Muybridge Runner on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Eadweard Muybridge (; 9 April 1830 – 8 May 1904, born Edward James Muggeridge) was an English photographer known for his pioneering work in photographic studies of

Eadweard Muybridge (; 9 April 1830 – 8 May 1904, born Edward James Muggeridge) was an English photographer known for his pioneering work in photographic studies of

Edward James Muggeridge was born in

Edward James Muggeridge was born in

From June to November 1867, Muybridge visited

From June to November 1867, Muybridge visited

stereograph

A stereoscope is a device for viewing a stereoscopic pair of separate images, depicting left-eye and right-eye views of the same scene, as a single three-dimensional image.

A typical stereoscope provides each eye with a lens that makes the ima ...

photos by Muybridge" mode="packed">

File:Cooking eggs at the Witches' Cauldron, by Muybridge, Eadweard, 1830-1904.jpg, ''Cooking eggs at the Witches' Cauldron'' (c. 1867–1871)

File:Bay Shore, San Quentin, by Muybridge, Eadweard, 1830-1904.png, ''Bay Shore,

In 1872, the former

In 1872, the former

''The Man Who Stopped Time: The Illuminating Story of Eadweard Muybridge : Pioneer Photographer, Father of the Motion Picture, Murderer''

Joseph Henry Press, 2007 He displayed his photographs on screen and showed moving pictures projected by his zoopraxiscope. He also lectured at the

''Freeze Frame: Eadward Muybridge's Photography of Motion'', 7 October 2000 – 15 March 2001, National Museum of American History, accessed 9 April 2012 Stillman used Muybridge's photos as the basis for his 100 illustrations, and the photographer's research for the analysis, but he gave Muybridge no prominent credit. The historian Phillip Prodger later suggested that Stanford considered Muybridge as just one of his employees, and not deserving of special recognition. Stanford was quite proud of his role in creating the book, and commissioned a portrait of himself by

In 1887, the photos were published as a massive

In 1887, the photos were published as a massive

"The Eadweard Muybridge Collection at the University of Pennsylvania Archives contains 702 of the 784 plates in his Animal Locomotion study" Muybridge's work contributed substantially to developments in the science of

File:Boys playing Leapfrog.jpg, Original collotype

File:Eadweard Muybridge Boys playing Leapfrog (1883–86, printed 1887) animated A.gif, Side view

File:Eadweard Muybridge Boys playing Leapfrog (1883–86, printed 1887) animated F.gif, Front view

File:Nude woman brings a cup of tea; another takes the cup and drinks (rbm-QP301M8-1887-451).jpg, Original collotype

File:Animated - Nude woman brings a cup of tea; another takes the cup and drinks - view 1.gif, Front view

File:Animated - Nude woman brings a cup of tea; another takes the cup and drinks - view 2.gif, Alternative view

In 1888, the University of Pennsylvania donated an album of Muybridge's photographs, which featured students and Philadelphia Zoo animals, to the sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Phenakistoscope

The phenakistiscope (also known by the spellings phénakisticope or phenakistoscope) was the first widespread animation device that created a fluent illusion of motion. Dubbed and ('stroboscopic discs') by its inventors, it has been known unde ...

discs published by Muybridge (1893)" mode="packed">

File:Phenakistoscope 3g07692u.jpg, ''Athletes, Boxing''

File:Phenakistoscope 3g07692a.gif, Spinning disc

File:Phenakistoscope 3g07692b.gif, Mirrored animation detail

File:Phenakistoscope 3g07690u.jpg, ''A Couple  Eadweard Muybridge (; 9 April 1830 – 8 May 1904, born Edward James Muggeridge) was an English photographer known for his pioneering work in photographic studies of

Eadweard Muybridge (; 9 April 1830 – 8 May 1904, born Edward James Muggeridge) was an English photographer known for his pioneering work in photographic studies of motion

In physics, motion is the phenomenon in which an object changes its position with respect to time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed and frame of reference to an observer and mea ...

, and early work in motion-picture projection

Projection, projections or projective may refer to:

Physics

* Projection (physics), the action/process of light, heat, or sound reflecting from a surface to another in a different direction

* The display of images by a projector

Optics, graphic ...

. He adopted the first name "Eadweard" as the original Anglo-Saxon form of "Edward", and the surname "Muybridge", believing it to be similarly archaic.

Born in Kingston upon Thames

Kingston upon Thames (hyphenated until 1965, colloquially known as Kingston) is a town in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames, southwest London, England. It is situated on the River Thames and southwest of Charing Cross. It is notable as ...

, England, at the age of 20 he emigrated to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

as a bookseller, first to New York City, and eventually to San Francisco. In 1860, he planned a return trip to Europe, and suffered serious head injuries in a stagecoach crash in Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

en route. He spent the next few years recuperating in Kingston upon Thames, where he took up professional photography, learned the wet-plate collodion process, and secured at least two British patents for his inventions. He returned to San Francisco in 1867, a man with a markedly changed personality. In 1868, he exhibited large photographs of Yosemite Valley

Yosemite Valley ( ; ''Yosemite'', Miwok for "killer") is a U-shaped valley, glacial valley in Yosemite National Park in the western Sierra Nevada (U.S.), Sierra Nevada mountains of Central California. The valley is about long and deep, surroun ...

, and began selling popular stereograph

A stereoscope is a device for viewing a stereoscopic pair of separate images, depicting left-eye and right-eye views of the same scene, as a single three-dimensional image.

A typical stereoscope provides each eye with a lens that makes the ima ...

s of his work.

In 1874, Muybridge shot and killed Major Harry Larkyns, his wife's lover, but was acquitted in a controversial jury trial, on the grounds of justifiable homicide

The concept of justifiable homicide in criminal law is a defense to culpable homicide (criminal or negligent homicide). Generally, there is a burden of production of exculpatory evidence in the legal defense of justification. In most countri ...

. In 1875, he travelled for more than a year in Central America on a photographic expedition.

Today, Muybridge is best known for his pioneering chronophotography

Chronophotography is a photographic technique from the Victorian era which captures a number of phases of movements. The best known chronophotography works were mostly intended for the scientific study of locomotion, to discover practical informa ...

of animal locomotion

Animal locomotion, in ethology, is any of a variety of methods that animal (biology), animals use to move from one place to another. Some modes of locomotion are (initially) self-propelled, e.g., running, swimming, jumping, flying, hopping, soari ...

between 1878 and 1886, which used multiple cameras to capture the different positions in a stride, and for his zoopraxiscope

The zoopraxiscope (initially named ''zoographiscope'' and ''zoogyroscope'') is an early device for displaying moving images and is considered an important predecessor of the movie projector. It was conceived by photographic pioneer Eadweard Mu ...

, a device for projecting painted motion pictures from glass discs that pre-dated the flexible perforated film strip used in cinematography

Cinematography (from ancient Greek κίνημα, ''kìnema'' "movement" and γράφειν, ''gràphein'' "to write") is the art of motion picture (and more recently, electronic video camera) photography.

Cinematographers use a lens to focu ...

. From 1883 to 1886, he entered a very productive period at the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, producing over 100,000 images of animals and humans in motion, occasionally capturing what the human eye could not distinguish as separate moments in time.

During his later years, Muybridge gave many public lectures and demonstrations of his photography and early motion picture sequences, travelling frequently in England and Europe to publicise his work in cities such as London and Paris. He also edited and published compilations of his work, some of which are still in print today, which greatly influenced visual artists and the developing fields of scientific and industrial photography. He retired to his native England permanently in 1894. In 1904, the year of his death, the Kingston Museum was opened in his hometown, and it continues to house a substantial collection of his works in a dedicated gallery.

Names

Edward James Muggeridge was born and raised in England. Muggeridge changed his name several times, starting with "Muggridge". From 1855 to 1865, he mainly used the surname "Muygridge". From 1865 onward, he used the surname "Muybridge". In addition, he used the pseudonym ''Helios

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Helios (; grc, , , Sun; Homeric Greek: ) is the deity, god and personification of the Sun (Solar deity). His name is also Latinized as Helius, and he is often given the epithets Hyper ...

'' (Titan of the sun) for his early photography. He also used this as the name of his studio and gave it to his only son, as a middle name: Florado Helios Muybridge, born in 1874.

While travelling in 1875 on a photography expedition in the Spanish-speaking nations of Central America, the photographer advertised his works under the name "Eduardo Santiago Muybridge" in Guatemala

Guatemala ( ; ), officially the Republic of Guatemala ( es, República de Guatemala, links=no), is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico; to the northeast by Belize and the Caribbean; to the east by H ...

.

After an 1882 trip to England, he changed the spelling of his first name to "Eadweard", the Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

form of his name. The spelling was probably derived from the spelling of King Edward's Christian name as shown on the plinth of the Kingston coronation stone

The Coronation Stone is an ancient sarsen stone block which is believed to have been the site of the coronation of seven Anglo-Saxon kings. It is presently located next to the Guildhall in Kingston upon Thames, England. Kingston is now a town in ...

, which had been re-erected in 1850 in Muybridge's hometown, 100 yards from his childhood family home. He used "Eadweard Muybridge" for the rest of his career.

Others frequently misspelled his surname as "Maybridge", "Moybridge", or "Mybridge". His gravestone carries his name as "Eadweard Maybridge".

1830–1850: Early life and family

Edward James Muggeridge was born in

Edward James Muggeridge was born in Kingston upon Thames

Kingston upon Thames (hyphenated until 1965, colloquially known as Kingston) is a town in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames, southwest London, England. It is situated on the River Thames and southwest of Charing Cross. It is notable as ...

, in the county of Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

in England (now Greater London), on 9 April 1830 to John and Susanna Muggeridge; he had three brothers. His father was a grain and coal merchant, with business spaces on the ground floor of their house adjacent to the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

at No. 30 High Street. The family lived in the rooms above. After his father died in 1843, his mother carried on the business.

His younger cousins Norman Selfe

Norman Selfe (9 December 1839 – 15 October 1911) was an Australian engineer, naval architect, inventor, urban planner and outspoken advocate of technical education. After emigrating to Sydney with his family from England as a boy he bec ...

(1839–1911) and Maybanke Anderson

Maybanke Susannah Anderson (nee Selfe and also known as Maybanke Wolstenholme; 16 February 1845 – 15 April 1927) was an Australian political reformer involved in women's suffrage and Australian federation.

Early life

Maybanke Selfe was bor ...

(née Selfe; 1845–1927), also spent part of their childhood in Kingston upon Thames. They moved to Australia and Norman, following a family tradition, became a renowned engineer, while Maybanke made fame as a suffragette. pp. 24–25

His paternal great-grandparents were Robert Muggeridge and Hannah Charman, who owned a farm. Their oldest son John Muggeridge (1756–1819) was Edward's grandfather; he was a stationer who taught Edward the business. Several uncles and cousins, including Henry Muggeridge (Sheriff of London), were corn merchants in the City of London. All were born in Banstead, Surrey. Edward's younger brother George, born in 1833, lived with their uncle Samuel in 1851, after the death of their father in 1843.

1850–1860: Bookselling in America

At the age of 20, Muybridge decided to seek his fortune. He turned down an offer of money from his grandmother, saying "No, thank you Grandma, I'm going to make a name for myself. If I fail, you will never hear of me again." Muybridge emigrated to the United States, arriving in New York City in 1850. Here, he was possibly a partner in the book business enterprise Muygridge & Bartlett together with a medical student, which existed for about a year. He spent his first years importing and selling books from the UK, and became familiar with early photography through his acquaintance with New York daguerreotypist Silas T. Selleck. Muybridge arrived inNew Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

in January 1855, and was registered there as a book agent by April.

Muybridge probably arrived in California around the autumn of 1855, when it had not yet been a state for more than five years. He visited the new state capital, Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Sacramento

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

, as an agent selling illustrated Shakespeare books in April 1856, and soon after settled at 113 Montgomery Street in San Francisco. From this address he sold books and art (mostly prints), in a city that was still the booming "capital of the Gold Rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New Z ...

" in the "Wild West

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of American expansion in mainland North America that began with European colonial ...

". There were already 40 bookstores and a dozen photography studios in town, and he even shared his address with a photo gallery, right next to another bookstore. He partnered with W.H. Oakes as an engraver and publisher of lithograph prints, and still functioned as a book agent for the London Printing and Publishing Company.

In April 1858, Muybridge moved his store to 163 Clay Street, where his friend Silas Selleck now had a photo gallery. Muygridge was a member of the Mechanic's Institute of the City of San Francisco. In 1859, he was elected as one of the directors for the San Francisco Mercantile Library Association.

Muybridge sold original landscape photography by Carleton Watkins

Carleton E. Watkins (1829–1916) was an American photographer of the 19th century. Born in New York, he moved to California and quickly became interested in photography. He focused mainly on landscape photography, and Yosemite Valley was a ...

, as well as photographic copies of paintings. It remains uncertain whether or not Muygridge personally made such copies, or familiarized himself with photographic techniques in any fashion before 1860, although Muybridge claimed in 1881 that he "came to California in 1855, and most of the time since and all of the time since 1860 (...) had been diligently, and at the same time studiously, been engaged in photography."

Edward's brother George Muybridge came to San Francisco in 1858 but died of tuberculosis soon after. Their youngest brother Thomas S. Muygridge arrived in 1859, and it soon became clear that Edward planned to stop operating his bookstore business. On 15 May 1860, Edward published a special announcement in the ''Bulletin'' newspaper: "I have this day sold to my brother, Thomas S. Muygridge, my entire stock of Books, Engravings, etc.(...) I shall on 5th June leave for New York, London, Berlin, Paris, Rome, and Vienna, etc." Although he altered his plans, he eventually took a cross-country stagecoach on 2 July to catch a ship in New York.

1860–1866: Serious accident, recuperation, early patents, and short career as venture capitalist

In July 1860, Muybridge suffered a head injury in a violent runawaystagecoach

A stagecoach is a four-wheeled public transport coach used to carry paying passengers and light packages on journeys long enough to need a change of horses. It is strongly sprung and generally drawn by four horses although some versions are draw ...

crash at the Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

border, which killed the driver and one passenger, and badly injured every other passenger on board. Muybridge was ejected from the vehicle and hit his head on a rock or other hard object. He woke up in a hospital bed at Fort Smith, Arkansas

Fort Smith is the third-largest city in Arkansas and one of the two county seats of Sebastian County. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 89,142. It is the principal city of the Fort Smith, Arkansas–Oklahoma Metropolitan Statistical Are ...

, with no recollection of the nine days after he had taken supper at a wayside cabin away, not long before the accident. He suffered from a bad headache, double vision, deafness, loss of taste and smell, and confusion. It was later claimed that his hair turned from brown to grey in three days. The problems persisted fully for three months and to a lesser extent for a year.

Arthur P. Shimamura, an experimental psychologist

Experimental psychology refers to work done by those who apply experimental methods to psychological study and the underlying processes. Experimental psychologists employ human participants and animal subjects to study a great many topics, in ...

at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

, has speculated that Muybridge suffered substantial injuries to the orbitofrontal cortex

The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) is a prefrontal cortex region in the frontal lobes of the brain which is involved in the cognitive process of decision-making. In non-human primates it consists of the association cortex areas Brodmann area 11, 12 ...

that probably also extended into the anterior temporal lobes, which may have led to some of the emotional, eccentric behaviour reported by friends in later years, as well as freeing his creativity from conventional social inhibitions. Today, there is still little effective treatment for this kind of injury.

Muybridge was treated at Fort Smith for three weeks before he went to a doctor in New York City. He fled the noise of the city and stayed in the countryside. He then went back to New York for six weeks and sued the stage company, which earned him a $2,500 compensation. Eventually, he felt well enough to travel to England, where he received medical care from Sir William Gull (who was also personal physician to Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

), and was prescribed abstinence of meat, alcohol, and coffee for over a year. Gull also recommended rest and outdoor activities, and considering a change in profession.

Muybridge stayed with his mother in Kennington

Kennington is a district in south London, England. It is mainly within the London Borough of Lambeth, running along the boundary with the London Borough of Southwark, a boundary which can be discerned from the early medieval period between the ...

and later with his aunt while in England. Muybridge later stated that he had become a photographer at the suggestion of Gull. However, while outdoors photography might have helped in getting some fresh air, dragging around heavy equipment and working with chemicals in a dark room did not comply with the prescriptions for rest that Gull preferred to offer.

On 28 September 1860, "E. Muggeridge, of New York" applied for British patent no. 2352 for "An improved method of, and apparatus for, plate printing" via London solicitor August Frederick Sheppard.

On 1 August 1861, Muygridge received British patent no. 1914 for "Improvements in machinery or apparatus for washing clothes and other textile articles". On 28 October the French version of this patent was registered. He wrote a letter to his uncle Henry, who had emigrated to Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

(Australia), with details of the patents and he also mentioned having to visit Europe for business for several months. Muygridge's inventions (or rather: improved machinery) were demonstrated at the 1862 International Exhibition.

Muybridge's activities and whereabouts between 1862 and 1865 are not very well documented. He turned up in Paris in 1862 and again in 1864. In 1865 he was one of the directors for the Austin Consolidated Silver Mines Company (limited) and for The Ottoman Company (limited)/The Bank of Turkey (limited), under his new name "Muybridge". Both enterprises were very short-lived due to the Panic of 1866

The Panic of 1866 was an international financial downturn that accompanied the failure of Overend, Gurney and Company in London, and the ''corso forzoso'' abandonment of the silver standard in Italy.

In Britain, the economic impacts are held p ...

, and Muybridge chaired the meetings in which the companies were dissolved during the spring of 1866.

Muybridge may have taken up photography sometime between 1861 and 1866. He possibly learned the wet-plate collodion process in England, and was possibly influenced by some of well-known English photographers of those years, such as Julia Margaret Cameron

Julia Margaret Cameron (''née'' Pattle; 11 June 1815 – 26 January 1879) was a British photographer who is considered one of the most important portraitists of the 19th century. She is known for her soft-focus close-ups of famous Victorian m ...

, Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (1865) and its sequel ...

, and Roger Fenton

Roger Fenton (28 March 1819 – 8 August 1869) was a British photographer, noted as one of the first war photographers.

Fenton was born into a Lancashire merchant family. After graduating from London with an Arts degree, he became interested i ...

. However, it remains unclear how much he had already learned before the accident and how much he may have learned after his return to the United States.

1867–1873: Helios, photographer of the American West

Muybridge returned to San Francisco on 13 February 1867 a changed man. Reportedly his hair had turned from black to grey within three days after his 1860 accident. Friends and associates later stated that he had changed from a smart and pleasant businessman into an eccentric artist. He was much more careless about his appearance, was easily agitated, could suddenly take objection to people and soon after act like nothing had happened, and he would regularly misstate previously-arranged business deals. His care about whether he judged something to be beautiful had become much stronger than his care for money; he easily refused payment if a customer seemed to be slightly critical of his work. Photographer Silas Selleck, who had known Muybridge from New York since circa 1852 and had been a close friend since 1855, claimed that he could hardly recognize Muybridge after his return. Muybridge converted a lightweight two-wheel, one-horsecarriage

A carriage is a private four-wheeled vehicle for people and is most commonly horse-drawn. Second-hand private carriages were common public transport, the equivalent of modern cars used as taxis. Carriage suspensions are by leather strapping an ...

into a portable darkroom to carry out his work, and with a logo on the back dubbed it "Helios' Flying Studio". He had acquired highly proficient technical skills and an artist's eye, and became very successful in photography, focusing principally on landscape and architectural subjects. An 1868 advertisement stated a wide scope of subjects: "Helios is prepared to accept commissions to photograph Private Residences, Ranches, Mills, Views, Animals, Ships, etc., anywhere in the city, or any portion of the Pacific Coast. Architects', Surveyors' and Engineers' Drawings copied mathamatically (sic

The Latin adverb ''sic'' (; "thus", "just as"; in full: , "thus was it written") inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any e ...

) correct. Photographic copies of Paintings and Works of Art."

Muybridge constantly tinkered with his cameras and chemicals, trying to improve the sales appeal of his pictures. In 1869, he patented a "sky shade" to reduce the tendency of intense blue outdoors skies to bleach out the images of the blue-sensitive photographic emulsion

Photographic emulsion is a light-sensitive colloid used in film-based photography. Most commonly, in silver-gelatin photography, it consists of silver halide crystals dispersed in gelatin. The emulsion is usually coated onto a substrate of g ...

s of the time. An article published in 2017 and an expanded book document that Muybridge heavily edited and modified his photos, inserting clouds or the moon, even adding volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates are ...

s to his pictures for artistic effects.

San Francisco views

Helios produced over 400 differentstereograph

A stereoscope is a device for viewing a stereoscopic pair of separate images, depicting left-eye and right-eye views of the same scene, as a single three-dimensional image.

A typical stereoscope provides each eye with a lens that makes the ima ...

cards, initially sold through Seleck's Cosmopolitan Gallery at 415 Montgomery Street, and later through other distributors, such as Bradley

Bradley is an English surname derived from a place name meaning "broad wood" or "broad meadow" in Old English.

Like many English surnames Bradley can also be used as a given name and as such has become popular.

It is also an Anglicisation of t ...

& Rulofson. Many of these cards showed views of San Francisco and its surroundings. Stereo cards were extremely popular at the time and thus could be sold in large quantities for a very low price, to tourists as a souvenir, or to proud citizens and collectors.

Early in his new career, Muybridge was hired by Robert B. Woodward (1824–1879) to take extensive photos of his Woodward's Gardens

Woodward's Gardens, commonly referred to as The Gardens, was a combination amusement park, museum, art gallery, zoo, and aquarium operating from 1866 to 1891 in the Mission District, San Francisco, Mission District of San Francisco, California. ...

, a combination amusement park, zoo, museum, and aquarium that had opened in San Francisco in 1866.

Muybridge took pictures of ruins after the 21 October 1868 Hayward earthquake.

During the construction of the San Francisco Mint

The San Francisco Mint is a branch of the United States Mint. Opened in 1854 to serve the gold mines of the California Gold Rush, in twenty years its operations exceeded the capacity of the first building. It moved into a new one in 1874, now kno ...

in 1870–1872, Muybridge made a series of images of the building's progress, documenting changes over time in a fashion similar to time-lapse photography

Time-lapse photography is a technique in which the frequency at which film frames are captured (the frame rate) is much lower than the frequency used to view the sequence. When played at normal speed, time appears to be moving faster and thus ...

. These images may have attracted the attention of Leland Stanford

Amasa Leland Stanford (March 9, 1824June 21, 1893) was an American industrialist and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 8th governor of California from 1862 to 1863 and represented California in the United States Se ...

, who would later hire Muybridge to develop an unprecedented series of photos spaced in time.

Yosemite

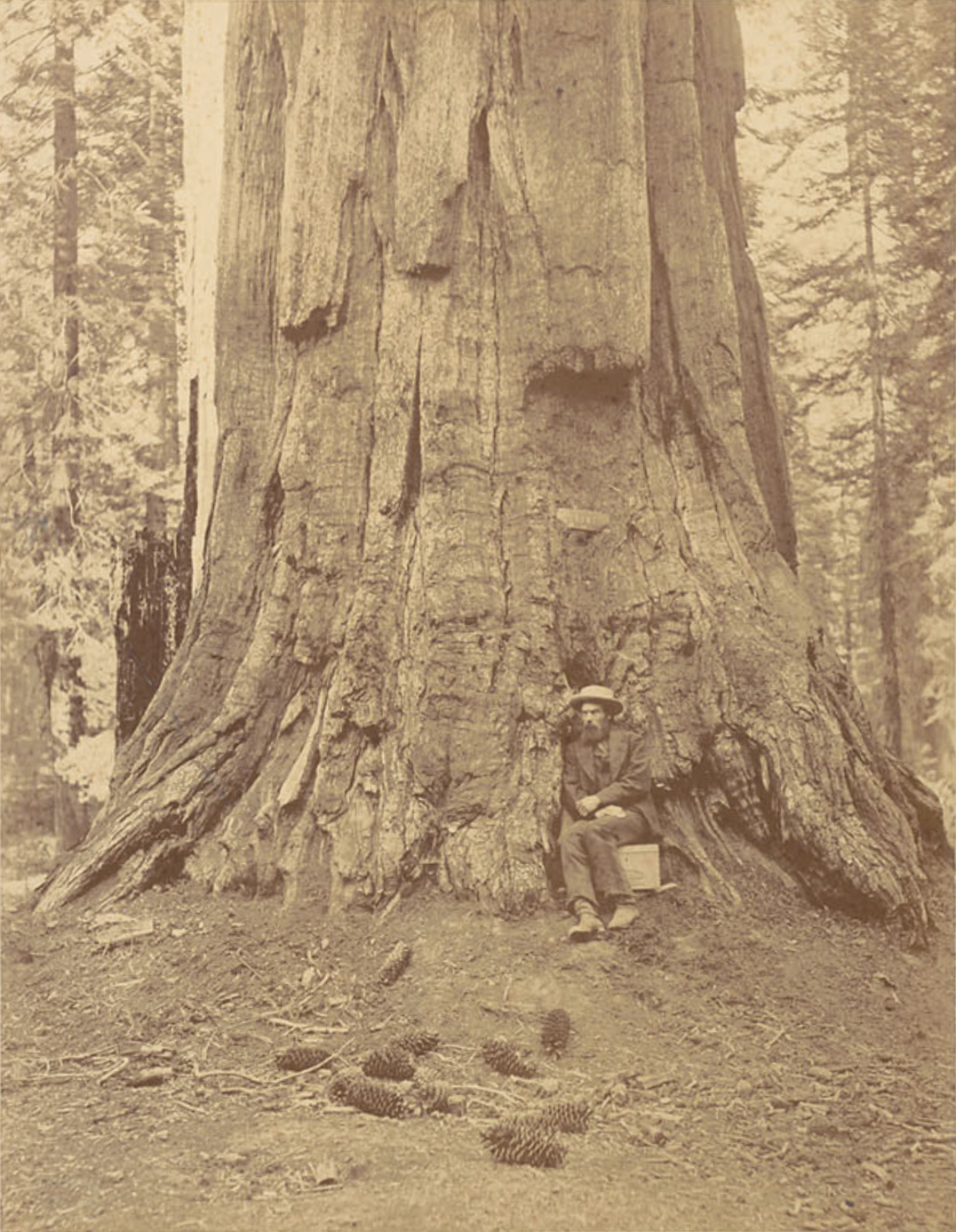

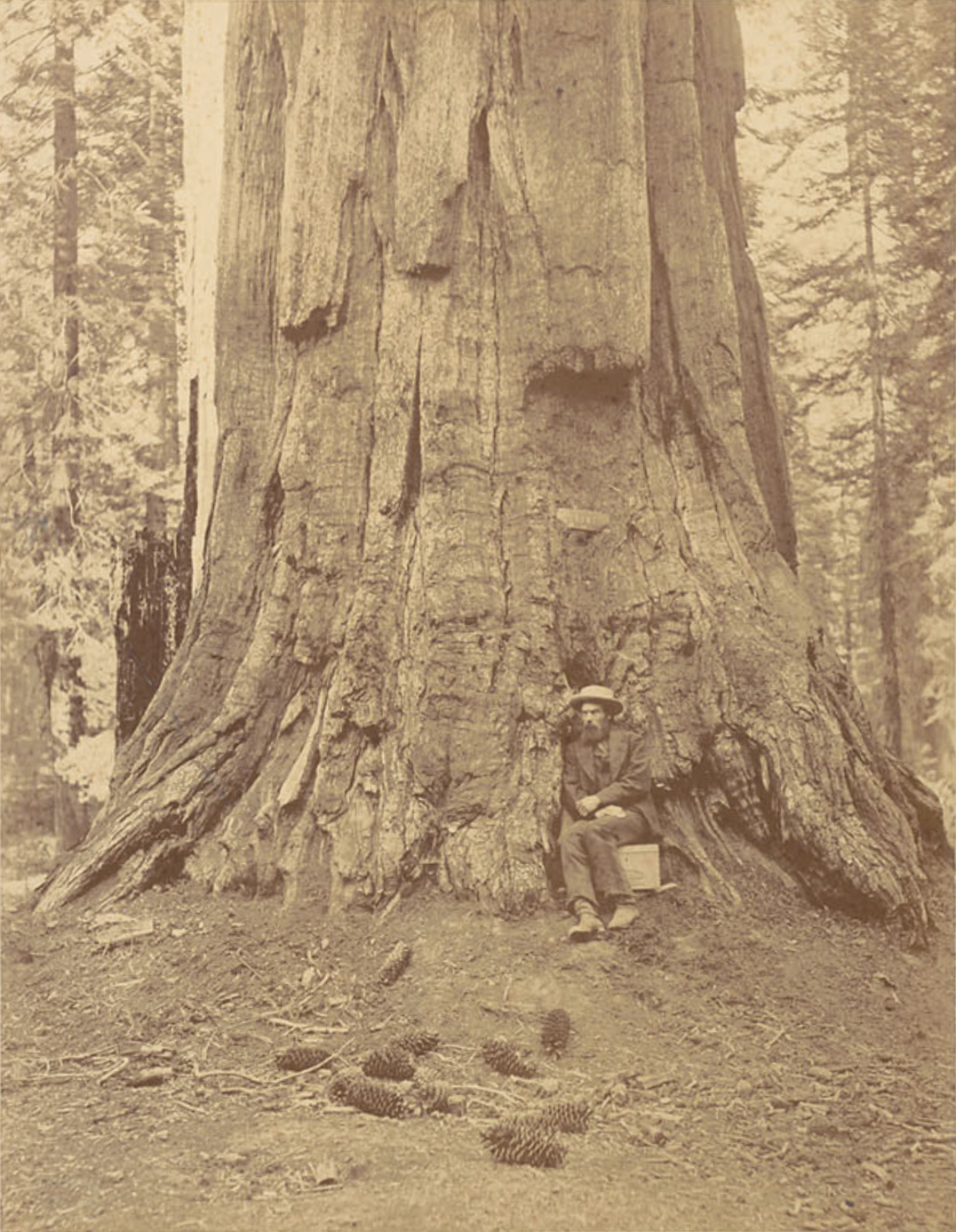

From June to November 1867, Muybridge visited

From June to November 1867, Muybridge visited Yosemite Valley

Yosemite Valley ( ; ''Yosemite'', Miwok for "killer") is a U-shaped valley, glacial valley in Yosemite National Park in the western Sierra Nevada (U.S.), Sierra Nevada mountains of Central California. The valley is about long and deep, surroun ...

He took enormous safety risks to make his photographs, using a heavy view camera

A view camera is a large-format camera in which the lens forms an inverted image on a ground-glass screen directly at the film plane. The image is viewed and then the glass screen is replaced with the film, and thus the film is exposed to exact ...

and stacks of glass plate

Photographic plates preceded photographic film as a capture medium in photography, and were still used in some communities up until the late 20th century. The light-sensitive emulsion of silver salts was coated on a glass plate, typically thin ...

negatives. A stereograph he published in 1872 shows him sitting casually on a projecting rock over the Yosemite Valley, with of empty space yawning below him. He returned with numerous stereoscopic views and larger plates. He selected 20 pictures to be retouched and manipulated for a subscription series that he announced in February 1868. Twenty original photographs (possibly the same) were used to illustrate John S. Hittel's guide book ''Yosemite: Its Wonders and Its Beauties'' (1868).

Some of the pictures were taken of the same scenes shot by his contemporary Carleton Watkins

Carleton E. Watkins (1829–1916) was an American photographer of the 19th century. Born in New York, he moved to California and quickly became interested in photography. He focused mainly on landscape photography, and Yosemite Valley was a ...

. Muybridge's photographs showed the grandeur and expansiveness of the West; if human figures were portrayed, they were dwarfed by their surroundings, as in Chinese landscape paintings. In comparing the styles of the two photographers, Watkins has been called "a classicist, making serene, stately pictures of a still, eternal world of beauty", while Muybridge was "a romantic who sought out the uncanny, the unsettling, the uncertain". In the 21st century there have been claims that many landscape photos attributed to Muybridge were actually made by or under the close guidance of Watkins, but these claims are disputed. Regardless, Muybridge started to develop his own leading-edge innovations in photography, especially in the capturing of ever-faster motion.

Government commissions

In 1868, Muybridge was commissioned by the US government to travel to the newly acquired US territory of Alaska to photograph theTlingit

The Tlingit ( or ; also spelled Tlinkit) are indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Their language is the Tlingit language (natively , pronounced ),

Native Americans, occasional Russian inhabitants, and dramatic landscapes.Paula Fleming and Judith Lusky, ''The North American Indians in Early Photographs'', Dorset Press, 1988, (source: Ralph W. Andrews, 1964 and David Mattison, 1985)

In 1871, the United States Lighthouse Board

The United States Lighthouse Board was the second agency of the U.S. federal government, under the Department of Treasury, responsible for the construction and maintenance of all lighthouses and navigation aids in the United States, between 18 ...

hired Muybridge to photograph lighthouses of the American West Coast. From March to July, he travelled aboard the Lighthouse Tender ''Shubrick'' to document these structures.

In 1873, Muybridge was commissioned by the US Army to photograph the "Modoc War

The Modoc War, or the Modoc Campaign (also known as the Lava Beds War), was an armed conflict between the Native American Modoc people and the United States Army in northeastern California and southeastern Oregon from 1872 to 1873. Eadweard M ...

" dispute with the Native American tribe in northern California and Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

. A number of these photographs were carefully staged and posed for maximum effect, despite the long exposures required by the slow photographic emulsion

Photographic emulsion is a light-sensitive colloid used in film-based photography. Most commonly, in silver-gelatin photography, it consists of silver halide crystals dispersed in gelatin. The emulsion is usually coated onto a substrate of g ...

s of the time.

San Quentin

San Quentin State Prison (SQ) is a California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation state prison for men, located north of San Francisco in the unincorporated place of San Quentin in Marin County.

Opened in July 1852, San Quentin is the o ...

'' (c. 1867–1874)

File:Alaska Ter. - Sitka from Japanese Island, by Muybridge, Eadweard, 1830-1904.jpg, ''Sitka from Japanese Island'' (1868)

File:Alaska Ter. - Fort Tongass. Group of Indians, by Muybridge, Eadweard, 1830-1904.jpg, ''Fort Tongass

Fort Tongass was a United States Army base on Tongass Island, in the southernmost Alaska Panhandle, located adjacent to the village of the group of Tlingit people on the east side of the island.

, Group of Indians'' (1868)

File:South Farallon Island, Sea Lions in Main Top Bay, by Muybridge, Eadweard, 1830-1904.png, ''South Farallon Island

The Farallon Islands, or Farallones (from the Spanish language, Spanish ''farallón'' meaning "pillar" or "sea cliff"), are a group of islands and sea Stack (geology), stacks in the Gulf of the Farallones, off the coast of San Francisco, Cali ...

, Sea Lions in Main Top Bay'' (c. 1867–1872)

File:Mosquito Fall, by Muybridge, Eadweard, 1830-1904.jpg, ''Mosquito Fall'' (c. 1868–1873)

File:Paiute Chief's Lodge, by Muybridge, Eadweard, 1830-1904.jpg, ''Paiute

Paiute (; also Piute) refers to three non-contiguous groups of indigenous peoples of the Great Basin. Although their languages are related within the Numic group of Uto-Aztecan languages, these three groups do not form a single set. The term "Pai ...

Chief's Lodge'' (c. 1870)

File:A Modoc Warrior on the War Path (15980282246).jpg, ''A Modoc Warrior on the War Path'' (1873)

1872–1879: Stanford and horse gaits

In 1872, the former

In 1872, the former governor of California

The governor of California is the head of government of the U.S. state of California. The governor is the commander-in-chief of the California National Guard and the California State Guard.

Established in the Constitution of California, the g ...

, Leland Stanford

Amasa Leland Stanford (March 9, 1824June 21, 1893) was an American industrialist and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 8th governor of California from 1862 to 1863 and represented California in the United States Se ...

, a businessman and race-horse owner, hired Muybridge for a portfolio depicting his mansion and other possessions, including his racehorse Occident.

Stanford also wanted a proper picture of the horse at full speed, and was frustrated that the existing depictions and descriptions seemed incorrect. The human eye could not fully break down the action at the quick gaits of the trot

The trot is a ten-beat diagonal horse gait where the diagonal pairs of legs move forward at the same time with a moment of suspension between each beat. It has a wide variation in possible speeds, but averages about . A very slow trot is someti ...

and gallop

The canter and gallop are variations on the fastest gait that can be performed by a horse or other equine. The canter is a controlled three-beat gait, while the gallop is a faster, four-beat variation of the same gait. It is a natural gait pos ...

. Up until this time, most artists painted horses at a trot with one foot always on the ground; and at a full gallop with the front legs extended forward and the hind legs extended to the rear, and all feet off the ground. There are stories that Stanford had made a $25,000 bet on his theories about horse locomotion, but no evidence has been found of such a wager. Instead, it has been estimated that he would spend a total of $50,000 over the next several years, to fund his investigations.

In 1873, Muybridge managed to use a single camera to shoot a small and very fuzzy picture of the racehorse Occident running, at Union Park racetrack in Sacramento

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

. Because of the insensitivity of the photographic emulsion

Photographic emulsion is a light-sensitive colloid used in film-based photography. Most commonly, in silver-gelatin photography, it consists of silver halide crystals dispersed in gelatin. The emulsion is usually coated onto a substrate of g ...

s used, early pictures were little more than blurry silhouette

A silhouette ( , ) is the image of a person, animal, object or scene represented as a solid shape of a single colour, usually black, with its edges matching the outline of the subject. The interior of a silhouette is featureless, and the silhou ...

s. They both agreed that the image lacked quality, but Stanford was excited to finally have a reliable depiction of a running horse. No copy of this earliest image has yet resurfaced.

Muybridge promised to study better solutions, but his work on higher-speed photography would take several years to develop, and was also delayed by events in his personal life. With the aid of engineers and technicians from the Central Pacific Railroad

The Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) was a rail company chartered by Pacific Railroad Acts, U.S. Congress in 1862 to build a railroad eastwards from Sacramento, California, to complete the western part of the "First transcontinental railroad" in N ...

(Stanford was one of the founding directors), Muybridge experimented with ever-faster mechanical shutters, and began developing state-of-the-art electrically-triggered mechanisms. He also experimented with more sensitive photographic emulsions to work with the shorter exposure times.

In July 1877, Muybridge made a new picture of Occident at full speed, with improved techniques and a much clearer result. To enhance the still-fuzzy picture, he had it recreated by a retouch artist and published as a cabinet card

The cabinet card was a style of photograph which was widely used for photographic portraiture after 1870. It consisted of a thin photograph mounted on a card typically measuring 108 by 165 mm ( by inches).

History

The '' carte de visite' ...

. The news about this breakthrough in instantaneous photography was spread enthusiastically, but several critics believed that the heavily-manipulated image could not be a truthful depiction of the horse. Muybridge allowed reporters to study the original negative, but as he and Stanford were planning a new project that would convince everyone, they saw no need to prove that this image was authentic. The original negative has not yet resurfaced.

In June 1878, Muybridge created sequential series of photographs, now with a battery of 12 cameras along the race track at Stanford's Palo Alto Stock Farm (now the campus of Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is consider ...

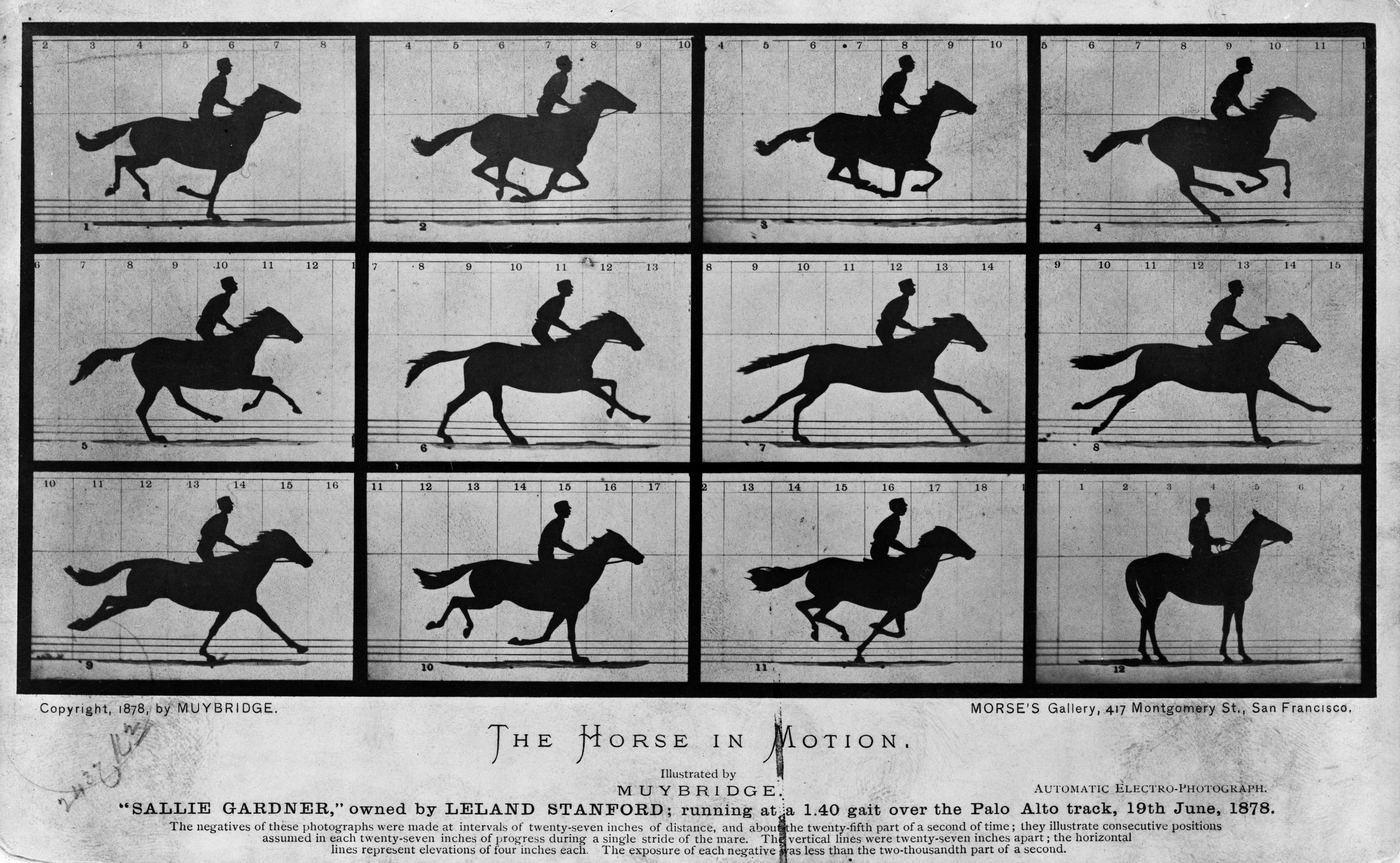

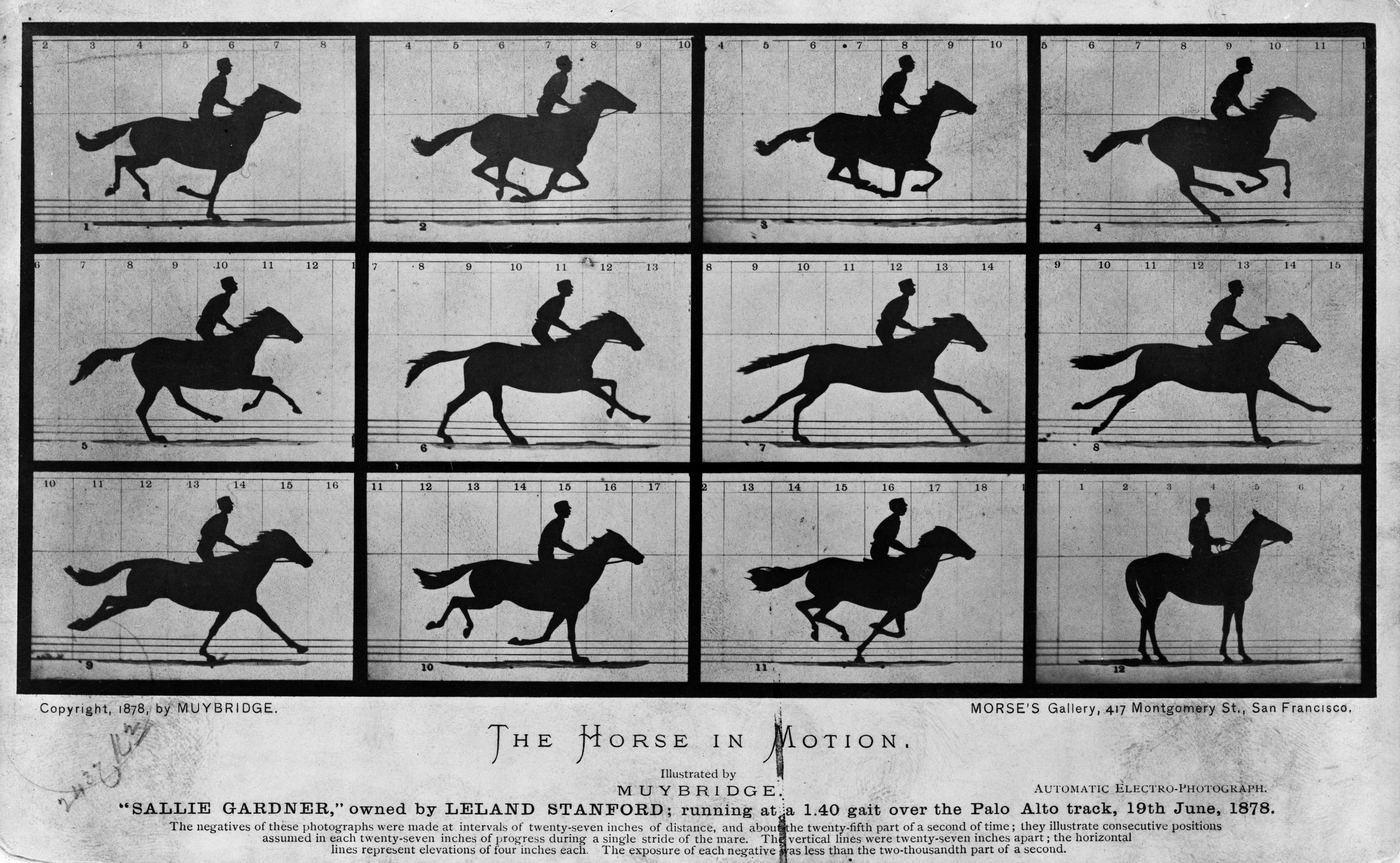

). The shutters were automatically triggered when the wheel of a cart or the breast or legs of a horse tripped wires connected to an electromagnetic circuit. For a session on 15 June 1878, the press and a selection of turf men were invited to witness the process. An accident with a snapping strap was captured on the negatives and shown to the attendees, convincing even the most sceptical witnesses. The news of this success was reported worldwide.

''The Daily Alta California

The ''Alta California'' or ''Daily Alta California'' (often miswritten ''Alta Californian'' or ''Daily Alta Californian'') was a 19th-century San Francisco newspaper.

''California Star''

The ''Daily Alta California'' descended from the first ...

'' reported that Muybridge first exhibited magic lantern

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name , is an early type of image projector that used pictures—paintings, prints, or photographs—on transparent plates (usually made of glass), one or more lenses, and a light source. Because a si ...

projected slides of the photographs at the San Francisco Art Association The San Francisco Art Association (SFAA) was an organization that promoted California artists, held art exhibitions, published a periodical, and established the first art school west of Chicago. The SFAA – which, by 1961, completed a long sequence ...

on 8 July 1878. Newspapers were not yet able to reproduce detailed photographs, so the images were widely printed as woodcut

Woodcut is a relief printing technique in printmaking. An artist carves an image into the surface of a block of wood—typically with gouges—leaving the printing parts level with the surface while removing the non-printing parts. Areas that ...

engravings. ''Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it i ...

'' was among the publications at the time that carried reports and engravings of Muybridge's groundbreaking images. Six different series were soon published as cabinet cards, entitled ''The Horse in Motion

''The Horse in Motion'' is a series of cabinet cards by Eadweard Muybridge, including six cards that each show a sequential series of six to twelve "automatic electro-photographs" depicting the movement of a horse. Muybridge shot the photogr ...

''.

Many people were amazed at the previously unseen positions of the horse's legs and the fact that a running horse at regular intervals had all four hooves in the air. This did not take place when the horse's legs were extended to the front and back, as imagined by contemporary illustrators, but when its legs were collected beneath its body as it switched from "pulling" with the front legs to "pushing" with the back legs.

In 1879, Muybridge continued with additional studies using 24 cameras, and published a very limited edition portfolio of the results.

Muybridge had images from his motion studies hand-copied in the form of silhouettes or line drawings onto a disc, to be viewed in the machine he had invented, which he called a "zoopraxiscope

The zoopraxiscope (initially named ''zoographiscope'' and ''zoogyroscope'') is an early device for displaying moving images and is considered an important predecessor of the movie projector. It was conceived by photographic pioneer Eadweard Mu ...

". Later, his more-detailed images were hand-coloured and marketed commercially. A device he developed was later regarded as an early movie projector, and the process was an intermediate stage toward motion pictures or cinematography.

1878: San Francisco panorama

In 1878, Muybridge made a notable 13-part 360° photographic panorama of San Francisco. He presented a copy to the wife of Leland Stanford. Today, it can be viewed on the Internet as a seamlessly-spliced panorama, or as a QuickTime Virtual Reality (QTVR) panorama. That same year, he applied for a patent on a camera sequence shutter to photograph moving objects, with a mechanical trigger. Later that year, he applied for a further patent, this time using an electrical trigger. He also filed for British and French patents.1871–1881: Personal life, marriage, murder, acquittal, paternity, and divorce

On 20 May 1871, 41-year-old Muybridge married 21-year-old divorcee Flora Shallcross Stone (née Downs). The differences in their tastes and temperaments were understood to have been due to their age difference. Muybridge did not care for many of the amusements that she sought, so she went to the theatre and other attractions without him, and he seemed to be fine with that. Muybridge was more of the type that would stay up all night to read classics. Muybridge was also used to leaving home by himself for days, weeks or even months, visiting faraway places for personal projects or assignments. This did not change after his marriage. On 14 April 1874 Flora gave birth to a son, Florado Helios Muybridge. At some stage, Flora became romantically involved with one of their friends, Harry Larkyns. Muybridge intervened several times and believed the affair was over when he sent Flora to stay with a relative and Larkyns found a job at a mine near Calistoga, California. In mid-October 1874, Muybridge learned how serious the relationship between his wife and Larkyns really was. Flora's maternity nurse revealed many details and she had in her possession some love letters that the couple had still been writing to each other. At her place, Muybridge also came across a picture of Florado with "Harry" written on the back in Flora's handwriting, suggesting that she believed the child to be fathered by Larkyns. On 17 October, Muybridge went to Calistoga to track down Larkyns. Upon finding him, Muybridge said, "I have a message for you from my wife", and shot himpoint-blank

Point-blank range is any distance over which a certain firearm can hit a target without the need to compensate for bullet drop, and can be adjusted over a wide range of distances by sighting in the firearm. If the bullet leaves the barrel paral ...

. Larkyns died that night, and Muybridge was arrested without protest and put in the Napa jail.

A ''Sacramento Daily Union'' reporter visited Muybridge in jail for an hour and related how he was coping with the situation. Muybridge was in moderately good spirits and very hopeful. He felt he was treated very kindly by the officers and was a little proud of the influence he had on other inmates, which had earned him everyone's respect. He had protested the abuse of a "Chinaman" from a tough inmate, by claiming "No man of any country whose misfortunes shall bring him here shall be abused in my presence" and had strongly but politely voiced threats against the offender. He had addressed an outburst of profanity in a similar fashion.

Flora filed for divorce on 17 December 1874 on the grounds of extreme cruelty, but this first petition was dismissed. It was reported that she fully sympathized with the prosecution of her husband.

Muybridge was tried for murder in February 1875. His attorney, W. W. Pendegast (a friend of Stanford), pleaded insanity in his behalf due to a severe head injury suffered in the 1860 stagecoach accident. At least four long-time acquaintances testified under oath that the accident had dramatically changed Muybridge's personality, from genial and pleasant to unstable and erratic. During the trial, Muybridge undercut his own insanity case by indicating that his actions were deliberate and premeditated, but he also showed impassive indifference and uncontrolled explosions of emotion. In the end he was acquitted on the grounds of justifiable homicide

The concept of justifiable homicide in criminal law is a defense to culpable homicide (criminal or negligent homicide). Generally, there is a burden of production of exculpatory evidence in the legal defense of justification. In most countri ...

, with the jury explanation that if their verdict was not in accordance with the law, it was in accordance with the law of human nature. In other words: they believed they could not punish a person for doing something that they themselves would do in similar circumstances.

The episode interrupted his photography studies, but not his relationship with Stanford, who had arranged for his criminal defence. By 1877, Muybridge had resumed his photographic work for Stanford.

Shortly after his acquittal in February 1875, Muybridge left the United States on a previously planned 9-month photography trip to Central America, now acting as a "working exile". His photographs from this period are less known, because relatively few copies were produced. It is believed that during this period, he further developed his ability to take pictures more rapidly, due to the requirement that these processes be performed aboard a constantly-rolling ship.

Flora's second petition for divorce received a favourable ruling, and an order for alimony

Alimony, also called aliment (Scotland), maintenance (England, Ireland, Northern Ireland, Wales, Canada, New Zealand), spousal support (U.S., Canada) and spouse maintenance (Australia), is a legal obligation on a person to provide financial suppo ...

was entered in April 1875. Flora died suddenly in July 1875 while Muybridge was in Central America. She had placed their son, Florado Helios Muybridge (later nicknamed "Floddie" by friends), with a French couple. In 1876, Muybridge had the boy moved from a Catholic orphanage to a Protestant one and paid for his care. Otherwise he had little to do with him.

Photographs of Florado Muybridge as an adult show him to have strongly resembled Muybridge. Put to work on a ranch as a boy, he worked all his life as a ranch hand

A cowboy is an animal herder who tends cattle on ranches in North America, traditionally on horseback, and often performs a multitude of other ranch-related tasks. The historic American cowboy of the late 19th century arose from the ''vaquero'' ...

and gardener. In 1944, Florado was hit by a car in Sacramento

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

and killed.

Today, the court case and transcripts are important to historians and forensic

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science to criminal and civil laws, mainly—on the criminal side—during criminal investigation, as governed by the legal standards of admissible evidence and criminal p ...

neurologists

Neurology (from el, νεῦρον (neûron), "string, nerve" and the suffix -logia, "study of") is the branch of medicine dealing with the diagnosis and treatment of all categories of conditions and disease involving the brain, the spinal ...

, because of the sworn testimony from multiple witnesses regarding Muybridge's state of mind and past behaviour.

In 1982, American composer Philip Glass

Philip Glass (born January 31, 1937) is an American composer and pianist. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential composers of the late 20th century. Glass's work has been associated with minimal music, minimalism, being built up fr ...

would create an opera, ''The Photographer

''The Photographer'' is a three-part mixed media performance accompanied by music (also sometimes referred to as a chamber opera) by composer Philip Glass. The libretto is based on the life and homicide trial of 19th-century English photographer ...

'', with a libretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the t ...

based in part on court transcripts from the case.

1882–1893: Motion studies in Philadelphia

Muybridge often travelled to American cities as well as back to England and Europe to publicise his work. The opening of theTranscontinental Railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous railroad trackage, that crosses a continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks can be via the tracks of either a single ...

in 1869 and the development of steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

s made travel much faster and less arduous than it was in 1860. On 13 March 1882 he lectured at the Royal Institution in London in front of a sell-out audience, which included members of the Royal Family

A royal family is the immediate family of kings/queens, emirs/emiras, sultans/ sultanas, or raja/ rani and sometimes their extended family. The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term ...

, notably the future King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria a ...

.Brian Cleg''The Man Who Stopped Time: The Illuminating Story of Eadweard Muybridge : Pioneer Photographer, Father of the Motion Picture, Murderer''

Joseph Henry Press, 2007 He displayed his photographs on screen and showed moving pictures projected by his zoopraxiscope. He also lectured at the

Royal Academy of Arts

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its purpo ...

and the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

.

Muybridge and Stanford had a major falling-out concerning his research on equine locomotion. Stanford had asked his friend and horseman Dr JBD Stillman to write a book analysing ''The Horse in Motion'', which was published in 1882."Capturing the Moment", p. 2''Freeze Frame: Eadward Muybridge's Photography of Motion'', 7 October 2000 – 15 March 2001, National Museum of American History, accessed 9 April 2012 Stillman used Muybridge's photos as the basis for his 100 illustrations, and the photographer's research for the analysis, but he gave Muybridge no prominent credit. The historian Phillip Prodger later suggested that Stanford considered Muybridge as just one of his employees, and not deserving of special recognition. Stanford was quite proud of his role in creating the book, and commissioned a portrait of himself by

Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier

Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier (; 21 February 181531 January 1891) was a French Classicist painter and sculptor famous for his depictions of Napoleon, his armies and military themes. He documented sieges and manoeuvres and was the teacher of É ...

, in which a copy of the volume was visible under his arm.

However, as a result of Muybridge not being credited in the book, the Royal Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA), also known as the Royal Society of Arts, is a London-based organisation committed to finding practical solutions to social challenges. The RSA acronym is used m ...

withdrew an offer to fund his stop-motion studies in photography, and refused to publish a paper he had submitted, accusing him of plagiarism

Plagiarism is the fraudulent representation of another person's language, thoughts, ideas, or expressions as one's own original work.From the 1995 '' Random House Compact Unabridged Dictionary'': use or close imitation of the language and thought ...

. Muybridge filed a lawsuit against Stanford to gain credit, but it was delayed two years and then dismissed out of court. Stillman's book did not sell as expected. Muybridge, looking elsewhere for funding, was more successful. The Royal Society of Arts eventually invited Muybridge back to show his work.

In 1883, Muybridge gave a lecture at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

Pennsylvania (; (Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, Maryl ...

(PAFA), arranged by artist Thomas Eakins

Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins (; July 25, 1844 – June 25, 1916) was an American realist painter, photographer, sculptor, and fine arts educator. He is widely acknowledged to be one of the most important American artists.

For the length ...

and University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

(Penn) trustee Fairman Rogers. At that time, Eakins was a faculty member at PAFA, and had recently been appointed its director. A group of Philadelphians, including Penn Provost William Pepper

William Pepper Jr. (August 21, 1843July 28, 1898), was an American physician, leader in medical education in the nineteenth century, and a longtime Provost of the University of Pennsylvania. In 1891, he founded the Free Library of Philadelphia ...

and the publisher J.B. Lippincott recruited him to work at Penn under their sponsorship. Between 1883 and 1886, Muybridge made more than 100,000 images, working obsessively in a dedicated studio at the northeast corner of 36th and Pine streets in Philadelphia. He was now able to afford multiple larger high-quality lenses, giving him the ability to make simultaneous pictures from multiple viewpoints, with a clarity and tonal range not achieved earlier.

In 1884, Eakins briefly worked alongside Muybridge, to learn more about the application of photography to the study of human and animal motion. Eakins later favoured the use of multiple exposure

In photography and cinematography, a multiple exposure is the superimposition of two or more exposures to create a single image, and double exposure has a corresponding meaning in respect of two images. The exposure values may or may not be ide ...

s superimposed on a single photographic negative to study motion more precisely, while Muybridge continued to use multiple cameras to produce separate images which could also be projected by his zoopraxiscope.

The vast majority of Muybridge's work at this time was done at a special sunlit outdoor studio, due to the still-bulky cameras and relatively slow photographic emulsion

Photographic emulsion is a light-sensitive colloid used in film-based photography. Most commonly, in silver-gelatin photography, it consists of silver halide crystals dispersed in gelatin. The emulsion is usually coated onto a substrate of g ...

speeds then available. Most of the photographs were taken during the summers, and winters were spent developing and organizing the images. He used banks of 12 custom-made cameras to photograph professors, athletes, students, disabled patients from the Blockley Almshouse

The Blockley Almshouse, later known as Philadelphia General Hospital, was a charity hospital and poorhouse located in West Philadelphia. It originally opened in 1732/33 in a different part of the city as the Philadelphia Almshouse (not to be conf ...

(located next to Penn at the time), and local residents, all in motion. He photographed at least 9 sequences showing the movements of neurological patients. He also borrowed animals from the Philadelphia Zoo

The Philadelphia Zoo, located in the Centennial District of Philadelphia on the west bank of the Schuylkill River, is the first true zoo in the United States. It was chartered by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania on March 21, 1859, but its openin ...

, to study their movements in detail.

The human models, usually either entirely nude or very lightly clothed, were photographed against a measured grid background in a variety of action sequences, including walking up or down stairs, hammering on an anvil, carrying buckets of water, or throwing water over one another. Muybridge produced sequences showing farm, industrial, construction, and household work, military manoeuvres, and everyday activities. He also photographed athletic activities such as baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding tea ...

, cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by striki ...

, boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

, wrestling

Wrestling is a series of combat sports involving grappling-type techniques such as clinch fighting, throws and takedowns, joint locks, pins and other grappling holds. Wrestling techniques have been incorporated into martial arts, combat ...

, discus throwing

The discus throw (), also known as disc throw, is a track and field event in which an athlete throws a heavy disk (mathematics), disc—called a discus—in an attempt to mark a farther distance than their competitors. It is an classical antiqui ...

, and a ballet

Ballet () is a type of performance dance that originated during the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It has since become a widespread and highly technical form of ...

dancer performing. Showing a single-minded dedication to scientific accuracy and artistic composition, Muybridge himself posed nude for some of the photographic sequences, such as one showing him swinging a miner's pick. Toward the end of this period, Muybridge spent much of his time selecting and editing his photos in preparation for publication.

In 1887, the photos were published as a massive

In 1887, the photos were published as a massive collotype

Collotype is a gelatin-based photographic printing process invented by Alphonse Poitevin in 1855 to print images in a wide variety of tones without the need for halftone screens. The majority of collotypes were produced between the 1870s and 1 ...

portfolio in 11 volumes, with 781 plates comprising 20,000 of the photographs, in a groundbreaking collection titled '' Animal Locomotion: an Electro-photographic Investigation of Consecutive Phases of Animal Movements''.Selected Items from the Eadweard Muybridge Collection (University of Pennsylvania Archives and Records Center)"The Eadweard Muybridge Collection at the University of Pennsylvania Archives contains 702 of the 784 plates in his Animal Locomotion study" Muybridge's work contributed substantially to developments in the science of

biomechanics

Biomechanics is the study of the structure, function and motion of the mechanical aspects of biological systems, at any level from whole organisms to organs, cells and cell organelles, using the methods of mechanics. Biomechanics is a branch of ...

and the mechanics of athletics. Some of his books are still published today, and are used as references by artists, animators, and students of animal and human movement.

Abdul Hamid II

Abdülhamid or Abdul Hamid II ( ota, عبد الحميد ثانی, Abd ül-Hamid-i Sani; tr, II. Abdülhamid; 21 September 1842 10 February 1918) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 31 August 1876 to 27 April 1909, and the last sultan to ...

, who had a keen interest in photography. This gift may have helped to secure permissions for the excavations that scholars from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology—commonly known as the Penn Museum—is an archaeology and anthropology museum at the University of Pennsylvania. It is located on Penn's campus in the University City neighb ...

later pursued in the Ottoman region of Mesopotamia (now Iraq), notably at the site of Nippur

Nippur (Sumerian language, Sumerian: ''Nibru'', often logogram, logographically recorded as , EN.LÍLKI, "Enlil City;"The Cambridge Ancient History: Prolegomena & Prehistory': Vol. 1, Part 1. Accessed 15 Dec 2010. Akkadian language, Akkadian: '' ...

. The Ottoman sultan reciprocated, five years later, by sending as a gift to the United States a collection of photograph albums featuring Ottoman scenes: the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

now preserves these albums as the Abdul Hamid II Collection.

Recent scholarship has noted that in his later work, Muybridge was influenced by, and in turn, influenced the French photographer Étienne-Jules Marey

Étienne-Jules Marey (; 5 March 1830, Beaune, Côte-d'Or – 15 May 1904, Paris) was a French scientist, physiologist and chronophotographer.

His work was significant in the development of cardiology, physical instrumentation, aviation, cinema ...

. In 1881, Muybridge first visited Marey's studio in France and viewed stop-motion studies before returning to the US to further his own work in the same area. Marey was a pioneer in producing multiple-exposure, sequential images using a rotary shutter in his so-called "Marey wheel" camera.

While Marey's scientific achievements in the realms of cardiology

Cardiology () is a branch of medicine that deals with disorders of the heart and the cardiovascular system. The field includes medical diagnosis and treatment of congenital heart defects, coronary artery disease, heart failure, valvular heart d ...

and aerodynamics

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dyn ...

(as well as pioneering work in photography and chronophotography

Chronophotography is a photographic technique from the Victorian era which captures a number of phases of movements. The best known chronophotography works were mostly intended for the scientific study of locomotion, to discover practical informa ...

) are indisputable, Muybridge's efforts were to some degree more artistic rather than scientific. As Muybridge explained, in some of his published sequences he had substituted images where original exposures had failed, in order to illustrate a representative movement (rather than producing a strictly scientific recording of a particular sequence).

Today, similar setups of carefully timed multiple cameras are used in modern special effects photography, but they have the opposite goal of capturing changing camera angles, with little or no movement of the subject. This is often dubbed " bullet time" photography.

After his work at the University of Pennsylvania, Muybridge travelled widely and gave numerous lectures and demonstrations of his still photography and primitive motion picture sequences. At the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordi ...

of 1893, Muybridge presented a series of lectures on the "Science of Animal Locomotion" in the Zoopraxographical Hall, built specially for that purpose in the "Midway Plaisance" arm of the exposition. He used his zoopraxiscope to show his moving pictures to a paying public. The Hall was the first commercial movie theatre. He also sold a series of souvenir phenakistoscope

The phenakistiscope (also known by the spellings phénakisticope or phenakistoscope) was the first widespread animation device that created a fluent illusion of motion. Dubbed and ('stroboscopic discs') by its inventors, it has been known unde ...

discs to demonstrate simple animations, using painted colour images derived from his photographs.

Waltz

The waltz ( ), meaning "to roll or revolve") is a ballroom and folk dance, normally in triple ( time), performed primarily in closed position.

History

There are many references to a sliding or gliding dance that would evolve into the wa ...

ing''

File:Phenakistoscope 3g07690a.gif, Spinning disc

File:Phenakistoscope 3g07690d.gif, Animation detail

File:Man and woman dancing a waltz (1887).gif, Animation of original Muybridge sequence (1887)

1894–1904: Retirement and death

Eadweard Muybridge returned to his native England in 1894 and continued to lecture extensively throughout Great Britain. He returned to the US once more, in 1896–1897, to settle financial affairs and to dispose of property related to his work at the University of Pennsylvania. He retained control of his negatives, which he used to publish two popular books of his work, ''Animals in Motion'' (1899) and ''The Human Figure in Motion'' (1901), both of which remain in print over a century later. Muybridge died on 8 May 1904 in Kingston upon Thames ofprostate cancer

Prostate cancer is cancer of the prostate. Prostate cancer is the second most common cancerous tumor worldwide and is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality among men. The prostate is a gland in the male reproductive system that sur ...

at the home of his cousin Catherine Smith. It is claimed that at that time, he was excavating a scale model of the American Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

in the back garden. His body was cremated, and its ashes interred in a grave at Woking

Woking ( ) is a town and borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in northwest Surrey, England, around from central London. It appears in Domesday Book as ''Wochinges'' and its name probably derives from that of a Anglo-Saxon settlement o ...

in Surrey. On the grave's headstone his name is misspelled as "Eadweard Maybridge".

In 2004, a British Film Institute

The British Film Institute (BFI) is a film and television charitable organisation which promotes and preserves film-making and television in the United Kingdom. The BFI uses funds provided by the National Lottery to encourage film production, ...

commemorative plaque was installed on the outside wall of the former Smith house, at Park View, 2 Liverpool Road. Many of his papers and collected artefacts were donated to Kingston Library, and are currently under the ownership of Kingston Museum in his place of birth.

Influence on others

According to an exhibition atTate Britain

Tate Britain, known from 1897 to 1932 as the National Gallery of British Art and from 1932 to 2000 as the Tate Gallery, is an art museum on Millbank in the City of Westminster in London, England. It is part of the Tate network of galleries in ...

, "His influence has forever changed our understanding and interpretation of the world, and can be found in many diverse fields, from Marcel Duchamp's painting ''Nude Descending a Staircase'' and countless works by Francis Bacon, to the blockbuster film ''The Matrix'' and Philip Glass's opera ''The Photographer''."

In 2010, the American painter Philip Pearlstein

Philip Martin Pearlstein (May 24, 1924 – December 17, 2022) was an American painter best known for Modernist Realist nudes. Cited by critics as the preeminent figure painter of the 1960s to 2000s, he led a revival in realist art.

Biography ...

published an article in ''ARTnews'' suggesting the strong influences Muybridge's work and public lectures had on 20th-century artists, including Degas

Edgar Degas (, ; born Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas, ; 19 July 183427 September 1917) was a French Impressionist artist famous for his pastel drawings and oil paintings.

Degas also produced bronze sculptures, prints and drawings. Degas is espec ...

, Rodin

François Auguste René Rodin (12 November 184017 November 1917) was a French sculptor, generally considered the founder of modern sculpture. He was schooled traditionally and took a craftsman-like approach to his work. Rodin possessed a uniqu ...

, Seurat

Georges Pierre Seurat ( , , ; 2 December 1859 – 29 March 1891) was a French post-Impressionist artist. He devised the painting techniques known as chromoluminarism and pointillism and used conté crayon for drawings on paper with a rough su ...

, Duchamp, and Eakins, either directly or through the contemporaneous work of his fellow photographic pioneer, Marey. He concluded: "I believe that both Muybridge and Eakins—as a photographer—should be recognized as among the most influential artists on the ideas of 20th-century art, along with Cézanne, whose lessons in fractured vision provided the technical basis for putting those ideas together."

* Étienne-Jules Marey

Étienne-Jules Marey (; 5 March 1830, Beaune, Côte-d'Or – 15 May 1904, Paris) was a French scientist, physiologist and chronophotographer.

His work was significant in the development of cardiology, physical instrumentation, aviation, cinema ...

– in 1882 recorded the first series of live-action photos with a single camera by a method of chronophotography