November Criminals on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The stab-in-the-back myth (, , ) was an

The stab-in-the-back myth (, , ) was an

A version of the stab-in-the-back myth was publicized in 1922 by the anti-Semitic Nazi theorist

A version of the stab-in-the-back myth was publicized in 1922 by the anti-Semitic Nazi theorist

The Allied policy of

The Allied policy of

Antisemitism

on the

Die Judischen Gefallenen

A Roll of Honor Commemorating the 12,000 German Jews Who Died for their Fatherland in World War I.

{{Nationalism Antisemitic canards German nationalism German Revolution of 1918–1919 Military history of Germany during World War II Propaganda legends Weimar Republic Historiography of World War I Historical negationism Right-wing antisemitism Victimology Conspiracy theories involving Jews Antisemitism in Germany Aftermath of World War I

The stab-in-the-back myth (, , ) was an

The stab-in-the-back myth (, , ) was an antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

conspiracy theory that was widely believed and promulgated in Germany after 1918. It maintained that the Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (german: Deutsches Heer), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the l ...

did not lose World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

on the battlefield, but was instead betrayed by certain citizens on the home front

Home front is an English language term with analogues in other languages. It is commonly used to describe the full participation of the British public in World War I who suffered Zeppelin#During World War I, Zeppelin raids and endured Rationin ...

—especially Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, revolutionary socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

who fomented strikes and labor unrest, and other republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

politicians who had overthrown the House of Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, Prince-elector, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzol ...

in the German Revolution of 1918–1919

The German Revolution or November Revolution (german: Novemberrevolution) was a civil conflict in the German Empire at the end of the First World War that resulted in the replacement of the German federal constitutional monarchy with a dem ...

. Advocates of the myth denounced the German government leaders who had signed the Armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

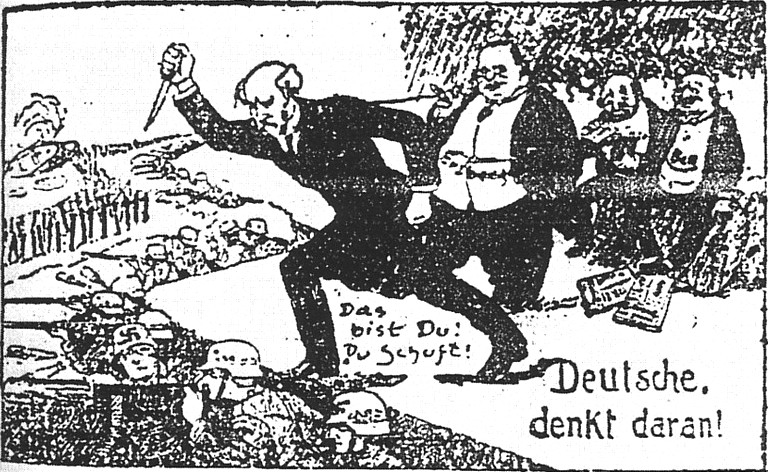

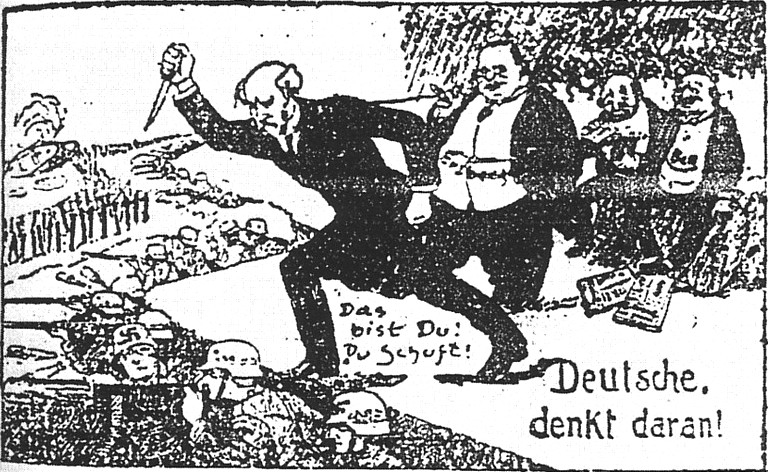

as the "November criminals" (german: Novemberverbrecher, label=none).

When Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

and the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

rose to power in 1933, they made the conspiracy theory an integral part of their official history of the 1920s, portraying the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

as the work of the "November criminals" who had "stabbed the nation in the back" in order to seize power. Nazi propaganda

The propaganda used by the German Nazi Party in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler's dictatorship of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 to 1945 was a crucial instrument for acquiring and maintaining power, and for the implementation o ...

depicted Weimar Germany as "a morass of corruption, degeneracy, national humiliation, ruthless persecution of the honest 'national opposition'—fourteen years of rule by Jews, Marxists

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectic ...

, and 'cultural Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

', who had at last been swept away by the National Socialist movement under Hitler and the victory of the 'national revolution' of 1933".

Historians inside and outside of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

unanimously reject the myth, pointing out that the Imperial German Army was out of reserves, was being overwhelmed by the entrance of the United States into the war, and had already lost the war militarily by late 1918.

Background

In the later part ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Germany was essentially transformed into a military dictatorship

A military dictatorship is a dictatorship in which the military exerts complete or substantial control over political authority, and the dictator is often a high-ranked military officer.

The reverse situation is to have civilian control of the m ...

, with the Supreme High Command (german: Oberste Heeresleitung

The ''Oberste Heeresleitung'' (, Supreme Army Command or OHL) was the highest echelon of command of the army (''Heer'') of the German Empire. In the latter part of World War I, the Third OHL assumed dictatorial powers and became the ''de facto'' ...

) and General Field Marshal

''Generalfeldmarschall'' (from Old High German ''marahscalc'', "marshal, stable master, groom"; en, general field marshal, field marshal general, or field marshal; ; often abbreviated to ''Feldmarschall'') was a rank in the armies of several ...

Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fro ...

as commander-in-chief advising Emperor Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Empi ...

– although Hindenburg was largely a figurehead, with his Chief-of-Staff, First Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German general, politician and military theorist. He achieved fame during World War I for his central role in the German victories at Liège and Tannenberg in 1914. ...

, effectively in control of the state and the army. Following the passage of the Reichstag Peace Resolution The Reichstag Peace Resolution was passed by the '' Reichstag'' of the German Empire on 19 July 1917 by 212 votes to 126. It was supported by the Social Democrats, the Catholic Centre Party and the Progressive People's Party, and was opposed by th ...

, the Army pressured the Emperor to remove Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg

Theobald Theodor Friedrich Alfred von Bethmann Hollweg (29 November 1856 – 1 January 1921) was a German politician who was the chancellor of the German Empire from 1909 to 1917. He oversaw the German entry into World War I. According to biog ...

and replace him with weak and relatively unknown figures (Georg Michaelis

Georg Michaelis (8 September 1857 – 24 July 1936) was the chancellor of the German Empire for a few months in 1917. He was the first (and the only one of the German Empire) chancellor not of noble birth to hold the office. With an economic ba ...

and Georg von Hertling

Georg Friedrich Karl Freiherr von Hertling, from 1914 Count von Hertling, (31 August 1843 – 4 January 1919) was a German politician of the Catholic Centre Party. He was foreign minister and minister president of Bavaria, then chancellor of t ...

) who were ''de facto'' puppets of Ludendorff.

The Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

had been amply resupplied by the United States, which also had fresh armies ready for combat, but the United Kingdom and France were too war-weary to contemplate an invasion of Germany with its unknown consequences.Simonds, Frank Herbert (1919) ''History of the World War, Volume 2'', New York: Doubleday. p.85 On the Western Front, although the Hindenburg Line

The Hindenburg Line (German: , Siegfried Position) was a German defensive position built during the winter of 1916–1917 on the Western Front during the First World War. The line ran from Arras to Laffaux, near Soissons on the Aisne. In 191 ...

had been penetrated and German forces were in retreat, the Allied army had not reached the western German frontier, and on the Eastern Front, Germany had already won the war against Russia, concluded with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace, separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russian SFSR, Russia and the Central Powers (German Empire, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Kingdom of ...

. In the West, Germany had successes with the Spring Offensive of 1918 but the attack had run out of momentum, the Allies had regrouped and in the Hundred Days Offensive

The Hundred Days Offensive (8 August to 11 November 1918) was a series of massive Allies of World War I, Allied offensives that ended the First World War. Beginning with the Battle of Amiens (1918), Battle of Amiens (8–12 August) on the Wester ...

retaken lost ground with no sign of stopping. Contributing to the ''Dolchstoßlegende'', the overall failure of the German offensive was blamed on strikes in the arms industry at a critical moment, leaving soldiers without an adequate supply of materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the specifi ...

. The strikes were seen as having been instigated by treasonous elements, with the Jews taking most of the blame.

The weakness of Germany's strategic position was exacerbated by the rapid collapse of the other Central Powers in late 1918, following Allied victories on the Macedonian and Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

fronts. Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

was the first to sign an armistice on 29 September 1918, at Salonica

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

. On 30 October the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

capitulated at Mudros

Moudros ( el, Μούδρος) is a town and a former municipality on the island of Lemnos, North Aegean, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Lemnos, of which it is a municipal unit. It covers the entire eas ...

. On 3 November Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

sent a flag of truce

White flags have had different meanings throughout history and depending on the locale.

Contemporary use

The white flag is an internationally recognized protective sign of truce or ceasefire, and for negotiation. It is also used to symbolize ...

to ask for an armistice. The terms, arranged by telegraph with the Allied Authorities in Paris, were communicated to the Austrian commander and accepted. The Armistice with Austria-Hungary was signed in the Villa Giusti, near Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

, on 3 November. Austria and Hungary signed separate treaties following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

After the last German offensive on the Western Front failed in 1918, Hindenburg and Ludendorff admitted that the war effort was doomed, and they pressed Kaiser Wilhelm II for an armistice to be negotiated, and for a rapid change to a civilian government in Germany. They began to take steps to deflect the blame for losing the war from themselves and the German Army to others. Ludendorff said to his staff on 1 October:

I have asked His Excellency to now bring those circles to power which we have to thank for coming so far. We will therefore now bring those gentlemen into the ministries. They can now make the peace which has to be made. They can eat the broth which they have prepared for us!Nebelin, Manfred (2011) ''Ludendorff: Diktator im Ersten Weltkrieg''. Munich: Siedler Verlag—Verlagsgruppe.In this way, Ludendorff was setting up the republican politicians – many of them Socialists – who would be brought into the government, and would become the parties that negotiated the Armistice with the Allies, as the scapegoats to take the blame for losing the war, instead of himself and Hindenburg. Normally, during wartime an armistice is negotiated between the military commanders of the hostile forces, but Hindenburg and Ludendorff had instead handed this task to the new civilian government. The attitude of the military was " e parties of the left have to take on the odium of this peace. The storm of anger will then turn against them," after which the military could step in again to ensure that things would once again be run "in the old way". On 5 October, the

German Chancellor

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ger ...

, Prince Maximilian of Baden

Maximilian, Margrave of Baden (''Maximilian Alexander Friedrich Wilhelm''; 10 July 1867 – 6 November 1929),Almanach de Gotha. ''Haus Baden (Maison de Bade)''. Justus Perthes (publishing company), Justus Perthes, Gotha, 1944, p. 18, (French). a ...

, contacted American President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, indicating that Germany was willing to accept his Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

as a basis for discussions. Wilson's response insisted that Germany institute parliamentary democracy, give up the territory it had gained to that point in the war, and significantly disarm, including giving up the German High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

. On 26 October, Ludendorff was dismissed from his post by the Emperor and replaced by Lieutenant General Wilhelm Groener

Karl Eduard Wilhelm Groener (; 22 November 1867 – 3 May 1939) was a German general and politician. His organisational and logistical abilities resulted in a successful military career before and during World War I.

After a confrontation wi ...

, who started to prepare the withdrawal and demobilisation of the army.

On 11 November 1918, the representatives of the newly formed Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

– created after the Revolution of 1918–1919 forced the abdication of the Kaiser – signed the armistice that ended hostilities. The military commanders had arranged it so that they would not be blamed for suing for peace, but the republican politicians associated with the armistice would: the signature on the armistice document was of Matthias Erzberger

Matthias Erzberger (20 September 1875 – 26 August 1921) was a German writer and politician (Centre Party), the minister of Finance from 1919 to 1920.

Prominent in the Catholic Centre Party, he spoke out against World War I from 1917 and as a ...

, who was later murdered for his alleged treason.

Given that the heavily censored German press had carried nothing but news of victories throughout the war, and that Germany itself was unoccupied while occupying a great deal of foreign territory, it was no wonder that the German public was mystified by the request for an armistice, especially as they did not know that their military leaders had asked for it, nor did they know that the German Army had been in full retreat after their last offensive had failed.

Thus the conditions were set for the "stab-in-the-back myth", in which Hindenburg and Ludendorff were held to be blameless, the German Army was seen as undefeated on the battlefield, and the republican politicians – especially the Socialists – were accused of betraying Germany. Further blame was laid at their feet after they signed the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

in 1919, which led to territorial losses and serious financial pain for the shaky new republic, including a crippling schedule of reparation payments.

Conservatives, nationalists and ex-military leaders began to speak critically about the peace and Weimar politicians, socialists, communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a so ...

and German Jews. Even Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

were viewed with suspicion by some due to supposed fealty to the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

and their presumed lack of national loyalty and patriotism. It was claimed that these groups had not sufficiently supported the war and had played a role in selling out Germany to its enemies. These ''November Criminals'', or those who seemed to benefit from the newly formed Weimar Republic, were seen to have "stabbed them in the back" on the home front, by either criticizing German nationalism

German nationalism () is an ideological notion that promotes the unity of Germans and German-speakers into one unified nation state. German nationalism also emphasizes and takes pride in the patriotism and national identity of Germans as one na ...

, instigating unrest and mounting strikes in the critical military industries or, by profiteering. These actions were believed to have deprived Germany of almost certain victory at the eleventh hour.

Origins of the myth

According to historianRichard Steigmann-Gall

Richard Steigmann-Gall (Born October 3, 1965) is an Associate Professor of History at Kent State University, and the former Director of the Jewish Studies Program from 2004 to 2010.

Education

He received his BA in history in 1989 and MA ...

, the stab-in-the-back concept can be traced back to a sermon preached on 3 February 1918, by Protestant Court Chaplain Bruno Doehring

Bruno Doehring (February 3, 1879 – April 16, 1961) was a German Lutheran pastor and theologian. A preacher at the Berlin Cathedral from 1914 to 1960, Doehring was a popular figure in the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union in Berlin. He ...

, nine months before the war had even ended. German scholar Boris Barth, in contrast to Steigmann-Gall, implies that Doehring did not actually use the term, but spoke only of 'betrayal'. Barth says Doehring was an army chaplain, not a court chaplain. The following references to Barth are on pages 148 (Müller-Meiningen), and 324 (NZZ article, with a discussion of the Ludendorff-Malcolm conversation). Barth traces the first documented use to a centrist political meeting in the Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

Löwenbräu-Keller on November 2, 1918, in which Ernst Müller-Meiningen, a member of the Progressive People's Party in the '' Reichstag'', used the term to exhort his listeners to keep fighting:

As long as the front holds, we damned well have the duty to hold out in the homeland. We would have to be ashamed of ourselves in front of our children and grandchildren if we attacked the battle front from the rear and gave it a dagger-stab. (''wenn wir der Front in den Rücken fielen und ihr den Dolchstoß versetzten.)''However, the widespread dissemination and acceptance of the "stab-in-the-back" myth came about through its use by Germany's highest military echelon. In Spring 1919,

Max Bauer

Colonel Max Hermann Bauer (31 January 1869 – 6 May 1929) was a German General Staff officer and artillery expert in the First World War. As a protege of Erich Ludendorff he was placed in charge of the German Army's munition supply by the la ...

– an Army colonel who had been the primary advisor to Ludendorff on politics and economics – published ''Could We Have Avoided, Won, or Broken Off the War?'', in which he wrote that "he war

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

was lost only and exclusively through the failure of the homeland." The birth of the specific term "stab-in-the-back" itself can possibly be dated to the autumn of 1919, when Ludendorff was dining with the head of the British Military Mission in Berlin, British general Sir Neill Malcolm

Major-General Sir Neill Malcolm, KCB, DSO (8 October 1869 – 21 December 1953) was a British Army officer who served as Chief of Staff to Fifth Army in the First World War and later commanded the Troops in the Straits Settlements.

Military ...

. Malcolm asked Ludendorff why he thought Germany lost the war. Ludendorff replied with his list of excuses, including that the home front failed the army.

Malcolm asked him: "Do you mean, General, that you were stabbed in the back?" Ludendorff's eyes lit up and he leapt upon the phrase like a dog on a bone. "Stabbed in the back?" he repeated. "Yes, that's it, exactly, we were stabbed in the back". And thus was born a legend which has never entirely perished.The phrase was to Ludendorff's liking, and he let it be known among the general staff that this was the "official" version, which led to it being spread throughout German society. It was picked up by right-wing political factions, and was even used by Kaiser Wilhelm II in the memoirs he wrote in the 1920s. Right-wing groups used it as a form of attack against the early Weimar Republic government, led by the

Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

For ...

(SPD), which had come to power with the abdication of the Kaiser. However, even the SPD had a part in furthering the myth when ''Reichspräsident'' Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (; 4 February 187128 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first President of Germany (1919–1945), president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Eber ...

, the party leader, told troops returning to Berlin on 10 November 1918 that "No enemy has vanquished you," (''kein Feind hat euch überwunden!'') and "they returned undefeated from the battlefield" (''sie sind vom Schlachtfeld unbesiegt zurückgekehrt''). The latter quote was shortened to ''im Felde unbesiegt'' ("undefeated on the battlefield") as a semi-official slogan of the ''Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshaped ...

''. Ebert had meant these sayings as a tribute to the German soldier, but it only contributed to the prevailing feeling.

Further "proof" of the myth's validity was found in British General Frederick Barton Maurice

Major-General Sir Frederick Barton Maurice, (19 January 1871 – 19 May 1951) was a British Army officer, military correspondent, writer and academic. During the First World War he was forced to retire from the army in May 1918 after writing a ...

's book ''The Last Four Months'', published in 1919. German reviews of the book misrepresented it as proving that the German army had been betrayed on the home front by being "dagger-stabbed from behind by the civilian populace" (''von der Zivilbevölkerung von hinten erdolcht''), an interpretation that Maurice disavowed in the German press, to no effect. According to William L. Shirer

William Lawrence Shirer (; February 23, 1904 – December 28, 1993) was an American journalist and war correspondent. He wrote ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich'', a history of Nazi Germany that has been read by many and cited in scholarly w ...

, Ludendorff used the reviews of the book to convince Hindenburg about the validity of the myth. Shirer, William L., ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich

''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany'' is a book by American journalist William L. Shirer in which the author chronicles the rise and fall of Nazi Germany from the birth of Adolf Hitler in 1889 to the end of World Wa ...

'', Simon and Schuster (1960) p.31fn

On 18 November 1919, Ludendorff and Hindenburg appeared before the ''Untersuchungsausschuß für Schuldfragen'' ("Committee of Inquiry into Guilt") of the newly elected Weimar National Assembly

The Weimar National Assembly (German: ), officially the German National Constitutional Assembly (), was the popularly elected constitutional convention and de facto parliament of Germany from 6 February 1919 to 21 May 1920. As part of its ...

, which was investigating the causes of the World War and Germany's defeat. The two generals appeared in civilian clothing, explaining publicly that to wear their uniforms would show too much respect to the commission. Hindenburg refused to answer questions from the chairman, and instead read a statement that had been written by Ludendorff. In his testimony he cited what Maurice was purported to have written, which provided his testimony's most memorable part. Hindenburg declared at the end of his – or Ludendorff's – speech: "As an English general has very truly said, the German Army was 'stabbed in the back'".

Furthering, the specifics of what the stab-in-the-back myth are mentioned briefly by Kaiser Wilhelm II in his memoir:I immediately summoned Field Marshal von Hindenburg and the Quartermaster General, General Gröner. General Gröner again announced that the army could fight no longer and wished rest above all else, and that, therefore, any sort of armistice must be unconditionally accepted; that the armistice must be concluded as soon as possible, since the army had supplies for only six to eight days more and was cut off from all further supplies by the rebels, who had occupied all the supply storehouses and Rhine bridges; that, for some unexplained reason, the armistice commission sent to France–consisting of Erzberger, Ambassador Count Oberndorff, and General von Winterfeldt–which had crossed the French lines two evenings before, had sent no report as to the nature of the conditions.Paul von Hindenburg, Chief of the Great General Staff at the time of the Ludendorff Offensive, also mentioned this event in a statement explaining the Kaiser’s abdication:

The conclusion of the armistice was directly impending. At moment of the highest military tension revolution broke out in Germany, the insurgents seized the Rhine bridges, important arsenals, and traffic centres in the rear of the army, thereby endangering the supply of ammunition and provisions, while the supplies in the hands of the troops were only enough to last for a few days. The troops on the lines of communication and the reserves disbanded themselves, and unfavourable reports arrived concerning the reliability of the field army proper.It was particularly this testimony of Hindenburg that led to the widespread acceptance of the ''Dolchstoßlegende'' in post-World War I Germany.

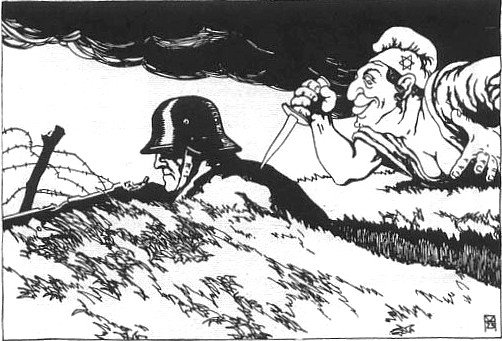

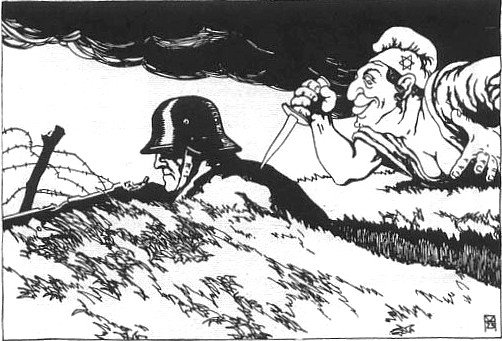

Antisemitic aspects

Theantisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

instincts of the German Army were revealed well before the stab-in-the-back myth became the military's excuse for losing the war. In October 1916, in the middle of the war, the army ordered a Jewish census of the troops, with the intent to show that Jews were under-represented in the ''Heer'' (army), and that they were over represented in non-fighting positions. Instead, the census showed just the opposite, that Jews were over-represented both in the army as a whole and in fighting positions at the front. The Imperial German Army then suppressed the results of the census.

Charges of a Jewish conspiratorial element in Germany's defeat drew heavily upon figures such as Kurt Eisner

Kurt Eisner (; 14 May 1867 21 February 1919)"Kurt Eisner – Encyclopædia Britannica" (biography), ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 2006, Britannica.com webpageBritannica-KurtEisner. was a German politician, revolutionary, journalist, and theatre c ...

, a Berlin-born German Jew who lived in Munich. He had written about the illegal nature of the war from 1916 onward, and he also had a large hand in the Munich revolution until he was assassinated in February 1919. The Weimar Republic under Friedrich Ebert violently suppressed workers' uprisings with the help of Gustav Noske

Gustav Noske (9 July 1868 – 30 November 1946) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). He served as the first Minister of Defence (''Reichswehrminister'') of the Weimar Republic between 1919 and 1920. Noske has been a cont ...

and Reichswehr General Groener, and tolerated the paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

Freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, regar ...

forming all across Germany. In spite of such tolerance, the Republic's legitimacy was constantly attacked with claims such as the stab-in-the-back. Many of its representatives such as Matthias Erzberger

Matthias Erzberger (20 September 1875 – 26 August 1921) was a German writer and politician (Centre Party), the minister of Finance from 1919 to 1920.

Prominent in the Catholic Centre Party, he spoke out against World War I from 1917 and as a ...

and Walther Rathenau

Walther Rathenau (29 September 1867 – 24 June 1922) was a German industrialist, writer and liberal politician.

During the First World War of 1914–1918 he was involved in the organization of the German war economy. After the war, Rathenau s ...

were assassinated, and the leaders were branded as "criminals" and Jews by the right-wing press dominated by Alfred Hugenberg

Alfred Ernst Christian Alexander Hugenberg (19 June 1865 – 12 March 1951) was an influential German businessman and politician. An important figure in nationalist politics in Germany for the first few decades of the twentieth century, Hugenbe ...

.

Anti-Jewish sentiment was intensified by the Bavarian Soviet Republic

The Bavarian Soviet Republic, or Munich Soviet Republic (german: Räterepublik Baiern, Münchner Räterepublik),Hollander, Neil (2013) ''Elusive Dove: The Search for Peace During World War I''. McFarland. p.283, note 269. was a short-lived unre ...

(6 April – 3 May 1919), a communist government

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Cominte ...

which briefly ruled the city of Munich before being crushed by the Freikorps. Many of the Bavarian Soviet Republic's leaders were Jewish, allowing antisemitic propagandists to connect Jews with Communism, and thus treason.

In 1919, '' Deutschvölkischer Schutz und Trutzbund'' ("German Nationalist Protection and Defiance Federation") leader Alfred Roth, writing under the pseudonym "Otto Arnim", published the book ''The Jew in the Army'' which he said was based on evidence gathered during his participation on the '' Judenzählung'', a military census which had in fact shown that German Jews had served in the front lines proportionately to their numbers. Roth's work claimed that most Jews involved in the war were only taking part as profiteers and spies, while he also blamed Jewish officers for fostering a defeatist mentality which impacted negatively on their soldiers. As such, the book offered one of the earliest published versions of the stab-in-the-back legend.

A version of the stab-in-the-back myth was publicized in 1922 by the anti-Semitic Nazi theorist

A version of the stab-in-the-back myth was publicized in 1922 by the anti-Semitic Nazi theorist Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head of ...

in his primary contribution to Nazi theory on Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a Nationalism, nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is ...

, ''Der Staatsfeindliche Zionismus'' ("Zionism, the Enemy of the State"). Rosenberg accused German Zionists of working for a German defeat and supporting Britain and the implementation of the Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

.

Aftermath

The ''Dolchstoß'' was a central image in propaganda produced by the many right-wing and traditionally conservative political parties that sprang up in the early days of the Weimar Republic, including Hitler'sNazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

. For Hitler himself, this explanatory model for World War I was of crucial personal importance. He had learned of Germany's defeat while being treated for temporary blindness following a gas attack on the front. In ''Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germ ...

'', he described a vision at this time which drove him to enter politics. Throughout his career, he railed against the "November criminals" of 1918, who had stabbed the German Army in the back.

The German historian Friedrich Meinecke

Friedrich Meinecke (October 20, 1862 – February 6, 1954) was a German historian, with national liberal and anti-Semitic views, who supported the Nazi invasion of Poland. After World War II, as a representative of an older tradition, he criti ...

attempted to trace the roots of the expression "stab-in-the-back" in a 11 June 1922 article in the Viennese newspaper ''Neue Freie Presse

''Neue Freie Presse'' ("New Free Press") was a Viennese newspaper founded by Adolf Werthner together with the journalists Max Friedländer and Michael Etienne on 1 September 1864 after the staff had split from the newspaper ''Die Presse''. It ex ...

''. In the 1924 national election, the Munich cultural journal '' Süddeutsche Monatshefte'' published a series of articles blaming the SPD and trade unions for Germany's defeat in World War I, which came out during the trial of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

and Ludendorff for high treason following the Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch,Dan Moorhouse, ed schoolshistory.org.uk, accessed 2008-05-31.Known in German as the or was a failed coup d'état by Nazi Party ( or NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and othe ...

in 1923. The editor of an SPD newspaper sued the journal for defamation

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

, giving rise to what is known as the ''Munich Dolchstoßprozess'' from 19 October to 20 November 1925. Many prominent figures testified in that trial, including members of the parliamentary committee investigating the reasons for the defeat, so some of its results were made public long before the publication of the committee report in 1928.

World War II

The Allied policy of

The Allied policy of unconditional surrender

An unconditional surrender is a surrender in which no guarantees are given to the surrendering party. It is often demanded with the threat of complete destruction, extermination or annihilation.

In modern times, unconditional surrenders most ofte ...

was devised in 1943 in part to avoid a repetition of the stab-in-the-back myth. According to historian John Wheeler-Bennett

Sir John Wheeler Wheeler-Bennett (13 October 1902 – 9 December 1975) was a conservative English historian of German and diplomatic history, and the official biographer of King George VI. He was well known in his lifetime, and his inter ...

, speaking from the British perspective,It was necessary for the Nazi régime and/or the German Generals to surrender unconditionally in order to bring home to the German people that they had lost the War by themselves; so that their defeat should not be attributed to a "stab in the back".

Wagnerian allusions

To some Germans, the idea of a "stab in the back" was evocative ofRichard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

's 1876 opera ''Götterdämmerung

' (; ''Twilight of the Gods''), WWV 86D, is the last in Richard Wagner's cycle of four music dramas titled (''The Ring of the Nibelung'', or ''The Ring Cycle'' or ''The Ring'' for short). It received its premiere at the on 17 August 1876, as p ...

'', in which Hagen

Hagen () is the Largest cities in Germany, 41st-largest List of cities and towns in Germany, city in Germany. The municipality is located in the States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It is located on the south eastern edge of the R ...

murders his enemy Siegfried

Siegfried is a German-language male given name, composed from the Germanic elements ''sig'' "victory" and ''frithu'' "protection, peace".

The German name has the Old Norse cognate ''Sigfriðr, Sigfrøðr'', which gives rise to Swedish ''Sigfrid' ...

– the hero of the story – with a spear in his back.

In Hindenburg's memoirs, he compared the collapse of the German army to Siegfried's death.

Psychology of belief

Historian Richard McMasters Hunt argues in a 1958 article that the myth was an irrational belief which commanded the force of irrefutable emotional convictions for millions of Germans. He suggests that behind these myths was a sense of communal shame, not for causing the war, but for losing it. Hunt argues that it was not the guilt of wickedness, but the shame of weakness that seized Germany'snational psychology National psychology refers to the (real or alleged) distinctive psychological make-up of particular nations, ethnic groups or peoples, and to the comparative study of those characteristics in social psychology, sociology, political science and anthr ...

, and "served as a solvent of the Weimar democracy and also as an ideological cement of Hitler's dictatorship".

Equivalents in other countries

Parallel interpretations ofnational trauma National trauma is a concept in psychology and social psychology. A national trauma is one in which the effects of a trauma apply generally to the members of a collective group such as a country or other well-defined group of people. Trauma is an in ...

after military defeat appear in other countries. For example, it was applied to the United States' involvement in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

and in the mythology of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an History of the United States, American pseudohistorical historical negationist, negationist mythology that claims the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil Wa ...

.

See also

*Austria victim theory

The victim theory (german: Opferthese), encapsulated in the slogan "Austria – the Nazis' first victim", was the ideological basis for Austria under allied occupation (1945–1955) and in the Second Austrian Republic until the 1980s. According ...

* Causes of World War II

The causes of World War II, a global war from 1939 to 1945 that was the deadliest conflict in human history, have been given considerable attention by historians from many countries who studied and understood them. The immediate precipitating ...

* Centre for the Study of the Causes of the War

The Centre for the Study of the Causes of the War (in German: Zentralstelle zur Erforschung der Kriegsursachen) was a think tank based in Berlin, funded by the German government, whose sole purpose was to disseminate the official government positio ...

* Defeatism

Defeatism is the acceptance of defeat without struggle, often with negative connotations. It can be linked to pessimism in psychology, and may sometimes be used synonymously with fatalism or determinism.

History

The term ''defeatism'' is commonly ...

* Genocide justification

Genocide justification is the claim that a genocide is morally excusable or necessary, in contrast to genocide denial, which rejects that genocide occurred. Perpetrators often claim that the genocide victims presented a serious threat, meaning th ...

* German Revolution of 1918–19

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

* Holocaust inversion

Comparisons between Israel and Nazi Germany have been made since the 1940s, taking place first within the larger context of the aftermath of World War II. Such comparisons are a rhetorical staple of anti-Zionism in relation to the Israeli–P ...

* Jewish war conspiracy theory

The claim that there was a Jewish war against Nazi Germany is an antisemitic conspiracy theory promoted in Nazi propaganda which asserts that Jews, acting as a single historical actor, started World War II and sought the destruction of German ...

* More German than the Germans

The assimilated Jewish community in Germany, prior to World War II, has been self-described as "more German than the Germans". Originally, the comment was a "common sneer aimed at people" who had "thrown off the faith of their forefathers and adop ...

, a contrasting trope about German Jewry.

* Secondary antisemitism

Secondary antisemitism is a distinct form of antisemitism which is said to have appeared after the end of World War II. Secondary antisemitism is often explained as being caused by the Holocaust, as opposed to existing in spite of it. One frequent ...

References

Informational notes Citations Bibliography * * * * * * Further reading * * * *External links

Antisemitism

on the

Florida Holocaust Museum

The Florida Holocaust Museum is a Holocaust museum located at 55 Fifth Street South in St. Petersburg, Florida. Founded in 1992, it moved to its current location in 1998. Formerly known as the Holocaust Center, the museum officially changed to i ...

website

Die Judischen Gefallenen

A Roll of Honor Commemorating the 12,000 German Jews Who Died for their Fatherland in World War I.

{{Nationalism Antisemitic canards German nationalism German Revolution of 1918–1919 Military history of Germany during World War II Propaganda legends Weimar Republic Historiography of World War I Historical negationism Right-wing antisemitism Victimology Conspiracy theories involving Jews Antisemitism in Germany Aftermath of World War I