Newark Tract on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Newark

Newark most commonly refers to:

* Newark, New Jersey, city in the United States

* Newark Liberty International Airport, New Jersey; a major air hub in the New York metropolitan area

Newark may also refer to:

Places Canada

* Niagara-on-the ...

has long been the largest city

The United Nations uses three definitions for what constitutes a city, as not all cities in all jurisdictions are classified using the same criteria. Cities may be defined as the cities proper, the extent of their urban area, or their metropo ...

in New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

. Founded in 1666, it greatly expanded during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, becoming the commercial and cultural hub of the region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as zones, lands or territories, are areas that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and the interaction of humanity and t ...

. Its population grew with various waves of migration in the mid 19th century, peaking in 1950. It suffered greatly during the era of urban decline and suburbanization in the late 20th century. Since the millennium

A millennium (plural millennia or millenniums) is a period of one thousand years, sometimes called a kiloannum (ka), or kiloyear (ky). Normally, the word is used specifically for periods of a thousand years that begin at the starting point (ini ...

it has benefited from interest and re-investment in America's cities, recording population growth in the 2010 and 2020 censuses.

Founding and 18th century

Newark was founded in 1666 byConnecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

s led by Robert Treat

Robert Treat (February 23, 1624July 12, 1710) was a New England Puritan colonial leader, militia officer and governor of the Connecticut Colony between 1683 and 1698. In 1666 he helped found Newark, New Jersey.

Biography

Treat was born in Pitm ...

from the New Haven Colony

The New Haven Colony was a small English colony in North America from 1638 to 1664 primarily in parts of what is now the state of Connecticut, but also with outposts in modern-day New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware.

The history o ...

to avoid losing political power to others not of their own church after the union of the Connecticut and New Haven colonies. It was the third settlement founded in New Jersey, after Bergen, New Netherland

Bergen was a part of the 17th century province of New Netherland, in the area in northeastern New Jersey along the Hudson and Hackensack Rivers that would become contemporary Hudson and Bergen Counties. Though it only officially existed as an ind ...

(later dissolved into Hudson County

Hudson County is the most densely populated county in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It lies west of the lower Hudson River, which was named for Henry Hudson, the sea captain who explored the area in 1609. Part of New Jersey's Gateway Region in ...

, then incorporated into Jersey City

Jersey City is the second-most populous city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, after Newark.Elizabethtown (modern-day

The life and correspondence of James McHenry

'(Cleveland: Burrows Brothers Co., 1907) Treat and the party bought the property on the Passaic River from the

Newark was bustling in the early-to-mid-20th century. Market and Broad Streets served as a center of retail commerce for the region, anchored by four flourishing department stores: Hahne & Company,

Newark was bustling in the early-to-mid-20th century. Market and Broad Streets served as a center of retail commerce for the region, anchored by four flourishing department stores: Hahne & Company,  In 1922, Newark had 63 live theaters, 46 movie theaters, and an active nightlife.

In 1922, Newark had 63 live theaters, 46 movie theaters, and an active nightlife.

Problems existed underneath the industrial hum. In 1930, a city commissioner told the Optimists, a local booster club:

While many observers attributed Newark's decline to post-

Problems existed underneath the industrial hum. In 1930, a city commissioner told the Optimists, a local booster club:

While many observers attributed Newark's decline to post-

The

The

Newark History Society

from History of the City of Newark New Jersey, Embracing Two and Half Centuries 1666–1913; Vol. II, Lewis Historical Publishing Co.; New York-Chicago; 1913

NJ Historical Society Map of Newark 1668How Newark Became Newark

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Newark, New Jersey

Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

).

They sought to establish a colony with strict church rules similar to the one they had established in Milford, Connecticut

Milford is a coastal city in New Haven County, Connecticut, United States, located between New Haven and Bridgeport. The population was 50,558 at the 2020 United States Census. The city includes the village of Devon and the borough of Woodmont. ...

. Treat wanted to name the community "Milford." Another settler, Abraham Pierson

Abraham Pierson (1646 – March 5, 1707) was an American Congregational minister who served as the first rector, from 1701 to 1707, and one of the founders of the Collegiate School — which later became Yale University.

Biography

He was ...

, had previously been a preacher in England's Newark-on-Trent

Newark-on-Trent or Newark () is a market town and civil parish in the Newark and Sherwood district in Nottinghamshire, England. It is on the River Trent, and was historically a major inland port. The A1 road (Great Britain), A1 road bypasses th ...

, and adopted the name; he is also quoted as saying that the community reflecting the new task at hand should be named "New Ark" for "New Ark of the Covenant

The Ark of the Covenant,; Ge'ez: also known as the Ark of the Testimony or the Ark of God, is an alleged artifact believed to be the most sacred relic of the Israelites, which is described as a wooden chest, covered in pure gold, with an e ...

." The name was shortened to Newark. References to the name "New Ark" are found in preserved letters written by historical figures such as James McHenry dated as late as 1787.Bernard C. Steiner and James McHenry, The life and correspondence of James McHenry

'(Cleveland: Burrows Brothers Co., 1907) Treat and the party bought the property on the Passaic River from the

Hackensack Indians

Hackensack was the exonym given by the Dutch colonists to a band of the Lenape, or ''Lenni-Lenape'' ("original men"), a Native American tribe. The name is a Dutch derivation of the Lenape word for what is now the region of northeastern New Jers ...

by exchanging gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). ...

, 100 bars of lead, 20 axes, 20 coats, guns, pistols, swords, kettles, blankets, knives, beer, and ten pairs of breeches.

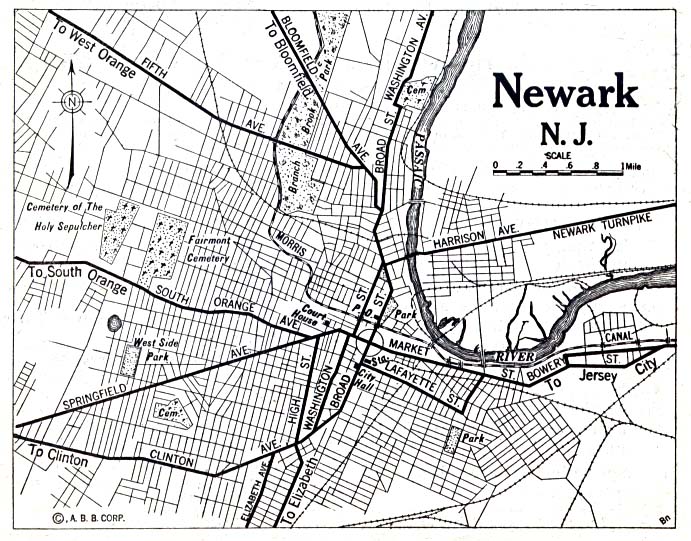

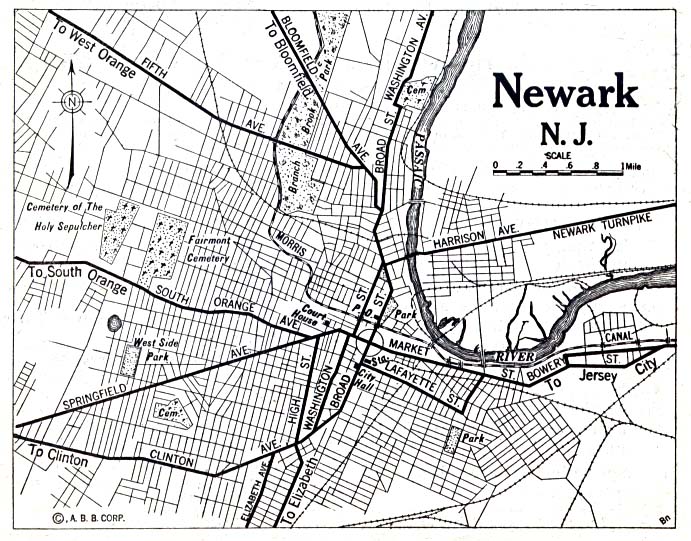

The first four settlers built houses at what is now the intersection of Broad Street and Market Street, also known as "Four Corners."

The total control of the community by the Puritan Church continued until 1733 when Josiah Ogden harvested wheat on a Sunday following a lengthy rainstorm and was disciplined by the Church for Sabbath breaking

Sabbath desecration is the failure to observe the Biblical Sabbath and is usually considered a sin and a breach of a holy day in relation to either the Jewish ''Shabbat'' (Friday sunset to Saturday nightfall), the Sabbath in seventh-day churc ...

. He left the church and corresponded with Episcopalian

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the l ...

missionaries, who arrived to build a church in 1746 and broke up the Puritan theocracy

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deity, deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy origina ...

.

It took 70 years to eliminate the last vestiges of theocracy from Newark, when the right to hold office was finally granted to non-Protestants.

''First Landing Party of the Founders of Newark

''First Landing Party of the Founders of Newark'' is a marble monument with bas-relief and inscription by sculptor Gutzon Borglum (1867–1941) near the New Jersey Performing Arts Center in Newark, New Jersey. It was dedicated in 1916. It was lis ...

'' (1916) and ''Indian and the Puritan

''Indian and the Puritan'' is a 1916 marble and bronze monument by Gutzon Borglum, the sculptor of Mount Rushmore, opposite 5 Washington Street, the Newark Public Library, in Washington Park of Newark in Essex County, New Jersey. It was added ...

'' (1916) are two of four public art

Public art is art in any Media (arts), media whose form, function and meaning are created for the general public through a public process. It is a specific art genre with its own professional and critical discourse. Public art is visually and phy ...

works created by Gutzon Borglum

John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum (March 25, 1867 – March 6, 1941) was an American sculptor best known for his work on Mount Rushmore. He is also associated with various other public works of art across the U.S., including Stone Mountain in Geo ...

that are located in Newark commemorating the city's founding. They were added to the New Jersey Register of Historic Places

The New Jersey Register of Historic Places is the official list of historic resources of local, state, and national interest in the U.S. state of New Jersey. The program is administered by the New Jersey's state historic preservation office with ...

on September 13, 1994, and the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

on October 28, 1994 as part of a Multiple Property Submission

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of Historic districts in the United States, districts, sites, buildings, struc ...

, "The Public Sculpture of John de la Mothe Gutzon Borglum, 1911–1926".

Industrial era to 1900

Newark's rapid growth began in the early 19th century, much of it due to aMassachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

transplant named Seth Boyden

Seth Boyden (November 17, 1788 – March 31, 1870) was an American inventor.

Early life

He was born in Foxboro, Massachusetts, on November 17, 1788, the son of Seth Boyden and Susannah Atherton. His father was a farmer and blacksmith. His yo ...

. Boyden came to Newark in 1815, and immediately began a torrent of improvements to leather manufacture, culminating in the process for making patent leather

Patent leather is a type of coated leather that has a high-gloss finish. The coating process was introduced to the United States and improved by inventor Seth Boyden, of Newark, New Jersey, in 1818, with commercial manufacture beginning Septe ...

. Boyden's genius led to Newark's manufacturing nearly 90% of the nation's leather by 1870, bringing in $8.6 million in revenue to the city in that year alone. In 1824, Boyden, bored with leather, found a way to produce malleable iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in f ...

. Newark also prospered by the construction of the Morris Canal

The Morris Canal (1829–1924) was a common carrier anthracite coal canal across northern New Jersey that connected the two industrial canals at Easton, Pennsylvania across the Delaware River from its western terminus at Phillipsburg, New Jers ...

in 1831. The canal connected Newark with the New Jersey hinterland, at that time a major iron and farm area.

Railroads arrived in 1834 and 1835. A flourishing shipping business resulted, and Newark became the area's industrial center. By 1826, Newark's population stood at 8,017, ten times the 1776 number.

The middle 19th century saw continued growth and diversification of Newark's industrial base. The first commercially successful plastic

Plastics are a wide range of synthetic or semi-synthetic materials that use polymers as a main ingredient. Their plasticity makes it possible for plastics to be moulded, extruded or pressed into solid objects of various shapes. This adaptab ...

— Celluloid

Celluloids are a class of materials produced by mixing nitrocellulose and camphor, often with added dyes and other agents. Once much more common for its use as photographic film before the advent of safer methods, celluloid's common contemporar ...

— was produced in a factory on Mechanic Street by John Wesley Hyatt

John Wesley Hyatt (November 28, 1837 – May 10, 1920) was an American inventor. He is mainly known for simplifying the production of celluloid.

Hyatt, a Perkin Medal recipient, is included in the National Inventors Hall of Fame. He had nearly 2 ...

. Hyatt's Celluloid found its way into Newark-made carriages, billiard balls

A billiard ball is a small, hard ball used in cue sports, such as carom billiards, pool, and snooker. The number, type, diameter, color, and pattern of the balls differ depending upon the specific game being played. Various particular ball pro ...

, and dentures

Dentures (also known as false teeth) are prosthetic devices constructed to replace missing teeth, and are supported by the surrounding soft and hard tissues of the oral cavity. Conventional dentures are removable ( removable partial denture o ...

. Dr. Edward Weston perfected a process for zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodi ...

electroplating

Electroplating, also known as electrochemical deposition or electrodeposition, is a process for producing a metal coating on a solid substrate through the reduction of cations of that metal by means of a direct electric current. The part to be ...

, as well as a superior arc lamp in Newark. Newark's Military Park had the first public electric lamps anywhere in the United States. Before moving to Menlo Park, Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventio ...

himself made Newark home in the early 1870s. He invented the stock ticker in the Brick City.

In the late 19th century, Newark's industry was further developed, especially through the efforts of such men as J. W. Hyatt. From the mid-century on, numerous Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

and German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

immigrants moved to the city. The Germans were primarily refugees from the revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

, and, as other groups later did, established their own ethnic enterprises, such as newspapers and breweries. However, tensions existed between the "native stock" and the newer groups.

In the middle 19th century, Newark added insurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...

to its repertoire of businesses; Mutual Benefit was founded in the city in 1845 and Prudential in 1873. Prudential, or "the Pru" as generations knew it, was founded by another transplanted New Englander, John Fairfield Dryden. He found a niche catering to the middle and lower classes. In the late 1880s, companies based in Newark sold more insurance than those in any city except Hartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since the ...

.

In 1880, Newark's population stood at 136,500 in 1890 at 181,830; in 1900 at 246,070; and in 1910 at 347,000, a jump of 200,000 in three decades. As Newark's population approached a half million in the 1920s, the city's potential seemed limitless. It was said in 1927: "Great is Newark's vitality. It is the red blood in its veins – this basic strength that is going to carry it over whatever hurdles it may encounter, enable it to recover from whatever losses it may suffer and battle its way to still higher achievement industrially and financially, making it eventually perhaps the greatest industrial center in the world".

Sanitary conditions were bad throughout urban America in the 19th century, but Newark had an especially bad reputation because of the accumulation of human and horse waste built up on the city streets, its inadequate sewage systems, and the dubious quality of its water supply.

1900-1945

Newark was bustling in the early-to-mid-20th century. Market and Broad Streets served as a center of retail commerce for the region, anchored by four flourishing department stores: Hahne & Company,

Newark was bustling in the early-to-mid-20th century. Market and Broad Streets served as a center of retail commerce for the region, anchored by four flourishing department stores: Hahne & Company, Bambergers

Bamberger's was a department store chain with branches primarily in New Jersey and other locations in Delaware, Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania. The chain was headquartered in Newark, New Jersey.

History 1892–1912

Newark was known for ma ...

and Company, S. Klein

S. Klein On The Square, or simply S. Klein, was a popular-priced department store chain based in New York City. The flagship stores (a main building and a women's fashion building) were located along Union Square East in Manhattan; this lo ...

and Kresge-Newark

Kresge-Newark was an upper-middle market department store based in Newark, New Jersey. The firm was started in 1923 when its founder Sebastian Kresge purchased the L.S. Plaut Department store "S. S. Kresge Enters New Enterprise— Twenty-five ...

. "Broad Street today is the Mecca of visitors as it has been through all its long history," Newark merchants boasted, "they come in hundreds of thousands now when once they came in hundreds."

In 1922, Newark had 63 live theaters, 46 movie theaters, and an active nightlife.

In 1922, Newark had 63 live theaters, 46 movie theaters, and an active nightlife. Dutch Schultz

Dutch Schultz (born Arthur Simon Flegenheimer; August 6, 1901October 24, 1935) was an American mobster. Based in New York City in the 1920s and 1930s, he made his fortune in organized crime-related activities, including bootlegging and the nu ...

was killed in 1935 at the local Palace Bar. Billie Holiday

Billie Holiday (born Eleanora Fagan; April 7, 1915 – July 17, 1959) was an American jazz and swing music singer. Nicknamed "Lady Day" by her friend and music partner, Lester Young, Holiday had an innovative influence on jazz music and pop si ...

frequently stayed at the Coleman Hotel. By some measures, the intersection of Broad and Market Streets — known as the "Four Corners

The Four Corners is a region of the Southwestern United States consisting of the southwestern corner of Colorado, southeastern corner of Utah, northeastern corner of Arizona, and northwestern corner of New Mexico. The Four Corners area ...

" — was the busiest intersection in the United States. In 1915, Public Service counted over 280,000 pedestrian crossings in one 13-hour period. Eleven years later, on October 26, 1926, a State Motor Vehicle Department check at the Four Corners counted 2,644 trolleys, 4,098 buses, 2657 taxis, 3474 commercial vehicles, and 23,571 automobiles. Traffic in Newark was so heavy that the city converted the old bed of the Morris Canal

The Morris Canal (1829–1924) was a common carrier anthracite coal canal across northern New Jersey that connected the two industrial canals at Easton, Pennsylvania across the Delaware River from its western terminus at Phillipsburg, New Jers ...

into the Newark City Subway

The Newark Light Rail (NLR) is a light rail system serving Newark, New Jersey and surrounding areas, operated by New Jersey Transit Bus Operations. The service consists of two segments, the original Newark City Subway (NCS), and the extension t ...

, making Newark one of the few cities in the country to have an underground system. Essex County was the first county park system in the country.

New skyscrapers were being built every year, the two tallest in the city being the Art Deco

Art Deco, short for the French ''Arts Décoratifs'', and sometimes just called Deco, is a style of visual arts, architecture, and product design, that first appeared in France in the 1910s (just before World War I), and flourished in the Unite ...

National Newark Building

The National Newark Building (Formerly the National Newark and Essex Bank Building) is a neo-classical office skyscraper in Newark, New Jersey. It has been the tallest building in Newark since 1931 and was tallest in New Jersey until 1989. At th ...

and the Lefcourt-Newark Building. In 1948, just after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Newark hit its peak population of just under 450,000. The population also grew as immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe settled there. Newark was the center of distinctive neighborhoods, including a large Eastern European Jewish community concentrated along Prince Street. In 1959 German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe designed an apartment complex across from Branchbrook Park.

Post-World War II era

Problems existed underneath the industrial hum. In 1930, a city commissioner told the Optimists, a local booster club:

While many observers attributed Newark's decline to post-

Problems existed underneath the industrial hum. In 1930, a city commissioner told the Optimists, a local booster club:

While many observers attributed Newark's decline to post-World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

phenomena, others point to an earlier decline in the city budget as an indicator of problems. It fell from $58 million in 1938 to only $45 million in 1944. This was a slow recovery from the Great Depression. The buildup to World War II was causing an increase in the nation's economy. The city increased its tax rate from $4.61 to $5.30.

Some attribute Newark's downfall to its propensity for building large housing projects. Newark's housing had long been a matter of concern, as much of it was older. A 1944 city-commissioned study showed that 31 percent of all Newark dwelling units were below standards of health, and only 17 percent of Newark's units were owner-occupied. Vast sections of Newark consisted of wooden tenements, and at least 5,000 units failed to meet thresholds of being a decent place to live. Bad housing was the cause of demands that government intervene in the housing market to improve conditions.

Historian Kenneth T. Jackson and others theorized that Newark, with a poor center surrounded by middle-class outlying areas, only did well when it was able to annex middle-class suburbs. When municipal annexation broke down, urban problems were exacerbated as the middle-class ring became divorced from the poor center. In 1900, Newark's mayor had confidently speculated, "East Orange

East Orange is a city in Essex County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 69,612. The city was the state's 20th most-populous municipality in 2010, after having been the state's 14th most-po ...

, Vailsburg, Harrison

Harrison may refer to:

People

* Harrison (name)

* Harrison family of Virginia, United States

Places

In Australia:

* Harrison, Australian Capital Territory, suburb in the Canberra district of Gungahlin

In Canada:

* Inukjuak, Quebec, or " ...

, Kearny, and Belleville would be desirable acquisitions. By an exercise of discretion we can enlarge the city from decade to decade without unnecessarily taxing the property within our limits, which has already paid the cost of public improvements." Only Vailsburg would ever be added.

Although numerous problems predated World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Newark was more hamstrung by a number of trends in the post-WWII era. The Federal Housing Administration

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), also known as the Office of Housing within the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), is a United States government agency founded by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, created in part ...

redlined virtually all of Newark, preferring to back up mortgages in the white suburbs. This made it impossible for people to get mortgages for purchase or loans for improvements. Manufacturers set up in lower wage environments outside the city and received larger tax deductions for building new factories in outlying areas than for rehabilitating old factories in the city. The federal tax structure essentially subsidized such inequities.

Billed as transportation improvements, construction of new highways: Interstate 280, the New Jersey Turnpike

The New Jersey Turnpike (NJTP) is a system of controlled-access highways in the U.S. state of New Jersey. The turnpike is maintained by the New Jersey Turnpike Authority (NJTA).The Garden State Parkway, although maintained by NJTA, is not consi ...

, and Interstate 78

Interstate 78 (I-78) is an east–west Interstate Highway in the Northeastern United States, running from I-81 northeast of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, through Allentown to western and northern New Jersey and terminating at the Holland T ...

harmed Newark. They directly hurt the city by dividing the fabric of neighborhoods and displacing many residents. The highways indirectly hurt the city because the new infrastructure made it easier for middle-class workers to live in the suburbs and commute into the city.

Despite its problems, Newark tried to remain vital in the postwar era. The city successfully persuaded Prudential and Mutual Benefit to stay and build new offices. Rutgers University-Newark

Rutgers University (; RU), officially Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, is a public land-grant research university consisting of four campuses in New Jersey. Chartered in 1766, Rutgers was originally called Queen's College, and was a ...

, New Jersey Institute of Technology

{{Infobox university

, name = {{nowrap, New Jersey Institute of Technology

, image = New Jersey IT seal.svg

, image_upright = 0.9

, former_names = Newark College of Engineering (1930–1975)Ne ...

, and Seton Hall University

Seton Hall University (SHU) is a private Catholic research university in South Orange, New Jersey. Founded in 1856 by then-Bishop James Roosevelt Bayley and named after his aunt, Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton, Seton Hall is the oldest diocesan un ...

expanded their Newark presences, with the former building a brand-new campus on a 23-acre (9 hectare) urban renewal site. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, PANYNJ; stylized, in logo since 2020, as Port Authority NY NJ, is a joint venture between the U.S. states of New York and New Jersey, established in 1921 through an interstate compact authorized ...

made Port Newark

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ha ...

the first container port in the nation. South of the city, during the postwar era, it took over operations at Newark Liberty International Airport

Newark Liberty International Airport , originally Newark Metropolitan Airport and later Newark International Airport, is an international airport straddling the boundary between the cities of Newark in Essex County and Elizabeth in Union Count ...

, now the thirteenth busiest airport in the United States.

The city made serious mistakes with public housing

Public housing is a form of housing tenure in which the property is usually owned by a government authority, either central or local. Although the common goal of public housing is to provide affordable housing, the details, terminology, def ...

and urban renewal

Urban renewal (also called urban regeneration in the United Kingdom and urban redevelopment in the United States) is a program of land redevelopment often used to address urban decay in cities. Urban renewal involves the clearing out of blighte ...

, although these were not the sole causes of Newark's tragedy. Across several administrations, the city leaders of Newark considered the federal government's offer to pay for 100% of the costs of housing projects as a blessing. The decline in industrial jobs meant that more poor people needed housing, whereas in prewar years, public housing was for working-class families. While other cities were skeptical about putting so many poor families together and were cautious in building housing projects, Newark pursued federal funds. Eventually, Newark had a higher percentage of its residents in public housing than any other American city.

The largely Italian-American

Italian Americans ( it, italoamericani or ''italo-americani'', ) are Americans who have full or partial Italian ancestry. The largest concentrations of Italian Americans are in the urban Northeast and industrial Midwestern metropolitan areas, w ...

First Ward was one of the hardest hit by urban renewal. A 46-acre (19 hectare) housing tract, labeled a slum because it had dense older housing, was torn down for multi-story, multi-racial Le Corbusier

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (6 October 188727 August 1965), known as Le Corbusier ( , , ), was a Swiss-French architect, designer, painter, urban planner, writer, and one of the pioneers of what is now regarded as modern architecture. He was ...

-style high rises, named the Christopher Columbus Homes. The tract had contained 8th Avenue, the commercial heart of the neighborhood. Fifteen small-scale blocks were combined into three "superblocks". The Columbus Homes, never in harmony with the rest of the neighborhood, were vacated in the 1980s. They were finally torn down in 1994. The Pavilion and Colonnade Apartments

The Pavilion and Colonnade Apartments are three highrise apartment buildings in Newark, New Jersey. The Pavilion Apartments are located at 108-136 Martin Luther King Junior Blvd. and the Colonnade Apartments at 25-51 Clifton Avenue in the overlap ...

, built for middle-class families remain.

From 1950 to 1960, while Newark's overall population dropped from 438,000 to 408,000, it gained 65,000 non-whites. By 1966, Newark had a black majority, a faster turnover than most other northern cities had experienced. Evaluating the riots of 1967, Newark educator Nathan Wright, Jr. said, "No typical American city has as yet experienced such a precipitous change from a white to a black majority." The misfortune of the Great Migration and Puerto Rican migration was that Southern blacks and Puerto Ricans were moving to Newark to be industrial workers just as the industrial jobs were decreasing sharply. Many suffered the culture shock of leaving a rural area for an urban industrial job base and environment. The latest migrants to Newark left poverty in the South to find poverty in the North.

During the 1950s alone, Newark's white population decreased by more than 25 percent from 363,000 to 266,000. From 1960 to 1967, its white population fell further to 46,000. Although in-migration of new ethnic groups combined with white flight markedly affected the demographics of Newark, the racial composition of city workers did not change as rapidly. In addition, the political and economic power in the city remained based in the white population.

In 1967, out of a police force

The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state, with the aim to enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder. Their lawful powers include arrest and th ...

of 1,400, only 150 members were black, mostly in subordinate positions. Racial tensions arose because of the disproportion between residents and police demographics. Since Newark's blacks lived in neighborhoods that had been white only two decades earlier, nearly all of their apartments and stores were white-owned as well. The loss of jobs affected overall income in the city, and many owners cut back on maintenance of buildings, contributing to a cycle of deterioration in housing stock.

Without consulting any residents of the neighborhood to be affected, Mayor Addonizio offered to condemn and raze 150 acres (61 hectares) of a densely populated black neighborhood in the central ward for the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey

The University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ) was a state-run health sciences institution of New Jersey, United States.

It was founded as the Seton Hall College of Medicine and Dentistry in 1954, and by the 1980s was both a majo ...

(UMDNJ). UMDNJ had wanted to settle in suburban Madison Madison may refer to:

People

* Madison (name), a given name and a surname

* James Madison (1751–1836), fourth president of the United States

Place names

* Madison, Wisconsin, the state capital of Wisconsin and the largest city known by this ...

, NJ.

1967 Newark riots

On July 12, 1967, a taxi driver named John Smith was violently injured while respectfully accepting arrest. A crowd gathered outside the police station where Smith was detained. Due to miscommunication, the crowd believed Smith had died in custody, although he had been transported to a hospital via a back entrance to the station. This sparked scuffles between African Americans and police in the Fourth Ward, although the damage toll was only $2,500. Subsequent to television news broadcasts on July 13 however, new and larger riots took place. Twenty-six people were killed; 1,500 wounded; 1,600 arrested; and $10 million in property was destroyed. More than a thousand businesses were torched or looted, including 167 groceries (most of which would never reopen). Newark's reputation suffered dramatically. It was said, "wherever American cities are going, Newark will get there first." The long and short term causes of the riots are explored in depth in the documentary film ''Revolution '67

''Revolution '67'' is a 2007 documentary film about the black riots of the 1960s. With the philosophy of nonviolence giving way to the Black Power Movement, race riots were breaking out in Jersey City, Harlem, and Watts, Los Angeles. In 1967, b ...

''.

After the riots

The 1970s and 1980s brought continued decline. Middle class residents of all races continued to flee the city. Certain pockets of the city developed as domains of poverty and social isolation. Some say that whenever the media of New York needed to find some example of urban despair, they traveled to Newark. In '' American Pastoral'', the 1997 novel by Newark-born authorPhilip Roth

Philip Milton Roth (March 19, 1933 – May 22, 2018) was an American novelist and short story writer.

Roth's fiction—often set in his birthplace of Newark, New Jersey—is known for its intensely autobiographical character, for philosophicall ...

, the protagonist Swede Levov says:

In January 1975, an article in ''Harper's Magazine

''Harper's Magazine'' is a monthly magazine of literature, politics, culture, finance, and the arts. Launched in New York City in June 1850, it is the oldest continuously published monthly magazine in the U.S. (''Scientific American'' is older, b ...

'' ranked the 50 largest American cities in 24 categories, ranging from park space to crime. Newark was one of the five worst in 19 out of 24 categories, and the very worst in nine. According to the article, only 70 percent of residents owned a telephone. St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, the city ranked second worst, was much farther from Newark than the cities in the top five were from each other. The article concluded:

Newark has had several achievements in the two and a half decades since the riots. In 1968, the New Community Corporation

New Community Corporation (NCC) is a not-for-profit community development corporation based in Newark, New Jersey. NCC focuses on community organizing, provision of a variety of community-enhancing services, and resident participation in agency o ...

was founded. It has become one of the most successful community development corporation

A community development corporation (CDC) is a not-for-profit organization incorporated to provide programs, offer services and engage in other activities that promote and support community development. CDCs usually serve a geographic location su ...

s in the nation. By 1987, the NCC owned and managed 2,265 low-income housing units.

Newark's downtown began to redevelop in the post-riot decades. Less than two weeks after the riots, Prudential announced plans to underwrite a $24 million office complex near Penn Station Pennsylvania Station is a name applied by the Pennsylvania Railroad to several of its grand passenger terminals.

Pennsylvania Station or Penn Station may also refer to

Current train stations

* Baltimore Penn Station

* Pennsylvania Station (Cinc ...

, dubbed " Gateway." Today, Gateway houses thousands of white-collar workers, though few live in Newark.

Before the riots, the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey

The University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ) was a state-run health sciences institution of New Jersey, United States.

It was founded as the Seton Hall College of Medicine and Dentistry in 1954, and by the 1980s was both a majo ...

was considering building in the suburbs. The riots and Newark's undeniable desperation kept the medical school in the city. However, instead of being built on 167 acres (676,000 m²), the medical school was built on just , part of which was already city owned. Students at the medical school soon started the "Student Family Health Clinic" to provide free health care for the underserved population, along with other community service projects. It continues to operate today as one of the nation's oldest student-run free health clinics.

In 1970, Kenneth A. Gibson was the first African-American to be elected mayor of Newark, as well as to be elected mayor of a major northeastern city. The 1970s were a time of battles between Gibson and the shrinking white population. Gibson admitted that "Newark may be the most decayed and financially crippled city in the nation." He and the city council raised taxes to try to improve services such as schools and sanitation, but they did nothing for Newark's economic base. The CEO of Ballantine's Brewery asserted that Newark's $1 million annual tax bill was the cause of the company's bankruptcy.

Prior to the election of former mayor Cory Booker

Cory Anthony Booker (born April 27, 1969) is an American politician and attorney who has served as the junior United States senator from New Jersey since 2013. A member of the Democratic Party, Booker is the first African-American U.S. se ...

in 2006, Newark did not have a formal city planning department. As a result, a fellow at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research

The Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (renamed in 1981 from the International Center for Economic Policy Studies) is a conservative American think tank focused on domestic policy and urban affairs, established in Manhattan in 1978 by Anto ...

concluded:

Newark's Renaissance

Downtown

The

The New Jersey Performing Arts Center

The New Jersey Performing Arts Center (NJPAC), in downtown Newark, New Jersey, United States, is one of the largest performing arts centers in the United States. Home to the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra (NJSO), more than nine million visitors ( ...

, which opened in the downtown area in 1997 at a cost of $180 million, was seen by many as the first step in the city's road to revival, and brought in people to Newark who otherwise might never have visited. NJPAC is known for its acoustics, and features the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra

The New Jersey Symphony, formerly the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra, is an American symphony orchestra based in the state of New Jersey. The New Jersey Symphony is the state orchestra of New Jersey, performing classical subscription concert serie ...

as its resident orchestra. NJPAC also presents a diverse group of visiting artists such as Itzhak Perlman, Sarah Brightman, Sting, 'N Sync, Lauryn Hill

Lauryn Noelle Hill (born May 26, 1975) is an American singer, songwriter, rapper, and record producer. She is often regarded as one of the greatest rappers of all time, as well as being one of the most influential musicians of her generation. ...

, the Vienna Boys' Choir

The Vienna Boys' Choir (german: Wiener Sängerknaben) is a choir of boy sopranos and altos based in Vienna, Austria. It is one of the best known boys' choirs in the world. The boys are selected mainly from Austria, but also from many other count ...

, Yo Yo Ma

Yo-Yo Ma ('' Chinese'': 馬友友 ''Ma Yo Yo''; born October 7, 1955) is an American cellist. Born in Paris to Chinese parents and educated in New York City, he was a child prodigy, performing from the age of four and a half. He graduated from ...

, the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra

The Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra ( nl, Koninklijk Concertgebouworkest, ) is a Dutch symphony orchestra, based at the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw (concert hall). Considered one of the world's leading orchestras, Queen Beatrix conferred the " ...

of Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

, and the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT) is a modern dance company based in New York City. It was founded in 1958 by choreographer and dancer Alvin Ailey. It is made up of 32 dancers, led by artistic director Robert Battle and associate a ...

.

Since then, the city built a now demolished baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding tea ...

stadium (Riverfront Stadium

Riverfront Stadium, also known as Cinergy Field from 1996 to 2002, was a multi-purpose stadium in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States that was the home of the Cincinnati Reds of Major League Baseball from 1970 Major League Baseball season, 1970 throug ...

) for the Newark Bears

The Newark Bears were an American minor league professional baseball team based in Newark, New Jersey. They were a member of the Atlantic League of Professional Baseball and, later, the Canadian American Association of Professional Baseball. T ...

, the city's former minor league team. In 2007, the Prudential Center

Prudential Center is a multi-purpose indoor arena in the central business district of Newark, New Jersey. Opened in 2007, it is the home of the New Jersey Devils of the National Hockey League (NHL) and the men's basketball program of Seton Hal ...

(nicknamed, "The Rock") opened for the New Jersey Devils

The New Jersey Devils are a professional sports, professional ice hockey team based in Newark, New Jersey. The Devils compete in the National Hockey League (NHL) as a member of the Metropolitan Division in the Eastern Conference (NHL), Eastern ...

. The Newark Public Library

The Newark Public Library (NPL) is a public library system in Newark, New Jersey. The library system offers numerous programs and events to its diverse population. With eight different locations, the Newark Public Library serves as a Statewide Re ...

is planning a major renovation and expansion. The Port Authority constructed a rail connection to the airport ( AirTrain Newark). Numerous commercial developments have arisen in the downtown area. Two public spaces have opened, Mulberry Commons

Mulberry Commons is a public park in Newark, New Jersey. It was first proposed in 2005 to be the centerpiece of of the city's Downtown surrounded by Gateway Center, Newark Penn Station, Government Center and Prudential Center, a 19,000 se ...

and Newark Riverfront Park

Newark Riverfront Park is a park and promenade being developed in phases along the Passaic River in Newark, New Jersey, United States. The park, expected to be long and encompass , is being created from brownfield sites along the river, which it ...

, the latter along Passaic River waterfront is being refurbished through downtown to provide citizens with access to the river.

While much of the city's revitalization efforts have been focused in the downtown area, adjoining neighborhoods have in recent years begun to see some signs of development, particularly in the Central Ward. Since 2000, Newark has gained population, its first increase since the 1940s. Nevertheless, the "Renaissance" has been unevenly felt across the city and some districts continue to have below-average household incomes and higher-than-average rates of poverty.

By the mid-first decade of the 21st century, the rate of crime had fallen by 58% from historic highs associated with severe drug problems in the mid-1990s, though murders remained high for a city of its size. In the first two months of 2008, the murder rate dropped dramatically, with no murders recorded for 43 days.

Newark's nicknames reflect the efforts to revitalize downtown. In the 1950s the term New Newark was given to the city by then-Mayor Leo Carlin to help convince major corporations to remain in Newark. In the 1960s Newark was nicknamed the Gateway City after the redeveloped Gateway Center area downtown, which shares its name with the tourism region

A tourism region is a geographical region that has been designated by a governmental organization or tourism bureau as having common cultural or environmental characteristics. These regions are often named after historical or current administrati ...

of which Newark is a part, the Gateway Region

The Gateway Region is the primary urbanized area of the northeastern section of New Jersey. It is anchored by Newark, the state's most populous city. While sometimes known as the Newark metropolitan area, it is part of the New York metropolitan ...

. It has more recently been called the Renaissance City by the media and the public to gain recognition for its revitalization efforts.

Tech hub

Extensive fiber optic networks in Newark started in the 1990's when telecommunication companies installed fiber optic network to put Newark as a strategic location for data transfer betweenManhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

and the rest of the country during the dot-com boom

The dot-com bubble (dot-com boom, tech bubble, or the Internet bubble) was a stock market bubble in the late 1990s, a period of massive growth in the use and adoption of the Internet.

Between 1995 and its peak in March 2000, the Nasdaq Compos ...

. At the same time, the city encouraged those companies to install more than they needed. A vacant department store was converted into a telecommunication center called 165 Halsey Street

165 Halsey Street, formerly known as the Bamberger Building, is a 14-story, office tower in Downtown Newark, New Jersey. Built in 1912–1929, it was designed by Jarvis Hunt. The building spans the entire block between Halsey Street, Market Stre ...

. It became one of the world's largest carrier hotel

A colocation center (also spelled co-location, or colo) or "carrier hotel", is a type of data centre where equipment, space, and bandwidth are available for rental to retail customers. Colocation facilities provide space, power, cooling, and ...

s. As a result after the dot-com bust, there were a surplus of dark fiber

A dark fibre or unlit fibre is an unused optical fibre, available for use in fibre-optic communication. Dark fibre may be leased from a network service provider.

Dark fibre originally referred to the potential network capacity of telecommunic ...

(unused fiber optic cables). Twenty years later, the city and other private companies started utilizing the dark fiber to create high performance networks within the city.

Since 2007, several technology oriented companies have moved to Newark: Audible

Audible may refer to:

* Audible (service), an online audiobook store

* Audible (American football), a tactic used by quarterbacks

* ''Audible'' (film), a short documentary film featuring a deaf high school football player

* Audible finish or ru ...

(global headquarters, 2007), Panasonic

formerly between 1935 and 2008 and the first incarnation of between 2008 and 2022, is a major Japanese multinational corporation, multinational Conglomerate (company), conglomerate corporation, headquartered in Kadoma, Osaka, Kadoma, Osaka P ...

(North America headquarters, 2013), AeroFarms (global headquarters, 2015), Broadridge Financial Solutions

Broadridge Financial Solutions is a public corporate services and financial technology company founded in 2007 as a spin-off from management software company :Automatic Data Processing. Broadridge supplies public companies with proxy statements ...

(1,000 jobs, 2017), WebMD

WebMD is an American corporation known primarily as an online publisher of news and information pertaining to human health and well-being. The site includes information pertaining to drugs. It is one of the top healthcare websites.

It was foun ...

(700 jobs, 2021), Ørsted (North American digital operations headquarters, 2021), and HAX Accelerator

HAX accelerator (formerly HAXLR8R) is an early stage investor and seed accelerator focused on hard tech startups. HAX has offices in San Francisco, Shenzhen, and Tokyo.

History

Founded in 2011 by Cyril Ebersweiler and Sean O'Sullivan, the root ...

(US headquarters, 2021).

See also

* Timeline of Newark, New Jersey *Sports in Newark, New Jersey

Sports in Newark, New Jersey, the second largest city in New York metropolitan area, are part of the regional Sports in New York City#Notable New York City Area Teams, professional sports and Media in New York City, media markets. The city has host ...

References

Notes Further reading * * * *External links

Newark History Society

from History of the City of Newark New Jersey, Embracing Two and Half Centuries 1666–1913; Vol. II, Lewis Historical Publishing Co.; New York-Chicago; 1913

NJ Historical Society Map of Newark 1668

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Newark, New Jersey