Major explorations after the Age of Discovery on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Major explorations of

British explorer

British explorer

Between 1799 and 1804, Baron

Between 1799 and 1804, Baron

The ''Northwest Passage'' is a sea route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through the

The ''Northwest Passage'' is a sea route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through the

While the South Pole lies on a continental

While the South Pole lies on a continental

Early Western theories believed that in the far south of the globe existed a vast continent, known as

Early Western theories believed that in the far south of the globe existed a vast continent, known as

After the

After the ''Antarctica'', p. 24

Paul Simpson-Housley, 1992

The first humans to reach the South Pole were

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

continued after the Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafarin ...

. By the early seventeenth century, vessels were sufficiently well built and their navigators competent enough to travel to virtually anywhere on the planet by sea. In the 17th century, Dutch explorers such as Willem Jansz

Willem Janszoon (; ), sometimes abbreviated to Willem Jansz., was a Dutch navigator and colonial governor. Janszoon served in the Dutch East Indies in the periods 16031611 and 16121616, including as governor of Fort Henricus on the island of So ...

and Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first known European explorer to reach New Z ...

explored the coasts of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

. Spanish expeditions from Peru explored the South Pacific and discovered archipelagos such as Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, République de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of no ...

and the Pitcairn Islands

The Pitcairn Islands (; Pitkern: '), officially the Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands, is a group of four volcanic islands in the southern Pacific Ocean that form the sole British Overseas Territory in the Pacific Ocean. The four isl ...

. Luis Vaez de Torres chartered the coasts of New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

and the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capita ...

, and discovered the strait

A strait is an oceanic landform connecting two seas or two other large areas of water. The surface water generally flows at the same elevation on both sides and through the strait in either direction. Most commonly, it is a narrow ocean channe ...

that bears his name. European naval exploration mapped the western and northern coasts of Australia, but the east coast had to wait for over a century. Eighteenth-century British explorer James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

mapped much of Polynesia

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of ...

and traveled as far north as Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

and as far south as the Antarctic Circle

The Antarctic Circle is the most southerly of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of Earth. The region south of this circle is known as the Antarctic, and the zone immediately to the north is called the Southern Temperate Zone. S ...

. In the later 18th century, the Pacific became a focus of renewed interest, with Spanish expeditions, followed by Northern European ones, reaching the coasts of northern British Columbia and Alaska.

Voyages into the continents took longer. The centers of the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

had been reached by the mid-16th century, although there were unexplored areas until the 18th and 19th centuries. Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

's and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

's deep interiors were not explored by Europeans until the mid- to late 19th and early 20th centuries, due to a lack of trade potential, and to serious problems with contagious tropical disease

Tropical diseases are Infectious disease, diseases that are prevalent in or unique to tropics, tropical and subtropics, subtropical regions. The diseases are less prevalent in temperate climates, due in part to the occurrence of a cold season, whic ...

s in sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

's case. Finally, Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest contine ...

's interior was explored, with the North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

s reached in the 20th century.

History

James Cook's Pacific Ocean exploration (1768–1779)

British explorer

British explorer James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

, who had been the first to map the North Atlantic island of Newfoundland

Newfoundland (, ; french: link=no, Terre-Neuve, ; ) is a large island off the east coast of the North American mainland and the most populous part of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It has 29 percent of the province's land ...

, spent a dozen years in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. He made great contributions to European knowledge of the area, and his more accurate navigational charting of large areas of the ocean was a major achievement.

Cook made three voyages to the Pacific, including the first European contact with the eastern coastline of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

and the Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kur ...

(although oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985 ...

seems to point towards a far earlier Spanish expedition having achieved the latter), as well as the first recorded circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical object, astronomical body (e.g. a planet or natural satellite, moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circ ...

of New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

.

Cook was the first European to have extensive contact with various people of the Pacific. He correctly concluded there was a relationship among all the people in the Pacific, despite their being separated by thousands of miles of ocean (see Malayo-Polynesian languages

The Malayo-Polynesian languages are a subgroup of the Austronesian languages, with approximately 385.5 million speakers. The Malayo-Polynesian languages are spoken by the Austronesian peoples outside of Taiwan, in the island nations of Southeast ...

). In New Zealand the coming of Cook is often used to signify the onset of colonization.per Collingridge (2002)per Horwitz (2003) He also theorised that Polynesians originated from Asia, which was later proved to be correct by scientist Bryan Sykes

Bryan Clifford Sykes (9 September 1947 – 10 December 2020) was a British geneticist and science writer who was a Fellow of Wolfson College and Emeritus Professor of human genetics at the University of Oxford.Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James ...

and Swedish Daniel Solander

Daniel Carlsson Solander or Daniel Charles Solander (19 February 1733 – 13 May 1782) was a Swedish naturalist and an apostle of Carl Linnaeus.

Solander was the first university-educated scientist to set foot on Australian soil.

Biography

...

, between them collecting over 3,000 plant species. Banks became one of the strongest promoters of the settlement of Australia by the British, based on his own personal observations. Cook was also accompanied by artists. Sydney Parkinson

Sydney Parkinson (c. 1745 – 26 January 1771) was a Scottish botanical illustrator and natural history artist. He was the first European artist to visit Australia, New Zealand and Tahiti. Parkinson was the first Quaker to visit New Zealand.

...

completed 264 drawings before his death near the end of the first voyage; these were of immense scientific value to British botanists. Cook's second expedition included the artist William Hodges

William Hodges RA (28 October 1744 – 6 March 1797) was an English painter. He was a member of James Cook's second voyage to the Pacific Ocean and is best known for the sketches and paintings of locations he visited on that voyage, inclu ...

, who produced notable landscape painting

Landscape painting, also known as landscape art, is the depiction of natural scenery such as mountains, valleys, trees, rivers, and forests, especially where the main subject is a wide view—with its elements arranged into a coherent compos ...

s of Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

, Easter Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearl ...

, and other locations.

Mapping and measuring

To create accurate maps,latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pol ...

and longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east–west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek letter l ...

need to be known. Navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's primar ...

s had been able to work out latitude accurately for centuries by measuring the angle of the sun or a star above the horizon with an instrument such as a backstaff

The backstaff is a navigational instrument that was used to measure the altitude of a celestial body, in particular the Sun or Moon. When observing the Sun, users kept the Sun to their back (hence the name) and observed the shadow cast by the u ...

or quadrant. Longitude was more difficult to measure accurately because it requires precise knowledge of the time difference between points on the surface of the earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surface ...

. Earth turns a full 360 degrees relative to the sun each day. Thus longitude corresponds to time: 15 degrees every hour, or 1 degree every 4 minutes.

Cook gathered accurate longitude measurements during his first voyage with the help of astronomer Charles Green and by using the newly published Nautical Almanac

A nautical almanac is a publication describing the positions of a selection of celestial bodies for the purpose of enabling navigators to use celestial navigation to determine the position of their ship while at sea. The Almanac specifies for ea ...

tables, via the lunar distance method — measuring the angular distance

Angular distance \theta (also known as angular separation, apparent distance, or apparent separation) is the angle between the two sightlines, or between two point objects as viewed from an observer.

Angular distance appears in mathematics (in pa ...

from the moon to either the sun during daytime or one of eight bright stars during night-time to determine the time at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich

The Royal Observatory, Greenwich (ROG; known as the Old Royal Observatory from 1957 to 1998, when the working Royal Greenwich Observatory, RGO, temporarily moved south from Greenwich to Herstmonceux) is an observatory situated on a hill in ...

, and comparing that to his local time

Local time is the time observed in a specific locality. There is no canonical definition. Originally it was mean solar time, but since the introduction of time zones it is generally the time as determined by the time zone in effect, with daylight s ...

determined via the altitude of the sun, moon, or stars. On his second voyage Cook used the K1 chronometer

A clock or a timepiece is a device used to measure and indicate time. The clock is one of the oldest human inventions, meeting the need to measure intervals of time shorter than the natural units such as the day, the lunar month and the ...

made by Larcum Kendall

Larcum Kendall (21 September 1719 in Charlbury, Oxfordshire – 22 November 1790 in London) was a British watchmaker.

Early life

Kendall was born on 21 September 1719 in Charlbury. His father was a mercer and linen draper named Moses Ke ...

. It was a copy of the H4 clock made by John Harrison

John Harrison ( – 24 March 1776) was a self-educated English Carpentry, carpenter and clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer, a long-sought-after device for solving the History of longitude, problem of calculating longitude while at s ...

, which proved to be the first to keep accurate time at sea when used on the ship ''Deptford's'' journey to Jamaica, 1761–1762.

Scientific Surveys in Central America and the Pacific

Alexander von Humboldt (1799–1804)

Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, p ...

a German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

naturalist and explorer

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

, traveled extensively in Spanish America

Spanish America refers to the Spanish territories in the Americas during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. The term "Spanish America" was specifically used during the territories' Spanish Empire, imperial era between 15th century, 15th ...

, under the protection of king Charles IV of Spain

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Charles III of Spain

, mother =Maria Amalia of Saxony

, birth_date =11 November 1748

, birth_place =Palace of Portici, Portici, Naples

, death_date =

, death_place = ...

. Humboldt intended to investigate how the forces of nature interact with one another and find out about the unity of nature. His expedition may be regarded as having laid the foundation of the sciences of physical geography

Physical geography (also known as physiography) is one of the three main branches of geography. Physical geography is the branch of natural science which deals with the processes and patterns in the natural environment such as the atmosphere, h ...

and meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did not ...

, exploring and describing for the first time in a manner generally considered to be a modern scientific point of view.

As a consequence of his explorations, von Humboldt described many geographical features and species of life that were hitherto unknown to Europeans and his quantitative work on botanical

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

was foundational to the field of biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, ...

. By his delineation of "isothermal lines", in 1817 he devised the means of comparing the climatic conditions of various countries, and to the detection of the more complicated law governing atmospheric disturbances in higher latitudes; he discovered the decrease in intensity of Earth's magnetic field

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to ...

from the poles to the equator. His attentive study of the volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates are ...

es of the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

, showed that they fell naturally into linear groups, presumably corresponding with vast subterranean fissures, and he demonstrated the igneous

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or ...

origin of rocks. He was one of the first to propose that the lands bordering the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

were once joined (South America and Africa in particular). The details and findings of Humboldt’s journey were published in a set of 30 volumes over 21 years, his ''Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equatorial Regions of the New Continent''. Later, his five-volume work, '' Cosmos: A Sketch for a Physical Description of the Universe'' (1845), attempted to unify the various branches of scientific knowledge.

Darwin and the second voyage of HMS Beagle (1831–1836)

In December 1831 a British expedition departed under captainRobert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy and a scientist. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of during Charles Darwin's famous voyage, FitzRoy's second expedition to Tierra de ...

, on board HMS ''Beagle'', with the main purpose of making a hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey is the science of measurement and description of features which affect maritime navigation, marine construction, dredging, offshore oil exploration/offshore oil drilling and related activities. Strong emphasis is placed ...

of the coasts of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

using calibrated chronometers and astronomical

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, galaxies ...

observations, producing charts for naval war or commerce. The longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east–west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek letter l ...

of Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

was to be found and also a geological survey made of a circular coral atoll

An atoll () is a ring-shaped island, including a coral rim that encircles a lagoon partially or completely. There may be coral islands or cays on the rim. Atolls are located in warm tropical or subtropical oceans and seas where corals can gr ...

in the Pacific ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

.

FitzRoy thought of the advantages of having an expert in geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

on board, and sought a gentleman

A gentleman (Old French: ''gentilz hom'', gentle + man) is any man of good and courteous conduct. Originally, ''gentleman'' was the lowest rank of the landed gentry of England, ranking below an esquire and above a yeoman; by definition, the ra ...

naturalist who could be his companion. The young graduate, Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

, had hoped to see the tropics before becoming a parson

A parson is an ordained Christian person responsible for a small area, typically a parish. The term was formerly often used for some Anglican clergy and, more rarely, for ordained ministers in some other churches. It is no longer a formal term d ...

, and took this opportunity. The ''Beagle'' sailed across the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

then carried out detailed hydrographic surveys, returning via Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, having circumnavigated the Earth. Originally planned to last two years, the expedition lasted almost five. Darwin spent most of this time exploring on land. Early in the voyage he decided that he could write a book about geology, and he showed a gift for theorising. By the end of the expedition he had already made his name as a geologist and fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

collector, and the publication of his journal, known as ''The Voyage of the Beagle

''The Voyage of the Beagle'' is the title most commonly given to the book written by Charles Darwin and published in 1839 as his ''Journal and Remarks'', bringing him considerable fame and respect. This was the third volume of ''The Narrative ...

'', gave him wide renown as a writer. At Punta Alta

Punta Alta is a city in Argentina, about 20 kilometers southeast of Bahía Blanca. It has a population of 57,293. It is the capital ("cabecera") of the Coronel Rosales Partido. It was founded on 2 July 1898.

The city is located near the Atlanti ...

he made a major find of gigantic fossils of extinct mammals, then known from only a very few specimens. He ably collected and made detailed observations of plants and animals, with results that shook his belief that species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

were fixed, and provided the basis for ideas which came to him when back in England, leading to his theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

by natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

.

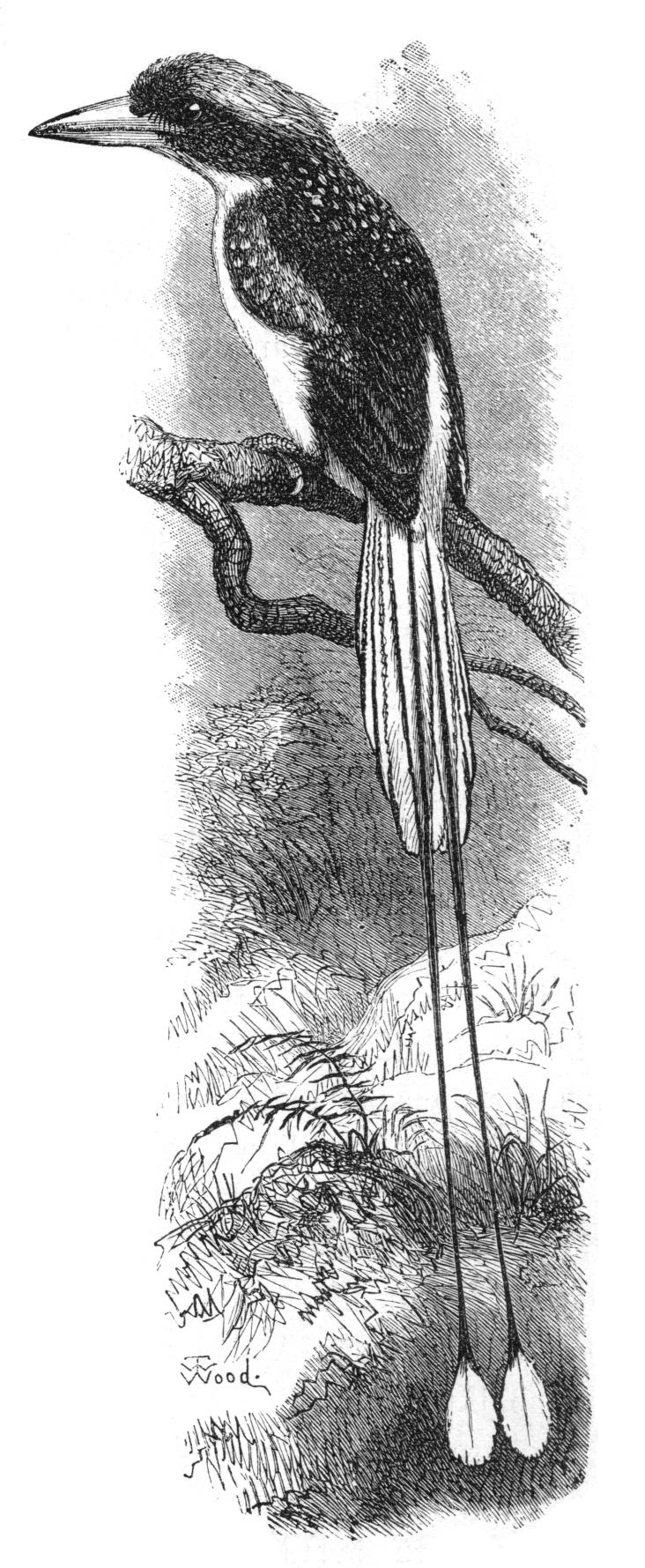

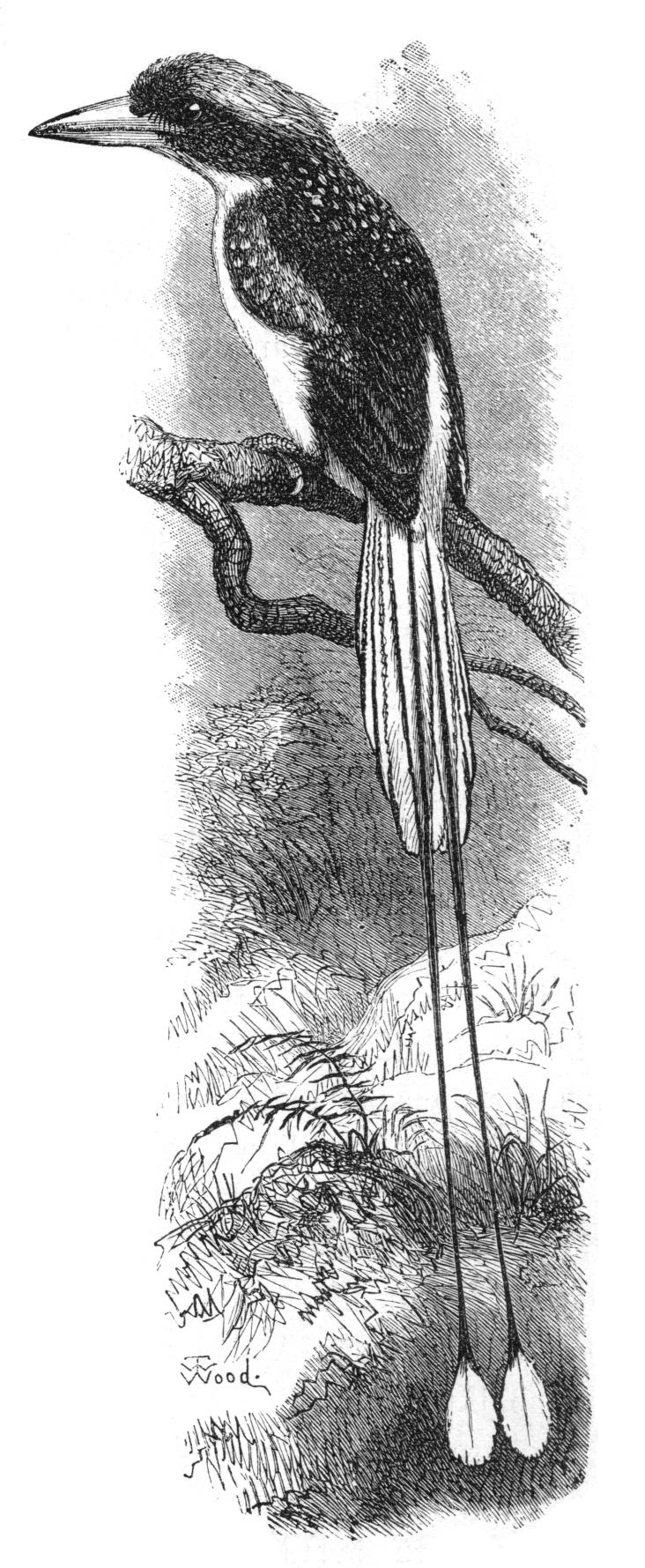

Alfred Russel Wallace Amazon and Malay explorations (1848–1862)

In 1848, inspired by the chronicles of earlier traveling naturalists British naturalistAlfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution through natural se ...

and Henry Bates left for Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

with the intention of collecting insects and other animal specimens in the Amazon rainforest

The Amazon rainforest, Amazon jungle or ; es, Selva amazónica, , or usually ; french: Forêt amazonienne; nl, Amazoneregenwoud. In English, the names are sometimes capitalized further, as Amazon Rainforest, Amazon Forest, or Amazon Jungle. ...

. Wallace charted the Rio Negro for four years, collecting specimens and making notes on peoples, geography, flora, and fauna. In July 1852, while returning to the UK, the ship's cargo caught fire and all the specimens he had collected were lost.Slotten pp. 87-88

From 1854 to 1862, Wallace traveled again through Maritime Southeast Asia

Maritime Southeast Asia comprises the countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor. Maritime Southeast Asia is sometimes also referred to as Island Southeast Asia, Insular Southeast Asia or Oceanic Sout ...

to collect specimens for sale and study nature. He collected more than 125,000 specimens, more than a thousand of them representing species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

new to science. His observations of the marked differences across a narrow strait in the archipelago led to his proposing the zoogeographical boundary now known as the Wallace line

The Wallace Line or Wallace's Line is a faunal boundary line drawn in 1859 by the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace and named by English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley that separates the biogeographical realms of Asia and Wallacea, a tran ...

, that divides Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

into two distinct parts: one with animals closely related to those of Australia, and one in which the species are largely of Asian origin. He became an expert on biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, ...

, creating the basis for the zoogeographic regions still in use today. While he was exploring the archipelago, he refined his thoughts about evolution and had his famous insight on natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

.

His interest resulted in his being one of the first prominent scientists to raise concerns over the environmental impact of human activity, like deforestation and invasive species

An invasive species otherwise known as an alien is an introduced organism that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment. Although most introduced species are neutral or beneficial with respect to other species, invasive species ad ...

. In 1878, he warned about the dangers of deforestation and soil erosion in tropical climates, like the extensive clearing of rainforest

Rainforests are characterized by a closed and continuous tree canopy, moisture-dependent vegetation, the presence of epiphytes and lianas and the absence of wildfire. Rainforest can be classified as tropical rainforest or temperate rainfores ...

for coffee cultivation in Ceylon (Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

) and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. Accounts of his travels were published in ''The Malay Archipelago

''The Malay Archipelago'' is a book by the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace which chronicles his scientific exploration, during the eight-year period 1854 to 1862, of the southern portion of the Malay Archipelago including Malaysia, S ...

'' in 1869, one of the most popular and influential journals of scientific exploration published during the 19th century.

Interior Africa exploration

Africa's deep interiors were not explored by Europeans until the mid to late 19th and early 20th centuries; this being due to a lack of trade potential in this region, and to serious problems with contagioustropical disease

Tropical diseases are Infectious disease, diseases that are prevalent in or unique to tropics, tropical and subtropics, subtropical regions. The diseases are less prevalent in temperate climates, due in part to the occurrence of a cold season, whic ...

s in sub-Saharan Africa's case.

David Livingstone (1849–1855)

In the mid-19th century,Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

missions were carrying on active missionary work

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

on the Guinea coast, in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

and in Zanzibar. Missionaries in many instances became explorers and pioneers. David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, and pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, an explorer in Africa, and one of the most popular British heroes of t ...

, a Scottish missionary, had been engaged since 1840 in work north of the Orange River

The Orange River (from Afrikaans/Dutch: ''Oranjerivier'') is a river in Southern Africa. It is the longest river in South Africa. With a total length of , the Orange River Basin extends from Lesotho into South Africa and Namibia to the north ...

. In 1849, Livingstone crossed the Kalahari Desert

The Kalahari Desert is a large semi-arid sandy savanna in Southern Africa extending for , covering much of Botswana, and parts of Namibia and South Africa.

It is not to be confused with the Angolan, Namibian, and South African Namib coastal de ...

from south to north and reached Lake Ngami

Lake Ngami is an endorheic lake in Botswana north of the Kalahari Desert. It is seasonally filled by the Taughe River, an effluent of the Okavango River system flowing out of the western side of the Okavango Delta. It is one of the fragmented remn ...

. Between 1851 and 1856, he traversed the continent from west to east, discovering the great waterways of the upper Zambezi River

The Zambezi River (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than hal ...

. In November 1855, Livingstone became the first European to see the famous Victoria Falls

Victoria Falls ( Lozi: ''Mosi-oa-Tunya'', "The Smoke That Thunders"; Tonga: ''Shungu Namutitima'', "Boiling Water") is a waterfall on the Zambezi River in southern Africa, which provides habitat for several unique species of plants and animal ...

, named after the Queen of the United Kingdom. From 1858 to 1864, the lower Zambezi, the Shire River

The Shire is the largest river in Malawi. It is the only outlet of Lake Malawi and flows into the Zambezi River in Mozambique. Its length is . The upper Shire River issues from Lake Malawi and runs approximately before it enters shallow Lake Malo ...

and Lake Nyasa

Lake Malawi, also known as Lake Nyasa in Tanzania and Lago Niassa in Mozambique, is an African Great Lake and the southernmost lake in the East African Rift system, located between Malawi, Mozambique and Tanzania.

It is the fifth largest fre ...

were explored by Livingstone. Nyasa had been first reached by the confidential slave of António da Silva Porto

António Francisco Ferreira da Silva Porto (24 August 1817 – 2 April 1890) was a Portuguese trader and explorer in Angola, in the Portuguese West Africa.

Biography

Silva Porto was born to a poor family in Porto in continental Portugal; h ...

, a Portuguese trader established at Bié in Angola, who crossed Africa during 1853–1856 from Benguella to the mouth of the Rovuma. A prime goal for explorers was to locate the source of the River Nile. Expeditions by Burton and Speke (1857–1858) and Speke and Grant (1863) located Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika () is an African Great Lake. It is the second-oldest freshwater lake in the world, the second-largest by volume, and the second-deepest, in all cases after Lake Baikal in Siberia. It is the world's longest freshwater lake. ...

and Lake Victoria

Lake Victoria is one of the African Great Lakes. With a surface area of approximately , Lake Victoria is Africa's largest lake by area, the world's largest tropical lake, and the world's second-largest fresh water lake by surface area after ...

. It was eventually proved to be the latter from which the Nile flowed.

Explorers were also active in other parts of the continent. Southern Morocco, the Sahara and the Sudan were traversed in many directions between 1860 and 1875 by Georg Schweinfurth

Georg August Schweinfurth (29 December 1836 – 19 September 1925) was a Baltic German botanist and ethnologist who explored East Central Africa.

Life and explorations

He was born at Riga, Latvia, then part of the Russian Empire. He was edu ...

and Gustav Nachtigal

Gustav Nachtigal (; born 23 February 1834 – 20 April 1885) was a German military surgeon and explorer of Central and West Africa. He is further known as the German Empire's consul-general for Tunisia and Commissioner for West Africa. His missio ...

. These travellers not only added considerably to geographical knowledge, but obtained invaluable information concerning the people, languages and natural history of the countries in which they sojourned. Among the discoveries of Schweinfurth was one that confirmed Greek legends of the existence beyond Egypt of a "pygmy race". But the first western discoverer of the pygmies of Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, ...

was Paul Du Chaillu

Paul Belloni Du Chaillu (July 31, 1831 (disputed)April 29, 1903) was a French-American traveler, zoologist, and anthropologist. He became famous in the 1860s as the first modern European outsider to confirm the existence of gorillas, and later t ...

, who found them in the Ogowe district of the west coast in 1865, five years before Schweinfurth's first meeting with them. Du Chaillu had previously, through journeys in the Gabon region between 1855 and 1859, made popular in Europe the knowledge of the existence of the gorilla, whose existence was thought to be legendary.

Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author and politician who was famous for his exploration of Central Africa

Cen ...

, who had in 1871 succeeded in finding and rescuing Livingstone (originating the famous line "Dr. Livingstone, I presume"), started again for Zanzibar in 1874. In one of the most memorable of all exploring expeditions in Africa, Stanley circumnavigated Victoria Nyanza and Tanganyika. Striking farther inland to the Lualaba, he followed that river down to the Atlantic Ocean—which he reached in August 1877—and proved it to be the Congo.

Serpa Pinto, Capelo, and Ivens (1877–1886)

PortugueseSerpa Pinto

Alexandre Alberto da Rocha de Serpa Pinto, Viscount of Serpa Pinto (aka Serpa Pinto; 20 April 184628 December 1900) was a Portuguese people, Portuguese explorer of southern Africa and a colonial administrator.

Early life

Serpa Pinto was born at ...

was the fourth explorer to cross Africa from west to east and the first to lay down a reasonably accurate route between Bié (in present-day Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

) and Lealui. In 1877, Serpa Pinto

Alexandre Alberto da Rocha de Serpa Pinto, Viscount of Serpa Pinto (aka Serpa Pinto; 20 April 184628 December 1900) was a Portuguese people, Portuguese explorer of southern Africa and a colonial administrator.

Early life

Serpa Pinto was born at ...

and Portuguese naval captains Capelo

Capelo is a ''freguesia'' ("civil parish") in the municipality of Horta on the island of Faial in the Azorean archipelago. The population in 2011 was 486, in an area of 26.64 km². Capelo may be considered the westernmost settlement of Euras ...

and Ivens explored the southern African interior starting from Benguela

Benguela (; Umbundu: Luombaka) is a city in western Angola, capital of Benguela Province. Benguela is one of Angola's most populous cities with a population of 555,124 in the city and 561,775 in the municipality, at the 2014 census.

History

Por ...

. Capello and Ivens turning northward whilst Serpa Pinto continued eastward. He crossed the Cuando (Kwando) river in June 1878 and in August reached Lealui Lealui or Lialui is the dry season residence on the Barotse Floodplain of the Litunga, king of the Lozi people of western Zambia. It is located about 14 km west of the town of Mongu and about 10 km east of the river's main channel. At th ...

, the Barotse

Lozi people, or Barotse, are a southern African ethnic group who speak Lozi or Silozi, a Sotho–Tswana language. The Lozi people consist of more than 46 different ethnic groups and are primarily situated between Namibia, Angola, Botswana, Zimbab ...

capital on the Zambezi.

From 1884 to 1886, Hermenegildo Capelo

Hermenegildo de Brito Capelo (Palmela, 1841 – Lisbon, 1917) was an officer in the Portuguese Navy and a Portuguese explorer, helping to chart territory between Angola and Mozambique in southern Central Africa that was unknown to Europeans ...

and Roberto Ivens

Roberto Ivens (12 June 1850 in Ponta Delgada – 28 January 1898 in Dafundo, Oeiras Municipality, Portugal, Oeiras) was a Portugal, Portuguese European exploration of Africa, explorer of Africa, geographer, colonial administrator, and an officer o ...

crossed Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the Congo and Tanzania. The physical location is the large part of Africa to the south of the extensive Congo River basin. Southern Africa is home to a number of ...

between Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

and Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

to map the unknown territory of the Portuguese colonies

The Portuguese Empire ( pt, Império Português), also known as the Portuguese Overseas (''Ultramar Português'') or the Portuguese Colonial Empire (''Império Colonial Português''), was composed of the overseas colonies, factories, and the l ...

. The choice of two marine officials for this achievement certainly appealed to the principles of maritime navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, ...

. Between 1884 and 1885, Capelo and Ivens explored Africa interior, first between the coastline and Huila plain and later through the interior of Quelimane

Quelimane () is a seaport in Mozambique. It is the administrative capital of the Zambezia Province and the province's largest city, and stands from the mouth of the Rio dos Bons Sinais (or "River of the Good Signs"). The river was named when V ...

in Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

, continuing their hydrographic studies, updating registers, but also taking notes on the ethnographic and the linguistic characters they encountered. They established thus the so desired land route between the coasts of Angola and Mozambique, exploring vast regions of the interior located between these two territories. Their achievements were recorded in a two volume book titled: ''De Angola à Contra-Costa'' (''From Angola to the Other Coast'').

Exploring the Arctic and Antarctic

Arctic and Antarctic seas were not explored until the 19th century. Once theNorth Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

had been reached in 1909, several expeditions attempted to reach the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

. Many resulted in injury and death. The Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

*Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

*Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including the ...

Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen bega ...

finally reached the Pole in December 1911, following a dramatic race with the Englishman

The English people are an ethnic group and nation native to England, who speak the English language, a West Germanic language, and share a common history and culture. The English identity is of Anglo-Saxon origin, when they were known in ...

Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott, , (6 June 1868 – c. 29 March 1912) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–1904 and the ill-fated ''Terra Nov ...

.

The Northwest Passage

The ''Northwest Passage'' is a sea route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through the

The ''Northwest Passage'' is a sea route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

. Interest kindled in 1564 after Jacques Cartier

Jacques Cartier ( , also , , ; br, Jakez Karter; 31 December 14911 September 1557) was a French-Breton maritime explorer for France. Jacques Cartier was the first European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of th ...

's discovery of the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connectin ...

, Martin Frobisher

Sir Martin Frobisher (; c. 1535 – 22 November 1594) was an English seaman and privateer who made three voyages to the New World looking for the North-west Passage. He probably sighted Resolution Island near Labrador in north-eastern Canada ...

had formed a resolution to undertake the challenge of forging a trade route from England westward to India. In 1576 - 1578, he took three trips to what is now the Canadian Arctic in order to find the passage. Frobisher Bay

Frobisher Bay is an inlet of the Davis Strait in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is located in the southeastern corner of Baffin Island. Its length is about and its width varies from about at its outlet into the Labrador Sea ...

, which he discovered, is named after him. On August 8, 1585, under the employ of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

the English explorer John Davis entered Cumberland Sound

Cumberland Sound (french: Baie Cumberland; Inuit languages, Inuit: ''Kangiqtualuk'') is an Arctic waterway in Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is a western arm of the Labrador Sea located between Baffin Island's Hall Peninsula and the Cumbe ...

, Baffin Island

Baffin Island (formerly Baffin Land), in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, is the largest island in Canada and the fifth-largest island in the world. Its area is , slightly larger than Spain; its population was 13,039 as of the 2021 Canadia ...

. Davis rounded Greenland before dividing his four ships into separate expeditions to search for a passage westward. Though he was unable to pass through the icy Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

waters, he reported to his sponsors that the passage they sought is "a matter nothing doubtfull ," and secured support for two additional expeditions, reaching as far as Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

. Though England's efforts were interrupted in 1587 because of Anglo-Spanish War, Davis's favorable reports on the region and its people would inspire explorers in the coming century.

In the first half of the 19th century, parts of the Northwest Passage were explored separately by a number of different expeditions, including those by John Ross, William Edward Parry

Sir William Edward Parry (19 December 1790 – 8 July 1855) was an Royal Navy officer and explorer best known for his 1819–1820 expedition through the Parry Channel, probably the most successful in the long quest for the Northwest Pass ...

, James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British Royal Navy officer and polar explorer known for his explorations of the Arctic, participating in two expeditions led by his uncle John Ross, and four led by William Edwa ...

; and overland expeditions led by John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. After serving in wars against Napoleonic France and the United States, he led two expeditions into the Canadian Arctic and through ...

, George Back

Admiral Sir George Back (6 November 1796 – 23 June 1878) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer of the Canadian Arctic, naturalist and artist. He was born in Stockport.

Career

As a boy, he went to sea as a volunteer in the frigat ...

, Peter Warren Dease

Peter Warren Dease (January 1, 1788 – January 17, 1863) was a Canadian fur trader and Arctic explorer.

Biography

Early life

Peter Warren Dease was born at Michilimackinac (now Mackinac Island) on January 1, 1788, the fourth son of Dr. ...

, Thomas Simpson

Thomas Simpson Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (20 August 1710 – 14 May 1761) was a British mathematician and inventor known for the :wikt:eponym, eponymous Simpson's rule to approximate definite integrals. The attribution, as often in mathe ...

, and John Rae. Sir Robert McClure

Vice-Admiral Sir Robert John Le Mesurier McClure (28 January 1807 – 17 October 1873) was an Irish explorer of Scots descent who explored the Arctic. In 1854 he traversed the Northwest Passage by boat and sledge, and was the first to ci ...

was credited with the discovery of the Northwest Passage by sea in 1851 when he looked across McClure Strait

The M'Clure Strait (sometimes rendered McClure Strait) is a strait on the edge of the Canadian Northwest Territories. It forms the northwestern end of the Parry Channel which extends east all the way to Baffin Bay and is thus a possible route fo ...

from Banks Island

Banks Island is one of the larger members of the Arctic Archipelago. Situated in the Inuvik Region, and part of the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, of the Northwest Territories, it is separated from Victoria Island to its east by the Prince of ...

and viewed Melville Island. However, the strait was blocked by young ice at this point in the season, and not navigable to ships. The only usable route, linking the entrances of Lancaster Sound

Lancaster Sound () is a body of water in the Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is located between Devon Island and Baffin Island, forming the eastern entrance to the Parry Channel and the Northwest Passage. East of the sound lies Baffin Bay ...

and Dolphin and Union Strait

Dolphin and Union Strait lies in both the Northwest Territories (Inuvik Region) and Nunavut (Kitikmeot Region), Canada, between the mainland and Victoria Island. It is part of the Northwest Passage. It links Amundsen Gulf, lying to the northwest, ...

was first used by John Rae in 1851. Rae used a pragmatic approach of traveling by land on foot and dogsled, and typically employed less than ten people in his exploration parties.

The Northwest Passage was not completely conquered by sea until 1906, when the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen bega ...

, who had sailed just in time to escape creditors seeking to stop the expedition, completed a three-year voyage in the converted 47-ton herring boat ''Gjøa

''Gjøa'' was the first vessel to transit the Northwest Passage. With a crew of six, Roald Amundsen traversed the passage in a three-year journey, finishing in 1906.

History

Construction

The square-sterned sloop of 47 net register ton ...

''. At the end of this trip, he walked into the city of Eagle, Alaska

Eagle ( in Hän Athabascan) is a city on the south bank of the Yukon River near the Canada–US border in the Southeast Fairbanks Census Area, Alaska, United States. It includes the Eagle Historic District, a U.S. National Historic Landmark. The ...

, and sent a telegram announcing his success. His route was not commercially practical; in addition to the time taken, some of the waterways were extremely shallow.

= The North Pole (1909–1952)

= While the South Pole lies on a continental

While the South Pole lies on a continental land mass

A landmass, or land mass, is a large region or area of land. The term is often used to refer to lands surrounded by an ocean or sea, such as a continent or a large island. In the field of geology, a landmass is a defined section of continental ...

, the North Pole is located in the middle of the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

amidst waters that are almost permanently covered with constantly shifting sea ice.

A number of expeditions set out with the intention of reaching the North Pole but did not succeed; that of British naval officer William Edward Parry

Sir William Edward Parry (19 December 1790 – 8 July 1855) was an Royal Navy officer and explorer best known for his 1819–1820 expedition through the Parry Channel, probably the most successful in the long quest for the Northwest Pass ...

, in 1827, the American Polaris expedition in 1871, and Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (; 10 October 186113 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat, and humanitarian. He led the team t ...

in 1895. American Frederick Albert Cook claimed to have reached the North Pole in 1908, but this has not been widely accepted.

The conquest of the North Pole was for many years credited to American Navy engineer Robert Peary

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (; May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer and officer in the United States Navy who made several expeditions to the Arctic in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He is best known for, in Apri ...

, who claimed to have reached the Pole on April 6, 1909, accompanied by American Matthew Henson

Matthew Alexander Henson (August 8, 1866March 9, 1955) was an African American explorer who accompanied Robert Peary on seven voyages to the Arctic over a period of nearly 23 years. They spent a total of 18 years on expeditions together.

and four Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories ...

men named Ootah, Seeglo, Egingwah, and Ooqueah. However, Peary's claim remains controversial. The party that accompanied Peary on the final stage of the journey included no one who was trained in navigation and could independently confirm his own navigational work, which some claim to have been particularly sloppy as he approached the Pole. He traveled with the aid of dogsleds and three separate support crews who turned back at successive intervals before reaching the Pole. Many modern explorers, contend that Peary could not have reached the pole on foot in the time he claimed.

The first undisputed sighting of the Pole was on May 12, 1926 by Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

*Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

*Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including the ...

explorer Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen bega ...

and his American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

sponsor Lincoln Ellsworth

Lincoln Ellsworth (May 12, 1880 – May 26, 1951) was a polar explorer from the United States and a major benefactor of the American Museum of Natural History.

Biography

Lincoln Ellsworth was born on May 12, 1880, to James Ellsworth and Eva F ...

from the airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

''Norge

Norge is Norwegian (bokmål), Danish and Swedish for Norway.

It may also refer to:

People

* Kaare Norge (born 1963), Danish guitarist

* Norge Luis Vera (born 1971), Cuban baseball player

Places

* 11871 Norge, asteroid

Toponyms:

*Norge, Oklah ...

''. ''Norge'', though Norwegian owned, was designed and piloted by the Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

Umberto Nobile

Umberto Nobile (; 21 January 1885 – 30 July 1978) was an Italian aviator, aeronautical engineer and Arctic explorer.

Nobile was a developer and promoter of semi-rigid airships in the years between the two World Wars. He is primarily remembe ...

. The flight started from Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), also known as Spitsbergen, or Spitzbergen, is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. North of mainland Europe, it is about midway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. The islands of the group range ...

and crossed the icecap to Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

. Nobile, along with several scientists and crew from the ''Norge'', overflew the Pole a second time on May 24, 1928 in the airship ''Italia

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

''. The ''Italia'' crashed on its return from the Pole, with the loss of half the crew.

U.S. Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

Joseph O. Fletcher

Joseph Otis Fletcher (May 16, 1920 – July 6, 2008) was an American Air Force pilot and polar explorer.

Biography

He was born outside of Ryegate, Montana on May 16, 1920, to Clarence Bert Fletcher (1884–1944). The family moved to Oklaho ...

and Lieutenant William P. Benedict finally landed a plane at the Pole on May 3, 1952, accompanied by the scientist Albert P. Crary

Albert Paddock Crary (July 25, 1911 – October 29, 1987), was a pioneer polar geophysicist and glaciologist. He was the first person to have set foot on both the North and South Poles, having made it to the North Pole on May 3, 1952 (with Joseph ...

.

Antarctica exploration

Early Western theories believed that in the far south of the globe existed a vast continent, known as

Early Western theories believed that in the far south of the globe existed a vast continent, known as Terra Australis

(Latin: '"Southern Land'") was a hypothetical continent first posited in antiquity and which appeared on maps between the 15th and 18th centuries. Its existence was not based on any survey or direct observation, but rather on the idea that ...

. The rounding of the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

and Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

in the 15th and 16th centuries proved that ''Terra Australis Incognita'' ("Unknown Southern Land"), if it existed, was a continent in its own right. The basic geography of the Antarctic coastline was not understood until the mid-to-late 19th century.

It may safely be said that all the navigators who fell in with the southern ice up to 1750 did so by being driven off their course and not of set purpose. An exception may perhaps be made in favor of Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, H ...

's voyage in HMS ''Paramour'' for magnetic investigations in the South Atlantic when he met the ice in 52° S in January 1700, but that latitude was his farthest south. A determined effort on the part of the French naval officer Pierre Bouvet

Pierre is a masculine given name. It is a French form of the name Peter. Pierre originally meant "rock" or "stone" in French (derived from the Greek word πέτρος (''petros'') meaning "stone, rock", via Latin "petra"). It is a translation ...

to discover the South Land described by a half legendary sieur de Gonneville resulted only in the discovery of Bouvet Island

Bouvet Island ( ; or ''Bouvetøyen'') is an island claimed by Norway, and declared an uninhabited protected nature reserve. It is a subantarctic volcanic island, situated in the South Atlantic Ocean at the southern end of the Mid-Atlantic Ri ...

in 54°10′ S, and in the navigation of 48° of longitude of ice-cumbered sea nearly in 55° S in 1739. In 1771, Yves Joseph Kerguelen sailed from France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

with instructions to proceed south from Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label=Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It incl ...

in search of "a very large continent." He lighted upon a land in 50° S which he called South France, and believed to be the central mass of the southern continent. He was sent out again to complete the exploration of the new land, and found it to be only an inhospitable island which he renamed in disgust the Isle of Desolation, but in which posterity has recognized his courageous efforts by naming it Kerguelen Land.

The obsession of the undiscovered continent culminated in the brain of Alexander Dalrymple

Alexander Dalrymple Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (24 July 1737 – 19 June 1808) was a Scotland, Scottish geographer and the first Hydrographer of the Navy, Hydrographer of the British Admiralty. He was the main proponent of the theory ...

, a hydrographer

Hydrography is the branch of applied sciences which deals with the measurement and description of the physical features of oceans, seas, coastal areas, lakes and rivers, as well as with the prediction of their change over time, for the primary p ...

who was nominated by the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

to command the Transit of Venus

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet, becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a trans ...

expedition to Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

in 1769. The command of the expedition was given by the admiralty to Captain James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

. Sailing in 1772 with the ''Resolution'' and the ''Adventure'' under Captain Tobias Furneaux

Captain Tobias Furneaux (21 August 173518 September 1781) was an English navigator and Royal Navy officer, who accompanied James Cook on his second voyage of exploration. He was one of the first men to circumnavigate the world in both direction ...

, Cook first searched in vain for Bouvet Island

Bouvet Island ( ; or ''Bouvetøyen'') is an island claimed by Norway, and declared an uninhabited protected nature reserve. It is a subantarctic volcanic island, situated in the South Atlantic Ocean at the southern end of the Mid-Atlantic Ri ...

, then sailed for 20 degrees of longitude to the westward in latitude 58° S, and then 30° eastward for the most part south of 60° S, a higher southern latitude than had ever been voluntarily entered before by any vessel. On 17 January 1773 the Antarctic Circle

The Antarctic Circle is the most southerly of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of Earth. The region south of this circle is known as the Antarctic, and the zone immediately to the north is called the Southern Temperate Zone. S ...

was crossed for the first time in history and the two ships reached by , where their course was stopped by ice.

The first land south of the parallel 60° south latitude was discovered by the Englishman William Smith, who sighted Livingston Island

Livingston Island (Russian name ''Smolensk'', ) is an Antarctic island in the Southern Ocean, part of the South Shetlands Archipelago, a group of Antarctic islands north of the Antarctic Peninsula. It was the first land discovered south of 60 ...

on 19 February 1819.

In 1820, several expeditions claimed to have been the first to have sighted Antarctica. The first confirmed sighting of mainland Antarctica cannot be accurately attributed to one single person. It can, however, be narrowed down to three individuals. According to various sources, three men all sighted Antarctica within days or months of each other: Fabian von Bellingshausen

Fabian Gottlieb Thaddeus von Bellingshausen (russian: Фадде́й Фадде́евич Беллинсга́узен, translit=Faddéy Faddéevich Bellinsgáuzen; – ) was a Russian naval officer, cartographer and explorer, who ultimately ...

, a captain in the Russian Imperial Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from a ...

; Edward Bransfield

Edward Bransfield (c. 1785 – 31 October 1852) was an Irish sailor who became an officer in the British Royal Navy, serving as a master on several ships, after being impressed into service in Ireland at the age of 18. He is noted for his par ...

, a captain in the British navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

; and Nathaniel Palmer

Nathaniel Brown Palmer (August 8, 1799June 21, 1877) was an American seal hunter, explorer, sailing captain, and ship designer. He gave his name to Palmer Land, Antarctica, which he explored in 1820 on his sloop ''Hero''. He was born in Stoning ...

, an American sealer out of Stonington, Connecticut

The town of Stonington is located in New London County, Connecticut in the state's southeastern corner. It includes the borough of Stonington (borough), Connecticut, Stonington, the villages of Pawcatuck, Connecticut, Pawcatuck, Lords Point, and W ...

. It is certain that on 28 January 1820 (New Style), the expedition led by Fabian von Bellingshausen

Fabian Gottlieb Thaddeus von Bellingshausen (russian: Фадде́й Фадде́евич Беллинсга́узен, translit=Faddéy Faddéevich Bellinsgáuzen; – ) was a Russian naval officer, cartographer and explorer, who ultimately ...

and Mikhail Petrovich Lazarev

Admiral Mikhail Petrovich Lazarev (russian: Михаил Петрович Лазарев, 3 November 1788 – 11 April 1851) was a Russian fleet commander and an explorer.

Education and early career

Lazarev was born in Vladimir, a scion of the ...

on two ships reached a point within 20 miles (40 km) of the Antarctic mainland and saw ice-fields there. On 30 January 1820, Bransfield sighted Trinity Peninsula