Matthew Murray on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Matthew Murray (1765 – 20 February 1826) was an English

In 1799

In 1799

Matthew Murray died on 20 February 1826, at the age of sixty. He was buried in St. Matthew's Churchyard, Holbeck. His tomb was surmounted by a

Matthew Murray died on 20 February 1826, at the age of sixty. He was buried in St. Matthew's Churchyard, Holbeck. His tomb was surmounted by a

Holbeck Urban Village, Leeds

Illustrated page on Murray and his work

''The Guardian''

The Northerner: Article on Murray and Leeds

Leeds Engine Builders

England's Biggest Locomotive Building City

Matthew Murray {{DEFAULTSORT:Murray, Matthew 1765 births 1826 deaths English railway mechanical engineers British railway pioneers Engineers from Tyne and Wear English inventors Locomotive builders and designers Machine tool builders Millwrights People from Newcastle upon Tyne People of the Industrial Revolution

steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be trans ...

and machine tool manufacturer, who designed and built the first commercially viable steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a locomotive that provides the force to move itself and other vehicles by means of the expansion of steam. It is fuelled by burning combustible material (usually coal, oil or, rarely, wood) to heat water in the locomot ...

, the twin cylinder ''Salamanca

Salamanca () is a city in western Spain and is the capital of the Province of Salamanca in the autonomous community of Castile and León. The city lies on several rolling hills by the Tormes River. Its Old City was declared a UNESCO World Heritag ...

'' in 1812. He was an innovative designer in many fields, including steam engines, machine tool

A machine tool is a machine for handling or machining metal or other rigid materials, usually by cutting, boring, grinding, shearing, or other forms of deformations. Machine tools employ some sort of tool that does the cutting or shaping. All m ...

s and machinery

A machine is a physical system using power to apply forces and control movement to perform an action. The term is commonly applied to artificial devices, such as those employing engines or motors, but also to natural biological macromolecule ...

for the textile industry

The textile industry is primarily concerned with the design, production and distribution of yarn, cloth and clothing. The raw material may be natural, or synthetic using products of the chemical industry.

Industry process

Cotton manufacturi ...

.

Early years

Little is known about Matthew Murray's early years. He was born inNewcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

in 1765. He left school at fourteen and was apprenticed to be either a blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from #Other metals, other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such ...

or a whitesmith A whitesmith is a metalworker who does finishing work on iron and steel such as filing, lathing, burnishing or polishing.

The term also refers to a person who works with "white" or light-coloured metals, and is sometimes used as a synonym for tinsmi ...

. In 1785, when he concluded his apprenticeship, he married Mary Thompson (1764–1836) of Whickham

Whickham is a village in Tyne and Wear, North East England. It is in the Metropolitan Borough of Gateshead. The village is on high ground overlooking the River Tyne and south-west of Newcastle upon Tyne. It was formerly governed under the histor ...

, County Durham. The following year he moved to Stockton and began work as a journeyman mechanic at the flax mill

Flax mills are mills which process flax. The earliest mills were developed for spinning yarn for the linen industry.

John Kendrew (an optician) and Thomas Porthouse (a clockmaker), both of Darlington developed the process from Richard Ar ...

of John Kendrew

Sir John Cowdery Kendrew, (24 March 1917 – 23 August 1997) was an English biochemist, crystallographer, and science administrator. Kendrew shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Max Perutz, for their work at the Cavendish La ...

in Darlington

Darlington is a market town in the Borough of Darlington, County Durham, England. The River Skerne flows through the town; it is a tributary of the River Tees. The Tees itself flows south of the town.

In the 19th century, Darlington underwen ...

, where the mechanical spinning of flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. Textiles made from flax are known in ...

had been invented..

Murray and his wife, Mary, had three daughters and a son, also called Matthew..

Leeds

In 1789, due to a lack of trade in the Darlington flax mills, Murray and his family moved toLeeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by populati ...

to work for John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longes ...

, who was to become a prominent flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. Textiles made from flax are known in ...

manufacturer. John Marshall had rented a small mill at Adel, for the purpose of manufacture but also to develop a pre-existing flax-spinning machine, with the aid of Matthew Murray. After some trial and error, to overcome the problem of breakages in the flax twine during the spinning of the flax, sufficient improvements were made to enable John Marshall to undertake the construction of a new mill at Holbeck in 1791, Murray was in charge of the installation. The installation included new flax-spinning machines of his own design, which Murray patented in 1790. In 1793 Murray took out a second patent on a design for "Instruments and Machines for Spinning Fibrous Materials". His patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A p ...

included a carding

Carding is a mechanical process that disentangles, cleans and intermixes fibres to produce a continuous web or sliver (textiles), sliver suitable for subsequent processing. This is achieved by passing the fibres between differentially moving su ...

engine and a spinning machine that introduced the new technique of "wet spinning" flax, which revolutionised the flax trade.

Murray maintained the machinery for Marshall's mills and made improvements that pleased his employer. At this stage it seems that Murray was the chief engineer in the mill.

Fenton, Murray and Wood

Industry in the Leeds area was developing fast and it became apparent that there was an opportunity for a firm of general engineers and millwrights to set up. Therefore, in 1795, Murray went into partnership with David Wood (1761–1820) and set up a factory at Mill Green, Holbeck. There were several mills in the vicinity and the new firm supplied machinery to them. The firm was so successful that in 1797 it moved to larger premises at Water Lane, Holbeck. The firm welcomed two new partners at this point; James Fenton (previously Marshall's partner) and William Lister (a millwright ofBramley, Leeds

Bramley is a district in west Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It is part of the City of Leeds Ward of Bramley and Stanningley with a population of 21,334 at the 2011 Census. The area is an old industrial area with much 19th century archit ...

). The firm became known as Fenton, Murray and Wood

Fenton, Murray and Jackson was an engineering company at the Round Foundry off Water Lane in Holbeck, Leeds, West Yorkshire, England.

Fenton, Murray and Wood

Fenton Murray and Wood was founded in the 1790s by ironfounder Matthew Murray and ...

. Murray was the technical innovator and in charge of obtaining orders; Wood was in charge of day-to-day running of the works; Fenton was the accountant.

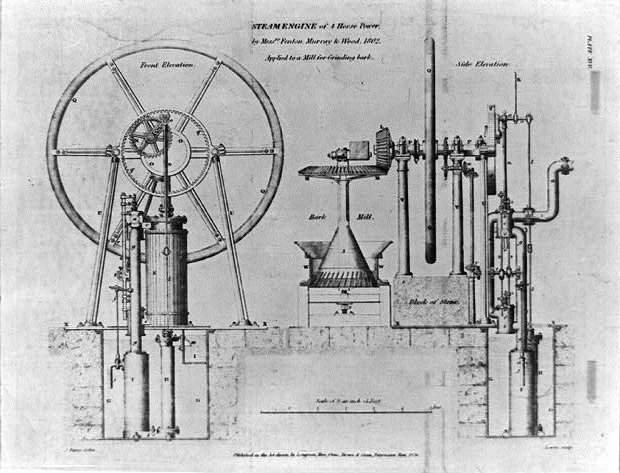

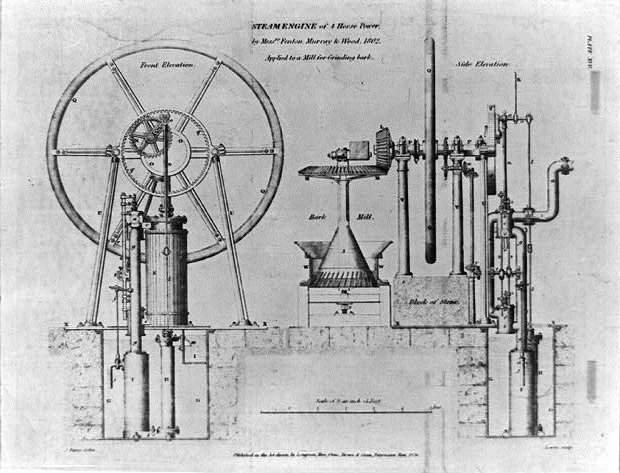

Steam engine manufacture

Although the firm still served the textile industry, Murray began to consider how the design of steam engines could be improved. He wanted to make them simpler, lighter, and more compact. He also wanted the steam engine to be a self-contained unit that could readily be assembled on site with pre-determined accuracy. Many existing engines suffered from faulty assembly, which took much effort to correct. One problem that Murray faced was thatJames Pickard

James Pickard was an English inventor. He modified the Newcomen engine in a manner that it could deliver a rotary motion. His solution, which he patented in 1780, involved the combined use of a crank and a flywheel.

James Watt's company Boulto ...

had already patented the crank and flywheel method of converting linear motion to circular motion. Murray ingeniously got round this difficulty by introducing a Tusi couple

The Tusi couple is a mathematical device in which a small circle rotates inside a larger circle twice the diameter of the smaller circle. Rotations of the circles cause a point on the circumference of the smaller circle to oscillate back and fort ...

hypocycloidal

In geometry, a hypocycloid is a special plane curve generated by the trace of a fixed point on a small circle that rolls within a larger circle. As the radius of the larger circle is increased, the hypocycloid becomes more like the cycloid crea ...

straight line mechanism. This consisted of a large fixed ring with internal teeth. Around the inside of this ring a smaller gear wheel, with half the outer one's diameter, would roll driven by the piston rod of the steam engine, which was attached to the gear's rim. As the piston rod moved backwards and forwards in a straight line, its linear motion would be converted into circular motion by the gear wheel. The gear wheel's bearing was attached to a crank on the flywheel shaft. When he used the hypocycloidal straight line mechanism he was able to build engines that were more compact and lightweight than previous ones. However, Murray ceased to use this type of motion as soon as Pickard's patent expired.

In 1799

In 1799 William Murdoch

William Murdoch (sometimes spelled Murdock) (21 August 1754 – 15 November 1839) was a Scottish engineer and inventor.

Murdoch was employed by the firm of Boulton & Watt and worked for them in Cornwall, as a steam engine erector for ten yea ...

, who worked for the firm of Boulton and Watt

Boulton & Watt was an early British engineering and manufacturing firm in the business of designing and making marine and stationary steam engines. Founded in the English West Midlands around Birmingham in 1775 as a partnership between the Engli ...

, invented a new type of steam valve, called the D slide valve

The slide valve is a rectilinear valve used to control the admission of steam into and emission of exhaust from the cylinder of a steam engine.

Use

In the 19th century, most steam locomotives used slide valves to control the flow of steam into ...

. This, in effect, slid backwards and forwards admitting steam to one end of the cylinder then the other. Matthew Murray improved the working of these valves by driving them with an eccentric gear attached to the rotating shaft of the engine.

Murray also patented an automatic damper that controlled the furnace draft depending on the boiler pressure, and he designed a mechanical hopper that automatically fed fuel to the firebox. Murray was the first to adopt the placing of the piston in a horizontal position in the steam engine. He expected very high standards of workmanship from his employees, and the result was that Fenton, Murray and Wood produced machinery of a very high precision. He designed a special planing machine

A planer is a type of metalworking machine tool that uses linear relative motion between the workpiece and a single-point cutting tool to cut the work piece.Parker, Dana T. ''Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in Wo ...

for planing the faces of the slide valves. Apparently this machine was kept in a locked room, to which only certain employees were allowed access.

The Murray Hypocycloidal Engine in Thinktank museum, Birmingham, England, is the third-oldest working engine in the world, and the oldest working engine with a hypocycloidal straight line mechanism.

The Round Foundry

As a result of the high quality of his steam engines, sales increased a great deal and it became apparent that a new engine assembly shop was required. Murray designed this himself, and produced a huge three-storeyed circular building known as theRound Foundry

The Round Foundry is a former engineering works off Water Lane in Holbeck, Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. Founded in the late 18th century, the building was developed into the Round Foundry Media Centre in 2005.

History

The Round Foundry was ...

. This contained a centrally mounted steam engine to power all of the machines in the building. Murray also built a house for himself adjoining the works. The design of this was pioneering, as each room was heated by steam pipes, so that it became known locally as Steam Hall.

Hostility of Boulton and Watt

The success thatFenton, Murray and Wood

Fenton, Murray and Jackson was an engineering company at the Round Foundry off Water Lane in Holbeck, Leeds, West Yorkshire, England.

Fenton, Murray and Wood

Fenton Murray and Wood was founded in the 1790s by ironfounder Matthew Murray and ...

enjoyed because of the high quality of their workmanship attracted the hostility of competitors, Boulton and Watt

Boulton & Watt was an early British engineering and manufacturing firm in the business of designing and making marine and stationary steam engines. Founded in the English West Midlands around Birmingham in 1775 as a partnership between the Engli ...

. The latter firm sent employees William Murdoch

William Murdoch (sometimes spelled Murdock) (21 August 1754 – 15 November 1839) was a Scottish engineer and inventor.

Murdoch was employed by the firm of Boulton & Watt and worked for them in Cornwall, as a steam engine erector for ten yea ...

and Abraham Storey to visit Murray, ostensibly on a courtesy visit, but in reality to spy on his production methods. Murray, rather foolishly, welcomed them, and showed them everything. On their return they informed their employers that Murray's casting work and forging work were much superior to their own, and efforts were made to adopt many of Murray's production methods. There was also an attempt by the firm of Boulton and Watt

Boulton & Watt was an early British engineering and manufacturing firm in the business of designing and making marine and stationary steam engines. Founded in the English West Midlands around Birmingham in 1775 as a partnership between the Engli ...

to obtain information from an employee of Fenton, Murray and Wood by bribery. Finally, James Watt jnr purchased land adjacent to the workshop in an attempt to prevent the firm from expanding.

Boulton and Watt successfully challenged two of Murray's patents. Murray's patent of 1801, for improved air pump

An air pump is a pump for pushing air. Examples include a bicycle pump, pumps that are used to aerate an aquarium or a pond via an airstone; a gas compressor used to power a pneumatic tool, air horn or pipe organ; a bellows used to encourage ...

s and other innovations, and of 1802, for a self-contained compact engine with a new type of slide valve, were contested and overturned. In both cases, Murray had made the mistake of including too many improvements together in the same patent. This meant that if any one improvement were found to have infringed a copyright, the whole patent would be invalidated.

Despite the manoeuvrings of Boulton and Watt, the firm of Fenton, Murray and Wood became serious rivals to them, attracting many orders.

Middleton Railway

In 1812 the firm suppliedJohn Blenkinsop

John Blenkinsop (1783 – 22 January 1831) was an English mining engineer and an inventor of steam locomotives, who designed the first practical railway locomotive.

He was born in Felling, County Durham, the son of a stonemason and was app ...

, manager of Brandling's Middleton Colliery, near Leeds, with the first twin-cylinder steam locomotive (''Salamanca

Salamanca () is a city in western Spain and is the capital of the Province of Salamanca in the autonomous community of Castile and León. The city lies on several rolling hills by the Tormes River. Its Old City was declared a UNESCO World Heritag ...

''). This was the first commercially successful steam locomotive.

The double cylinder was Murray's invention, he paid Richard Trevithick

Richard Trevithick (13 April 1771 – 22 April 1833) was a British inventor and mining engineer. The son of a mining captain, and born in the mining heartland of Cornwall, Trevithick was immersed in mining and engineering from an early age. He w ...

a royalty for the use of his patented high pressure steam system, but improved upon it, using two cylinders rather than one to give a smoother drive.

Because only a lightweight locomotive could work on cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

rails without breaking them, the total load they were capable of hauling was very much limited.

In 1811, John Blenkinsop patented a toothed wheel and rack rail system. The toothed wheel was driven by connecting rod

A connecting rod, also called a 'con rod', is the part of a piston engine which connects the piston to the crankshaft. Together with the crank, the connecting rod converts the reciprocating motion of the piston into the rotation of the cranksh ...

s, and meshed with a toothed rail at one side of the track. This was the first rack railway

A rack railway (also rack-and-pinion railway, cog railway, or cogwheel railway) is a steep grade railway with a toothed rack rail, usually between the running rails. The trains are fitted with one or more cog wheels or pinions that mesh with th ...

, and had a gauge of 4 ft 1½ ins.

Once a system had been devised for making malleable iron

Malleable iron is cast as white iron, the structure being a metastable carbide in a pearlitic matrix. Through an annealing heat treatment, the brittle structure as first cast is transformed into the malleable form. Carbon agglomerates into small ...

rails, around 1819, the rack and pinion motion became unnecessary, apart from later use on mountain railways

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually higher th ...

. However, until that time it enabled a small and lightweight locomotive to haul loads totalling at least 20 times its own weight. ''Salamanca'' was so successful that Murray made three more models. One of these was known as ''Lord Wellington'', and the others are said to have been named ''Prince Regent

A prince regent or princess regent is a prince or princess who, due to their position in the line of succession, rules a monarchy as regent in the stead of a monarch regnant, e.g., as a result of the sovereign's incapacity (minority or illness ...

'' and '' Marquis Wellington'', though there is no known contemporary mention of those two names. The third locomotive intended for Middleton was sent, at Blenkinsop's request, to the Kenton and Coxlodge Colliery waggonway near Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

, where it appears to have been known as ''Willington''. There it was seen by George Stephenson

George Stephenson (9 June 1781 – 12 August 1848) was a British civil engineer and mechanical engineer. Renowned as the "Father of Railways", Stephenson was considered by the Victorians a great example of diligent application and thirst for ...

, who modelled his own locomotive '' Blücher'' on it, minus the rack drive, and therefore much less effective.

After two of the locomotives exploded, killing their drivers, and the remaining two were increasingly unreliable after at least 20 years hard labour, the Middleton colliery eventually reverted to horse haulage in 1835. Rumour has it that one remaining locomotive was preserved for some years at the colliery, but was eventually scrapped.

Marine engines

In 1811 the firm made aTrevithick Trevithick ( ) is a Cornish surname, and may refer to:

* Francis Trevithick (1812–1877), one of the first locomotive engineers of the London and North Western Railway

* Jonathan Trevethick (1864–1939), New Zealand politician

* Paul Trevithic ...

-pattern high-pressure steam engine for John Wright, a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

of Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth (), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside town and unparished area in, and the main administrative centre of, the Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. A pop ...

, Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

. The engine was fitted to the paddle steamer ''l'Actif'', running out of Yarmouth. The ship was a captured privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

that had been purchased from the government. Paddle wheels

A paddle wheel is a form of waterwheel or impeller in which a number of paddles are set around the periphery of the wheel. It has several uses, of which some are:

* Very low-lift water pumping, such as flooding paddy fields at no more than about ...

were fitted to it and driven by the new engine. The ship was renamed ''Experiment'' and the engine was very successful, eventually being transferred to another boat, ''The Courier''.

In 1816 Francis B. Ogden, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

Consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throug ...

in Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

received two large twin-cylinder marine steam engines from Murray's firm. Ogden then patented the design as his own in America. It was widely copied there and used to propel the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses wer ...

s.

Textile innovations

Murray made important improvements to the machinery for heckling and spinningflax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. Textiles made from flax are known in ...

. Heckling was the preparation of flax for spinning by splitting and straightening the flax fibres. Murray's heckling machine gained him the gold medal of the Royal Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA), also known as the Royal Society of Arts, is a London-based organisation committed to finding practical solutions to social challenges. The RSA acronym is used m ...

in 1809. At the time when these inventions were made the flax trade was on the point of expiring, the spinners being unable to produce yarn

Yarn is a long continuous length of interlocked fibres, used in sewing, crocheting, knitting, weaving, embroidery, ropemaking, and the production of textiles. Thread is a type of yarn intended for sewing by hand or machine. Modern manufact ...

to a profit. The effect of his inventions was to reduce the cost of production, and improve the quality of the manufacture, thus establishing the British linen trade on a solid foundation. The production of flax-machinery became an important branch of manufacture at Leeds, large quantities being made for use at home as well as for exportation, giving employment to an increasing number of highly skilled mechanics.

Hydraulic presses

In 1814 Murray patented ahydraulic press

A hydraulic press is a machine press using a hydraulic cylinder to generate a compressive force. It uses the hydraulic equivalent of a mechanical lever, and was also known as a Bramah press after the inventor, Joseph Bramah, of England. He ...

for baling cloth, in which the upper and lower tables approached each other simultaneously. He improved upon the hydraulic presses invented by Joseph Bramah

Joseph Bramah (13 April 1748 – 9 December 1814), born Stainborough Lane Farm, Stainborough, in Barnsley, Yorkshire, was an English inventor and locksmith. He is best known for having improved the flush toilet and inventing the hydraulic pr ...

, and in 1825 designed a huge press for testing chain cables. His press, built for the Navy Board

The Navy Board (formerly known as the Council of the Marine or Council of the Marine Causes) was the commission responsible for the day-to-day civil administration of the Royal Navy between 1546 and 1832. The board was headquartered within the ...

, was 34 ft long and could exert a force of 1,000 tons. The press was completed just before Murray's death.

Death

Matthew Murray died on 20 February 1826, at the age of sixty. He was buried in St. Matthew's Churchyard, Holbeck. His tomb was surmounted by a

Matthew Murray died on 20 February 1826, at the age of sixty. He was buried in St. Matthew's Churchyard, Holbeck. His tomb was surmounted by a cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

obelisk made at the Round Foundry. His firm survived until 1843. Several prominent engineers were trained there, including Benjamin Hick

Benjamin Hick (1 August 1790 – 9 September 1842) was an English civil and mechanical engineer, art collector and patron; his improvements to the steam engine and invention of scientific tools were held in high esteem by the engineering p ...

, Charles Todd, David Joy and Richard Peacock

Richard Peacock (9 April 1820 – 3 March 1889) was an English engineer, one of the founders of locomotive manufacturer Beyer, Peacock and Company.

Early life and education

Born in Swaledale, Yorkshire, Richard Peacock was educated at Leeds G ...

.

It is a testament to the good design and workmanship that went into his steam engines, that several of his big mill engines ran for over eighty years, and one of them, installed second-hand at the locomotive repair works at King's Cross, ran for over a century.

Murray's only son Matthew (c.1793–1835) served an apprenticeship at the Round Foundry

The Round Foundry is a former engineering works off Water Lane in Holbeck, Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. Founded in the late 18th century, the building was developed into the Round Foundry Media Centre in 2005.

History

The Round Foundry was ...

and went to Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

; he founded an engineering business in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, where he died age 42..

References

Bibliography

* . * . * . Volume 4 of the series ''Industrial Archaeology''. * . * * . * . * .External links

Holbeck Urban Village, Leeds

Illustrated page on Murray and his work

''The Guardian''

The Northerner: Article on Murray and Leeds

Leeds Engine Builders

England's Biggest Locomotive Building City

Matthew Murray {{DEFAULTSORT:Murray, Matthew 1765 births 1826 deaths English railway mechanical engineers British railway pioneers Engineers from Tyne and Wear English inventors Locomotive builders and designers Machine tool builders Millwrights People from Newcastle upon Tyne People of the Industrial Revolution