Norman Cross Prison on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Norman Cross Prison in

Norman Cross Prison in

The

The

The average prison population was about 5,500 men. The lowest number recorded was 3,300 in October 1804 and 6,272 on 10 April 1810 was the highest number of prisoners recorded in any official document.

Norman Cross was intended to be a model depot providing the most humane treatment of prisoners of war. Sir

The average prison population was about 5,500 men. The lowest number recorded was 3,300 in October 1804 and 6,272 on 10 April 1810 was the highest number of prisoners recorded in any official document.

Norman Cross was intended to be a model depot providing the most humane treatment of prisoners of war. Sir

At the outbreak of the war, the Transport Board wrote that "the prisoners in all the depots in the country are at full liberty to exercise their industry within the prisons, in manufacturing and selling any articles they may think proper excepting those which would affect the Revenue in opposition to the Laws, obscene toys and drawings, or articles made either from their clothing or the prison stores".

At the outbreak of the war, the Transport Board wrote that "the prisoners in all the depots in the country are at full liberty to exercise their industry within the prisons, in manufacturing and selling any articles they may think proper excepting those which would affect the Revenue in opposition to the Laws, obscene toys and drawings, or articles made either from their clothing or the prison stores".

Many prisoners at Norman Cross made artefacts such as toys, model ships and

Many prisoners at Norman Cross made artefacts such as toys, model ships and

Insubordination was rife among prisoners. A force of

Insubordination was rife among prisoners. A force of

In April 1815 '1,000 Yards of capital Board Fencing, now standing round the burial ground appropriated to the late French prisoners, near Norman Cross Inn' were advertised for sale.

The wooden buildings were dismantled in June 1816 and the parts sold at auction. Some of the buildings were relocated to nearby towns although much of the timber structures were sold as firewood.

The site is considered of national importance and has been classified as a

In April 1815 '1,000 Yards of capital Board Fencing, now standing round the burial ground appropriated to the late French prisoners, near Norman Cross Inn' were advertised for sale.

The wooden buildings were dismantled in June 1816 and the parts sold at auction. Some of the buildings were relocated to nearby towns although much of the timber structures were sold as firewood.

The site is considered of national importance and has been classified as a

The memorial to the 1,770 prisoners who died at Norman Cross was erected in 1914 by the Entente Cordiale Society beside the Great North Road. The bronze

The memorial to the 1,770 prisoners who died at Norman Cross was erected in 1914 by the Entente Cordiale Society beside the Great North Road. The bronze

Fort in the Fens

Friends of Norman Cross

The Fens

Norman Cross pages 20–21

Time Team Series 17: Death and Dominoes – The First POW Camp (Norman Cross, Cambridgeshire)

Wessex Archaeology.

Norman Cross, Cambridgeshire Flickr collection

Walker, Thomas James, ''The Depot for Prisoners of War at Norman Cross, Huntingdonshire, 1796 to 1816'', London, Constable, 1913

E-book version (very poorly proof-read)

Time Team - Norman Cross

"Once Our Foe - The shooting of Jean DeNarde"

- a documentary about the shooting of a prisoner in transit to Norman Cross {{Prisons in the East of England Prisons in Cambridgeshire Monuments and memorials in Cambridgeshire Prisoner of war camps in England Scheduled monuments in Cambridgeshire Defunct prisons in England Napoleonic Wars Yaxley, Cambridgeshire

Norman Cross Prison in

Norman Cross Prison in Huntingdonshire

Huntingdonshire (; abbreviated Hunts) is a non-metropolitan district of Cambridgeshire and a historic county of England. The district council is based in Huntingdon. Other towns include St Ives, Godmanchester, St Neots and Ramsey. The popul ...

, England, was the world's first purpose-built prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military prisons. P ...

or "depot", built in 1796–97 to hold prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

from France and its allies during the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

and Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. After the Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on perio ...

the depot was emptied of prisoners and, in 1816, largely demolished.

Norman Cross lies south of Peterborough

Peterborough () is a cathedral city in Cambridgeshire, east of England. It is the largest part of the City of Peterborough unitary authority district (which covers a larger area than Peterborough itself). It was part of Northamptonshire until ...

, Cambridgeshire, between the villages of Folksworth

Folksworth is a village in Cambridgeshire, England. Folksworth lies approximately south-west of Peterborough, just off the A1 road (Great Britain), A1(M). Folksworth is in the civil parishes in England, civil parish of Folksworth and Washingl ...

, Stilton

Stilton is a village and civil parish in Cambridgeshire, England, about north of Huntingdon in Huntingdonshire, which is a non-metropolitan district of Cambridgeshire as well as a historic county of England.

History

There is evidence of Neo ...

and Yaxley. The junction of the A1 and A15 roads is here. Traditionally in Huntingdonshire, Norman Cross gave its name to one of the hundreds of Huntingdonshire

Between Anglo-Saxon times and the nineteenth century Huntingdonshire was divided for administrative purposes into 4 hundred (subdivision), hundreds, plus the borough of Huntingdon. Each hundred had a separate council that met each month to rule on ...

and, from 1894 to 1974, to Norman Cross Rural District

Norman Cross was a rural district in Huntingdonshire from 1894 to 1974.

It was formed in 1894 under the Local Government Act 1894 from the part of the Peterborough rural sanitary district which was in Huntingdonshire (the rest forming part of P ...

.

Design and construction of prison camp

The

The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

Transport Board was responsible for the care of prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

. When Sir Ralph Abercromby

Lieutenant General Sir Ralph Abercromby (7 October 173428 March 1801) was a British soldier and politician. He rose to the rank of lieutenant-general in the British Army, was appointed Governor of Trinidad, served as Commander-in-Chief, Ire ...

communicated in 1796 that he was transferring 4,000 prisoners from the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

, the Board began the search for a site for a new prison. The site was chosen because it was on the Great North Road only north of London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

and was deemed far enough from the coast that escaped prisoners could not easily flee back to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. The site had a good water supply and close to sufficient local sources of food to sustain many thousands of prisoners and the guards. Work commenced in December 1796 with much of the timber building prefabricated in London and assembled on site. 500 carpenters and labourers worked on the site for 3 months. The cost of construction was £34,581 11s 3d.

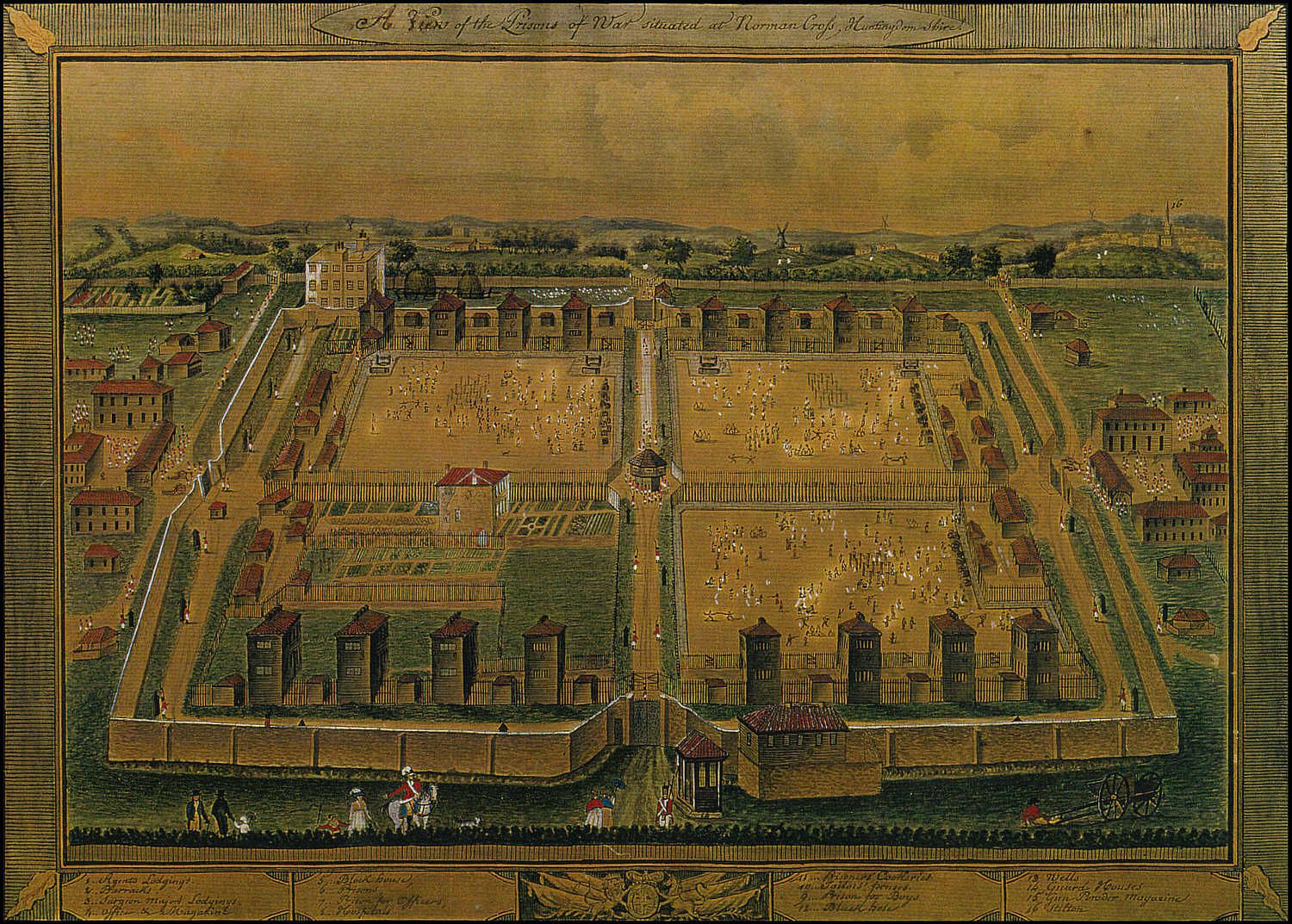

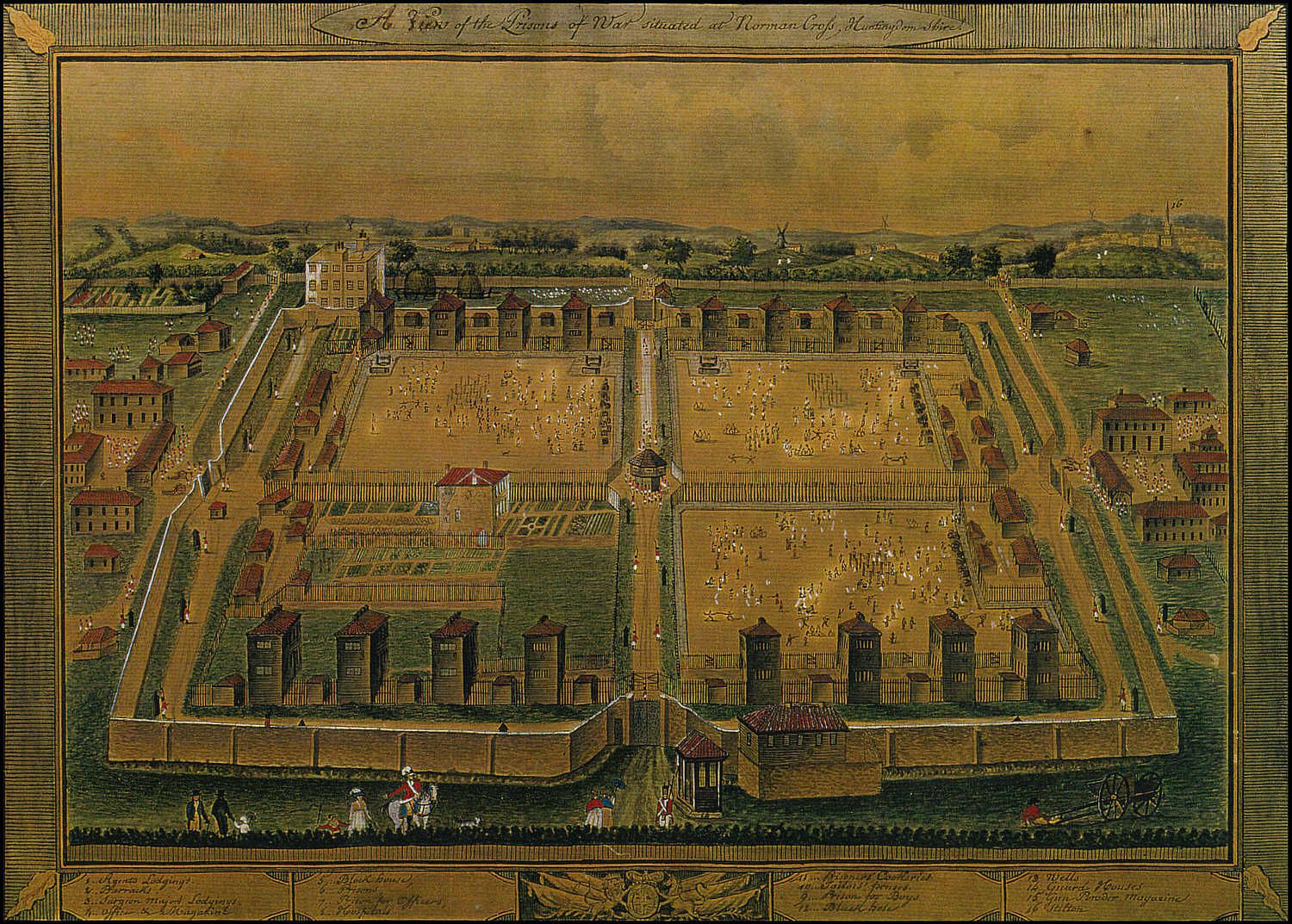

The design of the prison was based on that of a contemporary artillery fort. A ditch wide and about 5 feet deep (to prevent prisoners tunnelling out) was placed inside the wall (originally a wooden stockade fence, replaced with a brick wall in 1805) and guarded by 'silent sentries' who could not be seen by the prisoners. The barracks for the garrison were placed outside and a large guard house (known as the Block House

A blockhouse is a small fortification, usually consisting of one or more rooms with loopholes, allowing its defenders to fire in various directions. It is usually an isolated fort in the form of a single building, serving as a defensive stron ...

) containing troops and six cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

was placed right at the centre. The interior of the prison was divided into four quadrangles, each with four double-storey wooden accommodation blocks for 500 prisoners and four ablutions blocks. One accommodation block was reserved for officers. Half of each quadrangle was a large exercise yard. The north-east quadrangle contained the prison hospital. There was also a windowless block known as the Black Hole in which prisoners were kept shackled on half rations as punishment, mainly for violence towards the guards although two prisoners were sent to the Black Hole for " infamous vices". 30 well

A well is an excavation or structure created in the ground by digging, driving, or drilling to access liquid resources, usually water. The oldest and most common kind of well is a water well, to access groundwater in underground aquifers. The ...

s were sunk to draw drinking water for the prisoners and garrison.

Operation

The average prison population was about 5,500 men. The lowest number recorded was 3,300 in October 1804 and 6,272 on 10 April 1810 was the highest number of prisoners recorded in any official document.

Norman Cross was intended to be a model depot providing the most humane treatment of prisoners of war. Sir

The average prison population was about 5,500 men. The lowest number recorded was 3,300 in October 1804 and 6,272 on 10 April 1810 was the highest number of prisoners recorded in any official document.

Norman Cross was intended to be a model depot providing the most humane treatment of prisoners of war. Sir Rupert George

Captain Sir Rupert George, 1st Baronet (16 January 1749, St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin, Ireland – 25 January 1823, Willesden, London Borough of Brent, Greater London, England) was a British naval officer in the American Revolution, became the ...

was responsible for the "care and custody" of the French prisoners.

Most of the men held in the prison were low-ranking soldiers and sailors, including midshipmen and junior officers, with a small number of privateers

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

. About 100 senior officers and some civilians "of good social standing", mainly passengers on captured ships and the wives of some officers, were given '' parole d'honneur'' outside the prison, mainly in Peterborough although some as far away as Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England; ...

, Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

, Melrose and Abergavenny

Abergavenny (; cy, Y Fenni , archaically ''Abergafenni'' meaning "mouth of the River Gavenny") is a market town and community in Monmouthshire, Wales. Abergavenny is promoted as a ''Gateway to Wales''; it is approximately from the border wi ...

. They were afforded the courtesy of their rank within English society. Some "with good private means" hired servants and often dined out while wearing full uniform. Three French officers died of natural causes while on parole and were buried with full military honours. Four French officers and five Dutch officers married English women while on parole. The most senior officer on parole from the prison was General Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes who resided with his wife in Cheltenham

Cheltenham (), also known as Cheltenham Spa, is a spa town and borough on the edge of the Cotswolds in the county of Gloucestershire, England. Cheltenham became known as a health and holiday spa town resort, following the discovery of mineral s ...

from 1809 until they escaped back to France in 1811. General (1762-1816), Adjutant Commandant was confined here for breaking parole, he was allowed further parole and after again attempting to escape was sent to Chatham

Chatham may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions Canada

* Chatham Islands (British Columbia)

* Chatham Sound, British Columbia

* Chatham, New Brunswick, a former town, now a neighbourhood of Miramichi

* Chatham (electoral district), New Brunswic ...

.

Clothing

The French prisoners, whose main pastime was gambling, were accused by the British government of selling their clothes and few personal possessions to raise money for further gambling. In 1801, the British government issued statements blaming the French Consul for not supplying sufficient clothing (the British government had paid the French for all English prisoners held in France and French colonies to be clothed). In July 1801 Jeremiah Askew, a tradesman at Yaxley, was convicted of being in possession ofpalliasse

A tick mattress, bed tick or tick is a large bag made of strong, stiff, tightly-woven material (ticking). This is then filled to make a mattress, with material such as straw, chaff, horsehair, coarse wool or down feathers,Dictionnaire de l'ameub ...

s and other articles bearing the government mark of the 'broad arrow

A broad arrow, of which a pheon is a variant, is a stylised representation of a metal arrowhead, comprising a tang and two barbs meeting at a point. It is a symbol used traditionally in heraldry, most notably in England, and later by the Brit ...

'. He was sentenced to stand in the pillory

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, formerly used for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. The pillory is related to the stocks ...

at Norman Cross and two years of hard labour.

Samuel Johnson and a Mr Serle, who visited the barracks, compiled a report on behalf of the British government, stating that the proportion of food allowance was fully sufficient to maintain both life and health, but added: "provided it is not shamefully lost by gambling." The Lords of the Admiralty

This is a list of Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty (incomplete before the Restoration, 1660).

The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty were the members of The Board of Admiralty, which exercised the office of Lord High Admiral when it was ...

, along with Doctor Johnson, instructed that naked prisoners should be clothed at once, without waiting for the French supply or payment for clothing.

The British government provided each naked prisoner with a yellow suit, a grey or yellow cap, a yellow jacket, a red waistcoat, yellow trousers, a neckerchief, two shirts, two pairs of stockings, and one pair of shoes. The bright colours were chosen to aid the recognition of escaped prisoners. In Foulley's model of the prison (pictured right) more than half the prisoners are represented wearing these clothes.

Food

Food was prepared by cooks drawn from the prison ranks. The cooks, one for every 12 prisoners, were paid a small allowance by the British government. The initial daily food ration for each prisoner was 1 lb of beef, 1 lb of bread, 1 lb of potatoes, and 1 lb of cabbage orpea

The pea is most commonly the small spherical seed or the seed-pod of the flowering plant species ''Pisum sativum''. Each pod contains several peas, which can be green or yellow. Botanically, pea pods are fruit, since they contain seeds and d ...

se. As the majority of prisoners were Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

, herrings or cod was substituted for beef on Fridays. Each prisoner was also allowed 2 oz of soap per week. In November 1797 the British and French governments agreed that each should feed their own citizens in their enemy's prisons. The French provided a daily ration of 1 pint of beer, 8oz of beef or fish, 26oz of bread, 2oz of cheese and 1 lb of potato or fresh vegetables. They were also allowed 1 lb of soap and 1 lb of tobacco per month. Patients in the prison hospital were given a daily ration of 1 pint of tea morning and evening, 16oz of bread, 16oz of beef, mutton or fish, 1 pint of broth, 16oz of green vegetables or potato, and 2 pints of beer.

The British government went to great lengths to provide food of a quality at least equal to that available to locals. The senior officer from each quadrangle was permitted to inspect the food as it was delivered to the prison to ensure it was of sufficient quality.

Despite the generous supply and quality of food, some prisoners died of starvation after gambling away their rations.

Education

Most prisoners were illiterate and were offered the opportunity to learn to read and write in their native language and English. Prisoners who could read were given access to books. News on the progress of the war, including successes and defeats on both sides, was reported to prisoners. In April 1799 French prisoners at Liverpool were reported to have performed plays by Voltaire in a neat prison theatre they had constructed. In July 1799, Dutch prisoners at Norman Cross sought permission to use one building as a theatre. TheSea Lords

This is a list of Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty (incomplete before the Restoration, 1660).

The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty were the members of The Board of Admiralty, which exercised the office of Lord High Admiral when it was n ...

refused. However Foulley's model, depicting the prison as it was in about 1809, shows a theatre in the south-west quadrangle.

Religion

There was no prison chapel but a Catholic priest resided in the garrison barracks. From 1808, the formerBishop of Moulins

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Moulins (Latin: ''Dioecesis Molinensis''; French: ''Diocèse de Moulins'') is a diocese of the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church in France. The episcopal see is located in the city of Moulins. The diocese comp ...

Étienne-Jean-Baptiste-Louis des Gallois de La Tour, who lived in exile at Stilton

Stilton is a village and civil parish in Cambridgeshire, England, about north of Huntingdon in Huntingdonshire, which is a non-metropolitan district of Cambridgeshire as well as a historic county of England.

History

There is evidence of Neo ...

, was permitted by the Admiralty to minister and provide charity to the prisoners at his own expense. He later became Archbishop of Bourges

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdioc ...

.

Health

Sick prisoners were initially treated in the prison hospital by two French Navy surgeons and 24 orderlies. As the number of prisoners increased, disease spread throughout the camp. 1,020 prisoners died in atyphus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

outbreak in 1800–1801. A special 'typhus cemetery' was dug near the camp.Norman Cross Camp Cambridgeshire. Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Resultsessex Archaeology

Essex () is a Ceremonial counties of England, county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the Riv ...

September 2010

Leonard Gillespie, Surgeon to the Fleet, wrote in 1804 that pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

was common with some cases becoming fatal carditis

Carditis (pl. carditides) is the inflammation of the heart.

It is usually studied and treated by specifying it as:

* Pericarditis is the inflammation of the pericardium

* Myocarditis is the inflammation of the heart muscle

* Endocarditis is the in ...

. There were also many cases of consumption

Consumption may refer to:

*Resource consumption

*Tuberculosis, an infectious disease, historically

* Consumption (ecology), receipt of energy by consuming other organisms

* Consumption (economics), the purchasing of newly produced goods for curren ...

. A brick house for a resident British surgeon was built adjacent to the prison hospital in 1805.

A peculiar outbreak of Nyctalopia

Nyctalopia (; ), also called night-blindness, is a condition making it difficult or impossible to see in relatively low light. It is a symptom of several eye diseases. Night blindness may exist from birth, or be caused by injury or malnutrition ( ...

or night-blindness affected many of the prisoners in 1806. They became severely dyspeptic and completely blind from sunset until dawn, to the extent that their fitter companions had to lead them around the camp. Various treatments were tried and failed; finally they were cured with black hellebore

''Helleborus niger'', commonly called Christmas rose or black hellebore, is an evergreen perennial flowering plant in the buttercup family, Ranunculaceae. It is poisonous.

Although the flowers resemble wild roses (and despite its common name), ...

, given as snuff, which relieved the dyspepsia and restored their night vision within a few days.

A total of 1,770 prisoner deaths were recorded, the majority from disease, during the time the prison was in operation, although the records are incomplete.

Craft and prison economy

At the outbreak of the war, the Transport Board wrote that "the prisoners in all the depots in the country are at full liberty to exercise their industry within the prisons, in manufacturing and selling any articles they may think proper excepting those which would affect the Revenue in opposition to the Laws, obscene toys and drawings, or articles made either from their clothing or the prison stores".

At the outbreak of the war, the Transport Board wrote that "the prisoners in all the depots in the country are at full liberty to exercise their industry within the prisons, in manufacturing and selling any articles they may think proper excepting those which would affect the Revenue in opposition to the Laws, obscene toys and drawings, or articles made either from their clothing or the prison stores".

Many prisoners at Norman Cross made artefacts such as toys, model ships and

Many prisoners at Norman Cross made artefacts such as toys, model ships and dominoes

Dominoes is a family of tile-based games played with gaming pieces, commonly known as dominoes. Each domino is a rectangular tile, usually with a line dividing its face into two square ''ends''. Each end is marked with a number of spots (also ca ...

sets from carved wood or animal bone, and straw marquetry

Marquetry (also spelled as marqueterie; from the French ''marqueter'', to variegate) is the art and craft of applying pieces of veneer to a structure to form decorative patterns, designs or pictures. The technique may be applied to case furn ...

. Examples of the prisoners' craftwork were sold to visitors and passers by. Some highly skilled prisoners were commissioned by wealthy individuals, some of the prisoners becoming very rich in the process. Archdeacon William Strong, a regular visitor to the prison, notes in his diary of 23 October 1801 that he provided a piece of mahogany

Mahogany is a straight-grained, reddish-brown timber of three tropical hardwood species of the genus ''Swietenia'', indigenous to the AmericasBridgewater, Samuel (2012). ''A Natural History of Belize: Inside the Maya Forest''. Austin: Unive ...

and paid a prisoner £1 15s 6d to build a model of the Block House and £2 2s for a straw picture of Peterborough Cathedral

Peterborough Cathedral, properly the Cathedral Church of St Peter, St Paul and St Andrew – also known as Saint Peter's Cathedral in the United Kingdom – is the seat of the Church of England, Anglican Bishop of Peterborough, dedicated to Sain ...

.

Prisoners were permitted to sell artefacts twice a week at the local market, or daily at the prison gate. Prices were regulated so the prisoners did not undersell local industries. In return, prisoners were permitted to buy additional food, tobacco, wine, clothes or materials for further work. In 1813 ten inmates on behalf of the prisoners were allowed to attend the sale of articles, a long tent was erected in the barrack-yard, where these were exhibited to the visitors, who had purchased articles through the summer, to the amount of £50 to £60 a week.

At the end of the war, the Transport Board noted that some prisoners had earned as much as 100 guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from t ...

. An advert in 1814 demonstrated that some items were made collectively and others by a solo craftsman.

Thousands of Norman Cross artefacts survive today in local museums, including 800 in Peterborough Museum

Peterborough () is a cathedral city in Cambridgeshire, east of England. It is the largest part of the City of Peterborough unitary authority district (which covers a larger area than Peterborough itself). It was part of Northamptonshire until ...

, and private collections.

A collection of model ships made at Norman Cross is on display at Arlington Court

Arlington Court is a neoclassical style country house built 1820–23, situated in the parish of Arlington, next to the parish church of St James, miles NE of Barnstaple, north Devon, England. It is a Grade II* listed building. The park and ...

in Devon.

During December 1804, prisoners Nicholas Deschamps and Jean Roubillard were discovered forging

Forging is a manufacturing process involving the shaping of metal using localized compressive forces. The blows are delivered with a hammer (often a power hammer) or a die. Forging is often classified according to the temperature at which i ...

£1 bank notes. Engraved plates of a very high standard and printing implements were found. The former was convicted of forgery and the latter of uttering

Uttering is a crime involving a person with the intent to defraud that knowingly sells, publishes or passes a forged or counterfeited document. More specifically, forgery creates a falsified document and uttering is the act of knowingly passing o ...

at the Huntingdon Assizes

The courts of assize, or assizes (), were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes e ...

in 1805. Francois Raize gave evidence for the crown. Forging banknotes was a capital offence

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

at the time. They were sentenced to death but this was commuted. They remained in Huntingdon Gaol until they received a free pardon from the Prince Regent, and were moved to Norman Cross and repatriated with the prisoners of war to France in 1814.

Prisoners at the Norman Cross site were not permitted to manufacture straw hats or bonnets (presumably so as not to impinge upon the local industry). The authorities appear to have enforced this stipulation, at Huntingdon Assizes in May 1811 John Lun, snr (12 months) and three sons (six months) were sentenced to prison for a conspiracy, in endeavouring to persuade the NCO's and privates of the garrison to permit a quantity of straw to be conveyed into the site for the purpose of making straw hats.

Insubordination and escapes

Insubordination was rife among prisoners. A force of

Insubordination was rife among prisoners. A force of Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to th ...

Militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

, a battalion of army reserve and a volunteer force from Peterborough were required to restrain the prisoners from breaking out during a particular period of defiance. As a boy, the author George Borrow

George Henry Borrow (5 July 1803 – 26 July 1881) was an English writer of novels and of travel based on personal experiences in Europe. His travels gave him a close affinity with the Romani people of Europe, who figure strongly in his work. Hi ...

lived at the camp from July 1811 to April 1813 with his father Lieutenant Thomas Borrow of the West Norfolk Militia; He described the place in ''Lavengro

''Lavengro: The Scholar, the Gypsy, the Priest'' (1851) is a work by George Borrow, falling somewhere between the genres of memoir and novel, which has long been considered a classic of 19th-century English literature. According to the author, i ...

''.

Six prisoners escaped in April 1801. Three of them were caught at Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, Lincolnshire and the remaining three were caught in a fishing boat off the Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

coast, in the hat of one was found a complete map of the Lincolnshire coast.

Each year the number of attempts to escape increased, as did the numbers in each escape. Three groups of 16 men each escaped in late 1801.

Incomplete tunnels were discovered in 1802.

In October 1804 the press reported the prisoners created a disturbance with the intention of breaking the perimeter fencing. Assistance was sent for to Peterbough. A troop of Yeomanry

Yeomanry is a designation used by a number of units or sub-units of the British Army, British Army Reserve (United Kingdom), Army Reserve, descended from volunteer British Cavalry, cavalry regiments. Today, Yeomanry units serve in a variety of ...

galloped to support, later followed by two more troops and an infantry unit. The prisoners having cut down a part of the wood enclosure during the night, nine of them effected their escape through the aperture. In another part of the prison, as soon as day light broke it was discovered they had undermined a distance of 34 feet towards the great South road; under the fosse which surrounds the prison, although it is four feet deep, and it is not discovered they had any tools. Five escapees have been taken.

During the night several prisoners escaped in February 1807.

Three escapees were retaken near Ryde heading for Southampton in April 1807.

The agent at the Depot, Captain Pressland R.N. was inviting tenders for the building of a wall, in August 1807. This may have become known to the prisoners as a major escape attempt was made.

After the second of these two major escape attempts in 1804 and 1807, the wooden stockade fence was soon replaced with a brick wall.

One prisoner, Charles Francois Marie Bourchier, stabbed a civilian Alexander Halliday while attempting to escape on 9 September 1808. He was convicted at the Huntingdon Assizes and sentenced to death by hanging. He was taken from Huntingdon Gaol on Friday 16th and executed at Norman Cross in front of the prisoners and the whole garrison. This was the only civil execution at Norman Cross. After the stabbing, the guards having seen two or three other knives, the entire prison was searched and 700 daggers were found.

On the 24th September, 1808 arrived at Calais an English sloop of 44 - tons, called the ''Margaret Anne'', William Tempel, master, of Barton, laden with 18 tons of coals. She was seized in the night of the 20th, in the Humber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal rivers Ouse and Trent. From there to the North Sea, it forms part of the boundary between th ...

, by three French prisoners, who had escaped from Norman Cross.

In November 1809 two French Navy officers, escaped by secreting themselves in the soil carts of the prison, in which they were drawn out of the confines of the depot.

In December 1809 an inquest took place on Jean Barthelemy Toohe, a French prisoner of war; who, as he was endeavouring to make his escape over the pailing of the prison, was fired at by the sentinel on duty, and the ball entering his back, he died shortly afterwards.

Duelling continued amongst prisoners. On 15 May 1811 at Norman Cross two fought with scissors attached to sticks. One duellist wounded the survivor twice, before the latter made the thrust that proved fatal.

"On Saturday the 19th an inquisition was taken at Norman Cross Barracks, on view of the body of Julien Cheral, a French prisoner of war, who met his death by a fellow prisoner of the name of Jean Francois Pons stabbing. Verdict — Self Defence.”

In January 1812, a French prisoner was shot whilst escaping after he had overpowered a guard and stolen a bayonet. The guard was committed to Huntingdon Gaol for the next assizes on a charge of manslaughter.

In August 1812 Prosper Louis, 7th Duke of Arenberg

Prosper Louis, 7th Duke of Arenberg (28 April 1785, Enghien – 27 February 1861) was the Duke of Arenberg, a principality of the Holy Roman Empire. He was also the 13th Duke of Aarschot, 2nd Duke of Meppen and 2nd prince of Recklinghausen.StaffTh ...

, was sent to Norman Cross after refusing to conform to the new reporting rules of his parole at Bridgnorth, where he was staying with his wife, Stéphanie Tascher de La Pagerie (a niece of Empress Joséphine

Joséphine Bonaparte (, born Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie; 23 June 1763 – 29 May 1814) was Empress of the French as the first wife of Emperor Napoleon I from 18 May 1804 until their marriage was annulled on 10 January 1810. ...

). After a period he agreed to follow the reporting requirement and was paroled again.

During August 1813, escaped prisoners from Norman Cross were discovered as far away as Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

.

Military units

In July 1810 theNorthumberland Militia

The Militia and Volunteers of Northumberland are those military units raised in the County independent of the regular Army. The "modern" militia dates from legislation enacted during the Seven Years' War. The volunteers had several forms and separa ...

were inspected at the barracks by Hugh Percy, 2nd Duke of Northumberland

Lieutenant General Hugh Percy, 2nd Duke of Northumberland (14 August 174210 July 1817) was an officer in the British army and later a British peer. He participated in the Battles of Lexington and Concord and the Battle of Long Island during t ...

. After he had reviewed them, the duke presented the commanding officer with £150 for the regiment to regale themselves with.

On 22 April 1812 the Edinburgh Militia relieved the 2nd West York at Yaxley barracks, and the latter regiment marched to Colchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in Essex, in the East of England. It had a population of 122,000 in 2011. The demonym is Colcestrian.

Colchester occupies the site of Camulodunum, the first major city in Roman Britain and its first capital. Colches ...

.

Men from the following units were stationed at the prison:

Arrival and repatriation

Many of the prisoners arrived viaPortsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

or Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

and were marched hundreds of miles to Norman Cross.

In April 1797 six transports having on board near 1000 French prisoners disembarked at King's Lynn

King's Lynn, known until 1537 as Bishop's Lynn and colloquially as Lynn, is a port and market town in the borough of King's Lynn and West Norfolk in the county of Norfolk, England. It is located north of London, north-east of Peterborough, no ...

from Falmouth. The prisoners, under an escort of the Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincoln ...

Militia marched from there to Norman Cross. Most prisoners arrived on foot from Portsmouth, Plymouth, Hull, Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth (), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside town and unparished area in, and the main administrative centre of, the Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. A pop ...

and other ports.

In October 1797, 300 prisoners embarked from Peterborough quay to be exchanged. The sea trip to the continent was by cartel ship

Cartel ships, in international law, are ships employed on humanitarian voyages, in particular, to carry communications or prisoners between belligerents. They fly distinctive flags, including a flag of truce. Traditionally, they were unarmed but ...

.

When the first peace was proclaimed prisoners were taken to Wisbech in lighters to join others in Wisbech Gaol to depart from the Port of Wisbech

Port of Wisbech is an inland port on the River Nene in Wisbech, Isle of Ely, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom. It is mainly used for cargo and industrial purposes, with the southern part of the port housing a number of berths for yachts. Fenland Di ...

for France.

Not all prisoners waited for repatriation after the end of the war. A number of the Dutch prisoners having expressed their readiness to enlist into the service of this country, they were taken up by the government; in January 1807 upwards of 60 of them, whose services had been accepted, were marched under an escort of the Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; cy, Sir Benfro ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county in the South West Wales, south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and the rest by sea. The count ...

Militia, to Portsmouth, to be distributed on board ships of war.

Peace was finally proclaimed with France in 1814, following Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's defeat and consequent abdication. The prisoners, the garrison guards and local people joined together in celebrations. The first division of 500 prisoners left on 5 April. The Star reported "We are sorry to add that on their way to the sea coast for embarkation, a few indulged in drinking to such excess, that two of them perished in a fit of intoxication, and nearly thirty were left on the road unable to proceed to their native land. They carry home with them about six thousand pounds in English money, being the profits on the sale of the toys, &c. which they manufactured at the depot".

The remaining prisoners left the garrison by June of 1814. A few decided to remain in England and settled near Yaxley and Stilton

Stilton is a village and civil parish in Cambridgeshire, England, about north of Huntingdon in Huntingdonshire, which is a non-metropolitan district of Cambridgeshire as well as a historic county of England.

History

There is evidence of Neo ...

.

Demolition and survivals

In April 1815 '1,000 Yards of capital Board Fencing, now standing round the burial ground appropriated to the late French prisoners, near Norman Cross Inn' were advertised for sale.

The wooden buildings were dismantled in June 1816 and the parts sold at auction. Some of the buildings were relocated to nearby towns although much of the timber structures were sold as firewood.

The site is considered of national importance and has been classified as a

In April 1815 '1,000 Yards of capital Board Fencing, now standing round the burial ground appropriated to the late French prisoners, near Norman Cross Inn' were advertised for sale.

The wooden buildings were dismantled in June 1816 and the parts sold at auction. Some of the buildings were relocated to nearby towns although much of the timber structures were sold as firewood.

The site is considered of national importance and has been classified as a scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage and d ...

. The commander of the depot was the Agent and his house survives, as the Old Governor's House. The restored stables are now a privately owned art gallery

An art gallery is a room or a building in which visual art is displayed. In Western cultures from the mid-15th century, a gallery was any long, narrow covered passage along a wall, first used in the sense of a place for art in the 1590s. The lon ...

. Norman House, the barrack master's house, also survives. Both the Old Governor's House and Norman House are Grade II listed buildings.

Memorial

The memorial to the 1,770 prisoners who died at Norman Cross was erected in 1914 by the Entente Cordiale Society beside the Great North Road. The bronze

The memorial to the 1,770 prisoners who died at Norman Cross was erected in 1914 by the Entente Cordiale Society beside the Great North Road. The bronze Imperial Eagle

The eagle is used in heraldry as a charge, as a supporter, and as a crest. Heraldic eagles can be found throughout world history like in the Achaemenid Empire or in the present Republic of Indonesia. The European post-classical symbolism of the ...

was stolen in 1990, but replaced with a new one in 2005 following a fundraising appeal.

When a section of the A1 was upgraded to motorway standard in 1998 the memorial required relocating. On 2 April 2005, the Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish soldier and Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain, serving twice as prime minister of ...

, a patron of the appeal, unveiled the restored memorial on a new site beside the A15. A replacement bronze eagle, sculpted by John Doubleday, was placed on the re-sited column.

Study

Anarchaeological dig

In archaeology, excavation is the exposure, processing and recording of archaeological remains. An excavation site or "dig" is the area being studied. These locations range from one to several areas at a time during a project and can be condu ...

was carried out on part of the site and was an episode of the Channel 4

Channel 4 is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network operated by the state-owned enterprise, state-owned Channel Four Television Corporation. It began its transmission on 2 November 1982 and was established to provide a four ...

series ''Time Team

''Time Team'' is a British television programme that originally aired on Channel 4 from 16 January 1994 to 7 September 2014. It returned online in 2022 for two episodes released on YouTube. Created by television producer Tim ...

'' in 2009. Part of the wall, an accommodation block, ablution hut and burial ground were uncovered.

Further reading

*Fort in the Fens

References

External links

Friends of Norman Cross

The Fens

Norman Cross pages 20–21

Time Team Series 17: Death and Dominoes – The First POW Camp (Norman Cross, Cambridgeshire)

Wessex Archaeology.

Norman Cross, Cambridgeshire Flickr collection

Walker, Thomas James, ''The Depot for Prisoners of War at Norman Cross, Huntingdonshire, 1796 to 1816'', London, Constable, 1913

E-book version (very poorly proof-read)

Time Team - Norman Cross

"Once Our Foe - The shooting of Jean DeNarde"

- a documentary about the shooting of a prisoner in transit to Norman Cross {{Prisons in the East of England Prisons in Cambridgeshire Monuments and memorials in Cambridgeshire Prisoner of war camps in England Scheduled monuments in Cambridgeshire Defunct prisons in England Napoleonic Wars Yaxley, Cambridgeshire