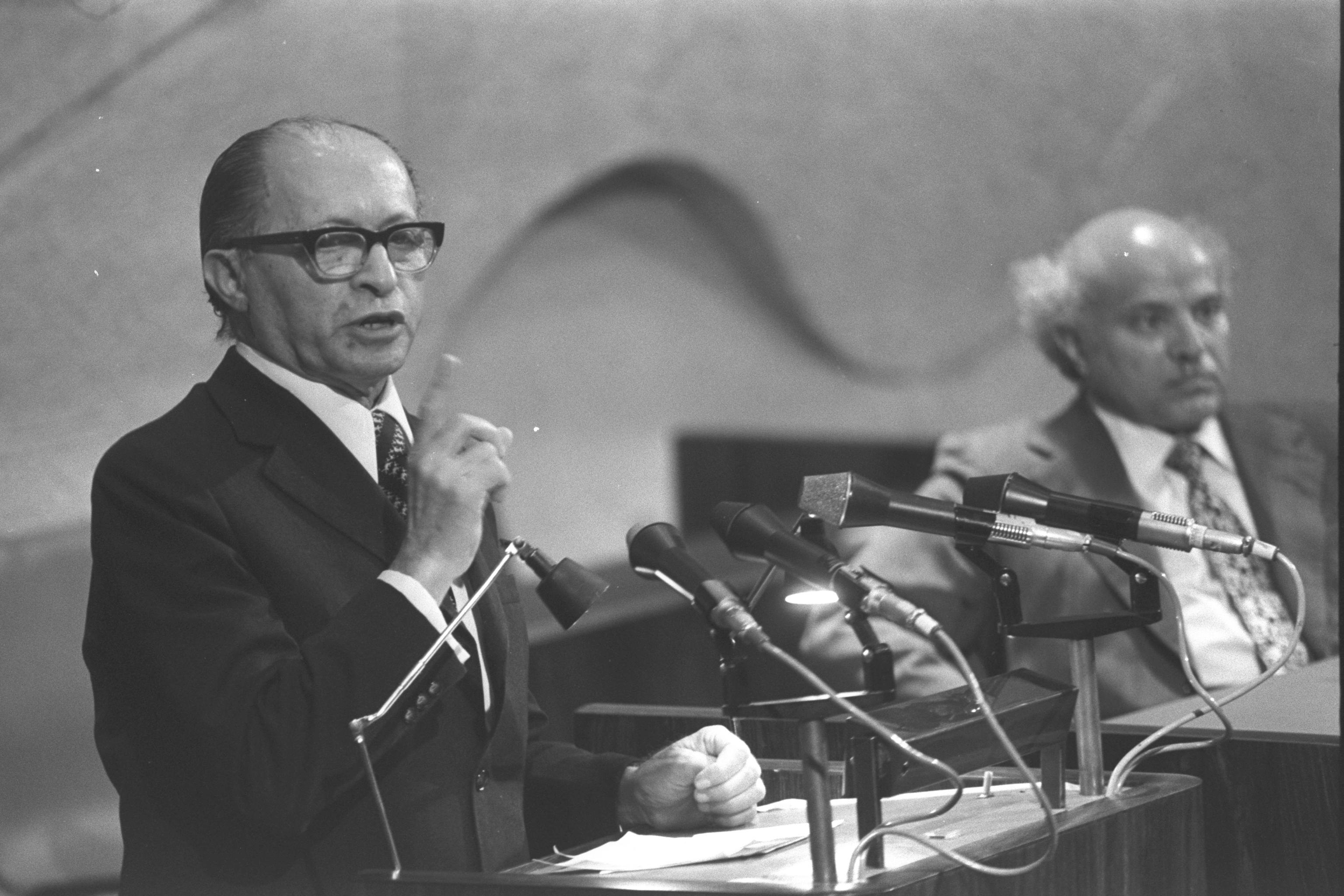

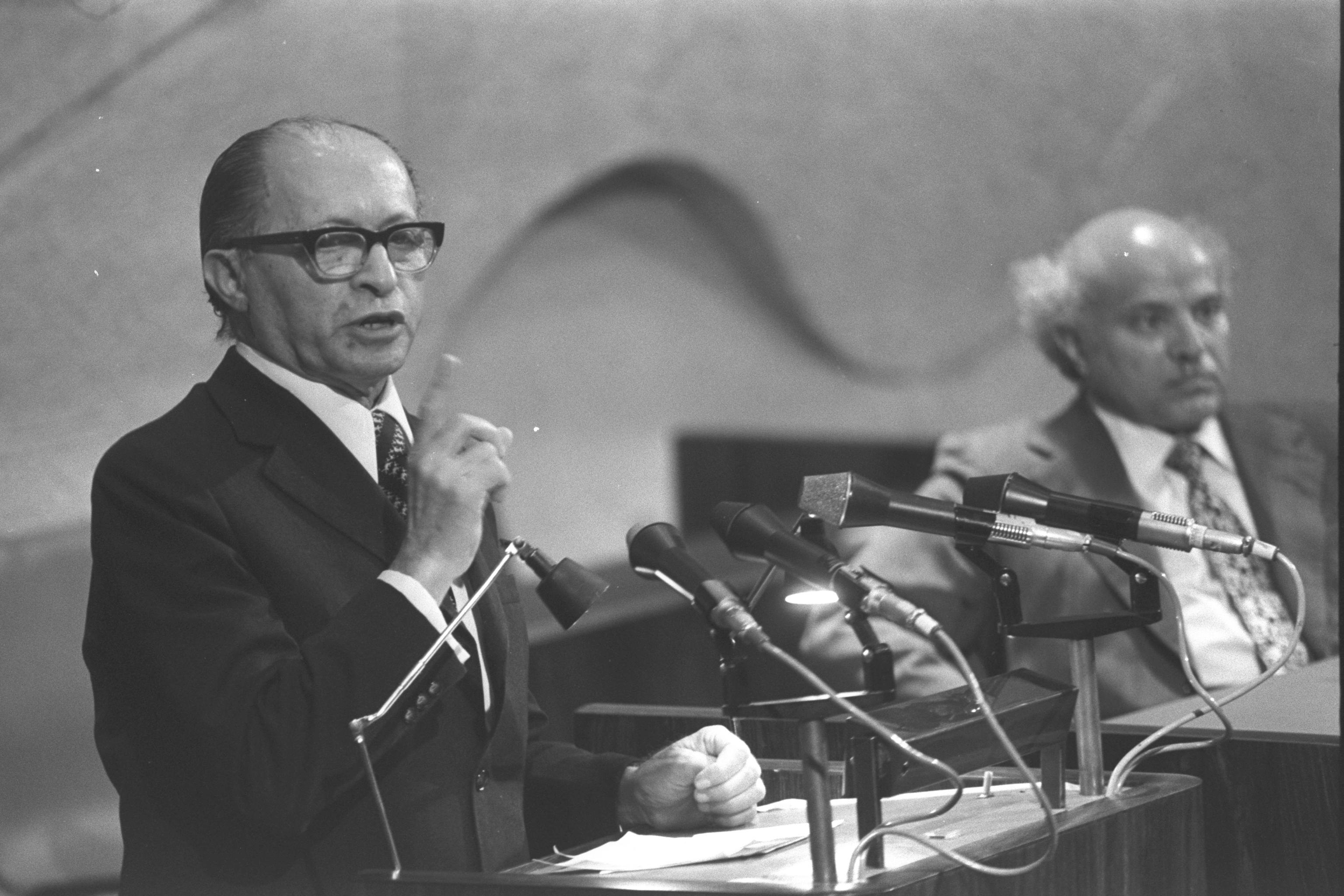

Menahem Begin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Menachem Begin ( ''Menaḥem Begin'' (); pl, Menachem Begin (Polish documents, 1931–1937); ''Menakhem Volfovich Begin''; 16 August 1913 – 9 March 1992) was an Israeli politician, founder of

During his studies, he organized a self-defense group of Jewish students to counter harassment by anti-Semites on campus. He graduated in 1935, but never practiced law. At this time he became a disciple of Vladimir "Ze'ev" Jabotinsky, the founder of the nationalist

During his studies, he organized a self-defense group of Jewish students to counter harassment by anti-Semites on campus. He graduated in 1935, but never practiced law. At this time he became a disciple of Vladimir "Ze'ev" Jabotinsky, the founder of the nationalist  In September 1939, after Germany invaded Poland, Begin, in common with a large part of Warsaw's Jewish leadership, escaped to Wilno (today

In September 1939, after Germany invaded Poland, Begin, in common with a large part of Warsaw's Jewish leadership, escaped to Wilno (today

"Biography – White Nights"

. Menachem Begin Heritage Center. Retrieved 16 January 2012. "Many of the new recruits deserted the army upon their arrival, but Begin decidedly refused to follow suit. 'I swore allegiance to the Polish army – I will not desert,' he resolutely told his friends when he was reunited with them on Jewish soil. Begin served in the Polish army for about a year and a half with the rank of corporal... At the initiative of Aryeh Ben-Eliezer and with the help of Mark Kahan, negotiations began with the Polish army regarding the release of five Jewish soldiers from the army, including Begin, in return for which the members of the IZL delegation would lobby in Washington for the Polish forces. The negotiations lasted many weeks until they finally met with success: The Polish commander announced the release of four of the soldiers. Fortunately, Begin was among them." Others give differing views, e.g.: * Amos Perlmutter (1987). ''The Life and Times of Menachem Begin'' Doubleday. . p. 134. "In the Ben Eliezer-Mark Kahan version, Begin received a complete, honorable release from the Anders Army. The truth is that he only received a one-year leave of absence, a kind of extended furlough, in order to enable him to join an Anders Army Jewish delegation which would go to the United States seeking help for the Polish government-in-exile. The delegation never materialized, mainly due to British opposition. Begin, however, never received an order to return to the ranks of the Army." During

After the

After the  Begin had meanwhile boarded the ''Altalena'', which was headed for Tel Aviv where the Irgun had more supporters. Many Irgun members, who joined the IDF earlier that month, left their bases and concentrated on the Tel Aviv beach. A confrontation between them and the IDF units started. In response, Ben-Gurion ordered

Begin had meanwhile boarded the ''Altalena'', which was headed for Tel Aviv where the Irgun had more supporters. Many Irgun members, who joined the IDF earlier that month, left their bases and concentrated on the Tel Aviv beach. A confrontation between them and the IDF units started. In response, Ben-Gurion ordered

In August 1948, Begin and members of the Irgun High Command emerged from the underground and formed the right-wing political party

In August 1948, Begin and members of the Irgun High Command emerged from the underground and formed the right-wing political party

In 1973, Begin agreed to a plan by

In 1973, Begin agreed to a plan by

On 17 May 1977 the Likud, headed by Begin, won the Knesset elections by a landslide, becoming the biggest party in the

On 17 May 1977 the Likud, headed by Begin, won the Knesset elections by a landslide, becoming the biggest party in the  The Likud campaign leading up to the election centered on Begin's personality. Demonized by the Alignment as

The Likud campaign leading up to the election centered on Begin's personality. Demonized by the Alignment as

In 1978 Begin, aided by Foreign Minister

In 1978 Begin, aided by Foreign Minister  Begin was less resolute in implementing the section of the Camp David Accord calling for Palestinian people, Palestinian self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. He appointed Agriculture Minister of Israel, Agriculture Minister

Begin was less resolute in implementing the section of the Camp David Accord calling for Palestinian people, Palestinian self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. He appointed Agriculture Minister of Israel, Agriculture Minister

On 3 March 1992, Begin suffered a severe heart attack in his apartment, and was rushed to Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Ichilov Hospital, where he was put in the intensive care unit. Begin arrived there unconscious and paralyzed on the left side of his body. His condition slightly improved following treatment, and he regained consciousness after 20 hours. For the next six days, Begin remained in serious condition. A pacemaker was implanted in his chest to stabilize his heartbeat on 5 March. Begin was too frail to overcome the effects of the heart attack, and his condition began to rapidly deteriorate on 9 March at about 3:15 AM. An emergency team of doctors and nurses attempted to resuscitate his failing heart. His children were notified of his condition and immediately rushed to his side. Begin died at 3:30 AM. His death was announced an hour and a half later. Shortly before 6:00 AM, the hospital rabbi arrived at his bedside to say the Kaddish prayer.

Begin's funeral took place in

On 3 March 1992, Begin suffered a severe heart attack in his apartment, and was rushed to Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Ichilov Hospital, where he was put in the intensive care unit. Begin arrived there unconscious and paralyzed on the left side of his body. His condition slightly improved following treatment, and he regained consciousness after 20 hours. For the next six days, Begin remained in serious condition. A pacemaker was implanted in his chest to stabilize his heartbeat on 5 March. Begin was too frail to overcome the effects of the heart attack, and his condition began to rapidly deteriorate on 9 March at about 3:15 AM. An emergency team of doctors and nurses attempted to resuscitate his failing heart. His children were notified of his condition and immediately rushed to his side. Begin died at 3:30 AM. His death was announced an hour and a half later. Shortly before 6:00 AM, the hospital rabbi arrived at his bedside to say the Kaddish prayer.

Begin's funeral took place in

The Menachem Begin Heritage Center

16 June 2004. * [https://web.archive.org/web/20120220034546/http://www.pmo.gov.il/PMOEng/History/FormerPrimeMinister/MenacheBegin.htm Menachem Begin – The Sixth Prime Minister] at the Official Site of the [Israeli] Prime Minister's Office. * . *

in English

The Camp David Accords

Irgun webpage

* including the Nobel Lecture, 10 December 1978

Bodies of murdered Clifford Martin and Marvyn Paice

*

About the future Begin Monument in Brest, Belarus

, ''Vecherniy Brest'', Brest, Belarus. *

Unveiling of the Begin Monument in Brest, Belarus (31 October 2013)

, ''Vecherniy Brest'', Brest, Belarus.

at the Israel State Archives (Prime Minister's Office). * [https://web.archive.org/web/20130716160432/http://jewishhistorylectures.org/2013/04/28/menachem-begin-a-new-israel/ "Menachem Begin: A New Israel", Video Lecture] by Henry Abramson.

Prime Minister Menachem Begin on justice and the rule of law: selected documents on the 20th anniversary of his death on Israel State Archives website

{{DEFAULTSORT:Begin, Menachem Menachem Begin, 1913 births 1992 deaths Belarusian Jews Belarusian Nobel laureates Betar Burials at the Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives Foreign Gulag detainees Herut politicians Irgun members Israeli anti-communists Israeli Nobel laureates Israeli people of Belarusian-Jewish descent Israeli torture victims Jewish Israeli politicians Ashkenazi Jews in Mandatory Palestine Leaders of political parties in Israel Likud politicians Members of the 10th Knesset (1981–1984) Members of the 1st Knesset (1949–1951) Members of the 2nd Knesset (1951–1955) Members of the 3rd Knesset (1955–1959) Members of the 4th Knesset (1959–1961) Members of the 5th Knesset (1961–1965) Members of the 6th Knesset (1965–1969) Members of the 7th Knesset (1969–1974) Members of the 8th Knesset (1974–1977) Members of the 9th Knesset (1977–1981) Ministers of Agriculture of Israel Ministers of Defense of Israel Ministers of Foreign Affairs of Israel Ministers of Justice of Israel Nobel Peace Prize laureates People from Brest, Belarus People from Brestsky Uyezd Polish emigrants to Mandatory Palestine Polish Nobel laureates Polish people detained by the NKVD Prime Ministers of Israel Prisoners and detainees of the Soviet Union Revisionist Zionism Rhetoricians University of Warsaw alumni Yishuv during World War II Likud leaders

Likud

Likud ( he, הַלִּיכּוּד, HaLikud, The Consolidation), officially known as Likud – National Liberal Movement, is a major centre-right to right-wing political party in Israel. It was founded in 1973 by Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon ...

and the sixth Prime Minister of Israel. Before the creation of the state of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, he was the leader of the Zionist militant group Irgun

Irgun • Etzel

, image = Irgun.svg , image_size = 200px

, caption = Irgun emblem. The map shows both Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan, which the Irgun claimed in its entirety for a future Jewish state. The acronym "Etzel" i ...

, the Revisionist breakaway from the larger Jewish paramilitary organization Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

. He proclaimed a revolt

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

, on 1 February 1944, against the British mandatory government, which was initially opposed by the Jewish Agency

The Jewish Agency for Israel ( he, הסוכנות היהודית לארץ ישראל, translit=HaSochnut HaYehudit L'Eretz Yisra'el) formerly known as The Jewish Agency for Palestine, is the largest Jewish non-profit organization in the world. ...

. Later, the Irgun fought the Arabs during the 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine.

Begin was elected to the first Knesset

The Knesset ( he, הַכְּנֶסֶת ; "gathering" or "assembly") is the unicameral legislature of Israel. As the supreme state body, the Knesset is sovereign and thus has complete control of the entirety of the Israeli government (with ...

, as head of Herut

Herut ( he, חֵרוּת, ''Freedom'') was the major conservative nationalist political party in Israel from 1948 until its formal merger into Likud in 1988. It was an adherent of Revisionist Zionism.

History

Herut was founded by Menachem Begin ...

, the party he founded, and was at first on the political fringe, embodying the opposition to the Mapai

Mapai ( he, מַפָּא"י, an acronym for , ''Mifleget Poalei Eretz Yisrael'', lit. "Workers' Party of the Land of Israel") was a democratic socialist political party in Israel, and was the dominant force in Israeli politics until its merger in ...

-led government and Israeli establishment. He remained in opposition in the eight consecutive elections (except for a national unity government around the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

), but became more acceptable to the political center. His 1977 electoral victory and premiership ended three decades of Labor Party political dominance.

Begin's most significant achievement as Prime Minister was the signing of a peace treaty with Egypt in 1979, for which he and Anwar Sadat

Muhammad Anwar el-Sadat, (25 December 1918 – 6 October 1981) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the third president of Egypt, from 15 October 1970 until his assassination by fundamentalist army officers on 6 ...

shared the Nobel Prize for Peace

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

. In the wake of the Camp David Accords

The Camp David Accords were a pair of political agreements signed by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin on 17 September 1978, following twelve days of secret negotiations at Camp David, the country retrea ...

, the Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

(IDF) withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula, or simply Sinai (now usually ) (, , cop, Ⲥⲓⲛⲁ), is a peninsula in Egypt, and the only part of the country located in Asia. It is between the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south, and is a l ...

, which had been captured from Egypt in the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

. Later, Begin's government promoted the construction of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Begin authorized the bombing of the Osirak nuclear plant in Iraq and the invasion of Lebanon in 1982 to fight PLO strongholds there, igniting the 1982 Lebanon War

The 1982 Lebanon War, dubbed Operation Peace for Galilee ( he, מבצע שלום הגליל, or מבצע של"ג ''Mivtsa Shlom HaGalil'' or ''Mivtsa Sheleg'') by the Israeli government, later known in Israel as the Lebanon War or the First L ...

. As Israeli military involvement in Lebanon deepened, and the Sabra and Shatila massacre

The Sabra and Shatila massacre (also known as the Sabra and Chatila massacre) was the killing of between 460 and 3,500 civilians, mostly Palestinians and Lebanese Shiites, by the militia of the Lebanese Forces, a Maronite Christian Lebanes ...

, carried out by Christian Phalangist

The Kataeb Party ( ar, حزب الكتائب اللبنانية '), also known in English as the Phalanges, is a Christian political party in Lebanon. The party played a major role in the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990). In decline in the la ...

militia allies of the Israelis, shocked world public opinion, Begin grew increasingly isolated. As IDF forces remained mired in Lebanon and the economy suffered from hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimize their holdings in that currency as t ...

, the public pressure on Begin mounted. Depressed by the death of his wife Aliza in November 1982, he gradually withdrew from public life, until his resignation in October 1983.

Biography

Menachem Begin was born to Zeev Dov and Hassia Begun in what was then Brest-Litovsk in theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

(today Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

, Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

). He was the youngest of three children. On his mother's side he was descended from distinguished rabbis. His father, a timber merchant, was a community leader, a passionate Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

, and an admirer of Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern p ...

. The midwife who attended his birth was the grandmother of Ariel Sharon

Ariel Sharon (; ; ; also known by his diminutive Arik, , born Ariel Scheinermann, ; 26 February 1928 – 11 January 2014) was an Israeli general and politician who served as the 11th Prime Minister of Israel from March 2001 until April 2006.

S ...

.

After a year of a traditional cheder

A ''cheder'' ( he, חדר, lit. "room"; Yiddish pronunciation ''kheyder'') is a traditional primary school teaching the basics of Judaism and the Hebrew language.

History

''Cheders'' were widely found in Europe before the end of the 18th ...

education Begin started studying at a "Tachkemoni" school, associated with the religious Zionist movement. In his childhood, Begin, like most Jewish children in his town, was a member of the Zionist scouts movement Hashomer Hatzair

Hashomer Hatzair ( he, הַשׁוֹמֵר הַצָעִיר, , ''The Young Guard'') is a Labor Zionist, secular Jewish youth movement founded in 1913 in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, Austria-Hungary, and it was also the name of the group ...

. He was a member of Hashomer Hatzair until the age of 13, and at 16, he joined Betar

The Betar Movement ( he, תנועת בית"ר), also spelled Beitar (), is a Revisionist Zionist youth movement founded in 1923 in Riga, Latvia, by Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky. Chapters sprang up across Europe, even during World War II. After t ...

. At 14, he was sent to a Polish government school, where he received a solid grounding in classical literature

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

.

Begin studied law at the University of Warsaw

The University of Warsaw ( pl, Uniwersytet Warszawski, la, Universitas Varsoviensis) is a public university in Warsaw, Poland. Established in 1816, it is the largest institution of higher learning in the country offering 37 different fields of ...

, where he learned the oratory and rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

skills that became his trademark as a politician, and viewed as demagogy

A demagogue (from Greek , a popular leader, a leader of a mob, from , people, populace, the commons + leading, leader) or rabble-rouser is a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, e ...

by his critics.

During his studies, he organized a self-defense group of Jewish students to counter harassment by anti-Semites on campus. He graduated in 1935, but never practiced law. At this time he became a disciple of Vladimir "Ze'ev" Jabotinsky, the founder of the nationalist

During his studies, he organized a self-defense group of Jewish students to counter harassment by anti-Semites on campus. He graduated in 1935, but never practiced law. At this time he became a disciple of Vladimir "Ze'ev" Jabotinsky, the founder of the nationalist Revisionist Zionism

Revisionist Zionism is an ideology developed by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, who advocated a "revision" of the "practical Zionism" of David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann which was focused on the settling of ''Eretz Yisrael'' (Land of Israel) by independent ...

movement and its youth wing, Betar. His rise within Betar was rapid: at 22, he shared the dais with his mentor at the Betar World Congress in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

. The pre-war Polish government actively supported Zionist youth and paramilitary movements. Begin's leadership qualities were quickly recognised. In 1937 he was the active head of Betar in Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

and became head of the largest branch, that of Poland. As head of Betar's Polish branch, Begin traveled among regional branches to encourage supporters and recruit new members. To save money, he stayed at the homes of Betar members. During one such visit, he met his future wife Aliza Arnold, who was the daughter of his host. The couple married on 29 May 1939. They had three children: Binyamin

Benjamin ( he, ''Bīnyāmīn''; "Son of (the) right") blue letter bible: https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h3225/kjv/wlc/0-1/ H3225 - yāmîn - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (kjv) was the last of the two sons of Jacob and Rachel (Jacob's thir ...

, Leah and Hassia.

Living in Warsaw in Poland, Begin encouraged Betar to set up an organization to bring Polish Jews to Palestine. He unsuccessfully attempted to smuggle 1,500 Jews into Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

at the end of August 1939. Returning to Warsaw afterward, he left three days after the German 1939 invasion began, first to the southwest and then to Wilno

Vilnius ( , ; see also #Etymology and other names, other names) is the capital and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the munic ...

.

In September 1939, after Germany invaded Poland, Begin, in common with a large part of Warsaw's Jewish leadership, escaped to Wilno (today

In September 1939, after Germany invaded Poland, Begin, in common with a large part of Warsaw's Jewish leadership, escaped to Wilno (today Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

), then eastern Poland, to avoid inevitable arrest. The town was soon occupied by the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, but from 28 October 1939, it was the capital of the Republic of Lithuania. Wilno was a predominately Polish and Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

town; an estimated 40 percent of the population was Jewish, with the YIVO

YIVO (Yiddish: , ) is an organization that preserves, studies, and teaches the cultural history of Jewish life throughout Eastern Europe, Germany, and Russia as well as orthography, lexicography, and other studies related to Yiddish. (The word '' ...

institute located there. As a prominent pre-war Zionist and reserve status officer-cadet, on 20 September 1940, Begin was arrested by the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

and detained in the Lukiškės Prison

Lukiškės Prison ( lt, Lukiškių tardymo izoliatorius kalėjimas; pl, Więzienie na Łukiszkach or simply ''Łukiszki''; be, Лукішкі) was a prison in the center of Vilnius, Lithuania, near the Lukiškės Square.

Construction Backg ...

. In later years he wrote about his experience of being tortured. He was accused of being an "agent of British imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

" and sentenced to eight years in the Soviet gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

camps. On 1 June 1941 he was sent to the Pechora

Pechora (russian: Печо́ра; kv, Печӧра, ''Pećöra'') is a town in the Komi Republic, Russia, located on the Pechora River, west of and near the northern Ural Mountains. The area of the town is . Population:

History

Pechora was ...

labor camp

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (especi ...

s in Komi Republic, the northern part of European Russia, where he stayed until May 1942. Much later in life, Begin recorded and reflected upon his experiences in the interrogations and life in the camp in his memoir ''White Nights

White night, White Night, or White Nights may refer to:

* White night (astronomy), a night in which it never gets completely dark, at high latitudes outside the Arctic and Antarctic Circles

* White Night festivals, all-night arts festivals held in ...

''.

In July 1941, just after Germany attacked the Soviet Union, and following his release under the Sikorski–Mayski agreement because he was a Polish national, Begin joined the Free Polish Anders' Army

Anders' Army was the informal yet common name of the Polish Armed Forces in the East in the 1941–42 period, in recognition of its commander Władysław Anders. The army was created in the Soviet Union but, in March 1942, based on an understand ...

as a corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use in some form by many militaries and by some police forces or other uniformed organizations. The word is derived from the medieval Italian phrase ("head of a body"). The rank is usually the lowest ranking non ...

officer cadet

Officer Cadet is a rank held by military cadets during their training to become commissioned officers. In the United Kingdom, the rank is also used by members of University Royal Naval Units, University Officer Training Corps and University Air ...

. He was later sent with the army to Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

via the Persian Corridor

The Persian Corridor was a supply route through Iran into Azerbaijan SSR, Soviet Azerbaijan by which British aid and American Lend-Lease supplies were transferred to the Soviet Union during World War II. Of the 17.5 million long tons of U.S. Len ...

, where he arrived in May 1942.

Upon arriving in Palestine, Begin, like many other Polish Jewish soldiers of the Anders' Army, faced a choice between remaining with the Anders' Army to fight Nazi Germany in Europe, or staying in Palestine to fight for establishment of a Jewish state. While he initially wished to remain with the Polish army, he was eventually persuaded to change his mind by his contacts in the Irgun, as well as Polish officers sympathetic to the Zionist cause. Consequently, General Michał Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski Michał () is a Polish and Sorbian form of Michael and may refer to:

* Michał Bajor (born 1957), Polish actor and musician

* Michał Chylinski (born 1986), Polish basketball player

* Michał Drzymała (1857–1937), Polish rebel

* Michał Helle ...

, the second-in-command of the Army, issued Begin with a "leave of absence without an expiration" which gave Begin official permission to stay in Palestine. In December 1942 he left Anders's Army and joined the Irgun.Sources differ on how Begin left Anders' Army. Many indicate that he was discharged, e.g.:

* Eitan Haber (1979). ''Menachem Begin: The Legend and the Man''. Dell Publishing Company. p. 136. . "A while later Anders's Chief of Staff, General Ukolitzky, did agree to the release of six Jewish soldiers to go to the United States on a campaign to get the Jewish community to help the remnants of European Jewry. The Chief of Staff, who was well acquainted with Dr. Kahan, invited him to his office for a drink. There were a number of senior officers present, and Kahan realized that this was a farewell party for Ukolitzky. 'I'm leaving here on a mission, and my colleagues are throwing a party but the last document I signed was an approval of release for Menahem Begin.'"

* Bernard Reich (1990) ''Political Leaders of the Contemporary Middle East and North Africa'' Greenwood Publishing Group. . p. 72. "In 1942 he arrived in Palestine as a soldier in General Anders's (Polish) army. Begin was discharged from the army in December 1943."

* Harry Hurwitz (2004). ''Begin: His Life, Words and Deeds''. Gefen Publishing House. . p. 9. "His friends urged him to desert the Anders Army, but he refused to do any such dishonourable thing and waited until, as a result of negotiations, he was discharged and permitted to enter Eretz Israel, then under British mandatory rule".

"Biography – White Nights"

. Menachem Begin Heritage Center. Retrieved 16 January 2012. "Many of the new recruits deserted the army upon their arrival, but Begin decidedly refused to follow suit. 'I swore allegiance to the Polish army – I will not desert,' he resolutely told his friends when he was reunited with them on Jewish soil. Begin served in the Polish army for about a year and a half with the rank of corporal... At the initiative of Aryeh Ben-Eliezer and with the help of Mark Kahan, negotiations began with the Polish army regarding the release of five Jewish soldiers from the army, including Begin, in return for which the members of the IZL delegation would lobby in Washington for the Polish forces. The negotiations lasted many weeks until they finally met with success: The Polish commander announced the release of four of the soldiers. Fortunately, Begin was among them." Others give differing views, e.g.: * Amos Perlmutter (1987). ''The Life and Times of Menachem Begin'' Doubleday. . p. 134. "In the Ben Eliezer-Mark Kahan version, Begin received a complete, honorable release from the Anders Army. The truth is that he only received a one-year leave of absence, a kind of extended furlough, in order to enable him to join an Anders Army Jewish delegation which would go to the United States seeking help for the Polish government-in-exile. The delegation never materialized, mainly due to British opposition. Begin, however, never received an order to return to the ranks of the Army." During

the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

, Begin's father was among the 5,000 Brest Jews rounded up by the Nazis at the end of June 1941. Instead of being sent to a forced labor camp, they were shot or drowned in the river. His mother and his elder brother Herzl also were murdered in the Holocaust.

Jewish underground

Begin quickly made a name for himself as a fierce critic of the dominant Zionist leadership for being too cooperative with the British, and argued that the only way to save the Jews of Europe, who were facing extermination, was to compel the British to leave so that a Jewish state could be established. In 1942 he joined theIrgun

Irgun • Etzel

, image = Irgun.svg , image_size = 200px

, caption = Irgun emblem. The map shows both Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan, which the Irgun claimed in its entirety for a future Jewish state. The acronym "Etzel" i ...

(''Etzel''), an underground Zionist paramilitary organization which had split from the main Jewish military organization, the Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

, in 1931. Begin assumed the Irgun's leadership in 1944, determined to force the British government to remove its troops entirely from Palestine. The official Jewish leadership institutions in Palestine, the Jewish Agency

The Jewish Agency for Israel ( he, הסוכנות היהודית לארץ ישראל, translit=HaSochnut HaYehudit L'Eretz Yisra'el) formerly known as The Jewish Agency for Palestine, is the largest Jewish non-profit organization in the world. ...

and Jewish National Council

The Jewish National Council (JNC; he, ועד לאומי, ''Va'ad Le'umi''), also known as the Jewish People's Council was the main national executive organ of the Assembly of Representatives of the Jewish community (Yishuv) within Mandatory Pale ...

("Vaad Leumi"), backed up by their military arm, the Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

, had refrained from directly challenging British authority. They were convinced that the British would establish a Jewish state after the war due to support for the Zionist cause among both the Conservative and Labour parties. Giving as reasons that the British had reneged on the promises given in the Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

and that the White Paper of 1939

The White Paper of 1939Occasionally also known as the MacDonald White Paper (e.g. Caplan, 2015, p.117) after Malcolm MacDonald, the British Colonial Secretary, who presided over its creation. was a policy paper issued by the British governmen ...

restricting Jewish immigration was an escalation of their pro-Arab policy, he decided to break with the official institutions and launch an armed rebellion against British rule, in cooperation with Lehi, another breakaway Zionist group.

Begin had studied the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

and the Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British rule in India. It lasted from 1857 to 1947.

The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged ...

, and, while planning the rebellion with Irgun commanders, devised a strategy of leverage he believed would force the British out. He proposed a series of guerrilla attacks that would humiliate the British and damage their prestige, which would force them to resort to repressive measures, which would in turn alienate the Yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the s ...

. Begin banked on the international media being attracted to the action, which he referred to as turning Palestine into a "glass house", with the world looking in. This would draw international attention, and British repression would create global sympathy for the Irgun's cause, which in turn would translate into political pressure on Britain. Ultimately, the British would be forced to choose between continued repression or withdrawal, and Begin was certain that in the end, the British would leave. Furthermore, so as not to disturb the war effort against Germany, only British government and police targets would be attacked at first, while military targets would only be attacked once Germany had been defeated.Bell, Bowyer J.: ''Terror out of Zion'' (1976)

On 1 February 1944, the Irgun proclaimed a revolt. Twelve days later, it put its plan into action when Irgun teams bombed the empty offices of the British Mandate's Immigration Department in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

, and Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

. The Irgun next bombed the Income Tax Offices in those three cities, followed by a series of attacks on police stations in which two Irgun fighters and six policemen were killed. Meanwhile, Lehi joined the revolt with a series of shooting attacks on policemen.

The Irgun and Lehi attacks intensified throughout 1944. These operations were financed by demanding money from Jewish merchants and engaging in insurance scams in the local diamond industry.

In 1944, after Lehi gunmen assassinated Lord Moyne

Walter Edward Guinness, 1st Baron Moyne, DSO & Bar, PC (29 March 1880 – 6 November 1944), was an Anglo-Irish politician and businessman. He served as the British minister of state in the Middle East until November 1944, when he was assass ...

, the British Resident Minister in the Middle East, the official Jewish authorities, fearing British retaliation, ordered the Haganah to undertake a campaign of collaboration with the British. Known as The Hunting Season

The Saison (Hunting Season) ( he, הסזון, links=no, short for ) was the name given to the Haganah's attempt, as ordered by the official bodies of the pre-state Yishuv, to suppress the Irgun's insurgency against the government of the British ...

, the campaign seriously crippled the Irgun for several months, while Lehi, having agreed to suspend their anti-British attacks, was spared. Begin, anxious to prevent a civil war, ordered his men not to retaliate or resist being taken captive, convinced that the Irgun could ride out the Season, and that the Jewish Agency would eventually side with the Irgun when it became apparent the British government had no intention of making concessions. Gradually, shamed at participating in what was viewed as a collaborationist campaign, the enthusiasm of the Haganah began to wane, and Begin's assumptions were proven correct. The Irgun's restraint also earned it much sympathy from the Yishuv, whereas previously it had been assumed by many that it had placed its own political interests before those of the Yishuv.

In the summer of 1945, as it became clear that the British were not planning on establishing a Jewish state and would not allow significant Jewish immigration to Palestine, Jewish public opinion shifted decisively against the British, and the Jewish authorities sent feelers to the Irgun and Lehi to discuss an alliance. The result was the Jewish Resistance Movement

The Jewish Resistance Movement ( he, תנועת המרי העברי, ''Tnu'at HaMeri HaIvri'', literally ''Hebrew Rebellion Movement''), also called the United Resistance Movement (URM), was an alliance of the Zionist paramilitary organizations H ...

, a framework under which the Haganah, Irgun, and Lehi launched coordinated series of anti-British operations. For several months in 1945–46, the Irgun fought as part of the Jewish Resistance Movement. Following Operation Agatha

Operation Agatha (Saturday, June 29, 1946), sometimes called Black Sabbath ( he, השבת השחורה) or Black Saturday because it began on the Jewish sabbath, was a police and military operation conducted by the British authorities in Mandato ...

, during which the British arrested many Jews, seized arms caches, and occupied the Jewish Agency building, from which many documents were removed, Begin ordered an attack on the British military and administrative headquarters at the King David Hotel

The King David Hotel ( he, מלון המלך דוד, Malon ha-Melekh David; ar, فندق الملك داود) is a 5-star hotel in Jerusalem and a member of The Leading Hotels of the World. Opened in 1931, the hotel was built with locally qua ...

following a request from the Haganah, although the Haganah's permission was later rescinded. The King David Hotel bombing

The British administrative headquarters for Mandatory Palestine, housed in the southern wing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, were bombed in a terrorist attack on 22 July 1946 by the militant right-wing Zionist underground organization the ...

resulted in the destruction of the building's southern wing, and 91 people, mostly British, Arabs, and Jews, were killed.

The fragile partnership collapsed following the bombing, partly because contrary to instructions, it was carried out during the busiest part of the day at the hotel. The Haganah, from then on, would rarely mount attacks against British forces and would focus mainly on the Aliyah Bet

''Aliyah Bet'' ( he, עלייה ב', "Aliyah 'B'" – bet being the second letter of the Hebrew alphabet) was the code name given to illegal immigration by Jews, most of whom were refugees escaping from Nazi Germany, and later Holocaust sur ...

illegal immigration campaign, and while it occasionally took half-hearted measures against the Irgun, it never returned to full-scale collaboration with the British. The Irgun and Lehi continued waging a full-scale insurgency against the British, and together with the Haganah's illegal immigration campaign, this forced a large commitment of British forces to Palestine that was gradually sapping British financial resources. Three particular Irgun operations directly ordered by Begin: the Night of the Beatings, the Acre Prison break

The Acre Prison break was an operation undertaken by the Irgun on May 4, 1947, in the British Mandate of Palestine, in which its men broke through the walls of the Central Prison in Acre and freed 27 incarcerated Irgun and Lehi members.

History

...

, and the Sergeants affair, were cited as particularly influencing the British to leave due to the great loss of British prestige and growing public opposition to Britain remaining in Palestine at home they generated. In September 1947, the British cabinet voted to leave Palestine, and in November of that year, the United Nations approved a resolution to partition the country between Arabs and Jews. The financial burden imposed on Britain by the Jewish insurgency, together with the tremendous public opposition to keeping troops in Palestine it generated among the British public was later cited by British officials as a major factor in Britain's decision to evacuate Palestine.Hoffman, Bruce: ''Anonymous Soldiers'' (2015)

In December 1947, immediately following the UN partition vote, the 1947–1948 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine

The 1947–1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine was the first phase of the 1947–1949 Palestine war. It broke out after the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted a resolution on 29 November 1947 recommending the adoption of the Pa ...

broke out between the Yishuv and Palestinian Arabs. The Irgun fought together with the Haganah and Lehi during that period. Notable operations in which they took part were the battle of Jaffa and the Jordanian siege on the Jewish Quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

. The Irgun's most controversial operation during this period, carried out alongside Lehi, was an assault on the Arab village of Deir Yassin

Deir Yassin ( ar, دير ياسين, Dayr Yāsīn) was a Palestinian Arab village of around 600 inhabitants about west of Jerusalem. Deir Yassin declared its neutrality during the 1948 Palestine war between Arabs and Jews. The village was razed ...

in which more than a hundred villagers and four of the attackers were killed. The event later became known as the Deir Yassin massacre

The Deir Yassin massacre took place on April 9, 1948, when around 130 fighters from the Zionist paramilitary groups Irgun and Lehi killed at least 107 Palestinian Arabs, including women and children, in Deir Yassin, a village of roughly 600 peopl ...

, though Irgun and Lehi sources would deny a massacre took place there. Begin also repeatedly threatened to declare independence if the Jewish Agency did not do so.

Throughout the period of the rebellion against the British and the civil war against the Arabs, Begin lived openly under a series of assumed names, often while sporting a beard. Begin would not come out of hiding until April 1948, when the British, who still maintained nominal authority over Palestine, were almost totally gone. During the period of revolt, Begin was the most wanted man in Palestine, and MI5

The Security Service, also known as MI5 ( Military Intelligence, Section 5), is the United Kingdom's domestic counter-intelligence and security agency and is part of its intelligence machinery alongside the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), G ...

placed a 'dead-or-alive' bounty of £10,000 on his head. Begin had been forced into hiding immediately prior to the declaration of revolt, when Aliza noticed that their house was being watched. He initially lived in a room in the Savoy Hotel, a small hotel in Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

whose owner was sympathetic to the Irgun's cause, and his wife and son were smuggled in to join him after two months. He decided to grow a beard and live openly under an assumed name rather than go completely into hiding. He was aided by the fact that the British authorities possessed only two photographs of his likeness, of which one, which they believed to be his military identity card, bore only a slight resemblance to him, according to Begin, and were fed misinformation by Yaakov Meridor

Ya'akov Meridor ( he, יעקב מרידור, born Yaakov Viniarsky on 29 September 1913, died 30 June 1995) was an Israeli politician, Irgun commander and businessman.

Biography

Yaakov Viniarsky (later Meridor) was born in the Polish town of Li ...

that he had had plastic surgery, and were thus confused over his appearance. Due to the British police conducting searches in the hotel's vicinity, he relocated to a Yemenite neighborhood in Petah Tikva

Petah Tikva ( he, פֶּתַח תִּקְוָה, , ), also known as ''Em HaMoshavot'' (), is a city in the Central District (Israel), Central District of Israel, east of Tel Aviv. It was founded in 1878, mainly by Haredi Judaism, Haredi Jews of ...

, and after a month, moved to the Hasidof neighborhood near Kfar Sirkin

Kfar Sirkin or Kefar Syrkin ( he, כְּפַר סִירְקִין) is a moshav in central Israel. Located south-east of Petah Tikva, it falls under the jurisdiction of Drom HaSharon Regional Council. In it had a population of .

History

Kfar Sirk ...

, where he pretended to be a lawyer named Yisrael Halperin. After the British searched the area but missed the street where his house was located, Begin and his family moved to a new home on a Tel Aviv side street, where he assumed the name Yisrael Sassover and masqueraded as a rabbi. Following the King David Hotel bombing, when the British searched the entire city of Tel Aviv, Begin evaded capture by hiding in a secret compartment in his home. In 1947, he moved to the heart of Tel Aviv and took the identity of Dr. Yonah Koenigshoffer, the name he found on an abandoned passport in a library.

In the years following the establishment of the State of Israel, the Irgun's contribution to precipitating British withdrawal became a hotly contested debate as different factions vied for control over the emerging narrative of Israeli independence. Begin resented his being portrayed as a belligerent dissident.

''Altalena'' and the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

After the

After the Israeli Declaration of Independence

The Israeli Declaration of Independence, formally the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel ( he, הכרזה על הקמת מדינת ישראל), was proclaimed on 14 May 1948 ( 5 Iyar 5708) by David Ben-Gurion, the Executive ...

on 14 May 1948 and the start of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

, Irgun continued to fight alongside Haganah and Lehi. On 15 May 1948, Begin broadcast a speech on radio declaring that the Irgun was finally moving out of its underground status. On 1 June Begin signed an agreement with the provisional government headed by David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the name ...

, where the Irgun agreed to formally disband and to integrate its force with the newly formed Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

(IDF), but was not truthful of the armaments aboard the ''Altalena

The ''Altalena'' Affair was a violent confrontation that took place in June 1948 by the newly created Israel Defense Forces against the Irgun (also known as IZL), one of the Jewish paramilitary groups that were in the process of merging to form ...

'' as it was scheduled to arrive during the cease-fire ordered by the United Nations and therefore would have put the State of Israel in peril as Britain was adamant the partition of Jewish and Arab Palestine would not occur. This delivery was the smoking gun Britain would need to urge the UN to end the partition action.

Intense negotiations between representatives of the provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

(headed by Ben-Gurion) and the Irgun (headed by Begin) followed the departure of ''Altalena'' from France. Among the issues discussed were logistics of the ship's landing and distribution of the cargo between the military organizations. Whilst there was agreement on the anchoring place of the ''Altalena'', there were differences of opinion about the allocation of the cargo. Ben-Gurion agreed to Begin's initial request that 20% of the weapons be dispatched to the Irgun's Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

Battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

, which was still fighting independently. His second request, however, that the remainder be transferred to the IDF to equip the newly incorporated Irgun battalions, was rejected by the Government representatives, who interpreted the request as a demand to reinforce an "army within an army."

The ''Altalena'' reached Kfar Vitkin in the late afternoon of Sunday, 20 June. Among the Irgun members waiting on the shore was Menachem Begin, who greeted the arrivals with great emotion. After the passengers had disembarked, members of the fishing village of Mikhmoret

Mikhmoret ( he, מִכְמֹרֶת, מכמורת, ''lit.'' Fishing net) is a moshav in central Israel. Located on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea around nine kilometres north of Netanya, it falls under the jurisdiction of Hefer Valley Region ...

helped unload the cargo of military equipment. Concomitantly with the events at Kfar Vitkin, the government had convened in Tel Aviv for its weekly meeting. Ben-Gurion reported on the meetings which had preceded the arrival of the ''Altalena'', and was adamant in his demand that Begin surrender and hand over all of the weapons:

We must decide whether to hand over power to Begin or to order him to cease his separate activities. If he does not do so, we will open fire! Otherwise, we must decide to disperse our own army.The debate ended in a resolution to empower the army to use force if necessary to overcome the Irgun and to confiscate the ship and its cargo. Implementation of this decision was assigned to the Alexandroni Brigade, commanded by Dan Even (Epstein), which the following day surrounded the Kfar Vitkin area. Dan Even issued the following ultimatum:

To: M. BeginThe ultimatum was made, according to Even, "in order not to give the Irgun commander time for lengthy considerations and to gain the advantage of surprise." Begin refused to respond to the ultimatum, and all attempts at mediation failed. Begin's failure to respond was a blow to Even's prestige, and a clash was now inevitable. Fighting ensued and there were a number of casualties. In order to prevent further bloodshed, the Kfar Vitkin settlers initiated negotiations between

By special order from the Chief of the General Staff of the Israel Defense Forces, I am empowered to confiscate the weapons and military materials which have arrived on the Israeli coast in the area of my jurisdiction in the name of the Israel Government. I have been authorized to demand that you hand over the weapons to me for safekeeping and to inform you that you should establish contact with the supreme command. You are required to carry out this order immediately. If you do not agree to carry out this order, I shall use all the means at my disposal in order to implement the order and to requisition the weapons which have reached shore and transfer them from private possession into the possession of the Israel government. I wish to inform you that the entire area is surrounded by fully armed military units and armored cars, and all roads are blocked. I hold you fully responsible for any consequences in the event of your refusal to carry out this order. The immigrants – unarmed – will be permitted to travel to the camps in accordance with your arrangements. You have ten minutes to give me your answer.

D.E., Brigade Commander

Yaakov Meridor

Ya'akov Meridor ( he, יעקב מרידור, born Yaakov Viniarsky on 29 September 1913, died 30 June 1995) was an Israeli politician, Irgun commander and businessman.

Biography

Yaakov Viniarsky (later Meridor) was born in the Polish town of Li ...

(Begin's deputy) and Dan Even, which ended in a general ceasefire and the transfer of the weapons on shore to the local IDF commander.

Begin had meanwhile boarded the ''Altalena'', which was headed for Tel Aviv where the Irgun had more supporters. Many Irgun members, who joined the IDF earlier that month, left their bases and concentrated on the Tel Aviv beach. A confrontation between them and the IDF units started. In response, Ben-Gurion ordered

Begin had meanwhile boarded the ''Altalena'', which was headed for Tel Aviv where the Irgun had more supporters. Many Irgun members, who joined the IDF earlier that month, left their bases and concentrated on the Tel Aviv beach. A confrontation between them and the IDF units started. In response, Ben-Gurion ordered Yigael Yadin

Yigael Yadin ( he, יִגָּאֵל יָדִין ) (20 March 1917 – 28 June 1984) was an Israeli archeologist, soldier and politician. He was the second Chief of Staff of the Israel Defense Forces and Deputy Prime Minister from 1977 to 1981.

B ...

(acting Chief of Staff) to concentrate large forces on the Tel Aviv beach and to take the ship by force. Heavy guns were transferred to the area and at four in the afternoon, Ben-Gurion ordered the shelling of the ''Altalena''. One of the shells hit the ship, which began to burn. Yigal Allon

Yigal Allon ( he, יגאל אלון; 10 October 1918 – 29 February 1980) was an Israeli politician, commander of the Palmach, and general in the Israel Defense Forces, IDF. He served as one of the leaders of Ahdut HaAvoda party and the Labor P ...

, commander of the troops on the shore, later claimed only five or six shells were fired, as warning shots, and the ship was hit by accident.

There was danger that the fire would spread to the holds which contained explosives, and Captain Monroe Fein

The ''Altalena'' Affair was a violent confrontation that took place in June 1948 by the newly created Israel Defense Forces against the Irgun (also known as IZL), one of the Jewish paramilitary groups that were in the process of merging to for ...

ordered all aboard to abandon ship. People jumped into the water, whilst their comrades on shore set out to meet them on rafts. Although Captain Fein flew the white flag of surrender, automatic fire continued to be directed at the unarmed survivors swimming in the water. Begin, who was on deck, agreed to leave the ship only after the last of the wounded had been evacuated. Sixteen Irgun fighters were killed in the confrontation with the army (all but three were veteran members and not newcomers in the ship); six were killed in the Kfar Vitkin area and ten on Tel Aviv beach. Three IDF soldiers were killed: two at Kfar Vitkin and one in Tel Aviv.

After the shelling of the ''Altalena'', more than 200 Irgun fighters were arrested. Most of them were released several weeks later, with the exception of five senior commanders (Moshe Hason, Eliyahu Lankin

Eliyahu Lankin ( he, אליהו לנקין, 25 September 1914 – 10 August 1994) was a Revisionist Zionist activist, Irgun member and an Israeli politician.

Biography

Eliyahu Lankin was born in Gomel, and moved with his family to Manchuria at th ...

, Yaakov Meridor

Ya'akov Meridor ( he, יעקב מרידור, born Yaakov Viniarsky on 29 September 1913, died 30 June 1995) was an Israeli politician, Irgun commander and businessman.

Biography

Yaakov Viniarsky (later Meridor) was born in the Polish town of Li ...

, Bezalel Amitzur, and Hillel Kook

Hillel Kook ( he, הלל קוק, 24 July 1915 –18 August 2001), also known as Peter Bergson (Hebrew: פיטר ברגסון), was a Revisionist Zionist activist and politician.

Kook led the Irgun's efforts in the United States during World ...

), who were detained for more than two months, until 27 August 1948. Begin agreed the Irgun soldiers would be fully integrated with the IDF and not kept in separate units.

About a year later, ''Altalena'' was refloated, towed 15 miles out to sea and sunk.

Political career

Herut opposition years

In August 1948, Begin and members of the Irgun High Command emerged from the underground and formed the right-wing political party

In August 1948, Begin and members of the Irgun High Command emerged from the underground and formed the right-wing political party Herut

Herut ( he, חֵרוּת, ''Freedom'') was the major conservative nationalist political party in Israel from 1948 until its formal merger into Likud in 1988. It was an adherent of Revisionist Zionism.

History

Herut was founded by Menachem Begin ...

("Freedom") party. The move countered the weakening attraction for the earlier revisionist party, Hatzohar

Hatzohar (, an acronym for ''HaTzionim HaRevizionistim'' (), lit. ''The Revisionist Zionists''), officially Brit HaTzionim HaRevizionistim (, lit. ''Union of Revisionist Zionists'') was a Revisionist Zionism, Revisionist Zionist organization and L ...

, founded by his late mentor Ze'ev Jabotinsky

Ze'ev Jabotinsky ( he, זְאֵב זַ׳בּוֹטִינְסְקִי, ''Ze'ev Zhabotinski'';, ''Wolf Zhabotinski'' 17 October 1880 – 3 August 1940), born Vladimir Yevgenyevich Zhabotinsky, was a Russian Jewish Revisionist Zionist leade ...

. Revisionist 'purists' alleged nonetheless that Begin was out to steal Jabotinsky's mantle and ran against him with the old party. The Herut party can be seen as the forerunner of today's Likud

Likud ( he, הַלִּיכּוּד, HaLikud, The Consolidation), officially known as Likud – National Liberal Movement, is a major centre-right to right-wing political party in Israel. It was founded in 1973 by Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon ...

.

In November 1948, Begin visited the US on a campaigning trip. During his visit, a letter signed by Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

, Sidney Hook

Sidney Hook (December 20, 1902 – July 12, 1989) was an American philosopher of pragmatism known for his contributions to the philosophy of history, the philosophy of education, political theory, and ethics. After embracing communism in his youth ...

, Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (, , ; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor. She is widely considered to be one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century.

Arendt was born ...

, and other prominent Americans and several rabbis was published which described Begin's Herut party as "terrorist, right-wing chauvinist organization in Palestine," "closely akin in its organization, methods, political philosophy and social appeal to the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

and Fascist parties" and accused his group (along with the smaller, militant, Stern Gang

Lehi (; he, לח"י – לוחמי חרות ישראל ''Lohamei Herut Israel – Lehi'', "Fighters for the Freedom of Israel – Lehi"), often known pejoratively as the Stern Gang,"This group was known to its friends as LEHI and to its enemie ...

) of preaching "racial superiority" and having "inaugurated a reign of terror in the Palestine Jewish community".

In the first elections in 1949, Herut, with 11.5 percent of the vote, won 14 seats, while Hatzohar failed to break the threshold and disbanded shortly thereafter. This provided Begin with legitimacy as the leader of the Revisionist stream of Zionism. During the 1950s Begin was banned from entering the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, with British government documents describing him as "former leader of the notorious terrorist organisation Irgun".

Between 1948 and 1977, under Begin, Herut and the alliances it formed (Gahal

Gahal ( he, גח"ל, an acronym for ''Gush Herut–Liberalim'' (Hebrew: ), ''lit.'' ''Freedom–Liberals Bloc'') was the main right-leaning political alliance in Israel, ranging from the centre-right to right-wing, from its founding in 1965 until ...

in 1965 and Likud

Likud ( he, הַלִּיכּוּד, HaLikud, The Consolidation), officially known as Likud – National Liberal Movement, is a major centre-right to right-wing political party in Israel. It was founded in 1973 by Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon ...

in 1973) formed the main opposition to the dominant Mapai

Mapai ( he, מַפָּא"י, an acronym for , ''Mifleget Poalei Eretz Yisrael'', lit. "Workers' Party of the Land of Israel") was a democratic socialist political party in Israel, and was the dominant force in Israeli politics until its merger in ...

and later the Alignment

Alignment may refer to:

Archaeology

* Alignment (archaeology), a co-linear arrangement of features or structures with external landmarks

* Stone alignment, a linear arrangement of upright, parallel megalithic standing stones

Biology

* Structu ...

(the forerunners of today's Labor Party) in the Knesset

The Knesset ( he, הַכְּנֶסֶת ; "gathering" or "assembly") is the unicameral legislature of Israel. As the supreme state body, the Knesset is sovereign and thus has complete control of the entirety of the Israeli government (with ...

; Herut adopted a radical nationalistic agenda committed to the irredentist

Irredentism is usually understood as a desire that one state annexes a territory of a neighboring state. This desire is motivated by ethnic reasons (because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to the population of the parent sta ...

idea of Greater Israel

Greater Israel ( he, ארץ ישראל השלמה; ''Eretz Yisrael Hashlema'') is an expression, with several different biblical and political meanings over time. It is often used, in an irredentist fashion, to refer to the historic or desired bo ...

that usually included Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

. During those years, Begin was systematically delegitimized by the ruling party, and was often personally derided by Ben-Gurion who refused to either speak to or refer to him by name. Ben-Gurion famously coined the phrase 'without Herut and Maki

Maki may refer to:

People

*Mäki, a Finnish surname (includes a list of people with the name)

*Maki (name), a Japanese given name and surname (includes a list of people with the name)

Places

*Maki, Ravar, Kerman Province, Iran

*Maki, Rigan, Ke ...

' (Maki was the communist party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. A ...

), referring to his refusal to consider them for coalition, effectively pushing both parties and their voters beyond the margins of political consensus.

The personal animosity between Ben-Gurion and Begin, going back to the hostilities over the Altalena Affair, underpinned the political dichotomy between Mapai and Herut. Begin was a keen critic of Mapai, accusing it of coercive

Coercion () is compelling a party to act in an involuntary manner by the use of threats, including threats to use force against a party. It involves a set of forceful actions which violate the free will of an individual in order to induce a desi ...

Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, fo ...

and deep-rooted institutional corruption. Drawing on his training as a lawyer in Poland, he preferred wearing a formal suit and tie and evincing the dry demeanor of a legislator to the socialist informality of Mapai, as a means of accentuating their differences.

One of the fiercest confrontations between Begin and Ben-Gurion revolved around the Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany

The Reparations Agreement between Israel and the Federal Republic of Germany ( German: ''Luxemburger Abkommen'' "Luxembourg Agreement" or ''Wiedergutmachungsabkommen'' "''Wiedergutmachung'' Agreement", Hebrew: ''הסכם השילומים'' ''Hesk ...

, signed in 1952. Begin vehemently opposed the agreement, claiming that it was tantamount to a pardon of Nazi crimes against the Jewish people. While the agreement was debated in the Knesset

The Knesset ( he, הַכְּנֶסֶת ; "gathering" or "assembly") is the unicameral legislature of Israel. As the supreme state body, the Knesset is sovereign and thus has complete control of the entirety of the Israeli government (with ...

in January 1952, he led a demonstration in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

attended by some 15,000 people, and gave a passionate and dramatic speech in which he attacked the government and called for its violent overthrow. Referring to the Altalena Affair, Begin stated that "when you fired at me with cannon, I gave the order; 'Don't eturn fire' Today I will give the order, 'Do!'" Incited by his speech, the crowd marched towards the Knesset (then at the Frumin Building on King George Street) and threw stones at the windows, and at police as they intervened. After five hours of rioting, police managed to suppress the riots using water cannons and tear gas. Hundreds were arrested, while some 200 rioters, 140 police officers, and several Knesset members were injured. Many held Begin personally responsible for the violence, and he was consequently barred from the Knesset for several months. His behavior was strongly condemned in mainstream public discourse, reinforcing his image as a provocateur. The vehemence of Revisionist opposition was deep; in March 1952, during the ongoing reparations negotiations, a parcel bomb addressed to Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (; 5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a Germany, German statesman who served as the first Chancellor of Germany, chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the fir ...

, the sitting West German

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

, was intercepted at a German post office. While being defused, the bomb exploded, killing one sapper

A sapper, also called a pioneer (military), pioneer or combat engineer, is a combatant or soldier who performs a variety of military engineering duties, such as breaching fortifications, demolitions, bridge-building, laying or clearing minefie ...

and injuring two others. Five Israelis, all former members of Irgun, were later arrested in Paris for their involvement in the plot. Chancellor Adenauer decided to keep secret the involvement of Israeli opposition party members in the plot, thus avoiding Israeli embarrassment and a likely backlash. The five Irgun conspirators were later extradited from both France and Germany, without charge, and sent back to Israel. Forty years after the assassination attempt, Begin was implicated as the organizer of the assassination attempt in a memoir written by one of the conspirators, Elieser Sudit.

Begin's impassioned rhetoric, laden with pathos and evocations of the Holocaust, appealed to many, but was deemed inflammatory and demagoguery

A demagogue (from Greek , a popular leader, a leader of a mob, from , people, populace, the commons + leading, leader) or rabble-rouser is a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, ...

by others.

Gahal and unity government

In the following years, Begin failed to gain electoral momentum, and Herut remained far behindLabor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

with a total of 17 seats until 1961. In 1965, Herut and the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

united to form the Gahal

Gahal ( he, גח"ל, an acronym for ''Gush Herut–Liberalim'' (Hebrew: ), ''lit.'' ''Freedom–Liberals Bloc'') was the main right-leaning political alliance in Israel, ranging from the centre-right to right-wing, from its founding in 1965 until ...

party under Begin's leadership, but failed again to win more seats in the election that year. In 1966, during Herut's party convention, he was challenged by the young Ehud Olmert

Ehud Olmert (; he, אֶהוּד אוֹלְמֶרְט, ; born 30 September 1945) is an Israeli politician and lawyer. He served as the 12th Prime Minister of Israel from 2006 to 2009 and before that as a cabinet minister from 1988 to 1992 and ...

, who called for his resignation. Begin announced that he would retire from party leadership, but soon reversed his decision when the crowd pleaded with him to stay. The day the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

started in June 1967, Gahal joined the national unity government

A national unity government, government of national unity (GNU), or national union government is a broad coalition government consisting of all parties (or all major parties) in the legislature, usually formed during a time of war or other nati ...

under Prime Minister Levi Eshkol

Levi Eshkol ( he, לֵוִי אֶשְׁכּוֹל ; 25 October 1895 – 26 February 1969), born Levi Yitzhak Shkolnik ( he, לוי יצחק שקולניק, links=no), was an Israeli statesman who served as the third Prime Minister of Israe ...

of the Alignment, resulting in Begin serving in the cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

for the first time, as a Minister without Portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister who does not head a particular ministry. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet w ...

. Rafi also joined the unity government at that time, with Moshe Dayan

Moshe Dayan ( he, משה דיין; 20 May 1915 – 16 October 1981) was an Israeli military leader and politician. As commander of the Jerusalem front in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Chief of Staff of the Israel Defense Forces (1953–1958) du ...

becoming Defense Minister. Gahal's arrangement lasted until August 1970, when Begin and Gahal quit the government, then led by Golda Meir

Golda Meir, ; ar, جولدا مائير, Jūldā Māʾīr., group=nb (born Golda Mabovitch; 3 May 1898 – 8 December 1978) was an Israeli politician, teacher, and ''kibbutznikit'' who served as the fourth prime minister of Israel from 1969 to 1 ...

due to disagreements over the Rogers Plan

The Rogers Plan (also known as Deep Strike) was a framework proposed by United States Secretary of State William P. Rogers to achieve an end to belligerence in the Arab–Israeli conflict following the Six-Day War and the continuing War of Attr ...