occupation of Istanbul on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The occupation of Istanbul ( tr, İstanbul'un İşgali; 12 November 1918 – 4 October 1923), the capital of the

The Ottomans estimated that the population of Istanbul in 1920 was between 800,000 and 1,200,000 inhabitants, having collected population statistics from the various religious bodies. The uncertainty in the figure reflects the uncounted population of war refugees and disagreements as to the boundaries of the city. Half or less were Muslim, the rest being largely

The Ottomans estimated that the population of Istanbul in 1920 was between 800,000 and 1,200,000 inhabitants, having collected population statistics from the various religious bodies. The uncertainty in the figure reflects the uncounted population of war refugees and disagreements as to the boundaries of the city. Half or less were Muslim, the rest being largely

The Allies began to occupy Ottoman territory soon after the

The Allies began to occupy Ottoman territory soon after the

Calthorpe's message was fully noted by the Sultan. There was an eastern tradition of presenting gifts to the authority during serious conflicts, sometimes "falling of heads". There was no higher goal than preserving the integrity of the Ottoman Institution. If Calthorpe's anger could be calmed down by foisting the blame on a few members of the

Calthorpe's message was fully noted by the Sultan. There was an eastern tradition of presenting gifts to the authority during serious conflicts, sometimes "falling of heads". There was no higher goal than preserving the integrity of the Ottoman Institution. If Calthorpe's anger could be calmed down by foisting the blame on a few members of the

Calthorpe was alarmed when he learned that the victor of Gallipoli had become the inspector general for Anatolia, and Mustafa Kemal's behavior during this period did nothing to improve matters. Calthorpe urged that Kemal be recalled. Thanks to friends and sympathizers of Mustafa Kemal's in government circles, a 'compromise' was developed whereby the power of the inspector general was curbed, at least on paper. "Inspector General" became a title that had no power to command. On 23 June 1919, Somerset Arthur Gough-Calthorpe began to understand Kemal and his role in the

Calthorpe was alarmed when he learned that the victor of Gallipoli had become the inspector general for Anatolia, and Mustafa Kemal's behavior during this period did nothing to improve matters. Calthorpe urged that Kemal be recalled. Thanks to friends and sympathizers of Mustafa Kemal's in government circles, a 'compromise' was developed whereby the power of the inspector general was curbed, at least on paper. "Inspector General" became a title that had no power to command. On 23 June 1919, Somerset Arthur Gough-Calthorpe began to understand Kemal and his role in the  Arthur Gough-Calthorpe was assigned to another position on 5 August 1919, and left Istanbul.

Arthur Gough-Calthorpe was assigned to another position on 5 August 1919, and left Istanbul.

The dissolution of the Ottoman left the Sultan as sole controller of the Empire; without parliament the Sultan stood alone with the British government. Beginning with 18 March, the Sultan followed the directives of the British

The dissolution of the Ottoman left the Sultan as sole controller of the Empire; without parliament the Sultan stood alone with the British government. Beginning with 18 March, the Sultan followed the directives of the British

The success of the Turkish National Movement against the French and Greeks was followed by their forces threatening the Allied forces at Chanak. The British decided to resist any attempt to penetrate the neutral zone of the Straits. Kemal was persuaded by the French to order his forces to avoid any incident at Chanak. Nevertheless, the Chanak Crisis nearly resulted in hostilities, these being avoided on 11 October 1922, when the Armistice of Mudanya was signed, bringing the

The success of the Turkish National Movement against the French and Greeks was followed by their forces threatening the Allied forces at Chanak. The British decided to resist any attempt to penetrate the neutral zone of the Straits. Kemal was persuaded by the French to order his forces to avoid any incident at Chanak. Nevertheless, the Chanak Crisis nearly resulted in hostilities, these being avoided on 11 October 1922, when the Armistice of Mudanya was signed, bringing the  Turkish forces of the Ankara government, commanded by Şükrü Naili Pasha (3rd Corps), entered the city with a ceremony on 6 October 1923, which has been marked as the ''Liberation Day'' of Istanbul (

Turkish forces of the Ankara government, commanded by Şükrü Naili Pasha (3rd Corps), entered the city with a ceremony on 6 October 1923, which has been marked as the ''Liberation Day'' of Istanbul (

(limited preview)

* * *

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, by British, French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, Italian, and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

forces, took place in accordance with the Armistice of Mudros

Concluded on 30 October 1918 and taking effect at noon the next day, the Armistice of Mudros ( tr, Mondros Mütarekesi) ended hostilities in the Middle Eastern theatre between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies of World War I. It was signed by ...

, which ended Ottoman participation in the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

. The first French troops entered the city on 12 November 1918, followed by British troops the next day. The Italian troops landed in Galata

Galata is the former name of the Karaköy neighbourhood in Istanbul, which is located at the northern shore of the Golden Horn. The district is connected to the historic Fatih district by several bridges that cross the Golden Horn, most notab ...

on 7 February 1919.

Allied troops occupied zones based on the existing divisions of Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

and set up an Allied military administration early in December 1918. The occupation had two stages: the initial phase in accordance with the Armistice gave way in 1920 to a more formal arrangement under the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

. Ultimately, the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conf ...

, signed on 24 July 1923, led to the end of the occupation. The last troops of the Allies departed from the city on 4 October 1923, and the first troops of the Ankara government, commanded by Şükrü Naili Pasha (3rd Corps), entered the city with a ceremony on 6 October 1923, which has been marked as the ''Liberation Day'' of Istanbul (Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

: ''İstanbul'un Kurtuluşu'') and is commemorated every year on its anniversary.

1918 saw the first time the city had changed hands since the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had beg ...

in 1453. Along with the Occupation of Smyrna, it spurred the establishment of the Turkish National Movement

The Turkish National Movement ( tr, Türk Ulusal Hareketi) encompasses the political and military activities of the Turkish revolutionaries that resulted in the creation and shaping of the modern Republic of Turkey, as a consequence of the defe ...

, leading to the Turkish War of Independence

The Turkish War of Independence "War of Liberation", also known figuratively as ''İstiklâl Harbi'' "Independence War" or ''Millî Mücadele'' "National Struggle" (19 May 1919 – 24 July 1923) was a series of military campaigns waged by th ...

.

Background

The Ottomans estimated that the population of Istanbul in 1920 was between 800,000 and 1,200,000 inhabitants, having collected population statistics from the various religious bodies. The uncertainty in the figure reflects the uncounted population of war refugees and disagreements as to the boundaries of the city. Half or less were Muslim, the rest being largely

The Ottomans estimated that the population of Istanbul in 1920 was between 800,000 and 1,200,000 inhabitants, having collected population statistics from the various religious bodies. The uncertainty in the figure reflects the uncounted population of war refugees and disagreements as to the boundaries of the city. Half or less were Muslim, the rest being largely Greek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also call ...

, Armenian Orthodox, and Jewish; there had been a substantial Western European population before the war.

Legality of the occupation

TheArmistice of Mudros

Concluded on 30 October 1918 and taking effect at noon the next day, the Armistice of Mudros ( tr, Mondros Mütarekesi) ended hostilities in the Middle Eastern theatre between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies of World War I. It was signed by ...

of 30 October 1918, which ended Ottoman involvement in World , mentions the occupation of Bosporus fort

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern ...

and Dardanelles fort. That day, Somerset Gough-Calthorpe, the British signatory, stated the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French ''entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well as ...

's position that they had no intention to dismantle the government or place it under military occupation

Military occupation, also known as belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is the effective military control by a ruling power over a territory that is outside of that power's sovereign territory.Eyāl Benveniśtî. The international law ...

by "occupying Constantinople". This verbal promise and lack of mention of the occupation of Istanbul in the armistice did not change the realities for the Ottoman Empire. Admiral Somerset Gough-Calthorpe puts the British position as "No kind of favour whatsoever to any Turk and to hold out no hope for them". The Ottoman side returned to the capital with a personal letter from Calthorpe, intended for Rauf Orbay

Hüseyin Rauf Orbay (27 July 1881 – 16 July 1964) was an Ottoman-born Turkish naval officer, statesman and diplomat of Abkhazian origin.

Biography

Hüseyin Rauf was born in Constantinople in 1881 to an Abkhazian family. As an officer in ...

, in which he promised on behalf of the British government that only British and French troops would be used in the occupation of the Straits fortifications. A small number of Ottoman troops could be allowed to stay on in the occupied areas as a symbol of sovereignty.

Military administration

The Allies began to occupy Ottoman territory soon after the

The Allies began to occupy Ottoman territory soon after the Armistice of Mudros

Concluded on 30 October 1918 and taking effect at noon the next day, the Armistice of Mudros ( tr, Mondros Mütarekesi) ended hostilities in the Middle Eastern theatre between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies of World War I. It was signed by ...

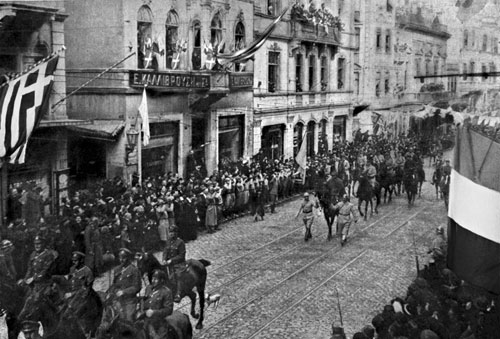

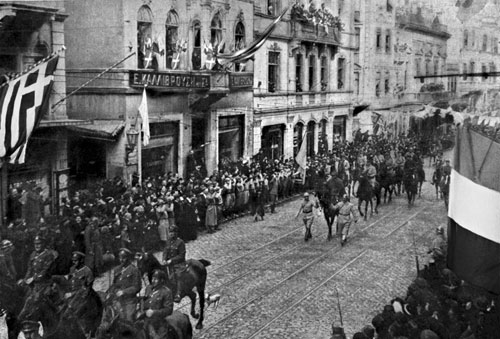

; 13 days later, a French brigade entered Istanbul, on 12 November 1918. The first British troops entered the city on the following day. Early in December 1918, Allied troops occupied sections of Istanbul and set up an Allied military administration.

On 7 February 1919, an Italian battalion with 19 officers and 740 soldiers landed at the Galata

Galata is the former name of the Karaköy neighbourhood in Istanbul, which is located at the northern shore of the Golden Horn. The district is connected to the historic Fatih district by several bridges that cross the Golden Horn, most notab ...

pier; one day later they were joined by 283 Carabinieri

The Carabinieri (, also , ; formally ''Arma dei Carabinieri'', "Arm of Carabineers"; previously ''Corpo dei Carabinieri Reali'', "Royal Carabineers Corps") are the national gendarmerie of Italy who primarily carry out domestic and foreign poli ...

, commanded by Colonel Balduino Caprini. The Carabinieri assumed police tasks.

On 10 February 1919, the commission divided the city into three zones for police matters: Stambul (the old city) was assigned to the French, Pera Pera may refer to:

Places

* Pera (Beyoğlu), a district in Istanbul formerly called Pera, now called Beyoğlu

** Galata, a neighbourhood of Beyoğlu, often referred to as Pera in the past

* Pêra (Caparica), a Portuguese locality in the district of ...

-Galata to the British and Kadıköy

Kadıköy (), known in classical antiquity and during the Roman and Byzantine eras as Chalcedon ( gr, Χαλκηδών), is a large, populous, and cosmopolitan district in the Asian side of Istanbul, Turkey, on the northern shore of the Sea of ...

and Scutari to the Italians. High Commissioner Admiral Somerset Gough-Calthorpe was assigned as the military adviser to Istanbul.

Establishing authority

The British rounded up a number of members of the old establishment and interned them in Malta, awaiting their trial for alleged crimes during World . Calthorpe included only Turkish members of the Government of Tevfik Pasha and the military/political personalities. He wanted to send a message that a military occupation was in effect and failure to comply would end with harsh punishment. His position was not shared with other partners. The French Government's response to those accused was "distinction to disadvantage of Muslim-Turks while Bulgarian, Austrian and German offenders were as yet neither arrested nor molested".Public Record Office, Foreign Office, 371/4172/28138 However, the government and the Sultan understood the message. In February 1919, Allies were informed that the Ottoman Empire was in compliance with its full apparatus to the occupation forces. Any source of conflict (including Armenian questions) would be investigated by a commission, to which neutral governments could attach two legal superintendents. Calthorpe's correspondence to Foreign Office was "The action undertaken for the arrests was very satisfactory, and has, I think, intimidated theCommittee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, translit=İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, script=Arab), later the Union and Progress Party ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى فرقهسی, translit=İttihad ve Tera ...

of Constantinople".

Ottoman courts-martial

Calthorpe's message was fully noted by the Sultan. There was an eastern tradition of presenting gifts to the authority during serious conflicts, sometimes "falling of heads". There was no higher goal than preserving the integrity of the Ottoman Institution. If Calthorpe's anger could be calmed down by foisting the blame on a few members of the

Calthorpe's message was fully noted by the Sultan. There was an eastern tradition of presenting gifts to the authority during serious conflicts, sometimes "falling of heads". There was no higher goal than preserving the integrity of the Ottoman Institution. If Calthorpe's anger could be calmed down by foisting the blame on a few members of the Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, translit=İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, script=Arab), later the Union and Progress Party ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى فرقهسی, translit=İttihad ve Tera ...

, the Ottoman Empire could thereby receive more lenient treatment at the Paris peace conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

. The trials began in Istanbul on 28 April 1919. The prosecution presented "forty-two authenticated documents substantiating the charges therein, many bearing dates, identification of senders of the cipher telegrams and letters, and names of recipients." On 22 July, the court-martial found several defendants guilty of subverting constitutionalism by force and found them responsible for massacres. During its whole existence from 28 April 1919, to 29 March 1920, Ottoman trials were performed very poorly and with increasing inefficiency, as presumed guilty people were already intended as a sacrifice to save the Empire. However, as an occupation authority, the historical rightfulness of the Allies was at stake. Calthorpe wrote to London: "proving to be a farce and injurious to our own prestige and to that of the Turkish government". The Allies considered Ottoman trials as a travesty of justice, so Ottoman justice had to be replaced with Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

* Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that i ...

justice by moving the trials to Malta as "International" trials. The "International" trials declined to use any evidence developed by the Ottoman tribunals. When the International trials were staged, Calthorpe was replaced by John de Robeck. John de Robeck said regarding the trials "that its findings cannot be held of any account at all." All of the Malta exiles were released.

A new movement

Calthorpe was alarmed when he learned that the victor of Gallipoli had become the inspector general for Anatolia, and Mustafa Kemal's behavior during this period did nothing to improve matters. Calthorpe urged that Kemal be recalled. Thanks to friends and sympathizers of Mustafa Kemal's in government circles, a 'compromise' was developed whereby the power of the inspector general was curbed, at least on paper. "Inspector General" became a title that had no power to command. On 23 June 1919, Somerset Arthur Gough-Calthorpe began to understand Kemal and his role in the

Calthorpe was alarmed when he learned that the victor of Gallipoli had become the inspector general for Anatolia, and Mustafa Kemal's behavior during this period did nothing to improve matters. Calthorpe urged that Kemal be recalled. Thanks to friends and sympathizers of Mustafa Kemal's in government circles, a 'compromise' was developed whereby the power of the inspector general was curbed, at least on paper. "Inspector General" became a title that had no power to command. On 23 June 1919, Somerset Arthur Gough-Calthorpe began to understand Kemal and his role in the establishment of the Turkish national movement

The Turkish National Movement ( tr, Türk Ulusal Hareketi) encompasses the political and military activities of the Turkish revolutionaries that resulted in the creation and shaping of the modern Republic of Turkey, as a consequence of the defe ...

. He sent a report about Mustafa Kemal to the Foreign Office. His remarks were downplayed by George Kidson of the Eastern Department. Captain Hurst (British army) in Samsun

Samsun, historically known as Sampsounta ( gr, Σαμψούντα) and Amisos (Ancient Greek: Αμισός), is a city on the north coast of Turkey and is a major Black Sea port. In 2021, Samsun recorded a population of 710,000 people. The cit ...

warned Calthorpe one more time about the Turkish national movement, but his units were replaced with a brigade of Gurkhas

The Brigade of Gurkhas is the collective name which refers to all the units in the British Army that are composed of Nepalese Gurkha soldiers. The brigade draws its heritage from Gurkha units that originally served in the British Indian Army ...

.

Arthur Gough-Calthorpe was assigned to another position on 5 August 1919, and left Istanbul.

Arthur Gough-Calthorpe was assigned to another position on 5 August 1919, and left Istanbul.

John de Robeck, August 1919–1922

In August 1919 John de Robeck replaced Somerset Arthur Gough-Calthorpe with the title of "Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, and High Commissioner at Constantinople". He was responsible for activities regarding Russia and Turkey (Ottoman Empire-Turkish national movement). John de Robeck was very worried by the defiant mood of the Ottoman parliament. When 1920 arrived, he was concerned by reports that substantial stocks of arms were reachingTurkish National Movement

The Turkish National Movement ( tr, Türk Ulusal Hareketi) encompasses the political and military activities of the Turkish revolutionaries that resulted in the creation and shaping of the modern Republic of Turkey, as a consequence of the defe ...

, some from French and Italian sources. In one of his letters to London, he asked: "Against whom would these sources be employed?"

In London, the Conference of London (February 1920)

In the Conference of London (12 February – 10 April 1920), following World War I, leaders of Britain, France, and Italy met to discuss the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire and the negotiation of agreements that would become the Treaty of Sèv ...

took place; it featured discussions about settling the treaty terms to be offered in San Remo. John de Robeck reminded participants that Anatolia was moving into a resistance stage. There were arguments of "National Pact" ( Misak-ı Milli) circulating, and if these were solidified, it would take a longer time and more resources to handle the case ( partitioning of the Ottoman Empire). He tried to persuade the leaders to take quick action and control the Sultan and pressure the rebels (from both directions). This request posed awkward problems at the highest level: promises for national sovereignty were on the table and the United States was fast withdrawing into isolation.

Treaty of Sevres

Ottoman parliament of 1920

The newly elected Ottoman parliament in Istanbul did not recognize the occupation; they developed a National Pact (Misak-ı Milli). They adopted six principles, which called for self-determination, the security of Istanbul, the opening of the Straits, and the abolition of the capitulations. While in Istanbul self-determination and protection of the Ottoman Empire were voiced, theKhilafat Movement

The Khilafat Movement (1919–24), also known as the Caliphate movement or the Indian Muslim movement, was a pan-Islamist political protest campaign launched by Muslims of British India led by Shaukat Ali, Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar, Hakim ...

in India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

tried to influence the British government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_est ...

to protect the caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, and although it was mainly a Muslim religious movement, the Khilafat struggle was becoming a part of the wider Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British rule in India. It lasted from 1857 to 1947.

The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged ...

. Both these two movements (Misak-ı Milli and the Khilafat Movement) shared a lot of notions on the ideological level, and during the Conference of London (February 1920)

In the Conference of London (12 February – 10 April 1920), following World War I, leaders of Britain, France, and Italy met to discuss the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire and the negotiation of agreements that would become the Treaty of Sèv ...

Allies concentrated on these issues.

The Ottoman Empire lost World , but Misak-ı Milli with the local Khilafat Movement was still fighting the Allies.

Solidification of the partitioning, February 1920

The plans for partitioning of the Ottoman Empire needed to be solidified. At the Conference of London on 4 March 1920, the Triple Entente decided to implement its previous (secret) agreements and form what would be theTreaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

. In doing so, all forms of resistance originating from the Ottoman Empire (rebellions, Sultan, etc.) had to be dismantled. The Allies' military forces in Istanbul ordered that the necessary actions be taken; also the political side increased efforts to put the Treaty of Sèvres into writing.

On the political side, negotiations for the Treaty of Sèvres presumed a Greek (Christian administration), a French-Armenian (Christian administration), Italian occupation region (Christian administration) and Wilsonian Armenia (Christian administration) over what was the Ottoman Empire (Muslim administration). Muslim citizens of the Ottoman Empire perceived this plan as depriving them of sovereignty. British intelligence registered the Turkish national movement as a movement of the Muslim citizens of Anatolia. The Muslim unrest all around Anatolia brought two arguments to the British government regarding the new establishments: the Muslim administration (Ottoman Empire) was not safe for Christians; the Treaty of Sèvres was the only way that Christians could be safe. Enforcing the Treaty of Sèvres could not happen without repressing Mustafa Kemal's national movement.

On the military side the British claimed that if the Allies could not control Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The r ...

at that time, they could at least control Istanbul. The plan was step by step beginning from Istanbul, dismantle every organization and slowly move deep into Anatolia. That meant facing what will be called the Turkish War of Independence

The Turkish War of Independence "War of Liberation", also known figuratively as ''İstiklâl Harbi'' "Independence War" or ''Millî Mücadele'' "National Struggle" (19 May 1919 – 24 July 1923) was a series of military campaigns waged by th ...

. The British foreign department was asked to devise a plan to ease this path, and developed the same plan that they had used during the Arab revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On ...

. This policy of breaking down authority by separating the Sultan from his government, and working different millets against each other, such as the Christian millet against the Muslim millet, was the best solution if minimal British force was to be used.

Military occupation of Istanbul

Dissolution of the parliament, March 1920

The Telegram House was occupied by Allied troops on 14 March. On the morning of 16 March, British forces, including theIndian Army

The Indian Army is the land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), who is a four ...

, began to occupy the key buildings and arrest nationalist politicians and journalists. An Indian Army operation, the Şehzadebaşı raid

The Şehzadebaşı raid was a British Indian Army operation to capture a Ottoman Army barracks in Istanbul which took place as part of a larger operation by the Allied occupational authorities to counter the Turkish National Movement. Since Allied ...

, resulted in 5 Ottoman Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun silahlı kuvvetleri) was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire.

Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the ...

soldiers from the 10th Infantry Division being killed when troops raided their barracks. On 18 March, the Ottoman parliamentarians came together in a last meeting. A black cloth covered the pulpit of the Parliament as reminder of its absent members and the Parliament sent a letter of protest to the Allies, declaring the arrest of five of its members as unacceptable.

The dissolution of the Ottoman left the Sultan as sole controller of the Empire; without parliament the Sultan stood alone with the British government. Beginning with 18 March, the Sultan followed the directives of the British

The dissolution of the Ottoman left the Sultan as sole controller of the Empire; without parliament the Sultan stood alone with the British government. Beginning with 18 March, the Sultan followed the directives of the British Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

, saying, "There would be no one left to blame for what will be coming soon"; the Sultan revealed his own version of the declaration of dissolution on 11 April, after approximately 150 Turkish politicians accused of war crimes were interned in Malta. The dissolution of the parliament was followed by the raid and closing of the journal ''Yeni Gün'' (''New Day''). ''Yeni Gün'' was owned by Yunus Nadi Abalıoğlu, an influential journalist, and was the main media organ in Turkey publishing Turkish news to global audiences.

Official declaration, 16 March 1920

On 16 March 1920, the third day of hostilities, the Allied forces declared the occupation:Enforcing the peace treaty

Early pressure on the insurgency, April–June 1920

The British argued that the insurgency of theTurkish National Movement

The Turkish National Movement ( tr, Türk Ulusal Hareketi) encompasses the political and military activities of the Turkish revolutionaries that resulted in the creation and shaping of the modern Republic of Turkey, as a consequence of the defe ...

should be suppressed by local forces in Anatolia, with the help of British training and arms. In response to a formal British request, the Istanbul government appointed an extraordinary Anatolian general inspector Süleyman Şefik Pasha and a new Security Army, Kuva-i Inzibatiye, to enforce central government control with British support. The British also supported local guerrilla groups in the Anatolian heartland (they were officially called 'independent armies') with money and arms.

Ultimately, these forces were unsuccessful in quelling the nationalist movement. A clash outside İzmit

İzmit () is a district and the central district of Kocaeli province, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental ...

quickly escalated, with British forces opening fire on the nationalists, and bombing them from the air. Although the attack forced the nationalists to retreat, the weakness of the British position had been made apparent. The British commander, General George Milne, asked for reinforcements of at least twenty-seven divisions. However, the British government was unwilling to channel these forces, as a deployment of this size could have had political consequences that were beyond the British government's capacity to handle.

Some Circassian exiles, who had emigrated to the Empire after the Circassian genocide

The Circassian genocide, or Tsitsekun, was the Russian Empire's systematic mass murder, ethnic cleansing, and expulsion of 80–97% of the Circassian population, around 800,000–1,500,000 people, during and after the Russo-Circassian War ( ...

may have supported the British—notably Ahmet Anzavur

Anzavur Ahmed Anchok Pasha (; ; 1885 – 15 April 1921) was an Ottoman soldier, gendarme officer, pasha, and militia leader of Circassian origin. He was declared a Pasha by the late Ottoman government.

Biography

Anzavur served as a major dur ...

, who led the Kuva-i Inzibatiye and ravaged the countryside. Others, such as Hüseyin Rauf Orbay, who was of Ubykh descent, remained loyal to Atatürk, and was exiled to Malta in 1920 when British forces took the city. The British were quick to accept the fact that the nationalistic movement, which had hardened during World , could not be faced without the deployment of consistent and well-trained forces. On 25 June the Kuva-i Inzibatiye was dismantled on the advice of the British, as they were becoming a liability.

Presentation of the treaty to the Sultan, June 1920

The treaty terms were presented to the Sultan in the middle of June. The treaty was harsher than anyone expected. However, because of the military pressure placed on the insurgency from April to June 1920, the Allies did not expect that there would be any serious opposition. In the meantime, however, Mustafa Kemal had set up a rival government inAnkara

Ankara ( , ; ), historically known as Ancyra and Angora, is the capital of Turkey. Located in the central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5.1 million in its urban center and over 5.7 million in Ankara Province, mak ...

, with the Grand National Assembly. On 18 October, the government of Damat Ferid Pasha was replaced by a provisional ministry under Ahmed Tevfik Pasha

Ahmet Tevfik Pasha ( ota, احمد توفیق پاشا; 11 February 1845 – 8 October 1936), later Ahmet Tevfik Okday after the Turkish Surname Law of 1934, was an Ottoman statesman of Crimean Tatar origin. He was the last Grand vizie ...

as Grand Vizier, who announced an intention to convoke the Senate with the purpose of ratification of the Treaty, provided that national unity be achieved. This required seeking cooperation with Mustafa Kemal. The latter expressed disdain to the Treaty and started a military assault. As a result, the Turkish Government issued a note to the Entente that the ratification of the Treaty was impossible at that time.

End of the occupation

The success of the Turkish National Movement against the French and Greeks was followed by their forces threatening the Allied forces at Chanak. The British decided to resist any attempt to penetrate the neutral zone of the Straits. Kemal was persuaded by the French to order his forces to avoid any incident at Chanak. Nevertheless, the Chanak Crisis nearly resulted in hostilities, these being avoided on 11 October 1922, when the Armistice of Mudanya was signed, bringing the

The success of the Turkish National Movement against the French and Greeks was followed by their forces threatening the Allied forces at Chanak. The British decided to resist any attempt to penetrate the neutral zone of the Straits. Kemal was persuaded by the French to order his forces to avoid any incident at Chanak. Nevertheless, the Chanak Crisis nearly resulted in hostilities, these being avoided on 11 October 1922, when the Armistice of Mudanya was signed, bringing the Turkish War of Independence

The Turkish War of Independence "War of Liberation", also known figuratively as ''İstiklâl Harbi'' "Independence War" or ''Millî Mücadele'' "National Struggle" (19 May 1919 – 24 July 1923) was a series of military campaigns waged by th ...

to an end. The handling of this crisis caused the collapse of David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

's Ministry on 19 October 1922.

Following the Turkish War of Independence

The Turkish War of Independence "War of Liberation", also known figuratively as ''İstiklâl Harbi'' "Independence War" or ''Millî Mücadele'' "National Struggle" (19 May 1919 – 24 July 1923) was a series of military campaigns waged by th ...

(1919–1922), the Grand National Assembly of Turkey

The Grand National Assembly of Turkey ( tr, ), usually referred to simply as the TBMM or Parliament ( tr, or ''Parlamento''), is the unicameral Turkish legislature. It is the sole body given the legislative prerogatives by the Turkish Consti ...

in Ankara

Ankara ( , ; ), historically known as Ancyra and Angora, is the capital of Turkey. Located in the central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5.1 million in its urban center and over 5.7 million in Ankara Province, mak ...

abolished the Sultanate

This article includes a list of successive Islamic state, Islamic states and History of Islam, Muslim dynasties beginning with the time of the Islamic prophet Muhammad (570–632 CE) and the early Muslim conquests that Spread of Islam, spread Isla ...

on 1 November 1922, and the last Ottoman Sultan

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı padişahları), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to its dissolution in 1922. At its he ...

, Mehmed VI, was expelled from the city. Leaving aboard the British warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed forces of a state. As well as being armed, warships are designed to withstand damage and are usually faster a ...

HMS ''Malaya'' on 17 November 1922, he went into exile and died in Sanremo, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, on 16 May 1926.

Negotiations for a new peace treaty with Turkey began at the Conference of Lausanne on 20 November 1922 and reopened after a break on 23 April 1923. This led to the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conf ...

on 24 July 1923. Under the terms of the treaty, Allied forces started evacuating Istanbul on 23 August 1923 and completed the task on 4 October 1923 – British, Italian, and French troops departing ''pari passu

''Pari passu'' is a Latin phrase that literally means "with an equal step" or "on equal footing". It is sometimes translated as "ranking equally", "hand-in-hand", "with equal force", or "moving together", and by extension, "fairly", "without pa ...

''.

Turkish forces of the Ankara government, commanded by Şükrü Naili Pasha (3rd Corps), entered the city with a ceremony on 6 October 1923, which has been marked as the ''Liberation Day'' of Istanbul (

Turkish forces of the Ankara government, commanded by Şükrü Naili Pasha (3rd Corps), entered the city with a ceremony on 6 October 1923, which has been marked as the ''Liberation Day'' of Istanbul (Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

: ''İstanbul'un Kurtuluşu'') and is commemorated every year on its anniversary. On 29 October 1923, the Grand National Assembly of Turkey declared the establishment of the Turkish Republic, with Ankara as its capital. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish field marshal, revolutionary statesman, author, and the founding father of the Rep ...

became the Republic's first President.

List of Allied High Commissioners

: * November 1918 – January 1919: Louis Franchet d'Esperey * 30 January 1919 – December 1920: Albert * 1921 – 22 October 1923: Maurice César Joseph Pellé : * November 1918 – January 1919: CountCarlo Sforza

Count Carlo Sforza (24 January 1872 – 4 September 1952) was an Italian diplomat and anti-fascist politician.

Life and career

Sforza was born at Lucca, the second son of Count Giovanni Sforza (1846-1922), an archivist and noted historian ...

* September 1920 – 22 October 1923: Marchese Eugenio Camillo Garroni

:

* November 1918 – 1919: Admiral Somerset Arthur Gough-Calthorpe, also Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

* August 1919 – 1920: Admiral John de Robeck, also Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

* 1920 – 22 October 1923: Sir Horace Rumbold (then British ambassador

The Heads of British diplomatic missions are persons appointed as senior diplomats to individual nations, or international organisations. They are usually appointed as ambassadors, except in member countries of the Commonwealth of Nations wh ...

)

:

* 1918–1921:

* 1921–1923: Charalambos Simopoulos

References

Further reading

* Ferudun Ata: The Relocation Trials in Occupied Istanbul, 2018 Manzara Verlag, Offenbach am Main, . * * * * * * * Bilge Criss, Nur (1999). "Constantinople under Allied Occupation 1918–1923", Brill,(limited preview)

* * *

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Occupation Of Istanbul 1910s in Istanbul 1920s in Istanbul Constantinople Military occupation Military history of Istanbul 1918 in the Ottoman Empire 1919 in the Ottoman Empire 1920 in the Ottoman Empire 1921 in the Ottoman Empire 1922 in the Ottoman Empire 1923 in Turkey British military occupations French military occupations 1923 in the Ottoman Empire Turkish War of Independence