Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second

president of Egypt

The president of Egypt is the executive head of state of Egypt and the de facto appointer of the official head of government under the Egyptian Constitution of 2014. Under the various iterations of the Constitution of Egypt following the Eg ...

from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the

Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced

far-reaching land reforms the following year. Following a 1954 attempt on his life by a

Muslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers ( ar, جماعة الإخوان المسلمين'' ''), better known as the Muslim Brotherhood ( ', is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt by Islamic scholar and schoolteacher Hassa ...

member, he cracked down on the organization, put President

Mohamed Naguib

Mohamed Bey Naguib Youssef Qutb El-Qashlan ( ar, الرئيس اللواء محمد بك نجيب يوسف قطب القشلان, ; 19 February 1901 – 28 August 1984), also known as Mohamed Naguib, was an Egyptian revolutionary, and, along ...

under

house arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if ...

and assumed executive office. He was

formally elected president in June 1956.

Nasser's popularity in Egypt and the

Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

skyrocketed after his

nationalization

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to priv ...

of the

Suez Canal Company

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same b ...

and his political victory in the subsequent

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

, known in Egypt as the ''Tripartite Aggression''. Calls for

pan-Arab unity

Pan-Arabism ( ar, الوحدة العربية or ) is an ideology that espouses the unification of the countries of North Africa and Western Asia from the Atlantic Ocean to the Arabian Sea, which is referred to as the Arab world. It is closely c ...

under his leadership increased, culminating with the formation of the

United Arab Republic

The United Arab Republic (UAR; ar, الجمهورية العربية المتحدة, al-Jumhūrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Muttaḥidah) was a sovereign state in the Middle East from 1958 until 1971. It was initially a political union between Eg ...

with

Syria from 1958 to 1961. In 1962, Nasser began a series of major

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

measures and modernization reforms in Egypt. Despite setbacks to his

pan-Arabist

Pan-Arabism ( ar, الوحدة العربية or ) is an ideology that espouses the unification of the countries of North Africa and Western Asia from the Atlantic Ocean to the Arabian Sea, which is referred to as the Arab world. It is closely c ...

cause, by 1963 Nasser's supporters gained power in several Arab countries, but he became embroiled in the

North Yemen Civil War

The North Yemen Civil War ( ar, ثورة 26 سبتمبر, Thawra 26 Sabtambar, 26 September Revolution) was fought in North Yemen from 1962 to 1970 between partisans of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom and supporters of the Yemen Arab Republic. The w ...

, and eventually the much larger

Arab Cold War

The Arab Cold War ( ar, الحرب العربية الباردة ''al-Harb al-`Arabiyyah al-bāridah'') was a period of political rivalry in the Arab world from the early 1950s to the late 1970s as part of the broader Cold War. The generally ...

. He began his second presidential term

in March 1965 after his political opponents were banned from running. Following Egypt's defeat by

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

in the

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

of 1967, Nasser resigned, but he returned to office after popular demonstrations called for his reinstatement. By 1968, Nasser had appointed himself Prime Minister, launched the

War of Attrition

The War of Attrition ( ar, حرب الاستنزاف, Ḥarb al-Istinzāf; he, מלחמת ההתשה, Milhemet haHatashah) involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and their allies from ...

to regain the

Israeli-occupied Sinai Peninsula, began a process of depoliticizing the military, and issued a set of political liberalization reforms. After the conclusion of the

1970 Arab League summit

The 1970 Arab League summit was held on September 27 in Cairo, Egypt as an extraordinary Arab League Summit. The summit came in the aftermath of the bloody events of the Jordanian Civil War, and the clashes between the Palestinian Liberation Or ...

, Nasser suffered a heart attack and died. His funeral in

Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo met ...

drew five to six million mourners, and prompted an outpouring of grief across the Arab world.

Nasser remains an iconic figure in the Arab world, particularly for his strides towards

social justice

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, Equal opportunity, opportunities, and Social privilege, privileges within a society. In Western Civilization, Western and Culture of Asia, Asian cultures, the concept of social ...

and Arab unity, his modernization policies, and his

anti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic so ...

efforts.

His presidency also encouraged and coincided with an Egyptian cultural boom, and the launching of large industrial projects, including the

Aswan Dam

The Aswan Dam, or more specifically since the 1960s, the Aswan High Dam, is one of the world's largest embankment dams, which was built across the Nile in Aswan, Egypt, between 1960 and 1970. Its significance largely eclipsed the previous Aswan L ...

, and

Helwan

Helwan ( ar, حلوان ', , cop, ϩⲁⲗⲟⲩⲁⲛ, Halouan) is a city in Egypt and part of Greater Cairo, on the bank of the Nile, opposite the ruins of Memphis. Originally a southern suburb of Cairo, it served as the capital of the now d ...

city. Nasser's detractors criticize his

authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic vo ...

, his

human rights violation

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

s, and the dominance of the military over civil institutions that characterised his tenure, establishing a pattern of military and

dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in ti ...

ial rule in Egypt which has persisted, nearly uninterrupted, to the present day.

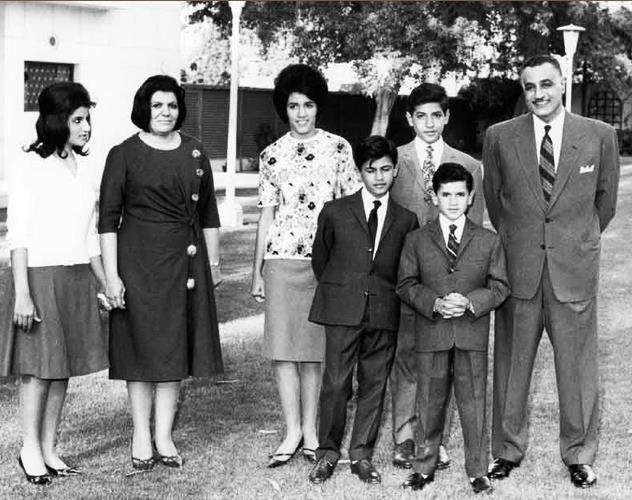

Early life

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein was born in

Bakos,

Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

, Egypt on 15 January 1918, a year before the tumultuous events of the

Egyptian Revolution of 1919

The Egyptian Revolution of 1919 ( ''Thawra 1919'') was a countrywide revolution against the British occupation of Egypt and Sudan. It was carried out by Egyptians from different walks of life in the wake of the British-ordered exile of the ...

.

Nasser's father was a postal worker born in

Beni Mur

Beni Mur ( ar, بني مر, also spelled Bani Murr) is an Egyptian town in Upper Egypt located 8 kilometers north of the city of Asyut.

History

The town is believed to be the site of Deir Abu as-Sira (a corrupted form of the name Theodor ()), a ...

in

Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ar, صعيد مصر ', shortened to , , locally: ; ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the lands on both sides of the Nile that extend wikt:downriver, upriver from Lower Egypt in the north to Nubia in the south. ...

, and raised in Alexandria,

and his mother's family came from

Mallawi

Mallawi ( ar, ملوي ; Saidi pronunciation: , ) is a city in Egypt, located in the governorate of Minya.

Overview

Situated in a farm area, the town produces textiles and handicrafts.

The total area of the city is about . The souther ...

,

el-Minya.

His parents married in 1917.

Nasser had two brothers, Izz al-Arab and al-Leithi.

Nasser's biographers Robert Stephens and

Said Aburish

Said Aburish (full name Saʿīd Muḥammad Khalīl ʾAbū Rīsh) ( ar, سعيد محمد خليل أبو الريش; 1 May 1935 – 29 August 2012), was a Palestinian journalist and writer.

Aburish was born in al-Eizariya (also known as "Bethany" ...

wrote that Nasser's family believed strongly in the "Arab notion of glory", since the name of Nasser's brother, Izz al-Arab, translates to "Glory of the Arabs".

Nasser's family traveled frequently due to his father's work. In 1921, they moved to

Asyut

AsyutAlso spelled ''Assiout'' or ''Assiut'' ( ar, أسيوط ' , from ' ) is the capital of the modern Asyut Governorate in Egypt. It was built close to the ancient city of the same name, which is situated nearby. The modern city is located at ...

and, in 1923, to

Khatatba

Khatatba is a town in the Monufia Governorate in Lower Egypt, 43 kilometers north of the Egyptian capital Cairo. It is just above the Khatatba Canal which branches off the Nile River.

History

Historically, the town served the role of a departur ...

, where Nasser's father ran a post office. Nasser attended a primary school for the children of railway employees until 1924, when he was sent to live with his paternal uncle in

Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo met ...

, and to attend the Nahhasin elementary school.

Nasser exchanged letters with his mother and visited her on holidays. He stopped receiving messages at the end of April 1926. Upon returning to Khatatba, he learned that his mother had died after giving birth to his third brother, Shawki, and that his family had kept the news from him.

Nasser later stated that "losing her this way was a shock so deep that time failed to remedy".

He adored his mother and the injury of her death deepened when his father remarried before the year's end.

In 1928, Nasser went to Alexandria to live with his maternal grandfather and attend the city's Attarin elementary school.

He left in 1929 for a private boarding school in

Helwan

Helwan ( ar, حلوان ', , cop, ϩⲁⲗⲟⲩⲁⲛ, Halouan) is a city in Egypt and part of Greater Cairo, on the bank of the Nile, opposite the ruins of Memphis. Originally a southern suburb of Cairo, it served as the capital of the now d ...

, and later returned to Alexandria to enter the Ras el-Tin secondary school and to join his father, who was working for the city's postal service.

It was in Alexandria that Nasser became involved in political activism.

After witnessing clashes between protesters and police in Manshia Square,

he joined the demonstration without being aware of its purpose. The protest, organized by the

ultranationalist

Ultranationalism or extreme nationalism is an extreme form of nationalism in which a country asserts or maintains detrimental hegemony, supremacy, or other forms of control over other nations (usually through violent coercion) to pursue its sp ...

Young Egypt Society

Young may refer to:

* Offspring, the product of reproduction of a new organism produced by one or more parents

* Youth, the time of life when one is young, often meaning the time between childhood and adulthood

Music

* The Young, an American r ...

, called for the end of colonialism in Egypt in the wake of the

1923 Egyptian constitution's annulment by Prime Minister

Isma'il Sidqi

Ismail Sidky Pasha () (15 June 1875 – 9 July 1950) was an Egyptian politician who served as Prime Minister of Egypt from 1930 to 1933 and again in 1946.

Life and career

He was born in Alexandria and was originally named Isma'il Saddiq but his ...

.

Nasser was arrested and detained for a night

before his father bailed him out.

Nasser joined the paramilitary wing of the group, known as the

Green Shirts, for a brief period in 1934. His association with the group and active role in student demonstrations during this period "imbued him with a fierce Egyptian nationalism", according to the historian James Jankowski.

When his father was transferred to Cairo in 1933, Nasser joined him and attended al-Nahda al-Masria school.

He took up acting in school plays for a brief period and wrote articles for the school's paper, including a piece on French philosopher

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

titled "Voltaire, the Man of Freedom".

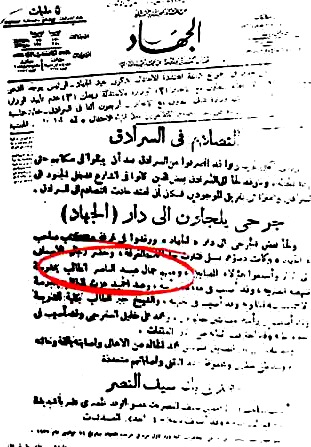

On 13 November 1935, Nasser led a student demonstration against British rule, protesting against a statement made four days prior by UK foreign minister

Samuel Hoare that rejected prospects for the 1923 Constitution's restoration.

Two protesters were killed and Nasser received a graze to the head from a policeman's bullet.

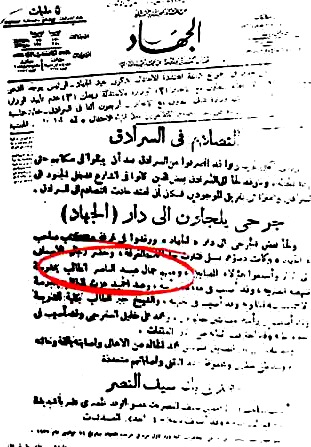

The incident garnered his first mention in the press: the nationalist newspaper ''Al Gihad'' reported that Nasser led the protest and was among the wounded.

On 12 December, the new king,

Farouk

Farooq (also transliterated as Farouk, Faruqi, Farook, Faruk, Faroeq, Faruq, or Farouq, Farooqi, Faruque or Farooqui; ar, فاروق, Fārūq) is a common Arabic given and family name. ''Al-Fārūq'' literally means "the one who distinguishes b ...

, issued a decree restoring the constitution.

Nasser's involvement in political activity increased throughout his school years, such that he only attended 45 days of classes during his last year of secondary school.

Despite it having the almost unanimous backing of Egypt's political forces, Nasser strongly objected to the

1936 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty because it stipulated the continued presence of British military bases in the country.

Nonetheless, political unrest in Egypt declined significantly and Nasser resumed his studies at al-Nahda,

where he received his

leaving certificate

A secondary school leaving qualification is a document signifying that the holder has fulfilled any secondary education requirements of their locality, often including the passage of a final qualification examination.

For each leaving certifica ...

later that year.

Early influences

Aburish asserts that Nasser was not distressed by his frequent relocations, which broadened his horizons and showed him Egyptian society's

class division

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differently ...

s.

His own social status was well below the wealthy Egyptian elite, and his discontent with those born into wealth and power grew throughout his lifetime.

Nasser spent most of his spare time reading, particularly in 1933 when he lived near the

National Library of Egypt

The Egyptian National Library and Archives ( ar, دار الكتب والوثائق القومية; "Dar el-Kotob") is located in Nile Corniche, Cairo and is the largest library in Egypt, followed by Al-Azhar University and the Bibliotheca Alex ...

. He read the

Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

, the

sayings

A saying is any concisely written or spoken expression that is especially memorable because of its meaning or style. Sayings are categorized as follows:

* Aphorism: a general, observational truth; "a pithy expression of wisdom or truth".

** Ada ...

of

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

, the lives of the

Sahaba

The Companions of the Prophet ( ar, اَلصَّحَابَةُ; ''aṣ-ṣaḥāba'' meaning "the companions", from the verb meaning "accompany", "keep company with", "associate with") were the disciples and followers of Muhammad who saw or m ...

(Muhammad's companions),

and the biographies of nationalist leaders

Napoleon,

Atatürk,

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of ...

, and

Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patr ...

and the

autobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English p ...

of

Winston Churchill.

Nasser was greatly influenced by

Egyptian nationalism

Egyptian nationalism is based on Egyptians and Egyptian culture. Egyptian nationalism has typically been a civic nationalism that has emphasized the unity of Egyptians regardless of their ethnicity or religion. Egyptian nationalism first mani ...

, as espoused by politician

Mustafa Kamel, poet

Ahmed Shawqi

Ahmed Shawqi (also written Chawki; ar, أحمد شوقي, , ; ; 1868–1932), nicknamed the Prince of Poets ( ar, أمير الشعراء ''Amīr al-Shu‘arā’''), was an Arabic poet laureate, to the Arabic literary tradition.

Life

Raised ...

,

and his anti-colonialist instructor at the

Royal Military Academy,

Aziz al-Masri

Aziz Ali al-Misri (; '' ar, عزيز علي المصري'') (1879 – 15 June 1965) was an Egyptian chief of staff and politician. He co-founded of al-Qahtaniyya, and al-‘Ahd (The Covenant), and participated in a prominent role during the Ara ...

, to whom Nasser expressed his gratitude in a 1961 newspaper interview. He was especially influenced by Egyptian writer

Tawfiq al-Hakim

Tawfiq al-Hakim or Tawfik el-Hakim ( arz, توفيق الحكيم, ; October 9, 1898 – July 26, 1987) was a prominent Egyptian writer and visionary. He is one of the pioneers of the Arabic novel and drama. The triumphs and failures that ar ...

's novel ''Return of the Spirit'', in which al-Hakim wrote that the Egyptian people were only in need of a "man in whom all their feelings and desires will be represented, and who will be for them a symbol of their objective".

Nasser later credited the novel as his inspiration to launch the coup d'état that began the

Egyptian Revolution of 1952.

Military career

In 1937, Nasser applied to the Royal Military Academy for army officer training,

but his police record of anti-government protest initially blocked his entry.

Disappointed, he enrolled in the law school at

King Fuad University,

but quit after one semester to reapply to the Military Academy. From his readings, Nasser, who frequently spoke of "dignity, glory, and freedom" in his youth, became enchanted with the stories of national liberators and heroic conquerors; a military career became his chief priority.

Convinced that he needed a ''

wasta

Wasta or wāsita () is an Arabic word that loosely translates into nepotism, ' clout' or 'who you know'. It refers to using one's connections and/or influence to get things done, including government transactions such as the quick renewal of a v ...

'', or an influential intermediary to promote his application above the others, Nasser managed to secure a meeting with Under-Secretary of War Ibrahim Khairy Pasha,

the person responsible for the academy's selection board, and requested his help.

Khairy Pasha agreed and sponsored Nasser's second application,

which was accepted in late 1937.

Nasser focused on his military career from then on, and had little contact with his family. At the academy, he met

Abdel Hakim Amer

Mohamed Abdel Hakim Amer ( arz, محمد عبد الحكيم عامر, ; 11 December 1919 – 13 September 1967) was an Egyptian military officer and politician. Amer served in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and played a leading role in the m ...

and

Anwar Sadat

Muhammad Anwar el-Sadat, (25 December 1918 – 6 October 1981) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the third president of Egypt, from 15 October 1970 until his assassination by fundamentalist army officers on 6 ...

, both of whom became important aides during his presidency.

After graduating from the academy in July 1938,

he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the infantry, and posted to

Mankabad.

It was here that Nasser and his closest comrades, including Sadat and Amer, first discussed their dissatisfaction at widespread corruption in the country and their desire to topple the monarchy. Sadat would later write that because of his "energy, clear-thinking, and balanced judgement", Nasser emerged as the group's natural leader.

In 1941, Nasser was posted to

Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

, Sudan, which was part of Egypt at the time. Nasser returned to Egypt in September 1942 after a brief stay in Sudan, then secured a position as an instructor in the Cairo Royal Military Academy in May 1943.

In February 1942, in what became known as the

Abdeen Palace Incident, British soldiers and tanks surrounded King Farouk's palace to compel the King to dismiss Prime Minister

Hussein Sirri Pasha

Hussein, Hussain, Hossein, Hossain, Huseyn, Husayn, Husein or Husain (; ar, حُسَيْن ), coming from the triconsonantal root Ḥ-S-i-N ( ar, ح س ی ن, link=no), is an Arabic name which is the diminutive of Hassan, meaning "good", "h ...

in favour of

Mostafa El-Nahas

Mostafa el-Nahhas Pasha or Mostafa Nahas ( ar, مصطفى النحاس باشا; June 15, 1879 – August 23, 1965) was an Egyptian politician who served as the Prime Minister for five terms.

Early life, education and exile

He was born in ...

, whom the United Kingdom government felt would be more sympathetetic to their war effort against the Axis. The British Ambassador,

Miles Lampson

Miles Wedderburn Lampson, 1st Baron Killearn, (24 August 1880 – 18 September 1964) was a British diplomat.

Background and education

Miles Lampson was the son of Norman Lampson, and grandson of Sir Curtis Lampson, 1st Baronet. His mothe ...

, marched into the palace, and threatened the King with the bombardment of his palace, his removal as king, and his exile from Egypt unless he conceded to the British demands. Ultimately, the 22 year old King submitted, and appointed El-Nahas. Nasser saw the incident as a blatant violation of Egyptian sovereignty and wrote, "I am ashamed that our army has not reacted against this attack",

and wished for "calamity" to overtake the British.

Nasser was accepted into the General Staff College later that year.

He began to form a group of young military officers with strong nationalist sentiments who supported some form of revolution. Nasser stayed in touch with the group's members primarily through Amer, who continued to seek out interested officers within the

Egyptian Armed Force's various branches and presented Nasser with a complete file on each of them.

1948 Arab–Israeli War

Nasser's first battlefield experience was in

Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East J ...

during the

1948 Arab–Israeli War. He initially volunteered to serve with the

Arab Higher Committee

The Arab Higher Committee ( ar, اللجنة العربية العليا) or the Higher National Committee was the central political organ of the Arab Palestinians in Mandatory Palestine. It was established on 25 April 1936, on the initiative of ...

(AHC) led by

Mohammad Amin al-Husayni

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

. Nasser met with and impressed al-Husayni,

but was ultimately refused entry to the AHC's forces by the Egyptian government for reasons that were unclear.

In May 1948, following the

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English ...

withdrawal, King Farouk sent the Egyptian army into Israel,

with Nasser serving as a staff officer of the 6th Infantry Battalion. During the war, he wrote of the Egyptian army's unpreparedness, saying "our soldiers were dashed against fortifications".

Nasser was deputy commander of the Egyptian forces that secured the

Faluja pocket

al-Faluja ( ar, الفالوجة) was a Palestinian Arab village in the British Mandate for Palestine, located 30 kilometers northeast of Gaza City. The village and the neighbouring village of Iraq al-Manshiyya formed part of the Faluja pocket ...

(commanded by Said Taha Bey nicknamed the "Sudanese tiger" by the Israelis). On 12 July, he was lightly wounded in the fighting. By August, his brigade was surrounded by the

Israeli Army

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the State of Israel. It consists of three service branch ...

. Appeals for help from

Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

's

Arab Legion

The Arab Legion () was the police force, then regular army of the Emirate of Transjordan, a British protectorate, in the early part of the 20th century, and then of independent Jordan, with a final Arabization of its command taking place in 19 ...

went unheeded, but the brigade refused to surrender. Negotiations between

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

and Egypt finally resulted in the ceding of Faluja to Israel.

According to veteran journalist

Eric Margolis, the defenders of Faluja, "including young army officer Gamal Abdel Nasser, became national heroes" for enduring Israeli bombardment while isolated from their command.

Still stationed after the war in the Faluja enclave, Nasser agreed to an Israeli request to identify 67 killed soldiers of the

"religious platoon". The expedition was led by Rabbi

Shlomo Goren

Shlomo Goren ( he, שלמה גורן; February 3, 1917 – October 29, 1994), was a Polish-born Israeli Orthodox Religious Zionist rabbi and Talmudic scholar who was considered a foremost authority on Jewish law (Halakha). Goren founded and se ...

and Nasser personally accompanied him, ordering the Egyptian soldiers to stand at attention. They spoke briefly, and according to Goren, after learning what the

square phylacteries found with the soldiers were, Nasser told him that he "now understands their courageous stand". During an interview on Israeli TV in 1971, Rabbi Goren claimed the two agreed to meet again when the time of peace comes.

The Egyptian singer

Umm Kulthum

Umm Kulthum ( ar, أم كلثوم, , also spelled ''Oum Kalthoum'' in English; born Fatima Ibrahim es-Sayyid el-Beltagi, ar, فاطمة إبراهيم السيد البلتاجي, Fāṭima ʾIbrāhīm es-Sayyid el-Beltāǧī, link=no; 31 Dece ...

hosted a public celebration for the officers' return despite reservations from the royal government, which had been pressured by the British to prevent the reception. The apparent difference in attitude between the government and the general public increased Nasser's determination to topple the monarchy.

Nasser had also felt bitter that his brigade had not been relieved despite the resilience it displayed.

He started writing his book ''Philosophy of the Revolution'' during the siege.

After the war, Nasser returned to his role as an instructor at the Royal Military Academy.

He sent emissaries to forge an alliance with the

Muslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers ( ar, جماعة الإخوان المسلمين'' ''), better known as the Muslim Brotherhood ( ', is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt by Islamic scholar and schoolteacher Hassa ...

in October 1948, but soon concluded that the religious agenda of the Brotherhood was not compatible with his nationalism. From then on, Nasser prevented the Brotherhood's influence over his cadres' activities without severing ties with the organization.

Nasser was sent as a member of the Egyptian delegation to

Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

in February 1949 to negotiate a formal

armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

with Israel, and reportedly considered the terms to be humiliating, particularly because the Israelis were able to easily

occupy the

Eilat

Eilat ( , ; he, אֵילַת ; ar, إِيلَات, Īlāt) is Israel's southernmost city, with a population of , a busy port and popular resort at the northern tip of the Red Sea, on what is known in Israel as the Gulf of Eilat and in Jorda ...

region while negotiating with the Arabs in March.

Revolution

Free Officers

Nasser's return to Egypt coincided with

Husni al-Za'im

Husni al-Za'im ( ar, حسني الزعيم ''Ḥusnī az-Za’īm''; 11 May 1897 – 14 August 1949) was a Syrian military officer and politician of Kurdish origin. Husni al-Za'im, had been an officer in the Ottoman Army. After France instituted ...

's Syrian

coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, ...

.

Its success and evident popular support among the Syrian people encouraged Nasser's revolutionary pursuits.

Soon after his return, he was summoned and interrogated by Prime Minister

Ibrahim Abdel Hadi regarding suspicions that he was forming a secret group of dissenting officers.

According to secondhand reports, Nasser convincingly denied the allegations.

Abdel Hadi was also hesitant to take drastic measures against the army, especially in front of its chief of staff, who was present during the interrogation, and subsequently released Nasser.

The interrogation pushed Nasser to speed up his group's activities.

After 1949, the group adopted the name "

Association of Free Officers" and advocated "little else but freedom and the restoration of their country’s dignity".

Nasser organized the Free Officers' founding committee, which eventually comprised fourteen men from different social and political backgrounds, including representation from Young Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood, the Egyptian Communist Party, and the aristocracy.

Nasser was unanimously elected chairman of the organization.

In the 1950 parliamentary elections, the

Wafd Party

The Wafd Party (; ar, حزب الوفد, ''Ḥizb al-Wafd'') was a nationalist liberal political party in Egypt. It was said to be Egypt's most popular and influential political party for a period from the end of World War I through the 1930s ...

of

el-Nahhas gained a victory—mostly due to the absence of the Muslim Brotherhood, which boycotted the elections—and was perceived as a threat by the Free Officers as the Wafd had campaigned on demands similar to their own.

Accusations of corruption against Wafd politicians began to surface, however, breeding an atmosphere of rumor and suspicion that consequently brought the Free Officers to the forefront of Egyptian politics.

By then, the organization had expanded to around ninety members. According to

Khaled Mohieddin

Khaled Mohieddine ( arz, خالد محيى الدين, ; August 17, 1922 – May 6, 2018) was an Egyptian revolutionary, politician, and military officer. As a member of the Free Officers Movement, he participated in the toppling of King Farouk ...

, "nobody knew all of them and where they belonged in the hierarchy except Nasser".

Nasser felt that the Free Officers were not ready to move against the government and, for nearly two years, he did little beyond officer recruitment and underground news bulletins.

On 11 October 1951, the Wafd government abrogated the unpopular

Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 by which the United Kingdom had the right to maintain its military forces in the Suez Canal Zone.

The popularity of this move, as well as that of government-sponsored guerrilla attacks against the British, put pressure on Nasser to act.

According to Sadat, Nasser decided to wage "a large scale assassination campaign".

In January 1952, he and

Hassan Ibrahim

Hassan Ibrahim (1917 – 1990) was an Egyptian Air Force officer and one of the founders of the Free Officers movement.

Early life and education

Ibrahim was born in Alexandria in 1917. He graduated from the Egyptian Air Academy in 1927.

Free ...

attempted to kill the royalist general

Hussein Sirri Amer by firing their submachine guns at his car as he drove through the streets of Cairo.

Instead of killing the general, the attackers wounded an innocent female passerby.

Nasser recalled that her wails "haunted" him and firmly dissuaded him from undertaking similar actions in the future.

Sirri Amer was close to King Farouk, and was nominated for the presidency of the Officer's Club—normally a ceremonial office—with the king's backing.

Nasser was determined to establish the independence of the army from the monarchy, and with Amer as the intercessor, resolved to field a nominee for the Free Officers.

They selected

Mohamed Naguib

Mohamed Bey Naguib Youssef Qutb El-Qashlan ( ar, الرئيس اللواء محمد بك نجيب يوسف قطب القشلان, ; 19 February 1901 – 28 August 1984), also known as Mohamed Naguib, was an Egyptian revolutionary, and, along ...

, a popular general who had offered his resignation to Farouk in 1942 over British high-handedness and was wounded three times in the Palestine War.

Naguib won overwhelmingly and the Free Officers, through their connection with a leading Egyptian daily, ''al-Misri'', publicized his victory while praising the nationalistic spirit of the army.

Revolution of 1952

On 25 January 1952, at a time of growing

fedayeen

Fedayeen ( ar, فِدائيّين ''fidāʼīyīn'' "self-sacrificers") is an Arabic term used to refer to various military groups willing to sacrifice themselves for a larger campaign.

Etymology

The term ''fedayi'' is derived from Arabic: '' ...

attacks on British forces occupying the Suez Canal Zone, some 7,000 British soldiers attacked the main police station in the Canal city

Ismailia

Ismailia ( ar, الإسماعيلية ', ) is a city in north-eastern Egypt. Situated on the west bank of the Suez Canal, it is the capital of the Ismailia Governorate. The city has a population of 1,406,699 (or approximately 750,000, inclu ...

. In the ensuing battle, which lasted two hours, 50 Egyptian policeman were killed, sparking outrage across Egypt, and the

Cairo Fire riots which left 76 people dead. Afterwards, Nasser published a simple six-point program in ''

Rose al-Yūsuf

''Rose al-Yūsuf'' ( ar, روز اليوسف; also written ''Rose al-Yousef'') is an Arabic weekly political magazine published in Egypt.

History and profile

''Rose al-Yūsuf'' was first published on 26 October 1925. The magazine was named af ...

'' to dismantle

feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structu ...

and British influence in Egypt. In May, Nasser received word that Farouk knew the names of the Free Officers and intended to arrest them; he immediately entrusted Free Officer Zakaria Mohieddin with the task of planning the government takeover by army units loyal to the association.

The Free Officers' intention was not to install themselves in government, but to re-establish a parliamentary democracy. Nasser did not believe that a low-ranking officer like himself (a

lieutenant colonel) would be accepted by the Egyptian people, and so selected General Naguib to be his "boss" and lead the coup in name. The revolution they had long sought was launched on 22 July and was declared a success the next day. The Free Officers seized control of all government buildings, radio stations, and police stations, as well as army headquarters in Cairo. While many of the rebel officers were leading their units, Nasser donned civilian clothing to avoid detection by royalists and moved around Cairo monitoring the situation.

In a move to stave off foreign intervention two days before the revolution, Nasser had notified the American and British governments of his intentions, and both had agreed not to aid Farouk.

Under pressure from the Americans, Nasser had agreed to exile the deposed king with an honorary ceremony.

On 18 June 1953, the monarchy was abolished and the Republic of Egypt declared, with Naguib as its

first president

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number 1 (number), one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, D ...

.

According to Aburish, after assuming power, Nasser and the Free Officers expected to become the "guardians of the people's interests" against the monarchy and the

pasha

Pasha, Pacha or Paşa ( ota, پاشا; tr, paşa; sq, Pashë; ar, باشا), in older works sometimes anglicized as bashaw, was a higher rank in the Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, generals, dignita ...

class while leaving the day-to-day tasks of government to civilians.

They asked former prime minister Ali Maher to accept reappointment to his previous position, and to form an all-civilian cabinet.

The Free Officers then governed as the

Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) with Naguib as chairman and Nasser as vice-chairman. Relations between the RCC and Maher grew tense, however, as the latter viewed many of Nasser's schemes—agrarian reform, abolition of the monarchy, reorganization of political parties

—as too radical, culminating in Maher's resignation on 7 September. Naguib assumed the additional role of prime minister, and Nasser that of deputy prime minister. In September, the

Agrarian Reform Law was put into effect.

In Nasser's eyes, this law gave the RCC its own identity and transformed the coup into a revolution.

Preceding the reform law, in August 1952, communist-led riots broke out at textile factories in

Kafr el-Dawwar

Kafr El Dawwar ( ar, كفر الدوار, lit=town of the farm ) is a major industrial city and municipality on the Nile Delta in the Beheira Governorate of northern Egypt. Located approximately 30 km from Alexandria, the municipali ...

, leading to a clash with the army that left nine people dead. While most of the RCC insisted on executing the riot's two ringleaders, Nasser opposed this. Nonetheless, the sentences were carried out. The Muslim Brotherhood supported the RCC, and after Naguib's assumption of power, demanded four ministerial portfolios in the new cabinet. Nasser turned down their demands and instead hoped to co-opt the Brotherhood by giving two of its members, who were willing to serve officially as independents, minor ministerial posts.

Road to presidency

Disputes with Naguib

In January 1953, Nasser overcame opposition from Naguib and banned all political parties,

creating a one-party system under the Liberation Rally, a loosely structured movement whose chief task was to organize pro-RCC rallies and lectures,

with Nasser its

secretary-general

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derive ...

. Despite the dissolution order, Nasser was the only RCC member who still favored holding parliamentary elections, according to his fellow officer

Abdel Latif Boghdadi

ʿAbd al-Laṭīf al-Baghdādī ( ar, عبداللطيف البغدادي, 1162 Baghdad–1231 Baghdad), short for Muwaffaq al-Dīn Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Laṭīf ibn Yūsuf al-Baghdādī ( ar, موفق الدين محمد عبد اللطيف بن ...

.

Although outvoted, he still advocated holding elections by 1956.

In March 1953, Nasser led the Egyptian delegation negotiating a British withdrawal from the Suez Canal.

When Naguib began showing signs of independence from Nasser by distancing himself from the RCC's land reform decrees and drawing closer to Egypt's established political forces, namely the Wafd and the Brotherhood,

Nasser resolved to depose him.

In June, Nasser took control of the interior ministry post from Naguib loyalist

Sulayman Hafez

Sulayman Hafez was an Egyptian lawyer and politician. Hafez drafted the abdication letter of King Farouk and negotiated his stepping down following the Egyptian Revolution of 1952.Kandil, p. 27.

In early 1953, following the revolution, Hafez ...

,

and pressured Naguib to conclude the abolition of the monarchy.

On 25 February 1954, Naguib announced his resignation after the RCC held an official meeting without his presence two days prior.

On 26 February, Nasser accepted the resignation, put Naguib under house arrest,

and the RCC proclaimed Nasser as both RCC chairman and prime minister. As Naguib intended, a mutiny immediately followed, demanding Naguib's reinstatement and the RCC's dissolution.

While visiting the striking officers at Military Headquarters (GHQ) to call for the mutiny's end, Nasser was initially intimidated into accepting their demands.

However, on 27 February, Nasser's supporters in the army launched a raid on the GHQ, ending the mutiny. Later that day, hundreds of thousands of protesters, mainly belonging to the Brotherhood, called for Naguib's return and Nasser's imprisonment.

In response, a sizable group within the RCC, led by Khaled Mohieddin, demanded Naguib's release and return to the presidency.

Nasser acquiesced, but delayed Naguib's reinstatement until 4 March, allowing him to promote Amer to Commander of the Armed Forces—a position formerly occupied by Naguib.

On 5 March, Nasser's security coterie arrested thousands of participants in the uprising.

As a ruse to rally opposition against a return to the pre-1952 order, the RCC decreed an end to restrictions on monarchy-era parties and the Free Officers' withdrawal from politics.

The RCC succeeded in provoking the beneficiaries of the revolution, namely the workers, peasants, and petty bourgeois, to oppose the decrees,

with one million transport workers launching a strike and thousands of peasants entering Cairo in protest in late March.

Naguib sought to crack down on the protesters, but his requests were rebuffed by the heads of the security forces.

On 29 March, Nasser announced the decrees' revocation in response to the "impulse of the street".

Between April and June, hundreds of Naguib's supporters in the military were either arrested or dismissed, and Mohieddin was informally exiled to

Switzerland to represent the RCC abroad.

King Saud

Saud bin Abdulaziz Al Saud ( ar, سعود بن عبد العزيز آل سعود ''Suʿūd ibn ʿAbd al ʿAzīz Āl Suʿūd'', Najdi Arabic pronunciation: ; 15 January 1902 – 23 February 1969) was King of Saudi Arabia from 9 November 1953 ...

of

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries by area, fifth-largest country in Asia ...

attempted to mend relations between Nasser and Naguib, but to no avail.

Assuming chairmanship of RCC

On 26 October 1954, Muslim Brotherhood member Mahmoud Abdel-Latif attempted to assassinate Nasser while he was delivering a speech in Alexandria, broadcast to the Arab world by radio, to celebrate the British military withdrawal. The gunman was away from him and fired eight shots, but all missed Nasser. Panic broke out in the mass audience, but Nasser maintained his posture and raised his voice to appeal for calm.

With great emotion he exclaimed the following:

My countrymen, my blood spills for you and for Egypt. I will live for your sake and die for the sake of your freedom and honor. Let them kill me; it does not concern me so long as I have instilled pride, honor, and freedom in you. If Gamal Abdel Nasser should die, each of you shall be Gamal Abdel Nasser ... Gamal Abdel Nasser is of you and from you and he is willing to sacrifice his life for the nation.

The crowd roared in approval and Arab audiences were electrified. The assassination attempt backfired, quickly playing into Nasser's hands.

Upon returning to Cairo, he ordered one of the largest political crackdowns in the modern history of Egypt,

with the arrests of thousands of dissenters, mostly members of the Brotherhood, but also communists, and the dismissal of 140 officers loyal to Naguib.

Eight Brotherhood leaders were sentenced to death,

although the sentence of its chief ideologue,

Sayyid Qutb

Sayyid 'Ibrāhīm Ḥusayn Quṭb ( or ; , ; ar, سيد قطب إبراهيم حسين ''Sayyid Quṭb''; 9 October 1906 – 29 August 1966), known popularly as Sayyid Qutb ( ar, سيد قطب), was an Egyptian author, educator, Islamic ...

, was commuted to a 15-year imprisonment. Naguib was removed from the presidency and put under house arrest, but was never tried or sentenced, and no one in the army rose to defend him. With his rivals neutralized, Nasser became the undisputed leader of Egypt.

Nasser's street following was still too small to sustain his plans for reform and to secure him in office.

To promote himself and the Liberation Rally, he gave speeches in a cross-country tour,

and imposed controls over the country's Egyptian newspapers, press by decreeing that all publications had to be approved by the party to prevent "sedition".

Both

Umm Kulthum

Umm Kulthum ( ar, أم كلثوم, , also spelled ''Oum Kalthoum'' in English; born Fatima Ibrahim es-Sayyid el-Beltagi, ar, فاطمة إبراهيم السيد البلتاجي, Fāṭima ʾIbrāhīm es-Sayyid el-Beltāǧī, link=no; 31 Dece ...

and Abdel Halim Hafez, the leading Arab singers of the era, performed songs praising Nasser's nationalism. Others produced plays denigrating his political opponents.

According to his associates, Nasser orchestrated the campaign himself.

Arab nationalist terms such "Arab homeland" and "Arab nation" frequently began appearing in his speeches in 1954–55, whereas prior he would refer to the Arab "peoples" or the "Arab region". In January 1955, the RCC appointed him as their president, pending national elections.

Nasser made secret contacts with Israel in 1954–55, but determined that peace with Israel would be impossible, considering it an "expansionist state that viewed the Arabs with disdain". On 28 February 1955, Israeli troops Operation Black Arrow, attacked the Egyptian-held Gaza Strip with the stated aim of suppressing Palestinian fedayeen raids. Nasser did not feel that the Egyptian Army was ready for a confrontation and did not retaliate militarily. His failure to respond to Israeli military action demonstrated the ineffectiveness of his armed forces and constituted a blow to his growing popularity.

Nasser subsequently ordered the tightening of the Israeli passage through the Suez Canal and Straits of Tiran, blockade on Israeli shipping through the Straits of Tiran and restricted the use of airspace over the Gulf of Aqaba by Israeli aircraft in early September.

The Israelis re-militarized the Auja al-Hafir, al-Auja Demilitarized Zone on the Egyptian border on 21 September.

Simultaneous with Israel's February raid, the Baghdad Pact was formed between some regional allies of the UK. Nasser considered the Baghdad Pact a threat to his efforts to eliminate British military influence in the Middle East, and a mechanism to undermine the Arab League and "perpetuate [Arab] subservience to Zionism and [Western] imperialism".

Nasser felt that if he was to maintain Egypt's regional leadership position he needed to acquire modern weaponry to arm his military. When it became apparent to him that Western world, Western countries would not supply Egypt under acceptable financial and military terms,

Nasser turned to the Eastern Bloc and concluded a armaments agreement with Czechoslovakia on 27 September.

Through the Egyptian-Czech arms deal, Czechoslovakian arms deal, the balance of power between Egypt and Israel was more or less equalized and Nasser's role as the Arab leader defying the West was enhanced.

Adoption of neutralism

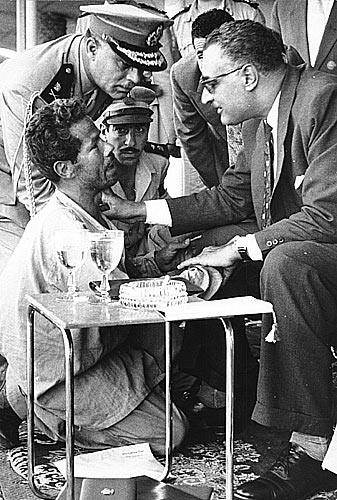

At the Asian–African Conference, Bandung Conference in Indonesia in late April 1955, Nasser was treated as the leading representative of the Arab countries and was one of the most popular figures at the summit.

He had paid earlier visits to Pakistan (9 April), India (14 April), Burma, and Afghanistan on the way to Bandung,

and previously cemented a treaty of friendship with India in Cairo on 6 April, strengthening Egypt–India relations, Egyptian–Indian relations on the international policy and economic development fronts.

Nasser mediated discussions between the pro-Western, pro-Soviet, and neutralist conference factions over the composition of the "Final Communique"

addressing colonialism in Africa and Asia and the fostering of global peace amid the Cold War between the West and the Soviet Union. At Bandung, Nasser sought a proclamation for the avoidance of international defense alliances, support for the independence of Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco from French colonialism, French rule, support for the Palestinian right of return, and the implementation of UN resolutions regarding the Arab–Israeli conflict. He succeeded in lobbying the attendees to pass resolutions on each of these issues, notably securing the strong support of China and India.

Following Bandung, Nasser officially adopted the "positive neutralism" of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Yugoslavian president Josip Broz Tito and Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru as a principal theme of Egyptian foreign policy regarding the Cold War.

Nasser was welcomed by large crowds of people lining the streets of Cairo on his return to Egypt on 2 May and was widely heralded in the press for his achievements and leadership in the conference. Consequently, Nasser's prestige was greatly boosted, as was his self-confidence and image.

1956 constitution and presidency

With his domestic position considerably strengthened, Nasser was able to secure primacy over his RCC colleagues and gained relatively unchallenged decision-making authority,

particularly over foreign policy.

In January 1956, the new Egyptian Constitution of 1956, Constitution of Egypt was drafted, entailing the establishment of a single-party system under the National Union (NU),

a movement Nasser described as the "cadre through which we will realize our revolution". The NU was a reconfiguration of the Liberation Rally,

which Nasser determined had failed in generating mass public participation.

In the new movement, Nasser attempted to incorporate more citizens, approved by local-level party committees, in order to solidify popular backing for his government.

The NU would select a nominee for the presidential election whose name would be provided for public approval.

Nasser's nomination for the post and the new constitution were put to 1956 Egyptian referendum, public referendum on 23 June and each was approved by an overwhelming majority.

A 350-member People's Assembly (Egypt), National Assembly was established,

elections for which were held in July 1957. Nasser had ultimate approval over all the candidates.

The constitution granted women's suffrage, prohibited discrimination by sex, and entailed special protection for women in the workplace. Coinciding with the new constitution and Nasser's presidency, the RCC dissolved itself and its members resigned their military commissions as part of the transition to civilian rule.

During the deliberations surrounding the establishment of a new government, Nasser began a process of sidelining his rivals among the original Free Officers, while elevating his closest allies to high-ranking positions in the cabinet.

Nationalization of the Suez Canal Company

After the three-year transition period ended with Nasser's official assumption of power, his domestic and independent foreign policies increasingly collided with the regional interests of the UK and France. The latter condemned his strong support for Algerian War of Independence, Algerian independence, and the UK's Anthony Eden, Eden government was agitated by Nasser's campaign against the Baghdad Pact.

In addition, Nasser's adherence to neutralism regarding the Cold War, recognition of communist China, and Egyptian-Czech arms deal, arms deal with the Eastern bloc alienated the United States. On 19 July 1956, the US and UK abruptly withdrew their offer to finance construction of the Aswan Dam,

citing concerns that Egypt's economy would be overwhelmed by the project.

Nasser was informed of the British–American withdrawal in a news statement while aboard a plane returning to Cairo from Belgrade, and took great offense.

Although ideas for nationalizing the Suez Canal Company were in the offing after the UK agreed to withdraw its military from Egypt in 1954 (the last British troops left on 13 June 1956), journalist Mohamed Hassanein Heikal asserts that Nasser made the final decision to nationalize the company that operated the waterway between 19 and 20 July.

Nasser himself would later state that he decided on 23 July, after studying the issue and deliberating with some of his advisers from the dissolved RCC, namely Boghdadi and technical specialist Mahmoud Younis, beginning on 21 July.

The rest of the RCC's former members were informed of the decision on 24 July, while the bulk of the cabinet was unaware of the nationalization scheme until hours before Nasser publicly announced it.

According to Ramadan, Nasser's decision to nationalize the canal was a solitary decision, taken without consultation.

On 26 July 1956, Nasser gave a speech in Alexandria announcing the nationalization of the

Suez Canal Company

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same b ...

as a means to fund the Aswan Dam project in light of the British–American withdrawal.

In the speech, he denounced British Empire, British imperialism in Egypt and British control over the canal company's profits, and upheld that the Egyptian people had a right to sovereignty over the waterway, especially since "120,000 Egyptians had died building it".

The motion was technically in breach of the international agreement he had signed with the UK on 19 October 1954,

although he ensured that all existing stockholders would be paid off.

The nationalization announcement was greeted very emotionally by the audience and, throughout the Arab world, thousands entered the streets shouting slogans of support.

US ambassador Henry A. Byroade stated, "I cannot overemphasize [the] popularity of the Canal Company nationalization within Egypt, even among Nasser's enemies."

Egyptian political scientist Mahmoud Hamad wrote that, prior to 1956, Nasser had consolidated control over Egypt's military and civilian bureaucracies, but it was only after the canal's nationalization that he gained near-total popular legitimacy and firmly established himself as the "charismatic leader" and "spokesman for the masses not only in Egypt, but all over the Third World". According to Aburish, this was Nasser's largest pan-Arab triumph at the time and "soon his pictures were to be found in the tents of Yemen, the souks of Marrakesh, and the posh villas of Syria".

The official reason given for the nationalization was that funds from the canal would be used for the construction of the dam in Aswan.

That same day, Egypt closed the canal to Israeli shipping.

Suez Crisis

France and the UK, the largest shareholders in the Suez Canal Company, saw its nationalization as yet another hostile measure aimed at them by the Egyptian government. Nasser was aware that the canal's nationalization would instigate an international crisis and believed the prospect of military intervention by the two countries was 80 percent likely. Nasser dismissed their claims, and believed that the UK would not be able to intervene militarily for at least two months after the announcement, and dismissed Israeli action as "impossible". In early October, the United Nations Security Council, UN Security Council met on the matter of the canal's nationalization and adopted United Nations Security Council Resolution 118, a resolution recognizing Egypt's right to control the canal as long as it continued to allow passage through it for foreign ships. According to Heikal, after this agreement, "Nasser estimated that the danger of invasion had dropped to 10 percent". Shortly thereafter, however, the UK, France, and Israel made a Protocol of Sèvres, secret agreement to take over the Suez Canal, occupy the Suez Canal zone,

and topple Nasser.

On 29 October 1956, Israeli forces crossed the Sinai Peninsula, overwhelmed Egyptian army posts, and quickly advanced to their objectives. Two days later, British and French planes bombarded Egyptian airfields in the canal zone.

Nasser ordered the military's high command to withdraw the Egyptian Army from Sinai to bolster the canal's defenses.

Moreover, he feared that if the armored corps was dispatched to confront the Israeli invading force and the British and French subsequently landed in the canal city of Port Said, Egyptian armor in the Sinai would be cut off from the canal and destroyed by the combined tripartite forces.

Amer strongly disagreed, insisting that Egyptian tanks meet the Israelis in battle.

The two had a heated exchange on 3 November, and Amer conceded.

Nasser also ordered blockage of the canal by sinking or otherwise disabling forty-nine ships at its entrance.

Despite the commanded withdrawal of Egyptian troops, about 2,000 Egyptian soldiers were killed during engagement with Israeli forces,

and some 5,000 Egyptian soldiers were captured by the Israeli Army.

Amer and Salah Salem proposed requesting a ceasefire, with Salem further recommending that Nasser surrender himself to British forces.

Nasser berated Amer and Salem, and vowed, "Nobody is going to surrender."

Nasser assumed military command. Despite the relative ease in which Sinai was occupied, Nasser's prestige at home and among Arabs was undamaged. To counterbalance the Egyptian Army's dismal performance, Nasser authorized the distribution of about 400,000 rifles to civilian volunteers and hundreds of militias were formed throughout Egypt, many led by Nasser's political opponents.

It was at Port Said that Nasser saw a confrontation with the invading forces as being the strategic and psychological focal point of Egypt's defense.

A third infantry battalion and hundreds of national guardsmen were sent to the city as reinforcements, while two regular companies were dispatched to organize popular resistance.

Nasser and Boghdadi traveled to the canal zone to boost the morale of the armed volunteers. According to Boghdadi's memoirs, Nasser described the Egyptian Army as "shattered" as he saw the wreckage of Egyptian military equipment en route.

When British and French forces landed in Port Said on 5–6 November, its local militia put up a stiff resistance, resulting in street-to-street fighting.

The Egyptian Army commander in the city was preparing to request terms for a ceasefire, but Nasser ordered him to desist. The British-French forces managed to largely secure the city by 7 November.

Between 750 and 1,000 Egyptians were killed in the battle for Port Said.

The US Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower, Eisenhower administration condemned the tripartite invasion, and supported UN resolutions demanding withdrawal and a United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) to be stationed in Sinai.

Nasser commended Eisenhower, stating he played the "greatest and most decisive role" in stopping the "tripartite conspiracy". By the end of December, British and French forces had totally withdrawn from Egyptian territory,

while Israel completed its withdrawal in March 1957 and released all Egyptian prisoners of war.

As a result of the Suez Crisis, Nasser brought in a set of regulations imposing rigorous requirements for residency and citizenship as well as 1956–57 exodus and expulsions from Egypt, forced expulsions, mostly affecting British and French nationals and Jews with foreign nationality, as well as many Egyptian Jews. Some 25,000 Jews, almost half of the Jewish community, left in 1956, mainly for Israel, Europe, the United States and South America.

After the fighting ended, Amer accused Nasser of provoking an unnecessary war and then blaming the military for the result. On 8 April, the canal was reopened, and Nasser's political position was enormously enhanced by the widely perceived failure of the invasion and attempt to topple him. British diplomat Sir Anthony Nutting, 3rd Baronet, Anthony Nutting claimed the crisis "established Nasser finally and completely" as the ''rayyes'' (president) of Egypt.

Pan-Arabism and socialism

By 1957, pan-Arabism had become the dominant ideology in the Arab world, and the average Arab citizen considered Nasser their undisputed leader.

Historian Adeed Dawisha credited Nasser's status to his "charisma, bolstered by his perceived victory in the Suez Crisis".

The Cairo-based Voice of the Arabs radio station spread Nasser's ideas of united Arab action throughout the Arabic-speaking world, so much so that historian Eugene Rogan wrote, "Nasser conquered the Arab world by radio." Lebanese sympathizers of Nasser and the Egyptian embassy in Beirut—the press center of the Arab world—bought out Lebanese media outlets to further disseminate Nasser's ideals.

Egypt also expanded its policy of secondment, dispatching thousands of high-skilled Egyptian professionals (usually politically active teachers) across the region.

Nasser also enjoyed the support of Arab nationalist civilian and paramilitary organizations throughout the region. His followers were numerous and well-funded, but lacked any permanent structure and organization. They called themselves "Nasserites", despite Nasser's objection to the label (he preferred the term "Arab nationalists").

In January 1957, the US adopted the Eisenhower Doctrine and pledged to prevent the spread of communism and its perceived agents in the Middle East.

Although Nasser was an opponent of communism in the region, his promotion of pan-Arabism was viewed as a threat by pro-Western states in the region.

Eisenhower tried to isolate Nasser and reduce his regional influence by attempting to transform King Saud into a counterweight.

Also in January, the elected Jordanian prime minister and Nasser supporter

Sulayman al-Nabulsi brought Jordan into a military pact with Egypt, Syria, and Saudi Arabia.

Relations between Nasser and King Hussein of Jordan deteriorated in April when Hussein implicated Nasser in two coup attempts against him

—although Nasser's involvement was never established—and dissolved al-Nabulsi's cabinet.

Nasser subsequently slammed Hussein on Cairo radio as being "a tool of the imperialists".

Relations with King Saud also became antagonistic as the latter began to fear that Nasser's increasing popularity in Saudi Arabia was a genuine threat to the House of Saud, royal family's survival.

Despite opposition from the governments of Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Lebanon, Nasser maintained his prestige among their citizens and those of other Arab countries.

By the end of 1957, Nasser nationalized all remaining British and French assets in Egypt, including the tobacco, cement, pharmaceutical, and phosphate industries.

When efforts to offer tax incentives and attract outside investments yielded no tangible results, he nationalized more companies and made them a part of his economic development organization.

He stopped short of total government control: two-thirds of the economy was still in private hands.

This effort achieved a measure of success, with increased agricultural production and investment in industrialization.

Nasser initiated the Helwan steelworks, which subsequently became Egypt's largest enterprise, providing the country with product and tens of thousands of jobs.

Nasser also decided to cooperate with the Soviet Union in the construction of the Aswan Dam to replace the withdrawal of US funds.

United Arab Republic

Despite his popularity with the people of the Arab world, by mid-1957 his only regional ally was Syria.

In September, Turkish army, Turkish troops massed along the Syrian border, giving credence to rumors that the Baghdad Pact countries Syrian Crisis of 1957, were attempting to topple Syria's leftist government.

Nasser sent a contingent force to Syria as a symbolic display of solidarity, further elevating his prestige in the Arab world, and particularly among Syrians.

As political instability grew in Syria, delegations from the country were sent to Nasser demanding immediate unification with Egypt.

Nasser initially turned down the request, citing the two countries' incompatible political and economic systems, lack of Geographic contiguity, contiguity, the Syrian military's record of intervention in politics, and the deep factionalism among Syria's political forces.

However, in January 1958, a second Syrian delegation managed to convince Nasser of an impending communist takeover and a consequent slide to civil strife.

Nasser subsequently opted for union, albeit on the condition that it would be a total political merger with him as its president, to which the delegates and Syrian president Shukri al-Quwatli agreed.

On 1 February, the

United Arab Republic

The United Arab Republic (UAR; ar, الجمهورية العربية المتحدة, al-Jumhūrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Muttaḥidah) was a sovereign state in the Middle East from 1958 until 1971. It was initially a political union between Eg ...

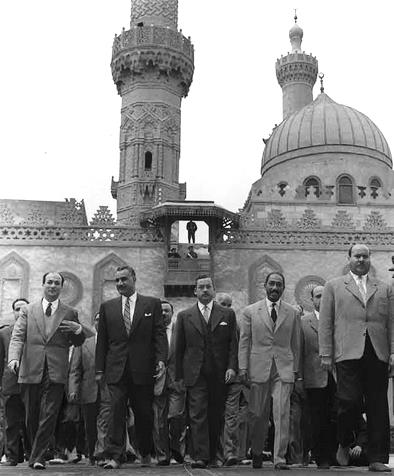

(UAR) was proclaimed and, according to Dawisha, the Arab world reacted in "stunned amazement, which quickly turned into uncontrolled euphoria."

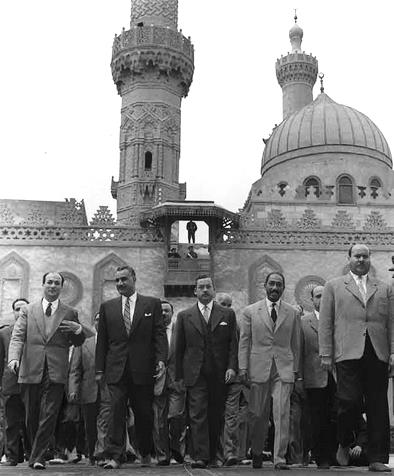

Nasser ordered a crackdown against Syrian communists, dismissing many of them from their governmental posts.

On a surprise visit to Damascus to celebrate the union on 24 February, Nasser was welcomed by crowds in the hundreds of thousands.

Crown Prince Imam Badr of North Yemen was dispatched to Damascus with proposals to include his country in the new republic. Nasser agreed to establish a loose federal union with Yemen—the United Arab States—in place of total integration.

While Nasser was in Syria, King Saud planned to have him assassinated on his return flight to Cairo.

On 4 March, Nasser addressed the masses in Damascus and waved before them the Saudi check given to Syrian security chief and, unbeknownst to the Saudis, ardent Nasser supporter Abdel Hamid Sarraj to shoot down Nasser's plane.

As a consequence of Saud's plot, he was forced by senior members of the Saudi royal family to informally cede most of his powers to his brother, Faisal of Saudi Arabia, King Faisal, a major Nasser opponent who advocated pan-Islamism, pan-Islamic unity over pan-Arabism.

A day after announcing the attempt on his life, Nasser established a new provisional constitution proclaiming a 600-member National Assembly (400 from Egypt and 200 from Syria) and the dissolution of all political parties.

Nasser gave each of the provinces two vice-presidents: Boghdadi and Amer in Egypt, and Sabri al-Asali and Akram al-Hawrani in Syria.

Nasser then left for Moscow to meet with Nikita Khrushchev. At the meeting, Khrushchev pressed Nasser to lift the ban on the Communist Party, but Nasser refused, stating it was an internal matter which was not a subject of discussion with outside powers. Khrushchev was reportedly taken aback and denied he had meant to interfere in the UAR's affairs. The matter was settled as both leaders sought to prevent a rift between their two countries.

Influence on the Arab world

In Lebanon, clashes between pro-Nasser factions and supporters of staunch Nasser opponent, then-President Camille Chamoun, culminated in 1958 Lebanon crisis, civil strife by May.

The former sought to unite with the UAR, while the latter sought Lebanon's continued independence.

Nasser delegated oversight of the issue to Sarraj, who provided limited aid to Nasser's Lebanese supporters through money, light arms, and officer training—short of the large-scale support that Chamoun alleged. Nasser did not covet Lebanon, seeing it as a "special case", but sought to prevent Chamoun from a second presidential term. In Oman, the Jebel Akhdar War between the rebels in the interior of Oman against the British-backed Sultanate of Oman prompted Nasser to support the rebels in what was considered a war against colonialism between 1954 and 1959.

[Gregory Fremont Barnes: A History of Counterinsurgency]

/ref>

/ref>

On 14 July 1958, Iraqi army officers Abdel Karim Qasim and Abdel Salam Aref overthrew the Iraqi monarchy and, the next day, Iraqi prime minister and Nasser's chief Arab antagonist, Nuri al-Said, was killed.

On 14 July 1958, Iraqi army officers Abdel Karim Qasim and Abdel Salam Aref overthrew the Iraqi monarchy and, the next day, Iraqi prime minister and Nasser's chief Arab antagonist, Nuri al-Said, was killed. Relations between Nasser and Qasim grew increasingly bitter on 9 March,

Relations between Nasser and Qasim grew increasingly bitter on 9 March,Khaled Mohieddin

Khaled Mohieddine ( arz, خالد محيى الدين, ; August 17, 1922 – May 6, 2018) was an Egyptian revolutionary, politician, and military officer. As a member of the Free Officers Movement, he participated in the toppling of King Farouk ...

, who had been allowed to re-enter Egypt in 1956.

Collapse of the union and aftermath

Opposition to the union mounted among some of Syria's key elements, namely the socioeconomic, political, and military elites.

Revival on regional stage

Nasser's regional position changed unexpectedly when Yemeni officers led by Nasser supporter Abdullah al-Sallal overthrew Imam Badr of North Yemen on 27 September 1962.

Nasser's regional position changed unexpectedly when Yemeni officers led by Nasser supporter Abdullah al-Sallal overthrew Imam Badr of North Yemen on 27 September 1962. In January 1964, Nasser called for an 1964 Arab League summit (Cairo), Arab League summit in Cairo to establish a unified Arab response against Israel's plans to divert the Jordan River's waters for economic purposes, which Syria and Jordan deemed an act of war.

In January 1964, Nasser called for an 1964 Arab League summit (Cairo), Arab League summit in Cairo to establish a unified Arab response against Israel's plans to divert the Jordan River's waters for economic purposes, which Syria and Jordan deemed an act of war.

Modernization efforts and internal dissent

Al-Azhar

In 1961, Nasser sought to firmly establish Egypt as the leader of the Arab world and to promote a second revolution in Egypt with the purpose of merging Islamic and socialist thinking.

Rivalry with Amer

Following Syria's secession, Nasser grew concerned with Amer's inability to train and modernize the army, and with the state within a state Amer had created in the military command and Egyptian General Intelligence Directorate, intelligence apparatus.

National Charter and second term

In October 1961, Nasser embarked on a major nationalization program for Egypt, believing the total adoption of socialism was the answer to his country's problems and would have prevented Syria's secession.

In October 1961, Nasser embarked on a major nationalization program for Egypt, believing the total adoption of socialism was the answer to his country's problems and would have prevented Syria's secession.

Six-Day War

In mid May 1967, the Soviet Union issued warnings to Nasser of an impending Israeli attack on Syria, although Chief of Staff Mohamed Fawzi (general), Mohamed Fawzi considered the warnings to be "baseless".

In mid May 1967, the Soviet Union issued warnings to Nasser of an impending Israeli attack on Syria, although Chief of Staff Mohamed Fawzi (general), Mohamed Fawzi considered the warnings to be "baseless".

Resignation and aftermath

During the first four days of the war, the general population of the Arab world believed Arab radio station fabrications of imminent Arab victory.

During the first four days of the war, the general population of the Arab world believed Arab radio station fabrications of imminent Arab victory.Israel