Messiaen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

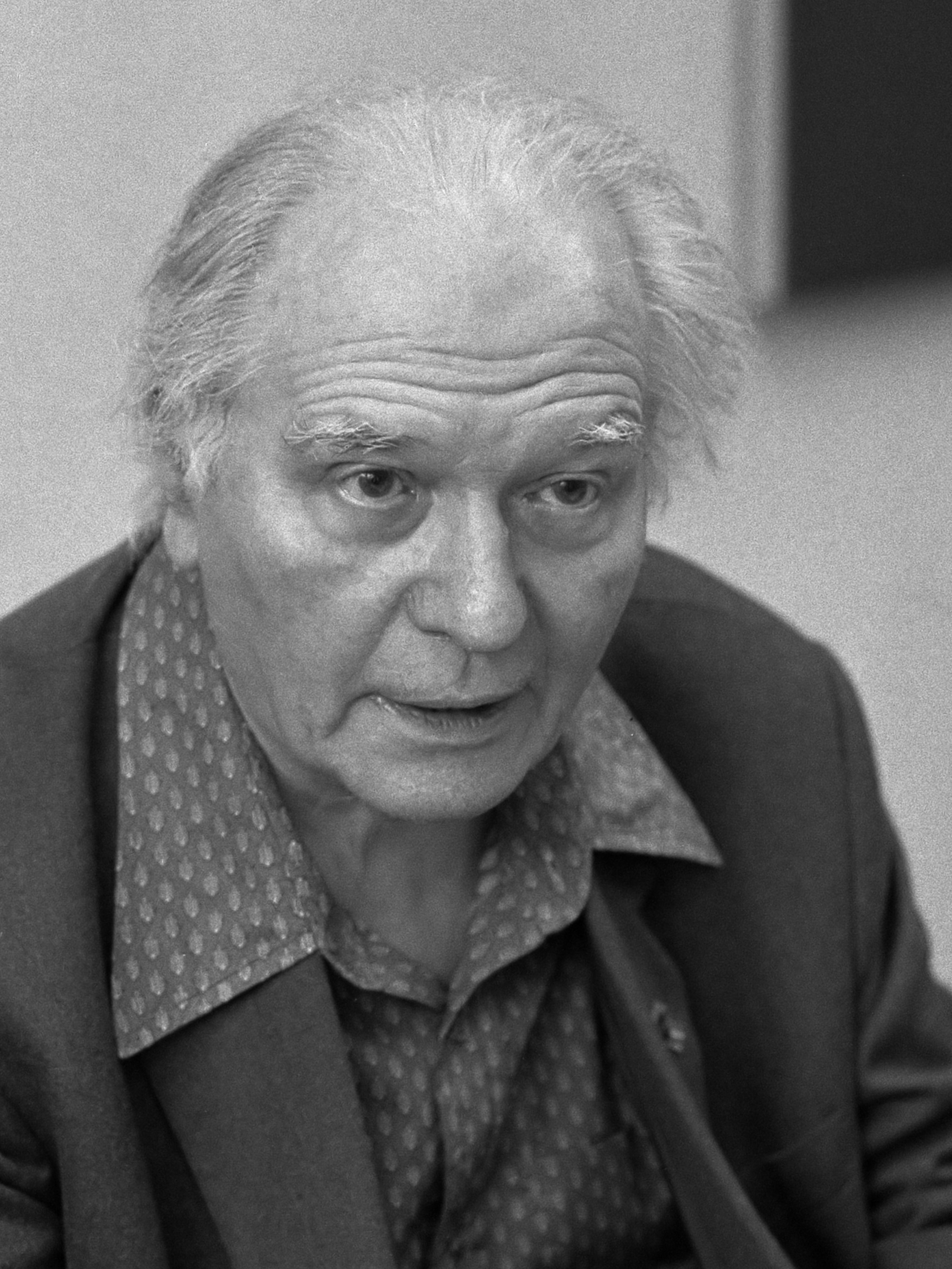

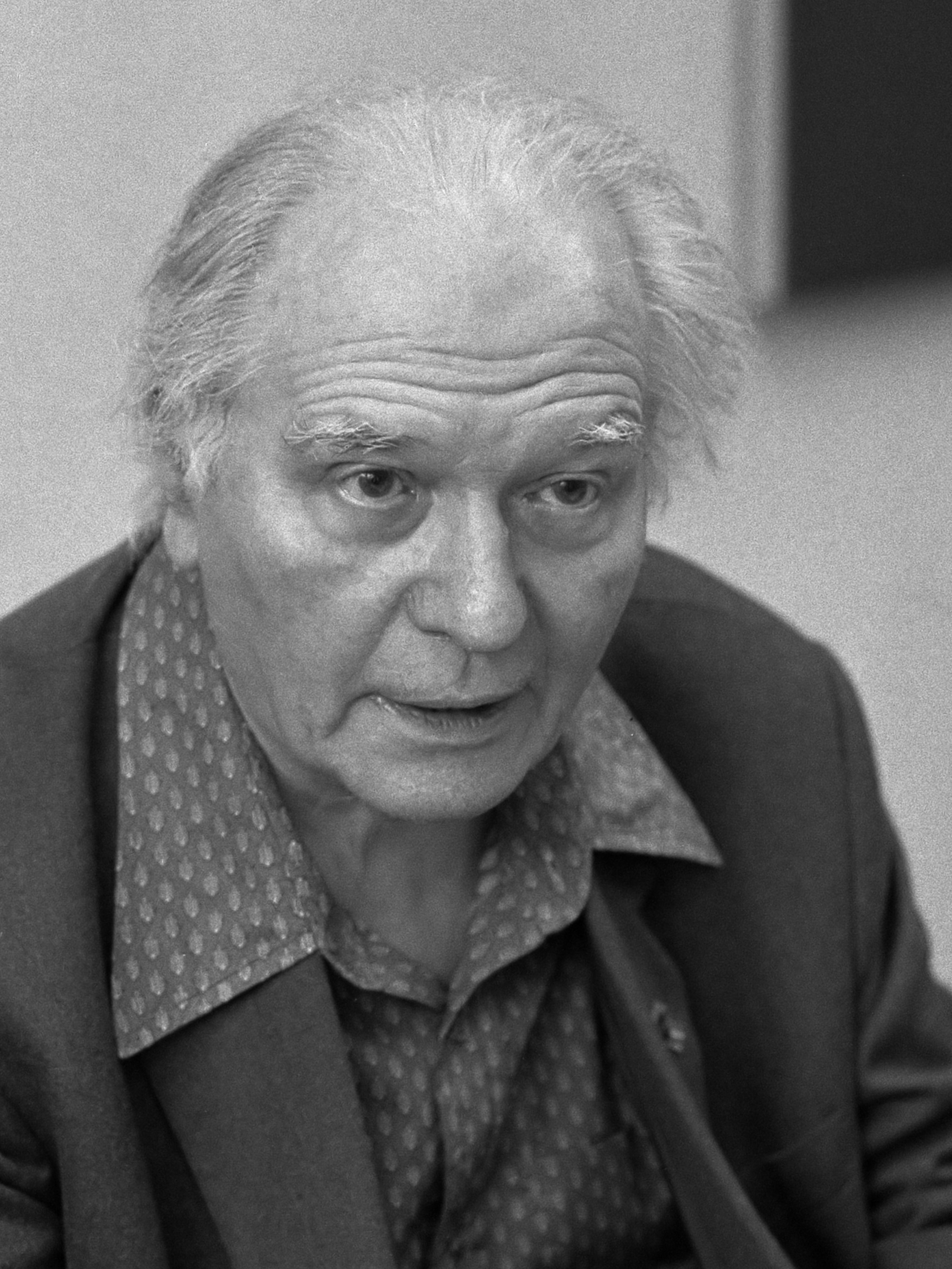

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen was born on 10 December 1908 at 20 Boulevard Sixte-Isnard in

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen was born on 10 December 1908 at 20 Boulevard Sixte-Isnard in  Messiaen made excellent academic progress at the Paris Conservatoire. In 1924, aged 15, he was awarded second prize in

Messiaen made excellent academic progress at the Paris Conservatoire. In 1924, aged 15, he was awarded second prize in

In the autumn of 1927, Messiaen joined Dupré's organ course. Dupré later wrote that Messiaen, having never seen an organ console, sat quietly for an hour while Dupré explained and demonstrated the instrument, and then came back a week later to play

In the autumn of 1927, Messiaen joined Dupré's organ course. Dupré later wrote that Messiaen, having never seen an organ console, sat quietly for an hour while Dupré explained and demonstrated the instrument, and then came back a week later to play  In response to a commission for a piece to accompany light-and-water shows on

In response to a commission for a piece to accompany light-and-water shows on

Messiaen's first wife died in 1959 after a long illness, and in 1961 he married Loriod. He began to travel widely, to attend musical events and to seek out and transcribe the songs of more exotic birds in the wild. Despite this, he only spoke French. Loriod frequently assisted her husband's detailed studies of birdsong while walking with him, by making tape recordings for later reference. In 1962 he visited Japan, where Gagaku music and

Messiaen's first wife died in 1959 after a long illness, and in 1961 he married Loriod. He began to travel widely, to attend musical events and to seek out and transcribe the songs of more exotic birds in the wild. Despite this, he only spoke French. Loriod frequently assisted her husband's detailed studies of birdsong while walking with him, by making tape recordings for later reference. In 1962 he visited Japan, where Gagaku music and

In 1971, he was asked to compose a piece for the

In 1971, he was asked to compose a piece for the

"The Social and Aesthetic Situation of Olivier Messiaen's Religious Music: Turangalîla Symphonie."

''International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music'' 43/1:53–70. * Benitez, Vincent P. (2000). "A Creative Legacy: Messiaen as Teacher of Analysis." ''College Music Symposium'' 40: 117–39. * Benitez, Vincent P. (2001). "Pitch Organization and Dramatic Design in ''Saint François d'Assise'' of Olivier Messiaen." PhD diss., Bloomington: Indiana University. * Benitez, Vincent P. (2002). "Simultaneous Contrast and Additive Designs in Olivier Messiaen's Opera ''Saint François d'Assise''." ''Music Theory Online'' 8.2 (August 2002)

Music Theory Online

* Benitez, Vincent P. (2004). "Aspects of Harmony in Messiaen's Later Music: An Examination of the Chords of Transposed Inversions on the Same Bass Note." ''Journal of Musicological Research'' 23, no. 2: 187–226. * Benitez, Vincent P. (2004). "Narrating Saint Francis's Spiritual Journey: Referential Pitch Structures and Symbolic Images in Olivier Messiaen's ''Saint François d'Assise''." In ''Poznan Studies on Opera'', edited by Maciej Jablonski, 363–411. * Benitez, Vincent P. (2008). "Messiaen as Improviser." ''Dutch Journal of Music Theory'' 13, no. 2 (May 2008): 129–44. * Benitez, Vincent P. (2009). "Reconsidering Messiaen as Serialist." ''Music Analysis'' 28, nos. 2–3 (2009): 267–99 (published 21 April 2011). * Benitez, Vincent P. (2010). "Messiaen and Aquinas." In ''Messiaen the Theologian'', edited by Andrew Shenton, 101–26. Aldershot: Ashgate. * Benítez, Vincent Pérez (2019). ''Olivier Messiaen's Opera, Saint François d'Assise''. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. . * Boivin, Jean (1993). "La Classe de Messiaen: Historique, reconstitution, impact". Ph.D. diss. Montreal: Ecole Polytechnique, Montreal. * Boswell-Kurc, Lilise (2001). "Olivier Messiaen's Religious War-Time Works and Their Controversial Reception in France (1941–1946) ". Ph.D. diss. New York: New York University. * * * Burns, Jeffrey Phillips (1995). "Messiaen's Modes of Limited Transposition Reconsidered". M.M. thesis, Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison. * Cheong Wai-Ling (2003). "Messiaen's Chord Tables: Ordering the Disordered". ''Tempo'' 57, no. 226 (October): 2–10. * Cheong Wai-Ling (2008). "Neumes and Greek Rhythms: The Breakthrough in Messiaen's Birdsong". ''Acta Musicologica'' 80, no. 1:1–32. * Dingle, Christopher (2013). ''Messiaen's Final Works''. Farnham, UK: Ashgate. . * Fallon, Robert Joseph (2005). "Messiaen's Mimesis: The Language and Culture of The Bird Styles". Ph.D. diss. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley. * Fallon, Robert (2008). "Birds, Beasts, and Bombs in Messiaen's Cold War Mass". ''The Journal of Musicology'' 26, no. 2 (Spring): 175–204. * * * Hardink, Jason M. (2007). "Messiaen and Plainchant". D.M.A. diss. Houston: Rice University. * Harris, Joseph Edward (2004). "Musique coloree: Synesthetic Correspondence in the Works of Olivier Messiaen". Ph.D. diss. Ames: The University of Iowa. * Hill, Matthew Richard (1995). "Messiaen's ''Regard du silence'' as an Expression of Catholic Faith". D.M.A. diss. Madison: The University of Wisconsin, Madison. * Laycock, Gary Eng Yeow (2010). "Re-evaluating Olivier Messiaen's Musical Language from 1917 to 1935". Ph.D. diss. Bloomington: Indiana University, 2010. * Luchese, Diane (1998). "Olivier Messiaen's Slow Music: Glimpses of Eternity in Time". Ph.D. diss. Evanston: Northwestern University * McGinnis, Margaret Elizabeth (2003). "Playing the Fields: Messiaen, Music, and the Extramusical". Ph.D. diss. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. * Nelson, David Lowell (1992). "An Analysis of Olivier Messiaen's Chant Paraphrases". 2 vols. Ph.D. diss. Evanston: Northwestern University * Ngim, Alan Gerald (1997). "Olivier Messiaen as a Pianist: A Study of Tempo and Rhythm Based on His Recordings of ''Visions de l'amen''". D.M.A. diss. Coral Gables: University of Miami. * Peterson, Larry Wayne (1973). "Messiaen and Rhythm: Theory and Practice". Ph.D. diss. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill * Puspita, Amelia (2008). "The Influence of Balinese Gamelan on the Music of Olivier Messiaen". D.M.A. diss. Cincinnati: University of Cincinnati * * *Schultz, Rob (2008). "Melodic Contour and Nonretrogradable Structure in the Birdsong of Olivier Messiaen". ''Music Theory Spectrum'' 30, no. 1 (Spring): 89–137. * Shenton, Andrew (1998). "The Unspoken Word: Olivier Messiaen's 'langage communicable'". Ph.D. diss. Cambridge: Harvard University. * * * * Simeone, Nigel (2004). "'Chez Messiaen, tout est priére': Messiaen's Appointment at the Trinité". ''The Musical Times'' 145, no. 1889 (Winter): 36–53. * Simeone, Nigel (2008). "Messiaen, Koussevitzky and the USA". ''The Musical Times'' 149, no. 1905 (Winter): 25–44. * * Welsh Ibanez, Deborah (2005). Color, Timbre, and Resonance: Developments in Olivier Messiaen's Use of Percussion Between 1956–1965. D.M.A. diss. Coral Gables: University of Miami * Zheng, Zhong (2004). A Study of Messiaen's Solo Piano Works. Ph.D. diss. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

BFI database entry

/ref> *''Olivier Messiaen et les oiseaux'' (1973). Directed by Michel Fano and Denise Tual. *''Olivier Messiaen – The Crystal Liturgy'' (2007 VD release date. Directed by Olivier Mille. *''Olivier Messiaen: Works'' (1991). DVD on which Messiaen performs "Improvisations" on the organ at the Paris Trinity Church. *''The South Bank Show: Olivier Messiaen: The Music of Faith'' (1985). Directed by Alan Benson

BFI database entry

*''Quartet for the End of Time'', with the President's Own Marine Band Ensemble, A Film by H. Paul Moon

"Messiaen, Olivier" in ''Oxford Music Online'' (by subscription)BBC Messiaen Profileoliviermessiaen.org

Up to date website by Malcolm Ball, includes the latest recordings and concerts, a comprehensive bibliography, photos, analyses and reviews, a very extensive bio of Yvonne Loriod with discography, and more.

oliviermessiaen.net

hosted by the Boston University Messiaen Project UMP Includes detailed information on the composer's life and works, events, and links to other Messiaen websites.

www.philharmonia.co.uk/messiaen

the Philharmonia Orchestra's Messiaen website. The site contains articles, unseen images, programme notes and films to go alongside the orchestra's series of concerts celebrating the Centenary of Olivier Messiaen's birth.

Music for the End of Time

David Schiff article in ''

Music and the Holocaust – Olivier Messiaen

*

My Messiaen Modes

A visual representation of Messiaen's modes of limited transposition.

Martina Trumpp

violin an

Bohumir Stehlik

piano

Thème et variations

– Helen Kim, violin; Adam Bowles, pian

Luna Nova New Music EnsembleLe merle noir

– John McMurtery, flute; Adam Bowles, pian

Luna Nova New Music EnsembleQuatuor pour la fin du temps

�

Luna Nova New Music Ensemble''Regard de l'esprit de joie'' from ''Vingt regards...''

Tom Poster, pianist * played on a Mühleisen pipe organ

In-depth feature on Olivier Messiaen by Radio France International's English service

* b

Ukho Ensemble Kyiv

* Olivier Messiaen

''Le Banquet Céleste''

(1928). Andrew Pink (2021

Exordia ad missam

{{DEFAULTSORT:Messiaen, Olivier 1908 births 1992 deaths 20th-century classical composers Conservatoire de Paris alumni Conservatoire de Paris faculty Academics of the École Normale de Musique de Paris Composers for piano Composers for pipe organ EMI Classics and Virgin Classics artists Ernst von Siemens Music Prize winners French classical composers French male classical composers French classical organists French male organists French composers of sacred music French military personnel of World War II French ornithologists Deutsche Grammophon artists French Roman Catholics Kyoto laureates in Arts and Philosophy Members of the Académie des beaux-arts Modernist composers Occitan musicians Organ improvisers Musicians from Avignon Pupils of Maurice Emmanuel Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medallists Schola Cantorum de Paris faculty Wolf Prize in Arts laureates World War II prisoners of war held by Germany Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur Commanders of the Order of the Crown (Belgium) Recipients of the Léonie Sonning Music Prize 20th-century French composers 20th-century French male musicians Male classical organists

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and ornithologist

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the "methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them." Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and th ...

who was one of the major composers of the 20th century

The 20th (twentieth) century began on

January 1, 1901 ( MCMI), and ended on December 31, 2000 ( MM). The 20th century was dominated by significant events that defined the modern era: Spanish flu pandemic, World War I and World War II, nuclear ...

. His music is rhythm

Rhythm (from Greek , ''rhythmos'', "any regular recurring motion, symmetry") generally means a " movement marked by the regulated succession of strong and weak elements, or of opposite or different conditions". This general meaning of regular recu ...

ically complex; harmonically

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. However, ...

and melodically

A melody (from Greek μελῳδία, ''melōidía'', "singing, chanting"), also tune, voice or line, is a linear succession of musical tones that the listener perceives as a single entity. In its most literal sense, a melody is a combinat ...

he employs a system he called ''modes of limited transposition Modes of limited transposition are musical modes or scales that fulfill specific criteria relating to their symmetry and the repetition of their interval groups. These scales may be transposed to all twelve notes of the chromatic scale, but at leas ...

'', which he abstracted from the systems of material generated by his early compositions and improvisations. He wrote music for chamber ensembles and orchestra, vocal music, as well as for solo organ and piano, and also experimented with the use of novel electronic instruments developed in Europe during his lifetime.

Messiaen entered the Paris Conservatoire

The Conservatoire de Paris (), also known as the Paris Conservatory, is a college of music and dance founded in 1795. Officially known as the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris (CNSMDP), it is situated in the avenue ...

at the age of 11 and studied with Paul Dukas

Paul Abraham Dukas ( or ; 1 October 1865 – 17 May 1935) was a French composer, critic, scholar and teacher. A studious man of retiring personality, he was intensely self-critical, having abandoned and destroyed many of his compositions. His b ...

, Maurice Emmanuel, Charles-Marie Widor

Charles-Marie-Jean-Albert Widor (21 February 1844 – 12 March 1937) was a French organist, composer and teacher of the mid-Romantic era, most notable for his ten organ symphonies. His Toccata from the fifth organ symphony has become one of th ...

and Marcel Dupré

Marcel Jean-Jules Dupré () (3 May 1886 – 30 May 1971) was a French organist, composer, and pedagogue.

Biography

Born in Rouen into a wealthy musical family, Marcel Dupré was a child prodigy. His father Aimable Albert Dupré was titular o ...

, among others. He was appointed organist at the Église de la Sainte-Trinité, Paris, in 1931, a post held for 61 years until his death. He taught at the Schola Cantorum de Paris

The Schola Cantorum de Paris is a private conservatory in Paris. It was founded in 1894 by Charles Bordes, Alexandre Guilmant and Vincent d'Indy as a counterbalance to the Paris Conservatoire's emphasis on opera.

History

La Schola was founded i ...

during the 1930s. After the fall of France in 1940, Messiaen was interned for nine months in the German prisoner of war camp Stalag VIII-A

Stalag VIII-A was a German World War II prisoner-of-war camp, located just to the south of the town of Görlitz in Lower Silesia, east of the River Neisse. The location of the camp lies in today's Polish town of Zgorzelec, which lies over the riv ...

, where he composed his ("Quartet for the end of time") for the four instruments available in the prison—piano, violin, cello and clarinet. The piece was first performed by Messiaen and fellow prisoners for an audience of inmates and prison guards. He was appointed professor of harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. However ...

soon after his release in 1941 and professor of composition in 1966 at the Paris Conservatoire, positions that he held until his retirement in 1978. His many distinguished pupils included Iannis Xenakis

Giannis Klearchou Xenakis (also spelled for professional purposes as Yannis or Iannis Xenakis; el, Γιάννης "Ιωάννης" Κλέαρχου Ξενάκης, ; 29 May 1922 – 4 February 2001) was a Romanian-born Greek-French avant-garde ...

, George Benjamin, Alexander Goehr, Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music.

Born in Mont ...

, Tristan Murail

Tristan Murail (born 11 March 1947) is a French composer associated with the "spectral" technique of composition. Among his compositions is the large orchestral work ''Gondwana''.

Early life and studies

Murail was born in Le Havre, France. His fa ...

, Karlheinz Stockhausen

Karlheinz Stockhausen (; 22 August 1928 – 5 December 2007) was a German composer, widely acknowledged by critics as one of the most important but also controversial composers of the 20th and early 21st centuries. He is known for his groun ...

, and Yvonne Loriod

Yvonne Louise Georgette Loriod-Messiaen (; 20 January 1924 – 17 May 2010) was a French pianist, teacher, and composer, and the second wife of composer Olivier Messiaen. Her sister was the Ondes Martenot player Jeanne Loriod.

Biography

Loriod ...

, who became his second wife.

Messiaen perceived colours when he heard certain musical chords (a phenomenon known as synaesthesia); according to him, combinations of these colours were important in his compositional process. He travelled widely and wrote works inspired by diverse influences, including Japanese music

In Japan, music includes a wide array of distinct genres, both traditional and modern. The word for "music" in Japanese is 音楽 (''ongaku''), combining the kanji 音 ''on'' (sound) with the kanji 楽 ''gaku'' (music, comfort). Japan is the world ...

, the landscape of Bryce Canyon

Bryce Canyon National Park () is an American national park located in southwestern Utah. The major feature of the park is Bryce Canyon, which despite its name, is not a canyon, but a collection of giant natural amphitheaters along the eastern ...

in Utah, and the life of St. Francis of Assisi

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, better known as Saint Francis of Assisi ( it, Francesco d'Assisi; – 3 October 1226), was a mystic Italian Catholic friar, founder of the Franciscans, and one of the most venerated figures in Christianit ...

. For a short period Messiaen experimented with the parametrisation associated with "total serialism", in which field he is often cited as an innovator. His style absorbed many global musical influences such as Indonesian gamelan

Gamelan () ( jv, ꦒꦩꦼꦭꦤ꧀, su, ᮌᮙᮨᮜᮔ᮪, ban, ᬕᬫᭂᬮᬦ᭄) is the traditional ensemble music of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese peoples of Indonesia, made up predominantly of percussive instruments. T ...

(tuned percussion often features prominently in his orchestral works).

He found birdsong

Bird vocalization includes both bird calls and bird songs. In non-technical use, bird songs are the bird sounds that are melodious to the human ear. In ornithology and birding, songs (relatively complex vocalizations) are distinguished by func ...

fascinating, notating bird songs worldwide and incorporating birdsong transcriptions into his music. His innovative use of colour, his conception of the relationship between time and music, and his use of birdsong are among the features that make Messiaen's music distinctive.

Biography

Youth and studies

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen was born on 10 December 1908 at 20 Boulevard Sixte-Isnard in

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen was born on 10 December 1908 at 20 Boulevard Sixte-Isnard in Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label=Provençal dialect, Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse Departments of France, department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region of So ...

, France, into a literary family. He was the elder of two sons of Cécile Anne Marie Antoinette Sauvage, a poet, and Pierre Léon Joseph Messiaen, a scholar and teacher of English from a farm near Wervicq-Sud

Wervicq-Sud (; ) is a commune in the Nord department of northern France, near the border with Belgium. Wervicq-Sud is one of the oldest villages still existent, dating back to Roman times.

The town is separated from its Belgian Flemish sister t ...

who translated the plays of William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

into French. Messiaen's mother published a sequence of poems, ("The Budding Soul"), the last chapter of ("As the Earth Turns"), which address her unborn son. Messiaen later said this sequence of poems influenced him deeply and he cited it as prophetic of his future artistic career. His brother Alain André Prosper Messiaen, four years his junior, was also a poet.

At the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Pierre enlisted and Cécile took their two boys to live with her brother in Grenoble

lat, Gratianopolis

, commune status = Prefecture and commune

, image = Panorama grenoble.png

, image size =

, caption = From upper left: Panorama of the city, Grenoble’s cable cars, place Saint- ...

. There Messiaen became fascinated with drama, reciting Shakespeare to his brother with the help of a home-made toy theatre with translucent backdrops made from old cellophane

Cellophane is a thin, transparent sheet made of regenerated cellulose. Its low permeability to air, oils, greases, bacteria, and liquid water makes it useful for food packaging. Cellophane is highly permeable to water vapour, but may be coated ...

wrappers. At this time he also adopted the Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

faith. Later, Messiaen felt most at home in the Alps of the Dauphiné

The Dauphiné (, ) is a former province in Southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of Isère, Drôme and Hautes-Alpes. The Dauphiné was originally the Dauphiné of Viennois.

In the 12th centu ...

, where he had a house built south of Grenoble where he composed most of his music.

He took piano lessons, having already taught himself to play. His interests included the recent music of French composers Claude Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influential composers of the ...

and Maurice Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In ...

, and he asked for opera vocal scores for Christmas presents. He also saved to buy scores and one such was Edvard Grieg

Edvard Hagerup Grieg ( , ; 15 June 18434 September 1907) was a Norwegian composer and pianist. He is widely considered one of the foremost Romantic era composers, and his music is part of the standard classical repertoire worldwide. His use of ...

's ''Peer Gynt

''Peer Gynt'' (, ) is a five- act play in verse by the Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen published in 1876. Written in Norwegian, it is one of the most widely performed Norwegian plays. Ibsen believed ''Per Gynt'', the Norwegian fairy tale on wh ...

'' whose "beautiful Norwegian melodic lines with the taste of folk song ... gave me a love of melody." Around this time he began to compose. In 1918 his father returned from the war and the family moved to Nantes

Nantes (, , ; Gallo: or ; ) is a city in Loire-Atlantique on the Loire, from the Atlantic coast. The city is the sixth largest in France, with a population of 314,138 in Nantes proper and a metropolitan area of nearly 1 million inhabita ...

. He continued music lessons; one of his teachers, Jehan de Gibon, gifted him a score of Debussy's opera , which Messiaen described as "a thunderbolt" and "probably the most decisive influence on me". The following year Pierre Messiaen gained a teaching post at Sorbonne University

Sorbonne University (french: Sorbonne Université; la Sorbonne: 'the Sorbonne') is a public research university located in Paris, France. The institution's legacy reaches back to 1257 when Sorbonne College was established by Robert de Sorbon ...

in Paris. Messiaen entered the Paris Conservatoire

The Conservatoire de Paris (), also known as the Paris Conservatory, is a college of music and dance founded in 1795. Officially known as the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris (CNSMDP), it is situated in the avenue ...

in 1919, aged 11.

Messiaen made excellent academic progress at the Paris Conservatoire. In 1924, aged 15, he was awarded second prize in

Messiaen made excellent academic progress at the Paris Conservatoire. In 1924, aged 15, he was awarded second prize in harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. However ...

, having been taught in that subject by professor Jean Gallon. In 1925, he won first prize in piano accompaniment

Accompaniment is the musical part which provides the rhythmic and/or harmonic support for the melody or main themes of a song or instrumental piece. There are many different styles and types of accompaniment in different genres and styles ...

, and in 1926 he gained first prize in fugue

In music, a fugue () is a contrapuntal compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the c ...

. After studying with Maurice Emmanuel, he was awarded second prize for the history of music in 1928. Emmanuel's example engendered an interest in ancient Greek rhythms and exotic modes.Sherlaw Johnson (1975), p. 10 After showing improvisation

Improvisation is the activity of making or doing something not planned beforehand, using whatever can be found. Improvisation in the performing arts is a very spontaneous performance without specific or scripted preparation. The skills of impr ...

al skills on the piano Messiaen studied organ with Marcel Dupré. Messiaen gained first prize in organ playing and improvisation in 1929. After a year studying composition with Charles-Marie Widor, in autumn 1927 he entered the class of the newly appointed Paul Dukas. Messiaen's mother died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

shortly before the class began. Despite his grief, he resumed his studies, and in 1930 Messiaen won first prize in composition.

While a student he composed his first published works—his eight '' Préludes'' for piano (the earlier '' Le banquet céleste'' was published subsequently). These exhibit Messiaen's use of his modes of limited transposition and palindromic

A palindrome is a word, number, phrase, or other sequence of symbols that reads the same backwards as forwards, such as the words ''madam'' or ''racecar'', the date and time ''11/11/11 11:11,'' and the sentence: "A man, a plan, a canal – Pana ...

rhythms (Messiaen called these '' non-retrogradable rhythms''). His official début came in 1931 with his orchestral suite ''Les offrandes oubliées''. That year he first heard a gamelan

Gamelan () ( jv, ꦒꦩꦼꦭꦤ꧀, su, ᮌᮙᮨᮜᮔ᮪, ban, ᬕᬫᭂᬮᬦ᭄) is the traditional ensemble music of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese peoples of Indonesia, made up predominantly of percussive instruments. T ...

group, sparking his interest in the use of tuned percussion.

La Trinité, ''La jeune France'', and Messiaen's war

Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard w ...

's '' Fantasia in C minor'' to an impressive standard. From 1929, Messiaen regularly deputised at the Église de la Sainte-Trinité, Paris, for the ailing Charles Quef

Charles Paul Florimond Quef (1 November 1873, Lille – 2 July 1931, Paris) was a French organist and composer.

He studied at the conservatory in Lille, and later he attended the Paris Conservatory where he studied with Charles-Marie Widor, L ...

. The post became vacant in 1931 when Quef died, and Dupré, Charles Tournemire

Charles Arnould Tournemire (22 January 1870 – 3 or 4 November 1939) was a French composer and organist, notable partly for his improvisations, which were often rooted in the music of Gregorian chant. His compositions include eight symphoni ...

and Widor among others supported Messiaen's candidacy. His formal application included a letter of recommendation from Widor. The appointment was confirmed in 1931, and he remained the organist at the church for more than 60 years. He also assumed a post at the Schola Cantorum de Paris in the early 1930s. In 1932, he composed the '' Apparition de l'église éternelle'' for organ.

He also married the violinist and composer Claire Delbos (daughter of Victor Delbos Étienne Marie Justin Victor Delbos (26 September 1862, Figeac – 16 June 1916, Paris) was a Catholic philosopher and historian of philosophy.

Delbos was appointed a lecturer at the Sorbonne in 1902. In 1911 he became a member of the Académie des ...

) that year. Their marriage inspired him both to compose works for her to play (''Thème et variations'' for violin and piano in the year they were married) and to write pieces to celebrate their domestic happiness, including the song cycle ''Poèmes pour Mi

''Poèmes pour Mi'' (Poems for Mi) is a song cycle for dramatic soprano and piano or orchestra by Olivier Messiaen, composed in 1936 and 1937 and dedicated to his first wife, Claire Delbos. The text are poems by the composer based on the New Testa ...

'' in 1936, which he orchestrated in 1937. ''Mi'' was Messiaen's affectionate nickname for his wife. On 14 July 1937, the Messiaens' son, Pascal Emmanuel was born; Messiaen celebrated the occasion by writing Chants de Terre et de Ciel. The marriage turned to tragedy when Delbos lost her memory after an operation towards the end of World War II. She spent the rest of her life in mental institutions.

In 1934, Messiaen released his first major work for organ, La Nativité du Seigneur

''La Nativité du Seigneur'' (''The Nativity of the Lord'' or ''The Birth of the Saviour'') is a work for organ, written by the French composer Olivier Messiaen in 1935.

''La Nativité du Seigneur'' is a testament to Messiaen's Christian faith, ...

. He wrote a followup four years later titled Les Corps glorieux, however it was premièred in 1945.

In 1936, along with André Jolivet

André Jolivet (; 8 August 1905 – 20 December 1974) was a French composer. Known for his devotion to French culture and musical thought, Jolivet drew on his interest in acoustics and atonality, as well as both ancient and modern musical influe ...

, Daniel-Lesur and Yves Baudrier, Messiaen formed the group '' La jeune France'' ("Young France"). Their manifesto implicitly attacked the frivolity predominant in contemporary Parisian music and rejected Jean Cocteau

Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau (, , ; 5 July 1889 – 11 October 1963) was a French poet, playwright, novelist, designer, filmmaker, visual artist and critic. He was one of the foremost creatives of the su ...

's 1918 ''Le coq et l'arlequin'' in favour of a "living music, having the impetus of sincerity, generosity and artistic conscientiousness". Messiaen's career soon departed from this polemical phase.

In response to a commission for a piece to accompany light-and-water shows on

In response to a commission for a piece to accompany light-and-water shows on the Seine

)

, mouth_location = Le Havre/Honfleur

, mouth_coordinates =

, mouth_elevation =

, progression =

, river_system = Seine basin

, basin_size =

, tributaries_left = Yonne, Loing, Eure, Risle

, tributaries ...

during the '' Paris Exposition'', in 1937 Messiaen demonstrated his interest in using the ondes Martenot

The ondes Martenot ( ; , "Martenot waves") or ondes musicales ("musical waves") is an early electronic musical instrument. It is played with a keyboard or by moving a ring along a wire, creating "wavering" sounds similar to a theremin. A player ...

, an electronic instrument, by composing '' Fêtes des belles eaux'' for an ensemble of six. He included a part for the instrument in several of his subsequent compositions. During this period he composed several multi-movement organ works. He arranged his orchestral suite '' L'ascension'' for organ, replacing the orchestral version's third movement with an entirely new movement, ''Transports de joie d'une âme devant la gloire du Christ qui est la sienne'' ("Ecstasies of a soul before the glory of Christ which is the soul's own") (). He also wrote the extensive cycles ''La Nativité du Seigneur

''La Nativité du Seigneur'' (''The Nativity of the Lord'' or ''The Birth of the Saviour'') is a work for organ, written by the French composer Olivier Messiaen in 1935.

''La Nativité du Seigneur'' is a testament to Messiaen's Christian faith, ...

'' ("The Nativity of the Lord") and ''Les corps glorieux'' ("The glorious bodies").

At the outbreak of World War II, Messiaen was drafted into the French army. Due to poor eyesight, he was enlisted as a medical auxiliary rather than an active combatant.Griffiths (1985), p. 139 He was captured at Verdun

Verdun (, , , ; official name before 1970 ''Verdun-sur-Meuse'') is a large city in the Meuse department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

Verdun is the biggest city in Meuse, although the capital ...

, where he befriended clarinettist Henri Akoka; they were taken to Görlitz

Görlitz (; pl, Zgorzelec, hsb, Zhorjelc, cz, Zhořelec, :de:Ostlausitzer Mundart, East Lusatian dialect: ''Gerlz'', ''Gerltz'', ''Gerltsch'') is a town in the Germany, German state of Saxony. It is located on the Lusatian Neisse River, and ...

in May 1940, and imprisoned at Stalag VIII-A

Stalag VIII-A was a German World War II prisoner-of-war camp, located just to the south of the town of Görlitz in Lower Silesia, east of the River Neisse. The location of the camp lies in today's Polish town of Zgorzelec, which lies over the riv ...

. He met a cellist (Étienne Pasquier

Étienne Pasquier (7 June 15291 September 1615) was a French lawyer and man of letters. By his own account he was born in Paris on 7 June 1529, but according to others he was born in 1528. He was called to the Paris bar in 1549.

In 1558 he bec ...

) and a violinist () among his fellow prisoners. He wrote a trio for them, which he gradually incorporated into a more expansive new work, ''Quatuor pour la fin du temps

''Quatuor pour la fin du temps'' (), originally ''Quatuor de la fin du temps'' ("''Quartet of the End of Time''"), also known by its English title ''Quartet for the End of Time'', is an eight-movement piece of chamber music by the French composer ...

'' ("Quartet for the End of Time"). With the help of a friendly German guard, , he acquired manuscript paper and pencils. The work was first performed in January 1941 to an audience of prisoners and prison guards, with the composer playing a poorly maintained upright piano in freezing conditions and the trio playing third-hand unkempt instruments. The enforced introspection and reflection of camp life bore fruit in one of 20th-century classical music's acknowledged masterpieces. The title's "end of time" alludes to the Apocalypse

Apocalypse () is a literary genre in which a supernatural being reveals cosmic mysteries or the future to a human intermediary. The means of mediation include dreams, visions and heavenly journeys, and they typically feature symbolic imager ...

, and also to the way that Messiaen, through rhythm and harmony, used time in a manner completely different from his predecessors and contemporaries.

The idea of a European Centre of Education and Culture "Meeting Point Music Messiaen" on the site of Stalag VIII-A, for children and youth, artists, musicians and everyone in the region emerged in December 2004, was developed with the involvement of Messiaen's widow as a joint project between the council districts in Germany and Poland, and was finally completed in 2014.

''Tristan'' and serialism

Shortly after his release from Görlitz in May 1941 in large part due to the persuasions of his friend and teacherMarcel Dupré

Marcel Jean-Jules Dupré () (3 May 1886 – 30 May 1971) was a French organist, composer, and pedagogue.

Biography

Born in Rouen into a wealthy musical family, Marcel Dupré was a child prodigy. His father Aimable Albert Dupré was titular o ...

, Messiaen, who was now a household name, was appointed a professor of harmony at the Paris Conservatoire, where he taught until his retirement in 1978 due to French law. He compiled his ''Technique de mon langage musical'' ("Technique of my musical language") published in 1944, in which he quotes many examples from his music, particularly the Quartet. Although only in his mid-thirties, his students described him as an outstanding teacher. Among his early students were the composers Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music.

Born in Mont ...

and Karel Goeyvaerts

Karel August Goeyvaerts (8 June 1923 – 3 February 1993) was a Belgian composer.

Life

Goeyvaerts was born in Antwerp, where he studied at the Royal Conservatoire of Antwerp, Royal Flemish Music Conservatory; he later studied musical composition, ...

. Other pupils included Karlheinz Stockhausen in 1952, Alexander Goehr in 1956–57, Tristan Murail

Tristan Murail (born 11 March 1947) is a French composer associated with the "spectral" technique of composition. Among his compositions is the large orchestral work ''Gondwana''.

Early life and studies

Murail was born in Le Havre, France. His fa ...

in 1967–72 and George Benjamin during the late 1970s. The Greek composer Iannis Xenakis was referred to him in 1951; Messiaen urged Xenakis to take advantage of his background in mathematics and architecture in his music.

In 1943, Messiaen wrote '' Visions de l'Amen'' ("Visions of the Amen") for two pianos for Yvonne Loriod

Yvonne Louise Georgette Loriod-Messiaen (; 20 January 1924 – 17 May 2010) was a French pianist, teacher, and composer, and the second wife of composer Olivier Messiaen. Her sister was the Ondes Martenot player Jeanne Loriod.

Biography

Loriod ...

and himself to perform. Shortly thereafter he composed the enormous solo piano cycle '' Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus'' ("Twenty gazes upon the child Jesus") for her. Again for Loriod, he wrote ''Trois petites liturgies de la présence divine

''Trois'' is a 2000 erotic thriller film directed by Rob Hardy and produced by William Packer. It stars Gary Dourdan, Kenya Moore and Gretchen Palmer. The film was given a limited theatrical release and was one of the years highest grossing ...

'' ("Three small liturgies of the Divine Presence") for female chorus and orchestra, which includes a difficult solo piano part.

Two years after ''Visions de l'Amen'', Messiaen composed the song cycle '' Harawi'', the first of three works inspired by the legend of Tristan

Tristan (Latin/ Brythonic: ''Drustanus''; cy, Trystan), also known as Tristram or Tristain and similar names, is the hero of the legend of Tristan and Iseult. In the legend, he is tasked with escorting the Irish princess Iseult to wed ...

and Isolde. The second of these works about human (as opposed to divine) love was the result of a commission from Serge Koussevitzky. Messiaen stated that the commission did not specify the length of the work or the size of the orchestra. This was the ten-movement ''Turangalîla-Symphonie

The ''Turangalîla-Symphonie'' is the only symphony by Olivier Messiaen (1908–1992). It was written for an orchestra of large forces from 1946 to 1948 on a commission by Serge Koussevitzky in his wife's memory for the Boston Symphony Orches ...

''. It is not a conventional symphony

A symphony is an extended musical composition in Western classical music, most often for orchestra. Although the term has had many meanings from its origins in the ancient Greek era, by the late 18th century the word had taken on the meaning com ...

, but rather an extended meditation on the joy of human union and love. It does not contain the sexual guilt inherent in Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

's ''Tristan und Isolde

''Tristan und Isolde'' (''Tristan and Isolde''), WWV 90, is an opera in three acts by Richard Wagner to a German libretto by the composer, based largely on the 12th-century romance Tristan and Iseult by Gottfried von Strassburg. It was compose ...

'' because Messiaen believed that sexual love is a divine gift. The third piece inspired by the ''Tristan'' myth was ''Cinq rechants'' for twelve unaccompanied singers, described by Messiaen as influenced by the alba

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scottish people, Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed i ...

of the troubadour

A troubadour (, ; oc, trobador ) was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word ''troubadour'' is etymologically masculine, a female troubadour is usually called a ''trobairit ...

s. Messiaen visited the United States in 1949, where his music was conducted by Koussevitsky and Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra and his appear ...

. His ''Turangalîla-Symphonie'' was first performed in the US the same year, conducted by Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein ( ; August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990) was an American conductor, composer, pianist, music educator, author, and humanitarian. Considered to be one of the most important conductors of his time, he was the first America ...

.

Messiaen taught an analysis

Analysis ( : analyses) is the process of breaking a complex topic or substance into smaller parts in order to gain a better understanding of it. The technique has been applied in the study of mathematics and logic since before Aristotle (38 ...

class at the Paris Conservatoire. In 1947 he taught (and performed with Loriod) for two weeks in Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

. In 1949 he taught at Tanglewood

Tanglewood is a music venue in the towns of Lenox and Stockbridge in the Berkshire Hills of western Massachusetts. It has been the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra since 1937. Tanglewood is also home to three music schools: the ...

and presented his work at the Darmstadt new music summer school

Darmstadt () is a city in the States of Germany, state of Hesse in Germany, located in the southern part of the Frankfurt Rhine Main Area, Rhine-Main-Area (Frankfurt Metropolitan Region). Darmstadt has around 160,000 inhabitants, making it th ...

. While he did not employ the twelve-tone technique

The twelve-tone technique—also known as dodecaphony, twelve-tone serialism, and (in British usage) twelve-note composition—is a method of musical composition first devised by Austrian composer Josef Matthias Hauer, who published his "law o ...

, after three years teaching analysis of twelve-tone scores, including works by Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

, he experimented with ways of making scales of other elements (including duration, articulation and dynamics) analogous to the chromatic pitch scale. The results of these innovations was the "Mode de valeurs et d'intensités" for piano (from the ''Quatre études de rythme

Quatre is one of the Grenadines islands which lie between the Caribbean islands of Saint Vincent and Grenada. It is part of the nation of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.

Geography

Quatre island lies southwest of Pigeon Island and south o ...

'') which has been misleadingly described as the first work of "total serialism

In music, serialism is a method of composition using series of pitches, rhythms, dynamics, timbres or other musical elements. Serialism began primarily with Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique, though some of his contemporaries were als ...

". It had a large influence on the earliest European serial composers, including Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen. During this period he also experimented with musique concrète

Musique concrète (; ): " problem for any translator of an academic work in French is that the language is relatively abstract and theoretical compared to English; one might even say that the mode of thinking itself tends to be more schematic, ...

, music for recorded sounds.

Birdsong and the 1960s

When in 1952 Messiaen was asked to provide a test piece for flautists at the Paris Conservatoire, he composed the piece for flute and piano. While he had long been fascinated by birdsong, and birds had made appearances in several of his earlier works (for example , and ), the flute piece was based entirely on the song of the blackbird. He took this development to a new level with his 1953 orchestral work —its material consists almost entirely of the birdsong one might hear between midnight and noon in the Jura. From this period onwards, Messiaen incorporated birdsong into his compositions and composed several works for which birds provide both the title and subject matter (for example the collection of thirteen pieces for piano completed in 1958, and of 1971). Paul Griffiths observed that Messiaen was a more conscientious ornithologist than any previous composer, and a more musical observer of birdsong than any previous ornithologist. Messiaen's first wife died in 1959 after a long illness, and in 1961 he married Loriod. He began to travel widely, to attend musical events and to seek out and transcribe the songs of more exotic birds in the wild. Despite this, he only spoke French. Loriod frequently assisted her husband's detailed studies of birdsong while walking with him, by making tape recordings for later reference. In 1962 he visited Japan, where Gagaku music and

Messiaen's first wife died in 1959 after a long illness, and in 1961 he married Loriod. He began to travel widely, to attend musical events and to seek out and transcribe the songs of more exotic birds in the wild. Despite this, he only spoke French. Loriod frequently assisted her husband's detailed studies of birdsong while walking with him, by making tape recordings for later reference. In 1962 he visited Japan, where Gagaku music and Noh

is a major form of classical Japanese dance-drama that has been performed since the 14th century. Developed by Kan'ami and his son Zeami, it is the oldest major theatre art that is still regularly performed today. Although the terms Noh and ' ...

theatre inspired the orchestral "Japanese sketches", , which contain stylised imitations of traditional Japanese instruments.

Messiaen's music was by this time championed by, among others, Pierre Boulez, who programmed first performances at his Domaine musical

The Domaine musical was a concert society established by Pierre Boulez in Paris, which was active from 1954 to 1973. Composers represented at its concerts included Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Olivier Messiaen, Luciano Berio, John Cage, Sylva ...

concerts and the Donaueschingen festival. Works performed included , (commissioned for the 1960 festival) and . The latter piece was the result of a commission for a composition for three trombones and three xylophone

The xylophone (; ) is a musical instrument in the percussion family that consists of wooden bars struck by mallets. Like the glockenspiel (which uses metal bars), the xylophone essentially consists of a set of tuned wooden keys arranged in ...

s; Messiaen added to this more brass, wind, percussion and piano, and specified a xylophone, xylorimba

The xylorimba (sometimes referred to as xylo-marimba or marimba-xylophone) is a pitched percussion instrument similar to an extended-range xylophone with a range identical to some 5-octave celestas or 5-octave marimbas, though typically an octave ...

and marimba

The marimba () is a musical instrument in the percussion family that consists of wooden bars that are struck by mallets. Below each bar is a resonator pipe that amplifies particular harmonics of its sound. Compared to the xylophone, the timbre ...

rather than three xylophones. Another work of this period, , was commissioned as a commemoration of the dead of the two World Wars and was performed first semi-privately in the Sainte-Chapelle

The Sainte-Chapelle (; en, Holy Chapel) is a royal chapel in the Gothic style, within the medieval Palais de la Cité, the residence of the Kings of France until the 14th century, on the Île de la Cité in the River Seine in Paris, France.

Co ...

, then publicly in Chartres Cathedral

Chartres Cathedral, also known as the Cathedral of Our Lady of Chartres (french: Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Chartres), is a Roman Catholic church in Chartres, France, about southwest of Paris, and is the seat of the Bishop of Chartres. Mostly con ...

with Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

in the audience.

His reputation as a composer continued to grow and in 1959, he was nominated as an of the . In 1966, he was officially appointed professor of composition at the Paris Conservatoire, although he had in effect been teaching composition for years. Further honours included election to the Institut de France

The (; ) is a French learned society, grouping five , including the Académie Française. It was established in 1795 at the direction of the National Convention. Located on the Quai de Conti in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, the institute m ...

in 1967 and the Académie des beaux-arts

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, ...

in 1968, the Erasmus Prize

The Erasmus Prize is an annual prize awarded by the board of the Praemium Erasmianum Foundation to individuals or institutions that have made exceptional contributions to culture, society, or social science in Europe and the rest of the world. I ...

in 1971, the award of the Royal Philharmonic Society

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a memb ...

Gold Medal and the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize

The Ernst von Siemens Music Prize (short: Siemens Music Prize, german: link=no, Ernst von Siemens Musikpreis) is an annual music prize given by the Bayerische Akademie der Schönen Künste (Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts) on behalf of the Ernst v ...

in 1975, the Sonning Award (Denmark's highest musical honour) in 1977, the Wolf Prize in Arts

The Wolf Prize in Arts is awarded annually by the not-for-profit Wolf Foundation in Israel. It is one of the six Wolf Prizes established by the Foundation, and has been awarded since 1981; the others are in Agriculture, Chemistry, Mathematics, Medi ...

in 1982, and the presentation of the of the Belgian Order of the Crown in 1980.

''Transfiguration'', ''Canyons'', ''St. Francis'', and ''the Beyond''

Messiaen's next work was the large-scale ''La Transfiguration de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ

''La Transfiguration de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ'' ("The Transfiguration of Our Lord Jesus Christ") is a work written between 1965 and 1969 by Olivier Messiaen. It is based on the account found in the synoptic gospels of Transfiguration of Jesu ...

''. The composition occupied him from 1965 to 1969 and the musicians employed include a 100-voice ten-part choir, seven solo instruments and large orchestra. Its fourteen movements are a meditation on the story of Christ's Transfiguration. Shortly after its completion, Messiaen received a commission from Alice Tully

Alice Bigelow Tully (September 14, 1902 – December 10, 1993) was an American singer of opera and recital, music promoter, patron of the arts and philanthropist from New York. She was a second cousin of the American actress Katharine Hepburn.

...

for a work to celebrate the U.S. bicentennial

The United States Bicentennial was a series of celebrations and observances during the mid-1970s that paid tribute to historical events leading up to the creation of the United States of America as an independent republic. It was a central event ...

. He arranged a visit to the US in spring 1972, and was inspired by Bryce Canyon

Bryce Canyon National Park () is an American national park located in southwestern Utah. The major feature of the park is Bryce Canyon, which despite its name, is not a canyon, but a collection of giant natural amphitheaters along the eastern ...

in Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

, where he observed the canyon's distinctive colours and birdsong. The twelve-movement orchestral piece '' Des canyons aux étoiles...'' was the result, first performed in 1974 in New York.

In 1971, he was asked to compose a piece for the

In 1971, he was asked to compose a piece for the Paris Opéra

The Paris Opera (, ) is the primary opera and ballet company of France. It was founded in 1669 by Louis XIV as the , and shortly thereafter was placed under the leadership of Jean-Baptiste Lully and officially renamed the , but continued to be k ...

. While reluctant to undertake such a major project, he was persuaded by French president Georges Pompidou

Georges Jean Raymond Pompidou ( , ; 5 July 19112 April 1974) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1969 until his death in 1974. He previously was Prime Minister of France of President Charles de Gaulle from 1962 to 196 ...

to accept the commission and began work on his ''Saint-François d'Assise Saint-François is the French form of Saint Francis, and is the name of many locations:

Canada

* Saint-François River, a river in Quebec

* Saint-François Parish, New Brunswick, a parish in Madawaska County, New Brunswick

* Saint-François, Queb ...

'' in 1975 after two years of preparation. The composition was intensive (he also wrote his own libretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the t ...

) and occupied him from 1975 to 1979; the orchestration was carried out from 1979 until 1983. Messiaen preferred to describe the final work as a "spectacle" rather than an opera. It was first performed in 1983. Some commentators at the time thought that the opera would be his valediction (at times Messiaen himself believed so), but he continued to compose. In 1984, he published a major collection of organ pieces, ''Livre du Saint Sacrement''; other works include birdsong pieces for solo piano, and works for piano with orchestra.

In the summer of 1978, Messiaen was forced to retire from teaching at the Paris Conservatoire due to French law. He was promoted to the highest rank of the ''Légion d'honneur'', the ''Grand-Croix'', in 1987, and was awarded the decoration in London by his old friend, Jean Langlais

Jean François-Hyacinthe Langlais III (15 February 1907 – 8 May 1991) was a French composer of modern classical music, organist, and improviser. He described himself as "" ("Breton, of Catholic faith").

Biography

Langlais was born in L ...

. An operation prevented his participation in the celebration of his 70th birthday in 1978, but in 1988 tributes for Messiaen's 80th included a complete performance in London's Royal Festival Hall

The Royal Festival Hall is a 2,700-seat concert, dance and talks venue within Southbank Centre in London. It is situated on the South Bank of the River Thames, not far from Hungerford Bridge, in the London Borough of Lambeth. It is a Grade I l ...

of ''St. François'', which the composer attended, and Erato

In Greek mythology, Erato (; grc, Ἐρατώ) is one of the Greek Muses, which were inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. The name would mean "desired" or "lovely", if derived from the same root as Eros, as Apollonius o ...

's publication of a seventeen-CD collection of Messiaen's music including a disc of the composer in conversation with Claude Samuel

Claude Samuel (23 June 1931 – 14 June 2020) was a French music critic and radio personality.

Biography

Born in Paris, after medical studies and graduating as a dental surgeon, Samuel chose to devote himself to classical music journalism. He ...

.

Although in considerable pain near the end of his life (requiring repeated surgery on his back) he was able to fulfil a commission from the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, '' Éclairs sur l'au-delà...'', which was premièred six months after his death. He died in the Beaujon Hospital

The Beaujon Hospital () is located in Clichy, Paris, France and is operated by APHDP. It was named after Nicolas Beaujon, an eighteenth-century French banker

A bank is a financial institution that accepts deposits from the public and cr ...

in Clichy on 27 April 1992, aged 83.

On going through his papers, Loriod discovered that, in the last months of his life, he had been composing a concerto

A concerto (; plural ''concertos'', or ''concerti'' from the Italian plural) is, from the late Baroque era, mostly understood as an instrumental composition, written for one or more soloists accompanied by an orchestra or other ensemble. The typi ...

for four musicians he felt particularly grateful to, namely herself, the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich

Mstislav Leopoldovich Rostropovich, (27 March 192727 April 2007) was a Russian cellist and conductor. He is considered by many to be the greatest cellist of the 20th century. In addition to his interpretations and technique, he was wel ...

, the oboist

An oboist (formerly hautboist) is a musician who plays the oboe or any oboe family instrument, including the oboe d'amore, cor anglais or English horn, bass oboe and piccolo oboe or oboe musette.

The following is a list of notable past and pres ...

Heinz Holliger

Heinz Robert Holliger (born 21 May 1939) is a Swiss virtuoso oboist, composer and conductor. Celebrated for his versatility and technique, Holliger is among the most prominent oboists of his generation. His repertoire includes Baroque and Classic ...

and the flautist Catherine Cantin (hence the title ''Concert à quatre''). Four of the five intended movements were substantially complete; Yvonne Loriod undertook the orchestration of the second half of the first movement and of the whole of the fourth with advice from George Benjamin. It was premiered by the dedicatees in September 1994.

Music

Messiaen's music has been described as outside the western musical tradition, although growing out of that tradition and being influenced by it. Much of his output denies the western conventions of forward motion,development

Development or developing may refer to:

Arts

*Development hell, when a project is stuck in development

*Filmmaking, development phase, including finance and budgeting

*Development (music), the process thematic material is reshaped

* Photograph ...

and diatonic

Diatonic and chromatic are terms in music theory that are most often used to characterize Scale (music), scales, and are also applied to musical instruments, Interval (music), intervals, Chord (music), chords, Musical note, notes, musical sty ...

harmonic resolution. This is partly due to the symmetries of his technique—for instance the modes of limited transposition do not admit the conventional cadences

In Western musical theory, a cadence (Latin ''cadentia'', "a falling") is the end of a phrase in which the melody or harmony creates a sense of full or partial resolution, especially in music of the 16th century onwards.Don Michael Randel (19 ...

found in western classical music.Griffiths (1985), Introduction

His youthful love for the fairy-tale element in Shakespeare prefigured his later expressions of Catholic liturgy. Messiaen was not interested in depicting aspects of theology such as sin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

; rather he concentrated on the theology of joy, divine love

Love of God can mean either love for God or love by God. Love for God (''philotheia'') is associated with the concepts of worship, and devotions towards God.

The Greek term ''theophilia'' means the love or favour of God, and ''theophilos'' mean ...

and redemption.

Messiaen continually evolved new composition techniques, always integrating them into his existing musical style; his final works still retain the use of modes of limited transposition. For many commentators this continual development made every ''major'' work from the ''Quatuor'' onwards a conscious summation of all that Messiaen had composed up to that time. However, very few of these major works lack new technical ideas—simple examples being the introduction of communicable language in ''Meditations'', the invention of a new percussion instrument (the geophone

A geophone is a device that converts ground movement (velocity) into voltage, which may be recorded at a recording station. The deviation of this measured voltage from the base line is called the seismic response and is analyzed for structure of ...

) for ''Des canyons aux etoiles...'', and the freedom from any synchronisation with the main pulse of individual parts in certain birdsong episodes of ''St. François d'Assise''.

As well as discovering new techniques, Messiaen studied and absorbed foreign music, including Ancient Greek rhythms, Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

rhythms (he encountered Śārṅgadeva's list of 120 rhythmic units, the deçî-tâlas), Balinese and Javanese Gamelan, birdsong, and Japanese music (see ''Example 1'' for an instance of his use of ancient Greek and Hindu rhythms).

While he was instrumental in the academic exploration of his techniques (he compiled two treatise

A treatise is a formal and systematic written discourse on some subject, generally longer and treating it in greater depth than an essay, and more concerned with investigating or exposing the principles of the subject and its conclusions."Treat ...

s: the later one in five volumes was substantially complete when he died and was published posthumously), and was himself a master of music analysis, he considered the development and study of techniques a means to intellectual, aesthetic

Aesthetics, or esthetics, is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty and taste, as well as the philosophy of art (its own area of philosophy that comes out of aesthetics). It examines aesthetic values, often expressed th ...

, and emotional ends. Thus Messiaen maintained that a musical composition must be measured against three separate criteria: it must be interesting, beautiful to listen to, and it must touch the listener.Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 47

Messiaen wrote a large body of music for the piano. Although a considerable pianist himself, he was undoubtedly assisted by Yvonne Loriod's formidable piano technique and ability to convey complex rhythms and rhythmic combinations; in his piano writing from ''Visions de l'Amen'' onwards he had her in mind. Messiaen said, "I am able to allow myself the greatest eccentricities because to her anything is possible."Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 114

Western artistic influences

Developments in modern French music were a major influence on Messiaen, particularly the music of Claude Debussy and his use of thewhole-tone scale

In music, a whole-tone scale is a scale in which each note is separated from its neighbors by the interval of a whole tone. In twelve-tone equal temperament, there are only two complementary whole-tone scales, both six-note or ''hexatonic'' s ...

(which Messiaen called ''Mode 1'' in his modes of limited transposition). Messiaen rarely used the whole-tone scale in his compositions because, he said, after Debussy and Dukas there was "nothing to add",Messiaen, ''Technique de mon langage musical'' but the modes he did use are similarly symmetrical.

Messiaen had a great admiration for the music of Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the ...

, particularly the use of rhythm in earlier works such as ''The Rite of Spring

''The Rite of Spring''. Full name: ''The Rite of Spring: Pictures from Pagan Russia in Two Parts'' (french: Le Sacre du printemps: tableaux de la Russie païenne en deux parties) (french: Le Sacre du printemps, link=no) is a ballet and orchestral ...

'', and his use of orchestral colour. He was further influenced by the orchestral brilliance of Heitor Villa-Lobos

Heitor Villa-Lobos (March 5, 1887November 17, 1959) was a Brazilian composer, conductor, cellist, and classical guitarist described as "the single most significant creative figure in 20th-century Brazilian art music". Villa-Lobos has become the ...

, who lived in Paris in the 1920s and gave acclaimed concerts there. Among composers for the keyboard, Messiaen singled out Jean-Philippe Rameau

Jean-Philippe Rameau (; – ) was a French composer and music theory, music theorist. Regarded as one of the most important French composers and music theorists of the 18th century, he replaced Jean-Baptiste Lully as the dominant composer of Fr ...

, Domenico Scarlatti

Giuseppe Domenico Scarlatti, also known as Domingo or Doménico Scarlatti (26 October 1685-23 July 1757), was an Italian composer. He is classified primarily as a Baroque composer chronologically, although his music was influential in the deve ...

, Frédéric Chopin

Frédéric François Chopin (born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin; 1 March 181017 October 1849) was a Polish composer and virtuoso pianist of the Romantic period, who wrote primarily for solo piano. He has maintained worldwide renown as a leadin ...

, Debussy and Isaac Albéniz

Isaac Manuel Francisco Albéniz y Pascual (; 29 May 1860 – 18 May 1909) was a Spanish virtuoso pianist, composer, and conductor. He is one of the foremost composers of the Post-Romantic era who also had a significant influence on his conte ...

. He loved the music of Modest Mussorgsky

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky ( rus, link=no, Модест Петрович Мусоргский, Modest Petrovich Musorgsky , mɐˈdɛst pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ ˈmusərkskʲɪj, Ru-Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky version.ogg; – ) was a Russian compo ...

and incorporated varied modifications of what he called the "M-shaped" melodic motif from Mussorgsky's ''Boris Godunov

Borís Fyodorovich Godunóv (; russian: Борис Фёдорович Годунов; 1552 ) ruled the Tsardom of Russia as ''de facto'' regent from c. 1585 to 1598 and then as the first non-Rurikid tsar from 1598 to 1605. After the end of his ...

'', although he modified the final interval in this motif from a perfect fourth

A fourth is a musical interval encompassing four staff positions in the music notation of Western culture, and a perfect fourth () is the fourth spanning five semitones (half steps, or half tones). For example, the ascending interval from C to ...

to a tritone

In music theory, the tritone is defined as a musical interval composed of three adjacent whole tones (six semitones). For instance, the interval from F up to the B above it (in short, F–B) is a tritone as it can be decomposed into the three a ...

(''Example 3'').

Messiaen was further influenced by Surrealism

Surrealism is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express itself. Its aim was, according to l ...

, as may be seen from the titles of some of the piano ''Préludes'' ('' Un reflet dans le vent...'', "A reflection in the wind") and in some of the imagery of his poetry (he published poems as prefaces to certain works, for example ''Les offrandes oubliées'').

Colour

Colour lies at the heart of Messiaen's music. He believed that terms such as " tonal", " modal" and "serial" are misleading analytical conveniences. For him there were no modal, tonal or serial compositions, only music with or without colour. He said thatClaudio Monteverdi

Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (baptized 15 May 1567 – 29 November 1643) was an Italian composer, choirmaster and string player. A composer of both secular and sacred music, and a pioneer in the development of opera, he is considered ...

, Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his ra ...

, Chopin, Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

, Mussorgsky

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky ( rus, link=no, Модест Петрович Мусоргский, Modest Petrovich Musorgsky , mɐˈdɛst pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ ˈmusərkskʲɪj, Ru-Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky version.ogg; – ) was a Russian compo ...

and Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential 20th-century clas ...

all wrote strongly coloured music.

In some of Messiaen's scores, he notated the colours in the music (notably in ''Couleurs de la cité céleste'' and ''Des canyons aux étoiles...'')—the purpose being to aid the conductor in interpretation rather than to specify which colours the listener should experience. The importance of colour is linked to Messiaen's synaesthesia, which caused him to experience colours when he heard or imagined music (his form of synaesthesia, the most common form, involved experiencing the associated colours in a non-visual form rather than perceiving them visually). In his multi-volume music theory treatise ''Traité de rythme, de couleur, et d'ornithologie'' ("Treatise of Rhythm, Colour and Birdsong"), Messiaen wrote descriptions of the colours of certain chords. His descriptions range from the simple ("gold and brown") to the highly detailed ("blue-violet rocks, speckled with little grey cubes, cobalt blue

Cobalt blue is a blue pigment made by sintering cobalt(II) oxide with aluminum(III) oxide (alumina) at 1200 °C. Chemically, cobalt blue pigment is cobalt(II) oxide-aluminium oxide, or cobalt(II) aluminate, CoAl2O4. Cobalt blue is lighter ...

, deep Prussian blue

Prussian blue (also known as Berlin blue, Brandenburg blue or, in painting, Parisian or Paris blue) is a dark blue pigment produced by oxidation of ferrous ferrocyanide salts. It has the chemical formula Fe CN)">Cyanide.html" ;"title="e(Cyani ...

, highlighted by a bit of violet-purple, gold, red, ruby, and stars of mauve, black and white. Blue-violet is dominant").

When asked what Messiaen's main influence had been on composers, George Benjamin said, "I think the sheer ... colour has been so influential, ... rather than being a decorative element, essiaen showed that colourcould be a structural, a fundamental element, ... the fundamental material of the music itself."

Symmetry

Many of Messiaen's composition techniques made use of symmetries of time and pitch.Time

From his earliest works, Messiaen used non-retrogradable (palindromic) rhythms (''Example 2''). He sometimes combined rhythms with harmonic sequences in such a way that, if the process were repeated indefinitely, the music would eventually run through all possible permutations and return to its starting point. For Messiaen, this represented the "charm of impossibilities" of these processes. He only ever presented a portion of any such process, as if allowing the informed listener a glimpse of something eternal. In the first movement of ''Quatuor pour la fin du temps'' the piano and cello together provide an early example.Pitch

Messiaen used modes he called ''modes of limited transposition''. They are distinguished as groups of notes that can only betransposed

In linear algebra, the transpose of a matrix is an operator which flips a matrix over its diagonal;

that is, it switches the row and column indices of the matrix by producing another matrix, often denoted by (among other notations).

The tr ...

by a semitone a limited number of times. For example, the whole-tone scale (Messiaen's Mode 1) only exists in two transpositions: namely C–D–E–F–G–A and D–E–F–G–A–B. Messiaen abstracted these modes from the harmony of his improvisations and early works. Music written using the modes avoids conventional diatonic harmonic progressions, since for example Messiaen's Mode 2 (identical to the ''octatonic scale

An octatonic scale is any eight-note musical scale. However, the term most often refers to the symmetric scale composed of alternating whole and half steps, as shown at right. In classical theory (in contrast to jazz theory), this symmetrical ...

'' used also by other composers) permits precisely the dominant seventh

In music theory, a dominant seventh chord, or major minor seventh chord, is a seventh chord, usually built on the fifth degree of the major scale, and composed of a root, major third, perfect fifth, and minor seventh. Thus it is a major triad t ...

chords whose tonic the mode does not contain.

Time and rhythm

As well as making use of non-retrogradable rhythm and the Hindu decî-tâlas, Messiaen also composed with "additive" rhythms. This involves lengthening individual notes slightly or interpolating a short note into an otherwise regular rhythm (see ''Example 3''), or shortening or lengthening every note of a rhythm by the same duration (adding a semiquaver to every note in a rhythm on its repeat, for example). This led Messiaen to userhythmic cell The 1957 ''Encyclopédie Larousse''quoted in Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990). ''Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music'' (''Musicologie générale et sémiologue'', 1987). Translated by Carolyn Abbate (1990). . defines a cell in music as a "s ...

s that irregularly alternate between two and three units, a process that also occurs in Stravinsky's ''The Rite of Spring'', which Messiaen admired.