Norris E. Bradbury on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Norris Edwin Bradbury (May 30, 1909 – August 20, 1997), was an American

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

who served as director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, ...

for 25 years from 1945 to 1970. He succeeded Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is often ...

, who personally chose Bradbury for the position of director after working closely with him on the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Bradbury was in charge of the final assembly of "the Gadget

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert abo ...

", detonated in July 1945 for the Trinity test

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert abo ...

.

Bradbury took charge at Los Alamos at a difficult time. Staff were leaving in droves, living conditions were poor and there was a possibility that the laboratory would close. He managed to persuade enough staff to stay, and got the University of California to renew the contract to manage the laboratory. He pushed continued development of nuclear weapons, transforming them from laboratory devices to production models. Numerous improvements made them safer, more reliable and easier to store and handle, and made more efficient use of scarce fissionable materiel.

In the 1950s Bradbury oversaw the development of thermonuclear weapon

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a low ...

s, although a falling-out with Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

over the priority given to their development led to the creation of a rival nuclear weapons laboratory, the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a federal research facility in Livermore, California, United States. The lab was originally established as the University of California Radiation Laboratory, Livermore Branch in 1952 in respons ...

. In later years, he branched out, constructing the Los Alamos Meson Physics Facility to develop the laboratory's role in nuclear science, and during the Space Race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the t ...

of the 1960s, the laboratory developed the Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application (NERVA). The Bradbury Science Museum

The Bradbury Science Museum is the chief public facility of Los Alamos National Laboratory, located at 1350 Central Avenue in Los Alamos, New Mexico, in the United States. It was founded in 1953, and was named for the Laboratory's second directo ...

is named in his honor.

Early life

Norris Bradbury was born inSanta Barbara, California

Santa Barbara ( es, Santa Bárbara, meaning "Saint Barbara") is a coastal city in Santa Barbara County, California, of which it is also the county seat. Situated on a south-facing section of coastline, the longest such section on the West Co ...

, on May 30, 1909, one of four children of Edwin Pearly and his wife Elvira née Clausen. One sister died as an infant, and the family adopted twins Bobby and Betty, both of whom served in the United States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through combi ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Bradbury was educated at Hollywood High School and Chaffey High School

Chaffey High School is a public high school in Ontario, California, United States. It is part of the Chaffey Joint Union High School District and rests on approximately , making it one of the largest high schools by area in California. The schoo ...

in Ontario, California

Ontario is a city in southwestern San Bernardino County in the U.S. state of California, east of downtown Los Angeles and west of downtown San Bernardino, the county seat. Located in the western part of the Inland Empire metropolitan area, ...

, graduating at the age of 16. He then attended Pomona College

Pomona College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Claremont, California. It was established in 1887 by a group of Congregationalists who wanted to recreate a "college of the New England type" in Southern California. In 1925, it became t ...

in Claremont, California, from which he graduated summa cum laude with a Bachelor of Arts (BA) in chemistry in 1929. This earned him membership of the Phi Beta Kappa Society. At Pomona, he met Lois Platt, an English Literature major who was the sister of his college roommate. They were married in 1933, and had three sons, James, John, and David. Norris was an active member of an Episcopal church.

Bradbury became interested in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

, and did graduate work at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

, where he was a teaching fellow from 1929 to 1931, and then a Whiting Foundation fellow from 1931 to 1932. He submitted a PhD thesis on ''Studies on the mobility of gaseous ions'' under the supervision of Leonard B. Loeb, and was awarded a National Research Council National Research Council may refer to:

* National Research Council (Canada), sponsoring research and development

* National Research Council (Italy), scientific and technological research, Rome

* National Research Council (United States), part of ...

fellowship.

As well as supervising Bradbury's thesis, Loeb, who had served as a naval reservist during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, encouraged Bradbury to apply for a commission as a naval reservist. Bradbury's commission as an ensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

was signed by Lieutenant Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding ran ...

Chester W. Nimitz, who was the head of the Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps

The Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC) program is a college-based, commissioned officer training program of the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps.

Origins

A pilot Naval Reserve unit was established in September 1 ...

at Berkeley at the time.

After two years at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

, Bradbury became an assistant professor of physics at Stanford University in 1935, rising to become an associate professor in 1938, and a full professor in 1943. He became an expert on the electrical conductivity of gases, the properties of ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conve ...

s, and the behavior of atmospheric electricity

Atmospheric electricity is the study of electrical charges in the Earth's atmosphere (or that of another planet). The movement of charge between the Earth's surface, the atmosphere, and the ionosphere is known as the global atmospheric electr ...

, publishing in journals including the '' Physical Review'', ''Journal of Applied Physics

The ''Journal of Applied Physics'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal with a focus on the physics of modern technology. The journal was originally established in 1931 under the name of ''Physics'', and was published by the American Physical So ...

'', ''Journal of Chemical Physics

''The Journal of Chemical Physics'' is a scientific journal published by the American Institute of Physics that carries research papers on chemical physics.Bradbury-Nielsen shutter, a type of electrical ion gate, widely used in mass spectrometry in both

In June 1944, Bradbury received orders from Parsons, who was now the deputy director of the

In June 1944, Bradbury received orders from Parsons, who was now the deputy director of the

Oppenheimer submitted his resignation as director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, but remained until a successor could be found. The director of the Manhattan Project,

Oppenheimer submitted his resignation as director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, but remained until a successor could be found. The director of the Manhattan Project,  Bradbury pushed continued development of nuclear weapons to take them from laboratory devices to production models. There were numerous improvements that could make them more safe, reliable and easy to store and handle, and make more efficient use of scarce fissionable materiel. While Bradbury gave priority to improved fission weapons, research still continued on "Alarm Clock", a boosted nuclear weapon, and the " Super", a

Bradbury pushed continued development of nuclear weapons to take them from laboratory devices to production models. There were numerous improvements that could make them more safe, reliable and easy to store and handle, and make more efficient use of scarce fissionable materiel. While Bradbury gave priority to improved fission weapons, research still continued on "Alarm Clock", a boosted nuclear weapon, and the " Super", a

Bradbury retired as director of Los Alamos Laboratory in 1970. His successor,

Bradbury retired as director of Los Alamos Laboratory in 1970. His successor,

1985 Audio Interview with Norris Bradbury by Martin Sherwin

Voices of the Manhattan Project * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bradbury, Norris 1909 births 1997 deaths 20th-century American physicists Manhattan Project people Los Alamos National Laboratory personnel People from Los Alamos, New Mexico Enrico Fermi Award recipients People from Ontario, California People from Santa Barbara, California Recipients of the Legion of Merit United States Navy reservists United States Navy officers Mass spectrometrists Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Fellows of the American Physical Society Pomona College alumni UC Berkeley College of Letters and Science alumni Military personnel from California

time-of-flight

Time of flight (ToF) is the measurement of the time taken by an object, particle or wave (be it acoustic, electromagnetic, etc.) to travel a distance through a medium. This information can then be used to measure velocity or path length, or as a w ...

mass spectrometers and ion mobility spectrometer

Ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) is an analytical technique used to separate and identify ionized molecules in the gas phase based on their mobility in a carrier buffer gas. Though heavily employed for military or security purposes, such as detect ...

s.

World War II

Bradbury was called up for service in World War II in early 1941, although the Navy allowed him to stay at Stanford until the end of the academic year. He was then sent to the Naval Proving Ground atDahlgren, Virginia

Dahlgren is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in King George County, Virginia, United States. The population was 2,946 at the time of the 2020 census, up from 2,653 at the 2010 census, and up from 997 in 2000.

History ...

, to work on external ballistics

External ballistics or exterior ballistics is the part of ballistics that deals with the behavior of a projectile in flight. The projectile may be powered or un-powered, guided or unguided, spin or fin stabilized, flying through an atmosphere o ...

. Already working at Dahlgren were Loeb and Commander Deak Parsons

Rear Admiral William Sterling "Deak" Parsons (26 November 1901 – 5 December 1953) was an American naval officer who worked as an ordnance expert on the Manhattan Project during World War II. He is best known for being the weaponeer on the ''En ...

.

In June 1944, Bradbury received orders from Parsons, who was now the deputy director of the

In June 1944, Bradbury received orders from Parsons, who was now the deputy director of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

's Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

, to report to Albuquerque, New Mexico. Parsons explained that he needed Bradbury to work on the explosive lens

An explosive lens—as used, for example, in nuclear weapons—is a highly specialized shaped charge. In general, it is a device composed of several explosive charges. These charges are arranged and formed with the intent to control the shape ...

es required by an implosion-type nuclear weapon

Nuclear weapon designs are physical, chemical, and engineering arrangements that cause the physics package of a nuclear weapon to detonate. There are three existing basic design types:

* pure fission weapons, the simplest and least technically ...

. Bradbury was less than enthusiastic about the prospect, but he was a naval officer, and ultimately agreed to go.

At Los Alamos, Bradbury became head of E-5, the Implosion Experimentation Group, which put him in charge of the implosion field test program. In August, the laboratory's director, Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is often ...

, implemented a sweeping reorganisation. E-5 became part of George Kistiakowsky

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Preside ...

's new Explosives Division (X Division), and was renumbered X-1. At this point, Bradbury was leading some of the most critical work at the laboratory, as it struggled with the jets that spoiled the perfect spherical shape desired for the implosion process. These were examined with a combination of magnetic, X-ray

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nb ...

and RaLa

Ras-related protein Ral-A (RalA) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''RALA'' gene on chromosome 7. This protein is one of two paralogs of the Ral protein, the other being RalB, and part of the Ras GTPase family. RalA functions as a mole ...

techniques.

In March 1945, Oppenheimer created Project Alberta

Project Alberta, also known as Project A, was a section of the Manhattan Project which assisted in delivering the first nuclear weapons in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II.

Project Alberta was formed in March 1 ...

under Parsons to carry out the Manhattan Project's ultimate mission: the preparation and delivery of nuclear weapons in combat. Bradbury was transferred to Project Alberta to head the Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

assembly group. In July 1945, Bradbury supervised the preparation of "the Gadget", as the bomb was known, at the Trinity nuclear test

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert abo ...

. "For me to say", Bradbury later recalled, "I had any deep emotional thoughts about Trinity... I didn't. I was just damned pleased that it went off."

Director of Los Alamos

Oppenheimer submitted his resignation as director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, but remained until a successor could be found. The director of the Manhattan Project,

Oppenheimer submitted his resignation as director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, but remained until a successor could be found. The director of the Manhattan Project, Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Leslie R. Groves, Jr., wanted someone with both a solid academic background and a high standing within the project. Oppenheimer recommended Bradbury. This was agreeable to Groves, who liked the fact that as a naval officer Bradbury was both a military man and a scientist. Bradbury accepted the offer on a six-month trial basis.

Parsons arranged for Bradbury to be quickly discharged from the Navy, which awarded him the Legion of Merit for his wartime services. He remained in the Naval Reserve, though, ultimately retiring in 1961 with the rank of captain. On October 16, 1945, there was a ceremony at Los Alamos at which Groves presented the laboratory with the Army-Navy "E" Award

The Army-Navy "E" Award was an honor presented to companies during World War II whose production facilities achieved "Excellence in Production" ("E") of war equipment. The award was also known as the Army-Navy Production Award. The award was cr ...

, and presented Oppenheimer with a certificate of appreciation. Bradbury became the laboratory's second director the following day.

The first months of Bradbury's directorship were particularly difficult. He had hoped that Atomic Energy Act of 1946 would be quickly passed by Congress and the wartime Manhattan Project would be superseded by a new, permanent organization. It soon became clear that this would take more than six months. President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

did not sign the act creating the Atomic Energy Commission into law until August 1, 1946, and it did not become active until January 1, 1947. In the meantime, Groves' legal authority to act was limited.

Most of the scientists at Los Alamos were eager to return to their laboratories and universities, and by February 1946 all of the wartime division heads had left, but a talented core remained. Darol Froman became head of Robert Bacher's G division, now renamed M Division. Eric Jette became responsible for Chemistry and Metallurgy, John H. Manley for Physics, George Placzek

George Placzek (; September 26, 1905 – October 9, 1955) was a Moravian physicist.

Biography

Placzek was born into a wealthy Jewish family in Brünn, Moravia (now Brno, Czech Republic), the grandson of Chief Rabbi Baruch Placzek.PDF He studied ...

for Theory, Max Roy for Explosives, and Roger Wagner for Ordnance. The number of personnel at Los Alamos plummeted from its wartime peak of over 3,000 to around 1,000, but many were still living in temporary wartime accommodation. To make matters worse, the water pipe to Los Alamos froze and the water had to be supplied by tanker trucks. Despite the reduced staff, Bradbury still had to provide support for Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

, the nuclear tests in the Pacific.

Bradbury pushed continued development of nuclear weapons to take them from laboratory devices to production models. There were numerous improvements that could make them more safe, reliable and easy to store and handle, and make more efficient use of scarce fissionable materiel. While Bradbury gave priority to improved fission weapons, research still continued on "Alarm Clock", a boosted nuclear weapon, and the " Super", a

Bradbury pushed continued development of nuclear weapons to take them from laboratory devices to production models. There were numerous improvements that could make them more safe, reliable and easy to store and handle, and make more efficient use of scarce fissionable materiel. While Bradbury gave priority to improved fission weapons, research still continued on "Alarm Clock", a boosted nuclear weapon, and the " Super", a thermonuclear weapon

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a low ...

s design. The new fission designs were tested during Operation Sandstone

Operation Sandstone was a series of nuclear weapon tests in 1948. It was the third series of American tests, following Trinity in 1945 and Crossroads in 1946, and preceding Ranger. Like the Crossroads tests, the Sandstone tests were carried ou ...

in 1948. The Mark 4 nuclear bomb

The Mark 4 nuclear bomb was an American implosion-type nuclear bomb based on the earlier Mark 3 Fat Man design, used in the Trinity test and the bombing of Nagasaki. With the Mark 3 needing each individual component to be hand-assembled by only h ...

became the first nuclear weapon to be mass-produced on an assembly line.

As the future became more certain, Bradbury began looking for a new site for the laboratory away from the crowded town center. In 1948, Bradbury submitted a proposal to the Atomic Energy Commission for a new $107 million facility on the South Mesa, linked to the town by a new bridge over the canyon.

All this time, Bradbury remained nominally a professor in absentia at Stanford. The Los Alamos Laboratory was nominally run under a wartime contract with the University of California, but a clause in the contract allowed the University to terminate the contract three months after the end of the war. The university duly served notice, but Bradbury managed to get it rescinded, and in 1948 the contract was renewed. In 1951, he became a professor at the University of California.

By 1951, the laboratory had come up with the Teller-Ulam design

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

, and thermonuclear tests were conducted during Operation Greenhouse

Operation Greenhouse was the fifth American nuclear test series, the second conducted in 1951 and the first to test principles that would lead to developing thermonuclear weapons (''hydrogen bombs''). Conducted at the new Pacific Proving Gro ...

. Tensions between Bradbury and Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

over the degree of priority given to thermonuclear weapons development led to the creation of a second nuclear weapons laboratory, the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a federal research facility in Livermore, California, United States. The lab was originally established as the University of California Radiation Laboratory, Livermore Branch in 1952 in respons ...

.

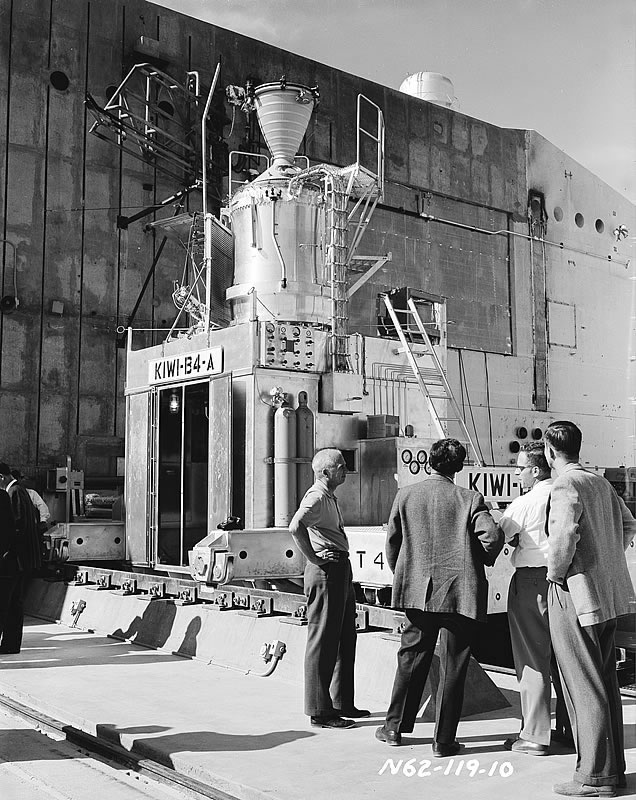

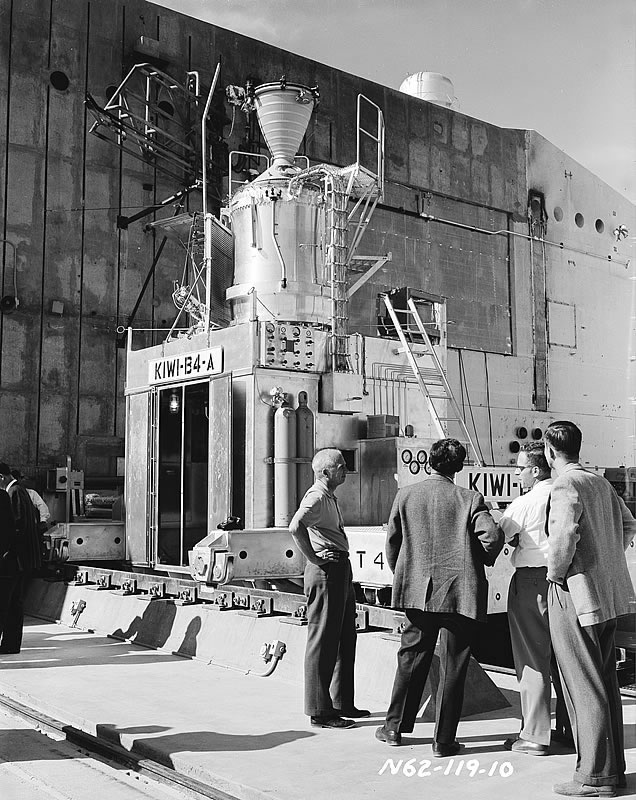

In later years, Bradbury branched out, constructing the Los Alamos Meson Physics Facility to develop the laboratory's role in nuclear science. During the Space Race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the t ...

of the 1960s, the laboratory worked on Project Rover

Project Rover was a United States project to develop a nuclear-thermal rocket that ran from 1955 to 1973 at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory (LASL). It began as a United States Air Force project to develop a nuclear-powered upper stage for ...

, developing the Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application (NERVA). The laboratory demonstrated the feasibility and value of nuclear rocket propulsion.

For many years, Bradbury was responsible for much of the administration of the town of Los Alamos. The town established impressive health and education facilities. Eventually the new technical area was built outside the town, and on February 18, 1957, the security gates were taken down. Finally, the town became an incorporated community and the director's civic responsibilities ended.

In 1966, Bradbury was awarded the Department of Defense Medal for Distinguished Public Service

The Department of Defense Medal for Distinguished Public Service is the highest award that is presented by the Secretary of Defense, to a private citizen, politician, non-career federal employee, or foreign national. It is presented for exceptiona ...

for "exceptionally meritorious civilian service to the Armed Forces and the United States of America in a position of great responsibility as director, Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory". His citation went on to say that "The outstanding international reputation of the Los Alamos Laboratory is directly attributable to his exceptional leadership. The United States is indebted to Dr. Bradbury and his laboratory, to a very large degree, for our present nuclear capability." He also received the Enrico Fermi Award

The Enrico Fermi Award is a scientific award conferred by the President of the United States. It is awarded to honor scientists of international stature for their lifetime achievement in the development, use, or production of energy. It was establ ...

in 1970. In 1971, he received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a non-profit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest achieving individuals in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet ...

.

Later life

Bradbury retired as director of Los Alamos Laboratory in 1970. His successor,

Bradbury retired as director of Los Alamos Laboratory in 1970. His successor, Harold Agnew

Harold Melvin Agnew (March 28, 1921 – September 29, 2013) was an American physicist, best known for having flown as a scientific observer on the Hiroshima bombing mission and, later, as the third director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory ...

, invited him to become a senior consultant, but Bradbury declined the offer, although he did serve as a consultant for other government agencies, including the National Academy of Sciences, and as a member of the boards of the Los Alamos Medical Center, the First National Bank of Santa Fe, the Los Alamos YMCA and the Santa Fe Neurological Society.

In 1969 the governor of New Mexico

, insignia = Seal of the Governor of New Mexico.svg

, insigniasize = 110px

, insigniacaption = Seal of the Governor

, image = File:Michelle Lujan Grisham 2021.jpg

, imagesize = 200px

, alt =

, incumbent = Michelle Lujan Grisham

, inc ...

, David Cargo

David Francis Cargo (January 13, 1929 – July 5, 2013) was an American attorney and politician who served as the List of governors of New Mexico, 22nd governor of New Mexico between 1967 and 1971.

Early life and education

Cargo was born in ...

, appointed Bradbury as a regent of the University of New Mexico

The University of New Mexico (UNM; es, Universidad de Nuevo México) is a public research university in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Founded in 1889, it is the state's flagship academic institution and the largest by enrollment, with over 25,400 ...

, but this was a turbulent time for the university. In response to the Kent State Shootings

The Kent State shootings, also known as the May 4 massacre and the Kent State massacre,"These would be the first of many probes into what soon became known as the Kent State Massacre. Like the Boston Massacre almost exactly two hundred years bef ...

in May 1970, students and antiwar activist Jane Fonda marched on the home of Ferrel Heady, the president of the University of New Mexico. When he refused to meet with them, the students called a strike. Classes were cancelled, rallies were held and students occupied the Student Union Building. Cargo called in the New Mexico National Guard to remove them, and eleven people were bayoneted. Cargo's successor, Bruce King

Bruce King (April 6, 1924 – November 13, 2009) was an American businessman and politician who for three non-consecutive four-year terms was the governor of New Mexico. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the longest-serving governor in N ...

, replaced Bradbury and another regent.

In the mid-1990s, Bradbury accidentally hit his leg while chopping firewood. Gangrene set in, and his right leg was amputated below the knee. It spread to his left leg, and part of his left foot was amputated, leaving him in a wheelchair. The disease eventually proved fatal, and he died on August 20, 1997. He was survived by his wife Lois, who died in January 1998, and his three sons. A funeral service was held in Los Alamos, and he was buried at Guaje Pines Cemetery in Los Alamos.

Notes

References

* * * * * * *External links

1985 Audio Interview with Norris Bradbury by Martin Sherwin

Voices of the Manhattan Project * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bradbury, Norris 1909 births 1997 deaths 20th-century American physicists Manhattan Project people Los Alamos National Laboratory personnel People from Los Alamos, New Mexico Enrico Fermi Award recipients People from Ontario, California People from Santa Barbara, California Recipients of the Legion of Merit United States Navy reservists United States Navy officers Mass spectrometrists Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Fellows of the American Physical Society Pomona College alumni UC Berkeley College of Letters and Science alumni Military personnel from California