are habitats that support marine life. Marine life depends in some way on the saltwater that is in the sea (the term ''marine'' comes from the Latin ''mare'', meaning sea or ocean). A habitat is an ecological or environmen ...

s. As juveniles, common octopuses inhabit shallow tide pool

A tide pool or rock pool is a shallow pool of seawater that forms on the rocky intertidal shore. Many of these pools exist as separate bodies of water only at low tide.

Many tide pool habitats are home to especially adaptable animals th ...

s. The Hawaiian day octopus (''Octopus cyanea

''Octopus cyanea'', also known as the big blue octopus or day octopus, is an octopus in the family Octopodidae. It occurs in both the Pacific and Indian Oceans, from Hawaii to the eastern coast of Africa.Norman, M.D. 2000. ''Cephalopods: A Wo ...

'') lives on coral reefs; argonauts

The Argonauts (; Ancient Greek: ) were a band of heroes in Greek mythology, who in the years before the Trojan War (around 1300 BC) accompanied Jason to Colchis in his quest to find the Golden Fleece. Their name comes from their ship, '' Argo ...

drift in pelagic waters. ''Abdopus aculeatus

''Abdopus aculeatus'' is a small octopus species in the order Octopoda. ''A. aculeatus'' has the common name of algae octopus due to its typical resting camouflage, which resembles a gastropod shell overgrown with algae. It is small in size with ...

'' mostly lives in near-shore seagrass

Seagrasses are the only flowering plants which grow in marine environments. There are about 60 species of fully marine seagrasses which belong to four families ( Posidoniaceae, Zosteraceae, Hydrocharitaceae and Cymodoceaceae), all in the ...

beds. Some species are adapted to the cold, ocean depths. The spoon-armed octopus (''Bathypolypus arcticus

''Bathypolypus arcticus'', the North Atlantic octopus, deep sea octopus or spoonarm octopus is a small species of demersal octopus of the North Atlantic. It is usually found at depths of where the temperature is between .

Description

''Bathyp ...