Milice on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Milice française'' (French Militia), generally called ''la Milice'' (literally ''the militia'') (), was a political

Early Milice volunteers included members of France's pre-war far-right parties (such as the

Early Milice volunteers included members of France's pre-war far-right parties (such as the

The chosen emblem for the Milice carried the

The chosen emblem for the Milice carried the

Milice troops (known as ''miliciens'') wore a blue uniform jacket and trousers, a brown shirt and a wide blue

Milice troops (known as ''miliciens'') wore a blue uniform jacket and trousers, a brown shirt and a wide blue

*They are enemies in '' Medal of Honor: Underground''. *The Catholic priest Father Fehily from the

paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

organization created on 30 January 1943 by the Vichy regime

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

(with German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

aid) to help fight against the French Resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The Milice's formal head was Prime Minister Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occu ...

, although its Chief of operations and ''de facto'' leader was Secretary General Joseph Darnand. It participated in summary execution

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes include ...

s and assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

s, helping to round up Jews and ''résistants'' in France for deportation. It was the successor to Darnand's ''Service d'ordre légionnaire

The Service d'ordre légionnaire (SOL, "Legionary Order Service") was a collaborationist militia created by Joseph Darnand, a far right veteran from the First World War. Too radical even for other supporters of the Vichy regime, it was granted it ...

'' (SOL) militia. The Milice was the Vichy regime's most extreme manifestation of fascism. Ultimately, Darnand envisaged the Milice as a fascist single party

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

political movement for the French state.

The Milice frequently used torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts c ...

to extract information or confessions from those whom they interrogated. The French Resistance considered the Milice more dangerous than the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

and SS because they were native Frenchmen who understood local dialects fluently, had extensive knowledge of the towns and countryside, and knew local people and informants.

Membership

Early Milice volunteers included members of France's pre-war far-right parties (such as the

Early Milice volunteers included members of France's pre-war far-right parties (such as the Action Française

Action may refer to:

* Action (narrative), a literary mode

* Action fiction, a type of genre fiction

* Action game, a genre of video game

Film

* Action film, a genre of film

* ''Action'' (1921 film), a film by John Ford

* ''Action'' (1980 f ...

) and working-class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

men convinced of the benefits of the Vichy government's politics. In addition to ideology, incentives for joining the Milice included employment, regular pay and rations. (The latter became particularly important as the war continued, and civilian rations dwindled to near-starvation levels.) Some joined because members of their families had been killed or injured in Allied bombing raids or had been threatened, extorted or attacked by French Resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

groups. Still others joined for more mundane reasons: petty criminals were recruited by being told their sentences would be commuted if they joined the organization, and Milice volunteers were exempt from transportation to Germany as forced labour. Official figures are difficult to obtain, but several historians (including Julian T. Jackson

Julian Timothy Jackson (born 10 April 1954) is a British historian who is a fellow of the British Academy and of the Royal Historical Society. He is a professor of History at Queen Mary, University of London, he is one of the leading authorities ...

) estimate that the Milice's membership reached 25,000–30,000 by 1944. The majority of members were not full-time militiamen, but devoted only a few hours per week to their Milice activities.Matthew Feldman, 2004, Fascism: The 'fascist epoch', p. 243, The Milice had a section for full-time members, the Franc-Garde

The ''Franc-Garde'' ( en, Free Guard) was the armed wing of the French '' Milice'' (Militia), operating alone or alongside German forces in major battles against the Maquis from late 1943 to August 1944.

History

The creation of the ''Franc-Garde ...

, who were permanently mobilized and lived in barracks.

The Milice also had youth sections for boys and girls, called the ''Avant-Garde''.

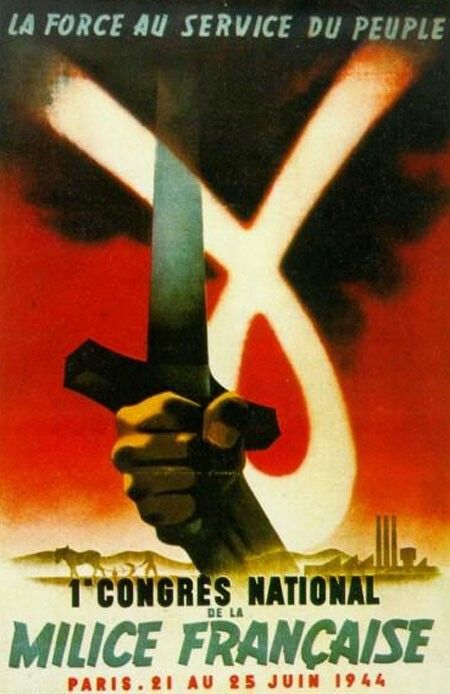

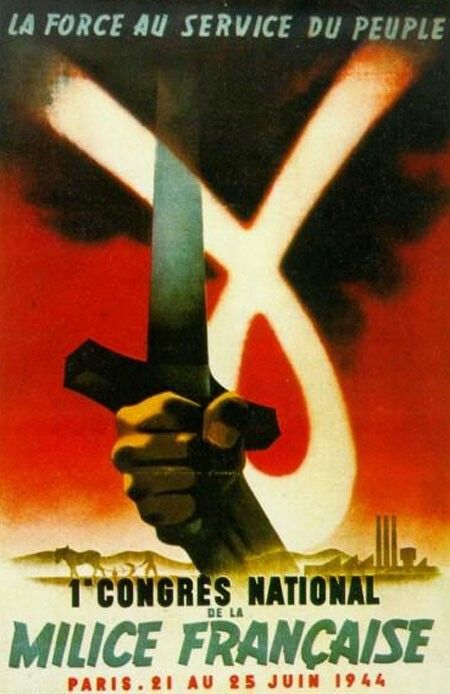

Symbols and materials

Emblem

The chosen emblem for the Milice carried the

The chosen emblem for the Milice carried the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

letter γ (gamma

Gamma (uppercase , lowercase ; ''gámma'') is the third letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals it has a value of 3. In Ancient Greek, the letter gamma represented a voiced velar stop . In Modern Greek, this letter re ...

), the symbol of the Aries

Aries may refer to:

*Aries (astrology), an astrological sign

*Aries (constellation), a constellation of stars in the zodiac

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Aries'' (album), by Luis Miguel, 1993

* ''Aries'' (EP), by Alice Chater, 2020

* "Aries" ...

astrological sign

In Western astrology, astrological signs are the twelve 30-degree sectors that make up Earth's 360-degree orbit around the Sun. The signs enumerate from the first day of spring, known as the First Point of Aries, which is the vernal equinox. ...

in the Zodiac

The zodiac is a belt-shaped region of the sky that extends approximately 8° north or south (as measured in celestial latitude) of the ecliptic, the Sun path, apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of the year. ...

, ostensibly representing rejuvenation, and replenishment of energy. The color scheme chosen was silver in blue background within a red circle for ordinary ''miliciens'', white in black background for the arm-carrying militants, and white in red background for the active combatants.

March

Their march was ''Le Chant des Cohortes''..Uniform

Milice troops (known as ''miliciens'') wore a blue uniform jacket and trousers, a brown shirt and a wide blue

Milice troops (known as ''miliciens'') wore a blue uniform jacket and trousers, a brown shirt and a wide blue beret

A beret ( or ; ; eu, txapela, ) is a soft, round, flat-crowned cap, usually of woven, hand-knitted wool, crocheted cotton, wool felt, or acrylic fibre.

Mass production of berets began in 19th century France and Spain, and the beret remains ...

. (During active paramilitary-style operations, an Adrian helmet

The Adrian helmet (french: Casque Adrian) was an influential design of combat helmet originally produced for the French Army during World War I. Its original version, the M15, was the first standard helmet of the French Army and was designed whe ...

was used, which commonly featured the emblem, either painted on or as a badge) Its newspaper was ''Combats'' (not to be confused with the underground Resistance newspaper, ''Combat

Combat ( French for ''fight'') is a purposeful violent conflict meant to physically harm or kill the opposition. Combat may be armed (using weapons) or unarmed ( not using weapons). Combat is sometimes resorted to as a method of self-defense, or ...

''). The Milice's armed forces were officially known as the ''Franc-Garde

The ''Franc-Garde'' ( en, Free Guard) was the armed wing of the French '' Milice'' (Militia), operating alone or alongside German forces in major battles against the Maquis from late 1943 to August 1944.

History

The creation of the ''Franc-Garde ...

''. Contemporary photographs show the Milice armed with a variety of weapons captured from Allied forces.

Ranks

History

Beginnings

The Resistance targeted individual for assassination, often in public areas such as cafés and streets. On 24 April 1943 they shot and killed Paul de Gassovski, a inMarseilles

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

. By late November, ''Combat

Combat ( French for ''fight'') is a purposeful violent conflict meant to physically harm or kill the opposition. Combat may be armed (using weapons) or unarmed ( not using weapons). Combat is sometimes resorted to as a method of self-defense, or ...

'' reported that 25 had been killed and 27 wounded in Resistance attacks.

Reprisals

The most prominent person killed by the Resistance wasPhilippe Henriot

Philippe Henriot (7 January 1889 – 28 June 1944) was a French poet, journalist, politician, and minister in the French government at Vichy, where he directed propaganda broadcasts. He also joined the Milice part-time.

Career

Philippe Henriot, a ...

, the Vichy regime's Minister of Information and Propaganda, who was known as "the French Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

". He was killed in his apartment in the Ministry of Information on the rue Solferino in the predawn hours of 28 June 1944 by ''résistants'' dressed as ''miliciens.'' His wife, who was in the same room, was spared. The Milice retaliated for this by killing several well-known anti-Nazi

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were ...

politicians and intellectuals (such as Victor Basch

Basch Viktor Vilém, or Victor-Guillaume Basch (18 August 1863/1865, Budapest – 10 January 1944) was a French politician and professor of germanistics and philosophy at the Sorbonne descending from Hungary. He was engaged in the Zionist move ...

) and prewar conservative leader Georges Mandel

Georges Mandel (5 June 1885 – 7 July 1944) was a French journalist, politician, and French Resistance leader.

Early life

Born Louis George Rothschild in Chatou, Yvelines, he was the son of a tailor and his wife. His family was Jewish, originally ...

.

The Milice initially operated in the former ''Zone libre

The ''zone libre'' (, ''free zone'') was a partition of the French metropolitan territory during World War II, established at the Second Armistice at Compiègne on 22 June 1940. It lay to the south of the demarcation line and was administered by ...

'' of France under the control of the Vichy regime. In January 1944, the radicalized Milice moved into what had been the ''zone occupée

The Military Administration in France (german: Militärverwaltung in Frankreich; french: Occupation de la France par l'Allemagne) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zo ...

'' of France (including Paris). They established their headquarters in the old Communist Party headquarters at 44 rue Le Peletier and at 61 rue Monceau. (The house was formerly owned by the Menier family

The Menier family of Noisiel, France, was a prominent family of chocolatiers who began as pharmaceutical manufacturers in Paris in 1816. They would build a highly successful enterprise, expanding to London, and New York City. The Menier Chocolat ...

, makers of France's best-known chocolates.) The Lycée Louis-Le-Grand

The Lycée Louis-le-Grand (), also referred to simply as Louis-le-Grand or by its acronym LLG, is a public Lycée (French secondary school, also known as sixth form college) located on rue Saint-Jacques in central Paris. It was founded in the ...

was occupied as a barracks, and an officer candidate school was established in the Auteuil Auteuil may refer to:

Places

* Auteuil, Oise, a commune in France

* Auteuil, Paris, a neighborhood of Paris

** Auteuil, Seine, the former commune which was on the outskirts of Paris

* Auteuil, Quebec, a former city that is now a district within ...

synagogue.

Notable actions

Perhaps the largest and best-known operation undertaken by the Milice was the Battle of Glières, its attempt in March 1944 to suppress the Resistance in the ''département'' ofHaute-Savoie

Haute-Savoie (; Arpitan: ''Savouè d'Amont'' or ''Hiôta-Savouè''; en, Upper Savoy) or '; it, Alta Savoia. is a department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of Southeastern France, bordering both Switzerland and Italy. Its prefecture is ...

(in southeastern France, near the Swiss border). The Milice could not overcome the Resistance, and called in German troops to complete the operation. On Bastille Day, 14 July 1944, the Franc-Garde

The ''Franc-Garde'' ( en, Free Guard) was the armed wing of the French '' Milice'' (Militia), operating alone or alongside German forces in major battles against the Maquis from late 1943 to August 1944.

History

The creation of the ''Franc-Garde ...

suppressed a revolt started by prisoners at Paris prison La Santé, killing 34 prisoners.

The legal standing of the Milice was never clarified by the Vichy government; it operated parallel to (but separate from) the Groupe mobile de réserve

The Groupes mobiles de réserve (), often referred to as GMR, were paramilitary units created by the Vichy regime during the Second World War. Their development was the special task of René Bousquet, Vichy director-general of the French national ...

and other Vichy French police forces. The Milice operated outside civilian law, and its actions were not subject to judicial review or control.

End of the war in Europe

In August 1944, as the tide of war was shifting and fearing he would be held accountable for the operations of the Milice, MarshalPhilippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of World ...

sought to distance himself from the organization by writing a harsh letter rebuking Darnand for the organization's "excesses." Darnand's response suggested that Pétain ought to have voiced his objections sooner.

After the Allied Liberation of France, French collaborators began fleeing the Allied advance in the west. During a period of unofficial reprisals immediately following on the German retreat, large numbers of ''miliciens'' were executed, either individually or in groups. Milice offices throughout France were ransacked with agents often being brutally beaten and then thrown from office windows, or into rivers before being taken to prison. At Le Grand-Bornand

Le Grand-Bornand (; frp, Bornan) is a commune in the eastern French department of Haute-Savoie. The commune is a ski resort and takes its name from the river that runs through it. The inhabitants of Le Grand-Bornand are called Bornandins.

Geo ...

French Forces of the Interior

The French Forces of the Interior (french: Forces françaises de l'Intérieur) were French resistance fighters in the later stages of World War II. Charles de Gaulle used it as a formal name for the resistance fighters. The change in designation ...

executed 76 captured members of the Milice on 24 August 1944.

Frenchmen from the German Navy

The German Navy (, ) is the navy of Germany and part of the unified ''Bundeswehr'' (Federal Defense), the German Armed Forces. The German Navy was originally known as the ''Bundesmarine'' (Federal Navy) from 1956 to 1995, when ''Deutsche Mari ...

, the National Socialist Motor Corps

The National Socialist Motor Corps (german: Nationalsozialistisches Kraftfahrkorps, NSKK) was a paramilitary organization of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) that officially existed from May 1931 to 1945. The group was a successor organisation to the old ...

(NSKK), the Organisation Todt

Organisation Todt (OT; ) was a civil and military engineering organisation in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945, named for its founder, Fritz Todt, an engineer and senior Nazi. The organisation was responsible for a huge range of engineering projec ...

and the Milice security police became part of a new unit known as the Waffen Grenadier Brigade of the SS Charlemagne (''Waffen-Grenadier-Brigade der SS Charlemagne''). The unit also included some remaining personnel from the disband Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism

The Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism (french: Légion des volontaires français contre le bolchévisme, LVF) was a unit of the German Army during World War II consisting of collaborationist volunteers from France. Officially design ...

(LVF) and the SS-Volunteer ''Sturmbrigade'' France (SS-Freiwilligen Sturmbrigade "Frankreich"). Later in February 1945, the unit was renamed the Charlemagne Division

The Waffen Grenadier Brigade of the SS Charlemagne (german: Waffen-Grenadier-Brigade der SS "Charlemagne") was a Waffen-SS unit formed in September 1944 from French collaborationists, many of whom were already serving in various other German un ...

of the Waffen-SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscripts from both occup ...

. At this time it had a strength of 7,340 men; 1,200 men from the LVF, 1,000 from the ''Sturmbrigade'', 2,500 from the Milice, 2,000 from the NSKK and 640 were former ''Kriegsmarine'' and naval police.

Aftermath

An unknown number of ''miliciens'' managed to escape prison or execution, either by going underground or fleeing abroad. A few were later prosecuted. The most notable of these wasPaul Touvier

Paul Claude Marie Touvier (3 April 1915 – 17 July 1996) was a French Nazi collaborator during World War II in Occupied France. In 1994, he became the first Frenchman ever convicted of crimes against humanity, for his participation in the Ho ...

, the former commander of the Milice in Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of t ...

. In 1994, he was convicted of ordering the retaliatory execution of seven Jews at Rillieux-la-Pape

Rillieux-la-Pape () is a commune in the Metropolis of Lyon in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of central-eastern France. In 2017, it had a population of 30,012.

Population

Climate

Twin cities

Rillieux-la-Pape is twinned with three cities: ...

. He died in prison two years later.

In popular culture

*Since the war, the term ''milice'' has acquired a derogatory meaning inFrance

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

.

*The French hard rock ensemble Trust

Trust often refers to:

* Trust (social science), confidence in or dependence on a person or quality

It may also refer to:

Business and law

* Trust law, a body of law under which one person holds property for the benefit of another

* Trust (bus ...

had a hit named "Police Milice", where its frontman Bernard Bonvoisin compared modern-day police officer

A police officer (also called a policeman and, less commonly, a policewoman) is a warranted law employee of a police force. In most countries, "police officer" is a generic term not specifying a particular rank. In some, the use of the ...

s to the Milice.

*Louis Malle

Louis Marie Malle (; 30 October 1932 – 23 November 1995) was a French film director, screenwriter, and producer who worked in both Cinema of France, French cinema and Cinema of the United States, Hollywood. Described as "eclectic" and "a fi ...

's films ''Lacombe, Lucien

''Lacombe, Lucien'' is a 1974 French war drama film by Louis Malle about a French teenage boy during the German occupation of France in World War II.

Plot

In June 1944, as the Allies are fighting the Germans in Normandy, Lucien Lacombe, a 17-y ...

'' and ''Au revoir les enfants

''Au revoir les enfants'' (, meaning "Goodbye, Children") is an autobiographical 1987 film written, produced and directed by Louis Malle. It is based on the actions of Père Jacques, a French priest and headmaster who attempted to shelter Jewish ...

'' include the Milice as part of the plot.

*The 2003 drama '' The Statement'', directed by Norman Jewison

Norman Frederick Jewison (born July 21, 1926) is a retired Canadian film and television director, producer, and founder of the Canadian Film Centre.

He has directed numerous feature films and has been nominated for the Academy Award for Best D ...

and starring Michael Caine

Sir Michael Caine (born Maurice Joseph Micklewhite; 14 March 1933) is an English actor. Known for his distinctive Cockney accent, he has appeared in more than 160 films in a career spanning seven decades, and is considered a British film ico ...

, was adapted from the 1996 novel by the same name by Brian Moore. He shaped it from the story of Paul Touvier

Paul Claude Marie Touvier (3 April 1915 – 17 July 1996) was a French Nazi collaborator during World War II in Occupied France. In 1994, he became the first Frenchman ever convicted of crimes against humanity, for his participation in the Ho ...

, a Vichy French Milice official who hid for years (often sheltered by the Catholic Church) and was indicted in 1991 for war crimes. Both he and the film character had supervised a mass murder of Jews.

* The film '' Female Agents'' (french: Les Femmes de l'ombre), set during World War II, has a scene where two of the female agents walk past a recruitment poster for the Milice which says "Against Communism / French Militia / Secretary-General Joseph Darnand".

*In the ''Doctor Who

''Doctor Who'' is a British science fiction television series broadcast by the BBC since 1963. The series depicts the adventures of a Time Lord called the Doctor, an extraterrestrial being who appears to be human. The Doctor explores the u ...

'' audio story '' Resistance'', the Doctor

Doctor or The Doctor may refer to:

Personal titles

* Doctor (title), the holder of an accredited academic degree

* A medical practitioner, including:

** Physician

** Surgeon

** Dentist

** Veterinary physician

** Optometrist

*Other roles

** ...

and Polly

Polly is a given name, most often feminine, which originated as a variant of Molly (name), Molly (a diminutive of Mary (name), Mary). Polly may also be a short form of names such as Polina (given name), Polina, Polona (given name), Polona, Paula (g ...

have to evade the Milice in 1944.

*They feature prominently in the popular French TV series ''Un Village Français

''Un village français'' (''A French Village'') is a French television drama series created by chief writer Frédéric Krivine and principal director Philippe Triboit, with the assistance of historical consultant Jean-Pierre Azéma. It is set i ...

'' which covers the whole period of the occupation and liberation and was broadcast in France and extensively internationall*They are enemies in '' Medal of Honor: Underground''. *The Catholic priest Father Fehily from the

Ross O'Carroll-Kelly

Ross O'Carroll-Kelly is a satirical fictional Irish character, a wealthy South County Dublin rugby union jock created by journalist Paul Howard. The character first appeared in a January 1998 column in the ''Sunday Tribune'' newspaper and late ...

series of novels is revealed to have served in the Milice as a young man, in the novel '' Should Have Got Off at Sydney Parade'' (2007).

See also

;Axis *Lorenzen Group

The Lorenzen group ( Danish: ''Lorenzengruppen'') was an armed paramilitary group of Danish collaborators, subordinate to the HIPO Corps, which was active during the period December 1944 - May 1945.

The group is named after its founder Jørgen ...

– Danish pro-German paramilitary group

*Security Battalions

The Security Battalions ( el, Τάγματα Ασφαλείας, Tagmata Asfaleias, derisively known as ''Germanotsoliades'' (Γερμανοτσολιάδες) or ''Tagmatasfalites'' (Ταγματασφαλίτες)) were Greek Collaboration with ...

– Greek pro-German paramilitary group

*Carlingue

The Carlingue (or French Gestapo) were French auxiliaries who worked for the Gestapo, Sicherheitsdienst and Geheime Feldpolizei during the German occupation of France in the Second World War.

The group, which was based at 93 rue Lauriston in th ...

– the French version of the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

.

*Special Brigades

During the Second World War, the Special Brigades (french: Brigades spéciales, or BS) were a French police force in Vichy France specializing in tracking down "internal enemies" (i.e. French Resistance workers), dissidents, escaped prisoners, Jew ...

– Paramilitary sections of the Vichy Police service.

*Geheime Feldpolizei

The ''Geheime Feldpolizei'', short: ''GFP'' (), , was the secret military police of the German Wehrmacht until the end of the Second World War (1945). Its units carried out plain-clothed security work in the field - such as counter-espionage, ...

– the secret military police of the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

'' that worked alongside the Milice

;Allies

*Maquis des Glières

The Maquis des Glières was a Free French Resistance group, which fought against the 1940–1944 German occupation of France in World War II. The name is also given to the military conflict that opposed Resistance fighters to German, Vichy and ...

– resistance group

*Maquis du Vercors

The Battle of Vercors in July and August 1944 was between a rural group of the French Forces of the Interior (FFI) maquis''] and the armed forces of Nazi Germany which had occupied France since 1940 in the Second World War. The maquis used the pro ...

– resistance group

References

Further reading

* Cullen, Stephen M., Stacey, Mark, (2018) ''World War II Vichy French Security Troops'', Osprey Publishing. * * * * * {{Authority control Far-right politics in France National security institutions Political repression in France Defunct law enforcement agencies of France French collaboration during World War II Military of Vichy France Paramilitary organizations based in France 1943 establishments in France 1944 disestablishments in France Police misconduct in France Collaboration with the Axis Powers Political parties of the Vichy regime Fascist organizations Pierre Laval