noble savage on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A noble savage is a literary stock character who embodies the concept of the indigene, outsider, wild human, an " other" who has not been "corrupted" by

A noble savage is a literary stock character who embodies the concept of the indigene, outsider, wild human, an " other" who has not been "corrupted" by

In English, the phrase ''Noble Savage'' first appeared in poet

In English, the phrase ''Noble Savage'' first appeared in poet

Many of the most incendiary passages in Raynal's book, one of the bestsellers of the eighteenth century, especially in the Western Hemisphere, are now known to have been in fact written by Diderot. Reviewing Jonathan Israel's ''Democratic Enlightenment: Philosophy, Revolution, and Human Rights'',

Many of the most incendiary passages in Raynal's book, one of the bestsellers of the eighteenth century, especially in the Western Hemisphere, are now known to have been in fact written by Diderot. Reviewing Jonathan Israel's ''Democratic Enlightenment: Philosophy, Revolution, and Human Rights'',

"The Noble Savage"

Dickens expressed repugnance for Indians and their way of life in no uncertain terms, recommending that they ought to be "civilised off the face of the earth". (Dickens's essay refers back to Dryden's well-known use of the term, not to Rousseau.) Dickens's scorn for those unnamed individuals, who, like Catlin, he alleged, misguidedly exalted the so-called "noble savage", was limitless. In reality, Dickens maintained, Indians were dirty, cruel, and constantly fighting among themselves. Dickens's satire on Catlin and others like him who might find something to admire in the American Indians or African bushmen is a notable turning point in the history of the use of the phrase.For an account of Dickens's article see Moore, "Reappraising Dickens's 'Noble Savage'" (2002): 236–243. Like others who would henceforth write about the topic, Dickens begins by disclaiming a belief in the "noble savage": Dickens' essay was arguably a pose of manly, no-nonsense realism and a defense of Christianity. At the end of it his tone becomes more recognizably humanitarian, as he maintains that, although the virtues of the savage are mythical and his way of life inferior and doomed, he still deserves to be treated no differently than Europeans were:

''The Idea of Progress: an Inquiry into its Origins and Growth''

(Reprint) New York: Cosimo Press, 2008. * Edgerton, Robert (1992). ''Sick Societies: Challenging the Myth of Primitive Harmony.'' New York: Free Press. * Edwards, Brendan Frederick R. (2008

"'He Scarcely Resembles the Real Man': images of the Indian in popular culture".

Website

''Our Legacy''

Material relating to First Nations, Metis, and Inuit, found in Saskatchewan cultural and heritage collections. * Ellingson, Ter. (2001). ''The Myth of the Noble Savage'' (Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press). * Fabian, Johannes. ''Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object'' * Fairchild, Hoxie Neale (1928). ''The Noble Savage: A Study in Romantic Naturalism'' (New York) * Fitzgerald, Margaret Mary ( 9471976). ''First Follow Nature: Primitivism in English Poetry 1725–1750''. New York: Kings Crown Press. Reprinted New York: Octagon Press. * * Hazard, Paul ( 9371947). ''The European Mind (1690–1715)''. Cleveland, Ohio: Meridian Books. * Keeley, Lawrence H. (1996) '' War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage''. Oxford: University Press. * Krech, Shepard (2000). ''The Ecological Indian: Myth and History.'' New York: Norton. * LeBlanc, Steven (2003). ''Constant battles: the myth of the peaceful, noble savage''. New York : St Martin's Press * Lovejoy, Arthur O. (1923, 1943). "The Supposed Primitivism of Rousseau's Discourse on Inequality, " Modern Philology Vol. 21, No. 2 (Nov., 1923):165–186. Reprinted in ''Essays in the History of Ideas''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1948 and 1960. * Lovejoy, A. O. and Boas, George ( 9351965). ''Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity.'' Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. Reprinted by Octagon Books, 1965. * Lovejoy, Arthur O. and George Boas. (1935). ''A Documentary History of Primitivism and Related Ideas'', vol. 1. Baltimore. * Moore, Grace (2004). ''Dickens And Empire: Discourses Of Class, Race And Colonialism In The Works Of Charles Dickens (Nineteenth Century Series)''. Ashgate. * Olupọna, Jacob Obafẹmi Kẹhinde, Editor. (2003) ''Beyond primitivism: indigenous religious traditions and modernity''. New York and London:

"British and Indian Identities in a Picture by Benjamin West"

''Eighteenth-Century Studies'' 31: 3 (Spring 1998): 283–305 * Rollins, Peter C. and John E. O'Connor, editors (1998). ''Hollywood's Indian : the Portrayal of the Native American in Film.'' Lexington, Kentucky: University of Kentucky Press. * Tinker, Chaunchy Brewster (1922). ''Nature's Simple Plan: a phase of radical thought in the mid-eighteenth century''. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. * Torgovnick, Marianna (1991). ''Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives'' (Chicago) * Whitney, Lois Payne (1934). ''Primitivism and the Idea of Progress in English Popular Literature of the Eighteenth Century''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press * Wolf, Eric R.(1982). ''Europe and the People without History''. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Massacres during the Wars of Religion: The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre: a foundational event

Louis Menand. "What Comes Naturally". A review of Steven Pinker's ''The Blank Slate'' from ''The New Yorker''

Peter Gay. "Breeding is Fundamental". ''Book Forum''. April / May 2009

{{DEFAULTSORT:Noble Savage Stock characters Multiculturalism Anthropology Cultural concepts Anti-indigenous racism Ethnic and racial stereotypes Western (genre) staples and terminology

A noble savage is a literary stock character who embodies the concept of the indigene, outsider, wild human, an " other" who has not been "corrupted" by

A noble savage is a literary stock character who embodies the concept of the indigene, outsider, wild human, an " other" who has not been "corrupted" by civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

C ...

, and therefore symbolizes humanity's innate goodness. Besides appearing in many works of fiction and philosophy, the stereotype

In social psychology, a stereotype is a generalized belief about a particular category of people. It is an expectation that people might have about every person of a particular group. The type of expectation can vary; it can be, for exampl ...

was also heavily employed in early anthropological works.

In English, the phrase first appeared in the 17th century in John Dryden

''

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the p ...

's heroic play '' The Conquest of Granada'' (1672), wherein it was used in reference to newly created man. "Savage" at that time could mean "wild beast" as well as "wild man". The phrase later became identified with the idealized picture of "nature's gentleman", which was an aspect of 18th-century sentimentalism. The noble savage achieved prominence as an oxymoronic rhetorical device after 1851, when used sarcastically as the title for a satirical essay by English novelist Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

, who some believe may have wished to disassociate himself from what he viewed as the "feminine" sentimentality of 18th- and early 19th-century romantic primitivism

Primitivism is a mode of aesthetic idealization that either emulates or aspires to recreate a "primitive" experience. It is also defined as a philosophical doctrine that considers "primitive" peoples as nobler than civilized peoples and was an o ...

.

In his ''Inquiry Concerning Virtue'' (1699), the 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury had postulated that the moral sense Moral sense theory (also known as moral sentimentalism) is a theory in moral epistemology and meta-ethics concerning the discovery of moral truths. Moral sense theory typically holds that distinctions between morality and immorality are discovered ...

in humans is natural and innate and based on feelings, rather than resulting from the indoctrination of a particular religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural ...

. Shaftesbury was reacting to Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book '' Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

's justification of an absolutist central state in his ''Leviathan

Leviathan (; he, לִוְיָתָן, ) is a sea serpent noted in theology and mythology. It is referenced in several books of the Hebrew Bible, including Psalms, the Book of Job, the Book of Isaiah, the Book of Amos, and, according to so ...

'', "Chapter XIII", in which Hobbes famously holds that the state of nature is a "war of all against all" in which men's lives are "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short". Hobbes further calls the Native Americans an example of a contemporary people living in such a state. Although writers since antiquity had described people living in conditions outside contemporary definitions of "civilization", Hobbes is credited with inventing the term "State of Nature". Ross Harrison writes that "Hobbes seems to have invented this useful term."

Contrary to what is sometimes believed, Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revol ...

never used the phrase ''noble savage'' (French '' bon sauvage''). However, the archetypical character that would later be termed ''noble savage'' appeared in French literature at least as early as Jacques Cartier (explorer of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Government of Canada, Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is ...

, speaking of the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

) and Michel de Montaigne (philosopher, speaking of the Tupinambá) in the 16th century.

Pre-history of the noble savage

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

' ''De origine et situ Germanorum'' (''Germania''), written 98 AD, has been described as a predecessor of the modern noble savage concept, which started in the 17th and 18th centuries in western European

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

travel literature

The genre of travel literature encompasses outdoor literature, guide books, nature writing, and travel memoirs.

One early travel memoirist in Western literature was Pausanias, a Greek geographer of the 2nd century CE. In the early modern pe ...

.

Ibn Tufail

Ibn Ṭufail (full Arabic name: ; Latinized form: ''Abubacer Aben Tofail''; Anglicized form: ''Abubekar'' or ''Abu Jaafar Ebn Tophail''; c. 1105 – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic theo ...

's 12th-century novel '' Hayy ibn Yaqdhan'' provides an important antecedent to the concept of the noble savage. Written to explore the idea of natural theology, the novel sees the main character, a savage isolated from society, come to knowledge of God through the observation of nature. The book would come to inspire and influence many Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

thinkers, among them Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book '' Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

, John Locke, Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists ...

, Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the g ...

and Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aes ...

. Samar Attar, ''The Vital Roots of European Enlightenment: Ibn Tufayl's Influence on Modern Western Thought'', Lexington Books, .

Following the discovery of America

The prehistory of the Americas (North, South, and Central America, and the Caribbean) begins with people migrating to these areas from Asia during the height of an ice age. These groups are generally believed to have been isolated from the peopl ...

, the phrase "savage" for indigenous peoples was used disparagingly to justify the colonization of the Americas. The concept of the savage gave Europeans the supposed right to establish colonies without considering the possibility of preexisting, functional societies.

During the late 16th and 17th centuries, the figure of the "savage"—and later, increasingly, the "good savage"—was held up as a reproach to European civilization, then in the throes of the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholics and Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estimates, between two and four mil ...

and Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battl ...

. In his famous essay "Of Cannibals ''Of Cannibals'' (''Des Cannibales'') written circa 1580 is an essay, one of those in the collection ''Essays'', by Michel de Montaigne, describing the ceremonies of the Tupinambá people in Brazil. In particular, he reported about how the group c ...

" (1580), Michel de Montaigne—himself a Catholic—reported that the Tupinambá people of Brazil ceremoniously eat the bodies of their dead enemies as a matter of honour. However, he reminded his readers that Europeans behave even more barbarously when they burn each other alive for disagreeing about religion (he implies): "One calls 'barbarism' whatever he is not accustomed to." Terence Cave comments:

In "Of Cannibals", Montaigne uses cultural

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tylor ...

(but not moral) relativism

Relativism is a family of philosophical views which deny claims to objectivity within a particular domain and assert that valuations in that domain are relative to the perspective of an observer or the context in which they are assessed. There ...

for the purpose of satire. His cannibals were neither noble nor exceptionally good, but neither were they suggested to be morally inferior to contemporary 16th-century Europeans. In this classical humanist portrayal, customs may differ but human beings in general are prone to cruelty in various forms, a quality detested by Montaigne. David El Kenz explains:

The treatment of indigenous peoples by Spanish Conquistadors also produced a great deal of bad conscience and recriminations. The Spanish priest Bartolomé de las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, Dominican Order, OP ( ; ; 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a 16th-century Spanish Empire, Spanish landowner, friar, priest, and bishop, famed as a historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman ...

, who witnessed it, may have been the first to idealize the simple life of the indigenous Americans. He and other observers praised their simple manners and reported that they were incapable of lying, especially in the course of the Valladolid debate

The Valladolid debate (1550–1551) was the first moral debate in European history to discuss the rights and treatment of an indigenous people by European colonizers. Held in the Colegio de San Gregorio, in the Spanish city of Valladolid, it ...

.

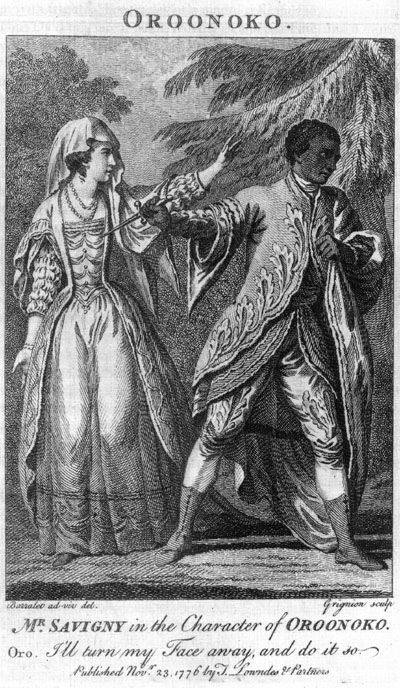

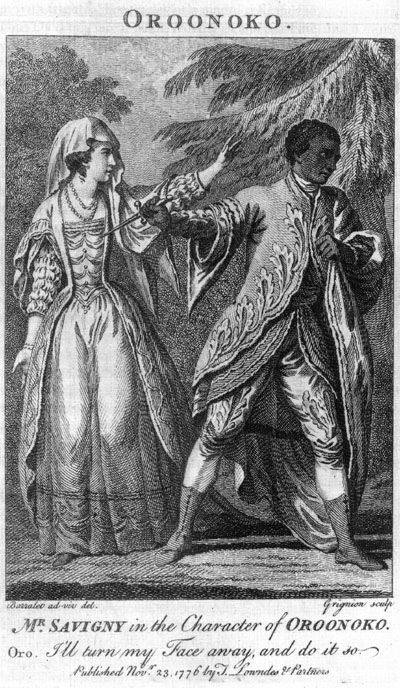

European angst over colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their rel ...

inspired fictional treatments such as Aphra Behn's novel '' Oroonoko, or the Royal Slave'' (1688), about a slave revolt in Surinam Surinam may refer to:

* Surinam (Dutch colony) (1667–1954), Dutch plantation colony in Guiana, South America

* Surinam (English colony) (1650–1667), English short-lived colony in South America

* Surinam, alternative spelling for Suriname

...

in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Great ...

. Behn's story was not primarily a protest against slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

; rather, it was written for money, and it met readers' expectations by following the conventions of the European romance novel

A romance novel or romantic novel generally refers to a type of genre fiction novel which places its primary focus on the relationship and Romance (love), romantic love between two people, and usually has an "emotionally satisfying and optimis ...

la. The leader of the revolt, Oroonoko, is truly noble in that he is a hereditary African prince, and he laments his lost African homeland in the traditional terms of a classical Golden Age. He is not a savage but dresses and behaves like a European aristocrat. Behn's story was adapted for the stage by Irish playwright Thomas Southerne, who stressed its sentimental aspects, and as time went on, it came to be seen as addressing the issues of slavery and colonialism, remaining very popular throughout the 18th century.

Origin of term

John Dryden

''

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the p ...

's heroic play, '' The Conquest of Granada'' (1672):

The hero who speaks these words in Dryden's play is here denying the right of a prince to put him to death, on the grounds that he is not that prince's subject. These lines were quoted by Scott as the heading to Chapter 22 of his "A Legend of Montrose" (1819). "Savage" is better taken here in the sense of "wild beast", so that the phrase "noble savage" is to be read as a witty conceit meaning simply the beast that is above the other beasts, or man. Ethnomusicologist Ter Ellingson believes that Dryden had picked up the expression "noble savage" from a 1609 travelogue about Canada by the French explorer Marc Lescarbot, in which there was a chapter with the ironic heading: "The Savages are Truly Noble", meaning simply that they enjoyed the right to hunt game, a privilege in France granted only to hereditary aristocrats. It is not known if Lescarbot was aware of Montaigne's stigmatization of the aristocratic pastime of hunting, though some authors believe he was familiar with Montaigne. Lescarbot's familiarity with Montaigne, is discussed by Ter Ellingson in ''The Myth of the Noble Savage''. In Dryden's day the word "savage" did not necessarily have the connotations of cruelty now associated with it. Instead, as an adjective, it could as easily mean "wild", as in a wild flower, for example. Thus he wrote in 1697, "the savage cherry grows". One scholar, Audrey Smedley, claimed that "English conceptions of 'the savage' were grounded in expansionist conflicts with Irish pastoralists and more broadly, in isolation from, and denigration of neighboring European peoples." and Ellingson agrees that "The ethnographic literature lends considerable support for such arguments". In France the stock figure that in English is called the "noble savage" has always been simply "le bon sauvage", "the good wild man", a term without any of the paradoxical frisson of the English one. Montaigne is generally credited for being at the origin of this myth in hisI am as free as nature first made man, Ere the base laws of servitude began, When wild in woods the noble savage ran.

Essays

An essay is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a letter, a paper, an article, a pamphlet, and a short story. Essays have been sub-classified as forma ...

(1580), especially "Of Coaches" and "Of Cannibals". This character, an idealized portrayal of "Nature's Gentleman", was an aspect of 18th-century sentimentalism, along with other stock characters such as, the Virtuous Milkmaid, the Servant-More-Clever-than-the-Master (such as Sancho Panza and Figaro

Figaro may refer to:

Literature

* Figaro, the central character in:

** ''The Barber of Seville'' (play), a 1775 play by Pierre Beaumarchais

*** ''The Barber of Seville'' (Paisiello), a 1782 opera by Paisiello based on the play

*** ''The Bar ...

, among countless others), and the general theme of virtue in the lowly born. The use of stock characters (especially in theater) to express moral truths derives from classical antiquity and goes back to Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

's ''Characters'', a work that enjoyed a great vogue in the 17th and 18th centuries and was translated by Jean de La Bruyère. The practice largely died out with advent of 19th-century realism but lasted much longer in genre literature, such as adventure stories, Westerns, and, arguably, science fiction. Nature's Gentleman, whether European-born or exotic, takes his place in this cast of characters, along with the Wise Egyptian, Persian, and Chinaman. "But now, alongside the Good Savage, the Wise Egyptian claims his place." Some of these types are discussed by Paul Hazard in ''The European Mind''.

He had always existed, from the time of the ''Epic of Gilgamesh

The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' () is an epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia, and is regarded as the earliest surviving notable literature and the second oldest religious text, after the Pyramid Texts. The literary history of Gilgamesh begins wit ...

'', where he appears as Enkidu

Enkidu ( sux, ''EN.KI.DU10'') was a legendary figure in Mesopotamian mythology, ancient Mesopotamian mythology, wartime comrade and friend of Gilgamesh, king of Uruk. Their exploits were composed in Sumerian language, Sumerian poems and in t ...

, the wild-but-good man who lives with animals. Another instance is the untutored-but-noble medieval knight, Parsifal

''Parsifal'' ( WWV 111) is an opera or a music drama in three acts by the German composer Richard Wagner and his last composition. Wagner's own libretto for the work is loosely based on the 13th-century Middle High German epic poem '' Parziv ...

. The Biblical shepherd boy David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

falls into this category. The association of virtue with withdrawal from society—and specifically from cities—was a familiar theme in religious literature.

'' Hayy ibn Yaqdhan,'' an Islamic philosophical tale (or thought experiment

A thought experiment is a hypothetical situation in which a hypothesis, theory, or principle is laid out for the purpose of thinking through its consequences.

History

The ancient Greek ''deiknymi'' (), or thought experiment, "was the most anci ...

) by Ibn Tufail

Ibn Ṭufail (full Arabic name: ; Latinized form: ''Abubacer Aben Tofail''; Anglicized form: ''Abubekar'' or ''Abu Jaafar Ebn Tophail''; c. 1105 – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic theo ...

from 12th-century Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality". The ...

, straddles the divide between the religious and the secular. The tale is of interest because it was known to the New England Puritan divine, Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a New England Puritan clergyman and a prolific writer. Educated at Harvard College, in 1685 he joined his father Increase as minister of the Congregationalist Old North Meetin ...

. Translated into English (from Latin) in 1686 and 1708, it tells the story of Hayy, a wild child

Wild child usually refers to a feral child; it may also refer to:

Film and television

*'' The Wild Child'', a 1970 French film directed by François Truffaut

* ''Wild Child'' (film), a 2008 teen comedy starring Emma Roberts

* "Wild Child" (''R ...

, raised by a gazelle, without human contact, on a deserted island in the Indian Ocean. Purely through the use of his reason, Hayy goes through all the gradations of knowledge before emerging into human society, where he revealed to be a believer of natural religion

Natural religion most frequently means the "religion of nature", in which God, the soul, spirits, and all objects of the supernatural are considered as part of nature and not separate from it. Conversely, it is also used in philosophy to describe s ...

, which Cotton Mather, as a Christian Divine, identified with Primitive Christianity. The figure of Hayy is both a Natural man and a Wise Persian, but not a Noble Savage.

The '' locus classicus'' of the 18th-century portrayal of the American Indian are the famous lines from Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

's " Essay on Man" (1734):

To Pope, writing in 1734, the Indian was a purely abstract figure—"poor" either meant ironically, or applied because he was uneducated and a heathen, but also happy because he was living close to Nature. This view reflects the typicalLo, the poor Indian! whose untutor'd mind Sees God in clouds, or hears him in the wind; His soul proud Science never taught to stray Far as the solar walk or milky way; Yet simple Nature to his hope has giv'n, Behind the cloud-topp'd hill, a humbler heav'n; Some safer world in depth of woods embrac'd, Some happier island in the wat'ry waste, Where slaves once more their native land behold, No fiends torment, no Christians thirst for gold! To be, contents his natural desire; He asks no angel's wing, no seraph's fire: But thinks, admitted to that equal sky, His faithful dog shall bear him company.

Age of Reason

The Age of reason, or the Enlightenment, was an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th to 19th centuries.

Age of reason or Age of Reason may also refer to:

* Age of reason (canon law), ...

belief that men are everywhere and in all times the same as well as a Deistic

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin ''deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation of t ...

conception of natural religion (although Pope, like Dryden, was Catholic). Pope's phrase, "Lo the Poor Indian", became almost as famous as Dryden's "noble savage" and, in the 19th century, when more people began to have first hand knowledge of and conflict with the Indians, would be used derisively for similar sarcastic effect.

Attributes of romantic primitivism

In the 1st century AD, sterling qualities such as those enumerated above by Fénelon (excepting perhaps belief in the brotherhood of man) had been attributed byTacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

in his ''Germania

Germania ( ; ), also called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman province of the same name, was a large historical region in north ...

'' to the German barbarians, in pointed contrast to the softened, Romanized Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They s ...

. By inference Tacitus was criticizing his own Roman culture for getting away from its roots—which was the perennial function of such comparisons. Tacitus's Germans did not inhabit a " Golden Age" of ease but were tough and inured to hardship, qualities which he saw as preferable to the decadent softness of civilized life. In antiquity this form of "hard primitivism", whether admired or deplored (both attitudes were common), co-existed in rhetorical opposition to the "soft primitivism" of visions of a lost Golden Age of ease and plenty.

As art historian Erwin Panofsky explains:

In the 18th century the debates about primitivism centered around the examples of the people of Scotland as often as the American Indians. The supposedly rude manners of the Highlanders were often scorned, but their toughness also called forth a degree of admiration among "hard" primitivists, just as that of the Sparta

Sparta (Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referred ...

ns and the Germans had done in antiquity. One Scottish writer described his Highland countrymen this way:

Reaction to Hobbes

Debates about "soft" and "hard" primitivism intensified with the publication in 1651 of Hobbes's ''Leviathan

Leviathan (; he, לִוְיָתָן, ) is a sea serpent noted in theology and mythology. It is referenced in several books of the Hebrew Bible, including Psalms, the Book of Job, the Book of Isaiah, the Book of Amos, and, according to so ...

'' (or ''Commonwealth''), a justification of absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constituti ...

. Hobbes, a "hard Primitivist", flatly asserted that life in a state of nature was "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short"—a "war of all against all":

Reacting to the wars of religion of his own time and the previous century, he maintained that the absolute rule of a king was the only possible alternative to the otherwise inevitable violence and disorder of civil war. Hobbes' hard primitivism may have been as venerable as the tradition of soft primitivism, but his use of it was new. He used it to argue that the state was founded on a social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is a theory or model that originated during the Age of Enlightenment and usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual.

Social ...

in which men voluntarily gave up their liberty in return for the peace and security provided by total surrender to an absolute ruler, whose legitimacy stemmed from the Social Contract and not from God.

Hobbes' vision of the natural depravity of man inspired fervent disagreement among those who opposed absolute government. His most influential and effective opponent in the last decade of the 17th century was Shaftesbury. Shaftesbury countered that, contrary to Hobbes, humans in a state of nature were neither good nor bad, but that they possessed a moral sense based on the emotion of sympathy, and that this emotion was the source and foundation of human goodness and benevolence

Benevolence or Benevolent may refer to:

* Benevolent (band)

* Benevolence (phrenology), a faculty in the discredited theory of phrenology

* "Benevolent" (song), a song by Tory Lanez

* Benevolence (tax), a forced loan imposed by English kings from ...

. Like his contemporaries (all of whom who were educated by reading classical authors such as Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

, and Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ...

), Shaftesbury admired the simplicity of life of classical antiquity. He urged a would-be author "to search for that simplicity of manners, and innocence of behavior, which has been often known among mere savages; ere they were corrupted by our commerce" (''Advice to an Author'', Part III.iii). Shaftesbury's denial of the innate depravity of man was taken up by contemporaries such as the popular Irish essayist Richard Steele (1672–1729), who attributed the corruption of contemporary manners to false education. Influenced by Shaftesbury and his followers, 18th-century readers, particularly in England, were swept up by the cult of sensibility that grew up around Shaftesbury's concepts of sympathy and benevolence.

Meanwhile, in France, where those who criticized government or Church authority could be imprisoned without trial or hope of appeal, primitivism was used primarily as a way to protest the repressive rule of Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ve ...

and XV, while avoiding censorship. Thus, in the beginning of the 18th century, a French travel writer, the Baron de Lahontan

Louis Armand, Baron de Lahontan (9 June 1666 – prior to 1716) served in the French military in Canada where he traveled extensively in the Wisconsin and Minnesota region and the upper Mississippi Valley. Upon his return to Europe he wrote an ...

, who had actually lived among the Huron Indians, put potentially dangerously radical Deist and egalitarian arguments in the mouth of a Canadian Indian, Adario, who was perhaps the most striking and significant figure of the "good" (or "noble") savage, as we understand it now, to make his appearance on the historical stage:

Published in Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former province on the western coast of the Netherlands. From the 10th to the 16th c ...

, Lahontan's writings, with their controversial attacks on established religion and social customs, were immensely popular. Over twenty editions were issued between 1703 and 1741, including editions in French, English, Dutch and German.

Jeremy Jennings

Jeremy Jennings is an English political theorist and Professor of Political Theory at King's College London. He is predominantly interested in the history of political thought, often with specific reference to France. He has authored a number of bo ...

, notes that ''The History of the Two Indies'', in the opinion of Jonathan Israel, was the text that "made a world revolution" by delivering "the most devastating single blow to the existing order":

In the later 18th century, the published voyages of Captain James Cook and Louis Antoine de Bougainville

Louis-Antoine, Comte de Bougainville (, , ; 12 November 1729 – August 1811) was a French admiral and explorer. A contemporary of the British explorer James Cook, he took part in the Seven Years' War in North America and the American Revolut ...

seemed to open a glimpse into an unspoiled Edenic culture that still existed in the un-Christianized South Seas

Today the term South Seas, or South Sea, is used in several contexts. Most commonly it refers to the portion of the Pacific Ocean south of the equator. In 1513, when Spanish conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa coined the term ''Mar del Sur' ...

. Their popularity inspired Diderot's '' Supplement to the Voyage of Bougainville'' (1772), a scathing critique of European sexual hypocrisy and colonial exploitation.

Benjamin Franklin's ''Remarks Concerning the "Savages" of North America''

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a m ...

, who had negotiated with the Native Americans during the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

, protested vehemently against the Paxton massacre, in which white vigilantes massacred Native American women and children at Conestoga, Pennsylvania, in December 1763. Franklin himself personally organized a Quaker militia to control the white population and "strengthen the government". In his pamphlet '' Remarks Concerning the Savages of North America'' (1784), Franklin deplored the use of the term "savages" for Native Americans:

Franklin used the massacres to illustrate his point that no race had a monopoly on virtue, likening the Paxton vigilantes to "Christian White Savages'". Franklin would invoke God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

in the pamphlet, calling for divine punishment of those who carried the Bible in one hand and the hatchet in the other: 'O ye unhappy Perpetrators of this Horrid Wickedness!'" Franklin praised the Indian way of life, their customs of hospitality, their councils, which reached agreement by discussion and consensus, and noted that many white men had voluntarily given up the purported advantages of civilization to live among them, but that the opposite was rare.

Erroneous identification of Rousseau with the noble savage

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revol ...

, like Shaftesbury, also insisted that man was born with the potential for goodness; and he, too, argued that civilization, with its envy and self-consciousness, has made men bad. In his ''Discourse on the Origins of Inequality Among Men'' (1754), Rousseau maintained that man in a State of Nature had been a solitary, ape-like creature, who was not ''méchant'' (bad), as Hobbes had maintained, but (like some other animals) had an "innate repugnance to see others of his kind suffer" (and this natural sympathy constituted the Natural Man's one-and-only natural virtue). It was Rousseau's fellow ''philosophe

The ''philosophes'' () were the intellectuals of the 18th-century Enlightenment.Kishlansky, Mark, ''et al.'' ''A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished Legacy, volume II: Since 1555.'' (5th ed. 2007). Few were primarily philosopher ...

'', Voltaire, objecting to Rousseau's egalitarianism, who charged him with primitivism and accused him of wanting to make people go back and walk on all fours. Because Rousseau was the preferred philosopher of the radical Jacobins of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, he, above all, became tarred with the accusation of promoting the notion of the "noble savage", especially during the polemics about imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power ( economic and ...

and scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism ( racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies can be more ...

in the last half of the 19th century. Yet the phrase "noble savage" does not occur in any of Rousseau's writings. In fact, Rousseau arguably shared Hobbes' pessimistic view of humankind, except that as Rousseau saw it, Hobbes had made the error of assigning it to too early a stage in human evolution. According to the historian of ideas, Arthur O. Lovejoy:

In his ''Discourse on the Origins of Inequality'', Rousseau, anticipating the language of Darwin, states that as the animal-like human species increased there arose a "formidable struggle for existence" between it and other species for food. It was then, under the pressure of necessity, that ''le caractère spécifique de l'espèce humaine''—the specific quality that distinguished man from the beasts—emerged—intelligence, a power, meager at first but yet capable of an "almost unlimited development". Rousseau calls this power the ''faculté de se perfectionner''—perfectibility. Man invented tools, discovered fire, and in short, began to emerge from the state of nature. Yet at this stage, men also began to compare himself to others: "It is easy to see. ... that all our labors are directed upon two objects only, namely, for oneself, the commodities of life, and consideration on the part of others." ''Amour propre''—the desire for consideration (self regard), Rousseau calls a "factitious feeling arising, only in society, which leads a man to think more highly of himself than of any other." This passion began to show itself with the first moment of human self-consciousness, which was also that of the first step of human progress: "It is this desire for reputation, honors, and preferment which devours us all ... this rage to be distinguished, that we own what is best and worst in men—our virtues and our vices, our sciences and our errors, our conquerors and our philosophers—in short, a vast number of evil things and a small number of good." It is this "which inspires men to all the evils which they inflict upon one another." To be sure, Rousseau praises the newly discovered "savage" tribes (whom Rousseau does ''not'' consider in a "state of nature"), as living a life that is simpler and more egalitarian than that of the Europeans; and he sometimes praises this "third stage" it in terms that could be confused with the romantic primitivism fashionable in his times. He also identifies ancient primitive communism under a patriarchy, such as he believes characterized the "youth" of mankind, as perhaps the happiest state and perhaps also illustrative of how man was intended by God to live. But these stages are not all good, but rather are mixtures of good and bad. According to Lovejoy, Rousseau's basic view of human nature after the emergence of social living is basically identical to that of Hobbes. Moreover, Rousseau does not believe that it is possible or desirable to go back to a primitive state. It is only by acting together in civil society and binding themselves to its laws that men become men; and only a properly constituted society and reformed system of education could make men good. According to Lovejoy:

For Rousseau the remedy was not in going back to the primitive but in reorganizing society on the basis of a properly drawn up social compact, so as to "draw from the very evil from which we suffer .e., civilization and progressthe remedy which shall cure it." Lovejoy concludes that Rousseau's doctrine, as expressed in his ''Discourse on Inequality'':

19th-century belief in progress and the fall of the natural man

During the 19th century the idea that men were everywhere and always the same that had characterized both classical antiquity and theEnlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

was exchanged for a more organic and dynamic evolutionary concept of human history. Advances in technology now made the indigenous man and his simpler way of life appear, not only inferior, but also, even his defenders agreed, foredoomed by the inexorable advance of progress

Progress is the movement towards a refined, improved, or otherwise desired state. In the context of progressivism, it refers to the proposition that advancements in technology, science, and social organization have resulted, and by extension w ...

to inevitable extinction. The sentimentalized "primitive" ceased to figure as a moral reproach to the decadence of the effete European, as in previous centuries. Instead, the argument shifted to a discussion of whether his demise should be considered a desirable or regrettable eventuality. As the century progressed, native peoples and their traditions increasingly became a foil serving to highlight the accomplishments of Europe and the expansion of the European Imperial powers, who justified their policies on the basis of a presumed racial and cultural superiority.

Charles Dickens 1853 article on "The Noble Savage" in ''Household Words''

In 1853Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

wrote a scathingly sarcastic review in his weekly magazine '' Household Words'' of painter George Catlin's show of American Indians when it visited England. In his essay, entitle"The Noble Savage"

Dickens expressed repugnance for Indians and their way of life in no uncertain terms, recommending that they ought to be "civilised off the face of the earth". (Dickens's essay refers back to Dryden's well-known use of the term, not to Rousseau.) Dickens's scorn for those unnamed individuals, who, like Catlin, he alleged, misguidedly exalted the so-called "noble savage", was limitless. In reality, Dickens maintained, Indians were dirty, cruel, and constantly fighting among themselves. Dickens's satire on Catlin and others like him who might find something to admire in the American Indians or African bushmen is a notable turning point in the history of the use of the phrase.For an account of Dickens's article see Moore, "Reappraising Dickens's 'Noble Savage'" (2002): 236–243. Like others who would henceforth write about the topic, Dickens begins by disclaiming a belief in the "noble savage": Dickens' essay was arguably a pose of manly, no-nonsense realism and a defense of Christianity. At the end of it his tone becomes more recognizably humanitarian, as he maintains that, although the virtues of the savage are mythical and his way of life inferior and doomed, he still deserves to be treated no differently than Europeans were:

Scapegoating the Inuit: cannibalism and Sir John Franklin's lost expedition

Although Charles Dickens had ridiculed positive depictions of Native Americans as portrayals of so-called "noble" savages, he made an exception (at least initially) in the case of theInuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, ...

, whom he called "loving children of the north", "forever happy with their lot", "whether they are hungry or full", and "gentle loving savages", who, despite a tendency to steal, have a "quiet, amiable character" ("Our Phantom Ship on an Antediluvian Cruise", '' Household Words'', April 16, 1851). However he soon reversed this rosy assessment, when on October 23, 1854, ''The Times'' of London published a report by explorer-physician John Rae of the discovery by the Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, ...

of the remains of the lost Franklin expedition along with evidence of cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b ...

among members of the party:

Franklin's widow, Lady Jane Franklin, and other surviving relatives of the expedition refused to believe Rae's reports that the loss of the expedition was due to an error on the part of the crew; attacking the veracity of Rae's report and more specifically the claims of human cannibalism as reported by the Inuit. An editorial in ''The Times'' called for further investigation:

This line was energetically taken up by Dickens, who wrote in his weekly magazine:

Rae rebutted Dickens in two articles in ''Household Words'': "The Lost Arctic Voyagers", ''Household Words'', No. 248 (December 23, 1854), and "Dr. Rae's Report to the Secretary of the Admiralty", ''Household Words'', No. 249 (December 30, 1854). Though he did not call them noble, Dr. Rae, who had lived among the Inuit, defended them as "dutiful" and "a bright example to the most civilized people", comparing them favorably with the undisciplined crew of the Franklin expedition, whom he suggested were ill-treated and "would have mutinied under privation", and moreover with the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colo ...

in Europe more generally.

Dickens and Wilkie Collins subsequently collaborated on a melodramatic play, '' The Frozen Deep'', about the danger of cannibalism in the far north, in which the villainous role assigned to the Inuit in ''Household Words'' is assumed by a working class Scotswoman.

''The Frozen Deep'' was performed as a benefit organized by Dickens and attended by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

, Prince Albert

Prince Albert most commonly refers to:

*Albert, Prince Consort (1819–1861), consort of Queen Victoria

*Albert II, Prince of Monaco (born 1958), present head of state of Monaco

Prince Albert may also refer to:

Royalty

* Albert I of Belgium ...

, and Emperor Leopold II of Belgium

* german: link=no, Leopold Ludwig Philipp Maria Viktor

, house = Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

, father = Leopold I of Belgium

, mother = Louise of Orléans

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Brussels, Belgium

, death_date ...

, among others, to fund a memorial to the Franklin Expedition. (Rae himself was Scottish).

Rae's respect for the Inuit and his refusal to scapegoat them in the Franklin affair arguably harmed his career. Lady Franklin's campaign to glorify the dead of her husband's expedition, aided and abetted by Dickens, resulted in Rae being shunned by the establishment. Although it was not Franklin but Rae who in 1848 discovered the last link in the much-sought-after Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arct ...

, Rae was never awarded a knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the G ...

hood and died in obscurity in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. (In comparison, fellow Scotsman and contemporary explorer David Livingstone was knighted and buried with full honors in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

.). However, modern historians have confirmed Rae's discovery of the Northwest Passage and the accuracy of his report on cannibalism among Franklin's crew. Canadian author Ken McGoogan, a specialist on Arctic exploration, states that Rae's willingness to learn and adopt the ways of indigenous Arctic peoples made him stand out as the foremost specialist of his time in cold-climate survival and travel. Rae's respect for Inuit customs, traditions, and skills was contrary to the belief of many 19th-century Europeans that native peoples had no valuable technical knowledge or information to impart.

In July 2004, Orkney and Shetland MP Alistair Carmichael introduced into Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. ...

a motion proposing that the House "regrets that Dr Rae was never awarded the public recognition that was his due". In March 2009, Carmichael introduced a further motion urging Parliament to formally state it "regrets that memorials to Sir John Franklin outside the Admiralty headquarters and inside Westminster Abbey still inaccurately describe Franklin as the first to discover the orthwestpassage, and calls on the Ministry of Defence and the Abbey authorities to take the necessary steps to clarify the true position".

Dicken's views toward Indians

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

started to become markedly hostile after the outbreak of the Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the fo ...

:

It was said that Dickens's racism "grew progressively more illiberal over the course of his career". Grace Moore, on the other hand, argues that Dickens, a staunch abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

and anti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic so ...

, had views on racial matters that were a good deal more complex than previous critics have suggested. This event, and the virtually contemporaneous occurrence of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

(1861–1864), which threatened to, and then did, put an end to American slavery, coincided with a polarization of attitudes exemplified by the phenomenon of scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism ( racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies can be more ...

.

Racial theories

In 1860, John Crawfurd and James Hunt linked the "noble savage" concept with developing schools of thought regardingscientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism ( racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies can be more ...

. Crawfurd, in alliance with Hunt, was elected to the presidency of the Ethnological Society of London, which was an offshoot of the Aborigines' Protection Society

The Aborigines' Protection Society (APS) was an international human rights organisation founded in 1837,

...

, founded with the intent to prevent ...

indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

from being enslaved or otherwise exploited. Invoking "science" and "realism", the two men derided their "philanthropic" predecessors for believing in human equality and for not recognizing that mankind was divided into superior and inferior races. Crawfurd, who opposed Darwinian evolution

Darwinism is a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of small, inherited variations that ...

, "denied any unity to mankind, insisting on immutable, hereditary, and timeless differences in racial character, principal amongst which was the 'very great' difference in 'intellectual capacity. For Crawfurd, the races had been created separately and were different species. Both Crawfurd and Hunt supported the theory of polygenism, believing in the plurality of the human species. Crawfurd and Hunt routinely accused those who disagreed with them of believing in "Rousseau's Noble Savage". Ultimately, however, their partnership fell apart due to Hunt giving a speech in 1865 entitled ''On the Negro's place in Nature'', in which he defended the institution of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in the Confederacy

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between ...

during the end of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

; Crawfurd, being an ardent abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

, cut his ties with Hunt after the speech. "As Ter Ellingson demonstrates, Crawfurd was responsible for re-introducing the Pre-Rousseauian concept of 'the Noble Savage' to modern anthropology, attributing it wrongly and quite deliberately to Rousseau." In an otherwise rather lukewarm review of Ellingson's book in ''Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History'' 4:1 (Spring 2003), Frederick E. Hoxie writes:

"If Rousseau was not the inventor of the Noble Savage, who was?" writes Ellingson,

Ellingson finds that any remotely positive portrayal of an indigenous (or working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colo ...

) person is apt to be characterized (out of context) as a supposedly "unrealistic" or "romanticized" "Noble Savage". He points out that Fairchild even includes as an example of a supposed "Noble Savage", a picture of an enslaved Black man on his knees, lamenting his lost freedom. According to Ellingson, Fairchild ends his book with a denunciation of the (always unnamed) believers in primitivism or "The Noble Savage"—who, he feels, are threatening to unleash the dark forces of irrationality on civilization.

Ellingson argues that the term "noble savage", an oxymoron, is a derogatory one, which those who oppose "soft" or romantic primitivism use to discredit (and intimidate) their supposed opponents, whose romantic beliefs they feel are somehow threatening to civilization. Ellingson maintains that virtually none of those accused of believing in the "noble savage" ever actually did so. He likens the practice of accusing anthropologists (and other writers and artists) of belief in the noble savage to a secularized version of the inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

, and he maintains that modern anthropologists have internalized these accusations to the point where they feel they have to begin by ritualistically disavowing any belief in "noble savage" if they wish to attain credibility in their fields. He notes that text books with a painting of a handsome Native American (such as the one by Benjamin West on this page) are even given to school children with the cautionary caption, "A painting of a Noble Savage". West's depiction is characterized as a typical "noble savage" by art historian Vivien Green Fryd, but her interpretation has been contested.

Opponents of primitivism

The most famous modern example of "hard" (or anti-) primitivism in books and movies wasWilliam Golding

Sir William Gerald Golding (19 September 1911 – 19 June 1993) was a British novelist, playwright, and poet. Best known for his debut novel ''Lord of the Flies'' (1954), he published another twelve volumes of fiction in his lifetime. In 1980 ...

's ''Lord of the Flies

''Lord of the Flies'' is a 1954 novel by the Nobel Prize-winning British author William Golding. The plot concerns a group of British boys who are stranded on an uninhabited island and their disastrous attempts to govern themselves. Themes ...

'', published in 1954. The title is said to be a reference to the Biblical devil

A devil is the personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions. It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force. Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conceptions of ...

, Beelzebub (Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

for "Lord of the Flies"). This book, in which a group of school boys stranded on a desert island

A desert island, deserted island, or uninhabited island, is an island, islet or atoll that is not permanently populated by humans. Uninhabited islands are often depicted in films or stories about shipwrecked people, and are also used as stereo ...

revert to savage behavior, was a staple of high school and college required reading lists during the Cold War.

In the 1970s, film director Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick (; July 26, 1928 – March 7, 1999) was an American film director, producer, screenwriter, and photographer. Widely considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, his films, almost all of which are adaptations of nove ...

professed his opposition to primitivism. Like Dickens, he began with a disclaimer:

The opening scene of Kubrick's movie '' 2001: A Space Odyssey'' (1968) depicts prehistoric ape-like men wielding weapons of war, as the tools that supposedly lifted them out of their animal state and made them human.

Another opponent of primitivism is the Australian anthropologist Roger Sandall, who has accused other anthropologists of exalting the "noble savage". A third is archeologist Lawrence H. Keeley, who has criticised a "widespread myth" that "civilized humans have fallen from grace from a simple primeval happiness, a peaceful golden age" by uncovering archeological evidence that he claims demonstrates that violence prevailed in the earliest human societies. Keeley argues that the "noble savage" paradigm has warped anthropological literature to political ends.

Supporters of primitivism

The idea that man is naturally warlike has been challenged, for example in the book ''War, Peace, and Human Nature'' (2013), edited by Douglas P. Fry.See for example The Seville Statement on Violence, released underUNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. I ...

auspices in 1986, specifically rejects any genetic basis to violence or warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between State (polity), states, governments, Society, societies, or paramilitary groups such as Mercenary, mercenaries, Insurgency, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violenc ...

. More modern research and criticism has focused on misinterpretations of fossil evidence, lack of research into other apes, and the political climate of the Cold War.

Anarcho-primitivists

Anarcho-primitivism is an anarchist critique of civilization (anti-civ) that advocates a return to non-civilized ways of life through deindustrialization, abolition of the division of labor or specialization, and abandonment of large-scale orga ...

such as John Zerzan relies heavily on a strong dualism

Dualism most commonly refers to:

* Mind–body dualism, a philosophical view which holds that mental phenomena are, at least in certain respects, not physical phenomena, or that the mind and the body are distinct and separable from one another

** ...

between the "primitive

Primitive may refer to:

Mathematics

* Primitive element (field theory)

* Primitive element (finite field)

* Primitive cell (crystallography)

* Primitive notion, axiomatic systems

* Primitive polynomial (disambiguation), one of two concepts

* Pr ...

"—viewed as non-alienated, wild, non-hierarchical, ludic, and socially egalitarian—and the "civilised

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

Civi ...

"—viewed as alienated, domesticated, hierarchically organised and socially discriminatory. Hence, "life before domestication/agriculture was in fact largely one of leisure, intimacy with nature, sensual wisdom, sexual equality, and health." Zerzan's claims about the status of primitive societies are based on a certain reading of the works of anthropologists such as Marshall Sahlins and Richard B. Lee. Crucially, the category of primitives is restricted to pure hunter-gatherer societies with no domesticated plants or animals. For instance, hierarchy among Northwest Coast Native Americans whose main activities were fishing and foraging is attributed to their having domesticated dogs and tobacco.

In fantasy and science fiction

The "noble savage" often maps to uncorrupted races in science fiction and fantasy genres, often deliberately as a contrast to "fallen" more advanced cultures, in films such as ''Avatar

Avatar (, ; ), is a concept within Hinduism that in Sanskrit literally means "descent". It signifies the material appearance or incarnation of a powerful deity, goddess or spirit on Earth. The relative verb to "alight, to make one's appeara ...

'' and literature including Ghân-buri-Ghân in ''The Lord of the Rings

''The Lord of the Rings'' is an Epic (genre), epic high-fantasy novel by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, intended to be Earth at some time in the distant past, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 c ...

''. Examples of famous noble savage characters in fantasy and science fiction that are well known are Tarzan

Tarzan (John Clayton II, Viscount Greystoke) is a fictional character, an archetypal feral child raised in the African jungle by the Mangani great apes; he later experiences civilization, only to reject it and return to the wild as a heroic adv ...

created by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Conan the Barbarian

Conan the Barbarian (also known as Conan the Cimmerian) is a fictional sword and sorcery hero who originated in pulp magazines and has since been adapted to books, comics, films (including '' Conan the Barbarian'' and '' Conan the Destroyer'') ...

created by Robert E. Howard

Robert Ervin Howard (January 22, 1906June 11, 1936) was an American writer. He wrote pulp fiction in a diverse range of genres. He is well known for his character Conan the Barbarian and is regarded as the father of the sword and sorcery subge ...

, and John from '' Brave New World''. Ka-Zar, Thongor and such are lesser known. Tarzan, Conan, and John are not only known through their literature, but by movie adaptations and other licensed material.

Other movies containing the "noble savage" include:

*'' Little House on the Prairie'' (TV series) (1974–1982)

*'' The Gods Must Be Crazy'' (1980)

*''The Mosquito Coast The Mosquito Coast

The Mosquito Coast, also known as the Mosquitia or Mosquito Shore, historically included the area along the eastern coast of present-day Nicaragua and Honduras. It formed part of the Western Caribbean Zone. It was named afte ...

'' (1986)

*'' Dances with Wolves'' (1990)

*''Pocahontas

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, known as Matoaka, 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman, belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. She was the daughter o ...

'' (1995)

*''The Indian in the Cupboard

''The Indian in the Cupboard'' is a low fantasy children's novel by the British writer Lynne Reid Banks. It was published in 1980 with illustrations by Robin Jacques (UK) and Brock Cole (US). It was later adapted as a 1995 children's film o ...

'' (1995)

*'' Rabbit-Proof Fence'' (2002)

*'' Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron'' (2002)

Noble savage idea today

According to critics like the ''Telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

''s Tim Robey, romantically idealized portrayals of non-industrialized or exotic people persist in popular films, as for example in '' The Lone Ranger'' or '' Dances with Wolves''.

Another contemporary example is the claim in some queer theory sources that the two-spirit

Two-spirit (also two spirit, 2S or, occasionally, twospirited) is a modern, , umbrella term used by some Indigenous North Americans to describe Native people in their communities who fulfill a traditional third-gender (or other gender-varian ...

phenomenon is universal among Indigenous American cultures when, in fact, the cultural views on gender and sexuality in Indigenous American communities vary widely from nation to nation.

See also

* Anarcho-primitivism * Racism in the work of Charles Dickens * ''Essays'' (Montaigne) *Exoticism

Exoticism (from "exotic") is a trend in European art and design, whereby artists became fascinated with ideas and styles from distant regions and drew inspiration from them. This often involved surrounding foreign cultures with mystique and fanta ...

* Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revol ...

* Native Americans in German popular culture

** Native American hobbyism in Germany

* Natural state

* Neotribalism

* Objectification

* Orientalism

* Othering

In phenomenology

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (philosophy), a branch of philosophy which studies subject ...

* Pelagianism

Pelagianism is a Christian theological position that holds that the original sin did not taint human nature and that humans by divine grace have free will to achieve human perfection. Pelagius ( – AD), an ascetic and philosopher from t ...

* Positive stereotype

* State of nature

* Stereotypes about indigenous peoples of North America

* Racial fetishism

Concepts of race and sexuality have interacted in various ways in different historical contexts. While partially based on physical similarities within groups, race is understood by scientists to be a social construct rather than a biological re ...

* Romantic racism

* Virtuous pagan

* Wild child

Wild child usually refers to a feral child; it may also refer to: