Mary Anning on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 – 9 March 1847) was an English fossil collector,

Mary Anning was born in

Mary Anning was born in  Molly and Richard had ten children. The first child, also Mary, was born in 1794. She was followed by another daughter, who died almost at once; Joseph in 1796; and another son in 1798, who died in infancy. In December that year, the oldest child, (the first Mary) then four years old, died after her clothes caught fire, possibly while adding wood shavings to the fire. The incident was reported in the ''

Molly and Richard had ten children. The first child, also Mary, was born in 1794. She was followed by another daughter, who died almost at once; Joseph in 1796; and another son in 1798, who died in infancy. In December that year, the oldest child, (the first Mary) then four years old, died after her clothes caught fire, possibly while adding wood shavings to the fire. The incident was reported in the ''

By the late 18th century,

By the late 18th century,  Their first well-known find was in 1811 when Mary Anning was 12; her brother Joseph dug up a 4-foot

Their first well-known find was in 1811 when Mary Anning was 12; her brother Joseph dug up a 4-foot

In 1826, at the age of 27, Anning managed to save enough money to purchase a home with a glass store-front window for her shop, ''Anning's Fossil Depot''. The business had become important enough that the move was covered in the local paper, which noted that the shop had a fine ichthyosaur skeleton on display. Many geologists and fossil collectors from Europe and America visited her at Lyme, including the geologist

In 1826, at the age of 27, Anning managed to save enough money to purchase a home with a glass store-front window for her shop, ''Anning's Fossil Depot''. The business had become important enough that the move was covered in the local paper, which noted that the shop had a fine ichthyosaur skeleton on display. Many geologists and fossil collectors from Europe and America visited her at Lyme, including the geologist

By 1830, because of difficult economic conditions in Britain that reduced the demand for fossils, coupled with long gaps between major finds, Anning was having financial problems again. Her friend, the geologist Henry De la Beche assisted her by commissioning Georg Scharf to make a lithographic print based on De la Beche's watercolour painting, ''

By 1830, because of difficult economic conditions in Britain that reduced the demand for fossils, coupled with long gaps between major finds, Anning was having financial problems again. Her friend, the geologist Henry De la Beche assisted her by commissioning Georg Scharf to make a lithographic print based on De la Beche's watercolour painting, ''

Anning died from

Anning died from  After Anning's death, Henry De la Beche, president of the Geological Society, wrote a eulogy that he read to a meeting of the society and published in its quarterly transactions, the first such eulogy given for a woman. These were honours normally only accorded to fellows of the society, which did not admit women until 1904. The eulogy began:

After Anning's death, Henry De la Beche, president of the Geological Society, wrote a eulogy that he read to a meeting of the society and published in its quarterly transactions, the first such eulogy given for a woman. These were honours normally only accorded to fellows of the society, which did not admit women until 1904. The eulogy began:

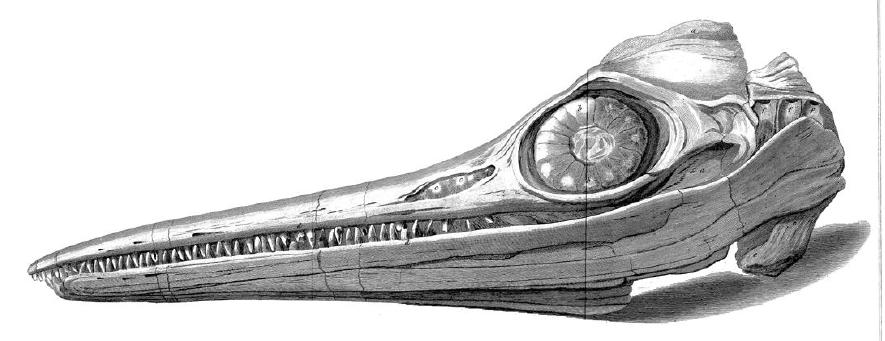

Anning's first famous discovery was made shortly after her father's death when she was still a child of about 12. In 1811 (some sources say 1810 or 1809) her brother Joseph found a skull, but failed to locate the rest of the animal. After Joseph told Anning to look between the cliffs at Lyme Regis and Charmouth, she found the skeleton— long in all—a few months later. The family hired workmen to dig it out in November that year, an event covered by the local press on 9 November, who identified the fossil as a crocodile.

Other

Anning's first famous discovery was made shortly after her father's death when she was still a child of about 12. In 1811 (some sources say 1810 or 1809) her brother Joseph found a skull, but failed to locate the rest of the animal. After Joseph told Anning to look between the cliffs at Lyme Regis and Charmouth, she found the skeleton— long in all—a few months later. The family hired workmen to dig it out in November that year, an event covered by the local press on 9 November, who identified the fossil as a crocodile.

Other

The Academy of Natural Sciences. Retrieved 23 September 2010. the find raised questions in scientific and religious circles about what the new science of geology was revealing about ancient life and the history of the Earth. Its notoriety increased when Sir Everard Home wrote a series of six papers, starting in 1814, describing it for the Royal Society. The papers never mentioned who had collected the fossil, and in the first one he even mistakenly credited the painstaking cleaning and preparation of the fossil performed by Anning to the staff at Bullock's museum. Perplexed by the creature, Home kept changing his mind about its classification, first thinking it was a kind of fish, then thinking it might have some kind of affinity with the duck-billed platypus (only recently known to science); finally in 1819 he reasoned it might be a kind of intermediate form between salamanders and lizards, which led him to propose naming it Proteo-Saurus. By then Charles Konig, an assistant curator of the British Museum, had already suggested the name ''Ichthyosaurus'' (fish lizard) for the specimen and that name stuck. Konig purchased the skeleton for the museum in 1819. The skull of the specimen is still in the possession of the

In the same 1821 paper he co-authored with Henry De la Beche on ichthyosaur anatomy, William Conybeare named and described the genus ''

In the same 1821 paper he co-authored with Henry De la Beche on ichthyosaur anatomy, William Conybeare named and described the genus '' In 1823, Anning discovered a second, much more complete plesiosaur skeleton, specimen BMNH 22656. When Conybeare presented his analysis of plesiosaur anatomy to a meeting of the Geological Society in 1824, he again failed to mention Anning by name, even though she had possibly collected both skeletons and had made the sketch of the second skeleton he used in his presentation. Conybeare's presentation was made at the same meeting at which William Buckland described the dinosaur ''

In 1823, Anning discovered a second, much more complete plesiosaur skeleton, specimen BMNH 22656. When Conybeare presented his analysis of plesiosaur anatomy to a meeting of the Geological Society in 1824, he again failed to mention Anning by name, even though she had possibly collected both skeletons and had made the sketch of the second skeleton he used in his presentation. Conybeare's presentation was made at the same meeting at which William Buckland described the dinosaur ''

Anning found what a contemporary newspaper article called an unrivalled specimen of ''

Anning found what a contemporary newspaper article called an unrivalled specimen of ''

Anning's discoveries became key pieces of evidence for

Anning's discoveries became key pieces of evidence for  Throughout the 20th century, beginning with H. A. Forde and his ''The Heroine of Lyme Regis: The Story of Mary Anning the Celebrated Geologist'' (1925), a number of writers saw Anning's life as inspirational. According to P. J. McCartney in ''Henry De la Beche: Observations on an Observer'' (1978), she was the basis of Terry Sullivan's lyrics to the 1908 song which, McCartney claimed, became the popular

Throughout the 20th century, beginning with H. A. Forde and his ''The Heroine of Lyme Regis: The Story of Mary Anning the Celebrated Geologist'' (1925), a number of writers saw Anning's life as inspirational. According to P. J. McCartney in ''Henry De la Beche: Observations on an Observer'' (1978), she was the basis of Terry Sullivan's lyrics to the 1908 song which, McCartney claimed, became the popular

In August 2018, a campaign called "''Mary Anning Rocks''" was formed by an 11-year-old school girl from Dorset, Evie Swire, supported by her mother Anya Pearson. The campaign was set up to remember Anning in her hometown of Lyme Regis by erecting a statue and creating a learning legacy in her name. Patrons and supporters include Professor Alice Roberts,

In August 2018, a campaign called "''Mary Anning Rocks''" was formed by an 11-year-old school girl from Dorset, Evie Swire, supported by her mother Anya Pearson. The campaign was set up to remember Anning in her hometown of Lyme Regis by erecting a statue and creating a learning legacy in her name. Patrons and supporters include Professor Alice Roberts,

dealer

Dealer may refer to:

Film and TV

* ''Dealers'' (film), a 1989 British film

* ''Dealers'' (TV series), a reality television series where five art and antique dealers bid on items

* ''The Dealer'' (film), filmed in 2008 and released in 2010

* ...

, and palaeontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

who became known around the world for the discoveries she made in Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

marine fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

beds in the cliffs along the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

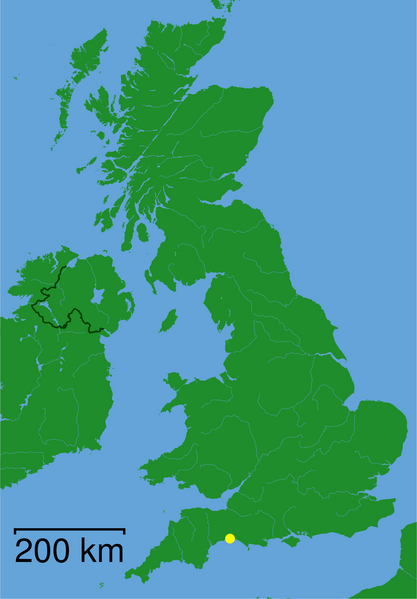

at Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset–Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and beaches on the Herita ...

in the county of Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset (unitary authority), Dors ...

in Southwest England. Anning's findings contributed to changes in scientific thinking about prehistoric life

The history of life on Earth traces the processes by which living and fossil organisms evolved, from the earliest emergence of life to present day. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago (abbreviated as ''Ga'', for ''gigaannum'') and evide ...

and the history of the Earth

The history of Earth concerns the development of planet Earth from its formation to the present day. Nearly all branches of natural science have contributed to understanding of the main events of Earth's past, characterized by constant geologi ...

.

Anning searched for fossils in the area's Blue Lias

The Blue Lias is a geological formation in southern, eastern and western England and parts of South Wales, part of the Lias Group. The Blue Lias consists of a sequence of limestone and shale layers, laid down in latest Triassic and early Jurassi ...

and Charmouth Mudstone

The Charmouth Mudstone Formation is a geological formation in England. It preserves fossils dating back to the early part of the Jurassic period (Sinemurian–Pliensbachian). It forms part of the lower Lias Group. It is most prominently exposed at ...

cliffs, particularly during the winter months when landslides exposed new fossils that had to be collected quickly before they were lost to the sea. Her discoveries included the first correctly identified ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, altho ...

skeleton when she was twelve years old; the first two nearly complete plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria (; Greek: πλησίος, ''plesios'', meaning "near to" and ''sauros'', meaning "lizard") or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared ...

skeletons; the first pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to ...

skeleton located outside Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

; and fish fossils. Her observations played a key role in the discovery that coprolite

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name is de ...

s, known as bezoar

A bezoar is a mass often found trapped in the gastrointestinal system, though it can occur in other locations. A pseudobezoar is an indigestible object introduced intentionally into the digestive system.

There are several varieties of bezoar, s ...

stones at the time, were fossilised faeces

Feces ( or faeces), known colloquially and in slang as poo and poop, are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. Feces contain a relati ...

, and she also discovered that belemnite

Belemnitida (or the belemnite) is an extinct order of squid-like cephalopods that existed from the Late Triassic to Late Cretaceous. Unlike squid, belemnites had an internal skeleton that made up the cone. The parts are, from the arms-most ...

fossils contained fossilised ink sac

An ink sac is an anatomical feature that is found in many cephalopod mollusks used to produce the defensive cephalopod ink. With the exception of nocturnal and very deep water cephalopods, all Coleoidea (squid, octopus and cuttlefish) which dwell ...

s like those of modern cephalopods.

Anning struggled financially for much of her life. As a woman, she was not eligible to join the Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

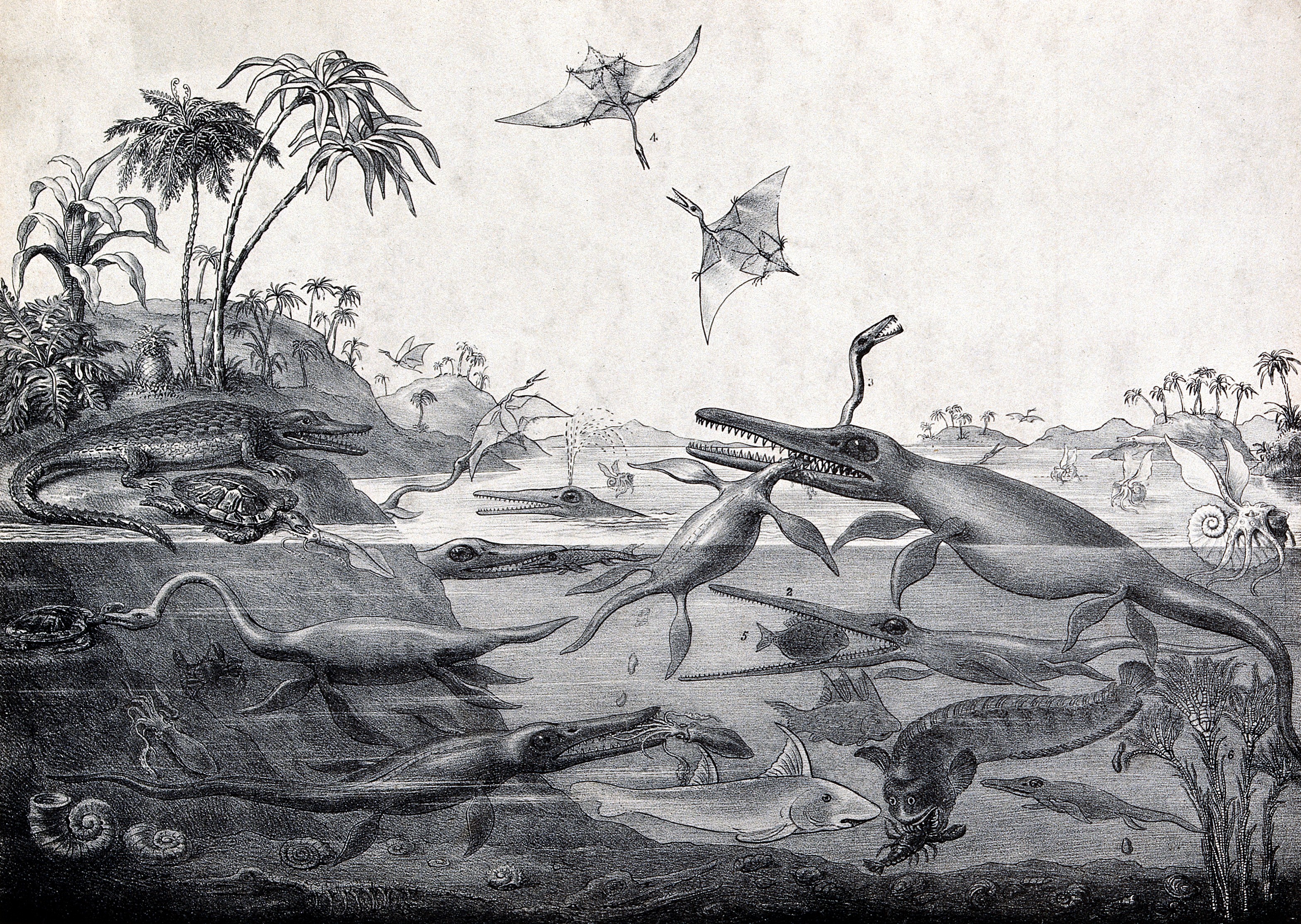

and she did not always receive full credit for her scientific contributions. However, her friend, geologist Henry De la Beche

Sir Henry Thomas De la Beche KCB, FRS (10 February 179613 April 1855) was an English geologist and palaeontologist, the first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, who helped pioneer early geological survey methods. He was the ...

, who painted ''Duria Antiquior

''Duria Antiquior, a more ancient Dorset'', was the first pictorial representation of a scene of prehistoric life based on evidence from fossil reconstructions, a genre now known as paleoart. The first version was a watercolour painted in 1830 b ...

'', the first widely circulated pictorial representation of a scene from prehistoric life derived from fossil reconstructions, based it largely on fossils Anning had found and sold prints of it for her benefit. Anning became well known in geological circles in Britain, Europe, and America, and was consulted on issues of anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

as well as fossil collecting. The only scientific writing of hers published in her lifetime appeared in the ''Magazine of Natural History

The ''Journal of Natural History'' is a scientific journal published by Taylor & Francis focusing on entomology and zoology. The journal was established in 1841 under the name ''Annals and Magazine of Natural History'' (''Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist.'') ...

'' in 1839, an extract from a letter that Anning had written to the magazine's editor questioning one of its claims.

After her death in 1847, Anning's unusual life story attracted increasing interest. An anonymous article about Anning's life was published in February 1865 in Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

' literary magazine '' All the Year Round''. The profile, "Mary Anning, The Fossil Finder," was long attributed to Dickens himself but, in 2014, historians of palaeontology Michael A. Taylor and Hugh S. Torrens identified Henry Stuart Fagan as the author, noting that Fagan's work was "neither original nor reliable" and "introduced errors into the Anning literature which are still problematic." Specifically, they noted that Fagan had largely and inaccurately plagiarised his article from an earlier account of Anning's life and work by Dorset native Henry Rowland Brown, from the second edition of Brown's 1859 guidebook, ''The Beauties of Lyme Regis.''

Life and career

Early childhood

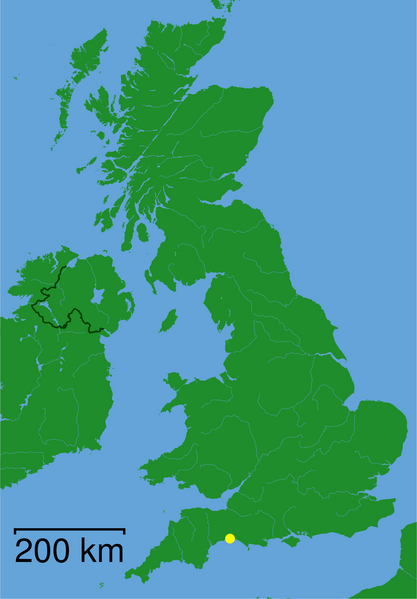

Mary Anning was born in

Mary Anning was born in Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset–Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and beaches on the Herita ...

in Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset (unitary authority), Dors ...

, England, on 21 May 1799. Her father, Richard Anning (''c''.1766–1810), was a cabinetmaker

A cabinet is a case or cupboard with shelves and/or drawers for storing or displaying items. Some cabinets are stand alone while others are built in to a wall or are attached to it like a medicine cabinet. Cabinets are typically made of wood (s ...

and carpenter who supplemented his income by mining the coastal cliff-side fossil beds near the town, and selling his finds to tourists; her mother was Mary Moore (''c''.1764–1842) known as Molly. Anning's parents married on 8 August 1793 in Blandford Forum

Blandford Forum ( ), commonly Blandford, is a market town in Dorset, England, sited by the River Stour, Dorset, River Stour about northwest of Poole. It was the administrative headquarters of North Dorset District until April 2019, when this ...

and moved to Lyme, living in a house built on the town's bridge. They attended the Dissenter

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, and ...

chapel on Coombe Street, whose worshippers initially called themselves independents and later became known as Congregationalists

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

. Shelley Emling

Shelley Emling is an American journalist. She was born in Missouri. Later she grew up in Dallas, Texas. She went to the University of Texas and started her journalism career at UPI.

Personal life

Shelley met her husband, Scott Norvell in Texas ...

writes that the family lived so near to the sea that the same storms that swept along the cliffs to reveal the fossils sometimes flooded the Annings' home, on one occasion forcing them to crawl out of an upstairs bedroom window to avoid drowning.

Bath Chronicle

The ''Bath Chronicle'' is a weekly newspaper, first published under various titles before 1760 in Bath, England. Prior to September 2007, it was published daily. The ''Bath Chronicle'' serves Bath, northern Somerset and west Wiltshire.

History ...

'' on 27 December 1798: "A child, four years of age of Mr. R. Anning, a cabinetmaker of Lyme, was left by the mother for about five minutes ... in a room where there were some shavings ... The girl's clothes caught fire and she was so dreadfully burnt as to cause her death."

When Anning was born five months later, she was thus named Mary after her dead sister. More children were born after her, but none of them survived more than a year or two. Only the second Mary Anning and her brother Joseph, who was three years older than her, survived to adulthood. The high childhood mortality rate for the Anning family was not unusual. Almost half the children born in the UK in the 19th century died before the age of five, and in the crowded living conditions of early 19th-century Lyme Regis, infant deaths from diseases like smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

were common.

On 19 August 1800, when Anning was 15 months old, an event occurred that became part of local lore. She was being held by a neighbour, Elizabeth Haskings, who was standing with two other women under an elm tree watching an equestrian show being put on by a travelling company of horsemen when lightning struck the tree – killing all three women below. Onlookers rushed the infant home where she was revived in a bath of hot water. A local doctor declared her survival miraculous. Anning's family said she had been a sickly baby before the event but afterwards she seemed to blossom. For years afterwards members of her community would attribute the child's curiosity, intelligence and lively personality to the incident.

Anning's education was extremely limited, but she was able to attend a Congregationalist Sunday school

A Sunday school is an educational institution, usually (but not always) Christian in character. Other religions including Buddhism, Islam, and Judaism have also organised Sunday schools in their temples and mosques, particularly in the West.

Su ...

, where she learned to read and write. Congregationalist doctrine, unlike that of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

at the time, emphasised the importance of education for the poor. Her prized possession was a bound volume of the ''Dissenters' Theological Magazine and Review'', in which the family's pastor, the Reverend James Wheaton, had published two essays, one insisting that God had created the world in six days, the other urging dissenters to study the new science of geology.

Fossils as a family business

By the late 18th century,

By the late 18th century, Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset–Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and beaches on the Herita ...

had become a popular seaside resort, especially after 1792 when the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

made travel to the European mainland dangerous for the English gentry, and increasing numbers of wealthy and middle-class tourists were arriving there. Even before Anning's time, locals supplemented their income by selling what were called "curios" to visitors. These were fossils with colourful local names such as "snake-stones" (ammonites

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) ...

), "devil's fingers" (belemnite

Belemnitida (or the belemnite) is an extinct order of squid-like cephalopods that existed from the Late Triassic to Late Cretaceous. Unlike squid, belemnites had an internal skeleton that made up the cone. The parts are, from the arms-most ...

s), and "verteberries" (vertebrae

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic i ...

), to which were sometimes attributed medicinal and mystical properties. Fossil collecting was in vogue in the late 18th and early 19th century, at first as a pastime, but gradually transforming into a science as the importance of fossils to geology and biology was understood. The source of most of these fossils were the coastal cliffs around Lyme Regis, part of a geological formation known as the Blue Lias

The Blue Lias is a geological formation in southern, eastern and western England and parts of South Wales, part of the Lias Group. The Blue Lias consists of a sequence of limestone and shale layers, laid down in latest Triassic and early Jurassi ...

. This consists of alternating layers of limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

and shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4) and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especial ...

, laid down as sediment on a shallow seabed early in the Jurassic period (about 210–195 million years ago). It is one of the richest fossil locations in Britain. The cliffs could be dangerously unstable, however, especially in winter when rain caused landslides. It was precisely during the winter months that collectors were drawn to the cliffs because the landslides often exposed new fossils.

Their father, Richard, often took Anning and her brother Joseph on fossil-hunting expeditions to supplement the family's income. They offered their discoveries for sale to tourists on a table outside their home. This was a difficult time for England's poor; the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

, and the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

that followed, caused food shortages. The price of wheat almost tripled between 1792 and 1812, but wages for the working class remained almost unchanged. In Dorset, the rising price of bread caused political unrest, even riots. At one point, Richard Anning was involved in organising a protest against food shortages.

In addition, the family's status as religious dissenters—not followers of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

—attracted disabilities. In the earlier nineteenth century, those who refused to subscribe to the Articles of the Church of England were still not allowed to study at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

or Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

or to take certain positions in the army, and were excluded by law from several professions. Her father had been suffering from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

and injuries he suffered from a fall off a cliff. When he died in November 1810 (aged 44), he left the family with debts and no savings, forcing them to apply for poor relief

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of hel ...

.

The family continued collecting and selling fossils together and set up a table of curiosities near the coach stop at a local inn. Although the stories about Anning tend to focus on her successes, Dennis Dean writes that her mother and brother were astute collectors too, and Anning's parents had sold fossils before the father's death.

Their first well-known find was in 1811 when Mary Anning was 12; her brother Joseph dug up a 4-foot

Their first well-known find was in 1811 when Mary Anning was 12; her brother Joseph dug up a 4-foot ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, altho ...

skull, and a few months later Anning herself found the rest of the skeleton. Henry Hoste Henley of Sandringham House

Sandringham House is a country house in the parish of Sandringham, Norfolk, England. It is one of the royal residences of Charles III, whose grandfather, George VI, and great-grandfather, George V, both died there. The house stands in a estate ...

in Sandringham, Norfolk

Sandringham is a village and civil parish in the north of the English county of Norfolk. The village is situated south of Dersingham, north of King's Lynn and north-west of Norwich.Ordnance Survey (2002). ''OS Explorer Map 250 - Norfolk Coast ...

, who was lord of the manor of Colway, near Lyme Regis, paid the family about £23 for it,Sharpe and McCartney, 1998, p. 15. and in turn he sold it to William Bullock, a well-known collector, who displayed it in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

. There it generated interest, as public awareness of the age of the earth and the variety of prehistoric creatures was growing. It was later sold for £45 and five shillings at auction in May 1819 as a "Crocodile in a Fossil State" to Charles Konig

Charles Dietrich Eberhard Konig or Karl Dietrich Eberhard König, KH (1774 – 6 September 1851) was a German naturalist.

He was born in Brunswick and educated at Göttingen. He came to England at the end of 1800 to organize the collection ...

, of the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

, who had already suggested the name ''Ichthyosaurus'' for it.

Anning's mother Molly initially ran the fossil business after her husband Richard's death, but it is unclear how much actual fossil collecting Molly did herself. As late as 1821, Molly wrote to the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

to request payment for a specimen. Her son Joseph's time was increasingly taken up by his apprenticeship to an upholsterer

Upholstery is the work of providing furniture, especially seats, with padding, springs, webbing, and fabric or leather covers. The word also refers to the materials used to upholster something.

''Upholstery'' comes from the Middle English word ...

, but he remained active in the fossil business until at least 1825. By that time, Mary Anning had assumed the leading role in the family specimen business.

Birch auction

The family's keenest customer was Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas James Birch, later Bosvile, a wealthy collector fromLincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

, who bought several specimens from them. In 1820 Birch became disturbed by the family's poverty. Having made no major discoveries for a year, they were at the point of having to sell their furniture to pay the rent. So he decided to auction on their behalf the fossils he had purchased from them. He wrote to the palaeontologist Gideon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell MRCS FRS (3 February 1790 – 10 November 1852) was a British obstetrician, geologist and palaeontologist. His attempts to reconstruct the structure and life of ''Iguanodon'' began the scientific study of dinosaurs: in ...

on 5 March that year to say that the sale was "for the benefit of the poor woman and her son and daughter at Lyme, who have in truth found almost ''all'' the fine things which have been submitted to scientific investigation ... I may never again possess what I am about to part with, yet in doing it I shall have the satisfaction of knowing that the money will be well applied." The auction was held at Bullocks in London on 15 May 1820, and raised £400 (the equivalent of £ in ). How much of that was given to the Annings is not known, but it seems to have placed the family on a steadier financial footing, and with buyers arriving from Paris and Vienna, the three-day event raised the family's profile within the geological community.

Fossil shop and growing expertise in a risky occupation

Anning continued to support herself selling fossils. Her primary stock in trade consisted of invertebrate fossils such asammonite

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) ...

and belemnite

Belemnitida (or the belemnite) is an extinct order of squid-like cephalopods that existed from the Late Triassic to Late Cretaceous. Unlike squid, belemnites had an internal skeleton that made up the cone. The parts are, from the arms-most ...

shells, which were common in the area and sold for a few shillings. Vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

fossils, such as ichthyosaur skeletons, sold for more, but were much rarer. Collecting them was dangerous winter work. In 1823, an article in ''The Bristol Mirror'' said of her:

The risks of Anning's profession were illustrated when in October 1833 she barely avoided being killed by a landslide that buried her black-and-white terrier, Tray, her constant companion when she went collecting. Anning wrote to a friend, Charlotte Murchison

Charlotte Murchison (''née'' Hugonin; 18 April 1788 – 9 February 1869) was a British geologist born in Hampshire, England. She was married to the nineteenth-century geologist Roderick Impey Murchison.

Several times during her life, the coupl ...

, in November of that year: "Perhaps you will laugh when I say that the death of my old faithful dog has quite upset me, the cliff that fell upon him and killed him in a moment before my eyes, and close to my feet ... it was but a moment between me and the same fate."

As Anning continued to make important finds, her reputation grew. On 10 December 1823, she found the first complete ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias of England. It is distinguishable b ...

'', and in 1828 the first British example of the flying reptiles known as pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to ...

s, called a flying dragon when it was displayed at the British Museum, followed by a ''Squaloraja

''Squaloraja polyspondyla'' is an extinct chimaeriform fish from the Lower Jurassic of Europe. Fossils of ''S. polyspondyla'' have been found in Lower Jurassic-aged marine strata of Lyme Regis, England, and Osteno, Italy.

Individuals of ''S. p ...

'' fish skeleton in 1829. Despite her limited education, she read as much of the scientific literature as she could obtain, and often, laboriously hand-copied papers borrowed from others. Palaeontologist Christopher McGowan examined a copy Anning made of an 1824 paper by William Conybeare on marine reptile fossils and noted that the copy included several pages of her detailed technical illustrations that he was hard-pressed to tell apart from the original. She also dissected modern animals including both fish and cuttlefish

Cuttlefish or cuttles are marine molluscs of the order Sepiida. They belong to the class Cephalopoda which also includes squid, octopuses, and nautiluses. Cuttlefish have a unique internal shell, the cuttlebone, which is used for control of ...

to gain a better understanding of the anatomy of some of the fossils with which she was working. Lady Harriet Silvester, the widow of the former Recorder of the City of London, visited Lyme in 1824 and described Anning in her diary:

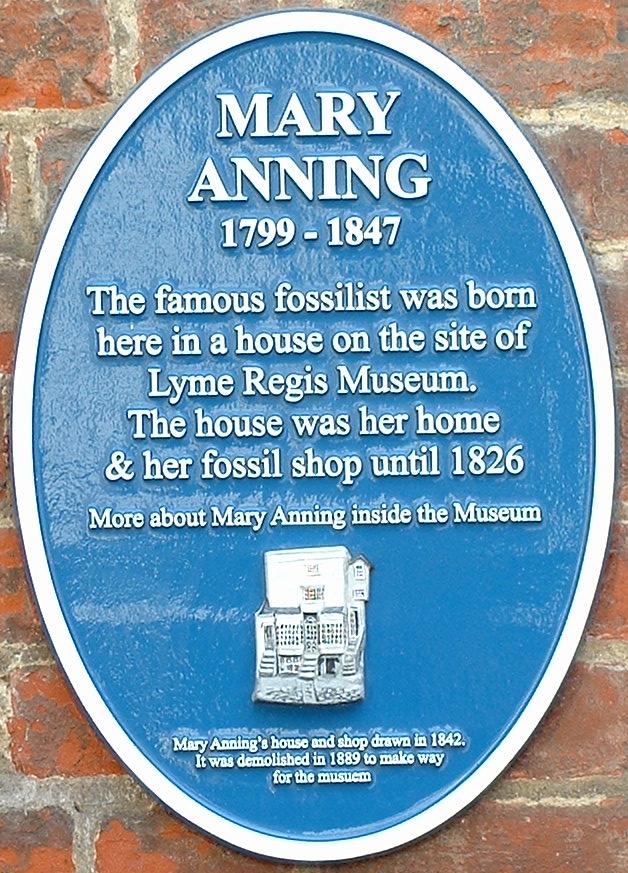

In 1826, at the age of 27, Anning managed to save enough money to purchase a home with a glass store-front window for her shop, ''Anning's Fossil Depot''. The business had become important enough that the move was covered in the local paper, which noted that the shop had a fine ichthyosaur skeleton on display. Many geologists and fossil collectors from Europe and America visited her at Lyme, including the geologist

In 1826, at the age of 27, Anning managed to save enough money to purchase a home with a glass store-front window for her shop, ''Anning's Fossil Depot''. The business had become important enough that the move was covered in the local paper, which noted that the shop had a fine ichthyosaur skeleton on display. Many geologists and fossil collectors from Europe and America visited her at Lyme, including the geologist George William Featherstonhaugh

George William Featherstonhaugh ( /ˈfɪərstənhɔː/ '' FEER-stən-haw''; 9 April 1780, in London – 28 September 1866, in Le Havre) was a British-American geologist and geographer. He was one of the proposers of the Albany and Schenectady Ra ...

, who called Anning a "very clever funny Creature." He purchased fossils from Anning for the newly opened New York Lyceum of Natural History in 1827. King Frederick Augustus II of Saxony

, image = Friedrich August II of Saxony.jpg

, caption = Portrait by Carl Christian Vogel von Vogelstein

, image_size = 220px

, reign = 6 June 1836 – 9 August 1854

, coronation =

, predecessor = Anthony

, ...

visited her shop in 1844 and purchased an ichthyosaur skeleton for his extensive natural history collection. The king's physician and aide, Carl Gustav Carus

Carl Gustav Carus (3 January 1789 – 28 July 1869) was a German physiologist and painter, born in Leipzig, who played various roles during the Romantic era. A friend of the writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, he was a many-sided man: a doctor, ...

, wrote in his journal:

Carus asked Anning to write her name and address in his pocketbook for future reference—she wrote it as "Mary Annins"—and when she handed it back to him she told him: "I am well known throughout the whole of Europe".

* also see As time passed, Anning's confidence in her knowledge grew, and in 1839 she wrote to the ''Magazine of Natural History

The ''Journal of Natural History'' is a scientific journal published by Taylor & Francis focusing on entomology and zoology. The journal was established in 1841 under the name ''Annals and Magazine of Natural History'' (''Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist.'') ...

'' to question the claim made in an article, that a recently discovered fossil of the prehistoric shark ''Hybodus

''Hybodus'' (from el, ύβος , 'crooked' and el, ὀδούς 'tooth') is an extinct genus of hybodont, a group of shark-like elasmobranchs that lived from the Late Devonian to the end of the Cretaceous. Species closely related to the type sp ...

'' represented a new genus, as an error since she had discovered the existence of fossil sharks with both straight and hooked teeth many years ago. The extract from the letter that the magazine printed was the only writing of Anning's published in the scientific literature during her lifetime. Some personal letters written by Anning, such as her correspondence with Frances Augusta Bell, were published while she was alive, however.

Interactions with the scientific community

As a woman, Anning was treated as an outsider to the scientific community. At the time in Britain, women were not allowed to vote, hold public office, or attend university. The newly formed, but increasingly influentialGeological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

did not allow women to become members, or even to attend meetings as guests. The only occupations generally open to working-class women were farm labour, domestic service, and work in the newly opened factories.

Although Anning knew more about fossils and geology than many of the wealthy fossilists to whom she sold, it was always the gentlemen geologists who published the scientific descriptions of the specimens she found, often neglecting to mention Anning's name. She became resentful of this. Anna Pinney, a young woman who sometimes accompanied Anning while she collected, wrote: "She says the world has used her ill ... these men of learning have sucked her brains, and made a great deal of publishing works, of which she furnished the contents, while she derived none of the advantages." Anning herself wrote in a letter: "The world has used me so unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone". Torrens writes that these slights to Anning were part of a larger pattern of ignoring the contributions of working-class people in early 19th-century scientific literature. Often a fossil would be found by a quarryman, construction worker, or road worker who would sell it to a wealthy collector, and it was the latter who was credited if the find was of scientific interest.

Along with purchasing specimens, many geologists visited Anning to collect fossils or discuss anatomy and classification. Henry De la Beche

Sir Henry Thomas De la Beche KCB, FRS (10 February 179613 April 1855) was an English geologist and palaeontologist, the first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, who helped pioneer early geological survey methods. He was the ...

and Anning became friends as teenagers following his move to Lyme, and he, Anning, and sometimes her brother Joseph, went fossil-hunting together. De la Beche and Anning kept in touch as he became one of Britain's leading geologists. William Buckland

William Buckland Doctor of Divinity, DD, Royal Society, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full ...

, who lectured on geology at the University of Oxford, often visited Lyme on his Christmas vacations and was frequently seen hunting for fossils with Anning. It was to him Anning made what would prove to be the scientifically important suggestion (in a letter auctioned for over £100,000 in 2020 ) that the strange conical objects known as bezoar stones were really the fossilised faeces of ichthyosaurs or plesiosaurs. Buckland would name the objects coprolites

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name is de ...

. In 1839 Buckland, Conybeare, and Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

visited Lyme together so that Anning could lead them all on a fossil-collecting excursion.

Anning also assisted Thomas Hawkins with his efforts to collect ichthyosaur fossils at Lyme in the 1830s. She was aware of his penchant to "enhance" the fossils he collected. Anning wrote: "he is such an enthusiast that he makes things as he imagines they ought to be; and not as they are really found...". A few years later there was a public scandal when it was discovered that Hawkins had inserted fake bones to make some ichthyosaur skeletons seem more complete, and later sold them to the government for the British Museum's collection without the appraisers knowing about the additions.

The Swiss palaeontologist Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he rec ...

visited Lyme Regis in 1834 and worked with Anning to obtain and study fish fossils found in the region. He was so impressed by Anning and her friend Elizabeth Philpot

Elizabeth Philpot (1780–1857) was an early 19th-century British fossil collector, amateur palaeontologist and artist who collected fossils from the cliffs around Lyme Regis in Dorset on the southern coast of England. She is best known today fo ...

that he wrote in his journal: "Miss Philpot and Mary Anning have been able to show me with utter certainty which are the ichthyodorulite's dorsal fins of sharks that correspond to different types." He thanked both of them for their help in his book, ''Studies of Fossil Fish''.

Another leading British geologist, Roderick Murchison

Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, 1st Baronet, (19 February 1792 – 22 October 1871) was a Scotland, Scottish geologist who served as director-general of the British Geological Survey from 1855 until his death in 1871. He is noted for investigat ...

, did some of his first fieldwork in southwest England, including Lyme, accompanied by his wife, Charlotte

Charlotte ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Located in the Piedmont region, it is the county seat of Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 census, making Charlotte the 16th-most populo ...

. Murchison wrote that they decided Charlotte should stay behind in Lyme for a few weeks to "become a good practical fossilist, by working with the celebrated Mary Anning of that place...". Charlotte and Anning became lifelong friends and correspondents. Charlotte, who travelled widely and met many prominent geologists through her work with her husband, helped Anning build her network of customers throughout Europe, and she stayed with the Murchisons when she visited London in 1829. Anning's correspondents included Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

, who wrote to ask her opinion on how the sea was affecting the coastal cliffs around Lyme, as well as Adam Sedgwick—one of her earliest customers—who taught geology at the University of Cambridge and who numbered Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

among his students. Gideon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell MRCS FRS (3 February 1790 – 10 November 1852) was a British obstetrician, geologist and palaeontologist. His attempts to reconstruct the structure and life of ''Iguanodon'' began the scientific study of dinosaurs: in ...

, discoverer of the dinosaur Iguanodon

''Iguanodon'' ( ; meaning 'iguana-tooth'), named in 1825, is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur. While many species have been classified in the genus ''Iguanodon'', dating from the late Jurassic Period to the early Cretaceous Period of Asia, Eu ...

, also visited Anning at her shop.

Financial difficulties and change in church affiliation

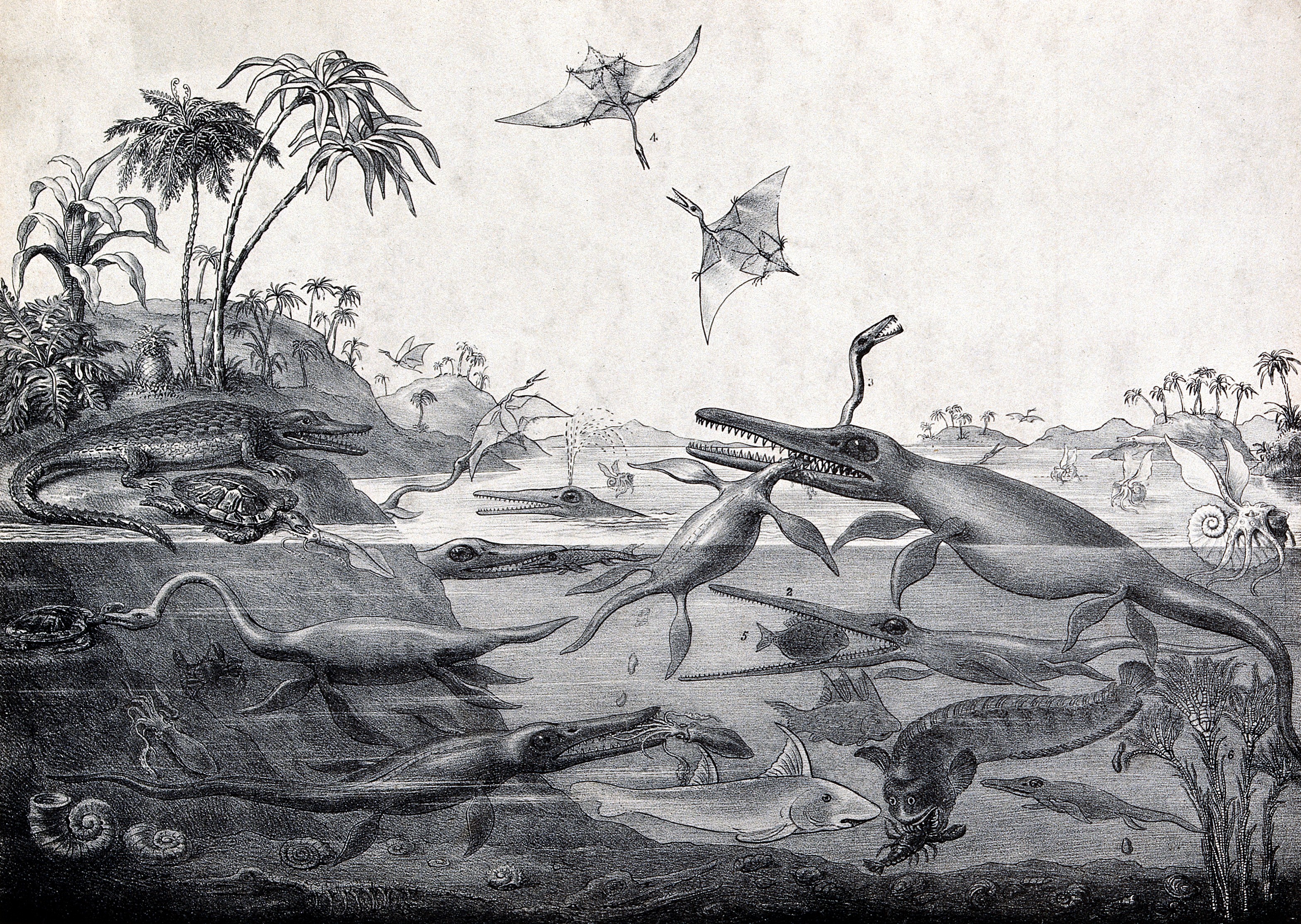

By 1830, because of difficult economic conditions in Britain that reduced the demand for fossils, coupled with long gaps between major finds, Anning was having financial problems again. Her friend, the geologist Henry De la Beche assisted her by commissioning Georg Scharf to make a lithographic print based on De la Beche's watercolour painting, ''

By 1830, because of difficult economic conditions in Britain that reduced the demand for fossils, coupled with long gaps between major finds, Anning was having financial problems again. Her friend, the geologist Henry De la Beche assisted her by commissioning Georg Scharf to make a lithographic print based on De la Beche's watercolour painting, ''Duria Antiquior

''Duria Antiquior, a more ancient Dorset'', was the first pictorial representation of a scene of prehistoric life based on evidence from fossil reconstructions, a genre now known as paleoart. The first version was a watercolour painted in 1830 b ...

'', portraying life in prehistoric Dorset that was based largely on fossils Anning had found. De la Beche sold copies of the print to his fellow geologists and other wealthy friends and donated the proceeds to Anning. It became the first such scene from what later became known as deep time

Deep time is a term introduced and applied by John McPhee to the concept of geologic time in his book ''Basin and Range'' (1981), parts of which originally appeared in the ''New Yorker'' magazine.

The philosophical concept of geological time w ...

to be widely circulated. In December 1830, Anning finally made another major find, a skeleton of a new type of plesiosaur, which sold for £200.

It was around this time that Anning switched from attending the local Congregational church, where she had been baptised and in which she and her family had always been active members, to the Anglican church. The change was prompted in part by a decline in Congregational attendance that began in 1828 when its popular pastor, John Gleed, a fellow fossil collector, left for the United States to campaign against slavery. He was replaced by the less likeable Ebenezer Smith. The greater social respectability of the established church, in which some of Anning's gentleman geologist customers such as Buckland, Conybeare, and Sedgwick were ordained clergy, was also a factor. Anning, who was devoutly religious, actively supported her new church as she had her old.

Anning suffered another serious financial setback in 1835 when she lost most of her life savings, about £300, in a bad investment. Sources differ somewhat on what exactly went wrong. Deborah Cadbury says that she invested with a conman who swindled her and disappeared with the money, but Shelley Emling writes that it is not clear whether the man ran off with the money or whether he died suddenly leaving Anning with no way to recover the investment. Concerned about Anning's financial situation, her old friend William Buckland persuaded the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chie ...

and the British government to award her an annuity

In investment, an annuity is a series of payments made at equal intervals.Kellison, Stephen G. (1970). ''The Theory of Interest''. Homewood, Illinois: Richard D. Irwin, Inc. p. 45 Examples of annuities are regular deposits to a savings account, ...

, known as a civil list pension

Pensions in the United Kingdom, whereby United Kingdom tax payers have some of their wages deducted to save for retirement, can be categorised into three major divisions - state, occupational and personal pensions.

The state pension is based on ...

, in return for her many contributions to the science of geology. The £25 annual pension gave Anning some financial security.

Illness and death

Anning died from

Anning died from breast cancer

Breast cancer is cancer that develops from breast tissue. Signs of breast cancer may include a lump in the breast, a change in breast shape, dimpling of the skin, milk rejection, fluid coming from the nipple, a newly inverted nipple, or a re ...

at the age of 47 on 9 March 1847. Her fossil work had tailed off during the last few years of her life because of her illness, and as some townspeople misinterpreted the effects of the increasing doses of laudanum

Laudanum is a tincture of opium containing approximately 10% powdered opium by weight (the equivalent of 1% morphine). Laudanum is prepared by dissolving extracts from the opium poppy (''Papaver somniferum Linnaeus'') in alcohol (ethanol).

Red ...

she was taking for the pain, there had been gossip in Lyme that she had a drinking problem. The regard in which Anning was held by the geological community was shown in 1846 when, upon learning of her cancer diagnosis, the Geological Society raised money from its members to help with her expenses and the council of the newly created Dorset County Museum made Anning an honorary member. She was buried on 15 March in the churchyard of St Michael's, the local parish church. Members of the Geological Society contributed to a stained-glass window in Anning's memory, unveiled in 1850. It depicts the six corporal ''acts of mercy

Works of mercy (sometimes known as acts of mercy) are practices considered meritorious in Christian ethics.

The practice is popular in the Catholic Church as an act of both penance and charity. In addition, the Methodist church teaches that t ...

''—feeding the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, clothing the naked, sheltering the homeless, visiting prisoners and the sick, and the inscription reads: "This window is sacred to the memory of Mary Anning of this parish, who died 9 March AD 1847 and is erected by the vicar and some members of the Geological Society of London in commemoration of her usefulness in furthering the science of geology, as also of her benevolence of heart and integrity of life."

After Anning's death, Henry De la Beche, president of the Geological Society, wrote a eulogy that he read to a meeting of the society and published in its quarterly transactions, the first such eulogy given for a woman. These were honours normally only accorded to fellows of the society, which did not admit women until 1904. The eulogy began:

After Anning's death, Henry De la Beche, president of the Geological Society, wrote a eulogy that he read to a meeting of the society and published in its quarterly transactions, the first such eulogy given for a woman. These were honours normally only accorded to fellows of the society, which did not admit women until 1904. The eulogy began:

I cannot close this notice of our losses by death without adverting to that of one, who though not placed among even the easier classes of society, but one who had to earn her daily bread by her labour, yet contributed by her talents and untiring researches in no small degree to our knowledge of the great Enalio-Saurians, and other forms of organic life entombed in the vicinity of Lyme Regis ...Henry Stuart Fagan wrote an article about Anning's life in February 1865 in Charles Dickens' literary magazine '' All the Year Round'' (though the article was largely plagiarised and was long mistakenly attributed to Dickens) that emphasised the difficulties Anning had overcome, especially the scepticism of her fellow townspeople. He ended the article with: "The carpenter's daughter has won a name for herself, and has deserved to win it."

Major discoveries

Ichthyosaurs

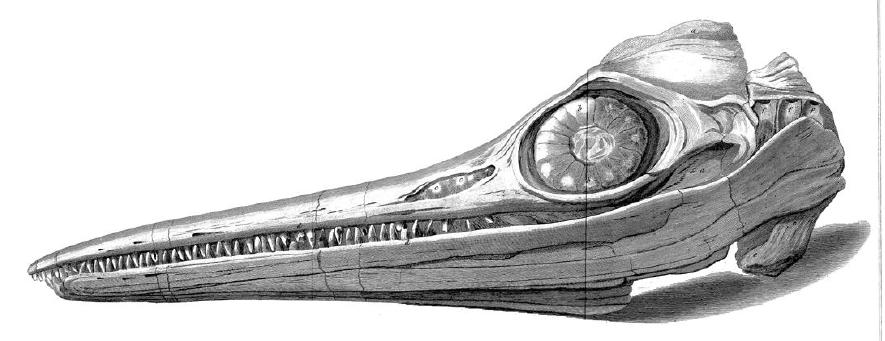

Anning's first famous discovery was made shortly after her father's death when she was still a child of about 12. In 1811 (some sources say 1810 or 1809) her brother Joseph found a skull, but failed to locate the rest of the animal. After Joseph told Anning to look between the cliffs at Lyme Regis and Charmouth, she found the skeleton— long in all—a few months later. The family hired workmen to dig it out in November that year, an event covered by the local press on 9 November, who identified the fossil as a crocodile.

Other

Anning's first famous discovery was made shortly after her father's death when she was still a child of about 12. In 1811 (some sources say 1810 or 1809) her brother Joseph found a skull, but failed to locate the rest of the animal. After Joseph told Anning to look between the cliffs at Lyme Regis and Charmouth, she found the skeleton— long in all—a few months later. The family hired workmen to dig it out in November that year, an event covered by the local press on 9 November, who identified the fossil as a crocodile.

Other ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, altho ...

remains had been discovered in years past at Lyme and elsewhere, but the specimen found by the Annings was the first to come to the attention of scientific circles in London. It was purchased by the lord of a local manor, who passed it to William Bullock for public display in London where it created a sensation. At a time when most people in Britain still believed in a literal interpretation of Genesis

Genesis may refer to:

Bible

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of mankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Book of ...

, that the Earth was only a few thousand years old and that species did not evolve or become extinct,"Fossils and Extinction"The Academy of Natural Sciences. Retrieved 23 September 2010. the find raised questions in scientific and religious circles about what the new science of geology was revealing about ancient life and the history of the Earth. Its notoriety increased when Sir Everard Home wrote a series of six papers, starting in 1814, describing it for the Royal Society. The papers never mentioned who had collected the fossil, and in the first one he even mistakenly credited the painstaking cleaning and preparation of the fossil performed by Anning to the staff at Bullock's museum. Perplexed by the creature, Home kept changing his mind about its classification, first thinking it was a kind of fish, then thinking it might have some kind of affinity with the duck-billed platypus (only recently known to science); finally in 1819 he reasoned it might be a kind of intermediate form between salamanders and lizards, which led him to propose naming it Proteo-Saurus. By then Charles Konig, an assistant curator of the British Museum, had already suggested the name ''Ichthyosaurus'' (fish lizard) for the specimen and that name stuck. Konig purchased the skeleton for the museum in 1819. The skull of the specimen is still in the possession of the

Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

in London (to which the fossil collections of the British Museum were transferred later in the century), but at some point, it became separated from the rest of the skeleton, the location of which is not known.

Anning found several other ichthyosaur fossils between 1815 and 1819, including almost complete skeletons of varying sizes. In 1821, William Conybeare and Henry De la Beche, both members of the Geological Society of London, collaborated on a paper that analysed in detail the specimens found by Anning and others. They concluded that ichthyosaurs were a previously unknown type of marine reptile, and based on differences in tooth structure, they concluded that there had been at least three species. Also in 1821, Anning found the skeleton from which the species ''Ichthyosaurus platydon'' (now ''Temnodontosaurus platyodon

''Temnodontosaurus'' (Greek for "cutting-tooth lizard"temno, meaning "to cut", odont meaning "tooth" and sauros meaning "lizard") is an extinct genus of ichthyosaur from the Early Jurassic period. They lived between 200 and 175 million years ag ...

'') would be named. In the 1980s it was determined that the first ichthyosaur specimen found by Joseph and Mary Anning was also a member of ''Temnodontosaurus platyodon''.

In 2022, two plaster casts of the first complete ichthyosaur skeleton fossil found by Anning that was destroyed in the bombing of London during the Second World War, were discovered in separate collections. One is at the Peabody Museum of Natural History

The Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University is among the oldest, largest, and most prolific university natural history museums in the world. It was founded by the philanthropist George Peabody in 1866 at the behest of his nephew Oth ...

at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

in the USA and the other at the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

in Berlin, Germany. The casts may be secondary, being made from a direct cast of the fossil, but are determined to be of good condition, "historically important", and likely taken from the specimen put for sale at auction by Anning in 1820.

''Plesiosaurus''

In the same 1821 paper he co-authored with Henry De la Beche on ichthyosaur anatomy, William Conybeare named and described the genus ''

In the same 1821 paper he co-authored with Henry De la Beche on ichthyosaur anatomy, William Conybeare named and described the genus ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias of England. It is distinguishable b ...

'' (near lizard), called so because he thought it more like modern reptiles than the ichthyosaur had been. The description was based on a number of fossils, the most complete of them specimen OUMNH J.50146, a paddle and vertebral column that had been obtained by Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas James Birch. Christopher McGowan has hypothesised that this specimen had originally been much more complete and had been collected by Anning, during the winter of 1820/1821. If so, it would have been Anning's next major discovery, providing essential information about the newly recognised type of marine reptile. No records by Anning of the find are known. The paper thanked Birch for giving Conybeare access to it, but does not mention who discovered and prepared it.

In 1823, Anning discovered a second, much more complete plesiosaur skeleton, specimen BMNH 22656. When Conybeare presented his analysis of plesiosaur anatomy to a meeting of the Geological Society in 1824, he again failed to mention Anning by name, even though she had possibly collected both skeletons and had made the sketch of the second skeleton he used in his presentation. Conybeare's presentation was made at the same meeting at which William Buckland described the dinosaur ''

In 1823, Anning discovered a second, much more complete plesiosaur skeleton, specimen BMNH 22656. When Conybeare presented his analysis of plesiosaur anatomy to a meeting of the Geological Society in 1824, he again failed to mention Anning by name, even though she had possibly collected both skeletons and had made the sketch of the second skeleton he used in his presentation. Conybeare's presentation was made at the same meeting at which William Buckland described the dinosaur ''Megalosaurus

''Megalosaurus'' (meaning "great lizard", from Greek , ', meaning 'big', 'tall' or 'great' and , ', meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic period (Bathonian stage, 166 million years ...

'' and the combination created a sensation in scientific circles. The second fossil was named and described as ''Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus'' and is the type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wiktionary:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to a ...

(holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of several ...

) of this species, which itself is the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen ...

of the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

.

Conybeare's presentation followed the resolution of a controversy over the legitimacy of one of the fossils. The fact that the plesiosaur's long neck had an unprecedented 35 vertebrae raised the suspicions of the eminent French anatomist Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier ...

when he reviewed Anning's drawings of the second skeleton, and he wrote to Conybeare suggesting the possibility that the find was a fake produced by combining fossil bones from different kinds of animals. Fraud was far from unknown among early 19th-century fossil collectors, and if the controversy had not been resolved promptly, the accusation could have seriously damaged Anning's ability to sell fossils to other geologists. Cuvier's accusation had resulted in a special meeting of the Geological Society earlier in 1824, which, after some debate, had concluded the skeleton was legitimate. Cuvier later admitted he had acted in haste and was mistaken.

Anning discovered yet another important and nearly complete plesiosaur skeleton in 1830. It was named ''Plesiosaurus macrocephalus'' by William Buckland

William Buckland Doctor of Divinity, DD, Royal Society, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full ...

and was described in an 1840 paper by Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

. Once again Owen mentioned the wealthy gentleman who had purchased the fossil and made it available for examination, but not the woman who had discovered and prepared it.

Fossil fish and pterosaur

Anning found what a contemporary newspaper article called an unrivalled specimen of ''

Anning found what a contemporary newspaper article called an unrivalled specimen of ''Dapedium politum

''Dapedium'' (from el, δαπέδων , 'pavement') is an extinct genus of primitive neopterygian ray-finned fish. The first-described finding was an example of ''D. politum'', found in the Lower Lias of Lyme Regis, on the Jurassic Coast of E ...

''. This was a ray-finned fish, which would be described in 1828. In December of that same year she made an important find consisting of the partial skeleton of a pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to ...

. In 1829 William Buckland described it as ''Pterodactylus macronyx'' (later renamed '' Dimorphodon macronyx'' by Richard Owen), and unlike many other such occasions, Buckland credited Anning with the discovery in his paper. It was the first pterosaur skeleton found outside Germany, and it created a public sensation when displayed at the British Museum. Recent research has found that these creatures were not inclined to fly continuously in their search for fish.

In December 1829 she found a fossil fish, ''Squaloraja

''Squaloraja polyspondyla'' is an extinct chimaeriform fish from the Lower Jurassic of Europe. Fossils of ''S. polyspondyla'' have been found in Lower Jurassic-aged marine strata of Lyme Regis, England, and Osteno, Italy.

Individuals of ''S. p ...

'', which attracted attention because it had characteristics intermediate between sharks and rays

Ray may refer to:

Fish

* Ray (fish), any cartilaginous fish of the superorder Batoidea

* Ray (fish fin anatomy), a bony or horny spine on a fin

Science and mathematics

* Ray (geometry), half of a line proceeding from an initial point

* Ray (gra ...

.

Invertebrates and trace fossils

Vertebrate fossil finds, especially ofmarine reptile

Marine reptiles are reptiles which have become secondarily adapted for an aquatic or semiaquatic life in a marine environment.

The earliest marine reptile mesosaurus (not to be confused with mosasaurus), arose in the Permian period during the ...

s, made Anning's reputation, but she made numerous other contributions to early palaeontology. In 1826 Anning discovered what appeared to be a chamber containing dried ink inside a belemnite

Belemnitida (or the belemnite) is an extinct order of squid-like cephalopods that existed from the Late Triassic to Late Cretaceous. Unlike squid, belemnites had an internal skeleton that made up the cone. The parts are, from the arms-most ...

fossil. She showed it to her friend Elizabeth Philpot who was able to revivify the ink and use it to illustrate some of her own ichthyosaur fossils. Soon other local artists were doing the same, as more such fossilised ink chambers were discovered. Anning noted how closely the fossilised chambers resembled the ink sacs of modern squid

True squid are molluscs with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight arms, and two tentacles in the superorder Decapodiformes, though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also called squid despite not strictly fitting t ...

and cuttlefish

Cuttlefish or cuttles are marine molluscs of the order Sepiida. They belong to the class Cephalopoda which also includes squid, octopuses, and nautiluses. Cuttlefish have a unique internal shell, the cuttlebone, which is used for control of ...

, which she had dissected to understand the anatomy of fossil cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan class Cephalopoda (Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head ...

s, and this led William Buckland

William Buckland Doctor of Divinity, DD, Royal Society, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full ...

to publish the conclusion that Jurassic belemnites had used ink for defence just as many modern cephalopods do. It was also Anning who noticed that the oddly shaped fossils then known as "bezoar stones" were sometimes found in the abdominal region of ichthyosaur skeletons. She noted that if such stones were broken open they often contained fossilised fish bones and scales, and sometimes bones from small ichthyosaurs. Anning suspected the stones were fossilised faeces and suggested so to Buckland in 1824. After further investigation and comparison with similar fossils found in other places, Buckland published that conclusion in 1829 and named them coprolites

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name is de ...

. In contrast to the finding of the plesiosaur skeletons a few years earlier, for which she was not credited, when Buckland presented his findings on coprolites to the Geological Society, he mentioned Anning by name and praised her skill and industry in helping to solve the mystery.

Recognition and legacy

Anning's discoveries became key pieces of evidence for

Anning's discoveries became key pieces of evidence for extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

. Georges Cuvier had argued for the reality of extinction in the late 1790s based on his analysis of fossils of mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

s such as mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus'', one of the many genera that make up the order of trunked mammals called proboscideans. The various species of mammoth were commonly equipped with long, curved tusks and, ...

s. Nevertheless, until the early 1820s it was still believed by many scientifically literate people that just as new species did not appear, so existing ones did not become extinct—in part because they felt that extinction would imply that God's creation had been imperfect; any oddities found were explained away as belonging to animals still living somewhere in an unexplored region of the Earth. The bizarre nature of the fossils found by Anning, — some, such as the plesiosaur